Abstract

Purpose

To investigate orthopaedic patient compliance with patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and identify factors that improve response rates.

Methods

Our search strategy comprised a combination of key words and database-specific subject headings for the concepts of orthopaedic surgical procedures, compliance, and PROMs from several research databases from inception to October 11, 2022. Duplicates were removed. A total of 97 studies were included. A table was created for the remaining articles to be appraised and analyzed. The collected data included study characteristics, follow-up/compliance rate, factors that increase/decrease compliance, and type of PROM. Follow-up/compliance rate was determined to be any reported response rate. The range and average used for analysis was based on the highest or lowest number reported in the specific article.

Results

The range of compliance reported was 11.3% to 100%. The overall response rate was 68.6%. The average baseline (preoperative/previsit) response rate was 76.6%. Most studies (77%) had greater than 50% compliance. Intervention/reminder of any type (most commonly phone call or mail) resulted in improved compliance from 44.6% to 70.6%. Young and elderly non-White male patients had the lowest compliance rate. When directly compared, phone call (71.5%) resulted in a greater compliance rate than electronic-based (53.2%) or paper-based (57.6%) surveys.

Conclusions

The response rates for PROMs vary across the orthopaedic literature. Patient-specific factors, such as age (young or old) and race (non-White), may contribute to poor PROM response rate. Reminders and interventions significantly improve PROM response rates.

Clinical Relevance

PROMs are important tools in many aspects of medicine. The data generated from these tools not only provide information about individual patient outcomes but also make hypothesis-driven comparisons possible. Understanding the factors that affect patient compliance with PROMs is vital to our accurate understanding of patient outcomes and the overall advancement of medical care.

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) provide an invaluable resource to the field of medicine. The assessment of outcome from a patient perspective accompanied by that of the clinician creates a more realistic evaluation of quality of care. PROMs standardize subjective responses into an objective measurement, enabling hypothesis-driven comparison. Without PROMs, subjective data are highly heterogeneous, making comparison difficult.1

Several studies suggest incorporation of PROMs can improve patient–physician communication and patient outcomes.1,2 As U.S. health care costs increase, many services are under increased cost-cutting scrutiny. This has led to a rapid shift in reimbursement model from traditional volume-driven fee-for-service to value-based payment models.3 At the core of this shift is value analysis through PROMs.4,5 PROMs provide another measure to determine cost-effectiveness in health care. For this reason, clinical use of PROMs continues to increase at a rapid pace.6

As an objective measurement tool, it is essential for PROMs to have adequate responsiveness, validity, and reliability. On a population level, these qualities have the potential to be significantly affected by patient compliance, as inadequate response rate introduces selection bias and reduces external validity.1,3,6, 7, 8 Real-world compliance is multifactorial. Theoretically, variables including specific PROM used, method of admission, clinic staffing, and more may have significant effects on individual study compliance.1,9 Optimization of these variables is a common struggle experienced when incorporating PROMs into practice with no consensus on most important factors to consider.5 Due to this inconsistency, general compliance with PROMs in the field of orthopaedics is unknown. There is a paucity of information in the literature evaluating overall compliance regarding PROMs in the field of orthopaedics. Knowing PROM compliance rates is valuable in understanding potential for sampling bias, important factors of consideration in future clinical implementation, policy change, and study design. The purposes of this systematic review are to investigate orthopaedic patient compliance with PROMs and identify factors that improve response rates. Our hypothesis was that compliance to PROM would be poor but could be improved with the use of certain interventions.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.10

Information Sources and Search Strategy

Our search included MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (all via Ovid), Web of Science Core Collection, and SPORTDiscus via EBSCOhost from each database’s inception until October 11, 2022. The search strategy comprised a combination of key words and database-specific subject headings for the concepts of orthopaedic surgical procedures, compliance, and PROMs. In order to capture the largest possible queue of articles, the only exclusion was non-English studies to avoid issues involving English translation. Some examples of key words include a combination of compliance or variations of the word (compliant, comply, complies, etc), PROM (PRO, PROM), specific PROMs (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, 12-Item Short Form Health Survey, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index, etc.) and orthopaedic surgery (ortho, orthopedic, arthroscopy, arthroplasty).

Selection and Data-Collection Process

After completion of the query, duplicates were removed using EndNote X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA). The identified articles were uploaded to Rayyan (Doha, Qatar) for screening. Initial screening of titles and abstracts for relevance was conducted by 2 independent reviewers (B.S.K., N.E.A.). Each reviewer was blinded to the results of the other to prevent any selection bias. Any discrepancies during the screening or extraction process were resolved by consensus agreement between the reviewers (B.S.K., N.E.A.) and the primary author (B.J.L.). Two separate rounds of review processes were performed. The first review was broader, including any study pertaining to orthopaedic surgery and PROMs. The second review was narrower, including only articles that specifically mentioned PROM compliance. Full texts of the remaining articles were obtained and assessed for eligibility by the same 2 independent reviewers in addition to the primary author.

Data Items

The information gathered from the systematic review was compiled into a table. The information included study characteristics, follow-up/compliance rate, factors that increase/decrease compliance, and type of PROM. Follow-up/compliance rate was determined to be any reported response rate. If different modalities were used in the study, those were included in the table. The range and average used for analysis was based on the highest or lowest number reported in the specific article.

Results

Study Selection

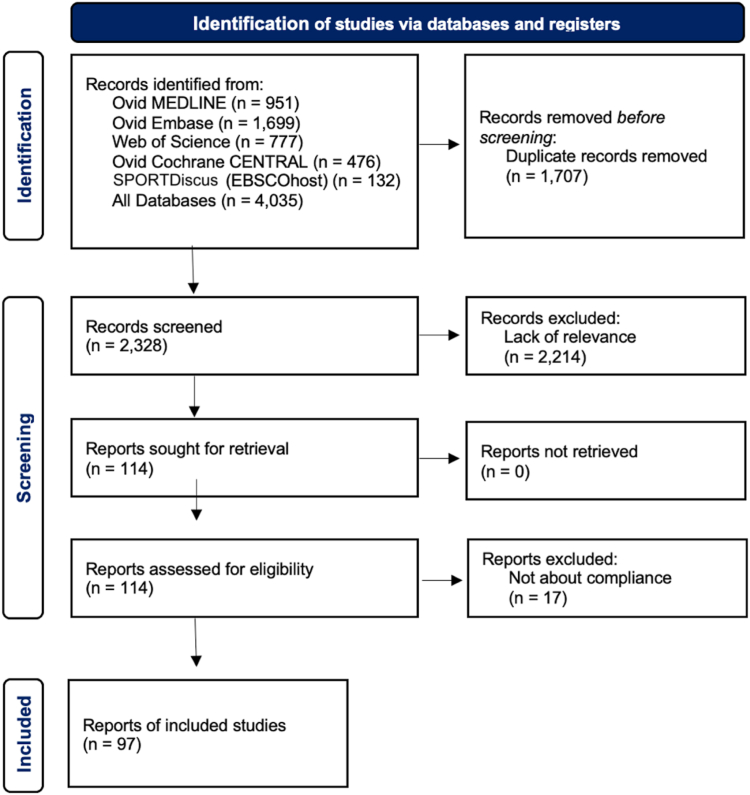

The initial search yielded 4,035 citations. After removal of duplicates, 2,328 citations remained. After the first, broader screening, 1,500 citations remained. On the second, narrower screening, 97 were included (Table 1).11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107 A flow diagram of the screening process is included in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Literature Review of the 97 Included Citations

| Title | First Author | Journal | Year | PubMed ID (if Applicable) | Type of Study | Preoperative | Highest Reported/Postoperative | Patient Factors That Increase Compliance | Patient Factors That Decrease Compliance | Provider Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship of Press Ganey Satisfaction and PROMIS Function and Pain in Foot and Ankle Patients | Nixon40 | Foot Ankle Int | 2020 | 32660263 | Retrospective chart review | 11.3 | ||||

| Response Bias for Press Ganey Ambulatory Surgery Surveys after Knee Surgery | Zhang41 | J Knee Surg | 2022 | 35817060 | Prospective cohort | 12.2 | Male, non-White, student or unemployment status, and worse preoperative score | |||

| Press Ganey Surveys in Patients Undergoing Upper-Extremity Surgical Procedures: Response Rate and Evidence of Nonresponse Bias35 | Weir35 | Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery | 2021 | 33988529 | Retrospective chart review | 13.5 | White, higher education, current employment, and married | |||

| Two Years Following Implementation of the British Spinal Registry (BSR) in a District General Hospital (DGH): Perils, Problems and PROMS | Roysam42 | Spine Journal | 2016 | Prospective cohort | 62 | 20 | ||||

| Evaluation of the Implementation of PROMIS CAT Batteries for Total Joint Arthroplasty in an Electronic Health Record | Rothrock43 | Quality of Life Research | 2018 | Prospective cohor study | 31.8 | |||||

| Factors Associated With Survey Response in Hand Surgery Research16 | Bot16 | Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research | 2013 | 23801062 | Prospective cohort study | 34 | Male, younger age, higher pain, and worse preoperative score | |||

| Two and a Half Years On: Data and Experiences Establishing a 'Virtual Clinic' for Joint Replacement Follow Up | Lovelock44 | ANZ Journal of Surgery | 2018 | 29952097 | Prospective cohort | 35 | ||||

| Association Between Patient Factors and Hospital Completeness of a Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Program in Joint Arthroplasty, A Cohort Study | Harris45 | Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes | 2022 | 35380301 | Multicenter cohort study | 36.3 | ||||

| Comparison of Paper and Electronic Surveys for Measuring Patient-Reported Outcomes After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction | Bojcic46 | Permanente Journal | 2014 | 25102515 | Cross-sectional study | 36.3 | ||||

| Level of Response to Telematic Questionnaires on Health Related Quality of Life on Total Knee Replacement | Besalduch-Balaguer, M47 | Revista Espanola de Cirugia Ortopedica y Traumatologia | 2015 | 25435294 | Observational | 37 | ||||

| Differences in Baseline Characteristics and Outcome Among Responders, Late Responders, and Never-Responders After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction19 | Randsborg, PH19 | The American Journal of Sports Medicine | 2021 | 34723674 | Case–control study | 40 | Younger age, male, low education (high school or less), and non-White | |||

| Sociodemographic Factors Are Associated With Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Completion in Orthopaedic Surgery: An Analysis of Completion Rates and Determinants Among New Patients32 | Bernstein DN32 | JB & JS Open Access | 2022 | 35935603 | Retrospective observational study | 40 | Older age (>65 y), non-White, and non-English speaking | |||

| Collection and Reporting of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in Arthroplasty Registries: Multinational Survey and Recommendations | Bohm, ER48 | Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research | 2021 | 34288899 | Cross-sectional descriptive study | 40 | ||||

| Male Sex, Decreased Activity Level, and Higher BMI Associated With Lower Completion of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Following ACL Reconstruction38 | Cotter38 | Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine | 2018 | 29536023 | Prospective survey | 7.4 | 40.6 | Lower BMI | ||

| E-mail Reminders Improve Completion Rates of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures | Triplet JJ49 | Journal of Shoulder & Elbow Surgery | 2017 | 30675535 | Retrospective cohort study | 40.9 | Email reminders improved response rate | |||

| Pre-visit Digital Messaging Improves Patient Reported Outcome Measure Participation Prior to the Orthopedic Ambulatory Visit13 | Yedulla13 | J Bone Joint Surg Am | 2022 | 36598473 | Prospective RCT | 44 | Previsit e-mail or patient portal messages resulted in greater completion rate | |||

| Small Social Incentives Did Not Improve the Survey Response Rate of Patients Who Underwent Orthopaedic Surgery: A Randomized Trial11 | Warwick11 | Clin Orthop Relat Res | 2019 | 31135552 | Prospective randomized controlled trial | 46 | Female, older age, and White | |||

| Do Medicare’s Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Collection Windows Accurately Reflect Academic Clinical Practice? | Molloy IB50 | The Journal of Arthroplasty | 2020 | 31889578 | Retrospective cohort analysis | 46.2 | ||||

| What Factors Are Associated With Patient-reported Outcome Measure Questionnaire Completion for an Electronic Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry? | Ling DI51 | Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research | 2021 | 32740479 | Retrospective cohort | 72 | 47 | Phone call or e-mail reminder from a research assistant | ||

| Factors Associated With Early Postoperative Survey Completion in Orthopaedic Surgery Patients34 | Sajak PM34 | Journal of Clinical Orthopedics and Trauma | 2020 | 31992938 | Retrospective cohort study | 48 | Never smokers, higher education (college), White, married, employment, higher income, private insurance | |||

| Remote Collection of Patient-Reported Outcomes Following Outpatient Hand Surgery: A Randomized Trial of Telephone, Mail, and E-Mail15 | Schwartzenberger15 | J Hand Surg Am | 2017 | 28600107 | Prospective randomized trial | 48 | Older age and private insurance | |||

| What Factors Are Associated With Response Rates for Long-term Follow-up Questionnaire Studies in Hand Surgery | Westenberg RF52 | Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research | 2020 | 32452929 | Prospective cohort | 49 | Phone call to nonresponders | |||

| The Effects of a Pandemic on Patient Engagement in a Patient-Reported Outcome Platform at Orthopaedic Sports Medicine Centers | Barnds B53 | Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine | 2021 | PMC8562621 | Retrospective cohort study | 50.95 | ||||

| A Non-Response Analysis of 2-YEAR DATA in the Swedish Knee Ligament Register20 | Reinholdsson, J20 | Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy | 2016 | 26724828 | Retrospective cohort analysis | 52 | Older age and female | |||

| Utilization of an Automated SMS-Based Electronic Patient-Reported Outcome Tool in Spinal Surgery Patients | Elsabeh R54 | The Spine Journal (34th NASS meeting) | 2021 | Retrospective cohort | 52 | |||||

| Barriers to Completion of Patient Reported Outcome Measures28 | Schamber EM28 | The Journal of Arthroplasty | 2013 | 23890831 | Prospective cohort study | 54.5 | Older age (>75 y), non-White, revision surgery, non-private insurance (Medicare and Medicaid) | |||

| Implementation of an Automated Text Message-Based System for Tracking Patient-Reported Outcomes in Spine Surgery: An Overview of the Concept and Our Early Experience | Perdomo-Pantoja, A55 | World Neurosurgery | 2022 | 34800733 | Prospective cohort | 71.2 | 54.9 | |||

| Management of Distal Radius Fractures in the Emergency Department: A Long-Term Functional Outcome Measure Study With the Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) Scores | Barai, A56 | EMA - Emergency Medicine Australasia | 2018 | 29488343 | Prospective cohort | 56 | ||||

| Patient Demographic and Surgical Factors That Affect Completion of Patient-Reported Outcomes 90 Days and 1 Year After Spine Surgery: Analysis From the Michigan Spine Surgery Improvement Collaborative (MSSIC)21 | Zakaria H21 | World Neurosurgery | 2019 | 31207366 | Prospective cohort | 72.6 | 56.3 | Older age, higher education, and female | ||

| Patient Compliance With Electronic Patient Reported Outcomes Following Shoulder Arthroscopy | Makhni E57 | Arthroscopy | 2017 | 28958797 | Prospective cohort | 76 | 57 | Research assistant | ||

| Continued Good Results With Modular Trabecular Metal Augments for Acetabular Defects in Hip Arthroplasty at 7 to 11 Years | Whitehouse MR58 | Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research | 2015 | 25123241 | Retrospective cohort study | 58 | ||||

| The Danish Hip Arthroscopy Registry: Registration Completeness and Patient Characteristics Between Responders and Non-Responders22 | Poulsen E22 | Clinical Epidemiology | 2020 | 32801920 | Retrospective cohort study | 58 | Younger age (<25 y) and male | |||

| Overview of the AOA National Joint Replacement Registry: ACL Registry Pilot Study | Clarnette R59 | Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine | 2015 | PMC4901772 | Pilot prospective cohort | 58.5 | ||||

| Evaluating the Measures in Patient-Reported Outcomes, Values and Experiences (EMPROVE study): A Collaborative Audit of PROMs Practice in Orthopaedic Care in the United Kingdom | Matthew A60 | The Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England | 2022 | 35938506 | Multicenter retrospective cohort study | 60 | ||||

| Collection of Common Knee Patient-reported Outcome Instruments by Automated Mobile Phone Text Messaging in Pediatric Sports Medicine18 | Mellor X18 | Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics | 2020 | 31107346 | Prospective cohort study | 60.4 | Female, older age, younger age (<18 y) | |||

| An Exploratory Study of Response Shift In Health-Related Quality of Life and Utility Assessment Among Patients With Osteoarthritis Undergoing Total Knee Replacement Surgery in a Tertiary Hospital in Singapore24 | Zhang XH24 | Value in Health | 2012 | 22265071 | Prospective cohort study | 63 | ||||

| A Last-Ditch Effort and Personalized Surgeon Letter Improves PROMs Follow-Up Rate in Sports Medicine Patients: A Crossover Randomized Controlled Trial12 | Tariq MB | The Journal of Knee Surgery | 2019 | 31390674 | Crossover RCT | 65 | Personalized surgeon letter | |||

| Automated Reporting of Patient Outcomes in Hand Surgery: A Pilot Study | Franko OI | Hand | 2022 | 34521230 | Prospective cohort study | 65 | ||||

| The Patient Perspective on Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Following Elective Hand Surgery: A Convergent Mixed-Methods Analysis | Shapiro LM | Journal of Hand Surgery | 2021 | 33183858 | Prospective cohort study | 66 | ||||

| The Remote Completion Rate of Electronic Patient-Reported Outcome Forms Before Scheduled Clinic Visits-A Proof-of-Concept Study Using Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System Computer Adaptive Test Questionnaires23 | Borowsky PA | Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Global Research and Reviews | 2019 | 31773074 | Prospective cohort study | 67 | Female, White, higher income | |||

| Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation or Surgery for Chronic Low Back Pain—7 Year Follow Up of a Randomised Controlled Trial | Barker K | Spine | 2010 | Prospective cohort | 67 | |||||

| Evaluating Non-responders of a Survey in the Swedish Fracture Register: No Indication of Different Functional Result17 | Juto H | BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders | 2017 | 28659134 | Prospective cohort study | 68 | Women, older age (>60 y) | Phone call | ||

| Integration of Patient-reported Outcomes in a Total Joint Arthroplasty Program at a High-volume Academic Medical Center | Bhatt | JAAOS: Global Research and Reviews | 2020 | 33970573 | Prospective cohort | 68 | ||||

| Feasibility of Web-Based Patient-Reported Outcome Assessment After Arthroscopic Knee Surgery: The Patients' Perspective | Olach M | Swiss Medical Weekly | 2021 | Prospective cohort | 69.6 | |||||

| Interpretations of the Clinical Outcomes of the Nonresponders to Mail Surveys in Patients After Total Knee Arthroplasty | Kwan | Journal of Arthroplasty | 2010 | 19106032 | Prospective cohort | 69.8 | Worse preoperative score | |||

| The RaCeR Study: Rehabilitation Following Rotator Cuff Repair14 | Littlewood C | Clinical Rehabilitation | 2021 | 33305619 | Multicenter RCT | 71 | ||||

| Patient-Reported Outcomes After Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: Comparison of Midterm Results | Wylde V | Journal of Arthroplasty | 2009 | 18534427 | Cross sectional survey | 72 | ||||

| Implementing an Electronic Patient-Based Orthopaedic Outcomes System: Factors Affecting Patient Participation Compliance | Tokish | Military Medicine | 2017 | 28051984 | Prospective cohort | 73 | Staff intervention | |||

| Preoperative Factors Associated with 2-Year Postoperative Survey Completion in Knee Surgery Patients36 | Kadiyala | J Knee Surg | 2022 | 33545724 | Prospective cohort | 73 | 73 | Smoker and Non-White | ||

| Standard of Care PRO Collection Across a Healthcare System | Rubery P | 25th Annual Conference of the International Society for Quality of Life Research | 2018 | Retrospective study | 74 | |||||

| Age Significantly Affects Response Rate to Outcomes Questionnaires Using Mobile Messaging Software26 | Jildeh TR | Arthroscopy, Sports Medicine, and Rehabilitation | 2021 | 34712973 | Prospective cohort study | 75 | Older age | |||

| Partial Versus Total Trapeziectomy Thumb Arthroplasty: An Expertise-Based Feasibility Study | Thoma A | Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery - Global Open | 2018 | 29707461 | Prospective cohort | 75 | ||||

| Follow-up Compliance and Outcomes of Knee Ligamentous Reconstruction or Repair Patients Enrolled in an Electronic Versus a Traditional Follow-up Protocol | Shu H | Orthopedics | 2018 | 30168836 | Retrospective chart review | 76 | ||||

| Active Living With Osteoarthritis Implementation of Evidence-Based Guidelines as First-Line Treatment for Patients With Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis | Risberg M | Osteoarthritis and Cartilage | 2018 | Prospective cohort study | 77 | |||||

| A Pilot Study Investigating the use of At-Home, Web-Based Questionnaires Compiling Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Following Total Hip and Knee Replacement Surgeries | Gakhar H | Journal of Long-term Effects of Medical implants | 2013 | 24266443 | Prospective cohort study | 78 | ||||

| Polytrauma and High-energy Injury Mechanisms are Associated With Worse Patient-reported Outcomes After Distal Radius Fractures | van der Vliet, Q | Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research | 2019 | 30985610 | Retrospective chart review with follow up survey | 78 | ||||

| Feasibility of Collecting Multiple Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Alongside the Dutch Arthroplasty Register | Tilbury C | Journal of Patient Experience | 2020 | 33062868 | Prospective observational cohort study | 78.5 | ||||

| Patient-Reported Outcome After Displaced Femoral Neck Fracture: A National Survey of 4467 Patients | Leonardsson O | Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery | 2013 | 24048557 | Prospective cohort | 79 | Reminder | |||

| Combined Email and in Office Technology Improves Patient Reported Outcomes Collection in Standard Orthopaedic Care33 | Zhou X | Osteoarthritis and Cartilage | 2014 | Prospective cohort study | 79 | Older Age | ||||

| Feasibility of Four Patient Reported Outcome Measures in the Danish Hip Arthroplasty Registry. A Cross-Sectional Study of 6000 Patients | Paulsen | HIP International | 2010 | 26625504 | Cross-sectional cohort | 80 | Two reminders sent to nonresponders | |||

| Improving the Response Rate of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in an Australian Tertiary Metropolitan Hospital | Ho | Patient Related Outcome Measures | 2019 | 31372076 | Prospective cohort | 81.01 | Paper forms, multi-lingual, staff assistance | |||

| Implementing an ICHOM Standard Set to Capture Osteoarthritis Outcomes in Real-World Clinical Settings | Cavka | Osteoarthritis and Cartilage | 2018 | 30148249 | Mixed-methods design | 61 | 81.6 | |||

| Reliability of Patient-Reported Functional Outcome in a Joint Replacement Registry. A Comparison of Primary Responders and Non-responders in the Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry39 | Polk | Acta Orthop | 2013 | 23343374 | Prospective cohort | 82 | Postal reminders | |||

| Response Rate and Costs for Automated Patient-Reported Outcomes Collection Alone Compared to Combined Automated and Manual collection | Pronk | J Patient Rep Outcomes | 2019 | 31155689 | Observational | 100 | 83 | Postal reminders | ||

| Feasibility of 4 Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in a Registry Setting27 | Paulsen A | Acta Ortopaedica | 2012 | 22900909 | Cross-sectional study | 84 | Older age | |||

| Detailing Postoperative Pain and Opioid Utilization After Periacetabular Osteotomy With Automated Mobile Messaging | Hajewski C | Journal of Hip Preservation Surgery | 2019 | 33354334 | Single-center prospective cohort study | 84.1 | Mobile messaging | |||

| Loss to Patient-Reported Outcome Measure Follow-Up After Hip Arthroplasty and Knee Arthroplasty: Patient Satisfaction, Associations With Non-Response, and Maximizing Returns | Ross | Bone & Joint Open | 2022 | 35357243 | Prospective cohort | 84.2 | ||||

| External Validation of the Tyrolean Hip Arthroplasty Registry31 | Wagner M | Journal of Experimental Orthopaedics | 2022 | 36042064 | Cohort | 84.45 | Younger and male | |||

| Informed, Patient-Centered Decisions Associated With Better Health Outcomes in Orthopedics: Prospective Cohort Study | Sepucha | Medical Decision Making | 2018 | 30403575 | Observational survey | 70.3 | 85 | Phone and mailed reminders | ||

| Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis Remain Stable up to 10 Years After ACL Reconstruction | Spindler K | Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine | 2022 | PMC9339818 | Multicenter retrospective cohort study | 85 | ||||

| The Value of Short and Simple Measures to Assess Outcomes for Patients of Total Hip Replacement Surgery | Fitzpatrick R | Quality in Health Care | 2000 | 10980074 | Retrospective cohort | 85.2 | ||||

| Arthroplasty Studies With Greater Than 1000 Participants: Analysis of Follow-Up Methods | Tariq MB12 | Arthroplasty Today | 2019 | 31286051 | Systematic review & meta-analysis | 86 | ||||

| Patient Adoption and Utilization of a Web-Based and Mobile-Based Portal for Collecting Outcomes After Elective Orthopedic Surgery | Bell, K86 | American Journal of Medical Quality | 2018 | 29562769 | Retrospective chart review | 87.14 | ||||

| Is It Too Early to Move to Full Electronic PROM Data Collection? A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing PROM's After Hallux Valgus Captured by E-Mail, Traditional Mail and Telephone | Palmen87 | Foot and Ankle Surgery | 2016 | 26869500 | Prospective cohort | 88 | ||||

| Integrating PROM Collection for Shoulder Surgical Patients through the Electronic Medical Record: A Low Cost and Effective Strategy for High Fidelity PROM Collection | Fife88 | Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine | 2022 | PMC9339844 | Retrospective chart review | 88 | ||||

| Extending the Use of PROM Scores in the Hip and Knee Replacemnt Patient Pathway in the NHS–Enhancing Response Rates Through Patient Engagement | Harris K89 | Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. Conference: Patient Reported Outcome Measure's, PROMs Conference: Advances in Patient Reported Outcomes Research. | 2017 | 23965934 | Prospective cohort study | 90 | ||||

| Implementation of Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Data Collection in a Private Orthopedic Surgery Practice | Haskell90 | Foot & Ankle International | 2018 | 29366343 | Retrospective chart review | 90 | ||||

| The Oxford Knee Score; Problems and Pitfalls | Whitehouse SL91 | The Knee | 2005 | 15993604 | Retrospective cohort study | 90 | ||||

| Factors Affecting the Quality of Life After Total Knee Arthroplasties: A Prospective Study | Papakostidou, I92 | BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders | 2012 | 22748117 | Prospective cohort study | 90.12 | ||||

| MOON's Strategy for Obtaining Over Eighty Percent Follow-up at 10 Years Following ACL Reconstruction | Marx R93 | Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery | 2022 | 34424872 | Prospective cohort | 90.5 | Email and telephone calls | |||

| Feasibility of PROMIS CAT Administration in the Ambulatory Sports Medicine Clinic With Respect to Cost and Patient Compliance: A Single-Surgeon Experience29 | Lizzio VA29 | Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine | 2019 | 30733973 | Prospective cohort | 91.3 | Older age | |||

| Cervical Disc Arthroplasty for Degenerative Disc Disease: Two-Year Follow-Up from an International Prospective, Multicenter, Observational Study | Baeesa, SS94 | The Spine Journal | 2015 | Observational | 92 | |||||

| Internet-Based Follow-Up Questionnaire for Measuring Patient-Reported Outcome After Total Hip Replacement Surgery-Reliability and Response Rate | Rolfson95 | Value in Health | 2011 | 21402299 | Prospective cohort | 92 | ||||

| PROMIS Physical Function Correlation With NDI and mJOA in the Surgical Cervical Myelopathy Patient Population | Owen96 | Spine (Phila Pa 1976) | 2018 | 28787313 | Prospective cohort | 100 | 92 | |||

| What Is the Minimum Response Rate on Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Needed to Adequately Evaluate Total Hip Arthroplasties | Pronk Y97 | Health and Quality of Life Outcomes | 2020 | 33267842 | Retrospective cohort | 99.8 | 92.2 | Phone call | ||

| Mobile Phone Administration of Hip-Specific Patient-Reported Outcome Instruments Correlates Highly With In-office Administration | Scott E98 | Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons | 2020 | 31860543 | Prospective cohort | 93 | Text message | |||

| Validation of Electronic Administration of Knee Surveys Among ACL-Injured Patients | Nguyen J99 | Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy | 2017 | 27316698 | Prospective cohort | 94 | ||||

| PROMIS Correlation With NDI and VAS Measurements of Physical Function and Pain in Surgical Patients With Cervical Disc Herniations and Radiculopathy | Owen100 | J Neurosurg Spine | 2019 | 31277059 | Prospective cohort | 100 | 94 | |||

| Prospective Randomized Cohort Study to Explore the Acceptability of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures to Patients of Hand Clinics | Sierakowski101 | J Hand Surg Glob Online | 2020 | 35415526 | Prospective randomized cohort | 85 | 94 | |||

| Perioperative Satisfaction and Health Economic Questionnaires in Patients Undergoing an Elective Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study | Nagappa, M102 | Anesthesia: Essays and Researches | 2021 | 35422546 | Prospective cohort | 98.8 | 94.2 | |||

| Networking to Capture Patient-Reported Outcomes During Routine Orthopaedic Care Across Two Distinct Institutions | Karia R103 | Osteoarthritis and Cartilage | 2013 | Prospective cohort | 95 | |||||

| Feasibility of Integrating Standardized Patient-Reported Outcomes in Orthopedic Care | Slover J104 | American Journal of Managed Care | 2015 | 26625504 | Prospective cohort | 95 | ||||

| Patient Satisfaction Compared With General Health and Disease-Specific Questionnaires in Knee Arthroplasty Patients30 | Robertsson O30 | Journal of Arthroplasty | 2001 | 11402411 | Survey | 95.1 | Older age, female, and worse preoperative score | |||

| Monitoring Patient Recovery After THA or TKA Using Mobile Technology | Lyman S105 | HSS Journal | 2020 | 33380968 | Prospective cohort | 96 | ||||

| The Use of a Patient-Based Questionnaire (The Oxford Shoulder Score) to Assess Outcome After Rotator Cuff Repair | Olley LM106 | The Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England | 2008 | 18492399 | Prospective cohort | 97 | Phone call | |||

| A Descriptive Study of the Use of Visual Analogue Scales and Verbal Rating Scales for the Assessment of Postoperative Pain in Orthopedic Patients25 | Briggs M25 | Journal of Pain and Symptom Management | 1999 | 10641470 | Prospective cohort study | 99.5 | Older age and Female | |||

| Short Message Service-Based Collection of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures on Hand Surgery Global Outreach Trips: A Pilot Feasibility Study | Shapiro107 | J Hand Surg Am | 2022 | 34148790 | Prospective cohort | 100 | ||||

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; PROM; patient-reported outcome measure; RCT, randomized controlled trial; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

Fig 1.

Flow diagram of search query.

Study Characteristics

The 97 included citations were published between 1999 and 2022; 93.8% (91/97) were published after 2010. In total, 94.8% (92/97) of citations were nonrandomized observational studies.

Overall Compliance

All 97 studies reported PROM response in either the postoperative/postvisit setting or did not specify. The mean response rate overall was 68.6% (range 11.3%-100%). The median response rate was 73%. In total, 77% (75/97) of studies had greater than 50% compliance.

Baseline (Preoperative or Previsit)

Only 15% (15/97) reported PROM response in the preoperative/previsit setting. The mean response rate across these studies was 76.6% (range 7.4%-100%). The median response rate was 73%. In those 15 studies that included preoperative/previsit baseline PROMs, the mean response rate of PROM in the postoperative/postvisit setting for those particular studies was 71% (range 40.6%-94.2%).

Results by Study Type

In total, 5.2% (5/97) of publications were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Of the 5, 4 studies had PROM as the primary outcome measure for randomization.11, 12, 13, 14 The 4 studies aimed to identify what factors improved response rate either compared with a control or to different modalities. The mean response rate among the RCTs was 54.8% (range 44%-71%, median 48%).

One RCT directly compared response rate based on different collection methods: phone call, e-mail, or mail.15 The overall response rate for the study was 48%. Phone calls yielded the greatest response rate of 64% versus 42% for e-mail and 42% for mail. In total, 94.8% (92/97) of citations were nonrandomized observational studies. The mean response rate among these studies was 69.4% (range 11.3%-100%). The median response rate was 75%.

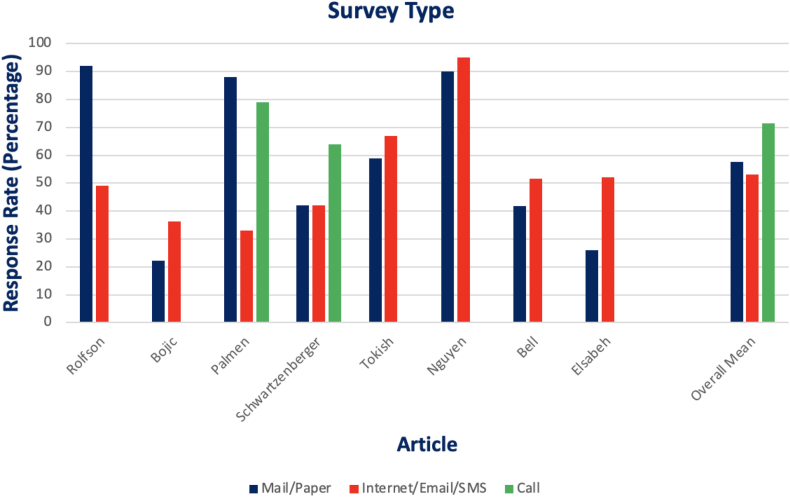

Intervention

Intervention/reminder of any type (most commonly phone call or mail) resulted in improved compliance from 44.6% to 70.6%. Reminder types included phone call, mail, e-mail, text message, or some combination of multiple. When directly compared, phone call (71.5%) resulted in a greater compliance rate than electronic-based (53.2%) or paper-based (57.6%) surveys. The findings are shown in Figure 2.

Fig 2.

Graph of response rate by survey type from the articles that were directly compared.

Patient-Specific Factors

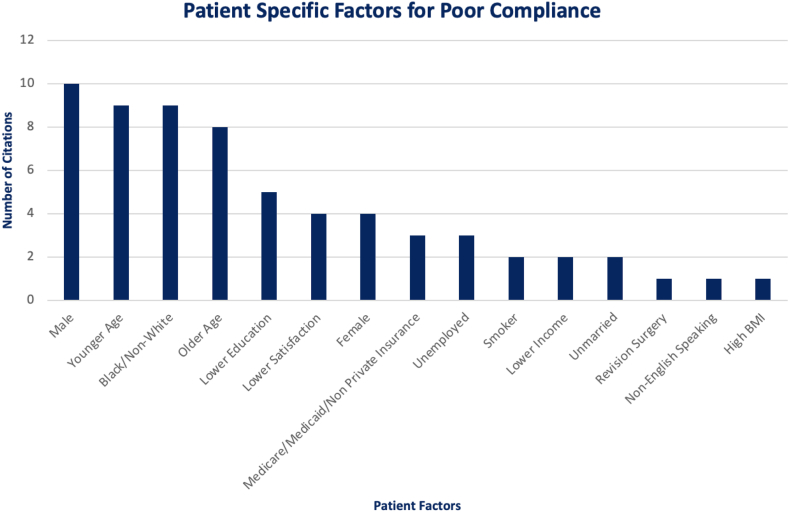

There were many different demographic characteristics compared in individual studies. Age, sex, race, education, insurance type, employment, smoking status, satisfaction rate, marital status, body mass index, and primary language were some of the demographics collected. Although there was heterogeneity in the results, the most commonly contributed factors to poor compliance were male sex,11,16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 extremes of age (young and old),11,15,16,18, 19, 20, 21, 22,25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 and non-White race.11,19,24,28,32,34, 35, 36 Lower education, lower satisfaction, female sex, nonprivate insurance, unemployed, smoker, lower income, prior surgery, unmarried, high body mass index and non-English-speaking were some of the other factors mentioned in individual citations to be associated with poor compliance.15,16,19,21,23, 24, 25,28,30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 These findings are shown in Figure 3.

Fig 3.

Graph of patient-specific factors cited as contributing to poor compliance. (BMI, body mass index.)

Discussion

The most important finding of this systematic review is that although a variety of factors can affect compliance with PROMS after orthopaedic surgery, reminders and other interventions can improve response rates. All 97 studies included in this systematic review reported PROM response rate in the postoperative setting. The average response rate across these studies was 53.6% (range 11.3%-100%). In addition to PROMs in the postoperative setting, it is crucial to obtain PROMs in the preoperative setting. Doing so establishes a baseline score for objective comparison to determine whether a surgical intervention was successful. Ideally, the rate of compliance in the postoperative setting should be similar or improved as compared with compliance in the preoperative setting.

Of the 97 studies that reported PROM compliance in the postoperative period, only 15% reported PROM response in the preoperative setting. The average response rate across these studies was 76.6% (range 7.4%-100%). When further examining the rate of PROM response in the postoperative setting for these 15 studies, the average response rate was 71% (range 40.6%-94.2%). Overall, the average PROM response rate in the postoperative setting for all included studies was 68.6% (range 11.3%-100%).

The compliance rates in PROMs poses several issues when evaluating the validity of an orthopaedic study. One particular concern is the introduction of response bias when patients are lost to follow-up. This could be attributed to a spectrum of reasons. One reason being these patients may experience worse outcomes in pain and function that discourage them from continued follow-up. In fact, 4 of the evaluated studies cited lower patient satisfaction as one of the reasons for decreased rates of PROM compliance. Socioeconomic and demographic factors may also play a role, as a number of the evaluated studies cited male sex, older age, non-White race, lower education, and lower income or unemployed backgrounds as risk factors for poor compliance. The cumulative effect of these factors introduces significant bias in what is supposed to serve as an objective measurement tool in PROMs. Thus, this highlights the added importance of maintaining high rates of compliance in PROMs in order to preserve an appropriate level of study validity and reliability.

A commonly used method to increase PROM compliance is the use of reminders. In a study by Polk et al.39 that observed PROM responsiveness in the Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry, it was reported that the rate of response at the 1-year mark for follow-up was 65% before the use of a reminder. They then used mail-only and call/mail reminders to initial nonresponders, and subsequently observed response rates of 80% and 82% respectively.

PROM compliance also may depend on the mode of communication in which it is presented to patients. PROMs may be obtained with the use of surveys delivered via electronic or non–electronic-based methods. This can include phone calls, mail or paper surveys, e-mail surveys, or SMS (ie, Short Message/Messaging) responses. Overall, an intervention of any type demonstrated improvement in response rate from an average of 44.6% to 70.6% across all studies that used an intervention. Upon further analysis across 8 studies that used phone call-, electronic-, and mail-based interventions, phone call demonstrated the greatest compliance rate (71.5%) as compared with paper (57.6%) or electronic (53.2%). In a study by Schwartzenberger et al.15 that implemented an RCT comparing phone, e-mail, and mail, they observed similar results, with telephone PROM collection having the greatest rate of compliance (64%) as compared with e-mail or mail (42% each). This may demonstrate the impact of personalized follow-up on compliance. Patients may feel more inclined to fill out a PROM survey when they are being directly asked.

Another consideration is that PROM surveys often contain medical jargon that is unfamiliar to patients, or patients may be unsure as to what particular PROM survey items are asking. Phone calls may help to address this potential issue and lead to an increase in compliance. This concept of personalized follow-up was further reinforced in one particular study by Tariq et al.,12 which used a last resort method of a personalized surgeon letter to individuals who did not initially respond to any interventions for follow up. They observed a 20% response rate in the intervention group as compared with 1.4% response rate in the control group that did not receive this letter.

We believe that this systematic review has strengths that may help to inform future orthopaedic research. We identified various patient-specific factors that may improve or reduce PROM compliance. In addition, this study was able to identify different means of intervention that could potentially lead to improved rates of compliance in PROMs collection.

It is important that orthopaedic researchers are aware of the potential impact that patient demographics may have on PROMs compliance. As reported within our study, male sex, extremes of age, and non-White race were cited as the most-common patient demographics associated with poor compliance rate. Early identification of these patients in the preoperative setting may be prudent, as focusing on these populations may generate different strategies that can be implemented to improve compliance within these groups moving forward. For example, in the younger population, it may be beneficial to obtain PROMs via SMS. As we move forward in a digital world in which the upcoming generations are being introduced to devices and internet access at a younger age, the use of electronic-based PROM surveys may soon become the norm.

Along these lines, orthopaedic researchers also should be aware of different interventions that may improve PROMs compliance. Patients can invariably be lost to follow-up for various reasons that may exist outside of a controlled research setting. As observed across many studies included in our review, phone calls, e-mails, and mail surveys represent successful methods that can lead to greater PROM response rates.

Limitations

There are several limitations that should be considered. The initial review process was conducted with 2 independent reviewers with 2 rounds of the screening process. Although this study design allowed for greater discretion of the proposed inclusion criteria, it is still possible that several studies may have been excluded unknowingly. In addition, several studies that cleared the initial screening process were ultimately not included in the final analysis due to unclear descriptions of patient characteristics or response rates. The vast majority of studies included for analysis were observational cohort studies, either prospective or retrospective, thus demonstrating only Level II or III evidence. Only 5 of the 97 total studies were randomized controlled trials demonstrating Level I evidence. It is also important to note that while the scope of this review was broad across general orthopaedic research, this also led to a heterogeneity of study designs that made it difficult to assess differences between studies. Some studies used broad PROMs such as EQ-5D or Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System computer adaptive testing, whereas other studies reported subspecialty specific PROMs such as Boston Carpal Tunnel Questionnaire or the Oxford Hip and Knee Score. It is difficult to discern whether PROMs response rates may vary depending on the type of PROM that is used.

Conclusions

The response rates for PROMs vary across the orthopaedic literature. Patient-specific factors, such as age (young or old) and race (non-White), may contribute to poor PROM response rate. Reminders and interventions significantly improve PROM response rates.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Abigail Mitchell, M.S. O.T.R./L., and Amy Loveland, M.A., C.C.R.C for their part of the Orthopaedic Research Department and for their assistance in creating the idea, connecting with the right people, and organizing for the manuscript submission.

Footnotes

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: S.S reports Chair, DSMB for the Surgical Timing and Rehabilitation (STaR) for Multiple Ligament Knee Injuries (MLKI): A Multicenter Integrated Clinical Trial, Department of Defense W81XWH-17-2-0073; member, AAOS Sports Medicine/Arthroscopy Program Committee; and member, Editorial Board, Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. W.D. reports philanthropic gift from New Clip Technics in support of knee preservation ($500,000). Payments made to institution; consulting fees from Arthrex; research grant funding, consulting fees for speaking, travel and presentations from Arthrex; and professional fees for chart reviews and depositions from Gleason Flynn, Emig and McAfee Attorneys at Law. J.D. reports payment for expert witness case review. All other authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. Full ICMJE author disclosure forms are available for this article online, as supplementary material.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Gibbs D., Toop N., Grossbach A.J., et al. Electronic versus paper patient-reported outcome measure compliance rates: A retrospective analysis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2023;226 doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2023.107618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basch E. Patient-Reported Outcomes—harnessing patients’ voices to improve clinical care. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:105–108. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1611252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Squitieri L., Bozic K.J., Pusic A.L. The role of patient-reported outcome measures in value-based payment reform. Value Health. 2017;20:834–836. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maruszczyk K., Aiyegbusi O.L., Torlinska B., Collis P., Keeley T., Calvert M.J. Systematic review of guidance for the collection and use of patient-reported outcomes in real-world evidence generation to support regulation, reimbursement and health policy. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2022;6:57. doi: 10.1186/s41687-022-00466-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porter M.E., Teisberg E.O. Harvard Business Press; Boston: 2006. Redefining health care: creating value-based competition on results. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siljander M.P., McQuivey K.S., Fahs A.M., Galasso L.A., Serdahely K.J., Karadsheh M.S. Current trends in patient-reported outcome measures in total joint arthroplasty: A study of 4 major orthopaedic journals. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:3416–3421. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neve O.M., van Benthem P.P.G., Stiggelbout A.M., Hensen E.F. Response rate of patient reported outcomes: The delivery method matters. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21:220. doi: 10.1186/s12874-021-01419-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gagnier J.J. Patient reported outcomes in orthopaedics. J Orthop Res. 2017;35:2098–2108. doi: 10.1002/jor.23604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster A., Croot L., Brazier J., Harris J., O’Cathain A. The facilitators and barriers to implementing patient reported outcome measures in organisations delivering health related services: A systematic review of reviews. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2018;2:46. doi: 10.1186/s41687-018-0072-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warwick H., Hutyra C., Politzer C., et al. Small social incentives did not improve the survey response rate of patients who underwent orthopaedic surgery: A randomized trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477:1648–1656. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tariq M.B., Jones M.H., Strnad G., Sosic E., Cleveland Clinic OME Sports Health. Spindler K.P. A last-ditch effort and personalized surgeon letter improves PROMs follow-up rate in sports medicine patients: A crossover randomized controlled trial. J Knee Surg. 2021;34:130–136. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1694057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yedulla N.R., Hester J.D., Patel M.M., Cross A.G., Peterson E.L., Makhni E.C. Pre-visit digital messaging improves patient-reported outcome measure participation prior to the orthopaedic ambulatory visit: Results from a double-blinded, prospective, randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2023;105:20–26. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.21.00506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Littlewood C., Bateman M., Butler-Walley S., et al. Rehabilitation following rotator cuff repair: A multi-centre pilot & feasibility randomised controlled trial (RaCeR) Clin Rehabil. 2021;35:829–839. doi: 10.1177/0269215520978859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartzenberger J., Presson A., Lyle A., O’Farrell A., Tyser A.R. Remote collection of patient-reported outcomes following outpatient hand surgery: A randomized trial of telephone, mail, and e-mail. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42:693–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bot A.G.J., Anderson J.A., Neuhaus V., Ring D. Factors associated with survey response in hand surgery research. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:3237–3242. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3126-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juto H., Gärtner Nilsson M., Möller M., Wennergren D., Morberg P. Evaluating non-responders of a survey in the Swedish fracture register: no indication of different functional result. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18:278. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1634-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mellor X., Buczek M.J., Adams A.J., Lawrence J.T.R., Ganley T.J., Shah A.S. Collection of common knee patient-reported outcome instruments by automated mobile phone text messaging in pediatric sports medicine. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020;40:e91–e95. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Randsborg P.H., Adamec D., Cepeda N.A., Pearle A., Ranawat A. Differences in baseline characteristics and outcome among responders, late responders, and never-responders after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2021;49:3809–3815. doi: 10.1177/03635465211047858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reinholdsson J., Kraus-Schmitz J., Forssblad M., Edman G., Byttner M., Stålman A. A non-response analysis of 2-year data in the Swedish Knee Ligament Register. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:2481–2487. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3969-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zakaria H.M., Mansour T., Telemi E., et al. Patient demographic and surgical factors that affect completion of patient-reported outcomes 90 days and 1 year after spine surgery: Analysis from the Michigan Spine Surgery Improvement Collaborative (MSSIC) World Neurosurg. 2019;130:e259–e271. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poulsen E., Lund B., Roos E.M. The Danish Hip Arthroscopy Registry: Registration completeness and patient characteristics between responders and non-responders. Clin Epidemiol. 2020;12:825–833. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S264683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borowsky P.A., Kadri O.M., Meldau J.E., Blanchett J., Makhni E.C. The remote completion rate of electronic patient-reported outcome forms before scheduled clinic visits—a proof-of-concept study using patient-reported outcome measurement information system computer adaptive test questionnaires. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2019;3(10) doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-19-00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X.H., Li S.C., Xie F., et al. An exploratory study of response shift in health-related quality of life and utility assessment among patients with osteoarthritis undergoing total knee replacement surgery in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Value Health. 2012;15(1 suppl):S72–S78. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Briggs M., Closs J.S. A descriptive study of the use of visual analogue scales and verbal rating scales for the assessment of postoperative pain in orthopedic patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18:438–446. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jildeh T.R., Castle J.P., Abbas M.J., Dash M.E., Akioyamen N.O., Okoroha K.R. Age significantly affects response rate to outcomes questionnaires using mobile messaging software. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2021;3:e1349–e1358. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2021.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paulsen A., Pedersen A.B., Overgaard S., Roos E.M. Feasibility of 4 patient-reported outcome measures in a registry setting. Acta Orthop. 2012;83:321–327. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.702390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schamber E.M., Takemoto S.K., Chenok K.E., Bozic K.J. Barriers to completion of patient reported outcome measures. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:1449–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lizzio V.A., Blanchett J., Borowsky P., et al. Feasibility of PROMIS CAT administration in the ambulatory sports medicine clinic with respect to cost and patient compliance: A single-surgeon experience. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019;7 doi: 10.1177/2325967118821875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robertsson O., Dunbar M.J. Patient satisfaction compared with general health and disease-specific questionnaires in knee arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:476–482. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.22395a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagner M., Neururer S., Dammerer D., et al. External validation of the Tyrolean hip arthroplasty registry. J Exp Orthop. 2022;9:87. doi: 10.1186/s40634-022-00526-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernstein D.N., Karhade A.V., Bono C.M., Schwab J.H., Harris M.B., Tobert D.G. Sociodemographic factors are associated with patient-reported outcome measure completion in orthopaedic surgery: An analysis of completion rates and determinants among new patients. JB JS Open Access. 2022;7 doi: 10.2106/JBJS.OA.22.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou X., Karia R., Iorio R., Zuckerman J., Slover J., Band P. Combined email and in-office technology improves patient reported outcomes collection in standard orthopaedic care. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22:S191. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sajak P.M., Aneizi A., Gopinath R., et al. Factors associated with early postoperative survey completion in orthopaedic surgery patients. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020;11(suppl 1):S158–S163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2019.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weir T.B., Zhang T., Jauregui J.J., et al. Press Ganey surveys in patients undergoing upper-extremity surgical procedures: Response rate and evidence of nonresponse bias. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2021;103:1598–1603. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.20.01467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kadiyala J., Zhang T., Aneizi A., et al. Preoperative factors associated with 2-year postoperative survey completion in knee surgery patients. J Knee Surg. 2022;35:1320–1325. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1723764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon S.K., Kang Y.G., Chang C.B., Sung S.C., Kim T.K. Interpretations of the clinical outcomes of the nonresponders to mail surveys in patients after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cotter E.J., Hannon C.P., Locker P., et al. Male sex, decreased activity level, and higher BMI associated with lower completion of patient-reported outcome measures following ACL reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6 doi: 10.1177/2325967118758602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Polk A., Rasmussen J.V., Brorson S., Olsen B.S. Reliability of patient-reported functional outcome in a joint replacement registry. A comparison of primary responders and non-responders in the Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry. Acta Orthop. 2013;84:12–17. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.765622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nixon D.C., Zhang C., Weinberg M.W., Presson A.P., Nickisch F. Relationship of press ganey satisfaction and PROMIS function and pain in foot and ankle patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2020;41:1206–1211. doi: 10.1177/1071100720937013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang T, Schneider MB, Weir TB, et al. Response bias for press ganey ambulatory surgery surveys after knee surgery. J Knee Surg. 2023;36:1034–1042. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1748896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roysam GS, Hill A, Jagonase L, Purushothaman B, Cross A, Lakshmanan P. Two years following implementation of the British Spinal Registry (BSR) in a District General Hospital (DGH): perils, problems and PROMS. Spine J. 2016;16:S79. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rothrock N., Barnard C., Bhatt S., et al. Evaluation of the implementation of PROMIS CAT batteries for total joint arthroplasty in an electronic health record. Presentation at the International Society for Quality of Life Research. Dublin, Ireland, October 2018. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:S30. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1946-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lovelock T., O’Brien M., Young I., Broughton N. Two and a half years on: data and experiences establishing a “Virtual Clinic” for joint replacement follow up. ANZ J Surg. 2018 doi: 10.1111/ans.14752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harris I.A., Peng Y., Cashman K., et al. Association between patient factors and hospital completeness of a patient-reported outcome measures program in joint arthroplasty, a cohort study. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2022;6:32. doi: 10.1186/s41687-022-00441-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bojcic J.L., Sue V.M., Huon T.S., Maletis G.B., Inacio M.C. Comparison of paper and electronic surveys for measuring patient-reported outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Perm J. 2014;18:22–26. doi: 10.7812/TPP/13-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Besalduch-Balaguer M., Aguilera-Roig X., Urrútia-Cuchí G., et al. Level of response to telematic questionnaires on Health Related Quality of Life on total knee replacement. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.recot.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bohm E.R., Kirby S., Trepman E., et al. Collection and reporting of patient-reported outcome measures in arthroplasty registries: multinational survey and recommendations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021;479:2151–2166. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Triplet J.J., Momoh E., Kurowicki J., Villarroel L.D., Law T.Y., Levy J.C. E-mail reminders improve completion rates of patient-reported outcome measures. JSES Open Access. 2017;1:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jses.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Molloy I.B., Yong T.M., Keswani A., et al. Do medicare’s patient-reported outcome measures collection windows accurately reflect academic clinical practice. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:911–917. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ling D.I., Finocchiaro A., Schneider B., Lai E., Dines J., Gulotta L. What factors are associated with patient-reported outcome measure questionnaire completion for an electronic shoulder arthroplasty registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021;479:142–147. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Westenberg R.F., Nierich J., Lans J., Garg R., Eberlin K.R., Chen N.C. What factors are associated with response rates for long-term follow-up questionnaire studies in hand surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478:2889–2898. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barnds B., Witt A., Orahovats A., Schlegel T., Hunt K. The effects of a pandemic on patient engagement in a patient-reported outcome platform at orthopaedic sports medicine centers (106) Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9(10_suppl5) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elsabeh R., Delgado K., Das K., et al. Utilization of an automated SMS-based electronic patient-reported outcome tool in spinal surgery patients. Spine J. 2021;21:S115. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perdomo-Pantoja A., Alomari S., Lubelski D., et al. Implementation of an automated text message-based system for tracking patient-reported outcomes in spine surgery: an overview of the concept and our early experience. World Neurosurg. 2022;158:e746–e753. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barai A., Lambie B., Cosgrave C., Baxter J. Management of distal radius fractures in the emergency department: a long-term functional outcome measure study with the disabilities of arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) scores. Emerg Med Australas. 2018;30(4):530–537. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Makhni E.C., Higgins J.D., Hamamoto J.T., Cole B.J., Romeo A.A., Verma N.N. Patient compliance with electronic patient reported outcomes following shoulder arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2017;33:1940–1946. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whitehouse M.R., Masri B.A., Duncan C.P., Garbuz D.S. Continued good results with modular trabecular metal augments for acetabular defects in hip arthroplasty at 7 to 11 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:521–527. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3861-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clarnette R., Graves S., Lekkas C. Overview of the AOA national joint replacement registry. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(2_suppl) [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matthews A., Evans J.P. Evaluating the measures in patient-reported outcomes, values and experiences (EMPROVE study): a collaborative audit of PROMs practice in orthopaedic care in the United Kingdom. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2023;105:357–364. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2022.0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Franko O.I., London D.A., Kiefhaber T.R., Stern P.J. Automated reporting of patient outcomes in hand surgery: a pilot study. Hand (N Y) 2022;17:1278–1285. doi: 10.1177/15589447211043214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shapiro L.M., Eppler S.L., Roe A.K., Morris A., Kamal R.N. The patient perspective on patient-reported outcome measures following elective hand surgery: a convergent mixed-methods analysis. J Hand Surg Am. 2021;46:153.e1–153.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2020.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barker K.L., Frost H., MacDonald W.J., Fairbank J.C. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation or surgery for chronic low back pain - 7 year follow up of a randomised controlled trial: 25. Spine J Meeting Abstract. 2010:25. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bhatt S., Davis K., Manning D.W., Barnard C., Peabody T.D., Rothrock N.E. Integration of patient-reported outcomes in a total joint arthroplasty program at a high-volume academic medical center. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2020;4 doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-20-00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olach M. Feasibility of web-based patient-reported outcome assessment after arthroscopic knee surgery: the patients. Swiss Medical Weekly [Preprint]; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wylde V., Blom A.W., Whitehouse S.L., Taylor A.H., Pattison G.T., Bannister G.C. Patient-reported outcomes after total hip and knee arthroplasty: comparison of midterm results. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tokish J.M., Chisholm J.N., Bottoni C.R., Groth A.T., Chen W., Orchowski J.R. Implementing an electronic patient-based orthopaedic outcomes system: factors affecting patient participation compliance. Mil Med. 2017;182:e1626–e1630. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rubery P. Standard of care PRO collection across a healthcare system. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:1–190. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1946-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thoma A., Levis C., Patel P., Murphy J., Duku E. Partial versus total trapeziectomy thumb arthroplasty: an expertise-based feasibility study. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6 doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shu H.T., Bodendorfer B.M., Folgueras C.A., Argintar E.H. Follow-up compliance and outcomes of knee ligamentous reconstruction or repair patients enrolled in an electronic versus a traditional follow-up protocol. Orthopedics. 2018;41:e718–e723. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20180828-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Risberg M., Tryggestad C., Nordsletten L., Engebretsen L., Holm I. Active living with osteoarthritis implementation of evidence-based guidelines as first-line treatment for patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartil. 2018;26:S34. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gakhar H., McConnell B., Apostolopoulos A.P., Lewis P. A pilot study investigating the use of at-home, web-based questionnaires compiling patient-reported outcome measures following total hip and knee replacement surgeries. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2013;23:39–43. doi: 10.1615/jlongtermeffmedimplants.2013008024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van der Vliet Q.M.J., Sweet A.A.R., Bhashyam A.R., et al. Polytrauma and high-energy injury mechanisms are associated with worse patient-reported outcomes after distal radius fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477:2267–2275. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000000757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tilbury C., Leichtenberg C.S., Kaptein B.L., et al. Feasibility of collecting multiple patient-reported outcome measures alongside the dutch arthroplasty register. J Patient Exp. 2020;7:484–492. doi: 10.1177/2374373519853166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leonardsson O., Rolfson O., Hommel A., Garellick G., Åkesson K., Rogmark C. Patient-reported outcome after displaced femoral neck fracture: a national survey of 4467 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1693–1699. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Slover J.D., Karia R.J., Hauer C., Gelber Z., Band P.A., Graham J. Feasibility of integrating standardized patient-reported outcomes in orthopedic care. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:e494–e500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ho A., Purdie C., Tirosh O., Tran P. Improving the response rate of patient-reported outcome measures in an Australian tertiary metropolitan hospital. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2019;10:217–226. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S162476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ackerman I.N., Cavka B., Lippa J., Bucknill A. The feasibility of implementing the ICHOM standard set for hip and knee osteoarthritis: a mixed-methods evaluation in public and private hospital settings. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2017;2:32. doi: 10.1186/s41687-018-0062-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pronk Y., Pilot P., Brinkman J.M., van Heerwaarden R.J., van der Weegen W. Response rate and costs for automated patient-reported outcomes collection alone compared to combined automated and manual collection. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2019;3:31. doi: 10.1186/s41687-019-0121-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hajewski C., Anthony C.A., Rojas E.O., Westermann R., Willey M. Detailing postoperative pain and opioid utilization after periacetabular osteotomy with automated mobile messaging. J Hip Preserv Surg. 2019;6:370–376. doi: 10.1093/jhps/hnz049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ross L.A., O’Rourke S.C., Toland G., MacDonald D.J., Clement N.D., Scott C.E.H. Loss to patient-reported outcome measure follow-up after hip arthroplasty and knee arthroplasty : patient satisfaction, associations with non-response, and maximizing returns. Bone Jt Open. 2022;3:275–283. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.34.BJO-2022-0013.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sepucha K.R., Atlas S.J., Chang Y., et al. Informed, patient-centered decisions associated with better health outcomes in orthopedics: prospective cohort study. Med Decis Making. 2018;38:1018–1026. doi: 10.1177/0272989X18801308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Spindler K., Jin Y., Jones M. Paper 86: Symptoms of post-traumatic osteoarthritis remain stable up to 10 years after ACL reconstruction. Orthopaedic J Sports Med. 2022;10(7_suppl5) [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fitzpatrick R., Morris R., Hajat S., et al. The value of short and simple measures to assess outcomes for patients of total hip replacement surgery. Qual Health Care. 2000;9:146–150. doi: 10.1136/qhc.9.3.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tariq M.B., Vega J.F., Westermann R., Jones M., Spindler K.P. Arthroplasty studies with greater than 1000 participants: analysis of follow-up methods. Arthroplast Today. 2019;5:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bell K., Warnick E., Nicholson K., et al. Patient adoption and utilization of a web-based and mobile-based portal for collecting outcomes after elective orthopedic surgery. Am J Med Qual. 2018;33:649–656.s. doi: 10.1177/1062860618765083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Palmen L.N., Schrier J.C., Scholten R., Jansen J.H., Koëter S. Is it too early to move to full electronic PROM data collection?: A randomized controlled trial comparing PROM’s after hallux valgus captured by e-mail, traditional mail and telephone. Foot Ankle Surg. 2016;22:46–49. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fife J., McGee A., Swantek A., Makhni E. Paper 78: Integrating PROM Collection for Shoulder Surgical Patients through the Electronic Medical Record: A Low Cost and Effective Strategy for High Fidelity PROM Collection. Orthopaed J Sports Med. 2022;10(7_suppl5) [Google Scholar]

- 89.Harris K.K., Dawson J., Jones L.D., Beard D.J., Price A.J. Extending the use of PROMs in the NHS—using the Oxford Knee Score in patients undergoing non-operative management for knee osteoarthritis: a validation study. BMJ Open. 2013;3 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Haskell A., Kim T. Implementation of patient-reported outcomes measurement information system data collection in a private orthopedic surgery practice. Foot Ankle Int. 2018;39:517–521. doi: 10.1177/1071100717753967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Whitehouse S.L., Blom A.W., Taylor A.H., Pattison G.T., Bannister G.C. The Oxford Knee Score; problems and pitfalls. Knee. 2005;12:287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Papakostidou I., Dailiana Z.H., Papapolychroniou T., et al. Factors affecting the quality of life after total knee arthroplasties: a prospective study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Marx R.G., Wolfe I.A., Turner B.E., Huston L.J., Taber C.E., Spindler K.P. MOON’s strategy for obtaining over eighty percent follow-up at 10 years following ACL reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022;104:e7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.21.00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Baeesa S.S. Cervical disc arthroplasty for degenerative disc disease: two-year follow-up from an international prospective, multicenter, observational study. Spine J. 2015;15:S233. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rolfson O., Salomonsson R., Dahlberg L.E., Garellick G. Internet-based follow-up questionnaire for measuring patient-reported outcome after total hip replacement surgery-reliability and response rate. Value Health. 2011;14:316–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Owen R.J., Zebala L.P., Peters C., McAnany S. PROMIS Physical function correlation with NDI and mJOA in the surgical cervical myelopathy patient population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018;43:550–555. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pronk Y., van der Weegen W., Vos R., Brinkman J.M., van Heerwaarden R.J., Pilot P. What is the minimum response rate on patient-reported outcome measures needed to adequately evaluate total hip arthroplasties. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:379. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01628-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Scott E.J., Anthony C.A., Rooney P., Lynch T.S., Willey M.C., Westermann R.W. Mobile phone administration of hip-specific patient-reported outcome instruments correlates highly with in-office administration. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28:e41–e46. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-18-00708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nguyen J., Marx R., Hidaka C., Wilson S., Lyman S. Validation of electronic administration of knee surveys among ACL-injured patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:3116–3122. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Owen R.J., Khan A.Z., McAnany S.J., Peters C., Zebala L.P. PROMIS correlation with NDI and VAS measurements of physical function and pain in surgical patients with cervical disc herniations and radiculopathy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2019:1–6. doi: 10.3171/2019.4.SPINE18422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sierakowski K.L., Dean N.R., Mohan R., John M., Griffin P.A., Bain G.I. Prospective randomized cohort study to explore the acceptability of patient-reported outcome measures to patients of hand clinics. J Hand Surg Glob Online. 2020;2:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsg.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nagappa M., Querney J., Martin J., et al. Perioperative satisfaction and health economic questionnaires in patients undergoing an elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a prospective observational cohort study. Anesth Essays Res. 2021;15:413–438. doi: 10.4103/aer.aer_5_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Karia R., Slover J., Hauer C., Gelber Z., Band P.., Graham J. Networking to capture patient-reported outcomes during routine orthopaedic care across two distinct institutions. Osteoarthritis Cartil. 2013;21:S142. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Slover J.D., Karia R.J., Hauer C., Gelber Z., Band P.A., Graham J. Feasibility of integrating standardized patient-reported outcomes in orthopedic care. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:e494–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lyman S., Hidaka C., Fields K., Islam W., Mayman D. Monitoring patient recovery after THA or TKA using mobile technology. HSS J. 2020;16(Suppl 2):358–365. doi: 10.1007/s11420-019-09746-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Olley L.M., Carr A.J. The use of a patient-based questionnaire (the Oxford Shoulder Score) to assess outcome after rotator cuff repair. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008;90:326–331. doi: 10.1308/003588408X285964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shapiro L.M., Đình M.P., Tran L., Fox P.M., Richard M.J., Kamal R.N. Short message service-based collection of patient-reported outcome measures on hand surgery global outreach trips: a pilot feasibility study. J Hand Surg Am. 2022;47:384.e1–384.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2021.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.