Abstract

Background

Dual-mobility (DM) total hip arthroplasty (THA) combines the stabilization advantage provided by large head articulation with the low friction advantage provided by small head articulation. There is momentum for DM to be used in a wider selection of patients, with some advocating for DM to be the routine primary total hip construct. Further investigation is needed to determine whether the use of DM in younger adults is validated by aggregate data. Our objective was to review the literature for the clinical performance of DM THA in patients aged 55 years and younger.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was performed according to the guidelines of Preferred Reporting in Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Inclusion in the review required clinical outcome reporting for DM primary THA in ambulatory patients aged 55 years or younger. The risk of bias was appraised using the Cochrane risk of bias in nonrandomized studies of interventions and the quality of the evidence was appraised using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation framework.

Results

Across a sample of 1048 cases, the frequency weighted term of follow-up was 87.7 months. The pooled rate of revision was 9.5%. The Harris Hip Score significantly improved from 49.1 preoperatively to 93 postoperatively. The Postel-Merle d'Aubigné score significantly improved from 10.5 preoperatively to 17.1 postoperatively.

Conclusions

The literature demonstrates satisfactory short-term outcomes with a mitigated risk of dislocation for DM used as primary THA in patients aged 55 years and younger. The current findings suggest that third-generation designs provide reduced rates of intraprosthetic dislocation and improved survivorship.

Keywords: Dual mobility, Hip dislocation, Hip osteoarthritis, Large femoral head, Osteonecrosis femoral head, Total hip arthroplasty

Introduction

Dual-mobility (DM) total hip arthroplasty (THA) combines the stabilization advantage provided by large head articulation with the low friction advantage provided by small head articulation. Bosquet and Rambert are credited with developing the dual articulation concept in France in 1974, with the intent to improve stability and reduce the risk of dislocation. Aggregate data have confirmed the stabilizing advantage of DM in primary and revision THA [1]. Utilization of DM substantially increased throughout the mid-2010s in primary and revision THA, in part due to the approval for use in the United States [2]. There is reasonable expectation for DM utilization to continue to rise given the projections for increasing rates of primary and revision THA into the 2030s [3,4].

DM design has evolved due to material innovation and further understanding of the inherent characteristics. Although initially regarded as a dual articulation construct, novel designs considered the importance of the third articulation between the femoral neck and polyethylene liner [5]. Ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene has been shown to reduce the particulate wear in THA [6]. These improved wear characteristics may carry additional importance in DM due to the multiple articulations. Although the advent of modular DM allows surgeons to supplement acetabular fixation with screws, micromotion between the metal liner and acetabular shell may produce metallic wear debris and subsequent metallosis.

Modern DM designs have demonstrated compelling findings across clinical and economic studies. The systematic review by Darrith et al [7] reported satisfactory outcomes with high survivorship for DM in primary and revision cases. Across a review of 46 articles, Donovan et al [8] determined that DM has contributed to a trend in reduced rates of dislocation following primary THA. The fiscal profile of DM has also garnered attention. Epinette et al [9] demonstrated a substantial cost savings with DM compared to traditional fixed bearing constructs in primary THA. These clinical and economic findings have provided short-term efficacy for DM.

There is momentum for DM to be used in a wider selection of patients, with some advocating for DM to be the routine primary total hip construct [10]. Historically, DM was indicated in cases with high risk for dislocation including older patient age, spinopelvic pathology, neuro compromise, and revision cases. Although early reports cautioned against routine DM utilization in young adult cases, the authors noted the potential for improved results with novel implant modifications [11]. Further investigation is needed to determine whether the routine use of DM in younger adults is validated by aggregate data.

Our objective was to review the literature for the clinical performance of DM THA in patients aged 55 years and younger. This evaluation comprised the reported clinical outcomes metrices, rates of revision, and implant survivorship.

Material and methods

Database query

A systematic review of the literature was performed according to the guidelines of Preferred Reporting in Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Institutional review board approval was not required for this work. PubMed and Google Scholar databases were queried on January 3, 2023, using the following terms: “dual mobility OR dual mobility” AND “young OR younger” with the additional search terms “under” and “years”. This process was performed by 2 authors independently and any questions for inclusion were jointly finalized.

Selection process

Inclusion into the review required clinical outcome reporting for a DM THA in ambulatory patients who were aged 55 years or younger. Articles were excluded for reporting on primary DM THA in patients older than 55 years, reporting on primary THA in patients younger than 55 years who were treated with a construct other than DM, reporting on DM in patients younger than 55 years who were not routinely ambulatory, and reporting for cases of revision THA. Cases for all indications were included. The reference list of articles which met the inclusion criteria was scanned for appropriate articles which may have not been included in the database query return.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias was appraised using the Cochrane risk of bias in nonrandomized studies of interventions [12]. The following domains were utilized: confounding, selection of participants, classification of interventions, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of reported results. For each study, a level of risk was individually evaluated for each domain, then the collective risk equated to the highest level of risk across the domains.

Quality assessment

The quality of the evidence was appraised using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation framework for each of the 3 generations of prosthesis [13]. The phase of investigation was identified then downgrading the quality of evidence was based on the following factors: limitations, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.

Statistical analysis

The pooled means for the outcome metrices Harris hip score and Postel-Merle d'Aubigné score were frequency weighted to represent the proportional contribution of each article. The difference between preoperative and postoperative frequency weighted means was compared using a 2-sample, 2-tailed Student T-test assuming unequal variances. Significance was set at P < .05. All other data were summed as means. Results were stratified according to generation of the DM prosthesis, as reported by each study.

Results

Search results

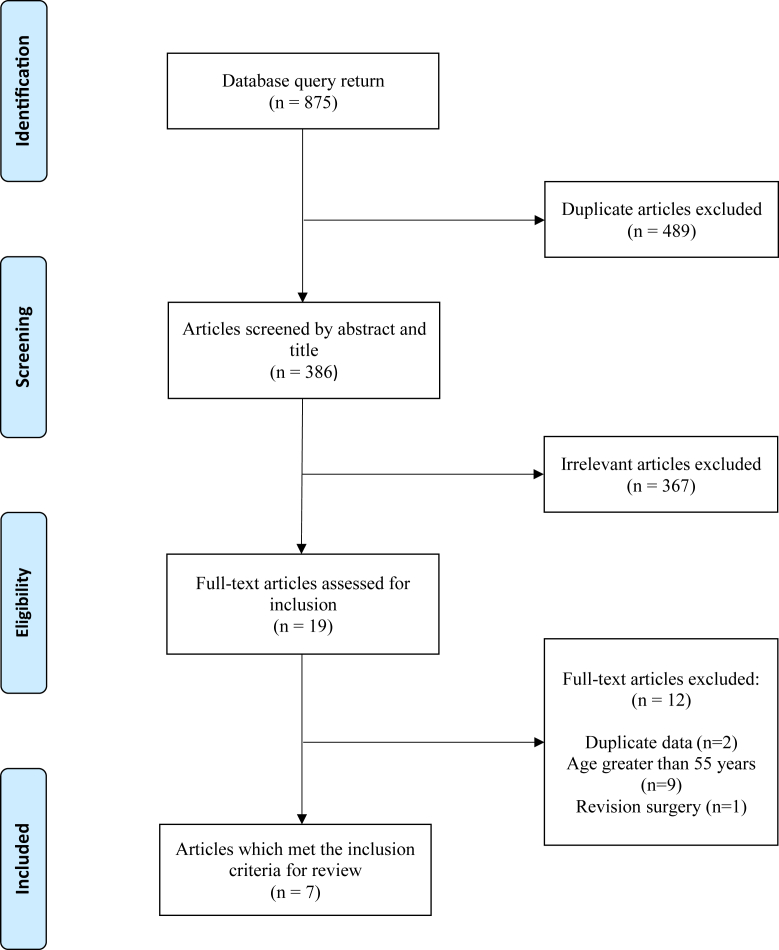

Following screening of 386 studies by title and abstract and 19 studies by full text, 7 articles met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). There were no disagreements among authors regarding application of the inclusion criteria to the search results.

Figure 1.

Flowchart depicting literature search and article selection process with exclusion criteria.

Bias and quality assessment

Six of the 7 included studies had at least 1 domain that was deemed to be at moderate risk of bias (Table 1). There were no domains that were deemed to be at a critical risk of bias.

Table 1.

Cochrane risk of bias ROBINS-I (risk of bias in nonrandomized studies of interventions) for included articles with green indicating low risk, yellow indicating moderate risks, and red indicating serious risk.

| Article | Confounding | Selection of participants | Classification of interventions | Deviation from intended interventions | Missing data | Measurement of outcomes | Selection of reported result | Overall bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viricel et al, 2022 [14] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Londhe et al, 2022 [15] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Rowan et al, 2017 [16] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Philippot et al, 2017 [17] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Epinette et al, 2016 [9] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Martz, 2017 [18] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Puch, 2017 [19] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Within the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation framework, all studies were classified as phase I investigations (Table 2). Each section of prosthesis generation was deemed to have serious limitations for publication bias which downgrades the level of evidence. The findings were unclear for inconsistency in first- and second-generation studies due to lack of corresponding evidence within these generations.

Table 2.

An adapted Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) summarization for primary dual-mobility total hip arthroplasty in patients aged 55 years and younger.

| Prosthesis generationa | Phase of investigation | Limitations | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First generation | Explanatory (phase I) | ✗ | Unclear | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Second generation | Explanatory (phase I) | ✗ | Unclear | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Third generation | Explanatory (phase I) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ |

As reported by the individual studies, ✓ - serious limitations, ✗- no serious limitations.

Study characteristics

Across a sample of 1048 cases, the weighted mean patient age was 45.3 years, 56% of patients were male, and the weighted mean term of follow-up was 87.7 months (Table 3). A metallic head was used in 56.2% of cases and 75.6% of cases used a third-generation DM prosthesis. The most common indications for DM were osteoarthritis (42.7%) and osteonecrosis (37.5%).

Table 3.

Case data for primary dual-mobility total hip arthroplasty in patients aged 55 years and younger.

| Study | N | Agea | Follow-upa | Generationa | Indications for DM THAa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-generation dual mobilityb | |||||

| Philippot et al, 2017 [17] | 137 | 41 | 262.8 | 1 | Dysplasia (27%) |

| Post-traumatic arthritis (24%) | |||||

| AVN (23%) | |||||

| Second-generation dual mobilityb | |||||

| Puch, 2017 [19] | 119 | 49.9 | 132 | 2 | OA (54.3%) |

| Dysplasia (25%) | |||||

| ON (12.9%) | |||||

| Third-generation dual mobilityb | |||||

| Epinette et al, 2016 [9] | 321 | 48.1 | 32.4 | 3 | OA (75.8%) |

| ON (17.2%) | |||||

| Dysplasia (5.9%) | |||||

| Martz, 2017 [18] | 40 | 44 | 129.8 | 3 | ON (100%) |

| Rowan et al, 2017 [16] | 136 | 48.5 | 38.4 | 3 | OA (78%) |

| Dysplasia (8.1%), | |||||

| ON (7.4%) | |||||

| Londhe et al, 2022 [15] | 204 | 42.5 | 67.5 | 3 | ON (100%) |

| Viricel et al, 2022 [14] | 91 | 43 | 117.6 | 3 | AVN (41%) |

| OA (32%) | |||||

| Dysplasia (10%) | |||||

| Totalc | 1048 | 45.7 (41-49) | 87.7 (38-263) | 75.6 (third gen) | OA (42.7%) |

| ON (37.5%) | |||||

| Dysplasia (10.1%) | |||||

AVN, avascular necrosis; OA, osteoarthritis; ON, osteonecrosis.

Indications for dual-mobility total hip arthroplasty.

Dual-mobility generation as reported by each study.

Age (years) and follow-up term (months) as frequency weighted means and (range), third generation reported as proportion.

Clinical outcomes

The pooled rate of revision was 9.5% across all included articles (Table 4). The most common indication for revision were femoral stem recall (27.6%), aseptic loosening of the acetabulum (24.1%), and intraprosthetic dislocation (IPD) (16%). The cases of femoral stem recall (Rejuvenate, Stryker) were reported by a single study [16], and the cases of IPD dislocation were reported by a single study which utilized a first-generation prosthesis [17]. When evaluating third-generation implants excluding cases of stem recall, the pooled rate of revision was 2.9% across 768 cases at a weighted mean follow-up of 57.7 months [14,15,18,20]. Within this group of third-generation implants, the most common indications for revision were adverse reaction to metal debris (36%, reported in 1 study), aseptic loosening of the acetabulum (14%, reported by 2 studies), and aseptic loosening of the femur (14%, reported by 2 studies).

Table 4.

Complications for primary dual-mobility total hip arthroplasty in patients aged 55 years and younger.

| Study | N | Dislocation | IPDa | Revision | Indications for revisiona |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-generation dual mobilityb | |||||

| Philippot et al, 2017 [17] | 137 | 0 | 10.9% (N = 15) | 32.1% | Aseptic loosening acetabulum (N = 19) eccentric polyethylene wear (N = 6) |

| Aseptic loosening femur (N = 2) | |||||

| Second-generation dual mobilityb | |||||

| Puch, 2017 [19] | 119 | 0 | 0 | 3.4% | Mechanical failure femur (N = 2) |

| Aseptic loosening acetabulum (N = 2) | |||||

| Third-generation dual mobilityb | |||||

| Rowan et al, 2017 [16] | 136 | 0 | 0 | 19.9% | Femoral stem recall (N = 24) |

| Aseptic loosening femur (N = 2) | |||||

| Epinette et al, 2016 [9] | 321 | 0 | 0 | 3.7% | Adverse reaction metal debris (N = 8) Impingement acetabulum (N = 2) |

| Martz, 2017 [18] | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0% | |

| Londhe et al, 2022 [15] | 204 | 0 | 0 | 0% | |

| Viricel et al, 2022 [14] | 91 | 0 | 0 | 7.7% | Aseptic loosening femur (N = 2) |

| Aseptic loosening acetabulum (N = 1) | |||||

| Septic loosening acetabulum (N = 1) | |||||

| Totalc | 792 | 0 | 0 | 6.3% | Femoral stem recall (52%) |

| Adversereaction metal debris (17%) | |||||

| Totald | 768 | 0 | 0 | 2.9% | Adverse reaction metal debris (36%) |

| Aseptic loosening acetabulum (14%) | |||||

| Totale | 1024 | 0% | 1.4% | 7.1% | Aseptic loosening acetabulum (31%) |

| IPD (21%) | |||||

| Adverse reaction metal debris (11%) | |||||

IPD, intraprosthetic dislocation, indications for revision include those with >1 case.

Dual-mobility generation as reported by each study.

Total for third-generation dual mobility, indications reported as proportion of revision cases.

Total for third-generation dual mobility without implant recall cases.

Total for first/second/third-generation dual mobility without implant recall cases.

The HHS was reported in all included articles and showed a significant improvement from 49.1 preoperatively to 93 postoperatively (P < .0001) (Table 5). These data include cases of stem recall from Rowan et al [16]. The Postel-Merle d'Aubigné score was reported in 37% of cases (387/1048) and significantly improved from a preoperative score of 10.5 to a postoperative score of 17.1 (P = .015).

Table 5.

Postoperative change in clinical outcome scores for dual-mobility total hip arthroplasty in patients aged 55 years and younger.

| Outcome | Cases (%) | Preoperativea | Postoperativea | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HHS | 1048 (100%) | 49.1 | 93.0 | <.0001 |

| PMA | 387 (37%) | 10.5 | 17.1 | .015 |

HHS, Harris hip score; PMA, Postel-Merle d'Aubigné score.

Data presented as frequency weighted mean.

Indicates statistical significance at P < .05.

Survival rate for all cause revision was reported by 6 articles representing 87% of cases (912/1048). A rate of 100% was reported by 2 articles [15,18], and the remaining survival rates were 96.1% [19], 97.5% [20], 92.2% [14], and 77% [17].

Discussion

Instability following THA has been notoriously problematic for surgeons. The advent of DM constructs provided a solution with demonstrable efficacy across primary and revision cases [7,21]. These results contributed to an expansion of indications including primary arthroplasty in younger adults. The projections for increased rates of THA in younger adults indicate the need for further understanding of the performance of DM in this population [4].

The current findings demonstrate satisfactory clinical results for DM in patients aged 55 years and younger. The pooled rate of revision was 9.5% across 1048 cases, and when removing cases for femoral stem recall, the pooled rate of revision of third-generation DM was 2.9% (N = 768) at a weighted mean follow-up of 57.7 months. The improvements in HHS and PMS scores were significant. There were zero dislocations reported and all reported IPDs were from a single series. At a mean follow-up of over 7 years, survivorship of over 95% for all-cause revision was demonstrated in 4 of the 6 articles that reported this metric. These findings suggest that DM primary THA in patients younger than 55 years provides short-term satisfactory clinical outcomes with a mitigated risk of dislocation.

Instability remains an unsolved problem in THA, with patient-related and surgery-related factors being contributory [22]. Older age, female gender, and neuromuscular and cognitive pathologies have been identified as risk factors for instability. Similarly, surgical approach, soft-tissue management, and implant characteristics are implicated [23]. Large head fixed-bearing arthroplasty or DM constructs are commonly utilized to improve stability. Although both options have demonstrated similar rates of revision for dislocation [24], DM may yield reduced rates of postoperative groin pain [25,26]. Novel DM designs provide contouring of the anterior acetabular component to replicate the native morphology of the psoas valley [27]. This design may reduce stress and impingement on the iliopsoas tendon [28].

Dislocation remains one of the most common indications for revision THA [29,30] with substantial economic burden to the health care system [31]. Recent analysis has demonstrated an increasing incidence of inpatient dislocation across the 2010s [32]. A PearlDiver database study identified younger age (<65 years) as a predictor for dislocation risk following primary THA [33]. Furthermore, the authors reported a higher odds ratio for dislocation in the subset younger than 55 years compared to younger than 65 years. This finding contrasts with prior reports which identify older age as a risk factor for dislocation [34]. We surmise that this discrepancy may be due to younger adults with active lifestyles opting for arthroplasty in order to maintain or regain a desired level of activity.

An important consideration in modular DM is the potential for metallic wear debris which can lead to adverse effects [35]. Modular DM utilizes a standard titanium acetabular shell which allows the surgeon to supplement fixation with screws, and in revision cases, allows liner exchange with shell retention. There is potential for micromotion between the shell and metal liner which may lead to fretting corrosion and subsequent metallosis. Furthermore, metal wear may occur due to the larger diameter head producing higher forces across the taper-trunnion interface [36]. Recent results on serum metal ion levels following modular DM may partially allay these concerns. Greenberg et al [37] reported no significant differences in cobalt and chromium levels between modular and nonmodular DM constructs at 1 year postoperatively. It is noteworthy that the rate of detection was greater in the modular group (39%) than in the nonmodular group (20%). In patients aged 65 years and younger, Nam et al [38] found that 4 DM patients had cobalt levels outside the reference range compared to 1 patient with a fixed bearing THA. Notably, all patients were asymptomatic with satisfactory clinical parameters. A recent systematic review on DM reported mildly elevated metal ion levels in 7.9% of cases and significantly elevated levels in 1.8% of cases with no correlation to clinical outcome scores [39]. Within the current work, only Epinette et al [20] reported complications related to metal wear. The authors identified the source of metal debris to be the failed modular neck-stem junction on the femur. In aggregate, although the current literature does not strongly indicate concern for metallic wear debris in DM cases, continued surveillance may be the prudent measure.

Contemporary DM constructs account for 3 articulations – the femoral head with the polyethylene liner, the polyethylene liner with the acetabular shell, and the polyethylene liner with the femoral neck. These provisions have contributed to improved outcomes compared to early designs. As summarized by Londhe et al [15], third-generation DM provided a material change on the acetabular cup for improved fixation and bone integration. First generations had an alumina coating, and third generations have plasma-sprayed titanium and hydroxyapatite bilayer coating [17]. Third generations have a denser gamma-irradiated polyethylene liner compared to first generation liners which were sterilized in air [17]. Additionally, improved geometry of third-generation polyethylene liners may lead to reduced risk of intraprosthetic dislocation, polyethylene liner wear, and aseptic loosening [40].

First-generation DM was reported by a single study with a revision rate of 32%, an IPD rate of 10.9%, and 77% all cause survivorship [17]. Third-generation implants comprised 75.5% of the reviewed sample. When excluding cases of femoral stem recall, the pooled rate of revision across novel designs was 2.9%. Within this subset of cases, the most frequent indications for revision were adverse metal debris (reported by one study due to modular neck-stem interface), and aseptic loosening of the femur (reported by 3 studies). These data suggest that innovation in DM design has yielded improved outcomes.

We acknowledge limitations within the current work. DM THA for all indications were included in the analysis. Additionally, all prosthesis types were included from first generation to third generation. We were unable to stratify results based on prosthesis design and modularity. The wide spectrum of case inclusion provides generalizable understanding for the performance of DM constructs in patients aged 55 years and younger. The reporting of outcomes metrices is variable. We were able to aggregate scores for 2 metrices across the included articles. The other reported metrices were not able to be aggregated due to insufficient sample. The longer existence of first-generation designs provides an inherently longer term of follow-up than that of newer designs. This disparity in follow-up may demonstrate survivorship differences at the current time but when temporally normalized, the survivorship may be similar. Finally, the findings should be evaluated within the context of the mean follow-up of 7 years.

Conclusions

The literature demonstrates satisfactory short-term outcomes with a mitigated risk of dislocation for DM used as primary THA in patients aged 55 years and younger. The current findings suggest that third-generation designs provide reduced rates of intraprosthetic dislocation and improved survivorship.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support and expertise of Mayra and Maveliza.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this work.

Conflicts of interest

Arturo Corces discloses consulting relationship with Exactech and royalties with Arthrex. All other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

For full disclosure statements refer to https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artd.2023.101241.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.De Martino I., D'Apolito R., Soranoglou V.G., Poultsides L.A., Sculco P.K., Sculco T.P. Dislocation following total hip arthroplasty using dual mobility acetabular components: a systematic review. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-b(ASuppl 1):18–24. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.99b1.Bjj-2016-0398.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heckmann N., Weitzman D.S., Jaffri H., Berry D.J., Springer B.D., Lieberman J.R. Trends in the use of dual mobility bearings in hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2020;102-b(7_Suppl_B):27–32. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.102b7.Bjj-2019-1669.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurtz S., Ong K., Lau E., Mowat F., Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:780–785. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz A.M., Farley K.X., Guild G.N., Bradbury T.L., Jr. Projections and epidemiology of revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States to 2030. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:S79–S85. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paderni S., Pari C., Raggini F., Busatto C., Delmastro E., Belluati A. Third generation dual mobility cups: could be the future in total hip arthroplasty? A five-year experience with dualis. Acta Biomed. 2022;92 doi: 10.23750/abm.v92iS3.12541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bistolfi A., Giustra F., Bosco F., Sabatini L., Aprato A., Bracco P., et al. Ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) for hip and knee arthroplasty: the present and the future. J Orthop. 2021;25:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2021.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darrith B., Courtney P.M., Della Valle C.J. Outcomes of dual mobility components in total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review of the literature. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-b:11–19. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.100b1.Bjj-2017-0462.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donovan R.L., Johnson H., Fernando S., Foxall-Smith M., Whitehouse M.R., Blom A.W., et al. The incidence and temporal trends of dislocation after the use of constrained acetabular components and dual mobility implants in primary total hip replacements: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. J Arthroplasty. 2022;37:993–1001.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2022.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epinette J.A., Lafuma A., Robert J., Doz M. Cost-effectiveness model comparing dual-mobility to fixed-bearing designs for total hip replacement in France. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blakeney W.G., Epinette J.A., Vendittoli P.A. Dual mobility total hip arthroplasty: should everyone get one? EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4:541–547. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vielpeau C., Lebel B., Ardouin L., Burdin G., Lautridou C. The dual mobility socket concept: experience with 668 cases. Int Orthop. 2011;35:225–230. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1156-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sterne J.A., Hernán M.A., Reeves B.C., Savović J., Berkman N.D., Viswanathan M., et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huguet A., Hayden J.A., Stinson J., McGrath P.J., Chambers C.T., Tougas M.E., et al. Judging the quality of evidence in reviews of prognostic factor research: adapting the GRADE framework. Syst Rev. 2013;2:71. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viricel C., Boyer B., Philippot R., Farizon F., Neri T. Survival and complications of total hip arthroplasty using third-generation dual-mobility cups with non-cross-linked polyethylene liners in patients younger than 55 years. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2022;108 doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2022.103208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Londhe S.B., Khot R., Shah R.V., Desouza C. An early experience of the use of dual mobility cup uncemented total hip arhroplasty in young patients with avascular necrosis of the femoral head. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2022;33 doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2022.101995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rowan F.E., Salvatore A.J., Lange J.K., Westrich G.H. Dual-mobility vs fixed-bearing total hip arthroplasty in patients under 55 years of age: a single-institution, matched-cohort analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:3076–3081. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philippot R., Neri T., Boyer B., Viard B., Farizon F. Bousquet dual mobility socket for patient under fifty years old. More than twenty year follow-up of one hundred and thirty one hips. Int Orthop. 2017;41:589–594. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3385-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martz P., Maczynski A., Elsair S., Labattut L., Viard B., Baulot E. Total hip arthroplasty with dual mobility cup in osteonecrosis of the femoral head in young patients: over ten years of follow-up. Int Orthop. 2017;41:605–610. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3344-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puch J.M., Derhi G., Descamps L., Verdier R., Caton J.H. Dual-mobility cup in total hip arthroplasty in patients less than fifty five years and over ten years of follow-up: a prospective and comparative series. Int Orthop. 2017;41:475–480. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3325-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epinette J.A., Harwin S.F., Rowan F.E., Tracol P., Mont M.A., Chughtai M., et al. Early experience with dual mobility acetabular systems featuring highly cross-linked polyethylene liners for primary hip arthroplasty in patients under fifty five years of age: an international multi-centre preliminary study. Int Orthop. 2017;41:543–550. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Batailler C., Fary C., Verdier R., Aslanian T., Caton J., Lustig S. The evolution of outcomes and indications for the dual-mobility cup: a systematic review. Int Orthop. 2017;41:645–659. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3377-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Upfill-Brown A., Hsiue P.P., Sekimura T., Patel J.N., Adamson M., Stavrakis A.I. Instability is the most common indication for revision hip arthroplasty in the United States: national trends from 2012 to 2018. Arthroplast Today. 2021;11:88–101. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2021.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Werner B.C., Brown T.E. Instability after total hip arthroplasty. World J Orthop. 2012;3:122–130. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v3.i8.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoskins W., Bingham R., Dyer C., Rainbird S., Graves S.E. A comparison of revision rates for dislocation and aseptic causes between dual mobility and large femoral head bearings in primary total hip arthroplasty with subanalysis by acetabular component size: an analysis of 106,163 primary total hip arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty. 2021;36:3233–3240. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2021.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenartowicz K.A., Wyles C.C., Carlson S.W., Sierra R.J., Trousdale R.T. Prevalence of groin pain after primary dual-mobility total hip arthroplasty. Hip Int. 2023;33:214–220. doi: 10.1177/11207000211039168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore M.R., Lygrisse K.A., Singh V., Arraut J., Chen E.A., Schwarzkopf R., et al. The effect of femoral head size on groin pain in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2022;37:S577–S581. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2022.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vandenbussche E., Saffarini M., Delogé N., Moctezuma J.L., Nogler M. Hemispheric cups do not reproduce acetabular rim morphology. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:327–332. doi: 10.1080/174536707100013870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zumbrunn T., Patel R., Duffy M.P., Rubash H.E., Malchau H., Freiberg A.A., et al. Cadaver-specific models for finite-element analysis of iliopsoas impingement in dual-mobility hip implants. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:3574–3580. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bozic K.J., Kamath A.F., Ong K., Lau E., Kurtz S., Chan V., et al. Comparative epidemiology of revision arthroplasty: failed THA poses greater clinical and economic burdens than failed TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:2131–2138. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-4078-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gwam C.U., Mistry J.B., Mohamed N.S., Thomas M., Bigart K.C., Mont M.A., et al. Current Epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States: National Inpatient Sample 2009 to 2013. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:2088–2092. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdel M.P., Cross M.B., Yasen A.T., Haddad F.S. The functional and financial impact of isolated and recurrent dislocation after total hip arthroplasty. Bone Joint Lett J. 2015;97-b:1046–1049. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.97b8.34952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohamed N.S., Castrodad I.M.D., Etcheson J.I., Sodhi N., Remily E.A., Wilkie W.A., et al. Inpatient dislocation after primary total hip arthroplasty: incidence and associated patient and hospital factors. Hip Int. 2022;32:152–159. doi: 10.1177/1120700020940968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gillinov S.M., Joo P.Y., Zhu J.R., Moran J., Rubin L.E., Grauer J.N. Incidence, timing, and predictors of hip dislocation after primary total hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2022;30:1047–1053. doi: 10.5435/jaaos-d-22-00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kunutsor S.K., Barrett M.C., Beswick A.D., Judge A., Blom A.W., Wylde V., et al. Risk factors for dislocation after primary total hip replacement: meta-analysis of 125 studies involving approximately five million hip replacements. Lancet Rheumatol. 2019;1:e111–e121. doi: 10.1016/s2665-9913(19)30045-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amanatullah D.F., Sucher M.G., Bonadurer G.F., 3rd, Pereira G.C., Taunton M.J. Metal in total hip arthroplasty: wear particles, biology, and diagnosis. Orthopedics. 2016;39:371–379. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20160719-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang S., Xie F., Cui W., Zhang Y., Jin Z. A review of the clinical and engineering performance of dual-mobility cups for total hip arthroplasty. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13:9383–9394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenberg A., Nocon A., De Martino I., Mayman D.J., Sculco T.P., Sculco P.K. Serum metal ions in contemporary monoblock and modular dual mobility articulations. Arthroplast Today. 2021;12:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2021.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nam D., Salih R., Brown K.M., Nunley R.M., Barrack R.L. Metal ion levels in young, active patients receiving a modular, dual mobility total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:1581–1585. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.French J.M.R., Bramley P., Scattergood S., Sandiford N.A. Adverse reaction to metal debris due to fretting corrosion between the acetabular components of modular dual-mobility constructs in total hip replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EFORT Open Rev. 2021;6:343–353. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.6.200146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neri T., Boyer B., Geringer J., Di Iorio A., Caton J.H., PhiIippot R., et al. Intraprosthetic dislocation of dual mobility total hip arthroplasty: still occurring? Int Orthop. 2019;43:1097–1105. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-4054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.