Abstract

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third-leading cause of death globally and is responsible for over 3 million deaths annually. One of the factors contributing to the significant healthcare burden for these patients is readmission. The aim of this review is to describe significant predictors and prediction scores for all-cause and COPD-related readmission among patients with COPD.

Methods

A search was conducted in Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, from database inception to June 7, 2022. Studies were included if they reported on patients at least 40 years old with COPD, readmission data within 1 year, and predictors of readmission. Study quality was assessed. Significant predictors of readmission and the degree of significance, as noted by the p-value, were extracted for each study. This review was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022337035).

Results

In total, 242 articles reporting on 16,471,096 patients were included. There was a low risk of bias across the literature. Of these, 153 studies were observational, reporting on predictors; 57 studies were observational studies reporting on interventions; and 32 were randomized controlled trials of interventions. Sixty-four significant predictors for all-cause readmission and 23 for COPD-related readmission were reported across the literature. Significant predictors included 1) pre-admission patient characteristics, such as male sex, prior hospitalization, poor performance status, number and type of comorbidities, and use of long-term oxygen; 2) hospitalization details, such as length of stay, use of corticosteroids, and use of ventilatory support; 3) results of investigations, including anemia, lower FEV1, and higher eosinophil count; and 4) discharge characteristics, including use of home oxygen and discharge to long-term care or a skilled nursing facility.

Conclusion

The findings from this review may enable better predictive modeling and can be used by clinicians to better inform their clinical gestalt of readmission risk.

Keywords: predictors, readmission, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common respiratory condition characterized by persistent airflow limitation1 and is thought to affect over 10% of the population.2 As a consequence of its chronicity, COPD is responsible for over 3 million deaths globally, making it the third most common cause of death.3

Patients with COPD commonly require hospitalized care, and COPD is one of the most common causes of hospitalization, among chronic diseases.4 Moreover, a notable proportion of patients with COPD will be readmitted, making readmission one of the factors contributing to the significant healthcare burden for these patients. It has been estimated that up to 50% of patients diagnosed with COPD are readmitted within 30 days of initial discharge in the USA.5 In addition to the utilization of healthcare resources, readmission is associated with a worse overall prognosis.6 Over the past decade, there has been an increased interest in identifying predictors and predictive models for readmission.7 Several systematic reviews have attempted to summarize the literature, but they only focused on all-cause or COPD-related readmission alone, and/or did not undertake a quality assessment of the included studies.8–10 In addition, given the rapidly developing literature, with many studies being reported in the past few years, these systematic reviews may not account for current findings.

The aim of this systematic review is to describe significant predictors and prediction scores for all-cause and COPD-related readmission among patients with COPD.

Methods

This review was registered a priori on PROSPERO (CRD42022337035) and reported as per the PRISMA statement.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was developed for Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from database inception to June 7, 2022, using a combination of database-specific subject headings and text words for the main concepts of COPD and hospital readmissions. An expanded search filter for clinical prediction guides was used. Results were limited to adult human studies. No other limits were applied (Appendix 1).

Eligibility Criteria

Two review authors (RC, OWS) independently screened articles for their eligibility for inclusion. A calibration exercise of 20 articles was undertaken to ensure concordance between reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus. If consensus could not be achieved, a third review author (RW) participated in the discussion to resolve discrepancies.

Articles were eligible after level 1 title and abstract screening, if they reported on primary research articles reporting on patients with COPD and readmission. Secondary research articles, such as review articles and economic analyses, as well as editorials/commentaries, were excluded at this stage. Studies included after level 2 full-text screening eligibility criteria required studies to report on patients at least 40 years old with COPD, readmission data within 1 year of a COPD hospitalization, and predictors of readmission. Studies including patients admitted for reasons unrelated to acute exacerbations of COPD (eg pneumonia, acute hypercapnic respiratory failure, obstructive sleep apnea, lung cancer, anxiety/depression) and studies reporting on home care/telemonitoring were excluded at this stage, to limit included articles to only patients with COPD.

Data Extraction

Two of the three review authors (RC, OWS, JHBI) conducted data extraction. As with screening, discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus, with or without the input of a third reviewer (RW). Study characteristics of country, sample size, age of participants, and percentage of females enrolled in study were noted. Studies were classified as either assessing predictors or assessing interventions. Studies assessing interventions were further subclassified as either observational cohort studies or randomized controlled trials. Significant predictors of readmission and the degree of significance, as noted by the p-value, were extracted for each study. For studies that did not report p-values, p-values were calculated based on the provided statistics (eg odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals) where possible.

Study Quality

Study quality was assessed for each study. For randomized controlled trials, the risk of bias version 2 tool was used.11 For observational studies reporting on interventions, the ROBINS-I tool was used.12 For observational studies reporting on predictors, the ROBINS-E tool was used.13

Synthesis

Significant predictors were reported by the time of readmission post-discharge and the degree of significance. Predictors were reported as significant predictors for the timepoint of 1-month readmission, the interval of 2–3-month readmission, and the interval of 6–12-month readmission. Predictors were further reported based on whether they were significant at a type I error of 0.05, type I error of 0.01, or no degree of significance available. Significant predictors, as reported by the authors (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), were grouped together into similarly reported predictors across the literature (eg all mentions of hospital length of stay were grouped together).

Because of the non-uniform reporting of non-significant predictors, where some studies explicitly reported non-significant predictors in the methods/results and others only mentioned significant predictors, non-significant predictors were not presented.

Results

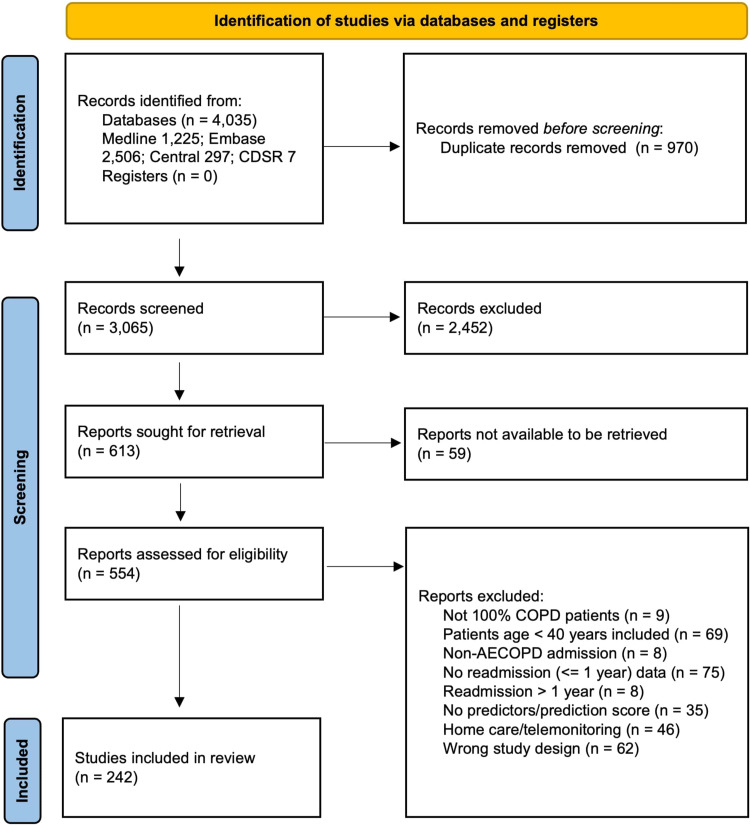

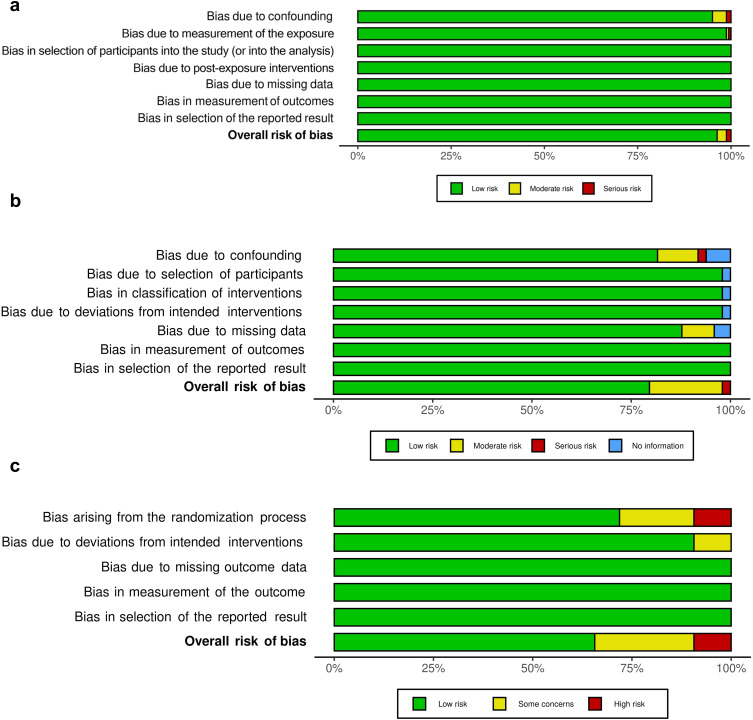

In total, 4035 articles were identified from the database search. After 970 duplicates were removed, 3065 records were screened. Ultimately, 242 articles14–255 reporting on 16,471,096 patients were included in this review (Figure 1). Across the literature, there was generally a low risk of bias (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Figure 2.

Quality assessment: (a) studies assessing predictors (ROBINS-E); (b) cohort studies assessing interventions (ROBINS-I); (c) randomized controlled trials assessing interventions (RoB 2).

Overall, 153 studies were observational studies reporting on predictors; 57 studies were observational studies reporting on interventions; and 32 were randomized controlled trials of interventions. The studies were published between 1997 and 2022, with over half of the studies published since 2017. Over one-third of articles (91 studies, 37.6%) originated from the USA; 31 (12.8%) studies originated from Spain, 14 (5.8%) from Canada, 13 (5.4%) from the UK, and 13 (5.4%) from China. Sample sizes ranged from 8 to 4,587,542. The mean/median age was greater than 60 years for nearly all studies. The percentage of females in a study ranged from 0.0% to 80.0%. Individual study characteristics are reported in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Studies Assessing Predictors

| Study | Country | n | Age (years) | % Female | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | ||||

| Abrams 201114 | USA | 28,156 | 69.1±10.6 | 3.1% | |

| Abusaada 201715 | USA | 1419 | 65.1±2.3 | 47.7% | |

| Agarwal 201618 | USA | 7257 | 75–84 | 64.2% | |

| Aksoy 201819 | Turkey | 2727 | 69.8±10.2 | 31.5% | |

| Al Aqqad 201720 | Malaysia | 81 | 72.0 (66.4–78.0) | 2.5% | |

| Almagro 200621 | Spain | 129 | 72.0±9.2 | 7.0% | |

| Almagro 201222 | Spain | 606 | 72.6±9.9 | 2.0% | |

| Almagro 201423 | Spain | 983 | 72.3±9.7 | 8.5% | |

| Alpaydin 202124 | Turkey | 300 | 73.1±10.1 | 28.3% | |

| Alqahtani 202125 | UK | 82 | 71.0±10.4 | 51.2% | |

| Bade 201929 | USA | 48,888 | 68.7±10.1 | 3.7% | |

| Bahadori 200930 | Canada | 310 | 74.0±12.0 | 46.5% | |

| Baker 201331 | USA | 6095 | 55–59 | 58.9% | |

| Barba 201233 | Spain | 275,512 | 72.0±15.4 | 30.0% | |

| Bartels 201834 | Canada | 511 | 66.5±13.3 | 35.2% | |

| Belanger 201836 | Canada | 479 | 68.9±9.4 | 48.0% | |

| Bernabeu-Mora 201738 | Spain | 103 | 71.0±9.1 | 6.8% | |

| Bishwakarma 201740 | USA | 6066 | 76.9±7.2 | 67.3% | |

| Boeck 201441 | Switzerland | 43 | Not reported | 53.5% | |

| Boixeda 201742 | Spain | 120 | 72.9±8.6 | 2.5% | |

| Bollu 201343 | USA | 2463 | 68.6±10.6 | 57.2% | |

| Bollu 201744 | USA | 13,675 | 67.1±12.4 | 55.6% | |

| Breyer-Kohansal 201945 | Austria | 823 | 68.5±10.2 | 40.9% | |

| Brownridge 201746 | Australia | 130 | 72.9±10.7 | 51.6% | |

| Buhr 201949 | USA | 1,622,983 | 68.0±11.9 | 58.9% | |

| Buhr 202048 | USA | 1,622,983 | 68.0±11.9 | 57.8% | |

| Candrilli 201550 | USA | 264,526 | 67.6±11.2 | 50.9% | |

| Carneiro 201051 | Portugal | 45 | 68±12.4 | 15.6% | |

| Chan 201152 | Hong Kong | 65,497 | 76.8±9.6 | 23.0% | |

| Chang 201453 | China | 135 | 66 (60–74) | 11.9% | |

| Chawla 201454 | USA | 54 | 70.0±12.0 | 70.0% | |

| Chen 200657 | Taiwan | 145 | 72.2±10.0 | 26.9% | |

| Chen 200956 | Canada | 108,726 | 72.3±10.9 | 45.5% | |

| Chen 202155 | China | 636 | 70.8±9.9 | 33.2% | |

| Chu 200458 | Hong Kong | 110 | 73.7±7.6 | 22.7% | |

| Chung 201059 | Australia | 100 | 70.6±9.5 | 44.0% | |

| Coban Agca 201760 | Turkey | 1490 | 67.7±11.1 | 35.0% | |

| Connolly 200662 | New Zealand | 7113 | 65–74 | 47.7% | |

| Couillard 201765 | Canada | 167 | 71.4±10.3 | 48.5% | |

| Coventry 201166 | UK | 79 | 65.3±9.9 | 44.3% | |

| Crisafulli 201468 | Spain | 123 | 69.4±9.8 | 6.6% | |

| Crisafulli 201570 | Spain | 125 | 69.2±9.8 | 6.4% | |

| Crisafulli 201669 | Spain | 110 | 70.5±9.6 | 6.4% | |

| de Miguel-Diez 201674 | Spain | 301,794 | 74.8±10.0 | 14.0% | |

| Duman 201576 | Turkey | 1704 | Not reported | 34.5% | |

| Ehsani 201979 | USA | 42 | 70.4±8.1 | 33.3% | |

| Emtner 200780 | Sweden | 21 | 65.0±9.3 | 66.7% | |

| Eriksen 201081 | Denmark | 300 | 72.1 | 61.7% | |

| Ernst 201982 | Canada | 203,642 | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Euceda 201883 | USA | 272 | 73.2±12.4 | 56.3% | |

| Fernandez-Garcia 202084 | Spain | 253 | 68.99.8 | 22.5% | |

| Fu 201585 | USA | 15,755 | 71.0±12.5 | 52.9% | |

| Ganapathy 201786 | USA | 11,496 | 70.7±10.8 | 52.5% | |

| Garcia-Aymerich 200387 | Spain | 340 | 69±9 | Not reported | |

| Garcia-Pachon 202189 | Spain | 106 | 73±10 | 21.7% | |

| Garcia-Sanz 202090 | Spain | 602 | 73.8±10.6 | 14.0% | |

| Gavish 201591 | Israel | 195 | 66±10 | 17.4% | |

| Ghanei 200797 | Iran | 98 | 58.3±11.0 | 37.0% | |

| Giron 200998 | Spain | 78 | 71±10 | 0.0% | |

| Glaser 201599 | USA | 617 | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Gonzalez 2008100 | Spain | 112 | 69.3±7.5 | Not reported | |

| Goto 2017102 | USA | 845,465 | 70 | 59.0% | |

| Goto 2018101 | USA | 76,697 | 76 (71–83) | 59.6% | |

| Goto 2020103 | USA | 905 | 76 (68–82) | 54.0% | |

| Gudmundsson 2005104 | Sweden | 406 | 69.2±10.5 | 51.2% | |

| Guerrero 2016105 | Spain | 378 | 71.4±10.0 | 15.9% | |

| Hajizadeh 2015108 | USA | 4791 | 74.3±6.4 | Not reported | |

| Hakansson 2020109 | Denmark | 4022 | 73.1 (63.7–81.1) | 55.2% | |

| Harries 2017110 | UK | 19,551 | 72.4±10.8 | 47.8% | |

| Hartl 2016111 | European countries | 16,016 | 70.8±10.8 | 32.2% | |

| Hasegawa 2016112 | USA | 3084 | 70 (61–79) | 50.0% | |

| Hegewald 2020114 | USA | 2445 | 68.4±11.6 | 50.7% | |

| Hemenway 2017115 | USA | 369 | 66 | 57.5% | |

| Huertas 2017116 | Spain | 150 | 70 (65–76) | 3.0% | |

| Ingadottir 2018117 | Iceland | 121 | 73.7±9.0 | 57.0% | |

| Islam 2015120 | USA | 350 | Not reported | 54.9% | |

| Iyer 2016121 | USA | 422 | 64.8±11.7 | 49.9% | |

| Jacobs 2018122 | USA | 1,055,830 | 68 (59–77) | 58.5% | |

| Janson 2020123 | Sweden | 51,247 | 74.6±10.1 | 54.8% | |

| Jing 2016127 | China | 8 | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Jo 2020128 | South Korea | 15,101 | 73.4±9.7 | 25.4% | |

| Johannesdottir 2013129 | Denmark | 3176 | 72.1 (65.2–77.7) | 55.2% | |

| Jones 2020130 | UK | 1029 | 74.4±9.9 | 49.0% | |

| Kasirye 2013132 | USA | 209 | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Kerkhof 2020135 | UK | 16,661 | 75.1±9.9 | 50.3% | |

| Keshishian 2019136 | USA | 7892 | 78.1±7.6 | 57.7% | |

| Kim 2010139 | South Korea | 77 | 69.2±9.4 | 16.9% | |

| Kim 2021140 | South Korea | 4867 | 75–79 | 30.9% | |

| Kishor 2020143 | India | 100 | 64.0±8.5 | 16.0% | |

| Ko 2020144 | Hong Kong | 346 | 74.9±7.8 | 3.8% | |

| Lau 2017151 | USA | 597,502 | Not reported | 55.3% | |

| Law 2016152 | Australia | 90 | 70.7±9.3 | 50.0% | |

| Li 2020156 | China | 108 | 70.6±9.3 | 21.3% | |

| Lindenauer 2014158 | USA | 25,628 | 69 (61–77) | 56.6% | |

| Lindenauer 2018157 | USA | 2340 | 76.3±7.5 | 56.1% | |

| Liu 2007159 | Taiwan | 100 | 73.8±10.6 | 15.0% | |

| Loh 2017160 | USA | 123 | 64.9±11.3 | 47.2% | |

| Marcos 2017161 | USA | 143 | 72.3±10.0 | 7.0% | |

| Martinez-Gestoso 2021162 | Spain | 615 | 73.9±10.6 | 13.8% | |

| Myers 2021168 | USA | 7825 | Not reported | 55.1% | |

| Myers 2021167 | USA | 333,429 | 70 (61–80) | 57.1% | |

| Nantsupawat 2012170 | USA | 81 | 73.9 | 53.1% | |

| Narewski 2015171 | USA | 160 | 63.9±10.8 | 58.8% | |

| Nastars 2019172 | USA | 298,706 | 77.7±7.7 | 59.6% | |

| Ng 2007173 | China | 376 | 72.2±8.4 | 14.9% | |

| Nguyen 2015176 | USA | 2910 | 72±11 | 57.1% | |

| Niu 2021177 | China | 378 | 75.2±8.9 | 15.9% | |

| Njoku 2022178 | Australia | 2448 | 72 (64–80) | 50.1% | |

| Osman 1997180 | UK | 266 | 68.0±9.1 | 47.0% | |

| Ozyilmaz 2013182 | Turkey | 107 | 66.3±8.6 | 15.0% | |

| Park 2016185 | South Korea | 339,379 | 71.5±11.6 | 29.8% | |

| Peng 2021187 | China | 123 | 71.1±9.6 | 26.8% | |

| Pienaar 2015189 | South Africa | 178 | 63±12 | 42.1% | |

| Ponce Gonzalez 2017191 | Spain | 361 | 75.0±11.5 | 21.1% | |

| Portoles-Callejon 2020192 | Spain | 108 | 71.5±11.7 | 18.5% | |

| Pouw 2000194 | Netherlands | 28 | 70.0±7.2 | 42.9% | |

| Pozo-Rodriguez 2015195 | Spain | 5174 | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Price 2006196 | UK | 7529 | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Quintana 2022198 | Spain | 876 | 73.7±9.4 | 20.5% | |

| Rahimi-Rad 2015199 | Iran | 100 | 70.8±10.3 | 31.0% | |

| Rinne 2015203 | USA | 25,301 | 68.9±10.5 | 3.2% | |

| Rinne 2017202 | USA | 33,558 | 68.7±10.4 | 3.4% | |

| Rinne 2017201 | USA | 33,558 | 68.7±10.4 | 3.4% | |

| Roberts 2002204 | UK | 1373 | 72 (66–78) | Not reported | |

| Roberts 2011205 | UK | 9716 | 65–74 | 50.0% | |

| Roberts 2015208 | USA | 306 | 70.3±12.3 | 56.2% | |

| Roberts 2016206 | USA | 3612 | 66.6±12.1 | 67.2% | |

| Roberts 2020207 | USA | 10,405 | 72.6±10.3 | 62.3% | |

| Rodrigo-Troyano 2018209 | Spain | 106 | 71±8 | 17.9% | |

| Ruby 2020210 | Egypt | 190 | 63.1±10.1 | 0.0% | |

| Shah 2015214 | USA | 947,084 | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Shani 2022215 | Israel | 1203 | 70.6±11.0 | 37.3% | |

| Sharif 2014216 | USA | 8263 | 56.5±5.7 | 58.8% | |

| Shay 2020218 | USA | 111 | 67.1±11.7 | 62.2% | |

| Simmering 2016221 | USA | 286,313 | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Singer 2020223 | USA | 28,240 | 72.7±8.7 | 51.9% | |

| Singh 2016224 | USA | 135,498 | 75–84 | 60.2% | |

| Snider 2015225 | USA | 378,419 | 76.2±6.9 | 56.8% | |

| Stefan 2017228 | USA | 13,893 | 69 | 57.6% | |

| Stuart 2010232 | USA | 6322 | 74.7±0.4 | 48.9% | |

| Tran 2016234 | USA | 375 | 59.3±7.4 | 64.0% | |

| Turner 2014235 | England | 1942 | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Ushida 2022236 | Japan | 3396 | 75.0±11.2 | 20.4% | |

| Wang 2013242 | Norway | 481 | 72.8±10.5 | 53.4% | |

| Wong 2008244 | Canada | 109 | 63.0±14.5 | 38.5% | |

| Wu 2020245 | Taiwan | 625 | 76.3±10.6 | 12.0% | |

| Wu 2021247 | Taiwan | 625 | 76.3±10.6 | 12.0% | |

| Wu 2021246 | USA | 91 | 60±11 | 63.7% | |

| Yilmaz 2021249 | Turkey | 110 | 67.8±9.3 | 18.2% | |

| Yu 2015250 | USA | 18,282 | 56.6±5.8 | 62.4% | |

| Zapatero 2013253 | Spain | 313,233 | 72.7±15.7 | 30.3% | |

| Zhou 2021254 | China | 417 | 75±12 | 20.4% | |

| Zhu 2021255 | China | 239 | 72 | 16.7% | |

Note: Blacked out cells indicate that data are not available/applicable.

Table 2.

Studies Assessing Interventions

| Study | Country | n | Age (years) | % Female | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Median (IQR) | ||||

| Cohort Studies | |||||

| Adamson 201616 | Canada | 462 | 70.6±13.2 | 40.9% | |

| Agarwal 201817 | USA | 1248 | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Alshehri 202126 | Saudi Arabia | 80 | 67.0±10.3 | 41.3% | |

| Ankjaergaard 201727 | Denmark | 201 | 71.5±10.8 | 56.7% | |

| Ban 201232 | Malaysia | 193 | 68.5±8.8 | 13.0% | |

| Bashir 201635 | USA | 461 | 71.7±13.3 | 32.5% | |

| Bhatt 201739 | USA | 187 | 70.4±11.2 | 61.0% | |

| Collinsworth 201861 | USA | 308 | 70.5±12.2 | 58.4% | |

| Cope 201564 | UK | 464 | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Dalal 201271 | USA | 1936 | 63.9±9.9 | 55.4% | |

| De Batlle 201272 | Spain | 274 | 68±8 | 6.9% | |

| Gay 202092 | USA | 157 | 70.6±11.2 | 56.1% | |

| Gentene 202193 | USA | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |

| George 201694 | Singapore | 340 | 72.6±9.1 | 11.8% | |

| Gerber 201895 | Australia | 381 | 71±12 | 39.9% | |

| Gerrits 200396 | Netherlands | 1219 | 65–74 | 40.4% | |

| Gulati 2018106 | USA | 250 | 69±11 | 42.0% | |

| Ingadottir 2018118 | Iceland | 99 | 73.0 (71.0–77.0) | 54.5% | |

| Ingadottir 2018117 | Iceland | 121 | 73.7±9.0 | 57.0% | |

| Jeffs 2005124 | Australia | 216 | 67.5 | 63.9% | |

| Joyner 2022131 | USA | 253 | 73.6±7.1 | 65.2% | |

| Kawasumi 2013133 | Canada | 3723 | 72.8 | 50.8% | |

| Kim 2020138 | USA | 65 | 62.5±9.0 | 58.5% | |

| Kiri 2005141 | UK | 2557 | 71.1±9.0 | 49.6% | |

| Kiser 2019142 | USA | 28,700 | 60–69 | 53.9% | |

| Ko 2014147 | Hong Kong | 185 | 76.9±7.37 | 10.3% | |

| Ko 2021148 | |||||

| Lalmolda 2017149 | Spain | 48 | 72.5±7.2 | 6.2% | |

| LaRoche 2016150 | USA | 3024 | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Lee 2016153 | USA | 995 | 67.3±10.5 | 52.6% | |

| Matsui 2017163 | Japan | 12,572 | 78.4±9.5 | 18.7% | |

| McGurran 2019164 | USA | 2885 | 70.5±11.5 | 46.9% | |

| Moullec 2012166 | Canada | 189 | 72.1±10.4 | 50.3% | |

| Myers 2020169 | USA | 805,764 | Not reported | 56.3% | |

| Nguyen 2014175 | USA | 4596 | 72.3±10.8 | Not reported | |

| Nguyen 2021174 | USA | 128 | 64.6±9.2 | 56.3% | |

| Ohar 2018179 | USA | 1274 | Not reported | 56.3% | |

| Pant 2020183 | Nepal | 86 | 70.6±11.0 | 47.7% | |

| Parikh 2016184 | USA | 44 | 66 | 40.9% | |

| Pendharkar 2018186 | Canada | 1435 | 70±12 | 48.5% | |

| Petite 2020188 | USA | 358 | 67.1±11.6 | 60.9% | |

| Pitta 2006190 | Belgium | 17 | 69 (60−78) | 5.9% | |

| Puebla Neira 2021197 | USA | 4,587,542 | Not reported | 42.2% | |

| Revitt 2013200 | UK | 160 | 70.4±8.6 | 45.6% | |

| Rueda-Camino 2017211 | Spain | 87 | 70.4±9.3 | 11.5% | |

| Russo 2017212 | USA | 160 | 65.9±10.0 | 52.5% | |

| Seys 2018213 | European countries | 257 | 69.8±10.3 | 33.9% | |

| Sharma 2010217 | USA | 62,746 | 75–84 | 58.6% | |

| Shi 2018219 | China | 6333 | 67.5±9.5 | Not reported | |

| Shin 2019220 | South Korea | 308 | 72.3±9.5 | 23.7% | |

| Sin 2001222 | Canada | 22,620 | 75.1±6.7 | 43.5% | |

| Sonstein 2014226 | USA | 420 | 66.5±11.2 | 49.5% | |

| Stefan 2013227 | USA | 53,900 | 70 (61–78) | 58.0% | |

| Stefan 2021229 | USA | 197,376 | 76.9±7.6 | 58.6% | |

| Suh 2015233 | England | 120 | 70±9 | 51.7% | |

| van Eeden 2017238 | Netherlands | 10 | 62.9±9.6 | 80.0% | |

| Werre 2015243 | USA | 244 | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Zafar 2019252 | USA | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |

| Zafar 2020251 | USA | 133 | 60.0±9.8 | 36.1% | |

| Randomized Controlled Trials | |||||

| Atwood 202228 | Canada | 3710 | 71.7±12.4 | 49.7% | |

| Benzo 201637 | USA | 215 | 68.0±9.5 | 54.9% | |

| Bucknall 201247 | UK | 464 | 69.1±9.3 | 63.4% | |

| Conti 200263 | Italy | 49 | 71.8±7.8 | Not reported | |

| Criner 201867 | USA | 64 | 61.7±7.9 | 60.9% | |

| De Jong 200773 | Netherlands | 210 | 70.7±8.4 | 25.3% | |

| Deutz 202175 | USA | 214 | 74.8±7.3 | 52.8% | |

| Eaton 200677 | New Zealand | 78 | 77.3±7.1 | 53.8% | |

| Eaton 200978 | New Zealand | 97 | 69.9±9.8 | 56.7% | |

| Garcia-Aymerich 200788 | Spain | 113 | 73±8 | 14.2% | |

| Gunen 2007107 | Turkey | 159 | 64.1±8.9 | 12.0% | |

| Hegelund 2020113 | Denmark | 100 | 73 (45–89) | 58.0% | |

| Ip 2004119 | Hong Kong | 130 | 80.5±6.6 | 0.0% | |

| Jennings 2015125 | USA | 172 | 64.7±10.6 | 55.2% | |

| Jimenez 2021126 | Spain | 737 | 70.4±9.9 | 26.5% | |

| Kebede 2022134 | Norway | 40 | 73.8±8.2 | 62.5% | |

| Khosravi 2020137 | Iran | 60 | 71.0±8.9 | 28.3% | |

| Ko 2011146 | Hong Kong | 60 | 73.6±7.0 | 1.7% | |

| Ko 2017145 | Hong Kong | 180 | 74.8±8.2 | 4.4% | |

| Ko 2021148 | Hong Kong | 136 | 75.0±7.6 | 2.9% | |

| Lellouche 2016154 | Canada | 50 | 72±8 | 46.0% | |

| Li 2020155 | China | 378 | 66.3±8.1 | 15.9% | |

| Monreal 2016165 | Spain | 120 | 71 (61–78) | 33.3% | |

| Ozturk 2020181 | Turkey | 61 | 62.5±8.6 | 11.5% | |

| Pourrashid 2018193 | Iran | 62 | 63.4±8.5 | 16.1% | |

| Stolz 2007230 | Switzerland | 226 | 69.5 | 50.4% | |

| Struik 2014231 | Netherlands | 201 | 63.7±8.3 | 58.7% | |

| Utens 2012237 | Netherlands | 139 | 68.0±10.8 | 38.1% | |

| Vanhaecht 2016239 | European countries | 342 | 69.9±10.3 | 32.2% | |

| Vermeersch 2019240 | Belgium | 301 | 65.5±9.5 | 43.9% | |

| Wang 2016241 | China | 191 | 72.9±9.6 | 28.3% | |

| Xia 2022248 | China | 337 | 70.0 (65.0–75.0) | 16.9% | |

Note: Blacked out cells indicate that data are not available/applicable.

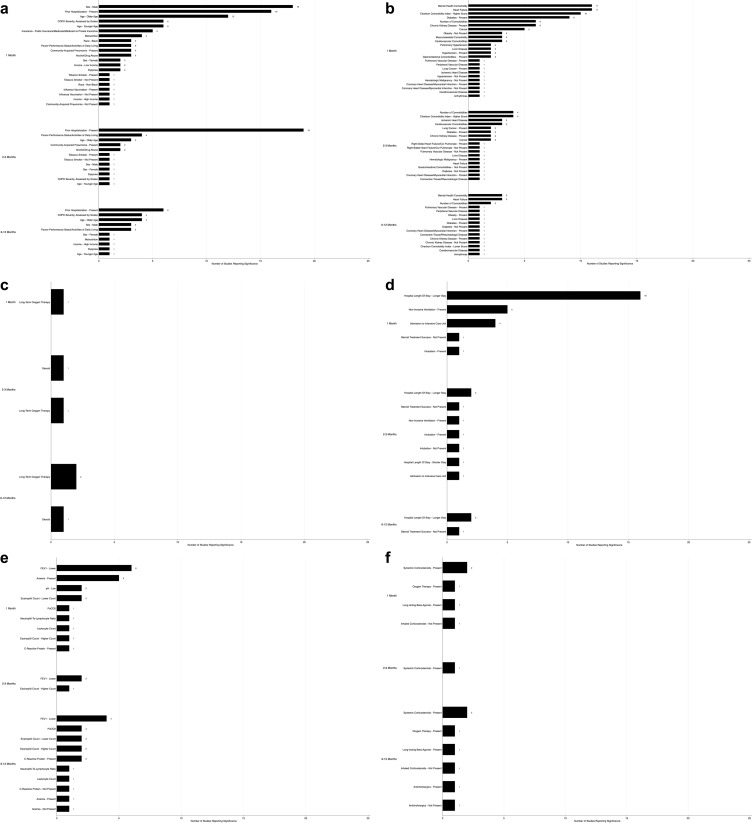

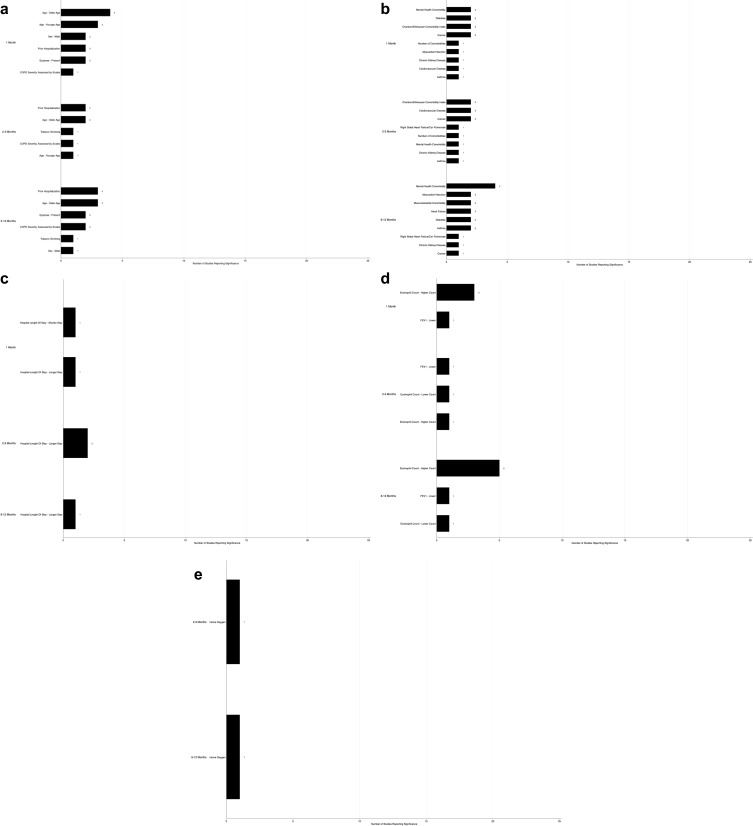

A total of 64 significant predictors for all-cause readmission were reported across the literature. Summarizing across all readmission time frames, male sex, prior hospitalization, poorer performance status/activities of daily living, and older age were the most frequently reported patient characteristics that were predictors of readmission. Other significant predictors were COPD severity, alcohol/drug abuse, malnutrition, and history of community-acquired pneumonia (Figure 3a). Heart failure, mental health comorbidity, higher Charlson comorbidity index, diabetes, higher number of comorbidities, chronic kidney disease, and cancer were among the most commonly reported comorbidity predictors of readmission (Figure 3b). Among medications used prior to admission that were significant of readmission, long-term oxygen therapy was the most commonly reported predictor (Figure 3c). Hospital length of stay, non-invasive ventilation, intubation, and admission to the intensive care unit were the most common hospital care predictors of readmission (Figure 3d). Among laboratory values, lower FEV1 and anemia were the most common predictors (Figure 3e). Use of systemic corticosteroids during hospital admission was the most frequently reported predictor of readmission, among medications used during admission (Figure 3f). Discharge to long-term care or a skilled nursing facility was the most commonly reported predictor of readmission, of assessed predictors after admission (Figure 3f–h). Degrees of significance, and the specific studies reporting on each significant predictor, are reported in Table 3.

Figure 3.

Continued.

Figure 3.

Significant predictors of all-cause readmission: (a) patient characteristics; (b) comorbidities; (c) medications prior to admission; (d) hospital care; (e) investigations; (f) medications during hospitalization; (g) medications on discharge; (h) disposition.

Table 3.

Significant Predictors for All-Cause Readmission

| Variable Type | Type I Error | 1 Month | 2–3 Months | 6–12 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | ||||

| Age | <0.05 | Correlated29,53,105,172 Inversely correlated191 |

Correlated38 Inversely correlated183 |

Correlated53,66,127 |

| <0.01 | Correlated33,49,50,123,185,233,253 Inversely correlated34,122,151,214,221 |

Correlated111,123 | Correlated123 Inversely correlated76 |

|

| Not reported | Correlated29 | |||

| Alcohol/drug abuse | <0.05 | Correlated29 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated49,224 | Correlated34,205 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Community-acquired pneumonia | <0.05 | Correlated83,210 Inversely correlated208 |

Correlated254 | |

| <0.01 | Correlated50 | Correlated50 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| COPD severity, assessed by scales | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated25,49,50,105,247,250 | Correlated50 | Correlated53,55,127,244 | |

| Not reported | ||||

| Dyspnea | <0.05 | Correlated54 | Correlated38 | Correlated84 |

| <0.01 | Correlated105 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Income | <0.05 | Correlated215 | ||

| <0.01 | Inversely correlated122,224 | Correlated97 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Insurance: public insurance/Medicare/Medicaid vs private insurance | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated49,53,122,128,151 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Male | <0.05 | Correlated16,35,151,172,178,215,216 Inversely correlated123 |

Inversely correlated123 | Correlated59 Inversely correlated123 |

| <0.01 | Correlated49,53,74,122,128,140,185,214,224,232 Inversely correlated253 | Correlated195 | Correlated41,76 | |

| Not reported | Correlated201 | |||

| Malnutrition | <0.05 | Correlated74 | Correlated139 | |

| <0.01 | Correlated33,74,253 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Poorer performance status/activities of daily living | <0.05 | Correlated25,84,247 | Correlated25,195,198 | Correlated30,84,104 |

| <0.01 | Correlated62 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Prior hospitalization | <0.05 | Correlated54,84,178,212,233 | Correlated20,38,178,183 | Correlated178 |

| <0.01 | Correlated25,31,49,105,125,172,175,176,208,215,216 | Correlated22,25,31,45,84,89,91,111,125,195,198,209,212,215 | Correlated41,55,81,87,104 | |

| Not reported | Correlated62 | |||

| Race: black | <0.05 | Inversely correlated172 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated102,151,214 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Tobacco smoker | <0.05 | Correlated247 | Correlated45 | |

| <0.01 | Inversely correlated253 | Inversely correlated38 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Vaccination: influenza | <0.05 | Correlated170 | ||

| <0.01 | Inversely correlated232 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Number of comorbidities | <0.05 | Correlated29,34,35,123,172 | Correlated38,123 | Correlated123 |

| <0.01 | Correlated122 | Correlated34,205 | Correlated244 | |

| Not reported | ||||

| Arrhythmias | <0.05 | Correlated24 | Correlated56 | |

| <0.01 | ||||

| Not reported | ||||

| Cancer | <0.05 | Correlated31 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated31,33,49,50,253 | Correlated50 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Cardiovascular comorbidities | <0.05 | Correlated34,103 | Correlated38,198 | |

| <0.01 | Correlated49 | Correlated34 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Cerebrovascular disease | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated49 | Correlated31 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Charlson comorbidity index | <0.05 | Correlated74,215,255 | Correlated195,215 | Inversely correlated178 |

| <0.01 | Correlated33,50,128,175,176,214,253 | Correlated50,111 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Chronic kidney disease | <0.05 | Correlated54 | Correlated31 | Inversely correlated76 |

| <0.01 | Correlated33,49,50,122,250 | Correlated50 | Correlated31 | |

| Not reported | ||||

| Connective tissue/rheumatologic disease | <0.05 | Correlated31 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated208 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Coronary heart disease/myocardial infarction | <0.05 | Correlated31 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated49 Inversely correlated255 |

Correlated31 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Diabetes | <0.05 | Correlated212,232 | Correlated31,205 Inversely correlated111 |

Correlated108 |

| <0.01 | Correlated31,33,49,122,151,176,232 | Correlated30 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Gastrointestinal comorbidities | <0.05 | Correlated212 | Inversely correlated208 | |

| <0.01 | Correlated49 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Heart failure | <0.05 | Correlated24,29,216,232 | Correlated56,108 | |

| <0.01 | Correlated31,33,49,122,176,250,253 | Correlated31 | Correlated31 | |

| Not reported | ||||

| Right-sided heart failure/cor pulmonale | <0.05 | Inversely correlated208 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated205 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Hematologic malignancy | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Inversely correlated208 | Correlated208 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Hypertension | <0.05 | Correlated212,232 | ||

| <0.01 | Inversely correlated49 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Ischemic heart disease | <0.05 | Correlated232 | Correlated20 | |

| <0.01 | Correlated50,205 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Liver disease | <0.05 | Correlated31 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated31,49 | Correlated31 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Lung cancer | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated50,216 | Correlated50,205 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Mental health comorbidity | <0.05 | Correlated25,29,176 | Correlated66,97,108 | |

| <0.01 | Correlated14,49,83,151,216,224,232,250 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Musculoskeletal comorbidity | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated216,232,247 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Obesity | <0.05 | Correlated84 | ||

| <0.01 | Inversely correlated74,122,253 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Peripheral vascular disease | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated49 | Correlated31 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Pulmonary hypertension | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated176,250 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Pulmonary vascular disease | <0.05 | Inversely correlated208 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated250 | Correlated56 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Medications Prior to Admission | ||||

| Long-term oxygen therapy | <0.05 | Correlated24 | Correlated183 | Correlated100 |

| <0.01 | Correlated104 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Steroid | <0.05 | Correlated215 | Correlated244 | |

| <0.01 | ||||

| Not reported | ||||

| Hospital Care | ||||

| Admission to ICU | <0.05 | Correlated172,224,250 | Correlated183 | |

| <0.01 | Correlated214 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Hospital length of stay | <0.05 | Correlated25,33,172,216,224,250 | Correlated38 Inversely correlated183 |

Correlated76,104 |

| <0.01 | Correlated49,50,105,122,128,140,185,202,214,253 | Correlated50 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Intubation | <0.05 | Inversely correlated208 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated49 | Correlated111 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Non-invasive ventilation | <0.05 | Correlated74,212 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated33,49,247 | Correlated38 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Steroid treatment success | <0.05 | Inversely correlated69 | Inversely correlated69 | |

| <0.01 | Inversely correlated69 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Investigations | ||||

| Anemia | <0.05 | Correlated108 Inversely correlated76 |

||

| <0.01 | Correlated33,49,175,176,250 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| C-reactive protein | <0.05 | Correlated60 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated53,127 Inversely correlated76 |

|||

| Not reported | ||||

| Eosinophil count | <0.05 | Inversely correlated135,199 | Correlated114 | Correlated65 Inversely correlated76,156 |

| <0.01 | Correlated247 | Correlated114 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| FEV1 | <0.05 | Inversely correlated204,235,249 | Inversely correlated89,182 | Inversely correlated66 |

| <0.01 | Inversely correlated105,212,247 | Inversely correlated53,87,104 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Leukocyte count | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated60 | Correlated76 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated60 | Correlated76 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| PaCO2 | <0.05 | Correlated100,139 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated105 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| pH | <0.05 | Inversely correlated105,255 | ||

| <0.01 | ||||

| Not reported | ||||

| Medications During Hospitalization | ||||

| Anticholinergics | <0.05 | Correlated87 | ||

| <0.01 | Inversely correlated104 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Inhaled corticosteroids | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Inversely correlated208 | Inversely correlated55 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Oxygen therapy | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated175 | Correlated31 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Long-acting beta-agonist | <0.05 | Correlated176 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated55 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Systemic corticosteroids | <0.05 | Correlated175 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated176 | Correlated31 | Correlated31,76 | |

| Not reported | ||||

| Medications on Discharge | ||||

| Oral corticosteroids | <0.05 | Inversely correlated216 | Correlated195 | |

| <0.01 | ||||

| Not reported | ||||

| Maintenance medication | <0.05 | Inversely correlated232 | ||

| <0.01 | Inversely correlated234 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Short-acting muscarinic antagonist | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated208 Inversely correlated208 |

|||

| Not reported | ||||

| Disposition | ||||

| Discharged with home care | <0.05 | Correlated81 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated214 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Discharged to long-term care/skilled nursing facility | <0.05 | Correlated74,232 Inversely correlated224 |

Correlated108 | |

| <0.01 | Correlated35,49,122,128 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Follow-up within 30 days of discharge | <0.05 | Correlated125 Inversely correlated91 |

||

| <0.01 | Inversely correlated216 | Correlated182,198 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Prediction Scores | ||||

| BODEX index23 | p=0.008 | |||

| CODEX index23 | p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | ||

| CORE score247 | p<0.001 | |||

| DOSE index23 | p<0.01 | |||

| PEARL score143 | p<0.0001 | |||

| RACE scale151 | R2=0.923 | |||

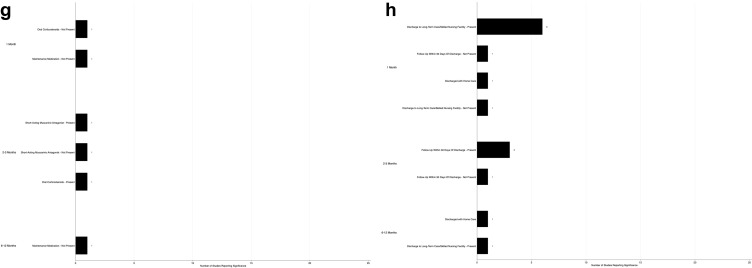

For COPD-related readmission, 23 significant predictors were found. The most common patient characteristics that were predictors were older age and prior hospitalization (Figure 4a). Mental health comorbidity, diabetes, high Charlson/Elixhauser comorbidity index, and cancer were the most frequently reported comorbidity predictors of readmission (Figure 4b). Longer hospital length of stay, higher eosinophil count, and home oxygen after discharge were also frequently reported predictors of readmission (Figure 4c and e). Degrees of significance, and the specific studies reporting on each significant predictor, are reported in Table 4.

Figure 4.

Significant predictors of COPD-related readmission: (a) patient characteristics; (b) comorbidities; (c) hospital care; (d) investigations; (e) medications on discharge.

Table 4.

Significant Predictors of COPD-Related Readmission

| Type I Error | 1 Month | 2–3 Months | 6–12 Months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | ||||

| Age | <0.05 | Correlated219,245 | Correlated31,129,234 | |

| <0.01 | Correlated50,110 Inversely correlated34,48,206 |

Correlated50,110 Inversely correlated34 |

||

| Not reported | ||||

| COPD severity, assessed by scales | <0.05 | Correlated21,187 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated50 | Correlated50 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Dyspnea | <0.05 | Correlated116 | Correlated21 | |

| <0.01 | Correlated206 | Correlated206 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Male | <0.05 | Correlated129 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated48 | |||

| Not reported | Correlated201 | |||

| Prior hospitalization | <0.05 | Correlated129 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated31,70 | Correlated22,31 | Correlated21,31 | |

| Not reported | ||||

| Tobacco smoking | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated34 | Correlated206 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Number of comorbidities | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated219 | Correlated34 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Asthma | <0.05 | Correlated129 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated206 | Correlated50 | Correlated206 | |

| Not reported | ||||

| Cancer | <0.05 | Correlated31,50 | Correlated31,50 | |

| <0.01 | Correlated31 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Cardiovascular disease | <0.05 | Correlated34 | Correlated34 | |

| <0.01 | Correlated135 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Charlson/Elixhauser comorbidity index | <0.05 | Correlated22 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated48,50 | Correlated50 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Chronic kidney disease | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated50 | Correlated50 | Correlated31 | |

| Not reported | ||||

| Diabetes | <0.05 | Correlated206 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated70 | Correlated31,206 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Heart failure | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated31,206 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Right-sided heart failure/cor pulmonale | <0.05 | Correlated21 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated22 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Mental health comorbidity | <0.05 | Correlated21,129 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated121,206 | Correlated121 | Correlated121,206 | |

| Not reported | ||||

| Musculoskeletal comorbidity | <0.05 | Correlated129 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated206 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Correlated31,129 | |||

| Not reported | Correlated99 | |||

| Hospital Care | ||||

| Hospital length of stay | <0.05 | Inversely correlated110 | Correlated187 | |

| <0.01 | Correlated50 | Correlated50,110 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Investigations | ||||

| Eosinophil count | <0.05 | Correlated114 | Correlated112 Inversely correlated156 |

|

| <0.01 | Correlated114,245 | Correlated114 Inversely correlated135 |

Correlated36,65,114,187 | |

| Not reported | ||||

| FEV1 | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Inversely correlated34 | Inversely correlated34,135 | Inversely correlated245 | |

| Not reported | ||||

| Medications During Admission | ||||

| Oxygen therapy | <0.05 | |||

| <0.01 | Inversely correlated185 | Correlated31 | ||

| Not reported | ||||

| Medications on Discharge | ||||

| Home oxygen | <0.05 | Correlated21 | ||

| <0.01 | Correlated22 | |||

| Not reported | ||||

Six prediction scores – the BODEX index,23 CODEX index,23 CORE score,247 DOSE index,23 PEARL score,143 and RACE scale151 – were reported to be predictive of all-cause readmission. The included components of each prediction score are reported in Table 5. CORE, PEARL, and RACE were reported to have good predictive value for readmission as a time-to-event outcome variable. The BODEX index, CODEX index, and DOSE index were reported to have good predictive ability for 2–3-month readmission. The CODEX index was reported to have good predictive ability for 6–12-month readmission (Table 3).

Table 5.

Characteristics of Prediction Scores

| CODEX | BODEX | PEARL | CORE | RACE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | Comorbidity Number of severe exacerbations (ED or admission) mMRC scale |

BMI Number of severe exacerbations (ED or admission) mMRC scale |

Age Previous admissions Left heart failure/right heart failure eMRC scale Right heart failure |

Lung function Neuromuscular disease exacerbations Triple inhaler management |

Age Gender Income Race Payer Comorbidities |

| Hospitalization management | – | – | – | – | |

| In-hospital investigations | FEV1% | FEV1% | Eosinophil count | ||

| Discharge characteristics | – | – | – | – |

Some studies reported significant interventions that can reduce all-cause and COPD-related readmission, most notably use of a COPD-specific care package (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). Most studies reporting on interventions reported that their intervention was not associated with a significant reduction in readmission rates.

Discussion

This is the largest systematic review to date, reporting on predictors for readmission of patients with COPD, with 242 articles reporting on 16,471,096 patients included in this review. We comprehensively report on predictors for both all-cause and COPD-related readmissions, for readmission at 1 month, 2–3 months, and 6–12 months. The included studies originated from around the world, and there was generally a low risk of bias. There were 64 predictors for all-cause readmission and 23 predictors for COPD-specific readmission. Significant predictors for all-cause readmissions included 1) pre-admission patient characteristics, such as male sex, prior hospitalization, poor performance status, number and type of comorbidities, and use of long-term oxygen; 2) hospitalization details, such as length of stay, use of corticosteroids, and use of ventilatory support; 3) results of investigations, including anemia, lower FEV1, and higher eosinophil count; and 4) discharge characteristics, including the use of home oxygen and discharge to long-term care or a skilled nursing facility.

Several prior systematic reviews have also reported on predictors. Alqahtani et al reviewed 14 studies, stating that comorbidities, previous exacerbations/hospitalizations, and increased length of initial hospital stay were major risk factors for 30- and 90-day all-cause readmission.8 Heart failure, renal failure, depression, and alcohol use were also associated with increased 30-day all-cause readmission, with being female described as a protective factor for readmission. Bahadori and Fitzgerald examined 17 studies, and found that previous hospital admission, dyspnea, and oral corticosteroids were significant risk factors for readmission.9 Njoku et al reviewed 57 studies, and found that hospitalization in the year prior to index admission, comorbidities (such as asthma), living in a deprived area, and living in/or discharge to a nursing home were key predictors of COPD-related readmission.10

This review identifies some notable predictors worth highlighting that are not contained in previous studies, which were parsimonious. While prior studies reported heart failure and neuromuscular disease, we identified other significant preadmission comorbidities, including alcohol use, diabetes, and mental health. Similarly, poor performance status and malnutrition were both identified as important predictors of readmission. In-hospital use of critical care, including non-invasive ventilation, invasive ventilation, and ICU stay, was also identified as predictors. Use of steroids was also predictive of readmission; this was probably related to the severity of disease. Eosinophil count was both correlated and inversely correlated in different studies. While all studies excluded corticosteroid use prior to measurement of the eosinophil count, the studies used various cut-offs to define eosinopenia.114,135,199,247 Further research to determine the utility of eosinophil count is needed.

With COPD patients having a high all-cause readmission rate of 50%5 and being the largest single group of chronic disease patients reported in the literature, identifying those at greatest risk of readmission is a priority as more resources can be directed to this group. This comprehensive systematic review identifies many predictors across multiple domains, including prior to admission, during hospitalization, and post-hospitalization. Current prediction rules for readmissions have areas under the receiver operating characteristics curve in the range 0.70–0.72, and may be limited by lacking variables in all domains (Table 5). The findings from this systematic review can be used to develop other prediction scores with higher predictive power. The findings can also be used in clinical practice to help identify individual patients who may benefit from more resources to reduce their risk of readmission. While most prediction scores for COPD readmission are parsimonious, having five or fewer variables for ease of use, a more complicated model with more predictors may be more accurate. More complex models may be enabled through the increase in electronic patient records, which enable more discrete data elements as well as computer decision support.256

This review was not without limitations. There was heterogeneous reporting on some predictor variables; many studies used different cut-off points for predictor variables. We therefore reported on the general directionality of a predictor variable as it relates to readmission. We have reported the predictors as reported by the studies, using their original cut-off points and without any synthesis, in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. In addition, we were unable to report non-significant predictors owing to non-uniform reporting and therefore the total number of studies investigating each predictor. It is therefore unclear how many studies investigated specific predictors, and what proportion of them reported significant correlation with readmission. For certain predictors that may not be as well studied (eg malnutrition), there could be underestimation of importance.

It is also important to note that some published literature suggests that not all patients discharged with a diagnosis of “COPD” have spirometrically confirmed COPD, and therefore patients discharged with “COPD” may in fact have other comorbidities, such as congestive heart failure.257 Therefore, caution is needed in the interpretation of some of the included studies, given that they simply included patients with a diagnosis of COPD which may not necessarily be confirmed on spirometry. Future studies could look to assess only patients who have spirometrically confirmed COPD.

There may also be some concerns over the generalizability of individual studies to the larger population of patients with COPD admitted to hospitals. There were three studies127,190,238 with sample sizes of less than 20, and another three studies80,134,194 with sample sizes of 20–40 patients. Moreover, there were three studies98,119,210 with no females included in the sample, and another 52 studies20–23,29,32,38,42,51,53,68–70,72,74,88,90,91,94,116,139,143–149,155,159,161–163,173,177,181,182,190,192,193,201–203,209,211,245,247,249,255 where less than 20% of the sample comprised of females. Reassuringly, the significant predictors reported by these studies agree with larger and more representative studies. In addition, a large proportion of the studies originated from the USA, which may make the results of this review more generalizable to the US population and slightly less generalizable to other countries, especially given the lack of a universal healthcare system in the USA and therefore the potential confounding effect on readmissions.

In conclusion, we found that predictors of readmissions after an admission for COPD exacerbation included patient characteristics prior to and at admission, hospitalization management, results from admission investigations, and discharge characteristics. Findings from this review may enable better model generation if predictors from all these domains are included. These findings may also be used to identify new predictors in the different domains and can be used by clinicians to help generate their gestalt of readmission.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (The BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet. 2007;370(9589):741–750. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61377-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adeloye D, Song P, Zhu Y, Campbell H, Sheikh A, Rudan I. Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10(5):447–458. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00511-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd)#:~:text=Key%20facts,3.23%20million%20deaths%20in%202019. Accessed August 17, 2022.

- 4.Hernandez C, Jansa M, Vidal M, et al. The burden of chronic disorders on hospital admissions prompts the need for new modalities of care: a cross-sectional analysis in a tertiary hospital. QJM. 2009;102(3):193–202. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcn172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rohde J, Joseph A, Tambedou B, et al. Reducing 30-day all-cause acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmission with a multidisciplinary quality improvement project. Cureus. 2021;13:e19917. doi: 10.7759/cureus.19917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harries TH, Thornton HV, Crichton S, Schofield P, Gilkes A, White PT. Length of stay of COPD hospital admissions between 2006 and 2010: a retrospective longitudinal study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:603–611. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S77092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellou V, Belbasis L, Konstantinidis AK, Tzoulaki I, Evangelou E. Prognostic models for outcome prediction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ. 2019;367:l5358. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alqahtani JS, Njoku CM, Bereznicki B, et al. Risk factors for all-cause hospital readmission following exacerbation of COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29(156):190166. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0166-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bahadori K, FitzGerald JM. Risk factors of hospitalization and readmission of patients with COPD exacerbation--systematic review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2007;2(3):241–251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Njoku CM, Alqahtani JS, Wimmer BC, et al. Risk factors and associated outcomes of hospital readmission in COPD: a systematic review. Respir Med. 2020;173:105988. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.105988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins J, Morgan R, Rooney A, et al. Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies - of Exposure (ROBINS-E); 2022. Available from: https://www.riskofbias.info/welcome/robins-e-tool. Accessed August 11, 2023.

- 14.Abrams TE, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Van der Weg MW. Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the effect of existing psychiatric comorbidity on subsequent mortality. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(5):441–449. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abusaada K, Alsaleh L, Herrera V, Du Y, Baig H, Everett G. Comparison of hospital outcomes and resource use in acute COPD exacerbation patients managed by teaching versus nonteaching services in a community hospital. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23(3):625–630. doi: 10.1111/jep.12688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adamson SL, Burns J, Camp PG, Sin DD, van Eeden SF. Impact of individualized care on readmissions after a hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:61–71. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S93322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal A, Baechle C, Behara R, Zhu X. A natural language processing framework for assessing hospital readmissions for patients with COPD. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2018;22(2):588–596. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2017.2684121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agarwal A, Zhang W, Kuo Y, Sharma G. Process and outcome measures among COPD patients with a hospitalization cared for by an advance practice provider or primary care physician. PLoS One. 2016;11(2). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aksoy E, Gungor S, Agca MC, et al. A revised treatment approach for hospitalized patients with Eosinophilic and Neutrophilic exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Turk. 2018;19(4):193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al Aqqad SMH, Tangiisuran B, Hyder Ali IA, Md Kassim RMN, Wong JL, Tengku Saifudin TI. Hospitalisation of multiethnic older patients with AECOPD: exploration of the occurrence of anxiety, depression and factors associated with short-term hospital readmission. Clin Respir J. 2017;11(6):960–967. doi: 10.1111/crj.12448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Almagro P, Barreiro B, De Echaguen AO, et al. Risk factors for hospital readmission in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2006;73(3):311–317. doi: 10.1159/000088092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Almagro P, Cabrera FJ, Diez J, et al. Comorbidities and short-term prognosis in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbation of COPD: the EPOC en servicios de medicina interna (ESMI) study. Chest. 2012;142(5):1126–1133. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almagro P, Soriano JB, Cabrera FJ, et al. Short- and medium-term prognosis in patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbation: the CODEX index. Chest. 2014;145(5):972–980. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alpaydin AO, Ozuygur SS, Sahan C, Tertemiz KC, Russell R. 30-day readmission after an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with cardiovascular comorbidity. Turk Thorac J. 2021;22(5):369–375. doi: 10.5152/TurkThoracJ.2021.0189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alqahtani JS, Aldabayan YS, Aldhahir AM, Al Rajeh AM, Mandal S, Hurst JR. Predictors of 30- and 90-day COPD exacerbation readmission: a Prospective Cohort Study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2021;16:2769–2781. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S328030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alshehri S, Alalawi M, Makeen A, et al. Short-term versus long-term systemic corticosteroid use in the acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Malaysian J Med Sci. 2021;28(1):59–65. doi: 10.21315/mjms2021.28.1.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ankjaergaard KL, Rasmussen DB, Schwaner SH, Andreassen HF, Hansen EF, Wilcke JT. COPD: mortality and readmissions in relation to number of admissions with noninvasive ventilation. COPD. 2017;14(1):30–36. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2016.1181160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atwood CE, Bhutani M, Ospina MB, et al. Optimizing COPD acute care patient outcomes using a standardized transition bundle and care-coordinator: a randomized clinical trial. Chest. 2022;162(2):321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bade BC, DeRycke EC, Ramsey C, et al. Sex differences in veterans admitted to the hospital for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(6):707–714. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201809-615OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bahadori K, FitzGerald JM, Levy RD, Fera T, Swiston J. Risk factors and outcomes associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations requiring hospitalization. Can Respir J. 2009;16(4):e43–e9. doi: 10.1155/2009/179263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker CL, Zou KH, Su J. Risk assessment of readmissions following an initial COPD-related hospitalization. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:551–559. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S51507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ban A, Ismail A, Harun R, Abdul Rahman A, Sulung S, Syed Mohamed A. Impact of clinical pathway on clinical outcomes in the management of COPD exacerbation. BMC Pulm Med. 2012;12(1). doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-12-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barba R, Casasola GGD, Marco J, et al. Anemia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a readmission prognosis factor. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(4):617–622. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.675318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartels W, Adamson S, Leung L, Sin DD, van Eeden SF. Emergency department management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: factors predicting readmission. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:1647–1654. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S163250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bashir B, Schneider D, Naglak MC, Churilla TM, Adelsberger M. Evaluation of prediction strategy and care coordination for COPD readmissions. Hosp Pract. 2016;44(3):123–128. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2016.1210472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belanger M, Couillard S, Courteau J, et al. Eosinophil counts in first COPD hospitalizations: a comparison of health service utilization. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:3045–3054. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S170743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benzo R, Vickers K, Novotny PJ, et al. Health coaching and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease rehospitalization. A Randomized Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(6):672–680. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201512-2503OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernabeu-Mora R, Garcia-Guillamon G, Valera-Novella E, Gimenez-Gimenez LM, Escolar-Reina P, Medina-Mirapeix F. Frailty is a predictive factor of readmission within 90 days of hospitalization for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a longitudinal study. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2017;11(10):383–392. doi: 10.1177/1753465817726314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhatt SP, Wells JM, Iyer AS, et al. Results of a medicare bundled payments for care improvement initiative for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmissions. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(5):643–648. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201610-775BC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bishwakarma R, Zhang W, Kuo YF, Sharma G. Long-acting bronchodilators with or without inhaled corticosteroids and 30-day readmission in patients hospitalized for COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:477–486. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S122354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boeck L, Gencay M, Roth M, et al. Adenovirus-specific IgG maturation as a surrogate marker in acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2014;146(2):339–347. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boixeda R, Capdevila JA, Vicente V, et al. Gamma globulin fraction of the proteinogram and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Med Clin. 2017;149(3):107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2016.12.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bollu V, Ernst FR, Karafilidis J, Rajagopalan K, Robinson SB, Braman SS. Hospital readmissions following initiation of nebulized arformoterol tartrate or nebulized short-acting beta-agonists among inpatients treated for COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:631–639. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S52557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bollu V, Guerin A, Gauthier G, Hiscock R, Wu EQ. Readmission Risk in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: comparative study of nebulized beta2-agonists. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2017;4(1):33–41. doi: 10.1007/s40801-016-0097-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breyer-Kohansal R, Hartl S, Breyer MK, et al. The European COPD audit: adherence to guidelines, readmission risk and hospital care for acute exacerbations in Austria. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2019;131(5–6):97–103. doi: 10.1007/s00508-019-1441-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brownridge DJ, Zaidi STR. Retrospective audit of antimicrobial prescribing practices for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases in a large regional hospital. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017;42(3):301–305. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bucknall CE, Miller G, Lloyd SM, et al. Glasgow supported self-management trial (GSuST) for patients with moderate to severe COPD: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344(7849):e1060–e1060. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buhr RG, Jackson NJ, Dubinett SM, Kominski GF, Mangione CM, Ong MK. Factors associated with differential readmission diagnoses following acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Hospl Med. 2020;15(4):219–227. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buhr RG, Jackson NJ, Kominski GF, Dubinett SM, Ong MK, Mangione CM. Comorbidity and thirty-day hospital readmission odds in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a comparison of the Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidity indices. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):701. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4549-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Candrilli SD, Dhamane AD, Meyers JL, Kaila S. Factors associated with inpatient readmission among managed care enrollees with COPD. Hosp Pract. 2015;43(4):199–207. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2015.1085797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carneiro R, Sousa C, Pinto A, Almeida F, Oliveira JR, Rocha N. Risk factors for readmission after hospital discharge in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The role of quality of life indicators. Rev Port Pneumol. 2010;16(5):759–777. doi: 10.1016/S0873-2159(15)30070-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chan FW, Wong FY, Yam CH, et al. Risk factors of hospitalization and readmission of patients with COPD in Hong Kong population: analysis of hospital admission records. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11(1):186. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang C, Zhu H, Shen N, Han X, Chen Y, He B. Utility of the combination of serum highly-sensitive C-reactive protein level at discharge and a risk index in predicting readmission for acute exacerbation of COPD. J Bras Pneumol. 2014;40(5):495–503. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132014000500005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chawla H, Bulathsinghala C, Tejada JP, Wakefield D, ZuWallack R. Physical activity as a predictor of thirty-day hospital readmission after a discharge for a clinical exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(8):1203–1209. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201405-198OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen L, Chen S. Prediction of readmission in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease within one year after treatment and discharge. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen Y, Li Q, Johansen H. Age and sex variations in hospital readmissions for COPD associated with overall and cardiac comorbidity. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13(3):394–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen YJ, Narsavage GL. Factors related to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmission in Taiwan. West J Nurs Res. 2006;28(1):105–124. doi: 10.1177/0193945905282354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chu CM, Chan VL, Lin AWN, Wong IWY, Leung WS, Lai CKW. Readmission rates and life threatening events in COPD survivors treated with non-invasive ventilation for acute hypercapnic respiratory failure. Thorax. 2004;59(12):1020–1025. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.024307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chung LP, Winship P, Phung S, Lake F, Waterer G. Five-year outcome in COPD patients after their first episode of acute exacerbation treated with non-invasive ventilation. Respirology. 2010;15(7):1084–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01795.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coban Agca M, Aksoy E, Duman D, et al. Does eosinophilia and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio affect hospital re-admission in cases of COPD exacerbation? Tuberkuloz ve Toraks. 2017;65(4):282–290. doi: 10.5578/tt.57278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Collinsworth AW, Brown RM, James CS, Stanford RH, Alemayehu D, Priest EL. The impact of patient education and shared decision making on hospital readmissions for COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:1325–1332. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S154414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Connolly MJ, Lowe D, Anstey K, Hosker HSR, Pearson MG, Roberts CM. Admissions to hospital with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect of age related factors and service organisation. Thorax. 2006;61(10):843–848. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.054924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Conti G, Antonelli M, Navalesi P, et al. Noninvasive vs. conventional mechanical ventilation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after failure of medical treatment in the ward: a randomized trial. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(12):1701–1707. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1478-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cope K, Fowler L, Pogson Z. Developing a specialist-nurse-led ‘COPD in-reach service’. Br J Nurs. 2015;24(8):441–445. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2015.24.8.441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Couillard S, Larivee P, Courteau J, Vanasse A. Eosinophils in COPD exacerbations are associated with increased readmissions. Chest. 2017;151(2):366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coventry PA, Gemmell I, Todd CJ. Psychosocial risk factors for hospital readmission in COPD patients on early discharge services: a cohort study. BMC Polm. 2011;11:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Criner GJ, Jacobs MR, Zhao H, Marchetti N. Effects of roflumilast on rehospitalization and mortality in patients. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018;6(1):74–85. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.6.1.2018.0139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Crisafulli E, Guerrero M, Menendez R, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids do not influence the early inflammatory response and clinical presentation of hospitalized subjects with COPD exacerbation. Respir Care. 2014;59(10):1550–1559. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Crisafulli E, Torres A, Huerta A, et al. predicting in-hospital treatment failure (<= 7 days) in patients with COPD exacerbation using antibiotics and systemic steroids. COPD. 2016;13(1):82–92. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2015.1057276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Crisafulli E, Torres A, Huerta A, et al. C-reactive protein at discharge, diabetes mellitus and ≥1 hospitalization during previous year predict early readmission in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD. 2015;12(3):311–320. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2014.933954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dalal AA, Shah M, D’Souza AO, Crater GD. Rehospitalization risks and outcomes in COPD patients receiving maintenance pharmacotherapy. Respir Med. 2012;106(6):829–837. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.De Batlle J, Mendez M, Romieu I, et al. Cured meat consumption increases risk of readmission in COPD patients. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(3):555–560. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00116911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.De Jong YP, Uil SM, Grotjohan HP, Postma DS, Kerstjens HAM, Van Den Berg JWK. Oral or IV prednisolone in the treatment of COPD exacerbations: a randomized, controlled, double-blind study. Chest. 2007;132(6):1741–1747. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Miguel-Diez J, Jimenez-Garcia R, Hernandez-Barrera V, et al. Readmissions following an initial hospitalization by COPD exacerbation in Spain from 2006 to 2012. Respirology. 2016;21(3):489–496. doi: 10.1111/resp.12705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Deutz NE, Ziegler TR, Matheson EM, et al. Reduced mortality risk in malnourished hospitalized older adult patients with COPD treated with a specialized oral nutritional supplement: sub-group analysis of the NOURISH study. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(3):1388–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Duman D, Aksoy E, Agca MC, et al. The utility of inflammatory markers to predict readmissions and mortality in COPD cases with or without eosinophilia. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2469–2478. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S90330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Eaton T, Fergusson W, Kolbe J, Lewis CA, West T. Short-burst oxygen therapy for COPD patients: a 6-month randomised, controlled study. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(4):697–704. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00098805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eaton T, Young P, Fergusson W, et al. Does early pulmonary rehabilitation reduce acute health-care utilization in COPD patients admitted with an exacerbation? A randomized controlled study. Respirology. 2009;14(2):230–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01418.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ehsani H, Mohler MJ, Golden T, Toosizadeh N. Upper-extremity function prospectively predicts adverse discharge and all-cause COPD readmissions: a pilot study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:39–49. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S182802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Emtner MI, Arnardottir HR, Hallin R, Lindberg E, Janson C. Walking distance is a predictor of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2007;101(5):1037–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Eriksen N, Vestbo J. Management and survival of patients admitted with an exacerbation of COPD: comparison of two Danish patient cohorts. Clin Respir J. 2010;4(4):208–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-699X.2009.00177.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ernst P, Dah M, Chateau D, et al. Comparative effectiveness of fluoroquinolone antibiotic use in uncomplicated acute exacerbations of COPD: a multi-cohort study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:2939–2946. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S226324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Euceda G, Kong WT, Kapoor A, et al. The effects of a comprehensive care management program on readmission rates after acute exacerbation of COPD at a community-based academic hospital. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2018;5(3):185–192. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.5.3.2017.0177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fernandez-Garcia S, Represas-Represas C, Ruano-Ravina A, et al. Social and clinical predictors of short- and long-term readmission after a severe exacerbation of copd. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0229257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fu AZ, Sun SX, Huang X, Amin AN. Lower 30-day readmission rates with roflumilast treatment among patients hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:909–915. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S83082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ganapathy V, Stensland MD. Health resource utilization for inpatients with COPD treated with nebulized arformoterol or nebulized formoterol. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:1793–1801. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S134145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Garcia-Aymerich J, Farrero E, Felez MA, Izquierdo J, Marrades RM, Anto JM. Risk factors of readmission to hospital for a COPD exacerbation: a prospective study. Thorax. 2003;58(2):100–105. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.2.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Garcia-Aymerich J, Hernandez C, Alonso A, et al. Effects of an integrated care intervention on risk factors of COPD readmission. Respir Med. 2007;101(7):1462–1469. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Garcia-Pachon E, Baeza-Martinez C, Ruiz-Alcaraz S, Grau-Delgado J. Prediction of three-month readmission based on haematological parameters in patients with severe COPD exacerbation. Adv Respir Med. 2021;89(5):501–504. doi: 10.5603/ARM.a2021.0076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Garcia-Sanz MT, Martinez-Gestoso S, Calvo-Alvarez U, et al. Impact of hyponatremia on COPD exacerbation prognosis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):12. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gavish R, Levy A, Dekel OK, Karp E, Maimon N. The association between hospital readmission and pulmonologist follow-up visits in patients with COPD. Chest. 2015;148(2):375–381. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gay E, Desai S, McNeil D. A multidisciplinary intervention to improve care for high-risk COPD patients. Am J Med Qual. 2020;35(3):231–235. doi: 10.1177/1062860619865329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gentene AJ, Guido MR, Woolf B, et al. Multidisciplinary team utilizing pharmacists in multimodal, bundled care reduce chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospital readmission rates. J Pharm Pract. 2021;34(1):110–116. doi: 10.1177/0897190019889440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.George PP, Heng BH, Lim TK, et al. Evaluation of a disease management program for COPD using propensity matched control group. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(7):1661–1671. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.06.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gerber A, Moynihan C, Klim S, Ritchie P, Kelly AM. Compliance with a COPD bundle of care in an Australian emergency department: a cohort study. Clin Respir J. 2018;12(2):706–711. doi: 10.1111/crj.12583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gerrits CM, Herings RM, Leufkens HG, Lammers JW. N-acetylcysteine reduces the risk of re-hospitalisation among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2003;21(5):795–798. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00063402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ghanei M, Aslani J, Azizabadi-Farahani M, Assari S, Saadat SH. Logistic regression model to predict chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. Archiv Med Sci. 2007;3(4):360–366. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Giron R, Matesanz C, Garcia-Rio F, et al. Nutritional state during COPD exacerbation: clinical and prognostic implications. Ann Nutr Metab. 2009;54(1):52–58. doi: 10.1159/000205960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Glaser JB, El-Haddad H. Exploring novel medicare readmission risk variables in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients at high risk of readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(9):1288–1293. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201504-228OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gonzalez C, Servera E, Marin J. Importance of noninvasively measured respiratory muscle overload among the causes of hospital readmission of COPD patients. Chest. 2008;133(4):941–947. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Goto T, Faridi MK, Camargo CA, Hasegawa K. Time-varying readmission diagnoses during 30 days after hospitalization for COPD exacerbation. Med Care. 2018;56(8):673–678. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Goto T, Faridi MK, Gibo K, Camargo CA, Hasegawa K. Sex and racial/ethnic differences in the reason for 30-day readmission after COPD hospitalization. Respir Med. 2017;131:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.07.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]