Abstract

Adaptation to low levels of oxygen (hypoxia) is a universal biological feature across metazoans. However, the unique mechanisms how different species sense oxygen deprivation remain unresolved. Here, we functionally characterize a novel long noncoding RNA (lncRNA), LOC105369301, which we termed hypoxia-induced lncRNA for polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) stabilization (HILPS). HILPS exhibits appreciable basal expression exclusively in a wide variety of human normal and cancer cells and is robustly induced by hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α). HILPS binds to PLK1 and sequesters it from proteasomal degradation. Stabilized PLK1 directly phosphorylates HIF1α and enhances its stability, constituting a positive feed-forward circuit that reinforces oxygen sensing by HIF1α. HILPS depletion triggers catastrophic adaptation defect during hypoxia in both normal and cancer cells. These findings introduce a mechanism that underlies the HIF1α identity deeply interconnected with PLK1 integrity and identify the HILPS-PLK1-HIF1α pathway as a unique oxygen-sensing axis in the regulation of human physiological and pathogenic processes.

The HILPS-PLK1-HIF1α axis sustains global oxygen sensing in humans.

INTRODUCTION

Oxygen (O2) is an essential nutrient that serves as a substrate for cellular metabolism and bioenergetics. Organisms frequently encounter insufficient O2 supply (hypoxia) in a variety of physiological states including mammalian embryogenesis and hematopoiesis. Hypoxia is also a prominent feature of pathogenic events encountered in cancer, inflammation, and cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, O2 sensing represents a fundamental principle that underpins our understanding of metazoan evolution, development, physiology, and pathology.

Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) play a central role in regulation of O2 homeostasis in all metazoan species (1). Upon O2 deprivation, cells alter their gene expression primarily through the activation of HIF1α and HIF2α (2). HIF1α is expressed ubiquitously in all cells, while HIF2α exhibits restricted expressions only in certain tissues (3, 4). HIFs function as heterodimers consisting of the O2-labile α subunits and a stable β subunit (HIF1β, also called ARNT) (5, 6). During normoxia, HIFα subunits are polyubiquitylated by the von Hippel–Lindau protein (pVHL) and targeted for proteasomal degradation (7–9). pVHL binding is dependent on hydroxylation of specific proline residues within HIFα subunits by the prolyl hydroxylase PHD2 (10). Hypoxia prevents the HIFα hydroxylation and proteasomal degradation. As a result, HIFα subunits dimerize with HIF1β to form transcriptionally active complexes to cope with hypoxic stress and adaptive response (6, 11).

The HIF system is remarkably well conserved throughout evolution from the simplest known animal, the placozoan Tricoplax adhaerens, to the highest species, Homo sapiens (12). This ancestral oxygen-sensing pathway must have undertaken the evolutionary pressure to evolve into more sophisticated machinery in higher organisms, given that evolution of more advanced mammalian species is necessarily associated with higher variability and plasticity in managing oxygen tension. However, the unique mechanisms how human cells sense oxygen deprivation remain to be deciphered.

A very large proportion of human genome is transcribed as long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), a heterogeneous family of RNAs longer than 200 nucleotides (nt) lacking evident protein-coding capacity (13). Compared to the protein-coding genes, lncRNAs exhibit enormous diversity with respect to evolutionary conservation, usually expressing in a highly species-specific and tissue-restricted manner (14). Despite the notable prevalence in the transcriptome and relentless efforts to interrogate their functions, our current understanding of the vast majority of lncRNAs remains much limited. Notably, lncRNAs have emerged as essential regulators of a broad range of biological processes (15–19). The evolutionary diversity of lncRNAs makes them well suited to function as a unique checkpoint in regulation of biological processes in more advanced mammalian species.

In the current study, we set out to identify candidate lncRNAs essential for global regulation of O2 sensing in human. Our studies nominate hypoxia-induced lncRNA for PLK1 (polo-like kinase 1) stabilization (HILPS) as a core oxygen-responsive lncRNA in human genome and reveal unanticipated roles for a previously uncharacterized lncRNA, HILPS, and a canonical cell cycle kinase, PLK1, in control of HIF1α stability and hypoxia adaptation.

RESULTS

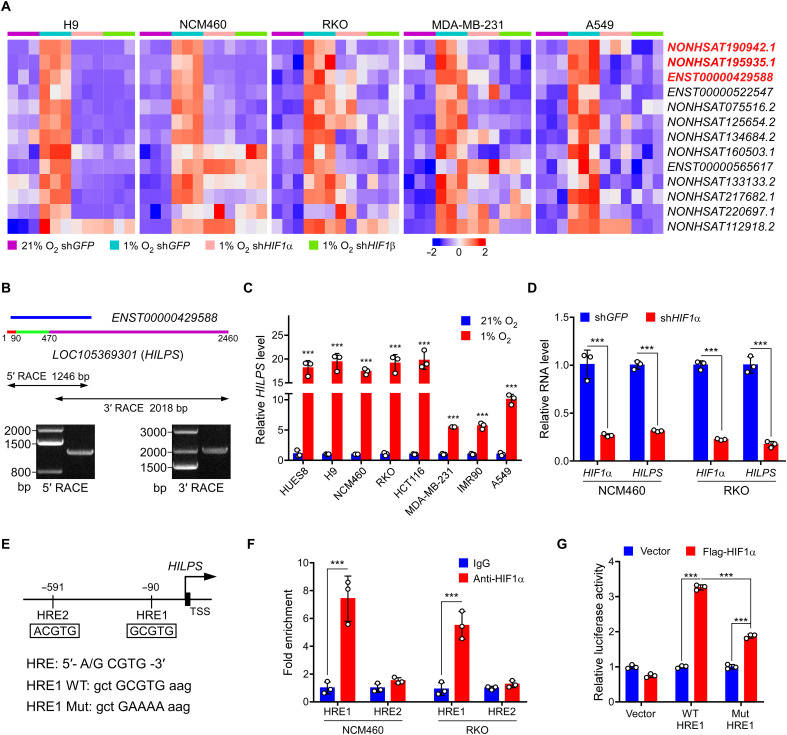

HILPS is a widely expressed lncRNA directly activated by HIF1α at hypoxia

To identify candidate hypoxia-responding lncRNAs with a widespread expression, we incubated human cells of different origins, including human embryonic stem cell (ESC) H9, normal colon epithelial cell NCM460, colorectal cancer cell RKO, breast cancer cell MDA-MB-231, and lung cancer cell A549 at 21% O2 (normoxia) and 1% O2 (hypoxia), and we respectively extracted RNAs for transcriptome analysis by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). As shown in Fig. 1A and fig. S1A, a set of 13 lncRNAs were commonly induced in all these cells at 1% O2. Given that HIF1α plays a central role in the transcriptional response to changes in O2 availability and is ubiquitously expressed in all cells (fig. S1B), we knocked down HIF1α or its binding partner, HIF1β, in parallel to identify lncRNAs whose expression is simultaneously affected upon deletion of either HIF1α or HIF1β. We comprehensively profiled the transcriptome and identified three top candidates, annotated as NONHSAT190942.1, NONHSAT195935.1, and ENST00000429588, respectively (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Characterization of HILPS, a novel human noncoding RNA globally activated by HIF1α at hypoxia.

(A) Heatmap presentation of 13 converged hypoxia-induced lncRNAs in five cell lines (fold change > 1.5, P < 0.05). Expression changes in the presence or absence of HIF1α/HIF1β are presented. Top three candidates are labeled in red. shGFP, control short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting GFP. (B) 5′ and 3′ RACE amplicons of HILPS using total RNA isolated from RKO cells exposed to 1% O2 for 24 hours as a template. Schematic of ENST00000429588 and full-length HILPS is illustrated at the top. Three exons of HILPS are marked in colors: exon 1 (1 to 90 nt) in red, exon 2 (91 to 470 nt) in green, and exon 3 (471 to 2460 nt) in purple. 5′ and 3′ RACE PCR amplicons and PCR products are shown in the middle and bottom. (C) qPCR analysis of HILPS in various cell lines exposed to 21% or 1% O2 for 24 hours. (D) qPCR analysis of HILPS in HIF1α-depleted NCM460 and RKO cells exposed to 1% O2 for 24 hours. (E) Schematic illustration of HIF1α binding sites on the HILPS locus. HRE1 consensus sequence mutations are shown as HRE1 mutant (Mut). TSS, transcription start site. (F) ChIP analysis of HIF1α binding to the HILPS locus in NCM460 and RKO cells. IgG, immunoglobulin G. (G) Luciferase reporter assay of the HILPS promoter construct containing HRE1 WT or mutant in the presence or absence of exogenous HIF1α in RKO cells. Data shown are means ± SD from biological triplicates. ***P < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test [(C), (D), and (F)] and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (G).

A blast search analysis revealed that NONHSAT195935.1 is actually a portion of the human GBE1 mRNA (corresponding to nucleotides 2067 to 2937 including part of the coding and 3′-untranslated sequences), which encodes glucan branching enzyme 1. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) verified that ENST00000429588, but not NONHSAT190942.1, was globally induced in multiple cell lines at hypoxia (fig. S1C). Of particular interest, ENST00000429588 is located within a locus annotated as LOC105369301 with poor characterization (Fig. 1B), which attracted our attention for a further comprehensive investigation. We performed 5′ and 3′ RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) assays in RKO, H9, NCM460, and MDA-MB-231 cells and identified a specific 2460-nt full-length transcript harboring three exons with a canonical polyadenylation signal at the 3′ end (Fig. 1B and fig. S1, D and E). We therefore termed this poorly characterized lncRNA HILPS based on the following mechanistic studies (see below for more details). Because lncRNAs may encode peptides, we analyzed the coding potential of HILPS using Coding Potential Calculator 2 (CPC 2) (20) and revealed that HILPS exhibits even a lower coding potential than the other well-characterized lncRNAs XIST and NORAD (fig. S1F). HILPS also lacks the potential to encode any recognizable protein domains based on a BLASTX analysis of all possible reading frames. Vertebrate Multiz Alignment & Conservation database analysis from University of California, Santa Cruz showed that HILPS is a lncRNA uniquely expressed in humans with poor evolutionary conservation.

We then assessed the hypoxia induction of HILPS and confirmed that it was significantly up-regulated in a number of human cell lines (Fig. 1C). Again, HIF1α or HIF1β knockdown diminished the expression of HILPS (Fig. 1D and fig. S1G). NCM460 and A549 cells also exhibited detectable HIF2α expression at hypoxia (fig. S1B). We then performed HIF2α knockdown in NCM460 cells and found that HIF2α depletion inhibited HILPS expression, suggesting that HILPS is transcriptionally activated by both HIFα subunits (fig. S1H). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) showed that HILPS was predominantly localized in the nucleus with some signals in the cytoplasm (fig. S2). We analyzed the genomic sequence upstream of HILPS and identified two putative hypoxia-responsive elements [HRE1, −90 base pairs (bp); HRE2, −591 bp], 5′-A/GCGTG-3′, located within the HILPS promoter (Fig. 1E). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay revealed a marked increase in HIF1α recruitment to HRE1, but not HRE2 (Fig. 1F). DNA sequences containing wild-type (WT) or mutant HRE1 were then cloned into a luciferase reporter construct. Reporter expression from the WT, but not the mutant reporter, was markedly induced upon HIF1α overexpression in RKO cells (Fig. 1G), suggesting that HRE1 confers HIF1α-dependent transcriptional activity. Collectively, these data demonstrate that HILPS is a direct HIF1α target expressed in multiple human cells.

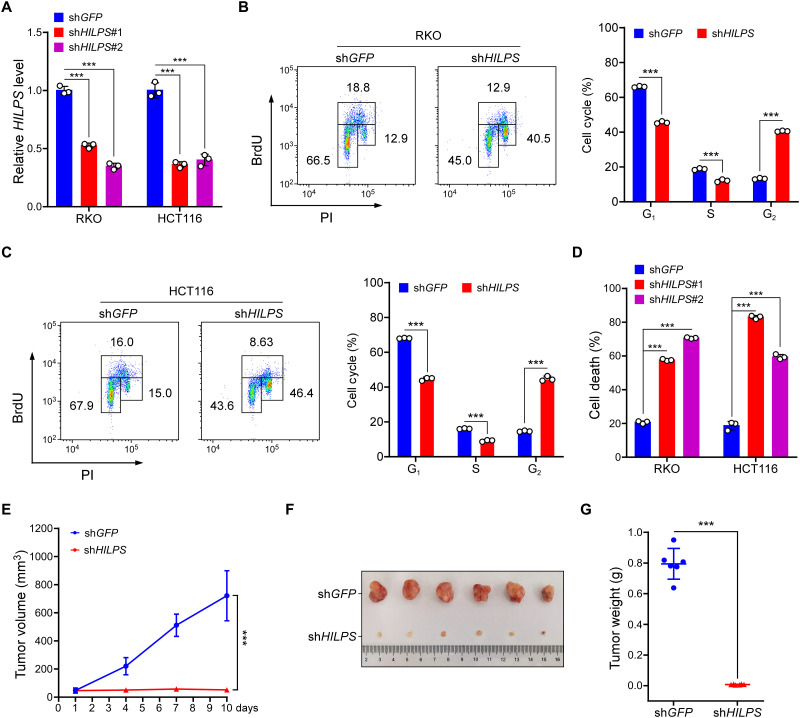

HILPS is required for tumor cell cycle progression and cell survival at hypoxia

Hypoxia is a common feature of solid tumors, which contributes to aggressive tumor phenotypes. To evaluate the biological impact of HILPS on human tumor cells, we knocked down HILPS with two independent short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) in RKO and HCT116 cells (Fig. 2A). We then assessed cell cycle progression of these cells by 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation. Notably, depletion of HILPS caused a significant accumulation of RKO and HCT116 cells in G2 phase, with a corresponding decrease in the percentage of cells in G1 and S phases (Fig. 2, B and C), supporting that HILPS maintains proper cell cycle progression at hypoxia. HILPS depletion also induced robust apoptotic RKO and HCT116 cell death during hypoxia (Fig. 2D). Hence, HILPS ablation almost completely inhibited HCT116 xenograft tumor formation (Fig. 2, E to G), supporting an essential role of HILPS in tumor growth in vivo.

Fig. 2. HILPS sustains colorectal cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo.

(A) qPCR analysis of HILPS in RKO and HCT116 cells expressing HILPS shRNA. Cells were exposed to 1% O2 for 24 hours. (B and C) Representative BrdU incorporation plots (left) and quantification (right) from RKO (B) and HCT116 (C) cells exposed to 1% O2 for 24 hours. PI, propidium iodide. (D) Cell death analysis of HILPS-depleted RKO and HCT116 cells exposed to 1% O2 for 48 hours. (E) Tumor growth of HILPS-depleted HCT116 xenografts (n = 6 in each group). x axis represents the time frame after engraftment. (F and G) Images of HCT116 xenograft tumors with or without HILPS depletion. Tumors were dissected and retrieved 2 weeks after engraftment (F). Tumor weight quantifications are shown in (G). Data shown are means ± SD from biological triplicates. ***P < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test [(B), (C), (E), and (G)], one-way ANOVA [(A) and (D)].

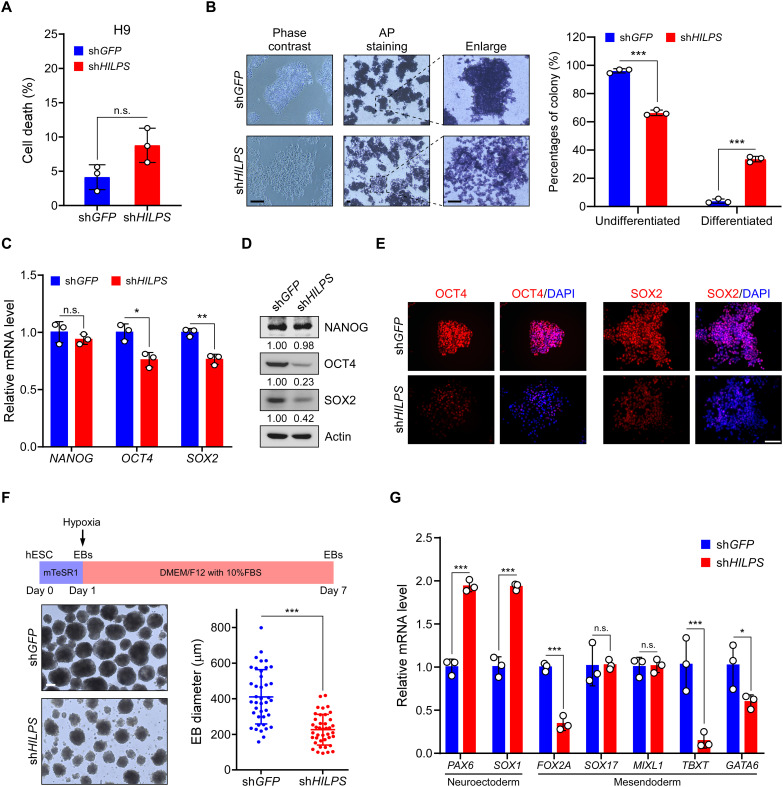

HILPS sustains pluripotency of human ESCs

Normal mammalian development occurs in a hypoxic environment, and hypoxia activates genes responsible for aspects of developmental morphogenesis (21). We thus exploited the H9 cells as a model system to investigate potential roles of HILPS in normal settings. Depletion of HILPS in H9 cells caused a slight increase (although not statistically significant) in apoptotic cell death upon hypoxia treatment (Fig. 3A). Compared with the control counterpart, colonies derived from HILPS-depleted H9 cells were morphologically flat and loose at hypoxia (Fig. 3B) and displayed much weaker alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining (Fig. 3B), a characteristic feature of pluripotency (22). In line with these findings, knockdown of HILPS significantly decreased the mRNA and protein expression of pluripotent marker POU domain class 5 homeobox 1 (POU5F1, also known as OCT4) and SRY-box transcription factor 2 (SOX2) (Fig. 3, C and D). Immunofluorescence staining further confirmed that inhibition of HILPS expression led to profound OCT4 and SOX2 reduction in live cells (Fig. 3E). We next performed embryoid body (EB) formation assay to mimic early embryonic development in vitro with an aim to investigate the potential roles of HILPS in human ESC differentiation. Notably, EBs derived from HILPS-deficient H9 cells were markedly smaller than those from the control ones (Fig. 3F). HILPS-depletion led to increased expression of neuroectoderm marker genes (PAX6 and SOX1), accompanied by down-regulation of some of the representative mesendoderm markers (FOXA2, TBXT, and GATA6) (Fig. 3G). These data indicate that HILPS knockdown favors a neuroectoderm trajectory and blocks the development of mesendoderm lineage, supporting an essential role of HILPS in hypoxia regulation of pluripotency of human ESCs.

Fig. 3. HILPS maintains pluripotency of human ESCs at hypoxia.

(A) Cell death analysis of HILPS-depleted H9 cells exposed to 1% O2 for 48 hours. (B) Representative images showing the morphology (left), AP staining (middle; two columns), and percentages of differentiated (AP-negative)/undifferentiated (AP-positive) colonies (right) of HILPS-depleted H9 cells exposed to 1% O2 for 48 hours. Scale bars, 200 μm. (C and D) qPCR analysis (C) and immunoblots (D) of indicated pluripotency marker expression in HILPS-depleted H9 cells exposed to 1% O2 for 24 hours. (E) Representative images showing immunofluorescence staining of OCT4 and SOX2 in HILPS-depleted H9 cells exposed to 1% O2 for 24 hours. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining was used to locate cell nucleus. Scale bar, 100 μm. (F) Schematic representation of EB differentiation of human ESCs exposed to 1% O2 for 7 days (top). Bright-field images of HILPS-depleted EBs at day 7 in suspension culture under 1% O2 (bottom left). Scale bar, 200 μm. Scatter graph displays the mean diameter of 40 EBs randomly selected from H9 cells with or without HILPS depletion (bottom right). (G) qPCR analysis of lineage-specific marker (neuroectoderm and mesendoderm) expression in HILPS-depleted EBs exposed to 1% O2 on day 7. Data shown are means ± SD from biological triplicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. n.s., no significance.

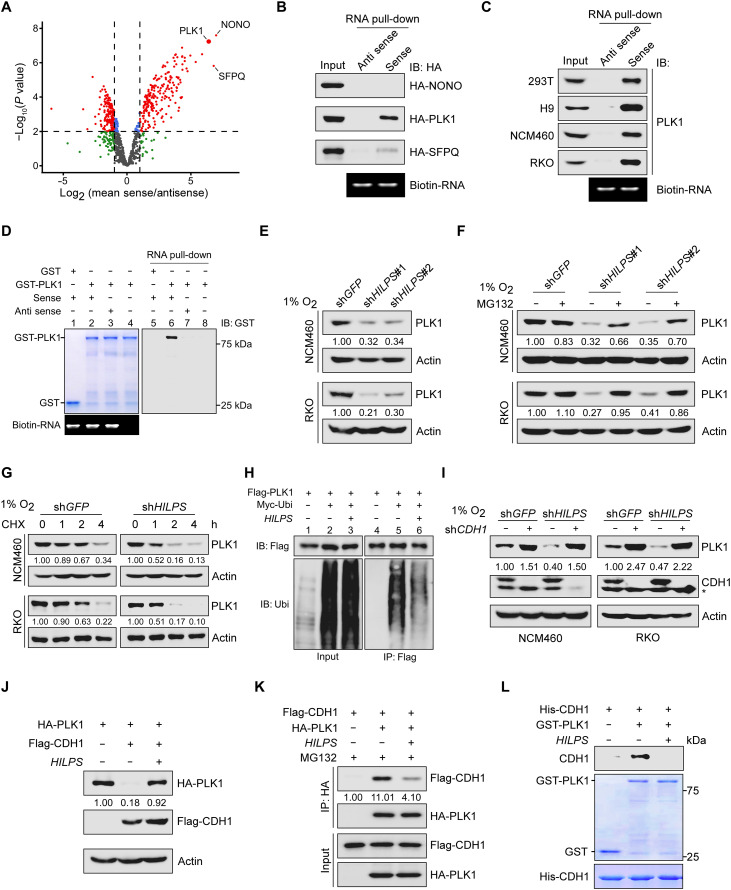

HILPS interacts with PLK1 and enhances PLK1 stability

lncRNAs frequently exert their biological functions through interacting with specific proteins (23). To dissect the molecular mechanisms whereby HILPS regulates hypoxia adaptation, we conducted RNA pull-down in combination with mass spectrometry (MS) analysis to identify HILPS-interacting proteins. Pull-down of antisense HILPS was used as a negative control. Among 206 proteins that potentially bind to HILPS, we selected the top 3 candidates, non-POU domain–containing octamer-binding protein (NONO), PLK1, and splicing factor proline and glutamine rich (SFPQ), for further validation (Fig. 4A). Notably, HILPS, but not the corresponding antisense control, strongly bound to PLK1 when it was ectopically expressed in 293T cells (Fig. 4B). Interaction between HILPS and endogenous PLK1 was further confirmed in 293T, H9, NCM460, and RKO cells (Fig. 4C). We next performed in vitro RNA pull-down assay and found that biotin-HILPS–conjugated streptavidin beads, not the antisense counterpart, specifically pulled down recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST)–PLK1 (Fig. 4D, compare lane 6 with lane 7), consolidating a direct interaction between HILPS and PLK1. We then constructed a series of HILPS deletion mutants to map the PLK1-binding region. The results from in vitro binding assays showed that PLK1 primarily interacted with the exon 2 (a region spanning nucleotides 91 to 470) within HILPS (fig. S3A).

Fig. 4. HILPS binds to PLK1 and enhances PLK1 stability.

(A) Volcano plots showing HILPS interacting proteins pulled down from 293T cells exposed to 1% O2 using biotin-labeled HILPS. Proteins significantly enriched (fold change > 2 and P < 0.01) from three independent experiments are displayed as red dots. (B) Biotin-labeled HILPS pull-down assay using 293T cell lysates with respective hemagglutinin (HA)–tagged protein expression. IB, immunoblot. (C) Biotin-labeled HILPS pull-down assay to detect endogenous PLK1 in 1% O2-treated cells. (D) In vitro RNA pull-down assay using biotin-labeled HILPS and recombinant GST-PLK1. (E) Immunoblots of PLK1 in HILPS-depleted NCM460 and RKO cells exposed to 1% O2. (F) Immunoblots of PLK1 in HILPS-depleted NCM460 and RKO cells treated with MG132 (10 μM) for 6 hours before harvest. (G) Time-course analysis of PLK1 degradation. HILPS-depleted NCM460 and RKO cells were cultured in 1% O2, treated with cycloheximide (CHX; 100 μg/ml) and harvested at the indicated time points, followed by immunoblotting of PLK1. (H) Analysis of PLK1 polyubiquitination in the presence or absence of HILPS in 293T cells. (I) Immunoblots of PLK1 and CDH1 in 1% O2-cultured NCM460 and RKO cells expressing shRNA targeting HILPS and/or CDH1. Asterisk denotes a nonspecific band detected by CDH1 antibody. (J) Immunoblots of indicated proteins in 293T cells transfected with HA-PLK1, Flag-CDH1, and/or HILPS. (K) Co-IP to detect protein interaction between PLK1 and CDH1 in the absence or presence of HILPS. 293T cells were treated with MG132 (10 μM) for 6 hours before harvest. (L) In vitro protein binding assay to detect PLK1-CDH1 interaction in the absence or presence of in vitro transcribed HILPS.

We noticed that HILPS depletion by shRNA greatly reduced the PLK1 protein abundance without a significant change in mRNA expression (Fig. 4E and fig. S3, B and C). As administration of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 efficiently rescued PLK1 down-regulation upon HILPS ablation (Fig. 4F and fig. S3D), we reasoned that HILPS depletion induced proteasome-mediated PLK1 degradation. Time-course analysis revealed that depletion of HILPS significantly shortened the half-life of endogenous PLK1 in RKO, NCM460, and H9 cells (Fig. 4G and fig. S3, E and F), arguing that HILPS regulates PLK1 through enhancing protein stability. Consistent with these findings, enforced expression of HILPS markedly decreased PLK1 polyubiquitination (Fig. 4H). CDH1 (anaphase promoting complex or cyclosome activator protein CDH1, APC/CCDH1) is the primary E3 ligase responsible for polyubiquitylation and proteasome-mediated degradation of PLK1 (24, 25). Knockdown of CDH1 in RKO, NCM460, and H9 cells abolished HILPS depletion–induced PLK1 loss (Fig. 4I and fig. S3G), while ectopic expression of HILPS counteracted the CDH1 induction of PLK1 degradation (Fig. 4J and fig. S3H). Enforced HILPS expression in 293T cells efficiently disrupted the interaction between CDH1 and PLK1 (Fig. 4K). Note that HILPS exhibited an undetectable interaction with the WT CDH1 or its constitutive phosphorylation mutant (fig. S3I). As a further support, administration of in vitro transcribed HILPS efficiently disrupted the interaction of recombinant CDH1 and PLK1 proteins (Fig. 4L). Domain mapping revealed that deletion of amino acids 304 to 409 spanning the D-box–disrupted PLK1 interaction with HILPS (fig. S3J), supporting that HILPS directly interacts with PLK1 near its D-box region and promotes PLK1 stabilization via sequestering it from CDH1 recognition.

HILPS sustains HIF1α-dependent transcriptional programs via PLK1 regulation of HIF1α stabilization

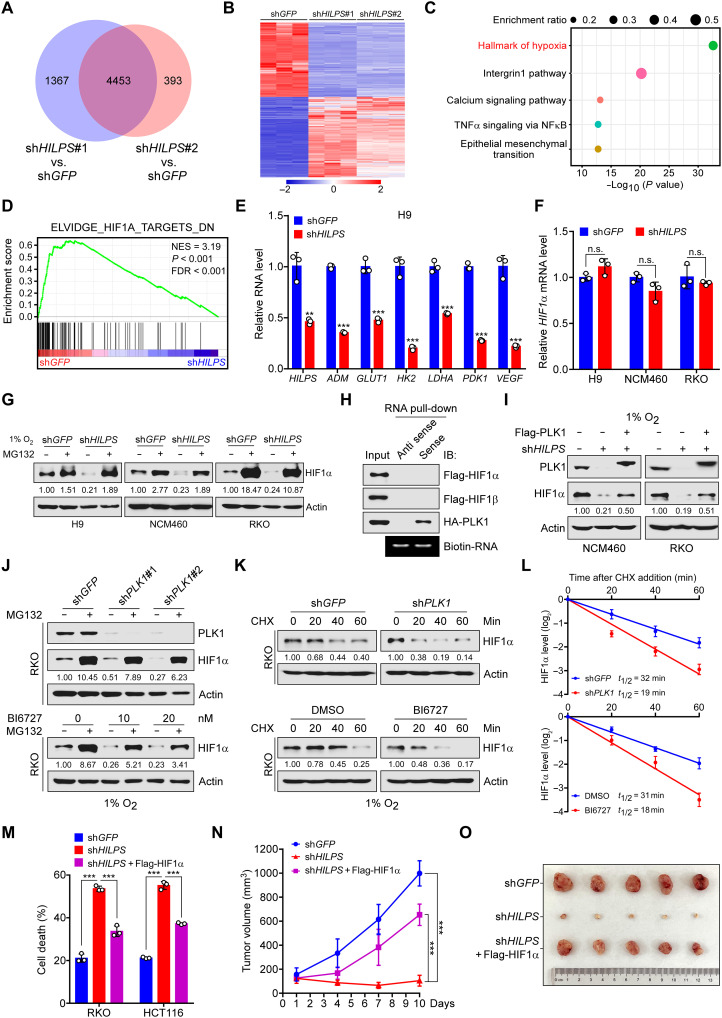

To explore the molecular mechanisms underlying HILPS-mediated oxygen sensing, we profiled HILPS-depleted (shHILPS#1 and shHILPS#2) versus mock-depleted (shGFP) H9 cells by genome-wide transcriptional profiling coupled with pathway enrichment analysis. After normalizing the gene expression to the control group, we identified a common set of 4453 genes whose expression was significantly changed upon HILPS knockdown by both shRNAs (Fig. 5, A and B). Notably, pathway enrichment analysis using these overlapped genes showed that HILPS was implicated in pathways robustly related to “hallmark of hypoxia” (Fig. 5C). We interrogated our gene expression profile with published, validated hypoxia-regulated gene signatures for gene set enrichment analysis (26, 27) and found that HILPS depletion resulted in significant down-regulation of HIF1α signature genes (Fig. 5D). Down-regulation of canonical HIF1α targets upon HILPS depletion was confirmed by qPCR in multiple human cell lines subjected to hypoxia treatment (Fig. 5E and fig. S4A), corroborating a vital role of HILPS in sustaining HIF1α transcriptional programs.

Fig. 5. Inhibition of HILPS-PLK1 axis induces HIF1α degradation and impairs HIF1α signature gene expression.

(A to C) Venn diagram of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) resulting from 1% O2-cultured H9 cells expressing shHILPS#1 or shHILPS#2 (A). Heatmap presentation (B) and enrichment analysis (C) of 4453 merged DEG in (A). Pathway enrichment was analyzed by Metascape (www.metascape.org). TNFα, tumor necrosis factor–α; NFκB, nuclear factor κB. (D) Gene set enrichment analysis of HIF1α target gene sets in the expression profiles of H9 cells expressing HILPS shRNA#1 (software.broadinstitute.org/gsea). NES, normalized enrichment score; FDR, false discovery rate. (E) qPCR analysis of HIF1α target genes in HILPS-depleted H9 cells exposed to 1% O2. (F) qPCR analysis of HIF1α mRNA in HILPS-depleted cells exposed to 1% O2. (G) Immunoblots of HIF1α in HILPS-depleted cells treated with MG132 (10 μM) for 6 hours before harvest. (H) Biotin-labeled HILPS pull-down assay using lysates from 293T cells expressing tagged proteins. (I) Immunoblots of HIF1α and PLK1 in HILPS-depleted cells with or without Flag-PLK1 overexpression. (J) Immunoblots of HIF1α and PLK1 in PLK1-depleted (top) or BI6727-treated (bottom) RKO cells subjected to 1% O2 exposure. (K and L) Time-course analysis of HIF1α degradation in PLK1-depleted (top) or BI6727-treated (bottom) RKO cells subjected to 1% O2 exposure. HIF1α was analyzed by immunoblotting (K) and quantified as shown in (L). (M) Cell death analysis of HILPS-depleted cells cultured in 1% O2 with or without ectopic HIF1α. (N and O) Tumor growth of HILPS-depleted HCT116 xenografts with or without ectopic HIF1α (n = 5) (N). Tumors were dissected 2 weeks after engraftment (O). Data shown are means ± SD from biological triplicates. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test [(E) and (F)] and one-way ANOVA [(M) and (N)].

Notably, HILPS deficiency reduced HIF1α protein abundance, which was efficiently rescued by MG132, without affecting mRNA levels (Fig. 5, F and G), suggesting that HILPS is implicated in regulation of HIF1α stability. Given that HILPS was not directly associated with HIF1α or HIF1β and ectopically expressed PLK1 attenuated the HIF1α reduction resulting from HILPS knockdown (Fig. 5, H and I), we reasoned that HILPS may indirectly regulate HIF1α via sustaining PLK1 stabilization. In support of this notion, depletion of PLK1 by specific shRNAs led to a marked decline in HIF1α protein abundance, which can also be efficiently reversed upon administration of MG132 (Fig. 5J and fig. S4B, top). Time-course experiments revealed that abrogation of PLK1 significantly reduced the half-life of endogenous HIF1α (Fig. 5, K and L; and fig. S4, C and D, top), supporting that PLK1 depletion promotes HIF1α proteasomal degradation. Pharmacological inhibition of PLK1 kinase activity by the small chemical inhibitor BI6727 similarly diminished HIF1α expression, which was also rescued by MG132 (Fig. 5J and fig. S4B, bottom) and shortened the HIF1α half-life (Fig. 5, K and L; and fig. S4, C and D, bottom), arguing that PLK1 kinase activity is required for sustaining HIF1α protein stability.

HIF1α is a master regulator of glycolysis in response to hypoxia exposure (28). We then performed isotopomer distribution analysis in H9 cells to assess glycolytic flux using 13C6 glucose (all six carbons are 13C-labeled, M6) as the tracer, which produces glycolytic intermediates containing 13C atoms. As expected, HILPS depletion significantly reduced the isotopomer enrichment of representative glycolytic intermediates at hypoxia, including M6 fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, M3 dihydroxyacetone phosphate, M3 3-phosphoglycerate/2-phosphoglycerate, and M3 phosphoenolpyruvate (fig. S4E). In support of these observations, HILPS depletion caused a significant inhibition of glucose consumption and lactate production (fig. S4F). Moreover, enforced expression of HIF1α in HILPS-knockdown RKO and HCT116 cells significantly rescued hypoxia-induced cell death in vitro (Fig. 5M and fig. S4G) and markedly reversed growth inhibition of HCT116 xenograft tumors in vivo (Fig. 5, N and O, and fig. S4H). These findings demonstrate that HILPS, once transcriptionally activated by HIF1α, in turn promotes HIF1α stabilization in a PLK1 kinase–dependent manner.

PLK1-directed HIF1α threonine-218 phosphorylation is critical for HIF1α stabilization

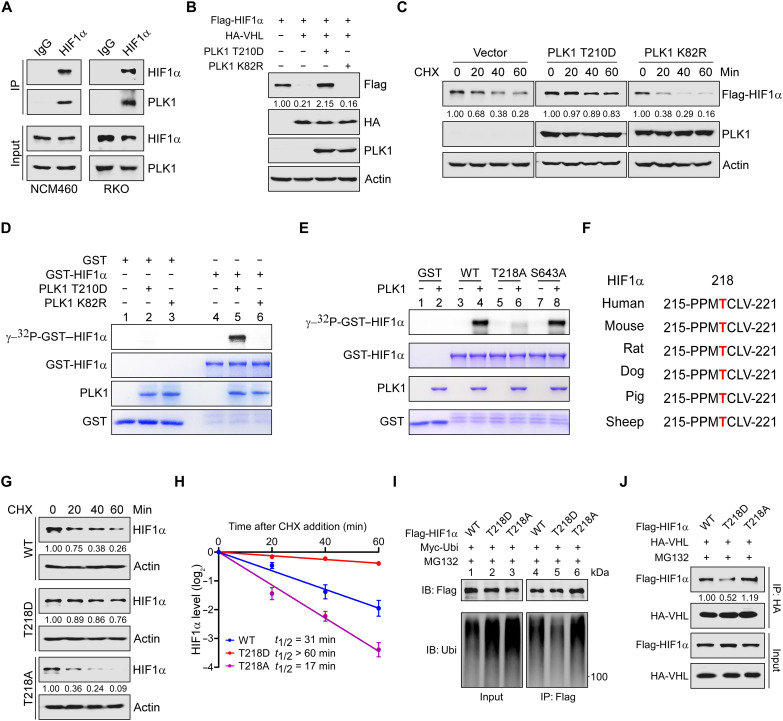

The implication of PLK1 in modulating HIF1α stability prompted us to examine their interaction. We coexpressed hemagglutinin (HA)–tagged PLK1 with Flag-tagged HIF1α in 293T cells. Immunoprecipitation (IP) with Flag-tagged antibody showed that PLK1 specifically binds to HIF1α (fig. S5A), which was confirmed in reciprocal co-IPs with HA-tagged antibody (fig. S5A), suggesting a selective association between PLK1 and HIF1α proteins. In further support of HIF1α being a PLK1 binding partner, we identified that endogenous HIF1α was present in PLK1 immunoprecipitates (Fig. 6A). Co-IP with respective epitope-tagged HIF1α or PLK1 fragments revealed the HIF1α oxygen-dependent degradation domain (amino acids 330 to 530) and the PLK1 kinase domain (amino acids 1 to 345) as regions critical for the direct protein-protein interaction (fig. S5, B and C).

Fig. 6. PLK1 phosphorylates HIF1α T218 and sustains HIF1α stabilization.

(A) Co-IP of endogenous HIF1α and PLK1 using lysates of 1% O2-cultured NCM460 and RKO cells. (B) Immunoblots of indicated proteins in 293T cells expressing Flag-HIF1α, HA-VHL, and/or PLK1 (T210D and K82R). (C) Time-course analysis of Flag-HIF1α in 293T cells coexpressing PLK1 T210D or K82R. Flag-HIF1α protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting. (D) In vitro kinase assay of recombinant GST-HIF1α catalyzed by Flag-tagged PLK1 T210D or K82R purified from 293T cells. Phosphorylated proteins were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and visualized by autoradiography. Loading controls were shown as Coomassie blue staining in the bottom panels. (E) In vitro kinase analysis of recombinant GST-HIF1α. Active human WT PLK1 proteins were incubated with GST-HIF1α (WT, T218A, or S463A) for kinase reaction. HIF1α phosphorylation signals were detected as in (D). (F) Peptide sequence alignment of HIF1α (amino acid 215 to 221) in multiple species. The threonine-218 residue is highlighted in red. (G and H) Time-course analysis of Flag-HIF1α WT or mutants (T218D or T218A) degradation in 293T cells by immunoblot (G) with quantification shown in (H). (I) Analysis of Flag-HIF1α WT or mutants (T218D or T218A) polyubiquitylation. Myc-tagged ubiquitin was cotransfected with Flag-HIF1α (WT or mutants) into 293T cells, and the resulting cell lysates were subjected to co-IP, followed by polyubiquitylation detection. (J) Co-IP of Flag-HIF1α (WT or mutants) and HA-VHL using 293T cell lysate with epitope-tagged proteins expression. MG132 (10 μM) was added to prevent HIF1α degradation. Data shown are means ± SD from biological triplicates.

As PLK1 kinase activity is required for HIF1α stabilization, we surmise that PLK1 regulates HIF1α through direct phosphorylation. Ectopic expression of the constitutively active PLK1 mutant (PLK1-T210D) counteracted VHL-mediated HIF1α degradation, while the kinase inactive mutant (PLK1-K82R) exhibited little effect (Fig. 6B). In support of this notion, PLK1-T210D significantly extended the half-life of exogenous HIF1α, while PLK1 K82R shortened the half-life (Fig. 6C and fig. S5D).

We then performed in vitro kinase assays to explore whether HIF1α is phosphorylated directly by PLK1. As expected, the active PLK1 (PLK1-T210D), but not its kinase-inactive form (PLK1-K82R), phosphorylated GST-HIF1α in vitro (Fig. 6D, compare lane 5 with lane 6). No phosphorylation of GST alone was detected (Fig. 6D, compare lanes 1 to 3 with lane 6). To identify the potential phosphorylation site(s), we repeated the in vitro kinase assay using PLK1-T210D, recombinant GST-HIF1α, and cold adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP). A kinase assay using PLK1-K82R was included as a control. Subsequent MS analysis revealed that threonine-218 (T218) and serine-643 (S643) within HIF1α were potential sites selectively phosphorylated by PLK1 T210D (fig. S5, E and F). Notably, mutations of threonine-218, but not serine-643, to alanine abolished the phosphorylation signal (Fig. 6E, compare lanes 6 and 8 with lane 4), suggesting that T218 within HIF1α is the major sites subjected to PLK1 phosphorylation.

The T218 phosphorylation residue, as well as the surrounding amino acids, is highly conserved among vertebrates (Fig. 6F), indicating that its phosphorylation may have an evolutionarily conserved role in regulation of HIF1α protein stability. Therefore, we constructed HIF1α nonphosphorylatable alanine mutant (T218A) and phosphomimetic aspartic acid mutant (T218D), respectively, and performed a series of cycloheximide chase experiments to estimate the half-life of these mutant proteins. As expected, mutation of threonine-218 to aspartic acid (to mimic constitutive phosphorylation) extended the half-life of HIF1α, whereas the respective mutation to alanine profoundly shortened its half-life (Fig. 6, G and H), suggesting that phosphorylation inhibits the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of HIF1α. In line with these observations, we found that a notable decrease in HIF1α-T218D polyubiquitination compared to WT HIF1α and its T218A mutant (Fig. 6I, compare lane 5 with lanes 4 and 6), suggesting that a decrease in polyubiquitination might be the primary mechanism responsible for HIF1α stabilization upon PLK1 activation.

Under well‑oxygenated conditions, HIF1α becomes hydroxylated at one (or both) of two highly conserved prolyl residues (proline-402 and/or proline-564) primarily by PHD2. Hydroxylation of either of these prolyl residues generates a binding site for the pVHL ubiquitin E3 ligase. We thus evaluated the binding of various HIF1α phosphorylation mutants to PHD2 and pVHL, respectively, and found a notable decrease in HIF1α-T218D interaction with pVHL compared to that of WT HIF1α and its T218A mutant (Fig. 6J), whereas neither mutation affected HIF1α binding to PHD2 (fig. S5G). Together, these results suggest that, once stabilized by HILPS, PLK1 directly phosphorylates HIF1α at T218, which inhibits HIF1α polyubiquitination by pVHL and subsequent degradation by proteasome.

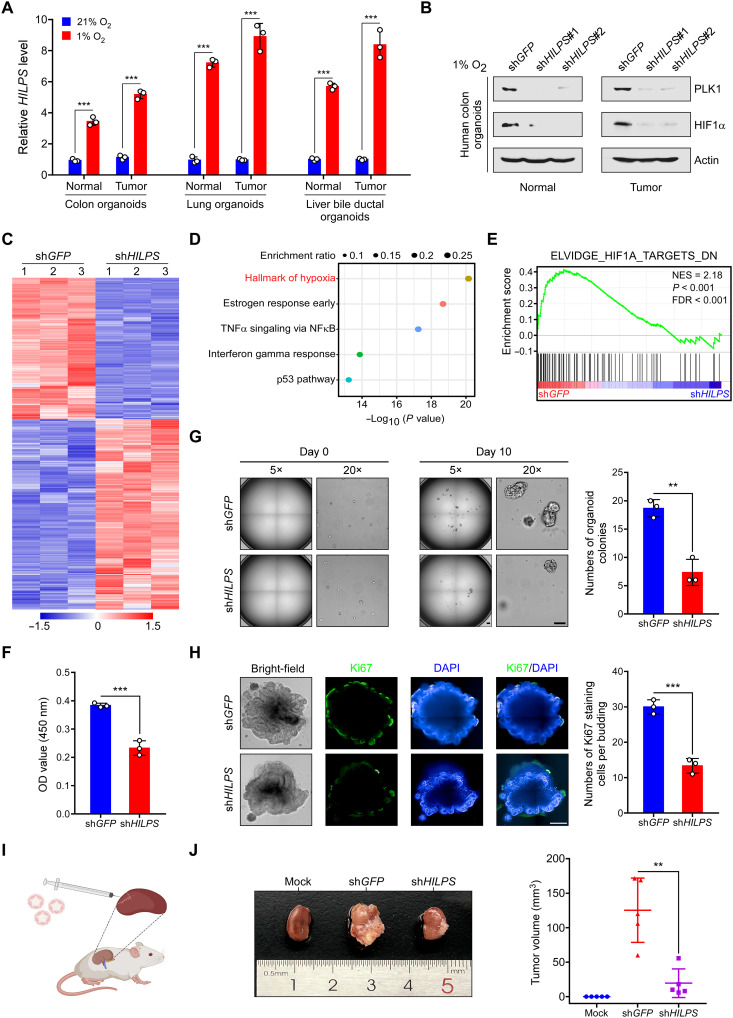

HILPS is essential for hypoxic adaptation of human tumor organoids

As HILPS is a unique lncRNA in human, it is impractical to perform functional characterization and mechanistic investigation in model organisms. Instead, human patient-derived organoids have enabled disease modeling ex vivo with precision as these three-dimensional cultures maintain key features from their parental counterparts (29, 30). We thus assessed HILPS in human organoids and found that it was consistently induced when multiple human normal and tumor organoids, including those from the colon, lung and liver bile ducts, were subjected to hypoxia treatment (Fig. 7A and fig. S6, A and B). Moreover, depletion of HILPS markedly decreased PLK1 and HIF1α protein abundance in representative organoids from human normal colon tissue and colorectal cancer (Fig. 7B). We then performed transcriptomic analysis in hypoxia-treated colorectal cancer organoids with or without HILPS knockdown. Consistent with our prior findings, pathway enrichment of differentially expressed genes revealed the hallmark of hypoxia (Fig. 7, C and D) and HILPS depletion resulted in significant down-regulation of HIF1α signature genes in hypoxia-treated organoids (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 7. HILPS inhibition impedes human organoid growth under hypoxia.

(A) qPCR analysis of HILPS in human normal and tumor organoids exposed to 21 or 1% O2 for 24 hours. (B) Immunoblots of PLK1 and HIF1α in 1% O2-treated human organoids derived from normal colon tissue and colorectal cancer upon HILPS depletion. (C to E) Heatmap presentation of all DEG upon HILPS depletion by shRNA#1 in colorectal cancer organoids exposed to 1% O2 (C). Pathway enrichment analysis of DEG by Metascape (D). Gene set enrichment analysis of HIF1α target gene sets in the expression profiles of HILPS-depleted colorectal cancer organoids (E). (F) Proliferation of colorectal cancer organoids exposed to 1% O2 upon HILPS depletion. Organoid proliferation was assessed by CCK-8. OD, optical density. (G) Representative bright field images of colorectal cancer organoids cultured under 1% O2 upon HILPS depletion (left). Scale bars, 200 μm. Quantitation of viable organoid colonies is shown on the right. (H) Representative images showing bright-field view and immunofluorescence staining of Ki67 in HILPS-depleted colorectal cancer organoids cultured under 1% O2 (left). DAPI was stained to visualize the organoids in dark field. Scale bar, 200 μm. Quantitation of Ki67 positive staining cells per budding are presented (right). (I) Schematic depicting patient-derived organoid–based xenograft model. (J) Representative images of colorectal cancer organoid–based tumors in the subrenal capsule with or without HILPS depletion (left) and measurement of tumor volumes (n = 5) (right). Data shown are means ± SD from biological triplicates. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001; unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test [(A), (F), (G), and (H)] and one-way ANOVA (J).

In particular, when the same numbers of colorectal cancer organoids were seeded in culture plates, knockdown of HILPS profoundly compromised the survival and growth of these organoids at 1% O2 compared to control counterparts (Fig. 7F). HILPS depletion also significantly impaired colony-forming capacity of the colorectal cancer cells in organoids (Fig. 7G). Knockdown of PLK1 exhibited similar effect (fig. S6C), suggesting that PLK1 depletion phenocopies HILPS knockdown. Immunofluorescence staining confirmed that loss of HILPS expression suppressed cell proliferation as evidenced by weaker Ki67 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen staining (Fig. 7H and fig. S6D). Depletion of HILPS also inhibited the expression of SOX9 (fig. S6E), a representative stemness marker of colorectal cancer. We then used patient-derived organoid–based xenograft model to address whether HILPS indeed affected tumor formation in vivo. Representative colorectal cancer organoids were xenotransplanted into the kidney subcapsules of immunocompromised NSG (nonobese diabetic–PrkdcscidIl2rgem1/Smoc) mice (Fig. 7I). Again, organoids expressing the control shRNA successfully gave rise to tumors in the kidney, whereas HILPS knockdown resulted in markedly less engraftment (Fig. 7J). These results provide strong evidence supporting that HILPS regulates hypoxia sensing in human organoids and plays an important role in human tumorigenesis.

DISCUSSION

A groundbreaking landmark in understanding cellular response to changes in O2 supply is the discovery of HIF1α and its regulation by pVHL and prolyl hydroxylases (6, 7, 8, 9, 31). These findings build a molecular framework whereby changes in O2 levels mount robust transcriptional responses in adaptation to hypoxia. The results we present herein advance our understanding of molecular mechanisms underlying oxygen sensing and hypoxia adaptation. The key concept that emerges from our data is that the newly characterized lncRNA HILPS has a previously unrecognized role as an essential, global regulator of HIF1α stabilization and O2 sensing in human cells. HILPS and HIF1α create a positive, feedforward activation loop that is essential for sustained hypoxia responses. In aggregate, these findings unravel a mechanism that nominates the HILPS-PLK1-HIF1α pathway as a unique oxygen-sensing axis in human cells (fig. S7).

Unlike the simple worm Caenorhabditis elegans, the dimension of this primitive metazoan species is small enough that O2 can diffuse from the atmosphere into all of its thousand cells. Instead, O2 tension in the higher organism H. sapiens varies markedly between organs that are dedicated to distinct, specific biological functions. The extraordinary diversification of life forms during evolution demands much more sophisticated machinery in human to cope with the hypoxia confronted in both development and disease. It is generally agreed that lncRNAs exhibit much higher species variability than do protein-coding transcripts. Near 98% of the human transcribed genome comprises noncoding RNAs, including lncRNAs (32). Hence, lncRNAs are capable of introducing previously unsuspected regulatory machinery dictating the hypoxia responses in human. In the current study, we identify a poorly characterized lncRNA, HILPS, which exhibits a global expression in human normal cells and is also widely expressed in a myriad of human cancers. As bioinformatics analysis showed no conserved orthologs of HILPS in other species, HILPS most likely evolutionarily emerges to specifically orchestrate HIF1α signaling in normal and disease processes in human.

lncRNAs are highly abundant in human transcriptome, but little is known regarding the ways in which most of these lncRNAs are functioning in cells. We herein have defined a new class of lncRNA, HILPS, and performed a thorough investigation of its functional relevance both in vitro and in vivo. Our mechanistic study revealed that HILPS specifically binds to PLK1 such that it antagonizes the E3 ligase CDH1 leading to PLK1 stabilization. As PLK1 is a critical mitotic regulator that promotes cell cycle progression (33, 34), we reason that HILPS is also essential for proper cell division at normoxia. We identify HIF1α as a novel PLK1 substrate and validate that phosphorylation of HIF1α by PLK1 at T218 prevents its association with pVHL that normally binds to the HIF1α oxygen-dependent degradation domain (amino acids 330 to 530) (7, 35). Most likely, T218 phosphorylation alters the protein conformation that inhibits pVHL recognition of HIF1α and its subsequent degradation by proteasome. The elucidation of the HILPS-PLK1-HIF1α feed-forward regulatory circuit has expanded our understanding of lncRNA functions and has uncovered a heretofore-unknown role for PLK1 in properly coordinating cell cycle progression with hypoxia adaptation. It is worth noting that HILPS also exhibits appreciable cytoplasmic localization, suggesting a potential function of HILPS outside of its engagement with HIF1α in the nucleus.

Rates of protein synthesis at low levels of O2 are usually decreased to suppress unwanted energy-expensive processes. Instead, transcriptional activation of lncRNAs would be more economical for cell survival under hypoxic stress, allowing easier adaptation to O2 starvation. The current study was initiated in an attempt to identify lncRNAs that regulate universal hypoxia responses in human cells. To this end, we performed RNA-seq in a set of cell lines of different origins, including those from both normal and malignant tissues. We then enforced a widespread hypoxic induction by HIF1α as a selection criterion for nomination of HILPS to leverage multiple systems to robustly interrogate its role in O2 sensing. Our findings shed light on a previously unrecognized mechanism of the HILPS-PLK1-HIF1α feed-forward loop in response to O2 shortage and add a new layer of O2-mediated checkpoint that confers a fitness advantage upon hypoxia exposure. Hypoxia induction of lncRNAs was previously reported in several tumor contexts (36–38). Notably, these lncRNAs are not emerged as top candidates in our screen, suggesting that they are preferentially expressed in certain human cells. In addition, their physiological and pathological functions await further interrogation.

In summary, we used detailed molecular and genetic approaches to demonstrating that the precise regulation of HILPS is essential to control responses to O2 deprivation via PLK1-mediated stabilization of HIF1α. Therefore, HILPS acts as an important component of the molecular circuitry to orchestrate hypoxia-induced transcriptional responses, with wide implications for a variety of severe diseases in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines

NCM460, RKO, HCT116, MDA-MB-231, IMR90, A549 and 293T cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. All these cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Hyclone) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Hyclone). Human ESC HUES8 and H9 (also named WA09) were provided by W. Jiang (Medical Research Institute, Wuhan University, China) and cultured on Matrigel (Corning)–coated plates in mTesR1 (STEMCELL Technologies) with 1% penicillin/streptomycin. HUES8 and H9 cells were passaged every 4 days by Accutase (STEMCELL Technologies). The culture medium was changed every day. All cells were incubated in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 37°C and cultured for fewer than 6 months after resuscitation. Cells under hypoxia culture were placed in the Hypoxia Incubated Workstation (Ruskinn) and flushed with a gas mixture of 1% O2, 5% CO2, and balanced N2. All cells were tested for mycoplasma contamination every month using MycoAlert (Lonza).

RNA sequencing

RNA-seq was performed as described (39). Briefly, total cellular RNA was extracted using RNAiso Plus (Takara Bio) and subjected to quality control to inspect RNA integrity by Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies). RNAs were further purified by RNAClean XP Kit (Beckman Coulter) and ribonuclease-free deoxyribonuclease set (QIAGEN). RNA libraries were constructed using VAHTS Total RNA-seq (H/M/R) Library PrepKit for Illumina (Vazyme) and sequenced as 150-bp paired-end reads by Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (Shanghai Biotechnology Corporation). RNA-seq reads quality was evaluated using FastQC and mapped to the human genome reference assembly (hg38) by Bowtie 2. To identify differentially expressed genes, we used the edgeR software and considered those with a false discovery rate value below the threshold (Q < 0.01), log2 fold change greater than 0.5 (or less than −0.5), and fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) value greater than 1 as significant.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total cellular RNA was extracted using RNAiso Plus (Takara Bio) and cDNA was synthesized using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT kit (TOYOBO) following the manufacturer’s instructions. qPCR was conducted using FAST SYBR Green Master Mix on CFX Connect Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad). Relative RNA expression of was calculated by 2−ΔΔCt method. Real-time qPCR primers are listed in table S1.

Rapid amplification of cloned cDNA ends

RACE analysis was performed using the SMARTer RACE 5′/3′ Kit (Takara Bio) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, total RNA was extracted and subjected to reverse transcription. 5′ and 3′ RACE PCRs were performed with universal and gene-specific primers listed in table S1, and the resulting PCR products were cloned into linearized pRACE vector and sequenced.

Lentiviral transduction

Lentiviral vectors (pLKO.1 for shRNA and pHAGE for overexpression) were used for plasmid construction and transfected into 293T cells together with helper plasmids (pMD2.G and psPAX2) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Viral supernatants were generally collected 48 hours after transfection and gone through 0.45-μm filters (Millipore). For lentivirus infection, cells were seeded in six-well plate and infected at the 30 to 50% confluence. Appropriate amount of viruses in a final volume of 2 ml was added in cell culture for 12 to 24 hours, and polybrene (8 μg/ml) was included to increase efficiency during the infection. Transduced cells underwent puromycin selection for more than 24 hours before additional experiments were performed. shRNA-targeting sequences used in this study are listed in table S1.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

FISH was performed using a fluorescent in situ hybridization kit (RiboBio) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Cells grown on coverslips were fixed for 10 min (4% paraformaldehyde), washed three times using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco), and then permeabilized at 4°C for 5 min. Cells were washed and blocked in prehybridization buffer at 37°C for 30 min and then incubated in dark at 37°C overnight with Cy3-labeled specific RNA probes in hybridization buffer before washing at 42°C. All images were acquired and analyzed by confocal microscopy (Carl Zeiss).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

ChIP was performed as previously described (39). Briefly, cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min, then quenched with 0.125 M glycine for 5 min, and lysed in SDS lysis buffer. Cell lysate was subjected to a Bioruptor Pico Sonifier to shear chromatin DNA to a size range of 500 to 1000 bp. Precleared chromatin was immunoprecipitated with antibody against HIF1α or immunoglobulin G at 4°C for 16 hours. Antibody-chromatin complexes were pulled down with protein G agarose/salmon sperm DNA beads (Roche) (1 hour at 4°C). The eluted DNA was purified and quantified by qPCR. Specific primers are listed in table S1.

Luciferase reporter assay

pGL3 basic vector (0.5 μg) expressing HRE (or indicated mutant) in the HILPS promoter, along with 0.5 μg of Flag-HIF1α and 50 ng of Renilla luciferase reporter, was cotransfected in triplicates into 293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000. Luciferase activities were measured 24 hours later using Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Firefly luciferase activities were normalized to Renilla luciferase control values and shown as an average of triplicates. Luminescent readings are relative to empty vector–expressing cells.

BrdU incorporation assay

Cells were pulsed with BrdU (10 μM final concentration) for 1 hour, fixed with 70% ethanol (overnight at −20°C), followed by a 30-min treatment with 6% HCl and 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS and neutralization with 0.1 M Na2B4O7, and stained with an fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated anti-BrdU antibody (BioLegend) and propidium iodide (BioLegend). For cell cycle analysis, data were acquired using Cytoflex (Beckman) and analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Cell death assay

Cells were harvested and washed once with cold PBS. Apoptosis was analyzed using the annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate apoptosis kit (BioVision). Data were acquired using Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

AP staining

AP staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Beyotime). Briefly, cultured cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min, then washed three times with Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBS; Gibco), and incubated in 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium chloride (BCIP/NBT) staining mix in dark for 3 hours at room temperature. After washing with DPBS to terminate the staining reaction, cells were counterstained with neutral red staining solution for 30 min. Colonies were visualized and photographed using microscopy (Nikon).

Immunoblot and IP

For immunoblot, cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer [50 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 2 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, and leupeptin (0.5 μg/ml)], followed by centrifuging at 12,000g for 10 min at 4°C, and protein concentration was measured by bicinchonininc acid (BCA) assay (ZOMANBIO). Equal amount of protein was loaded and resolved by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). After transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad), blots were generally blocked with 5% fat-free milk at room temperature for 1 hour before incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Appropriate horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies were applied at room temperature for 1 hour. Blots were incubated with SuperSignal Chemiluminescent Substrate (Bio-Rad) and visualized by Chemi Doc Touch Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

For IP, cells were lysed in 1 ml of IP buffer [50 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, and 10% glycerol] supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) on ice for 30 min. Cells were centrifuged at 12,000g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was incubated with indicated antibodies at 4°C overnight and then with Protein G agarose beads (GE Healthcare) for additional 4 hours. Beads with associated proteins were washed with IP buffer. Attached proteins were eluted with SDS loading buffer and denatured at 95°C before SDS-PAGE and immunoblot. Primary antibodies used in this study are listed in table S2.

Immunofluorescence assay

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min and blocked with blocking solution DPBS with 10% (v/v) donkey serum and 0.3% Triton X-100. After washing, cells were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by secondary antibodies for 2 hours in dark at room temperature, and then counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 5 μg/ml) for 10 min. Stains were visualized and imaged by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus).

EB formation

Human ESCs were treated with Accutase to obtain single cells and then resuspended at the density of 100 cells/μl in mTesR1 in the presence of Y-27632 (10 μM; Selleck). Single-cell drops (20 μl) were placed on the lid of petri dishes for 24 hours, and aggregated EBs were then collected into 6-well low attachment plates and cultured in EB medium (DMEM/F12, Gibco, 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin) that was refreshed every 2 days. After 7-day culture, cells were visualized and imaged using microscopy, and total RNA was extracted for gene expression analysis by qPCR.

Biotinylated RNA pull-down assay

To synthesize biotinylated transcripts, the DNA template used in the transcription system was generated by reverse transcription PCR using forward primers containing the T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence. PCR products were purified using DNA gel extraction kit (Axygen). In vitro transcription was performed using a biotin-RNA transcription Kit (Lucigen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions under ribonuclease-free condition. Biotinylated RNA (3 μg) was incubated with lysates from ten million cells for 1 to 2 hours at 4°C. Streptavidin-coupled Dynabeads (Invitrogen) were then added to enrich the RNA-protein complex and incubated for additional 3 to 6 hours. Washed beads were boiled in 2× SDS loading buffer at 95°C. The retrieved proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot.

Time-course analysis of protein degradation

Cells undergoing indicated treatment were subjected to cycloheximide (100 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) treatment and harvested at specific time points. Total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, and protein levels were analyzed by immunoblot.

Ubiquitination analysis

Cells were lysed in 100 μl of 1% SDS lysis buffer. Cell lysates were sonicated and denatured at 95°C for 15 min to disrupt protein interaction and then diluted with 900 μl of IP buffer. After centrifugation at 12,000g for 15 min at 4°C, a small portion of supernatant was saved as input to detect protein expression, and majority of cell extracts underwent IP with specific antibodies. Protein polyubiquitination was examined by immunoblot analysis with antiubiquitin antibody.

In vitro protein-protein interaction assay

His-CDH1 protein was purchased from CUSABIO. cDNA sequence encoding PLK1 was cloned into the pGEX-4T vector, in frame with GST. Recombinant proteins were expressed in the Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) strain, and GST-PLK1 were purified and immobilized onto glutathione-agarose beads (PerkinElmer). For in vitro binding assay, glutathione beads associated with GST-PLK1 were incubated overnight with His-CDH1. Purified complexes were washed three times with IP lysis buffer and then separated on SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Coomassie staining and/or immunoblot.

Stable isotope tracing

For glucose tracing, H9 cells were cultured under 1% O2 for 24 hours. Culture media were then refreshed with glucose-free DMEM/F12 supplemented with 13C6-glucose (3.151 g/liter; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) and 10% knockout serum replacement (Gibco) for 4 hours4. Cells were then washed twice with cold PBS. Cellular metabolites were extracted as described previously (40). Briefly, cells were added with 1 ml of 80% methanol (v/v) (prechilled to −80°C) and immediately placed on dry ice. After overnight incubation at −80°C, cells were centrifuged at 14,000g for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected and evaporated before metabolite analysis in the Metabolomics Facility Center in National Protein Science Technology Center of Tsinghua University. Identification and quantification of metabolites were conducted by the Dionex Ultimate 3000 ultraperformance liquid chromatography system, coupled to a TSQ Quantiva Ultra triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

In vitro protein kinase assay

Human PLK1 kinases purified from 293T cells overexpressing PLK1 mutants (Fig. 6D) or purchased from SinoBiological (Fig. 6E) were used to catalyze the kinase reaction. GST-HIF1α (WT or mutant) was expressed in the E. coli BL21 (DE3) strain and purified as substrates. Two milligrams of the indicated GST fusion proteins were incubated with PLK1 in the kinase buffer (Cell Signaling Technologies) together with 5 μCi of [γ-32P] ATP (PerkinElmer) and 200 mM cold ATP (Cell Signaling Technologies) at 30°C for 1 hours. Reactions were stopped by addition of SDS loading buffer, and samples were then heated at 95°C for 5 min before analysis by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

In sample preparations, to determine HILPS-associated proteins (Fig. 4A), biotinylated RNA pull-down samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Gel slices including all proteins were excised. To identify HIF1α phosphorylation sites (fig. S5, E and F), kinases (PLK1 T210D or K82R) and GST-HIF1α were incubated in the kinase buffer together with 200 mM cold ATP at 30°C for 1 hour. Reaction was stopped by addition of SDS loading buffer, followed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. Gel bands corresponding to GST-HIF1α were excised.

Liquid chromatography–MS/MS analysis was performed in the Protein Chemistry Facility, Center of Biomedical Analysis at Tsinghua University. Briefly, proteins were treated with 5 mM dithiothreitol and 11 mM iodoacetamide, followed by gel digestion with sequencing grade-modified trypsin at 37°C overnight. The resulting peptides were separated by silica capillary column and eluted at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min with the UltiMate 3000 high-performance liquid chromatography system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled with the Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which was set in the data-dependent acquisition mode by Xcalibur 2.2 software. We then mapped the MS/MS spectra from each run with the protein sequence from UniProt using an in-house Proteome Discoverer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, version PD1.4).

Proliferation and colony formation assay in human organoids

Human organoids maintained in culture medium for ~10 days (reaching a density of 60 to 70%) were dissociated into single cells using TrypLE Express (Gibco). For proliferation assay, 5000 single cells were seeded in each well of the 96-well plate for continuing culture. Organoid proliferation was assessed by the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (APExBIO). CCK-8 reagent was added into the wells after culture for 7 days, followed by measurement of optical density at 450 nm. For colony formation assay, 1000 single cells were seeded in each well of the 48-well plate for continuing culture. Organoid counting started 10 days later. Each experiment was performed in biological replicates.

Animal models

For cell line–derived xenograft, three million HCT116 cells resuspended in 50 μl of DMEM and mixed with an equal volume of Matrigel (Corning) were subcutaneously injected into both flanks of the axilla of 5-week-old female athymic nude mice (GemPharmatech). Tumor volumes were measured every 3 days using calipers and calculated using the formula: length × width2 × 0.5. Tumors were collected and weighed after euthanasia. All mice were maintained in specific pathogen–free animal facility of Medical Research Institute, Wuhan University, and animal experiments were performed according to animal ethical regulations and with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Wuhan University.

For patient-derived organoid–based xenograft, 5-week-old NSG mice were purchased from Shanghai Model Organisms Center for renal capsule transplant. Colorectal cancer organoids equivalent to one million cells were collected and resuspended in a 20-μl mixture of 50% Matrigel and 50% medium and then kept on ice until kidney capsule transplantation. Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg, i.p.). The lateral site of the left abdomen was shaved and kept sterilized. Two-centimeter incision of the skin, muscle, and peritoneum was made vertically to subcostal before kidney was externalized. The kidney capsule was kept moist with PBS during the procedure. Organoids were injected into the kidney capsule using an insulin syringe. The incision in the peritoneum and skin was sutured and sterilized. The engrafted mice were euthanized 7 weeks later for tumor assessment. Mice were maintained in specific pathogen–free animal facility of School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, and all the animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and compliant with ethical regulations regarding animal research.

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were performed with GraphPad Prism 7. P values were calculated by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test between two groups or by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) when comparing two groups among three or more groups. Data were presented as means ± S.D. of triplicate experiments. For statistical significance, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, and n.s. means no significance.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Qing, Zhao, and Liu laboratories for suggestions and the Core Facility of Medical Research Institute at Wuhan University for technic support. We also thank W. Jiang (Medical Research Institute, Wuhan University, China) for providing human ESC lines and technic support.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA1100501 and 2022YFA1103200), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82230092 and 81830084 to G.Q. and 82161138024 to H.L.), National Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholar (82025003 to H.L.), Hubei Provincial Natural Science Fund for Creative Research Groups (2021CFA003 to H.L.), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2042022dx0003).

Author contributions: G.Q. and B.Z. conceived ideas and designed the study. G.Q., B.Z., and H.L. supervised the study. G.Q., H.L., and Z.C. wrote the manuscript. Z.C. and C.C. performed most of the experiments with assistance from R.T., M.Y., W.K., and H.H. L.X. performed organoid experiments. D.W. performed the RNA-seq analysis. M.H. performed mass spectrum analysis.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: RNA-seq data have been deposited at GEO under accession number GSE230388. The MS data generated in this study have been deposited in the ProteomeXchange database under accession number PXD042226. All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S7

Tables S1 and S2

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.M. Ivan, W. G. Kaelin Jr., The EGLN-HIF O2-sensing system: Multiple inputs and feedbacks. Mol. Cell 66, 772–779 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.B. Keith, R. S. Johnson, M. C. Simon, HIF1α and HIF2α: Sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 9–22 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.J. A. Bertout, S. A. Patel, M. C. Simon, The impact of O2 availability on human cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 967–975 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.A. J. Majmundar, W. J. Wong, M. C. Simon, Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol. Cell 40, 294–309 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.C. J. Schofield, P. J. Ratcliffe, Oxygen sensing by HIF hydroxylases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 343–354 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.G. L. Wang, B. H. Jiang, E. A. Rue, G. L. Semenza, Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 5510–5514 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.M. Ivan, K. Kondo, H. Yang, W. Kim, J. Valiando, M. Ohh, A. Salic, J. M. Asara, W. S. Lane, W. G. Kaelin Jr, HIFα targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: Implications for O2 sensing. Science 292, 464–468 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.P. Jaakkola, D. R. Mole, Y. M. Tian, M. I. Wilson, J. Gielbert, S. J. Gaskell, A. von Kriegsheim, H. F. Hebestreit, M. Mukherji, C. J. Schofield, P. H. Maxwell, C. W. Pugh, P. J. Ratcliffe, Targeting of HIF-α to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 292, 468–472 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.P. H. Maxwell, M. S. Wiesener, G. W. Chang, S. C. Clifford, E. C. Vaux, M. E. Cockman, C. C. Wykoff, C. W. Pugh, E. R. Maher, P. J. Ratcliffe, The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature 399, 271–275 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.W. G. Kaelin Jr., P. J. Ratcliffe, Oxygen sensing by metazoans: The central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol. Cell 30, 393–402 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.P. Lee, N. S. Chandel, M. C. Simon, Cellular adaptation to hypoxia through hypoxia inducible factors and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 268–283 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.C. Loenarz, M. L. Coleman, A. Boleininger, B. Schierwater, P. W. H. Holland, P. J. Ratcliffe, C. J. Schofield, The hypoxia-inducible transcription factor pathway regulates oxygen sensing in the simplest animal, Trichoplax adhaerens. EMBO Rep. 12, 63–70 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.F. Kopp, J. T. Mendell, Functional classification and experimental dissection of long noncoding RNAs. Cell 172, 393–407 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.J. J. Quinn, H. Y. Chang, Unique features of long non-coding RNA biogenesis and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 47–62 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.L. Allou, S. Balzano, A. Magg, M. Quinodoz, B. Royer-Bertrand, R. Schöpflin, W. L. Chan, C. E. Speck-Martins, D. R. Carvalho, L. Farage, C. M. Lourenço, R. Albuquerque, S. Rajagopal, S. Nampoothiri, B. Campos-Xavier, C. Chiesa, F. Niel-Bütschi, L. Wittler, B. Timmermann, M. Spielmann, M. I. Robson, A. Ringel, V. Heinrich, G. Cova, G. Andrey, C. A. Prada-Medina, R. Pescini-Gobert, S. Unger, L. Bonafé, P. Grote, C. Rivolta, S. Mundlos, A. Superti-Furga, Non-coding deletions identify Maenli lncRNA as a limb-specific En1 regulator. Nature 592, 93–98 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Y. Li, Z. Tan, Y. Zhang, Z. Zhang, Q. Hu, K. Liang, Y. Jun, Y. Ye, Y. C. Li, C. Li, L. Liao, J. Xu, Z. Xing, Y. Pan, S. S. Chatterjee, T. K. Nguyen, H. Hsiao, S. D. Egranov, N. Putluri, C. Coarfa, D. H. Hawke, P. H. Gunaratne, K. L. Tsai, L. Han, M. C. Hung, G. A. Calin, F. Namour, J. L. Guéant, A. C. Muntau, N. Blau, V. R. Sutton, M. Schiff, F. Feillet, S. Zhang, C. Lin, L. Yang, A noncoding RNA modulator potentiates phenylalanine metabolism in mice. Science 373, 662–673 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.C. J. Guo, X. K. Ma, Y. H. Xing, C. C. Zheng, Y. F. Xu, L. Shan, J. Zhang, S. Wang, Y. Wang, G. G. Carmichael, L. Yang, L. L. Chen, Distinct processing of lncRNAs contributes to non-conserved functions in stem cells. Cell 181, 621–636.e22 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.M. M. Elguindy, J. T. Mendell, NORAD-induced Pumilio phase separation is required for genome stability. Nature 595, 303–308 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D. Andergassen, J. L. Rinn, From genotype to phenotype: Genetics of mammalian long non-coding RNAs in vivo. Nat. Rev. Genet. 23, 229–243 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Y. J. Kang, D. C. Yang, L. Kong, M. Hou, Y. Q. Meng, L. Wei, G. Gao, CPC2: A fast and accurate coding potential calculator based on sequence intrinsic features. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W12–W16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.S. L. Dunwoodie, The role of hypoxia in development of the mammalian embryo. Dev. Cell 17, 755–773 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.M. D. O'Connor, M. D. Kardel, I. Iosfina, D. Youssef, M. Lu, M. M. Li, S. Vercauteren, A. Nagy, C. J. Eaves, Alkaline phosphatase-positive colony formation is a sensitive, specific, and quantitative indicator of undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 26, 1109–1116 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.M. Guttman, J. L. Rinn, Modular regulatory principles of large non-coding RNAs. Nature 482, 339–346 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.F. Bassermann, D. Frescas, D. Guardavaccaro, L. Busino, A. Peschiaroli, M. Pagano, The Cdc14B-Cdh1-Plk1 axis controls the G2 DNA-damage-response checkpoint. Cell 134, 256–267 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.L. Wan, M. Chen, J. Cao, X. Dai, Q. Yin, J. Zhang, S. J. Song, Y. Lu, J. Liu, H. Inuzuka, J. M. Katon, K. Berry, J. Fung, C. Ng, P. Liu, M. S. Song, L. Xue, R. T. Bronson, M. W. Kirschner, R. Cui, P. P. Pandolfi, W. Wei, The APC/C E3 ligase complex activator FZR1 restricts BRAF oncogenic function. Cancer Discov. 7, 424–441 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.A. Subramanian, P. Tamayo, V. K. Mootha, S. Mukherjee, B. L. Ebert, M. A. Gillette, A. Paulovich, S. L. Pomeroy, T. R. Golub, E. S. Lander, J. P. Mesirov, Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15545–15550 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.G. P. Elvidge, L. Glenny, R. J. Appelhoff, P. J. Ratcliffe, J. Ragoussis, J. M. Gleadle, Concordant regulation of gene expression by hypoxia and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase inhibition: The role of HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and other pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 15215–15226 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.G. L. Semenza, Hypoxia-inducible factors in physiology and medicine. Cell 148, 399–408 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.H. Clevers, Modeling development and disease with organoids. Cell 165, 1586–1597 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.J. Drost, H. Clevers, Organoids in cancer research. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18, 407–418 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.G. L. Semenza, M. K. Nejfelt, S. M. Chi, S. E. Antonarakis, Hypoxia-inducible nuclear factors bind to an enhancer element located 3' to the human erythropoietin gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 5680–5684 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.F. J. Slack, A. M. Chinnaiyan, The role of non-coding RNAs in oncology. Cell 179, 1033–1055 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.W. Bruinsma, J. A. Raaijmakers, R. H. Medema, Switching polo-like kinase-1 on and off in time and space. Trends Biochem. Sci. 37, 534–542 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.K. S. Lee, T. R. Burke Jr., J. E. Park, J. K. Bang, E. Lee, Recent advances and new strategies in targeting Plk1 for anticancer therapy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 36, 858–877 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.M. Ohh, C. W. Park, M. Ivan, M. A. Hoffman, T. Y. Kim, L. E. Huang, N. Pavletich, V. Chau, W. G. Kaelin, Ubiquitination of hypoxia-inducible factor requires direct binding to the β-domain of the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 423–427 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.F. Yang, H. Zhang, Y. Mei, M. Wu, Reciprocal regulation of HIF-1α and lincRNA-p21 modulates the Warburg effect. Mol. Cell 53, 88–100 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.J. Tong, X. Xu, Z. Zhang, C. Ma, R. Xiang, J. Liu, W. Xu, C. Wu, J. Li, F. Zhan, Y. Wu, H. Yan, Hypoxia-induced long non-coding RNA DARS-AS1 regulates RBM39 stability to promote myeloma malignancy. Haematologica 105, 1630–1640 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.F. Zheng, J. Chen, X. Zhang, Z. Wang, J. Chen, X. Lin, H. Huang, W. Fu, J. Liang, W. Wu, B. Li, H. Yao, H. Hu, E. Song, The HIF-1α antisense long non-coding RNA drives a positive feedback loop of HIF-1α mediated transactivation and glycolysis. Nat. Commun. 12, 1341 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.J. Jiang, J. Wang, M. Yue, X. Cai, T. Wang, C. Wu, H. Su, Y. Wang, M. Han, Y. Zhang, X. Zhu, P. Jiang, P. Li, Y. Sun, W. Xiao, H. Feng, G. Qing, H. Liu, Direct phosphorylation and stabilization of MYC by aurora b kinase promote T-cell leukemogenesis. Cancer Cell 37, 200–215.e5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.M. Yuan, S. B. Breitkopf, X. Yang, J. M. Asara, A positive/negative ion-switching, targeted mass spectrometry-based metabolomics platform for bodily fluids, cells, and fresh and fixed tissue. Nat. Protoc. 7, 872–881 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S7

Tables S1 and S2