Abstract

The insecticidal activity of Bacillus thuringiensis is due primarily to Cry and Cyt proteins. Cry proteins are typically toxic to lepidopterous, coleopterous, or dipterous insects, whereas the known toxicity of Cyt proteins is limited to dipterans. We report here that a Cyt protein, Cyt1Aa, is also highly toxic to the cottonwood leaf beetle, Chrysomela scripta, with a median lethal concentration of 2.5 ng/mm2 of leaf surface for second-instar larvae. Additionally, we show that Cyt1Aa suppresses resistance to Cry3Aa greater than 5,000-fold in C. scripta, a level only partially overcome by Cry1Ba due to cross-resistance. Studies of the histopathology of C. scripta larvae treated with Cyt1Aa revealed disruption and sloughing of midgut epithelial cells, indicating that its mechanism of action against C. scripta is similar to that observed in mosquito and blackfly larvae. These novel properties suggest that Cyt proteins may have an even broader spectrum of activity against insects and, owing to their different mechanism of action in comparison to Cry proteins, might be useful in managing resistance to Cry3 and possibly other Cry toxins used in microbial insecticides and transgenic plants.

Many species of the order Coleoptera, the beetles, are important pests of stored grains, vegetable and field crops, ornamental plants, turf grasses, and forests (19). These insects are usually controlled with synthetic chemical insecticides. However, the development of insecticide resistance in target populations and concern about the detrimental effects of these chemicals on nontarget arthropods, the environment, and human health have spurred interest in alternative insect control agents.

Among the most promising alternatives are bacterial insecticides and insecticidal transgenic plants based on endotoxin proteins of the spore-forming bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis. Sporulating cells of B. thuringiensis synthesize parasporal inclusions comprised of one or more insecticidal proteins, referred to commonly as δ-endotoxins or insecticidal crystal proteins. These proteins fall into two unrelated groups, Cry proteins and Cyt proteins (16). In a susceptible host, the intoxication pathways are similar for all Cry toxins, requiring ingestion, solubilization, and enzymatic activation by midgut proteases (20). Activated toxin molecules bind to glycoprotein receptors on the midgut epithelium microvillar membrane and form pores or lesions leading to osmotic swelling, cell lysis, and damage to the midgut-hemocoel barrier, resulting in death (20, 21, 30). Cyt (cytolytic) toxins also cause midgut cell lysis, although their primary affinity appears to be for lipids in the microvillar membrane (22, 26, 35). In bacterial insecticides, sporulated cultures of B. thuringiensis rich in δ-endotoxins serve as the primary active component, whereas insecticidal transgenic plants are genetically engineered to express wild-type or modified cry genes inside plant tissues.

Isolates of B. thuringiensis toxic to lepidopterous insects have been known for almost 100 years and have been in commercial use for more than 4 decades. However, the first isolate with significant toxicity to coleopterous insects, Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. morrisoni (strain tenebrionis) was discovered relatively recently, in 1983 in Germany (25). Subsequently, it was shown that the toxicity of this and similar isolates was due to a related group of 70-kDa insecticidal crystal proteins designated type Cry3 to indicate toxicity to coleopterous insects (25). Cry3Aa, the first protein from this group to be characterized, is toxic to the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (3, 20). This spectrum of activity led to the rapid commercialization of B. thuringiensis subsp. morrisoni (strain tenebrionis)-based insecticides for control of this pest on potatoes and related crops. Registration of Cry3Aa-based insecticides soon followed for other coleopterans, including Chrysomela scripta, the cottonwood leaf beetle, a native pest of cottonwood and hybrid poplar trees grown on plantations (2, 4). In addition, the gene encoding the Cry3Aa protein was used to construct beetle-resistant transgenic potato plants (29), now produced commercially in the United States.

Bacterial insecticides and insecticidal transgenic plants are considered by many entomologists and growers to be selective, environmentally compatible technologies, especially in comparison to broad-spectrum chemical insecticides. However, adaptation of insect pest populations to insecticides, i.e., resistance, is the inevitable consequence of intensive and prophylactic use, and Cry toxins are no exception. Resistance to B. thuringiensis Cry1A proteins used in bacterial insecticides to control lepidopterous pests is known to have been established in field populations of the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella, in several regions of the world (15, 31, 34). Moreover, resistance to Cry1 proteins used and being considered for use in transgenic plants to control lepidopterous pests has developed in the laboratory (12, 13, 28). Importantly, it is known that high levels of resistance to one Cry protein, Cry1Ac, can result in substantial cross-resistance to other Cry proteins (12). With respect to beetles, laboratory studies show that L. decemlineata (36) and C. scripta (3) can develop resistance to Cry3 proteins quickly under heavy selection pressure.

The demonstration that resistance to Cry proteins can develop quickly has raised concern over the widespread use of insecticidal transgenic plants based on these proteins. This concern is so great that, despite preliminary success with transgenic cotton, the Union of Concerned Scientists and several environmental groups oppose the sale of such plants until resistance management strategies are developed (18). Strategies under development include the periodic rotation of plants that produce different Cry toxins, the use of mixtures of Cry toxins in the same plant, the combination of Cry toxins with synergists, and the use of refugia in which susceptible plants are planted along with insect-resistant plants (1, 11, 27, 32, 33).

The task of developing B. thuringiensis resistance management strategies for beetle pests is particularly challenging because the number and diversity of toxins is limited to four closely related Cry3 proteins. Thus, the chance for the development of cross-resistance is high. We therefore undertook a search for other proteins that might be used for managing resistance to Cry3 toxins. We evaluated Cry1Ba, known to be toxic to coleopterans (7), and Cyt1Aa, originally isolated from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis and previously known to be toxic only to mosquitoes and related dipterans (16, 20, 22). We show here that Cyt1Aa is highly toxic to C. scripta. Additionally, we show that Cyt1Aa suppresses high levels of resistance in C. scripta selected for resistance to Cry3Aa. Lastly, we demonstrate substantial cross-resistance to Cry1Ba in the Cry3Aa-resistant strain, despite only 38% amino acid identity between these two toxins. These results demonstrate that resistance and cross-resistance to Cry proteins also develop in coleopterous insects, yet they also suggest that δ-endotoxins with different mechanisms of action, used in rotation or together, may provide an additional and more effective resistance management strategy than that currently under development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and endotoxin production.

The source of all Cyt1Aa preparations was a recombinant strain of B. thuringiensis that produced only Cyt1Aa (39). The Cry3Aa toxin was isolated from the type strain of B. thuringiensis subsp. tenebrionis, obtained from the German Stock Culture Collection. The source of the Cry1Ba toxin was a strain of B. thuringiensis subsp. thuringiensis obtained from Ecogen, Inc. (Langhorne, Pa.). These toxins are referred to herein as Cyt1A, Cry3A, and Cry1B, respectively. After growth and sporulation on liquid media as described previously (7, 39), the supernatant from each culture was discarded, and the slurry of spores, cellular debris, and crystals was either lyophilized to produce spore-crystal powders or subjected to centrifugation through sucrose (24) or Renografin-60 gradients (Squibb Diagnostics, New Brunswick, N.J.) to produce purified crystals.

Preparation of solubilized and purified endotoxins.

Cyt1A crystals in spore-crystal or purified crystal preparations were solubilized in 50 mM Na2CO3–10 mM dithiothreitol at pH 10.5 for 4 h at 37°C with intermittent shaking. Particulates were then sedimented by centrifugation for 30 s in a microcentrifuge, and the supernatant was bioassayed after the protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method with a commercial test kit (Bio-Rad). Cyt1A was further purified, where needed, by column chromatography essentially as described previously (38). Cry3A and Cry1B preparations were solubilized and purified as described previously (7, 23). Relative quantities of toxins, especially Cyt1A, in the supernatant and pellets were determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-gel electrophoresis as described previously (17, 37).

Bioassays.

Bioassays were done by applying a 1-μl droplet of 22% sucrose with a known quantity of a particulate or soluble B. thuringiensis preparation to a 4-mm-diameter hybrid poplar (Populus × euramericana ‘Eugenii’) leaf disc on top of 2% agar (Gelcarin) in 24-well tissue culture plates. Second-instar larvae, one per well, were placed in each well, kept there for 24 h, and then transferred to fresh foliage. The control buffer was either 50 mM Na2CO3–10 mM dithiothreitol (pH 10.5) or 10 mM NH4(CO3)2–10 mM EDTA (pH 10.4). Median (50%) lethal concentrations (LC50s) were calculated 96 h after treatment with a minimum of 12 larvae per dose and six dilutions per toxin; experiments were replicated three times. LC50s were determined only for preparations which showed moderate to high mortality in the screening bioassays. Maximum-likelihood estimates of LC50s were calculated by probit analysis (performed according to instructions provided by LeOra Software, Berkeley, Calif.).

Histology.

Midguts from second-instar larvae treated by feeding them an LC50 of Cyt1A for 24 h on a leaf disc were dissected 4 days posttreatment and fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde–0.25% sucrose for at least 2 h. After fixation, the tissue was washed for 15 min in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer with 0.25% sucrose and for 15 min in cacodylate buffer with 0.13% sucrose, transferred to cacodylate buffer without sucrose at 4°C overnight, and then further fixed, dehydrated, and embedded in Epon-Araldite. Thick (1-μm) sections were cut on a Sorvall model MT5 microtome and examined by phase-contrast microscopy and photographed with a Zeiss model III photomicroscope.

RESULTS

Initial detection of Cyt1A toxicity.

The toxicity of Cyt1A was evaluated with both Cry3A-sensitive and Cry3A-resistant strains of C. scripta. Preparations evaluated included (i) a powder of the lyophilized Cyt1A spore-crystal complex suspended in water, (ii) the same powder after solubilization in alkali, (iii) the supernatant and (iv) pellet obtained after solubilization of the powder, and (v) Cyt1A purified on a DEAE column. Controls included alkali-solubilized powders of the acrystalliferous B. thuringiensis host strain used to produce the Cyt1A recombinant, with and without the expression vector (pHT3101), in the latter two cases lacking the cyt1A gene. Other controls included water suspensions and alkali-solubilized preparations from the same B. thuringiensis host strain transformed with a modified pHT3101 expression vector that produced the Cry11A protein, water, and the alkaline buffer.

In initial screening bioassays, the toxicity of the Cyt1A spore-crystal powder suspension in water was low, and mortality of larvae sensitive to Cry3A was only 80% at a concentration of 900 ng of protein/mm2 of leaf tissue. However, the suspension of alkali-solubilized Cyt1A spore-crystal complex was toxic to both strains of C. scripta at about 70 ng of protein/mm2 of leaf tissue. The supernatant, enriched with Cyt1A, was more toxic than the whole suspension, with larval mortality averaging almost 80% in the two C. scripta strains (data not shown). The pellet, which contained little Cyt1A, did not cause significant mortality. The highest mortality was obtained with Cyt1A purified by column chromatography, in which case larval mortality was greater than 70% at about 20 ng of protein/mm2 of leaf tissue for both the Cry3A-susceptible and Cry3A-resistant strains (data not shown). Alkali-solubilized fractions of the B. thuringiensis host strain spore-vector and spore complexes, serving as primary controls, were not toxic. In addition, Cry11A, another mosquitocidal toxin, produced in the same B. thuringiensis host was not toxic.

Quantification of toxicity.

The toxicity of Cyt1A to C. scripta, evident in the screening bioassays, was quantified by determining LC50s for the crystal and column-purified Cyt1A preparations. For comparative purposes, we also determined the toxicity of Cry3A and Cry1B as crystals and after solubilization in alkali. For the Cry3A-sensitive strain of C. scripta, all three solubilized endotoxins exhibited high toxicity, with LC50s of 0.9, 2.5, and 3.0 ng/mm2 for Cry3A, Cyt1A, and Cry1B, respectively (Table 1). The crystals of all three toxins were at least twofold less toxic than the solubilized forms (Table 1). Markedly different toxicities were obtained for the three toxins against the Cry3A-resistant beetles. The LC50 for the crystal preparation of Cry3A was >9,000 ng of protein/mm2, yielding a resistance ratio of >5,000. The LC50 for a comparable preparation of Cry1B was 2,370 ng of protein/mm2, yielding a resistance ratio of 400 (Table 1). In contrast, there was little difference between the toxicities of soluble Cyt1A for the Cry3A-susceptible and Cry3A-resistant beetles, with the LC50 for the resistant strain being 3.9 ng of protein/mm2, yielding a resistance ratio of 1.2 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Toxicities of Cyt1A, Cry3A, and Cry1B to Cry3A-sensitive and Cry3A-resistant cottonwood leaf beetle (C. scripta) larvae

| δ-Endotoxin | Phase | Cry3A sensitive

|

Cry3A resistant

|

Resistance ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC50 (ng/mm2) | 95% FLa | Mean slope ± SE | LC50 (ng/mm2) | 95% FL | Mean slope ± SE | |||

| Cyt1A | Crystalline | 132.6 | 108–157 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 380 | 307–457 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 3.0 |

| Solution | 2.5 | 1.8–3.4 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 3.9 | 2.9–5.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.2 | |

| Cry1B | Crystalline | 5.9 | 2.9–9.6 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 2,370 | 1,303–8,530 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 400 |

| Solution | 3.0 | 2.0–4.2 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 292.4 | 181–450 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 100 | |

| Cry3A | Crystalline | 1.8 | 0.8–3.3 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | >9,000 | NA | NA | >5,000 |

| Solution | 0.9 | 0.7–1.1 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | NAb | NA | NA | NA | |

FL, fiducial limits.

NA, not applicable; values could not be determined, owing to the very high levels of resistance.

Histopathology.

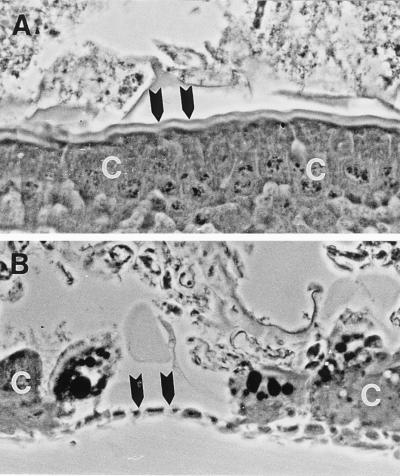

It is well known that both Cry and Cyt toxins in vivo cause the lysis of insect midgut epithelial cells and lead to the sloughing of toxin-damaged cells from the basement membrane of the midgut epithelium. To determine whether the Cyt1A protein caused such damage in C. scripta larvae, second-instar larvae treated with this protein were examined by histological techniques. These studies showed extensive damage to and sloughing of midgut cells at 4 days after treatment with the Cyt1A toxin (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Midgut lesion caused by the Cyt1A protein in a second-instar cottonwood leaf beetle (C. scripta) larva. (A) Section through the midgut epithelium of a control larva. The arrowheads point to the microvillar brush border of normal midgut epithelial cells (C). (B) Similar section through a larva 18 h after being treated with purified Cyt1A (approximately 4 ng/mm2 of leaf tissue). The arrowheads point to an area of the midgut epithelium from which the cells have sloughed; unaffected epithelial cells are marked (C). Lesions such as this one are typical of those caused by Cyt1A in mosquito and blackfly larvae. Magnification, ×350.

DISCUSSION

We have shown here that Cyt1A is toxic to larvae of C. scripta and suppresses high levels of Cry3A resistance. These findings may have relevance for the use of Cyt proteins in pest control. For example, one possibility is that these proteins may be toxic to other, equally different pest species. Endotoxins of B. thuringiensis with a high toxicity to insects of more than one order are rare and prior to this report were limited to Cry2Aa, Cry1B, and Cry1Ac (7, 14, 16). Thus, Cyt proteins alone may have greater utility as safe insecticides than is currently realized. Several Cyt proteins are known (16, 21, 24) but have received little evaluation as insecticides because their toxicity spectrum in vivo was thought to be limited to dipterans (16). Our results indicate that Cyt proteins should receive more thorough evaluation. Our results also support the importance of solubilizing, and perhaps activating, endotoxins prior to bioassay to optimize detection of activity (7, 22). CytA dissolves readily under alkaline conditions, especially at pH 8 or higher, but remains in crystalline form at neutral or slightly acidic pH. The midgut lumen pH of many coleopterous insects is slightly acidic, and this probably accounts for the low toxicity of CytA fed in crystalline form to C. scripta larvae.

Cyt proteins, with their unique structure and mode of action, might also play a critical role in managing the resistance of insect populations to Cry toxins in both microbial insecticides and transgenic plants. Resistance management strategies proposed for delaying resistance, or overcoming resistance once it develops, involve the deployment of δ-endotoxins in rotation or in mixtures (27, 33). One potential flaw with current tactics is their almost exclusive dependence on Cry proteins. These proteins have considerable identity at the amino acid sequence level and appear to have similar mechanisms of action. As a result, cross-resistance among Cry proteins may become the rule rather than the exception (3, 12, 13). Thus, replacing a protein like Cry3A with Cry1B in a control program aimed at managing C. scripta would be ineffective, based on the high level of cross-resistance observed in the present study. However, our data suggest that Cyt1A could be a very effective component of a resistance management strategy for Cry3A, owing to the virtual lack of cross-resistance (Table 1). This lack of significant cross-resistance between Cyt and Cry proteins may result from fundamental differences in their mechanisms of action (20, 21, 35).

Cyt proteins may play an even more important long-term role in managing resistance to Cry proteins. The insecticidal activity of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis, the subspecies in microbial insecticides used for mosquito and blackfly control, is due to a combination of endotoxins including Cyt1A, Cry4A, Cry4B, and Cry11A (15). Cyt1A is toxic to dipterans and, in addition synergizes the Cry proteins in B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis against mosquitoes (8, 9, 38, 40). Though B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis has been used in mosquito and blackfly control programs for more than a decade, no resistance is known (5, 6). This lack of resistance may result from the complexity of its toxin mixture. Perhaps of greater importance is the possibility, based on recent evidence, that Cyt1A plays a key role in delaying the development of resistance to the Cry proteins of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis (10, 37). Populations of the mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus exposed to combinations of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis toxins that contained Cyt1A developed increases of resistance of only 3-fold after 28 generations of selection, whereas in its absence, increases of resistance ranged from 90- to 900-fold at the LC95 depending on the complexity of the toxin combination tested (10). Furthermore, more recent studies have shown that Cyt1A, combined with Cry4A and -B, or Cry11A, can suppress resistance to these proteins in C. quinquefasciatus (37). If additional studies underway confirm Cyt1A’s role in delaying and/or suppressing resistance to Cry proteins, this and other Cyt proteins may be useful for engineering resistance management directly into microbial insecticides and transgenic plants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. J. Johnson, D. L. Miller, and N. Koller for assistance with these studies.

This research was supported by grants to B.A.F. from the USDA (grant 92-37302-7603), the University of California Systemwide Biotechnology Research and Education Program (grant 96-21), and the UC Mosquito Research Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alstad D N, Andow D A. Managing the evolution of insect resistance to transgenic plants. Science. 1995;268:1894–1896. doi: 10.1126/science.268.5219.1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer L S. Response of the cottonwood leaf beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) to Bacillus thuringiensis var. san diego. Environ Entomol. 1990;19:428–431. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer L S. Resistance: a threat to the insecticidal crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis. Fla Entomol. 1995;78:414–443. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer L S, Pankratz H S. Ultrastructural effects of Bacillus thuringiensis var. san diego on midgut cells of the cottonwood leaf beetle. J Invertebr Pathol. 1995;60:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becker B, Margalit J. Use of Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis against mosquitoes and blackflies. In: Entwistle P F, Cory J S, Bailey J S, Higgs S, editors. Bacillus thuringiensis, an environmental biopesticide: theory and practice. Chichester, England: Wiley & Sons; 1993. pp. 147–170. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker N, Ludwig M. Investigations on possible resistance in Aedes vexans after a 10-year application of Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1993;9:221–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley D, Harkey A M, Kim M K, Biever K D, Bauer L S. The insecticidal CryIB crystal protein of Bacillus thuringiensis ssp. thuringiensis has dual specificity to coleopteran and lepidopteran larvae. J Invertebr Pathol. 1995;65:162–173. doi: 10.1006/jipa.1995.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chilcott C N, Ellar D J. Comparative toxicity of Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis crystal proteins in vivo and in vitro. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:2551–2558. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-9-2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crickmore N, Bone E, Williams J A, Ellar D J. Contribution of the individual components of the δ-endotoxin crystal to the mosquitocidal activity of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;131:249–254. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Georghiou G P, Wirth M C. Influence of exposure to single versus multiple toxins of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis on development of resistance in the mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1095–1101. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1095-1101.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gould F. Evolutionary biology and genetically engineered crops: consideration of evolutionary theory can aid in crop design. BioScience. 1988;38:26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gould F, Martinez-Ramirez A, Anderson A, Ferre J, Silva F J, Moar W J. Broad-spectrum resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins in Heliothis virescens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7986–7990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.7986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gould F, Anderson A, Reynolds A, Baumgarner L, Moar W J. Selection and genetic analysis of a Heliothis virescens (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) strain with high levels of resistance to some Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. J Econ Entomol. 1995;88:1545–1559. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haider M Z, Knowles B H, Ellar D J. Specificity of Bacillus thuringiensis var. colermi insecticidal δ-endotoxin is determined by differential proteolytic processing of the protoxin by larval gut proteases. Eur J Biochem. 1986;156:531–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hama H, Suzuki K, Tanaka H. Inheritance and stability of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis formulations of the diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella L. (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutidae) Appl Entomol Zool. 1992;27:355–362. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Höfte H, Whiteley H R. Insecticidal crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:242–255. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.2.242-255.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibarra J E, Federici B A. Isolation of a relatively nontoxic 65-kilodalton protein inclusion from the parasporal body of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis. J Bacteriol. 1986;165:527–533. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.2.527-533.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaiser J. Pests overwhelm Bt cotton crop. Science. 1996;273:423. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keller B, Langenbruch G-A. Control of coleopteran pests by Bacillus thuringiensis. In: Entwistle P F, Cory J S, Bailey J S, Higgs S, editors. Bacillus thuringiensis, an environmental biopesticide: theory and practice. Chichester, England: Wiley & Sons; 1993. pp. 171–191. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knowles B H, Ellar D J. Colloid-osmotic lysis is a general feature of the mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin with different insect specificity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;924:509–518. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knowles B H, Dow J A T. The crystal δ-endotoxins of Bacillus thuringiensis: models for their mechanism of action on the insect gut. Bioessays. 1993;15:469–476. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knowles B H, Blatt M R, Tester M, Horsnell J M, Carroll J, Menestrina G, Ellar D J. A cytolytic δ-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis forms cation-selective channels in planar lipid bilayers. FEBS Lett. 1989;244:259–262. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80540-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koller C N, Bauer L S, Hollingworth R M. Characterization of the pH-mediated solubility of Bacillus thuringiensis var. san diego native delta-endotoxin crystals. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;182:692–699. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90645-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koni P A, Ellar D J. Cloning and characterization of a novel Bacillus thuringiensis cytolytic delta-endotoxin. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:319–327. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieg A, Huger A M, Langenbruch G A, Schnetter W. Bacillus thuringiensis var. tenebrionis: ein neuer gegenüber Larven von Coleopteren wirksamer. Z Angew Entomol. 1983;96:500–508. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, Koni P A, Ellar D J. Structure of the mosquitocidal δ-endotoxin CytB from Bacillus thuringiensis sp. kyushuensis and implications for membrane pore formation. J Mol Biol. 1996;257:129–152. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGaughey W H, Whalon M E. Managing insect resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. Science. 1994;258:1451–1455. doi: 10.1126/science.258.5087.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moar W J, Pusztai-Carey M, Van Faassen H, Bosch D, Frutos R, Rang C, Luo K, Adang M J. Development of Bacillus thuringiensis CryIC resistance by Spodoptera exigua (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2086–2092. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2086-2092.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perlak F J, Stone T B, Muskopf M Y, Petersen L J, Parker G B, McPherson S A, Wyman J, Love S, Reed G, Biever D, Fischhoff D A. Genetically improved potatoes: protection from damage by Colorado potato beetles. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;22:313–321. doi: 10.1007/BF00014938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sangadala S, Walters F W, English L H, Adang M J. A mixture of Manduca sexta aminopeptidase and phosphatase enhances Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal CryIA(c) toxin binding and 86Rb+-K+ efflux in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10088–10092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shelton A M, Robertson J L, Tang J D, Perez C, Eigenbrode S E. Resistance of diamondback moth to Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies in the field. J Econ Entomol. 1993;86:697–705. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabashnik B E. Evolution of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis. Annu Rev Entomol. 1994;39:47–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.54.110807.090518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tabashnik B E. Delaying insect adaptation to transgenic plants: seed mixtures and refugia reconsidered. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B. 1994;255:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tabashnik B E, Cushing N L, Finson N, Johnson M W. Field development of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis in diamondback moth (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) J Econ Entomol. 1990;83:1671–1676. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas W E, Ellar D J. Mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis insecticidal δ-endotoxin. FEBS Lett. 1983;154:362–368. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whalon M E, Miller D L, Hollingworth R M, Grafius E, Miller J R. Selection of a Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) strain resistant to Bacillus thuringiensis. J Econ Entomol. 1993;86:226–233. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wirth M C, Georghiou G P, Federici B A. CytA enables CryIVD endotoxins of Bacillus thuringiensis to overcome high levels of CryIV resistance in the mosquito, Culex quinquefasciatus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10536–10540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu D, Chang F N. Synergism in mosquitocidal activity of 26 and 65 kDa proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis crystal. FEBS Lett. 1985;190:232–236. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu D, Federici B A. A 20-kilodalton protein preserves cell viability and promotes CytA crystal formation during sporulation in Bacillus thuringiensis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5276–5280. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5276-5280.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu D, Johnson J J, Federici B A. Synergism of mosquitocidal toxicity between CytA and CryIVD proteins using inclusions produced from cloned genes of Bacillus thuringiensis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:965–972. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]