Abstract

Engineered T cells expressing chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) have been proven as efficacious therapies against selected hematological malignancies. However, the approved CAR T cell therapeutics strictly rely on viral transduction, a time- and cost-intensive procedure with possible safety issues. Therefore, the direct transfer of in vitro transcribed CAR-mRNA into T cells is pursued as a promising strategy for CAR T cell engineering. Electroporation (EP) is currently used as mRNA delivery method for the generation of CAR T cells in clinical trials but achieving only poor anti-tumor responses. Here, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) were examined for ex vivo CAR-mRNA delivery and compared with EP. LNP-CAR T cells showed a significantly prolonged efficacy in vitro in comparison with EP-CAR T cells as a result of extended CAR-mRNA persistence and CAR expression, attributed to a different delivery mechanism with less cytotoxicity and slower CAR T cell proliferation. Moreover, CAR expression and in vitro functionality of mRNA-LNP-derived CAR T cells were comparable to stably transduced CAR T cells but were less exhausted. These results show that LNPs outperform EP and underline the great potential of mRNA-LNP delivery for ex vivo CAR T cell modification as next-generation transient approach for clinical studies.

Keywords: lipid nanoparticles, electroporation, mRNA delivery, CAR T cells, T cell engineering

Graphical abstract

Kitte and colleagues achieved reprogramming of donor-derived immune cells to find and eliminate diseased cells via mRNA encoding chimeric antigen receptors (CAR). In a head-to-head comparison, they determined that transporting mRNA in lipid nanoparticles is the optimal method for transient generation and functionality of CAR T cells.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) engineered T cells are considered as a promising tool for cancer therapy given by their high specificity and curative potential.1 In fact, six CAR T cell products are already approved by the Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency for the treatment of hematological cancers in 2023, four of them targeting CD19 in selected B cell malignancies.2 For CAR T cell therapy, patient T cells are isolated and genetically modified to express the CAR on their surface, and the resulted CAR T cells are reinfused into the patient, where the CAR allows T cells to specifically recognize and destroy cancer cells.1,3 All approved CAR T cell therapies and most of the therapies used in clinical trials are based on viral transduction resulting in permanent CAR expression.2,3 Although this can lead to long-term remissions,4,5 it is associated with safety concerns. CAR T cells can interact with the patient’s immune system holding the risk for side effects such as cytokine release syndrome, neurotoxicity, and on-target off-tumor toxicity.6 For instance, persistent CD19-directed CAR T cells often eliminate CD19-expressing healthy B cells leading to hypogammaglobulinemia,7 which is linked to an increased risk of infections.8 In addition, the use of viral vectors is accompanied by several disadvantages such as limited cargo capacity, time- and cost-intensive manufacturing with potential emergence of replication-competent virus, the risks for oncogenic transformation of engineered T cells due to genomic integration and for immune responses against vector-derived epitopes expressed on ex vivo engineered CAR T cells.9,10 Hence, alternative, especially non-viral gene transfer methods are intensively under investigation to improve CAR T cell manufacturing as well as safety.9

One possibility to avoid viral vectors in CAR T cell therapy is to utilize mRNA. Transfer of CAR-encoding mRNA offers a non-integrating and transient T cell modification providing an improved safety profile and controllability of CAR T cell therapy.11,12,13,14 mRNA-based CAR T cells have already been evaluated in numerous preclinical studies reporting promising anti-tumor responses (reviewed in Soundara Rajan et al.12), but only showed a poor performance in most clinical trials to treat hematological cancers as well as solid tumors.14,15,16,17,18 In all clinical studies, CAR-mRNA delivery into T cells was achieved by electroporation (EP).13,14,15,16,17,18 This method is based on applying an electric field on the cells resulting in short-term membrane disruption to allow mRNA entry.19 However, irreparable membrane damage and the loss of cellular content pose the risk for low cell viability as well as altered gene and protein expression,20 which may explain the malperformance of mRNA-based CAR T cells in clinical studies. To overcome these challenges of electrically induced cell manipulation, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) in which the mRNA is encapsulated into a fully synthetic lipid shell can alternatively be used for mRNA-based CAR T cell engineering with lower cytotoxicity to potentially offer improved mRNA-based CAR T cells. Another great benefit of LNPs over EP is their potential for systemic in vivo application to produce CAR T cells directly inside the patients offering an off-the-shelf product with reduced manufacturing time and costs.21,22,23,24

In this study, mRNA-loaded LNPs were formulated using the ionizable lipid mix (GenVoy-ILMTM) for T cells from Precision NanoSystems (Vancouver, BC, Canada) and the NanoAssemblr® SparkTM device to produce mRNA-based CAR T cells ex vivo. A head-to-head comparison with EP-derived CAR T cells shows that these LNPs outperform EP regarding CAR-mRNA and CAR T cell persistence as well as duration of CAR T cell efficacy in vitro. The mRNA-LNP-derived CAR T cells were furthermore compared with stably expressing CAR T cells produced by lentiviral transduction achieving comparable in vitro functionality. This study highlights LNPs as the next-generation mRNA ex vivo delivery platform for mRNA-based CAR T cell engineering and paves the way for preclinical evaluation in mouse studies and translation into the clinics.

Results

Features of CAR-encoding mRNA

An mRNA encoding for a CD123-directed CAR with CD28-derived hinge, transmembrane and co-stimulatory domain, and CD3z-signaling domain was prepared by in vitro transcription (IVT) from a linear DNA template generated by PCR followed by subsequent polyadenylation (Figure 1A). Besides the poly(A) tail, the mRNA contained a CleanCap® cap structure at the 5′ end and a full N1-methylpseudouridine (m1Ψ) modification. The mRNA was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, which revealed the presence of the full-length product as well as a distinguishable extension of polyadenylated mRNA compared with non-polyadenylated RNA (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Production of CAR-encoding mRNA

(A) Workflow of the mRNA production process. Starting from the linear DNA template containing the T7 promoter sequence and the CAR-open reading frame (CAR-ORF) generated by PCR, mRNA with a CleanCap® cap structure, N1-methylpseudouridine (m1Ψ) modification, and a poly(A) tail (pA) was produced by in vitro transcription (IVT) and subsequent polyadenylation (PolyA). Image was created with BioRender.com. (B) Representative agarose gel image of non-polyadenylated CAR-RNA (-pA) and polyadenylated CAR-mRNA (+pA). L, RNA ladder (RiboRuler High Range RNA Ladder, ThermoFisher Scientific).

Performance of mRNA delivery using LNPs compared with EP

LNPs provide a promising alternative to EP, which is still the state-of-the-art method for mRNA-based CAR T cell engineering in clinical trials. In this study, the Neon Transfection System (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used for EP allowing the manual change of various parameters including pulse voltage, width, and number for a greater transparency. In order to apply the optimal settings, different resuspension buffers and voltages were tested and analyzed regarding their impact on cell viability and transgene expression (Figure S1). Based on these optimization results, here, T cells were resuspended in buffer R (part of the kit) and electroporated at 1,600 V, 10 ms, three pulses since this setting led to the maximum cell viability and a high transgene expression level (Figure S1). Similar results were achieved when using a different EP device, the 4D-Nucleofector from Lonza (Walkersville, MD, USA), indicating comparability between different EP devices and using most optimized EP conditions for the comparison with LNPs (Figure S2). To compare EP with LNP-based transfection of T cells, CAR-mRNA was encapsulated into LNPs. The commercial GenVoy-ILMTM T cell kit for mRNA is optimized for T cell transfection regarding the choices of ionizable lipid, structural lipid, helper lipid, sterol, and surfactant including their ratios to each other (proprietary to Precision NanoSystems, US 20220162552 A1) and was used in this study. The T cell kit was selected as it was more effective in mRNA-based CAR T cell engineering than lipid compositions of two clinically approved LNPs with only slight impact on cell viability (Figures S3A–C). The mRNA delivery with the T cell kit was shown to be completely dependent on apolipoprotein E4 (ApoE4) since CAR expression was only observed when ApoE4 was supplemented to T cells with LNPs (Figure S3D), implying the delivery mechanism via the ApoE-low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDL-R) pathway. With the T cell kit, encapsulation efficiencies of 96.8% ± 0.6% (mean ± SEM, n = 5) were achieved. CAR-mRNA-LNPs showed a diameter of 78.3 nm ± 2.3 nm (mean ± SEM, n = 5) and a polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.201 ± 0.006 (mean ± SEM, n = 5). LNPs with mRNA encoding for a non-functional Mock-CAR-construct (Figures S4A/B) were formulated as mRNA-control showing encapsulation efficiencies of 97.0% ± 0.5% (mean ± SEM, n = 4), a diameter of 82.0 nm ± 4.0 nm (mean ± SEM, n = 4), and a PDI of 0.191 ± 0.020 (mean ± SEM, n = 4) (Figures S4C–E). Six micrograms CAR-mRNA per 106 T cells were identified as the optimal dose for LNP-based transfection with regard to a high CAR expression and maintenance of cell viability (Figure S4F).

After CAR-mRNA transfection of T cells via EP or LNPs, CAR expression on the cell surface was monitored by incubating the cells with an anti-F(ab’)2–Alexa Fluor 647 reagent. The CAR was expressed with high intensity on 92% of EP-derived T cells already after 6 h (day 0.25) post-transfection, indicating a rapid and highly efficient mRNA transfer (Figures 2A/B). At this time point, maximum CAR expression was reached because the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of Alexa Fluor 647, which serves as an indicator of the intensity of CAR expression, was already reduced on day 1 after EP (Figure 2A). From that day, the proportion of CAR-expressing cells decreased rapidly until it fell below 10% on day 3 post-EP. For LNP-mediated mRNA delivery, the maximum CAR expression intensity was lower than that achieved by EP (CAR MFI: 9,716 ± 1,334 EP [day 0.25] vs. 2,039 ± 263 LNP [day 1]; mean ± SEM, n = 4), implying that mRNA-LNPs led to fewer CAR molecules per T cell. However, a comparable peak of 84% CAR-expressing cells was detected for LNP-transfected cells obtained on day 1 instead of day 0.25 post-transfection, indicating a slower mRNA availability with LNPs than with EP. At the 0.25-day time point, the CAR surface expression of LNP-treated cells was relatively low with about 50%, although a higher CAR-mRNA level was detected within the T cells for LNP delivery as for EP after total RNA extraction and qPCR analysis (Figure S5). This might have several reasons: (1) some of the transferred mRNA was still encapsulated within LNPs and therefore not available for translation into CAR protein, (2) higher amounts of mRNA were delivered by EP but mRNA-degradation occurred due to rapid translation after EP. On days 2, 3, and 4 post-transfection, CAR expression was significantly higher on LNP- than on EP-derived CAR T cells. The percentage of CAR-expressing cells fell below 10% on day 6, thus CAR expression could be prolonged by up to about 3 days when transfecting with LNPs instead of EP, which means about twice as long as a period of time that can be reached with conventional mRNA technology (Figure 2B). These results can be explained by a longer CAR-mRNA persistence in LNP-transfected T cells compared with electroporated T cells (Figure 2C). Extended transgene expression by up to about 4 days and prolonged mRNA persistence after LNP-treatment could be confirmed in T cells transfected with Mock-CAR-mRNA (Figures S6A/B).

Figure 2.

Comparison of electroporation (EP) and lipid nanoparticle (LNP)-based mRNA delivery into primary T cells for the generation of CD123-directed CAR T cells

Human T cells were isolated, activated, and 7 days later transfected with 6 μg CAR-encoding mRNA per 106 cells either by EP (blue) or by LNPs (red). (A) Representative histograms of flow cytometric CAR expression analysis from day 0.25 (6 h) to day 6 after transfection of T cells compared with untransfected (UTF, gray) T cells. Anti-F(ab’)2–Alexa Fluor 647 reagent was used for CAR detection (F(ab’)2+) and 7-AAD staining of the cells was performed to exclude dead cells (7-AAD+) from the analysis. Colored values indicate the median fluorescent intensity of Alexa Fluor 647 as an indicator for CAR expression intensity. (B) Proportion of CAR-expressing cells indicated by F(ab’)2+ cells starting from 0.25 to 6 days post-transfection compared with untransfected (UTF, black) T cells (mean ± SEM of n = 4 independent experiments/donors). (C) Relative CAR-mRNA level from 0.25 to 4 days post-transfection normalized to the respective level on day 0.25 post-transfection (mean ± SEM of n = 3 independent experiments/donors). (D) Functionality of mRNA-based CAR T cells indicated by cytotoxicity against CD123-expressing KG-1 cells in a co-culture (T cells:KG-1 ratio = 1:1 for 24 h) starting from 0.25 to 6 days post-transfection compared with untransfected (UTF, black) T cells (mean ± SEM of n = 4 independent experiments/donors). ns, not significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA (repeated measures) with Holm-Sidak multiple comparison test.

Besides CAR expression and mRNA persistence, CAR T cell functionality was analyzed in vitro for 6 days post-transfection. Consistent to CAR expression, CAR T cell efficacy was elongated after LNP-based transfection by up to 3 days indicated by a later peak as well as a slower decrease of cytotoxicity against the CD123-expressing cell line KG-1 compared with EP-transfected CAR T cells (Figure 2D). More precisely, the maximum cytotoxicity of 83% for EP-derived CAR T cells was reached after 0.25 day, while 76% cytotoxicity of LNP-transfected CAR T cells was reached after 1 day. At this time point, LNP-CAR T cells were already significantly more effective than EP-CAR T cells. The anti-cancer efficacy dropped below 10% on day 3 for EP-derived compared with day 6 post-transfection for LNP-derived CAR T cells, which is in accordance with the CAR expression levels on the surface.

Effect of EP- and LNP-based CAR-mRNA delivery on T cell phenotype, viability, and off-target toxicity

After EP and LNP-treatment, the resulting mRNA-based CAR T cells were characterized in more detail. Since EP was shown to alter gene and protein expression,20 T cells that were transfected with CAR-mRNA and Mock-CAR-mRNA were analyzed regarding selected surface markers to indicate T cell subtypes (CD3, CD4, CD8), activation (CD25), and exhaustion (Lymphocyte Activation Gene-3 [LAG-3]) in comparison to untransfected T cells (Figure 3A). CD3 expression as well as the proportion of CD4−CD8+ cells representing cytotoxic T cells were not affected on either EP- and LNP-CAR T cells or on EP- and LNP-Mock-CAR T cells (Figure 3A). The CD4+CD8− population representing helper T cells showed a slight but not significant reduction in CAR T cells, while the CD4+CD8+ double-positive population was significantly increased in both, EP- and LNP-CAR T cells, respectively. These data indicate a shift from the CD4+CD8− helper T cell phenotype to a CD4+CD8+ double-positive phenotype on CAR T cells. CD4+CD8+ T cells are associated with an activated phenotype25 (Figure S7), also confirmed by a significantly increased CD25 expression on CAR T cells (Figure 3A). Furthermore, a significantly higher expression of LAG-3 was observed on EP- and LNP-CAR T cells compared with untransfected T cells, whereby LAG-3 expression was slightly higher on EP-derived CAR T cells than on LNP-transfected CAR T cells, indicating a marginally increased exhaustion (Figure 3A). As CD4, CD8, CD25, and LAG-3 expression remained unchanged on Mock-CAR T cells, no effect of EP or LNPs on either T cell subtypes or on activation or on T cell exhaustion was indicated. Thus, the activated phenotype observed on CAR T cells only could be explained by the presence of a functional CAR, proving tonic signaling of the CAR construct.

Figure 3.

Characterization of mRNA-based CAR T cells

Human T cells were transfected with CAR-mRNA or Mock-CAR-mRNA by EP (blue) or LNPs (red). Untransfected T cells (UTF, black) were analyzed as negative control. (A) Proportion of CD3, CD4, CD8, CD25, and LAG-3-expressing cells on day 1 after transfection for T cell identification (CD3+), analysis of T cell subtypes (CD4+CD8−, CD4−CD8+, CD4+CD8+), activation (CD25+) and exhaustion (LAG-3+). Statistical analysis of each group was performed in comparison to UTF cells. (B) Representative dot plots of flow cytometric analysis of single cells 1 day after transfection. Cells were stained with Annexin V and 7-AAD to indicate viable cells (Annexin V−7-AAD−, thick black frame), apoptotic cells (Annexin V+7-AAD−), and dead cells (Annexin V+7-AAD+). Values present the proportion of these populations within the single cell gate. (C) Viability of T cells indicated by the proportion of Annexin V−7-AAD− cells on days 0.25, 1, and 2 post-transfection. (D) Off-target cytotoxicity of mRNA-based CAR T cells indicated by cytotoxicity against CD123-negative K-562 cells in a co-culture (T cells:K-562 ratio = 1:1 for 24 h) starting from 0.25 to 3 days post-transfection. Bars represent mean ± SEM of n = 4 independent experiments/donors. ns, not significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA (matched values) (A) or two-way ANOVA (repeated measures) (C, D), each with Holm-Sidak multiple comparison test.

To investigate the toxic impact on T cells, transfected cells were stained with Annexin V and 7-AAD to reveal apoptotic (Annexin V+7-AAD−) and dead cells (Annexin V+7-AAD+). On 1 day after transfection, when the CAR expression was comparable between EP- and LNP-derived CAR T cells (Figure 2B), EP led to increased apoptosis and cell death compared to LNP-treatment (29% CAR EP vs. 16% CAR LNP, upper right quadrant, Figure 3B). Thus, viability could be determined by the analysis of the Annexin V−7-AAD− double-negative population. In a time course experiment, EP-CAR T cells showed a significantly lower viability than LNP-CAR T cells on day 0.25 (40% EP vs. 65% LNP) and on day 1 (46% EP vs. 72% LNP) after transfection (Figure 3C). However, on day 2, EP-CAR T cells recovered leading to a comparable viability to LNP-CAR T cells (69% EP vs. 68% LNP). A significantly lower viability on day 0.25 after transfection was also observed on EP-Mock-CAR T cells compared with LNP-Mock-CAR T cells (55% EP vs. 77% LNP), indicating that EP is a more harmful transfection method compared with LNPs. Independently of the delivery method, Mock-CAR T cells were more viable than the respective CAR T cells on days 0.25 and 1 (Figure 3C), implying a negative effect of tonic signaling by the intracellular stimulatory domains of the CAR (CD28, CD3ζ) on T cell viability, which are not present in the Mock-CAR construct.

As tonic signaling can lead to unspecific toxicity, CAR T cells were tested against CD123-negative K-562 cell line to determine off-target effects. Significantly higher toxicities compared with untransfected T cells were observed on days 0.25 and 1 post-EP as well as on days 0.25, 1, and 2 post-LNP-treatment, respectively (Figure 3D), which correlates with the respective CAR expression intensity. However, on day 1, when CAR expression between EP- and LNP-CAR T cells was comparable, EP-CAR T cells were significantly more toxic toward K-562 cells than LNP-CAR T cells, implying an improved safety profile of LNP-derived CAR T cells at that time point. On day 3 post-transfection, off-target toxicity of both, EP- and LNP-CAR T cells dropped to the level of untransfected T cells, demonstrating transient effects of mRNA-based CAR T cells toward non-target cells.

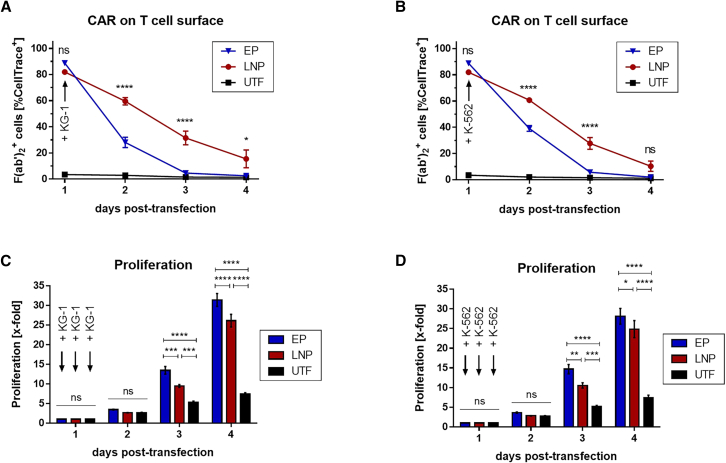

Characterization of EP- and LNP-based mRNA-CAR T cells in the presence of target and non-target cells

As antigen-induced proliferation can occur after CAR T cells encounter target cells, which would impact CAR expression kinetics of mRNA-based CAR T cells, EP- and LNP-derived mRNA-CAR T cells were plated in a challenge assay together with KG-1 or, as a control, with K-562 cells to investigate CAR expression and CAR T cell proliferation after contact with target and non-target cells, respectively. Starting with a comparable CAR expression at the onset of co-culture on day 1 post-transfection, CAR expression was significantly higher on LNP-derived CAR T cells for the following 3 days with KG-1 cells (Figure 4A) and for 2 days with K-562 cells (Figure 4B) compared with EP-CAR T cells, confirming prolonged CAR expression by LNP-based transfection. Both, EP- and LNP-CAR T cells showed an increased proliferation rate not only after addition of KG-1 cells (Figure 4C) but also of K-562 cells (Figure 4D) compared with untransfected cells, indicating antigen-independent proliferation of CAR T cells, most probably induced by CAR-mediated T cell activation. However, LNP-CAR T cells proliferated less compared with EP-CAR T cells from day 3 post-transfection, explaining the prolonged CAR expression especially during the later time points.

Figure 4.

Comparison of electroporation (EP) and lipid nanoparticle (LNP)-derived mRNA-CAR T cells after encountering target and non-target cells

Human T cells were isolated, activated, and 7 days later transfected with 6 μg CAR-encoding mRNA per 106 cells either by EP (blue) or by LNPs (red). Untransfected T cells (UTF, black) were analyzed as negative control. Twenty-four hours after transfection, CAR T cells were 1:1 plated with target (KG-1) or non-target (K-562) cells and analyzed regarding (A, B) CAR expression indicated by F(ab’)2+ cells within the CellTrace+ cell fraction and (C, D) proliferation (mean ± SEM of n = 4 independent experiments/donors). ns, not significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA (repeated measures) with Holm-Sidak multiple comparison test.

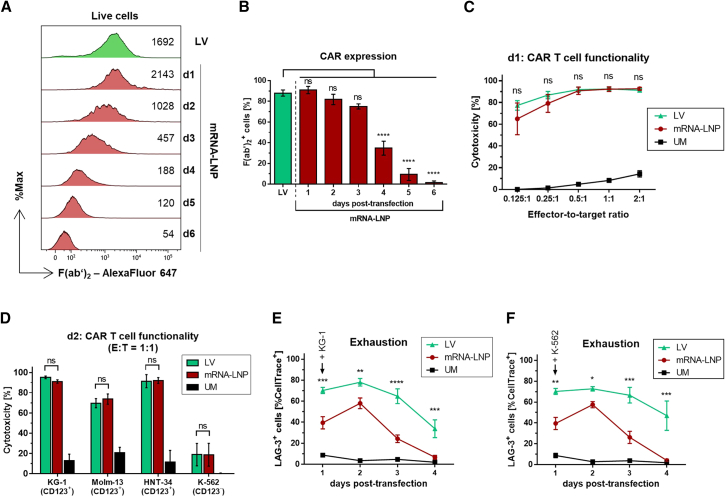

Comparison of mRNA- and lentivirus-based CAR T cells

Since stably expressed CAR T cells are still the gold standard used in the clinics, mRNA-based CAR T cells were compared with CAR T cells that were produced by lentiviral (LV) transduction. For comparison of transient vs. stable CAR T cells, the LNP-derived CAR T cells were chosen, since CAR-mRNA and protein persistence as well as CAR T functionality were prolonged compared with EP-derived CAR T cells.

On day 1 after mRNA-LNP-addition, CAR expression intensity on mRNA-CAR T cells was slightly higher than on LV-CAR T cells (Figure 5A), but dropped below the level of LV-CAR T cells from day 2 post-transfection on. However, the proportion of CAR-positive cells was comparable between mRNA- and LV-CAR T cells for up to 3 days post-mRNA-transfection (Figure 5B). After day 3, the percentage of CAR-positive cells was significantly lower for mRNA-based CAR T cells highlighting the transient nature of these cells. On days 1 and 2 post-transfection, mRNA-CAR T cells were compared with LV-CAR T cells regarding cytotoxicity toward KG-1 cells in different E:T ratios, toward different CD123+ target cells as well as K-562 as non-target cells showing non-significant differences in the performance of mRNA- and LV-CAR T cells (Figures 5C and 5D). Interestingly, LV-CAR T cells were more exhausted than mRNA-CAR T cells after challenging these cells with KG-1 target cells as well as with K-562 non-target cells as indicated by significantly higher LAG-3 surface expression on virally transduced CAR T cells compared with mRNA-LNP-treated cells (Figures 5E and 5F).

Figure 5.

Comparison of stably transduced CAR T cells with mRNA-based CAR T cells

Human T cells were modified either by lentiviral transduction (LV, green) or by lipid nanoparticle (LNP)-based transfection with CAR-mRNA (mRNA-LNP, red) to stably or transiently express the CAR, respectively. (A) Representative histograms of flow cytometric CAR expression analysis of LV-CAR T cells 6 days after transduction and from day 1 to day 6 after LNP-mediated transfection, respectively. Values show the MFI of anti-F(ab’)2–Alexa Fluor 647 as an indicator for CAR expression intensity. (B) Proportion of CAR-expressing cells indicated by F(ab’)2+ cells of LV-based CAR T cells 6 days post-transduction and of mRNA-LNP-based CAR T cells starting from 1 to 6 days post-transfection. (C) Functionality of CAR T cells generated by LV or LNP-transfection indicated by cytotoxicity against CD123+ KG-1 cells in a co-culture using effector-to-target ratios of 0.125:1, 0.25:1, 0.5:1, 1:1, and 2:1 for 24 h. LV-CAR T cells were used on day 6 post-transduction, mRNA-LNP-CAR T cells on day 1 post-transfection, and unmodified (UM, black) on day 8 post-isolation. (D) Cytotoxicity against CD123+ KG-1 cells, CD123+ MOLM-13 cells, CD123+ HNT-34 cells, and CD123− K-562 cells, each tested in a 1:1 effector-to-target (E:T) ratio. CAR T cells were used on day 7 post-transduction, mRNA-LNP-CAR T cells on day 2 post-transfection, and unmodified (UM, black) on day 9 post-isolation. (E and F) CAR T cell exhaustion in the presence of (E) KG-1 and (F) K-562 cells indicated by LAG-3+ cells starting from 1 to 4 days post-transfection (mRNA-LNP), from 6 to 9 days post-transduction (LV), or from 8 to 11 days post-isolation (UM), respectively. Mean ± SEM of n = 3 (C, D) or n = 4 (B, E, F) independent experiments/donors are shown. ns, not significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA (B) or two-way ANOVA (matched values) (C, D) or two-way ANOVA (repeated measures) (E, F), each with Holm-Sidak multiple comparison test.

Discussion

CAR T cell therapy has shown great success in treating selected hematological malignancies.4,5 However, current CAR T cell engineering relies on ex vivo modification of T cells by means of genome-integrating viral vectors, which is associated with safety concerns and high manufacturing time and costs.6,7 The transfer of CAR-encoding mRNA into T cells presents a safe alternative to viral vectors as it provides a non-integrating, transient T cell modification.11,12 In clinical trials, CAR-mRNA delivery into T cells was achieved by EP but such CAR T cells mostly showed poor anti-tumor responses.14,15,16,17,18 Therefore, our study compared LNP-based mRNA delivery with EP to potentially offer improved mRNA-based CAR T cells. In this context, IVT was performed to produce CD123-directed CAR-encoding mRNA containing m1Ψ, since this uridine modification was shown to enhance protein expression and reduce immunogenicity of IVT mRNA in vitro and in vivo.26,27,28

LNPs generated mRNA-based CAR T cells with comparable CAR expression to EP after 24 h. These observations are in agreement with results reported in previous studies.29,30 However, here, we demonstrate in a head-to-head comparison that LNP-derived CAR T cells provide prolonged functionality in vitro by up to about 3 days which is due to the extended CAR-mRNA persistence in the cells and CAR expression on the cell surface, presenting an improvement over EP-derived CAR T cells. These results are consistent with reports of a former study, in which luciferase activity was extended in Jurkat T cell line after LNP-based transfection of luciferase-encoding IVT mRNA compared with EP.31 For LNP-derived CAR T cells similar CAR expression patterns of up to about 7 days were observed using anti-FAP-CAR-mRNA,22 indicating that our results are in line with other works using conventional mRNA technology for LNP-derived CAR T cells. In case of ErbB2- and CEA-directed CAR T cell engineering, CARs could be detected on non-activated T cells for 6 days after EP,32 thus showing longer CAR expression than observed in the present study. This is due to non-activation of the T cells, which do not proliferate as a result, thus maintaining CAR expression on the cell surface. However, non-activation of T cells is not a clinically relevant setting in which high T cell numbers are required for appropriate doses of transient CAR T cells.33 Another study reported ambiguous results with different tumor vessel-targeting CAR constructs.34 There, 3 days after mRNA-EP, a CAR containing the CD28-derived transmembrane domain (TMD) was not expressed anymore, which is consistent with the present results, but another CAR construct with the CD8α-derived TMD was still expressed on a high level explained by different stabilities of the CARs in the cell membrane.34 Besides the CAR construct and its stability, several other factors can affect transgene expression after EP with mRNA, such as the design and amount of mRNA, cell number, strength of the electric field, and activation status of the T cells,35,36 of which most of them may also be applicable for LNP-based transfection. Furthermore, in case of LNPs, transgene expression depends on the chemical composition of LNPs, which influences the cellular uptake of LNPs and the endosomal escape of mRNA.37 Thus, comparison of the present results with the literature is difficult. However, here, the head-to-head comparison of EP and LNP-based mRNA transfer is provided by using the same CAR construct, mRNA design, mRNA amount, cell count, timing of transfection, and T cell expansion condition showing a prolonged CAR expression in T cells and CAR T cell functionality when transfected with CAR-mRNA-LNPs.

The extended mRNA and CAR T cell persistence of LNP-treated compared with EP-derived T cells observed in this study can mainly be explained by the delivery mechanisms. EP is based on electrically induced membrane disruption.19 In contrast, for LNP-based transfer, mRNA-LNPs used here mimic low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) due to the adsorption to supplemented ApoE4, which is taken up by LDL-receptor-mediated endocytosis. This delivery mechanism via the ApoE-LDL-receptor pathway has already been described for LNP-mediated RNA-delivery.38,39,40,41 Due to pH value reduction in the endosome, the ionizable lipids within the LNPs receive a positive charge leading to disintegration of the mRNA-LNPs, followed by electrostatic interactions of the positively charged ionizable lipids with negatively charged lipid components of the endosomal bilayer. This leads to lipid bilayer disruptions by the formation of inverse phases and finally to a release of mRNA into the cytoplasm.38 We and others29,30 found that this kind of intracellular mRNA delivery is less harmful to T cells. While mRNA encapsulation into LNPs provides protection against extra- and intracellular nucleases and promotes cellular uptake and endosomal escape,38 for EP, transferred mRNA is naked, making it vulnerable for enzymatic degradation. Furthermore, mRNA directly enters the cells during EP where it can immediately be translated into protein. In contrast, for LNP-mediated delivery, mRNA is gradually available in the cytosol, which represents the most probable reason why here, a lower number of CAR molecules per T cell were observed on LNP- compared to EP-CAR T cells. However, according to Gomes-Silva et al.,42 a high CAR expression is not always preferable as it can induce excessive target-independent T cell activation, also referred to as tonic signaling, as it is associated with increased T cell apoptosis, impaired anti-tumor activity, and exhaustion.42,43 Indeed, we also found that EP-CAR T cells are less viable, less efficient against target cells, tend to be more exhausted, and, moreover, cause enhanced off-target toxicity than LNP-CAR T cells 1 day after transfection, presenting many arguments for the use of LNPs instead of EP for mRNA-based CAR T cell engineering. Besides the shift in intracellular mRNA availability, another reason for the extended mRNA persistence and CAR expression on LNP-CAR T cells is the lower proliferation rate of these cells, resulting in slower dilution of mRNA and CAR protein during each cell division. While a reduced proliferation is detrimental for stably transduced CAR T cells regarding anti-tumor efficacy,44,45,46,47 we show that for mRNA-based CAR T cells, slower CAR T cell proliferation is associated with elongated CAR expression correlating with prolonged CAR T cell functionality provided by LNP-based modification. Thus, reduction of CAR T cell proliferation upon mRNA transfer could present a promising approach to further extend CAR expression and efficacy of mRNA-based CAR T cells.

Compared with stably transduced ex vivo modified CAR T cells, mRNA-LNP-based CAR T cells showed comparable numbers of CAR-expressing cells for 3 days post-modification and similar CAR T cell functionality for 2 days, which is in agreement with former studies.29,30 These results emphasize the ability of LNPs to generate mRNA-based CAR T cells that keep pace with clinical standards when the CAR expression levels are comparable. We demonstrate that CAR T cells are less exhausted after mRNA-LNP-based modification compared with lentiviral transduction, most probably due to the transient CAR expression accompanied by short-term CAR-mediated T cell activation. Moreover, LNP-derived CAR T cells were also less exhausted than EP-derived CAR T cells, indicating a less stressful transfection method when using LNPs. Reduced exhaustion poses a benefit for CAR T cell therapy as it directly correlates with anti-tumor responses,43,44 making LNP-derived CAR T cells the most promising candidate for transient CAR T cell therapy treatment in the clinics.

In summary, LNP-based transfection generates improved mRNA-based CAR T cells as it significantly prolongs CAR T cell efficacy in vitro as a result of extended CAR-mRNA and CAR T cell persistence. This is attributed to a different mRNA delivery mechanism with less cytotoxicity as well as slower CAR T cell proliferation following LNP-treatment. In a next step, these mRNA-LNP-derived CAR T cells will be tested in in vivo studies to pave the way for GMP process development of ex vivo generated mRNA-CAR T cells for translation into the clinic. Besides their biological benefits, mRNA-LNPs have proven cost- and time-effective manufacturability and scalability, providing a clear path to the clinic.48 Additionally, the mRNA-LNPs used in this study can be utilized as a flexible platform for the generation and screening of different CAR T cells by changing the mRNA sequence without necessary changes of the manufacturing process and LNP composition.

Materials and methods

Isolation and in vitro culture of primary human T cells

T cells were isolated from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained by density gradient centrifugation of blood from healthy donors (collected by the Institute for Transfusion Medicine of the University Clinic of Leipzig, Germany and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University Clinic of Leipzig, Germany, as no ethical or scientific concerns were raised [file reference number: 272-12-13082012]). Purification of T cells from PBMCs was performed by magnetic-activated cell sorting using the Pan T cell Isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. T cells were then frozen in 90% fetal bovine serum (FBS) supplemented with 10% DMSO in liquid nitrogen until further use. After thawing, T cells were activated by the addition of 25 μL/mL ImmunoCult Human CD3/CD28/CD2 T cell Activator (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) and expanded for 7 days in ImmunoCult-XF T cell expansion medium (STEMCELL Technologies) with 100 ng/mL human recombinant interleukin-2 (IL-2; PeproTech, London, UK) at 37°C and 5% CO2.

mRNA synthesis

Originating from a lentiviral vector carrying the anti-CD123-CAR-encoding sequence (Creative Biolabs, Shirley, NY, USA), the DNA template for mRNA synthesis was produced by PCR. mRNA was then generated via in vitro transcription (IVT) with co-transcriptional 5′ capping and subsequent polyadenylation specified in detail as follows.

PCR

For the generation of the DNA template with T7 promotor for IVT, PCR using Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs, Frankfurt, Germany) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. T7 promotor sequence was added through the forward primer 5′-GCTAATACGACTCACTATAAGGAGAGGCCGCCACCATGGCCTTAC-3′ (T7 promotor sequence underlined, slightly modified (bold) for the integration of CleanCap® AG as a 5′ cap structure). 5′-CACTACCGAGGCGGCAGGGCCTGCAT-3′ was used as reverse primer. PCR reactions were incubated for 30 s at 98°C followed by 35 cycles of 10 s at 98°C and 90 s at 72°C, followed by 2 min at 72°C. PCR samples were purified via the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up Mini kit (MACHEREY-NAGEL, Düren, Germany). The concentration of the PCR product was determined using UV/Vis-spectroscopy (NanoDrop 3000, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and integrity was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

IVT

Capped mRNA was synthesized using HighYield T7 RNA Synthesis kit (Jena Bioscience, Jena, Germany) with 1× HighYield T7 Reaction Buffer, 10 mM DTT, 5 mM ATP, 5 mM CTP, 5 mM GTP and 5 mM N1-methylpseudo-UTP (Jena Bioscience), 1 μg template DNA, and 5 mM CleanCap® Reagent AG (3′ OMe) (TriLink Biotechnologies, San Diego, CA, USA). Reactions were incubated for 4 h at 37°C followed by treatment with 100 U/mL TURBOTM DNase (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 15 min at 37°C to eliminate the DNA template. The mRNA was purified using the NucleoSpin RNA Clean-up Mini kit (MACHEREY-NAGEL) followed by concentration determination at NanoDrop 3000 and analysis in agarose gel electrophoresis supplemented with 0.3% H2O2 (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany).

Polyadenylation

For the addition of a 3′ poly(A) tail to the capped mRNA, E. coli Poly(A) Polymerase (New England Biolabs) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reactions were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. mRNA was purified and analyzed as performed after IVT.

mRNA-LNP formulation and characterization

mRNA was encapsulated into LNP using the GenVoy-ILMTM T cell kit for mRNA (Precision NanoSystems). Therefore, 11.02 μg of the mRNA was diluted in 10× formulation buffer provided with the kit and RNase-free water in a total volume of 35.2 μL (mRNA dilution). Forty-eight microliters of dilution buffer, 32 μL mRNA dilution, and 16 μL lipid mix were microfluidically mixed using setting #3 of the NanoAssemblr® SparkTM device (Precision NanoSystems). The formulated mRNA-LNPs were 1:2 diluted in dilution buffer and stored at 4°C. For characterization, the diameter (z-average) and PDI of the generated mRNA-LNPs were determined via dynamic light scattering on a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK) using the following parameters: measurement type: size; material: protein; dispersant: PBS; temperature: 25°C; equilibration time: 20 s; cell type: ZEN0040; measurement angle: 173° backscatter; number of runs: 12; run duration: 10 s; number of measurements: three with no delay. For determination of the mRNA concentration and mRNA encapsulation efficacy, the Quant-iT RiboGreen Assay (ThermoFisher Scientific) was performed in 96-well plates according to a modified protocol from Precision NanoSystems. Therefore, the mRNA-LNPs were incubated in 1x TE buffer for 10 min at 37°C in the absence or presence of 0.6% Triton X-100 to determine free and total mRNA, respectively. Ribosomal RNA in different concentrations was used to obtain a standard curve. After incubation, 100 μL of the QuantiT RiboGreen RNA Reagent, diluted 1:100 in 1× TE buffer, were added and the fluorescence was measured at λem = 528 nm with λex = 485 nm at Tecan Infinite M200 microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). The fluorescence intensity directly correlated to the amount of RNA. The standard curve was used for quantification of RNA concentration as well as the calculation of encapsulation efficiency.

mRNA delivery via LNP-based transfection

For transfection with mRNA-LNPs, isolated and expanded T cells were counted and plated at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/mL in T cell expansion medium with interleukin (IL)-2; 1 μg/mL ApoE4 (PeproTech, provided by the GenVoy-ILMTM T cell kit for mRNA from Precision NanoSystems) and 3 μg/mL mRNA-LNPs (=6 μg/106 T cells) were added. Cells were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 until further analyses.

mRNA delivery via EP

T cells were transfected by EP using the Neon Transfection System 100 μL-kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Therefore, T cells were washed once in PBS and subsequently resuspended in buffer R to obtain a cell concentration of 2 × 107 cells/mL; 4 × 106 cells were mixed with 24 μg of mRNA and electroporated at 1600 V, 10 ms, three pulses (twice in 100 μL electroporation tip). The electroporated cells were transferred in prewarmed T cell expansion medium with IL-2 and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 until further analyses were performed.

Lentiviral vector production and transduction

For lentiviral vector production, 4 × 106 HEK-293T cells were plated in 15 cm tissue culture dishes for 24 h and then transfected with 9 μg of pMD2.G, 6.25 μg of pRSV-Rev, 12.5 μg of pMDLg/pRRE packaging plasmids (Addgene, Watertown, USA), as well as with 32 μg of the transfer plasmid (Creative Biolabs) using 120 μL Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific). The medium was replaced 15 h later. Further 48 h later, the viral supernatant was collected and concentrated by centrifugation using Amicon filters (100 kDa; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Virus titer was determined by transduction of HEK-293T cells with different volumes of the concentrated supernatant and flow cytometric analysis of the cells expressing the reporter protein GFP. Twenty-four hours after T cell isolation and activation, the lentiviral vector was added to the cells at a concentration of 1 viral particle per 1 T cell (multiplicity of infection [MOI] 1) followed by centrifugation at 1,800 rpm for 90 min at 32°C and overnight incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2. This step was repeated the next day. Transduced T cells were expanded in T cell expansion medium with IL-2.

Flow cytometry

CAR expression, viability, and surface markers of the transfected T cells were flow cytometrically analyzed on BD FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences, Mississauga, Canada) using AlexaFluor 647-conjugated AffiniPure F(ab’)₂ Anti-Mouse IgG, F(ab’)₂ fragment specific with minimal cross-reactions to human, bovine, and horse serum proteins (referred to as anti-F(ab’)2–Alexa Fluor 647 reagent; Jackson ImmunoResearch, Ely, UK), 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD; BD Biosciences), FITC Annexin V (BD Biosciences), PE-Cy5 CD3 (clone: UCHT-1, BD Biosciences), BV510 CD4 (clone: SK3, BD Biosciences), PE-Cy7 CD8 (clone: RPA-T8, BD Biosciences), PE CD25 (clone: 2A3, BD Biosciences), BV421 LAG-3 (clone: T47-530, BD Biosciences), and PE-Cy7 LAG-3 (clone: 3DS223H, Invitrogen by ThermoFisher Scientific). The data were evaluated in Kaluza Analysis software (version 2.1; Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany).

mRNA quantification inside the cells

At each analysis time point, cells were harvested and washed in PBS. Cell pellets were resuspended in TRI Reagent (Zymo Research, Freiburg, Germany) and frozen at −80°C until RNA isolation was performed. Therefore, the harvested cells were thawed and RNA was isolated using the Direct-zol RNA Microprep kit (Zymo Research). Concentration of the isolated RNA was determined using Nanodrop. Reverse transcription of 100 ng isolated RNA was performed using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit with Oligo d(T)18 primer (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to manufacturer’s recommendation. cDNA was diluted 1:1,000 in H2O for quantitative PCR. Therefore, PerfeCTa SYBR Green FastMix Reagent (Quantabio, Beverly, MA, USA) was mixed with the cDNA and the CAR-specific primer pair (forward 5′-ATGTGCAGATCACCCAGTCC-3′, reverse 5′-TTGTTGGTCTTGCCAGGCTT-3′), and reaction mixes were incubated for 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 95°C and 30 s at 64°C (annealing and extension), followed by standard melting curve analysis on LightCycler 480 (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). GAPDH was selected as housekeeper using 5′-GGACTCATGACCACAGTCCAT-3′ as forward and 5′-AGGTCCACCACTGACACGTT-3′ as reverse primer.

Cytotoxicity assay

To analyze CAR T cell functionality, CD123-positive (KG-1, MOLM-13, and HNT-34) and CD123-negative (K-562) cell lines (Leibniz Institute, DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Braunschweig Germany) were selected as target cells, which were labeled using CellTrace Violet Cell Proliferation Kit, for flow cytometry (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, 25,000 of the labeled target cells (T) were plated in RPMI+10% FBS medium in a 96-well U-bottom plate together with different numbers of CAR T cells as effector cells (E): 3,125 for E:T = 0.125:1, 6,250 for E:T = 0.25:1, 12,500 for E:T = 0.5:1, 25,000 for E:T = 1:1, and 50,000 for E:T = 2:1. The whole CAR T cell population was used resulting in identical total cell numbers for every co-culture of the same E:T ratio. Target cells incubated in RPMI+10% FBS medium without effector cells were used as reference sample, and target cells treated with 0.1% Tween 20 were used as positive control. After 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 of co-culture, the cells were harvested, incubated with 7-AAD to stain dead cells, and analyzed on BD FACSCanto II. Cytotoxicity was calculated with the following formula: cytotoxicity [%] = 100% – (CellTrace Violet+7-AAD− cells in co-culture sample [%]/CellTrace Violet+7-AAD− cells in reference sample [%]) ∗ 100%.

Challenge assay

For characterization of CAR T cells after encountering target and non-target cells, CAR T cells were labeled using CellTrace Violet Cell Proliferation Kit, for flow cytometry (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions; 50,000 labeled CAR T cells were plated with 50,000 unlabeled KG-1 or K-562 cells in RPMI+10% FBS medium in a 96-well F-bottom plate and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 until analyses were performed. Therefore, cells were harvested and prepared for flow cytometry to analyze CellTrace+ cell fraction. CAR expression was determined by the proportion of F(ab’)₂+ cells within the CellTrace+ fraction. CAR T cell proliferation was calculated using the following formula: proliferation [x-fold] = initial MFICellTrace on day 0/MFICellTrace of CellTrace+ fraction on analysis day.

Statistics

Generation of the graphs and statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com). Values are presented as means ± SEM of independent experiments. Statistical tests were performed as noted in the figure legends, and p values were adjusted for multiple comparisons by Holm-Sidak test. Statistically significant differences were found when p < 0.05.

Data and code availability

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We greatly thank Marie-Madeleine Nzila and Dr. Robert Serfling for excellent technical assistance in the work with Neon Transfection System and 4D-Nucleofector. The project on which this publication is based was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research under the funding code 16GW0322.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, R.K., M.R., U.S.T.; methodology, R.K., M.R., R.G., S.P.; investigation, R.K., R.G., S.P.; formal analysis, R.K.; visualization, R.K.; funding acquisition, S.F., U.S.T.; project administration, S.F., U.S.T.; supervision, S.F., U.K., U.S.T.; writing – original draft, R.K.; writing – review & editing, all authors.

Declaration of interests

M.R., R.G., and S.P. are employed at Precision NanoSystems ULC.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtm.2023.101139.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.June C.H., O'Connor R.S., Kawalekar O.U., Ghassemi S., Milone M.C. CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science. 2018;359:1361–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.aar6711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanabe N., Mo F., McKenna M.K. Impact of Manufacturing Procedures on CAR T Cell Functionality. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.876339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X., Rivière I. Clinical manufacturing of CAR T cells: foundation of a promising therapy. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2016;3 doi: 10.1038/mto.2016.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maude S.L., Frey N., Shaw P.A., Aplenc R., Barrett D.M., Bunin N.J., Chew A., Gonzalez V.E., Zheng Z., Lacey S.F., et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1507–1517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melenhorst J.J., Chen G.M., Wang M., Porter D.L., Chen C., Collins M.A., Gao P., Bandyopadhyay S., Sun H., Zhao Z., et al. Decade-long leukaemia remissions with persistence of CD4+ CAR T cells. Nature. 2022;602:503–509. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04390-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miliotou A.N., Papadopoulou L.C. CAR T-cell Therapy: A New Era in Cancer Immunotherapy. Curr. Pharmaceut. Biotechnol. 2018;19:5–18. doi: 10.2174/1389201019666180418095526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wat J., Barmettler S. Hypogammaglobulinemia After Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-Cell Therapy: Characteristics, Management, and Future Directions. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022;10:460–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.10.037. In practice. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vora S.B., Waghmare A., Englund J.A., Qu P., Gardner R.A., Hill J.A. Infectious Complications Following CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell Therapy for Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020;7:ofaa121. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irving M., Lanitis E., Migliorini D., Ivics Z., Guedan S. Choosing the Right Tool for Genetic Engineering: Clinical Lessons from Chimeric Antigen Receptor-T Cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 2021;32:1044–1058. doi: 10.1089/hum.2021.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moretti A., Ponzo M., Nicolette C.A., Tcherepanova I.Y., Biondi A., Magnani C.F. The Past, Present, and Future of Non-Viral CAR T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2022;13:867013. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.867013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miliotou A.N., Papadopoulou L.C. In Vitro-Transcribed (IVT)-mRNA CAR Therapy Development. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020;2086:87–117. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0146-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soundara Rajan T., Gugliandolo A., Bramanti P., Mazzon E. In Vitro-Transcribed mRNA Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell (IVT mRNA CAR T) Therapy in Hematologic and Solid Tumor Management: A Preclinical Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:6514. doi: 10.3390/ijms21186514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beatty G.L., Haas A.R., Maus M.V., Torigian D.A., Soulen M.C., Plesa G., Chew A., Zhao Y., Levine B.L., Albelda S.M., et al. Mesothelin-specific chimeric antigen receptor mRNA-engineered T cells induce anti-tumor activity in solid malignancies. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014;2:112–120. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beatty G.L., O'Hara M.H., Lacey S.F., Torigian D.A., Nazimuddin F., Chen F., Kulikovskaya I.M., Soulen M.C., McGarvey M., Nelson A.M., et al. Activity of Mesothelin-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells Against Pancreatic Carcinoma Metastases in a Phase 1 Trial. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:29–32. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cummins K.D., Frey N., Nelson A.M., Schmidt A., Luger S., Isaacs R.E., Lacey S.F., Hexner E., Melenhorst J.J., June C.H., et al. Treating Relapsed/Refractory (RR) AML with Biodegradable Anti-CD123 CAR Modified T Cells. Blood. 2017;130:1359. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tchou J., Zhao Y., Levine B.L., Zhang P.J., Davis M.M., Melenhorst J.J., Kulikovskaya I., Brennan A.L., Liu X., Lacey S.F., et al. Safety and Efficacy of Intratumoral Injections of Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cells in Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017;5:1152–1161. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Svoboda J., Rheingold S.R., Gill S.I., Grupp S.A., Lacey S.F., Kulikovskaya I., Suhoski M.M., Melenhorst J.J., Loudon B., Mato A.R., et al. Nonviral RNA chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2018;132:1022–1026. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-03-837609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah P.D., Huang A.C., Xu X., Orlowski R., Amaravadi R.K., Schuchter L.M., Zhang P., Tchou J., Matlawski T., Cervini A., et al. Phase I Trial of Autologous RNA-electroporated cMET-directed CAR T cells Administered Intravenously in Patients with Melanoma & Breast Carcinoma. Cancer Res. Commun. 2023;3:821–829. doi: 10.1158/2767-9764.CRC-22-0486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi J., Ma Y., Zhu J., Chen Y., Sun Y., Yao Y., Yang Z., Xie J. A Review on Electroporation-Based Intracellular Delivery. Molecules. 2018;23:3044. doi: 10.3390/molecules23113044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DiTommaso T., Cole J.M., Cassereau L., Buggé J.A., Hanson J.L.S., Bridgen D.T., Stokes B.D., Loughhead S.M., Beutel B.A., Gilbert J.B., et al. Cell engineering with microfluidic squeezing preserves functionality of primary immune cells in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E10907–E10914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809671115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xin T., Cheng L., Zhou C., Zhao Y., Hu Z., Wu X. In-Vivo Induced CAR-T Cell for the Potential Breakthrough to Overcome the Barriers of Current CAR-T Cell Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.809754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rurik J.G., Tombácz I., Yadegari A., Méndez Fernández P.O., Shewale S.V., Li L., Kimura T., Soliman O.Y., Papp T.E., Tam Y.K., et al. CAR T cells produced in vivo to treat cardiac injury. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2022;375:91–96. doi: 10.1126/science.abm0594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parayath N.N., Stephan S.B., Koehne A.L., Nelson P.S., Stephan M.T. In vitro-transcribed antigen receptor mRNA nanocarriers for transient expression in circulating T cells in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:6080. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19486-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ye B., Hu Y., Zhang M., Huang H. Research advance in lipid nanoparticle-mRNA delivery system and its application in CAR-T cell therapy. Zhejiang da xue xue bao. Medical sciences. 2022;51:185–191. doi: 10.3724/zdxbyxb-2022-0047. Yi xue ban = Journal of Zhejiang University. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitchen S.G., Jones N.R., LaForge S., Whitmire J.K., Vu B.-A., Galic Z., Brooks D.G., Brown S.J., Kitchen C.M.R., Zack J.A. CD4 on CD8(+) T cells directly enhances effector function and is a target for HIV infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8727–8732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401500101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andries O., Mc Cafferty S., De Smedt S.C., Weiss R., Sanders N.N., Kitada T. N(1)-methylpseudouridine-incorporated mRNA outperforms pseudouridine-incorporated mRNA by providing enhanced protein expression and reduced immunogenicity in mammalian cell lines and mice. J. Contr. Release. 2015;217:337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moradian H., Roch T., Anthofer L., Lendlein A., Gossen M. Chemical modification of uridine modulates mRNA-mediated proinflammatory and antiviral response in primary human macrophages. Molecular therapy. Nucleic acids. 2022;27:854–869. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2022.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parr C.J.C., Wada S., Kotake K., Kameda S., Matsuura S., Sakashita S., Park S., Sugiyama H., Kuang Y., Saito H. N 1-Methylpseudouridine substitution enhances the performance of synthetic mRNA switches in cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:e35. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Billingsley M.M., Hamilton A.G., Mai D., Patel S.K., Swingle K.L., Sheppard N.C., June C.H., Mitchell M.J. Orthogonal Design of Experiments for Optimization of Lipid Nanoparticles for mRNA Engineering of CAR T Cells. Nano Lett. 2022;22:533–542. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c02503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Billingsley M.M., Singh N., Ravikumar P., Zhang R., June C.H., Mitchell M.J. Ionizable Lipid Nanoparticle-Mediated mRNA Delivery for Human CAR T Cell Engineering. Nano Lett. 2020;20:1578–1589. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b04246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka H., Miyama R., Sakurai Y., Tamagawa S., Nakai Y., Tange K., Yoshioka H., Akita H. Improvement of mRNA Delivery Efficiency to a T Cell Line by Modulating PEG-Lipid Content and Phospholipid Components of Lipid Nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:2097. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13122097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birkholz K., Hombach A., Krug C., Reuter S., Kershaw M., Kämpgen E., Schuler G., Abken H., Schaft N., Dörrie J. Transfer of mRNA encoding recombinant immunoreceptors reprograms CD4+ and CD8+ T cells for use in the adoptive immunotherapy of cancer. Gene Ther. 2009;16:596–604. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Auw N., Serfling R., Kitte R., Hilger N., Zhang C., Fricke S., Tretbar U.S. Comparison of two lab-scale protocols for enhanced mRNA-based CAR-T cell generation and functionality. Sci. Rep. 2023;13:18160. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-45197-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inoo K., Inagaki R., Fujiwara K., Sasawatari S., Kamigaki T., Nakagawa S., Okada N. Immunological quality and performance of tumor vessel-targeting CAR-T cells prepared by mRNA-EP for clinical research. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2016;3 doi: 10.1038/mto.2016.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris E., Elmer J.J. Optimization of electroporation and other non-viral gene delivery strategies for T cells. Biotechnol. Prog. 2021;37 doi: 10.1002/btpr.3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campillo-Davo D., De Laere M., Roex G., Versteven M., Flumens D., Berneman Z.N., van Tendeloo V.F.I., Anguille S., Lion E. The Ins and Outs of Messenger RNA Electroporation for Physical Gene Delivery in Immune Cell-Based Therapy. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:396. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13030396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paramasivam P., Franke C., Stöter M., Höijer A., Bartesaghi S., Sabirsh A., Lindfors L., Arteta M.Y., Dahlén A., Bak A., et al. Endosomal escape of delivered mRNA from endosomal recycling tubules visualized at the nanoscale. J. Cell Biol. 2022;221 doi: 10.1083/jcb.202110137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas A., M Garg S., De Souza R.A.G., Ouellet E., Tharmarajah G., Reichert D., Ordobadi M., Ip S., Ramsay E.C. Microfluidic Production and Application of Lipid Nanoparticles for Nucleic Acid Transfection. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1792:193–203. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7865-6_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akinc A., Querbes W., De S., Qin J., Frank-Kamenetsky M., Jayaprakash K.N., Jayaraman M., Rajeev K.G., Cantley W.L., Dorkin J.R., et al. Targeted delivery of RNAi therapeutics with endogenous and exogenous ligand-based mechanisms. Mol. Ther. 2010;18:1357–1364. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paunovska K., Da Silva Sanchez A.J., Lokugamage M.P., Loughrey D., Echeverri E.S., Cristian A., Hatit M.Z.C., Santangelo P.J., Zhao K., Dahlman J.E. The Extent to Which Lipid Nanoparticles Require Apolipoprotein E and Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor for Delivery Changes with Ionizable Lipid Structure. Nano Lett. 2022;22:10025–10033. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c03741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang R., El-Mayta R., Murdoch T.J., Warzecha C.C., Billingsley M.M., Shepherd S.J., Gong N., Wang L., Wilson J.M., Lee D., Mitchell M.J. Helper lipid structure influences protein adsorption and delivery of lipid nanoparticles to spleen and liver. Biomater. Sci. 2021;9:1449–1463. doi: 10.1039/d0bm01609h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gomes-Silva D., Mukherjee M., Srinivasan M., Krenciute G., Dakhova O., Zheng Y., Cabral J.M.S., Rooney C.M., Orange J.S., Brenner M.K., Mamonkin M. Tonic 4-1BB Costimulation in Chimeric Antigen Receptors Impedes T Cell Survival and Is Vector-Dependent. Cell Rep. 2017;21:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Long A.H., Haso W.M., Shern J.F., Wanhainen K.M., Murgai M., Ingaramo M., Smith J.P., Walker A.J., Kohler M.E., Venkateshwara V.R., et al. 4-1BB costimulation ameliorates T cell exhaustion induced by tonic signaling of chimeric antigen receptors. Nat. Med. 2015;21:581–590. doi: 10.1038/nm.3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fraietta J.A., Lacey S.F., Orlando E.J., Pruteanu-Malinici I., Gohil M., Lundh S., Boesteanu A.C., Wang Y., O'Connor R.S., Hwang W.-T., et al. Determinants of response and resistance to CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat. Med. 2018;24:563–571. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larson R.C., Maus M.V. Recent advances and discoveries in the mechanisms and functions of CAR T cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2021;21:145–161. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-00323-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fraietta J.A., Nobles C.L., Sammons M.A., Lundh S., Carty S.A., Reich T.J., Cogdill A.P., Morrissette J.J.D., DeNizio J.E., Reddy S., et al. Disruption of TET2 promotes the therapeutic efficacy of CD19-targeted T cells. Nature. 2018;558:307–312. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0178-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kloss C.C., Lee J., Zhang A., Chen F., Melenhorst J.J., Lacey S.F., Maus M.V., Fraietta J.A., Zhao Y., June C.H. Dominant-Negative TGF-β Receptor Enhances PSMA-Targeted Human CAR T Cell Proliferation And Augments Prostate Cancer Eradication. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:1855–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Webb C., Ip S., Bathula N.V., Popova P., Soriano S.K.V., Ly H.H., Eryilmaz B., Nguyen Huu V.A., Broadhead R., Rabel M., et al. Current Status and Future Perspectives on MRNA Drug Manufacturing. Mol. Pharm. 2022;19:1047–1058. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.2c00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.