Abstract

The luxCDABE bioluminescence genes of the Vibrio fischeri lux system have been used as a reporter system for different stress and regulatory promoters of Escherichia coli. Selected E. coli strains carrying lux genes fused to different promoters were exposed to various toxic chemicals, and the recorded luminescence was used for the characterization of the biologic signature of each compound. Analysis of these data with the aid of a proper algorithm allowed quantitative and qualitative assessment of toxic chemicals. Of the 25 tested chemicals, 23 were identified by this novel strategy in a 3-h procedure. This system can also be adapted for the identification of simple mixtures of toxic agents when the biologic signatures of the individual compounds are known. This biologic recognition strategy also provides a tool for evaluating the degree of similarity between the modes of action of different toxic agents.

A general assay for water toxicity with intact freeze-dried Vibrio fischeri cells has been widely applied for monitoring industrial water toxicity (7) and genotoxicity (24). Genetically controlled bacterial bioluminescence probes have been developed in order to detect environmental pollutants and stress-inducing chemicals (3, 4, 25, 26). Van Dyk et al. (25, 26) and Belkin et al. (3, 4) have fused the luxCDABE genes of V. fischeri to various promoter genes under the control of several global regulatory circuits, including rpoH, soxRS, oxyR, fadR, crp, uspA, and recA. Activation of these promoters resulted in the development of luminescence at the intensity and with the kinetics characteristic for each promoter. Belkin et al. (4) have broadened this principle by applying a panel of selected stress-responsive promoters to the detection of diverse groups of toxicants. Other groups have applied other recombinant bacterial sensors to the determination of specific toxic compounds, such as certain heavy metals (9, 10, 17, 19); organic compounds, such as naphthalene (8, 13, 14); and alkanes (22).

The present report describes a novel method based on the genetic fusions that were constructed by Van Dyk et al. (25, 26) and Belkin et al. (3, 4) for the quantitative and qualitative identification of toxic chemicals and for the elucidation of their modes of action.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Escherichia coli RFM443 (galK2 lac74 rpsL200) (15) and E. coli DE112 (galK2 lac74 rpsL200 tolC) (25) were provided by R. A. LaRossa (DuPont, Wilmington, Del.). E. coli JF699 [lacY29 proC24 tsx-63 purE41 λ− ompA252 his-53 rpsL97 (strR) xyl-14 metB65 cycA1 cycB2 ilv-277] (11) and E. coli SB1803 [thr-1 ara-14 leuB6 Δ(gpt-proA)62 lacY1 supE44 galK12 λ− rac hisC3 rfbD1 metG83 rpsL25 kdgK51 xyl-5 mtl-1 thi-1 lpcB] (5) were provided by B. J. Bachmann (E. coli Genetic Stock Center, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.). E. coli DPD1006 containing the lon′::lux (rpoH-controlled protease) fusion plasmid pLonLux2 (25, 27), E. coli DPD2511 containing the katG′::lux (oxyR-controlled catalase) fusion plasmid pKatGLux2 (3, 25), E. coli DPD2519 containing the micF′::lux (in the soxRS regulon; responsive to superoxides) fusion plasmid pMicFLux1 (3, 25), E. coli DPD2540 containing the fabA′::lux (a β-hydroxydecanoylthioester dehydrase gene under fadR control) fusion plasmid pFabALux6 (4, 25), E. coli DE135 containing the uspA′::lux (universal stress) fusion plasmid pUspALux2 (25, 28), and E. coli TV1068 containing the lac′::lux (β-galactosidase) fusion plasmid pLacLux (25) were kindly provided by S. Belkin (Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel) and R. A. LaRossa. These plasmids are based on the pUCD615 plasmid (18) carrying the V. fischeri promoterless luxCDABE genes fused to the above-mentioned promoter elements.

Media and conditions for growth.

The bacterial strains were cultivated in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (16) containing 50 μg of ampicillin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml. The cultures were grown with shaking in test tubes in a reciprocal shaker (280 rpm) at 37°C. The assay medium contained dilute (3.75%) LB broth in a salts-buffer mixture (pH 6.9) containing the following: NaCl, 10 g/liter; PIPES (1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid) buffer (Sigma), 5 g/liter; CaCl2 · 2H2O, 0.15 g/liter; and MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.1 g/liter. The dilute medium had no significant effect on the level of the luminescence that developed, while it minimized the interactions of the tested chemicals with its components. Calcium and magnesium salts and a buffer were added in order to minimize the potential influences of the hardness and pH of drinking water samples.

Assay system.

Overnight-grown cultures were diluted 100-fold in fresh LB broth containing ampicillin (50 μg/ml) and grown with shaking at 37°C to the early exponential growth phase (optical density at 600 nm, 0.2). The cells were placed on ice until used. The chilled bacterial cultures were diluted 1:1 in cold LB broth, and 10-μl aliquots were added to wells of an opaque white microtiter plate (Dynatech Microfluor) which contained twofold serial dilutions of the test samples in a final volume of 150 μl of assay medium. The microtiter plates were incubated at 27°C and analyzed at hourly intervals for luminescence by use of a temperature-controlled (27°C) microplate recording luminometer (Lucy 1; Anthos Labtech, Salzburg, Austria).

Chemicals.

The sources of the chemicals assayed were as follows: 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T), 2,4,6-trichlorophenol (2,4,6-TCP), 3,5-dichlorophenol (3,5-DCP), fluoranthene, and pentachlorophenol (PCP) were from Aldrich, Madison, Wis.; KH2AsO4 and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) were from BDH, Poole, England; propiconazole was from Ciba-Geigy, Basel, Switzerland; 4-nitrophenol, benzidine, and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) were from Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland; PbCl2 was from Mallinokrodt, St. Louis, Mo.; CdCl2, H2O2, HgCl2, and ZnCl2 were from E. Merck AG, Darmstadt, Germany; sodium azide was from Reidel-de Haen, Seelze, Germany; 2,4-dinitrophenol (2,4-DNP), methyl viologen, NiSO4, and proflavin hemisulfate were from Sigma; phenol was from Spectrum, Redondo Beach, Calif.; and malathion (O,O-dimethyldithiophosphate) and parathion (diethyl-p-nitrophenyl monothiophosphate) were from Tarsis, Tel-Aviv, Israel. All the toxicants were of analytical grade. The toxicants were dissolved in water or ethanol. Ethanol (not exceeding 0.05%) had a negligible effect. The chemicals were doubly diluted in the assay medium for 11 dilutions; see Table 2 for the initial concentrations (known concentrations).

TABLE 2.

Estimation of the concentrations of 25 toxicants treated as unknown samples

| Toxicant | Known concn (μg/ml) | Predicted concn (μg/ml) in replicate

|

Mean predicted concn ± SD (μg/ml) | Prediction error (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Methyl viologen | 16 | 19 | 15 | 14 | 16 ± 3 | 0 |

| NiSO4 | 64 | 71 | 55 | 66 | 64 ± 8 | 0 |

| PCP | 32 | 25 | 39 | 31 | 32 ± 7 | 1 |

| 2,4,5-T | 256 | 233 | 277 | 244 | 251 ± 23 | 2 |

| Fluoranthene | 128 | 144 | 137 | 113 | 131 ± 16 | 3 |

| Phenol | 256 | 209 | 333 | 273 | 272 ± 62 | 6 |

| 2,4-DNP | 256 | 255 | 279 | 176 | 237 ± 54 | 8 |

| 4-Nitrophenol | 32 | 32 | 28 | 28 | 29 ± 2 | 8 |

| PbCl2 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 4 ± 2 | 8 |

| SDS | 256 | 235 | 305 | 288 | 276 ± 37 | 8 |

| Parathion | 128 | 202 | 127 | 90 | 140 ± 57 | 9 |

| Sodium azide | 256 | 168 | 309 | 225 | 234 ± 71 | 9 |

| ZnCl2 | 64 | 58 | 81 | 70 | 70 ± 12 | 9 |

| Benzidine | 256 | 240 | 208 | 240 | 229 ± 18 | 10 |

| 2,4-D | 256 | 226 | 249 | 212 | 229 ± 19 | 11 |

| CTAB | 256 | 314 | 294 | 245 | 284 ± 36 | 11 |

| 3,5-DCP | 128 | 130 | 105 | 104 | 113 ± 15 | 12 |

| KH2AsO4 | 256 | 342 | 335 | 188 | 288 ± 87 | 13 |

| Hydrogen peroxide | 4 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 3 ± 2 | 17 |

| Proflavin hemi- sulfate | 64 | 80 | 75 | 71 | 75 ± 5 | 18 |

| CdCl2 | 16 | 12 | 15 | 12 | 13 ± 2 | 19 |

| 2,4,6-TCP | 256 | 192 | 209 | 164 | 188 ± 23 | 26 |

| Propiconazole | 64 | 53 | 100 | 99 | 84 ± 27 | 31 |

| Malathion | 128 | 106 | 89 | 56 | 84 ± 25 | 35 |

| HgCl2 | 4 | 7 | 13 | 4 | 8 ± 5 | 100 |

Data analysis.

The results presented are the averages of the values obtained in two to five independent analyses. The relative activity (RA) values were calculated from the recorded data and used for classification of the toxicants into groups with SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C.) by use of the discriminant analysis (DA) method (21). The generalized squared distances (GSD) were calculated with SAS software and clustered into dendrograms by use of the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA) (20) with the help of Vostorg software (29).

RESULTS

Identification of toxicants on the basis of their biologic signatures.

The rationale of our method assumes that most of the toxicants activate certain lux-fused promoters in a characteristic pattern. Thus, the level of luminescence reflects the biologic signatures of these chemicals. Unknown samples were identified by comparing their biologic signatures to those of known standards (learning data; see below). The biologic signatures were determined on the basis of the dependence of the luminescence obtained at given times on the concentration of the chemical in question and on the basis of the mathematical behavior of this dependence. Curves demonstrating such dependence have been published (3, 4, 25, 26).

In order to obtain maximal sensitivity, each of the plasmids harboring the lux-fused promoters was stored in different E. coli mutants, and the best plasmid-host combinations were selected. For example, it appeared that E. coli JF699 harboring the katG′::lux fusion was more sensitive to heavy metals than the other examined hosts and that E. coli DE112 and E. coli SB1803 harboring the micF′::lux and uspA′::lux fusions, respectively, were more sensitive to phenol-related compounds. The response specificity of these strains was mainly attributed to the different responses of the various promoters. The different hosts contributed only minor specificity.

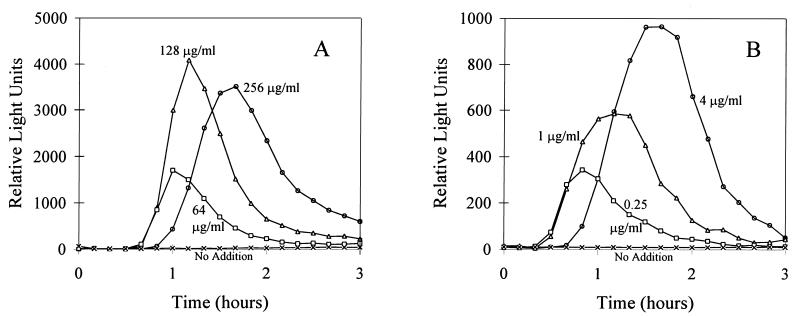

Each one of the seven bacterial constructs described in Table 1 was challenged with a series of concentrations of 25 model chemicals, and luminescence was determined after different incubation periods. Figure 1 shows an example of the kinetics of light emission by two bacterial tester strains, E. coli DE112 (lon′::lux) and E. coli JF699 (katG′::lux), that were exposed to different concentrations of 2,4,6-TCP and CdCl2. During the first 3 h of incubation, luminescence was negligible in the controls, while the luminescence of cells that were incubated with the tested toxicants increased after 45 min of incubation, followed by a rapid decrease. For analytical purposes, the luminescence that developed was examined after 1, 2, and 3 h of incubation at 27°C.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial constructsa

| E. coli host | Promoter fusion |

|---|---|

| DE112 (25) | micF′::lux (3, 25) |

| DE112 (25) | lon′::lux (25, 27) |

| DE112 (25) | fabA′::lux (4, 25) |

| RFM443 (15) | lac′::lux (25) |

| JF699 (11) | katG′::lux (3, 25) |

| SB1803 (5) | uspA′::lux (25, 28) |

| SB1803 (5) | micF′::lux (3, 25) |

a Numbers in parentheses are references.

FIG. 1.

Kinetics of E. coli DE112 (lon′::lux) induction by 2,4,6-TCP (A) and E. coli JF699 (katG′::lux) induction by CdCl2 (B) during 3 h of incubation at 27°C. The toxicants were used at various concentrations. Averages from two replicates are presented.

Two parameters, A and R2, that led to an increase in luminescence (in any member of the bacterial assay panel for each of the three incubation periods) were calculated for each chemical. A was defined as the maximum slope of the linear regression curve between the response ratio (RR) (the ratio between the light level of the tested sample and that of the control) and the logarithm of the concentration (for a concentration range of 1 order of magnitude), and R2 was defined as the linear correlation coefficient of this regression curve. Using these two values, we calculated a best-fit parameter, RA, which was found to characterize the effect of each chemical on a specific tester strain: RA = −0.25 × (R2)2 × (log A + 1). RA is a logarithmic function of A and a second-order polynomial function of R2. A reflects the activity of a given toxicant in a given system, and R2 minimizes the nonspecific fluctuations.

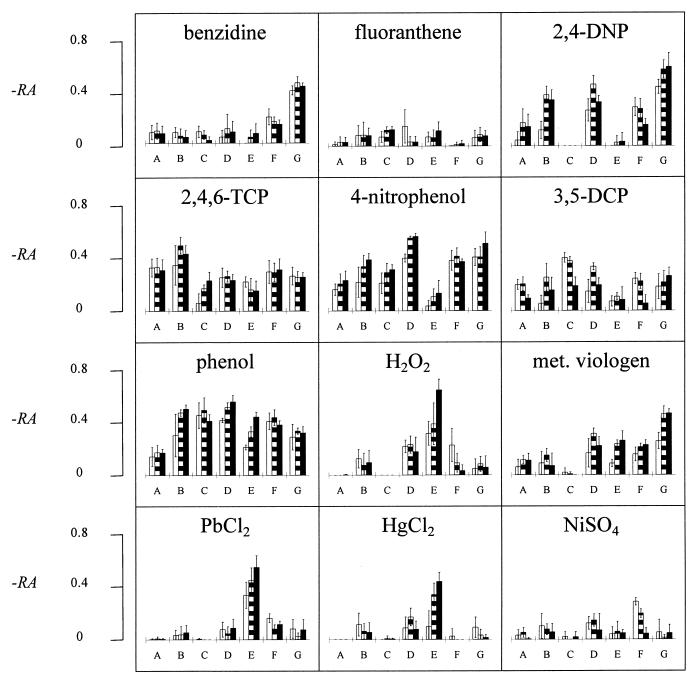

Figure 2 shows the RA values for the 25 chemicals assayed with the members of the bacterial panel after three incubation periods. The 25 histograms shown represent the characteristic biologic signatures of the tested chemicals. In order to confirm the specificity of each biologic signature, the RA values were analyzed by DA with SAS statistical software. The DA classified the unknown samples into n groups, where n was the number of tested chemical standards (learning data). In each group, all the unknown chemicals that shared common features with a known chemical (standard) were clustered.

FIG. 2.

Characterization of 25 chemicals in terms of activating the promoters of seven E. coli strains: A, DE112 (micF′::lux); B, DE112 (lon′::lux); C, DE112 (fabA′::lux); D, RFM443 (lac′::lux); E, JF699 (katG′::lux); F, SB1803 (uspA′::lux); and G, SB1803 (micF′::lux). The biologic signatures show the activation (calculated as −RA) of the stress promoters by 25 chemicals after incubation for 1 h (open bars), 2 h (striped bars), and 3 h (solid bars). The histograms show average results for five replicates ± standard deviations.

To test the validity of this approach, five independent replicates were carried out for each chemical. Four of these were randomly chosen as learning data, and one replicate was evaluated as an unknown; the entire procedure was repeated five times. Using this system, we accurately identified 23.4 ± 1.5 (mean ± standard deviation) of the 25 tested chemicals. Only eight false-negative results were obtained out of 125 (25 × 5) examinations. Very often, the mistaken identities exhibited high chemical or functional similarities to the true identities. Thus, Zn2+ was misclassified as Cd2+, SDS was misclassified as CTAB, and malathion was misclassified as parathion.

Estimation of the concentrations of the tested chemicals.

In addition to the chemical identification, the procedure described here allows an estimation of the concentrations of the tested chemicals. This estimate was determined by comparison of the regression lines between RR and C to the regression lines of the standards, where C is the concentration of either the known standard (micrograms per milliliter) or the unknown chemical (in arbitrary units). This procedure was carried out for each member of the bacterial assay panel for three incubation periods. Of the 21 values used (seven strains, three periods), the seven upper and lower predicted concentrations were excluded. The final predicted concentration for each replicate of each chemical was estimated by averaging the seven remaining values by use of a method similar to the trimmed Spearman-Karber method (12). This procedure was carried out for five replicates. The final predicted concentration for each chemical (Table 2) was calculated by averaging the values for the three replicates remaining after exclusion of the higher and lower replicates, as in the trimmed Spearman-Karber method (12). The coefficient of correlation between the known and predicted concentrations was 0.96.

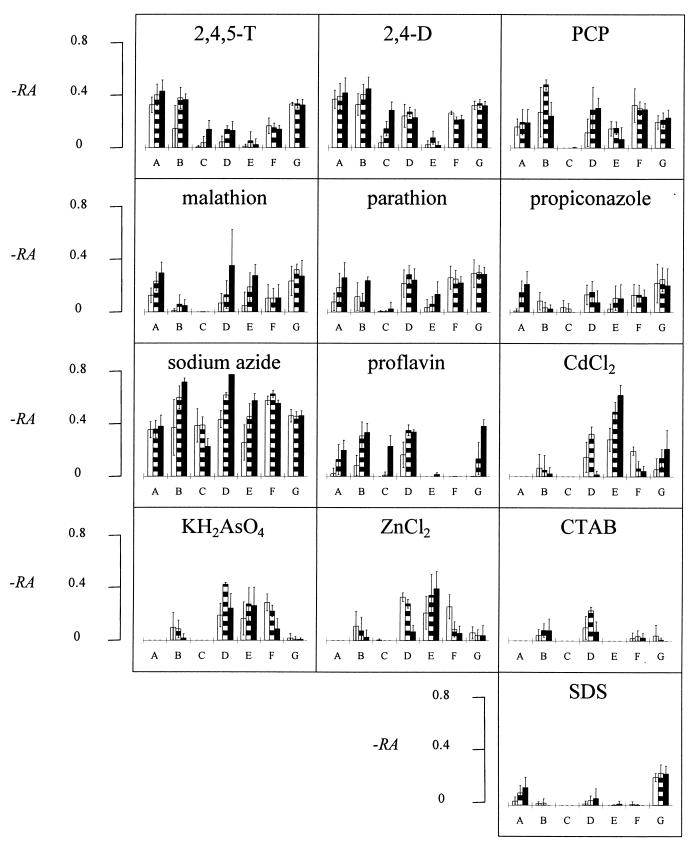

Identification of mixtures of toxicants.

The method described here can also be adapted for the identification of a mixture of two toxic agents. The biologic signature of a mixture can be predicted by use of the learning data characterizing each toxicant separately. The RR for the mixed chemicals was predicted on the basis of the RRs for the potential individual components of the mixture at different ratios. For mixtures of two toxicants, the predicted RR (PRR) for each concentration of the mixture was calculated on the basis of the RRs for the individual toxicants, RR1 and RR2, as follows:

|

With this identification procedure, the characterized biologic signature (as determined by the PRR) was evaluated for each potential mixture of toxicants. An example of the prediction of the biologic signatures of two mixtures of toxicants is shown in Fig. 3. The coefficient of correlation between the observed and the predicted 21 RA values for the mixtures of CdCl2 and PCP was 0.93; that for the mixtures of NaN3 and 2,4,5-T was 0.85. As previously shown (3, 27), some mixtures had synergistic effects on the level of luminescence. We observed synergy with a mixture of sodium azide and 2,4,5-T for strains harboring the fusions micF′::lux, lon′::lux, and lac′::lux as well as with a mixture of CdCl2 and PCP for strains harboring the fusions katG′::lux, lon′::lux, and lac′::lux.

FIG. 3.

Estimation of the biologic signatures of CdCl2-PCP mixtures and sodium azide–2,4,5-T mixtures, as determined by the activation of the promoters of seven E. coli strains: A, DE112 (micF′::lux); B, DE112 (lon′::lux); C, DE112 (fabA′::lux); D, RFM443 (lac′::lux); E, JF699 (katG′::lux); F, SB1803 (uspA′::lux); and G, SB1803 (micF′::lux). The histograms show the predicted activation and the real activation (calculated as −RA) of the stress promoters by the two mixtures at effective concentrations of 16 μg/ml (CdCl2), 32 μg/ml (PCP), 4,096 μg/ml (sodium azide), and 2,048 μg/ml (2,4,5-T) after incubation for 1 h (open bars), 2 h (hatched bars), and 3 h (solid bars). The biologic signatures of the single components are shown in Fig. 2. The histograms show average results for two replicates ± standard deviations.

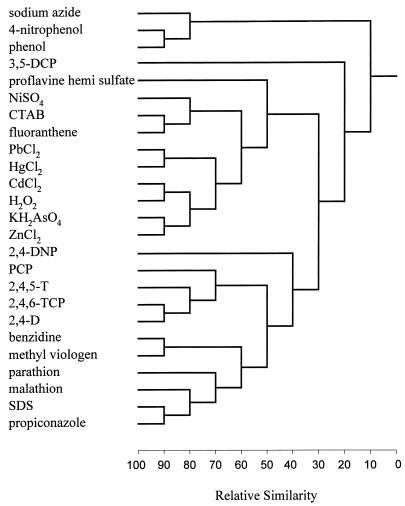

Elucidation of the modes of action of the toxic chemicals.

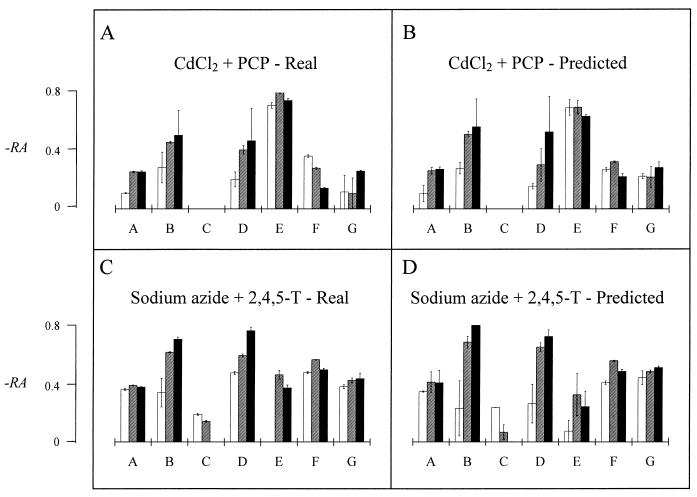

The degree of similarity in the modes of action of the 25 toxicants tested was evaluated according to the GSD obtained in the DA by use of the UPGMA. This method calculates the distances between the tested groups on the basis of the GSD of all pairs of toxicants (20). The dendrogram shown in Fig. 4 classified the 25 tested chemicals into several distinct clusters. The subgroups with a relative similarity above 60% consisted of closely related chemicals. For example, five metals (Pb2+, Hg2+, Cd2+, As5+, and Zn2+) were clustered in one subgroup, the chlorinated phenol derivatives (2,4-D, 2,4,6-TCP, 2,4,5-T, and PCP) were clustered in another, and the biocides malathion, parathion, and propiconazole were clustered in a third subgroup.

FIG. 4.

Dendrogram for the 25 tested chemicals determined on the basis of GSD clustering by use of the UPGMA. The dendrogram clusters resulted from four replicates.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we describe a biologic strategy allowing qualitative and quantitative identification of toxic chemicals according to their ability to activate certain E. coli promoters. The basis of the strategy was to monitor the specific response of the bacterial tester strains to different toxicants and then to define the parameters which identify the response profiles. In most cases, the correlation between the RR and the logarithm of the concentration of the tested analyte was linear for a certain range of concentrations. Determining these data for each bacterial strain after three periods of incubation enabled the characterization of each tested sample. The identification of unknown toxicants was performed by a computerized comparison of the biologic signatures of the tested analytes to the learning data for all the tested chemicals. The described method provided an accurate identification for more than 90% of the chemicals tested. For hundreds of potential chemicals or more, classification only to families of chemicals would be provided.

Unlike other lux-fused biosensors (8–10, 13, 14, 17, 19, 22), the suggested method overcomes the requirement for a specific recognition probe for each of the tested analytes. By use of the correlations between the RR and the concentrations of the tested analytes, it is also possible to estimate the concentration of a given toxicant.

A good correlation (R2, 0.96) was found between the known and the predicted concentrations of the 25 tested samples. The concentrations of more than 95% of these chemicals were estimated within the range of ±35% of the true concentrations. The accepted variation for other water toxicity tests is ±30% of the mean in a 95% confidence interval (1).

Mixtures of two toxicants assayed at sublethal concentrations showed new biologic signatures and a good correlation (R2, ≥0.85) with the profiles calculated from the individual components (Fig. 3). This algorithm is not based on simple addition of the RRs of the individual components; it takes into account possible synergy between components of mixtures, as previously shown by Van Dyk et al. (27) and Belkin et al. (3), as well as possible combinations of toxicants when one toxicant increases luminescence and the other decreases it. Hence, when the profiles of the individual components are known, it is possible to identify the chemicals in a mixture of toxicants. Nevertheless, small deviations between observed and predicted profiles will always occur, since the described model generalizes the possible patterns of synergy that may occur.

Another advantage of the described approach is the information provided about the modes of action of the toxic chemicals. The described method quantifies the activities of the chemicals as a typical set of 21 channels (biologic signatures) characterizing each toxicant. Hence, similarity between the biologic signatures of the different chemicals represents similarity between these chemicals (Fig. 2). For example, the heavy metals Cd2+, Pb2+, Hg2+, and Zn2+ had similar profiles, the chlorophenoxyacetic acid compounds 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D had similar profiles, and the biocides malathion, parathion, and propiconazole had similar profiles. These similarities were also reflected in the dendrogram based on the calculated distances between the biologic signatures of the different toxicants (Fig. 4). In addition to the similarities between common featured chemicals, different chemicals with similar modes of action were also clustered together, e.g., the clustering of Cd2+ and H2O2 in one subgroup. This phenomenon can be explained by the high level of similarity of their modes of action; both Cd2+ and H2O2 are known activators of the oxidative stress system in different organisms (2, 6, 23).

The strategy described in this report may be useful for prescreening for toxic agents in environmental samples and downstream processes and for prescreening of biologic and fermentation processes for sudden changes in chemical composition. Suspicious findings will need to be verified by more established physical-chemical methods. This strategy may also be used as a simple tool for primary elucidation of the modes of action of toxic chemicals by comparison of the biologic signatures of the studied chemicals to the biologic signatures of well-known chemicals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. A. LaRossa (DuPont) and S. Belkin (Hebrew University) for kindly providing the plasmids; B. J. Bachmann (E. coli Genetic tock Center, Yale University) for kindly providing some E. coli strains; and S. Belkin, N. Ulitzur, S. Yannai, and J. Kuhn for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was conducted in the framework of doctorate studies in the graduate school of the Technion.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, and Water Environment Federation. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. 19th ed. Washington, D.C: American Public Health Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagchi D, Vuchetich P J, Bagchi M, Hassoun E A, Tran M X, Tang L, Stohs S J. Induction of oxidative stress by chronic administration of sodium dichromate [chromium VI] and cadmium chloride [cadmium II] to rats. Free Radical Biol Med. 1997;22:471–478. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00352-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belkin S, Smulski D R, Vollmer A C, Van Dyk T K, LaRossa R A. Oxidative stress detection with Escherichia coli harboring a katG′::lux fusion. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2252–2256. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.7.2252-2256.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belkin S, Smulski D R, Dadon S, Vollmer A C, Van Dyk T K, LaRossa R A. A panel of stress-responsive luminous bacteria for the detection of selected classes of toxicants. Water Res. 1997;31:3009–3016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenthal T. P1 transduction: formation of heterogenotes upon cotransduction of bacterial genes with a P2 prophage. Virology. 1972;47:76–93. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brennen R J, Schiestl R H. Cadmium is an inducer of oxidative stress in yeast. Mutat Res. 1996;356:171–178. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(96)00051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bulich A A. A practical and reliable method for monitoring the toxicity of aquatic samples. Process Biochem. 1982;17:45–47. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burlage R S, Sayler G S, Larimer F. Monitoring of naphthalene catabolism by bioluminescence with nah-lux transcriptional fusions. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:4749–4757. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.4749-4757.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai J, DuBow M S. Use of luminescent bacterial biosensor for biomonitoring and characterization of arsenic toxicity of chromated copper arsenate. Biodegradation. 1997;8:105–111. doi: 10.1023/a:1008281028594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Condee C W, Summers A O. A mer-lux transcriptional fusion for real-time examination of in vivo gene expression kinetics and promoter response to altered superhelicity. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:8094–8101. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.24.8094-8101.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foulds J, Chai T. Isolation and characterization of isogenic E. coli strains with alterations in the level of one or more major outer membrane proteins. Can J Microbiol. 1979;25:423–427. doi: 10.1139/m79-065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton M A, Russo R C, Thurston R V. Trimmed Spearman-Karber method for estimating median lethal concentrations in toxicity bioassays. Environ Sci Technol. 1977;11:714–719. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heitzer A, Malachowsky K, Thonnard J E, Bienkowski P R, White D C, Sayler G S. Optical biosensor for environmental on-line monitoring of naphthalene and salicylate bioavailability with an immobilized bioluminescent catabolic reporter bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1487–1494. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1487-1494.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King J M H, DiGrazia P M, Applegate B, Burlage R, Sanseverino J, Dunbar P, Larimer F, Sayler G S. Rapid, sensitive bioluminescent reporter technology for naphthalene exposure and biodegradation. Science. 1990;249:778–781. doi: 10.1126/science.249.4970.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menzel R. A microtiter plate-based system for semiautomated growth and assay of bacterial cells for β-galactosidase activity. Anal Biochem. 1989;181:40–50. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramanathan S, Shi W, Rosen B P, Daunert S. Sensing antimonite and arsenite at the subattomole level with genetically engineered bioluminescent bacteria. Anal Chem. 1997;69:3380–3384. doi: 10.1021/ac970111p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogowsky P M, Close T J, Chimera J A, Shaw J J, Kado C I. Regulation of the vir genes of Agrobacterium tumefaciens plasmid pTiC58. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5101–5112. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.11.5101-5112.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selifonova O, Burlage R, Barkay T. Bioluminescent sensors for detection of bioavailable Hg(II) in the environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3083–3090. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.9.3083-3090.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sneath P H A, Sokal R R. Numerical taxonomy: the principles and practice of numerical classification. W. H. New York, N.Y: Freeman & Co.; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens J. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. Hillsdale, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1992. pp. 273–302. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sticher P, Jaspers M C M, Stemmler K, Harms H, Zehnder A J B, Van Der Meer J R. Development and characterization of a whole-cell bioluminescent sensor for bioavailable middle-chain alkanes in contaminated groundwater samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4053–4060. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.4053-4060.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stohs S J, Bagchi D. Oxidative mechanisms in the toxicity of metal ions. Free Radical Biol Med. 1995;18:321–336. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00159-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ulitzur S. Bioluminescence test for genotoxic agents. Methods Enzymol. 1986;133:264–274. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)33072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Dyk T K, Belkin S, Vollmer A C, Smulski D R, Reed T R, LaRossa R A. Fusions of Vibrio fischeri lux genes to Escherichia coli stress promoters: detection of environmental stress. In: Campbel A K, Kricka L J, Stanley P E, editors. Bioluminescence and chemiluminescence: fundamentals and applied aspects. Chichester, West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 1994. pp. 147–150. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Dyk T K, Majarian W R, Konstantinov K B, Young R M, Dhurjati P S, LaRossa R A. Rapid and sensitive pollutant detection by induction of heat shock gene-bioluminescence gene fusions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1414–1420. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1414-1420.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Dyk T K, Reed T R, Vollmer A C, LaRossa R A. Synergistic induction of the heat shock response in Escherichia coli by simultaneous treatment with chemical inducers. J Biotechnol. 1995;177:6001–6004. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.6001-6004.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Dyk T K, Smulski D R, Reed T R, Belkin S, Vollmer A C, LaRossa R A. Responses to toxicants of an Escherichia coli strain carrying a uspA′::lux genetic fusion and an E. coli strain carrying a grpE′::lux fusion are similar. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4124–4127. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.4124-4127.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zharkikh A A, Rzhetsky A Y, Morosov P S, Sitnikova T L, Krushkal J S. Vostorg: a package of microcomputer programs for sequence analysis and construction of phylogenetic trees. Gene. 1991;101:251–254. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90419-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]