Video

A 13-month-old boy presented to the emergency department with drooling, refusal to eat, and a mild fever of 38°C. The mother reported that the patient initially choked on a rock, which had resolved. The child was vomiting, drooling, and was increasingly fussy since the episode; however, the mother denied witnessing any stridor.

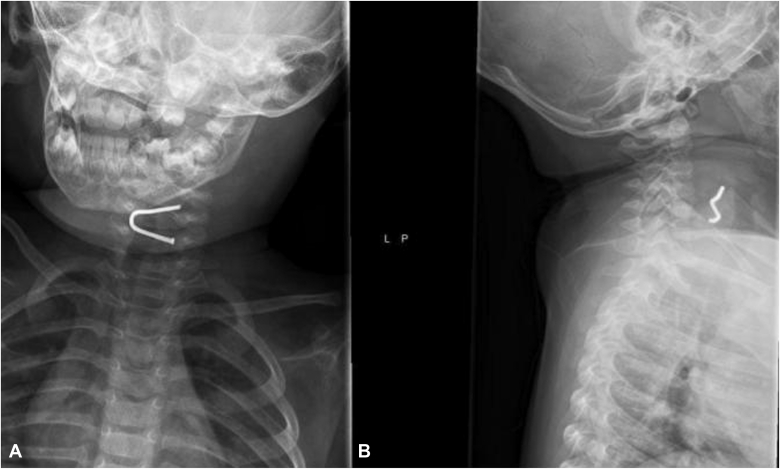

A physical examination demonstrated an erythematous pharynx without exudates or other lesions. Radiography was performed and showed a U-curved nail in the upper esophagus on the posteroanterior view (Fig. 1) and a multiangulated nail on the lateral view. Tetanus immunization was not administered since the patient had a recent documented vaccine. The patient was intubated to protect his airway, and an initial attempt was made by the otolaryngology team to remove the nail with direct laryngoscopy, but this was unsuccessful. The gastroenterology team was subsequently consulted to remove the nail endoscopically.

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) views of the patient’s neck showing the curved nail and its multiangulated shape.

Using a pediatric gastroscope, we visualized a 1-cm defect in the posterior esophagus at the upper esophageal sphincter (UES), likely from the nail’s pressure on the soft tissue and recurrent swallowing by the patient (Fig. 2). Forceps were used to splay open the defect, which demonstrated muscle injury without any perforation. The gastroscope was advanced farther with carbon dioxide insufflation, and the foreign body was found in the mid-esophagus (Fig. 3). The nail was grasped with the pediatric biopsy forceps and was slowly pulled up into the upper esophagus. Once the nail reached the UES, it became embedded and stuck in the defect (Fig. 4). Attempts were made to pull the nail up or side to side, but this caused more trauma to the tissue. A foreign body retrieval hood was placed on the pediatric gastroscope; however, it could not move beyond the UES because of its narrow lumen. A distal attachment was also not used for this reason. After studying the nail more carefully, it became clear that by capturing the inferior portion of the U-shaped nail and lifting it up toward the gastroscope, the angulation would be ideal for removal.

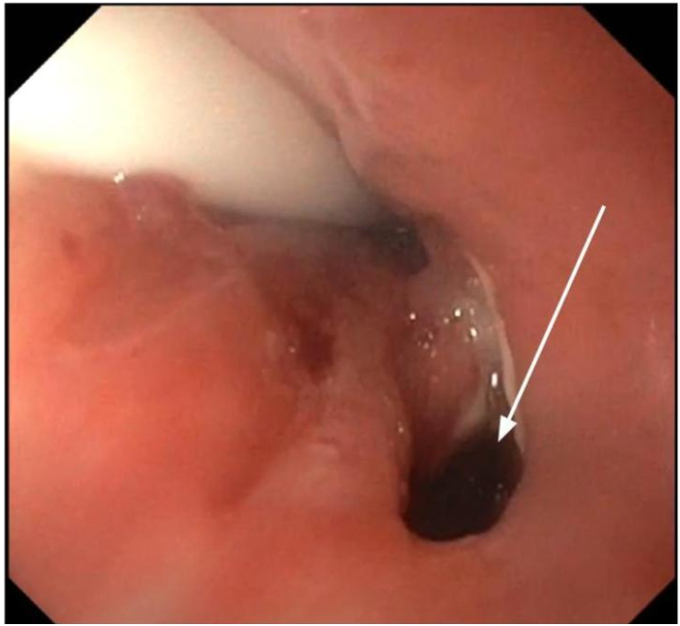

Figure 2.

Endoscopic demonstration of a weakening of the musculature in the posterior upper esophagus, causing the defect shown (white arrow).

Figure 3.

Endoscopic view of the foreign nail in the mid-esophagus.

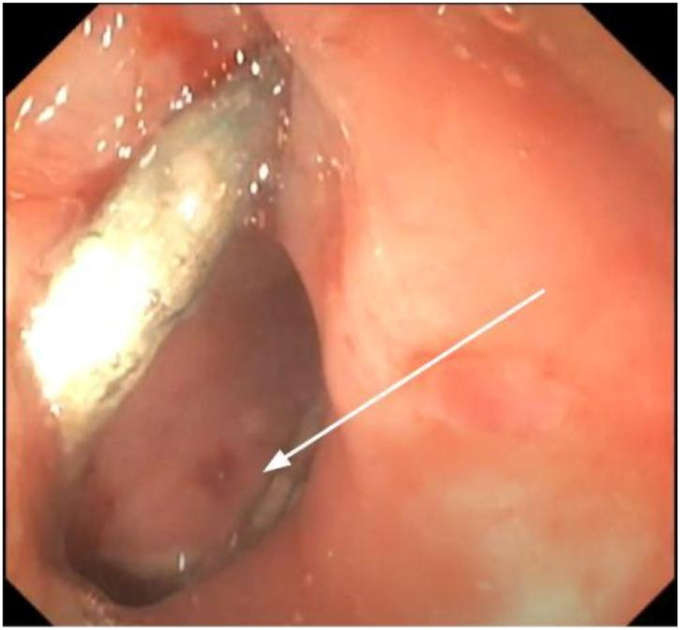

Figure 4.

U-shaped nail stuck in the posterior wall defect (white arrow) in the upper esophagus.

The nail managed to be pulled out past the esophagus; however, it became lodged in the mouth. Otolaryngology forceps were then used to grasp the nail and remove it from the patient’s mouth (Fig. 5). Fluoroscopy images were performed afterward, which confirmed the accumulation of contrast in the esophageal defect, but no leaks were found (Fig. 6). The patient was extubated and monitored with a nasogastric tube in place for feeding and with a regimen of ampicillin-sulbactam. Three days after the procedure, a CT scan demonstrated that the soft tissue defect was smaller and improving. The nasogastric tube was removed and the patient was advanced to a clear-liquid diet. Antibiotics were switched to amoxicillin-clavulanate, and he was discharged 5 days after his procedure on a regular diet.

Figure 5.

Whole nail removed from the patient.

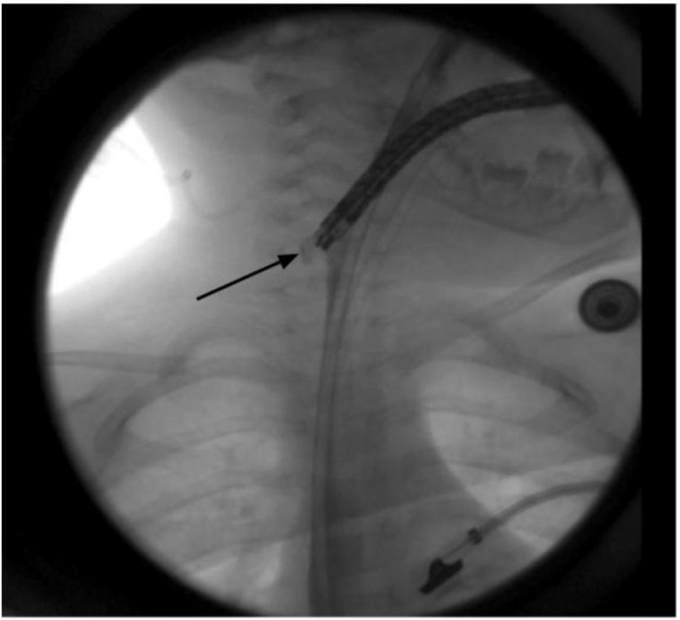

Figure 6.

Fluoroscopic image of esophageal defect (black arrow).

This case provides a scenario in which the contour of an ingested foreign body influenced its removal from the upper GI tract. Patience and due diligence to study the object’s shape were key to successfully removing this oddly shaped nail from this toddler’s esophagus. A foreign body retrieval hood may sometimes be used, although it may not be able to cross the small UES in toddlers and young children. Care should be taken to not force the hood if there is resistance. Attempts to remove the foreign body in different directions should be considered to assess the best path for endoscopic removal (Video 1, available online at www.videogie.org). The mother provided informed consent to this publication.

Disclosure

All authors disclosed no financial relationships.

Supplementary data

Pediatric endoscopic nail retrieval.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Pediatric endoscopic nail retrieval.