Abstract

The main protease of SARS-CoV-2, , is a dimeric enzyme that is indispensable to viral replication and presents an attractive opportunity for therapeutic intervention. Previous reports regarding the key properties of and its highly similar SARS-CoV homologue conflict dramatically. Values of the dimeric and enzymic differ by 106- and 103-fold, respectively. Establishing a confident benchmark of the intrinsic capabilities of this enzyme is essential for combating the current pandemic as well as potential future outbreaks. Here, we use enzymatic methods to characterize the dimerization and catalytic efficiency of the authentic protease from SARS-CoV-2. Specifically, we use the rigor of Bayesian inference in a Markov Chain Monte Carlo analysis of progress curves to circumvent the limitations of traditional Michaelis–Menten initial rate analysis. We report that SARS-CoV-2 forms a dimer at pH 7.5 that has and is capable of catalysis with , , and . We also find that enzymatic activity decreases substantially in solutions of high ionic strength, largely as a consequence of impaired dimerization. We conclude that is a more capable catalyst than appreciated previously, which has important implications for the design of antiviral therapeutic agents that target .

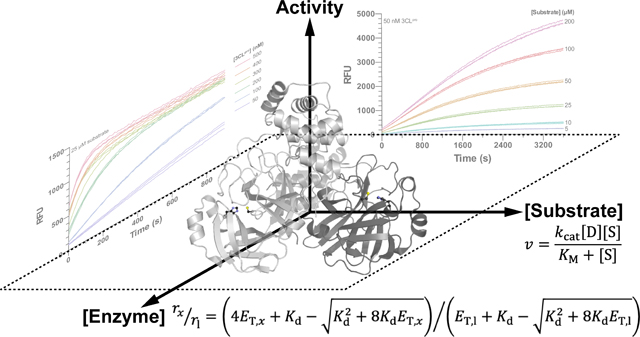

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), first emerged in Wuhan, China in December 2019.1,2 In addition to causing 770 million infections and 7.0 million deaths,3 this public health crisis has disrupted the global economy and significantly impaired the physical and mental health of billions of people worldwide. Significant progress in mitigating the perpetuation of the pandemic has been achieved through the development of vaccines, neutralizing antibody treatments, and other antiviral therapeutics to stunt viral transmission and improve the prognosis of infected individuals.4–8

The trimeric spike glycoprotein (S protein) present on the surface of the coronavirus virion, which is responsible for docking to the ACE2 receptor of host cells and facilitating membrane fusion with the host cell as the causative mechanism of infection, has been an attractive target in the development of these therapeutics.9 Although vaccines and therapeutics targeting the S protein have been developed, selective pressure exerted on the virus can result in S protein mutations that alter epitopes that are targeted by antibodies, dampening therapeutic efficacy.10,11 This problem is exemplified by the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants with reduced inhibition by vaccine-stimulated neutralizing antibodies and/or therapeutic antibody treatment.12,13 It is evident that complementary strategies are necessary to combat SARS-CoV-2.

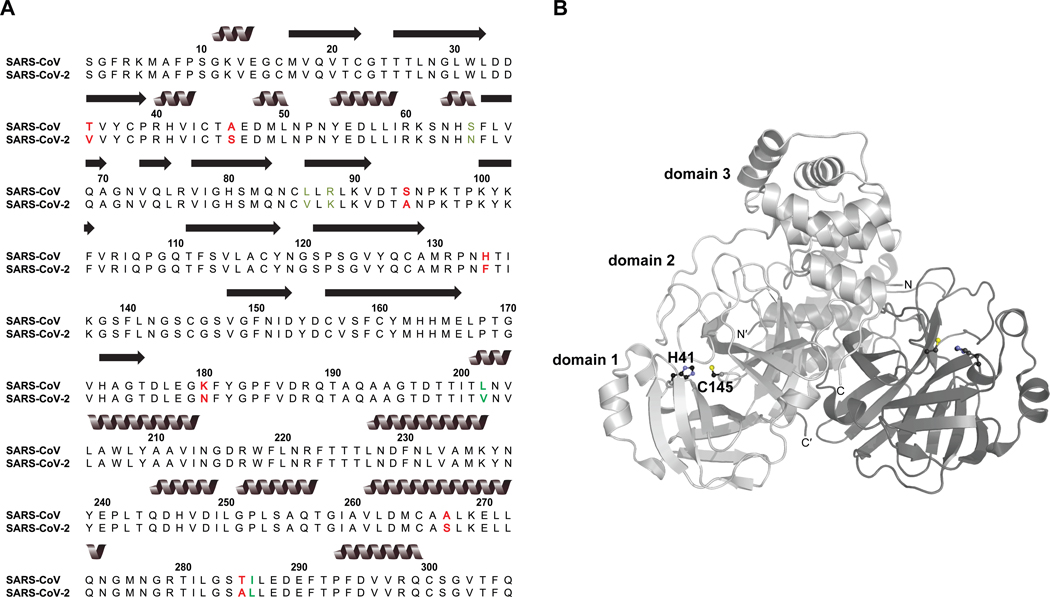

An alternative target for therapeutic intervention is the chymotrypsin-like SARS-CoV-2 3C-like main protease .7,14 Following viral attachment to the host cell ACE2 receptor and membrane fusion, injected viral RNA is rapidly translated to produce polyproteins pp1a and pp1ab. These polyproteins yield 16 nonstructural proteins (NSPs) that are necessary for virion maturation, and the main protease (contained within pp1a) is principally responsible for 11 of the cleavage events to liberate the NSPs.15,16 Thus, interference with proteolysis can significantly impede viral replication. Notably, SARS-CoV-2 has 96% sequence identity with the cognate main protease of SARS-CoV, the etiological agent of the 2003 SARS epidemic, and the majority of the 12 nonidentical residues either consist of conservative mutations or occur in nonstructured regions of the two proteins (Figure 1A). This strict conservation supports the extrapolation of many observations made for SARS-CoV to the homologous SARS-CoV-2 .17

Figure 1.

SARS-CoV-2 sequence and structure. (A) ClustalW sequence alignment of SARS-CoV-2 (UniProt accession ID: P0DTD1, positions 3264–3569) with the SARS-CoV homologue (UniProt accession ID: P0C6X7, positions 3241–3546). Conservative mutations are identified by green font; nonconservative mutations are identified by red font. (B) SARS-CoV-2 structure (PDB ID: 6Y2E). Homodimer protomers are distinguished by light and dark gray. Catalytic dyad residues at the interface of domains 1 and 2 are depicted in ball-and-stick form, and the dyad and domains of one protomer are labeled. The image was prepared with PyMOL software.

SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 are each a homodimer of 306-residue subunits arranged perpendicular to one another (Figure 1B). Each subunit consists of three domains. Domains I and II each possess a -barrel structure and collectively form the active site cleft, whereas domain III is a globular, -helix rich region implicated in dimerization.4 Unlike the canonical chymotrypsin catalytic triad Ser/Cys–His–Asp/Glu possessed by many coronavirus proteases, possesses a catalytic dyad of Cys145 and His41.16,18 In addition, a bound water molecule hydrogen bonds to His41 and could be the third member of a pseudo catalytic triad.19 Dimerization is strictly necessary to establish catalytic competency; empirical and computational evidence shows that the N-terminal residues of one protomer (the “N-finger”) weave between domains I and II of the other protomer, completing the active site of the latter and properly orienting cleft residues to prevent steric clash with polypeptide substrates.19,20 In particular, the N terminus of one protomer hydrogen bonds with Glu166 of the other protomer to prevent the latter from blocking access to the active site, and the main chain of Ser1′ hydrogen bonds with the main chain of Phe140A to properly orient the oxyanion loop of which Phe140 is a part.19 This loop is responsible for stabilizing the tetrahedral transition state of the nascent acyl-enzyme intermediate, and a collapsed active site has been observed in monomeric as a result of missing interprotomer interactions.19,21 Intriguingly, data suggest that the two active sites of dimeric are asymmetric and that only one is active at any given moment (i.e., half-site reactivity).18,20,22

As a result of the strict conservation between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 , as well as the greater body of research available for the former protease, it is tempting to rely on enzymological values reported for SARS-CoV when studying the SARS-CoV-2 homologue. Unfortunately, studies of each enzyme report key parameters that differ by many orders of magnitude. For example, reported values of the catalytic efficiency range from ~102 to nearly 105 M−1 s−1, even within a series of similar substrates; likewise, reported values of the dimer dissociation constant, , vary from low nanomolar to high micromolar. These studies are confounded by the use of enzymic constructs bearing artificial affinity tags (which could inhibit the association of subunits), suboptimal substrates unable to occupy the enzymic binding pocket C-terminal to the scissile bond, assay conditions that impair activity, and enzymatic activity assays that lack sensitivity. The design and assessment of inhibitors rely on the robust characterization of SARS-CoV-2 catalysis.

Here, we circumvent these many experimental limitations and employ a novel Bayesian analytical technique to facilitate the interpretation of enzymology from data obtained during the full time course of the reaction, that is, a “progress curve”. We report that SARS-CoV-2 is an undervalued catalyst. The dimer has a value in the low-nanomolar regime. The authentic enzyme is highly active with a measured catalytic efficiency that is larger than reported previously. We also find that SARS-CoV-2 activity is attenuated by increased ionic strength, likely due to the disruption of dimerization. We hypothesize that the use of artificial enzymic constructs and the inclusion of high NaCl concentrations in assay buffers led to the preponderance of low and high values in the literature. Our findings provide a foundation for applied research, including the design of anti-SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics that disrupt the activity of a key viral enzyme.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Reagents.

The preparation and analysis of and its substrate are described in the Supporting Information.

Kinetics Assay.

Standard assays of were performed in 50 mM HEPES–NaOH buffer, pH 7.5, containing DTT (1 mM) at 25 °C. The concentration of FRET substrate varied from 5 to 200 μM, and the concentration of varied from 25 to 500 nM, as indicated. Substrate cleavage was initiated by the addition of an equal volume of 2× enzyme to 2× substrate. Fluorescence was monitored at and over 15–60 min, as indicated. Nonlinear regression analyses to eqs S12 and S14 were performed with Prism v6.0 software (GraphPad Software).

Michaelis–Menten Analysis of Kinetic Data.

Progress curves were analyzed for initial rate Michaelis–Menten plots using the ICEKAT software of Smith and co-workers.23 Fluorescence raw data were converted into product concentration by equating the asymptotic end point fluorescence intensity of each progress curve to the initial substrate peptide concentration. Then, ICEKAT software was used with the default setting “maximize slope magnitude” to process the data (n = 6 substrate concentrations × 3 technical replicates) independently at each concentration of .

EKMCMC Analysis of Kinetic Data.

Full progress curves were also analyzed with the EKMCMC R algorithm of Kim and co-workers.24,25 Fluorescence raw data were converted into product concentrations by equating the asymptotic endpoint fluorescence intensity of each progress curve to the initial substrate peptide concentration. EKMCMC algorithm was used to process the dataset (n = 6 substrate concentrations × 3 technical replicates) independently at each concentration of . For the enz_data field within EKMCMC, the concentration of catalytically competent dimer at each was estimated by using the previously determined value. The EKMCMC algorithm was run using the total QSSA model with an initial guess of 1000 μM (K_M_init = 1000, K_M_m = 1000), a burn-in period of 1000 samples (burn = 1000), a thinning rate of 1/30 (jump = 30), and an effective 3000 MCMC iterations (nrepeat = 3000).

RESULTS

Production, Purification, and Characterization of .

We used heterologous expression in Escherichia coli to produce a SARS-CoV-2 fusion construct composed of protease with an N-terminal GST tag and C-terminal 6×-His tag, as described by Hilgenfeld and co-workers;26 semimature with an autolyzed GST tag was apparent after 5 h of induction with IPTG (Figure S1A). Protein of >98% purity and with a molecular mass approximately corresponding to that of authentic was obtained following affinity chromatography, proteolytic removal of the His tag, and anion-exchange chromatography (Figure S1B).

To confirm the purity and accuracy of our produced , we used Q–TOF mass spectrometry (Figure S2A,B). We observed only one protein species with an observed mass of 33,796.8 Da. This mass corresponds to that of authentic (UniProt accession ID: P0DTD1, positions 3264–3569) bearing no purification tags (Δm = 5.6 ppm). We assayed the thermostability of our recombinant using DSF. We observed a single thermal denaturation event at (mean ± SE, n = 4) (Figure S2C). Our values generally agree with previous reports of 54.2 and 55.0 °C, which were reported for SARS-CoV-2 with a C-terminal His tag.16,27 appears to be a stable protein at ambient and physiological temperatures, and our results suggest that a C-terminal His tag does not impair the inherent thermostability of .

Design, Synthesis, and Characterization of a Substrate.

Due to the large influence of substrate sequence on protease catalytic efficiency, we sought to choose an optimal consensus sequence for our substrate. Following a literature review of known and putative SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 peptide substrates, we chose the candidate sequence ATLQ↓SGNA, where the cleavage site is indicated by “↓”. Residues preceding the scissile bond in our candidate substrate integrate those that recognizes in its in vivo auto-cleavage from the pp1a polyprotein: AVLQ at the NSP4– interface, VTFQ at the –NSP6 interface. Likewise, residues P1′ and P2′ in our candidate substrate recapitulate the N-terminal residues of , again mimicking the NSP4– interface. Our candidate substrate accommodates many of the structural features observed in SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 substrate-binding subsites: the strict requirement for a P1 Gln; the hydrophobic S2 and S4 subsites corresponding to a P2 Leu and P4 Ala; the shallow, solvent-exposed S3 subsite corresponding to a P3 Thr; access of the S1′ subsite occupant (corresponding to a P1′ Ser) to form a hydrogen bond with the Cys145–His41 catalytic dyad and thereby stabilize a reactive Cys145 thiolate; and the broad binding pocket of the S3′ subsite that accommodates a P3′ Asn.28–33 To enable the detection of substrate cleavage, we appended EDANS-conjugated Glu and DABCYL-conjugated Lys to the N- and C-terminal ends of the peptide as a FRET pair; we also appended an N- and C-terminal Arg to increase aqueous solubility. The structure of our substrate R–E(EDANS)–ATLQSGNA–K(DABCYL)–R is shown in Figure S3A.

The synthesis of the substrate by solid-phase peptide synthesis was successful, as judged by analytical HPLC and MALDI–TOF mass spectrometry. A single major peak was observed by HPLC with coincident absorbance at the peptide bond, EDANS FRET donor, and DABCYL FRET acceptor wavelengths (Figure S3B). The mass of the synthesized peptide was as expected (Figure S3C,D).

Dimerization of .

The dimerization dissociation constant was assessed from enzymological data. Because only dimeric is catalytically competent with one functional active site per dimer,20 the maximal reaction velocity is a function of the dimer concentration :

| (1) |

with

| (2) |

where is the molar concentration of total protomer. Eq 2 results from the definition of the dissociation constant and mass balance for .34 Enzymological assay of dimerization was necessary prior to the determination of the catalytic parameters and in order to calculate the latter set of parameters with a known concentration of dimer.

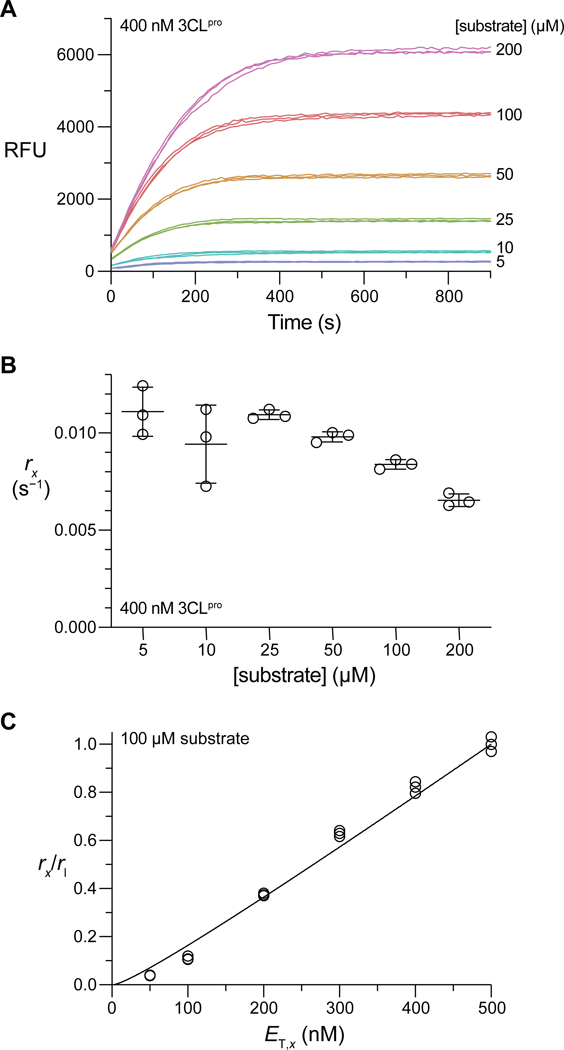

We first confirmed that our substrate is suitable for assays of activity with observable turn-on of fluorescence in 50 mM HEPES–NaOH buffer, pH 7.5, containing DTT (1 mM) at 25 °C (Figure 2A). With sufficient enzyme, all reactions approached completion within the observed timeframes. (For all progress curves, see Figure S5.) We noticed that the asymptotic end point fluorescence was directly proportional to substrate concentration at low concentrations, but this linear relationship broke down at higher peptide concentrations. This dichotomy is indicative of the inner filter effect, a well-documented phenomenon in FRET assays.15,35,36 We characterized the extent of the inner filter effect in our assay by measuring the fluorescence of a fixed concentration of the R–E(EDANS)–ATLQ product in the presence of varied substrate concentrations (Figures S4 and S6). We found that the fluorescence of the product significantly attenuates due to the inner filter effect when [substrate] > 50 μM. As such, we transformed progress curve fluorescence intensity values to product concentration by equating the asymptotic end point fluorescence intensity of each progress curve to the initial substrate peptide concentration. The extent of the inner filter effect is constant over the course of a single enzymatic reaction, as the concentration of FRET donor and acceptor does not change regardless of whether they are parts of one substrate peptide or two separate product peptides.35,36

Figure 2.

(A) Representative progress curves for substrate cleavage by 400 nM in 50 mM HEPES–NaOH buffer, pH 7.5, containing DTT (1 mM) at 25 °C. (B) Fitted values from nonlinear regression of the progress curves in panel A to eq S12. (C) Normalized values for the 100 μM substrate data set as a function of .

We assayed substrate cleavage with 25–500 nM . For the Michaelis–Menten regime where [substrate] << , the decrease in substrate concentration over time approximately follows an exponential decay with a pseudo first-order rate constant (for further details, see: eqs S7–S13):

| (3) |

This rate constant is a parameter of an approximate expression for product fluorescence over time (see: eq S12), enabling its estimation by nonlinear regression of the progress curves in Figures 2A and S5. For a given , should be constant with respect to substrate concentration; a decrease in the fitted with an increase in substrate concentration indicates that the assumption [substrate] << has become invalid and allows for a qualitative estimate of . A representative plot of fitted values is shown in Figure 2B. (All plots are shown in Figure S7.)

For each substrate concentration, values were normalized to the pseudo first-order rate constant corresponding to the largest concentration, . From eq 2 and 3, this ratio is

| (4) |

and is a function of with one fittable constant, . Data for each substrate concentration were fitted to eq 4 to derive the value of (Figures 2C and S8). Within the substrate range 10–100 μM, where the pseudo first-order approximation appears valid and raw fluorescence intensities were adequately sensitive (Figures S5 and S7), the fitted values were highly consistent and resulted in , which is the mean ± SE (n = 4). Successful fitting to eq 4 indicates that is catalytically competent only in the dimeric state.

Catalysis by .

We analyzed the progress curves using both a traditional Michaelis–Menten (MM) strategy and a Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach.24 We note that traditional MM analysis requires a range of substrate concentrations of up to ~10 ×. Although we do not know the value of a priori, the pseudo first-order approximation used to determine the dimerization enabled us to estimate the concentration regime in which exists. Based on our observation that the pseudo first-order approximation begins breaking down as substrate concentrations exceed 100 μM, we predicted that 10 × is near millimolar concentration and cannot be feasibly assayed due to the magnitude of the inner filter effect at these concentrations along with limited substrate solubility at these concentrations (cf: Figure S6). The Bayesian MCMC method (vide infra) analyzes data from progress curves and thus does not require high substrate concentrations; we used MM analyses, when possible, to corroborate our MCMC results.

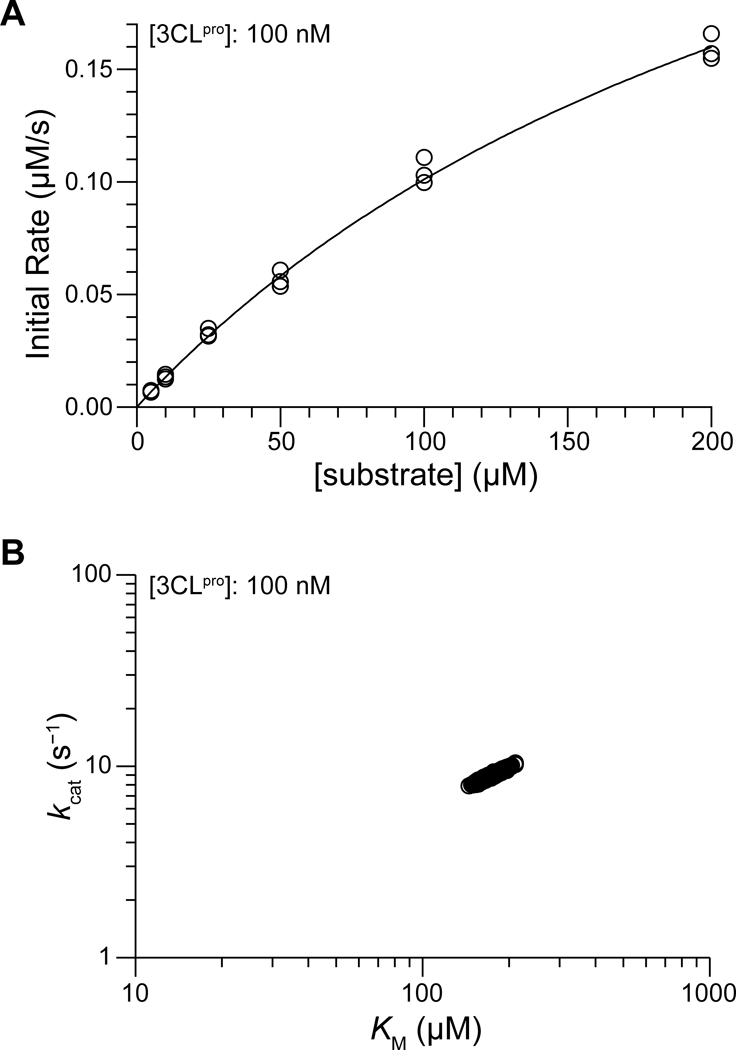

We determined Michaelis–Menten initial reaction rates from progress curves in a semiautomated manner using ICEKAT in order to minimize the introduction of bias.23 We restricted initial rate analyses to ≤ 200 nM, as the faster reactions at higher concentrations resulted in insufficient data to accurately determine initial rates (e.g., compare the linear region of the progress curves for high and low in Figure S5). A representative MM plot for 100 nM is shown in Figure 3 (plots for all are shown in Figure S9), and best-fit kinetic parameters are listed in Table 1. Our MM initial rate analysis estimates that the catalytic efficiency of with our FRET substrate is / = (2.6 ± 0.6) × 104 M−1 s−1 (mean ± SE, n = 4).

Figure 3.

Representative analytical graphs for catalysis by 100 nM in 50 mM HEPES–NaOH buffer, pH 7.5, containing DTT (1 mM) at 25 °C. (A) Michaelis–Menten plot, produced using ICEKAT.23 (B) Bayesian posterior sample distributions (n = 3000 estimates) for and , predicted using EKMCMC.

Table 1.

Steady-State Kinetic Parameters for Catalysis of the Cleavage of R–E(EDANS)–ATLQ↓SGNA–K(DABCYL)–R by .

| [] (nM) | [dimer] (nM)a | Michaelis–Menten analysis (ICEKAT) | Bayesian analysis (EKMCMC) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (s−1)c | (μM)c | (s−1) | (μM) | ||

| 25 | 7.2 | 3.81 | 367 | 3.01 | 240 |

| 50 | 16.8 | 7.26 | 296 | 7.21 | 235 |

| 100 | 37.7 | 10.1 | 278 | 8.93 | 173 |

| 200 | 81.9 | 9.61 | 221 | 10.6 | 205 |

| 300 | 127.5 | ND | ND | 13.2 | 242 |

| 400 | 173.7 | ND | ND | 11.7 | 223 |

| 500 | 220.4 | ND | ND | 14.5 | 282 |

| 7.7 ± 1.4b | 291 ± 30b | 9.8 ± 1.5b | 229 ± 13b | ||

Dimer concentration calculated from total enzyme concentration using eq 2 with .

Mean ± SE (n = 4 for ICEKAT, n = 7 for EKMCMC).

ND, not determined.

Due to the limitations of traditional Michaelis–Menten analysis (e.g., the lack of a clear plateau in the hyperbolic MM curves in Figure S9), we chose to employ the alternate analytical strategy of direct Bayesian inference from progress curves. This strategy does not necessitate that substrate concentrations greatly exceed the value of and can be executed using the public-domain R computational package EKMCMC.24–25 This strategy also maximizes the experimental efficiency and analytical rigor by utilizing full progress curves in lieu of initial rate plots derived therefrom. We independently performed a Bayesian analysis of the progress curves for each concentration of assayed (i.e., each plot in Figure S5). A representative plot of the Bayesian posterior sample distributions for and at 100 nM is shown in Figure 3, and posterior sample plots are shown for all enzyme concentrations in Figure S10. All posterior samples of and (n = 3000 per concentration) were confirmed to exhibit convergence, possess low autocorrelation between iterative estimates, and yield unimodal, bell-shaped sample distributions, as advised by the developers of the algorithm (Figures S11 and S12).24,25 The sample mean values at each concentration of are listed in Table 1; because the Bayesian analytical strategy is not limited to initial reaction rates, we were able to analyze the progress curves at all concentrations. The Bayesian-estimated catalytic efficiency of with our FRET substrate is / = (4.3 ± 0.7) ×104 M−1 s−1 (mean ± SE, n = 7).

Given that the Bayesian analytical strategy is not subject to the requirements of the Michaelis–Menten initial rate strategy, as well as the fact that the MM initial rate plots only just began to approach hyperbolic asymptotes within the substrate concentrations used, we believe that the Bayesian-determined catalytic parameters are a more reliable representation of the catalytic efficiency of SARS-CoV-2 . Comparing the results of the Michaelis–Menten strategy and the Bayesian inference one, it is evident that the use of a more limited analytical technique alone induces a 2-fold underestimate of the catalytic efficiency of .

Effect of Ionic Strength on .

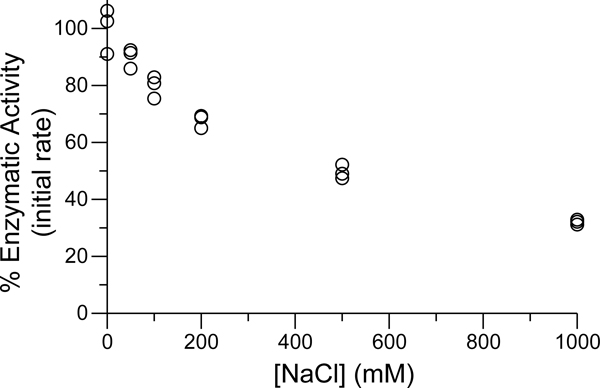

Motivated by reports that catalysis by SARS-CoV is highly sensitive to solution ionic strength,15,37,38 we investigated the impact of NaCl concentration on enzymatic activity. Initially, we assayed the cleavage of 100 μM substrate by 50 nM in 50 mM HEPES–NaOH buffer, pH 7.5, containing DTT (1 mM) and NaCl (0–1000 mM). All buffers were adjusted to constant pH after salt dissolution. We chose these enzyme and substrate concentrations because of the extended period of linear catalytic activity (see: Figure S5), which facilitates the determination of the initial enzymatic reaction rate. As shown in Figure 4, we observed attenuation of the initial reaction rate with increased ionic strength, with a nearly 40% loss of enzymatic activity at 200 mM NaCl.

Figure 4.

Influence of NaCl concentration on catalysis by in 50 mM HEPES–NaOH buffer, pH 7.5, containing DTT (1 mM) at 25 °C. Reaction rates are normalized to those of assays run in the absence of added NaCl.

We attempted to repeat the enzymological determination of the dimerization for 50 mM HEPES–NaOH buffer, pH 7.5, containing NaCl (150 mM) and DTT (1 mM), as an increased would result in a lower concentration of dimer at any given concentration of total and would explain our observation of lower initial reaction rates in the presence of NaCl (see: eqs 1 and 2). Our analytical strategy was unsuccessful, however, due to the emergence of a pronounced lag phase in the time course of the enzymatic reaction (data not shown). The length of this lag phase, which increased with lower enzyme or substrate concentrations, resulted in overestimated pseudo first-order rate constants (). Accordingly, we were unable to accurately determine the dimerization by enzymatic means in the presence of added NaCl. Importantly, although the length of the lag phase is dependent on and substrate concentrations, it does not appear to be as significantly influenced by the concentrations of NaCl used for the initial rates reported in Figure 4. We propose plausible causes for the emergence of the lag phase below.

DISCUSSION

Reliable data on the enzymology of the protease of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 are necessary for our understanding of its catalysis and for therapeutic intervention. To catalog the state of extant data, we surveyed the literature and collated published data (Tables S1 and S2). Values for both the catalytic efficiency and dimerization dissociation constant vary substantially, with the latter parameter spanning nearly 6 orders of magnitude. The variation in values is particularly concerning because the analysis of enzymological data relies on knowing the concentration of the dimer, which manifests catalysis. Indeed, at least one of the publications in our survey assumed that the analytical concentration of enzyme was identical to the concentration of active catalyst ().29 This assumption is incorrect because differs from to an extent that depends on the value of as described in eq 2, which accounts for the half-site reactivity of .18,20,22

Some variability in the reported values of is understandable. For example, there is no singular substrate that must be used for determining activity. The enzyme processes viral polyproteins at multiple, distinct cleavage sites and is thus somewhat promiscuous.33 Still, nearly all data are for the cleavage of an LQ↓SG peptide bond (Table S1), as in our substrate. There is also a slight variability in solution conditions (pH, salt concentration, and temperature) that could affect enzymatic catalysis. We note that rather than determining the optimal enzyme substrate or constraining ourselves to endogenous substrate sequences, we chose a rationally designed substrate sequence to balance catalysis with other experimental considerations that have likely limited other studies, such as peptide solubility.

Of greater concern are assay factors that would impair the dimerization of , which would correspondingly decrease the concentration of catalytically competent enzyme and lead to erroneous normalization of enzymological data when determining the catalytic efficiency.28,17 The use of artificial purification tags is expected to impede dimerization, as several key interprotomer interactions occur at terminal residues in . Aside from simply assembling the dimeric state, the terminal residues of one protomer structure contribute to the active site of its sibling protomer and are critical to catalysis.17,19 Several studies have reported that N- and C-terminal truncations of significantly disrupt dimerization and/or catalysis,39,40 and at least one study has shown that the introduction of exogenous terminal tags as small as two residues leads to a large decrease in catalytic activity.41 The alteration of termini likely disrupts key interactions, including the Ser1⋯Phe140′ hydrogen bonds and the Arg4⋯Glu290′ salt bridges (where “′” denotes the sibling protomer and these interactions occur reciprocally between the two protomers). The loss of these interactions leads to a collapsed oxyanion hole and obviates catalytic activity by impeding stabilization of the negatively charged tetrahedral transition state during proteolysis.17,19 The C terminus is also important for stabilizing the dimeric state, as demonstrated by several C-terminal single-point mutants that exhibited decreased catalytic activity and an apparent molecular mass corresponding to monomeric .42 Studies entailing assays of with unnatural termini report some of the lowest values (Table S1). Surprisingly, several of the reported constructs most predisposed to dimerization include terminal tags (Table S2). This observation could be the result of variable analytical techniques used to measure , some of which lack the sensitivity needed to detect nanomolar dissociation constants. For a single analytical technique employed within one study, the impact of terminal tags on dimerization is apparent. For example, Liang, Wang, and co-workers found that the addition of tags led to a ≤50-fold increase in the measured value of .43 We believe that the assay of native is indispensable to the understanding of its intrinsic catalytic efficiency.

Another, albeit lesser, consideration is the concentration of salt used in the assay buffers. As shown in Figure 4, there is a significant decrease in activity upon the addition of NaCl to the assay buffer, with a nearly 2-fold decrease in catalytic efficiency with 200 mM NaCl.44 Similar results were reported by Chang and co-workers for the SARS-CoV homologue, where 150 mM NaCl induced partial dissociation of the dimer.37 Mangel and co-workers also report that NaCl disrupts SARS-CoV activity, though they observed a large activity loss (80%) at only 100 mM NaCl.38 Due to other variable assay parameters, relationships between [NaCl] and or are difficult to distinguish in the data listed in Tables S1 and S2, respectively, but we do note that for the SARS-CoV-2 homologue, the three lowest reported catalytic efficiencies all included NaCl in the assay buffer.

Increases in ionic strength likely diminish the free energy of Coulombic interactions, both between protomers of the dimer and between the enzyme and its bound substrate. Mangel and co-workers postulated that high ionic strength disrupts the interactions of Glu166 and a peptidic substrate.38 Similarly, Shi and Song observed that the inclusion of NaCl in the assay buffer led to decreased catalytic activity without perturbing dimerization, suggesting that ionic strength disrupts substrate binding or catalysis itself.42 Conversely, as previously noted, Chang and co-workers observed that NaCl disrupted the quaternary structure of .37 Ferreira and Rabeh reported that SARS-CoV-2 exhibits reduced thermodynamic stability when [NaCl] ≥ 100 mM without dependency on the precise salt concentration, which they attributed to the disruption of salt bridges.16 Velazquez-Campoy, Abian, and co-workers observed a subtle decrease in the thermostability of SARS-CoV-2 in the presence of 150 mM NaCl.27 Given the aforementioned salt bridges that are responsible for stabilizing the dimer, we believe that increased ionic strength would interfere with dimerization as well as catalysis. Because of the likelihood that NaCl disrupts catalysis either directly or through its effect on enzyme dimerization, we preemptively chose to omit NaCl in our standard activity assay to assess the maximal catalytic efficiency.

The dimerization of can be induced by a substrate.45 A key residue in this process appears to be Glu166, which has been implicated in providing structure to the oxyanion hole. In the monomeric state of , Glu166 blocks access to the critical S1 substrate-binding subsite; but in the dimeric state, Glu166 interacts instead with Ser1′, revealing the S1 subsite and stabilizing the oxyanion hole. Intriguingly, molecular dynamics simulations suggest some conformational flexibility of Glu166 in the monomeric state, with the residue precluding access to the S1 subsite most of but critically not all of the time.19 The series of events for substrate cleavage by are often thought of as being (1) dimerization → (2) subsite revelation → (3) substrate binding → (4) catalysis, but Chou and co-workers propose that the series is (1) subsite revelation → (2) substrate binding → (3) dimerization → (4) catalysis.45 Moreover, they suggest that Glu166 forms a hydrogen bond with Asn142, stabilizing an adjacent 310-helix to maintain a collapsed oxyanion hole. Upon substrate binding, Glu166 instead interacts with the substrate P1 glutamine and Ser1′, disrupting the Glu166⋯Asn142 hydrogen bond and causing conformational changes that stabilize an intact oxyanion hole.45,46 Thus, the binding of substrate to a monomer could stabilize Glu166 in a conformation that facilitates dimerization, forms an oxyanion hole, and enables catalysis. The lag phase that we observed in activity assays with 150 mM NaCl might be a consequence of disrupted dimerization, and the length of the lag phase might be variable because the extent of substrate-induced dimerization is dependent upon substrate concentrations.

CONCLUSIONS

Our analyses of have relied on core principles of enzymology. (1) We characterize the authentic enzyme, without exogenous residues (Figure S2). (2) We designed our peptidic substrate to accommodate the structural features of the substrate subsites and to position the pendant FRET moieties far from the scissile bond so as not to disrupt binding or catalysis. (3) We assayed activity in the absence of NaCl, mitigating the disruption to dimerization (Figure 4). (4) We characterized the magnitude of the inner filter effect (Figure S6) and accounted for its consequences in our analyses. (5) We determined the value of through enzymological assays, which are more sensitive than other methods (e.g., analytical gel filtration chromatography or SDS–PAGE). (6) We determined the catalytic parameters and for our substrate through two means: initial rate (i.e., Michaelis–Menten) analysis and progress curve (i.e., Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo) analysis. The latter strategy maximizes data utility and unshackles enzymology from the empirical limitations of Michaelis–Menten techniques.

Our work reveals that is a catalyst that is more capable than reported previously. Moreover, is much more predisposed toward dimerization than is appreciated, having a value in the nanomolar range. These findings define the landscape for the design of protease inhibitors for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 infection and could facilitate efforts to combat the COVID-19 pandemic and potentially assist in the prevention of future coronavirus-based outbreaks.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A pGEX-6P-1 plasmid encoding SARS-CoV-2 was a kind gift from Professor Rolf Hilgenfeld (University of Lübeck). The authors are grateful to JoLynn B. Giancola for assistance with Q–TOF and MALDI–TOF mass spectrometry, Jinyi Yang for assistance with MALDI–TOF mass spectrometry, and Dr. Nile S. Abularrage for assistance with analytical HPLC.

Funding

E.C.W. was supported by a Graduate Research Fellowship from the NSF. This work was supported by Grants R35 GM148220 and R21 AI17166301 (NIH).

ABBREVIATIONS

- CoV

coronavirus

3C-like protease

- DABCYL

4-((4-(dimethylamino)phenyl)-azo)-benzoic acid

- DSF

differential scanning fluorimetry

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDANS

5-((2-aminoethyl)amino)-naphthalene-1-sulfonic acid

- FRET

Förster resonance energy transfer

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- ICEKAT

Interactive Continuous Enzyme Kinetics Analysis Tool

- IPTG

isopropyl -d-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- Q–TOF

quadrupole–time-of-flight

- MALDI–TOF

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight

- MCMC

Markov Chain Monte Carlo

- MM

Michaelis–Menten

- NSP

nonstructural protein

- SARS

severe acquired respiratory syndrome

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/xxxx.xxxxxxx.

Additional experimental procedures, surveys of literature values (Tables S1 and S2), and substrate analytical data, and progress curves and analyses thereof (Figures S1–S12) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Evans C. Wralstad, Department of Chemistry, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, United States

Jessica Sayers, Department of Chemistry, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, United States.

Ronald T. Raines, Department of Chemistry, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Zhou P; Yang X-L; Wang X-G; Hu B; Zhang L; Zhang W; Si H-R; Zhu Y; Li B; Huang C-L; Chen H-D; Chen J; Luo Y; Guo H; Jiang R-D; Liu M-Q; Chen Y; Shen X-R; Wang X; Zheng X-S; Zhao K; Chen Q-J; Deng F; Liu L-L; Yan B; Zhan F-X; Wang Y-Y; Xiao G-F; Shi Z-L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Zhu N; Zhang D; Wang W; Li X; Yang B; Song J; Zhao X; Huang B; Shi W; Lu R; Niu P; Zhan F; Ma X; Wang D; Xu W; Wu G; Gao GF; Tan W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med 2020, 382, 727–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Reported by the World Health Organization Coronavirus Dashboard: https://covid19.who.int., Accessed August 30, 2023.

- (4).Jin Z; Du X; Xu Y; Deng Y; Liu M; Zhao Y; Zhang B; Li X; Zhang L; Peng C; Duan Y; Yu J; Wang L; Yang K; Liu F; Jiang R; Yang X; You T; Liu X; Yang X; Bai F; Liu H; Liu X; Guddat LW; Xu W; Xiao G; Qin C; Shi Z; Jiang H; Rao Z; Yang H. Structure of from COVID-19 virus and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature 2020, 582, 289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Krammer F. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in development. Nature 2020, 586, 516–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Hoffman RL; Kania RS; Brothers MA; Davies JF; Ferre RA; Gajiwala KS; He M; Hogan RJ; Kozminski K; Li LY; Lockner JW; Lou J; Marra MT; Mitchell LJ; Murray BW; Nieman JA; Noell S; Planken SP; Rowe T; Ryan K; Smith III GJ; Solowiej JE; Steppan CM; Taggart B. Discovery of ketone-based covalent inhibitors of coronavirus 3CL proteases for the potential therapeutic treatment of COVID-19. J. Med. Chem 2020, 63, 12725–12747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).de Vries M; Mohamed AS; Prescott RA; Valero-Jimenez AM; Desvignes L; O’Connor R; Steppan C; Devlin JC; Ivanova E; Herrera A; Schinlever A; Loose P; Ruggles K; Koralov SB; Anderson AS; Binder J; Dittmann M. A comparative analysis of SARS-CoV-2 antivirals characterizes inhibitor PF-00835231 as a potential new treatment for COVID-19. J. Virol 2021, 95, e01819–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hwang Y-C; Lu R-M; Su S-C; Chiang P-Y; Ko S-H; Ke F-Y; Liang K-H; Hsieh T-Y; Wu H-C. Monoclonal antibodies for COVID-19 therapy and SARS-CoV-2 detection. J. Biomed. Sci. (London, U. K.) 2022, 29, 1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Sternberg A; Naujokat C. Structural features of coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: Targets for vaccination. Life Sci. 2020, 257, 118056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Weisblum Y; Schmidt F; Zhang F; DaSilva J; Poston D; Lorenzi JCC; Muecksch F; Rutkowska M; Hoffmann H-H; Michailidis E; Gaebler C; Agudelo M; Cho A; Wang Z; Gazumyan A; Cipolla M; Luchsinger L; Hillyer CD; Caskey M; Robbiani DF; Rice CM; Nussenzweig MC; Hatziioannou T; Bieniasz PD. Escape from neutralizing antibodies by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variants. eLife 2020, 9, e61312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Li R; Liu J; Zhang H. The challenge of emerging SARS-CoV-2 mutants to vaccine development. J. Genet. Genomics 2021, 48, 102–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Gupta RK; Topol EJ. COVID-19 vaccine breakthrough infections. Science 2021, 374, 1561–1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Planas D; Saunders N; Maes P; Guivel-Benhassine F; Planchais C; Buchrieser J; Bolland W-H; Porrot F; Staropoli I; Lemoine F; Péré H; Veyer D; Puech J; Rodary J; Baele G; Dellicour S; Raymenants J; Gorissen S; Geenen C; Vanmechelen B; Wawina-Bokalanga T; Martí-Carreras J; Cuypers L; Sève A; Hocqueloux L; Prazuck T; Rey FA; Simon-Loriere E; Bruel T; Mouquet H; André E; Schwartz O. Considerable escape of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron to antibody neutralization. Nature 2022, 602, 671–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Morse JS; Lalonde T; Xu S; Liu WR. Learning from the past: Possible urgent prevention and treatment options for severe acute respiratory infections caused by 2019-nCoV. ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 730–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Grum-Tokars V; Ratia K; Begaye A; Baker SC; Mesecar AD. Evaluating the 3C-like protease activity of SARS-coronavirus: Recommendations for standardized assays for drug discovery. Virus Res. 2008, 133, 63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ferreira JC; Rabeh WM. Biochemical and biophysical characterization of the main protease, 3-chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLpro) from the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV 2. Sci. Rep 2020, 10, 22200–22200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Suárez D; Díaz N. SARS-CoV-2 main protease: A molecular dynamics study. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2020, 60, 5815–5831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Durdagi S; Dağ Ç; Dogan B; Yigin M; Avsar T; Buyukdag C; Erol I; Ertem FB; Calis S; Yildirim G; Orhan MD; Guven O; Aksoydan B; Destan E; Sahin K; Besler SO; Oktay L; Shafiei A; Tolu I; Ayan E; Yuksel B; Peksen AB; Gocenler O; Yucel AD; Can O; Ozabrahamyan S; Olkan A; Erdemoglu E; Aksit F; Tanisali G; Yefanov OM; Barty A; Tolstikova A; Ketawala GK; Botha S; Dao EH; Hayes B; Liang M; Seaberg MH; Hunter MS; Batyuk A; Mariani V; Su Z; Poitevin F; Yoon CH; Kupitz C; Sierra RG; Snell EH; DeMirci H. Near-physiological-temperature serial crystallography reveals conformations of SARS-CoV-2 main protease active site for improved drug repurposing. Structure 2021, 29, 1382–1396.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Tan J; Verschueren KHG; Anand K; Shen J; Yang M; Xu Y; Rao Z; Bigalke J; Heisen B; Mesters JR; Chen K; Shen X; Jiang H; Hilgenfeld R. pH-Dependent conformational flexibility of the SARS-CoV main proteinase (Mpro) dimer: Molecular dynamics simulations and multiple X-ray structure analyses. J. Mol. Biol 2005, 354, 25–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Chen H; Wei P; Huang C; Tan L; Liu Y; Lai L. Only one protomer is active in the dimer of SARS 3C-like proteinase. J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281, 13894–13898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Amamuddy OS; Verkhivker GM; Bishop ÖT. Impact of early pandemic stage mutations on molecular dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2020, 60, 5080–5102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Yang H; Yang M; Ding Y; Liu Y; Lou Z; Zhou Z; Sun L; Mo L; Ye S; Pang H; Gao GF; Anand K; Bartlam M; Hilgenfeld R; Rao Z. The crystal structures of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus main protease and its complex with an inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2003, 100, 13190–13195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Olp MD; Kalous KS; Smith BC. ICEKAT: An interactive online tool for calculating initial rates from continuous enzyme kinetic traces. BMC Bioinf. 2020, 21, 186–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Choi B; Rempala GA; Kim JK. Beyond the Michaelis–Menten equation: Accurate and efficient estimation of enzyme kinetic parameters. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 17018–17018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Hong H; Choi B; Kim JK. Beyond the Michaelis–Menten: Bayesian inference for enzyme kinetic analysis. Methods Mol. Biol 2022, 2385, 47–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Zhang L; Lin D; Sun X; Curth U; Drosten C; Sauerhering L; Becker S; Rox K; Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved -ketoamide inhibitors. Science 2020, 368, 409–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Abian O; Ortega-Alarcon D; Jimenez-Alesanco A; Ceballos-Laita L; Vega S; Reyburn HT; Rizzuti B; Velazquez-Campoy A. Structural stability of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and identification of quercetin as an inhibitor by experimental screening. Int. J. Biol. Macromol 2020, 164, 1693–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Anand K; Ziebuhr J; Wadhwani P; Mesters JR; Hilgenfeld R. Coronavirus Main Proteinase (3CLpro) Structure: Basis for Design of Anti-SARS Drugs. Science 2003, 300, 1763–1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Lee J; Worrall LJ; Vuckovic M; Rosell FI; Gentile F; Ton A-T; Caveney NA; Ban F; Cherkasov A; Paetzel M; Strynadka NCJ. Crystallographic structure of wild-type SARS-CoV-2 main protease acyl-enzyme intermediate with physiological C-terminal autoprocessing site. Nat. Commun 2020, 11, 5877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Ramos-Guzmán CA; Ruiz-Pernía JJ; Tuñón I. Unraveling the SARS-CoV-2 main protease mechanism using multiscale methods. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 12544–12554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Kneller DW; Phillips G; Weiss KL; Pant S; Zhang Q; O’Neill HM; Coates L; Kovalevsky A. Unusual zwitterionic catalytic site of SARS-CoV-2 main protease revealed by neutron crystallography. J. Biol. Chem 2020, 295, 17365–17373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).MacDonald EA; Frey G; Namchuk MN; Harrison SC; Hinshaw SM; Windsor IW. Recognition of divergent viral substrates by the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. ACS Infect. Dis 2021, 7, 2591–2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Koudelka T; Boger J; Henkel A; Schönherr R; Krantz S; Fuchs S; Rodríguez E; Redecke L; Tholey A. N-Terminomics for the identification of in vitro substrates and cleavage site specificity of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Proteomics 2021, 21, e2000246-e2000246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34). [A primer on using progress curves to determine the value of for a homodimeric enzyme with half-sites reactivity is provided on pages S20–S22 of the Supporting Information.]

- (35).Liu Y; Kati W; Chen C-M; Tripathi R; Molla A; Kohlbrenner W. Use of a fluorescence plate reader for measuring kinetic parameters with inner filter effect correction. Anal. Biochem 1999, 267, 331–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Palmier MO; Van Doren SR. Rapid determination of enzyme kinetics from fluorescence: Overcoming the inner filter effect. Anal. Biochem 2007, 371, 43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Chou CY; Chang H-C; Hsu W-C; Lin T-Z; Lin C-H; Chang G-G. Quaternary structure of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus main protease. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 14958–14970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Graziano V; McGrath WJ; DeGruccio AM; Dunn JJ; Mangel WF. Enzymatic activity of the SARS coronavirus main proteinase dimer. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 2577–2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Chen S; Chen L; Tan J; Chen J; Du L; Sun T; Shen J; Chen K; Jiang H; Shen X. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 3C-like proteinase N terminus is indispensable for proteolytic activity but not for enzyme dimerization. J. Biol. Chem 2005, 280, 164–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Goyal B; Goyal D. Targeting the dimerization of the main protease of coronaviruses: A potential broad-spectrum therapeutic strategy. ACS Comb. Sci 2020, 22, 297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Xue X; Yang H; Shen W; Zhao Q; Li J; Yang K; Chen C; Jin Y; Bartlam M; Rao Z. Production of authentic SARS-CoV with enhanced activity: Application as a novel Tag-cleavage endopeptidase for protein overproduction. J. Mol. Biol 2007, 366, 965–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Shi J; Song J. The catalysis of the SARS 3C-like protease is under extensive regulation by its extra domain. FEBS J. 2006, 273, 1035–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Hsu M-F; Kuo C-J; Chang K-T; Chang H-C; Chou C-C; Ko T-P; Shr H-L; Chang G-G; Wang AHJ; Liang P-H. Mechanism of the maturation process of SARS-CoV 3CL protease. J. Biol. Chem 2005, 280, 31257–31266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).We attempted to use our enzymological strategy to measure the value of in the presence of increasing [NaCl]. The emergence of a lag phase in the progress curves, however, obviated a curve-fit, estimate of , and subsequent estimate of by the application of eq 4.

- (45).Cheng S-C; Chang G-G; Chou C-Y. Mutation of Glu166 blocks the substrate-induced dimerization of SARS coronavirus main protease. Biophys. J 2010, 98, 1327–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Suárez D; Díaz N. SARS-CoV-2 main protease: A molecular dynamics study. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2020, 60, 5815–5831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.