Abstract

Using broth conjugation, we found that 19 of 29 (66%) oxytetracycline (OT)-resistant isolates of Aeromonas salmonicida transferred the OT resistance phenotype to Escherichia coli. The OT resistance phenotype was encoded by high-molecular-weight R-plasmids that were capable of transferring OT resistance to both environmental and clinical isolates of Aeromonas spp. The molecular basis for antibiotic resistance in OT-resistant isolates of A. salmonicida was determined. The OT resistance determinant from one plasmid (pASOT) of A. salmonicida was cloned and used in Southern blotting and hybridization experiments as a probe. The determinant was identified on a 5.4-kb EcoRI fragment on R-plasmids from the 19 OT-resistant isolates of A. salmonicida. Hybridization with plasmids encoding the five classes (classes A to E) of OT resistance determinants demonstrated that the OT resistance plasmids of the 19 A. salmonicida isolates carried the class A resistance determinant. Analysis of data generated from restriction enzyme digests showed that the OT resistance plasmids were not identical; three profiles were characterized, two of which showed a high degree of homology.

Aeromonas salmonicida is the causative agent of furunculosis, an economically important disease of salmonids (5). Control of this disease in aquaculture may be by prophylaxis (i.e., vaccination) (11) or by chemotherapy with a wide variety of antimicrobial compounds (5). Initially when sulfonamides were administered as food additives, they were successful (12). Subsequently, the usefulness of oxytetracycline (OT) was reported (29), and this antibiotic is still used extensively for control of furunculosis (5, 28). However, continued and widespread use of antibiotics has led to the development of resistant strains (3, 8, 15, 23). Moreover, plasmids encoding antibiotic resistance (R-plasmids) have been isolated from A. salmonicida (2, 15, 26, 27). A second generation of 4-quinolones–fluoroquinolones, notably enrofloxacin and sarofloxacin, effectively inhibits the pathogen and offers promise for the future since plasmid-encoded resistance to these compounds has not been described (7, 14, 19). However, mutational resistance to this class of compounds can develop in A. salmonicida (8, 21, 22, 32).

As noted previously (28), it is difficult to make any definite conclusions about the impact of OT usage in aquaculture because of the methodological differences described in the literature. Transferable R-plasmids encoding resistance to tetracycline in A. salmonicida were described in 1971 (2, 31); subsequently, studies indicated that the frequency of OT-resistant strains of A. salmonicida was increasing. In a survey of 444 A. salmonicida isolates collected from Scottish salmon farms during 1988 to 1991, 53% of the isolates were resistant to OT (23). Using a random subsample of these isolates, researchers determined that 27% contained R-plasmids which could be transferred to Escherichia coli K-12 by conjugation (15), although no information concerning the molecular basis for the resistance was provided. Whereas there is no doubt that the results of such studies have value, it is necessary to clarify the situation with regard to the spread of R-plasmids encoding OT resistance within A. salmonicida populations. Only through precise molecular characterization of the genes encoding OT resistance and the plasmids that carry these resistance determinants will it become clear if aquaculture is facing a real threat from the use of antibiotics. To address this issue, a collection of OT-resistant isolates was used in experiments that examined the molecular basis for OT resistance and the potential environmental impact of the R-plasmids of these isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Table 1 shows the OT-resistant strains of A. salmonicida used, including three isolates which were obtained from Canada, two isolates which were obtained from the United States, one isolate which was obtained from Norway, and 24 isolates which were obtained from Scotland. Table 2 lists environmental isolates and type cultures of Aeromonas spp. OT-sensitive strains of A. salmonicida are shown in Table 3. E. coli XL-1 Blue MR and HB101 were used in conjugation and transformation experiments and for maintenance, amplification, and preparation of plasmid DNA. Table 4 lists the plasmids that contain OT resistance determinant classes A to E.

TABLE 1.

OT-resistant strains of A. salmonicida used in this work

| Strain(s) | Year of isolation | Origina | Sourceb |

|---|---|---|---|

| MT0048 | 1982 | Scotland | SOAEFD |

| MT0320, MT0321, MT0336 | 1986 | Scotland | SOAEFD |

| MT0350, MT0404 | 1987 | Scotland | SOAEFD |

| MT0464 | 1988 | Scotland | SOAEFD |

| MT0900, MT0903, MT0904, MT906, MT0918 | 1990 | Scotland | SOAEFD |

| MT1401, MT1402, MT1406, MT1407, MT1410, MT1413, MT1425, MT1427, MT1431, MT1432, MT1434 | 1993 | Scotland | SOAEFD |

| 86442, 90644, Q203 | Unknown | Canada | DIFMR |

| 89547, 90617 | Unknown | United States | DIFMR |

| Banks | 1990 | Scotland | This laboratory |

| 718c | Unknown | Norway | R.-A. Sandaad |

Most of the Scottish isolates were recovered from clinical outbreaks of furunculosis in Atlantic salmon; the only exception was MT1413, which was recovered from brown trout (Salmo trutta).

SOAEFD, Scottish Office Agricultural, Environment and Fisheries Department, Marine Laboratory, Aberdeen, Scotland; DIFMR: Danish Institute for Fisheries and Marine Research, Fish Disease Laboratory, Frederiksberg, Denmark.

Strain 718 contains plasmid pRAS1.

Department of Microbiology, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway.

TABLE 2.

Environmental isolates and type cultures of Aeromonas spp. used in this worka

| Species or subspecies | Strainb | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Aeromonas caviae | LMG3775 | Epizootic, guinea pig |

| A. eucrenophila | LMG3774 | Freshwater fish |

| A. hydrophila | LMG3764 | Feces |

| A. hydrophila | UL271 | Rainbow trout skin |

| A. hydrophila | UL77 | Brown trout muscle |

| A. hydrophila | UL16 | Brown trout gut |

| A. hydrophila | UL21 | Brown trout abdominal cavity |

| A. hydrophila | UL29 | Brown trout abdominal cavity |

| A. hydrophila | UL48 | River water |

| A. hydrophila | UL92 | Brown trout muscle |

| A. hydrophila | UL96 | Brown trout muscle |

| A. hydrophila | UL154 | Brown trout gill |

| A. hydrophila | UL156 | Brown trout muscle |

| A. hydrophila | UL157 | Brown trout skin |

| A. hydrophila | UL167 | Brown trout abdominal cavity |

| A. hydrophila | UL169 | Brown trout abdominal cavity |

| A. hydrophila | UL176 | Brown trout skin |

| A. hydrophila | UL233 | Fish farm effluent |

| A. hydrophila | UL181 | Brown trout skin |

| A. hydrophila | UL186 | Brown trout abdominal cavity |

| A. hydrophila | UL215 | Fish farm water |

| A. hydrophila | UL250 | Fish farm water |

| A. hydrophila | UL501 | Pike gills |

| A. hydrophila | UL226 | Fish farm water |

| A. hydrophila | UL151 | Brown trout gill |

| A. hydrophila | ULP2 | Brown trout muscle |

| A. jandaei | LMG12221 | Feces |

| A. media | LMG9073 | Water |

| A. salmonicida subsp. masoucida | LMG3782 | |

| A. schubertii | LMG9074 | Human abscess |

| A. sobria | LMG3783 | Fish |

| A. sobria | UL510 | Pike skin |

| A. trota | LMG12223 | Feces, India |

| A. veronii | LMG9075 | Near-drowning victim |

Most Aeromonas spp. strains were resistant to ampicillin (100 μg ml−1); the only exception was A. trota LMG12223.

LMG, Laboratorium voor Microbiologie, Universiteit Gent, Ghent, Belgium; UL, Universídad de León, León, Spain.

TABLE 3.

OT-sensitive strains of A. salmonicida used in this work

| Strain(s) | Source | Antibiotic resistancea |

|---|---|---|

| S001, S24, S194, AS20, Gorstein, Linne | Our laboratory | NAr |

| NG, 248/91, 94, 95, 96, MB, AS14, 108 | Our laboratory | Smr |

| L.L. | Atlantic salmon, Scotland | NAr |

| 107 | Our laboratory | NAr Smr |

NAr, resistant to nalidixic acid (10 μg ml−1); Smr resistant to streptomycin (10 μg ml−1).

TABLE 4.

Plasmids containing OT resistance determinant classes A to E

| OT resistance determinant class | Host E. coli straina | Restriction endonuclease fragment containing the OT resistance determinant |

|---|---|---|

| A | JM83 | 750-bp SmaI fragment of pSL18 in pUC18 |

| B | HB101 | 1.275-bp HincII fragment of pRT11 in pRT11 |

| C | DO-7 | 929-bp BstNI fragment of pBR322 in pBR322 |

| D | C600 | 3,050-bp HindIII fragment of pSL106 in pACYC177 |

| E | HB101 | 2,500-bp ClaI-PvuI fragment of pSL1504 in pACYC177 |

E. coli strains containing the plasmids were provided by R.-A. Sandaa (Department of Microbiology, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway) and S. B. Levy (Department of Molecular Biology and Microbiology, Tufts University, Boston, Mass.).

For routine propagation of Aeromonas strains, plates of brain heart infusion agar (BHIA) (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) were incubated at 15 to 25°C. Strains were subcultured every 3 to 5 days. For long-term storage, most bacterial strains were stored at −70°C in brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid) supplemented with 15% (wt/vol) glycerol. E. coli was stored at −70°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (Oxoid) containing 15% (wt/vol) glycerol. E. coli transformants were incubated overnight at 37°C on slants of LB agar medium containing 1.2% (wt/vol) agar with selection (15 μg of tetracycline per ml or 100 μg of ampicillin per ml, as appropriate) and were subsequently stored at 4°C. Transformants were subcultured every 3 to 4 weeks; stock cultures were also stored at −70°C in LB medium containing 15% (wt/vol) glycerol (with selection). The antibiotic resistance spectra of E. coli strains and transformants were determined by using multidisks (Mast Diagnostics, Reinfield, Germany) on BHIA.

DNA manipulations.

Restriction endonuclease digestion, transformation of E. coli, agarose gel electrophoresis, cloning, and ligation of DNA fragments were performed by using standard methods (25). Preparation of plasmid DNA from E. coli involved growing transformants or transconjugants containing R-plasmids overnight at 37°C in 5-ml volumes of LB medium with selection. The cells were pelleted by centrifugation (2,000 × g, 4°C) for 1 to 2 min, and plasmid DNA was prepared by using Wizard plasmid mini or midi preparation kits (Promega, Southampton, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The methods of Kado and Liu (16) and Hiney et al. (13) were used to prepare A. salmonicida plasmid and total DNA, respectively. Plasmid preparations which required further purification were processed by using the Wizard DNA Clean-Up System (Promega). DNA samples were stored at −20°C until required.

Construction of DIG-labeled probes.

Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probes were prepared by PCR amplification. The templates used were a 1.2-kb Sau3A fragment (which contained a sequence encoding OT resistance) from the OT resistance plasmid of A. salmonicida MT1407 cloned in pUC19 and the class A OT resistance determinant in pUC18 (purified from E. coli JM83). For the PCR we used extended versions of the M13 universal sequencing primer (5′-GTAAAACGACGGCCAGT-3′) and reverse sequencing primer (5′-AACAGCTATGACCATG-3′). Each reaction mixture (100 μl) contained the following components: 1 ng of template DNA, 10 μl of 10-fold-concentrated Taq DNA polymerase buffer (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), 0.2 mM dATP, 0.2 mM dCTP, 0.2 mM dGTP, 0.2 mM dTTP, 50 μM DIG-11-dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim), and each primer at a concentration of 1 μM. The reaction mixture was mixed, briefly centrifuged, and overlaid with 100 μl of light mineral oil (Sigma, Poole, United Kingdom). After denaturation of the reaction mixture at 94°C for 10 min, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim) was added. The PCR was then carried out by using the following program: 2 min at 94°C, 2 min at 55°C, and 3 min at 72°C for 35 cycles. A final extension step consisting of 10 min at 72°C completed the PCR, after which the layer of mineral oil was carefully removed. The DIG-labeled PCR product was used directly as a probe in hybridizations without purification.

Southern transfer and hybridization.

DNA samples (1 μg) were digested with restriction endonucleases and separated on 0.8% (wt/vol) agarose gels. Gels intended for Southern hybridization were electrophoresed with 0.01 μg of DIG-labeled λ DNA cut with HindIII (Boehringer Mannheim) as a molecular weight marker. The DNA was transferred to a nylon membrane (Stratagene, Cambridge, United Kingdom) by using a vacuum transfer apparatus (VacuGene; Pharmacia Biotech, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Following transfer, the membrane was removed from the apparatus, subjected to UV cross-linking, and briefly rinsed in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate, pH 7.5). The membrane was dried and stored at room temperature.

The 100-cm2 membrane to which the DNA was bound was placed in a 100-ml bottle containing 50 ml of prehybridization solution (Boehringer Mannheim). This bottle was incubated for at least 1 h at 62°C in a hybridization oven (model Micro 4; Hybaid, Teddington, United Kingdom). The probe DNA (5 ng per 100-cm2 membrane) was denatured just prior to use by adding distilled water to a final volume of 100 μl and then boiling the preparation for 10 min. Probe DNA was added to the solution in the bottle, and hybridization was allowed to take place overnight at 68°C. After hybridization, the membrane was washed twice for 5 min each time at room temperature with low-stringency wash solution (2× SSC containing 0.1% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate). This was followed by two washes (15 min each) at 62°C with high-stringency wash solution (0.5× SSC containing 0.1% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate). The DIG-labeled DNA was detected by an enzyme-linked immunoassay by using an anti-DIG antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase as described by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim).

Conjugation.

Broth conjugation was performed by mixing equal volumes (2 ml) of 72-h cultures grown in brain heart infusion broth at 22 or 28°C (Aeromonas species) or in LB broth at 37°C (E. coli) and then incubating the preparations for 5 h at 22°C (without shaking). Duplicate plates containing BHIA supplemented with the appropriate selective and counterselective antibiotics were inoculated with 100 μl of each conjugation mixture. The plates were incubated at 18 or 22°C (Aeromonas recipients) or at 37°C (E. coli recipients) for 2 to 5 days before they were examined for the presence of transconjugants.

MIC of antibiotics.

The MIC of antibiotics were determined for E. coli XL-1 Blue MR transformants that contained pRAS1 or R-plasmids obtained from the OT-resistant strains of A. salmonicida (Table 5). The antibiotics used for MIC determinations were streptomycin and trimethoprim. Transformants were grown in 10 ml of LB medium containing OT (30 μg ml−1) for 4 to 6 h at 37°C, and a 10−2 dilution of each culture in LB medium was prepared. Stock solutions of streptomycin and trimethoprim (50 μg ml−1 in LB medium) were used to prepare dilutions (200 μl in LB medium) containing 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.13, and 1.56 μg of each antibiotic per ml. The diluted antibiotic solutions were dispensed into duplicate wells of a 96-well plate (Nunc; Gibco BRL, Paisley, United Kingdom) before inoculation with the diluted bacterial suspension (1 μl). Wells containing LB medium without antibiotics were also inoculated in duplicate as growth controls. The plates were incubated overnight at 37°C, and the highest concentration at which growth occurred was recorded.

TABLE 5.

Restriction enzyme fragments obtained from plasmid pRAS1 and the R-plasmids from E. coli transformants 718x, MT0320x, MT0903x, MT0906x, MT1410x, MT1407x, and MT1432x

| E. coli transformant | Restriction enzyme fragments (kb)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BamHI | HindIII | SalI | EcoRI | HindIII + PvuI | BamHI + HindIII | BamHI + PvuI | |

| 718x | >23, 3.5 | >23, 0.6 | >23, 2.6, 1.7 | 15, 11, 5.4, 5.2, 4.5, 1.1, 0.9, 0.5 | >23, 3.8, 3.4, 2.1, 1.5, 1.3, 0.6 | >23, 1.7, 1.3, 0.6, 0.5 | 3.6, 2.6, 1.5, 1.1, 0.6, 0.5 |

| MT0320x | NDa | ND | ND | 18, 6.1, 5.4, 5.2, 1.3, 1.1, 1.0, 0.9 | >23, 1.5, 0.5, 0.4 | ND | >23, 1.5, 0.5, 0.4 |

| MT0903x | >23, 3.7 | >23, 3.7, 3.5, 1.9 | >23, 12, 0.6 | 15, 9.4, 6.3, 5.4, 5.2, 3.1, 1.1, 0.9, 0.5 | >23, 4.3, 3.8, 2.1, 1.5, 1.3, 0.6, 0.5 | >23, 3.6, 2.6, 1.4, 1.2, 0.5 | >23, 9.5, 2.8, 1.5, 1.1, 0.6, 0.5 |

| MT0906x | >23, 3.4 | >23, 4.3, 3.5, 1.9 | >23, 12, 0.6 | 15, 9.4, 6.3, 5.4, 5.2, 2.9, 1.1, 0.9, 0.5 | >23, 4.8, 3.8, 2.1, 1.5, 1.3 | >23, 3.6, 5.8, 1.9, 1.2, 0.5 | >23, 9.5, 2.3, 1.5, 1.1, 0.6, 0.5 |

| MT1407x | >23, 3.7 | >23, 3.7, 3.5, 1.9 | >23, 12, 0.6 | 15, 9.4, 6.3, 5.4, 5.2, 3.1, 1.1, 0.9, 0.5 | >23, 4.3, 3.8, 2.1, 1.5, 1.3, 0.6, 0.5 | >23, 3.6, 2.6, 1.4, 1.2, 0.5 | >23, 9.5, 2.8, 1.5, 1.1, 0.6, 0.5 |

| MT1410x | >23, 3.7 | >23, 3.7, 3.5, 1.9 | >23, 12, 0.6 | 15, 9.4, 6.3, 5.4, 5.2, 3.1, 1.1, 0.9, 0.5 | >23, 4.3, 3.8, 2.1, 1.5, 1.3, 0.6, 0.5 | >23, 3.6, 2.6, 1.4, 1.2, 0.5 | >23, 9.5, 2.8, 1.5, 1.1, 0.6, 0.5 |

| MT1432x | >23, 3.4 | >23, 4.3, 3.5, 1.9 | >23, 12, 0.6 | 15, 9.4, 6.3, 5.4, 5.2, 2.9, 1.1, 0.9, 0.5 | >23, 4.8, 3.8, 2.1, 1.5, 1.3 | >23, 3.6, 5.8, 1.9, 1.2, 0.5 | >23, 9.5, 2.3, 1.3, 1.1, 0.6, 0.5 |

ND, not digested.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Detection of plasmids in OT-resistant isolates of A. salmonicida and plasmid transfer to E. coli.

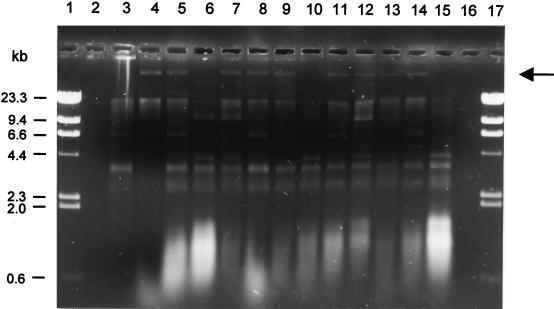

Analysis of plasmid mini preparations demonstrated that all 29 of the OT-resistant isolates of A. salmonicida contained high-molecular-weight plasmids (Fig. 1); 19 (66%) of the plasmids were transferable to E. coli XL-1 Blue MR and HB101 in broth conjugation experiments (Table 6). These plasmid DNA bands were not present in the OT-sensitive isolates. None of the Canadian or United States isolates transferred the OT resistance phenotype to E. coli XL-1 Blue MR or HB101, nor did five of the Scottish isolates. Transconjugants were recovered on plates containing 30 μg of OT per ml after incubation at 37°C to select against the A. salmonicida donors. The same results were obtained when a filter mating conjugation method was used instead of the broth conjugation method (data not shown). Additional conjugation experiments were carried out by using A. salmonicida OT-resistant strains as the donors and E. coli XL-1 Blue MR as the recipient to obtain transfer frequencies. It was determined that the frequencies ranged from 10−3 to 10−6 per donor and 10−1 to 10−6 per recipient (Table 7). Sandaa and Enger (27) reported that the R-plasmid pRAS1, which was isolated from an atypical isolate of A. salmonicida in Norway, had a frequency of transfer to E. coli HB101 of 1.4 × 10−2 per donor. This result is within 1 order of magnitude of the range of values recorded in the present study. However, it is difficult to compare the data since in this study we used a broth conjugation method to determine transfer frequencies, whereas Sandaa and Enger (27) used a filter mating technique.

FIG. 1.

Plasmid profiles of OT-resistant and -sensitive isolates of A. salmonicida. Lanes 1 and 17, markers (HindIII digest of λ DNA): lanes 2 and 16, blank; lanes 4 to 14, plasmid DNA from A. salmonicida OT-resistant isolates MT1402, MT1431, MT1434, MT1427, MT1401, MT1407, MT1432, MT0918, MT1425, MT1406, and MT1413, respectively; lanes 3 and 15, plasmid DNA from OT-sensitive isolates 256/91 and AS20, respectively. The arrow indicates the position of the large plasmids. Not all plasmids were routinely obtained at sufficiently high yields to be detected by photography (lanes 6 and 10).

TABLE 6.

Transfer of OT resistance from A. salmonicida isolates to E. coli XL-1 Blue MR and HB101 by conjugation

| Transfer of OT resistance to E. coli XL-1 Blue MR and HB101 |

A. salmonicida strains |

|---|---|

| Detected | Banks, MT0048, MT0164, MT0320, MT0321, MT0336, MT0350, MT0404, MT0900, MT0903, MT0904, MT0906, MT0918, MT1407, MT1410, MT1413, MT1427, MT1431, MT1432 |

| Not detected | 86442, 89547, 90617, 90644, MT1401, MT1402, MT1406, MT1425, MT1434, Q203 |

TABLE 7.

Summary of conjugation data

| Recipient (OT sensitive) | Donor (OT resistant) | Frequency of conjugation per cell

|

% of recipient or donor strains capable of conjugation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor | Recipient | |||

| A. salmonicida | A. salmonicida | 10−5–10−7 | 10−6–10−7 | 78 (recipients) |

| E. coli | 10−5–10−8 | 10−5–10−7 | 55 (recipients) | |

| E. coli | A. salmonicida | 10−3–10−6 | 10−1–10−6 | 66 (donors) |

| A. salmonicida (environmental strains) | A. salmonicida | 10−5–10−7 | 10−5–10−7 | 50 (recipients) |

| E. coli | 10−4–10−8 | 10−4–10−8 | 50 (recipients),a 63 (recipients)b | |

| A. trota | A. salmonicida | 10−4–10−7 | 10−4–10−7 | 66 (donors) |

| Aeromonas type strains | A. salmonicida | 10−5–10−7 | 10−7–10−8 | 44 (recipients) |

| E. coli | 10−4–10−7 | 10−4–10−7 | 44 (recipients),b 67 (recipients)a | |

The donor was an E. coli transconjugant containing pASOT2.

The donor was an E. coli transconjugant containing pASOT.

Several studies have investigated the transfer of R-plasmids from fish pathogens to other bacteria. Sandaa and Enger (26, 27) reported high-frequency transfer of plasmids pRAS1 and RP4 from A. salmonicida to E. coli and marine bacteria. Interestingly, both plasmids exhibited the highest transfer frequencies to E. coli. Similarly, Toranzo et al. (30) reported frequencies of 10−4 to 10−7 for conjugal transfer of plasmids from bacteria isolated from farmed rainbow trout to E. coli. Moreover, Kruse and Sørum (17) described R-plasmid transfer from A. salmonicida (present in infected salmon muscle) to E. coli on a cutting board. In this work, the highest frequency of transfer was from A. salmonicida to E. coli.

An examination of the plasmid contents of E. coli transconjugants showed that they all had acquired a large plasmid. In some cases, one, two, or all three of the low-molecular-weight plasmids common to most A. salmonicida isolates (9) were also detected. E. coli XL-1 Blue MR was then transformed (selecting for resistance to 30 μg of OT per ml) with each of the large plasmids that had been prepared from the transconjugants and purified from low-melting-point agarose gels. For each of the large plasmids that could be transferred to E. coli from the 19 OT-resistant isolates of A. salmonicida, the presence of the large plasmid alone was demonstrated with plasmid mini preparations. This confirmed that the large plasmids were R-plasmids.

Cloning of the gene encoding OT resistance from an R-plasmid (pASOT).

A prime objective of this study was to determine the molecular basis for the observed OT resistance in A. salmonicida. A large R-plasmid that was designated pASOT and was purified from E. coli transformant MT1407x was used as the source of the OT resistance determinant in cloning experiments. Cloning involved the use of Sau3A partial digestion to generate fragments of pASOT, followed by ligation into the BamHI site of pUC19 and transformation of E. coli XL-1 Blue MR to OT resistance. Analysis of plasmid mini preparations from colonies of OT-resistant transformants revealed that DNA was added to pUC19. A 1.2-kb Sau3A fragment from one transformant (1407xa) was used to produce the DIG-labeled probe AST for use in hybridization studies.

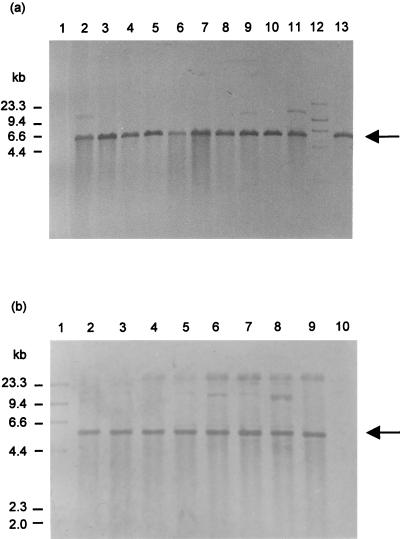

Hybridization experiments performed with the cloned OT resistance determinant from pASOT.

EcoRI-digested plasmid DNA prepared from E. coli transformants were blotted onto nylon membranes and incubated with the DIG-labeled probe AST described above. Strong hybridization with a 5.4-kb EcoRI fragment was observed with all 19 OT-resistant strains and also with plasmid pRAS1. Moreover, hybridization was not observed with plasmid preparations produced from OT-sensitive strains of A. salmonicida or with untransformed E. coli (Fig. 2a).

FIG. 2.

(a) Southern blot analysis of plasmid DNA prepared from E. coli transformants digested with EcoRI and hybridized with probe AST. Strong hybridization occurred with a 5.4-kb fragment in lanes 2 to 11 and 13, which contained plasmid DNA from the following transformants: MT0404x, MT0321x, MT1407x, MT0903x, MT1410x, MT0900x, MT1431x, MT0164x, Banksx, MT1427x, and 718x, respectively. Lane 1 contained plasmid DNA from OT-sensitive A. salmonicida isolate 96. Lane 12 contained markers (HindIII digest of DIG-labeled λ DNA). (b) Southern blot analysis of plasmid DNA prepared from E. coli transformants digested with EcoRI and hybridized with probe TA. Strong hybridization occurred with a 5.4-kb fragment in lanes 2 to 9, which contained plasmid DNA from the following transformants: MT1407x, MT1410x, MT0164x, MT1427x, MT0350x, MT1413x, MT0404x, and 718x, respectively. Lane 1 contained markers (HindIII digest of DIG-labeled λ DNA), and lane 10 contained plasmid DNA from the OT-sensitive isolate A. salmonicida 96.

Determination of the classes of resistance determinants in the OT-resistant isolates of A. salmonicida.

Plasmid DNA produced from five strains of E. coli carrying resistance determinants A to E (Table 4) were used to prepare Southern blots. These blots were then hybridized with probe AST; hybridization was observed only with the class A determinant. On the basis of these results, a second probe was constructed from the class A determinant carried in pUC18. This probe, probe TA, was used in hybridization experiments performed with the EcoRI digests described above. All 19 transferable plasmids (and pRAS1) carried the class A OT resistance determinant on a 5.4-kb EcoRI fragment previously detected with probe AST. Hybridization was not observed with DNA prepared from OT-sensitive isolates or untransformed E. coli (Fig. 2b).

Andersen and Sandaa (1) reported that tetracycline resistance determinant E was the most widespread determinant in bacterial isolates obtained from polluted and unpolluted marine sediments in Norway and Denmark; it was detected in 63% of the isolates. The class A tetracycline resistance determinant was detected in only 5% of the samples, and the class D determinant was detected in 4% of the samples. In Japan, the class D tetracycline resistance determinant is common in the fish pathogens Aeromonas hydrophila, Edwardsiella tarda, and Pasteurella piscicida (= Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida) (4). A study of A. hydrophila in the United States reported that 50% of OT-resistant isolates obtained from aquaculture carried the class E determinant, whereas 35% carried the class A determinant (10). Interestingly, one isolate in that study contained both determinants. It is noteworthy that all of the transferable plasmids examined in this study contained the same resistance determinant on an EcoRI fragment of the same size. The strains of A. salmonicida from which these plasmids were isolated were collected between 1982 to 1993, and, although they all came from Scottish sites, they were not otherwise related. Therefore, it appears that the resistance determinant identified in this work established a foothold among Scottish isolates of A. salmonicida and persisted for at least 11 years.

Characterization of the 19 conjugative R-plasmids.

E. coli transformants exhibited resistance to streptomycin, whereas transformants carrying pRAS1 displayed resistance to both streptomycin and trimethoprim. Additional data relating to resistance phenotypes were obtained by assessing MIC of streptomycin and trimethoprim. There was some variation in the MIC recorded for the different transformants. Thus, seven transformants were sensitive to streptomycin; seven isolates had an MIC of 6.25 μg ml−1, four isolates had an MIC of 12.5 μg ml−1, and one isolate had an MIC of 25 μg ml−1. Only transformants carrying pRAS1 were resistant to trimethoprim; the MIC of this antibiotic and the MIC of streptomycin were both 25 μg ml−1.

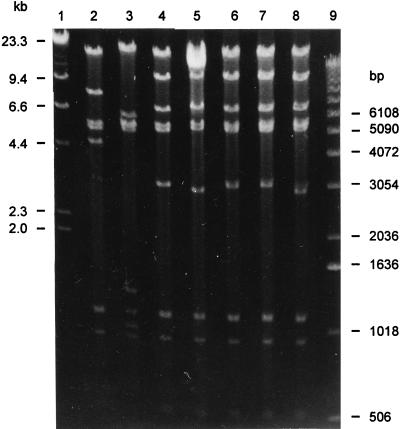

Midi preparations of plasmid DNA were produced from seven E. coli transformants containing R-plasmids from A. salmonicida 718, MT0320, MT0903, MT0906, MT1407, MT1432, and MT1410, which were selected on the basis of their antibiotic resistance profiles. Single restriction endonuclease digestion of plasmid DNA was performed with EcoRI, HindIII, BamHI, and SalI, and double digestion was performed with endonucleases HindIII plus PvuI, BamHI plus PvuI, and BamHI plus HindIII. Digestion with EcoRI generated multiple fragments for all of the plasmids. However, it was evident that there were differences in the band patterns (Fig. 3). Thus, the plasmids prepared from transformants MT0903x, MT1407x, and MT1410x formed a distinct group (profile 1). A band pattern similar to profile 1 was obtained for plasmids from MT0906x and MT1432x, but a 2.9-kb fragment was present in place of the 3.1-kb fragment present in profile 1; this band pattern was designated profile 2. It was interesting that the profile 2 plasmids did not encode streptomycin resistance, whereas profile 1 plasmids did. It is possible that streptomycin resistance is carried on the 3.1-kb fragment. However, this was not confirmed in the present work, and further investigation will be required to determine the location of the streptomycin resistance determinant. EcoRI digestion of plasmid DNA from MT0320x generated a unique set of fragments (profile 3), as did EcoRI digestion of pRAS1 (718x) (profile 4). However, these profiles shared with profiles 1 and 2 the 5.2- and 5.4-kb doublet; the OT resistance determinant is located on the 5.4-kb fragment of this doublet. Data from additional restriction endonuclease digestion supported the findings obtained with EcoRI, with the plasmids falling into the same four groups with each endonuclease or combination of endonucleases tested. The sizes of the fragments generated by these digestion are shown in Table 5. The remaining 13 transferable R-plasmids were digested with EcoRI to determine if the four profiles obtained with the seven test isolates were also produced by the other R-plasmids. Data from the resulting digests indicated that there was some correlation between EcoRI fragment profiles and the expression of a streptomycin resistance phenotype. Thus, plasmids from the seven streptomycin-sensitive isolates produced the same EcoRI digestion profile (profile 2). In contrast, two profiles were exhibited by the plasmids encoding streptomycin resistance, with eight of the plasmids producing profile 1 and four plasmids producing profile 3 (Table 8).

FIG. 3.

Restriction endonuclease fragment patterns generated by EcoRI digestion of plasmid pRAS1 (from E. coli transformant 718x) and R-plasmids from E. coli transformants MT0320x, MT0903x, MT0906x, MT1407x, MT1410x, and MT1432x. Lane 1, markers (HindIII digest of λ DNA); lane 2, 718x; lane 3, MT0320x; lane 4, MT0903x; lane 5, MT0906x; lane 6, MT1407x; lane 7, MT1410x; lane 8, MT1432x; lane 9, markers (1-kb DNA ladder).

TABLE 8.

Grouping of OT-resistant isolates of A. salmonicida based on EcoRI digestion profiles of R-plasmids and antibiotic resistance phenotype

| Profile | Plasmid | Antibiotic resistancea | Strain(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | pASOT | Smr Tms | MT0048, MT0404, MT0900, MT0903, MT0918, MT1407, MT1410, MT1413 |

| 2 | pASOT2 | Sms Tms | Banks, MT0164, MT0350, MT0906, MT1427, MT1431, MT1432 |

| 3 | pASOT3 | Smr Tms | MT0320, MT0321, MT0336, MT0904 |

| 4 | pRAS1 | Smr Tmr | pRAS1 |

Smr, streptomycin resistance; Sms, streptomycin sensitivity; Tmr, trimethoprim resistance; Tms, trimethoprim sensitivity.

Assessment of homology among the four plasmid profiles.

As shown in Table 9, some restriction endonuclease fragments were common to all four plasmid types. This indicated that the plasmids (including pRAS1) could be related at the molecular level. BamHI digestion did not provide any information concerning the relatedness of the plasmids. However, digestion with HindIII demonstrated that two fragments (3.5 and 1.9 kb) were common to plasmid profiles 1 (pASOT) and 2 (pASOT2). SalI digestion indicated that two fragments (12 and 0.6 kb) were also shared by these two plasmid types. A number of fragments common to all four profiles were identified in EcoRI digests, as were two fragments at 9.4 and 6.3 kb which were seen only in profiles 1 and 2 (Table 9). Analysis of the fragments produced from the double digests reinforced the likelihood that the plasmids had a common ancestry. Thus, four fragments common to pASOT and pASOT2 were observed following digestion with HindIII plus PvuI, and one of these fragments (1.5 kb) was present in all four profiles. The results presented in Table 9 indicate that pRAS1 exhibits significant homology with pASOT and pASOT2, whereas profile 3 (pASOT3) is as a more distant relative of the other three profiles.

TABLE 9.

Restriction enzyme digest fragments common to two or more plasmid profiles

| Restriction enzyme(s) | Fragments sizes (kb)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profile 1 (pASOT) | Profile 2 (pASOT2) | Profile 3 (pASOT3) | Profile 4 (pRAS1) | |

| SalI | >23, 0.6 | >23, 0.6 | NDa | >23 |

| BamHI | >23 | >23 | ND | >23 |

| HindIII | >23, 3.5, 1.9 | >23, 3.5, 1.9 | ND | >23 |

| EcoRI | 15, 9.4, 6.3, 5.4, 5.2, 1.1, 0.9, 0.5 | 15, 9.4, 6.3, 5.4, 5.2, 1.1, 0.9, 0.5 | 5.4, 5.2, 1.1, 0.9 | 15, 5.4, 5.2, 1.1, 0.9, 0.5 |

| HindIII + PvuI | >23, 3.8, 2.1, 1.5, 1.3 | >23, 3.8, 2.1, 1.5, 1.3 | >23, 1.5 | >23, 3.8, 2.1, 1.5, 1.3 |

| BamHI + HindIII | >23, 3.6, 1.2, 0.5 | >23, 3.6, 1.2, 0.5 | ND | >23, 0.5 |

| BamHI + PvuI | >23, 9.5, 1.5., 1.1, 0.6, 0.5 | >23, 9.5, 1.5, 1.1, 0.6, 0.5 | >23, 1.5, 0.5 | >23, 1.5, 1.1, 0.6, 0.5 |

ND, not digested.

Estimation of the molecular weights of plasmids pASOT, pASOT2, pASOT3, and pRAS1.

None of the restriction endonucleases generated fragments that were all in a size range (0.5 to 10 kb) that allowed accurate determinations of the molecular weights of plasmids pASOT, pASOT2, pASOT3, and pRAS1. In all of the digests except the EcoRI digests there was a restriction endonuclease fragment which was larger than 23 kb (the largest size for which a marker fragment was available). However, based on the EcoRI digest data (Table 5), the plasmids were estimated to have the following minimum molecular weights (to the nearest whole number): pASOT and pASOT2, 47 kb; pASOT3, 39 kb; and pRAS1, 44 kb. Sandaa and Enger (27) determined that pRAS1 had a molecular mass of 25 MDa (37.5 kb) based on data from EcoRI digestion, although no figure showing the digest was provided in support of this. Livesley et al. (18) analyzed plasmid profiles of A. salmonicida isolates by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. This method separated a range of plasmids, resulting in resolution of both high- and low-molecular-weight plasmids (5 to 100 kb) on the same gel. Thus, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis may provide a means by which the molecular weights of the R-plasmids identified in this study can be accurately determined.

Assessment of the potential for intra- and interspecies transfers of the OT resistance plasmids.

Sandaa and Enger (26, 27) reported that plasmid pRAS1 could be transferred to a range of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Lactobacillus sp.). We therefore performed broth conjugation experiments with plasmids pASOT, pASOT2, and pASOT3 to examine whether inter- and intraspecies transfers of the OT resistance phenotype could take place. The results of numerous broth conjugation experiments performed in this study are summarized in Table 7. We found that 78% of the OT-sensitive strains of A. salmonicida received the R-plasmids from two different OT-resistant A. salmonicida donors (both carrying pASOT). A smaller proportion (55%) of the OT-sensitive recipients acquired the OT resistance phenotype in crosses in which an E. coli transconjugant was the donor (Table 7). In experiments in which OT-sensitive Aeromonas spp. (predominantly isolated from healthy fish) were used as recipients with OT-resistant A. salmonicida donors (carrying pASOT), 50% of the recipients acquired the R-plasmids. The same proportion (50%) was observed when an E. coli transconjugant carrying pASOT2 was used as the host, whereas a higher percentage of the recipients (63%) developed the OT resistance phenotype after crosses in which a transconjugant carrying pASOT was used as the host (Table 7). Transfer of the OT resistance phenotype to 44% of the Aeromonas type cultures was observed with two OT-resistant A. salmonicida donors (both carrying pASOT). E. coli transconjugants carrying pASOT and E. coli transformants carrying pASOT2 transferred the R-plasmid to 44 and 67% of the type cultures, respectively (Table 7). The conjugation experiments in which two strains of E. coli were used indicated that 10 of the R-plasmids were nontransferable (Table 6). In order to examine the possibility that this was due to the recipient, conjugation experiments were performed with the human pathogen Aeromonas trota as an alternative recipient in crosses with the 29 OT-resistant A. salmonicida isolates. It was observed that the same 19 isolates of A. salmonicida which conjugated with E. coli also conjugated with A. trota.

In terms of frequency of transfer, the highest level of conjugal transfer was observed when E. coli XL-1 Blue MR was used as the recipient (Table 7). The frequencies of transfer observed in the other experiments were similar for the majority of crosses (that is, in the range of 10−4 to 10−8 per donor or recipient).

The results reported above were not entirely unexpected given that pRAS1 showed a degree of relatedness to the three R-plasmids. Indeed, the data gave some support to the strongly debated hypothesis that antibiotic-resistant strains of fish pathogens may act as reservoirs for resistance genes, which could subsequently be transferred to bacteria having public health significance (17, 20, 28, 31). Our results suggest that transfer of the R-plasmids between A. salmonicida isolates could be extended through the presence of carrier or mediator bacterial species, such as E. coli. A cycle of resistance transfer could exist in the environment, with transfer occurring between A. salmonicida and a range of unidentified mediator bacterial species. The fate of A. salmonicida in open waters or in fish farm sediments continues to be a highly contentious issue (5). It is important to consider that the experimental procedures used in this study and the majority of previous studies are not representative of the conditions that are encountered in fish farm environments. The use of cells which were grown to high densities in nutritionally rich media and which were subsequently brought into contact as pure cultures was a very artificial means by which to estimate the environmental implications of R-plasmid transfer. Similarly, the use of laboratory strains of E. coli could be questioned. In future experiments workers should aim to employ bacteria isolated from fish farm environments and to develop methods that are more representative of the conditions found in such locations. In this context, it has been reported that the gut contents of fish is a suitable environment for in vitro plasmid-mediated transfer of resistance (24) and that OT resistance was transferred successfully from A. salmonicida to E. coli. However, this result could not be reproduced in vivo. The authors speculated that it was unlikely that human pathogenic bacteria could acquire antibiotic resistance by this route. Other workers have noted that based on a review of the evidence available at the time, transfer of R-plasmids from fish pathogens to potential human pathogens was a rare event (28). No evidence has emerged since then to contradict this observation. Therefore, it is probably inadvisable to attach too much significance to the data generated by the in vitro conjugation experiments in relation to the risk posed by the release of OT-resistant A. salmonicida into open waters. Nevertheless, the observation that the R-plasmids identified in the present study were recovered from samples collected over 11 years from unrelated sites strongly suggests that these plasmids are persistent in fish farm environments and that they may reside in bacterial species other than A. salmonicida.

At present, there is insufficient experimental evidence to allow definite conclusions to be reached as to the environmental significance of OT usage (or the usage of any other antibiotic) in aquaculture (28). However, the present study provided some data that may help clarify the situation. In particular, we demonstrated that the use of modern molecular techniques can generate highly specific information regarding the mechanisms of antibiotic resistance that are used by fish pathogens. It is anticipated that the continued application of such techniques will help provide some answers to the many issues relating to antibiotic usage in aquaculture. The findings of this study represent a significant advance in knowledge concerning the nature of OT resistance in Scottish isolates of A. salmonicida. There is a need for this research to be extended to the examination of isolates from other geographical locations and, indeed, to other fish pathogens. In addition, attempts should be made to perform experiments to determine the ability of plasmids to be spread among the bacterial population present in and beyond fish farm environments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersen S R, Sandaa R-A. Distribution of tetracycline resistance determinants among gram-negative bacteria isolated from polluted and unpolluted marine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:980–912. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.3.908-912.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoki T, Egusa S, Kimura T, Watanabe T. Detection of R factors in naturally occurring Aeromonas salmonicida strains. Appl Microbiol. 1971;22:716–717. doi: 10.1128/am.22.4.716-717.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aoki T, Kitao T, Iemura N, Mitoma Y, Nomura T. The susceptibility of Aeromonas salmonicida strains isolated in cultured and wild salmonids to various chemotherapeutants. Bull Jpn Soc Sci Fish. 1983;49:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoki T, Takahashi A. Class D tetracycline resistance determinants of R-plasmids from the fish pathogens Aeromonas hydrophila, Edwardsiella tarda, and Pasteurella piscicida. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1278–1280. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.8.1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Austin B, Austin D A. Bacterial fish pathogens: disease in farmed and wild fish. 2nd ed. Chichester, United Kingdom: Ellis Horwood; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnes A C, Lewin C S, Hastings T S, Amyes S G B. In vitro activities of 4-quinolones against the fish pathogen Aeromonas salmonicida. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1819–1820. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.9.1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes A C, Amyes S G B, Hastings T S, Lewin C S. Fluoroquinolones display rapid bactericidal activity and low mutation frequencies against Aeromonas salmonicida. J Fish Dis. 1991;14:661–667. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes A C, Lewin C S, Hastings T S, Amyes S G B. Alterations in outer membrane proteins identified in a clinical isolate of Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida. J Fish Dis. 1992;15:279–282. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belland B J, Trust T J. Aeromonas salmonicida plasmids: plasmid-directed synthesis of proteins in vitro and in Escherichia coli minicells. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:513–524. [Google Scholar]

- 10.DePaola A, Flynn P F, McPhearson R M, Levy S B. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of tetracycline- and oxytetracycline-resistant Aeromonas hydrophila from cultured channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) and their environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1861–1863. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.7.1861-1863.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis A E. Immunization with bacterial antigens: furunculosis. Dev Biol Stand. 1997;90:107–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutsell J. Sulfa drugs and the treatment of furunculosis in trout. Science. 1946;104:85–86. doi: 10.1126/science.104.2691.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiney M, Dawson M T, Heery D M, Smith P R, Gannon F, Powell R. DNA probe for Aeromonas salmonicida. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1039–1042. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.3.1039-1042.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu H-M, Bowser P R, Schachte J H, Scarlett J H, Babish J G. Winter field trials of enroflaxacin for the control of Aeromonas salmonicida infections in salmonids. J World Aquacult Soc. 1995;26:307–314. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inglis V, Yimer E, Bacon E J, Ferguson S. Plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance in Aeromonas salmonicida isolated from Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., in Scotland. J Fish Dis. 1993;16:593–599. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kado C I, Liu S T. Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:1365–1373. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.3.1365-1373.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kruse H, Sørum H. Transfer of multiple drug resistance plasmids between bacteria of diverse origins in natural microenvironments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;60:4015–4021. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.11.4015-4021.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livesley M A, Smith S N, Armstrong R A, Barker G A. Analysis of plasmid profiles of Aeromonas salmonicida isolates by pulsed field gel electrophoresis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;146:297–301. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinsen B, Myhr E, Reed E, Håstein T. In vitro antimicrobial activity of sarafloxacin against clinical isolates of bacteria pathogenic to fish. J Aquat Anim Health. 1991;3:235–241. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Midtvedt T, Lingaas E. Putative public health risks of antibiotic resistance development in aquatic bacteria. In: Michel C, Alderman D, editors. Chemotherapy in aquaculture: from theory to reality. Paris, France: Office International des Epizooties; 1992. pp. 302–314. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oppegaard H, Sørum H. gyrA mutations in quinolone-resistant isolates of the fish pathogen Aeromonas salmonicida. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2460–2464. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.10.2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oppegaard H, Sørum H. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the DNA gyrase gyrA gene from the fish pathogen A. salmonicida. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1126–1133. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richards R H, Inglis V, Frerichs G N, Millar S D. Variation in antibiotic resistance patterns of Aeromonas salmonicida isolated from Atlantic salmon Salmo salar L. in Scotland. In: Michel C, Alderman D, editors. Chemotherapy in aquaculture: from theory to reality. Paris, France: Office International des Epizooties; 1992. pp. 276–284. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rio-Rodriguez D R E, Inglis V, Millar S D. Survival of Escherichia coli in the intestine of fish. Aquacult Res. 1997;28:257–264. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandaa R-A, Enger O. Transfer in marine sediments of the naturally occurring plasmid pRAS1 encoding multiple antibiotic resistance. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;60:4234–4238. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4234-4238.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandaa R-A, Enger O. High frequency transfer of a broad host range plasmid present in an atypical strain of the fish pathogen Aeromonas salmonicida. Dis Aquat Org. 1996;24:71–75. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith P, Hiney M P, Samuelsen O B. Bacterial resistance to antimicrobial agents used in fish farming: a critical evaluation of method and meaning. Annu Rev Fish Dis. 1994;4:273–313. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snieszko S F, Griffin P J. Successful treatment of ulcer disease in brook trout with terramycin. Science. 1951;112:717–718. doi: 10.1126/science.113.2947.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toranzo A E, Combarr P, Lemos M L, Barja J L. Plasmids coding for transferable drug resistance in bacteria isolated from cultured rainbow trout. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:872–877. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.4.872-877.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe T, Aoki T, Ogata Y, Egusa S. R factors to fish culturing. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1971;182:383–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1971.tb30674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wood S C, McCashion R N, Lynch W H. Multiple low-level antibiotic resistance in Aeromonas salmonicida. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;29:992–996. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.6.992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]