Abstract

This study examined protective behavioral strategies (PBS) as a moderator of the relationship between impulsive sensation seeking and binge drinking and alcohol-related consequences in a sample of high school seniors (N = 346). Hierarchical regression analyses indicated that impulsive sensation seeking was a significant predictor of binge drinking and alcohol-related consequences and that PBS moderated these relationships. Specifically, manner of drinking moderated the relationships such that among students with high impulsive sensation seeking, those using strategies related to how they drink (e.g. avoiding rapid and excessive drinking) reported lower levels of binge drinking and alcohol-related consequences than those using fewer of these strategies. Clinical implications are discussed including using personality-targeted interventions that equip high impulsive sensation seeking adolescents with specific strategies to reduce binge drinking and alcohol-related consequences.

Keywords: adolescent drinking, impulsive sensation seeking, protective behavioral strategies

1. Introduction

Underage drinking is a significant problem in the United States, with 66% of adolescents reporting alcohol use by their senior year (Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2015). Among high school students, seniors have the highest rates of use, with 37.4% of seniors reporting alcohol use in the past 30 days, compared to 9.0% of eighth grade students, and 23.5% of tenth grade students (Johnston et al., 2015). A similar trend is evident when looking at heavy episodic drinking, with reports of binge drinking in the past 2 weeks increasing from 4.1% and 12.6% in the eighth and tenth grade, respectively, to 19.4% by the senior year (Johnston et al., 2015). Additionally, adolescent alcohol use is associated with significant negative consequences including academic, interpersonal, legal problems, and neurocognitive consequences (Arata, Stafford & Tims, 2003; French & Maclean, 2006; Hanson, Median, Padula, Tapert, & Brown, 2011; Miller, Naimi, Brewer, & Jones, 2007; Nguyen-Louie et al., 2015).

One explanation for the high rates of alcohol use and heavy drinking in high school is that this time period is associated with a high level of risky decision-making (Albert & Steinberg, 2011; D’Amico, Elickson, Collins, Martino, & Klein, 2005). Developmental neuroscience research suggest a number of structural and functional changes occur in adolescent brains that contribute to the potential for risk-taking behavior (Steinberg, 2008). Although the link between brain and behavior is complex and individual behavior is variable, patterns in neural maturation exist that help explain this component of adolescents’ experiences. Most notably, regions of the brain dominant in pleasure and reward seeking (e.g., nucleus accumbens) mature faster than regions of the brain dominant in decision-making and impulse inhibition (e.g., ventral prefrontal cortex) (Bava & Tapert, 2010; Casey, Getz, & Galvan, 2008). This differential developmental trajectory is particularly exaggerated in emotionally salient situations, such as interactions involving peers (Chein, Albert, O’Brien, Uckert, & Steinberg, 2011). Additionally, dopamine transmission, which plays an important role in affective and motivational regulation, appears to be altered in adolescents leading to heightened activation and reduced inhibition in response to potentially rewarding stimuli (Matthews, Bondi, Torres, & Moghaddam, 2013; Siegel, 2013; Wahlstrom, Collins, White, & Luciana, 2010).

Youth with genetic predispositions for increased sensation seeking behaviors may be at the highest risk for negative outcomes linked to adolescent brain development (Casey et al., 2008). Sensation seeking is a biologically-based personality trait that manifests as the tendency to seek out novel and exciting stimuli, including risk-taking behavior (Zuckerman 1979; 1994). Results of a recent meta-analysis indicate heightened impulsivity is a risk marker for heavy drinking during adolescence when impulsive behavior is high and initiation of alcohol use often occurs (Strautz & Cooper, 2013). In particular, the researchers identified sensation seeking as one of the most significant risk factors for adolescent alcohol use among disinhibitory traits (Strautz & Cooper, 2013). Research also indicates that adolescents who are high sensation seekers are more likely to use substances than low sensation seekers (Martins, Storr, Alexandre, & Chilcoat, 2008). Sensation seeking is also associated with both early onset and greater severity of substance use (Bekman, Cummins, & Brown, 2010; Crawford, Pentz, Chou, Li, & Dwyer, 2003; Ortin, Lake, Kleinman, & Gould, 2012; Urban, Kokonyei, & Demetrovics, 2008). Additionally, longitudinal research identifies sensation seeking among adolescents as a predictor of both alcohol use (MacPherson, Magidson, Reynolds, Kahler, & Lejuez, 2010) and binge drinking (Sargent, Tanski, Stoolmiller, & Hanewinkel, 2010).

To address rates of heavy drinking and the related negative consequences among adolescents, researchers have examined protective factors to understand ways to minimize risks associated with adolescent alcohol use. For example, protective behavioral strategies (PBS) have been identified to help adolescents modify drinking behaviors to buffer them from the negative consequences associated with use (Martens et al., 2005). According to Martens and colleagues (2005), PBS include strategies that occur before, during, or after drinking such as plans to stop or slow down drinking, change how one drinks to avoid rapid alcohol consumption, and behave in ways that decrease dangerous consequences. Among college students, researchers have found that using PBS decreases negative alcohol outcomes (Araas & Adams, 2008; Borden et al., 2011; Kenny & LaBrie, 2013; Zeigler-Hill, Madson, & Ricedorf, 2012). Additionally, PBS moderates the relationship between self-regulation and alcohol-related consequences among first year students, such that students with low levels of self-regulation who use PBS have lower levels of negative outcomes than those using fewer PBS (D’Lima, Pearson, & Kelley, 2012). Similarly, PBS moderates the relationship between negative urgency, the tendency to act rashly when distressed, and alcohol-related consequences among intercollegiate athletes (Weaver, Martens, & Smith, 2012). Specifically, the researchers found that athletes with high negative urgency using PBS have fewer consequences than those not using fewer PBS.

Although some researchers have identified the buffering effects of PBS for college students with traits associated with impulsivity (i.e. self-regulation and negative urgency), to date, we could find no literature examining PBS among high impulsive sensation seeking adolescents. Thus, we aimed to extend the literature by examining the moderating effects of PBS on the relationship between impulsive sensation seeking and binge drinking and alcohol-related consequences among adolescents. In particular, we selected high school seniors as they are at greatest risk for heavy drinking and negative outcomes among school-aged students. Based on the college literature, we hypothesized that PBS would moderate the relationship between impulsive sensation seeking and binge drinking and alcohol-related consequences. Specifically, we predicted that among students with high impulsive sensation seeking, those using PBS would report less binge drinking and fewer alcohol-related consequences than students using fewer PBS. We were also interested in which types of PBS would be significant moderators of the relationship between impulsive sensation seeking and alcohol outcomes.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants in the current study were high school seniors recruited from two high schools in the Northwest. Because the School District Research Board required parental consent for all students regardless of age, consent forms were sent to parents of all students (N = 832), including those who were 18 years old. A total of 389 (47%) parents provided consent. Among students with parental consent, those who were in attendance at school (n = 360) were given an opportunity to participate. Among these students, 346 (48.8% male, 51.2% female) provided assent. Participant ages ranged from 15 to 18 (M = 17.16, SD = 0.45). Participants were primarily Caucasian (82.2%), with 5.8% Hispanic, 5.2% Asian, 1.5% African-American, 1.2 % American Indian/Alaskan Native, and 4.1% other.

2.3. Procedure

A member of the research team contacted the principals at two of the largest high schools within the capitol district in a northwest region of the United States to invite the schools to participate in the study. All seniors registered at the schools were eligible to participate. The schools contacted all parents of seniors via letter by mail at their permanent addresses provided by the registrar’s office. A parental consent form and a project-addressed, stamped envolope were enclosed in the letter. Parents were asked to return signed consent forms indicating permission for their adolescent to participate in the study. In addition, a phone number and email address were provided so that parents could ask questions prior to signing the consent form. Reminder letters were also sent to the student’s home address and sent home with the students to give to the parents. Participants who received parental consent to participate were asked to assent prior to participating in the survey.

A member of the research team recruited students during a common core class period. Students with parental consent met at the school’s computer lab to participate in the study. A member of the research team and a school counselor described the research study and invited the students to participate. Students who agreed to participate were given a unique personal identification number (PIN) to maintain confidentiality and a URL to access the survey. Students then logged onto the survey website where they read a welcome screen explaining the research and were asked for their assent to participate. Once students gave assent by clicking “Agree”, they were taken to a screen that asked them to enter their PIN and were then directed to begin the survey, which took approximately 20 minutes to complete. Students who did not have parental consent or who did not provide assent remained in their classroom with their teacher and completed an alternative exercise. All study procedures were approved by the University Institutional Review Board and the School District Research Board.

2.4. Measures

2.3.1. Binge Drinking

Frequency of binge drinking was defined as consuming 5 or more drinks in a row for males (3 or more for females) in a 2 hour period during the last 2 weeks. The 5/3 quantity has been identified as appropriate for adolescents aged 16-17 based on BAC levels for this age group (Donovan, 2009).

2.3.1. Alcohol-Related Consequences

Alcohol-related consequences were assessed using the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989). The RAPI is a 23-item self-administered screening tool for assessing adolescent problem drinking. Participants were asked “how many times have the following scenarios happened to you while you were consuming alcohol or as a result of your drinking in the past 30 days.” Responses were measured on a 5-point scale ranging from never to more than 10 times. A total consequence score was created by summing the 23 items. The RAPI has good internal consistency (Neal & Carey, 2004) and test-retest reliability (Miller et al., 2002) and has been correlated significantly with several drinking variables (White & Labouvie, 1989). Coefficient alpha for this sample was α = .86.

2.3.3. Impulsive Sensation Seeking

The Zuckerman–Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire (ZKPQ; Zuckerman, Kuhlman, Joireman, Teta, & Kraft, 1993) was used to assess sensation seeking. The ZKPQ is a 40-item forced choice questionnaire designed to measure five personality traits. For the purposes of this study, only the 19-item Impulsive Sensation Seeking (ImpSS) scale was used. The ImpSS items reflect a lack of planning (e.g. “I usually think about what I am going to do before doing it” reverse scored), a tendency to act impulsively (e.g., “I often do things on impulse”), a need for excitement and thrills (e.g. “I like to have new and exciting experiences and sensations even if they are a little frightening), a preference for unpredictability (e.g. “I enjoy getting into new situations where you can’t predict how things will turn out”), and a need for novelty and change (e.g. “I tend to change interests frequently”). The ImpSS scale has been psychometrically validated with college students, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .77 - .82 (Zuckerman et al., 1993). The ImpSS has also been used to validate shorter measures of sensation seeking for adolescents (Stephenson, Hoyle, Palmgreen, & Slater, 2003). The ImpSS scale Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was α = .77.

2.3.3. Protective Behaviors

The Protective Behavioral Strategy Scale (PBSS; Martens et al., 2005) was used to assess protective behaviors. The PBSS is a 15-item measure used to assess cognitive–behavioral strategies used to reduce risky drinking. Respondents rate the degree to which they engage in certain behaviors when using alcohol using a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The PBSS is psychometrically validated with college students (Martens et al., 2005; Martens, Pederson, LaBrie, Ferrier, & Cimini, 2007) and has been used with adolescents (Grazioli, Dillworth et al., 2015; Grazioli, Lewis, Garberson, Fossos-Wong, Lee, & Larimer, 2015). The measure assesses three types of protective behaviors: Stopping/Limiting Drinking (7 items; α = .92; e.g. “Determine not to exceed a set number of drinks,” “Stop drinking at a predetermined time”), Manner of Drinking (5 items; α = .91; “Avoid drinking games”, “Drink slowly, rather than gulp or chug”), and Serious Harm Reduction (3 items; α = .94; “Use a designated driver”, “Know where your drink has been at all times”).

2.6. Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21. Bivariate correlations among predictor and dependent variables were calculated prior to conducting the main regression analyses (see Table 1). Although several of the correlations were significant at p < .01, the variance inflation factor (VIF) ranged between 1.1 - 6.9, with corresponding tolerance levels ranging from .15 - .96. The VIF is below the rule of thumb of VIF < 10 (Norman & Streiner, 2008), suggesting acceptable levels of multicollinearity among the predictor variables. Outcome variables were also examined for skew and kurtosis. The distribution for binge drinking and alcohol-related consequences did not substantially deviate from the normal distribution. In addition to testing for basic assumptions for ordinary least squares regression, we also tested for homogeneity of error variance (Fairchild & MacKinnon, 2009). Results indicated the studentized residuals and unstandardized predicted values for the outcome variables were equivalent across high (> 0) and low (≤ 0) values of impulsive sensation seeking.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Bivariate Correlations for Drinking Variable, Sensation Seeking, and Protective Behavioral Strategies

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Binge drinking | __ | |||||

| 2. Alcohol consequences | .49** | __ | ||||

| 3. Impulsive sensation seeking | .12* | .13* | __ | |||

| 4. Stopping/limiting drinking | .21** | .25** | .08 | __ | ||

| 5. Manner of drinking | .03 | .11* | .02 | .81** | __ | |

| 6. Serious harm reduction | .33** | .38** | −.02 | .10 | .86** | __ |

| M | 0.52 | 2.00 | 22.11 | 16.80 | 12.02 | 9.11 |

| SD | 1.06 | 3.59 | 3.76 | 8.54 | 6.37 | 5.06 |

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

We also examined demographic differences in drinking variables, impulsive sensation seeking, and protective behavioral strategies. With the exception of gender, demographic variables were not significantly related to the variables of interest. Results indicated males reported higher levels of impulsive sensation seeking (M = 28.54, SD = 3.86) than females (M = 27.66, SD = 3.60), t(342) = 2.19, p < .05, Cohen’s d = .24. Additionally, males reported lower levels of limiting/stopping drinking (M = 15.06, SD = 7.76) than females (M = 18.39, SD = 8.93), t(342) = −3.68, p < .001, Cohen’s d = −.40, lower levels of manner of drinking (M = 11.14, SD = 6.00) than females (M = 12.83, SD = 6.64), t(342) = −2.47, p < .01, Cohen’s d = −.27, and lower levels of serious harm reduction (M = 8.13, SD = 4.76) than females (M = 10.01, SD = 5.19), t(342) = −3.51, p < .001, Cohen’s d = −.38. Thus, we included gender as a covariate in the following analyses. Means and standard deviations for drinking variables, impulsive sensation seeking, and protective behavioral strategies are presented in Table 1.

Our aim was to test whether the relationship between sensation seeking and adolescent drinking behavior is moderated by protective behavioral strategies. To test this aim, two hierarchical regression analyses were conducted, with interaction effects used to test for moderation. All predictor variables were mean centered to reduce problems of multicolinearity introduced into equations containing interaction terms (Aiken & West, 1991). Interaction terms were created by computing the product of impulsive sensation seeking and each PBS variable. We also controlled for gender in each analyses. Gender was entered on Step 1, impulsive sensation seeking was entered on Step 2, the three PBS variables were entered simultaneously on Step 3, and the three impulsive sensation seeking x PBS interaction terms were entered simultaneously on Step 4 to examine the moderating effects of PBS. Simple slopes were used to examine the direction and degree of significant interactions (Aiken & West, 1991). All analyses were conducted at p < .05. Table 3 presents results from the regression models.

Table 3.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analysis for Alcohol-Related Consequences

| Step | Predictor | ΔR2 | B | SE B | β | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | .00 | |||||

| Gender | .18 | .39 | .03 | [−.58, .94] | ||

| 2 | .02** | |||||

| Impulsive sensation seeking | .13 | .05 | .14** | [.03, .23] | ||

| 3 | .19*** | |||||

| Stopping/limiting drinking | −.02 | .05 | −.05 | [−.12, .08] | ||

| Manner of drinking | −.17 | .05 | −.29*** | [−.26, −.07] | ||

| Serious harm reduction | .45 | .07 | .63*** | [.31, .58] | ||

| 4 | .03** | |||||

| ImpSS x SLD | .03 | .01 | .23 | [−.00, .05] | ||

| ImpSS x MOD | −.04 | .01 | −.29*** | [−.07, −.02] | ||

| ImpSS x SHR | .02 | .02 | .08 | [−.02, .05] |

Note: ImpSS = impulsive sensation seeking; SLD = stopping/limiting drinking; MOD = manner of drinking; SHR = serious harm reduction.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

3. Results

3.1. Binge Drinking

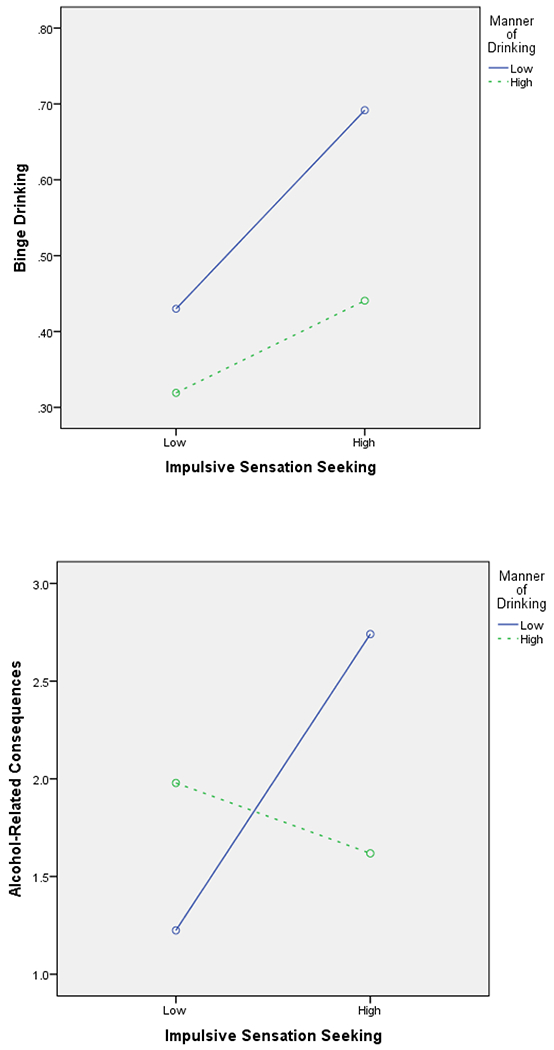

The full regression equation was significant for binge drinking, F(8, 335) = 12.12, p < .001. Examination of the adjusted R2 indicates impulsive sensation seeking and PBS accounted for 21% of the variance in binge drinking. As seen in on Step 2, results showed that impulsive sensation seeking was a significant predictor of binge drinking (p < .05). As hypothesized, higher levels of impulsive sensation seeking were associated with higher levels of binge drinking. Further, as seen on Step 4, the interaction between impulsive sensation seeking and manner of drinking was significant (p < .01). To examine the nature of the interactions, tests of simple slopes were graphed and interpreted using Aiken and West’s (1991) procedures. Figure 1 presents the significant two-way interaction between impulsive sensation seeking and manner of drinking. High and low impulsive sensation seeking and manner of drinking categories were created by using a mean split (≤ 0, and > 0). Examination of the slopes in Figure 1 indicates that among participants with high impulsive sensation seeking, those using more manner of drinking strategies reported lower frequency of binge drinking than those using fewer manner of drinking strategies.

Figure 1.

Manner of Drinking as a Moderator of the Relationship between Impulsive Sensation Seeking and Drinking Variables

3.2. Alcohol-Related Consequences

The full regression equation was significant for alcohol-related consequences, F(8, 335) = 12.81, p < .001. Examination of the adjusted R2 indicates impulsive sensation seeking and PBS accounted for 22% of the variance in alcohol-related consequences. As seen in on Step 2, results showed that impulsive sensation seeking was a significant predictor of alcohol-related consequences (p < .01). As hypothesized, higher levels of impulsive sensation seeking were associated with higher levels of alcohol-related consequences. Further, as seen on Step 4 the interaction between impulsive sensation seeking and manner of drinking was significant (p < .001). To examine the nature of the interactions, tests of simple slopes were graphed and interpreted using Aiken and West’s (1991) procedures. High and low impulsive sensation seeking and manner of drinking categories were created by using a mean split (≤ 0, and > 0). Figure 1 presents the significant two-way interaction between impulsive sensation seeking and manner of drinking. Examination of the slopes in Figure 1 indicates that among participants with high impulsive sensation seeking, those using more manner of drinking strategies reported fewer alcohol-related consequences than those using fewer manner of drinking strategies.

4. Discussion

This study examined the moderating effects of PBS on the relationship between impulsive sensation seeking and binge drinking and alcohol-related consequences among high school seniors. Findings from this study indicated impulsive sensation seeking was a significant predictor of both binge drinking and alcohol-related consequences. These findings are consistent with research indicating high sensation seeking among adolescents is associated with high rates of substance use (MacPherson et al., 2010; Martins et at., 2008), early onset and greater severity of substance use (Bekman et al., 2010; Crawford et al., 2003; Ortin et al., 2012; Urban et al., 2008), and binge drinking (Sargent et al., 2010).

Results from the current study also indicate that among high impulsive sensation seeking seniors, those using more PBS reported less binge drinking and fewer alcohol-related consequences than those not using PBS. In particular, manner of drinking moderated the relationship, suggesting that using strategies to avoid excessive drinking buffered the impact of impulsive sensation seeking on both binge drinking and alcohol-related consequences. These findings are consistent with research suggesting the PBS serve a protective function for college students with low-self regulation (D’Lima et al., 2012). Similarly, findings are consistent with research demonstrating that manner of drinking moderates the relationship between negative urgency and alcohol-related problems (Weaver et al., 2012). Thus, PBS that decrease rapid consumption of alcohol, serve as a buffer against binge drinking and negative alcohol outcomes associated with high impulsive sensation seeking.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine PBS as a moderator of the relationship between impulsive sensation seeking and alcohol outcomes in among adolescents. This study, however, is not without limitations. First, due to a primarily Caucasian sample form the Northwest region, generalizability is limited. Generalizability is also limited by convenience sampling and a low response rate (< 50%). Although the response rate in this study is similar to other school-based research using active parental consent (30% - 60%) (Smith, Boel-Studt, & Cleeland, 2009), the issue of nonresponse bias should be considered. School samples recruited with active parental consent procedures are generally less diverse, have fewer high-risk participants (Shaw, Cross, Thomas, & Zubrick, 2014; Smith et al., 2009), and have participants with lower rates of alcohol use (Doumas, Esp, & Hausheer, 2015) than those recruited with passive consent. Second, although the PBSS measure is commonly used in research with young adults and college students, use with younger participants is limited to two prior studies (Grazioli, Dillworth, et al, 2015; Grazioli, Lewis, et al, 2015). Another limitation is that information in this study was obtained through self-report. Self-reported alcohol use is common practice in studies examining alcohol use among adolescents and the reliability and validity of self-reported use in this age group have been demonstrated (Flisher, Evans, Muller, & Lombard, 2004; Lintonen, Ahlstrom, & Metso, 2004). Specific steps were taken, however, to minimize social desirability and response bias, including providing assurances regarding confidentiality, which was discussed at length with students as part of the student assent process. Finally, cross-sectional data were used in this study, limiting our ability to determine the direction of the relationships of interest.

An additional interpretational consideration concerns the effect sizes found for the moderating effects of PBS. Effect sizes for the interaction between impulsive sensation seeking and manner of drinking for binge drinking and alcohol-related consequences were small. Prior research examining PBS as a mediator for constructs related to sensation seeking (i.e. negative urgency), however, report similar effect sizes (R2 = .01 - .02) and standardized beta weights (β = .11 - .15) for the interaction between negative urgency and PBS (Weaver et al., 2012). Although the moderating effect of PBS may be small, identifying variables that are related to lower levels of alcohol use among high impulsive sensation seeking adolescents is important. Thus, future research examining the efficacy of training PBS with high impulsive sensation seeking adolescents is a crucial next step in understanding the efficacy of using PBS to buffer high impulsive sensation seeking adolescents from heavy drinking and the negative associated consequences.

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study have significant implications. Heavy alcohol use in adolescence disrupts critical aspects of brain development that can result in lasting deficits in neural functioning (Bava & Tapert, 2010). Additionally, alcohol use in high school is predictive of heavy drinking in both college and non-college-attending young adults (White, Fleming, Kim, Catalano, & McMorris, 2008; White et al., 2006). Thus, it is imperative to identify efficacious interventions for high school seniors not only to reduce heavy drinking in this age group, but to disrupt patterns of drinking that extend into emerging adulthood. Because high impulsive sensation seeking is associated with heavy drinking and the negative associated consequences, intervention strategies designed specifically for high impulsive sensation seeking students are needed.

Because sensation seeking is considered to be a biologically driven personality trait (Zuckerman 1979; 1994), rather than try to change impulsive sensation seeking tendencies, it may be more effective to teach high impulsive sensation seeking youth strategies to minimize heavy drinking and the associated negative consequences. Personality-targeted interventions provide brief, personality-specific coping skills intended to change how adolescents manage their personality risk, including enhancing motivation and exploring new ways of coping (Conrad, Stewart, Comeau, & Maclean, 2006). Research indicates that brief personality-targeted interventions based on motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral therapy effectively reduce alcohol use (Conrad, Castellanos-Ryan, & Mackie, 2011; Conrad, Castellanos-Ryan, & Strang, 2010; Conrad et al., 2013; Conrad et al., 2006), particularly among high sensation seeking adolescents (Conrad, Castellanos, & Mackie, 2008). Further, these studies evaluated brief personality-targeted interventions delivered within two 90-minute group sessions by therapists (Conrad et al., 2011; Conrad et al., 2010) and teachers (Conrad et al., 2013). Thus, it should be feasible for personnel to implement brief personality-targeted interventions in the school setting, as well as for clinicians to integrate this type of intervention into ongoing therapies.

Results from this study also indicate training high impulsive sensation seeking adolescents to use PBS may be useful. Specifically, PBS that change how one drinks, such as avoiding drinking games, shots, and gulping, avoiding mixing different types of alcohol, and not trying to out-drink others, may be most beneficial. In contrast, strategies that are designed to stop or limit drinking, including planning ahead of time not to exceed a certain amount of drinks, stopping drinking at a certain time, or leaving a party at a predetermined time may be less effective for high sensation seeking adolescents. Strategies to reduce serious harm, such as knowing where your drink has been at all times and making sure you go home with a friend, similarly may be less effective for this population. Targeting specific PBS may be used in conjunction with personality-targeted interventions to reduce harmful drinking among these students. However, more research is needed to examine the efficacy of incorporating specific PBS into personality-targeted interventions for high impulsive sensation seeking adolescents.

5. Conclusion

This study provides preliminary findings that indicate PBS may buffer the link between high impulsive sensation seeking and heavy drinking and alcohol-related consequences among high school seniors. These findings suggest brief personality-targeted interventions that equip high sensation seeking adolescents with skills to reduce excessive and rapid drinking may be beneficial. Examining the efficacy of incorporating PBS into these interventions is an important next step in identifying interventions for high impulsive sensation seeking adolescents.

Table 2.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analysis for Binge Drinking

| Step | Predictor | ΔR2 | B | SE B | β | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | .00 | |||||

| Gender | −.03 | .11 | −.01 | [−.26, .20] | ||

| 2 | .01* | |||||

| Impulsive sensation seeking | .03 | .02 | .11* | [.01, .06] | ||

| 3 | .19*** | |||||

| Stopping/limiting drinking | .01 | .02 | .07 | [−.02, .04] | ||

| Manner of drinking | −.07 | .01 | −.44*** | [−.10, −.05] | ||

| Serious harm reduction | .12 | .02 | .59*** | [.08, .16] | ||

| 4 | .02* | |||||

| ImpSS x SLD | .01 | .00 | .24 | [.00, .02] | ||

| ImpSS x MOD | .01 | .00 | −.24** | [−.02, −.01] | ||

| ImpSS x SHR | .00 | .01 | .01 | [−.01, .01] |

Note: ImpSS = impulsive sensation seeking; SLD = stopping/limiting drinking; MOD = manner of drinking; SHR = serious harm reduction.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Jaime Johnson, Kristen Shearer, Rhiannon Trull, Laura Cromwell, and Laura Mundy for their assistance in participant recruitment and data collection. Funding for this study was provided in part by a National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant award number U54GM104944 and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration Grant (SAMHSA) award number 93.959. The National Institutes of Health and SAMHSA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. CA: US Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Albert D, & Steinberg L (2011). Judgment and decision making in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 211–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00724.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Araas TE, & Adams TB (2008). Protective behavioral strategies and negative alcohol related consequences in college students. Journal of Drug Education, 38(3), 211–224. doi: 10.2190/DE.38.3.b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arata CM, Stafford J, & Tims MS (2003). High school drinking and its consequences. Adolescence, 38, 567–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bava S, & Tapert SF (2010). Adolescent brain development and the risk for alcohol and other drug problems. Neuropsycholoical Review, 20, 398–413. doi: 10.1007/s11065-0109146-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekman NM, Cummins K, & Brown SA (2010). Affective and personality risk and cognitive mediators of initial adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 71, 570–580. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borden LA, Martens MP, McBride MA, Sheline KT, Bloch KK, & Dude K (2011). The role of college students’ use of protective behavioral strategies in the relation between binge drinking and alcohol-related problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25, 346–351. doi: 10.1037/a0022678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Getz S, & Galvan A (2008). The adolescent brain. Developmental Review, 28, 62–77. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chein J, Albert D, O’Brien L, Uckert K, & Steinberg L (2011). Peers increase adolescent risk taking by enhancing activity in the brain’s reward circuitry. Developmental Science, 14, 1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad PJ, Castellanos J, & Mackie C (2008). Personality-targeted interventions delay the growth of adolescent drinking and binge drinking. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.01826.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Castellanos-Ryan N, & Mackie C (2011). Long-term effects of a personality-targeted intervention to reduce alcohol use in adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 296– 306. doi: 10.1037/a0022997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Castellanos-Ryan N, & Strang J (2010). Brief, personality-targeted coping skills interventions and survival as a non-drug user over a 2-year period during adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67, 85–93. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, O’Leary-Barrett M, Newton N, Topper L, Castellanos-Ryan N, Mackie C, & Girard A (2013). Effectiveness of a selective, personality-targeted prevention program for adolescent alcohol use and misuse: a cluster randomized controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 70, 334–342. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad PJ, Stewart SH, Comeau N, & Maclean AM (2006). Preventative efficacy of cognitive behavioral strategies matched to the motivational bases of alcohol misuse in at-risk youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35, 550–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford AM, Pentz MA, Chou CP, Li C, & Dwyer JH (2003). Parallel developmental trajectories of sensation seeking and regular substance use in adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17(3), 179–192. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.3.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Elickson PL, Collins RL, Martino SK, & Klein DJ (2005). Processes linking adolescent problems to substance-abuse problems in late young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66, 766–775. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Lima GM, Pearson MR, & Kelley ML (2012). Protecive behavioral strategies as a mediator and moderator of the relationship between self-regulation and alcohol-related consequences in first-year college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26(2), 330–337. doi: 10.1037/a0026942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE (2009). Estimated blood alcohol concentrations for child and adolescent drinking and their implications for screening instruments. Pediatrics, 123, 975–981. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Esp S, & Hausheer R (2015). Parental consent procedures: Impact on response rates and nonresponse bias. Journal of Substance Abuse and Alcoholism, 3, 1031–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild AJ, & MacKinnon DP (2009). A general model for testing mediation and moderation effects. Prevention Science, 10, 87–99. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0109-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flisher AJ, Evans J, Muller M, & Lombard C (2004). Brief report: Test-retest reliability of self-reported adolescent risk behavior. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2001.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French MT, & Maclean JC (2006). Underage alcohol use, delinquency, and criminal activity. Health Economics, 15, 1261–1281. doi: 10.1002/hec.1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grazioli VS, Dillworth T, Witkiewitz K, Andersson C, Kilmer JR, Pace T,…Larimer ME (2015). Protective behavioral strategies and future drinking behaviors: Effects of drinking intentions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29, 355–364. doi: 10.1037/adb0000041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grazioli VS, Lewis MA, Garberson LA, Fossos-Wong N, Lee CM, & Larimer ME (2015). Alcohol expectancies and alcohol outcomes: Effects of the use of protective behavioral strategies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76, 452–458. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson KL, Medina KL, Padula CB, Tapert SF, & Brown SA (2011). Impact of adolescent alcohol and drug use on neuropsychological functioning in young adulthood: 10-year outcomes. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 20, 135–154. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2011.555272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2015). Monitoring the future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. Retrieved from: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney SR, & LaBrie JW (2013). Use of protective behavioral strategies and reduced alcohol risk: Examining the moderating effects of mental health, gender, and race. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27, 997–1009. doi: 10.1037/a0033262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lintonen T, Ahlstrom S, & Metso L (2004). The reliability of self-reported drinking in adolescence. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 39, 362–368. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson L, Magidson JF, Reynolds EK, Kahler CW, & Lejuez CW (2010). Changes in sensation seeking and risk-taking propensity predict increases in alcohol use among early adolescents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 34, 1400–1408. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01223.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Sheehy MJ, Corbett K, Anderson DA, & Simmons A (2005). Development of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 66, 698–705. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Pederson ER, Labrie JW, Ferrier AG, & Cimini MD (2007). Measuring alcohol-related protective behavioral strategies among college students: Further examination of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Scale. Psychology of Addictive Behavior, 21(3), 307–315. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins SS, Storr CL, Alexandre PK, & Chilcoat HD (2008). Adolescent ecstasy and other drug use in the National Survey of Parents and Youth: The role of sensation-seeking, parental monitoring and peers’ drug use. Addictive Behaviors, 33, 919–933. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews M, Bondi C, Torres G, & Maghaddam B (2013). Reduced presynaptic dopamine activity in adolescent dorsal striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology, 38, 1344–1351. doi: 10.10381/npp.2013.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ET, Neal DJ, Roberts LJ, Baer JS, Cressler SO, Metrick J, & Marlatt GA (2002). Test-retest reliability of alcohol measures: Is there a difference between internet-based assessment and traditional methods? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 16, 56–63. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.16.1.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JW, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, & Jones SE (2007). Binge drinking and associated health risk behaviors among high school students. Pediatrics, 119, 76–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, & Carey KB (2004). Developing discrepancy within self-regulation theory: Use of personalized normative feedback and personal strivings with heavy-drinking college students. Addictive Behaviors, 29, 281–297. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Louie TT, Castro N, Matt GE, Squeglia LM, Brumback T, & Tapert SF (2015). Effects of emerging alcohol and marijuana use behaviors on adolescents’ neuropsychological functioning over four years. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 76(5), 738–748. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman GR, & Streiner DL (2008). Biostatistics: The bare essentials (3rd ed.). Hamilton, Ontario: B.C. Decker, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ortin A, Lake AM, Kleinman M, & Gould MS (2012). Sensation seeking as risk factor for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in adolescence. Journal of Affective Disorders, 143, 214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Tanski S, Stoolmiller M, & Hanewinkel R (2010). Using sensation seeking to target adolescents for substance use interventions. Addiction, 105, 506–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02782.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw T, Cross D, Thomas LT, & Zubrick SR (2015). Bias in student survey findings for active parental consent procedures. British Educational Research Journal, 41, 229–243. doi: 10.1002/berj.3137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel DJ (2013). Brainstorm: The power and purpose of the teenage brain. New York, NY: Penguin Group. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DC, Boel-Studt S, & Cleeland L (2009). Parental consent in adolescent substance abuse treatment outcome studies. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 37, 298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. (2008). A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review, 28, 78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson MT, Hoyle RH, Palmgreen P, & Slater MD (2003). Brief measures of sensation seeking for screening and large-scale surveys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 72(3), 279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strautz K, & Cooper A (2013). Impulsivity-related personality traits and adolescent alcohol use: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 574–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbán R, Kökönyei G, & Demetrovics Z (2008). Alcohol outcome expectancies and drinking motives mediate the association between sensation seeking and alcohol use among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 33, 1344–1352. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlstrom D, Collins P, White T, & Luciana M (2010). Developmental changes in dopamine neurotransmission in adolescence: Behavioral implications and issues in assessment. Brain and Cognition, 72, 146–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver CC, Martens MP, & Smith AE (2012). Do protective behavioral strategies moderate the relationship between negative urgency and alcohol-related outcomes among intercollegiate athletes? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73, 498–503. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Fleming CB, Kim MJ, Catalano RF, & McMorris BJ (2008). Identifying two potential mechanisms for changes in alcohol use among college-attending and non-college attending emerging adults. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1625–1639. doi: 10.1037/a0013855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, McMorris BJ, Catalano RF, Fleming CB, Haggerty KP, & Abbott RD (2006). Increases in alcohol and marijuana use during the transition out of high school into emerging adulthood: The effects of leaving home, going to college, and high school protective factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67, 810–822. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW (1989). Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 50(1), 30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeigler-Hill V, Madson MB, & Ricedorf A (2012). Does self-esteem moderate the associations between protective behavioral strategies and negative outcomes associated with alcohol consumption? Journal of Drug Education, 42, 211–227. doi: 10.2190/DE.42.2.f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. (1979). Sensation seeking: Beyond the optimal level of arousal. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. (1994). Behavioral expression and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. Cambridge University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M, Kuhlman DM, Joireman J, Teta P, & Kraft M (1993). A comparison of three structural models for personality: The big three, the big five, and the alternative five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 757–768. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.65.4.757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]