Abstract

Background

Certification of obesity medicine for physicians in the United States occurs mainly via the American Board of Obesity Medicine (ABOM). Obesity medicine is not recognized as a subspecialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) or the American Osteopathic Association (AOA). This review examines the value of specialization, status of current ABOM Diplomates, governing bodies involved in ABMS/AOA Board Certification, and the advantages and disadvantages of an ABMS/AOA recognized obesity medicine subspecialty.

Methods

Data for this review were derived from PubMed and appliable websites. Content was driven by the expertise, insights, and perspectives of the authors.

Results

The existing ABOM obesity medicine certification process has resulted in a dramatic increase in the number of Obesity Medicine Diplomates. If ABMS/AOA were to recognize obesity medicine as a subspecialty under an existing ABMS Member Board, then Obesity Medicine would achieve a status like other ABMS recognized subspecialities. However, the transition of ABOM Diplomates to ABMS recognized subspecialists may affect the kinds and the number of physicians having an acknowledged focus on obesity medicine care. Among transition issues to consider include: (1) How many ABMS Member Boards would oversee Obesity Medicine as a subspecialty and which physicians would be eligible? (2) Would current ABOM Diplomates be required to complete an Obesity Medicine Fellowship? If not, then what would be the process for a current ABOM Diplomate to transition to an ABMS-recognized Obesity Medicine subspecialist (i.e., “grandfathering criteria”)? and (3) According to the ABMS, do enough Obesity Medicine Fellowship programs exist to recognize Obesity Medicine as a subspecialty?

Conclusions

Decisions regarding a transition to an ABMS recognized Obesity Medicine Subspecialty versus retention of the current ABOM Diplomate Certification should consider which best facilitates medical access and care to patients with obesity, and which best helps obesity medicine clinicians be recognized for their expertise.

Keywords: Obesity, Certification

1. Introduction

This review focuses on obesity medicine certification processes in the United States. While other obesity certification processes exist (e.g., Commission on Dietetic Registration and World Obesity Federation), it is the American Board of Obesity Medicine (ABOM) that currently certifies physician Obesity Medicine Diplomates in the United States (https://www.abom.org/) [1]. The ABOM is an independent entity that, according to its website, was established in 2011 to:

“Serve the public and the field of obesity medicine by maintaining standards for assessment and credentialing physicians. Certification as an ABOM diplomate signifies specialized knowledge in the practice of obesity medicine and distinguishes a physician as having achieved competency in obesity care delivery. Physicians who complete the ABOM certification process in obesity medicine are designated Diplomates of the American Board of Obesity Medicine.” (https://www.abom.org/history/)

While the ABOM certifies physicians as “Diplomates of the American Board of Obesity Medicine,” Obesity Medicine is not recognized as a subspecialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS). Thus, the ABOM website further states:

“Recognition of obesity medicine as a subspecialty certification by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) remains the long-term goal for the American Board of Obesity Medicine. While there is no specific timetable for achieving this, all of the requirements for certification that ABOM has in place are aligned with the goal of ABMS recognition. And the growing number of ABOM diplomates is an important factor that clearly illustrates the demand for a certification that allows physicians to demonstrate their competency in obesity medicine. In addition, a separate organization, the Obesity Medicine Fellowship Council, is working toward increasing the number of obesity medicine fellowship opportunities, which is another important benchmark any emerging field needs to meet in order to gain ABMS recognition.” (https://www.abom.org/history/)

In March of 2023, Obesity Pillars (journal of the Obesity Medicine Association) published an article entitled: “Future of Obesity Medicine: Fearless 5-year predictions for 2028.” Included among the more common topics spontaneously chosen by obesity medicine leaders in their predictions was the potential status of future board certification of obesity medicine. For those who expressed a prediction regarding this topic, wide variance existed in whether obesity medicine would become an ABMS recognized subspecialty by 2028 [2]. This reflects the uncertainty of this topic among obesity medicine clinicians. It is the purpose of this review to examine the factors relative to obesity medicine certification. Table 1 lists Ten Things to Know about Obesity Medicine Certification.

Table 1.

Ten things to know about Obesity Medicine Certification.

| Ten things to know about Obesity Medicine Certification | References |

|---|---|

|

https://www.abom.org/ |

|

https://www.abom.org/stats-data-2/ |

|

https://www.abom.org/ |

|

https://omfellowship.org/directory-of-programs/ |

|

https://www.abms.org/) |

|

[[3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]] |

|

[11] |

|

https://www.abms.org/ |

|

https://www.abms.org/ |

|

https://www.abms.org/ |

| https://www.aaem.org/UserFiles/file/president_0508.pdf#:∼:text=Similar%20to%20other%20medical%20specialties%20in%20their%20early,by%20residency%20training%20or%20the%20initial%20practice%20track | |

| https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/rccm.2509005#:∼:text=This%20clinical%20practice%20experience%20pathway%20consists%20of%20a,in%20sleep%20medicine%20during%20the%20prior%205%20years. |

2. Value of specialty and subspecialty certification

Specialization and sub-specialization of medical practices have advantages to patients and clinicians [12]. Being established as an Obesity Medicine Diplomate allows physicians to better focus their clinical practice when compared to clinicians engaged in more general patient care. Obesity is a complex disease, which like other complex diseases, might best be managed by an Obesity Medicine Diplomate trained in the management of the complex complications of obesity.

2.1. Benefits to patients

Certification in a medical subspecialty involves additional training and additional assessment in a field of medicine targeted to specific organ systems, diseases, or patient populations. Medical subspecialists can improve the quality of patient care by.

-

•

Applying enhanced knowledge in the evaluation (e.g., diagnosis) and evidenced-based treatment (e.g., nutrition, physical activity, medications, surgery) of a specific disease, such as the disease of obesity [[3], [4], [5]].

-

•

Providing patient-centered care in an environment that is more inviting for patients having a specific disease (e.g., obesity), with more targeted workplace flow, more applicable equipment, decreased bias and stigma, and more highly trained personnel than might be found in a more general medical practice [6].

-

•

Administering more cost-effective care through increased diagnostic accuracy and increased clinical treatment experience in managing challenging patient presentations – with cost effectiveness inclusive of non-procedural recommendations [7].

2.2. Benefits to clinicians

Certification in a medical specialty or subspecialty may provide benefits to clinicians via.

-

•

Enhancing professional development through the attainment of specialized skills and expertise, allowing for more focused attention to the latest research and advancements in a specific medical field [8], and potentially elevating the reputational standing of the clinician.

-

•

Providing clinicians greater medical practice satisfaction from engagement in medical activities that best suits the clinician's passion, best achieves the clinician's “sense of meaning” [9], best allows for the highest level of patient care, and best fulfills the clinician's academic interest [8].

-

•

Allowing for a more focused concentration on a single area of medicine may allow for a more organized and cohesive positioning and translation of physician priorities during patient interactions. This may further physician satisfaction given that less chaos, more communication, and closer value alignment directly correlate to physician workplace enjoyment [10].

-

•

Potentially facilitating increased referrals. It is unclear that certification in specialties or subspecialties results in increased income per patient. In general, enhanced financial returns for the physician are most evident in certification of subspecialities that are procedure oriented (e.g., gastroenterology, cardiology, pulmonary medicine). Beyond increased referrals, it is unclear that physicians with additional training in largely non-procedural subspecialities (e.g., rheumatology, endocrinology, and perhaps obesity medicine) have a meaningful financial return on the additional amount of time and monetary training investment in achieving a subspecialty [11]. This is especially so if the applicable billing codes do not substantially differ from primary care clinicians. For example, some reports suggest dermatologists (i.e., many who perform procedures) receive among the top mean physician specialty salaries, while pediatricians may receive among the lowest of specialty salaries, with a mean income ∼2/3 that of dermatologists (https://www.merritthawkins.com/news-and-insights/blog/healthcare-news-and-trends/physician-starting-salaries-by-specialty-2022-vs-2021/). This again suggests that the financial return on attaining a specialty or subspecialty depends on the specific specialty or subspecialty, and the degree the specialty or subspecialty allows for unique billable procedures.

3. Status of Obesity Medicine Diplomates

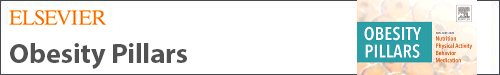

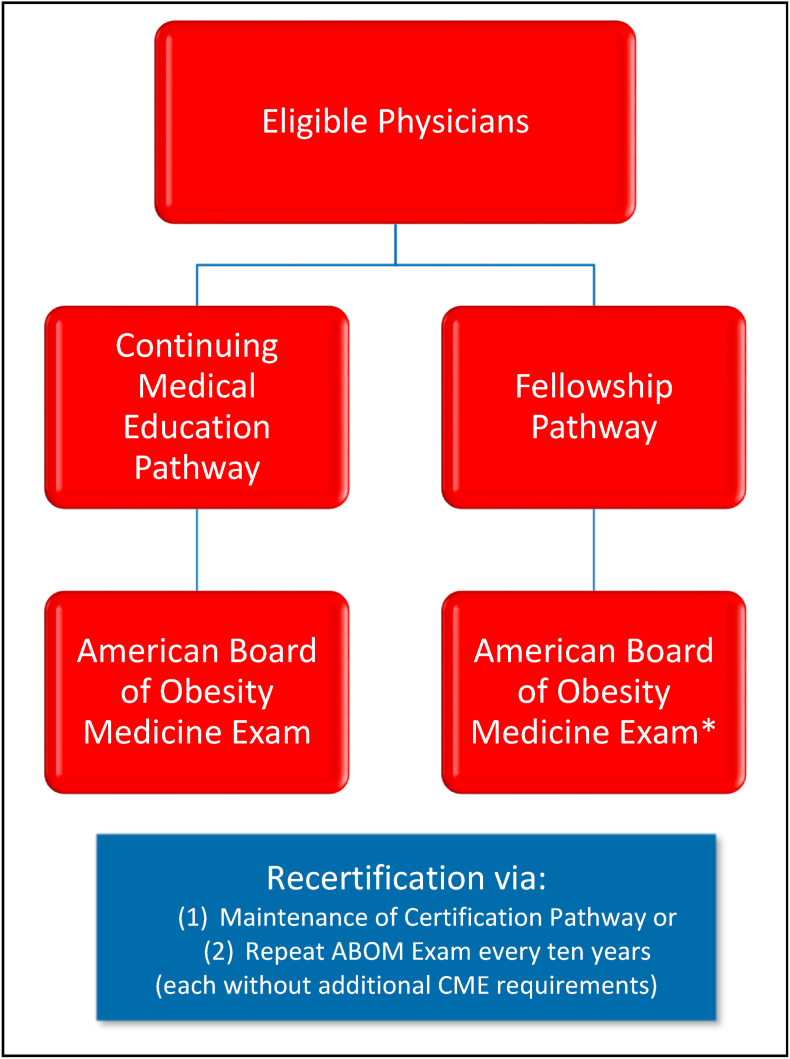

Since the establishment of the ABOM, the number of Obesity Medicine Diplomates has consistently and dramatically increased. (Fig. 1). (https://www.abom.org/stats-data-2/) At the time of this writing, over 97% of ABOM Diplomates are certified via a continuing medical education (CME) and subsequent exam pathway (i.e., 5076 Obesity Medicine Diplomates), while 189 Obesity Medicine Diplomates have certified by completing an on-site clinical Fellowship, and then exam pathway (See Fig. 2). In 2022, nineteen physicians graduated from Obesity Medicine Fellowship programs. Overall, as of the Spring 2023, a total of eighty-eight ABOM Diplomates have completed an OMFC-recognized Obesity Medicine Fellowship (internal data).

Fig. 1.

Cumulative number of American Board of Obesity Medicine Diplomates since year 2013 (https://www.abom.org/stats-data-2/).

Fig. 2.

American Board of Obesity Medicine (ABOM) Diplomate Pathways. Achievement of the status of an ABOM Diplomate can occur via two pathways: (1) Continuing Medical Education (CME) pathway plus exam, or Fellowship plus exam pathway.

The Obesity Medicine Fellowship Council (OMFC; see more detailed description below) aims to grow subspecialty training opportunities in obesity medicine. As of March 2023, twenty-four Obesity Medicine Fellowship programs exist (www.omfellowship.org), up from five in 2018 when the OMFC was established. If the field of obesity medicine were to seek sponsorship from ABIM to be recognized by the ABMS, then it is estimated that at least 60–70 Obesity Medicine Fellowship programs would need to be established with all the positions filled each year.

∗ Prior to start of August 2023, physicians who completed acceptable Fellowship training on the topic of obesity or obesity-related conditions, could become ABOM Diplomates if they passed the ABOM exam (https://www.abom.org/eligibility-fellowship-pathway). However, after August 2023, for those who choose the Obesity Fellowship plus exam pathway, only applicants who complete a dedicated 1-year Obesity Medicine Fellowship recognized by the Obesity Medicine Fellowship Council (OMFC) will be eligible to take the ABOM exam without need to meet CME criteria (i.e., those completing other fellowships such as Endocrinology, Gastroenterology, etc. are no longer eligible). Those completing Fellowships other than a dedicated Obesity Medicine Fellowship are still eligible to apply for ABOM Diplomate Certification via the CME pathway (See Fig. 2).

4. Applicable governing bodies

For obesity medicine to be an ABMS/AOA recognized subspecialty, it will require representatives and/or leaders in the field of obesity medicine to engage and coordinate the integrative efforts of various applicable organizations, which include.

4.1. American board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) (https://www.abms.org/)

The ABMS is a nonprofit organization that represents 24 independent certifying boards and the vehicle through which standards and policies are established relative to board certifications and maintenance of certification (MOC). If Obesity Medicine was to be recognized by the ABMS as a subspecialty, then it is probable that the current ABOM would be folded into an ABMS member board, or the current ABOM would cease to exist. In other words, achieving recognition of Obesity Medicine as an official subspecialty by ABMS would require one or more ABMS Member Boards to assume the ultimate oversight of the ABOM standards that include qualifications (e.g., credentialing), training (e.g., Fellowship) and testing (e.g., exam and/or maintenance of certification).

Currently, the ABMS represents 24 Boards that certify physicians in 40 specialties and 88 subspecialty areas (https://www.abms.org/). These Boards were founded by their respective specialties to oversee the assessment and certification of physicians, based upon specific educational, training, and professional requirements. Thus, in addition to establishing initial and ongoing certification standards, and administering appropriate exams, another responsibility of ABMS Member Boards is to create and oversee Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) fellowship programs (https://www.acgme.org/what-we-do/overview/). Obesity Medicine Fellowship programs currently recognized by the OMFC are not under the oversight and regulation of the ACGME. If ABMS were to recognize Obesity Medicine as a subspecialty, then existing Obesity Medicine Fellowship programs would need to ensure that that ACGME standards were met. This may mean that, as with other fellowship programs, Obesity Medicine Fellowship Programs could potentially need to modify their curriculum, financial models, protected faculty time, and program evaluation processes, among other requirements.

Examples of ABMS Member Boards potentially most applicable to a future ABMS recognized Obesity Medicine subspecialty might be the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM), American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), and American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ABOG). (https://www.abms.org/member-boards/). In addition to these specialties, other examples of the 24 ABMS Member Boards who could conceivably oversee Obesity Medicine as a subspecialty might also include the American Board of Emergency Medicine, American Board of Preventive Medicine, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, and American Board of Surgery (https://www.abms.org/member-boards/).

The ABIM is the ABMS Member Board that manages internal medicine medical subspecialty board certifications and maintenance of certification (https://www.abim.org/). The ABIM certifies approximately one of every four physicians in the United States, and is responsible for certification of the subspecialities of Adolescent Medicine, Adult Congenital Heart Disease, Advanced Heart Failure & Transplant Cardiology, Cardiovascular Disease, Clinical Cardiac Electrophysiology, Critical Care Medicine, Endocrinology, Diabetes, & Metabolism, Gastroenterology, Geriatric Medicine, Hematology, Hospice & Palliative Medicine, Infectious Disease, Interventional Cardiology, Medical Oncology, Nephrology, Neurocritical Care, Pulmonary Disease, Rheumatology, Sleep Medicine, and Transplant Hepatology (https://www.abim.org/about/mission/).

Another illustrative example of an ABMS Member Board potentially applicable to an Obesity Medicine subspecialty would be the ABFM, which is responsible for certification of the subspecialties of Adolescent Medicine, Geriatric Medicine, Hospice and Palliative Medicine, Pain Medicine, Sleep Medicine, and Sports Medicine (https://www.theabfm.org/added-qualifications/adolescent-medicine). Subspecialities of the ABMS Member, ABP, include cross over with ABIM and ABFM in Adolescent Medicine, Hospice and Palliative Medicine, Sleep Medicine, and Sports Medicine. The ABOG has subspecialties, but none that cross over with ABIM, ABFM, or ABP (www.abms.org/member-boards/specialty-subspecialty-certificates/).

In summary, some ABMS recognized subspecialties exist only under a single ABMS Member Board, while others are shared between ABMS Member Boards. For example, Sports Medicine is co-sponsored under the ABIM, the ABFM, the ABP, the American board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM), and the American board of Physical Medicine and Rehab (ABPMR). (www.abms.org/member-boards/). Precedent shared subspecialities across various ABMS Member Boards might allow Internal Medicine physicians, Family Medicine physicians and Pediatricians (and potentially other specialties), the opportunity to be ABMS recognized as obesity medicine specialists. This potential for shared sub-specialty in Obesity Medicine by multiple ABMS Member Boards (e.g., as with sports medicine or adolescent medicine) might allow for more providers to become ABMS recognized Obesity Medicine subspecialists, thus improving the growth in the obesity field and potentially increasing access to obesity care. Shared sub-specialty in Obesity Medicine by multiple ABMS Member Boards may also enhance the number of current ABOM diplomates who could potentially qualify as a subspecialist in Obesity Medicine, as recognized by the ABMS.

4.2. American osteopathic association (AOA)

The AOA represents more than 178,000 osteopathic physicians and medical students across the U.S.

4.2.1. According to its website (https://osteopathic.org/about/)

“Osteopathic physicians, or DOs, believe there's more to good health than the absence of pain or disease. Their whole-person approach to medicine focuses on prevention, helping promote the body's natural tendency toward health and self-healing. Osteopathic medicine is one of the fastest-growing health care professions in the country. Approximately one in four medical students attends a college of osteopathic medicine. As the primary certifying body for DOs and the accrediting agency for all osteopathic medical schools, the AOA works to accentuate the distinctiveness of osteopathic principles and the diversity of the profession. In addition to promoting public health and encouraging scientific research, the AOA advocates at the state and federal levels on issues that affect DOs, osteopathic medical students, and patients.”

Regarding specialties, according to the AOA website (https://certification.osteopathic.org/specialties-and-subspecialties/) :

“The American Osteopathic Association’s Department of Certifying Board Services administers the processes of board certification and osteopathic continuous certification for 16 specialty certifying boards, offering certifications in 27 primary specialties and 48 subspecialties.”

4.3. Obesity Medicine Fellowship Council (OMFC) (https://omfellowship.org/)

Currently, the OMFC identifies 24 Obesity Medicine Fellowship Programs of which at least two are Specialized Obesity Programs (https://omfellowship.org/directory-of-programs/). These include fellowship institutions in the US and Canada who applied to be a part of the council. As the field expands, new fellowships are encouraged to join the council; thus, additional fellowships may be forthcoming. (https://omfellowship.org/directory-of-programs/)

4.3.1. According to its website

“The Obesity Medicine Fellowship Council (OMFC) was created with a mission: To enhance access to effective obesity care through advanced clinical training of specialized obesity medicine physicians. Our goals are: To support Obesity Medicine Fellowship training programs and their primary educational mission, promote an adequate supply of effective specialty training opportunities, and increase the number of subspecialty fellowship-trained obesity medicine physicians. The OMFC is dedicated to providing the most up-to-date information regarding Obesity Medicine Fellowship training, as well as other resources for those interested in learning more about careers in obesity medicine. As the field of obesity medicine grows and more fellowships are developed, we believe there should be standardization in what constitutes an Obesity Medicine Fellowship program. The OMFC aims to provide guidance on best practices so that all fellowship programs are sustainable, provide comprehensive training, and prepare the next generation of Obesity Medicine Specialists to combat the obesity epidemic. With the establishment of more fellowship programs, Obesity Medicine can become eligible to be recognized as an American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) subspecialty.”

4.4. Centers for medicare and medicaid services (CMS) (https://www.cms.gov/)

CMS is a federal agency within the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) that administers the Medicare healthcare program, and in partnership with states, the Medicaid healthcare program. Other functions of CMS include the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act issues (HIPAA), and the “Open Payment” system.

CMS establishes “Provider Taxonomy,” recognizing a specialty or subspecialty, irrespective of who granted certification. A taxonomy code is a unique 10-character code that designates a specialty classification, and can be used for applying for a National Provider Identifier or NPI (https://www.cms.gov/medicare/provider-enrollment-and-certification/find-your-taxonomy-code#:%7E:text=What%20is%20a%20taxonomy%20code). The obesity medicine taxonomy code sets differ, depending on whether it applies to Family Medicine, Internal Medicine, Obstetrics & Gynecology, Pediatrics, Preventive Medicine, or Psychiatry & Neurology (https://taxonomy.nucc.org/?searchTerm=obesity+medicine).

4.5. Non-Physician Obesity Medicine Certificate [13]

ABOM certification (i.e., Obesity Medicine Diplomates) is only available for physicians. Currently required credentials for ABOM certification eligibility include: (a) Proof of an active medical license in the U.S. or Canada; (b) Proof of completion of a residency in the U.S. or Canada; and (c) Active board certification in an American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) Member Board or American Osteopathic Association (AOA) (https://www.abom.org/eligibility-/). Clinicians such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and doctors of philosophy (e.g., PhD clinicians may include those with expertise in psychology, nursing, nutrition, physical exercise, pharmacy, and public health) are not eligible for ABMS, AOA, or ABOM certification. However, such individuals represent a substantial proportion of obesity medical society members and their leadership [13] (https://www.obesity.org/the-obesity-society-governing-board/).

That said, some certifications are available for non-physicians. For example, in 2017, the Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) established the NP/PA Certificate of Advanced Education in Obesity Medicine (https://obesitymedicine.org/cme/np-pa-certificate-obesity-medicine/), which recognizes NP/PAs knowledge and contributions to obesity management. NP/PAs who earn this certificate are required to receive the same number and type of Continuing Education/Continuing Medical Education credits as the physicians who take the American Board of Obesity Medicine (ABOM) exam. NP/PAs do not need to be OMA members to earn the certificate. As of March 1, 2023, 477 NP/PAs have earned the certificate, 371 (77%) being NPs and 106 (22%) being PAs.

Other non-physician US certificates include.

-

•

The American Academy of Physician Associates Obesity Management in Primary Care Training and Certificate Program (https://www.aapa.org/cme-central/primary-care-obesity-management-certificate-program/)

-

•

The American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Certified Bariatric Nurse (CBN) (https://asmbs.org/integrated-health/cbn-certification)

-

•

Interdisciplinary Board Certified Specialist in Obesity and Weight Management (https://www.cdrnet.org/interdisciplinary)

5. Other potential ABMS-related designations

Beyond ABMS certifying Obesity Medicine as a subspecialty, other options exist for ABMS recognition. They include.

5.1. Focused Practice/certificates of added qualification (CAQs) (https://www.abms.org/focused-practice-designation/)

The Focused Practice designation was approved by ABMS in 2017, for the purpose of recognizing physicians and specialists (“Diplomates”) who focus their practice within a specific area of a specialty and/or subspecialty. Once a physician obtains initial certification in an applicable specialty, a “Focused Practice Designation” enables the ABMS Member Boards to set eligibility standards and maintenance of certification for the Focused Practice designation. Requirements may include (1) Current and continuous ABMS Member certification; (2) verification of a specified number of years of unsupervised experience in the applicable field of focus; meeting a specified number of patient encounters; (4) completion of other designated activities; (5) submission of an online application with payment of an appropriate fee; (6) achievement of a passing score on the Designation of Focused Practice in the applicable field of focus (https://www.theabfm.org/added-qualifications/hospital-medicine#:%7E:text=How%20do%20I%20Obtain%20My).

A “Focused Practice Designation” differs from subspecialty certification in that an ABMS subspecialty board certification requires an ACGME-accredited training program of at least one (1) year in duration — in addition to the training required for general certification. In contrast, a “Focused Practice Designation” recognizes specific areas of practice in which Diplomates progress through their professional careers or emerge as medicine changes due to advances in medical knowledge. “Focused Practice Designations” are medical practice areas more limited in scope than those covered by subspecialty designation (https://www.abms.org/focused-practice-designation/). If Obesity Medicine was to become a “Focused Practice Designation” then it presumably would not require completion of a Fellowship to be recognized by the ABMS (albeit not as a board-certified subspecialty). Illustrative ABMS-approved “Focused Practice Designations” and their affiliated ABMS Member Board can be found at https://www.abms.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/abms-focused-practice-designations-table-202108.pdf, with current areas of “Focused Practice Designation” including.

-

•

Advanced Emergency Medicine Ultrasonography

-

•

Central Nervous System Endovascular Surgery

-

•

Clinical Chemistry

-

•

Clinical Microbiology

-

•

Hospital Medicine

-

•

Metabolic Bariatric Surgery

-

•

Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery

-

•

Neurological Critical Care

-

•

Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology

-

•

Pediatric Neurological Surgery

An interesting aspect of a “Focused Practice Designation” is that the same “Focus Practice Designation” can be overseen by different ABMS members. For example, Hospital Medicine is overseen by the ABMS member boards of Family Medicine and Internal Medicine. One might imagine that if obesity medicine were to become a “Focused Practice Designation,” then the applicable ABMS Board members might include the American Board of Internal Medicine, the American Board of Family Practice, the American Board of Pediatrics, and perhaps others (https://www.abms.org/member-boards/). This would allow internal medicine physicians, family medicine physicians, pediatric physicians, and perhaps other physicians the opportunity to be recognized as clinicians who have achieved a “Focus Practice Designation” in obesity medicine.

A challenge to the potential “Focused Practice Designation” for obesity medicine is that the primary assumption of the “Focused Practice” model is that applicable physicians have already learned what is needed in the existing residency and/or fellowship curriculum, and then chooses to apply that learning to a specific population or scope of practice. Regarding obesity, an overriding premise is that physicians are not sufficiently trained in obesity medicine and therefore do need additional training. Thus, obesity medicine may not fit this “Focused Practice” model currently. However, this may change as education regarding obesity management becomes a greater emphasis during medical training.

5.2. Certificates of added qualifications (CAQs)

CAQ's are like the Focused Practice Designation, but involving different clinical subspecialties. CAQs provide special designations based upon (1) maintenance of ABMS Member Certification, (2) eligibility via acceptance of an application; (3) receipt of appropriate fees; and (4) achievement of a passing score on the applicable exam. For example, the American Board of Family Medicine offers CAQs for the following (https://www.theabfm.org/added-qualifications).

-

•

Adolescent Medicine

-

•

Geriatric Medicine

-

•

Hospice and Palliative Medicine

-

•

Pain Medicine

-

•

Sleep Medicine

-

•

Sports Medicine

6. Challenges of an ABMS obesity medicine subspecialty

Some of the advantages of Obesity Medicine as a subspecialty were discussed in section 2.0. Another potential advantage is better ABMS recognition of obesity as a disease. In 2021, a review of ABMS Member Board outlines of exam content indicated the absence of mention of obesity. This suggested to the authors that ABMS examinations would benefit from “increased coverage of the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of obesity across all board examinations” [14]. Thus, having ABMS oversight of Obesity Medicine as a subspecialty might better position obesity as integrative to learnings and prioritization across other ABMS designated subspecialties. While true that each ABMS member board independently determines the eligibility, knowledge, and skill necessary for certification, it is conceivable that going forward, the various ABMS member boards might collaboratively focus on major public health threats such as obesity (as well as opioids/pain, antibiotic stewardship, etc.). Along with these potential advantages, attaining an ABMS recognized subspecialty status for obesity medicine has potential challenges, which include.

6.1. Process

ABMS recognition of a new subspecialty involves a series of processes such as identifying an acceptable number of eligible potential physicians interested in the subspecialty, as well as the existence of an acceptable number of approved fellowship programs. As previously noted, the ABMS is a nonprofit organization whose member boards manage medical specialty board certifications and maintenance of certification (MOC). If Obesity Medicine were to be recognized by the ABMS as a subspecialty, then this would likely involve an application process, with assignment to one or more ABMS Board members (e.g., ABIM, ABFM, AFP, ABOG), ultimate establishment of eligibility requirements, accreditation of a critical number of Obesity Medicine Fellowship programs, and the creation of certification exams and/or maintenance of certification requirements. If sponsored by multiple ABMS Member Boards, maintenance of the subspecialty board certification may vary – depending on the ABMS Member Board.

6.2. Potential changes to current obesity medicine certification

Requirements for ABMS/AOA certification and maintenance of certification are often fluid. It is likely that any ABMS/AOA certification process would differ from the current requirements from the ABOM. Experience suggests that changes in the certification process are not always without compromise [15].

6.3. Consequences to existing ABOM physicians

Currently, all the ABOM Diplomates are physicians, and the majority of ABOM Current Obesity Medicine Diplomates include Internal Medicine (2468) and Family Medicine (1987), followed by Pediatrics (507), Endocrinology (447), Surgery (283), Obstetrics and Gynecology (248), Gastroenterology (206), Psychiatry (125), Emergency Medicine (96), and Cardiology (48) (https://www.abom.org/stats-data-2/). If obesity medicine was to become a subspecialty recognized by a single ABMS Board, then only those board certified by that particular ABMS Member Board would be eligible to be Board Certified in Obesity Medicine. The epidemic nature of obesity, and the broad implications of obesity across multiple medical disciplines would suggest that patients with obesity might best be served by ABMS recognition of the subspecialty of Obesity Medicine through multiple ABMS Members that might include the ABIM, the ABFM, the ABP, and the ABOG, as well as other ABMS Member Boards.

6.4. Transition from current ABOM Obesity Medicine Diplomates to ABMS-recognized obesity medicine subspecialty

Some precedence exists regarding how those having an ABMS/AOA unrecognized board certification were able to transition to an ABMS/AOA recognized specialty or sub-specialty (https://www.aaem.org/UserFiles/file/president_0508.pdf#:%7E:text=Similar%20to%20other%20medical%20specialties%20in%20their%20early; https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/rccm.2509005#:%7E:text=This%20clinical%20practice%20experience%20pathway%20consists%20of%20a).

Subspecialities such as emergency medicine, sleep medicine and geriatric medicine allowed for a period of “grandfathering,” that allowed those already practicing the specialty to acquire certification without having to complete a classic fellowship commitment. Sometimes these requirements were documentation of a certain number of clinical practice hours; other times the requirements were simply to take the new examination. In these examples, a window of transition appeared to be an average of five to seven years to complete the new requirements. After this window, diplomates were required to complete a recognized Fellowship, followed by certification testing and maintenance of certification, like those newly entering the field. It is unclear if or how such a pathway option would exist for current ABOM Diplomates.

6.5. Consequences to patient care

Obesity is a worldwide epidemic [16]. The prevalence of obesity in United States adults is 42% [17]. Projections suggest that the prevalence of obesity in 2030 will be over 50% [18] Additionally, the prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among children is increasing as well [19], and is disproportionately affecting certain races and children from lower socioeconomic background [20]. If Obesity Medicine were to become sponsored by a single ABMS, and especially if current ABOM Diplomates were required to complete a fellowship in Obesity Medicine, then this would likely create a dramatic shortfall in Obesity Medicine Specialists during the same time that the obesity epidemic is increasing. This has the potential to result in adverse public health consequences that may be particularly disadvantageous to populations at higher risk for overweight and obesity (e.g., certain racial minorities and those from lower socioeconomic status). Critically important are the over 500 current Pediatric ABOM Diplomates in obesity medicine who would no longer be recognized as certified in Obesity Medicine if the subspecialty recognition was sponsored by a single ABMS Member Board such as the ABIM. This would occur at a time when 1 in 5 children and adolescents have obesity. If early treatment and prevention of obesity in children represents an opportunity to reduce adult obesity [[21], [22], [23]], then it seems paradoxical and potentially harmful to reduce or eliminate existing pediatric physicians certified as ABOM Diplomates when obesity rates in children are increasing. A potential solution would be ABMS sub-specialty sponsorship among multiple ABMS Member Boards, or reciprocity between ABMS Member Boards.

6.6. Unclear reimbursement advantages

One of the potential appeals to physicians of an ABMS/AOA recognized Obesity Medicine specialty is the potential for increased physician reimbursement. However, it is possible that most of the physician care provided by the Obesity Medicine Specialist will be cognitive based (as opposed to procedural based). If so, then as previously noted in Section 2.2 regarding subspecialities such as Endocrinology, if the Obesity Medicine Specialists utilizes the same billing codes as Internal Medicine or Family Practice physicians, then it may be challenging to imagine payers would reimburse Obesity Medicine Subspecialists at a different rate for the same billing code – irrespective of an ABMS Board Member Obesity Medicine certification.

7. Conclusion

Currently, the most common Obesity Medicine Certification for physicians in the United States occurs via the ABOM. Obesity Medicine is not recognized as a subspecialty by the ABMS. The existing certification process of obesity medicine via ABOM has resulted in a dramatic increase in the number of ABOM Diplomates. It is unclear how a transition to ABMS oversight might affect current certified ABOM Diplomates. Any deliberative process intended to achieve ABMS certification oversight of obesity medicine as a board-certified subspecialty should include an assessment of how such a change will affect current Diplomates of Obesity Medicine, as well as the future number of Obesity Medicine specialists. Among the main issues to resolve include.

-

(1)

How many ABMS Member Boards would oversee Obesity Medicine as a subspecialty and which physicians would be eligible?

-

(2)

Would current ABOM Diplomates be required to complete an Obesity Medicine Fellowship? If not, then what would be the process for a current ABOM Diplomate to transition to an ABMS-recognized Obesity Medicine subspecialist (i.e., “grandfathering criteria”)?

-

(3)

According to the ABMS, do enough Obesity Medicine Fellowship programs exist to recognize Obesity Medicine as a subspecialty?

Given the epidemic nature of the disease of obesity, decisions regarding the current ABOM Diplomate Certification, versus changing to an ABMS Member Board “Obesity Medicine” subspecialty recognition, should consider which best improves and increases medical care access to patients with obesity.

Ethics review

This submission did not involve human test subjects or volunteers.

Acknowledgements and funding

This manuscript received no funding.

Author contributions

AF and HEB created the first draft, which was reviewed and edited by DBH, CS, LA, SMC, and NJP.

Individual disclosures

AF is a Diplomate of the American Board of Obesity Medicine.

DBH is a Diplomate of the American Board of Obesity Medicine and Program Director, UT Allison Family Foundation Fellowship in Clinical Obesity Medicine and Metabolic Performance.

CS is a Diplomate of the American Board of Obesity Medicine.

LCA is a Diplomate of the American Board of Obesity Medicine.

SMC is Board Certified in Family Nurse Practitioner, and has earned the NP/PA Certificate of Advanced Education in Obesity Medicine, issued by the Obesity Medicine Association.

NJP is Board Certified in Family Medicine and is a Diplomate of the American Board of Obesity Medicine.

HEB is Board Certified in Internal Medicine, Endocrinology, and is a Diplomate of the American Board of Obesity Medicine.

Evidence

The content of the OMA Obesity Algorithm and this manuscript is supported by citations, which are listed in the References section.

Contributor Information

Angela Fitch, Email: drfitch@knownwell.health.

Deborah B. Horn, Email: Deborah.b.horn@uth.tmc.edu.

Christopher D. Still, Email: cstill@geisinger.edu.

Lydia C. Alexander, Email: Lydia.Alexander@enarahealth.com.

Sandra Christensen, Email: sam.chris@im-wm.com.

Nicholas Pennings, Email: pennings@campbell.edu.

Harold Edward Bays, Email: http://www.lmarc.com, hbaysmd@outlook.com.

References

- 1.Kushner R.F., Brittan D., Cleek J., Hes D., English W., Kahan S., et al. The American board of obesity medicine: five-year report. Obesity. 2017;25:982–984. doi: 10.1002/oby.21828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bays H.E. Future of obesity medicine: fearless 5-year predictions for 2028. Obesity Pillars. 2023;5 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gudzune K.A., Wickham E.P., 3rd, Schmidt S.L., Stanford F.C. Physicians certified by the American Board of Obesity Medicine provide evidence-based care. Clin Obes. 2021;11 doi: 10.1111/cob.12407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bays H.E., Golden A., Tondt J. Thirty obesity myths, misunderstandings, and/or oversimplifications: an obesity medicine association (OMA) clinical practice statement (CPS) 2022. Obesity Pillars. 2022;3 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2022.100034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bays H.E., Bindlish S., Clayton T.L. Obesity, diabetes mellitus, and cardiometabolic risk: an obesity medicine association (OMA) clinical practice statement (CPS) 2023. Obesity Pillars. 2023;5 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2023.100056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitch A.K., Bays H.E. Obesity definition, diagnosis, bias, standard operating procedures (SOPs), and telehealth: an Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) Clinical Practice Statement (CPS) 2022. Obesity Pillars. 2022;1 doi: 10.1016/j.obpill.2021.100004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Hoof S.J., Spreeuwenberg M.D., Kroese M.E., Steevens J., Meerlo R.J., Hanraets M.M., et al. Substitution of outpatient care with primary care: a feasibility study on the experiences among general practitioners, medical specialists and patients. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:108. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0498-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohr D.C., Eaton J.L., Meterko M., Stolzmann K.L., Restuccia J.D. Factors associated with internal medicine physician job attitudes in the Veterans Health Administration. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:244. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3015-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bayer N.D., Taylor A., Fallon A., Wang H., Santolaya J.L., Bamat T.W., et al. Pediatric residents' sense of meaning in their work: is this value related to higher specialty satisfaction and reduced burnout? Acad Pediatr. 2021;21:557–563. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joy In Medical Practice Clinician satisfaction in the healthy work place trial. Health Aff. 2017;36:1808–1814. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prashker M.J., Meenan R.F. Subspecialty training: is it financially worthwhile? Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:715–719. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-9-715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nora L.M., Wynia M.K., Granatir T. Of the profession, by the profession, and for patients, families, and communities : ABMS board certification and medicine's professional self-regulation. JAMA, J Am Med Assoc. 2015;313:1805–1806. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen S. Obesity Medicine Association (OMA): nurse practitioner & physician assistants update. Obesity Pillars. 2022;1 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yarlagadda S., Townsend M.J., Palad C.J., Stanford F.C. Coverage of obesity and obesity disparities on American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) examinations. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113:486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2021.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawkins R.E., Irons M.B., Welcher C.M., Pouwels M.V., Holmboe E.S., Reisdorff E.J., et al. The ABMS MOC Part III examination: value, concerns, and alternative formats. Acad Med. 2016;91:1509–1515. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaacks L.M., Vandevijvere S., Pan A., McGowan C.J., Wallace C., Imamura F., et al. The obesity transition: stages of the global epidemic. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:231–240. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30026-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hales C.M., Carroll M.D., Fryar C.D., Ogden C.L. NCHS Data Brief; 2020. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017-2018; pp. 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y., Beydoun M.A., Min J., Xue H., Kaminsky L.A., Cheskin L.J. Has the prevalence of overweight, obesity and central obesity levelled off in the United States? Trends, patterns, disparities, and future projections for the obesity epidemic. Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49:810–823. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsoi M.F., Li H.L., Feng Q., Cheung C.L., Cheung T.T., Cheung B.M.Y. Prevalence of childhood obesity in the United States in 1999-2018: a 20-year analysis. Obes Facts. 2022;15:560–569. doi: 10.1159/000524261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isong I.A., Rao S.R., Bind M.-A., Avendaño M., Kawachi I., Richmond T.K. Racial and ethnic disparities in early childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2018;141 doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lean M., Lara J., Hill J.O. ABC of obesity. Strategies for preventing obesity. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2006;333:959–962. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7575.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stice E., Shaw H., Marti C.N. A meta-analytic review of obesity prevention programs for children and adolescents: the skinny on interventions that work. Psychol Bull. 2006;132:667–691. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gortmaker S.L., Swinburn B.A., Levy D., Carter R., Mabry P.L., Finegood D.T., et al. Changing the future of obesity: science, policy, and action. Lancet (London, England) 2011;378:838–847. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60815-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]