Abstract

Grafting can facilitate better scion performance and is widely used in plants. Numerous studies have studied the involvement of mRNAs, small RNAs, and epigenetic regulations in the grafting process. However, it remains unclear whether the mRNA N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification participates in the apple (Malus x domestica Borkh.) grafting process. Here, we decoded the landscape of m6A modification profiles in ‘Golden delicious’ (a cultivar, Gd) and Malus prunifolia ‘Fupingqiuzi’ (a unique rootstock with resistance to environmental stresses, Mp), as well as their heterografted and self-grafted plants. Interestingly, global hypermethylation of m6A occurred in both heterografted scion and rootstock compared with their self-grafting controls. Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis showed that grafting-induced differentially m6A-modified genes were mainly involved in RNA processing, epigenetic regulation, stress response, and development. Differentially m6A-modified genes harboring expression alterations were mainly involved in various stress responses and fatty acid metabolism. Furthermore, grafting-induced mobile mRNAs with m6A and gene expression alterations mainly participated in ABA synthesis and transport (e.g. carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 1 [CCD1] and ATP-binding cassette G22 [ABCG22]) and abiotic and biotic stress responses, which might contribute to the better performance of heterografted plants. Additionally, the DNA methylome analysis also demonstrated the DNA methylation alterations during grafting. Downregulated expression of m6A methyltransferase gene MdMTA (ortholog of METTL3) in apples induced the global m6A hypomethylation and distinctly activated the expression level of DNA demethylase gene MdROS1 (REPRESSOR OF SILENCING 1) showing the possible association between m6A and 5mC methylation in apples. Our results reveal the m6A modification profiles in the apple grafting process and enhance our understanding of the m6A regulatory mechanism in plant biological processes.

Decoding N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification profiles in apple grafting reveals enhanced stress response and development, shedding light on the role of m6A in plant biological processes.

Introduction

More than 100 distinct posttranscriptional chemical modifications can decorate RNAs across all living species (Boccaletto et al. 2018). Although most RNA modifications have been identified in transfer RNA (tRNA) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA), chemical modifications are also present in messenger RNA (mRNA), such as N6-methyladenosine (m6A), N1-methyladenosine (m1A), and 5-methylcytosine (m5C) modifications (Cui et al. 2017; Zhao, Roundtree et al. 2017; Zhao, Wang, et al. 2017; Vandivier and Gregory 2018). Of these, the m6A modification is the most prevalent, internal, and reversible nucleotide alteration in eukaryotes, and it involves multiple RNA regulatory mechanisms such as translation, exon splicing, nuclear export, and mRNA stability (Zheng et al. 2013; Choi et al. 2016; Xiao et al. 2016; Zhao, Roundtree et al. 2017; Zhao, Wang, et al. 2017; Wei et al. 2018). The m6A modification has been demonstrated to be “written,” “erased,” and “read,” which are controlled by various protein complexes (Yang et al. 2018). The mammalian m6A “writer” is a multiprotein complex comprised of 3 subunits, namely, methyltransferase-like 14/3 (METTL14/3), Wilms's tumor 1-associating protein (WTAP), and vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated (VIRMA; also known as KIAA1429) cofactors (Liu et al. 2014; Ping et al. 2014). Plant m6A “writers” have been identified in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), including MTB, MTA, FIP37, and VIRILIZER (orthologs of mammalian METTL14, METTL3, WTAP, and KIAA1429, respectively) (Zhong et al. 2008; Bodi et al. 2012; Shen et al. 2016; Růžička et al. 2017). m6A modification also can be demethylated by “erasers,” AlkB and AlkB-homology (AlkBH) family proteins (Jia et al. 2011). Additionally, studies showed that evolutionarily conserved C-terminal regions (ECTs) are direct m6A readers, and they are involved in regulating leaf morphology and trichome development (Arribas-Hernández et al. 2018; Wei et al. 2018). Taken together, the m6A modification is controlled by a series of “writer,” “eraser,” and “reader” proteins, and it is involved in regulating various metabolic processes in plants.

Recent advances in antibody immunoprecipitation with high-throughput sequencing have provided perspective on m6A modification patterns and their involvement in regulating biological processes. Transcriptome-wide m6A methylome profiles of 2 accessions of Arabidopsis have revealed that m6A is enriched around the start codon and stop codon, as well as within 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs), and it shows a positive correlation between the m6A modification and mRNA abundance (Luo et al. 2014). Similarly, high-throughput m6A sequencing has revealed unique m6A methylome patterns among 3 organs (leaf, flower, and root) in Arabidopsis (Wan et al. 2015) and 2 tissues (callus and leaf) in rice (Oryza sativa) (Li et al. 2014). Based on the results of high-throughput sequencing, the characterization of m6A methylome profiles in Arabidopsis chloroplast and mitochondrion has revealed that more than 86% of the transcripts are modified by m6A in these 2 organelles (Wang, Jiang, et al., 2017; Wang, Tang, et al. 2017). Transcriptome-wide m6A methylome analysis in maize (Zea mays) has highlighted the complex interactions between m6A deposition and gene duplication, revealing that the evolution of the m6A modification is mediated by genomic duplication and evolution (Miao et al. 2020, 2022). m6A methylome profiles of the tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruit ripening process have revealed that the m6A modification is negatively correlated with gene expression and m6A demethylation modulates the transcript stability of the DNA demethylase gene SlDML2 in regulating tomato fruit ripening, which is suggestive of crosstalk between the m6A modification and DNA methylation during fruit ripening (Zhou et al. 2019). Likewise, a study of the m6A methylome during strawberry (Fragaria vesca) fruit ripening has demonstrated that the m6A modification modulates nonclimacteric strawberry fruit ripening depending on the ABA pathway, which is different from climacteric tomato fruit (Zhou et al. 2021). High-quality m6A methylomes in rice plants infected by devastating viruses have revealed that the m6A modification possibly regulates gene expression during biotic response (Zhang et al. 2021). m6A sequencing analysis was also adopted to uncover the mechanism of the m6A reader MhYTP2 in regulating MdMLO19 mRNA stability, as well as the translation efficiency of antioxidant genes, which confers powdery mildew resistance in apple (Malus hupehensis) (Guo et al. 2021). Taken together, the increasing number of studies involving transcriptome-wide m6A methylomes has revealed that the m6A modification plays essential roles in various plant biological processes, including biotic and abiotic stress responses, and fruit development and ripening processes.

Grafting, a traditional and commonly used method to fuse plant materials from 2 different plants, is applied in tree propagation and cultivation (Harada 2010). Indeed, grafting studies have demonstrated that long-distance signaling exchanges between scion and rootstock can regulate physiological and developmental processes, including leaf development, shoot branching, ion accumulation, pathogen defense, and flowering (Haywood et al. 2005; Harada 2010; Nawaz et al. 2016). Recent studies have revealed that the small RNAs, mRNAs, proteins, and small molecules (like hormones) can undergo long-distance transport between scion and rootstock (Thieme et al. 2015; Wang, Jiang, et al., 2017; Wang, Tang, et al. 2017). Several studies have identified the mRNAs and sRNAs transported through sieve tubes over long distances, including RNA movement proteins PP16 and FT (FLORAL LOCUS T), transcription factors (NACP1, GAI, BEL5, and IAA14), and siRNAs, as well as miR172 and miR399 (Harada 2010; Kehr and Kragler 2018). Considering the association between small RNAs and DNA methylation, Arabidopsis grafting experiments have demonstrated that long-distance mobile siRNAs (endogenous sRNAs or transgene-derived) can influence DNA methylation through the RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway during grafting (Tamiru et al. 2018). Indeed, mobile sRNAs from the shoot of 1 accession moving across the graft junction can regulate genome-wide DNA methylation at unmethylated sites of root cells from a different accession (Lewsey et al. 2016). Several studies have demonstrated that grafting causes extensive DNA methylation, which reveals that DNA methylation is involved in the grafting process (Wu et al. 2013; Cerruti et al. 2021; Huang et al. 2021). Although studies have demonstrated the involvement of RNAs and DNA methylation in the grafting process, it is unclear whether the m6A modification, an epigenetic mark of RNAs, can modulate the grafting process.

Apple (Malus domestica), an important fruit crop, is widely grown in temperate zones around the world. Apple propagation mainly relies on grafting-mediated clonal propagation. Malus prunifolia ‘Fupingqiuzi,’ widely used as a rootstock in China, is extremely tolerant to environmental stresses, including drought, extreme temperature, and disease. An increasing number of studies have revealed the regulatory role of m6A modification in different biological processes. However, it is unclear whether the m6A modification is involved in the grafting process. Here, we adopted the apple cultivar ‘Golden delicious,’ (Gd) which was grafted onto the rootstock M. prunifolia (Mp) ‘Fupingqiuzi’ (a unique apple rootstock with resistance to environmental stresses), and their self-grafted plants as the plant materials. Methylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeRIP-seq) with an m6A-target antibody was performed to uncover the apple m6A methylome pattern and examine its involvement in grafting. Association analyses of m6A sequencing, transcriptome, and DNA methylome data provided insights into the epigenetic control of the grafting process in apples. This transcriptome-wide study comprehensively decoded the m6A modification profile in apples and shed light on the potential m6A regulatory mechanism in the grafting process of fruit crops.

Results

Epitranscriptome-wide m6A sequencing of Gd (scion) and Mp (rootstock)

To explore the epigenetic control of the grafting process in apples, we adopted MeRIP-seq (an m6A-target antibody coupled with high-throughput sequencing), RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), small RNA sequencing (sRNA-seq), and whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) to characterize the dynamic m6A and 5mC methylomes associated with the transcriptome data. The grafting experiment was conducted on Gd seedlings, Mp seedlings, and heterografted Gd (hgGd) on Mp seedlings, as well as self-grafted Gd (sgGd) and self-grafted Mp (sgMp) seedlings, which served as controls (Fig. 1, A and B). Approximately 21 million clean reads were generated from the MeRIP-seq samples. Each immunoprecipitation sample was equipped with 1 input, which served as the m6A-seq control (Supplemental Table S1). More than 88 million clean reads were generated from RNA-seq analysis, and ∼27 million mapped reads were obtained from the 3 replicates of each sample (Supplemental Table S2). For the DNA methylome data, more than 80 million clean reads were generated by WGBS analysis, and the unique alignment yielded ∼33 to 72 million reads (Supplemental Table S3). For the sRNA-seq data, more than 11 million clean reads were generated by sRNA-seq analysis (Supplemental Table S4). Pearson's correlation coefficients of m6A MeRIP-seq, RNA-seq, and WGBS of the samples showed high correlations among the biological replicates, indicating that the data were reliable (Supplemental Fig. S1).

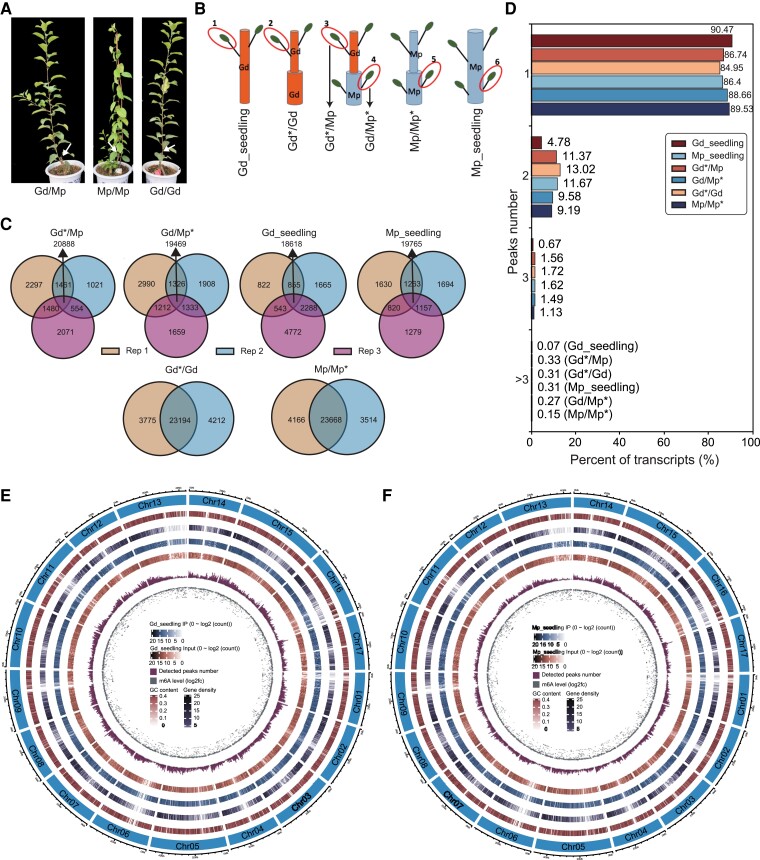

Figure 1.

Epitranscriptome-wide m6A-seq of 2 apple accessions Gd and Mp, as well as their grafting samples. A) The plant materials of Gd grafted on Mp (Gd/Mp) and self-grafted Gd (Gd/Gd) and Mp (Mp/Mp). B) The schematic diagrams of sample collection. 1, leaves of Gd_seedlings; 2, scion leaves of self-grafted Gd*/Gd; 3, scion leaves of heterografted Gd*/Mp; 4, rootstock leaves of Gd/Mp*; 5, rootstock leaves of Mp/Mp*, 6, leaves of Mp_seedlings. C) Venn diagrams presenting the overlapped m6A peak numbers and common peak proportions among biological replicates. Rep, replicate. Only those m6A peaks consistently identified in all replicates were used for the subsequent analysis. D) Proportions of m6A-modified transcripts containing various m6A peak numbers among different samples. Circos diagrams of m6A modification pattern among apple chromosomes in Gd_seedling E) and Mp_seedling F), respectively.

For m6A modifications, we first used LC-MS/MS to quantify the total m6A levels in Gd and Mp and their grafted samples (Supplemental Fig. S2). Interestingly, the mean values of the total m6A ratio in Mp samples (Mp_seedling, heterografted Mp [hgMp], and sgMp) are generally lower than that in Gd samples (Gd_seedling, hgGd, and sgGd). Considering the grafting process, the m6A ratio of hgGd seems higher than that in sgGd, which is consistent with the hgMp compared with sgMp (Supplemental Fig. S2). To further characterize the transcriptome-wide m6A profile of apples, we performed the MeRIP-seq to characterize the m6A changes during the apple grafting process. Only the m6A peaks consistently identified in all replicates were designated as high-quality m6A peaks and used for subsequent analysis. The results showed that more than 80% of the peaks were commonly identified in all biological replicates for each sample (except for Gd_seedling replicate 3 with 71%), indicating the reliability of the m6A peaks (Fig. 1C). Moreover, more than 85% of the m6A-modified transcripts contained only 1 m6A peak among these 6 samples (Fig. 1D). To further gain insights on the m6A distribution patterns of chromosomes, circos diagrams with the contents of chromosome number, GC content, gene density, read distribution of IP, read distribution of input, detected peak number, and m6A level in order from outside to inside were constructed to display the m6A methylome features among these 6 samples (Fig. 1, E and F, and Supplemental Fig. S3). The results suggested that the identified m6A peak numbers were positively associated with the gene densities and the m6A levels were negatively associated with the peak distributions (Fig. 1, E and F, and Supplemental Fig. S3).

The numbers and proportions of the m6A-modified transcripts in the mRNA-seq and MeRIP-seq data sets are provided in Supplemental Table S5. Consistent with the total m6A ratio results (Supplemental Fig. S2), the proportion of transcripts containing the m6A modification in Mp_seedling was generally lower than that in Gd_seedling (Supplemental Table S5). Considering the heterografting process, the proportions of transcripts containing the m6A in heterografted Gd and Mp were lower than that in self-grafted Gd and Mp (Supplemental Table S5). Coupled with the total m6A ratio results, we believe that the m6A modification pattern is dynamically altered during the apple grafting process. Moreover, although the proportions of m6A-modified transcripts in apples were generally lower than those in Arabidopsis leaves, flowers, and roots with proportions of 70.6%, 73.7%, and 76.7% (Wan et al. 2015), respectively, they were comparable to those of an Arabidopsis study that reported an m6A density of 51.1% (Luo et al. 2014) and a human/mouse study (up to 1/3) (Dominissini et al. 2012). The variations in the proportions may be due to the different parameters in m6A peak calling and the variety among the different species.

Unique features of the m6A methylome in apple

To gain insights into the m6A distribution pattern in the apple transcriptome, we investigated the m6A modification in various gene features. As shown in Fig. 2A, the m6A distribution in 6 apple samples showed a similar pattern with enrichment around the 3′UTR region and slight enrichment around the 5′UTR region, consistent with the Arabidopsis results of 3′UTR and start codon region m6A enrichment (Luo et al. 2014). The m6A density around the 3′UTR region in Gd_seedling was higher than that in Mp_seedling. However, the heterografted Gd/Mp* showed higher m6A enrichment in the 3′UTR than Mp/Mp*, whereas no obvious differences in the gene features were detected between Gd*/Mp and Gd*/Gd (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, we analyzed the proportion of m6A peaks located in different gene features (Fig. 2B). The m6A peaks were predominately located in the 3′UTR (48.89% to 59.45%) and coding sequence (CDS) (35.80% to 45.11%) in 2 apple accessions and their grafted samples. More than 80% of the m6A peaks were assigned to the 3′UTR and CDS, with the remaining m6A peaks associating with the 5′UTR (1.96% to 4.69%) and intergenic region (2.27% to 2.97%) (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, compared with self-grafted scion (Gd*/Gd), the proportion of m6A peaks in heterografted scion (Gd*/Mp) was lower in the 3′UTR but higher in the CDS. In contrast, the proportion of m6A peaks in heterografted rootstock (Gd/Mp*) was higher around the 3′UTR but lower in the CDS compared with self-grafted rootstock (Mp/Mp*) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

m6A distribution patterns in apple. A) Distribution of m6A in gene features including upstream 1 kilobase (Kb), 5′ UTR, CDS, 3′UTR, and downstream 1Kb. B) The proportions of m6A peaks located in different gene features including intergenic region, 5′UTR, CDS, and 3′UTR. C) IGV snapshots illustrating the representative gene transcripts harboring m6A peaks in 2 apple accessions Gd and Mp. D) Sequence logo representing the most conserved sequence motif UGUAH for m6A containing peaks in apple (H is A, C, or U). E) The proportions of UGUAC, UGUAU, and UGUAA among all 6 samples. F) The relationship between m6A and gene expression levels. Genes were sorted by their expression levels and the fractions of genes belonging to each subgroup defined by the m6A distribution pattern were analyzed in Gd_seedling and Mp_seedling. Gd*/Gd, scion leaves of Gd grafted on Gd were collected; Mp/Mp*, rootstock leaves of Mp grafted on Mp were collected; Gd*/Mp, scion leaves of Gd grafted on Mp were collected; Gd/Mp*, rootstock leaves of Gd grafted on Mp were collected. Asterisks in D) indicate the site with an m6A modification.

Additionally, we applied Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) software to display the m6A modification patterns in gene regions (Fig. 2C and Supplemental Fig. S4). The results showed that the enriched m6A peaks were mainly deposited at the 3′ end of genes, which was consistent with their distribution at the 3′UTR (Fig. 2, A and B). Interestingly, 2 adjacent genes with opposite directions sharing the 3′ region always displayed distinct m6A peaks around the 3′UTR similar to the examples presented in Fig. 2C and Supplemental Fig. S4 (MD04G1036800/MD04G103690 and MD02G1226600/MD02G1226700). A previous study has demonstrated that m6A is conservatively modified on the histone deacetylase gene HDAC6 in Arabidopsis and humans (Luo et al. 2014). The HDAC6 homologous gene in apple, MD14G1173000, also showed the m6A modification in the 3′UTR region, which suggests that the m6A modification is conserved among different species (Fig. 2C and Supplemental Fig. S4).

Moreover, we investigated the conserved m6A-modified motifs in the apple transcriptome using HOMER software. Although the conserved m6A-modified motif “RRACH” (where R is A or G and H is A, C, or U) from previous studies (Luo et al. 2014; Wang, Lu, et al. 2014; Wang, Li, et al. 2014; Duan et al. 2017) was also identified in our results, the most conserved motif was “UGUAH” in apple (Fig. 2D and Supplemental Fig. S5). We further calculated the proportions of the fifth base “H,” and the results showed that the proportion of UGUAA was the highest (47.38% to 53.98%), followed by UGUAU (45.51% to 52.04%) and UGUAC (35.23% to 40.85%) among all the samples (Fig. 2E). However, the proportions of the different motif types were comparable between heterografted and self-grafted samples (Gd*/Mp vs Gd*/Gd and Gd/Mp* vs Mp/Mp*). Interestingly, the UGUAH motif was also identified in Arabidopsis (Wei et al. 2018), tomato (Zhou et al. 2019), and maize (Miao et al. 2020). These results suggest that m6A-modified motifs may vary in different species.

Previous studies have shown that the m6A modification can affect the mRNA abundance. To examine the association between the m6A modification and gene expression, we further sorted the genes according to their expression levels and analyzed the proportions of genes belonging to each subgroup as defined by the m6A distribution patterns (Fig. 2F and Supplemental Fig. S6). The results showed that all 6 samples displayed a similar m6A distribution pattern across the different gene expression subgroups. As shown in Fig. 2F and Supplemental Fig. S6, with increasing expression levels, the proportion of genes containing the 3′UTR m6A deposition was the highest, followed by genes containing the CDS m6A deposition, suggesting that genes with higher expression levels are associated with the m6A modification in the 3′UTR and CDS. However, with increasing expression levels, the proportion of genes harboring the 5′UTR m6A deposition was the lowest with a slight rising trend at the end of the gene catalog with high expression levels (Fig. 2F and Supplemental Fig. S6).

Global hypomethylation occurs in Mp compared with Gd

To explore the functions of the m6A-modified genes in apples, we first submitted the m6A-modified genes for Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment, and the results are presented in Supplemental Fig. S7. In both Gd_seedling and Mp_seedling, most m6A-modified genes were involved in RNA-related processes such as noncoding RNA (ncRNA)/mRNA/rRNA metabolic processes, ncRNA/mRNA/rRNA processing, and RNA splicing (Supplemental Fig. S7). The m6A-modified genes were also enriched in chromatin organization, implying that the m6A modification may regulate the chromatin state, thereby affecting biological processes, as well as ribosome biogenesis, photosynthesis, and protein targeting (Supplemental Fig. S7).

To further investigate the m6A modification patterns of 2 apple accessions, we identified the differential m6A peaks by comparing the m6A methylomes of Gd_seedling and Mp_seedling. A total of 8,486 differential m6A peaks with 302 hypermethylated peaks and 8,184 hypomethylated peaks were identified in Mp_seedling compared with Gd_seedling (Fig. 3A and Supplemental Fig. S8). The overwhelming number of hypomethylated m6A peaks was indicative of the overall hypomethylation of the m6A modification in Mp_seedling versus (vs) Gd_seedling, consistent with the total m6A ratio result (Supplemental Fig. S2). As shown in Fig. 3B, 302 hypermethylated peaks were mainly distributed around the CDS (51.66%), 3′UTR (31.12%), 5′UTR (13.25%), and intergenic region (2.98%), whereas 8,184 hypomethylated peaks were highly enriched in the 3′UTR (64.39%) and CDS (32.16%) with smaller proportions in the 5′UTR (1.00%) and intergenic region (1.99%) (Fig. 3B). The hypermethylated peaks were predominant in the CDS region, whereas the hypomethylated peaks were predominant in the 3′UTR (Fig. 3B). The distribution of differential m6A peaks around the 3′UTR and CDS was consistent with that of peaks at the transcriptome-wide level (Figs. 3B and 2B). Additionally, a heatmap also displayed a similar pattern of hypomethylation in Mp_seedling compared with Gd_seedling (Fig. 3C).

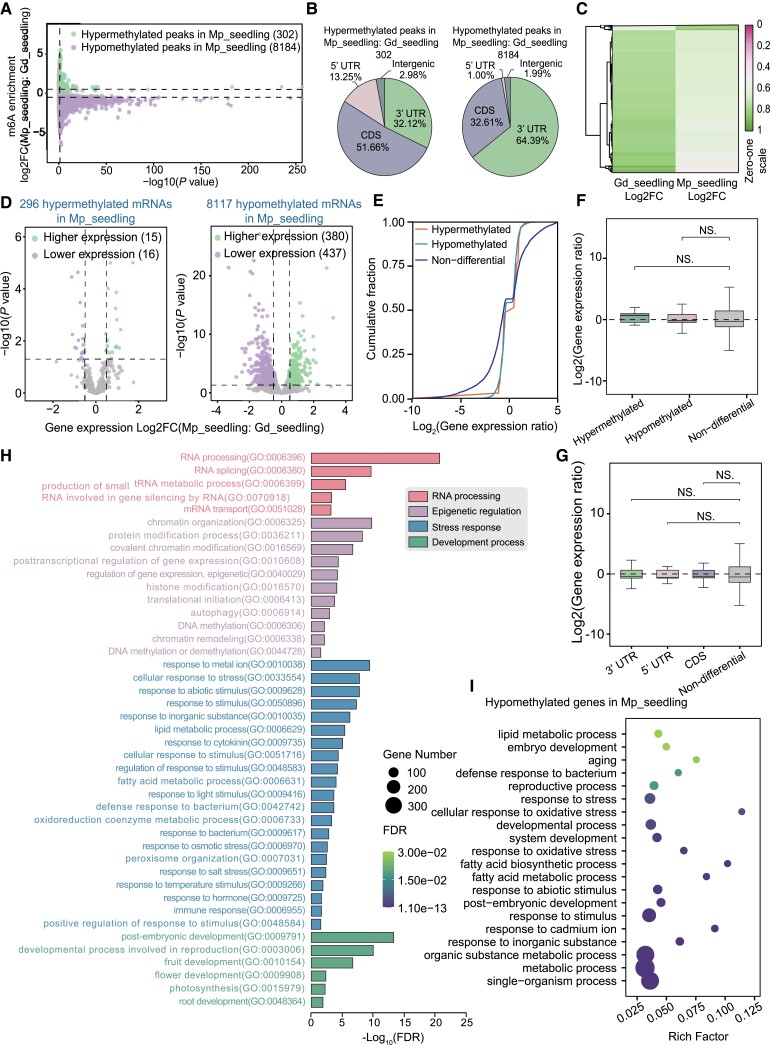

Figure 3.

Dynamic m6A methylation pattern in 2 apple accessions Gd and Mp. A) Volcano plots of hypermethylated and hypomethylated m6A peaks in Mp_seedling compared with Gd_seedling. B) Distribution of hypermethylated and hypomethylated m6A peaks among different gene features including intergenic region, 5′UTR, CDS, and 3′UTR. C) Heatmap of differential m6A enrichment in Mp_seedling compared with Gd_seedling. D) Volcano plots presenting the DEGs containing the m6A alterations in A). Green plots are genes with higher expression and purple plots are genes with lower expression. E) Cumulative distribution analysis of gene expression alterations among hypermethylated, hypomethylated, and nondifferential m6A-methylated genes. F) Boxplot of gene expression ratios among hypermethylated, hypomethylated, and nondifferential m6A-methylated genes. G) Boxplot of gene expression ratios with differentially m6A-methylated genes among different gene features (3′UTR, green box; 5′UTR, red box; CDS, blue box; nondifference, gray box). H) GO term assignments of all differentially m6A-methylated genes. I) GO term analysis of hypomethylated DEGs. Boxes in F) and G) display the median and interquartile range, and asterisks indicate significant differences based on Wilcoxon test, and statistically significant differences are indicated by *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, or NS P > 0.05.

Next, we combined the parallel transcriptomic analyses and m6A sequencing data to explore the effects of m6A modification on gene expression. Firstly, we identified 2,279 upregulated and 2,606 downregulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Mp_seedling vs Gd_seedling (Supplemental Fig. S9). We further investigated the expression alterations of differentially expressed m6A-modified genes in Mp_seedling vs Gd_seedling (Fig. 3D). The results showed that 296 hypermethylated genes contained 15 significantly upregulated and 16 downregulated DEGs, while 8,117 hypomethylated genes contained 380 significantly upregulated and 437 downregulated DEGs (Fig. 3D). The unbiased numbers of upregulated and downregulated genes among the hypermethylated or hypomethylated genes showed that the altered m6A depositions did not globally activate or suppress the mRNA abundance. Furthermore, we analyzed the whole gene expression alterations associated with m6A hypermethylated, m6A hypomethylated, and nondifferential m6A-modified genes. The results showed that the downregulated genes with hypermethylated or hypomethylated m6A depositions showed higher gene expression than that of nondifferential m6A-modified genes (Fig. 3E). However, analysis of box plots of gene expression ratios demonstrated no significant differences between hypermethylated or hypomethylated genes and nondifferential genes (Fig. 3F). Considering that the differential m6A peaks mainly distributed around the 3′UTR and CDS (Fig. 3B), we further analyzed the effects of hypermethylated or hypomethylated m6A depositions across the different gene features on their respective gene expression (Fig. 3G). Compared with the nondifferential m6A-modified genes, the m6A depositions around the 3′UTR, 5′UTR, and CDS did not show significant differences in the gene expression levels (Fig. 3G).

To further explore the biological functions of these differential m6A-modified genes in Mp_seedlings compared with Gd_seedlings, the 8,184 hypomethylated and 302 hypermethylated genes were submitted for GO term enrichment. The results showed that the differential m6A-modified genes were mainly involved in 4 processes: (i) RNA processing: RNA splicing, mRNA transport, and tRNA metabolic processes; (ii) epigenetic control and chromatin regulation: DNA methylation/demethylation, histone modification, chromatin organization and remodeling, and translational initiation; (iii) response to biotic and abiotic stresses, hormone and light, as well as lipid/fatty acid metabolism; and (iv) development: embryo, fruit, flower, and root development, as well as reproduction and photosynthesis (Fig. 3H). We proposed that the m6A modification affects environmental interactions and developmental processes by regulating RNA processing or epigenetic states. Additionally, we analyzed GO term enrichment of the hypomethylated m6A-modified genes associated with expression changes. The results revealed that these genes were enriched in response to stress and stimulus (including a defense response to bacteria, oxidative stressors, and inorganic substances), metabolic processes (mainly lipid or fatty acid metabolic processes), and developmental processes (including embryo development, aging, and reproductive processes) (Fig. 3I). In contrast, the hypermethylated m6A-modified DEGs were enriched in cellular processes, response to stress and stimulus, metabolic processes (mainly primary metabolic processes), and biological regulatory processes (Supplemental Fig. S10).

Overall hypermethylation occurred in the apple heterografting process

Grafting is widely used in tree propagation and cultivation. To gain insights into the involvement of the m6A modification in the apple grafting process, we decoded the apple m6A methylomes and compared the m6A alterations in heterografted Gd/Mp scion and rootstock (hgGd and hgMp) with their respective self-grafted controls (Gd*/Gd was described as sgGd, and Mp/Mp* was described as sgMp). Interestingly, overall hypermethylation occurred in heterografted scions (hgGd), with 6,324 hypermethylated and 569 hypomethylated peaks compared with self-grafted scions (sgGd) (Fig. 4, A and C, and Supplemental Fig. S8). A similar overall hypermethylation trend was also observed in heterografted Gd/Mp* rootstock (hgMp) compared with self-grafted Mp/Mp* (sgMp), with 3,899 hypermethylated and 979 hypomethylated peaks (Fig. 4, A and C, and Supplemental Fig. S8). These results demonstrate that heterografting might increase the proportion of m6A depositions compared with self-grafting.

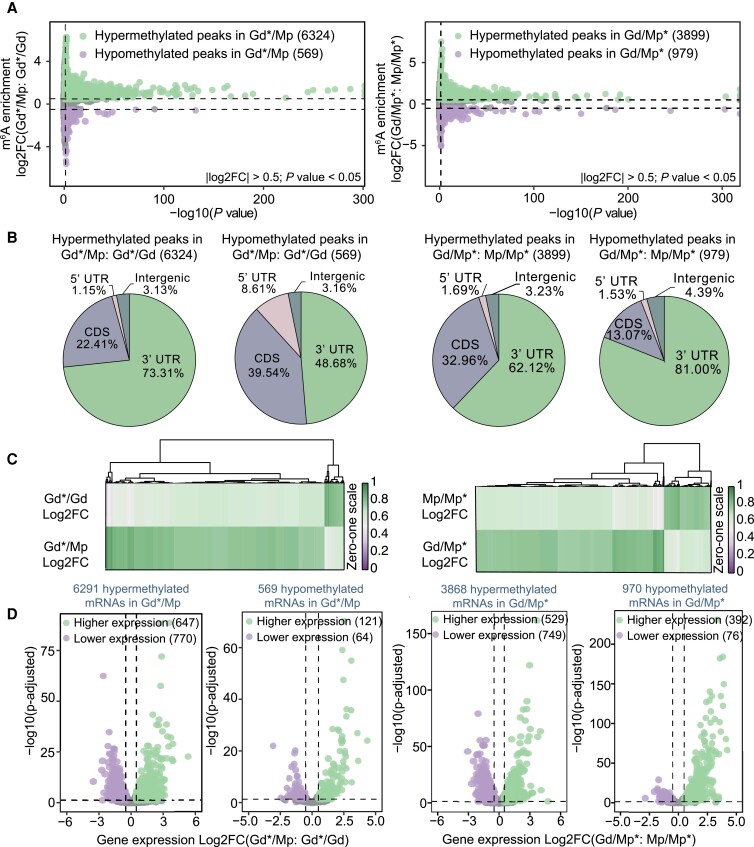

Figure 4.

Changes of m6A methylation associated with mRNA abundance during the apple grafting process. A) Volcano plots of hypermethylated and hypomethylated m6A peaks in heterografting Gd and Mp compared with their self-grafting, respectively. B) Distribution of hypermethylated and hypomethylated m6A peaks among different gene features including intergenic region, 5′UTR, CDS, and 3′UTR. C) Heat map of differential m6A enrichment between heterografting Gd and Mp and their self-grafting samples. D) Volcano plots presenting the DEGs containing the m6A alterations in A). Green plots are higher expression genes, and purple plots are lower expression genes. Gd*/Gd, scion leaves of Gd grafting on Gd; Mp/Mp*, rootstock leaves of Mp grafting on Mp; Gd*/Mp, scion leaves of Gd grafting on Mp; Gd/Mp*, rootstock leaves of Gd grafting on Mp.

Next, we further assigned the differential m6A peaks to the different gene features of the heterografted scion and rootstock and compared the results with their self-grafted controls (Fig. 4B). For the scion, 6,342 hypermethylated peaks were mainly distributed around the CDS (22.41%) and 3′UTR (73.31%), and 569 hypomethylated peaks were highly enriched in the CDS (39.54%) and 3′UTR (48.68%). Compared with hypomethylated peaks, the proportions of hypermethylated peaks were higher around the 3′UTR and lower in the CDS, and the proportion of hypomethylated peaks increased in the 5′ UTR (8.61%) (Fig. 4B). For the rootstock, 3,899 hypermethylated peaks were mainly distributed around the CDS (32.96%) and 3′UTR (62.12%), and 979 hypomethylated peaks were highly enriched in the CDS (13.07%) and 3′UTR (81.00%) (Fig. 4B). Compared with hypomethylated peaks, the proportions of hypermethylated peaks were higher in the CDS and lower in the 3′UTR (Fig. 4B), which was inconsistent with the scion results. Next, we combined the m6A modification changes with the corresponding gene expression alterations among the grafting samples. In scion, 1,602 DEGs with 768 upregulated and 834 downregulated genes were identified. Volcano plots showed that 6,291 m6A hypermethylated mRNAs had 1,417 DEGs with 647 upregulated and 770 downregulated genes, and 569 m6A hypomethylated mRNAs had 185 DEGs with 121 upregulated and 64 downregulated genes. In rootstock, 1,746 DEGs with 921 upregulated and 825 downregulated genes were identified. Among the 4,838 differential m6A genes, 3,868 hypermethylated mRNAs had 529 upregulated and 749 downregulated genes, while 970 hypomethylated mRNAs had 392 upregulated and 76 downregulated genes (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, in both scion and rootstock, the hypermethylated m6A mRNAs contained more downregulated genes than upregulated genes, while hypomethylated m6A mRNAs had more upregulated genes than downregulated genes. Cumulative distribution and box plot analyses of m6A-associated gene expression were performed to evaluate the association between m6A changes and gene expression alterations (Fig. 5, A to F). For the scion (Gd*/Mp vs Gd*/Gd), genes harboring the m6A hypomethylation exhibited significantly higher expression levels than the nondifferential genes, while genes harboring the m6A hypermethylation showed no significant difference (Fig. 5, A and B). The differential m6A-methylated genes were further divided into different gene features, including 3′UTR, 5′UTR, and CDS; however, they showed no significant difference compared with the nondifferential genes (Fig. 5C). For the rootstock (Gd/Mp* vs Mp/Mp*), genes harboring the m6A hypermethylation exhibited significantly lower expression levels than the nondifferential genes, while genes harboring the m6A hypomethylation showed higher gene expression levels (Fig. 5, D and E). Also, differential m6A genes among gene features showed no significant difference with the nondifferential genes, consistent with the scion results (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5.

Dynamic m6A methylation pattern in apple grafting samples. Cumulative distribution A) and boxplot B) analysis of gene expression alterations among hypermethylated, hypomethylated, and nondifferentially m6A-methylated genes in heterografting scion (Gd*/Mp) compared with self-grafting scion (Gd*/Gd). C) Boxplot analysis of gene expression changes among different gene features and nondifferentially m6A-methylated genes in heterografting scion (Gd*/Mp) compared with self-grafting scion (Gd*/Gd). Cumulative distribution D) and box plot E) analysis of gene expression alterations among m6A changes in heterografting rootstock (Gd/Mp*) compared with self-grafting rootstock (Mp/Mp*). F) Box plot analysis of gene expression changes among different gene features and nondifferentially m6A-methylated genes in heterografting rootstock (Gd/Mp*) compared with self-grafting rootstock (Mp/Mp*). GO term assignments for hyper–m6A-methylated DEGs in Gd*/Mp vs Gd*/Gd G) and Gd/Mp* vs Mp/Mp*H). Gd*/Gd, scion leaves of Gd grafting on Gd; Mp/Mp*, rootstock leaves of Mp grafting on Mp; Gd*/Mp, scion leaves of Gd grafting on Mp; Gd/Mp*, rootstock leaves of Gd grafting on Mp. Boxes in B), C), E), and F) display the median and interquartile range (n = 3), and asterisks indicate significant differences based on Wilcoxon test, and statistically significant differences are indicated by *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, or NS P > 0.05.

Furthermore, GO enrichment analysis was adopted to explore the biological functions of differentially m6A-modified genes during grafting. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S11, the differential m6A hypermethylated genes were mainly assigned into 4 aspects: (i) RNA processing: mRNA transport, tRNA metabolic processes, RNA splicing, and mRNA processing; (ii) epigenetics: DNA methylation and demethylation, histone modification, and chromatin/chromosome organization; (iii) stress responses: defense response to bacteria and response to stressors and stimuli, including cold, salt, temperature, osmotic stress, and light; and (iv) development: tissue development, flower development, fruit development, positive regulation of biological processes, cell division, and embryonic development. The hypomethylated genes were also mainly enriched in the aforementioned 4 aspects, including RNA splicing, chromatin modification and organization, leaf and fruit development, and stress and stimulus responses (Supplemental Fig. S11). In grafting rootstock (Gd/Mp* vs Mp/Mp*), the 3,899 hypermethylated peak genes were also mainly involved in the aforementioned 4 aspects, including RNA processing, epigenetic or chromatin regulation, stress and stimulus responses, and development processes (Supplemental Fig. S12). Genes involved in fatty acid metabolism, inorganic substance responses, and cytokinin-mediated processes were also enriched, implying their potential roles in the scion affecting the rootstock (Supplemental Fig. S12). Interestingly, hypomethylated genes were enriched in hormone transport, including auxin transport, xylem and phloem pattern formation, root development, fatty acid and wax biosynthetic processes, and stress and stimulus responses (Supplemental Fig. S12). Most of these biological processes were related to interactions between plant and environmental factors, which implied that the underground rootstock might suffer more environmental interactions. These results suggest that the m6A modification might play role in these biological processes and the scion might affect the rootstock during grafting (Supplemental Fig. S12).

Moreover, we analyzed the GO enrichments of differentially m6A-modified genes with differential expression (Fig. 5, G and H). For the scion, the hypermethylated DEGs were mainly enriched in the aforementioned 4 terms, including RNA processing, epigenetic or chromatin regulation, stress and stimulus responses, and fruit/embryo development, as well as fatty acid synthesis (Fig. 5G). In addition to these terms, m6A hypomethylated DEGs were enriched in responses to water deprivation and abscisic acid, responses to oxygen-containing compounds, and cell communication (Supplemental Fig. S13A). These results suggest that these genes might be involved in the rootstock affecting the scion during the grafting process, which contributes to the strong resistance, vigorous growth, and early flowering of the scion. For the rootstock (Gd/Mp* vs Mp/Mp*), the m6A hypermethylated DEGs were enriched in RNA processing, response to abiotic stimulus, response to cytokinin, nitrogen compound metabolic processes, and protein folding (Fig. 5H). m6A hypomethylated DEGs were mainly enriched in stress responses (including abiotic stimulus, water deprivation, heat stress, salt stress, and osmotic stress), hormone response (including jasmonic acid and abscisic acid), development (including embryo development and system development), metabolic processes (including flavonoid metabolism, fatty acid, and pigment), as well as cell communication and reproductive process (Supplemental Fig. S13B). These results suggest that the m6A modification might affect the expression of genes involved in various stress responses, hormone responses, metabolic processes, and development processes to participate in scion and rootstock crosstalk during grafting.

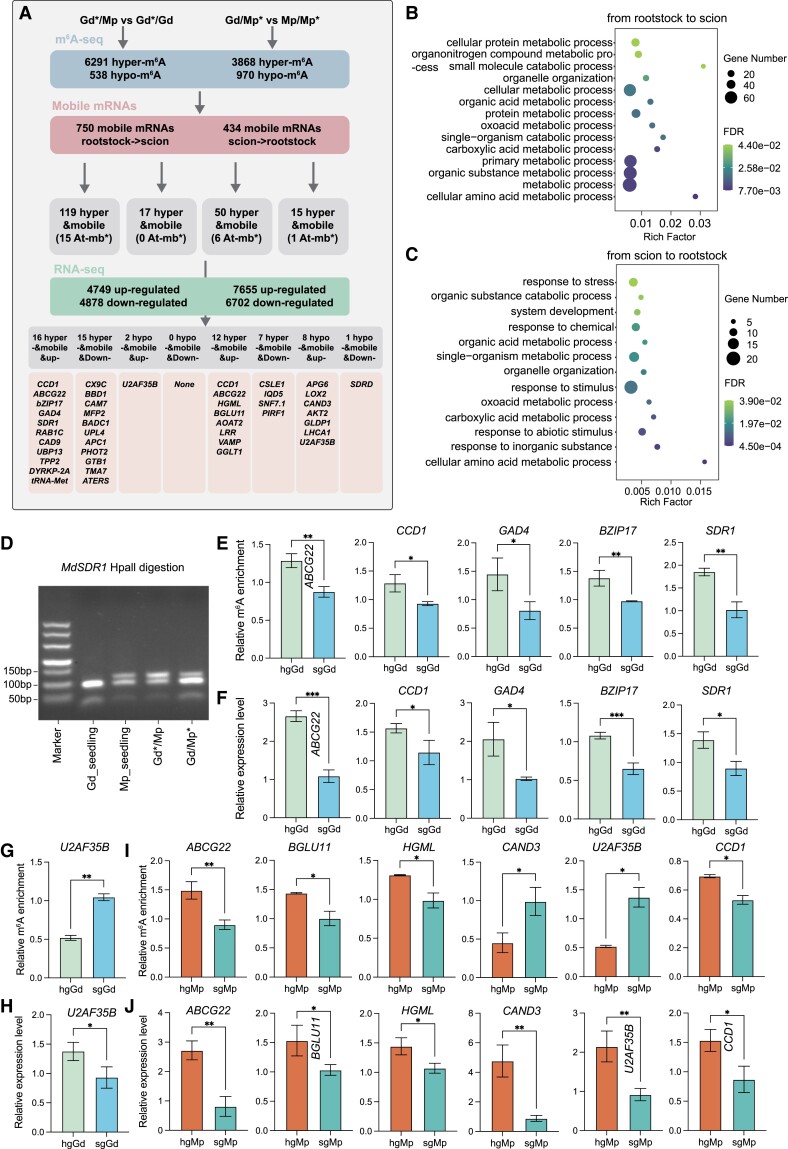

Mobile mRNAs associated with the m6A modification in apple grafting

Based on the ecotype-specific single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between scion and rootstock, we identified a total of 750 mobile mRNAs from rootstock to scion and 434 mobile mRNAs from scion to rootstock. Of these, 204 mRNAs showed 2-way movement during the grafting process. To gain insights into the involvement of m6A modification in mobile mRNAs, we combined the m6A sequencing data and mobile mRNAs (Fig. 6A). For scion (hgGd vs sgGd), 135 mobile mRNAs of rootstock to scion showed the differential m6A modification, including 119 hypermethylated and 17 hypomethylated mRNAs (Fig. 6A). These 135 mobile mRNAs were enriched in protein metabolic processes, primary metabolic processes (mainly organic acid and amino acid), and organelle organization (Fig. 6B). For rootstock (hgMp vs sgMp), 65 mobile mRNAs showed the differential m6A modification, including 50 hypermethylated and 15 hypomethylated mRNAs from scion to rootstock (Fig. 6A). However, these 65 mobile mRNAs were mainly enriched in response to stress (mainly abiotic stimulus and response to chemical and inorganic substance), system development, and organic acid metabolic processes, implying that rootstock suffers from more environmental stimuli (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

m6A modification associated with mobile mRNAs in apple grafting. A) The workflow of integration of m6A, mobile mRNAs, and RNA-seq data. hgGd, heterografting Gd (Gd/Mp); sgGd, self-grafted Gd; hgMp, heterografting Mp (Gd/Mp); sgMp, self-grafted Mp. B, C) GO enrichment analysis of differentially m6A-modified mobile mRNAs in hgGd vs sgGd B) and hgMp vs sgMp C). D) Movement of MdSDR1 mRNA from rootstock to scion in heterografting system revealed by dCAPS analysis. E) to H) Validation of the m6A enrichment levels and transcript levels in hgGd and sgGd by m6A-IP-qPCR and RT-qPCR. The biological replicates of both hgGd and sgGd were n = 3. I) Validation of the m6A enrichment levels in hgMp and sgMp by m6A-IP-qPCR. The biological replicates in the 6 mRNAs of hgMp are n = 2, while for sgMp, the biological replicates are n = 2 in U2AF35B and CCD1 and n = 3 in the rest 4 mRNAs. J) Validation of the transcript levels in hgMp and sgMp by qRT-PCR. The biological replicates of both hgMp and sgMp were n = 3. Asterisks (E to J) indicate significant differences based on a 2-tailed unpaired Student's t test, and statistically significant differences are indicated by *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, or ***P ≤ 0.001. The error bars in barplots (E to J) indicate Sd.

We further investigated the expression alterations of mobile mRNAs harboring the differential m6A modification (Fig. 6A and Supplemental Data Set 1). For hgGd vs sgGd, 16 upregulated and 15 downregulated genes were screened among the hypermethylated mobile mRNAs, while only 2 upregulated genes were identified among the hypomethylated mobile mRNAs. Notably, the 16 hyperregulated and upregulated mobile genes included carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 1 (CCD1; response to water deprivation), ATP-binding cassette G22 (ABCG22; response to water deprivation), bZIP transcription factor 17 (bZIP17; response to salt and osmotic stress), glutamate decarboxylase 4 (GAD4; defense response to fungus and flower development), short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase 1 (SDR1; defense response to pathogens), RAB GTPASE HOMOLOG 1C (RAB1C; pollen development), CINNAMYL ALCOHOL DEHYDROGENASE 9 (CAD9; lignin biosynthetic process), UBIQUITIN-SPECIFIC PROTEASE 13 (UBP13; protein deubiquitination), TRIPEPTIDYL PEPTIDASE II (TPP2; proteolysis), PLANT-SPECIFIC DUAL-SPECIFICITY TYROSINE PHOSPHORYLATION-REGULATED KINASE 2A (DYRKP-2A; protein kinase), and methionine-tRNA synthetase (tRNA-Met) (Fig. 6A and Supplemental Data Set 1). Interestingly, CCD1, ABCG22, and bZIP17 are involved in abiotic stresses, especially in water deprivation. CCD1 is the key enzyme of ABA synthesis, and it is involved in the drought response. ABCG22 encodes an ABC transporter gene, and its mutant increases water transpiration and drought susceptibility. The transcription factor bZIP17 regulates salt and osmotic stress response, and its mutant inhibits primary root elongation in response to NaCl. Additionally, GAD4 and SDR1, which are involved in the defense response to pathogens, were also screened out in this study (Fig. 6A and Supplemental Data Set 1). These results imply that these hyperregulated and upregulated mobile mRNAs from rootstock to scion can contribute to the acquisition of scion (Gd) abiotic and biotic resistance from rootstock (Mp). However, the 15 hypermobile and downregulated genes contained Cox19-like CHCH family protein (CX9C-domain protein; negatively regulated drought and light stress), bifunctional nuclease in basal defense response 1 (BBD1; ABA-mediated callose deposition, defense response to fungus, and negative regulation of transcription), calmodulin 7 (CAM7; defense response to fungus), multifunctional protein 2 (MFP2; fatty acid beta-oxidation), biotin/lipoyl attachment domain-containing protein (BADC1; negative regulation of fatty acid biosynthetic process), ubiquitin-protein ligase 4 (UPL4; protein ubiquitination, flower, and leaf development), ANAPHASE PROMOTING COMPLEX 1 (APC1; auxin homeostasis and embryo development), phototropin 2 (PHOT2; protein phosphorylation), global transcription factor group B1 (GTB1; transcription initiation and chromatin structure), TRANSLATION MACHINERY-ASSOCIATED PROTEIN 7 (TMA7; mRNA binding), and OVULE ABORTION 3 (ATERS; glutamate-tRNA synthetase) (Fig. 6A and Supplemental Data Set 1). Notably, the CX9C-domain gene was induced by low phosphate or iron, drought, and heat stress, and its mutant enhanced tolerance to drought and light stress, indicating a negative role in drought stress. For biotic stress, BBD1 and CAM7 are related to defense response to pathogens. Interestingly, MFP2 and BADC1 are involved in fatty acid process, which BADC1 negatively regulated fatty acid biosynthesis. Previous studies have revealed that fatty acid biosynthesis was closely associated with the plant response to abiotic and biotic stresses, implying that these 2 genes might affect resistance by modulating the fatty acid pathway. The hypomobile mRNAs catalog contained 2 upregulated genes in which U2AF35B is involved in photoperiodism, flowering, and mRNA splicing. For validation of m6A-seq, we examined 6 genes including ABCG22, CCD1, GAD4, BZIP17, SDR1, and U2AF35B in hgGd and sgGd using m6A-IP-qPCR. The results showed that in hgGd, the m6A levels of ABCG22, CCD1, GAD4, BZIP17, and SDR1 were significantly increased as compared with sgGd (Fig. 6E). Additionally, there was a significant decrease in the m6A level of U2AF35B in hgGd compared with sgGd (Fig. 6G). These findings are consistent with our m6A-seq results (Fig. 6, E and G). RT-qPCR analysis also showed that ABCG22, CCD1, GAD4, BZIP17, SDR1, and U2AF35B were upregulated in hgGd compared with sgGd, which is also consistent with RNA-seq results (Fig. 6, F and H). In addition, to further verify the mRNA mobility, a derived cleaved amplified polymorphic sequences (dCAPS) experiment was performed and the restriction endonuclease HpaⅡ was used to distinguish SDR1 mRNA in Gd_seedling, Mp_seedling, Gd*/Mp, and Gd/Mp* (Fig. 6D). The enzyme digestion results of SDR1 mRNA showed that Gd_seedling had 2 different fragments, while Mp_seedling, Gd*/Mp, and Gd/Mp* had the same 3 different fragments. After grafting on Mp rootstock, types of Mp fragments can be detected in Gd scion part of Gd/Mp grafting system, which indicates the SDR1 mRNA movement from the rootstock to scion. In conclusion, the migration of mRNAs from rootstock to scion with differential m6A modifications was mainly involved in abiotic (especially drought) and biotic stresses, as well as fatty acid biosynthesis and tRNA processes, suggesting their potential roles in the enhanced scion resistance affected by rootstock.

With regard to the mobility of scion to rootstock, hgMp vs sgMp combination filtered 50 hypermobile and 15 hypomobile mRNAs. Of these, 12 upregulated and 7 downregulated genes were identified in 50 hypermobile mRNAs, while 8 upregulated and 1 downregulated genes were assigned into 15 hypomobile mRNAs. Interestingly, the 12 hyperregulated and upregulated genes included CCD1 and ABCG22, which were also hyperregulated and upregulated in hgGd vs sgGd, indicating that these 2 genes might function in bidirectional communication during grafting. In addition, 3-HYDROXY-3-METHYLGLUTARYL-COA (HMGCOA) LYASE (HGML; response to various stresses, such as wounding, inorganic substance, jasmonic acid, and light stimulus), BETA GLUCOSIDASE 11 (BGLU11; response to inorganic substance and seed development), ALANINE-2-OXOGLUTARATE AMINOTRANSFERASE 2 (AOAT2; glyoxylate aminotransferase activity and lipid biosynthetic process), Leucine-rich repeat family protein gene (LRR; signal transduction), vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP; photomorphogenesis), and GOLGI GDP-L-GALACTOSE TRANSPORTER1 (GGLT1; nucleotide sugar transporter) were also identified in hgMp vs sgMp (Fig. 6A and Supplemental Data Set 1). Most of these genes are involved in stress and hormone responses, as well as lipid biosynthesis and signal transduction. The hyperregulated and downregulated genes contained CELLULOSE SYNTHASE LIKE E1 (CSLE1; cellulose synthase and defense response to disease and abscisic acid), IQ-DOMAIN 5 (IQD5; developmental growth), Sucrose Nonfermenting7-1 (SNF7.1; vesicle-mediated transport), and PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING ROPGEF 1 (PIRF1; root development) (Fig. 6A and Supplemental Data Set 1). For the 8 hyporegulated and upregulated mobile genes, we identified ALBINO AND PALE GREEN 6 (APG6; response to heat), LIPOXYGENASE 2 (LOX2; response to disease and jasmonic acid synthesis), CANDIDATE G-PROTEIN COUPLED RECEPTOR 3 (CAND3; immune system process), potassium transport 2 (AKT2; involved in Ca2+ sensitivity of the K+ uptake channel and response to ABA), glycine decarboxylase P-protein 1 (GLDP1; glycine catabolic process and response to cadmium ion), Zinc finger C-x8-C-x5-C-x3-H type family protein (U2AF35B; photoperiodism, flowering, and mRNA splicing), and photosystem I light harvesting complex gene 1 (LHCA1; light harvesting) (Fig. 6A and Supplemental Data Set 1). Notably, U2AF35B was also associated with hyporegulation and upregulation in hgGd vs sgGd (Supplemental Data Set 1). The 1 hyporegulated and downregulated mobile gene SDRD was involved in the response to inorganic substance and light stimulus (Fig. 6A and Supplemental Data Set 1). Similarly, we also examined 6 genes including ABCG22, BGLU11, HGML, CAND3, CCD1, and U2AF35B in hgMp and sgMp using m6A-IP-qPCR to verify the above m6A-seq results (Fig. 6I). The m6A-IP-qPCR results showed that the m6A levels of ABCG22, BGLU11, HGML, and CCD1 were significantly increased, while CAND3 and U2AF35B were significantly reduced in hgMp compared with sgMp, which is consistent with our m6A-seq results shown in Fig. 6A. Furthermore, RT-qPCR analysis showed that ABCG22, BGLU11, HGML, CAND3, U2AF35B, and CCD1 were all upregulated in hgMp compared with sgMp (Fig. 6J). In summary, the migratory mRNAs of scion to rootstock are mainly related to abiotic (especially water deprivation) and biotic stresses, as well as the response to inorganic substance and root development, which might contribute to the strong resistance of rootstock.

Additionally, we corresponded these differential m6A-modified mobile genes to the Arabidopsis “cell-to-cell mobile RNA” annotation (an RNA that is synthesized in 1 cell or tissue and transported to another cell or tissue). A total of 15 and 7 counterparts in Arabidopsis were annotated as mobile mRNAs in hgGd vs sgGd and hgMp vs sgMp (labeled with an asterisk in Fig. 6A), including CCD1, SDR1, MFP2, UPL4, PHOT2, LRR, CSLE1, SNF7.1, and LOX2.

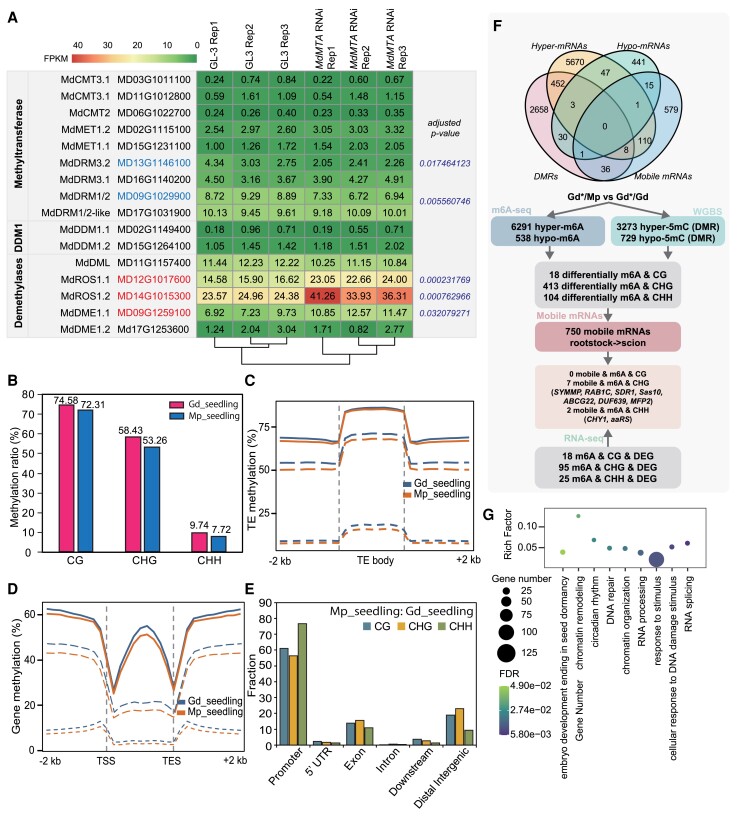

Combined analysis of DNA methylation and m6A modification in apple grafting

Previous studies showed that tomato m6A demethylase gene SlALKH2 is transcriptionally regulated by DNA methylation, and it can mediate m6A demethylation to stabilize DNA demethylase SlDML2 mRNA, indicating the interactions of m6A demethylation and DNA methylation (Zhou et al. 2019). To further explore the associations of m6A methylation and DNA methylation in apples, we investigated the expression patterns of DNA methylation–related genes in m6A methyltransferase gene MdMTA RNAi transgenic plants, which were prepared in our previous study (Hou et al. 2022). The results showed that the expression levels of genes encoding DNA demethylases increased in MdMTA RNAi plants, including MdROS1.1, MdROS1.2, and MdDME1.1 (Fig. 7A). The DNA methyltransferases MdDRMs presented slightly decreased expression levels in MdMTA downregulated lines. According to the previous studies and this study, we proposed a working model of crosstalk between m6A and 5mC modifications: the downregulated m6A methyltransferase gene MdMTA blocks the m6A establishment and activates the DNA demethylase gene MdROS and downregulated MdDMR to affect DNA methylation state (Supplemental Fig. S14).

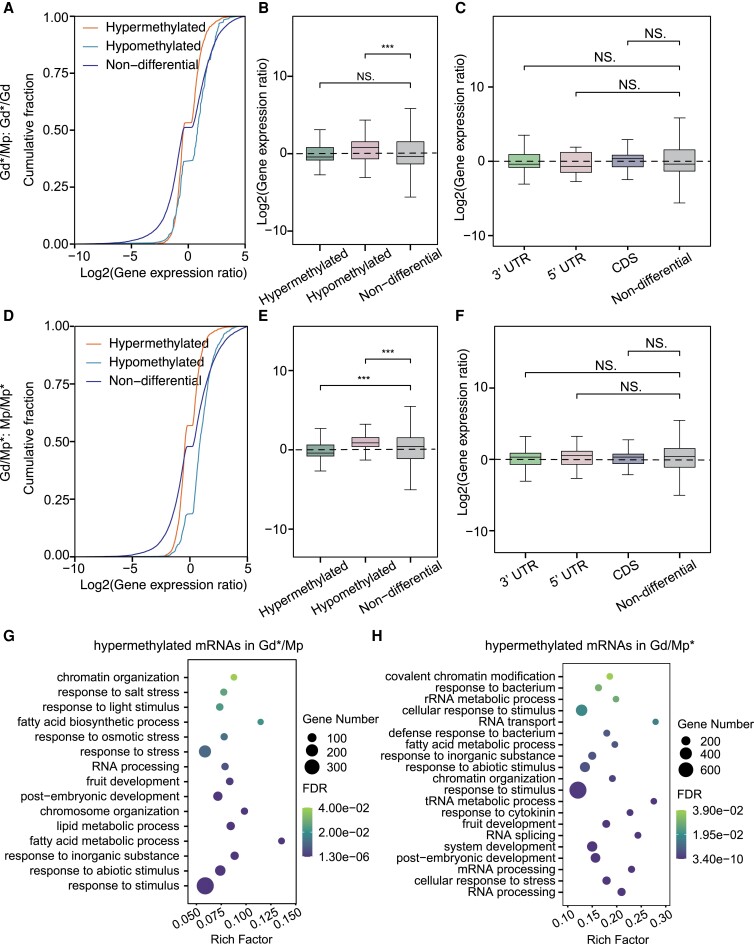

Figure 7.

Combined analysis of DNA methylation and m6A modification in apple grafting. A) The expression patterns of DNA methylation–related genes in m6A methyltransferase gene MdMTA RNAi transgenic and its wild-type plants. Compared with GL-3, significantly upregulated mRNAs expressed in MdMTA RNAi transgenic plants are labeled in red font and significantly downregulated mRNAs are labeled in blue font. B) DNA methylation ratio of Mp_seedling and Gd_seedling. DNA methylation distributions of transposable element (TE) region C), gene regions D), and their flanking sequences (−2 to 2 kb). E) Fractions of DNA methylation among different gene feature elements. F) The overlap of m6A, DNA methylation, mobile mRNAs, and RNA-seq data in hgGd vs sgGd. E) GO assignment of differentially m6A and DNA methylation genes. DEG, differentially expressed gene; WGBS, whole-genome bisulfite sequencing.

Based on the association of m6A methylation and DNA methylation, we further combined the DNA methylome alterations with the m6A methylome data. The DNA methylome differences between Gd_seedling and Mp_seeding showed that the overall CG, CHG, and CHH methylation levels of Mp_seedling were lower than those in Gd_seedling (Fig. 7B), corresponding to the m6A hypomethylation in Mp_seedling (Fig. 3A). The distribution of TE (Fig. 7C) and gene regions (Fig. 7D) also displayed lower DNA methylation levels in Mp_seedling compared with Gd_seedling. Figure 7E displays the fractions of differentially methylated regions (DMRs) among the different gene feature elements. Our previous study showed that the overall CG and CHG methylation was slightly higher and CHH methylation was slightly lower in hgGd compared with sgGd during heterografting (Li et al. 2022). The DMR-containing genes are involved in biotic and abiotic stresses, flowering process, and hormone synthesis, which may be partly responsible for better resistance to environmental factors through the grafting (Li et al. 2022). However, the rootstock of Gd/Mp presented minor variations in CG and CHG methylation and a slight decrease in CHH methylation compared with Mp_seedling (Supplemental Fig. S15). For hgGd vs sgGd, we firstly filtered the 18, 413, and 104 genes harboring both differential m6A and 5mC methylation in CG, CHG, and CHH contexts, respectively (Fig. 7F). Further GO term enrichment analysis revealed that genes containing m6A and 5mC methylation changes were mainly involved in chromatin remodeling and organization, DNA repair, RNA processing and splicing, response to stimulus, embryo development, and circadian rhythm (Fig. 7G). These results suggested that these 2 modified markers may affect chromatin and DNA/RNA processes to modulate biological processes. Additionally, 9 mobile mRNAs were screened out by overlapping m6A and 5mC differentially modified genes and mobile mRNAs from rootstock to scion. Of these, 2 genes, ABCG22 and RAB1C, were upregulated, while Sas10 and MFP2 were downregulated (Fig. 7F). Notably, ABCG22 was also identified in mobile mRNAs containing hyper-m6A methylation and higher expression, which positively regulated the drought response (Fig. 6 and Supplemental Data Set 1).

Moreover, previous studies in Arabidopsis have revealed that deletion of MTA disrupts pri-miRNA processing, leading to a decrease in the miRNA accumulation (Bhat et al. 2020). To explore the potential regulatory functions of the m6A modification on miRNAs in apples, we performed sRNA-seq on the same samples used in m6A sequencing, and a summary of sRNA-seq data is displayed in Supplemental Table S4. Next, we measured the miRNA expression changes and investigated the pri-miRNAs regions with the m6A modification regions in Gd_seedling and Mp_seedling (Supplemental Fig. S16A). The differentially expressed miRNAs results showed 31 upregulated and 42 downregulated miRNAs in Mp_seedling compared with Gd_seedling (Supplemental Fig. S16B). The overlapping regions of the differential m6A peaks and the detected pri-miRNA genes suggested a downregulated miRNA, miR7120, which may be affected by the hypo-m6A modification in Mp_seedling.

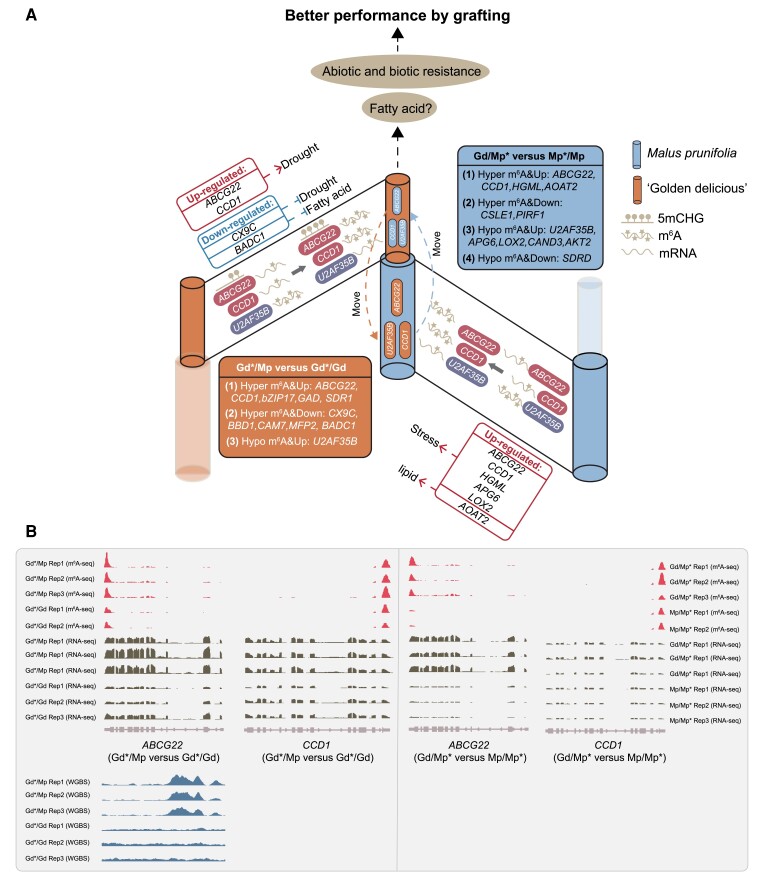

In conclusion, a working model was proposed: 2 positive drought regulators, ABCG22 and CCD1, which harbor the hyper-m6A modification and higher expression levels with predicated 2-way movement between scion and rootstock, possibly contributing to the better stress resistance in apple heterografting (Fig. 8). The upregulation of the lignin biosynthetic gene CAD9 and downregulation of the negative regulator of drought, CX9C, and fatty acid biosynthesis, BADC1, might additionally contribute to the better resistance of heterografted apple (Fig. 8). For the rootstock, the upregulation of stress-responsive genes ABCG22, CCD1, HGML, APG6, and LOX2, as well as the lipid biosynthetic gene AOAT2, might also give a better performance of heterografting (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

A hypothesis proposed in this study. A) Predicted mobile genes harbor m6A modifications and expression alterations which might contribute to the better performance of grafting plants. B) IGV software displayed the differences of m6A, gene expression, and DNA methylation among heterografting and self-grafting.

Discussion

The m6A modification in mRNA has been reported to modulate mRNA stability, splicing, and translation efficiency (Wang, Lu, et al. 2014; Wang, Li, et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2015). Recently, an increasing number of studies relating to the m6A modification in plants have been published, and the regulatory mechanism of m6A methylation was gradually uncovered in model plants, such as Arabidopsis (Luo et al. 2014; Wan et al. 2015) and rice (Zhang et al. 2021), as well as horticultural plants, such as tomato (Zhou et al. 2019), strawberry (Zhou et al. 2021), and apple (Guo et al. 2021). The conserved m6A sequence motif of Arabidopsis in an earlier study was determined to be RRACH, which was also observed in mammals (Luo et al. 2014). A later study in Arabidopsis identified the conserved motif as UGUAY (Y = A, G, U, or C) (Scutenaire et al. 2018). Additionally, the conserved m6A motif was determined as UGUAMM (M = A or C) and UGUAYY in maize (Luo et al. 2020) and tomato (Zhou et al. 2019), respectively. In strawberry, the conserved m6A motif presents a complex manner, which might include RRACH (Zhou et al. 2021). In this study, we identified both UGUAH and RRACH motifs in apple, but the UGUAH motif was the predominate one (Fig. 2D). These results were inconsistent with those of rice m6A motifs of RRACH (68%) and URUAY (28%) (Zhang et al. 2021). The conserved m6A motif in apple was relatively consistent with that in Arabidopsis, maize, and tomato. It seems that UGUA is the core sequence, and the fifth base shows variety, suggesting complexity and modified bias of the m6A modification among various species.

The m6A modification in Arabidopsis is deposited not only around the stop codon and within the 3′UTR but also around the start codon (Luo et al. 2014). However, another m6A sequencing study in the 3 organs of Arabidopsis presented only 1 predominant m6A enrichment around the stop codon and 3′UTR (Wan et al. 2015). The maize m6A methylome pattern also displayed only 1 predominant m6A enrichment around the stop codon and 3′UTR (Miao et al. 2020). Interestingly, the m6A methylome profile during strawberry fruit development showed a substantial increase in m6A depositions around the start codon and an obvious decrease in m6A depositions within the stop codon and 3′UTR during ripening (Zhou et al. 2021). As expected, our results showed a strong m6A enrichment peak around the stop codon and 3′UTR, while a weak m6A enrichment peak was observed around the 5′UTR (Fig. 2A). Taken together, the m6A modification is undoubtedly enriched around the stop codon and 3′UTR, while the 5′UTR enrichment seems to vary in different species or developmental stages of organs. A previous study has demonstrated that mRNAs containing the m6A modification at the 5′UTR could promote a cap-independent translation (Meyer et al. 2015). Although there is no study on the function of the m6A enrichment around the 5′UTR in plants, the m6A modification around the 5′UTR might play a role in regulating biological processes.

An attractive research topic of the m6A modification is its effects on mRNA abundance. In an early study, the m6A deposition was thought to promote the degradation of the mRNAs (Wang, Lu, et al. 2014; Wang, Li, et al. 2014). However, subsequent studies have revealed that the m6A modification can enhance mRNA stability and translation (Wang et al. 2015; Huang et al. 2018). An investigation of the m6A patterns of 2 Arabidopsis ecotypes revealed that the m6A modification around the start codon showed overall higher gene expression levels (Luo et al. 2014). However, studies in mammalians have demonstrated that the m6A deposition around the stop codon and 3′UTR was negatively correlated with gene expression, which was opposite to the findings in Arabidopsis (Liu et al. 2014; Wang, Lu, et al. 2014; Wang, Li, et al. 2014). In tomato, the m6A pattern is dynamic during tomato ripening, and the differential m6A modification, which was mainly deposited around the stop codon and 3′UTR, was generally negatively correlated with gene expression levels (Zhou et al. 2019). Similarly, the m6A profile also presented a dramatic change during strawberry fruit ripening. Interestingly, the differential m6A depositions in the CDS could stabilize the mRNAs, whereas the differential m6A depositions in the stop codon and 3′UTR were negatively correlated with the mRNA abundance (Zhou et al. 2021). According to previous findings, the m6A modification has distinct effects on the abundance of mRNAs depending on the m6A distribution. Differential m6A depositions in the CDS might generally stabilize mRNAs, whereas m6A depositions in the stop codon or 3′UTR might be negatively related to the gene expression (Zhou et al. 2021). The possible explanation might be that the specific sequence motif or the distribution of the m6A modification determines the recruitment of different m6A readers or RNA-binding proteins, leading the different regulatory roles. Although we observed gene expression alterations distributed by the m6A modification, significant or obvious correlations between differential m6A depositions in gene features and gene expression alterations were not identified. We believe that this may be related to differences in the organs or biological processes compared with previous studies. Notably, previous studies mainly studied the fruit development process, which could represent an underlying dramatic epigenetic reprogramming process.

Grafting is an ancient and interesting technology that can endow the scion with better resistance, flowering, development, or other phenotypes as desired by humans. Recent advancements have promoted the investigation of RNA and protein transport over a long distance via the phloem to function at sites where they are required, including siRNAs, micro RNAs, tRNAs, rRNAs, and mRNAs (Harada 2010; Kehr and Kragler 2018). A previous study has revealed that mobile small RNAs from shoots of 1 accession move across the graft junction to regulate genome-wide DNA methylation at unmethylated sites of root cells from a different accession (Lewsey et al. 2016). There is also strong evidence to support the long-distance transport of mobile siRNAs that influence DNA methylation patterns in grafted Arabidopsis plants (Molnar et al. 2010; Tamiru et al. 2018). Moreover, the loci targeted directly and indirectly by mobile siRNAs are also associated with different histone modifications (Hardcastle and Lewsey 2016). Additionally, several studies have demonstrated that grafting also caused extensive alterations in DNA methylation. For example, interspecies grafting can cause extensive and heritable changes in DNA methylation in Solanaceae plants (Wu et al. 2013). In citrus, Poncirus trifoliata as a rootstock caused global DNA demethylation and a reduction in 24 nt sRNAs in the scion compared with its autograft (Huang et al. 2021). Our previous study also revealed that global DNA methylation changes occurred among heterografted Gd/Mp and its autograft. Taken together, these results suggest that epigenetic alterations participate in grafting and rootstock–scion interactions in plants. To further explore whether the most prevalent RNA modification was also involved in the apple grafting process, we performed m6A sequencing analysis of heterografted Gd/Mp and its autografted samples (Fig. 1, A and B). Indeed, global hypermethylation of m6A was observed in heterografted Gd/Mp compared with both Gd and Mp autografts (Fig. 4, A and B). GO term enrichment analysis revealed that differential m6A-modified genes were mainly involved in 4 aspects, namely, RNA processing, epigenetic regulation and chromatin organization, response to stress or stimulus, and development processes (Fig. 5, G and H). Based on these findings, we propose that the m6A modification, as the most prevalent chemical modification in RNAs, regulates biological processes (such as development and stress response) during grafting by modulating mRNA processing and interacting with other epigenetic marks, including DNA methylation, histone modification, and chromatin organization, to modulate biological processes. When we combined m6A sequencing, mobile mRNA, and DEG data, 33 mobile mRNAs with differential expression and the m6A modification were identified, and they were mainly involved in abiotic and biotic stress, as well as fatty acid processes (Fig. 6 and Supplemental Data Set 1). Interestingly, functional annotations showed CCD1 and ABCG22 to positively regulate water deprivation responses, which were upregulated, while the downregulated CX9C had the opposite effect. Moreover, previous studies have revealed that Arabidopsis ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, AtABCG25 and AtABCG40, were identified as ABA transporters in ABA sensitivity or stomatal closure (Kang et al. 2010; Kuromori et al. 2010). It is known that CCD1 is the key enzyme in ABA synthesis (Hou et al. 2016). Therefore, we propose that the differential m6A depositions on the predicted mobile CCD1 and ABCG22 mRNAs can modulate ABA synthesis, transport, and homeostasis to contribute to the enhanced resistance to stresses in grafted scion (Fig. 8). Notably, these 2 genes were consistent in the hgGd vs sgGd and hgMp vs sgMp combinations with m6A hypermethylation and higher expression (Fig. 8), suggesting their regulatory roles in apple grafting.

As mentioned above, the grafting process involves extensive DNA methylation and m6A alterations, which trigger potential interactions between these 2 epigenetic marks. Interestingly, in tomato fruit, the m6A demethylase SlALKBH2 mediated m6A demethylation of SlDML2 and promoted its mRNA stability, leading to DNA 5mC removal and fruit ripening (Zhou et al. 2019). The downregulation of the m6A methyltransferase MdMTA in apple obviously activates the expression levels of DNA demethylase genes, MdROS1 and MdDME1, which might contribute to the DNA methylation alterations in grafting (Fig. 7 and Supplemental Fig. S10). Notably, the mobile m6A hypermethylated gene, ABCG22, also shows DNA methylation changes among hgGd vs sgGd (Fig. 8), implying that m6A and 5mC modifications might cooperatively regulate ABA homeostasis by deposition on the ABCG22 site.

Conclusion

In this study, we describe the landscape of global m6A modifications in the apple epitranscriptome among 2 apple accessions. The alterations of the m6A modification associated with the transcriptomic data were investigated in heterografting compared with self-grafting between these 2 apple accessions. The results revealed that the differential m6A-modified genes were involved in RNA processing, epigenetic regulation, response to stress or stimulus, and development process, implying the potential regulatory roles of the m6A modification in the grafting process. Further association analysis with the predicted mobile mRNAs data showed that the m6A alterations might be deposited on ABA biosynthesis and transport genes, as well as genes involved in abiotic and biotic stress responses to promote the resistance of scion (Fig. 8). Additionally, our work also shows that downregulating the m6A methyltransferase MdMTA activates DNA demethylase gene expression, implying the coordinated regulation of m6A and 5mC in apple (Supplemental Fig. S14).

Materials and methods

Plant materials and grafting

In March, we sowed the seeds of Mp ‘Fupingqiuzi’ and M. domestica Gd which have undergone stratification processing during the winter in a plant growth chamber. When the seedlings grow to about 10 cm height, they were moved to a greenhouse with normal management of water and fertilizer in the experimental station at Northwest A&F University (NWAFU), Yangling (34°20′N, 108°24′E), Shaanxi Province, China. One year later, we grafted buds from Mp on the previous prepared Mp seedlings (Mp/Mp*) and buds from M. domestica on the previous prepared Mp (Gd/Mp) and M. domestica seedlings (Gd*/Gd) in the spring, respectively. After 6 months, the grafted plants (Gd/Gd, Gd/Mp, and Mp/Mp) and Mp and M. domestica seedlings were used as experiment materials. Mature leaves (The 4th to 9th leaves from apical bud) from 1-year-old branches were collected and put into liquid nitrogen quickly for m6A-seq, BS-seq, RNA-seq, and sRNA-seq.

m6A-seq and data analysis

The mRNA m6A was sequenced by MeRIP-seq at Novogene (Beijing, China). Briefly, a total of 300 μg RNAs were extracted from the leaves. The integrity and concentration of extracted RNAs were detected using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent) and simpliNano spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare), respectively. Fragmented mRNA (∼100 nt) was incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with anti-m6A polyclonal antibody (Synaptic Systems) in the immunoprecipitation experiment. Then, immunoprecipitated or input mRNAs were used for library construction with NEBNext ultra-RNA library prepare kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs). The library preparations were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq platform with a paired-end read length of 150 bp according to the standard protocols. The sequencing of heterografted M. domestica Gd (Gd*/Mp), hgMp (Gd/Mp*), M. domestica Gd seedling (Gd_seedling), and Mp seedling (Mp_seedling) were carried out with 3 independent biological replicates. The sequencing of homografted M. domestica Gd (Gd*/Gd) and homografted Mp (Mp/Mp*) was carried out with 2 independent biological replicates.

In terms of m6A-seq data analysis, the quality of raw sequencing reads was firstly assessed by the FastQC v0.11.9 and MultiQC v1.10.1 (Ewels et al. 2016). Trimmomatic v0.39 was used to remove adaptor sequencing and bases with a quality lower than 20 in raw data (Bolger et al. 2014). Then, the remaining reads were mapped onto the apple reference genome (GDDH13 v1.1) (Daccord et al. 2017) by HISAT2 v2.1.0 using default parameters (Kim et al. 2015). BAM conversion, sorting, and indexing were performed using SAMtools v1.9, and only uniquely reads were retained for subsequently analysis (Danecek et al. 2021). Peak calling was analyzed by exomePeak2 v1.2.0 with thresholds of P value below 0.05 and log2(fold change) >1 (Liu et al. 2020). The other parameters used in exomePeak2 included fragment_length = 100, binding_length = 25, step_length = 25, and peak_width = 50. Intervene is a tool for the intersection and visualization of multiple genomic regions and gene sets based on bedtools and the consistent peak regions between biological replicates and its Venn diagram were generated by venn tool in intervene v0.6.5 (Khan and Mathelier 2017). Only the peaks consistently called in all independent biological replicates were considered as common peaks and used for subsequent analysis. The m6A motifs were identified by findMotifsGenome.pl in HOMER v4.10.0 (Heinz et al. 2010), and the running parameters of findMotifsGenome.pl were set as -mcheck all.rna.motifs -mknown known.rna.motifs -rna -mis 0 -len 4,6,8,10,12 -known. Differentially methylated peaks were determined using exomePeak2 with a threshold of P value below 0.05 and |DiffModLog2FC| above 0.5. The CMRAnnotation tool in PEA v1.1 (Zhai et al. 2018), bedtools v2.30.0 (Quinlan and Hall 2010), and deepEA (Zhai et al. 2021) were used to annotate the identified peaks to the apple genome annotation file (https://iris.angers.inra.fr/gddh13/downloads/gene_models_20170612.gff3.bz2, accessed on December 31, 2021) (Quinlan and Hall 2010; Zhai et al. 2018). Pearson correlation analyses were performed using multiBamSummary and plotCorrelation in deepTools (Ramírez et al. 2016). BAM format files were transferred into bw format files using bamCoverage in deepTools, and visualization of m6A peaks was carried out using IGV v2.10.2 (Robinson et al. 2017).

Total m6A level measurement

The total RNA m6A modification contents were detected by MetWare (http://www.metware.cn/) based on the AB Sciex QTRAP 6500 LC-MS/MS platform. One μg RNA was diluted with buffer containing S1 nuclease (Takara Biotechnology, Dalian, China), alkaline phosphatase (Takara Biotechnology, Dalian, China), and phosphodiesterase I (St. Louis, MO, USA). Then, the mixture was incubated at 37 °C. After the RNA digesting into nucleosides completely, chloroform was adopted to extract the RNA solution and the aqueous layer was submitted to the UPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis (UPLC, ExionLC AD; MS, Applied Biosystems 6500 Triple Quadrupole). The LC column was Waters ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 C18 (1.8 µm, 2.1 mm * 100 mm), and the solvent system was water (2 mm NH4HCO3): methanol (2 mm NH4HCO3) with 0.30 mL/min flow rate at 40 °C. The gradient program was as follows: 95:5 V/V at 0 min, 95:5 V/V at 1 min, 5:95 V/V at 9 min, 5:95 V/V at 11 min, 95:5 V/V at 11.1 min, and 95:5 V/V at 14 min. The linear ion trap (LIT) and triple quadrupole (QQQ) scans were acquired on a triple quadrupole–linear ion trap mass spectrometer (QTRAP 6500+ LC-MS/MS System), equipped with an ESI Turbo ion-spray interface, controlled by Analyst 1.6.3 software (Sciex) operating in positive ion mode. The adenosine (A) and m6A standards were purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China) and Berry & Associates Inc. (Michigan, USA). The stock solutions of standards were prepared at the concentration of 4 mm in Milli-Q water and diluted with Milli-Q water to working solutions before analysis. Different concentrations of A and m6A standards with 0.0005, 0.001, 0.002, 0.005, 0.02, 0.05, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500, 1,000 pmol were adopted to generate the standard curve, and the r (coefficient of correlation) was 0.99444 (A) and 0.99887 (m6A). The total m6A level was calculated by m6A/A × 100% for the sample measurement.

RNA-seq and data analysis

Total RNAs were extracted using the CTAB method (Porebski et al. 1997), and strand-specific RNA-seq libraries were generated for the Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform with 150 bp paired-ends from M. domestica Gd seedlings, Mp seedlings, heterografted M. domestica Gd plants, hgMp plants, homografted M. domestica Gd plants, and homografted Mp plants.

Sequences in clean data were aligned to GDDH13 v1.1 genome sequence using HISAT2. Postprocessing including BAM conversion, sorting, and indexing was performed using SAMtools v1.9. Read counting within genes was analyzed with HTSeq v0.12.4 using the gene annotation file (Anders et al. 2015). Length of genes was calculated by GenomicFeatures v1.42.3, and fragments per kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped (FPKM) values were obtained by TBtools (Lawrence et al. 2013; Chen et al. 2020). DEGs were identified by DESeq2 v1.30.1 with a threshold of an adjusted P value below 0.05 and | log2(fold change) | >0.5 (Love et al. 2014). Heatmaps of gene expression levels were created using pheatmap v1.0.12 (Kolde and Kolde 2015). GO enrichment analyses were performed using agriGO v2.0 and clusterProfiler v3.18.1 (Tian et al. 2017; Wu et al. 2021).

BS-seq and data analysis

DNA samples were fragmented to a mean size of ∼350 bp using a bioruptor (Covaris S220). DNA fragments were blunt-ended, added dA at the 3′-ends, and then added adapters. The procedure was carried out in accordance with the Illumina manufacturer instruction. Adapter-added DNA were bisulfite converted. Bisulfite-treated DNA was PCR amplified with 16 cycles and then pair-end sequenced using Illumina high-throughput sequencer HiSeq 2500.

Bismark v0.22.3 (Krueger and Andrews 2011) software was used to perform alignments of bisulfite-treated reads to a reference genome (-X 700 –dovetail). The reference genome was firstly transformed into bisulfite-converted version (C-to-T and G-to-A converted) and then indexed using bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg 2012). Sequence reads were also transformed into fully bisulfite-converted versions (C-to-T and G-to-A converted) before they are aligned to similarly converted versions of the genome in a directional manner. Sequence reads that produce a unique best alignment from the 2 alignment processes (original top and bottom strand) are then compared with the normal genomic sequence, and the methylation state of all cytosine positions in the read is inferred. The same reads that aligned to the same regions of genome were regarded as duplicated ones. The sequencing depth and coverage were summarized using deduplicated reads. The results of methylation extractor (bismark_methylation_extractor, – no_overlap) were transformed into bigWig format for visualization using IGV browser. The sodium bisulfite noncoversion rate was calculated as the percentage of cytosine sequenced at cytosine reference positions in the lambda genome. DNA methylation calling files of 3 methylation sequence contexts (CG, CHG, and CHH) information were generated by methylKit R package (Akalin et al. 2012). For each sample, bases with coverage more than 99.9th percentile and below 4× were filtered out. Differentially methylated regions were also identified by methylKit, with a 5,000 bp sliding window and 1,000 bp step-length. Only regions with q value lower than 0.05 and percentage of methylation difference satisfying certain conditions (CG > 40%, CHG > 20%, and CHH > 10%) were considered as a significant DMR. ChIPseeker was used to annotated DMRs to the promoter and gene body regions. GO enrichment analyses of DMRs were performed by agriGO v2.0 (Tian et al. 2017).

Long-distance mobile mRNA identification