Abstract

For PCR detection of Coxiella burnetii in various clinical specimens we developed a sample preparation method in which silica binding of DNA was used. This method was found to be fast, easily performed with large numbers of samples, and equally sensitive for all of the specimens tested (livers, spleens, placentas, heart valves, milk, blood). The DNA preparation method described here can also be used as an initial step in any PCR-based examination of specimens. The procedure was tested with more than 600 milk samples, which were taken from 21 cows that were seropositive for C. burnetii and reportedly had fertility problems (and therefore were suspected of shedding the agent through milk intermittently or continuously). Of the 21 cows tested, 6 were shedding C. burnetii through milk. Altogether, C. burnetii DNA was detected in 6% of the samples. There was no correlation between the shedding pattern and the serological results.

Coxiella burnetii is the causative agent of Q fever, a zoonosis that occurs worldwide (12). Infected animals, especially livestock, are considered the most important source of transmission to humans (9). Whereas animals in general show no clinical signs of infection except occasional abortions and other problems with reproduction, C. burnetii can cause serious illness in humans. This agent is very resistant to environmental influences, and even a single infective particle can initiate an infection in the animal model (16).

The significance of infection via the oral route (e.g., by drinking unpasteurized milk) is still a subject of discussion (2, 5, 7, 20, 22). Even if the average level secreted is much lower, up to 105 coxiellae/ml can be shed in bovine milk during several lactation periods (3, 20, 23). Therefore, a specific and sensitive diagnostic system is necessary to detect even small numbers of coxiellae.

Cell culture is still used as a sensitive tool for routine detection of C. burnetii, which is an obligately intracellular bacterium, but this method is comparatively time-consuming. A capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is also routinely used for diagnosis of C. burnetii infections (24); this method is faster than cell culture tests, but the detection limit is not completely satisfactory, considering the low level of shedding and the minimum infectious dose of C. burnetii.

PCR is a highly sensitive and specific detection method that has been used previously to trace C. burnetii in clinical samples (6, 13, 14, 26, 27). A PCR performed with primers based on a repetitive, transposonlike element (Trans-PCR) (26) proved to be highly specific and sensitive, but extraction of DNA from milk samples took considerable effort and there was a high risk of contamination due to the numerous preparation steps.

Techniques in which a silica matrix is used have been used successfully to purify bacterial DNA from various sources for PCR (4, 8, 15, 25). Therefore, we developed a procedure in which a silica matrix was used for DNA extraction in this study, and this procedure was combined with the Trans-PCR to detect C. burnetii. Our goal was to develop a rapid, inexpensive, safe, very sensitive diagnostic method to detect C. burnetii in a variety of clinical specimens. In addition, application of this new method to milk samples was intended to show the suitability of the new system for routine diagnostics and to gather new information about the shedding of C. burnetii through bovine milk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and growth conditions.

C. burnetii Nine Mile phase I was grown in Buffalo green monkey cell cultures as previously described (1) and was used to contaminate specimens. The Buffalo green monkey cells were propagated in Eagle’s minimal essential medium and were inoculated with C. burnetii. Cell culture supernatants were harvested weekly and were sonicated to release the infectious agent from the cells. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and the bacterial pellet was resuspended in 0.15 M NaCl containing 0.04% NaN3. The coxiellae were heat inactivated (80°C, 15 min), and the number of coxiellae in each suspension was determined by measuring the optical density at 420 nm. The concentration of rickettsial cells was calculated by using a previously determined standard curve. Rickettsial suspensions were stored at 4°C until they were used.

Samples.

Blood, milk, bovine placenta, porcine heart valve, cattle liver, and sheep spleen samples were tested. Livers, spleens, and heart valves were provided by the local abattoir. Placentas, blood, and milk were kindly donated by the local obstetric and gynecological clinic for animals. Capture ELISA- and PCR-negative samples were kept at −20°C and used for artificial contamination or as negative controls.

The milk samples used in the survey were collected daily from 21 cows on four dairy farms and were stored at −20°C. Reduced fertility had been reported for the herds. The cows selected were found to be serologically positive in previous examinations, as determined by ELISA or CFT. There was no indication of mastitis in the cows examined, and milk samples showed physiological consistency.

DNA extraction.

Portions (25 mg) of the animal tissues mentioned above were mechanically homogenized in 180 μl of phosphate-buffered saline. For milk and blood samples, a 200-μl sample volume was used. Cells were lysed with proteinase K (final concentration, 200 μg/ml) at 56°C overnight. DNA was prepared with a Prep-A-Gene purification kit (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) by using 10 μl of silica matrix. DNA was eluted from the silica matrix by adding 100 μl of Prep-A-Gene elution buffer. To increase the yield, DNA was eluted at 56°C for 5 min and centrifuged again. One microliter of supernatant containing DNA was used for amplification.

The samples used for sensitivity tests were contaminated with 104 to 100 coxiellae/sample. The samples used as positive controls were contaminated with 104 particles/sample. The controls were treated like the samples. Each milk sample was tested in triplicate.

Oligonucleotides.

Primers Trans1 (5′-TAT GTA TCC ACC GTA GCC AGT C-3′), Trans2 (5′-CCC AAC AAC ACC TCC TTA TTC-3′) (26), Trans3 (5′-GTA ACG ATG CGC AGG CGA T-3′), and Trans4 (5′-CCA CCG CTT CGC TCG CTA-3′) were purchased from MWG Biotech (Ebersberg, Germany).

PCR assay.

The Trans-PCR was performed by using the previously described protocol (26) except that the thermal cycler program was modified. Primers Trans1 and Trans2 flanked a 687-bp target sequence in a transposonlike repetitive region of the C. burnetii genome.

One microliter of each sample was used for PCR amplification. The total reaction volume was 20 μl, and each reaction mixture contained each primer at a concentration of 1 μM, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) at a concentration of 200 μM, reaction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9.0], 8 mM ammonium sulfate, 1.5 mM MgCl2), and 0.2 U of Tfl DNA polymerase (Biozym, Hameln, Germany). The DNA from 104 coxiellae and double-distilled water instead of DNA were used to prepare positive and negative controls, respectively.

PCR assays were performed with a model 9600 thermal cycler (ABI/Perkin-Elmer, Weiterstadt, Germany) under the following conditions: five cycles consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 77 to 69°C (the temperature was decreased 2°C between consecutive steps) for 15 s, and extension at 77°C for 1 min and then 38 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 67°C for 30 s, and extension at 77°C for 1 min. Ten microliters of the PCR product was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining and UV transillumination.

Sequencing.

Nonradioactive sequencing reactions were performed with a PRISM ready-reaction dye-deoxy terminator cycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer/ABI) as recommended by the manufacturer.

Sequence analysis.

A DNA sequence analysis was performed with the DNASTAR software package (DNASTAR Inc., London, United Kingdom).

RESULTS

PCR sensitivity.

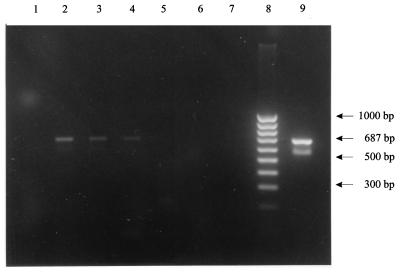

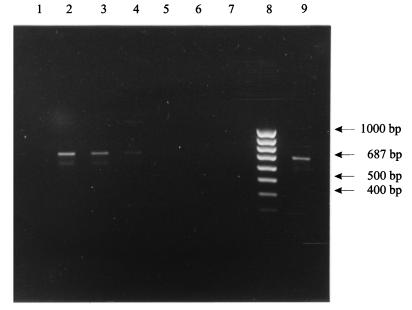

The analytical sensitivity of the Trans-PCR was found to be 100 (sometimes even 10−1) C. burnetii particles per reaction mixture. The sensitivity tests performed with artificially contaminated clinical specimens revealed detection limits of 4,000 particles/g of tissue (Fig. 1) and 500 particles/ml when blood or milk was used (Fig. 2). These values correspond to 1 particle per PCR mixture.

FIG. 1.

Sensitivity of the C. burnetii-specific Trans-PCR with liver samples after DNA preparation with silica matrix. Lane 1, negative control with liver; lane 2, 4 × 105 C. burnetii particles/g of liver; lane 3, 4 × 104 C. burnetii particles/g of liver; lane 4, 4 × 103 C. burnetii particles/g of liver; lane 5, 4 × 101 C. burnetii particles/g of liver; lane 6, 4 × 100 C. burnetii particles/g of liver; lane 7, negative control without liver; lane 8, 100-bp DNA ladder; lane 9, positive control without liver.

FIG. 2.

Sensitivity of the C. burnetii-specific Trans-PCR with milk samples after DNA preparation with silica matrix. Lane 1, negative control with milk; lane 2, 5 × 104 C. burnetii particles/g of milk; lane 3, 5 × 103 C. burnetii particles/ml of milk; lane 4, 5 × 102 C. burnetii particles/ml of milk; lane 5, 5 × 101 C. burnetii particles/ml of milk; lane 6, 5 × 100 C. burnetii particles/ml of milk; lane 7, negative control without milk; lane 8, 100-bp DNA ladder; lane 9, positive control without milk.

Sequencing.

To verify the identity of the PCR amplicon, it was sequenced completely by using PCR primers Trans1 and Trans2, as well as two internal primers (Trans3 and Trans4). In all cases the sequence of the amplicon was identical to the sequence in the EMBL/GenBank database (accession no. M80806).

Detection of C. burnetii DNA in clinical milk samples.

During the 1-month survey performed with seropositive cows, only 6 of the 21 cows examined excreted coxiellae in milk; 2 of the 21 cows shed coxiellae through milk once, 1 animal shed coxiellae on 2 days, 1 animal shed coxiellae on 3 days, and 1 animal shed coxiellae on 6 days. Usually, shedding was not coherent. Only one cow exhibited nearly continuous shedding of the agent through milk for 23 days. There was no correlation between the serological results and the pattern of coxiellae shedding in milk, nor did we observe a relationship between the last calving date and the shedding of C. burnetii.

DISCUSSION

The suitability of a detection method for routine diagnostics depends on several factors, such as specificity, sensitivity, expense, amount of time, and applicability to large numbers of clinically relevant specimens. The sample preparation procedure described here has been shown to work equally well with all materials considered to be important for diagnosis of C. burnetii infections. Placenta and fetal tissues, like liver or spleen tissues, have to be examined after abortions suspected to be due to coxiellosis. Examination of blood is necessary to prove coxiellaemia. In the case of chronic Q fever in humans, liver and heart valves can be sites of colonization (18). As human tissues were not available, the animal equivalents were used in our experiments. Because of public health concerns, milk is frequently examined, particularly when unpasteurized milk is used commercially. With the established technique described here a large number of samples can be examined simultaneously; up to 64 samples at a time were processed easily in this study. The results were available in 1 day, including the time required for sample preparation (0.5 to 1.5 h), PCR, and documentation. Depending on the number of samples, the working time was about 2 to 4 h. Hence, the method used in this study is faster than any previously described procedure for detection of C. burnetii. In addition, our method is inexpensive compared with other methods used to prepare samples for PCR. Thus, the technique described here is easily applicable to everyday routine diagnostics and to larger epidemiological studies of C. burnetii.

However, the sensitivity of our method proved to be inferior to the sensitivity obtained with the sample preparation method originally described for detection of C. burnetii by PCR (26). The binding capacity and reaction volume allowed DNA preparation from samples only as large as 200 μl and 25 mg, respectively. On the other hand, there is no minimum sample size, so even biopsy samples are suitable for the test.

During purification of DNA PCR inhibitors were copurified. Therefore, the recommended elution volume (10 μl) had to be increased (to 100 μl) to dilute the inhibitors. The detection limit was determined to be 4,000 coxiellae/g of tissue. At least when placentas are examined, this limit is sufficient, as it has been reported that large numbers of C. burnetii are harbored in the uterus and amniotic fluid of infected cows (23). Little is known about the average level of the agent in other tissues.

In previous studies (19) the concentration of coxiellae in milk was determined as infectious units by using guinea pigs as the animal model. Schaal (19) found that milk from infected cows contained 102 to 104 infectious units/ml. Assuming that infection of guinea pigs usually requires more than a single coxiella cell, the PCR detection limit, 500 coxiellae/ml of milk, covers the expected amount of agent shed through milk. Furthermore, the PCR detects not only infectious agents but nonviable agents as well. After all, the method described above is more sensitive than capture ELISA (detection limit, 2,000 coxiellae per assay) and is much more rapid and convenient than cell culture, in which at least 6 days of examination is required for diagnostic results (18). Since the method described here is not specific for C. burnetii DNA, it may be useful for diagnosing infections with other bacteria as well. This is in contrast to preparation methods in which immunomagnetic separation is used (13), which selectively purify specific DNA.

The results obtained for milk samples from 21 cows proved that the system could detect coxiellae in naturally infected specimens. This is important as C. burnetii is a strictly intracellular agent (16). Findings obtained with artificially contaminated samples containing only extracellular C. burnetii particles cannot simply be transferred to clinical samples. Besides, this survey confirmed the suitability of the test for routine diagnostics.

The previously reported percentages of C. burnetii seropositive cows that shed the agent through their milk range from 8.3 to 90% (2, 5). These values were based on detection of coxiellae with the capillary agglutination test (11, 22) or animal experiments (19, 20, 22). Furthermore, in the present study seropositive cows were selected by ELISA, whereas in the previous surveys CF was used for serological tests. The great differences in the results of the previous studies may be due to these differences. In this study C. burnetii was detected in milk samples from 6 of the 21 cows tested. The shedding of coxiellae in milk was intermittent for all of the positive cows, which is consistent with previous studies (3, 5, 20). It is important that shedding of the agent did not occur in a visible pattern. This observation indicates that fixing dates for examination of milk may result in false negatives. Therefore, in the future, serological surveys of herds from which coxiella-free milk is required might not be necessary.

An examination of calving dates revealed no relationship between calving and shedding of C. burnetii. Such a relationship is possible as the occurrence of C. burnetii in milk reportedly requires a fully developed mammary gland (21) and the blood titer of antibodies against coxiella rises after birth (10). Coxiellae might be concentrated in the mammary gland during breaks in lactation and subsequently may be shed at the beginning of a new lactation period. However, the size of this survey does not allow any statistical statement; our data provide only hints about the conditions of shedding of C. burnetii through bovine milk. Further studies that include a statistically significant number of animals and take factors like size of herds, birth, diseases, and medication into consideration will be necessary to obtain complete information about the course of shedding.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arens M. Kontinuierliche Vermehrung von Coxiella burnetii durch persistierende Infektion in Buffalo-Green-Monkey (BGM)-Zellkulturen. Zentbl Vetmed Reihe B. 1983;30:109–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson W W, Brock D W, Mather J. Serologic analysis of a penitentiary group using raw milk from a Q fever infected herd. Public Health Rep. 1963;78:707–710. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biberstein E L, Behymer D E, Bushnell R, Crenshaw G, Riemann H P, Franti C E. A survey of Q fever (Coxiella burnetii) in California dairy cows. Am J Vet Res. 1974;35:1577–1582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dupon M, Cazenave J, Pellegrin J L, Ragnaud J M, Cheyrou A, Fischer I, Leng B, Lacut J Y. Detection of Toxoplasma gondii by PCR and tissue culture in cerebrospinal fluid and blood of human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2421–2426. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2421-2426.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durand M P. L’excrétion lactée et placentaire de Coxiella burnetii, agent de la Fièvre Q, chez la vache. Importance et prévention. Bull Acad Natl Med (Paris) 1993;6:935–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frazier M E, Mallavia L P, Samuel J E, Baca O G. DNA probes for the identification of Coxiella burnetii strains. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1990;590:445–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb42253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gouverneur K, Schmeer N, Krauss H. Zur Epidemiologie des Q-Fiebers in Hessen: Untersuchungen mit dem Enzymimmuntest (ELISA) und der Komplementbindungsreaktion (KBR) Berl Muench Tieraerztl Wochenschr. 1984;97:437–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kox L F, Rhietong D, Miranda A M, Udomsantisuk N, Ellis K, van Leeuwen J, van Heusden S, Kuijper S, Kolk A H. A more reliable PCR for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:672–678. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.672-678.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang G H. Coxiellosis (Q-fever) in animals. In: Marrie T J, editor. Q-fever: The disease. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1990. pp. 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lange S, Söllner H, Hofmann J, Lange A. Q-Fieber-Antikörper-Verlaufsuntersuchung beim Rind unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Trächtigkeit. Berl Muench Tieraerztl Wochenschr. 1992;105:260–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luoto L. A capillary agglutination test for bovine Q-fever. J Immunol. 1953;71:226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marrie T J. Epidemiology of Q-fever. In: Marrie T J, editor. Q-fever: the disease. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1990. pp. 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muramatsu Y, Maruyama M, Yanase T, Ueno H, Morita C. Improved method for preparation of samples for the polymerase chain reaction for detection of Coxiella burnetii in milk using immunomagnetic separation. Vet Microbiol. 1996;51:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(95)00203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muramatsu Y, Yanase T, Okabayashi T, Ueno H, Morita C. Detection of Coxiella burnetii in cow’s milk by PCR–enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay combined with a novel sample preparation method. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2142–2146. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2142-2146.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noordhoek G T, Kaan J A, Mulder S, Wilke H, Kolk A H J. Routine application of the polymerase chain reaction for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical samples. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:810–814. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.9.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ormsbee R, Peacock M, Gerloff R, Tallent G, Wilke D. Limits of rickettsial infectivity. Infect Immun. 1978;19:239–245. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.1.239-245.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raoult D, Levy P Y, Harlé J R, Etienne J, Massip P, Goldstein F, Micoud M, Beytout J, Gallais H, Remy G, Capron J P. Chronic Q fever: diagnosis and follow up. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1990;590:51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb42206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raoult D, Vestris G, Enea M. Isolation of 16 strains of Coxiella burnetii from patients by using a sensitive centrifugation cell culture system and establishment of the strains in HEL cells. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2482–2484. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.11.2482-2484.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaal E. Die hygienische Bedeutung von Rickettsien (Coxiella burnetii) in Lebensmitteln tierischer Herkunft. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1972;97:699–704. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1107428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaal E. Zur Kontamination der Milch mit Rickettsien. Tieraerztl Umsch. 1980;35:431–438. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaal E, Schaaf J. Erfahrungen und Erfolge bei der Sanierung von Rinderbeständen mit Q-Fieber. Zentbl Vetmed Reihe B. 1969;16:818–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaal E H, Schäfer J. Zur Verbreitung des Q-Fiebers in einheimischen Rinderbeständen. Dtsch Tieraerztl Wochenschr. 1984;91:52–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schliesser T. Zur Epidemiologie und Bedeutung des Q-Fiebers bei Tieren. Wien Tieraerztl Monschr. 1991;78:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thiele D, Karo M, Krauss H. Monoclonal antibody based capture-ELISA/ELIFA for detection of Coxiella burnetii in clinical specimen. Eur J Epidemiol. 1992;8:568–574. doi: 10.1007/BF00146378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tola S, Angioi A, Rocchigiani A M, Idini G, Manunta D, Galleri G, Leori G. Detection of Mycoplasma agalactiae in sheep milk samples by polymerase chain reaction. Vet Microbiol. 1997;54:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(96)01269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willems H, Thiele D, Fröhlich-Ritter R, Krauss H. Detection of Coxiella burnetii in cow’s milk using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) J Vet Med Ser B. 1994;41:580–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1994.tb00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuasa Y, Yoshiie K, Takasaki T, Yoshida H, Oda H. Retrospective survey of chronic Q fever in Japan by using PCR to detect Coxiella burnetii DNA in paraffin-embedded clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:824–827. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.824-827.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]