Abstract

Evidence is emerging that the process of immune aging is a mechanism leading to autoimmunity. Over lifetime, the immune system adapts to profound changes in hematopoiesis and lymphogenesis, and progressively restructures in face of an ever-expanding exposome. Older adults fail to generate adequate immune responses against microbial infections and tumors, but accumulate aged T cells, B cells and myeloid cells. Age-associated B cells are highly efficient in autoantibody production. T-cell aging promotes the accrual of end-differentiated effector T cells with potent cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory abilities and myeloid cell aging supports a low grade, sterile and chronic inflammatory state (inflammaging). In pre-disposed individuals, immune aging can lead to frank autoimmune disease, manifesting with chronic inflammation and irreversible tissue damage. Emerging data support the concept that autoimmunity results from aging-induced failure of fundamental cellular processes in immune effector cells: genomic instability, loss of mitochondrial fitness, failing proteostasis, dwindling lysosomal degradation and inefficient autophagy. Here, we have reviewed the evidence that malfunctional mitochondria, disabled lysosomes and stressed endoplasmic reticula induce pathogenic T cells and macrophages that drive two autoimmune diseases, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and giant cell arteritis (GCA). Recognizing immune aging as a risk factor for autoimmunity will open new avenues of immunomodulatory therapy, including the repair of malfunctioning mitochondria and lysosomes.

Keywords: Immune aging, T cell aging, autoimmune disease, rheumatoid arthritis, giant cell arteritis

1. Introduction

Autoimmune diseases are multifactorial, complex diseases that can affect every organ system in the body. Common denominators include: (1) occur in genetically predisposed hosts that are exposed to environmental challenges; (2) require a breakdown of immune tolerance; (3) produce tissue damage through inappropriate inflammation. Despite these common denominators, autoimmune diseases have distinctive features, indicative of fundamental differences in pathogenic mechanisms. Distinguishing clinical patterns may be attributed to organ specificity, but a fundamental differentiator is the absence or presence of autoantibodies. While the loss of self-tolerance occurs spontaneously in autoimmune patients, cancer immunotherapy leverages the iatrogenic induction of such breakdown to enhance antitumor immunity. The target of cancer immunotherapy are co-inhibitory checkpoints, which can be blocked via monoclonal antibodies to unleash anti-tumor T cell responses. Frequently, cancer treatment with immune checkpoint blockers induces immune-related adverse events, tissue-damaging inflammatory disease in the skin, the gut, the lung, the muscle, endocrine organs, etc. Evidence for the key role of autoantigens has come from recent studies defining shared T cell clonotypes in the tumor and in tissue inflammatory lesions that recognize autoantigens co-expressed in tumors and normal cells [1, 2]. These data emphasize the critical function of immune checkpoints in determining protective and pathogenic autoreactivity.

Most autoimmune diseases have a defined age window at which the risk of clinically relevant inflammatory disease is highest, possibly reflecting the accumulation of environmental exposures. On the other hand, the immune system undergoes striking changes with progressive age, pointing towards immune aging as a critical risk factor for autoimmune disease. Aging of the immune system has been linked to declining immune protection, partially due to failing lymphopoiesis (immunosenescence). Counterintuitively, immune aging is associated with a propensity for heightened inflammatory responses, mostly through activation of innate immunity (inflammaging). Age-associated T cells and B cells are now recognized as specialized subsets that have increasing prevalence with age and accumulate in patients with autoimmune and autoinflammatory disease, where they may function as pathogenic driver cells [3, 4].

Here, we will review two autoimmune diseases in which the process of immune aging has a pivotal role in disease risk and phenotype, and in which aged T cells and antigen-presenting cells (APC) drive pathogenesis. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a disease associated with premature immune aging, in which malfunctioning T cells render the host susceptible to destructive tissue inflammation during midlife. Giant Cell Arteritis (GCA) is an inflammatory vasculopathy of the aorta and large arteries, which occurs during the 6–8th decade of life and is mediated by antigen-presenting cells (APC) that have lost expression of inhibitory checkpoint ligands.

2. Aging of T cells, B cells and macrophages

The field of aging-related restructuring of the immune system is rapidly evolving, and recent discoveries have advanced our understanding of cell surface phenotypes, transcriptional signatures and functional patterns of aged T cells, B cells and myeloid cells. T cells and B cells are substantially affected by the process of aging [5–9], mostly due to declining lymphocyte replenishment. The involution of the thymus, which is the primary organ responsible for producing effective, self-tolerant and self-restricted T cells, is a notable characteristic of immune aging [10]. In humans, thymic function decreases sharply during adolescence and early adulthood [11]. Since the production of new T cells is entirely reliant on the thymus, individuals above the age of 30 years depend mainly on post-thymic T cell homeostatic proliferation as the primary means of generating new T cells [12]. The rate of T cell turnover in humans stays consistent throughout adulthood, indicating extrathymic generation of most T cells, even in young adults [13]. Conversely, in advanced age, T cell proliferation rises due to increasing attrition and failing replacement, finally leading to frank lymphopenia [14]. The number of naïve T cells declines in both absolute and relative terms as individuals get older, most likely due to the inability to sustain naivety in homeostatically proliferating cells. Although this decline is only minor for naïve CD4+ T cells, it is particularly noticeable for naïve CD8+ T cells, even in healthy older adults [15]. Accordingly, the decline in absolute numbers of naïve CD8+ T cells is one of the most robust biomarkers of T-cell aging. If cellular quiescence cannot be preserved, naïve T cells differentiate and become part of the memory T cell population. Accelerated differentiation of older CD8+ T cells results in expansion of the memory pool and of a subset of fully differentiated T cells [15]. Accumulation of terminally differentiated effector T cells is more pronounced in CD8+ T cells compared to CD4+ T cells, but in the setting of chronic inflammatory disease, enddifferentiated CD4+ T cells accumulate prematurely in the blood and in inflamed tissue sites [16–18]. Known as terminally differentiated effector memory T cells (TEMRA), these cells have a unique cell surface phenotype: re-expression of CD45RA, loss of CD28 and CD27 expression. In older individuals, the CD8+ compartment can contain >50% of TEMRAs, which are expanded at the expense of central memory and normal effector cells. In line with being chronically stimulated antigen-experienced memory T cells, TEMRAs often include clonally expanded populations. One of the antigens implicated in driving TEMRA expansion is cytomegalovirus (CMV) [19]. In essence, TEMRA expansion reflects chronic antigenic stimulation, including pathogens and autoantigens.

Like T cells, the differentiation of naïve B cells into memory subsets steadily progresses over lifetime, imposed by continuous antigen expose [20]. The levels of B cell activating factor (BAFF), an essential factor for maintaining the naive B cell lineage decreases, undermining the influx of newly generated B cells. Thus, aging leads to expansion in memory B cells, which possess a more limited range of B cell antigen receptors [21]. A typical feature of immune aging is the increase in age-associated B cells (ABC), a population enriched for characteristic autoantibody specificities [3]. ABCs are higher in autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases and rely on TLR7 or TLR9 signals for their formation and activation [22]. It has long been known that older individuals are likely to carry autoantibodies [23]. Rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies and anti-cardiolipin antibodies were present in 14%, 31% and 51%, respectively, of healthy,>80-year-old individuals, while such antibodies were detected in only 2% of the middle-aged population [24].

In addition to decreased production of T cells and B cells, the functional intactness of lymphocytes may also decrease with progressive age. Three areas of functional decline have received attention: deterioration of mitochondrial function; disturbed proteostasis and dysfunctional signal transduction. In human naïve CD4+ T cells, diminished T cell receptor signaling, and expansion capacity have been linked to age-related loss of miR-181, a key microRNA that regulates dual specific phosphatase 6 (DUSP6) expression and activity [25]. Despite insufficient TCR signaling, aged CD4+ T cells have high transcriptional activity and secret a range of mediators, mostly pro-inflammatory cytokines. This functional status may be identified as a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [26, 27]. Specifically, the secretion of certain cytokines, e.g., Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), by “old” cells may contribute to inflammaging, a state of chronic, low-level inflammation that occurs in aging adults even in the absence of infection [28, 29]. Recent data suggest that T cells actively participate in the process of inflammaging [30, 31]. Specifically, T cells with dysfunctional mitochondria due to deficiency in mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) develop impaired lysosomal function and accelerate senescence and inflammaging [31, 32]. These studies mechanistically link bioenergetics, proteostasis and T cell function, particularly in the context of aging T cells. Epigenetic studies in naive CD4+ T cells from older adults have provided a molecular framework for the bias of older T cells to differentiate into short-lived pro-inflammatory effector T cells instead of long-lived memory T cells [33, 34]. These data fit into the concept that T cell aging is a doubled edged sword: loss of protective immune responses, gain in insufficiently controlled pro-inflammatory responses.

Two recent concepts have further developed the understanding of T cell aging. First, chronic antigenic stimulation, such as in chronic infection or in a tumor carrying host, can lead to T cell exhaustion, a state defined as the progressive loss of effector functions and memory characteristics and high and sustained inhibitory receptor expression; a state best understood for CD8+ T cells during chronic viral infection or cancer [35–37]. Attempts to prevent or reverse T cell exhaustion have led to the insight that chronic stimulation may drive CD8+ T cells either into exhaustion or into terminally differentiated effector status [38]. Support for the hypothesis that exhaustion may not be inevitable comes from studies that have probed functional competence of T cells in a vaccination model [39]. By priming T cells in vivo and then transferring expanded T cells to new mice, the authors have tested the competency of T cells through 51 successive immunizations. In this setting, T cells remain fully competent through repetitive immunizations, possess extraordinary population expansion capacity, and have longevity far beyond their organismal lifespan. These data identify T cells as exceptional cells, endowed with the ability to live over extended time periods and have expansion capacity unlike other somatic cells. Unless exposed to harmful conditions, T cells should never reach the end of their expansion capacity and should have natural protection from exhaustion and senescence.

As individuals age, the functional responsiveness of B cells also decreases [21]. When activated, older B cells may have difficulties inducing the critical transcription factor E47, resulting in a lack of adequate induction of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) - the enzyme responsible for class switching and somatic hypermutation. Consequently, antibody avidity in older individuals may decline and predispose the host to less efficient antibody-mediated protection [40]. In the influenza immunization model, the generation of memory B cells is maintained, but antibody responses are impaired [41]. Precise mechanisms of how B cell aging affects the immunocompetence of the aging host require further investigation.

Surprisingly few studies have investigated the impact of the aging process on macrophages (Mⱷ). This is understandable, given that bone-marrow derived monocytes are relatively short lived and that longer living tissue-resident Mⱷ are difficult to study in humans. Neutrophils have a very short half-life of only 19 hours in circulation [42]. Classical monocytes leave the bone marrow after a postmitotic period of 1.6 days and circulate for another day, before they transition into intermediate and non-classical monocytes that live for an additional 4–7 days [43]. Changes imposed by aging over a lifespan of maximally 10 days will be difficult to distinguish from mere activation. Tissue-resident Mⱷ are embryonically derived (yolk sac, fetal liver), settle into tissue, turn over and are maintained with little or significant input from bone-marrow-derived monocytes. Studies in transplant recipients have provided evidence that tissue resident Mⱷ may live for up to 10 years [42]. To which degree tissue resident Mⱷ are affected by host aging remains undefined. Current concepts of Mⱷ aging propose that phagocytic function may decline with age, that they may produce more pro-inflammatory cytokines, that TLR expression may be reduced, and that autophagy may be impaired [44]. In essence, due to differences in life span, aging of lymphocytes and of myeloid cells occurs on a vastly different scale, questioning to which degree underlying mechanisms are transferable amongst the cell types of the innate and adaptive immune system.

3. Mitochondria in immune aging and autoimmune disease

Cellular survival, division and effector function impose high biosynthetic and high bioenergetic needs. As the central hub of ATP and metabolite production, mitochondria have a particularly important role in aging and accumulated data have focused attention on mitochondria as disease relevant organelles in rheumatoid arthritis [45]. Functional mitochondria ensure that T cells maintain good health and preserve self-tolerance by providing them with easy access to bioenergy. In older individuals, CD4+ T cells have a greater abundance of mitochondrial proteins involved in the assembly of the electron transport chain (ETC), yet they demonstrate decreased oxidative phosphorylation (oxphos), indicating reduced mitochondrial fitness [46]. The accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria may be attributed to defective autophagy [46], a mechanism critically important in sorting intact versus damaged mitochondria. In addition to their function in generating ATP and ensuring cellular energy supply, mitochondria also produce a wide range of metabolic intermediates that function as signaling molecules. These intermediates, including succinate, citrate, and alpha-ketoglutarate, play a direct role in communicating with other subcellular organelles [47], and serve as substrates in the posttranslational modification of nuclear and cytosolic proteins [48–50]. Mitochondrial products connect cellular metabolism to epigenetic regulation, to cell fate decisions, to cell differentiation and to stemness. Mitochondria determine the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)+/NADH, pyruvate/lactate, and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)/2- hydroxyglutarate (2-HG) ratios, controlling essentially every aspect of cellular function. As T cells age, their anaplerotic and cataplerotic capacities decline, their ability to generate bioenergy and to maintain interorganelle communication becomes increasingly diminished [51]. Ultimately, failing mitochondria undermine T cell longevity, T cell differentiation and healthy T cell effector functions. Such metabolically stressed T cells adopt a pro-inflammatory phenotype and are highly enriched in patients with autoimmune disease (Figure 1).

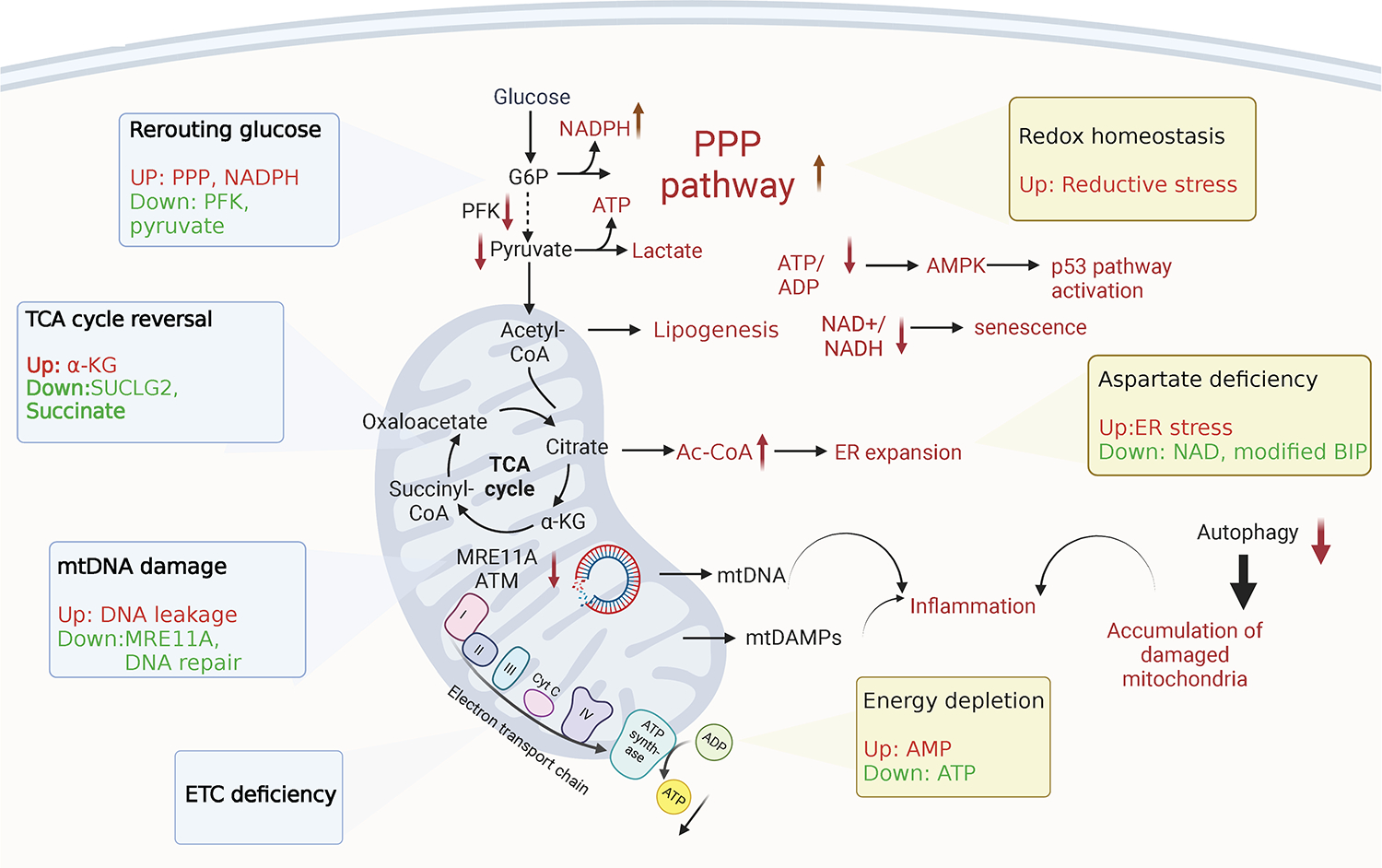

Fig. 1. Mitochondria in immune aging-related autoimmune disease.

Aging mitochondria show defects in various aspects, including glucose rerouting, tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) reversal and reduced electron transport chain (ETC) efficiency in metabolism, as well as accumulation of mitochondrial DNA damage. Aging immune effector cells suffer from ATP depletion, metabolite imbalance, loss of redox homeostasis and ER stress. Damaged mitochondria contribute to autoimmune inflammation through multiple mechanisms, specifically, in rheumatoid arthritis.

3A. Bypassing mitochondria

While mitochondrial failure has been linked to various inflammatory conditions, its role is best defined in the context of the autoimmune disease rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [4, 52]. The first observation linking mitochondrial failure to autoimmune tissue inflammation came a decade ago, when investigators found that RA T cells downregulate the glycolytic enzyme phosphofructokinase (PFK), essentially minimizing glycolytic flux and restricting delivery of pyruvate to the mitochondria [53]. Glucose metabolism involves breaking down glucose into ATP and intermediate metabolites through glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP). When compared to healthy individuals, naïve CD4+ T cells from patients with RA reroute glucose metabolism [54], suppressing glycolytic breakdown into lactate and pyruvate and instead channeling glucose into the PPP. The result is the buildup of NADPH and the consumption of cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) [55], creating a reductive environment in patient-derived T cells. At the same time, mitochondria in RA T cells receive less pyruvate and need to supply the TCA cycle by cataplerosis, such as the uptake of the amino acid glutamine to maintain ATP production. Depletion of pyruvate, dependence on cataplerosis and insufficient production of lactate are all indicators of intense mitochondrial stress, which should have ripple down effects for other subcellular organelles, such as lysosomes and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).

3B. Too much acetyl-CoA, too little aspartate

To minimize metabolic stress, RA T cells adapt to the lack of pyruvate and reprogram the TCA cycle. Specifically, downregulation of the GDP-forming β subunit of succinate-CoA ligase (SUCLG2) causes the TCA cycle to shift from oxidative to reductive direction. Immediate consequences include reduced production of the metabolite succinate, combined with accumulation of α-ketoglutarate, citrate, and acetyl-CoA (AcCoA) [56]. These changes in the mitochondrial metabolism of RA T cells have profound impact on the functional commitment of RA T cells, as confirmed in in vitro and in vivo studies [56]. In RA T cells with low succinate and high AcCoA levels, tubulin acetylation stabilizes the microtubular cytoskeleton, affecting cellular shape, motility, and placement of subcellular organelles. In particular, tubulin hyperacetylation alters the position of mitochondria, placing them close to the nuclear membrane and thereby exposing nuclear DNA to oxidative pressure. Metabolic control of the cytoskeleton affects multiple domains of T cell function: cellular polarization, uropod formation, migration, and tissue invasion [56]. One of the functionally most impactful consequences of TCA reversal in RA T cells relates to production of the amino acid aspartate [45]. In healthy mitochondria, malate is metabolized into aspartate via oxaloacetate. Aspartate is transported into the cytosol to be reverted back into malate (malate-aspartate shuttle). This shuttle allows regeneration of the cytosolic NAD pool, and signals to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that mitochondrial function is balanced. In the pre-aged RA T cell, mitochondrial aspartate declines due to insufficient production of succinate and malate [57]. This mitochondrial deficiency imposes pressure on the cytosolic NAD pool and stresses the ER, indicated by marked expansion of ER membranes. Expanded ER membranes provide anchoring sites for ribosomes, with non-randomness of membrane-bound ribosomes [57]. In RA T cells, TNF mRNA is highly enriched amongst the ER-bound transcripts, turning such T cells into TNF superproducers [57]. TNF is recognized as a key cytokine in the disease process of rheumatoid arthritis [58, 59], exemplifying how mitochondria-directed metabolic signaling pathways ultimately translate into autoimmunity [57].

3C. Fat T cells

Excess production of AcCoA has implications for another, disease-relevant function of T cells in RA patients; the invasion of these T cells into the tissue [60]. Invasive RA T cells overexpress the podosome scaffolding protein TKS5, forming membrane structures that allow rapid mobility in the tissue microenvironment. Metabolic flux data and transcriptomics studies have implicated low glycolytic activity and disrupted mitochondrial TCA cycle in the overproduction of citrate, the precursor of cytosolic AcCoA, which then serves as a building block in aggressive lipogenesis and lipid droplet deposition [60, 61].

3D. Mitochondrial garbage production

In addition to regulating the well-being of cells, tissues and the host through bioenergy and metabolic intermediates, mitochondria are a rich source of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Mitochondrial DAMPs can be released into the cytosol or the extracellular space and then elicit a strong inflammatory response [62, 63]. Due to their bacterial ancestry, mitochondria possess DAMPs (N-formyl peptides, TFAM, lipids, cardiolipin, succinate, ATP etc) and also mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) that are detected by the host’s immune and non-immune cells and relay information about the state of mitochondrial health and mitochondrial stress to the innate immune system [64–66]. By far the best understood mitochondrial DAMPs are the mitochondrial nucleic acids, specifically mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). The mitochondrial genome is a double-stranded circular DNA molecule of around 16 kilobases and encodes for 22 tRNA, 2 rRNA and 13 essential subunits of the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation system: complex I (ND1—ND6), complex III (Cyt b), complex IV (COX I—COX III), and complex V (A8 and A6). Although the cell expends a significant amount of energy to repair and maintain nuclear DNA, mitochondrial DNA is even more susceptible to damage because it lacks protective histones and is close to reactive oxygen species. The DNA repair machinery imposes high demand for energy and biosynthetic activity and rapidly declines in efficiency with aging. T cells from RA patients accumulate DNA double-strand breaks, a consequence of the transcriptional repression of the DNA repair kinase ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) [67, 68]. The repair mechanisms that are dependent on DNA-PKcs, Ku70, and Ku80 are also sensitive to aging-imposed deficiency, leaving RA T cells vulnerable to persistent cellular stress and inappropriate T cell demise [68]. Premature T cell loss due to insufficient DNA repair has been considered a critical mechanism in driving hemostatic proliferation of RA T cells, exposing them to proliferative stress and premature aging [4]. Insufficiency of DNA repair mechanism in RA T cells extends to the mitochondrial genome. Specifically, transcriptional suppression of the repair nuclease MRE11A in RA T cells imposes significant stress on mitochondria. MRE11A has been directly implicated in securing mitochondrial fitness, including efficiency of the electron transport chain [69]. MRE11Alow RA T cells leak mtDNA into the cytosol, where this mitochondrial DAMP (Danger Associated Molecular Pattern) is recognized by nucleic acid sensors to trigger inflammasome activation. Such T cells form gasdermin-dependent pores, release IL-1β and IL-18 and enter pyroptotic cell death, a strong pro-inflammatory nidus in the synovial tissue site [69]. These data have provided a mechanistic link between aging, declining DNA repair and mitochondrial stress.

In essence, maintaining intact mitochondria is crucial for preserving T cell tolerance. Youthfulness is associated with efficient DNA repair; damaged DNA is a hallmark of aging. Aging-associated DNA damage affects the mitochondrial genome and has three consequences: failing of the ETC which depletes cellular ATP stores; reprogramming of the TCA cycle which undermines mitochondrial signaling efficiency and leakage of mitochondrial molecules into the cytosol, which transforms aged T cells into mitochondrial DAMP-releasing effector cells. Outcomes range from misdifferentiation into short-lived effector T cells, enhanced propensity of tissue invasiveness and pyroptotic T cells death, identifying aged T cells as potent inducers of tissue inflammation.

4. Lysosomes and autophagosomes in immune aging and autoimmune disease

The functional loss typically associated with immune aging produces cellular garbage, which overwhelms the cell’s garbage removal system. The accumulation of damaged proteins, membranes, organelles, and nucleic acids in aging cells has prompted the term “garbaging” [70], proposing that the accrual of garbage is a hallmark of immune aging. Healthy cells have in place a sophisticated machinery that allows them to remove protein aggregates, damaged organelles, and intracellular pathogens, and use the lysosomal degradation pathway of autophagy to adapt to metabolic and genomic stress, and to renovate during periods of differentiation [71–73]. Autophagy involves the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes, followed by the degradation of the luminal cargo. Aging is now recognized as a critical factor in impairing autophagy, and it has been proposed that failing autophagy drives the aging process in T cells [74]. Along with other proteolytic systems, such as proteasomes, lysosomal autophagy is involved in the continuous turnover of intracellular components. Together with the DNA damage response, the unfolded protein response, and mitochondrial stress signaling, autophagy is considered one of the major stress response pathways that drive adaptive responses and secure host survival. In older adults, insufficient autophagy results in the loss of intracellular recycling, the breakdown of proteostasis and the accumulation of toxic garbage (Figure 2).

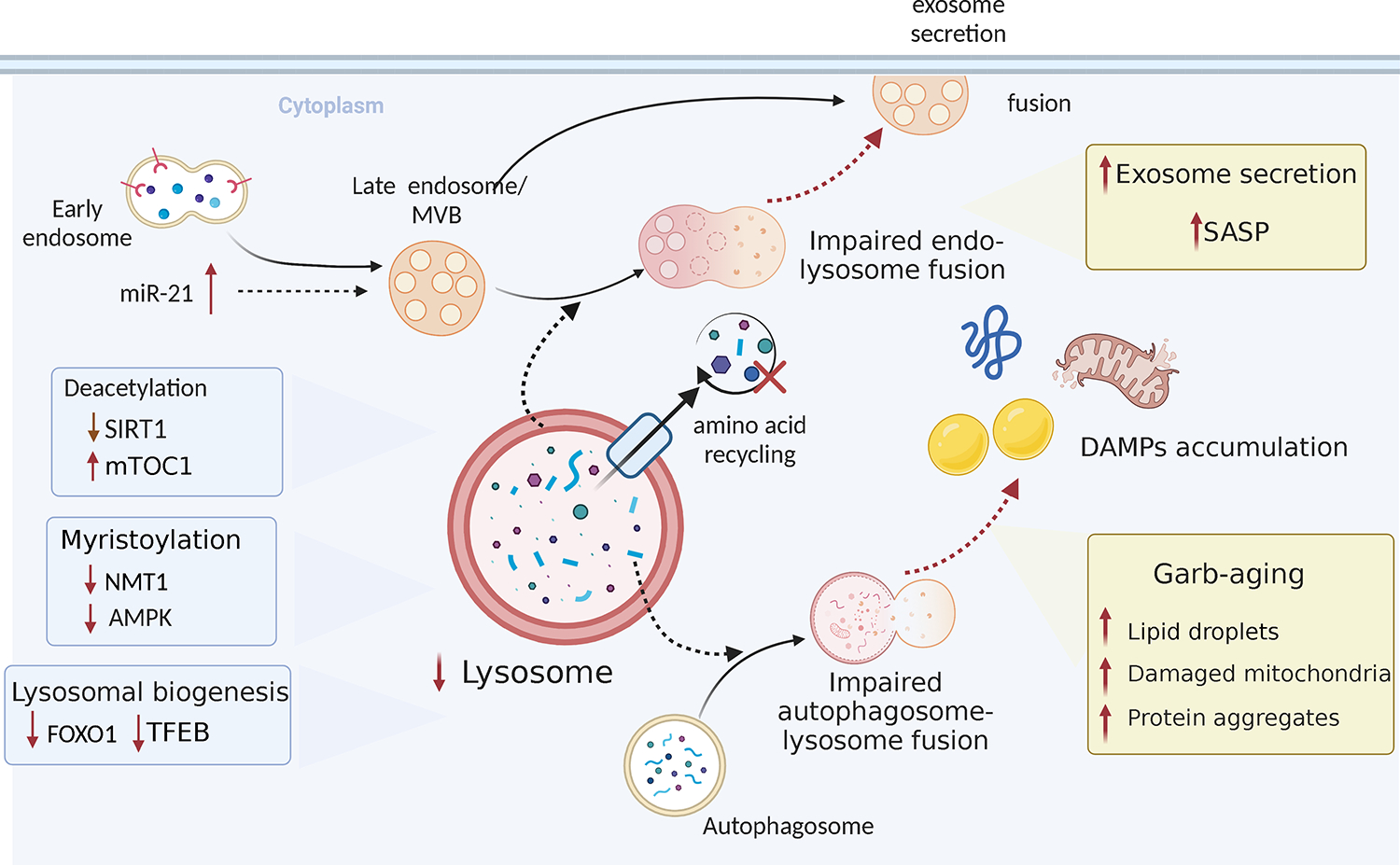

Fig. 2. Lysosomes and autophagosomes in immune aging-related autoimmune disease.

Lysosome biogenesis decreases with age. Increased mTOC1 activity inhibits autophagic processes. Impaired endosome or autophagosome-lysosome fusion results in increased exosome secretion and extracellular accumulation of damage-associated molecular patterns, which contributes to senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) and inflammation.

The main regulatory pathway for autophagy is the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) cell signaling [75–77]. mTOR is responsible for controlling cell growth and plays a critical role in highly proliferative immune cells. mTORC1 is primarily a nutrient sensor and links nutrient status to growth by integrating signals from nutrients (particularly amino acids) and the fuel gauge 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) to determine whether the cell should divide and grow or become dormant. Accordingly, excess nutrients will stimulate the mTORC1 system and turn off autophagy to put the cell into growth mode. Under nutrient deprivation, mTOR is inhibited and autophagy is activated to mobilize internal resources. mTORC1 is a potent inhibitor of autophagy [78], which mechanistically connects mTORC1 signaling to disruptions in proteostasis.

4A. Lazy lysosomes, vigorous mTORC1

Evidence has been provided that functional autophagy is required for the induction of memory CD8+ T cells [79], a prerequisite for the generation of immunological memory that protects the host against infection and malignancy. The propensity of older adults to generate short-lived effector cells at the expense of long-lived memory T cells is a core deficiency leading to immune aging [5]. The preference of aged T cells to choose short-lived effector function over long-lived memory suggests unopposed mTOR activation combined with inefficient “garbage removal.”

Molecular mechanisms underlying the sluggish memory T cell development in older adults include the upregulation of miR-21, which stabilizes the mTORC1 pathway while suppressing autophagic activity [33]. Notably, in T cells from older individuals, mTORC1 activation occurs at the late endosome, where mTORC1 is engaged in sensing cytoplasmic amino acids [80]. The transcription factor FOXO1 has been identified as a master regulator of the mTOR/autophagy disbalance in older T cells. Older CD4+ T cells that undergo activation rapidly downregulate FOXO1 and TFEB, suppressing lysosomal biogenesis. In view of weak lysosomal activity, older CD4+ T cells compensate by expanding the production of multivesicular bodies (MVB). Age-related adaptations in older T cells with impaired autophagy include the expansion of cell mass, now recognized as a feature of senescence. In parallel, the bias towards MVB formation leads to enhanced exosome release, providing older T cells with additional ways of cell-to-cell communication [81].

Numerous lines of evidence support the concept that autophagy is cytoprotective and has anti-inflammatory properties. Genetic modifications disrupting autophagy in CD4+ T cells trigger systemic inflammation [82]. In support of this concept, activation of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor stimulates the protein kinase B-mammalian target of rapamycin (AKT-mTOR) pathway, which promotes aerobic glycolysis and favors Th17 cell differentiation over that of Treg cells [83]. Uncontrolled activation of mTORC, driving the differentiation of CD4+ T cells into effector cells that produce IFNγ and IL-17, is a feature of pathogenic CD4+ T cells in the autoimmune disease giant cell arteritis (GCA). GCA is an autoimmune vasculitis that exclusively occurs in individuals during the 6th-8th decade of life. Immune ageing is now considered a major pathogenic risk factor [84]. A hallmark of GCA is the stimulation of pathogenic CD4+ T cells by endothelial cells lining the microvessels in the target tissues [85]. Tissue invasive GCA CD4+ T cells have high exosomal activity and activate tissue macrophages to form granulomatous infiltrates. GCA causes clinical manifestations by triggering intimal hyperplasia and blood vessel occlusion, compatible with immune-mediated regulation of vascular stromal cells. A prototypic abnormality in GCA CD4+ T cells is the aberrant expression of the NOTCH1 receptor [85, 86]. NOTCH1 signaling ensures T cell survival by activation of autophagy [87, 88]. In malignant T cells in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), gain-of-function mutations in the NOTCH signaling pathways have been implicated in sustaining uncontrolled growth by NOTCH-dependent glycolysis and mitochondrial activity [89]. Together, these data demonstrate the tight relationship between intracellular energy flow, autophagy, mitochondrial fitness, and pro-inflammatory properties of T cells.

In summary, aged T cells are deprived of protective stress responses. Insufficiency of lysosomal autophagy disrupts cellular recycling, results in intracellular garbage deposition, and intensifies exosome secretion. The dominance of the mTORC1 signaling pathway promotes differentiation, lineage commitment and expansion. The outcome is a short-lived effector T cell that has pro-inflammatory potential by releasing intracellular content into the extracellular space.

4B. Shortage of anti-inflammatory exosomes

Aging-related decline of lysosomal function not only affects the cell’s garbage handling, but it also deviates the flux of intracellular vesicles towards the exosomal pathway. Exosomes are now recognized as important mediators of cell-cell crosstalk, carrying cargo derived from one cell to neighboring cells. With aging-related adaptations changing the composition of exosomal cargo, it is to be expected that the communication of aging T cells with their microenvironment is fundamentally altered. An important example of ageing-imposed changes in exosomal pathways has been reported in GCA, where the failure of CD8+ T regulatory cells has been implicated in the loss of self-tolerance and chronic autoimmunity [90, 91]. Specifically, functional CD8+ Regulatory T cells (Treg) utilize the exosomal release of NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) to suppress the activation of neighboring CD4+ T cells [92]. The abundance and functional intactness of these CD8+ Treg cells declines with progressive age and fails prematurely in patients with GCA. Molecular mechanisms underlying the CD8+ Treg cell failure have been defined [90]. Patient-derived CD8+ Treg cells have poor function and fail to suppress vasculitogenic CD4+ T cells. Due to aberrant signaling in the NOTCH4 signaling pathway, non-functional CD8+ Treg cells deviate endosomal trafficking and lose production of the suppressive exosomes. In this case, the age-related deterioration of Treg cell function, caused by derailment of the endo-lysosomal system becomes a risk factor for autoimmune tissue inflammation.

4C. Lysosomes as sensing organelles

Once considered the site where endocytosed macromolecules are digested, lysosomes are now recognized as dynamic organelles, able to fuse with many targets. They have been identified as a platform for nutrient sensing and distribution of bioenergetic information to the nucleus, making them critical regulators of T cells fate decisions and survival. In addition, they are known as secretory organelles, enabling immune cells to rapidly share information, but also nutrients, with neighboring cells. Lysosomal failure appears particularly important as a facilitator of AMPK-mTORC communication. In the premature aging syndrome RA, lysosomes are critical in rerouting intracellular energy flow. Proteomic analysis of T cells from RA patients has revealed a shift in posttranslational protein modification that is highly relevant for metabolic regulation and has direct impact on disease-relevant functions [52, 93]. Specifically, impaired protein myristylation in RA T cells modifies the intracellular distribution and protein-protein interactions of the energy sensors AMPK and mTORC1 [94].Low production of N-myristoyltransferase in RA T cells prohibits lipidation of AMPK, preventing the anchoring of AMPK in the lysosomal membrane. AMPK recruitment to the lysosomal surface is a key step in AMPK-mediated suppression of mTORC1 activation [95]. Insufficiently lapidated AMPK in RA T cells disrupts this critical regulatory process, leaves mTORC1 unopposed and enables continuous activation of the mTORC1 signaling pathway [94]. This abnormality in autoimmune T cells matches with the misdifferentiation of older CD4+ T cells into terminally differentiated effector T cells instead of memory T cells due to sustained mTORC1 activation on the surface of late endosomes [80].

Persistent activation of the mTOR signaling pathway is a hallmark of T cells of patients with autoimmune disease. In the autoimmune vasculitides GCA and Takayasu arteritis, CD4+ T cells have unprovoked activation of mTORC1 [96], promoting differentiation of cytokine producing effector T cells. In parallel, T cells from GCA patients and from older healthy adults have low SIRT1 activity [97, 98], often considered a hallmark of immune aging. Sirtuins, particularly SIRT1, are believed to be strong inducers of autophagic activity [99], giving rise to the concept that the triad of failing SIRT1, failing autophagy and unopposed mTORC1 activity is a characteristic abnormality of T cell aging [100–103]. The life-prolonging effects of calorie restriction have also been attributed to the activation of SIRT, AMPK and mitochondrial repair by starvation [104, 105].

The power of lysosomes in controlling bioenergetic and biosynthetic competence is closely related to their ability to sort mitochondria and remove damaged organelles by mitophagy. Lysosomes cooperate with autophagosomes that enclose damaged mitochondria before the unfit organelles are degraded in the lysosomal lumen [106, 107]. This process prevents the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and promotes mitochondrial health, which is essential for the generation of long-lived memory T cells [108, 109]. Impaired mitophagy causes T cell dysfunction in chronic viral infection and in tumor models, and the inability to generate protective immune responses is directly related to mitochondrial dysfunction [110, 111]. Similarly, mitophagy is the process through which cells adapt to metabolic stress and metabolically stress T cells are prone to disadvantageous fate decisions and functional commitments [112]. Effective mitophagy protects cells against the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [113, 114], preventing T cell pyroptosis and pyroptosis-induced tissue inflammation.

Taken together, autophagy and lysosomal dysfunction ultimately determine mitochondrial health, the effectiveness of metabolic adaptations and the preparedness of T cells to differentiate into protective long-lived memory T cells versus misdifferentiating into short-lived pro-inflammatory effector T cells that emerge as key drivers in autoimmune disease.

5. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in immune aging and autoimmune disease

Loss of protein homeostasis is considered a hallmark of cellular aging [115]. One mechanism critically involved in maintaining protein homeostasis is the unfolded protein response of the endoplasmic reticulum (UPR(ER)). The UPR(ER) and other stress responses that help mitigate proteostasis disruptions are known to become less effective with age, linking declining ER functionality to age-related morbidities [116, 117].

5A. ER stress nurturing inflammation

In mammalian cells, three main signaling cascades, activated by the ER transmembrane protein sensors PERK, IRE1α and ATF6α, make up the basic unfolded protein response (UPR) [118, 119]. (1) Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit-α (eIF2α) is phosphorylated by PERK, inhibiting mRNA translation initiation. Despite this general reduction, specific mRNAs, such as ATF4 mRNA, are translated preferentially in the presence of phosphorylated eIF2α. Once translated, ATF4 activates the transcription of UPR target genes. These genes encode molecules involved in a multitude of processes, including amino acid biosynthesis, antioxidative responses, autophagy, and apoptosis [120, 121]. (2) IRE1α RNase performs splicing on XBP1 mRNA, which encodes a powerful transcription factor that triggers the expression of UPR target genes [122, 123]. Also, IRE1α RNase cleaves ER-associated mRNAs or non-coding functional RNAs, leading to their degradation through regulated IRE1-dependent decay (RIDD) and regulating protein folding load, cell metabolism, inflammation, and inflammasome signaling pathways [124]. In addition, the cytosolic domain of IRE1α acts as a scaffold for adaptor proteins, e.g., members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) family. This recruitment activates inflammatory responses in non-canonical ER stress conditions [125, 126]. (3) ATF6 moves from the ER to the Golgi apparatus to undergo cleavage by site-1 protease (S1P) and site-2 protease (S2P), generating an active cytosolic ATF6p50 fragment. The fragment travels to the nucleus and activates the transcription of UPR target genes, optimizing ER protein folding processes [127]. In addition, the proteasome-based ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) machinery breaks down unfolded or misfolded proteins present in the ER lumen. This process is regulated by the UPR branches mediated by ATF6 and/or IRE1α-X-box-binding protein 1 (XBP1) [128].

The UPR plays a significant role in the signal transduction of inflammatory responses and is of critical importance in pro-inflammatory T cells and Mⱷ. When eIF2α is phosphorylated by PERK, overall protein synthesis is reduced, and nuclear factor-κB (NF- κB) activation is favored [129]. This process induces proinflammatory genes. IRE1α and PERK signaling, on the other hand, promote the production of proinflammatory cytokines by directly binding to Tnfα, Il6, and Il8 gene promoters in various cells, including macrophages, fibroblasts, astrocytes, and epithelial cells [130–132]. The IRE1α-mediated UPR serves as a crucial regulatory node that governs macrophage-mediated inflammation in metabolic and autoimmune diseases. In adipose tissues, IRE1α senses metabolic and immunological states, and guides adipose tissue macrophage polarization [133]. Furthermore, hyperactivation of the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway by TRAF6 mediated IRE1α ubiquitination in Mⱷ can lead to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, a significant driving force behind inflammatory arthritis [134]. The involvement of ER stress in regulating self-tolerance and autoimmune disease extends to Treg cells. The ERAD-associated E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Hrd1 is critically involved in maintaining Treg stability and functions through suppressing the IRE1α-mediated ER stress response. Treg-specific ablation of Hrd1 causes massive multiorgan lymphocyte infiltration, body weight loss, and severe small intestine inflammation with aging, exemplifying the role of ER stress in immune aging and in tissue inflammation [135].

5B. Retention of inhibitory ligands on the stressed ER

The ER is the major site for protein folding and maturation in the endomembrane system of the eukaryotic cell. Proteins that have attained their native conformation are sorted into ER-to-Golgi transport carriers. Proteins that fail to fold properly become subject to ERAD, which removes misfolded, unassembled and mistargeted proteins from the ER into the cytosol where they are degraded by the proteasome. ER stress and the UPR are considered adaptive responses, supposed to increase ER protein folding capacity, which should resolve ER stress and close a homeostatic feedback loop. Antigen-presenting cells (APC) are metabolically highly active, dependent on intracellular vesicular trafficking for antigen processing and presentation and express numerous cell surface ligand that are critical regulators of T cell activation [136–138]. Recent data indicate that ER stress in APC is a risk factor for age-related autoimmunity. Specifically, ER stress has been directly implicated in regulating the expression of co-inhibitory ligands on monocytes and macrophages in patients with the autoimmune disease GCA. In 2017, dendritic cells and macrophages from GCA patients were found to have low expression of PD-L1, thus failing to transmit negative signals to differentiating T cells [139]. Blocking the PD-L1/PD-1 axis broke tissue tolerance in the vascular wall, implicating PD-L1 expression in suppressing autoreactivity. The PD-L1low phenotype is a biomarker in GCA patients and separates them from patients with atherosclerotic disease [140]. PD-L1 expression is under metabolic control, with glucose and pyruvate serving as a strong inducer [140, 141].

Recent studies have identified a second inhibitory ligand that is poorly expressed on GCA APC, the CD155 ligand [142]. CD155 binds CD96 and TIGIT to inhibit T cell proliferation and function [143]. Subcellular mapping studies in patient derived Mⱷ have placed the CD155 protein on the ER, with some of the protein co-localizing with the ERGIC. Tunicamycin-induced ER stress was sufficient to retain CD155 protein on the ER. In the patients, essentially all monocytes, Mⱷ and DC were low expressers for CD155. It is currently unknown whether the ER retention of CD155 and PD-L1 results from shared mechanisms or is caused by ligand specific abnormalities.

Retention of CD155 on the stressed ER has major implications for the induction of immune responses and autoimmunity. GCA patients expand CD96+ CD4+ T cells and recruit such T cells to the inflamed vessel wall. Unopposed CD96+ CD4+ T cells produce the cytokine IL-9, which mediates aggressive vasculitis [142] (Figure 3).

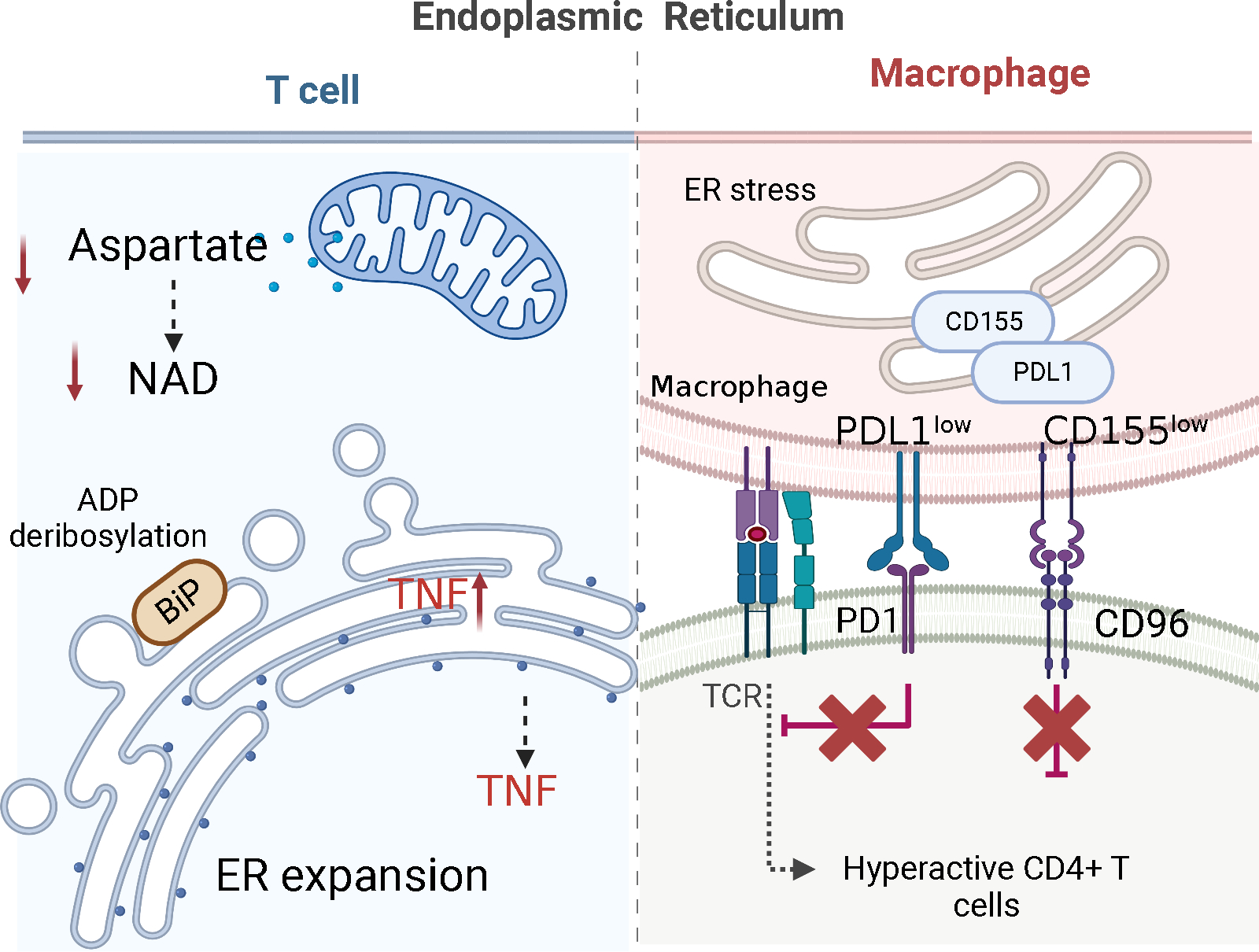

Fig.3. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in immune aging-related autoimmune disease.

(1) The size of the ER and the maturation of proteins are controlled by mitochondria-derived aspartate, which regenerates cytoplasmic NAD+ to ADP-ribosylate the ER stress sensor BiP. In the pre-aged T cells of rheumatoid arthritis patients, shortage of mitochondrial aspartate leads to an increase in ER size, accumulation of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) mRNA on ER membranes and excessive production of TNF. (2) Macrophages from patients with giant cell arteritis retain the checkpoint ligand CD155 in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and fail to bring it to the cell surface. CD155low antigen-presenting cells induce expansion of CD4+CD96+ T cells, which become hyperactive and tissue invasive.

5B. ER-Mitochondria contact sites in immune aging and autoimmune disease

As an endomembrane system, the ER populates even the most distal cytoplasmic compartments and achieves its function by directly communicating with other organelles. The ER is also the birthplace of other subcellular organelles, e.g., lipid droplets. Inter-organelle contact sites, areas of close vicinity between the membranes of two organelles that are maintained by protein tethers, are emerging as hot spots of cellular regulation and participate in organelle biogenesis, division, apoptosis, and autophagy. They are considered instrumental in ion and phospholipid homeostasis, in the transport of lipids and serve as hubs for nutrient and stress signaling [144] (Figure 4). As the most broadly distributed organelle, the ER is a partner in many of these contact sites and forms functional communication platforms with mitochondria, peroxisomes, endosomes, the Golgi apparatus, the plasma membrane, lipid droplets, lysosomes and autophagosomes [145, 146]. One of the most extensively studied examples of such sites is the interaction between the outer membrane of mitochondria (OMM) and that of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [147, 148]. Mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAM) are distinct subcellular compartments formed by adjacent ER subdomains that are tethered to the outer membrane of mitochondria [149]. Paired complexes of MAM tethering proteins have been identified, including Mitofusin-2 (Mfn2)-Mitofusin-1/2 (Mfn1/2), inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R3)-glucose-regulated protein-75 (Grp75)-voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1), vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein B (VAPB)-protein tyrosine phosphatase-interacting protein-51 (PTPIP51), and Fission 1 (Fis1)-B cell-associated protein 31 (Bap31) [150]. MAMs serve numerous functions, such as regulating lipid synthesis and transport [151], initiating cellular apoptosis [152], facilitating autophagy [153], transporting Ca2+ and signaling [154], and influencing mitochondrial dynamics [155]. Most importantly, they serve as platforms for NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and activation, triggering inflammatory responses [156]. Multiple studies suggest that MAMs have a role in cellular aging. Recent evidence implicates MAMs in the induction of cellular senescence, a condition of permanent cessation of proliferation that involves a pro-inflammatory secretome [157]. Disruptions to the integrity of the MAM have been identified as a significant factor in the pathogenesis of various inflammatory metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/frontotemporal dementia (ALS/FTD), as well as cardiovascular disease and cancer [158, 159].

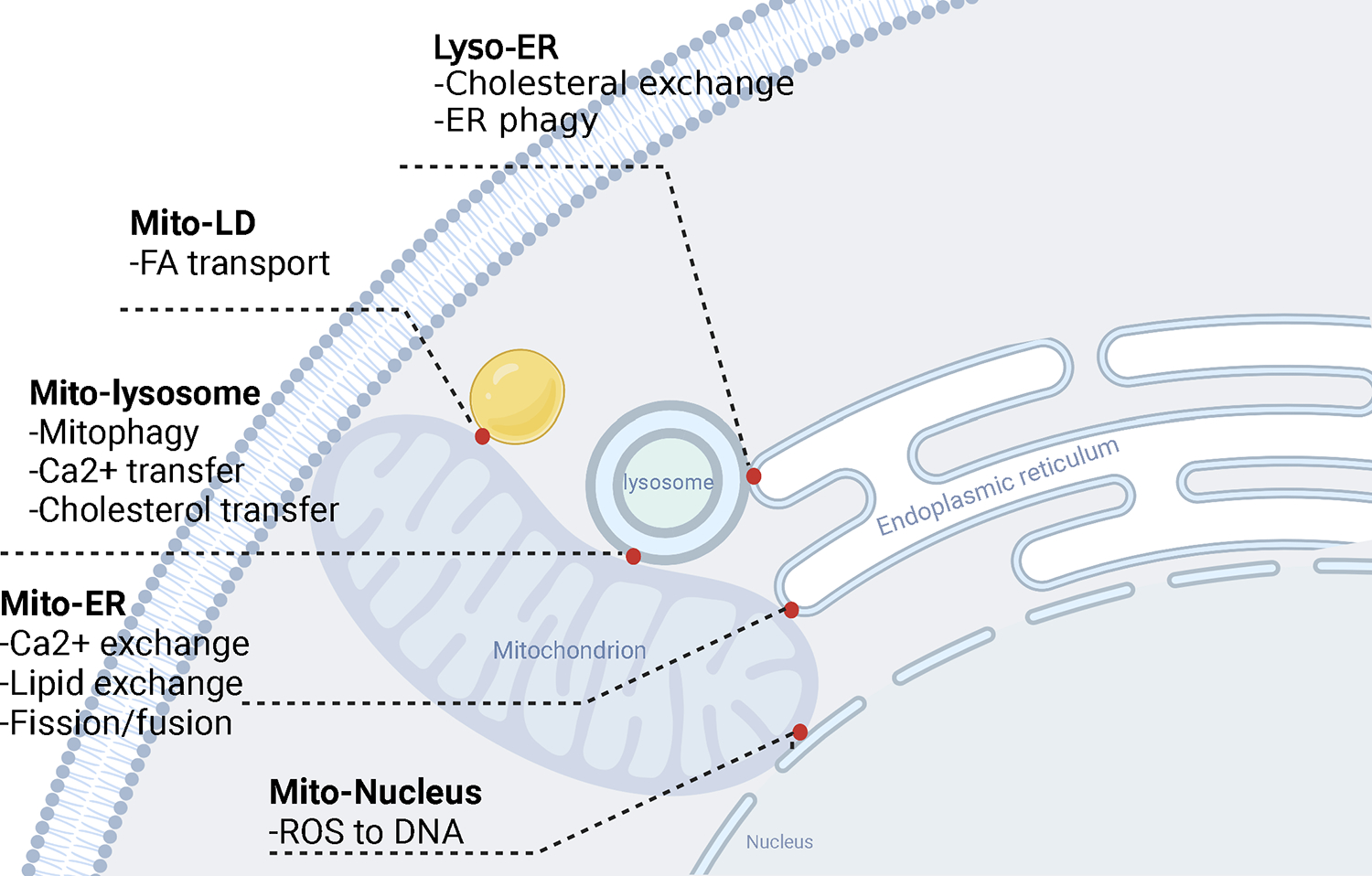

Fig.4. Inter-organelle contact sites.

Inter-organelle contact sites, areas of close vicinity between the membranes of two organelles, function in calcium and lipid transfer etc. and are emerging as hot spots of cellular regulation. These inter-organelle sites participate in organelle biogenesis, division, apoptosis, and autophagy and are emerging as critical regulators of immune cells function in health and disease.

Aging-associated changes in MAMs have also been shown to lead to alterations in the lipid membranes’ composition in the ER and mitochondria. Specifically, there is a decrease in the levels of phosphatidylserine (PS), a lipid that is important for mitochondrial membrane integrity and function, and an increase in the levels of ceramides and other lipids that are linked to inflammation and cell death [160]. PS is primarily localized at the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane but is also part of the ER and mitochondrial membranes. At the MAM, PS originates from the ER and is being transferred to the mitochondria [161], where it is guided towards the outer surface of the mitochondrial inner membrane and converted into phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) by phosphatidylserine decarboxylase. Subsequently, PE returns to the ER, where PEMT2 completes the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine (PC) [162].

MAMs function as a superb conduit for calcium, preserving calcium storages within the mitochondrial and the ER. Calcium flux is a sensitive element in cellular stress responses and participates in most inflammatory signaling pathways. Shifts in mitochondrial and ER pools can disrupt the MAM, rapidly communicate organelle stress, and derail mitochondrial function and redox homeostasis [163–165].

Disruption of MAMs affects both partners, the mitochondria and the ER. Just as mitochondria depend on intact MAMs, the ER responds to MAM destruction with a swift ER stress response, enforcing cellular adaptations, replenishment of ATP and restoration of biosynthetic activity [166, 167]. The transmission of information from the ER to the mitochondria is largely dependent on the transfer of calcium from the ER stores to the mitochondrial matrix. The reciprocal flow of information where mitochondria influence ER homeostasis is less well understood. In healthy T cells, mitochondria play a role in controlling the size of the ER and the maturation of proteins. They achieve this by releasing aspartate, which regenerates cytoplasmic NAD+ and ADP-ribosylates the ER stress sensor BiP [57]. In the pre-aged T cells of RA patients, shortage of mitochondrial aspartate leads to an increase in ER size, accumulation of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) mRNA on ER membranes and excessive production of TNF [57] (Figure 3).

6. Conclusions

Lifelong restructuring of the immune system and adaptation to an expanding exposome result in loss-of-function and gain-of-function. Older adults lose the ability to generate lasting, highly specific adaptive immune responses and gain a state of low-grade smoldering inflammatory activity, reflective of dwindling adaptive immunity and poorly controlled innate immunity. In predisposed individuals, immune aging gives rise to frank autoimmune disease (Table 1). Cellular and molecular mechanisms through which the immune aging process shapes immune effector cells and transforms them into auto-aggressive facilitators include:

Table 1.

Shared Features in autoimmune disease and in immune aging

| Autoimmune disease | Immune Aging | |

|---|---|---|

| Autoantibody production | +++ | ++ |

| Accumulation of Age-associated B cells (ABC) | +++ | +++ |

| Accumulation of end-differentiated T cells (TEMRAs) | ++ | +++ |

| SASP of immune and non-immune cells | +++ | +++ |

| Clonal hematopoiesis | ++ | +++ |

Mitochondrial failure. T cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis have insufficient mitochondrial DNA repair, which disrupts multiple domains of mitochondrial function. Leakage of mtDNA induces inflammasome assembly and pyroptotic death. Low efficiency of the complex V of the ETC deprives T cells of ATP. Downregulation of succinyl-CoA ligase leads to TCA cycle reversal, promoting overproduction of citrate. Excessive lipogenesis fuels lipid droplet deposition and stimulates formation of invasive membrane structures. The inability to metabolize acetyl-CoA fosters cytoskeletal acetylation, cellular polarization, and motility.

Lysosomal failure. In T cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the lysosomal surface is occupied by mTORC1, but lacks its physiologic inhibitor AMPK, leading to unopposed and sustained mTORC1 activation and differentiation of such T cells into short-lived effector T cells. Also, lysosomal insufficiency fosters the accumulation of damaged mitochondria by impairing autophagy/mitophagy.

Chronic ER expansion in T cells. T cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis expand the rough ER membranes and accumulate mRNAs encoding for membrane-integrated molecules, including the cytokine TNF. The underlying defect stems from insufficient mitochondrial release of the amino acid aspartate, which disrupts the cytosolic pool of NAD and signals chronic ER stress. The result is a TNF super-producing T cell.

Chronic ER stress in antigen-presenting cells. Monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells from patients with giant cell arteritis retain PD-L1 and CD155 in the chronically stressed ER. These APC have low surface expression of PD-L1 and CD155, disrupting negative signaling of PD-1 (Programmed Death 1)+ and CD96+ T cells. Such T cells are unopposed and promote autoimmune vasculitis by releasing the effector cytokine IL-9 (“lost inhibition”).

Rejuvenation of the immune system and prevention of aging-related autoimmune disease need to focus on repairing fundamental properties of innate and adaptive immune cells: restoring DNA repair to maintain the mitochondrial genome; refurbish the lysosomal system to strengthen amino acid recycling, autophagy, and regulation of the mTOR pathway; alleviating chronic ER stress to prevent biased production of cytokines.

The risk of older individuals to develop cancer and autoimmune disease appears to be related to the critical role of inhibitory signals in controlling T cell immunity: overexpression of inhibitory ligands confers immune evasion of tumors, underexpression of inhibitory ligands enables inappropriate and tissue-destructive T cell immunity and autoimmune tissue inflammation. Fine-tuning of inhibitory signaling may facilitate impactful readjustments in the aging immune system and provide novel therapeutic options in autoimmune diseases with abnormalities in negative signaling.

Highlights:

The aging immune system loses the ability to generate lasting and highly specific immune responses and gains a state of low-grade, sterile inflammation.

Immune ageing is a risk factor for autoimmune disease.

Aging-related mitochondrial failure renders T cells tissue-invasive and prone to pyroptosis.

Aging-related lysosomal malfunction induces exosome-releasing T cells, spreading pro-inflammatory signals to the tissue environment.

Aging-related endoplasmic reticulum (ER) expansion, caused by lack of mitochondrial aspartate, turns T cells into TNF superproducers.

Aging-related endoplasmic reticulum stress creates non-inhibitory antigen-presenting cells and unleashes T cell immunity by retaining PD-L1 (programmed death ligand 1) and CD155 in an intracellular compartment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01AR042527, R01AI108906, R01HL142068, and R01HL117913 to CMW and R01AI108891, R01AG045779, U19AI057266, R01AI129191 to JJG).

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References:

- [1].Berner F, Bomze D, Diem S, Ali OH, Fassler M, Ring S et al. Association of Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Toxic Effects With Shared Cancer and Tissue Antigens in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Oncol, 2019;5:1043–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Berner F, Bomze D, Lichtensteiger C, Walter V, Niederer R, Hasan Ali O et al. Autoreactive napsin A-specific T cells are enriched in lung tumors and inflammatory lung lesions during immune checkpoint blockade. Sci Immunol, 2022;7:eabn9644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cancro MP. Age-Associated B Cells. Annu Rev Immunol, 2020;38:315–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zhao TV, Sato Y, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. T-Cell Aging-Associated Phenotypes in Autoimmune Disease. Front Aging, 2022;3:867950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Mechanisms underlying T cell ageing. Nat Rev Immunol, 2019;19:573–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zhang H, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Hallmarks of the aging T-cell system. Febs J, 2021;288:7123–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Yanes RE, Gustafson CE, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Lymphocyte generation and population homeostasis throughout life. Semin Hematol, 2017;54:33–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Johnson JL, Scholz JL, Marshak-Rothstein A, Cancro MP. Molecular pattern recognition in peripheral B cell tolerance: lessons from age-associated B cells. Curr Opin Immunol, 2019;61:33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Phalke S, Rivera-Correa J, Jenkins D, Flores Castro D, Giannopoulou E, Pernis AB. Molecular mechanisms controlling age-associated B cells in autoimmunity. Immunol Rev, 2022;307:79–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Miller JFAP. The function of the thymus and its impact on modern medicine. Science, 2020;369:522–+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Palmer DB. The effect of age on thymic function. Front Immunol, 2013;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Surh CD, Sprent J. Homeostasis of Naive and Memory T Cells. Immunity, 2008;29:848–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Westera L, van Hoeven V, Drylewicz J, Spierenburg G, van Velzen JF, de Boer RJ et al. Lymphocyte maintenance during healthy aging requires no substantial alterations in cellular turnover. Aging Cell, 2015;14:219–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sauce D, Larsen M, Fastenackels S, Roux A, Gorochov G, Katlama C et al. Lymphopenia-Driven Homeostatic Regulation of Naive T Cells in Elderly and Thymectomized Young Adults. J Immunol, 2012;189:5541–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Czesnikiewicz-Guzik M, Lee WW, Cui D, Hiruma Y, Lamar DL, Yang ZZ et al. T cell subset-specific susceptibility to aging. Clin Immunol, 2008;127:107–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Schmidt D, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. CD4+ CD7- CD28- T cells are expanded in rheumatoid arthritis and are characterized by autoreactivity. J Clin Invest, 1996;97:2027–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Liuzzo G, Kopecky SL, Frye RL, O’Fallon WM, Maseri A, Goronzy JJ et al. Perturbation of the T-cell repertoire in patients with unstable angina. Circulation, 1999;100:2135–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Liuzzo G, Goronzy JJ, Yang H, Kopecky SL, Holmes DR, Frye RL et al. Monoclonal T-cell proliferation and plaque instability in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation, 2000;101:2883–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Semmes EC, Hurst JH, Walsh KM, Permar SR. Cytomegalovirus as an immunomodulator across the lifespan. Curr Opin Virol, 2020;44:112–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Cambier J. Immunosenescence: a problem of lymphopoiesis, homeostasis, microenvironment, and signaling. Immunol Rev, 2005;205:5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kogut I, Scholz JL, Cancro MP, Cambier JC. B cell maintenance and function in aging. Semin Immunol, 2012;24:342–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hao Y, O’Neill P, Naradikian MS, Scholz JL, Cancro MP. A B-cell subset uniquely responsive to innate stimuli accumulates in aged mice. Blood, 2011;118:1294–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Andersen-Ranberg K, Hoier-Madsen M, Wiik A, Jeune B, Hegedus L. High prevalence of autoantibodies among Danish centenarians. Clin Exp Immunol, 2004;138:158–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Manoussakis MN, Tzioufas AG, Silis MP, Pange PJ, Goudevenos J, Moutsopoulos HM. High prevalence of anti-cardiolipin and other autoantibodies in a healthy elderly population. Clin Exp Immunol, 1987;69:557–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Li GJ, Yu MC, Lee WW, Tsang M, Krishnan E, Weyand CM et al. Decline in miR-181a expression with age impairs T cell receptor sensitivity by increasing DUSP6 activity. Nat Med, 2012;18:1518–U113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kuilman T, Peeper DS. Senescence-messaging secretome: SMS-ing cellular stress. Nat Rev Cancer, 2009;9:81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Rodier F, Coppe JP, Patil CK, Hoeijmakers WAM, Munoz DP, Raza SR et al. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat Cell Biol, 2009;11:973–U142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ferrucci L, Fabbri E. Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2018;15:505–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Carrasco E, de las Heras MMG, Gabande-Rodriguez E, Desdin-Mico G, Aranda JF, Mittelbrunn M. The role of T cells in age-related diseases. Nat Rev Immunol, 2022;22:97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mogilenko DA, Shpynov O, Andhey PS, Arthur L, Swain A, Esaulova E et al. Comprehensive Profiling of an Aging Immune System Reveals Clonal GZMK(+) CD8(+) T Cells as Conserved Hallmark of Inflammaging. Immunity, 2021;54:99–+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Desdin-Mico G, Soto-Heredero G, Aranda JF, Oller J, Carrasco E, Gabande-Rodriguez E et al. T cells with dysfunctional mitochondria induce multimorbidity and premature senescence. Science, 2020;368:1371–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Baixauli F, Acin-Perez R, Villarroya-Beltri C, Mazzeo C, Nunez-Andrade N, Gabande-Rodriguez E et al. Mitochondrial Respiration Controls Lysosomal Function during Inflammatory T Cell Responses. Cell Metab, 2015;22:485–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kim C, Hu B, Jadhav RR, Jin J, Zhang HM, Cavanagh MM et al. Activation of miR-21-Regulated Pathways in Immune Aging Selects against Signatures Characteristic of Memory T Cells. Cell Rep, 2018;25:2148–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zhang H, Jadhav RR, Cao W, Goronzy IN, Zhao TV, Jin J et al. Aging-associated HELIOS deficiency in naive CD4(+) T cells alters chromatin remodeling and promotes effector cell responses. Nat Immunol, 2023;24:96–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Muroyama Y, Wherry EJ. Memory T-Cell Heterogeneity and Terminology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2021;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].ElTanbouly MA, Noelle RJ. Rethinking peripheral T cell tolerance: checkpoints across a T cell’s journey. Nat Rev Immunol, 2021;21:257–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Blank CU, Haining WN, Held W, Hogan PG, Kallies A, Lugli E et al. Defining ‘T cell exhaustion’. Nat Rev Immunol, 2019;19:665–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zander R, Cui W. Exhausted CD8(+) T cells face a developmental fork in the road. Trends Immunol, 2023;44:276–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Soerens AG, Kunzli M, Quarnstrom CF, Scott MC, Swanson L, Locquiao JJ et al. Functional T cells are capable of supernumerary cell division and longevity. Nature, 2023;614:762–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Frasca D, Van der Put E, Riley RL, Blomberg BB. Reduced Ig class switch in aged mice correlates with decreased E47 and activation-induced cytidine deaminase. J Immunol, 2004;172:2155–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Blomberg BB. The generation of memory B cells is maintained, but the antibody response is not, in the elderly after repeated influenza immunizations. Vaccine, 2016;34:2834–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Patel AA, Ginhoux F, Yona S. Monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells and neutrophils: an update on lifespan kinetics in health and disease. Immunology, 2021;163:250–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Patel AA, Zhang Y, Fullerton JN, Boelen L, Rongvaux A, Maini AA et al. The fate and lifespan of human monocyte subsets in steady state and systemic inflammation. J Exp Med, 2017;214:1913–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].De Maeyer RPH, Chambers ES. The impact of ageing on monocytes and macrophages. Immunol Lett, 2021;230:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Weyand CM, Wu B, Huang T, Hu Z, Goronzy JJ. Mitochondria as disease-relevant organelles in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol, 2023;211:208–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Bektas A, Schurman SH, Gonzalez-Freire M, Dunn CA, Singh AK, Macian F et al. Age-associated changes in human CD4(+) T cells point to mitochondrial dysfunction consequent to impaired autophagy. Aging-Us, 2019;11:9234–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Nunnari J, Suomalainen A. Mitochondria: In Sickness and in Health. Cell, 2012;148:1145–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Naeini SH, Mavaddatiyan L, Kalkhoran ZR, Taherkhani S, Talkhabi M. Alpha-ketoglutarate as a potent regulator for lifespan and healthspan: Evidences and perspectives. Exp Gerontol, 2023;175:112154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Santos JH. Mitochondria signaling to the epigenome: A novel role for an old organelle. Free Radic Biol Med, 2021;170:59–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Boon R, Silveira GG, Mostoslavsky R. Nuclear metabolism and the regulation of the epigenome. Nat Metab, 2020;2:1190–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Quinn KM, Palchaudhuri R, Palmer CS, La Gruta NL. The clock is ticking: the impact of ageing on T cell metabolism. Clin Transl Immunol, 2019;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Qiu J, Wu B, Goodman SB, Berry GJ, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Metabolic Control of Autoimmunity and Tissue Inflammation in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front Immunol, 2021;12:652771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. The immunology of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Immunol, 2021;22:10–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Yang Z, Fujii H, Mohan SV, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Phosphofructokinase deficiency impairs ATP generation, autophagy, and redox balance in rheumatoid arthritis T cells. J Exp Med, 2013;210:2119–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Yang Z, Shen Y, Oishi H, Matteson EL, Tian L, Goronzy JJ et al. Restoring oxidant signaling suppresses proarthritogenic T cell effector functions in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Transl Med, 2016;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Wu BW, Qiu JT, Zhao TTV, Wang YN, Maeda T, Goronzy IN et al. Succinyl-CoA Ligase Deficiency in Pro-inflammatory and Tissue-Invasive T Cells. Cell Metab, 2020;32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Wu BW, Zhao TV, Jin K, Hu ZL, Abdel MP, Warrington KJ et al. Mitochondrial aspartate regulates TNF biogenesis and autoimmune tissue inflammation. Nat Immunol, 2021;22:1551–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Beutler BA. The role of tumor necrosis factor in health and disease. J Rheumatol Suppl, 1999;57:16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Monaco C, Nanchahal J, Taylor P, Feldmann M. Anti-TNF therapy: past, present and future. Int Immunol, 2015;27:55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Shen Y, Wen Z, Li Y, Matteson EL, Hong J, Goronzy JJ et al. Metabolic control of the scaffold protein TKS5 in tissue-invasive, proinflammatory T cells. Nat Immunol, 2017;18:1025–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Weyand CM, Shen Y, Goronzy JJ. Redox-sensitive signaling in inflammatory T cells and in autoimmune disease. Free Radic Biol Med, 2018;125:36–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Marchi S, Guilbaud E, Tait SWG, Yamazaki T, Galluzzi L. Mitochondrial control of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol, 2023;23:159–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Chowdhury A, Witte S, Aich A. Role of Mitochondrial Nucleic Acid Sensing Pathways in Health and Patho-Physiology. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2022;10:796066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Marchi S, Guilbaud E, Tait SWG, Yamazaki T, Galluzzi L. Mitochondrial control of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol, 2022:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y, Sumi Y, Sursal T, Junger W et al. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature, 2010;464:104–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Leslie DS, Dascher CC, Cembrola K, Townes MA, Hava DL, Hugendubler LC et al. Serum lipids regulate dendritic cell CD1 expression and function. Immunology, 2008;125:289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Shao L, Fujii H, Colmegna I, Oishi H, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Deficiency of the DNA repair enzyme ATM in rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Med, 2009;206:1435–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Shao L, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit mediates T-cell loss in rheumatoid arthritis. Embo Mol Med, 2010;2:415–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Li YY, Shen Y, Jin K, Wen ZK, Cao WQ, Wu BW et al. The DNA Repair Nuclease MRE11A Functions as a Mitochondrial Protector and Prevents T Cell Pyroptosis and Tissue Inflammation. Cell Metab, 2019;30:477–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Vitale G, Capri M, Salvioli S. Inflammaging and ‘Garb-aging’. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2017;28:199–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Aman Y, Schmauck-Medina T, Hansen M, Morimoto RI, Simon AK, Bjedov I et al. Autophagy in healthy aging and disease. Nat Aging, 2021;1:634–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Klionsky DJ, Petroni G, Amaravadi RK, Baehrecke EH, Ballabio A, Boya P et al. Autophagy in major human diseases. Embo J, 2021;40:e108863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Levine B, Kroemer G. Biological Functions of Autophagy Genes: A Disease Perspective. Cell, 2019;176:11–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Macian F. Autophagy in T Cell Function and Aging. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2019;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Morel E, Mehrpour M, Botti J, Dupont N, Hamai A, Nascimbeni AC et al. Autophagy: A Druggable Process. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 2017;57:375–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Zhao YG, Codogno P, Zhang H. Machinery, regulation and pathophysiological implications of autophagosome maturation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2021;22:733–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Meijer AJ, Lorin S, Blommaart EF, Codogno P. Regulation of autophagy by amino acids and MTOR-dependent signal transduction. Amino Acids, 2015;47:2037–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Korolchuk VI, Saiki S, Lichtenberg M, Siddiqi FH, Roberts EA, Imarisio S et al. Lysosomal positioning coordinates cellular nutrient responses. Nat Cell Biol, 2011;13:453–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Xu XJ, Araki K, Li SZ, Han JH, Ye LL, Tan WG et al. Autophagy is essential for effector CD8(+) T cell survival and memory formation. Nat Immunol, 2014;15:1152–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Jin J, Kim C, Xia Q, Gould TM, Cao WQ, Zhang HM et al. Activation of mTORC1 at late endosomes misdirects T cell fate decision in older individuals. Sci Immunol, 2021;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Jin J, Li XY, Hu B, Kim C, Cao WQ, Zhang HM et al. FOXO1 deficiency impairs proteostasis in aged T cells. Sci Adv, 2020;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Kabat AM, Harrison OJ, Riffelmacher T, Moghaddam AE, Pearson CF, Laing A et al. The autophagy gene Atg16I1 differentially regulates T-reg and T(H)2 cells to control intestinal inflammation. Elife, 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].DiToro D, Harbour SN, Bando JK, Benavides G, Witte S, Laufer VA et al. Insulin-Like Growth Factors Are Key Regulators of T Helper 17 Regulatory T Cell Balance in Autoimmunity. Immunity, 2020;52:650–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Gloor AD, Berry GJ, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Age as a risk factor in vasculitis. Semin Immunopathol, 2022;44:281–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Wen Z, Shen Y, Berry G, Shahram F, Li Y, Watanabe R et al. The microvascular niche instructs T cells in large vessel vasculitis via the VEGF-Jagged1-Notch pathway. Sci Transl Med, 2017;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Piggott K, Deng J, Warrington K, Younge B, Kubo JT, Desai M et al. Blocking the NOTCH pathway inhibits vascular inflammation in large-vessel vasculitis. Circulation, 2011;123:309–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Marcel N, Sarin A. Notch1 regulated autophagy controls survival and suppressor activity of activated murine T-regulatory cells. Elife, 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Sarin A, Marcel N. The NOTCH1-autophagy interaction: Regulating self-eating for survival. Autophagy, 2017;13:446–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Kishton RJ, Barnes CE, Nichols AG, Cohen S, Gerriets VA, Siska PJ et al. AMPK Is Essential to Balance Glycolysis and Mitochondrial Metabolism to Control T-ALL Cell Stress and Survival. Cell Metab, 2016;23:649–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Jin K, Wen ZK, Wu BW, Zhang H, Qiu JT, Wang YA et al. NOTCH-induced rerouting of endosomal trafficking disables regulatory T cells in vasculitis. J Clin Invest, 2021;131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Jin K, Parreau S, Warrington KJ, Koster MJ, Berry GJ, Goronzy JJ et al. Regulatory T Cells in Autoimmune Vasculitis. Front Immunol, 2022;13:844300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Wen Z, Shimojima Y, Shirai T, Li Y, Ju J, Yang Z et al. NADPH oxidase deficiency underlies dysfunction of aged CD8+ Tregs. J Clin Invest, 2016;126:1953–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Liu Q, Zheng Y, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. T cell aging as a risk factor for autoimmunity. J Autoimmun, 2022:102947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Wen ZK, Jin K, Shen Y, Yang Z, Li YY, Wu BW et al. N-myristoyltransferase deficiency impairs activation of kinase AMPK and promotes synovial tissue inflammation. Nat Immunol, 2019;20:313–+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Lahiri V, Hawkins WD, Klionsky DJ. Watch What You (Self-) Eat: Autophagic Mechanisms that Modulate Metabolism. Cell Metab, 2019;29:803–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Maciejewski-Duval A, Comarmond C, Leroyer A, Zaidan M, Le Joncour A, Desbois AC et al. mTOR pathway activation in large vessel vasculitis. J Autoimmun, 2018;94:99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Ianni A, Kumari P, Tarighi S, Argento FR, Fini E, Emmi G et al. An Insight into Giant Cell Arteritis Pathogenesis: Evidence for Oxidative Stress and SIRT1 Downregulation. Antioxidants-Basel, 2021;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Kim C, Jin J, Ye ZD, Jadhav RR, Gustafson CE, Hu B et al. Histone deficiency and accelerated replication stress in T cell aging. J Clin Invest, 2021;131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Baeken MW. Sirtuins and their influence on autophagy. J Cell Biochem, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Ge Y, Zhou M, Chen C, Wu X, Wang X. Role of AMPK mediated pathways in autophagy and aging. Biochimie, 2022;195:100–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Giordano S, Darley-Usmar V, Zhang J. Autophagy as an essential cellular antioxidant pathway in neurodegenerative disease. Redox Biol, 2014;2:82–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Chang HC, Guarente L. SIRT1 and other sirtuins in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab, 2014;25:138–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Fadini GP, Ceolotto G, Pagnin E, de Kreutzenberg S, Avogaro A. At the crossroads of longevity and metabolism: the metabolic syndrome and lifespan determinant pathways. Aging Cell, 2011;10:10–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Ruderman NB, Carling D, Prentki M, Cacicedo JM. AMPK, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest, 2013;123:2764–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Martin-Montalvo A, de Cabo R. Mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming induced by calorie restriction. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2013;19:310–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Palikaras K, Lionaki E, Tavernarakis N. Mechanisms of mitophagy in cellular homeostasis, physiology and pathology. Nat Cell Biol, 2018;20:1013–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Ma K, Chen G, Li W, Kepp O, Zhu Y, Chen Q. Mitophagy, Mitochondrial Homeostasis, and Cell Fate. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2020;8:467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Gupta SS, Wang J, Chen M. Metabolic Reprogramming in CD8(+) T Cells During Acute Viral Infections. Front Immunol, 2020;11:1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Reina-Campos M, Scharping NE, Goldrath AW. CD8(+) T cell metabolism in infection and cancer. Nat Rev Immunol, 2021;21:718–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]