Abstract

Background:

Preoperative optimization programs for total joint arthroplasty (TJA) identify and address risk factors to reduce postoperative complications, thereby improving patients’ ability to be safe surgical candidates.

Purpose:

This article introduces preoperative optimization programs and describes the role of orthopaedic nurse navigators. This foundation will be used to produce an article series with recommendations for optimization of several modifiable biopsychosocial factors.

Methods:

We consulted orthopaedic nurse navigators across the United States and conducted a literature review regarding preoperative optimization to establish the importance of nurse navigation in preoperative optimization.

Results:

The responsibilities of nurse navigators, cited resources, and structure of preoperative optimization programs varied among institutions. Optimization programs relying on nurse navigators frequently demonstrated improved outcomes.

Conclusion:

Our discussions and literature review demonstrated the integral role of nurse navigators in preoperative optimization. We will discuss specific risk factors and how nurse navigators can manage them throughout this article series.

Introduction

Recent projections for utilization of total joint replacement in the United States report an increasing demand for primary total joint arthroplasty (TJA), with projected demand for 850,000 total hip arthroplasty (THA) procedures and 3.42 million total knee arthroplasty (TKA) procedures in 2040 (Kurtz et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2019). The greatly increased demand for TJA to treat osteoarthritis (OA) can be attributed in part to increasing prevalence of factors that contribute to the severity of patients’ OA and its accompanying symptoms, including increasing average BMI and age among patient populations (George et al., 2017; Older Americans 2020: Key indicators of well-being, 2020). While TJA can vastly improve quality of life by reducing pain and improving patient-reported function and mobility (Neuprez et al., 2020), it is not without risks. Patient comorbidities such as obesity, uncontrolled diabetes, and smoking are associated with increased postoperative complications such as infection, poor wound healing, cardiac or pulmonary adverse events, and short-term readmissions following TJA (Changulani et al., 2008; Duchman et al., 2015; Harris et al., 2013; MacMahon et al., 2021; Martin et al., 2017; O’Connor et al., 2022; Sabesan, Rankin, & Nelson, 2022; Springer et al., 2019; Wiznia et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2017; Zhang & Jordan, 2010). In addition, social determinants of health, such as socioeconomic status or mental health conditions, may act as barriers to care and confer higher risks of increased length of stay in the hospital after TJA, or contribute to postoperative complications such as infection (Ahn et al., 2020; Gold et al., 2016; Hinman & Bozic, 2008; Lakomkin et al., 2020; Maman et al., 2019; Sabesan, Rankin, & Jimenez, 2022). These biopsychosocial factors can influence patients’ preparedness for TJA and ability to recover from surgery (Bennett et al., 2017; Browne et al., 2014; Gold et al., 2020).

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have transitioned to a bundled payment model for TJA, a reimbursement structure in which costs for hospital visits and services linked to TJA within 90 days following the procedure are reimbursed as one collective episode of care (Salmond & Echevarria, 2017). As return visits and longer hospital stays increase costs of care for one episode but are not additionally reimbursed and thus reduce profit margins, surgeons and hospitals are financially incentivized to reduce postoperative events leading to emergency department (ED) visits or hospital readmission and achieve shortened postoperative hospital stays. Health care institutions may attempt to achieve this by operating on only the healthiest of patients who lack risk factors for complications, which results in the exclusion of patients who have comorbidities and health issues that confer risk of complications. The bundled payment model for total joint arthroplasty, or Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model, is thus a major impetus for the expansion of preoperative optimization programs (Dundon et al., 2016; Karas et al., 2018; Krueger et al., 2020).

Preoperative optimization programs reduce the risk of postoperative complications by taking advantage of the fact that many medical comorbidities and biopsychosocial factors associated with postoperative complications are modifiable conditions that can be addressed preoperatively (Ahn et al., 2019; Dlott et al., 2020; Dlott & Wiznia, 2022; Parsons et al., 2013; Rozell et al., 2016; Ryan et al., 2019; Sau-Man Conny & Wan-Yim, 2016; Weiner et al., 2020). While patient optimization is beneficial to both providers and patients, the implementation of optimization processes has at times led to the exclusion of patients of color, women, patients with Medicaid, and patients with lower incomes from receiving care (Dlott & Wiznia, 2022; Wang et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2021). This exclusion is a risk of implementing preoperative optimization that must be avoided, as several studies have demonstrated that TJA is already underutilized by patients of color and women despite the increased burden of OA among these populations (Cavanaugh et al., 2019; Dlott & Wiznia, 2022; MacFarlane et al., 2018; Salazar et al., 2019; Singh, 2011; Singh et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2021) and that patients of color are less likely to receive high-quality care at high-volume hospitals (Arroyo et al., 2018; Cai et al., 2012). Practices that utilize strict cutoffs such as a body mass index (BMI) below 40 kg/m2, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) below 7.5%, or albumin above 3.5 g/dL are likely to restrict patients from receiving care and worsen disparities (Dlott et al., 2022; Dlott & Wiznia, 2022). Systems must be in place to help patients achieve these preoperative goals so that optimization programs improve care rather than impose exclusionary criteria. As these programs have only recently become part of TJA preoperative care, there are no standardized practices for the proactive management of comorbidities or social determinants of health (Ryan et al., 2019).

The role of the orthopaedic nurse navigator is broad and varies across practice settings. The role includes providing patient care related to TJA by educating, counseling, and guiding patients to prepare them for TJA and the postoperative recovery period. Nurse navigators serve a critical role through direct patient care as well as by coordinating care amongst specialty providers and resources, contributing to shorter hospital stays and decreased ED visit rates postoperatively (Bernstein et al., 2018; Dlott et al., 2020; Fowler et al., 2019; Sawhney et al., 2021; Teng et al., 2021). While preoperative optimization for TJA varies in design across institutions that have begun this practice, these programs are often implemented by orthopaedic nurse navigators. To date, there are no studies specifically analyzing the role and contributions of navigators with regard to specific risk factors addressed as part of orthopaedic preoperative optimization programs. In the absence of clear standards for proactive optimization and the unclear role responsibilities of the orthopaedic nurse navigator facilitating optimization, we sought to identify practices of nurse navigators in preoperative optimization and evidence from the literature to use in developing recommendations for nurse navigators.

This article describes the methodology for the study. Five subsequent articles will present data specific to the role nurse navigators have in preoperative optimization regarding 11 factors linked with poor outcomes (Best et al., 2015; Black et al., 2019; Gwam et al., 2020; Hinman & Bozic, 2008; Weiner et al., 2020) and their disproportionate effect on underserved populations (Gwam et al., 2020; Ihekweazu et al., 2018; Jin et al., 2019; Ponnusamy et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018). These factors are related to individual behavior—smoking, alcohol use, and opioid use, comorbid conditions—diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, malnutrition, mental health and medication management, and social determinant concerns—housing, payer status and affordability. Optimization strategies regarding these factors as identified through our discussions with nurse navigators and a literature review will be incorporated into recommendations for implementing preoperative optimization protocols.

Methods

Nurse Navigator Perspectives

To gather perspectives on the nurse navigator role and examples of current preoperative optimization practices, nurse navigators were contacted through a thread in the Practice Discussions Forum on the National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses (NAON) website for participation in this qualitative study. Individual discussions, conducted over the phone or via video conference, were semi-structured to allow for diversity of responses. Audio recordings of each conversation were created so that the content of each discussion could be documented and revisited.

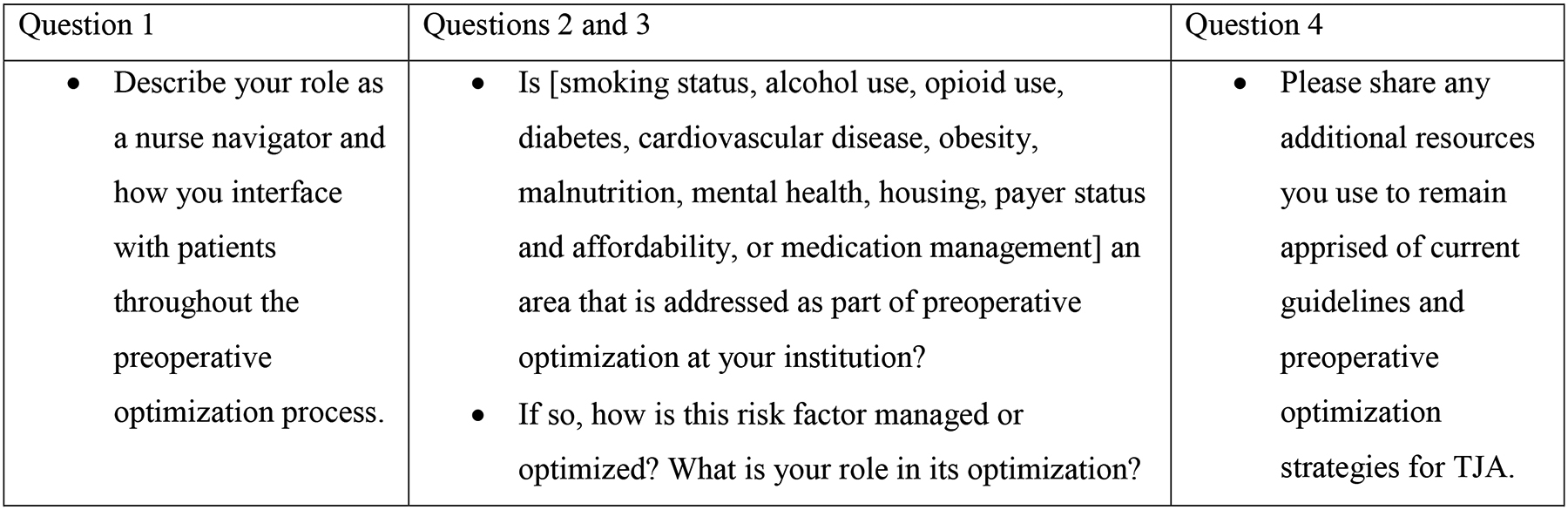

Each nurse navigator was asked 4 standard questions that were developed with the aim of eliciting basic information about the nurse navigator role and preoperative optimization protocols while allowing for specific and detailed responses (Figure 1). These were followed by open-ended questions based on their responses. The standard questions allowed nurse navigators to provide an introduction of their role, describe how they interfaced with patients throughout the preoperative optimization process, and share resources that they relied on throughout the optimization process. Following standard questions with open-ended questions provided the opportunity for nurse navigators to share further details regarding practices such as the administration of screening questionnaires, laboratory tests, patient education, and connection to outside resources of a medical or social nature.

Figure 1.

Standard Questions Asked of Orthopaedic Nurse Navigators.

Responses were organized by thematic elements and subject matter, such that general information about the nurse navigator role and resources referenced by nurse navigators are reported in this article, while content related to specific risk factor optimization processes will be reported in future articles covering the corresponding topics. Due to the qualitative and semi-structured nature of the conversations, it was possible to calculate the rates at which some responses or practices were observed, while others were not amenable to this level of analysis due to infrequency or lack of universal commentary on the subject in question.

Literature Review

We queried the Scopus and Web of Science databases for our literature search. Scopus is a database that is inclusive of Medline and more, while Web of Science includes expanded indexes covering both health sciences and social sciences. We selected these databases with the aim of including articles that would be reflective of a diverse range of disciplines, methodologies, and perspectives. We included all articles available in English that were deemed relevant on the basis of discussion of preoperative optimization or orthopaedic nursing in general or with regard to the eleven domains we discussed with nurse navigators.

The initial search terms in Scopus were “surgery,” “surgical,” “operat-,” “pre-operat-,” “pre-surg-,” “optimiz-,” “hip,” “knee,” “replac-,” “arthroplasty,” and “nurs-.” This search returned a total of 65 results, 24 of which were included after reading titles and abstracts to determine their relevance. The initial search terms in the Web of Science database core collection across the categories of Orthopaedics, Surgery, and General Internal Medicine were “hip,” “knee,” “arthroplasty,” “operat-,” “surg-,” “pre-,” and “optim-.” This search returned 511 results, 25 of which were included after reading titles and abstracts to determine their relevance. Citation chaining from the results of the primary searches was used to find 67 articles related to nurse navigation and specific risk factors. In total, we found 116 relevant articles through our literature search.

Results

Participating Nurse Navigator Practice Settings

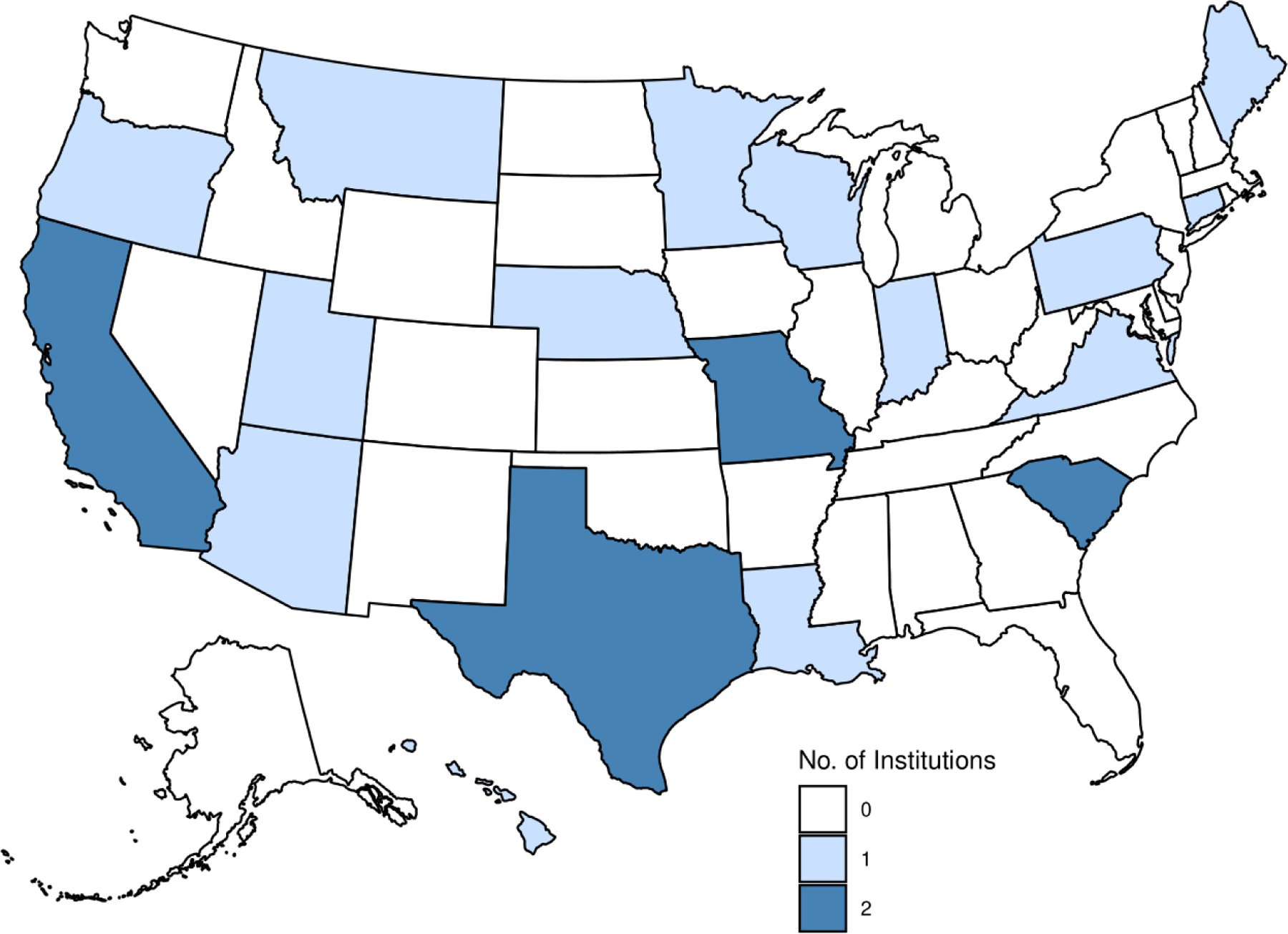

Twenty-five orthopaedic nurse navigators were successfully contacted from 18 states (Figure 2) and employed by a total of 22 health care institutions ranging from ambulatory surgical centers (ASC) to tertiary care centers. The majority of institutions were tertiary care centers (77%) in urban settings (55%) that were not certified by The Joint Commission (55%) (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Geographic Distribution of Institutions Employing Nurse Navigators.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Institutions Employing Nurse Navigators.

| Institution Features | Number of Institutions (n = 22) |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Tertiary Care Center | 16 |

| Critical Access Center* | 4 |

| Ambulatory Surgical Center | 2 |

| Region | |

| Midwest | 6 |

| Northeast | 3 |

| South | 5 |

| West | 8 |

| Setting | |

| Urban | 12 |

| Suburban | 5 |

| Rural | 5 |

| The Joint Commission Hip and Knee Replacement Certification Status | |

| Not Certified | 12 |

| Basic | 4 |

| Advanced | 6 |

Refers to small, rural hospitals providing emergency services and limited outpatient services

Nurse Navigators and Optimization

Nurse navigators were involved in implementation of optimization protocols in some capacity at each institution (Table 2). None of the nurse navigators identified strict requirements for when initial contact must be made, though 72% specified goals for timing of initial contacts with TJA patients that ranged from 1 to 8 weeks prior to surgery. Timing of initial contacts and the length of time allotted for optimization were both reportedly affected by scheduling and cancellation policies, receipt of clearance from patients’ primary care providers (PCP), timing of preoperative testing and patient education sessions, and the structure of the nurse navigator’s role in preoperative optimization. For example, some nurse navigators identified obtaining clearance from PCPs prior to patients being schedule for TJA as part of their role, while others were not involved until they met patients at the education sessions they led a week prior to TJA. However, the timing was not affected by type of surgery, and optimization protocols did not differ in approach between hip and knee arthroplasty patients. Twenty percent of nurse navigators mentioned recent or ongoing efforts to change surgical scheduling to allow more time to facilitate patient optimization. Sixty-four percent of nurse navigators reported that TJA patients at their institutions underwent pre-admission testing (PAT) that included laboratory testing, electrocardiograms (EKG), health questionnaires, and other screenings. While some nurse navigators contacted patients prior to PAT, others only became involved after PAT had been completed. A minority of nurse navigators (32%) met patients in the hospital during the perioperative period.

Table 2.

Nurse Navigator Roles in Preoperative Optimization Design and Implementation.

| Role | Nurse Navigator Involvement N (%) |

|---|---|

| Met individually with patients in perioperative period | 8 (32) |

| Worked with advanced practice providers | 10 (40) |

| Were nurse practitioners | 2 (8) |

| Held preoperative education sessions (joint classes) | 25 (100) |

| Used online or app-based patient education platforms | 7 (28) |

Nurse navigators worked with diverse care teams that included physical therapists, pharmacists, and anesthetists. Forty percent of the nurse navigators that were consulted worked with advanced practice providers (APP). Eight percent of the nurse navigators that were consulted were nurse practitioners (NP).

Each of the nurse navigators that was consulted described preoperative education sessions held at their institutions that were usually referred to as “joint classes.” These classes were taught in person, over the phone, through digital video recordings, or through virtual presentations.

The resources available to nurse navigators to facilitate their roles in optimization varied. Twenty-eight percent of nurse navigators were able to use online or app-based patient education platforms to deliver information, messages, and reminders to patients. Some of these were personalized based on patients’ individual optimization goals. Additionally, some nurse navigators kept a guide of local resources that they could refer patients to, such as durable medical equipment lending libraries, support groups for substance use disorders, or home health agencies. The majority of nurse navigators were not able to refer patients to social work or case management prior to admission because these resources were not available at their institutions. The specific resources that were utilized by nurse navigators for managing each risk factor will be discussed throughout the article series.

Resources and Funding for Developing Optimization Practices

The majority of nurse navigators we spoke to were full-time, salaried employees whose positions were funded through the budget allocated for their orthopaedics department. In other cases, the position originated as part of the institution’s case management department, originally achieved funding as a pilot program with temporary budget or grant funding, or started as a part-time position.

Nurse navigators reported that they found several resources useful in designing, understanding, and implementing preoperative optimization protocols (Table 3). The most frequently referenced resources were from the National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses (NAON) and included conferences, webinars, clinical practice guidelines, and forums. Additionally, Orthopaedic Nursing Journal, The Joint Commission arthroplasty certification guidelines, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, and American Academy of Hip and Knee Surgeons were frequently mentioned. Occasionally, nurse navigators mentioned other specialty associations or publications including resources from the American Society of Anesthesiology, American Pain Society, American College of Surgeons, and the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. Meetings with colleagues at individual institutions were also cited as sources of ideas and guidance for patient optimization.

Table 3.

Outside Resources Referenced by Nurse Navigators.

| Resources* |

|---|

| National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses |

| • Webinars1 |

| • Podcasts2 |

| • Clinical practice guidelines3 |

| American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons |

| • Provider education website citing recent literature4 |

| • Patient education website with learning modules5 |

| • PROMs descriptions and questionnaires6 |

| • Advocacy and education toolkits7 |

| • Clinical practice guidelines8 |

| American Academy of Hip and Knee Surgeons |

| • Provider education podcasts9 |

| • Patient education website10 |

| • Clinical practice guidelines and performance measures11 |

| American Diabetes Association |

| • Lifestyle Change Programs for patients with program locator12 |

| • Diabetes Education Program locator13 |

| • Healthy Living patient resources14 |

| • Diabetic diet meal planning and grocery lists15 |

| • Events and support groups16 |

| • American Diabetes Association Standards of Care slide deck17 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists |

| • Geriatric patient perioperative care guidelines18 |

| • Patient engagement training19 |

| • Pre-anesthesia evaluation guidelines20 |

| The Joint Commission |

| • Performance measures for TJA21 |

| • Review process guide for advanced certification22 |

| • Tobacco treatment resources23 |

| Journal of Arthroplasty |

| • Peer-reviewed, open access research24 |

| • The Knee Society Score for measuring function25 |

| American College of Surgeons |

| • Journal of the American College of Surgeons26 |

| • Pain resources for patients and providers27 |

| • Smoking cessation resources for patients28 |

| • Printable handouts and resources on smoking cessation and medication management for patients29 |

| • Articles and printable handouts for patients on preparing for surgery30 |

| Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery |

| • Peer-reviewed, open access research31 |

| • Podcast summaries of each journal issue32 |

| • Special interest article collections33 |

| Orthopaedic Nursing Journal |

| • Collection of literature on TJA34 |

| Becker’s Hospital Review |

| • Podcasts on orthopaedic surgery, nursing, care coordination, and risk factors35 |

| • Webinars on orthopaedic surgery, nursing, care coordination, and risk factors36 |

Resources are listed in order of how often they were mentioned by nurse navigators

PROM: patient-reported outcome measure, TJA: total joint arthroplasty

Literature Review

Qualitative studies have shown that TJA patients appreciate greater clinical, educational, and social support from their surgical care teams (Goldsmith et al., 2017). Patients have reported that difficulty understanding and managing pain, receiving conflicting information from different providers, and uncertain expectations for the recovery process contribute to their dissatisfaction with the TJA process. The development of nurse navigator positions has been recommended to provide patients with more education and support (Goldsmith et al., 2017). Recently, implementation of preoperative optimization programs driven by nurse navigators have been shown to provide all three types of support—clinical, educational, and social (Dlott et al., 2020). Patients benefit directly and indirectly from working with nurse navigators who are involved in presurgical education, present during the hospital stay, and available as the primary contact for concerns both pre- and postoperatively. This is demonstrated through patient responses to working with a nurse navigator, in which they indicate that having this resource helped them throughout the surgical process and potentially prevented ED visits (Teng et al., 2021). Direct benefits include services such as surgical wound assessment and delivery of clinical information pre- and postoperatively, while indirect benefits include the sense of security and reassurance patients gained from having direct access to a care provider (Teng et al., 2021). The navigator’s availability to communicate through phone calls, e-mail or digital messaging, and in-person meetings creates further opportunities to support patients (Teng et al., 2021). Other aspects of the nurse navigator role include serving as the point of contact to coordinate care between providers, educating patients, and framing patient expectations (Fowler et al., 2019).

Recommendations for improved preoperative optimization often include the introduction or expansion of a nurse navigation model (Fowler et al., 2019; Goldsmith et al., 2017). Some models feature an NP in the navigator role, which affords greater independence for clinical decision-making in the optimization process (Bernstein et al., 2018). Studies have noted the difficulty of quantifying the time and effort nurse navigators spend optimizing patients while acknowledging the importance of their contributions (Krueger et al., 2020; McDonald et al., 2014). In addition, studies involving preoperative optimization may mention nurse navigators without describing how they implement interventions or sharing recommendations for what responsibilities they should hold in the optimization process (Bernstein et al., 2018; Bullock et al., 2017; Carmichael et al., 2022).

Discussion

Discussions with nurse navigators and a literature review revealed diverse ways in which nurse navigators implement preoperative optimization protocols and work within care teams. Nurse navigators often collaborated with care team members beyond orthopaedic surgeons, including anesthesiologists, pharmacists, and physical therapists. Some nurse navigators had greater autonomy as NPs, but this was a minority among the nurse navigators with whom we spoke. Nurse navigators universally utilized joint classes as educational vehicles to prepare patients for TJA. These classes have been demonstrated as a means of achieving cost savings via reduced length of stay and improving functional outcomes in the immediate postoperative period, even when taught outside of the context of preoperative optimization programs (Jones et al., 2022). However, they worked with patients for different lengths of time before TJA and varied in their use of technology to interact with patients. Nurse navigators also referenced a wide array of resources for their own continuing education, including journals and podcasts. Few of these resources were specific to orthopaedic nurses and their role in preoperative optimization. In addition, the existing literature regarding preoperative optimization often discusses the design of preoperative optimization protocols by program directors and surgeons rather than the implementation role of orthopaedic nurses (Adie et al., 2019; Featherall et al., 2018). While nurse navigators do not prescribe treatment and rehabilitation regimens, they provide great value to patients and are integral to protocol development and implementation. Our literature search revealed evidence of the unique benefits of patients receiving care from nurse navigators and provided limited examples of interventions implemented by nurse navigators when optimizing patients. The diversity of responses from nurse navigators we consulted, combined with a lack of detailed description of the nurse navigator role in the literature, reinforces the unstandardized nature of orthopaedic nurse navigation for TJA.

Nurse navigation has only recently been implemented in orthopaedic surgery and no standardized practice models are easily available. Still, it is clear that nurse navigators are uniquely positioned to provide clinical, educational, and social support for TJA patients that improves patient satisfaction and surgical outcomes (Dlott et al., 2020; Goldsmith et al., 2017; Teng et al., 2021).

Conclusion

We consulted orthopaedic nurse navigators across the United States and conducted a literature review to better understand the implementation of preoperative optimization practices and to provide practical suggestions that could be employed by nurse navigators within their institutions. We found that there was variability in the structure of nurse navigator roles and preoperative optimization programs as well as the resources used to guide these programs’ development. However, nurse navigators were consistently regarded as being critical to patient optimization. In subsequent articles in this series, we will discuss optimization of smoking status, alcohol use, opioid use, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, malnutrition, mental health, housing, payer status and affordability, and medication management.

Acknowledgements

This article is part of a series describing contributions of nurse navigators to patient optimization for total hip and knee arthroplasty. This series was developed in coordination with Movement is Life, a group comprised of healthcare professionals whose mission is to eliminate musculoskeletal healthcare disparities. The authors would like to thank the nurse navigators who participated in discussions and provided their perspectives on each of the topics discussed in the series: Paulina Andujo BSN, RN, ONC, Christopher Bautista BSN, RN-BC, Emily Belcher RN, Kerry Boyer MSN, APRN, FNP-C, Pam Cupec BSN, MS, RN, ONC, CRRN, ACM, Madonna Doyle RN, Dawn Ellington MBA, BSN, ONC, Sara Holman RN, MSN, MBA, Diane Marie Jeselskis BSN, RN, ONC, Jillian Knudsen RN, MSN, CMSRN, ONC, CNL, CPHQ, Melissa A. Lafosse RN, ONC, Lyndee Leavitt RN, BSN, ONC, MaryHellen Lezan MS, MSN, APRN, FNP-C, JoAnn Miller-Watts RN, BSN, ONC, Christen Nelson RN, BSN, ONC, Kara Orr MSN, RN, CNL, Misty Robbins RN, Nicole Sarauer APRN, CNS, ONC, Heather Schulte BSN, Kathy Steffensmeier RN, BSN, Ashley Streett MSN, RN, ONC, CCRN, Naomi Tashman RN, BSN, ONC, Maureen Wedopohl BSN, RN, ONC, and Rhyana Whiteley MN, RN, ONC.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Support for the conduct of this research was provided by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. This content does not represent the views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Adie S, Harris I, Chuan A, Lewis P, & Naylor JM (2019). Selecting and optimising patients for total knee arthroplasty. Medical Journal of Australia, 210(3), 135–141. https://doi.org/ 10.5694/mja2.12109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn A, Ferrer C, Park C, Snyder DJ, Maron SZ, Mikhail C, Keswani A, Molloy IB, Bronson MJ, Moschetti WE, Jevsevar DS, Poeran J, Galatz LM, & Moucha CS (2019). Defining and Optimizing Value in Total Joint Arthroplasty From the Patient, Payer, and Provider Perspectives. Journal of Arthroplasty, 34(10), 2290–2296.e2291. 10.1016/j.arth.2019.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn A, Snyder DJ, Keswani A, Mikhail C, Poeran J, Moucha CS, & Kanabar M (2020). The Cost of Poor Mental Health in Total Joint Arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty, 35(12), 3432–3436. 10.1016/j.arth.2020.06.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo NS, White RS, Gaber-Baylis LK, La M, Fisher AD, & Samaru M (2018). Racial/Ethnic and Socioeconomic Disparities in Total Knee Arthroplasty 30- and 90-Day Readmissions: A Multi-Payer and Multistate Analysis, 2007–2014. Population Health Management, 22(2), 175–185. 10.1089/pop.2018.0025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett CG, Lu LY, Thomas KA, & Giori NJ (2017). Joint replacement surgery in homeless veterans. Arthroplasty Today, 3(4), 253–256. 10.1016/j.artd.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DN, Liu TC, Winegar AL, Jackson LW, Darnutzer JL, Wulf KM, Schlitt JT, Sardan MA, & Bozic KJ (2018). Evaluation of a Preoperative Optimization Protocol for Primary Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Patients. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 33(12), 3642–3648. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.arth.2018.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best MJ, Buller LT, Gosthe RG, Klika AK, & Barsoum WK (2015). Alcohol Misuse is an Independent Risk Factor for Poorer Postoperative Outcomes Following Primary Total Hip and Total Knee Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 30(8), 1293–1298. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.arth.2015.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black CS, Goltz DE, Ryan SP, Fletcher AN, Wellman SS, Bolognesi MP, & Seyler TM (2019). The Role of Malnutrition in Ninety-Day Outcomes After Total Joint Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 34(11), 2594–2600. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.arth.2019.05.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne JA, Sandberg BF, D’Apuzzo MR, & Novicoff WM (2014). Depression Is Associated With Early Postoperative Outcomes Following Total Joint Arthroplasty: A Nationwide Database Study. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 29(3), 481–483. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.arth.2013.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock MW, Brown ML, Bracey DN, Langfitt MK, Shields JS, & Lang JE (2017). A Bundle Protocol to Reduce the Incidence of Periprosthetic Joint Infections After Total Joint Arthroplasty: A Single-Center Experience. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 32(4), 1067–1073. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.arth.2016.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Cram P, & Vaughan-Sarrazin M (2012). Are African American Patients More Likely to Receive a Total Knee Arthroplasty in a Low-quality Hospital? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®, 470(4). https://journals.lww.com/clinorthop/Fulltext/2012/04000/Are_African_American_Patients_More_Likely_to.30.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael C, Smith L, Aldasoro E, Gil Salmerón A, Alhambra-Borrás T, Doñate-Martínez A, Seiler-Ramadas R, & Grabovac I (2022). Exploring the application of the navigation model with people experiencing homelessness: a scoping review. Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness, 1–15. 10.1080/10530789.2021.2021363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh AM, Rauh MJ, Thompson CA, Alcaraz J, Mihalko WM, Bird CE, Eaton CB, Rosal MC, Li W, Shadyab AH, Gilmer T, & LaCroix AZ (2019). Racial and ethnic disparities in utilization of total knee arthroplasty among older women. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 27(12), 1746–1754. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.joca.2019.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changulani M, Kalairajah Y, Peel T, & Field RE (2008). The relationship between obesity and the age at which hip and knee replacement is undertaken. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British volume, 90-B(3), 360–363. 10.1302/0301-620x.90b3.19782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlott CC, Metcalfe T, Jain S, Bahel A, Donnelley CA, & Wiznia DH (2022). Preoperative Risk Management Programs at the Top 50 Orthopaedic Institutions Frequently Enforce Strict Cutoffs for BMI and Hemoglobin A1c Which May Limit Access to Total Joint Arthroplasty and Provide Limited Resources for Smoking Cessation and Dental Care. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 10.1097/corr.0000000000002315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlott CC, Moore A, Nelson C, Stone D, Xu Y, Morris JC, Gibson DH, Rubin LE, & O’Connor MI (2020). Preoperative Risk Factor Optimization Lowers Hospital Length of Stay and Postoperative Emergency Department Visits in Primary Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Patients. J Arthroplasty, 35(6), 1508–1515 e1502. 10.1016/j.arth.2020.01.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlott CC, & Wiznia DH (2022). CORR Synthesis: How Might the Preoperative Management of Risk Factors Influence Healthcare Disparities in Total Joint Arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res, 480(5), 872–890. 10.1097/CORR.0000000000002177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchman KR, Gao Y, Pugely AJ, Martin CT, Noiseux NO, & Callaghan JJ (2015). The Effect of Smoking on Short-Term Complications Following Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. JBJS, 97(13), 1049–1058. 10.2106/jbjs.N.01016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundon JM, Bosco J, Slover J, Yu S, Sayeed Y, & Iorio R (2016). Improvement in Total Joint Replacement Quality Metrics: Year One Versus Year Three of the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative. JBJS, 98(23). https://journals.lww.com/jbjsjournal/Fulltext/2016/12070/Improvement_in_Total_Joint_Replacement_Quality.2.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherall J, Brigati DP, Faour M, Messner W, & Higuera CA (2018). Implementation of a Total Hip Arthroplasty Care Pathway at a High-Volume Health System: Effect on Length of Stay, Discharge Disposition, and 90-Day Complications. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 33(6), 1675–1680. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.arth.2018.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler JMS, Stephan A, & Case K (2019). Orthopaedic Nurse Navigator. Orthopaedic Nursing, 38(6), 356–358. 10.1097/nor.0000000000000607 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George J, Klika AK, Navale SM, Newman JM, Barsoum WK, & Higuera CA (2017). Obesity Epidemic: Is Its Impact on Total Joint Arthroplasty Underestimated? An Analysis of National Trends [Article]. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 475(7), 1798–1806. 10.1007/s11999-016-5222-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold HT, Slover JD, Joo L, Bosco J, Iorio R, & Oh C (2016). Association of Depression With 90-Day Hospital Readmission After Total Joint Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 31(11), 2385–2388. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.arth.2016.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold PA, Garbarino LJ, Anis HK, Neufeld EV, Sodhi N, Danoff JR, Boraiah S, Rasquinha VJ, & Mont MA (2020). The Cumulative Effect of Substance Abuse Disorders and Depression on Postoperative Complications After Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty, 35(6s), S151–s157. 10.1016/j.arth.2020.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith LJ, Suryaprakash N, Randall E, Shum J, MacDonald V, Sawatzky R, Hejazi S, Davis JC, McAllister P, & Bryan S (2017). The importance of informational, clinical and personal support in patient experience with total knee replacement: a qualitative investigation. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 18(1), 127. 10.1186/s12891-017-1474-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwam CU, Mohamed NS, Dávila Castrodad IM, George NE, Remily EA, Wilkie WA, Barg V, Gbadamosi WA, & Delanois RE (2020). Factors associated with non-home discharge after total knee arthroplasty: Potential for cost savings? The Knee, 27(4), 1176–1181. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.knee.2020.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AHS, Bowe TR, Gupta S, Ellerbe LS, & Giori NJ (2013). Hemoglobin A1C as a Marker for Surgical Risk in Diabetic Patients Undergoing Total Joint Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 28(8, Supplement), 25–29. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.arth.2013.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinman A, & Bozic KJ (2008). Impact of Payer Type on Resource Utilization, Outcomes and Access to Care in Total Hip Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 23(6, Supplement), 9–14. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.arth.2008.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihekweazu UN, Sohn GH, Laughlin MS, Goytia RN, Mathews V, Stocks GW, Patel AR, & Brinker MR (2018). Socio-demographic factors impact time to discharge following total knee arthroplasty. World J Orthop, 9(12), 285–291. 10.5312/wjo.v9.i12.285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y, Solomon DH, Franklin PD, Lee YC, Lii J, Katz JN, & Kim SC (2019). Patterns of prescription opioid use before total hip and knee replacement among US Medicare enrollees. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 27(10), 1445–1453. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.joca.2019.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones ED, Davidson LJ, & Cline TW (2022). The Effect of Preoperative Education Prior to Hip or Knee Arthroplasty on Immediate Postoperative Outcomes. Orthopaedic Nursing, 41(1). https://journals.lww.com/orthopaedicnursing/Fulltext/2022/01000/The_Effect_of_Preoperative_Education_Prior_to_Hip.3.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karas V, Kildow BJ, Baumgartner BT, Green CL, Attarian DE, Bolognesi MP, & Seyler TM (2018). Preoperative Patient Profile in Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: Predictive of Increased Medicare Payments in a Bundled Payment Model. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 33(9), 2728–2733.e2723. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.arth.2018.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger CA, Austin MS, Levicoff EA, Saxena A, Nazarian DG, & Courtney PM (2020). Substantial Preoperative Work Is Unaccounted for in Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 35(9), 2318–2322. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, & Halpern M (2007). Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 89(4), 780–785. 10.2106/jbjs.F.00222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakomkin N, Hutzler L, & Bosco JA III. (2020). The Relationship Between Medicaid Coverage and Outcomes Following Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review. JBJS Reviews, 8(4). https://journals.lww.com/jbjsreviews/Fulltext/2020/04000/The_Relationship_Between_Medicaid_Coverage_and.4.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacFarlane LA, Kim E, Cook NR, Lee IM, Iversen MD, Katz JN, & Costenbader KH (2018). Racial Variation in Total Knee Replacement in a Diverse Nationwide Clinical Trial. JCR: Journal of Clinical Rheumatology, 24(1). https://journals.lww.com/jclinrheum/Fulltext/2018/01000/Racial_Variation_in_Total_Knee_Replacement_in_a.1.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMahon A, Rao SS, Chaudhry YP, Hasan SA, Epstein JA, Hegde V, Valaik DJ, Oni JK, Sterling RS, & Khanuja HS (2021). Preoperative Patient Optimization in Total Joint Arthroplasty—The Paradigm Shift from Preoperative Clearance: A Narrative Review. HSS Journal®, 18(3), 418–427. 10.1177/15563316211030923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maman SR, Andreae MH, Gaber-Baylis LK, Turnbull ZA, & White RS (2019). Medicaid insurance status predicts postoperative mortality after total knee arthroplasty in state inpatient databases. J Comp Eff Res, 8(14), 1213–1228. 10.2217/cer-2019-0027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JR, Jennings JM, & Dennis DA (2017). Morbid Obesity and Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Growing Problem. JAAOS - Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 25(3). https://journals.lww.com/jaaos/Fulltext/2017/03000/Morbid_Obesity_and_Total_Knee_Arthroplasty__A.3.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald S, Page MJ, Beringer K, Wasiak J, & Sprowson A (2014). Preoperative education for hip or knee replacement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev(5), CD003526. 10.1002/14651858.CD003526.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuprez A, Neuprez AH, Kaux J-F, Kurth W, Daniel C, Thirion T, Huskin J-P, Gillet P, Bruyère O, & Reginster J-Y (2020). Total joint replacement improves pain, functional quality of life, and health utilities in patients with late-stage knee and hip osteoarthritis for up to 5 years. Clinical Rheumatology, 39(3), 861–871. 10.1007/s10067-019-04811-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MI, Burney D 3rd, & Jones LC (2022). Movement is Life-Optimizing Patient Access to Total Joint Arthroplasty: Smoking Cessation Disparities. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 10.5435/jaaos-d-21-00875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Older Americans 2020: Key indicators of well-being. (2020). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Retrieved from https://agingstats.gov/docs/LatestReport/OA20_508_10142020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Parsons G, Jester R, & Godfrey H (2013). A randomised controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of a health maintenance clinic intervention for patients undergoing elective primary total hip and knee replacement surgery. International Journal of Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing, 17(4), 171–179. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijotn.2013.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnusamy KE, Naseer Z, El Dafrawy MH, Okafor L, Alexander C, Sterling RS, Khanuja HS, & Skolasky RL (2017). Post-Discharge Care Duration, Charges, and Outcomes Among Medicare Patients After Primary Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. JBJS, 99(11), e55. 10.2106/jbjs.16.00166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozell JC, Courtney PM, Dattilo JR, Wu CH, & Lee GC (2016). Should All Patients Be Included in Alternative Payment Models for Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty and Total Knee Arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty, 31(9 Suppl), 45–49. 10.1016/j.arth.2016.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan SP, Howell CB, Wellman SS, Attarian DE, Bolognesi MP, Jiranek WA, Aronson S, & Seyler TM (2019). Preoperative Optimization Checklists Within the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Bundle Have Not Decreased Hospital Returns for Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty, 34(7S), S108–S113. 10.1016/j.arth.2018.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabesan VJ, Rankin KA, & Jimenez R (2022). Movement is Life: Optimizing Patient Access to Total Joint Arthroplasty: Housing Security and Discharge Planning Disparities. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 10.5435/jaaos-d-21-00943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabesan VJ, Rankin KA, & Nelson C (2022). Movement Is Life-Optimizing Patient Access to Total Joint Arthroplasty: Obesity Disparities. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 10.5435/jaaos-d-21-00424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar DH, Dy CJ, Choate WS, & Place HM (2019). Disparities in Access to Musculoskeletal Care: Narrowing the Gap: AOA Critical Issues Symposium. JBJS, 101(22), e121. 10.2106/jbjs.18.01106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmond SW, & Echevarria M (2017). Healthcare Transformation and Changing Roles for Nursing. Orthopaedic Nursing, 36(1). https://journals.lww.com/orthopaedicnursing/Fulltext/2017/01000/Healthcare_Transformation_and_Changing_Roles_for.5.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sau-Man Conny C, & Wan-Yim I (2016). The Effectiveness of Nurse-Led Preoperative Assessment Clinics for Patients Receiving Elective Orthopaedic Surgery: A Systematic Review. Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing, 31(6), 465–474. 10.1016/j.jopan.2014.08.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawhney M, Teng L, Jussaume L, Costa S, & Thompson V (2021). The impact of patient navigation on length of hospital stay and satisfaction in patients undergoing primary hip or knee arthroplasty. International Journal of Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing, 41, 100799. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijotn.2020.100799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh JA (2011). Epidemiology of knee and hip arthroplasty: a systematic review. Open Orthop J, 5, 80–85. 10.2174/1874325001105010080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh JA, Lu X, Rosenthal GE, Ibrahim S, & Cram P (2014). Racial disparities in knee and hip total joint arthroplasty: an 18-year analysis of national medicare data. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 73(12), 2107. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh JA, Yu S, Chen L, & Cleveland JD (2019). Rates of Total Joint Replacement in the United States: Future Projections to 2020–2040 Using the National Inpatient Sample. The Journal of Rheumatology, 46(9), 1134. 10.3899/jrheum.170990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer BD, Roberts KM, Bossi KL, Odum SM, & Voellinger DC (2019). What are the implications of withholding total joint arthroplasty in the morbidly obese? The Bone & Joint Journal, 101-B(7_Supple_C), 28–32. 10.1302/0301-620x.101b7.Bjj-2018-1465.R1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng LJ, Goldsmith LJ, Sawhney M, & Jussaume L (2021). Hip and Knee Replacement Patients’ Experiences With an Orthopaedic Patient Navigator: A Qualitative Study. Orthopaedic Nursing, 40(5), 292–298. 10.1097/nor.0000000000000789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang AY, Wong MS, & Humbyrd CJ (2018). Eligibility Criteria for Lower Extremity Joint Replacement May Worsen Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®, 476(12), 2301–2308. 10.1097/corr.0000000000000511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner JA, Adhia AH, Feinglass JM, & Suleiman LI (2020). Disparities in Hip Arthroplasty Outcomes: Results of a Statewide Hospital Registry From 2016 to 2018. J Arthroplasty, 35(7), 1776–1783 e1771. 10.1016/j.arth.2020.02.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiznia DH, Jimenez R, & Harrington M (2021). Movement Is Life-Optimizing Patient Access to Total Joint Arthroplasty: Diabetes Mellitus. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 10.5435/jaaos-d-21-00425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Belay E, Cochrane N, O’Donnell J, & Seyler T (2021). Comorbidity Burden Contributing to Racial Disparities in Outpatient Versus Inpatient Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 29(12), 537–543. 10.5435/JAAOS-D-20-01038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Sun Y, Li G, & Liu J (2017). Is hemoglobin A1c and perioperative hyperglycemia predictive of periprosthetic joint infection following total joint arthroplasty?: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine, 96(51). https://journals.lww.com/md-journal/Fulltext/2017/12220/Is_hemoglobin_A1c_and_perioperative_hyperglycemia.2.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, & Jordan JM (2010). Epidemiology of Osteoarthritis. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 26(3), 355–369. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cger.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

List of Resources from Table 3: Outside Resources Referenced by Nurse Navigators

- AAHKS Amplified. American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons. https://www.aahks.org/subscribe-to-podcast/ (9)

- AAOS Now. (2022). American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. https://www.aaos.org/aaosnow/ (4)

- AAOS Toolkits. (2022). American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. https://www.aaos.org/quality/quality-programs/quality-toolkits/?embed_path=modexm%253DEmbed (7)

- Becker’s Healthcare Podcasts. (2022). Becker’s Healthcare. https://www.beckerspodcasts.com (35)

- Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG). (2022). National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses. https://www.orthonurse.org/Clinical-Resources/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines (3)

- Collection Details: Orthopaedic Nursing. (2022, August 22, 2019). National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses. https://journals.lww.com/orthopaedicnursing/pages/collectiondetails.aspx?TopicalCollectionId=6 (34)

- Community Overview. (2022). American Diabetes Association. https://diabetes.org/get-involved/community (16)

- Diabetes Food Hub. (2022). American Diabetes Association. https://www.diabetesfoodhub.org (15)

- Disease Specific Care Certification: Organization Review Process Guide. (2022). The Joint Commission. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/accred-and-cert/survey-process-and-survey-activity-guide/2022/2022-disease-specific-care-organization-rpg-july-2022.pdf (22)

- Find a Diabetes Education Program. (2022). American Diabetes Association. https://diabetes.org/tools-support/diabetes-education-program (13)

- Healthy Living. (2022). American Diabetes Association. https://diabetes.org/healthy-living (14)

- Home. American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons. https://hipknee.aahks.org (10)

- Home Page: The Journal of Arthroplasty. (2022). Elsevier Inc. https://www.arthroplastyjournal.org (24) [Google Scholar]

- JBJS Open Access. (2022). The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, Inc. https://journals.lww.com/jbjsoa/pages/default.aspx (31)

- JBJS Article Collections. (2022). Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. https://www.jbjs.org/collections.php (33)

- Journal of the American College of Surgeons. (2022). American College of Surgeons. https://journals.lww.com/journalacs/pages/default.aspx (26)

- The Knee Society Score. (2021). The Knee Society. https://www.kneesociety.org/the-knee-society-score (25)

- Lifestyle Change Programs. (2022). American Diabetes Association. https://diabetes.org/tools-support/diabetes-prevention/lifestyle-change-programs (12)

- Lower Extremity Programs – Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs). (2022). American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. https://www.aaos.org/quality/quality-programs/lower-extremity-programs/ (8)

- Mohanty S, Rosenthal RA, Russell MM, Neuman MD, Ko CY, & Esnaola NF Optimal Perioperative Management of the Geriatric Patient: Best Practices Guideline from ACS National Surgical Quality Improvement Program®/American Geriatrics Society [Electronic Article]. https://www.facs.org/media/y5efmgox/acs-nsqip-geriatric-2016-guidelines.pdf (18)

- Operation Brochures for Patients. (2022). American College of Surgeons. https://www.facs.org/for-patients/preparing-for-your-surgery/operation-brochures-for-patients/ (29)

- OrthoInfo - Patient Education. (2021). American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. https://orthoinfo.org (5)

- Patient Reported Outcome Measures: Lower Extremity. (2022). American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. https://www.aaos.org/quality/research-resources/patient-reported-outcome-measures/lower-extremity-performance-measures/ (6)

- Perioperative Surgical Home Patient Engagement Training for Perioperative Care Teams. (2022). American Society of Anesthesiologists. https://www.asahq.org/shop-asa/e022m00w01 (19)

- Podcast Episodes. (2022). The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, Inc. https://journals.lww.com/jbjsjournal/pages/podcastepisodes.aspx?podcastid=4 (32)

- Podcast Series. (2022). National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses. https://www.orthonurse.org/Education/Podcast-Series (2)

- Practice Advisory for Preanesthesia Evaluation: An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. (2012). Anesthesiology, 116(3), 522–538. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823c1067 (20) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Practice Resources. American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons. https://www.aahks.org/practice-resources/ (11)

- Quit Smoking Before Your Operation. (2022). American College of Surgeons. https://www.facs.org/for-patients/preparing-for-your-surgery/quit-smoking/ (28)

- Safe Pain Control: Opioid Abuse and Surgery. (2022). American College of Surgeons. https://www.facs.org/for-patients/safe-pain-control/ (27)

- Slide Deck. (2022). American Diabetes Association. https://professional.diabetes.org/content-page/slide-deck (17)

- Strong for Surgery. (2022). American College of Surgeons. https://www.facs.org/for-patients/strong-for-surgery/ (30)

- Tobacco Measure Resource Links. (May 2022). The Joint Commission. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/measurement/measures/tobacco-treatment/dashboard-resource-links-tob-5_22.pdf (23)

- Total Hip and Knee Replacement. (2022). The Joint Commission. https://www.jointcommission.org/measurement/measures/total-hip-and-knee-replacement/ (21)

- Webinars. (2022). Becker’s Healthcare. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/upcoming-webinars.html (36)

- Webinars. (2022). National Association of Orthopaedic Nurses. https://www.orthonurse.org/Education/Webinars (1)