Abstract

α-Synuclein and tau are abundant multifunctional brain proteins that are mainly expressed in the presynaptic and axonal compartments of neurons, respectively. Previous works have revealed that intracellular deposition of α-synuclein and/or tau causes many neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Despite intense investigation, the normal physiological functions and roles of α-synuclein and tau are still unclear, owing to the fact that mice with knockout of either of these proteins do not present apparent phenotypes. Interestingly, the co-occurrence of α-synuclein and tau aggregates was found in post-mortem brains with synucleinopathies and tauopathies, some of which share similarities in clinical manifestations. Furthermore, the direct interaction of α-synuclein with tau is considered to promote the fibrillization of each of the proteins in vitro and in vivo. On the other hand, our recent findings have revealed that α-synuclein and tau are cooperatively involved in brain development in a stage-dependent manner. These findings indicate strong cross-talk between the two proteins in physiology and pathology. In this review, we provide a summary of the recent findings on the functional roles of α-synuclein and tau in the physiological conditions and pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. A deep understanding of the interplay between α-synuclein and tau in physiological and pathological conditions might provide novel targets for clinical diagnosis and therapeutic strategies to treat neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: alpha-synuclein, microtubule-associated protein, neurodegenerative disease, tau

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases are diagnosed on the basis of clinical symptoms in individuals mainly with progressive cognitive declines and motor impairments caused by synaptic loss and neuronal cell death. To date, Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorders, remain incurable and there are only very limited symptomatic treatments despite decades of searching for effective cures (Ke et al., 2012; Moussaud et al., 2014; Reich and Savitt, 2019; Hacker et al., 2020). PD and AD are neuropathologically defined by the presence of misfolded and aggregated α-synuclein (αSyn) and tau, respectively (Goedert et al., 1988; Spillantini et al., 1997). Both αSyn and tau are intrinsically disordered proteins abundantly expressed in the brain (Maroteaux and Scheller, 1991; Mukrasch et al., 2009), where αSyn is highly concentrated in presynaptic terminals (Maroteaux et al., 1988), whereas tau is a major neuronal microtubule-associated protein (MAP) abundantly expressed in neuronal axons (Cohen et al., 2011). Both proteins possess a propensity to organize toxic oligomers and abnormal intracellular amyloid fibrils with similar β-strand rich structures, which lead to neurodegeneration and neuronal cell death (Fitzpatrick et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018).

Increased dosage of αSyn and its N-terminal point mutations trigger the formation of abnormal protein aggregates known as Lewy bodies (LBs) and Lewy neurites (LNs), which are intimately associated with familial PD, PD with dementia, dementia with LBs (DLBs), and other related synucleinopathies (Spillantini et al., 1997; Irizarry et al., 1998; Goedert, 2001; Singleton et al., 2003). Similarly, hyperphosphorylated tau forms intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (INFs), and dominantly inherited mutations in the MAPT gene (which encodes tau protein) are believed to cause tauopathies including AD, frontotemporal dementia (FTD), progressive supranuclear palsy, frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 and other tauopathies (Poorkaj et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2001; Ghetti et al., 2015). Thus, although synucleinopathies and tauopathies are generally characterized by different pathogenic proteins, they share common clinical features in cognitive/behavioral and movement disorders, strongly suggesting the existence of cross-talk between αSyn and tau in the development of neurodegenerative diseases. Indeed, co-deposition of αSyn and tau aggregates was often found in post-mortem brains, and the overlapping clinical symptoms of dementia and parkinsonism have also been reported (Robinson et al., 2018; Twohig and Nielsen, 2019; Pan et al., 2021). Accumulating evidence also shows the occurrence of molecular interactions and cross-seeding between αSyn and tau in neurodegenerative disorders (Kayed et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2020). Conversely, our recent study demonstrated the critical cooperation of αSyn and tau during proper corticogenesis (Wang et al., 2022). Here, we aim to summarize the functional cross-talks of αSyn and tau in physiological and pathogenic conditions.

Search Strategy

All studies cited in this review were searched on PubMed and Science Direct using the following keywords: neurodegenerative diseases, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple system atrophy, synucleinopathies, tauopathies, α-synuclein and/or tau, amyloid-beta, oligomerization, fibrillization, posttranslational modification, neurotoxicity and therapy. Selected references were published from 1975 to 2023. No limits were used

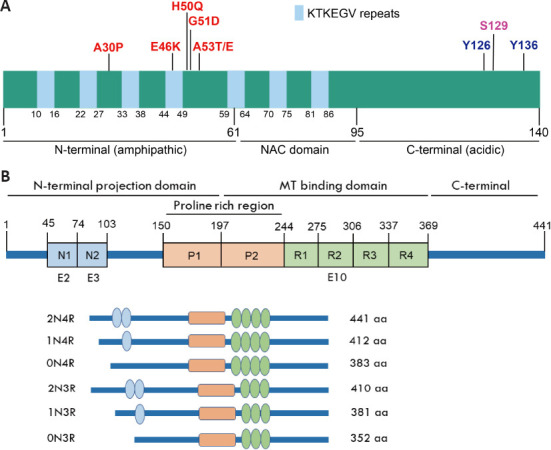

Physiological and Pathological Properties of α-Synuclein

αSyn, a small protein comprised of 140 amino acids (aa), was originally identified from the electric organ synapses of the Torpedo ray (Maroteaux et al., 1988). Subsequent studies revealed that αSyn is an abundant mammalian brain protein mainly expressed in presynaptic terminals, and is less abundant in muscle, red blood cells, and lymphocytes (Jakes et al., 1994; Askanas et al., 2000; Barbour et al., 2008). Under physiological conditions, αSyn is a natively unfolded protein structurally subdivided into three regions: an N-terminal amphipathic region (1–60 aa), a central hydrophobic nonamyloid-β component region (61–95 aa) and a highly acidic C-terminal region (96–140 aa) (Figure 1A; Fusco et al., 2014; Siddiqui et al., 2016). In addition, endogenous αSyn is also reported to form α-helical tetramers in cell cultures and brain tissue that are resistant to pathogenic aggregation (Bartels et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011). In the brain, αSyn is preferentially expressed in the neocortex, hippocampus, substantia nigra, thalamus, and cerebellum, where it binds presynaptic vesicles and regulates the release and reuptake of neurotransmitters (Jao et al., 2008; Trexler and Rhoades, 2009), playing an important role in synaptic plasticity (Figure 2A; Burré et al., 2010; Kahle et al., 2000). Studies using a combination of solid-state and solution NMR spectroscopy have revealed that the N-terminal amphipathic region works as a membrane anchor, the central nonamyloid-β component region acts as a sensor of the lipid properties and the acidic C-terminal region weakly binds to the lipid membrane (Fusco et al., 2014). The release of neurotransmitters in presynaptic nerve terminals requires SNARE-complex assembly, which is promoted by αSyn via direct interaction with synaptobrevin-2/vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (Burré et al., 2010). Both Endogenous and overexpressed αSyn bind to synaptic vesicles (SVs) and accelerates the kinetics of exocytotic events, promoting cargo discharge with dose-dependent effects on dilation of the exocytotic fusion pore in adrenal chromaffin cells (Logan et al., 2017). However, PD-linked αSyn A30P and A53T lose the effect on fusion pore dilation. Other works also reported that disruption of αSyn by a pan-synuclein antibody leads to dispersion of SVs, as well as the reduction in the reserve pool at lamprey synapse (Fouke et al., 2021), modest overexpression of αSyn markedly inhibits the exocytosis and reclustering of SVs (Nemani et al., 2010). Conversely, triple knockout mice lacking all three synuclein family members (α-, β-, and γ-synuclein) displayed more tightly clustered SVs in mice (Vargas et al., 2017), corroborating the involvement of other critical presynaptic proteins, such as synapsin and amphiphysin during SV clustering and docking (Nemani et al., 2010; Vargas et al., 2017).

Figure 1.

Structural features of αSyn and tau proteins.

(A) Schematic illustration of αSyn. αSyn is comprised of 140 aa and structurally subdivided into three regions: an N-terminal amphipathic region (1–60 aa), a central hydrophobic nonamyloid-β component (NAC) region (61–95 aa) and a highly acidic C-terminal region (96–140 aa). Seven repeats of the lipid-binding motif (XKTKEGVXXXX) consisted of 11 aa involved in the interaction with lipid membrane. PD causing point mutations is mainly located in the N-terminus, three posttranslational modification (PTM) residues located in the C-terminus. (B) Schematic illustration of tau isoforms. Tau protein is comprised of an N-terminal projection domain, a central MT-binding domain and a C-terminal tail. The alternative splicing of E2, E3 and E10 generates six human tau isoforms. According to the N-terminal inserts encoded by E2 and E3, and the C-terminal insert encoded by E10, tau isoforms can be divided in 2N4R, 1N4R, 0N4R, 2N3R, 1N3R, and 0N3R.

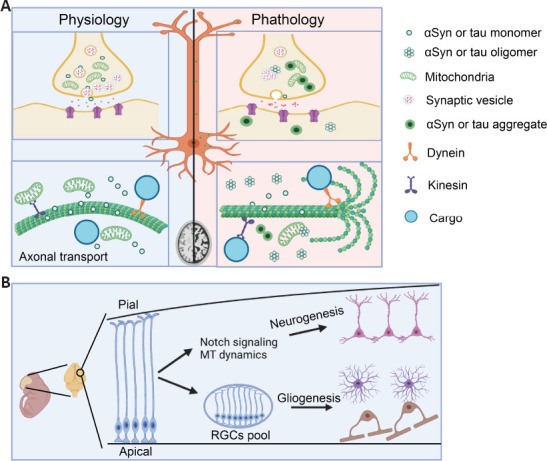

Figure 2.

Physiological and pathological functions of αSyn and tau in central nervous system.

(A) Physiological and pathological functions of αSyn and tau. Both αSyn and tau are neuronal microtubule-associated proteins highly expressed in presynaptic terminals and axonal compartments, respectively. While αSyn mainly involves in neurotransmitter release and reuptake, tau promotes microtubule (MT) assembly and stability in the axon. Emergence of protein oligomers or aggregates disturbs signal transduction and axonal transport regulated by αSyn and tau, producing neurotoxicity and neuronal cell damages. (B) Cooperative function of αSyn and tau during corticogenesis. In the early embryonic stage, αSyn and tau participate in neurogenesis via regulating Notch signaling and MT dynamics. αSyn and tau are tightly maintenance of neuroprogenitor pool during neurogenesis to ensure following gliogenesis in the later embryonic stage. RGC: Radial glial cell; αSyn: α-synuclein.

Although it is still under debate, previous works have reported that αSyn also plays roles in cytoskeleton dynamics. Ordonez and colleagues have demonstrated that αSyn expression promotes the reorganization of the actin filament (F-actin) network through interaction with spectrin, by which the mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 is mislocalized, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal death in a Drosophila model of α-synucleinopathy (Ordonez et al., 2018). Cofilin 1, another actin-binding protein, promotes αSyn aggregation and transmission in vitro and in vivo, resulting in more severe neuronal degeneration and motor impairment in a mouse model of PD (Yan et al., 2022). On the other hand, αSyn also interacts with the tubulin tetramer that seems to promote microtubule (MT) nucleation and outer growth (Cartelli et al., 2016), but the MT binding region of αSyn has not been defined accurately. Several different MT binding sites of αSyn have been reported that cover the entire protein sequence, indicating that all regions of αSyn are necessary for tubulin and MT assembly (Alim et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2010; Cartelli et al., 2016). Our previous study also demonstrated that recombinant αSyn protein promotes the formation of relatively short MTs and its stability in vitro and is further involves in the formation of short transportable MTs that are important for axonal transport (Figure 2A; Toba et al., 2017). In addition, αSyn is detected in the nucleus (Maroteaux et al., 1988; McLean et al., 2000). Nuclear αSyn has been reported to bind transcription factors to regulate protein expression (Desplats et al., 2012; Siddiqui et al., 2012); and bind double-stranded DNA to participate in DNA repair (Schaser et al., 2019).

For the past several decades, the pathological relationship between αSyn aggregation and synucleinopathies has received particular attention, especially in the pathogenesis of PD, the second most common neurodegenerative disease (Figure 2A). The soluble monomeric αSyn misfolds into insoluble aggregates and amyloid fibrils known as LBs and LNs, the major neuropathological hallmarks found in post-mortem brains with synucleinopathies (Spillantini et al., 1997; Goedert, 2001), suggesting a central role of αSyn in these disorders. A well-established pathologic trait of PD is the synaptic loss and death of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons triggered by misfolded αSyn aggregates, leading to characteristic disabling motor symptoms, such as resting tremor, muscular rigidity, bradykinesia and postural instability (Goedert, 2001; Maiti et al., 2017). αSyn fibrils also target other brain regions, such as the cortex and hippocampus, resulting in the impairment of synaptic transmission, neuronal cell death, and memory damage in PD patients (Diógenes et al., 2012; Durante et al., 2019).

Systematic analyses of αSyn purified from normal and diseased brains have revealed that αSyn was extensively subjected to numerous posttranslational modifications (PTMs), some of which are considered to be associated with disease progression or initiation (Anderson et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2023). Of all PTMs, αSyn phosphorylation is the most widely studied due to its regulatory roles in oligomerization, misfolding, fibrillization, and neurotoxicity in vivo. For instance, αSyn phosphorylation at Serine-129 (S129-P) is the most prevalent PTM detected in LBs, LNs, and glial cytoplasmic inclusions of post-mortem patient brains (Fujiwara et al., 2002; Anderson et al., 2006). S129-P possesses the ability to promote the formation of αSyn oligomers and filaments in vitro (Fujiwara et al., 2002) and accelerates neuronal loss in αSyn transgenic mice (Rieker et al., 2011). However, several works have proposed disparate effects of S129-P on health. Paleologou and colleagues have reported that S129-P αSyn inhibits its fibril formation in vitro without affecting membrane-bound conformation (Paleologou et al., 2008). Consistent with this, Buck et al. have revealed that an increase in the phosphorylation level of endogenous αSyn by overexpression of polo-like kinase (PLK) 2 or PLK3 in the substantia nigra did not induce nigral dopaminergic cell death and did not show any accumulation of αSyn protein or formation of inclusions (Buck et al., 2015). Furthermore, recent work found that neuronal activity-dependent αSyn phosphorylation is S129-specific, reversible, and confers no cytotoxicity at synapsin-containing presynaptic boutons (Ramalingam et al., 2023).

Interestingly, although the level of S87-P αSyn is also increased in cell cultures and transgenic animal models of synucleinopathies, especially in patient brains with PD, AD, LB disease and multiple system atrophy, pathogenic αSyn aggregation and neurotoxicity were attenuated after phosphorylation at S87 in vitro and its mimicking phosphorylation in vivo (Paleologou et al., 2010; Oueslati et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2023). These findings suggest that S87-P may be an attractive new drug target for the treatment of related synucleinopathies. Our recent study found a new PTM at αSyn tyrosine-126 (Y126) by tyrosine hydroxylase (TH). TH hydroxylates αSyn Y126 to Y126DOPA, and this hydroxylation promotes the formation of short fibrils/oligomers. Increasing evidence suggests that αSyn oligomers are precursors to LB pathologies and display more toxicity to affected neurons than insoluble aggregates (Bengoa-Vergniory et al., 2017). Consistently, the short fibrils/oligomers of αSyn produced higher neurotoxicity to cultured PC12 cells than the control (Jin et al., 2022). Furthermore, we detected Y126DOPA modifications in αSyn A53T transgenic mice and human brains with PD and multiple system atrophy using a specific antibody against Y126DOPA, this may be a reason why αSyn aggregation selectively attacks TH-positive dopaminergic neurons in the PD brain (Jin et al., 2022). Notably, these disease-associated PTMs of αSyn are possibly involved in its oligomerization, aggregation, and pathology spreading.

Point mutations in the N-terminus amphipathic region of the human SNCA gene (which encodes αSyn), such as A30P, E46K, A53T/E, H50Q, and G51D, have been reported to cause an autosomal dominant form of PD (Wong and Krainc, 2017). Besides, alterations in αSyn dosage by genomic duplication or triplication in the SNCA gene have been reported to cause familial PD, and the gene dosage is directly linked to disease severity and survival (Singleton et al., 2003; Chartier-Harlin et al., 2004). Mutations or multiplications in the SNCA gene accelerate αSyn fibrillization and increase its toxicity (Xu and Pu, 2016).

It has also demonstrated the potential involvement of αSyn in the pathogenesis of AD (Twohig and Nielsen, 2019). LB pathologies were found in 10–40% of AD patients who were diagnosed with memory impairments and faster cognitive declines (Olichney et al., 1998; Hyman et al., 2012; Rabinovici et al., 2016). Moreover, αSyn aggregates were also found in cytoplasmic inclusions of oligodendrocytes that cause multiple system atrophy (Gai et al., 1998; Sorrentino et al., 2018). Interestingly, the C-terminus of αSyn can directly interact with the MT-binding region of tau and inhibit the binding of tau to tubulin and MTs, resulting in increased concentrations of free tau (Jensen et al., 1999), which may be a reason why cerebrospinal fluid tau is increased in AD patients (Vergallo et al., 2018). Molecular interaction and cross-seeding were also confirmed between amyloid-beta (Aβ) and αSyn. Although, several studies reported co-deposition of αSyn and Aβ in AD patients (Jensen et al., 1995, 1997), Bachhuber and colleagues found that an interaction between αSyn and Aβ inhibits Aβ deposition and reduces plaque formation (Bachhuber et al., 2015).

Tau in Physiology and Pathology

Tau was originally identified in the porcine brain as a neuronal MAP (Weingarten et al., 1975). Similar to αSyn, tau is another intrinsically disordered protein that is preferentially expressed in neuronal axons, but is less abundant in cell bodies, nuclei, and synaptic terminals, as well as in glial cells such as astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (LoPresti et al., 1995; Merino-Serrais et al., 2013; Wang and Mandelkow, 2016). Alternative mRNA splicing occurring in exons 2, 3, and 10 of tau gives rise to six isoforms (Figure 1B), which are subdivided into four microtubule-binding repeat (4R) and 3R forms with different distribution patterns (Lee et al., 1988; Wang and Mandelkow, 2016). The insertion of repeat domain R2 encoded by exon 10 in 4R tau increased MT binding affinity with more efficient effects on promoting MT assembly than 3R tau. All of them are mainly expressed in the adult human brain, but only 3R tau is expressed in the fetal brain (Chen et al., 2010). On the other hand, in mice, only 4R tau is exclusively present in the adult brain, and 3R isoforms are predominant during the developmental stage of the embryonic brain (Lee et al., 1988; Goedert and Jakes, 1990). In the cerebral cortex of healthy adults, the amounts of 3R and 4R tau are equal (Ke et al., 2012; Niblock and Gallo, 2012), and alterations in the ratio of 3R:4R tau have been strongly implicated as a cause of neurodegeneration (Chen et al., 2010; Espíndola et al., 2018; Damianich et al., 2021). Conversely, the expression of tau in the grey matter of the neocortex is roughly two times higher than that in the white matter (Majounie et al., 2013; Mietelska-Porowska et al., 2014). Thus, accurate regulation of tau mRNA alternative splicing is critical for the maintenance of neuronal function and survival.

In the central nervous system, tau plays critical roles in regulating MT dynamics, depending on its phosphorylation state (Rodríguez-Martín et al., 2013). MT binding affinity of tau is modulated by MT affinity-regulating kinases (MAPK, PKA, or CaMKII) and protein phosphatases (PP1, PP2A, PP2B, PP2C, or PP5) (Wang and Mandelkow, 2016). The phosphorylation of tau reduces the MT binding affinity of tau and triggers the detachment of tau from MTs. tau modulates the assembly and stability of MTs by interacting with the C-terminus of tubulin. A recent cryo-EM study using a combination of single-particle analysis and Rosetta modeling has generated atomic models of tau-tubulin interaction and revealed the tau binding region in the interface between tubulin dimers (Kellogg et al., 2018). Importantly, tau is also reported to promote the assembly of labile MTs at its plus end. Axonal MTs contain stable domains towards the proximal end and labile domains towards the distal end, where tau is mainly enriched on the labile domain. In line with this, tau-depleted cultured neurons increased the stable MT mass but not the labile MTs (Tint et al., 1998; Qiang et al., 2018). Although, these findings are inconsistent with the broadly accepted idea that tau stabilizes MTs (Baas and Qiang, 2019), restoring the labile MT mass in brains with tauopathies may be an appropriate treatment. In addition, tau further participates in MT-mediated axonal transport, where tau differentially regulates motor-driven retrograde (towards the cell body driven by dynein motors) and anterograde transports (towards the axonal terminus driven by kinesin motors) (Figure 2A; Felgner et al., 1997; Dehmelt and Halpain, 2005; Kellogg et al., 2018). However, the ablation of tau did not affect axonal transport apparently, which critically depends on the stability of MTs in cultured primary neurons or in mouse optic nerve axons (Yuan et al., 2008, 2013). These results also support the notion that tau promotes labile MT assembly rather than acting as an MT stabilizer. In addition, increased MT stability in tau-depleted cell cultures may be functionally compensated by other MAPs, such as MAP1A, MAP2, and MAP6 (Harada et al., 1994; Dehmelt and Halpain, 2005; Qiang et al., 2018).

Besides its well-known roles in MT dynamics, low-level distribution of tau in synaptic terminals is considered to play important roles in cell signaling and synaptic plasticity (Ittner et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2017). Other studies found that tau proteins are involved in the regulation of the microenvironment within neurovascular units under physiological conditions (Guo et al., 2017; Michalicova et al., 2020). Additionally, nuclear tau possesses a DNA-binding capacity that plays roles in DNA protection, integrity, and nucleocytoplasmic transport (Violet et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2017; Benhelli-Mokrani et al., 2018).

Intracellular accumulation of abnormal tau in the human brain has been implicated in many neurodegenerative diseases known as tauopathies, where hyper- and abnormally phosphorylated tau proteins are misfolded into neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) (Figure 2A; Alonso et al., 2001; Morris et al., 2011). Neurofibrillary pathology is the hallmark of tauopathies that is propagated through connected normal cells with prion-like properties during disease progression (Mocanu et al., 2008; Ferrer et al., 2014; Kaufman et al., 2016). Previous works have revealed that mutations in the MAPT gene and hyperphosphorylation in tau proteins accelerate the formation of tau aggregates in vitro and in vivo, which affect multiple domains, including behavior, language, memory, and motor function (Alonso et al., 2001; Pan et al., 2021). Tau isoform components present in their aggregates determine different tauopathies. For example, all six tau isoforms are mixed in individuals with AD and frontotemporal dementia, and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17. In contrast, only 4R tau isoforms are found in other tauopathies, such as argyrophilic grain disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, and globular glial tauopathy; whereas in Pick’s disease, only 3R tau inclusions are detected (Fitzpatrick et al., 2017; He et al., 2020; Dregni et al., 2022).

AD, the most common tauopathy, is characterized histopathologically by the deposition of Aβ in extracellular plaques and by the accumulation of tau NFTs in the neurites of neurons. Accumulated clinicopathologic evidence has revealed that the deposition of Aβ and tau is intimately correlated with neuronal loss and cognitive decline (Goedert, 2015). The exposure of neurons to Aβ oligomers also leads to tau mislocalization into the somatodendritic compartment, by which tubulin-tyrosine-ligase-like-6 is mislocalized into the dendrites, inducing spastin-mediated MT severing. This abnormal process was shown to trigger a dramatic loss of MTs, mislocalization of mitochondria, and loss of mature spines in a cellular model system of AD (Zempel and Mandelkow, 2015). Hyperphosphorylated tau, the main component of tau aggregates, reduces the ability of tau to bind MTs and promote MT assembly, resulting in an increase in non-MT-associated tau proteins in cells (Alonso et al., 1994; Wang and Mandelkow, 2016). These functionally abnormal tau proteins prefer to induce self-aggregates of paired-helical-filaments (PHFs) and straight filaments in neurons and glial cells (Feuillette et al., 2010; Ferrer et al., 2014), producing MT catastrophe in affected cells (Alonso et al., 1994). Furthermore, abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau was found to directly interact with F-actin and increase its stability in Drosophila and mouse models of tauopathy (Fulga et al., 2007). Increased stability of F-actin affected mitochondrial fission protein DRP1 distribution to mitochondria, resulting in elongated mitochondria and its dysfunction in both Drosophila and mouse neurons (DuBoff et al., 2012).

Mutations in exonic and intronic regions of the human MAPT gene cause tauopathies, including frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17, Pick’s disease, argyrophilic grain disease, corticobasal degeneration, and progressive supranuclear palsy (Spillantini et al., 1998; Espíndola et al., 2018). More than 80 mutations in the MAPT gene have been identified so far, emphasizing the importance of tau in neurodegeneration (Ghetti et al., 2015; Wang and Mandelkow, 2016). Similar to abnormal phosphorylation, tau mutations also display a loss of function in the affinity for MTs, and a gain of cytotoxicity owing to self-aggregation. Interestingly, some of these mutations change the relative ratio of 4R to 3R tau isoforms via varying exon 10 splicing and thus trigger tau aggregation (Hasegawa et al., 1998; Hong et al., 1998; Spillantini et al., 1998; Ghetti et al., 2015). Animal models with human tau mutations have been extensively studied as disease models (Fulga et al., 2007; Mocanu et al., 2008; Gamache et al., 2019, 2020). Genetic evidence further revealed that the MAPT gene is also one of the risk loci for PD. Several studies have confirmed MAPT involvement in cognitive impairment or dementia in PD, suggesting that the MAPT gene also participates in disease onset and contributes to the diverse clinical manifestations of PD (Pan et al., 2021).

Neuropathological Co-aggregation and Cross-Seeding

Generally, the intracellular accumulation of αSyn inclusions in the brain is the major neuropathological hallmark of PD and related synucleinopathies, while the intracellular deposition of hyperphosphorylated tau aggregates is the neuropathological trait of AD and related tauopathies. Thus, major neuropathological features are quite distinct between synucleinopathies and tauopathies. Accumulating evidence suggests that αSyn contributes to the pathophysiology of AD, and tau is also known as a risk factor and mediator in the pathogenesis of PD (Twohig and Nielsen, 2019; Pan et al., 2021). In line with this, αSyn-containing LBs were found in more than half of familial and sporadic cases of AD, and NFTs of tau were frequently observed in the autopsies of patients with PD (Ishizawa et al., 2003; Li et al., 2016). In addition, the frequent co-deposition of different disease protein aggregates was found in the same brain lesions. For example, the co-existence of pathological αSyn and tau in the same inclusions has been found in PD dementia, the LB variant of AD, and DLBs (Arima et al., 2000; Giasson et al., 2003; Ishizawa et al., 2003; Colom-Cadena et al., 2013). More importantly, accumulating clinical evidence has revealed overlap in the disease phenotypes characterized by parkinsonism and dementia (Arima et al., 2000; Ishizawa et al., 2003), suggesting remarkable cross-talks between these two proteins in the pathogenesis of multiple neurodegenerative disorders.

Both αSyn and tau are prone to misfolding into pathological fibrils and aggregates. At the molecular level, the two proteins interact with each other in vitro and in vivo. The negatively charged C-terminus of αSyn directly interacts with the MT binding region of tau that synergistically promotes the aggregation and fibrillization of each other (Jensen et al., 1999; Giasson et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2022). Emerging evidence suggests that fibrillization occurs in a nucleation-dependent manner, followed by seed-dependent propagation (Nonaka et al., 2010). The injection of pathological conformers of αSyn or tau into healthy tissue has been shown to cross-seed each aggregation in animal models (Clavaguera et al., 2009; Guo and Lee, 2014). A recent study demonstrated that intracerebral injection of tau strains extracted from different tauopathy brains into 6hTau mice expressing the equal ratio of human 3R and 4R tau isoforms induced cell-type specific tau pathologies composed of the same isoform (He et al., 2020). Most notably, prion-like propagation of disease proteins was confirmed in several human PD patients in whom the striatum was implanted with fetal human midbrain neurons. LB-like inclusions were found in grafted nigral neurons 11–16 years after transplantation, suggesting that pathogenic proteins can propagate from the host to transplanted cells (Kordower et al., 2008; Li et al., 2008).

The conversion of soluble αSyn and tau into insoluble amyloid-like fibrils and aggregates is the central event in the development of neurodegeneration. Mutations in the SNCA or MAPT gene promote protein aggregation and disease progression. Interestingly, distinct αSyn strains displayed different efficiencies in cross-seeding tau aggregation in neuronal cells and in human P301S tau transgenic mice (Guo et al., 2013). Previous works also revealed that the overexpression of αSyn in oligodendroglial cells promotes tau aggregation (Riedel et al., 2009), and a familial PD mutation, A53T αSyn, causes the ectopic localization of tau to postsynaptic spines, culminating in postsynaptic deficits (Singh et al., 2019). This tau-mediated synaptic dysfunction was considered to contribute to hippocampal network hyperexcitability and exacerbate cognitive dysfunction in a PD mouse model (Singh et al., 2019). In addition, Teravskis and colleagues revealed that human A53T αSyn, but not A30P or E46K mutations, induces GSK3β-dependent tau phosphorylation and calcineurin-dependent loss of postsynaptic surface AMPA receptors, which leads to tau missorting to dendritic spines and postsynaptic dysfunction in A53T αSyn transgenic mice (Teravskis et al., 2018). Given the importance of tau in the development of dementia, tau abnormalities occurring in A53T αSyn transgenic mice may contribute to dementia (Irwin et al., 2017; Teravskis et al., 2018). Similarly, the overexpression of tau promotes the aggregation of αSyn and increases its size in neuronal cell models, exacerbating cytotoxicity (Badiola et al., 2011). Furthermore, tau-modified αSyn fibrils enhanced seeding activity and displayed more severe motor symptoms and cognitive dysfunction in mice (Pan et al., 2022).

Studies combining clinical diagnosis with autopsy have also found that Lewy-related pathology and AD neuropathology occur in healthy elderly individuals who do not develop parkinsonism and/or dementia during their lifetime (Knopman et al., 2003; Markesbery et al., 2009; Kok et al., 2022). For instance, around 24% of the autopsied healthy control cases exhibited Lewy-related pathology, and 20–40% of the cognitively normal older individuals exhibited AD pathology (Knopman et al., 2003; Markesbery et al., 2009). These findings have led to the speculation that some individuals are more resistant to the disease pathology, and some individuals are in a presymptomatic disease stage. Of note, mutations occurring in the PRKN gene (which encodes parkin protein) or LRRK2 gene (which encodes LRRK2 protein) also elicit neuronal degeneration without αSyn-related pathologies or tau inclusions (Gaig et al., 2009; Calogero et al., 2019). Other works have also suggested that dysfunction in autophagy, a protein degradation system, is implicated in neurodegeneration (Fîlfan et al., 2017). These works support the notion that abnormal protein inclusions in the central nervous system may work as protective events (Markesbery et al., 2009; Kok et al., 2022). In addition, aging itself is the strongest risk factor for neurodegeneration. Taken together, these findings support the notion that the soluble oligomeric forms of αSyn and tau, but not insoluble fibrils or aggregates are the main culprits for neurodegeneration (Bengoa-Vergniory et al., 2017).

Cooperative Functions of α-Synuclein and tau during Brain Development

Owing to their disease relevance, αSyn and tau have received particular attention in the physiological functions and pathogenic mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases. Unfortunately, their physiological functions remain largely elusive, as mice with complete deletion of either of these proteins do not present overt phenotypes (Harada et al., 1994; Abeliovich et al., 2000; Ke et al., 2012). Both αSyn and tau are known to promote MT assembly and stability in vitro (Cleveland et al., 1977; Toba et al., 2017). These works strongly indicate that some functional redundancy may exist among neuronal MT-binding proteins (Harada et al., 1994; Qiang et al., 2018).

Neuronal MTs are essential for cell morphology, neurodevelopment, and maintenance of physiological functions, especially axonal transport (Sleigh et al., 2019). Hence, mutations in tubulins or neuronal MT-binding proteins have been implicated in the induction of many neurodevelopmental (Fallet-Bianco et al., 2008; Jin et al., 2017) and neurodegenerative diseases (Calogero et al., 2019; Shafiq et al., 2021). The interaction of αSyn with tau disturbs the tau-tubulin interaction and promotes tau hyperphosphorylation, resulting in MT disorganization and tau aggregation (Jensen et al., 1999; Moussaud et al., 2014).

Our recent work has shown that αSyn–/–tau–/– mice presented smaller brains in adulthood, but displayed a large brain in size during the embryonic stage (Wang et al., 2022). We also found that loss of αSyn and tau functions caused a reduction in Notch signaling, resulting in accelerated neurogenesis at the early embryonic stage. In utero experiments during the embryonic day (E) 12–E14 confirmed accelerated interkinetic nuclear migration in the ventricular zone and overproduction of early-born neurons in the neocortex. Consequently, overconsumption of progenitor cells occurred in the early embryonic stage, by which neural progenitor cells were quickly decreased at the middle stage, this ultimately affected gliogenesis (oligodendrogenesis and astrogenesis) at the later stage of corticogenesis (Figure 2B). The ablation of αSyn and tau further suppressed the expansion and maturation of macroglial cells (oligodendrocytes and astrocytes) concomitant with increased neuronal cell density in the postnatal brain, which in turn reduced the brain size and cortical thickness compared with the control. Thus, our study revealed the functional cooperation of αSyn and tau during corticogenesis (Wang et al., 2022). The underlying mechanisms by which αSyn and tau cooperatively regulate Notch signaling pathway and microtubule dynamics need to be elucidated with additional studies in the near future.

Implications for Therapy

Understanding the molecular pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases including PD and AD provides new opportunities for the development of effective therapies. The pathological interaction of αSyn and tau has been implicated in promoting their fibrillization and cross-seeding (Jensen et al., 1999). In addition, studies using transgenic mice overexpressing wild-type or familial PD mutations of αSyn led to tau hyperphosphorylation and misfolding resembling NFTs that were found in patient brains (Jensen et al., 1999). It is reasonable to assume that there is a drug that can prevent abnormal interactions between αSyn and tau, may disturb or halt the initiation of fibrillization and cross-seeding. However, our recent study revealed that αSyn and tau cooperatively execute critical roles during corticogenesis, and the loss of their physiological functions destroyed the balance between neuronal cells and glial cells (Wang et al., 2022). Both αSyn and tau interact with tubulin and promote MT assembly, suggesting that developmental abnormalities are attributed to disturbed MT dynamics. Although further study is needed to clarify the precise mechanisms underlying the cooperative functions of αSyn and tau during brain development, our findings may provide new mechanistic insights and expand the therapeutic opportunities for neurodegenerative diseases.

Transcellular propagation of protein pathogens in a prion-like manner is widely accepted as a necessary event in the pathogenesis and progression of neurodegenerative diseases (Goedert, 2015, 2017). An expanding number of studies focusing on the oligomeric forms of pathogenic proteins have reported that early-formed soluble protein oligomers are the pathogenic and neurotoxic species that lead to disease initiation and propagation rather than the insoluble forms of fibril aggregates (Paleologou et al., 2009; Sengupta et al., 2015). Furthermore, elevated amounts of soluble oligomers are linked to disease severity and are considered the culprits that cause neuronal damage and degeneration (Nonaka et al., 2010). The inhibition of soluble oligomer release or reuptake might be a therapeutic target.

Based on the neurotoxicity from soluble oligomers or protofibrils, an effective approach might be developed to remove them from the patient brain. Although there remain many challenges, immunotherapy research has made many achievements in AD treatment. After some failures in clinical trials, such as those of bapineuzumab, solanezumab, and crenezumab (Salloway et al., 2014; Cummings et al., 2018; Honig et al., 2018), some monoclonal antibodies are now making it through to the late phase of clinical development. Aducanumab, with the brand name of Aduhelm, is an anti-human Aβ antibody that targets its aggregated forms and binds to amino acids 3–7 of the Aβ peptide (Sevigny et al., 2016); lecanemab, sold under the brand name of Leqembi, is a humanized version of the mouse mAb158 monoclonal antibody targeting soluble Aβ oligomers with high affinity for which positive data have been shown in clinical trials (Magnusson et al., 2013). In addition, aducanumab was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2021, and lecanemab was recently approved by the FDA in January 2023. In addition to aducanumab and lecanemab, some other monoclonal antibodies, such as donanemab, are currently waiting for approval (Mintun et al., 2021; Rashad et al., 2022). Thus, immunotherapy might be one of the most topical ways to threat AD over a period of time.

On the other hand, until now, there have been no positive data shown in monoclonal antibody therapy for PD treatment through clinical trials (Saeed et al., 2020). For PD patients, medication is still the most commonly used treatment. Although first-line drugs such as levodopa can significantly improve the cardinal motor symptoms of PD, patients who are medication refractory might also need other alternative methods. Since the mid-1990s, a kind of invasive surgical method, deep brain stimulation, has been used for pharmacologically resistant patients (Limousin et al., 1995; Hacker et al., 2020) and can improve motor symptoms and the medication-related side effects of chronic dopamine replacement (Benabid et al., 1996; Weaver et al., 2009). Over the years, technical advances in deep brain stimulation have led to the adaptability, reversibility and feasibility of performing bilateral intervention, but high-risk complications, some specific contraindications of patients (such as elderly age and psychiatric disorders), surgical team experience and economic aspects have limited this implementation (Neumann et al., 2023). In addition, a noninvasive approach called magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound allows effective improvement of the cardinal motor features of PD patients with an acceptable profile of side effects (Martínez-Fernández et al., 2018). An approved neurosurgery by the FDA is Exablate Neuro, which uses a focused ultrasound device to target specific areas deep in the brain, so that the beams can disrupt targeted brain tissue to treat motor symptoms (Wang et al., 2022).

The high-resolution structures using electron cryo-microscopy and solid-state NMR spectroscopy have revealed that one pathogenic protein has the ability to form amyloid fibrils with different structures (different conformational strains) that is known as polymorphism. Studies using tau fibrils extracted from the brains of individuals with AD (Fitzpatrick et al., 2017; Falcon et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2021), and αSyn filaments derived from individuals with multiple system atrophy or DLB showed high structural polymorphisms (Schweighauser et al., 2020), suggesting that different conformational strains of amyloid fibrils induce different types of neurodegenerative disease (Li and Liu, 2022). These structural insights of pathogenic amyloid fibrils may provide diagnostic and potential therapeutic relevance, and help researchers perform structure-based development of drugs that prevent fibril formation.

Funding Statement

Funding: This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Nos. 2022GXNSFAA035622 (to MJ), 2020GXNSFAA297048 (to ZZ); the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 82060268 (to ZZ).

Footnotes

C-Editors: Zhao M, Liu WJ, Li CH; T-Editor: Jia Y

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Data availability statement: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Alim MA, Ma QL, Takeda K, Aizawa T, Matsubara M, Nakamura M, Asada A, Saito T, Kaji H, Yoshii M, Hisanaga S, Uéda K. Demonstration of a role for alpha-synuclein as a functional microtubule-associated protein. J Alzheimers Dis. 2004;6:435–449. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alonso AC, Zaidi T, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Role of abnormally phosphorylated tau in the breakdown of microtubules in Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:5562–5566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso A, Zaidi T, Novak M, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Hyperphosphorylation induces self-assembly of tau into tangles of paired helical filaments/straight filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6923–6928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121119298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson JP, Walker DE, Goldstein JM, de Laat R, Banducci K, Caccavello RJ, Barbour R, Huang J, Kling K, Lee M, Diep L, Keim PS, Shen X, Chataway T, Schlossmacher MG, Seubert P, Schenk D, Sinha S, Gai WP, Chilcote TJ. Phosphorylation of Ser-129 is the dominant pathological modification of alpha-synuclein in familial and sporadic Lewy body disease. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29739–29752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arima K, Mizutani T, Alim MA, Tonozuka-Uehara H, Izumiyama Y, Hirai S, Uéda K. NACP/alpha-synuclein and tau constitute two distinctive subsets of filaments in the same neuronal inclusions in brains from a family of parkinsonism and dementia with Lewy bodies: double-immunolabeling fluorescence and electron microscopic studies. Acta Neuropathol. 2000;100:115–121. doi: 10.1007/s004010050002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Askanas V, Engel WK, Alvarez RB, McFerrin J, Broccolini A. Novel immunolocalization of alpha-synuclein in human muscle of inclusion-body myositis, regenerating and necrotic muscle fibers and at neuromuscular junctions. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:592–598. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.7.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baas PW, Qiang L. Tau: It's Not What You Think. Trends Cell Biol. 2019;29:452–461. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bachhuber T, Katzmarski N, McCarter JF, Loreth D, Tahirovic S, Kamp F, Abou-Ajram C, Nuscher B, Serrano-Pozo A, Müller A, Prinz M, Steiner H, Hyman BT, Haass C, Meyer-Luehmann M. Inhibition of amyloid-βplaque formation by α-synuclein. Nat Med. 2015;21:802–807. doi: 10.1038/nm.3885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Badiola N, de Oliveira RM, Herrera F, Guardia-Laguarta C, Gonçalves SA, Pera M, Suárez-Calvet M, Clarimon J, Outeiro TF, Lleó A. Tau enhances α-synuclein aggregation and toxicity in cellular models of synucleinopathy. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbour R, Kling K, Anderson JP, Banducci K, Cole T, Diep L, Fox M, Goldstein JM, Soriano F, Seubert P, Chilcote TJ. Red blood cells are the major source of alpha-synuclein in blood. Neurodegener Dis. 2008;5:55–59. doi: 10.1159/000112832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartels T, Choi JG, Selkoe DJ. α-Synuclein occurs physiologically as a helically folded tetramer that resists aggregation. Nature. 2011;477:107–110. doi: 10.1038/nature10324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benabid AL, Pollak P, Gao D, Hoffmann D, Limousin P, Gay E, Payen I, Benazzouz A. Chronic electrical stimulation of the ventralis intermedius nucleus of the thalamus as a treatment of movement disorders. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:203–214. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.84.2.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bengoa-Vergniory N, Roberts RF, Wade-Martins R, Alegre-Abarrategui J. Alpha-synuclein oligomers: a new hope. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134:819–838. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1755-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benhelli-Mokrani H, Mansuroglu Z, Chauderlier A, Albaud B, Gentien D, Sommer S, Schirmer C, Laqueuvre L, Josse T, Buée L, Lefebvre B, Galas MC, Souès S, Bonnefoy E. Genome-wide identification of genic and intergenic neuronal DNA regions bound by Tau protein under physiological and stress conditions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:11405–11422. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buck K, Landeck N, Ulusoy A, Majbour NK, El-Agnaf OM, Kirik D. Ser129 phosphorylation of endogenous α-synuclein induced by overexpression of polo-like kinases 2 and 3 in nigral dopamine neurons is not detrimental to their survival and function. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;78:100–114. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burré J, Sharma M, Tsetsenis T, Buchman V, Etherton MR, Südhof TC. Alpha-synuclein promotes SNARE-complex assembly in vivo and in vitro. Science. 2010;329:1663–1667. doi: 10.1126/science.1195227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calogero AM, Mazzetti S, Pezzoli G, Cappelletti G. Neuronal microtubules and proteins linked to Parkinson's disease: a relevant interaction? Biol Chem. 2019;400:1099–1112. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2019-0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cartelli D, Aliverti A, Barbiroli A, Santambrogio C, Ragg EM, Casagrande FV, Cantele F, Beltramone S, Marangon J, De Gregorio C, Pandini V, Emanuele M, Chieregatti E, Pieraccini S, Holmqvist S, Bubacco L, Roybon L, Pezzoli G, Grandori R, Arnal I, et al. α-Synuclein is a novel microtubule dynamase. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33289. doi: 10.1038/srep33289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chartier-Harlin MC, Kachergus J, Roumier C, Mouroux V, Douay X, Lincoln S, Levecque C, Larvor L, Andrieux J, Hulihan M, Waucquier N, Defebvre L, Amouyel P, Farrer M, Destée A. Alpha-synuclein locus duplication as a cause of familial Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2004;364:1167–1169. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen S, Townsend K, Goldberg TE, Davies P, Conejero-Goldberg C. MAPT isoforms: differential transcriptional profiles related to 3R and 4R splice variants. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22:1313–1329. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clavaguera F, Bolmont T, Crowther RA, Abramowski D, Frank S, Probst A, Fraser G, Stalder AK, Beibel M, Staufenbiel M, Jucker M, Goedert M, Tolnay M. Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic mouse brain. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:909–913. doi: 10.1038/ncb1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cleveland DW, Hwo SY, Kirschner MW. Purification of tau, a microtubule-associated protein that induces assembly of microtubules from purified tubulin. J Mol Biol. 1977;116:207–225. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen TJ, Guo JL, Hurtado DE, Kwong LK, Mills IP, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. The acetylation of tau inhibits its function and promotes pathological tau aggregation. Nat Commun. 2011;2:252. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colom-Cadena M, Gelpi E, Charif S, Belbin O, Blesa R, Martí MJ, Clarimón J, Lleó A. Confluence of α-synuclein, tau and β-amyloid pathologies in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72:1203–1212. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cummings JL, Cohen S, van Dyck CH, Brody M, Curtis C, Cho W, Ward M, Friesenhahn M, Rabe C, Brunstein F, Quartino A, Honigberg LA, Fuji RN, Clayton D, Mortensen D, Ho C, Paul R. ABBY: A phase 2 randomized trial of crenezumab in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2018;90:ne1889–1897. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Damianich A, Facal CL, Muñiz JA, Mininni C, Soiza-Reilly M, Ponce De León M, Urrutia L, Falasco G, Ferrario JE, Avale ME. Tau mis-splicing correlates with motor impairments and striatal dysfunction in a model of tauopathy. Brain. 2021;144:2302–2309. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dehmelt L, Halpain S. The MAP2/Tau family of microtubule-associated proteins. Genome Biol. 2005;6:204. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-6-1-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desplats P, Spencer B, Crews L, Pathel P, Morvinski-Friedmann D, Kosberg K, Roberts S, Patrick C, Winner B, Winkler J, Masliah E. α-Synuclein induces alterations in adult neurogenesis in Parkinson disease models via p53-mediated repression of Notch1. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:31691–31702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.354522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diógenes MJ, Dias RB, Rombo DM, Vicente Miranda H, Maiolino F, Guerreiro P, Näsström T, Franquelim HG, Oliveira LM, Castanho MA, Lannfelt L, Bergström J, Ingelsson M, Quintas A, Sebastião AM, Lopes LV, Outeiro TF. Extracellular alpha-synuclein oligomers modulate synaptic transmission and impair LTP via NMDA-receptor activation. J Neurosci. 2012;32:11750–11762. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0234-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dregni AJ, Duan P, Xu H, Changolkar L, El Mammeri N, Lee VM, Hong M. Fluent molecular mixing of Tau isoforms in Alzheimer's disease neurofibrillary tangles. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2967. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30585-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DuBoff B, Götz J, Feany MB. Tau promotes neurodegeneration via DRP1 mislocalization in vivo. Neuron. 2012;75:618–632. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durante V, de Iure A, Loffredo V, Vaikath N, De Risi M, Paciotti S, Quiroga-Varela A, Chiasserini D, Mellone M, Mazzocchetti P, Calabrese V, Campanelli F, Mechelli A, Di Filippo M, Ghiglieri V, Picconi B, El-Agnaf OM, De Leonibus E, Gardoni F, Tozzi A, et al. Alpha-synuclein targets GluN2A NMDA receptor subunit causing striatal synaptic dysfunction and visuospatial memory alteration. Brain. 2019;142:1365–1385. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Espíndola SL, Damianich A, Alvarez RJ, Sartor M, Belforte JE, Ferrario JE, Gallo JM, Avale ME. Modulation of Tau isoforms imbalance precludes Tau pathology and cognitive decline in a mouse model of tauopathy. Cell Rep. 2018;23:709–715. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falcon B, Zhang W, Schweighauser M, Murzin AG, Vidal R, Garringer HJ, Ghetti B, Scheres SHW, Goedert M. Tau filaments from multiple cases of sporadic and inherited Alzheimer's disease adopt a common fold. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136:699–708. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1914-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fallet-Bianco C, Loeuillet L, Poirier K, Loget P, Chapon F, Pasquier L, Saillour Y, Beldjord C, Chelly J, Francis F. Neuropathological phenotype of a distinct form of lissencephaly associated with mutations in TUBA1A. Brain. 2008;131:2304–2320. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Felgner H, Frank R, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E, Ludin B, Matus A, Schliwa M. Domains of neuronal microtubule-associated proteins and flexural rigidity of microtubules. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:1067–1075. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.5.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferrer I, López-González I, Carmona M, Arregui L, Dalfó E, Torrejón-Escribano B, Diehl R, Kovacs GG. Glial and neuronal tau pathology in tauopathies: characterization of disease-specific phenotypes and tau pathology progression. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2014;73:81–97. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feuillette S, Miguel L, Frébourg T, Campion D, Lecourtois M. Drosophila models of human tauopathies indicate that Tau protein toxicity in vivo is mediated by soluble cytosolic phosphorylated forms of the protein. J Neurochem. 2010;113:895–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fîlfan M, Sandu RE, Zăvăleanu AD, GreşiŢă A, Glăvan DG, Olaru DG, Popa-Wagner A. Autophagy in aging and disease. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2017;58:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fitzpatrick AWP, Falcon B, He S, Murzin AG, Murshudov G, Garringer HJ, Crowther RA, Ghetti B, Goedert M, Scheres SHW. Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments from Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2017;547:185–190. doi: 10.1038/nature23002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fouke KE, Wegman ME, Weber SA, Brady EB, Román-Vendrell C, Morgan JR. Synuclein regulates synaptic vesicle clustering and docking at a vertebrate synapse. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:774650. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.774650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujiwara H, Hasegawa M, Dohmae N, Kawashima A, Masliah E, Goldberg MS, Shen J, Takio K, Iwatsubo T. alpha-Synuclein is phosphorylated in synucleinopathy lesions. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:160–164. doi: 10.1038/ncb748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fulga TA, Elson-Schwab I, Khurana V, Steinhilb ML, Spires TL, Hyman BT, Feany MB. Abnormal bundling and accumulation of F-actin mediates tau-induced neuronal degeneration in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:139–148. doi: 10.1038/ncb1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fusco G, De Simone A, Gopinath T, Vostrikov V, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM, Veglia G. Direct observation of the three regions in α-synuclein that determine its membrane-bound behaviour. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3827. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gai WP, Power JH, Blumbergs PC, Blessing WW. Multiple-system atrophy: a new alpha-synuclein disease? Lancet. 1998;352:547–548. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)79256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaig C, Martí MJ, Ezquerra M, Cardozo A, Rey MJ, Tolosa E. G2019S LRRK2 mutation causing Parkinson's disease without Lewy bodies. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009 doi: 10.1136/bcr.08.2008.0632. bcr08.2008.0632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gamache J, Benzow K, Forster C, Kemper L, Hlynialuk C, Furrow E, Ashe KH, Koob MD. Factors other than hTau overexpression that contribute to tauopathy-like phenotype in rTg4510 mice. Nat Commun. 2019;10:2479. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10428-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gamache JE, Kemper L, Steuer E, Leinonen-Wright K, Choquette JM, Hlynialuk C, Benzow K, Vossel KA, Xia W, Koob MD, Ashe KH. Developmental pathogenicity of 4-repeat human tau is lost with the P301L mutation in genetically matched tau-transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2020;40:220–236. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1256-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghetti B, Oblak AL, Boeve BF, Johnson KA, Dickerson BC, Goedert M. Invited review: Frontotemporal dementia caused by microtubule-associated protein tau gene (MAPT) mutations: a chameleon for neuropathology and neuroimaging. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2015;41:24–46. doi: 10.1111/nan.12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giasson BI, Forman MS, Higuchi M, Golbe LI, Graves CL, Kotzbauer PT, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Initiation and synergistic fibrillization of tau and alpha-synuclein. Science. 2003;300:636–640. doi: 10.1126/science.1082324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goedert M, Wischik CM, Crowther RA, Walker JE, Klug A. Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA encoding a core protein of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease: identification as the microtubule-associated protein tau. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:4051–4055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goedert M, Jakes R. Expression of separate isoforms of human tau protein: correlation with the tau pattern in brain and effects on tubulin polymerization. EMBO J. 1990;9:4225–4230. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07870.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:492–501. doi: 10.1038/35081564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goedert M. Neurodegeneration, Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases: The prion concept in relation to assembled Aβ, tau, and α-synuclein. Science. 2015;349:1255555. doi: 10.1126/science.1255555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goedert M, Masuda-Suzukake M, Falcon B. Like prions: the propagation of aggregated tau and α-synuclein in neurodegeneration. Brain. 2017;140:266–278. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guo JL, Covell DJ, Daniels JP, Iba M, Stieber A, Zhang B, Riddle DM, Kwong LK, Xu Y, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Distinct α-synuclein strains differentially promote tau inclusions in neurons. Cell. 2013;154:103–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo JL, Lee VM. Cell-to-cell transmission of pathogenic proteins in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Med. 2014;20:130–138. doi: 10.1038/nm.3457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo T, Noble W, Hanger DP. Roles of tau protein in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;133:665–704. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1707-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hacker ML, Turchan M, Heusinkveld LE, Currie AD, Millan SH, Molinari AL, Konrad PE, Davis TL, Phibbs FT, Hedera P, Cannard KR, Wang L, Charles D. Deep brain stimulation in early-stage Parkinson disease: Five-year outcomes. Neurology. 2020;95:e393–401. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harada A, Oguchi K, Okabe S, Kuno J, Terada S, Ohshima T, Sato-Yoshitake R, Takei Y, Noda T, Hirokawa N. Altered microtubule organization in small-calibre axons of mice lacking tau protein. Nature. 1994;369:488–491. doi: 10.1038/369488a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hasegawa M, Smith MJ, Goedert M. Tau proteins with FTDP-17 mutations have a reduced ability to promote microtubule assembly. FEBS Lett. 1998;437:207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.He Z, McBride JD, Xu H, Changolkar L, Kim SJ, Zhang B, Narasimhan S, Gibbons GS, Guo JL, Kozak M, Schellenberg GD, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Transmission of tauopathy strains is independent of their isoform composition. Nat Commun. 2020;11:7. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13787-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hong M, Zhukareva V, Vogelsberg-Ragaglia V, Wszolek Z, Reed L, Miller BI, Geschwind DH, Bird TD, McKeel D, Goate A, Morris JC, Wilhelmsen KC, Schellenberg GD, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Mutation-specific functional impairments in distinct tau isoforms of hereditary FTDP-17. Science. 1998;282:1914–1917. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Honig LS, Vellas B, Woodward M, Boada M, Bullock R, Borrie M, Hager K, Andreasen N, Scarpini E, Liu-Seifert H, Case M, Dean RA, Hake A, Sundell K, Poole Hoffmann V, Carlson C, Khanna R, Mintun M, DeMattos R, Selzler KJ, et al. Trial of solanezumab for mild dementia due to Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:321–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Carrillo MC, Dickson DW, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Mirra SS, Nelson PT, Schneider JA, Thal DR, Thies B, Trojanowski JQ, Vinters HV, Montine TJ. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Irizarry MC, Growdon W, Gomez-Isla T, Newell K, George JM, Clayton DF, Hyman BT. Nigral and cortical Lewy bodies and dystrophic nigral neurites in Parkinson's disease and cortical Lewy body disease contain alpha-synuclein immunoreactivity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:334–337. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199804000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Irwin DJ, Grossman M, Weintraub D, Hurtig HI, Duda JE, Xie SX, Lee EB, Van Deerlin VM, Lopez OL, Kofler JK, Nelson PT, Jicha GA, Woltjer R, Quinn JF, Kaye J, Leverenz JB, Tsuang D, Longfellow K, Yearout D, Kukull W, et al. Neuropathological and genetic correlates of survival and dementia onset in synucleinopathies: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:55–65. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30291-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ishizawa T, Mattila P, Davies P, Wang D, Dickson DW. Colocalization of tau and alpha-synuclein epitopes in Lewy bodies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:389–397. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ittner LM, Ke YD, Delerue F, Bi M, Gladbach A, van Eersel J, Wölfing H, Chieng BC, Christie MJ, Napier IA, Eckert A, Staufenbiel M, Hardeman E, Götz J. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-beta toxicity in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Cell. 2010;142:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jakes R, Spillantini MG, Goedert M. Identification of two distinct synucleins from human brain. FEBS Lett. 1994;345:27–32. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00395-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jao CC, Hegde BG, Chen J, Haworth IS, Langen R. Structure of membrane-bound alpha-synuclein from site-directed spin labeling and computational refinement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19666–19671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807826105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jensen PH, Sørensen ES, Petersen TE, Gliemann J, Rasmussen LK. Residues in the synuclein consensus motif of the alpha-synuclein fragment. NAC participate in transglutaminase-catalysed cross-linking to Alzheimer-disease amyloid beta A4 peptide. Biochem J. 1995;310:91–94. doi: 10.1042/bj3100091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jensen PH, Hojrup P, Hager H, Nielsen MS, Jacobsen L, Olesen OF, Gliemann J, Jakes R. Binding of Abeta to alpha- and beta-synucleins: identification of segments in alpha-synuclein/NAC precursor that bind Abeta and NAC. Biochem J. 1997;323:539–546. doi: 10.1042/bj3230539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jensen PH, Hager H, Nielsen MS, Hojrup P, Gliemann J, Jakes R. alpha-synuclein binds to Tau and stimulates the protein kinase A-catalyzed tau phosphorylation of serine residues 262 and 356. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25481–25489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jin M, Pomp O, Shinoda T, Toba S, Torisawa T, Furuta K, Oiwa K, Yasunaga T, Kitagawa D, Matsumura S, Miyata T, Tan TT, Reversade B, Hirotsune S. Katanin p80, NuMA and cytoplasmic dynein cooperate to control microtubule dynamics. Sci Rep. 2017;7:39902. doi: 10.1038/srep39902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jin M, Matsumoto S, Ayaki T, Yamakado H, Taguchi T, Togawa N, Konno A, Hirai H, Nakajima H, Komai S, Ishida R, Chiba S, Takahashi R, Takao T, Hirotsune S. DOPAnization of tyrosine in α-synuclein by tyrosine hydroxylase leads to the formation of oligomers. Nat Commun. 2022;13:6880. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34555-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kahle PJ, Neumann M, Ozmen L, Muller V, Jacobsen H, Schindzielorz A, Okochi M, Leimer U, van Der Putten H, Probst A, Kremmer E, Kretzschmar HA, Haass C. Subcellular localization of wild-type and Parkinson's disease-associated mutant alpha -synuclein in human and transgenic mouse brain. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6365–6373. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06365.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kaufman SK, Sanders DW, Thomas TL, Ruchinskas AJ, Vaquer-Alicea J, Sharma AM, Miller TM, Diamond MI. Tau prion strains dictate patterns of cell pathology, progression, rate and regional vulnerability in vivo. Neuron. 2016;92:796–812. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kayed R, Dettmer U, Lesné SE. Soluble endogenous oligomeric α-synuclein species in neurodegenerative diseases: Expression, spreading and cross-talk. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10:791–818. doi: 10.3233/JPD-201965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ke YD, Suchowerska AK, van der Hoven J, De Silva DM, Wu CW, van Eersel J, Ittner A, Ittner LM. Lessons from tau-deficient mice. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:873270. doi: 10.1155/2012/873270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kellogg EH, Hejab NMA, Poepsel S, Downing KH, DiMaio F, Nogales E. Near-atomic model of microtubule-tau interactions. Science. 2018;360:1242–1246. doi: 10.1126/science.aat1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Salviati A, Floriach-Robert M, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, Smith GE, Dickson DW, Johnson KA, Petersen LE, McDonald WC, Braak H, Petersen RC. Neuropathology of cognitively normal elderly. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:1087–1095. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.11.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kok FK, van Leerdam SL, de Lange ECM. Potential mechanisms underlying resistance to dementia in non-demented individuals with Alzheimer's disease neuropathology. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;87:51–81. doi: 10.3233/JAD-210607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kordower JH, Chu Y, Hauser RA, Freeman TB, Olanow CW. Lewy body-like pathology in long-term embryonic nigral transplants in Parkinson's disease. Nat Med. 2008;14:504–506. doi: 10.1038/nm1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee G, Cowan N, Kirschner M. The primary structure and heterogeneity of tau protein from mouse brain. Science. 1988;239:285–288. doi: 10.1126/science.3122323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lee VM, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1121–1159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li D, Liu C. Conformational strains of pathogenic amyloid proteins in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2022;23:523–534. doi: 10.1038/s41583-022-00603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li JY, Englund E, Holton JL, Soulet D, Hagell P, Lees AJ, Lashley T, Quinn NP, Rehncrona S, Björklund A, Widner H, Revesz T, Lindvall O, Brundin P. Lewy bodies in grafted neurons in subjects with Parkinson's disease suggest host-to-graft disease propagation. Nat Med. 2008;14:501–503. doi: 10.1038/nm1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li X, James S, Lei P. Interactions between α-synuclein and tau protein: implications to neurodegenerative disorders. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;60:298–304. doi: 10.1007/s12031-016-0829-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li Y, Zhao C, Luo F, Liu Z, Gui X, Luo Z, Zhang X, Li D, Liu C, Li X. Amyloid fibril structure of α-synuclein determined by cryo-electron microscopy. Cell Res. 2018;28:897–903. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0075-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Limousin P, Pollak P, Benazzouz A, Hoffmann D, Le Bas JF, Broussolle E, Perret JE, Benabid AL. Effect of parkinsonian signs and symptoms of bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation. Lancet. 1995;345:91–95. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Logan T, Bendor J, Toupin C, Thorn K, Edwards RH. α-Synuclein promotes dilation of the exocytotic fusion pore. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:681–689. doi: 10.1038/nn.4529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.LoPresti P, Szuchet S, Papasozomenos SC, Zinkowski RP, Binder LI. Functional implications for the microtubule-associated protein tau: localization in oligodendrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10369–10373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lu J, Zhang S, Ma X, Jia C, Liu Z, Huang C, Liu C, Li D. Structural basis of the interplay between α-synuclein and Tau in regulating pathological amyloid aggregation. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:7470–7480. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.012284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Magnusson K, Sehlin D, Syvänen S, Svedberg MM, Philipson O, Söderberg L, Tegerstedt K, Holmquist M, Gellerfors P, Tolmachev V, Antoni G, Lannfelt L, Hall H, Nilsson LN. Specific uptake of an amyloid-βprotofibril-binding antibody-tracer in AβPP transgenic mouse brain. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;37:29–40. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Maiti P, Manna J, Dunbar GL. Current understanding of the molecular mechanisms in Parkinson's disease: Targets for potential treatments. Transl Neurodegener. 2017;6:28. doi: 10.1186/s40035-017-0099-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Majounie E, Cross W, Newsway V, Dillman A, Vandrovcova J, Morris CM, Nalls MA, Ferrucci L, Owen MJ, O'Donovan MC, Cookson MR, Singleton AB, de Silva R, Morris HR. Variation in tau isoform expression in different brain regions and disease states. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:1922.e7–1922.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Markesbery WR, Jicha GA, Liu H, Schmitt FA. Lewy body pathology in normal elderly subjects. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68:816–822. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181ac10a7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Maroteaux L, Campanelli JT, Scheller RH. Synuclein: a neuron-specific protein localized to the nucleus and presynaptic nerve terminal. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2804–2815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-02804.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maroteaux L, Scheller RH. The rat brain synucleins;family of proteins transiently associated with neuronal membrane. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1991;11:335–343. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(91)90043-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Martínez-Fernández R, Rodríguez-Rojas R, Del Álamo M, Hernández-Fernández F, Pineda-Pardo JA, Dileone M, Alonso-Frech F, Foffani G, Obeso I, Gasca-Salas C, de Luis-Pastor E, Vela L, Obeso JA. Focused ultrasound subthalamotomy in patients with asymmetric Parkinson's disease: a pilot study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:54–63. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.McLean PJ, Ribich S, Hyman BT. Subcellular localization of alpha-synuclein in primary neuronal cultures: effect of missense mutations. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2000:53–63. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6284-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Merino-Serrais P, Benavides-Piccione R, Blazquez-Llorca L, Kastanauskaite A, Rábano A, Avila J, DeFelipe J. The influence of phospho-τon dendritic spines of cortical pyramidal neurons in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2013;136:1913–1928. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Michalicova A, Majerova P, Kovac A. Tau protein and its role in blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Front Mol Neurosci. 2020;13:570045. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2020.570045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mietelska-Porowska A, Wasik U, Goras M, Filipek A, Niewiadomska G. Tau protein modifications and interactions: their role in function and dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:4671–4713. doi: 10.3390/ijms15034671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mintun MA, Lo AC, Duggan Evans C, Wessels AM, Ardayfio PA, Andersen SW, Shcherbinin S, Sparks J, Sims JR, Brys M, Apostolova LG, Salloway SP, Skovronsky DM. Donanemab in Early Alzheimer's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1691–1704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mocanu MM, Nissen A, Eckermann K, Khlistunova I, Biernat J, Drexler D, Petrova O, Schönig K, Bujard H, Mandelkow E, Zhou L, Rune G, Mandelkow EM. The potential for beta-structure in the repeat domain of tau protein determines aggregation, synaptic, decay neuronal loss and coassembly with endogenous Tau in inducible mouse models of tauopathy. J Neurosci. 2008;28:737–748. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2824-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Morris M, Maeda S, Vossel K, Mucke L. The many faces of tau. Neuron. 2011;70:410–426. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Moussaud S, Jones DR, Moussaud-Lamodière EL, Delenclos M, Ross OA, McLean PJ. Alpha-synuclein and tau: teammates in neurodegeneration? Mol Neurodegener. 2014;9:43. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mukrasch MD, Bibow S, Korukottu J, Jeganathan S, Biernat J, Griesinger C, Mandelkow E, Zweckstetter M. Structural polymorphism of 441-residue tau at single residue resolution. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e34. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nemani VM, Lu W, Berge V, Nakamura K, Onoa B, Lee MK, Chaudhry FA, Nicoll RA, Edwards RH. Increased expression of alpha-synuclein reduces neurotransmitter release by inhibiting synaptic vesicle reclustering after endocytosis. Neuron. 2010;65:66–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Neumann WJ, Horn A, Kühn AA. Insights and opportunities for deep brain stimulation as a brain circuit intervention. Trends Neurosci. 2023;46:472–487. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2023.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Niblock M, Gallo JM. Tau alternative splicing in familial and sporadic tauopathies. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40:677–680. doi: 10.1042/BST20120091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nonaka T, Watanabe ST, Iwatsubo T, Hasegawa M. Seeded aggregation and toxicity of {alpha}-synuclein and tau: cellular models of neurodegenerative diseases. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:34885–34898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.148460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Olichney JM, Galasko D, Salmon DP, Hofstetter CR, Hansen LA, Katzman R, Thal LJ. Cognitive decline is faster in Lewy body variant than in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1998;51:351–357. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ordonez DG, Lee MK, Feany MB. α-synuclein induces mitochondrial dysfunction through spectrin and the actin cytoskeleton. Neuron. 2018;97:108–124.e106. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Oueslati A, Paleologou KE, Schneider BL, Aebischer P, Lashuel HA. Mimicking phosphorylation at serine 87 inhibits the aggregation of human α-synuclein and protects against its toxicity in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci. 2012;32:1536–1544. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3784-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Paleologou KE, Kragh CL, Mann DM, Salem SA, Al-Shami R, Allsop D, Hassan AH, Jensen PH, El-Agnaf OM. Detection of elevated levels of soluble alpha-synuclein oligomers in post-mortem brain extracts from patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain. 2009;132:1093–1101. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Paleologou KE, Oueslati A, Shakked G, Rospigliosi CC, Kim HY, Lamberto GR, Fernandez CO, Schmid A, Chegini F, Gai WP, Chiappe D, Moniatte M, Schneider BL, Aebischer P, Eliezer D, Zweckstetter M, Masliah E, Lashuel HA. Phosphorylation at S87 is enhanced in synucleinopathies, inhibits alpha-synuclein oligomerization, and influences synuclein-membrane interactions. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3184–3198. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5922-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Paleologou KE, Schmid AW, Rospigliosi CC, Kim HY, Lamberto GR, Fredenburg RA, Lansbury PT, Jr, Fernandez CO, Eliezer D, Zweckstetter M, Lashuel HA. Phosphorylation at Ser-129 but not the phosphomimics S129E/D inhibits the fibrillation of alpha-synuclein. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16895–16905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800747200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Pan L, Meng L, He M, Zhang Z. Tau in the pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2021;71:2179–2191. doi: 10.1007/s12031-020-01776-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Pan L, Li C, Meng L, Tian Y, He M, Yuan X, Zhang G, Zhang Z, Xiong J, Chen G, Zhang Z. Tau accelerates α-synuclein aggregation and spreading in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2022;145:3454–3471. doi: 10.1093/brain/awac171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Poorkaj P, Bird TD, Wijsman E, Nemens E, Garruto RM, Anderson L, Andreadis A, Wiederholt WC, Raskind M, Schellenberg GD. Tau is a candidate gene for chromosome 17 frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:815–825. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]