Abstract

Multidrug-resistant bacteria are causing a serious global health crisis. A dramatic decline in antibiotic discovery and development investment by pharmaceutical industry over the last decades has slowed the adoption of new technologies. It is imperative that we create new mechanistic insights based on latest technologies, and use translational strategies to optimize patient therapy. Although drug development has relied on minimal inhibitory concentration testing and established in vitro and mouse infection models, the limited understanding of outer membrane permeability in Gram-negative bacteria presents major challenges. Our team has developed a platform using the latest technologies to characterize target site penetration and receptor binding in intact bacteria that inform translational modeling and guide new discovery. Enhanced assays can quantify the outer membrane permeability of β-lactam antibiotics and β-lactamase inhibitors using multiplex liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. While β-lactam antibiotics are known to bind to multiple different penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), their binding profiles are almost always studied in lysed bacteria. Novel assays for PBP binding in the periplasm of intact bacteria were developed and proteins identified via proteomics. To characterize bacterial morphology changes in response to PBP binding, high-throughput flow cytometry and time-lapse confocal microscopy with fluorescent probes provide unprecedented mechanistic insights. Moreover, novel assays to quantify cytosolic receptor binding and intracellular drug concentrations inform target site occupancy. These mechanistic data are integrated by quantitative and systems pharmacology modeling to maximize bacterial killing and minimize resistance in in vitro and mouse infection models. This translational approach holds promise to identify antibiotic combination dosing strategies for patients with serious infections.

Antibiotics were once “Magic Bullets” that saved many millions of lives. The discoveries of penicillin in 1928, the first modern antibiotic (a β-lactam), and of streptomycin in 1943, an aminoglycoside antibiotic, fundamentally transformed medicine. A lack of effective antibiotics threatens modern medical practice and procedures, such as surgery, chemotherapy, organ transplants, and care of premature neonates.

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria are causing a global health crisis, which is exacerbated by a lack of effective antibiotic treatment options.1-3 These bacterial isolates are resistant to most or all antibiotics in monotherapy. Due to diminishing financial benefits, pharmaceutical industry has substantially downsized their efforts and infrastructure in antibiotic discovery and development and the number of new antibiotics declined dramatically since the 1980s.4-8 Although this number increased over the last 5 years, these new antibiotics were developed based on efforts from several decades past. Importantly, these new agents (except ceftazidime/avibactam) are severely struggling economically or are already no longer available clinically. This highlights the severe economic challenges of the antibiotic marketplace. Currently, small companies and academia are leading most antibiotic development programs. There is a broad consensus about the urgent need for new mechanistic insights, based on latest technologies, and collaborations to successfully combat the crisis caused by MDR pathogens.

Minimal inhibitory concentration and its shortcomings

Traditionally, antibiotic development has heavily relied on minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing in large and diverse strain collections, and also on established in vitro and mouse infection models.9-13 Whereas the MIC is the most common measure of antibiotic activity, it reflects a conglomerate of bacterial target site penetration, efflux, receptor binding, potential intracellular drug inactivation, and any other tolerance or resistance mechanisms that may manifest within 16–24 hours of incubation. Therefore, two drug candidates can have the same high MIC, but due to completely different underlying mechanisms. Data at the mechanistic level are required to elucidate the contributions of these factors.

Experimental models

Founded on the ground breaking mouse infection model work by Harry Eagle at the National Institutes of Health in the 1940s and 1950s,14 William Craig and co-workers greatly enhanced these models in the 1970s and 1980s.15,16 Major improvements included the establishment of cyclophosphamide regimens to render mice neutropenic. This substantially enhanced the diversity of bacterial strains that can be studied in mice without auto-clearing of the infecting bacteria in absence of antibiotic treatment. Subsequently, Craig et al. established mouse thigh infection models that assessed both thighs, and the mouse lung infection model.

The mouse thigh and lung infection models have become a cornerstone of antibiotic development and their methodology has remained largely unchanged.9 These mouse models and dynamic in vitro models, such as the hollow fiber infection model, have played a critical role in identifying the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) indices that best predict bacterial killing (e.g., at 24 hours).9,17,18 Mouse models are usually performed over 24 hours and they are typically limited to a 48 or 72-hour treatment duration. In contrast, the hollow fiber infection model can study clinically relevant durations of therapy (i.e., weeks to months, if needed) and is the gold-standard tool to assess both bacterial killing and resistance prevention.9 The PK/PD indices include the area under the unbound concentration time curve divided by the MIC (fAUC/MIC), the unbound peak concentration by MIC ratio (fCmax/MIC), the time of unbound concentration above the MIC (fT > MIC), and the free trough concentration by MIC ratio (fCtrough/MIC). The PK/PD index approach relies on the MIC as the only measure of antibiotic activity and cannot distinguish between the many mechanisms contributing to high or low MICs. Although PK/PD indices have been extremely helpful to optimize antibiotic monotherapy, this approach has major limitations for optimizing drug combinations even for the most common case of a β-lactam and a β-lactamase inhibitor (BLI) that is inactive by itself.19

Mathematical modeling

Empiric mathematical modeling of bacterial growth and killing started in the 1960s by Edward Garrett’s group.20 These models described irreversible drug effects and were refined in the 1970s to include multiple inter-converting cell populations by William Jusko21 for anticancer therapy. Subsequently developed models include saturable bacterial killing,22 a plateau to reflect the maximum bacterial density,23,24 and multiple bacterial populations with different antibiotic susceptibilities,25-30 as reviewed previously.19,31,32 Almost all of these models fit data for the total bacterial population only, and a large number of studies did not experimentally determine antibiotic-resistant or tolerant subpopulation(s) (e.g., via antibiotic-containing agar plates and MIC testing of resistant colonies). As a substantial step forward, models were developed to simultaneously fit data on the growth and killing of the susceptible and resistant populations and were prospectively validated.26 The next series of models characterized the inoculum effect (i.e., greatly diminished and/or slower bacterial killing at high compared with low initial inocula) for three antibiotic classes,33-36 implemented pharmacogenomics data,37,38 or characterized the effects of the immune system.39-43

Optimizing treatment outcomes

Subsequently, both empirical and mechanism-based models have been developed to rationally optimize antibiotic monotherapy and combination therapy dosage regimens based on in vitro and animal infection model data.44-49 Monte Carlo simulations are often utilized to predict antibiotic efficacy in the presence of between patient variability in PKs.10,19,50 Most of these Monte Carlo simulations compared the simulated antibiotic concentration time-profiles in patients to a PK/PD index target (e.g., from mice) in order to predict treatment outcomes. Some Monte Carlo simulations combined a population PK model with a mechanism-based PD model to predict the time-course of bacterial killing and resistance, and ultimately treatment outcomes.45,46 Some of these models implemented mechanistic experimental data.35,47 Although the above models paved the way to rationally optimize combination therapies to combat MDR bacteria, it became increasingly obvious that more mechanistic insights were required to underpin this translational modeling strategy.

This tutorial presents a platform of novel approaches and assays on how to leverage latest technologies to understand bacterial target site penetration, receptor binding, as well as the mechanisms of synergy and resistance prevention. Ultimately, this approach holds promise and allows one to rationally optimize antibiotic combination therapies for patients. The latest generation of Quantitative and Systems Pharmacology (QSP) models for antibiotics enables us, for the first time, to incorporate the rate of penetration and mass balance at the bacterial target site. A thorough understanding of the experimental assays and computational approaches is beneficial to guide drug development and move the field forward.

MECHANISTIC ASSAYS TO COMBAT MDR ISOLATES VIA SYNERGISTIC COMBINATION THERAPIES

Antibiotic monotherapy is no longer viable to successfully combat serious infections with a high bacterial burden by MDR isolates of the most clinically important Gram-negative bacterial “superbugs.”2 These pathogens include Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli, and often cause serious infections of the respiratory tract, bloodstream, urinary tract, diabetic foot, as well as combat and burn wounds. These infections are associated with high morbidity, up to 87% mortality and high rates (up to 60%) of resistance emergence during therapy.51,52 Serious infections, such as ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia, carry a very high bacterial burden and patients are often immunocompromised.53 In this highly challenging scenario, preventing emergence of bacterial resistance by antibiotic monotherapy is virtually impossible and optimal combination dosing strategies are most beneficial.10,19,54-58 However, major mechanistic gaps exist on how to combine available antibiotics to treat infections by MDR isolates.

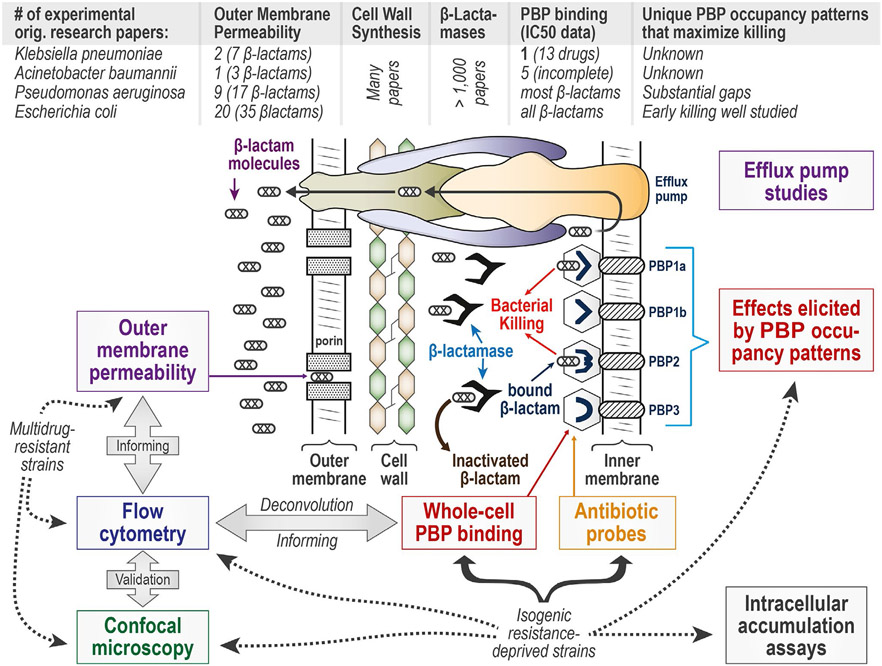

Despite penicillin having been discovered over 90 years ago and β-lactams representing the most commonly used class of antibiotics, gaps remain in understanding bacterial target site penetration and whole-cell receptor binding of β-lactams and other antibacterial agents. The number of original research papers in this area is relatively small for four of the most important Gram-negative pathogens (Figure 1). Fortunately, a platform of novel assays provides important and complementary insights using contemporary technologies. Although some assays are ideally applied in resistance-deprived genetically engineered strains, other assays are best suited for studies in MDR strains. When combined, these assays mutually inform and cross-validate each other to better understand bacterial target site penetration, as well as the mechanisms of antibiotic action, synergy, and resistance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Bacterial target site penetration as well as mechanisms of action and resistance for β-lactam and other antibiotics in Gram-negative bacteria. A β-lactam has to penetrate through outer membrane (OM) porin channels, then avoid being inactivated by β-lactamases or effluxed, in order to ultimately covalently bind the penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) on the outer side of the inner membrane. For the four most important Gram-negative pathogens, very few original research papers provided experimental data on the rate of OM penetration. Whereas many papers characterize cell wall (i.e., peptidoglycan) synthesis and β-lactamases, considerable gaps remain regarding PBP binding in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii. In these two pathogens, it is essentially unknown which PBPs should be inactivated; considerable gaps on PBP occupancy patterns also exist in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The developed suite of novel assays includes OM permeability assays, cell morphology changes elicited by PBP binding characterized by flow cytometry and confocal microscopy, whole-cell PBP binding, the synthesis of antibiotic probes, as well as intracellular accumulation and receptor binding assays. This proposed assay platform can elucidate the contributions of target site penetration and receptor binding. Some of these assays are best applied in resistance-deprived genetically engineered strains, whereas other assays are ideally suited for studies in multidrug resistant strains. All these mechanistic data can be integrated by Quantitative and Systems Pharmacology modeling to translate mechanistic insights into optimal monotherapy and combination dosing strategies for patients’ therapy.

ENHANCED OUTER MEMBRANE PERMEABILITY ASSAYS FOR β-LACTAMS AND BLIs

Background

In Gram-negative bacteria, all β-lactams and BLIs have to penetrate the outer membrane (OM) before they can inactivate their PBP target receptors in the periplasm (Figure 1). Extremely limited published data is available on the OM permeability of clinically relevant β-lactams and BLIs in A. baumannii and K. pneumoniae.8,59 A few studies evaluated the OM permeability of some β-lactams in P. aeruginosa.60-65

Innovations

We improved the original OM permeability assay by Zimmermann and Rosselet66 by four critical innovations and published the first comprehensive dataset on β-lactam permeability in K. pneumoniae.67 First, we developed an efficient cassette assay to assess OM permeability of five β-lactams simultaneously in K. pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae (Figure 2a,b; two of five drugs shown). The discrete assay was validated by studying each drug individually. Second, a new cassette assay leverages liquid-chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) technology and offers the ability to simultaneously quantify 5 to 20 drugs despite similar physicochemical properties. These LC-MS/MS based assays are significantly more sensitive and specific than older spectrophotometric methods used by all prior OM permeability studies. Third, we developed a novel assay to assess the OM penetration rate of a BLI that is used to protect a rapidly penetrating victim β-lactam (e.g., imipenem; Figure 2c,d). Fourth, we developed and validated the first OM permeability assay for A. baumannii that can account for the release of β-lactamases during incubation in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).68 This assay considerably broadened the number of bacterial strains that can be studied. The increase of extracellular β-lactamases was characterized by proteomics (unpublished data) and the rise of β-lactamase activity quantified by LC-MS/MS.

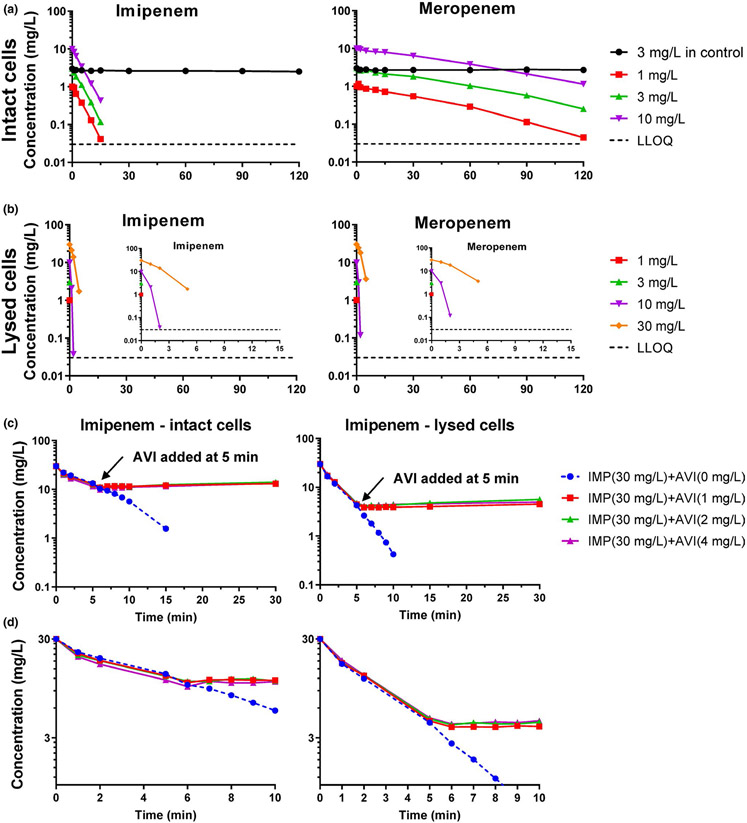

Figure 2.

Concentration-time profiles of imipenem and meropenem for the cassette assay of the polymyxin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate KP3800. Both β-lactams were dosed at 3 mg/L for the supernatant control, and at 1, 3, or 10 mg/L each for intact bacteria arms (a). Bacteria in the initial inoculum (9.0·108 CFU/mL) were thoroughly washed six times before adding the antibiotics to the intact cell arms. (b) Shows the rapid decline of drug concentrations in lysed cells. Bacteria in the initial inoculum (1.8·108 CFU/mL) were thoroughly washed six times before lysis and adding the antibiotics to the lysed cell arms. (c) Shows a novel assay that characterized the rate of bacterial target site penetration and β-lactamase inhibition in intact and lysed cells of K. pneumoniae KP3800. Imipenem was used as a rapidly penetrating victim β-lactam. Avibactam was added at 5 minutes. During the first 5 minutes, imipenem concentrations declined rapidly. After adding avibactam, the decline of imipenem was essentially completely prevented within 1–2 minutes. This demonstrated that avibactam rapidly penetrated the outer membrane and inhibited the β-lactamase activity. (d) Shows the first 10 minutes of (c) magnified. Parts of this figure are reprinted with permission from the American Society for Microbiology (ASM); Kim et al.67. AVI, avibactam; IMP, imipenem; LLOQ, lower limit of quantification.

Assays

These enhanced assays study the rate of decline of extracellular β-lactam concentrations with or without lysing the bacterial cells (Figure 2a,b). The assays require a β-lactamase that inactivates the β-lactams to be studied. The rate of hydrolysis of the β-lactams is first assessed in lysed bacteria when β-lactams are freely exposed to β-lactamases (Figure 2b). Then, the rate of hydrolysis is assessed in intact bacteria (Figure 2a). For this assay, bacterial cells are thoroughly washed (4–6 times) to assure removal of any extracellular β-lactamase activity. It is assumed that all β-lactamase-related hydrolysis occurs in the periplasm. Therefore, β-lactams have to first penetrate the OM before they can be inactivated by β-lactamases (Figure 1). This creates a permeability limited clearance scenario. If a β-lactam penetrates rapidly (e.g., imipenem; Figure 2a) the extracellular β-lactam concentration declines fast in intact bacteria. However, for more slowly penetrating β-lactams (e.g., meropenem), the extracellular concentrations decline more slowly when using intact bacteria. For an extremely slowly penetrating β-lactam, the extracellular drug concentration would only minimally decrease when intact bacteria are used. A control arm is included to demonstrate the absence of extracellular β-lactamase activity after the last wash. This control arm lacks bacterial cells, but may contain extracellular proteins (e.g., β-lactamases) and outer membrane vesicles. Constant drug concentrations for this control arm demonstrate a lack of extracellular β-lactamase activity and sufficient thermal stability of the studied drugs. When studying metallo-β-lactamases, it is important to add the cation that is required for the β-lactamase activity.

For this OM permeability assay, it is critical to efficiently and completely lyse bacteria in a small and precisely defined volume for subsequent LC-MS/MS analysis. We found lysis by bead-beating using a Precellys® Evolution homogenizer with the associated micro-organism lysing kit most suitable. Lysis is performed with the Cryolys® Evolution cooling unit with dry-ice to maintain low temperatures during sample grinding. This prevents enzyme degradation (e.g., of β-lactamases). This instrument offers the flexibility to process samples of different volumes (from 0.5 to 15 mL) and lysing up to 24 samples requires less than 1 minute.

We further developed a novel assay that can characterize the rate of OM penetration by a β-lactamase inhibitor (here avibactam). Imipenem was used as a rapidly penetrating victim β-lactam. Once avibactam was added at 5 minutes, the rate of imipenem hydrolysis approached zero within 1–2 minutes (Figure 2c,d). This demonstrated that avibactam rapidly penetrated and reached effective concentrations in periplasm within 1–2 minutes. This assay works best, if the BLI inhibits all β-lactamases in the studied strain. If avibactam had penetrated more slowly, the imipenem concentration time-curve would have gradually changed from the steep down-slope to a horizontal line. Instead, we observed a sharp elbow shape, demonstrating rapid penetration and β-lactamase inhibition by avibactam. Consequently, the half-life of BLI penetration can be estimated from the curvature (or lack thereof) of the imipenem concentration profile (Figure 2c,d).

Assay validation

A discrete and a cassette version of the OM permeability assay in K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae were both validated. The discrete assay studied each drug by itself, whereas the cassette assay evaluated five drugs simultaneously. With both assay variants yielding comparable results,67 potential drug-drug interactions relating to influx, β-lactamase hydrolysis, and efflux had a limited or no impact. The lack of drug-drug interactions likely needs to be validated in each strain to be studied. Moreover, it should be assured, either by knockout of the relevant efflux pump(s) or by using an efflux pump inhibitor at a suitable concentration, that efflux has minimal or no impact on the OM permeability results as we showed previously.67 If present, considerable efflux pump activity would yield smaller estimates for the observed net permeability (i.e., the observed net influx rate is equal to the rate of influx minus the rate of efflux). Furthermore, it is important to study MDR strains that are not extensively killed by the studied β-lactam(s). Bacterial killing may be slower and less extensive (or absent), because bacteria are likely nonreplicating or slowly replicating when incubated in PBS at the used high bacterial inoculum (usually > 108 CFU/mL). Confirming limited or no bacterial killing during incubation in PBS is important.

Future considerations

Most published studies used 5 mM MgCl2 (without Ca2+) as the divalent cation concentration to minimize leakage of β-lactamase activity during the 120 minutes of incubation in PBS. This concentration is considerably higher than the concentration of Mg2+ and Ca2+ in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (1.14 mM together for both divalent cations). Future research is needed to evaluate the impact of these cation concentrations on the OM permeability determined by this assay.35,69 This is particularly important when studying permeabilization of the OM by a polymyxin or an aminoglycoside, because these polycationic antibiotics compete with Mg2+ and Ca2+ for the negative binding sites on the OM.35,47

In some cases, β-lactamase activity increases during incubation of bacteria in PBS over 120 minutes. As highlighted previously, this scenario leads to substantially biased (i.e., far too high) OM permeability estimates.59,68 We have recently solved this issue by developing a more elaborate assay that characterizes and corrects for the increase of extracellular β-lactamase activity over time. This allows one to determine the OM permeability of β-lactams in A. baumannii for the first time. For P. aeruginosa, expression of the AmpC β-lactamase can be rapidly and extensively induced by PBP4 binding.70 A novel hyperporination assay has been developed in multiple pathogens as an additional tool to assess the rate of OM penetration for multiple classes of antibiotics.71

Key outcomes and integration into translational QSP models

This permeability assay platform is ideally suited to efficiently quantify the rate of OM penetration by β-lactams and BLIs in MDR isolates with extensive β-lactamase activity. By modifying the presence or expression of OM porins and of efflux pumps, the impact of porins and efflux can be quantified. These insights are likely critical to characterize and better understand the potentially large strain-to-strain variability in OM permeability. Moreover, these assays can characterize synergy due to OM permeabilization by an aminoglycoside or a polymyxin. These novel, mechanistic insights can be used to inform rate constants in the latest mass-balance based QSP models or implemented as covariates to predict bacterial target site concentrations in mechanism-based PK/PD models. Comprehensive OM permeability data for β-lactams and BLIs in Gram-negative bacteria provide important insights to support antibiotic discovery and design optimal combination dosage regimens.

PBP BINDING ASSAYS IN LYSED AND INTACT BACTERIA, AND KINETIC PBP BINDING ASSAY

Background

All β-lactam antibiotics covalently bind to and thereby inactivate one or multiple different PBPs as their primary targets in bacteria (Figure 1). Although PBP binding data are available for many β-lactams in E. coli and P. aeruginosa,72-81 these data were published during several decades using different methods (Figure 1). The first series of studies used radiolabeled β-lactams (iodine labeling), whereas later studies used Bocillin™ FL82 and other fluorogenic probes.83 However, little is known about the PBP binding profiles of β-lactams in many clinically important pathogens, including A. baumannii84-89 and K. pneumoniae.90,91 Almost all of these studies assessed PBP binding in lysed bacteria.

β-Lactam antibiotics have been used for decades to successfully treat susceptible isolates of these pathogens as monotherapy. However, monotherapy may not be completely adequate for treating serious infections with a high bacterial burden of MDR isolates. The gaps of knowledge about PBP binding in important pathogens and about the rate of bacterial target site penetration greatly hinder rationally optimizing double β-lactam combination therapies (with or without a BLI or with a third, non-β-lactam antibiotic).58,74 These gaps further hamper the development of new PBP inhibitors.

Innovations

A small number of studies assessed PBP binding in intact E. coli and Streptococcus pneumoniae75; bacterial cells were incubated for 30 minutes in PBS in the presence of a β-lactam. We are only aware of one published study that assessed the time-course of PBP binding over several hours for intact bacteria growing in broth medium.92 This study utilized a lytic-deficient S. pneumoniae and radiolabeled penicillin G. To the best of our knowledge, published data are not available using whole-cell PBP binding for K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii and very few studies are available for P. aeruginosa.93,94 We recently optimized such time-course PBP binding assays in intact Gram-negative bacteria as a frame of reference (Figure 3).

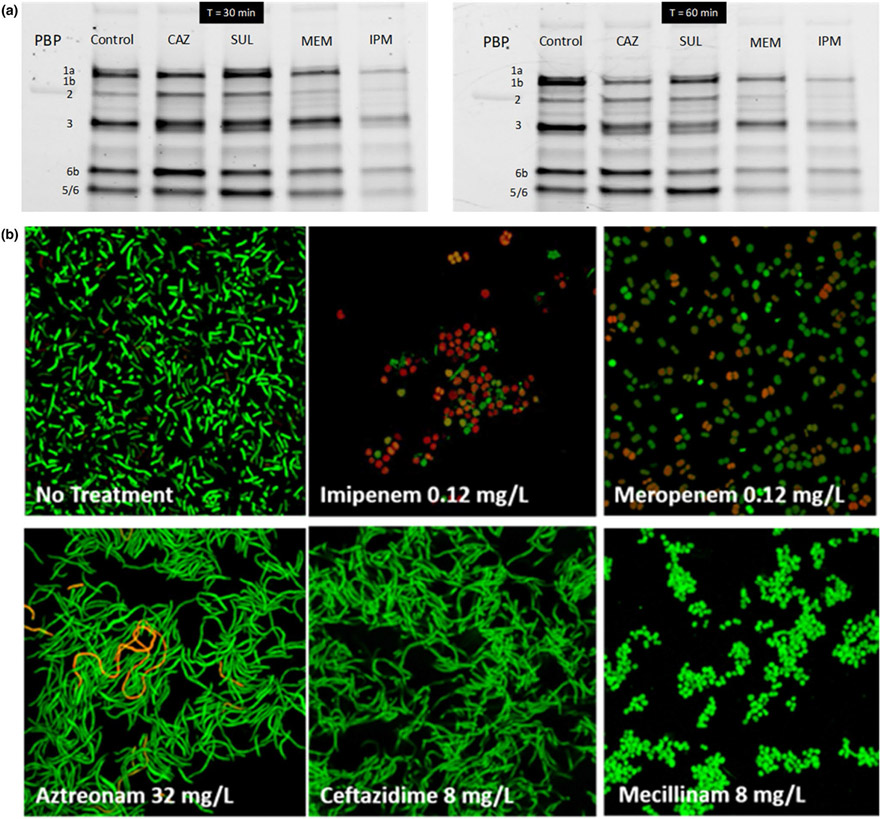

Figure 3.

Whole cell penicillin-binding protein (PBP) binding assay in Acinetobacter baumannii strain ATCC 19606 and confirmation by bacterial morphology changes. (a) Whole cells (initial inoculum: 107 CFU/mL) were incubated for 30 minutes (left) or 60 minutes (right) in the presence of imipenem (IPM; 2 mg/L), meropenem (MEM; 4 mg/L), sulbactam (SUL; 4 mg/L), or ceftazidime (CAZ; 32 mg/L). Membranes were then collected by ultracentrifugation and PBPs labeled with the fluorogenic probe Bocillin™ FL. CAZ bound PBP3 and PBP1a and SUL inactivated PBPs 1a, 1b, and 3. Whereas both MEM and IPM inactivated all PBPs, imipenem penetration and thus PBP binding was substantially faster than that by MEM as shown by the gels at 30 minutes. (b) Bacterial morphology of A. baumannii ATCC 19606 (at 106 CFU/mL) assessed for six different β-lactams via confocal microscopy. After 3 hours of incubation with the respective drug, bacteria were spun down and washed several times with PBS. Confocal images were obtained with BacLight live/dead staining.

Advances in ultra-high resolution mass spectrometry along with substantial improvements with nano-liquid chromatography have greatly enhanced the ability to definitively identify and quantify proteins in complex mixtures. Nanoflow chromatography considerably improves the sensitivity and detection of analyte molecules using nanospray methodology for subsequent mass-spectrometry analysis. Current mass-spectrometry technology has greatly improved the precursor ion isolation and detection, fast positive and negative-ion mode switching, increased resolving power (currently up to 240,000), and offers better than sub parts-per-million mass accuracy. This means that an ionized molecule with mass/charge ratio of 300.0000 can be distinguished from a molecule with mass/charge ratio of 300.0001. This allows proteomics to definitively identify and quantify proteins and their post-translational modifications based on unique peptide sequences that contain as few as 5 to 20 amino acids from digested proteins. Proteomics provides information directly at the protein level using samples of complex mixtures and was critical to identify PBPs in K. pneumoniae90 and Mycobacterium abscessus.95,96 Thus, proteomics approaches are critical when determining PBP binding in previously unstudied pathogens.

More recently, a series of papers described the expression of individual PBP enzymes in E. coli. These PBPs were subsequently harvested and isolated to perform kinetic binding studies of individual PBPs via a new fluorescence anisotropy assay.87,95,97-99 These studies provide in-depth insights into the binding kinetics at the individual PBP level.

PBP binding assays for intact bacteria using isolated membrane fractions

The covalent binding of β-lactams to PBPs offers the unique advantage in that all resistance mechanisms (including potentially slow OM permeability, β-lactamases, and efflux) are accounted for when studying whole-cell PBP binding. We developed a novel assay that characterizes the time-course of PBP binding in intact A. baumannii100 and other Gram-negative bacteria. Bacteria were incubated with 4 different β-lactams in monotherapy in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth, and harvested at 30 and 60 minutes (Figure 3). Bacterial cells were then washed twice in PBS, lysed, and total membrane fractions collected by ultracentrifugation. Subsequently, unbound PBPs were labeled by Bocillin™ FL and fluorescent bands separated by SDS-PAGE gel analysis before scanning. This assay was also successfully applied during several hours of antibiotic exposure in A. baumannii100 and P. aeruginosa (unpublished data).

For this assay, we assert that it is important to optimize the time-point of harvesting bacteria for membrane isolation, because the expression of some PBPs can change extensively with growth phase.101 This is especially critical for characterizing binding to PBPs with low expression (e.g., PBP2 in K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa). Optimizing the method of efficient and gentle cell lysis is important. Initially, we used multiple rounds of ultrasonication under ice-cooling with carefully chosen on/off sonication cycles.90,99 Later, we found a modern version of a French pressure cell (model FBG12800, Pressure Cell Homogenizer (up to 60,000 psi); Stansted Fluid Power, Harlow, Essex, UK) to be more efficient and provide considerably better signal to noise ratios.96 With either of these systems, the minimum volume of the bacterial suspension to be lysed is ~ 10–15 mL. A laser scanner (Amersham Typhoon RGB)90,96 provided substantially better sensitivity and signal to noise ratios than a chemiluminescence scanner; the latter could not detect lowly expressed PBPs.

In a whole-cell PBP binding assay, imipenem (2 mg/L) clearly penetrated and inactivated PBPs in A. baumannii faster and more extensively than meropenem (4 mg/L; Figure 3a). This was in good agreement with our OM permeability data in A. baumannii where imipenem penetrated substantially faster than meropenem68 and with the results from the lysed cell PBP binding assay in A. baumannii. For ceftazidime and sulbactam, PBP binding was less extensive and slightly slower than that by meropenem (Figure 3a).

Confocal microscopy with live/dead staining confirmed that imipenem caused more bacterial killing and a larger fraction of dead (i.e., red) cells than meropenem after 3 hours of drug exposure (Figure 3b). The PBP2 binding mecillinam and both carbapenems led to spherical cells, whereas aztreonam and ceftazidime led to long filaments (i.e., multiple cells attached to each other at the pole side; Figure 3b). This demonstrated the synergy of combining whole-cell PBP binding with confocal microscopy studies.

Fluorescence anisotropy kinetic binding assay using purified PBPs

Determining the binding kinetics of β-lactams by a new fluorescence anisotropy assay87,95,97-99 allows one to generate in-depth kinetic binding data at the single PBP level in absence of other PBPs and of other proteins (such as β-lactamases). This novel assay can be used to determine the micro-constants of binding. The assay requires each studied PBP to be expressed in E. coli, for example, and be subsequently isolated. Purified PBPs provide a cleaner background compared with the Bocillin™ FL binding assay that uses isolated membrane fractions. The fluorescence anisotropy assay measures the ability of a β-lactam to compete with fluorescent Bocillin™ FL for time-dependent PBP acylation. The second-order rate constant of acylation97 (k2/K) is then estimated. However, the deacylation rate constant k3 is more difficult to be determined, because it is very slow. However, the deacylation rate is not or much less clinically relevant for PBPs, because replication of Gram-negative bacteria and thus the rate of PBP synthesis is faster than the deacylation half-lives.97,98 The binding of Bocillin™ to a PBP starts with an initial non-covalent complex (Bocillin:PBP). Subsequently, a covalent bond is formed between Bocillin and the PBP (Bocillin-PBP*); this is detected on SDS-PAGE gels as a signal. This is followed, at a slow rate, by the deacylation step for recovery of the PBP and formation of hydrolyzed Bocillin:

Such micro-constants are difficult to determine by the Bocillin™ FL binding assay using isolated membrane fractions,82,90 because this assay determines PBP binding simultaneously for all PBPs. The latter scenario is, however, closer to the physiological situation at the periplasmic target site of bacteria where penetrating β-lactam molecules are competing for binding of several different PBPs. Thus, the combination of the PBP binding assays using isolated membrane fractions and intact bacteria, as well as the fluorescence anisotropy assay, provide a realistic and comprehensive understanding of PBP binding and target site penetration.

Future considerations

The three different PBP binding assays described above have been developed and optimized. These assays are most beneficial when used in concert in future research. To rationally optimize β-lactam antibiotic therapy, knowledge of PBP binding in lysed bacteria is an important first step. However, binding data from lysed bacteria does not account for bacterial target site penetration. Any β-lactam that requires high (i.e., supra-physiological) concentrations in a lysed cell binding assay will not be a clinically useful binder for the respective PBP.96

These PBP binding studies may be affected by the presence of excessive β-lactamase activity in membrane fractions, which can cause hydrolysis of Bocillin™ FL. This can be minimized by additional washing steps or by selective inactivation of the respective β-lactamase gene(s). Importantly, various PBPs can differ considerably in their expression. The kinetic binding assay on purified PBPs provides reasonable data on the binding at the single PBP level, but does not consider the presence and relative expression of all other PBPs and the rate of bacterial target site penetration.

Key outcomes and integration into translational QSP models

The PBP binding assay in lysed bacteria efficiently characterizes the β-lactam and BLI concentrations required to bind the different PBPs at their natural relative expression. For this assay, the drug concentration (half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50)) that half-maximally inhibits the Bocillin™ FL signal is reported. The novel whole-cell PBP binding assay characterizes the rate and extent of bacterial target site penetration and of covalent PBP binding of all targeted PBPs in intact bacteria. A notable strength of this assay is that it accounts for the impact of all resistance mechanisms, which affect PBP binding (e.g., efflux, β-lactamase activity, and porin expression). The kinetic binding assay further provides the micro-constants of PBP binding. Overall, using the lysed and intact cell PBP binding assays and the kinetic binding assay in concert greatly enhances the understanding of target site binding and the mechanisms of β-lactam action (Figure 1).

The IC50s from the lysed cell binding assay can be integrated into QSP models to describe PBP binding via reversible binding equations. We have found this to be a reasonable approximation for susceptible K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa strains (unpublished data), even though β-lactams bind PBPs covalently. The kinetic binding assay provides valuable insights into the micro-constants for covalent PBP binding. Such QSP models can be further enhanced by integrating mass-balance equations for the rate of bacterial target site penetration, the binding kinetics of different PBPs, as well as potential hydrolysis by β-lactamases and efflux (Figure 1). In future QSP models, the fraction of bound PBPs over time can be directly fit as a dependent variable to estimate the rates of target site penetration and receptor binding. As simpler, alternative approaches, the fraction of bound PBPs in intact cells can be implemented semiquantitatively as covariates are compared against the predicted time-course of bound PBPs. Overall, this integrated experimental and QSP modeling approach provides an unprecedented level of detail for the target site penetration and PBP binding in Gram-negative bacteria.

HIGH-THROUGHPUT CONFOCAL MICROSCOPY AND FLOW CYTOMETRY

Background

Inhibition of PBPs causes pronounced changes in bacterial morphology with different shapes of damaged cells, because the PBPs are intimately involved in different parts of the cell wall synthesis machinery. Confocal, transmission electron, scanning electron, cryo-electron, and atomic force microscopy, as well as other advanced techniques have been successfully used to characterize bacterial morphology changes and cell damage with excellent resolution.47,102,103 These techniques require fixing of samples (i.e., “dead” bacteria) as well as considerable time for sample preparation and analysis. Thus, they are less suitable for high-throughput analyses of multiple treatment and control arms at several time-points and for the analysis of live bacteria.

Flow cytometry is a powerful technique to analyze cell shapes, sizes, as well as to identify and differentiate cells with specific molecular markers. In oncology, mammalian cells are often analyzed with > 30 colors each of which represents a different cellular property. The relatively small size of bacteria has made flow cytometry analyses more difficult. Older generation flow cytometers provided relatively poor sensitivity (i.e., at low bacterial densities). Although samples can be concentrated, this will also concentrate any cell debris after extensive bacterial killing. Overall, flow cytometry has been much less frequently used to characterize antibiotic efficacy.

Innovations

Highest quality image analysis is in the domain of the above-mentioned advanced microscopy techniques. However, recent advances in high-throughput, automated time-lapse microscopy have enabled this technology and its automated image analysis algorithms to be more widely adopted for live imaging of bacteria.

Assays

We have implemented automated high-throughput microscopy in a 96-well plate format. Current technology offers highly sufficient image resolution (even at 60× magnification) without the use of an oil or water-immersion interface. Although the latter immersion techniques would improve image quality, they make it more difficult to automate the image capture and to maintain the system. Capturing images with multiple fields of view (i.e., imaging sites) for a static drug concentration time-kill study with 12 or more treatment or control arms at multiple time points is highly feasible. This was achieved on an ImageXpress® Micro Confocal High-Content Imaging system (by Molecular Devices), which provides auto-focusing capabilities. We applied multiple (> 10) z-stacks to obtain a 3D image and used 4 different imaging sites for each sample. Even with these advanced settings, it took less than 60 seconds to automatically capture all images for one sample.

The cell morphology changes elicited by primarily PBP3 binding (with some binding of PBP1a and PBP1b) by sulbactam and by predominant PBP2 binding by mecillinam were pronounced (Figure 4). Even at relatively low drug concentrations of both agents, the combination yielded considerable and synergistic bacterial killing. Capturing these time-lapse images provided powerful insights about the target receptor(s) inactivated by the studied antibiotics and about the subsequent morphology changes over time. The associated images (along with images of diluted samples) can be analyzed at the single cell level to characterize different cell properties (e.g., size, length, and roundness of bacterial cells). Thereby, this assay provides indirect insights into the bacterial target site penetration and receptor binding of an antibiotic, because the cell shape can be used via a deconvolution algorithm to back-calculate (i.e., reverse engineer) which PBPs were bound.104

Figure 4.

Confocal microscopy characterizing morphology changes of a genetically engineered, resistance deprived strain of Acinetobacter baumannii that lacks two efflux pumps and both β-lactamases (i.e., a ΔampC, ΔblaOxa-51, ΔadeABC, ΔadeIJK derivative of AB307-0294). We previously determined in this strain that sulbactam (SUL) preferentially binds penicillin-binding protein (PBP)3 and to a lesser extent PBP1a and PBP1b and that mecillinam (MEC) highly preferentially binds PBP2. Sulbactam 0.5 mg/L is equivalent to 0.25× the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of PBP3 (and 0.125× the IC50 of PBP1a and PBP1b) in this A. baumannii strain. Mecillinam 0.0625 mg/L is equivalent to 2× the IC50 of PBP2 in this strain. The Live/Dead BacLight stains viable bacteria green and dead bacteria red. Inactivation of PBP2 by MEC led to small and subsequently larger spherical cells. Inactivation of PBP3 as well as PBP1a and PBP1b by SUL led to short and increasingly longer filaments. Simultaneous inactivation of PBPs 1a, 1b, 2, and 3 by MEC and SUL led to spherical cells with considerable killing. This assay used a low initial inoculum of 5.3 logl0 (CFU/mL) and thus had good sensitivity. An ImageXpress® Micro Confocal High-Content Imaging system from Molecular Devices was used.

Pairing high-throughput microscopy with high-throughput flow cytometry provides an even greater depth of insights. Contemporary flow cytometry can quantify low numbers of viable bacteria (at least down to 104 CFU/mL, and likely lower) without or with sample concentration. Although microscopy analyzes a certain subset of cells in the captured field(s) of view, flow cytometry provides quantitative data on all cells in the sample and can label multiple cellular properties by different fluorescent markers. Flow cytometry using 96-well plates is highly efficient; each sample analysis takes less than 60 seconds.

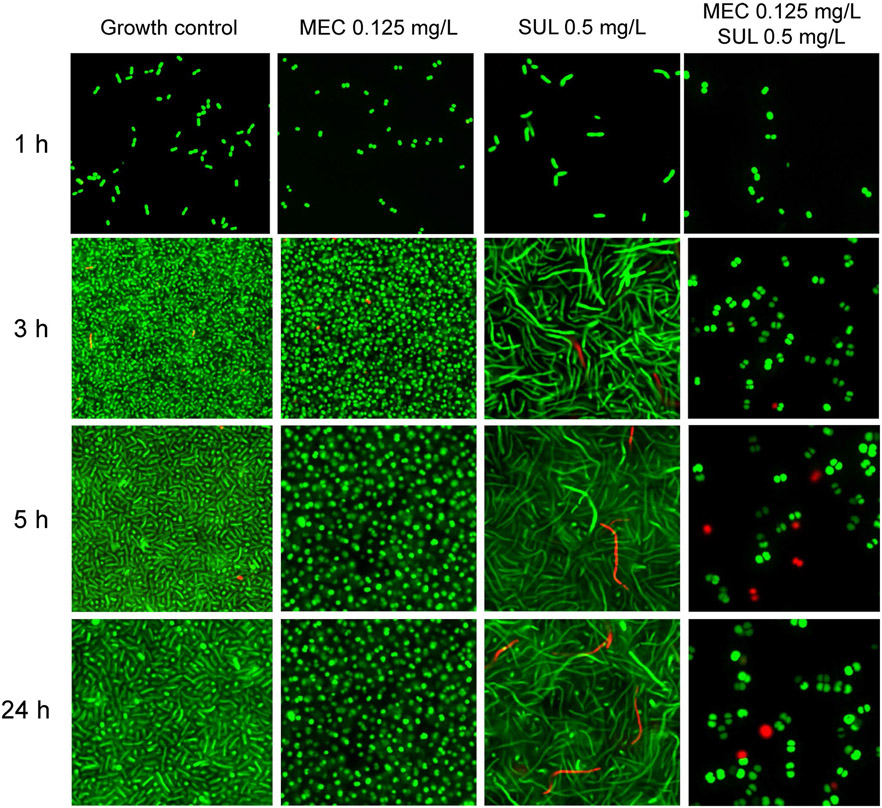

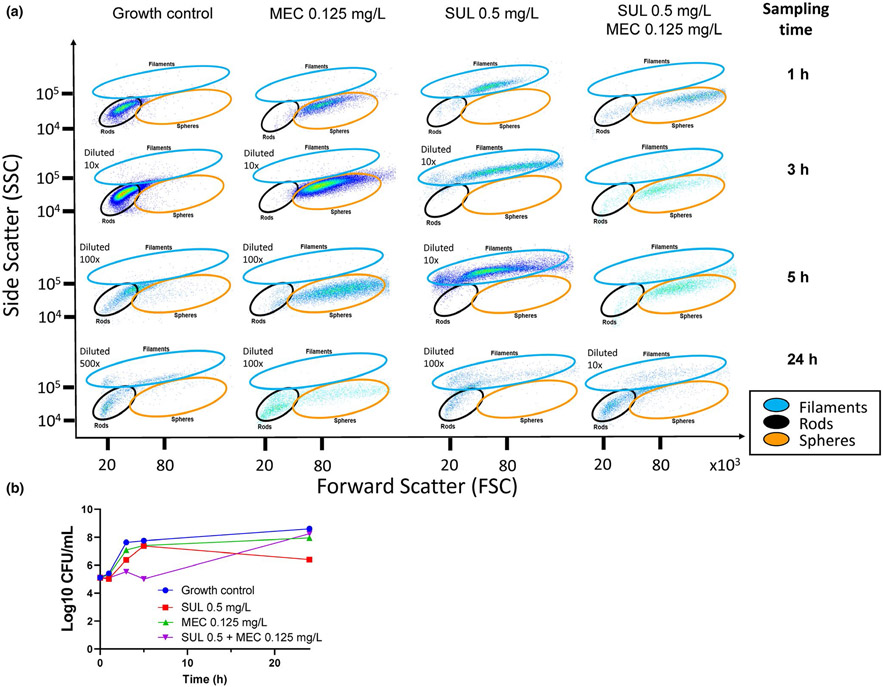

In our study (Figures 4, 5), the morphology changes elicited by PBP2 binding mecillinam and by PBP3 (as well as PBP1a and PBP1b) binding sulbactam differed distinctly. Moreover, the drug combination yielded additional damage, as shown by the greater shift of damaged bacteria exposed to combination therapy in flow cytometry (Figure 5). We stained and selected for SYTO9-positive cells (i.e., viable cells) and plotted the forward and side-scatter. These analyses efficiently removed debris and allowed for the quantification and characterization of various cell morphologies determined based on controls and confirmed by confocal microscopy.

Figure 5.

Flow cytometry assay characterizing morphology changes of a resistance-deprived Acinetobacter baumannii strain for the same experiment shown in Figure 4 and viable count profiles. (a) Bacterial cells were fluorescently labeled with SYTO9 (live) and propidium iodide (dead). Bacterial cell morphology changes could be clearly distinguished by the forward and side scatter. Mecillinam (i.e., PBP2 binding) led to spherical cells and sulbactam (PBP3 binding with some PBP1a and PBP1b binding) led to increasingly longer filaments. The combination caused considerable bacterial killing and led to spherical cells. We used a Beckman Coulter CytoFLEX flow cytometer that provided excellent sensitivity even at the low initial inoculum of 5.3 log10 (CFU/mL) used in this experiment. (b) Static drug concentration time-kill profiles for this experiment. Flow cytometry was highly sensitive to detect morphology changes and synergy at low sulbactam concentrations (i.e., 0.25× the IC50 of PBP3). Higher drug concentrations (i.e., 0.5× and 1× IC50 of PBP3) yielded more extensive synergy. CFU, colony-forming unit; IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration; MEC, mecillinam; PBP, penicillin-binding protein; SUL, sulbactam.

Future considerations

Combining high-throughput confocal microscopy with flow cytometry provides mechanistic insights that cannot be resolved by a traditional in vitro time-kill experiment. We have found that these technologies can rapidly characterize bacterial damage by at least five antibiotic classes (unpublished data). High-throughput imaging analyses provide an unprecedented level of time-course data using live bacteria. The latest technology advances have recently become available in flow-cytometers with sorting capabilities. This will allow one to select bacteria with specific cellular properties according to the fluorescent markers and to recover these cells for subsequent analyses. This can be applied in combination with studies on fluorescently labeled bacterial strains and nonreplicating persisters (e.g., a green fluorescent protein while using dyes with suitable colors for flow cytometry). These technologies can provide in-depth insights into bacterial tolerance and resistance during antibiotic therapy when combined with traditional approaches to characterize resistant bacterial subpopulations on antibiotic-containing agar plates.

Key outcomes and integration into translational QSP models

High-throughput confocal microscopy and flow cytometry can characterize morphology changes and thereby PBP receptor binding patterns in MDR bacterial strains. Such MDR strains are more difficult to study by PBP binding assays due to extensive β-lactamase activity. Confocal microscopy and flow cytometry are highly complementary when used together with OM permeability and receptor binding assays. Moreover, high-throughput confocal microscopy and flow cytometry can generate mechanistic insights for antibiotic action and synergy for multiple antibiotic classes. We found these latest techniques to be considerably more sensitive than static in vitro time-kill studies for identifying antibiotic synergy and for visually confirming the type and time-course of bacterial damage. Although future studies will have to evaluate different approaches of implementing microscopy and flow cytometry data into mechanism-based PK/PD and QSP models, these technologies provide valuable mechanistic insights for optimizing antibiotic mono and combination therapies and for drug discovery.

INTRACELLULAR ACCUMULATION AND RECEPTOR BINDING ASSAYS FOR CYTOSOLIC TARGETS

Background

The Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA®) has rapidly become a powerful chemical biology tool for studying intracellular ligand-protein interactions in eukaryotic systems.105-107 Adaptation of this technique to protozoal and bacterial systems has proven to be a uniquely important way to assess small molecule permeability and target affinity in an intact cell system.108,109 The CETSA® is a measure of a small molecule’s ability to stabilize its protein target from heat-induced degradation. This can be quantified through various techniques including Wester blot, protein mass spectrometry, and luminescence readouts.110 Positive activity in this assay, through target engagement, requires a compound that is both permeable enough to accumulate in cytoplasm and bind its target with sufficient affinity to protect it from heat degradation.

Performing CETSA® in efflux deficient, or otherwise membrane integrity compromised cells, and cell lysates (i.e., when the permeability barrier is absent) can elucidate the role of compound permeability in target engagement. Comparison of CETSA® melting temperature among mutant or lysed cells enables early preclinical assessment of the ability of novel antimicrobial compounds to penetrate the cell membranes, avoid efflux, and directly engage the target.111 This serves as an important tool in understanding conflicting data from whole cell susceptibility testing and biochemical target inhibition assays.

Assays

Target engagement is measured as the shift of the denaturation temperature of a protein inside bacterial cells, upon exposure to small molecule inhibitors that stabilize the protein to heat. To accomplish this, the cells are lysed after the heat treatment and the soluble protein target is quantified via Western blot or proteomics. There is a lack of commercially available primary antibodies against bacterial drug targets. We have found that cloning a FLAG tag into the N-terminal sequences of the constitutively expressed gene of interest is an expeditious approach for achieving a Western blot readout.112,113 Once transformed into the bacteria of interest, cultures with the tagged target are grown and subsequently exposed to the studied compound. Drug-exposed cells are aliquoted and individual samples heated over a temperature gradient that has been optimized for each specific target. Once heated, all denatured, insoluble proteins are removed from the soluble, chemically protected protein via centrifugation. Remaining soluble, FLAG-tagged proteins are detected and quantified from lysed cells by Western blot with commercially available α-FLAG antibodies. The intensities of the Western blot bands are normalized to the lowest temperature and CETSA® curves are reported as “Relative Band Intensity (%)” vs. “Temperature (°C).” The melting temperature is defined as the temperature that yields a 50% reduction in detected protein. In addition to the standard temperature gradient, isothermal dose response (ITDR) CETSA® can inform about the dose response for target engagement. For ITDR CETSA®, cells are treated with varying concentrations of compound and exposed to a single denaturing temperature.

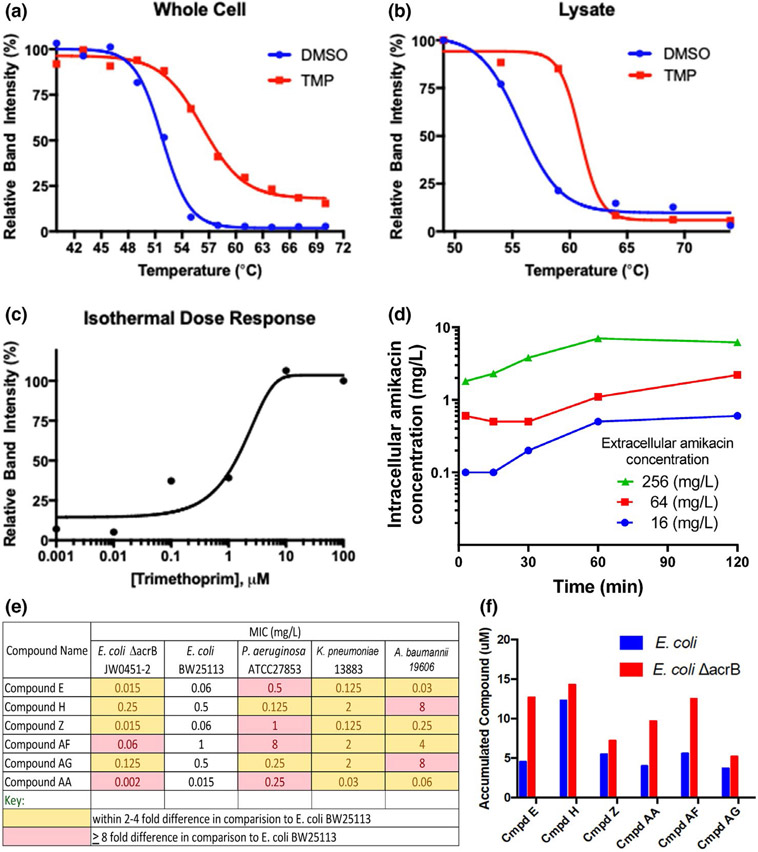

As proof-of-concept studies, we have successfully applied this approach in intact E. coli to characterize binding of the antifolate trimethoprim (TMP) to its target, dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR; Figure 6a,b, unpublished data). The DHFR CETSA® curves (Figure 6a) for cultures treated with TMP and dimethyl sulfoxide highlighted the ability of TMP to protect DHFR from heat degradation through DHFR engagement resulting in an ~ 5°C shift in melting temperature. Similarly, CETSA® performed in lysed cells, which removes the permeability barrier (Figure 6b), yielded an ~ 5°C shift in melting temperature compared with the dimethyl sulfoxide control, due to TMP being freely permeable. Finally, the ITDR (Figure 6c) indicated that cells needed exposures of ~ 10 μ M for optimal engagement. When the CETSA® results were compared with biochemical target affinity and intracellular accumulation data obtained via mass spectrometry, a holistic picture of the primary factors that determine intracellular inhibitor—target occupancy can be derived and used for ligand optimization.

Figure 6.

Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA®) curves of the folic acid pathway target dihydrofolate reductase for trimethoprim (TMP). (a) Whole cell CETSA® curves in Escherichia coli. (b) CETSA® curve from E. coli lysate. (c) Isothermal dose response for TMP at 50°C. (d) Direct quantification of intracellular amikacin concentrations in a 16S rRNA methyltransferase (i.e., an ARM) expressing strain of P. aeruginosa that was highly resistant to amikacin. The intracellular amikacin concentrations reached a plateau after ~ 60 minutes at ~ 2 to 4% of the extracellular concentration. (e) Minimal inhibitory concentration (MICs) of six compounds from Bugworks against ATCC strains of four Gram-negative pathogens. (f) Intra-cellular accumulation of these six broad-spectrum antibacterial compounds in a wild-type and its isogenic, efflux-pump knockout (ΔacrB) E. coli strain. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

Future considerations

Expanding the use of CETSA® will prove to be a highly valuable tool for antibiotic discovery. For example, adapting bacterial CETSA® for high-throughput screening campaigns, as has been reported in eukaryotic systems, would be an important way to identify target-specific chemical matter. Such compounds already satisfy some major pitfalls in Gram-negative drug discovery, including permeability and target affinity.

Key outcomes and integration into drug discovery

Bacterial CETSA® is an underutilized tool to assess protein-ligand engagement during drug discovery. The CETSA® compound profiling combined with biophysical techniques, including surface plasmon resonance to quantify ligand affinity, and whole cell accumulation studies provides a powerful look into the effects of these individual contributors toward overall target engagement. Performing CETSA® in efflux deficient and OM compromised strains allows one to elucidate the mechanisms that contribute to the target site penetration of small molecules. This is particularly valuable for quantification of inhibitors and potentiators that do not result in whole cell activity on their own.

Direct quantification of intracellular antibiotic concentrations

We further implemented an LC-MS/MS based whole cell accumulation assay similar to the assay published by Hergenrother’s group114 in order to determine intracellular antibiotic concentrations. As proof-of-concept, we have determined the time-course of intracellular amikacin concentrations (Figure 6d) in a highly aminoglycoside-resistant P. aeruginosa strain. This strain had a modified target site that greatly diminishes binding of the aminoglycoside. This allows one to study accumulation without bacterial killing. The intracellular amikacin concentrations reached a plateau after ~ 60 minutes at ~ 2–4% of the extracellular concentration. Such intracellular concentration data can be implemented into QSP models to better describe target site penetration and the impact of different resistance mechanisms.

Intracellular accumulation assay supporting drug discovery and development

Recently, Bugworks discovered broad-spectrum antibacterial compounds that target DNA Gyrase and Topo IV. These compounds were primarily designed to bypass efflux liability by reducing the binding affinity to the AcrB efflux pump transporter. The IC50s to GyrA and Topo IV were within a 2–4-fold range (results not shown). However, the MIC ranges were much larger (Figure 6e). Four compounds showed a 2–4-fold residual efflux liability as inferred from the ratio of the MICs between the wild type and the corresponding ArcB transporter-deficient E. coli strains (Figure 6e). For the remaining two compounds, this liability was eightfold or greater. To further delineate the differences in MICs, intracellular accumulation was studied (Figure 6f). Use of the AcrB deficient strain allowed us to assess the role of intracellular accumulation in an efflux devoid environment. Early results (Figure 6f) indicated that the MIC was a net of permeability and efflux as seen with the intracellular concentration in the isogenic wild-type and transporter-deficient strains. Further studies are underway to separate the contribution of these two factors to support the discovery of more potent compounds, especially against P. aeruginosa.

NEXT GENERATION QUANTITATIVE AND SYSTEMS PHARMACOLOGY MODELS: IMPLEMENTING MASS BALANCE, PENETRATION, AND RECEPTOR BINDING AT THE BACTERIAL TARGET SITE

Current generation PK/PD models for antibiotics specify the drug effect almost always as a function of the extracellular drug concentration with or without a short, empiric time-delay. Due to a limited number of mechanistic assays, insights at the molecular level were less commonly used to underpin antimicrobial PK/PD models.

Innovations

Antibiotic penetration from the extracellular space to the bacterial target site and subsequent receptor binding have not been measured and were thus not incorporated for most models, in part, because the rate of bacterial target site penetration was unknown in the studied pathogens.115,116 We are not aware of any published antibacterial PK/PD model that implemented mass balance equations at the bacterial target site (Figure 7a). The assay platform proposed here allows one to determine the fraction of bound PBPs in intact bacteria. The bound PBPs can then be correlated with morphology changes identified by automated microscopy and flow cytometry. Thereby, these technologies can provide insights on which PBPs are (extensively) bound over time. This reverse engineering approach allows one to integrate experimental data on the time-course of PBP binding and morphology changes in intact bacteria into translational QSP models. These models can be further enhanced by implementing mass balance equations at the bacterial target site.

Figure 7.

First mass-balance based model for the bacterial target site penetration of a β-lactam (here penicillin G) and binding to five different penicillin-binding protein (PBP) enzymes (PBP1a, PBP1b, PBP2a, PBP2b, and PBP3). (a) Target site penetration and binding model: This dataset was published by Williamson & Tomasz who characterized the intact-cell PBP binding of radioactively labeled penicillin G in an autolytic-deficient Streptococcus pneumoniae strain. Each cell contained approximately 20,000 PBP enzymes in total. The bacterial target site penetration of penicillin was modeled as a first-order process. Each PBP existed in a free (e.g., PBP1af) and in a bound form (e.g., PBP1ab). This model was the first to implement mass-balance equations at the bacterial target site. Penicillin molecules could be “consumed” due to their covalent bond to one of the different PBP target receptors. This reaction was modeled as a second-order process. PBP binding caused inhibition of peptidoglycan and protein synthesis and of bacterial replication. (b) Curve fits for the number of bound PBP molecules per cell for five different PBPs in intact S. pneumoniae based on this mass-balance binding model. (c1) Hypothetical simulation of the number of penicillin molecules at the bacterial target site of one S. pneumoniae cell as a function of different permeability coefficients. This scenario of slower outer membrane penetration is more relevant for Gram-negative bacteria that have an outer membrane, which presents a significant penetration barrier. However, Gram-positive bacteria also may have nonmembrane-related penetration barriers, such as a thick cell wall or a capsule. For rapidly penetrating β-lactams (500 nm/second), the bacterial target site concentration quickly approached the extracellular drug concentration. For slowly penetrating β-lactams (10 nm/second), this rise was much more slowly and the bacterial target site concentration was considerably lower than the extracellular β-lactam concentration, because the β-lactam molecules were “consumed by” binding to PBPs. (c2) Simulated number of β-lactam molecules entering the bacterial target site as a function of different permeability coefficients. (d) Prospective validation of the inhibition of peptidoglycan synthesis and cell growth using a second dataset (not used for model development) provided by Williamson & Tomasz.

Mass balance QSP model

We have developed the first such model based on a published PBP binding dataset from Williamson & Tomasz.92 This study characterized the time-course of binding for five different PBPs by radiolabeled penicillin G in a lytic-deficient strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae. This provided unique insights into the rate of PBP saturation and the subsequent inhibition of peptidoglycan and protein synthesis, as well as inhibition of bacterial growth. Our new bacterial target site penetration and PBP binding model accurately characterized the time-course of PBP binding (Figure 7b). As expected, the permeability coefficient substantially impacted the number of unbound penicillin molecules per cell. In a hypothetical simulation, rapidly penetrating β-lactams (500 and 100 nm/s) achieved the extracellular concentration within 10 to 40 minutes, whereas a hypothetical, slowly penetrating β-lactam (10 nm/s) had on average less than one penicillin molecule per cell (Figure 7c). Each S. pneumoniae cell has ~ 20,000 PBP target receptors in total. Therefore, it is essential for > 20,000 β-lactam molecules to enter within one bacterial generation time (i.e., about 40,000 molecules per hour) to overwhelm the PBP targets (Figure 7c). This model accurately predicted the downstream inhibition of peptidoglycan synthesis and bacterial growth inhibition in an external validation using the second dataset provided by Williamson and Tomasz92 (Figure 7d).

Future considerations

The proposed QSP modeling approach presents the first model to include the bacterial target site penetration and binding to multiple different PBPs in any bacterial pathogen. This approach is transferable to other pathogens and can integrate mechanistic experimental data. Hence, QSP modeling is excellently suited to rationally optimize antibiotic candidates and dosage regimens for patients.

The QSP modeling approach can be thoroughly informed by different levels of experimental data on the mechanisms of drug action and resistance. This modeling strategy incorporates bacterial target site penetration and describes drug action as a function of bound target receptors. Therefore, it is straightforward to describe the effects elicited by binding of one or multiple drug(s) to multiple receptors in intact bacteria. Thereby, this strategy is ideally suited to rationally optimize synergistic antibiotic combination therapies against MDR bacterial pathogens.

To account for between patient variability in PK, Monte Carlo simulations have been leveraged to predict the probability of successful treatment outcomes in patients for antibiotic monotherapy and combinations.19,117 These Monte Carlo simulations accounted for the population PK in critically ill patients44,45,118 and their results were prospectively validated to confirm extensive bacterial killing and resistance prevention.19,48,119 Implementing mass-balance equations for bacterial target site penetration and receptor binding presents the next step to further enhance the mechanistic foundation of these models. Likewise, this approach is ready to support drug development by simultaneously optimizing antibiotic target site penetration, receptor binding, and avoiding or saturating resistance mechanisms.

DISCUSSION

In the face of the dire shortage of effective antibiotics, novel assays and tools to gain mechanistic insights based on cutting-edge technologies hold excellent promise to create antibiotics with enhanced bacterial target site penetration and receptor binding. This seeks to reinvigorate the antibiotic pipeline and will further allow us to rationally optimize combinations of available antibiotics as a more immediate and tangible solution to tackle this global health crisis.

The proposed novel assay platform leverages latest technologies to better understand target site penetration and receptor binding for antibiotics with periplasmic or cytosolic targets. These novel assays provide complementary insights and should be used in tandem with established approaches, such as MIC testing, static, and dynamic in vitro, as well as murine infection models.9 Some assays are ideally suited for resistance-deprived strains, whereas others require (or benefit from) studying MDR strains (Table 1). The PBP binding studies using lysed bacteria are best performed in strains that lack β-lactamases. The intact cell binding assay can determine the time-course of PBP binding in both resistance-deprived and MDR strains. When intact cell PBP binding studies are combined with confocal microscopy and flow cytometry, one can reverse-engineer the achieved PBP occupancy patterns in MDR strains. This provides an efficient path for characterizing intact cell PBP binding in all strains via flow cytometry and microscopy. In future studies, the new assay platform can provide in-depth mechanistic insights when using isogenic strains with different OM porins, efflux pumps, and β-lactamases (see Figure 6f for an example).

Table 1.

Comparison of throughput and applicability of the novel assays

| Assay | Assay throughput | Requirement for strains |

Best suited for | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OM permeability | ||||

| For β-lactams | Excellent with multiplex Good in discrete mode (i.e., 1 drug at a time) Lower if extracellular β-lactamase activity is present |

Strain has to produce β-lactamases that hydrolyze the studied β-lactams | Multidrug-resistant bacteria with no extracellular β-lactamase activity | Earliest sampling time ~ 1 minute. Assay can be performed at multiple bacterial densities Improved LC-MS/MS technology greatly beneficial |

| For BLIs | Good | Strain has to produce β-lactamases that hydrolyze the studied β-lactams | BLI should inhibit all β-lactamases in the studied strain | Ideally suited when studying a rapidly penetrating victim β-lactam; can assess penetration half-lives of 30 seconds to 1 minute |

| PBP binding | ||||

| PBP binding via Bocillin™ FL in lysed bacteria | Excellent (depends on pathogen) | Applicable to large variety of strains | Strain without extensive (ideally no or limited) β-lactamase activity | β-lactamase activity has to be carefully considered, if present Can determine time-course of PBP binding |

| PBP binding via Bocillin™ FL in intact bacteria | Low to intermediate (high workload) (depends on pathogen) | Applicable to large variety of strains | Strain without extensive (ideally no or limited) β-lactamase activity | Can assess the time-course of PBP binding in the presence of all PBPs Accounts for all resistance mechanisms that affect PBP binding |

| Fluorescence anisotropy kinetic binding assay | Good – excellent | Applicable to large variety of strains | PBPs that can be efficiently expressed (e.g., in Escherichia coli) and purified | Provides in-depth insights into binding rate constants “Clean” background due to the use of purified PBPs Synergizes with the above PBP binding assays |

| High-throughput automated confocal microscopy | Excellent (< 1 minute per sample for analysis) | Applicable to large variety of strains (including MDR strains) | Widely applicable | < 1 minute per sample analysis 5–15 minutes for staining Complements flow cytometry Strains with fluorescent proteins yield further insights |

| Flow cytometry | Excellent (< 1 minute per sample for analysis) | Applicable to large variety of strains (including MDR strains) | Widely applicable | < 1 minute per sample analysis; 5–15 minutes for staining strains with fluorescent proteins yield further insights Future application of latest flow cytometers with sorting |

| Intracellular accumulation and receptor binding assays | Low to excellent, depending on the assay and future optimization for implementation in screening platforms | Applicable to a variety of strains (including MDR strains) | For aminoglycoside assays: highly resistant (16S) strains without intracellular drug modifying enzymes (that are common for aminoglycosides) For CESTA: defined molecular targets |

Can provide quantitative data on intracellular receptor occupancy (CETSA assay) Latest LC-MS/MS technologies greatly beneficial due to improved sensitivity |

BLI, β-lactamase inhibitors; CESTA, Cellular Thermal Shift Assay; LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry; MDR, multidrug-resistant; OM, outer membrane; PBP, penicillin-binding protein.

There is a delicate interplay among penetration, efflux, periplasmic, or intracellular drug-modifying enzymes, and target receptor binding. The complexity of this scenario is illustrated for β-lactam antibiotics below. The same general principles apply, however, to antibiotics with periplasmic and cytosolic targets. For β-lactams to yield bacterial killing, these molecules have to bind to their target PBPs (Figure 1). This is a function of the β-lactam concentration in periplasm. Several factors operate in concert to determine the bacterial target site concentration. The rate of OM penetration is a major factor influencing the penetration of β-lactams into periplasm. The OM permeability of β-lactams is greatly affected by the chemical structure of the β-lactam, but also the presence and expression of OM porin channels (Figure 1). Our initial studies suggested that there may be considerable strain-to-strain variability at least for some β-lactams.67 Certain porins are somewhat specialized for groups of drugs. As an example, carbapenems use OprD2 in P. aeruginosa. This porin has a specific structure that recognizes carbapenems. Downregulating the expression of OprD2 decreases the rate of penetration.

Once a β-lactam has gained entry into the periplasm, it must bind to its PBP targets. However, the organism can deploy β-lactamases to inactivate β-lactam molecules, and may additionally upregulate the expression of efflux pump(s).26 Both of these factors will remove active (i.e., non-ring-opened) β-lactam molecules from the periplasm and thereby decrease the target site concentration.

Both β-lactamases and efflux pumps follow Michaelis-Menten kinetics and may be saturated, if the β-lactam concentration in periplasm is high. A high rate of penetration increases the periplasmic drug concentration (Figure 1) and therefore the likelihood of saturation. Ultimately, the drug has a greater chance of binding PBPs and killing the organism, because either the β-lactamase can no longer hydrolyze more β-lactam molecules or the efflux pump cannot extrude more drug. By downregulating porins, the penetration slows and both β-lactamases and efflux pumps become increasingly more important, because there are fewer inflowing β-lactam molecules. There is extensive “synergy” among these resistance mechanisms, which are operating in concert. The impact of efflux pump(s) and β-lactamases tends to be greatest in pathogens with slow OM permeability (e.g., P. aeruginosa60-65 vs. K. pneumoniae67).

To optimize the probability of successful therapy, several strategies can be pursued. One approach is to utilize a BLI to prevent inactivation of β-lactams in periplasm.120,121 Another approach is to administer an inhibitor of protein synthesis that will impair the expression of β-lactamases122 and potentially also of efflux pumps. Further, one may alter the permeability of the bacterial OM by administering a polymyxin or an aminoglycoside.34,35,47,49,54,118 Either of these approaches likely increases the periplasmic concentration of the β-lactam and thus yields synergy.19,44

Once a sufficient β-lactam concentration is achieved in periplasm, the extent of PBP inactivation increases. The β-lactams differ, however, considerably in their binding preferences for various PBP targets.75,90 We and others79,123 found that achieving specific PBP occupancy patterns has an impact on the rate of killing in the four Gram-negative pathogens (Figure 1; unpublished data). Achieving optimal PBP occupancy patterns often greatly benefits from combinations of two β-lactams. Given the excellent safety profiles of β-lactams relative to the drug-related toxicity of polymyxins and aminoglycosides, rationally chosen combination therapy may be an optimal approach to successfully treat serious infections.58

The new assay platform proposed here provides a path forward for identifying optimal antibiotic combinations. When two β-lactams are combined in double β-lactam therapy,58 the ability to identify the most avid PBP binders among different β-lactams both in lysed and intact cells and via the kinetic binding assay directly allows hypothesis generation for best combinations.90,101 Linking PBP occupancy patterns to bacterial killing is the step that identifies the most promising two drug combinations. Insights into the OM penetration rate of β-lactams and BLIs further supports this optimization.

Some organisms will harbor very broad substrate β-lactamases. For these pathogens and isolates, it may be necessary to administer a BLI, such as a diazabicyclooctane series inhibitor (e.g., avibactam or durlobactam121) or a novel cyclic boronate inhibitor. The proposed new assays allow one to determine the rate of BLI penetration in the targeted pathogens.

Some bacterial isolates are pan-drug resistant. Here, one may need to administer optimal double β-lactam therapy plus a BLI and additionally increase the OM permeability by an aminoglycoside or a polymyxin. Permeabilizing the OM can be quantified by our novel assays (unpublished data). Therefore, this innovative assay platform allows quantitative evaluation of how successful these three-drug and four-drug combination therapies will be by quantifying the rate and extent of PBP occupancy. These assays also allow deconvolution of the importance of each of the interventions (double β-lactam, adding a BLI, or adding an aminoglycoside or a polymyxin). Thereby, this platform provides valuable insights for dynamic in vitro and animal infection models, and ultimately for the translation to clinical trials.9 This in vitro and translational modeling approach19,33 has been shown to excellently predict the exposure targets required for efficacy of ceftazidime monotherapy against P. aeruginosa in animals and patients.9-12 This translational approach will be further enhanced by the substantially better mechanistic understanding of antibiotic action and synergy supported by the new assay platform. This strategy holds great promise to streamline and de-risk clinical drug development.

It is our hope that the assays and translational strategies in this tutorial and other novel assays provide important tools for future drug discovery and development as well as the optimization of antibiotic therapies based on available drugs. We further seek to stimulate the development, implementation and further refinement of assays that can quantify bacterial target site penetration and whole-cell receptor binding. Future research is warranted to characterize the relative contributions of permeability, porins, efflux, and β-lactamases. This will fundamentally support elucidating the molecular determinants of bacterial target site penetration and receptor binding in different bacterial pathogens for available and new antibiotic classes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Mr. Ingo Menhard (Mediendesign) for support with professional graphics design.

FUNDING

This study was supported by awards R01AI136803 (to J.B.B., B.M., A.C., K.B.B., H.P.S., R.A.B., A.L., R.L., and G.L.D.), R01AI130185 (to J.B.B., J.D.B., R.A.B., A.L., and G.L.D.), R01AI148560 (to B.T.T., J.B.B., A.L., and G.L.D.), as well as awards R01AI100560, R01AI063517, and R01AI072219 (to R.A.B.) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Work was supported in part by ALSAC, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

N.B. and V.B. are employees of BUGWORKS Research India Pvt. Ltd. All other authors declared no competing interests for this work.

DISCLAIMER

The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institutes of Health, or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Munoz-Price LS et al. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet. Infect. Dis 13, 785–796 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redfield RR CDC. Antibiotic resistant threats in the United States. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; (2019) <https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf 10.15620/cdc:82532>. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker B et al. Environment. Looming global-scale failures and missing institutions. Science 325, 1345–1346 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper MA & Shlaes D Fix the antibiotics pipeline. Nature 472, 32 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) et al. Combating antimicrobial resistance: policy recommendations to save lives. Clin. Infect. Dis 52(Suppl 5), S397–S428 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talbot GH et al. The Infectious Diseases Society of America’s 10 x ’20 Initiative (10 new systemic antibacterial agents US Food and Drug Administration approved by 2020): Is 20 x ’20 a possibility? Clin. Infect. Dis 69, 1–11 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Appelbaum PC 2012 and beyond: potential for the start of a second pre-antibiotic era? J. Antimicrob. Chemother 67, 2062–2068 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silver LL Challenges of antibacterial discovery. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 24, 71–109 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bulitta JB et al. Generating robust and informative nonclinical in vitro and in vivo bacterial infection model efficacy data to support translation to humans. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother 63, e02307–18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drusano GL Antimicrobial pharmacodynamics: critical interactions of ‘bug and drug’. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2, 289–300 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craig WA Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin. Infect. Dis 26, 1–10 (1998), quiz 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ambrose PG et al. Pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of antimicrobial therapy: it’s not just for mice anymore. Clin. Infect. Dis 44, 79–86 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Craig WA & Ebert SC Killing and regrowth of bacteria in vitro: a review. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. Suppl 74, 63–70 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eagle H, Fleischman R & Musselman AD The effective concentrations of penicillin in vitro and in vivo for streptococci, pneumococci, and Treponema pallidum. J. Bacteriol 59, 625–643 (1950). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerber AU, Craig WA, Brugger HP, Feller C, Vastola AP & Brandel J Impact of dosing intervals on activity of gentamicin and ticarcillin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in granulocytopenic mice. J. Infect. Dis 147, 910–917 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leggett JE et al. Comparative antibiotic dose-effect relations at several dosing intervals in murine pneumonitis and thigh-infection models. J. Infect. Dis 159, 281–292 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]