Background:

We aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of oriental medicine (OM) treatments as monotherapy and add-on therapy compared to conventional treatments for knee osteoarthritis and assess the quality of evidence for these results. OM treatment included acupuncture, herbal medicine, pharmacoacupuncture, and moxibustion.

Methods:

PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, Google Scholar, 4 Korean medical databases (KoreaMed, Korean Studies Information Service System, Research Information Service System, and Oriental Medicine Advanced Searching Integrated System), and one Chinese database (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) were searched for articles published between January 1, 2000, and January 1, 2021. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the effect of OM interventions, single or combined with conventional treatments, on knee osteoarthritis were searched. The risk of bias and quality of evidence of the included studies were evaluated using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation methods, respectively.

Results:

A total of 3911 relevant studies were retrieved and only 23 studies were included for systematic review. Most of the studies showed a significant effect on knee osteoarthritis. 21 studies comparing single OM treatment with conventional treatment were included in the meta-analysis. The effect size of standardized mean difference (SMD) was analyzed as a “small effect” with 0.48 (95% CI −0.80 to −0.16, Z = 2.98, P = .003). In addition, a meta-analysis of 4 studies comparing integrative treatment with conventional treatment showed a “very large effect” with 1.52 (95% CI −2.09 to −0.95, Z = 5.19, P < .001).

Conclusion:

Our results suggest that single OM treatment and integrative treatment significantly reduce pain in patients with knee osteoarthritis. However, there is a limited number of RCTs considering integrative treatment which implies more related RCTs should be conducted in the future.

Keywords: acupuncture, herbal medicine, hyaluronic acid injection, knee osteoarthritis, moxibustion, NSAIDs

1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a non-inflammatory and degenerative disease that causes the deterioration of the joint cartilage and eventually the bones. The changes caused by OA usually occur slowly through many years resulting in chronic disability for 302 million people around the world. As life expectancy increases, the prevalence of OA is expected to increase further. The pathological change seen in OA is the abnormal changes in subchondral bones, followed by the formation of osteophytes.[1] Common signs include tenderness, swelling, and stiffness in the morning. OA symptoms vary from stiffness to persistent mild pain, or severe joint pain making it difficult to perform daily tasks. Since there is no reverse in the course of OA, the treatment of knee OA focuses on symptomatic relief including reducing pain or improving joint function.[2]

According to the American College of Rheumatology published in 2019, the recommended management is divided into 3 categories: surgical therapy, pharmacologic intervention, and non-pharmacological intervention. Exercise and weight loss are the most strongly recommended non-pharmacological interventions for non-surgical patients. In addition, yoga and tai chi are also included. Pharmacologic interventions include drug therapy represented by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and injection therapy such as glucocorticoid injection. Other than these, platelet-rich plasma therapy and prolotherapy are used in clinical practice, but the evidence for these therapies is insufficient.[3]

Since degenerative diseases are chronic and lifelong diseases, patients with knee OA often suffer from the disease for a long time. Therefore, they are usually treated with multiple treatments rather than one treatment, and the demand for a variety of treatment combinations is increasing. Oriental Medicine (OM) is defined by the World Health Organization as an East Asian medicine, which is taken up by several countries of South-East Asia Regions and modified according to the circumstances of each country. Therapeutic interventions of OM include traditional acupuncture, herbal medicine, moxibustion, and more recently pharmacoacupuncture.[4] In Korea, various acupuncture, moxibustion, and herbal medicines were used alone or in various combinations to reduce knee pain and improve knee function.[5–8] According to research studies, acupuncture has a protective effect against cartilage degeneration by inhibiting chondrocyte apoptosis, and electroacupuncture effectively protects the joint and reduces pain.[9,10] Moxibustion improves the condition of the knee joint synovium by reducing interstitial edema and improving blood circulation and local inflammation.[11] Herbal medicine helps to differentiate and regenerate cartilage in degenerative knee arthritis.[12] According to recent clinical studies, acupuncture, moxibustion, and herbal medicines are effective in knee OA due to analgesic effects and are safe to use since they have fewer side effects than western medicines.[13–15] (usual medical care, conventional treatments, pharmacological strategies)

Recently, integrative treatment for knee OA is being mentioned as a new treatment option for patients. In clinical practice in Korea, integrative treatment is imposed through a cooperative medical system between traditional Korean and western medicine. According to randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on integrative therapy, it is more effective in reducing pain, and improving knee function and quality of life than conventional treatment alone.[16,17]

Previously, there were systematic reviews for OM treatment of knee OA. However, previous studies are mostly designed for single OM treatment versus conventional treatment.[2,18] As mentioned above, patients are already receiving alternative treatments in addition to conventional treatments. Therefore, we decided to systematically review integrated treatment versus conventional treatment, in addition to alternative treatment versus conventional treatments for knee OA.

The objective of this study is to compare the clinical applicability of integrative treatments involving various options of oriental medicine interventions. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare conventional treatments (NSAIDs and hyaluronic acid injection) versus OM treatments and integrative treatment versus conventional treatment alone.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and registration

Ethical approval is not necessary because this study is a systematic review, not involving any human beings or experimental subjects. The protocol for this study was registered at Research Registry (registration no. reviewregistry1086, http://www.researchregistry.com) and is published as a research paper.[19] This study is written according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 checklist.[20]

2.2. Eligibility criteria

2.2.1. Types of studies.

Only RCTs written in English, Korean, and Chinese were included to investigate the effect of integrative treatment for patients with knee OA limiting publication status to studies published in journals and thesis. Non-RCTs, quasi-RCTs, animal studies, case series, case reports, uncontrolled trials, and laboratory studies were excluded.

2.2.2. Types of patients.

Patients clinically diagnosed with primary knee OA were included in the study. There were no restrictions according to disease duration, age, sex, race, and education status.

2.2.3. Types of interventions.

The treatment group was given OM treatment including acupuncture, herbal medicine, pharmacoacupuncture, and moxibustion. Acupuncture included manual acupuncture, electroacupuncture, and warm needling, and is defined as stimulation of penetrating the skin using needles. Indirect moxibustion using drugs that are not used in Korea is excluded and only moxibustion and heat-sensitive moxibustion are included. All kinds of pharmacoacupuncture were included regardless of the ingredient whether it is herbal extracts or animal-derived ingredients. Herbal medicines treating knee OA through syndrome differentiation of TKM were included. However, they were limited to prescriptions listed in 10 herbal medicine books recommended by the Korean Food and Drug Administration. Herbal products not used in Korea or self-made decoctions were excluded. The control group was given conventional treatments limited to NSAIDs and hyaluronic acid injections (HA).

In conclusion, the following comparisons were addressed:

Conventional treatment (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDS] and HA) versus single OM treatment

Integrative treatment (Conventional treatment combined with OM treatment) versus conventional treatment alone

2.3. Types of outcome measurements

2.3.1. Primary outcomes.

The primary outcome of this study was pain measured by the visual analog scale or numerical rating scale (NRS).

2.3.2. Secondary outcomes.

The secondary outcome measurement was as follows:

2.3.2.1. Incidence of adverse events (AEs).

AEs were collected and analyzed to confirm the safety of OM treatment used for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis.

2.4. Information sources and literature search

A systematic search strategy was used in this review. The following 9 English, Korean, and Chinese electronic databases were searched for articles from January 1, 2000, to January 1, 2021: PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, Google Scholar (first 100 articles), 4 Korean medical databases (KoreaMed, Korean Studies Information Service System, Research Information Service System, and Oriental Medicine Advanced Searching Integrated System), and one Chinese database (China National Knowledge Infrastructure). The search terms consisted of combinations of keywords for diagnosis and treatment such as “knee osteoarthritis,” “acupuncture,” “herbal medicine,” “pharmacoacupuncture,” and “moxibustion.” The search strategy was adjusted for each database and website. We also manually looked through relevant studies from the references of the studies that had been included.

2.5. Selection process

Systematic review software RevMan 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration, London, UK) was used to import documents retrieved from each database. First, duplicates are excluded. Two reviewers (Y.P. and K.P.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the selected articles and excluded irrelevant articles. Afterward, full-text screening proceeded. The eligibility of the full text of selected articles was evaluated using predetermined eligibility criteria. Disagreements between 2 reviewers are resolved through discussion. If a consensus was not met between them, a third reviewer (YHB) made the final decision.

2.6. Data management and extraction

EndNote X9 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA) reference management system was used to manage the selected studies. Data extractors independently collected primary data from the included articles through RevMan software and filled in the data collection form for each article. Discrepancies or uncertainties were resolved by reaching a consensus through discussion with the senior reviewer (Y.H.B). We contacted the corresponding authors of the included studies if the data needed any clarification. The following information was extracted:

General information: research identifier, publication year, article title, first author, corresponding author, contact information, journal name, and country.

Study methods: study design, sample size, randomization method, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete or selective reporting, and other sources of bias.

Participants: inclusion and exclusion criteria, age, sex, race, onset, and diagnostic criteria for knee OA.

Interventions: conventional intervention (NSAIDS or HA)/type of adjunct therapy, treatment details, treatment duration, and treatment frequency.

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes (as described above).

2.7. Risk of bias in individual studies

We used the Cochrane Collaboration’s bias risk tool to assess the methodological quality of included studies. Two reviewers (Y.C.P. and K.J.P.) independently assessed the risk of bias in the included studies. The following items were evaluated: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, losses to follow up, intention to treat analysis, handling of missing data, funding sources, and other biases. Each item was evaluated as having a low, unclear or high risk of bias. If there were any disagreements, it was resolved with a discussion between 2 researchers or consultation from the senior reviewer (Y.H.B).

2.8. Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity between studies was judged by using forest plots of meta-analysis, which is a visual method, to identify common parts in confidence intervals and effect estimates. Heterogeneity was quantitatively evaluated with Higgins’ I2 statistic. Heterogeneity is considered as follows according to I2 values, “heterogeneity was low if the I2 value was less than 25%,” “heterogeneity was medium if the I2 value was between 25% and 75%,” and “heterogeneity was high if the I2 value was 75% or more.”[21] If considerable heterogeneity was identified, the possible causes were explored through subgroup analyses.

2.9. Synthesis of results

We used the Review Manager 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration, London, UK) to perform a meta-analysis. For continuous data, the results were presented as standardized mean difference (SMD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). For dichotomous data, the results were presented as risk ratio with 95% CI. Through the chi-square test and Higgin’s I2 statistics, a fixed-effects model was used when heterogeneity was considered low, and a random-effects model was used when heterogeneity was considered medium or high. The Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation method was used to evaluate the strength of evidence and summarize the meta-analysis findings.[22] If there were more than 10 studies to analyze, applying Begg’s or Egger’s funnel plot was considered.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

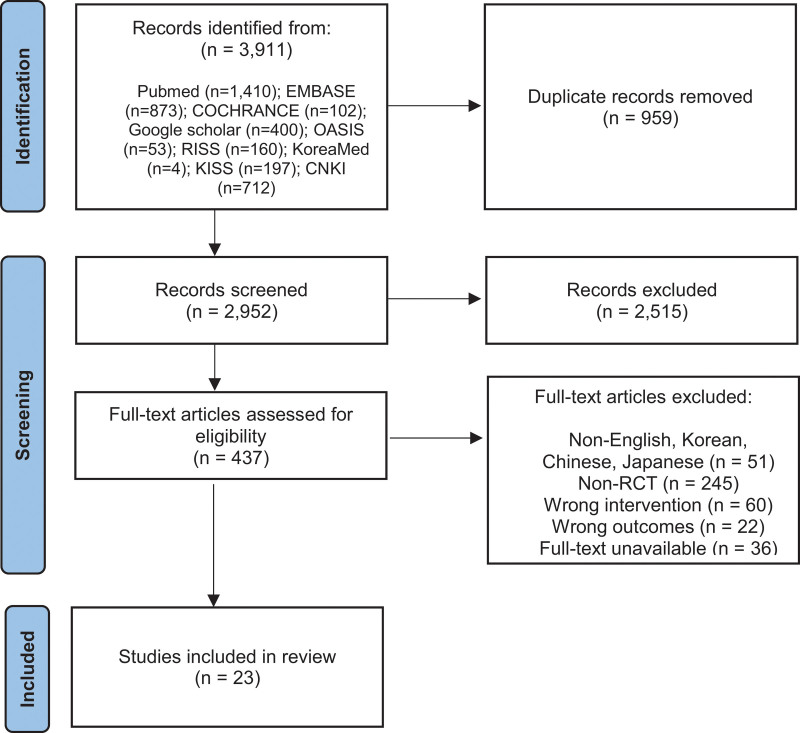

A total of 3911 papers were screened for acupuncture, herbal medicine, pharmacoacupuncture, and moxibustion. After removing 959 duplicates, 2952 were left for the screening of titles and abstracts. Through the title and abstract screening, 437 studies were selected. Afterward, the full texts of 437 studies selected in the first round were reviewed and finally, 23 studies were selected for meta-analysis. The detailed reasons for excluded studies are provided in the flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of this study. PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, RCTs = randomized controlled trials.

3.2. Study characteristics

A total of 23 studies were selected and analyzed (Table 1). Among the 23 studies, Cao 2013,[23] Yang 2012,[25] Miao 2014,[29] Sun 2009,[30] Zhao 2013,[32] and Zhou 2014[33] had 2 experimental groups and were compared with the conventional treatment. Therefore, they were synthesized by dividing them each into 2 different studies, for example, Miao 2014 (1) and Miao 2014 (2) during the meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| First author, year | Country of publication | Sample size | Intervention group (A) | Control group (B) | Total treatment period; Treatment frequency | Outcomes | Adverse events | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | (B) | Type of acupuncture | Type of intervention | |||||

| Cao, 2013[22] | China | (A-1) 50 (A-2) 50 |

50 | (A-1) Herbal Medicine (A-2) Herbal Medicine + Hyaluronic acid injection |

Hyaluronic acid injection | 5 wk; (A-1) twice a day (A-2) twice a day |

Pain intensity measured by NRS | (A-1) 3 (1 diarrhea; 2 nausea) (A-2) 2 (1 diarrhea; 1 nausea) |

| Huang, 2014[23] | China | 35 | 35 | Herbal Medicine + Hyaluronic acid injection | Hyaluronic acid injection | 3 wk; twice a day | Pain intensity measured by NRS | N/R |

| Yang, 2012[24] | China | (A-1) 20 (A-2) 20 |

20 | (A-1) Herbal Medicine (A-2) Herbal Medicine + Hyaluronic acid injection |

Hyaluronic acid injection | 5 wk; (A-1) twice a day (A-2) twice a day |

Pain intensity measured by NRS | N/R |

| Cai, 2013[25] | China | 30 | 30 | Pharmacoacupuncture + Hyaluronic acid injection | Hyaluronic acid injection | 5 wk; once a week | Pain intensity measured by NRS | N/R |

| Fu, 2010[26] | China | 37 | 31 | Moxibustion | Hyaluronic acid injection | 5 wk; once a day | Pain intensity measured by NRS | N/R |

| Deng, 2015[27] | China | 40 | 40 | Warm needling | Ibuprofen | 4 wk; 3 sessions per week | Pain intensity measured by NRS | N/R |

| Miao, 2014[28] | China | (A-1) 35 (A-2) 35 |

35 | (A-1) Electroacupuncture (A-2) Moxibustion |

Celecoxib | 30 d; (A-1) once a day (A-2) once a day |

Pain intensity measured by NRS | N/R |

| Sun, 2009[29] | China | (A-1) 20 (A-2) 20 |

18 | (A-1) Manual acupuncture (A-2) Pharmacoacupuncture |

Celecoxib | 1 mo; (A-1) 3 sessions per week (A-2) 3 sessions per week |

Pain intensity measured by NRS | N/R |

| Vas, 2004[30] | Spain | 48 | 49 | Electroacupuncture + NSAIDs | Diclofenac | 12 wk; N/R | Pain intensity measured by 100 mm pain VAS | N/R |

| Zhao, 2013[31] | China | (A-1) 33 (A-2) 35 |

19 | (A-1) Electroacupuncture (A-2) Moxibustion |

Celecoxib | 4 wk; (A-1) 3 sessions per week (A-2) 3 sessions per week |

Pain intensity measured by NRS | N/R |

| Zhou, 2014[32] | China | (A-1) 44 (A-2) 39 |

22 | (A-1) Electroacupuncture (A-2) Moxibustion |

Celecoxib | 4 wk; (A-1) 3 sessions per week (A-2) 3 sessions per week |

Pain intensity measured by NRS | N/R |

| Zhou, 2015[33] | China | 40 | 40 | Electroacupuncture | Diclofenac | 28 d; once a day | Pain intensity measured by NRS | N/R |

| Deng, 2008[34] | China | 50 | 50 | Herbal Medicine | Diclofenac | 2 wk; once a day | Pain intensity measured by NRS | 0 |

| Fan, 2012[35] | China | 76 | 76 | Herbal Medicine | Celecoxib | 12 wk; twice a day | Pain intensity measured by NRS | 0 |

| Wang, 2017[36] | China | 72 | 72 | Herbal Medicine | Celecoxib | 12 wk; twice a day | Pain intensity measured by NRS | N/R |

| Yuan, 2017[37] | China | 35 | 35 | Herbal Medicine | Celecoxib | 12 wk; twice a day | Pain intensity measured by NRS | N/R |

| Zhang, 2014[38] | China | 35 | 36 | Herbal Medicine | Celecoxib | 12 wk; twice a day | Pain intensity measured by NRS | 1 nausea |

| Zheng, 2019[39] | China | 50 | 50 | Herbal Medicine | Celecoxib | 30 d; twice a day | Pain intensity measured by NRS | 1 nausea |

| Dai, 2019[40] | China | 40 | 40 | Moxibustion | Celecoxib | 4 wk; 3 sessions per week | Pain intensity measured by NRS | N/R |

| Huang, 2017[41] | China | 30 | 30 | Moxibustion | Celecoxib | 5 wk; Every other day | Pain intensity measured by 100mm pain VAS | N/R |

| Yuan, 2015[42] | China | 74 | 74 | Moxibustion | Diclofenac | 30 d; Once a day | Pain intensity measured by 100mm pain VAS | 0 |

| Zhang, 2011[43] | China | 30 | 30 | Moxibustion | Celecoxib | 6 wk; Once a day | Pain intensity measured by NRS | 0 |

| Zhang, 2015[44] | China | 48 | 48 | Moxibustion | Celecoxib | 4 wk; Every other day | Pain intensity measured by NRS | N/R |

N/R = not reported, NRS = numerical rating scale, NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, VAS = visual analog scale.

All of the studies were published after 2000, and 3 studies[30,31,35] published before 2010 were published in 2009, 2004, and 2008, respectively. After 2010, 4 articles were published each in 2014[24,29,33,39] and 2015,[28,34,43,45] one study in 2010[27] and 2011,[44] 2 studies in 2012[25,36] and 2019,[40,41] and 3 studies in 2013[23,26] and 2017./[37,38,42]

Regarding the country of publication, 22 papers (95.7%) were published in China[23–30,32–45] and 1 paper (4.3%) was published in Spain.[31] Except for Vas 2004,[31] all were published in China.

The total number of study participants in 23 studies included in the review was 2101, with 1171 in the intervention group and 930 in the control group. The total number of patients including the intervention group and control group in each study ranged from a minimum of 58 to a maximum of 152. There were 17 studies with 50 to 100 participants[24–28,30–32,34,35,38–42,44,45] and 6 studies with more than 100 participants.[23,29,33,36,37,43]

Conventional treatment, which is the control group of the 23 studies included in this review, can be divided into 2 major categories: drug and injection. There were 5 studies (21.7%) in which the conventional treatment was an injection,[23–27] and all of them used sodium hyaluronate. 18 studies (78.3%) used the drug as a control group,[28–45] all of which used NSAIDs, in specific, celecoxib in 13,[29,30,32,33,36–42,44,45] diclofenac in 4,[31,34,35,43] and ibuprofen in 1.[39]

The OM treatment used in the intervention group of the study was either used alone or in combination with conventional treatment. As mentioned above, 6 studies[23,25,29,30,32,33] have 2 intervention groups making a total of 29 studies when discussing the intervention group. 24 studies (82.8%) used only one OM treatment method, and 5 studies (17.2%) used both OM and conventional treatment.[23–26,31] OM treatment used alone was acupuncture in 6 cases,[28–30,32–34] herbal medicine in 8 cases,[23,25,35–40] pharmacoacupuncture in 1 case,[30] and moxibustion in 9 cases.[27,29,32,33,41–45] Manual acupuncture, electroacupuncture, and warm needling were used for acupuncture. For herbal medicine, Bushen huoxue fang Gagambang 4 cases,[37–40] Gacao Fuzi Decoction 2 cases,[25,35] Duhuojisheng-tang 1 case,[23] and Jiawei Danggui Sini Tang 1 case[36] were used. As for the type of integrative treatment in which conventional and OM treatment were used together, there were 3 studies[23–25] in which herbal medicine and HA were used together, 1 study[26] in which pharmacopuncture and HA were used together, and 1 study[31] in which electroacupuncture and NSAIDs were used together.

The intervention period varied from 2 to 12 weeks, with 6 studies (26%) for 4 weeks,[28,32,33,41] 5 studies (21.8%) for 5 weeks,[23,25–27,42] 5 studies (21.8%) for 12 weeks,[31,36–39] and 3 studies (13%) for 30 days.[29,40,43] In addition, 1 study (4.3%) each for 2 weeks,[35] 3 weeks,[24] 6 weeks,[44] and 1 month.[30]

As a result of analyzing the frequency of intervention by the treatment type of OM treatment, the daily intake of herbal medicine was either once a day or twice a day. Of the 9 studies, there was only 1 study[35] to take herbal medicine once a day and 8 studies twice a day.[23–25,36–40] As for the number of acupuncture procedures per week, 3 times was the most with 4 studies,[28,30,32,33] 2 studies[29,34] performed daily acupuncture procedures, and 1 study[31] did not present the number of procedures. The number of pharmacoacupuncture procedures per week was 3 times[30] and 1 time[26] with each study. As for the number of moxibustion procedures per week, 4 studies[27,29,43,44] mentioned that it was performed every day, 3 studies[32,33,41] 3 times per week, and 2 studies[42,45] every other day.

Seven[23,35,36,39,40,43,44] out of 23 studies reported several adverse events of OM treatment. Among them, 4 studies[35,36,43,44] reported that no adverse events occurred. The remaining 3 studies[23,29,30] all used herbal medicine and reported symptoms of nausea and diarrhea after taking herbal medicine.

The dependent variable of the study was measured with a tool to measure the degree of subjective knee pain in all studies. Numeral Rating Scale was the most frequent in 20 studies (87%),[23–30,32–41,44,45] and 100mm pain visual analog scale was used in 3 studies (13%).[31,42,43]

3.3. Risk of bias assessment

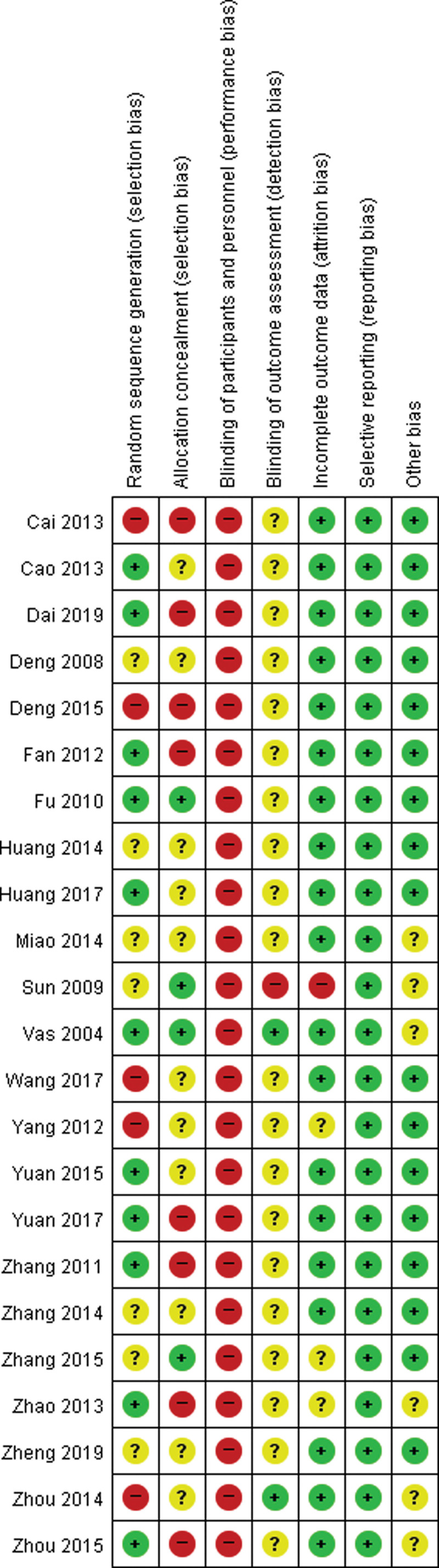

We assessed the risk of bias for each study using the risk of bias tool. Figure 2 shows the results of the Cochrane risk of bias assessment for the 23 studies.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias of included studies.

Among the evaluation items, random sequence generation was mentioned in 11 studies (47.8%) and evaluated as Low-Risk studies. The other 7 studies[24,29,30,35,39,40,45] were evaluated as Unclear Risk because there was no mention of the specific method of the random assignment.

In allocation concealment criteria, 4 studies (17.4%)[27,30,31,45] were classified as Low Risk. They mentioned that the assignment order was kept in an opaque sealed envelope. However, the other 11 studies[23–25,29,33,35,37,39,40,42,43] were evaluated as Unclear Risk because they did not mention whether there was any concealment in the randomization process.

The blinding of participants and personnel was mentioned in none of the 23 studies, and all 23 studies were classified as High Risk. Similarly, the blinding of outcome assessment was mentioned in 2[31,33] of 23 studies (8.7%), and 20 studies were classified as Unclear Risk. These results are due to the difficulty in setting up a sham control group during the intervention, making it difficult to blind the participants. In these trial designs, a single-blind method is often applied but only 2 studies[31,33] mentioned the blinding of the reviewer. And 20 Unclear-Risk studies did not note on reviewer’s blindness.

Of 23 studies, 19 studies (82.6%) reported incomplete outcome data, 23 studies (100.0%) in selective reporting criteria, and 17 studies (73.9%) about whether any other biases were affecting the study results.

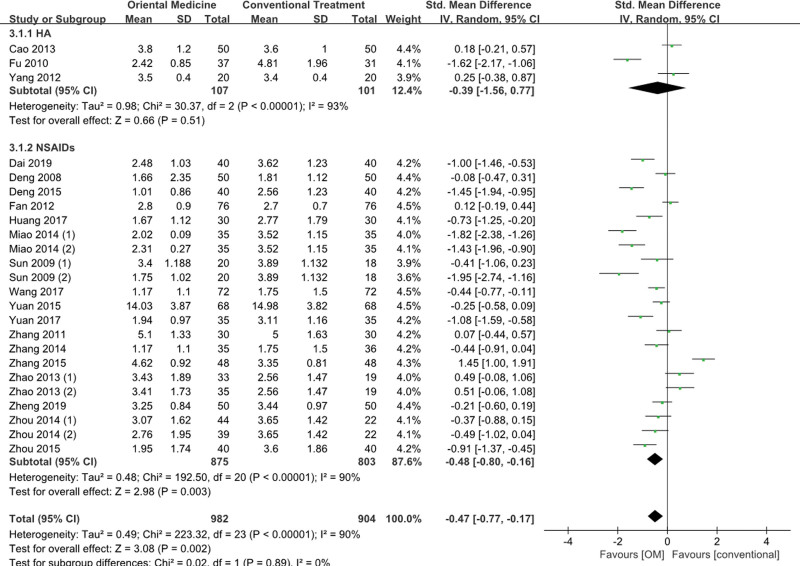

3.4. Synthesis of results: effect of single OM treatment on knee pain

3.4.1. Effect of single OM treatment on pain intensity.

The effect of a single OM treatment on knee pain was compared for 24 cases using only one OM treatment. The effect size of the OM treatment group and the conventional treatment control group was significantly reduced by 0.47 (n = 1886, SMD = −0.47, 95% CI −0.77 to −0.17, Z = 3.08, P = .002) (Fig. 3). However, high heterogeneity was found (Higgins I2 = 90%), and subgroup analysis was performed. For subgroup analysis, the comparison group was divided into the HA group and NSAIDs group, and the OM treatment group versus the HA group and OM treatment group versus NSAIDs group were analyzed. The HA group refers to subjects who received 2mL of hyaluronic acid injection during the study period, and the NSAIDs group refers to subjects who took ibuprofen, celecoxib, and diclofenac.

Figure 3.

Forest plot for single OM treatment versus conventional treatment. CI = confidence interval, HA = hyaluronic acid injections, NSAIDS = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, OM = oriental medicine.

3.4.1.1. Comparison of knee pain reduction effect between OM treatment group and HA group.

A random effect model was used because the analyzed studies displayed high levels of heterogeneity (OM treatment group vs HA group: Higgins I2 = 93%). There was no significant difference between the OM treatment group and HA group in terms of knee pain (n = 208, SMD = −0.39, 95% CI −1.56 to 0.77, Z = 0.66, P = .51).

3.4.1.2. Comparison of knee pain reduction effect between OM treatment group and NSAIDs group.

A random effect model was used because the analyzed studies displayed high levels of heterogeneity (OM treatment group vs NSAIDs group: Higgins I2 = 90%). As a result, knee pain was significantly reduced by 0.48 (n = 1678, SMD = −0.48, 95% CI −0.80 to −0.16, Z = 2.98, P = .003) in the OM treatment group.

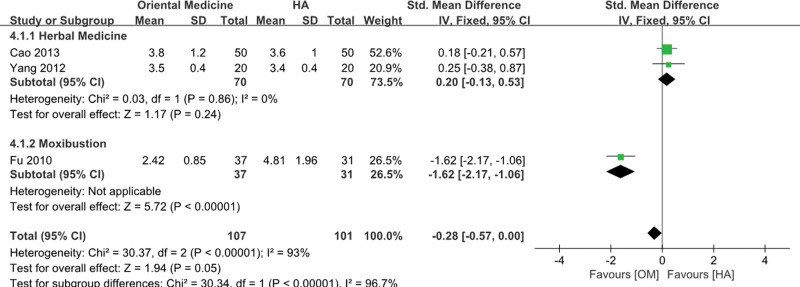

3.4.2. Comparison of knee pain reduction effects according to interventional methods of OM treatment.

To compare the effects of OM treatment interventions on knee pain, subgroup analysis was conducted by dividing the OM treatment group versus the HA group, and the OM treatment group versus the NSAIDs group.

3.4.2.1. Comparison of knee pain effects between the OM treatment group and the HA group according to the intervention methods of OM treatment.

A fixed-effect model was used because the herbal medicine studies displayed no heterogeneity (herbal medicine: Higgins I2 = 0%) (Fig. 4). As a result, there was no significant difference between herbal medicine and HA treatment (SMD = 0.20, 95% CI −0.13 to 0.53, Z = 1.17, P = .24). In contrast, moxibustion significantly reduced knee pain by 1.62 (MD = −1.62, 95% CI −2.17 to −1.06, Z = 5.72, P < .001).

Figure 4.

Forest plot for single OM treatment versus hyaluronic acid injection. CI = confidence interval, HA = hyaluronic acid injections, OM = oriental medicine.

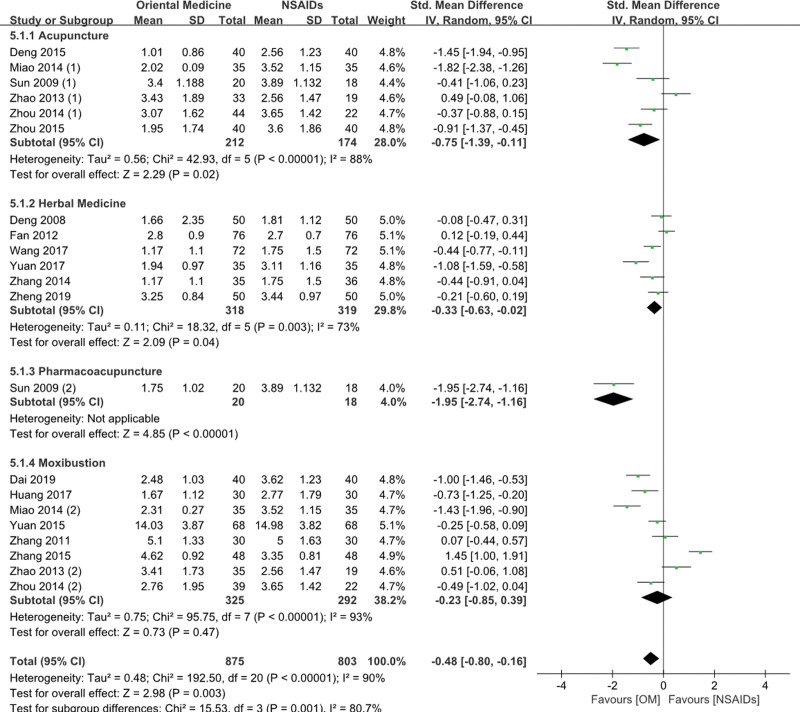

3.4.2.2. Comparison of knee pain effects between the OM treatment group and NSAIDs group according to the intervention methods of OM treatment.

Studies on acupuncture, herbal medicine, and moxibustion appeared to have high levels of heterogeneity (acupuncture: Higgins I2 = 88%, herbal medicine: Higgins I2 = 73%, moxibustion: Higgins I2 = 93%) and they were analyzed with a random effect model (Fig. 5). As a result, acupuncture and herbal medicine significantly reduced knee pain by 0.75 (SMD = −0.75, 95% CI −1.39 to −0.11, Z = 2.29, P = .02) and 0.33 (SMD = −0.33, 95% CI −0.63 to −0.02, Z = 2.09, P = .04), respectively. Pharmacoacupuncture also significantly reduced knee pain by 1.95 (SMD = −1.95, 95% CI −2.74 to −1.16, Z = 4.85, P < .001). In contrast, there was no significant difference between moxibustion and NSAIDs (SMD = −0.23, 95% CI −0.85 to 0.39, Z = 0.73, P = .47).

Figure 5.

Forest plot for single OM treatment versus NSAIDs. CI = confidence interval, NSAIDS = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, OM = oriental medicine.

3.5. Synthesis of results: effect of integrative treatment on pain intensity

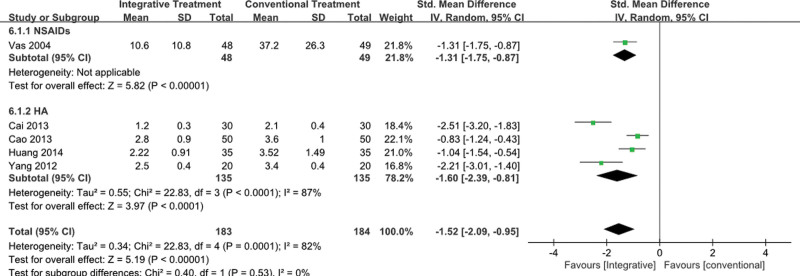

3.5.1. Effect of integrative treatment on pain intensity.

Five studies using integrative treatment combined with OM treatment and conventional treatment compared the effect of integrative treatment on knee pain. As for the effect size between the integrative treatment group and the control group, the integrative treatment group had a significant reduction effect by 1.52 (n = 367, SMD = −1.52, 95% CI −2.09 to −0.95, Z = 5.19, P < .001). However, high heterogeneity was found (Higgins I2 = 82%), and subgroup analysis was performed (Fig. 6). Subgroup analysis was performed by dividing the control group into the NSAIDs group and HA group, respectively, into the intervention group versus the NSAIDs group, and the intervention group versus the HA group.

Figure 6.

Forest plot for integrative treatment versus conventional treatment. CI = confidence interval, HA = hyaluronic acid injections, NSAIDS = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

3.5.1.1. Comparison of knee pain reduction effect between integrative treatment group and NSAIDs group.

Integrative treatment showed favorable results with regard to knee pain by 1.31 (SMD = −1.31, 95% CI −1.75 to −0.87, Z = 5.82, P < .001).

3.5.1.2. Comparison of knee pain reduction effect between integrative treatment group and HA group.

The heterogeneity of the studies was found to be high (Integrative treatment group vs HA group: Higgins I2 = 87%) and the studies were analyzed with a random effect model. As a result, knee pain was significantly reduced in the integrative treatment group by 1.60 (SMD = −1.60, 95% CI −2.39 to −0.81, Z = 3.97, P < .001).

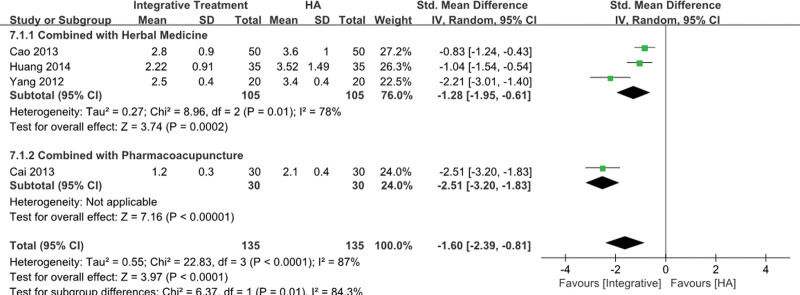

3.5.2. Comparison of the knee pain reduction effect according to the combination constituting the integrative treatment.

Integrative treatment refers to a treatment method using both OM treatment and conventional treatment. A subgroup analysis was attempted to compare the effect of OM treatment on knee pain according to the OM treatment method used together. However, Vas 2004 was the only study comparing the integrative treatment group and the NSAIDs group, so only the integrative treatment group and the HA group were available for subgroup analysis.

In a Vas 2004 study comparing the integrative treatment group and the NSAIDs group, a comparison was made between the intervention group administered with electroacupuncture plus NSAIDs and the control group administered with NSAIDs alone, and a significant improvement was found (P < .001).

3.5.2.1. Comparison of knee pain effects between the integrative treatment group and the HA group according to the intervention method of OM treatment among integrative treatment.

The heterogeneity of herbal medicine studies was found to be high (herbal medicine: Higgins I2 = 78%), and the studies were analyzed with a random effect model (Fig. 7). As a result, herbal medicine showed a significant effect in terms of knee pain by 1.28 (SMD = −1.28, 95% CI −1.95 to −0.61, Z = 3.74, P < .001). Also, pharmacoacupuncture significantly reduced knee pain by 2.51 (SMD = −2.51, 95% CI −3.20 to −1.83, Z = 7.16, P < .001).

Figure 7.

Forest plot for integrative treatment versus hyaluronic acid injection. CI = confidence interval, HA = hyaluronic acid injections.

3.6. Adverse events

Of the 23 studies finally selected, 7 studies reported the presence or absence of AEs. Of these, 4 studies[35,36,43,44] reported no AEs. Deng 2008[35] and Fan 2012[36] were studies comparing herbal medicine to NSAIDs. Yuan 2015[43] and Zhang 2011[44] were studies comparing moxibustion to NSAIDs.

Three studies[23,33,40] reported AEs in herbal medicines. Cao 2013[23] reported diarrhea and nausea which are the most frequently reported symptoms when taking herbal medicines.[46] Zhang 2014[33] and Zheng 2019[40] each reported that patients had nausea after taking herbal medicine. However, these symptoms seem very minor since it is reported that they disappeared after a few days without any treatment, and patients never stopped taking herbal medicine because of nausea or diarrhea. There was no information regarding AEs in the remaining 16 studies.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the effects of OM treatment and OM and conventional treatment together on knee OA. According to our results, both the single OM treatment and integrative therapy are effective in relieving knee OA symptoms. In particular, acupuncture, herbal medicine, and pharmacoacupuncture were effective as a single therapy compared to NSAIDS, and moxibustion was effective compared to HA. Herbal medicine and HA together as an integrative therapy showed significant effects in alleviating knee pain compared to HA.

In the early studies on knee OA, studies comparing only one intervention were predominant.[2,6,47–49] However, it is known that knee OA is not a disease that can be overcome with one treatment method, studies using multiple interventions are increasing recently. Also, it is indicated in the clinical practice guidelines that complex treatment or management is required for the treatment of knee OA.[50,51] In this respect, our study has strengths in that it included RCTs for integrative treatment compared to other SR studies. In addition, it has the strength of including and analyzing RCTs compared to both drug and injection treatment, which are representative of conventional treatments, making it clearly different from other systematic reviews that include only one conventional treatment intervention.

The quality of evidence for the selected studies was evaluated to make our conclusion more evident-based. All of the included studies are RCTs and most of the studies that performed the meta-analysis were evaluated as low in risk of bias. Regarding inconsistency, the quality of evidence was downgraded by one level because most of the I2 values were above 75%. All studies directly compared interventions, so there is no risk of indirectness of evidence. The quality of evidence for imprecision was not downgraded since the number of participants for most studies was sufficient. We are moderately confident in the effect estimate in improvement with pain for knee OA. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but it is likely to be substantially different.

Several factors contributing to high heterogeneity were explored after the control group was made uniform for sub-group analysis. As for acupuncture, the types of acupuncture, the number of acupoints used, and the number of treatment sessions per week were accounted for as the cause of heterogeneity. For herbal medicine, the treatment was generally uniform but the types of herbal medicine varied. In moxibustion, the types of moxibustion, the number and location of acupoints used, and the number of treatments per week contributed to high heterogeneity. Accordingly, intervention factors such as the location of acupoints, timing, or duration of treatment may be the factors for high heterogeneity in this systematic review.

Although the details of treatment vary, our results show that electroacupuncture was preferred with EX-LE4 and ST35 used in common for 1 to 2 times per week. According to one study, electroacupuncture shows greater analgesic effects for knee OA than manual acupuncture.[52] However, in the clinical practice guideline published in Korea, both acupuncture and electroacupuncture are recommended for knee OA. It suggests that manual acupuncture be prescribed to patients with mild knee OA, and electroacupuncture to patients with severe knee OA.[51] For future studies, the type of acupuncture could be applied differently according to the severity of knee OA. Our results present that the most used herbal medicine was Bushen huoxue fang, or its modified prescriptions in decoction form, twice a day. Bushen huoxue fang is a decoction prescribed to patients with shen deficiency and blood stasis according to TCM syndromes.[53] Since knee OA is a degenerative disease, its main pathogenesis can be regarded as shen deficiency and blood stasis, but knee OA can be diagnosed differently in TCM syndromes depending on the patient’s condition or accompanying symptoms. Therefore, in order to reduce the gap with the actual clinical field, it is recommended to prescribe herbal medicines according to pattern identification that are frequently used in clinical practice, for example cold-fever pettern identification in future studies. The most used moxibustion type was basic moxibustion with ST34 or ST35, 1 to 2 times a week. Moxibustion acts to improve blood flow in soft tissues and is widely applied not only to local areas but also to distal acupoints that act systemically.[54] In Miao’s study, CV8 was used to help the circulation of the body and regulate the physical activity of organs and meridians.[29] Due to this characteristic, moxibustion is easy to be used together with other OM treatments in actual clinical practice making it a meaningful option for integrative treatment in future studies.

As for integrative treatment, the number of the selected studies were less than expected. This is because there are many studies comparing OM treatment and integrative treatment, but not many studies comparing conventional treatment and integrative treatment. Referring to risk of bias of RCTs of OM studies, performance bias was generally high. It resulted from the blinding method of OM interventions. Double-blind testing is possible in some OM interventions such as moxibustion[55] but for acupuncture,[56,57] which can be said to be the main treatment of OM intervention, the possibility of double-blind testing is controversial. Because of these characteristics, pragmatic trials or long-term observational studies reflecting the clinical environment may be more appropriate than RCTs on studies about OM interventions or integrative treatments for knee OA. In addition, an integrative clinical pathway for clinical field in collaborative medical setting could be made by combining OM treatments with conventional treatment, for example herbal medicine and HA together.

There are few limitations in this study. Firstly, publication country is biased in this study. Most of the studies are from China and only one from Spain. Although there are many case reports of OM treatments in knee OA from Korea and Europe, their medical environment is difficult to conduct RCTs of a certain scale. Secondly, this study included only RCTs in English, Korean, Chinese and Japanese and it is possible that we have missed out more good quality RCTs for the analysis.

5. Conclusion

Due to the nature of knee OA, which is difficult to conquer with one treatment, studies using complex treatments are increasing. Our study analyzed the RCTs of OM treatment and integrative treatment, and found that single OM treatments, OM and conventional treatment and herbal medicine and HA together might improve the symptoms of knee OA. In the future, based on our study, it is hoped that an effective treatment combination for knee OA will be created. Furthermore, an evidence-based integrative treatment package could be created for each stage of knee OA progression to make a whole clinical pathway or clinical routine practice for knee OA.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Yeon-Cheol Park.

Data curation: Kyeong Ju Park, Bon-Hyuk Goo.

Formal analysis: Jung-Hyun Kim.

Funding acquisition: Yong-Hyeon Baek.

Investigation: Kyeong Ju Park, Jung-Hyun Kim.

Methodology: Yeon-Cheol Park.

Project administration: Yong-Hyeon Baek.

Resources: Yong-Hyeon Baek.

Software: Bon-hyuk Goo, Byung-Kwan Seo.

Supervision: Yong-Hyeon Baek.

Visualization: Bon-Hyuk Goo.

Writing – original draft: Kyeong Ju Park.

Writing – review & editing: Yeon-Cheol Park, Byung-Kwan Seo, Yong-Hyeon Baek.

Abbreviations:

- AEs

- adverse events

- CI

- confidence interval

- HA

- hyaluronic acid injections

- NSAIDS

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- OA

- osteoarthritis

- OM

- oriental medicine

- RCTs

- randomized controlled trials

- SMD

- standardized mean difference

- VAS

- visual analog scale

This research is supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant no. HF20C0014).

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article.

How to cite this article: Park Y-C, Park K-J, Goo B-H, Kim J-H, Seo B-K, Baek Y-H. Oriental medicine as collaborating treatments with conventional treatments for knee osteoarthritis: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2023;102:29(e34212).

Contributor Information

Yeon-Cheol Park, Email: kjpark930111@naver.com.

Kyeong-Ju Park, Email: kjpark930111@naver.com.

Bon-Hyuk Goo, Email: goobh99@naver.com.

Jung-Hyun Kim, Email: dan_mi725@naver.com.

Byung-Kwan Seo, Email: seobk@hanmail.net.

References

- [1].Pavone V, Vescio A, Turchetta M, et al. Injection-based management of osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review of guidelines. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:661805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gu J-H, Kim E, Park Y-C, et al. A systematic review of bee venom acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis. J Korean Med Rehabil. 2017;27:47–60. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Altman R, Asch D, Bloch D, et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1039–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Kim JY, Pham DD. Understanding oriental medicine using a systems approach. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:624304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Li J, Li YX, Luo LJ, et al. The effectiveness and safety of acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis: an overview of systematic reviews. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e16301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Park JM, Lee CK, Kim KH, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of moxibustion treatment for knee osteoarthritis. J Acupunct Res. 2020;37:137–50. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kim JH, Yoon YS, Lee WJ, et al. A systematic review of herbal medicine treatment for knee osteoarthritis. J Korean Med Rehabil. 2019;27:47–60. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lee JH, Yang TJ, Lee DG, et al. The effect of needle-embedding therapy on osteoarthritis of the knee combined with Korean medical treatment: report of five cases. J Korean Acupunct Moxibustion Med Soc. 2014;31:195–204. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Liu JW, Wu YL, Wei W, et al. Effect of warm acupuncture combined with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells transplantation on cartilage tissue in rabbit knee osteoarthritis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021;2021:5523726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ruan A, Wang Q, Ma Y, et al. Efficacy and mechanism of electroacupuncture treatment of rabbits with different degrees of knee osteoarthritis: a study based on synovial innate immune response. Front Physiol. 2021;12:642178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Li Y, Wu F, Wei J, et al. The effects of laser moxibustion on knee osteoarthritis pain in rats. Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg. 2020;38:43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Huang SM, Wu YM, Zhang L, et al. Effect of Gancao Fuzi Decoction on osteoarthritis and proteomics of articular cartilage in rats. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2021;46:661–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gong Z, Liu R, Yu W, et al. Acutherapy for knee osteoarthritis relief in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:1868107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yuan T, Xiong J, Wang X, et al. The effectiveness and safety of moxibustion for treating knee osteoarthritis: a PRISMA compliant systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Res Manag. 2019;2019:2653792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Huang H, Pan J, Yang W, et al. Are kidney-tonifying and blood-activating medicinal herbs better than NSAIDs for knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:9094515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Xiao K, Ma J, Zhu T, et al. Clinical study on the treatment of knee osteoarthritis with traditional acupuncture combined with intra-articular injection of sodium hyaluronate. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27:S223. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhang YS, Wang ZX. Randomized controlled clinical trials for treatment of knee osteoarthritis by warm acupuncture combined with intra-articular injection of sodium hyaluronate. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu. 2011;36:373–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chen N, Wang J, Mucelli A, et al. Electro-acupuncture is beneficial for knee osteoarthritis: the evidence from meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Chin Med. 2017;45:965–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Park YC, Goo BH, Park KJ, et al. Traditional Korean medicine as collaborating treatments with conventional treatments for knee osteoarthritis: a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Res. 2021;14:1345–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, et al. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychol Methods. 2006;11:193–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:401–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cao G, Hu J, Wang C. Clinical efficacy observation of Duhuo Jisheng decoction combined sodium hyaluronate injection in intra-articular cavity injection in treatment of knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. Chin J Exp Tradit Med Formulae. 2013;19:305–8. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Huang W, Wei Q, Zeng J, et al. Effect of DUHUOJISHENG decoction with sodium hyaluronate on the quality of life of patients with knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. Guangdong Med J. 2014;35:2447–50. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Yang M. Oral Gancao Fuzi Decoction combined with injection of sodium hyaluronate in the treatment of 60 patients with knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. Chinese J Trad Med Traum Orthop. 2012;20:9–11. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cai X, Wu W, Li C. Therapeutic observation on acupoint injection plus intracavitary injection of sodium hyaluronate for knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. Shanghai J Acu-mox. 2013;32:747–9. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Fu XM, Huang Y, Lu G, et al. Effect of moxibustion and sodium hyaluronate on the treatment of knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. J Chin Physician. 2010;12:425–6. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Deng J, Chen Y, Wang S. Comparative study of the efficacies of warm needling versus salt moxibustion in treating knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. Shanghai J Acu-mox. 2015;34:243–5. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Miao GD, Jiang ZF, Tian ZJ. The observation of clinical effects of acupuncture on knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. Hebei J Tradit Chin Med. 2014;5:725–6. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sun XQ. Acupoint Injection Therapy for Knee Osteoarthritis Clinical Observation [dissertation]. Accra: Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Vas J, Méndez C, Perea-Milla E, et al. Acupuncture as a complementary therapy to the pharmacological treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;329:1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhao H, Kong J, Lu W, et al. Clinical effects of acupuncture and moxibustion in treating knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. Acta Universitatis Traditionis Medicalis Sinensis Pharmacologiaeque Shanghai. 2013;27:45–7. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhou Y, Li J, Hou W, et al. Clinical observation of moxibustion in treatment of knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. Shanghai J Acu-mox. 2014;33:1086–8. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zhou T, Chen C, Qian Y, et al. Clinical analysis of low-frequency electro-acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. SH J TCM. 2015;49:56–7. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Deng W. Clinical research on Gancao Fuzi decoction in treating osteoarthritis of knee joint [in Chinese]. J Chin Med Mater. 2008;31:1107–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Fan X, Yu Y, Chen R, et al. Observation on therapeutic effect of modified Danggui Sini decoction treating 76 cases of knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. Liaoning J Tradit Chin Med. 2012;39:2184–6. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Wang Z. Analysis of curative effect of oral Bushen huoxue tongluo recipe on knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. China Health Care Nutr. 2017;28:322–3. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Yuan J, Luo C, Huang Y, et al. Clinical study on oral application of self-made Bushen Huoxue Tang for treatment of early knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. J Trad Chin Orthop Trauma. 2017;29:26–32. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zhang JQ, Liu SQ., Liu. “Clinical effectiveness of Bushen huoxue fang for patients with knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. Liaoning J Tradit Chin Med. 2014;41:2339–42. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Zheng T, Xu Z, Xu Z, et al. Clinical effect of Bushen Huoxue prescription on knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. Chin Arch Tradit Chin Med. 2019;37:1506–9. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Dai M, Fang X, Chen H, et al. Clinical study on mild moxibustion for knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. J Acupunct Tuina Sci. 2019;17:62–6. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Huang L, Ji R. Clinical study on the effect of thunder fire moxibustion on VAS and WOMAC scores of patients with knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. Jiangsu J Tradit Chin Med. 2017;49:57–8. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Yuan Q, Guo X, Ha Y, et al. Observations on the therapeutic effect of heat-sensitive point thunder-fire moxibustion on knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. Shanghai J Acu-mox. 2015;34:665–8. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zhang Q, Cao L, Li Z, et al. The clinical effects and safety of moxibustion and celecoxib for osteoarthritis of knee [in Chinese]. Chin J Trad Med Traum Orthop. 2011;19:13–5. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zhang J, Shen Y, Huang G. Clinical observation of moxibustion combined with knee joint rehabilitation for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis [in Chinese]. JCAM. 2015;31:7–9. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Jang S, Kim KH, Sun SH, et al. Characteristics of herbal medicine users and adverse events experienced in South Korea: a survey study [in Korean]. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:4089019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Park JM, Lee JS, Lee EY, et al. A systematic review on thread embedding therapy of knee osteoarthritis [in Korean]. Korean J Acupunct. 2018;35:159–65. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kim JH, Yoon YS, Lee WJ, et al. A systematic review of herbal medicine treatment for knee osteoarthritis [in Korean]. J Korean Med Rehabil. 2019;29:47–60. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Shim JW, Jung JY, Kim SS. Effects of electroacupuncture for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:3485875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72:149–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Korean Acupuncture and Moxibustion Medicine Society. Korean medicine clinical practice guideline for degenerative knee osteoarthritis. Korean Acupunct Moxibust Soc. 2020:1–376. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Manheimer E, Cheng K, Linde K, et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD001977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Chen G, Ye X, Guan Y, et al. Effects of bushen huoxue method for knee osteoarthritis: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e20659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Deng H, Shen X. The mechanism of moxibustion: ancient theory and modern research. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:379291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zhao B, Wang X, Lin Z, et al. A novel sham moxibustion device: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2006;14:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Jung CY, Jang MG, Cho JY, et al. The study of the sham acupuncture for acupuncture clinical trials [in Korean]. J Korean Acupunct Moxibustion Med Soc. 2008;25:77–93. [Google Scholar]

- [57].Kim T-H, Lee MS, Birch S, et al. Plausible mechanism of sham acupuncture based on biomarkers: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:834112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]