Abstract

Background and Aims:

Glucocorticoids are commonly utilised as adjuvants to enhance nerve block quality and prolong the analgesic duration. Its systemic effects, after a single-injection adductor canal block (ACB) followed by a continuous infusion, are unclear. The aim of the study was to assess the systemic effects of a single dose of dexamethasone sodium phosphate (DEX), or a combination of DEX and methylprednisolone acetate (MPA), on fasting blood glucose (FBG) and white blood cell count (WBC) when administered perineurally via ACB.

Material and Methods:

A single-center retrospective study on total knee arthroplasty (TKA) was performed and a total of 95 patients were included in the final analysis. Patients were divided into three groups based on adjuvants received in ACB: Control group (N = 41) and two treatment groups, DEX group (N = 33) and DEX/MPA group (N = 21). Our primary outcomes were the change of FBG from its preoperative baseline value on postoperative day (POD) 2. The secondary outcomes included change of FBG on POD 0 and POD 1, and change of WBC on POD 0, POD 1, and POD 2.

Results:

The FBG change from baseline in the DEX group was significantly higher than that in the control group (difference = 14.04, 95% CI: 1.3 to 26.77), P = 0.031) on POD 0. The WBC change from baseline in the DEX/MPA group was statistically significant higher than control on POD 0 (2.62 (1.52 to 3.37), P < 0.0001). No significant differences between DEX and DEX/MPA group were found on any given postoperative days for FBG and WBC.

Conclusion:

This study provided preliminary safety data on the use of a combination of glucocorticoids with hydrophilic (DEX) and lipophilic (MPA) properties as local anesthetic adjuvants in ACB, which induced similar levels of changes on FBG and WBC as those from both control and DEX alone group.

Keywords: Continuous adductor canal block, Depo-Medrol, dexamethasone, methylprednisolone acetate, perineural glucocorticoid, total knee arthroplasty

Introduction

Total-knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a highly effective orthopedic surgery used to improve pain control and functional status in patients with severe end-stage knee osteoarthritis.[1] Optimal pain control during the perioperative period is vital, and as such, peripheral nerve blocks are often used as part of the multimodal analgesia treatment plan for postoperative pain control. The duration of the block is usually the limiting factor. Consequently, in order to achieve satisfactory pain relief and prolong the duration of the block, adjuvants such as glucocorticoids, opioids, alpha-2 agonists are utilized.[2] The addition of glucocorticoids in patients undergoing TKA has not only been shown to reduce pain in the early postoperative period but also allows for improved prosthetic knee range of motion as measured by the ability of patients to regain knee flexion more quickly.[3] Perineural hydrophilic glucocorticoid dexamethasone (DEX), is a favorable adjunct among the variety that has been studied as an adjuvant to local anesthetics and has been widely adopted, nonetheless off label, to prolong nerve block duration for hours with an instant onset.[4,5] Lipophilic methylprednisolone acetate (MPA) in the format of epidural and peripheral nerve block has been proven to be safe and effective in chronic pain management for days or weeks albeit with delayed onset for hours or days.[6,7] We, therefore, utilized DEX as the bridge to prolong the analgesic effects from ropivacaine until MPA started to take effect.

Common side effects from systemic glucocorticoids are well known and range from hyperglycemia, infection, psychosis, osteoporosis, to muscle wasting, and dermatologic signs. Despite increasing evidence on the efficacy and safety of glucocorticoids in total joint arthroplasty, there have been few studies in the literature on the systemic effects of perineural glucocorticoids. On the other hand, current evidence regarding adverse effects of perineurally administered glucocorticoids is sparse. Most randomized control trials and meta-analysis evaluating the perineural injections of glucocorticoids do not report any adverse effects of glucocorticoids as an outcome in any of the studies.[8] In this retrospective study, our primary aim is to assess the systemic effects of a single perineural dose of DEX or the combination of both DEX and MPA, through adductor canal block (ACB) on fasting blood glucose (FBG) and white blood cell count (WBC). Our working hypothesis is that systemic effects from a perineurally administered combination of glucocorticoids with different onset times, DEX and MPA, will not be significantly different from that of DEX alone due to the depo nature of MPA.

Material and Methods

With institutional review board approval (HIC#2000022995, March 30, 2018), a retrospective chart review was performed on consecutive patients who underwent TKA at a single academic institution, and 95 patients were included in the final analysis. Due to its nature being a retrospective study, sample size calculation was not utilised in study design, rather a predefined timeline, between January 2016 and June 2017, and a set of criteria were used to select study candidates. Inclusion criteria were elective, primary, and unilateral TKA who received continuous ACB preoperatively and spinal anesthesia intraoperatively. Exclusion criteria were: bilateral or revision TKA, surgical history in the ipsilateral knee, receipt of other nerve blocks in addition to ACB preoperatively or general anesthesia intraoperatively, chronic pain, chronic opioid use, Diabetes Mellitus type I (DM I), or poorly controlled Diabetes Mellitus type II (DM II) defined as on home insulin, HbA1C more than 8% or FBG equal to or more than 200 mg/dL on the day of surgery, patients who received any additional glucocorticoids in any format. Descriptive data regarding past medical history were assimilated. Preoperative ultrasound-guided continuous ACB was carried out per standard of care; ASA standard monitors were applied and minor sedation with 1-2 mg midazolam and/or 50-100 mcg fentanyl was administered intravenously as needed. The ACB blocks were performed or supervised by different attending anesthesiologists specialized in regional anesthesia and the choice of adjuvants, DEX alone, or DEX/MPA combination, was at their individual discretion. Intraoperatively all subjects received spinal anesthesia with 0.5% plain bupivacaine 2-3 mL for surgical anesthesia under standard ASA monitors and sedation with midazolam, fentanyl, and/or propofol as needed. The surgeons performed posterior knee joint injection at the end of the surgery with medications of individual choice but without glucocorticoids.

Multimodal pain management was implemented perioperatively, consisting of a combination of continuous ACB, scheduled oral acetaminophen, and Celecoxib, with oral or intravenous opioids for breakthrough pain. The adductor canal catheter was connected to a CADD pump (Smiths Medical, Dublin, OH, USA) for 48 hours upon arrival in the recovery room. The patient-controlled nerve block analgesia (PCNA) was set at a patient-controlled bolus of 5 mL 0.2% ropivacaine with a 15 -minute lockout interval, basal infusion at 0-8 ml/hr, managed by the acute pain service, and titrated to pain less than 5/10 on the VAS scale. Opioid analgesic usage based on pain score and titrated to patient need in the format of intravenous hydromorphone or oral oxycodone was documented as milligram morphine equivalent (MME). Routine complete blood count and basic metabolic panel were recorded daily on all patients whose WBC and FBG were tracked.

The patients were divided into three groups based on the adjuvants administered: those who only received 0.2% ropivacaine without any perineural glucocorticoids during the initial single injection block placement (control group), those who received 0.2% ropivacaine with either 5 mg DEX or a combination of 5 mg DEX and 40 mg MPA (DEX/MPA). Our primary outcomes were the change of FBG from its preoperative baseline value on the postoperative day (POD) 2. The secondary outcomes included: change of FBG on POD 0 and POD 1, and change of WBC on POD 0, POD 1, and POD 2.

Statistical analysis

Data were summarized as mean value and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables, and frequency (%) for categorical variables. For the univariate analyses, categorical variables among three groups were compared using the Chi-Square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

For our analyses of the repeatedly measured outcome FBG or WBC, separate linear mixed effects model was fit to evaluate the change from the baseline, in which the baseline value, time (e.g., POD 0, POD 1, POD 2), group (i.e., DEX vs. control, DEX/MPA vs. control, DEX vs. DEX/MPA), and time by group interaction were adjusted for as covariates, with an unstructured variance-covariance matrix specified to account for within-subject correlation. The mixed model method assumes data are missing at random, and patients will be included in the regression model if the baseline value and any of three follow-up time points of the outcome were available. To quantitate the magnitude of effect size between two groups, least square mean and 95% CI were reported at each time point. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. We used a sample of all eligible patients, and no a priori sample size calculation was performed for this retrospective study.

Results

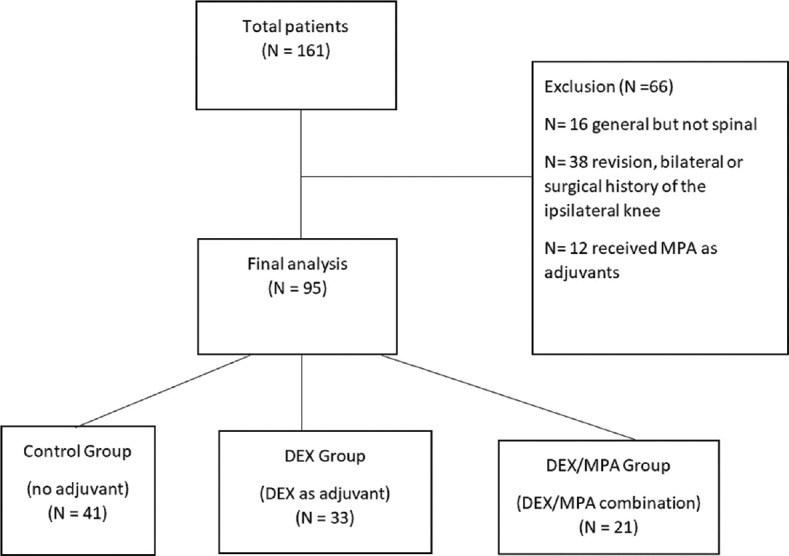

The STROBE diagram of screened and excluded patients is shown in Figure 1. There were 21, 33 and 41 patients included in the DEX/MAP group, DEX group and Control Group, respectively. Patient age, gender, race, smoker status, and BMI were comparable among three groups [Table 1]. The ASA status was significantly different among three groups with more patients in ASA 3-4 category in the DEX group (58% vs. 29% in DEX/MPA vs 27% in control, P = 0.015). There was a significant difference in preoperative FBG (P = 0.002) among the three groups, but preoperative WBC was comparable (P = 0.28).

Figure 1.

STROBE flowchart of screened and excluded patients

Table 1.

Study patient demographics and baseline laboratory values

| Characteristics | Control (n=41) | DEX only (n=33) | DEX and MPA (n=21) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 68.56 (10.38) | 71.64 (8.93) | 66.10 (10.30) | 0.13 |

| Sex, Female | 30 (73%) | 25 (76%) | 14 (67%) | 0.76 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 31.34 (6.66) | 31.58 (7.54) | 29.20 (5.43) | 0.40 |

| ASA Status Group | ||||

| 1-2 | 30 (73%) | 14 (42%) | 15 (71%) | 0.015 |

| 3-4 | 11 (27%) | 19 (58%) | 6 (29%) | |

| Race | ||||

| Asian | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) | 0.21 |

| Black or African American | 5 (12%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| White | 35 (85%) | 30 (94%) | 20 (95%) | |

| Current Smoker, Yes | 21 (51%) | 8 (24%) | 8 (38%) | 0.06 |

| Diabetes, Yes | 4 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.28 |

| Current EtOH, Yes | 26 (63%) | 25 (76%) | 13 (62%) | 0.44 |

| Neuropathy, Yes | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.50 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease, Yes | 3 (7%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.54 |

| Anxiety or Depression, Yes | 12 (31%) | 9 (27%) | 4 (20%) | 0.68 |

| Preop Glucose (mg/dL) | 93.73 (12.96) | 111.33 (35.72) | 109.33 (12.74) | 0.002 |

| Preop WBC (x1000/uL) | 6.78 (2.08) | 6.71 (2.99) | 8.48 (6.67) | 0.28 |

Data are presented as mean (SD), or n (%). BMI, body mass index; DEX, dexamethasone sodium phosphate; MPA, methylprednisolone acetate; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; EtOH, alcohol; Preop, preoperative baseline; WBC, white blood cell count; POD, postoperative day

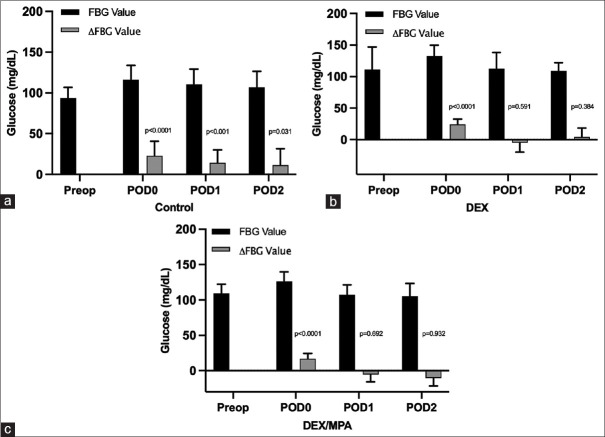

Raw values of FBG and changes from baseline on each postoperative day starting POD 0 through POD 2 were shown in Figure 2. The within-group changes of FBG from the baseline value were statistically significant (from null value of 0) on POD 0 (P < 0.0001), POD 1 (P < 0.001), and POD 2 (P = 0.031) in the control group, while a significant difference was only found on POD 0 in the DEX (P < 0.0001) and DEX/MPA group (P < 0.0001). Notably, the adjusted group-difference between DEX and Control was found statistically significant on day 0 (difference = 14.04, 95% CI: 1.3 to 26.77, P = 0.031) but not on POD 1 (P = 0.244) or POD 2 (P = 0.749) [Table 2]. No other significant group differences were found at any postoperative days between DEX/MPA and control group, and between the DEX/MPA and DEX group.

Figure 2.

Perioperative FBG absolute value and its changes from baseline in a: control group; b: DEX group; c: DEX/MPA group. FBG, fasting blood glucose; ΔFBG, change of FBG from preoperative baseline; DEX, dexamethasone, sodium phosphate; MPA, methylprednisolone acetate; Preop, preoperative; POD, postoperative day

Table 2.

Between-group comparison of fasting blood glucose (FBG) and white blood cell count (WBC)

| DEX vs. Control | DEX/MPA vs. Control | DEX/MPA vs. DEX | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Difference (95% CI) | P | Difference (95% CI) | P | Difference (95% CI) | P | |

| FBG change from baseline (mg/dL) | ||||||

| POD 0 | 14.04 (1.3-26.77) | 0.031 | 3.24 (-6.51-12.99) | 0.511 | -8.89 (-22.47-4.68) | 0.193 |

| POD 1 | -7.98 (-21.52-5.56) | 0.244 | -8.72 (-19.49-2.05) | 0.111 | 1.78 (-13.37-16.92) | 0.814 |

| POD 2 | -2.43 (-17.52-12.67) | 0.749 | -7.74 (-20.77-5.28) | 0.240 | -3.6 (-21.6-14.4) | 0.688 |

| WBC change from baseline (x1000/uL) | ||||||

| POD 0 | 1.04 (-0.35-2.42) | 0.141 | 2.62 (1.52-3.73) | <.0001 | 1.55 (-0.19-3.29) | 0.080 |

| POD 1 | -0.88 (-2.32-0.57) | 0.231 | -0.23 (-1.4-0.95) | 0.700 | 0.66 (-1.23-2.54) | 0.486 |

| POD 2 | -1.01 (-2.55-0.53) | 0.196 | -0.49 (-1.83-0.86) | 0.473 | 0.52 (-1.6-2.65) | 0.622 |

DEX, dexamethasone, sodium phosphate; MPA, methylprednisolone acetate; POD, postoperative day

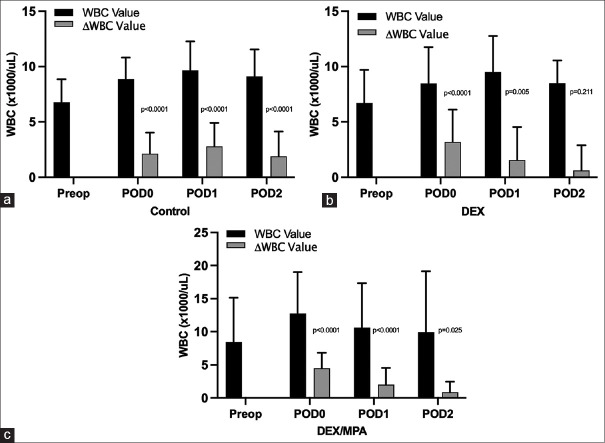

For the raw values of WBC and changes from baseline [Figure 3], statistically significant within-group differences were found on POD 0 and POD 1 for the DEX group, and on POD 0 through POD 2 for DEX/MPA and control group respectively. However, in terms of between-group difference, only one significant difference was found between DEX/MPA and control group at POD 0 (difference = 2.62, 95% CI: 1.52 to 3.73), P < 0.001). No other significant differences were found at any other time points for any of the two group comparisons among DEX/MPA, DEX, and the control group [Table 2].

Figure 3.

Perioperative white blood cell count absolute value and its changes from baseline in a: control group; b: DEX group; c: DEX/MPA group. WBC, white blood cell; ΔWBC, change of WBC from preoperative baseline; DEX, dexamethasone, sodium phosphate; MPA, methylprednisolone acetate; Preop, preoperative; POD, postoperative day

Discussion

This preliminary study indicated that TKA patients without perineural glucocorticoids may experience significant FBG elevation above the baseline level for at least the first 2 postoperative days, in a pattern similar to that in patients who received perineural DEX or DEX/MPA. This is supported by the lack of any difference between DEX/MPA and control group at any time points and only one-time point difference (POD 0) between DEX and control group. In addition, the changes in FBG were not statistically different on any given postoperative days in DEX/MPA group with the addition of 40 mg MPA when compared to 5 mg DEX alone. To our best knowledge, this is the first study that compared the systemic effects of perineural glucocorticoids with control, as well as compared DEX with a combination of glucocorticoids with different physiochemical properties (DEX plus MPA).

Perioperative FBG fluctuation following major surgeries such as TKA is not unheard of with and without pharmacological effects from glucocorticoids. The significance of the detailed analysis of perioperative FBG in this study was several folds. From within group analysis, we learned that the elevation of glucose in TKA may last at least 48 hours in patients who received spinal anesthesia intraoperatively and without perioperative glucocorticoids of any format, likely due to perioperative surgical stress. It would be interesting to see if the duration remains the same in TKA patients with general anesthesia. Also, we define ‘significant hyperglycemia’ to be an FBG greater than 140 mg/dL. This cut-off point is based on the results of a study by Ata et al.[9] who found that post-operative FBG >140 mg/dL is a strong predictor for surgical site infection, even though FDA gives a much higher cutoff of 200 mg/dL. Despite the statistically significant increase in FBG noted in both the control and adjuvant treatment groups, a clinically ‘significant hyperglycemia’ was not noted in our study. There were no cases of delayed wound healing or surgical site infections up to 90 days postoperatively.

Fluctuations of WBC after major surgeries such as TKA are to be expected. It should be noted that the highest absolute value rarely went above 13,000 × 1000/mm3 despite the variations observed, and the change from the baseline was relatively modest, thus glucocorticoid adjunct did not confer a significant deviation from physiologic range. This study not only verified what we know that glucocorticoids can transiently increase WBC, but this result also indicates the addition of depo format slow onset MPA at the dose of 40 mg in addition to the commonly used dose of 5 mg DEX did not result in significant changes on WBC.

We are very aware of the limitations of this study. Being a single center retrospective study, it is not devoid of the typical limitations associated with this methodology. First, no sample size calculation was pre-planned, and we had to use a convenient sample of available patients for analysis. Second, it is not possible for us to mitigate the confounding bias for this observational study. Even though the performance of ACB was standardised, and the posterior knee joint injections were performed by the surgeons at the end of the surgery, the medications administered were based on each provider’s choice. In particular, we are sharing the observations in the process of protocol generation for TKA. We first used the most common adjuvant, DEX, for which we were happy with the result, but it was clearly not sufficient by itself to sustain the transition from the continuous catheter to single injection, or from inpatient stay to ambulatory surgery. We tried MPA alone based on its long-acting effects in chronic pain and some evidence in acute pain, but we quickly realized its slow onset made it an unsuitable choice as the lone adjuvant for acute pain management, therefore we quickly stopped this arm. We next proceeded with the combination of DEX and MPA, based on the hypothesis that the systemic effects of combining two glucocorticoids with different physiochemical properties will not be significantly more than those from DEX alone due to the documented slow onset of MPA.

Furthermore, a longer duration of follow-up is needed to further evaluate the systemic effects of DEX or DEX/MPA on FBG and WBC. We only analyzed morning FBG which is consistently measured at standard time points in our institute postoperatively. However, it might be helpful to monitor postprandial glucose to obtain a complete picture of the systemic effects of perineural glucocorticoids on serum glucose. We were not able to monitor hemoglobin A1C as very few patients have these data. Nonetheless, based on the experience and data in this pilot study, our institute has significantly increased peripheral nerve block volume secondary to the transition from continuous ACB catheters to single injection using DEX/MPA combination, and selected motivated patients have been successfully discharged home on the day of TKA for the past several years. A future study with prespecified sample size and a thoughtful design to control for bias via a randomized trial is warranted.

Conclusion

In summary, this single-center retrospective study suggests DEX at the dose of 5 mg or DEX 5 mg/MPA 40 mg combination through ACB in TKA generated comparable levels of FBG elevation and WBC changes that were also close to the changes in the control group. This provided preliminary safety data for the first postoperative 48 hours supporting their usage in ACB for TKA.

Authors’ contribution

All the authors made a significant contribution to the work in study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and result interpretation, manuscript drafting, revising and critically reviewing the article.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. Richard Hintz and Mrs. Soundari Sureshanand at JDAT-Research, YCCI at Yale University School of Medicine for electronic medical record data acquisition.

The authors would like to thank the entire team of total joint arthroplasty surgeons at Yale New Haven Hospital, especially Dr. Lee Rubin, Dr. Michael Leslie, Dr. Mary O’Connor, Dr. Daniel Wiznia, Dr. Diren Arsoy, Dr. David Gibson, Dr. Michael Baumgartner, Dr. Joseph Wu, Dr. Michael Luchini, and Dr. Philip Luchini, who contributed their patients for the study.

References

- 1.Zachwieja EC, Perez J, Schneiderbauer M. Hip and knee arthroplasty in osteoarthritis. Curr Treat Options Rheumatol. 2017;3:75–87. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knight JB, Schott NJ, Kentor ML, Williams BA. Neurotoxicity of common peripheral nerve block adjuvants. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2015;28:598–604. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kulkarni M, Mallesh M, Wakankar H, Prajapati R, Pandit H. Effect of methylprednisolone in periarticular infiltration for primary total knee arthroplasty on pain and rehabilitation. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:1646–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albrecht E, Kern C, Kirkham KR. A systematic review and meta-analysis of perineural dexamethasone for peripheral nerve blocks. Anaesthesia. 2015;70:71–83. doi: 10.1111/anae.12823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirksey MA, Haskins SC, Cheng J, Liu SS. Local anesthetic peripheral nerve block adjuvants for prolongation of analgesia: A systematic qualitative review. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan JS, Rai A, Sundara Rajan R, Jackson TD, Bhatia A. A scoping review of perineural glucocorticoids for the treatment of chronic postoperative inguinal pain. Hernia. 2016;20:367–76. doi: 10.1007/s10029-016-1487-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shanahan EM, Ahern M, Smith M, Wetherall M, Bresnihan B, FitzGerald O. Suprascapular nerve block (using bupivacaine and methylprednisolone acetate) in chronic shoulder pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:400–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.5.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhatia A, Flamer D, Shah PS. Perineural steroids for trauma and compression-related peripheral neuropathic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2015;62:650–62. doi: 10.1007/s12630-015-0356-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ata A, Lee J, Bestle SL, Desemone J, Stain SC. Postoperative hyperglycemia and surgical site infection in general surgery patients. Arch Surg. 2010;145:858–64. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]