Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused significant disruptions to health care services and health impacts on patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) and/or food allergy (FA).

Objective

We evaluated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and disease on AD/FA patients.

Methods

A comprehensive systematic literature search was conducted from December 2019 to 2022. Screening and data extraction were done following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines, and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool, or MMAT, was used to assess risk of bias.

Results

In total, 159 studies were included. Five of 7 studies reported no significant changes in overall incidence or prevalence of AD during the pandemic, although some studies noted an increase in the elderly and infants. Telehealth served as an effective alternative to face-to-face consultations, with mixed levels of patient and provider satisfaction. Dissatisfaction was most marked in patients with more severe disease, who thought that their disease was inadequately managed through telemedicine. Higher levels of general anxiety were recorded in both AD/FA patients and caregivers, and it was more pronounced in patients with severe disease. Most studies reported no significant differences in postvaccination adverse effects in AD patients; however, results were more varied in FA patients.

Conclusion

Our review identified the impact of COVID-19 pandemic- and disease-driven changes on AD/FA patients. Telemedicine is uniquely suited to manage atopic diseases, and hybrid care may be a suitable approach even in the postpandemic era. COVID-19 vaccines and biologics can be safely administered to patients with atopic diseases, with appropriate patient education to ensure continued care for high-risk patients.

Key words: Atopic dermatitis, food hypersensitivity, telemedicine, mental health, hospitalizations, morbidity, severity, coronavirus

At the height of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, health care services saw significant disruptions resulting from the extensive movement restrictions that were implemented to contain the spread of the virus. This included curtailment of many essential services, cancellation of elective procedures with ensuing longer waiting times and delayed access to diagnostic and therapeutic services, and adoption of telemedicine as a mitigation strategy.1,2

The impact of COVID-19 on asthma emergency and hospital admissions as well as asthma control in adults and children has been well documented.3, 4, 5 However, there have been comparatively few studies evaluating its impact on other atopic conditions such as atopic dermatitis (AD) and food allergy (FA).

Pandemic-related disruptions to health care provision and telemedicine may translate to delays in diagnosis and/or treatment of AD and FA. On the one hand, in both adults and children, these may also lead to reduction in access to medications or emergency medical services as well as delays in access to timely oral food challenge (OFC) and oral immunotherapy (OIT) for FA management, which collectively could affect disease control and morbidity.6 On the other hand, more time spent indoors and/or movement restrictions brought about by the pandemic may have positive effects on AD’s severity—for example, through reduced exposure to outdoor triggers, by permitting greater flexibility in work or school schedules that allows better compliance with treatment regimens, and by varying impacts on mental health, which can also affect AD control.

Furthermore, antigenic stimuli such as COVID-19 infection and vaccination have been postulated to cause poorer health outcomes in certain preexisting illnesses by causing disease exacerbations. Treatments for AD and FA, such as biological therapy and immunotherapy, may also affect the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in people with AD and/or FA. The above observations have been published in small case series across different countries, but the full impact of the pandemic on patients with these atopic diseases has not been systematically evaluated.

Given the widespread health care service disruptions brought about by the pandemic, changes to health-seeking behavior, the increasing role of telemedicine, and emerging evidence of impact of COVID-19 disease on AD/FA patients, this could potentially affect health outcomes for AD/FA patients. This review thus aims to systematically evaluate the impact of COVID-19 pandemic-driven changes on AD and FA care, focusing on (1) the impact on AD/FA incidence and prevalence, (2) the impact on AD/FA disease control, morbidity, and treatment disruptions, (3) emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and clinic presentations, and (4) the role of telehealth and alternative initiatives. Moreover, the review also aims to establish the impact of COVID-19 disease and vaccinations in patients with AD/FA, in particular the (5) impact of AD/FA disease and AD/FA treatments on COVID-19 morbidity, (6) COVID-19 vaccination outcomes in AD/FA patients, and (7) mental health, psychological impact, and quality of life (QoL) concerns in AD/FA patients.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was created according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines7 and was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (329173).

Search strategy for identification of studies

A systematic literature search of Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), Scopus, Cochrane Library, and CINAHL was performed on June 16, 2022, and updated in December 2022 with the help of librarians (A.C., M.S.). Searches were limited to studies published between December 2019 and December 2022 to capture studies evaluating the impacts of the current COVID-19 pandemic, which began in December 2019. The reference lists of relevant studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses were searched to identify eligible articles that might have been missed in the original database searches. The complete search terms and strategies can be found in Tables E1-E5 in this article’s Online Repository at www.jaci-global.org.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Detailed eligibility criteria for inclusion are provided in the Methods section in the Online Repository at www.jaci-global.org. In brief, all COVID-19–related studies in AD and/or FA patients from all age groups were considered. All study designs were eligible except case reports, systematic reviews, narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and animal studies, which we excluded. Conference abstracts and letters to editors were included if sufficient data were available for analysis. Only articles written in English or with an English translation were included.

Study selection

Three reviewers (C.N., N.H., W.T.A.) independently screened all records identified from database searches by title and abstracts. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion with a senior researcher (E.T.). The full texts of potentially relevant studies identified from the initial title and abstract screening stage were reviewed by 3 researchers (C.N., N.H., W.T.A.), independently and in parallel, to determine eligibility according to the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria described. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus, and if necessary, arbitration by the senior researcher (E.T.).

Data collection and synthesis

Data were extracted by the first reviewer (C.N., W.T.A.) and then verified by a second reviewer (N.H., K.O.). The extraction process was carried out in Covidence.8

Risk of bias assessment

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) v2018 was used to assess risk of bias across different study designs, namely qualitative, quantitative randomized controlled, quantitative nonrandomized, quantitative descriptive, and mixed methods.9 Detailed MMAT v2018 criteria can be found in the Methods section in the Online Repository. Each study design was scored against 5 criteria; higher scores equate to a lower risk of bias. Studies were assessed for risk of bias by the first reviewer (C.N., W.T.A.) and then verified by the second reviewer (N.H., K.O.). Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion with a senior researcher (E.T.).

Results

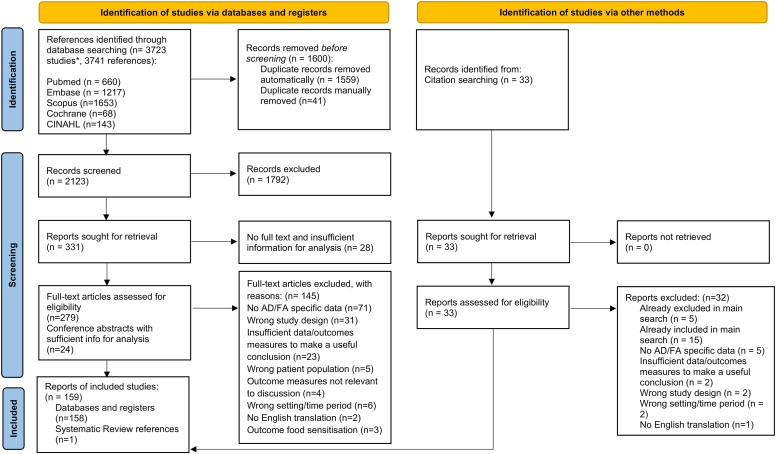

Of the 3723 studies identified, 159 met our eligibility criteria and were included for analysis (Fig 1). Of these studies, 100 reported data on AD, 51 on FA, and 8 on both. Table I provides an overview of the characteristics of the included studies. Detailed demographics of each study can be found in Table E6 in the Online Repository available at www.jaci-global.org. Eleven studies adopted a qualitative or mixed methods study design. The remaining 148 studies were quantitative in nature: 65 nonrandomized observational studies, 1 randomized controlled trial, and 82 descriptive (eg, surveys, chart reviews, case series). Quality assessments of these studies using MMAT v2018 are summarized in Table E7 in the Online Repository. Because all the studies were highly heterogenous, no meta-analyses were performed, and the findings are reported qualitatively in this systematic review.

Fig 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of included studies. Original reference count was 3741; however, 18 studies were merged with another related study (eg, conference abstracts of a published article), giving a total of 3723 studies. After removing duplicates, 2123 unique abstracts/studies were eligible for screening. An additional 33 records were also obtained by citation searching. In total, 159 studies were eventually included.

Table I.

Characteristics in 159 included studies

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Atopic condition reported | |

| AD | 100 (62.9) |

| FA | 51 (32.1) |

| Both | 8 (5.0) |

| Population group∗ | |

| Children/adolescents | 29 |

| Adults | 62 |

| Mixed ages | 40 |

| Caregivers/parents | 19 |

| Health care professionals, allergists, teachers | 12 |

| Age group not stated | 6 |

| Quality assessment scoring† | |

| 2 points | 10 (6.3) |

| 3 points | 25 (15.7) |

| 4 points | 67 (42.1) |

| 5 points | 57 (35.8) |

| Country or region of study | |

| Asia | 20 (12.6) |

| Europe | 52 (32.7) |

| Australia | 1 (0.6) |

| North America | 53 (33.3) |

| South America | 3 (1.9) |

| Middle East | 18 (11.3) |

| Africa | 1 (0.6) |

| Global/multiple countries | 11 (6.9) |

There is some overlap (some studies have both caregivers and children), so this will not total to 159 studies.

MMAT v2018 was used for risk of bias analysis. Each study design was scored against 5 criteria, with higher scores indicating a lower risk of bias.

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic–driven changes on AD and FA care

Impact on AD and FA diagnosis: Incidence and prevalence

Incidence or prevalence data were reported in 6 studies for AD10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and 1 study on both AD and FA.16 Because studies were mostly heterogeneous, no meta-analyses were performed. In the general population, 5 studies in Cameroon,10 3 in Korea,11, 12, 13 and 1 in the United States14 reported no statistically significant changes in the incidence or prevalence of AD during the pandemic. However, Mandeng Ma Linwa et al10 in Cameroon noted a significantly increased prevalence of eczema in the elderly population (odds ratio, 1.373; 95% confidence interval, 1.022-1.844) compared to the pre–COVID-19 era (March 1, 2019, to February 29, 2020). In Thailand, Hanthavichai and Laopakorn15 reported the highest prevalence of eczematous dermatitis in senile outpatients (prepandemic eczema 24.6%, AD 0.6%; pandemic eczema 39.9%, AD 0.4%), although the distribution of the most prevalent dermatologic disorders did not change during the pandemic.

Hurley et al16 demonstrated higher rates of AD and egg sensitization in a cohort of Irish infants born during the COVID-19 pandemic period (March to May 2020) compared to infants in a birth cohort born before the pandemic. The increased rate of AD was hypothesized to be due to an altered infant microbiome resulting from reduced infective encounters through family members, day nursery, and school attendance. Other reasons such as antibiotic receipt and breast-feeding were also postulated. However, the higher rate of egg sensitization did not translate to a higher incidence of egg allergy at 12 months compared to a national prepandemic birth cohort group. This was attributed to the continuation of early introduction of baked egg soon after diagnosis,17 a practice that enhances the rate of tolerance in most infants.

Impact on AD and FA disease control and treatment disruptions

Fourteen studies reported outcomes on disease control and severity of AD during the pandemic. Some showed an overall improvement (n = 4),18, 19, 20, 21 while others showed no change (n = 7)22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 or deterioration (n = 3)29, 30, 31 of, respectively, AD control and severity.

In those who experienced improvement in disease control, one reason was continuation of essential therapy such as dupilumab. A cross-sectional study by Chiricozzi et al19 involving 1831 adolescent AD patients with moderate to severe AD found a statistically significant disease improvement in patients who continued dupilumab compared to those who ceased therapy. Improved AD control was also separately attributed to reduced trigger exposure (heat, sweating, physical activity) and more time and flexibility for skin care treatment, thus resulting in better treatment compliance during COVID-19 lockdown periods in other studies.18,32

Three studies reported an increased frequency of disease flares and severity during the pandemic.29, 30, 31 These findings were typically correlated with treatment discontinuation, particularly dupilumab,19 as well as longer AD history and self-isolation.29 Worsening AD facial flares were also associated with increased use of face masks and other personal protective equipment.33, 34, 35, 36 A daily personal protective equipment wearing time of more than 6 hours in those with preexisting skin conditions like acne and AD was strongly associated with adverse skin manifestations at various locations.37 Interestingly, analyses of transepidermal water loss in AD health care workers showed higher transepidermal water loss area under the curve after use of hand sanitizer and soap compared to those without AD, suggesting that chronic use of hand sanitizers may further worsen impaired skin barrier function.38 The Eczema Area and Severity Index scores in adult AD patients also showed an increase from 2.42 ± 1.10 to 5.10 ± 1.57 over a 1-month period during the first lockdown in Italy.39 However, there was no significant change in skin lesion severity or symptom scores (Eczema Area and Severity Index and Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis) in AD patients who had acquired COVID-19 infection.19,27,28,40

However, in patients with severe dyspnea—a surrogate measure of increased COVID-19 infection severity—a substantial proportion of patients reported development of mild or severe skin lesions and itching (respectively, mild/severe skin lesions in 25%/11%; mild/severe itching in 36%/12%). This could be attributed to higher IL-13 levels in patients with severe COVID-19.41 IL-13 is a critical TH2 cytokine linked to AD exacerbations, which could explain the link between severe COVID-19 infection and worsening of AD control/severity.42 Hence, COVID-19 infection does not appear to result in worsening AD control/severity in most patients, except those with severe infection.

Nordhorn et al43 reported that at least 18% of physicians closed their practices for at least a week during the pandemic for reasons such as patient absence and lack of ability to comply with hygiene regulations. As a result, 8.6% of dermatologists reported impaired treatment of moderate to severe AD. Isoletta et al44 observed an increased complexity of cases, as evidenced by the increased need for biopsies and systemic therapy in AD patients presenting to the ED after a lockdown period compared to the prepandemic era, suggesting that delayed access for noncritical conditions like AD may have resulted in more advanced disease by the time of presentation.

Self-imposed or involuntary treatment disruption was another major indirect factor influencing disease severity. Twelve studies19,45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 reported treatment disruptions in AD patients, the majority of which evaluated disruptions in dupilumab therapy. Across several studies,19,45,47,51,54,55 the proportion of AD patients experiencing self-imposed or unanticipated treatment disruptions (of immunosuppressive and biologic treatments) was between approximately 7.4% to 14.5%. A common reason among those who chose to discontinue drug therapy was a perceived heightened risk of acquiring COVID-19 infection while receiving dupilumab.19,48,52,54 Regardless, most AD patients receiving dupilumab were comfortable continuing treatment during the pandemic.45,46

Two studies56,57 evaluating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on FA disease control and severity outcomes were identified. Musallam et al56 found that children with multiple FAs had significantly more FA reactions than children with a single FA during the pandemic. A separate study found a nonsignificant increase in the proportion of FA patients administering epinephrine autoinjectors during the pandemic.57 This study had a small sample size, which might explain the nonsignificant findings. We postulate that a disruption of supply chains during the pandemic may have led to reduced availability of specialized foods, in turn leading to increased allergen exposure and FA reactions.

From the perspective of health care professionals, Alvaro-Lozano et al58 found that around a quarter of OFCs were canceled and that a large majority experienced disruptions in their clinical practice. Nonetheless, around 27% of providers still initiated food OIT, and 20% continued updosing without modifications. Anagnostou et al59 described that infection control measures, space availability, and patient and staff scheduling were the main barriers to peanut OIT during the pandemic. However, as a result of pandemic-related school closures and work-from-home initiatives, patients experienced more flexibility in scheduling appointments. Nachshon et al60 also found that OIT updosing tended to be performed in older patients and began with a lower single highest tolerated dose than conventional protocols.

ED visits, hospitalizations, and clinic presentations

Three studies described AD associated ED visits/hospitalizations: there were reduced hospitalizations in Poland61 and Turkey,62 but no changes in Italy.44 The data in Italy also showed an increase in the proportion of patients initiating medications before seeking care at the ED, potentially in a bid to delay noncritical care. While there was also an increased proportion of admissions for dermatitis and eczema in Turkey during the pandemic, the total overall number of admissions decreased. Likewise, there was a non–statistically significant decrease in the number of patients admitted for AD specifically in Turkey. We postulate that the observations in Poland, Turkey, and Italy may be attributed to a general fear of being infected in the hospital environment and of violating lockdown restrictions, leading to overall fewer AD admissions. A causal relationship is well established between emotional stress, stressful life events, and the course of many skin diseases, including dermatitis and eczema.63 Alongside lifestyle changes, these factors may have also contributed to the increased proportion of dermatitis and eczema admissions in Turkey.

Eight other studies reported changes in AD clinic attendance rates during the COVID-19 pandemic: 1 demonstrated a decrease,64 3 reported no change,62,65,66 and the remaining 4 studies10,67, 68, 69 found increased rates of clinic presentations in specific age groups. Among the pediatric and adolescent populations, the number of medical visits for AD did not change significantly during the pandemic.69 These studies had small sample sizes and were conducted at single institutions, so local regulations may have influenced observations. For instance, 4 studies were carried out in Turkey,62,64, 65, 66 1 of which observed reduced clinic attendances,64 yet no changes were observed in the other 3 studies.62,65,66 In this country, following the report of the first COVID-19 case in the country, all schools were closed, stay-at-home directives were issued for entire weekends, public holidays were canceled, and intercity travel was restricted. A curfew was applied for people under age 20 and above age 65, and sometimes for everyone during certain periods. The curfew presented a barrier for patients’ attending their medical follow-up appointments, particularly for non–life-threatening diseases. Furthermore, only city hospitals were dedicated to COVID-19 cases, while university hospitals and outpatient clinics were considered nonpandemic facilities.64 The latter were not required to close services to prioritize COVID-19 patients and hence did not see a significant drop in AD/FA clinic services. Additionally, in Korea, the increase in AD clinic presentations in a military hospital coincided with a ban on medical leave put in place as a result of a COVID-19 outbreak within the military.68

Two studies70,71 reported that FA-related ED visits and hospitalizations declined during the pandemic. This finding is in line with an overall reduction in all causes of ED pediatric hospitalizations in the same period.71 Attanasi et al,72 however, reported an increase in the number of children presenting with food anaphylaxis, which was attributed to the difficulties in finding specialist allergy products like adrenaline autoinjectors or hydrolyzed formulas as a result of increased time spent at home, income disruptions related to the pandemic, high product demand, and supply chain disruptions.

Eight studies56,58,60,73, 74, 75, 76, 77 reported the impact of the pandemic on FA-related clinic presentations from the patient perspective. Most reported difficulties accessing FA-related health services, and significantly fewer children utilized any medical service at all.74 Only a single center in the United States reported an increase in both telehealth and in-clinic visits during the pandemic; however, no information about the facilities was offered, or reasons for the increased uptake.77 There was also a reduced adherence to scheduled appointments and diagnostic OFCs. Substantially fewer caregivers sought medical attention after a food-induced allergic reaction.56 Health care adaptations, such as a nurse-led home food allergen introduction service in patients with a history of allergic symptoms, were generally safe and effective, but many patients preferred to wait for a formal hospital OFC78, 79, 80 to guide allergen introduction, citing their preference for direct health care access and more in-person support.

Telehealth and alternative health care initiatives

AD was cited as one of the most common suitable dermatologic conditions eligible for telemedicine81, 82, 83 in view of its noncritical nature, feasibility of diagnosis by using classic features visible over video streaming without an in-person physical examination, and ability to prescribe therapy remotely. Better attendance rates were recorded for telemedicine encounters compared to in-person visits, which enabled continued access to AD services.84,85 Two studies86,87 reported good effectiveness of telemedicine in AD follow-up care, preventing delay in treatment of disease flares or worsening of symptoms due to therapeutic interruption. Teledermatology was also not associated with inappropriate dispensing of antibiotic prescriptions.88

From certain AD patients’ perspective, however, telemedicine was viewed as less satisfactory than face-to-face consultations.26,32,47,89 The dissatisfaction was more marked in patients with moderate to severe AD, where close to 50% were discontented with a telemedicine approach47 as a result of the lack of a physical examination, and thus a perceived inadequate assessment of their skin condition and the inability of doctors to fully advise them on appropriate and timely therapeutic options, which could have influenced their preference for face-to-face appointments over telemedicine.90 Reported benefits of telemedicine among other satisfied patients were cost savings as well as time efficiency resulting from reduced traveling requirements.32,81

Telehealth was also a safe and efficacious medium for FA management, with generally high patient satisfaction.91, 92, 93, 94, 95 Mac Mahon et al86 and Schoonover et al96 reported successful baked egg introduction and modified OIT updosing regimens, respectively, in FA patients during the pandemic, which helped mitigate disruptions in timely FA treatment. However, 1 study97 reported a lack of satisfaction among health care practitioners, who stipulated that telemedicine was only useful for patients with known severe conditions who required urgent review and was not useful for diagnostic consultations. In particular, allergists’ satisfaction was lowest for virtual OFCs and OITs, if performed.91 Only 13.7% of health care practitioners in Turkey reported continuation of oral challenge and skin or blood testing for FA diagnosis, with allergists preferring telemedicine for asthma and rhinitis instead.98 The main disadvantages were limited allergy testing opportunities, lack of physical examination, and unsuitability of the modality to severe conditions.84,91,92,97,99,100

Apart from telemedicine, 2 studies described their experience in delivering OFCs to FA patients in adapted settings such as in a nonhospital facility101 and a COVID-19 field hospital,102 while 2 studies described a pediatric home-based food introduction service103 and a group visit model for OFCs.104 These alternative approaches were safe and effective, with no severe complications (ie, cases requiring advanced airway management or intensive care) and reported high patient satisfaction, although the studies had small sample sizes and each evaluated only a single facility. Wait times were also reduced considerably, with mean wait time for all OFCs down by 1.04 months.104

Impact of COVID-19 disease and vaccinations on patients with AD/FA

Impact of AD/FA disease and AD/FA treatments on COVID-19 morbidity

Table II summarizes 28 studies27,97,105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131 with data on COVID-19 infection morbidity in patients with AD and FA. The majority did not find any significant differences compared to healthy individuals. A few studies reported slight decreases or increases in COVID-19–related outcomes. On closer examination of each of these studies, this was likely due to small sample sizes or due to studies that were conducted in a single hospital, which suggests that the results were subjected to region- or location-specific factors that could have influenced COVID-19–related outcomes. Baseline characteristics of each study population were also different, with some comprising high-risk populations (eg, ischemic heart disease, vascular disease, pulmonary disease) or more elderly patients, both of which are known risk factors for worse COVID-19 outcomes.132

Table II.

Impact of AD and FA on COVID-19–related outcomes

| Study | Country | Disease type | COVID-19 outcome measured | Association | Outcome, OR (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attauabi105 | Denmark | AD | COVID-19 PCR positivity | Decrease | — |

| Beken106 | Turkey | AD, food allergen sensitization | COVID-19 hospitalization, COVID-19 severity | No association |

AD and COVID-19 severity 0.477 (0.034-6.586) |

| Bowe107 | United States | AD | COVID-19 reinfection | No association |

Risk of AD in those with reinfection vs no reinfection HR, 1.06 (0.91-1.24) |

| Carmona-Pirez108 | Spain | AD with anxiety disorders | COVID-19 infection | Increase |

aOR 1.36 (1.06-1.74) |

| Carugno109 | Italy | AD with dupilumab | COVID-19 infection | No association | — |

| Criado27 | Brazil | AD and antihistamines, oral corticosteroids, dupilumab | COVID-19 severity/duration | No association | AD and antihistamines: 0.7 (0.3-1.6) AD and oral corticosteroids: 0.3 (0.1-2.3) AD and antihistamines: 3.6 (0.8-17.6) |

| Fan110 | United States | AD | COVID-19 infection | Increase | aOR: 1.29 (1.15-1.44) |

| Fritsche111 | United States | FA | Postacute sequelae of COVID-19 | Increase | 1.94 (1.42-2.60) |

| Keswani112 | United States | AD, FA | COVID-19 hospitalization, ICU admission, intubation | No association |

AD Hospitalization: 0.51 (0.25-0.90) ICU admission: 0.65 (0.22-1.55) Intubation: 0.18 (0.01-0.87) FA Hospitalization: 0.97 (0.57-1.62) ICU admission: 0.97 (0.41-2.01) Intubation: 0.1 (0.21-1.83) |

| Kridin113 | Israel | AD and dupilumab | COVID-19 infection, hospitalization | No association |

HR COVID-19 infection Dupilumab vs systemic corticosteroids: 1.13 (0.61-2.09) Dupilumab vs phototherapy: 0.80 (0.42-1.53) Dupilumab vs azathioprine: 1.10 (0.45-2.65) Hospitalization Dupilumab vs systemic corticosteroids: 0.35 (0.05-2.71) Dupilumab vs phototherapy: 0.43 (0.05-3.98) Dupilumab vs azathioprine: 0.25 (0.02-2.74) |

| Kridin114 | Israel | AD | COVID-19 hospitalization | No association | Extended courses of systemic corticosteroids required in COVID-19–related hospitalization: 1.96 (1.23-3.14) |

| Kutlu115 | Turkey | AD | COVID-19 severity | No association | — |

| Marsteller116 | United States | Food allergen sensitization | COVID-19 positivity | No association | — |

| Miodonska117 | Poland | AD severity | Severe COVID-19 | No association |

HR 0.45 (0.32-0.65) |

| Musters97 | Global | AD and dupilumab, corticosteroids, topical treatments | COVID-19 hospitalization | AD and dupilumab: Decrease AD and systemic corticosteroids: Increase |

Hospitalization (aOR) Topical treatments vs dupilumab: 4.99 (1.4-20.84) Systemic corticosteroids vs dupilumab: 2.85 (0.08-38.11) Cyclosporin vs dupilumab: 3.02 (0.14-25.72) Combination therapy including systemic corticosteroids vs nonsteroidal immunosuppressive monotherapy: 45.74 (4.54-616.22) Combination therapy not including systemic corticosteroids vs nonsteroidal immunosuppressive monotherapy: 37.57 (1.05-871.11) Systemic corticosteroid monotherapy vs nonsteroidal immunosuppressive monotherapy: 1.87 (0.03-55.4) |

| Nguyen118 | United States | AD, including patients receiving immunomodulatory medications (prednisolone, methotrexate, ciclosporin, dupilumab) | COVID-19 infection, hospitalization and mortality rate | No association | — |

| Pakhchanian119 | Global | AD, including those receiving systemic immunosuppressants | Hospitalization, mortality, severe COVID-19 | No association | Hospitalization: 0.89 (0.75-1.04) Mortality: 1.02 (0.62-1.62) Severe COVID-19: 0.8 (0.54-1.19) |

| Patrick120 | United States | AD | COVID-19 infection | Increase | 1.48 (1.06-2.06) |

| Raiker121 | Global | AD | COVID-19 hospitalization, critical care admission, severe COVID-19 | Hospitalization: Decrease Others: No association |

Adjusted risk ratio Hospitalization: 0.63 (0.54-0.72) |

| Rakita122 | United States | AD | COVID-19 severity, complications, hospitalization | Hospitalization: aOR 0.51 (0.20-1.35) Acute level of care at initial medical care: 0.67 (0.35-1.30) Severe to critical SARS-CoV-2: 0.82 (0.29-2.30) Requirement of supplemental nonmechanical oxygen therapy: 1.33 (0.50-3.58) Extended hospital stay: 2.24 (0.36-13.85) Lingering COVID-19 symptoms: 0.58 (0.06-5.31) COVID-19 death (0.002 (<0.001 to >999) |

|

| Seibold123 | United States | AD/FA | COVID-19 infection, household transmission |

COVID-19 infection AD: No association FA: Decrease Household transmission AD: No association FA: Decrease |

HR AD: VID infection: 1.06 (0.75-1.50) FA: COVID-19 infection: 0.50 (0.32-0.81) aOR AD: Household transmission: 1.85 (0.65-5.21) FA: Household transmission: 0.43 (0.19-0.96) |

| Smith-Norowitz124 | United States | AD | COVID-19 positivity (IgM, IgG, Ag) | No association | — |

| Ungar125,126 | United States | AD and dupilumab | COVID-19 severity, COVID-19 antibody levels | Dupilumab compared to nonbiologic systemic treatments, other systemic treatments, and limited/no treatments: Decrease | Systemic treatments vs dupilumab: 3.89 Limited/no treatments vs dupilumab: 1.96 Nonbiologic systemic treatment vs dupilumab: 1.87 |

| Wu127 | Denmark | AD and AD treated with dupilumab | COVID-19 infection | AD: Slight increase AD and dupilumab: Decrease |

Incidence rate ratio AD: 1.18 (1.12-1.24) AD and dupilumab: 0.66 (0.52-0.83) |

| Yang128 | South Korea | AD | COVID-19 PCR positivity, severe COVID-19 outcomes (ICU admission, invasive ventilation, death) | No association | COVID-19 positivity: 0.93 (0.76-1.13) Severe COVID-19 outcomes: 0.72 (0.18-2.90) |

| Yiu129 | United Kingdom | AD | COVID-19 PCR positivity | No association |

aOR 0.60 (0.22-1.64) |

| Yue130 | United States | AD | COVID-19 Severity | Decrease |

Adjusted risk ratio Severe COVID-19 in AD vs non-AD: 0.8 (0.7-0.9) |

| Zhang131 | Netherlands | AD | COVID-19 infection | No association | Mild AD: 1.11 (0.71-1.73) Moderate to severe AD: 1.00 (0.74-1.36) |

aOR, Adjusted OR; HR, hazard ratio; ICU, intensive care unit; OR, odds ratio; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Dupilumab and tralokinumab are monoclonal biologics commonly used for treatment of severe AD. Studies on the safety of dupilumab on COVID-19 risk have collectively concluded that dupilumab is safe and does not increase the risk of COVID-19–related morbidities.22,24,53,132, 133, 134, 135 Similarly, Blauvelt et al136 demonstrated that COVID-19 infections were predominantly mild or moderate in AD patients who continued receiving tralokinumab therapy during COVID-19 infection. A plausible reason for this might be dupilumab’s specific antagonism of the IL-13 and IL-4 pathway (TH2 targeting) and tralokinumab’s targeting of the IL-13 pathway, which does not impede mainly TH1 pathways involved in immune protection against COVID-19.

Furthermore, dupilumab therapy appeared to be associated with a slightly decreased risk of COVID-19 infection and severity. One study132 found a lowered incidence of COVID-19 among patients with AD receiving dupilumab treatment compared to the general Canadian population. At present, the available literature supports the continuation of dupilumab in AD patients during the pandemic.

COVID-19 vaccination outcomes in AD/FA patients

We identified 13 studies reporting adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccination specifically in AD patients (see Table E8 in the Online Repository available at www.jaci-global.org).137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149 Most enrolled patients received the Pfizer (BNT162b2) vaccine (71-100%), followed by the 14% to 15% who received the Moderna (Spikevax/mRNA-1273) vaccine,138,140,142, 143, 144,147 and a minority received the Johnson & Johnson (Janssen) vaccine.137,150 Overall, these studies reported no significant differences in postvaccination adverse effects in AD patients compared to healthy patients,137,138,141,142 including pediatric AD patients147 and AD patients treated with tralokinumab.139 This was also similar at 30, 60, and 90 days after vaccination,143 and there were also no differences in the rates of breakthrough COVID-19 infection. The vaccine was found to be effective in reducing the risk of hospitalization and COVID-19–related mortality in AD patients; it was also found that immunosuppressive drugs (azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, cyclosporine, dupilumab) did not impair vaccine effectiveness.151

Several small studies reported increases in AD-related risk after COVID-19 vaccination. In 1 study,140 AD patients who received the Moderna vaccine did not experience higher risks of typical immunization stress–related responses but appeared to have an increased risk of immediate hypersensitivity reactions. This study, however, had a very small number of AD patients and wide confidence intervals, which reduces the certainty of evidence.

AD patients prescribed corticosteroids or anti-inflammatory therapy within a year of being vaccinated showed minimal risk of adverse outcomes, although they were initially found to be at higher risk of all-cause hospitalization before propensity-matching adjusting for demographic and comorbidities.137 Potestio et al144 similarly found that only a small percentage (2.7%) of AD patients receiving dupilumab developed AD exacerbations after vaccination, all of which were successfully treated with topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors. This further supports the safety of COVID-19 vaccination in AD patients who are undergoing treatment with dupilumab. Kridin et al151 reported an increased vaccination uptake in those with adult-onset AD or moderate to severe AD, although this may be attributed to prioritization of vaccination for those receiving immunosuppressive drugs. Among those who tested positive for COVID-19, vaccinated people were more likely than unvaccinated people to self-report an eczema diagnosis.148 However, no difference in cutaneous symptoms of COVID-19 infection was found between the 2 groups.

Findings were more variable in patients with FA (see Table E9 in the Online Repository available at www.jaci-global.org).142,146,150,152, 153, 154 Shukla et al153 reported no serious adverse effects in FA patients receiving the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine/Covishield (85% vaccinated) and the whole inactivated virus–based vaccine Covaxin (BBV152) (12% vaccinated). A single conference abstract150 reported an association between seafood allergy and anaphylaxis risk for Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson vaccines using data from the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System early in the pandemic (January 2020 to December 2021). In FA patients receiving the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, Chiewchalermsri et al152 found no difference in adverse effects between FA and non-FA groups in the first 6 hours after vaccination. However, there was a statistically significant increased risk of fever, nausea, vomiting, skin rash, and local reaction in the FA group from 24 hours to 7 days after the vaccination. Although reasons for such observations are unclear, a limitation of the study was documentation of adverse reactions via telephone, which may result in inaccuracies when identifying and differentiating adverse skin reactions. There were no data on vaccination efficacy or morbidity in FA patients specifically.

Mental health, psychological impact, and QoL

Eight studies23,25,26,29,30,47,131,155 evaluated the psychological impact of the pandemic on AD patients. AD patients typically reported concerns in 2 key areas: generic pandemic-related concerns and AD-specific concerns. Generic pandemic-related concerns included loss of income, fear of COVID-19 infection, and fear of adverse effects after COVID-19 vaccination. Lugovic-Mihic et al155 found that 59% of AD patients experienced psychological distress during the pandemic caused by generic COVID-19–related concerns. Loss of employment was also found to be associated with worsening mental health in AD patients, while stable or improved mental health outcomes were associated with working from home.23 Interestingly, while there was a higher level of generic anxiety, depression, and stress25,30,47 during the pandemic, this effect was found to be more pronounced in patients with moderate to severe AD compared to those with mild AD.29 Moreover, AD patients tended to be more concerned about the COVID-19 crisis compared to non-AD patients and were more likely to avoid contacting a doctor when experiencing health problems,131 plausibly because of their reluctance in burdening the health care system for a non–life-threatening condition.

AD-specific concerns included a perception of being more vulnerable to COVID-19 infection and an inability to procure AD medications. Patients with moderate to severe AD were found to be more stressed about medication shortages and perceived an increased vulnerability to COVID-19; they were also more afraid of COVID-19 vaccination’s adverse effects.131 A similar impact was also reported in caregivers of AD patients and children with AD, where 75% and 50% experienced COVID-19–related stressors, respectively. More than 33% of caregivers also believed their child to be more vulnerable to COVID-19 infection.26 Overall, the increased uncertainty, lack of clear information, and disruptions to routine health care were likely reasons for these adverse mental health impacts.

The studies that investigated QoL outcomes in AD patients primarily used health-related QoL (HRQoL) or Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) measures. Overall, all studies reported worsening of HRQoL and DLQI scores in AD patients during the pandemic,20,31,39,156 commonly because of loss of employment and income as well as COVID-19–related concerns. Adults with higher DLQI experienced a lower burden due to COVID-19 compared to those who were less affected by their disease.40 Only weak associations were observed between increasing burden and reduction in QoL. There were also increased HRQoL-reported pain and discomfort in AD patients.20,31 Adolescents reported experiencing higher stress levels, which could have also triggered their eczema flares.32 Although preexisting mental health conditions, specifically depression and/or anxiety, were not specifically addressed in the abovementioned study, this lends support to the bidirectional association between mental health and physical health/AD disease control: AD patients with poorer mental health states may be at higher risk of flares and poorer disease control.

There were also similar increases in levels of pandemic-related anxiety and stress levels in caregivers,157, 158, 159, 160 adults,161 and children with FA.162 However, several studies suggested that while overall anxiety increased, FA-specific anxiety remained unchanged or even reduced in most patients and caregivers during the pandemic.157,159 This was largely attributed to perceived increased control over exposures and diet resulting from movement restrictions and extended home confinement, resulting in reduced risk of accidental exposure. Santos et al163 also found that elementary school teachers in Canada felt better empowered to manage and supervise FA during mealtimes thanks to new practices such as fixed seating arrangements, restrictions on outside food, and improved cleaning practices.

However, specific subgroups, such as FA patients with a history of FA-related emergency visits, tended to report more FA-related anxiety resulting from concerns around the pandemic’s burdens and disruptions to the medical care system.159 In addition, Warren et al161,164 reported an increase in the level of FA-related anxiety/stress resulting from difficulties obtaining safe, nutritious foods, accidental allergen exposure, and perceived inability to identify and treat FA anaphylaxis, as well as accessing health care for anaphylaxis episodes. This effect was greater in younger and female adults, and from households living below the poverty line. Intolerance of uncertainty and lack of food-related self-efficacy thus also contributed to a lower QoL.165

There were also negative psychological outcomes related to FA treatment disruptions. Maeta et al76 found that parents who faced disruptions in the progress of their child’s home-based food OIT also experienced significant anxiety about ED visits and risk of COVID-19. These children tended to have been prescribed adrenaline before or had severe or multiple food allergies and were at high risk of requiring emergency care, resulting in enhanced anxiety around access to medical care. In contrast, these concerns were not significant for lower-risk FA patients and caregivers undergoing OIT. Leef et al75 reported only a minority of patients (8.5%) cited the pandemic as a major barrier to commencing OIT. ED access during the pandemic was also not a major deterrent to the introduction of baked egg in egg-allergic patients in a home setting.86

Similar to AD, FA patients who had increased levels of anxiety and depression were found to have a poorer QoL.160 However, there was insufficient information as to whether these were related to preexisting mental health issues or as a result of the pandemic. Additionally, a trend toward worse QoL, particularly in the domains of family life, future security, and personal relationships, was observed in children whose caregivers reported negative pandemic-related impacts on their children’s behalf.73

Increased food spending, attributed to a lack of availability of specialized foods and disruption of supply chains, also led to increased food insecurity among FA families.166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171 This effect was more pronounced in families with dietary restrictions compared to those without restrictions.168 Twelve percent of food-allergic families reported buying foods with “may contain” precautionary allergen labeling, although they would have avoided such purchases before the pandemic.172 However, despite these QoL changes, Ahad et al169 reported that most families did not think that the risk of an allergic reaction was higher compared to the prepandemic period because of their increased dietary control and confidence with allergy management. Zhang et al173 also found that 11.2% indicated that the pandemic was a reason to avoid takeout food, and although there were no changes to takeout practices in FA individuals before and after the pandemic overall, severe allergic reactions occurred mostly in response to Mexican, Chinese, or Asian cuisine.

Conclusion

This systematic review provides a comprehensive overview of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with AD and FA. Most studies reported no significant changes in overall incidence or prevalence of AD during the pandemic, but some studies noted an increase in specific subgroups. AD disease morbidity increased mainly in patients who had discontinued essential therapy such as dupilumab; were exposed to triggers that exacerbated the underlying disease, such as personal protective equipment in AD; or experienced severe COVID-19 infection. Delayed health-seeking behavior resulting in more severe AD presentations after lockdown was also notable, and the QoL studies we found suggested key reasons included reluctance to visit health care establishments or to burden hospitals facing overwhelming COVID-19 care needs.

There were clear variations in ED and clinic attendances reported between centers resulting from local or institution-specific COVID-19 response factors. Disruptions to health care access and treatment regimens were experienced almost universally, but the impact appeared to be worse in high-risk patients with severe or brittle disease, namely severe AD; multiple FA or severe FA with low reactive thresholds; FA requiring supply-chain–dependent therapeutics (adrenaline autoinjectors and specialized formulas); and those with preexisting mental health concerns. The negative psychological impact of the pandemic on AD and FA patients was closely tied to these factors.

Vaccines and biologics for COVID-19 can be safely administered to patients with atopic diseases. Nevertheless, it is essential to emphasize efforts to educate patients so that at-risk individuals continue to receive essential therapies during times of crisis.

A central theme across the studies was how telemedicine played a large role in mitigating the impact of health care disruptions on atopic disease management. This technology is particularly suitable for AD and FA, as these are diseases where diagnosis can be made visually (AD) or where physical examination is not required (FA). Many centers globally have since retained telemedicine as a prominent feature of their services even in the postpandemic era—a sure sign that future health care will include a hybrid model with both virtual and in-person care. Innovative practices like the provision of OFCs in non–health care settings and home-based care are also key examples of the importance of embracing agility in medicine to maintain resilience and business continuity.

Disclosure statement

E.H.T. is supported by a National Medical Research Council (NMRC) Transition Award grant (MOH-TA18nov-003), Singapore.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank our librarian, Annelissa Chin Mien Chew, for assistance with the literature search.

Footnotes

The first 2 authors contributed equally to this article, and both should be considered first author.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Shaker M.S., Oppenheimer J., Grayson M., Stukus D., Hartog N., Hsieh E.W.Y., et al. COVID-19: pandemic contingency planning for the allergy and immunology clinic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:1477–1488.e1475. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moynihan R., Sanders S., Michaleff Z.A., Scott A.M., Clark J., To E.J., et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilisation of healthcare services: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Izquierdo J.L., Almonacid C., González Y., Del Rio-Bermudez C., Ancochea J., Cárdenas R., et al. The impact of COVID-19 on patients with asthma. Eur Respir J. 2021;57:2003142. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03142-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jia Y., Bao J., Yi M., Zhang Z., Wang J., Wang H., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on asthma control among children: a qualitative study from caregivers’ perspectives and experiences. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Z., Wang X., Wan X.G., Wang M.L., Qiu Z.H., Chen J.L., et al. Pediatric asthma control during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2022;57:20–25. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Izquierdo-Domínguez A., Rojas-Lechuga M.J., Alobid I. Management of allergic diseases during COVID-19 outbreak. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2021;21:8. doi: 10.1007/s11882-021-00989-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Covidence systematic review software. Veritas Health Innovation; Melbourne (Australia): 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hong Q.N., Fàbregues S., Bartlett G., Boardman F., Cargo M., Dagenais P., et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inform. 2018;34:285–291. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandeng Ma Linwa E., Sigha O.B., Djeumen Touka A.J., Eposse Ekoube C., Ngo Linwa E.E., Budzi M.N., et al. Trends in dermatology consultations in the COVID-19 era in Cameroon. Skin Health Dis. 2022;2:e113. doi: 10.1002/ski2.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi H.G., Kong I.G. Asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis incidence in Korean adolescents before and after COVID-19. J Clin Med. 2021;10:3446. doi: 10.3390/jcm10153446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee K.H., Yon D.K., Suh D.I. Prevalence of allergic diseases among Korean adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: comparison with pre–COVID-19 11-year trends. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26:2556–2568. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202204_28492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi H.G., Kim S.Y., Joo Y.H., Cho H.J., Kim S.W., Jeon Y.J. Incidence of asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis in Korean adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic using data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:14274. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192114274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tefft K.R., Balboul S., Safai B., Cline A., Marmon S. Diagnosis of stress-associated dermatologic conditions in New York City safety-net hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:e177–e179. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2022.05.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanthavichai S., Laopakorn J. Prevalence and associated factors of skin diseases among geriatric outpatients from a metropolitan dermatologic clinic in Thailand. Dermatol Sinica. 2022;40:168–173. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurley S., Franklin R., McCallion N., Byrne A.M., Fitzsimons J., Byrne S., et al. Allergy-related outcomes at 12 months in the CORAL birth cohort of Irish children born during the first COVID-19 lockdown. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2022;33:e13766. doi: 10.1111/pai.13766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byrne A., Kelleher M.M., Hourihane J.O. BSACI 2021 guideline for the management of egg allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2022;52:585. doi: 10.1111/cea.14061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan Ng P.P.L., Kang A.Y.H., Shen L., Wong L.S.Y., Tham E.H. Improved treatment adherence and allergic disease control during a COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2022;33 doi: 10.1111/pai.13688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiricozzi A., Talamonti M., De Simone C., Galluzzo M., Gori N., Fabbrocini G., et al. Management of patients with atopic dermatitis undergoing systemic therapy during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: data from the DA-COVID-19 registry. Allergy. 2021;76:1813–1824. doi: 10.1111/all.14767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koszorú K., Hajdu K., Brodszky V., Szabó Á., Borza J., Bodai K., et al. General and skin-specific health-related quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitis before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatitis. 2022;33:S92–S103. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De la O-Escamilla N.O., Garcia-Lira J.R., Valencia-Herrera A.M. Follow-up of patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis by teledermatology during COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38:1428. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grieco T., Chello C., Sernicola A., Muharremi R., Michelini S., Paolino G., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on patients with atopic dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:1083–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rovati C., Rossi M., Gelmetti A., Tomasi C., Calzavara-Pinton I., Venturini M., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on the clinical response to dupilumab treatment and the psychological status of non-infected atopic patients. Eur J Dermatol. 2021;31:736–740. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2021.4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Napolitano M., Patruno C., Ruggiero A., Nocerino M., Fabbrocini G. Safety of dupilumab in atopic patients during COVID-19 outbreak. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:600–601. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1771257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanessa M., Elia E., Federica V., Edoardo C., Chiara A., Francesca G., et al. Facial dermatoses and use of protective mask during COVID-19 pandemic: a clinical and psychological evaluation in patients affected by moderate–severe atopic dermatitis under treatment with dupilumab. Dermatolog Ther. 2022;35 doi: 10.1111/dth.15573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ragamin A., de Wijs L.E.M., Hijnen D.J., Arends N.J.T., Schuttelaar M.L.A., Pasmans S.G.M.A., et al. Care for children with atopic dermatitis in the Netherlands during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from the first wave and implications for the future. J Dermatol. 2021;48:1863–1870. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Criado P.R., Ianhez M., Silva de Castro C.C., Talhari C., Ramos P.M., Miot H.A. COVID-19 and skin diseases: results from a survey of 843 patients with atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, vitiligo and chronic urticaria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:e1–e3. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lugovic-Mihic L., Mestrovic-Stefekov J., Cvitanovic H., Bulat V., Duvancic T., Pondeljak N., et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and recent earthquake in Zagreb together significantly increased the disease severity of patients with atopic dermatitis. Dermatology. 2023;239:91–98. doi: 10.1159/000525901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pourani M.R., Ganji R., Dashti T., Dadkhahfar S., Gheisari M., Abdollahimajd F., et al. [Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with atopic dermatitis] Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113:T286–T293. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2021.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernández N., Sanclemente G., Tamayo L., López Á., Seidel A., Hernandez N., et al. Atopic dermatitis in the COVID-19 era: results from a web-based survey. World Allergy Org J. 2021;14:100571. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2021.100571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chernyshov P.V., Vozianova S.V., Chubar O.V. Quality of life of infants, toddlers and preschoolers with seborrhoeic, allergic contact and atopic dermatitis before and during COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol Ther. 2021;11:2017–2026. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00617-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steele M., Howells L., Santer M., Sivyer K., Lawton S., Roberts A., et al. How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected eczema self-management and help seeking? A qualitative interview study with young people and parents/carers of children with eczema. Skin Health Dis. 2021;1:e59. doi: 10.1002/ski2.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szepietowski J.C., Matusiak Ł., Szepietowska M., Krajewski P.K., Białynicki-Birula R. Face mask–induced itch: a self-questionnaire study of 2,315 responders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:1–5. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cazzaniga S., Pezzolo E., Colombo P., Naldi L. Face mask use in the community and cutaneous reactions to them during the COVID-19 pandemic: results of a national survey in Italy. Dermatol Rep. 2022;14:9394. doi: 10.4081/dr.2022.9394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skiveren J.G., Ryborg M.F., Nilausen B., Bermark S., Philipsen P.A. Adverse skin reactions among health care workers using face personal protective equipment during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey of six hospitals in Denmark. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;86:266–275. doi: 10.1111/cod.14022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westermann C., Zielinski N., Altenburg C., Dulon M., Kleinmuller O., Kersten J.F., et al. Prevalence of adverse skin reactions in nursing staff due to personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:12530. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191912530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malathy P.A., Daniel S.J., Venkatesan S., Priya B.Y. A clinico epidemiological study of adverse cutaneous manifestations on using personal protective equipment among health care workers during covid pandemic in a tertiary care centre. Indian J Dermatol. 2022;67:478. doi: 10.4103/ijd.ijd_1157_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hui-Beckman J., Leung D.Y.M., Goleva E. Hand hygiene impact on the skin barrier in health care workers and individuals with atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;128:108–110. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2021.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Damiani G., Finelli R., Kridin K., Pacifico A., Bragazzi N.L., Malagoli P., et al. Facial atopic dermatitis may be exacerbated by masks: insights from a multicenter, teledermatology, prospective study during COVID-19 pandemic. Ital J Dermatol Venerol. 2022;157:505–509. doi: 10.23736/S2784-8671.22.07386-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Helmert C., Siegels D., Haufe E., Abraham S., Heratizadeh A., Kleinheinz A., et al. Perception of the coronavirus pandemic by patients with atopic dermatitis—results from the TREATgermany registry. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2022;20:45–57. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donlan A.N., Sutherland T.E., Marie C., Preissner S., Bradley B.T., Carpenter R.M., et al. IL-13 is a driver of COVID-19 severity. JCI Insight. 2021;6 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.150107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weidinger S., Willis-Owen S.A., Kamatani Y., Baurecht H., Morar N., Liang L., et al. A genome-wide association study of atopic dermatitis identifies loci with overlapping effects on asthma and psoriasis. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4841–4856. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nordhorn I., Weiss D., Werfel T., Zink A., Schielein M.C., Traidl S. The impact of the first COVID-19 wave on office-based dermatological care in Germany: a focus on diagnosis, therapy and prescription of biologics. Eur J Dermatol. 2022;32:195–206. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2022.4222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Isoletta E., Vassallo C., Brazzelli V., Giorgini C., Tomasini C.F., Sabena A., et al. Emergency accesses in dermatology department during the COVID-19 pandemic in a referral third level center in the north of Italy. Dermatolog Ther. 2020;33 doi: 10.1111/dth.14027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rakita U., Guraya A., Porter C.L., Feldman S.R. Atopic dermatitis patient perspectives on dupilumab therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international survey study. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27:11. doi: 10.5070/D3271156095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Georgakopoulos J.R., Yeung J. Patient-driven discontinuation of dupilumab during the COVID-19 pandemic in two academic hospital clinics at the University of Toronto. J Cutan Med Surg. 2020;24:422–423. doi: 10.1177/1203475420930223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sieniawska J., Lesiak A., Ciążyński K., Narbutt J., Ciążyńska M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on atopic dermatitis patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:1734. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tilotta G., Pistone G., Caruso P., Gurreri R., Castelli E., Curiale S., et al. Adherence to biological therapy in dermatological patients during the COVID-19 pandemic in Western Sicily. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:248–249. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bergman M., Saffore C.D., Kim K.J., Patel P.A., Garg V., Xuan S., et al. Healthcare resource use in patients with immune-mediated conditions treated with targeted immunomodulators during COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective claims analysis. Adv Ther. 2021;38:5302–5316. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01906-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen S.R., Kahn J.S., Gao D.X., Fiumara K., Lam A., Dumont N., et al. Continuation and discontinuation rates of biologics in dermatology patients during COVID-19 pandemic. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:646–647. doi: 10.1177/12034754211024125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kado S., Kamiya K., Kishimoto M., Maekawa T., Kuwahara A., Sugai J., et al. Single-center survey of biologic use for inflammatory skin diseases during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. J Dermatol. 2021;48:1907–1912. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salman A., Apti Sengun Ö., Aktas M., Taşkapan O. Real-life effectiveness and safety of dupilumab in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Dermatolog Ther. 2022;35 doi: 10.1111/dth.15192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Su Küçük Ö., Güneş B., Taşlidere N., Işik B.G., Akaslan T.Ç., Özgen F.P., et al. Evaluation of adult patients with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab: a single-center real-life experience. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:4781–4787. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chiricozzi A., Di Nardo L., Talamonti M., Galluzzo M., De Simone C., Fabbrocini G., et al. Patients withdrawing dupilumab monotherapy for COVID-19–related reasons showed similar disease course compared with patients continuing dupilumab therapy. Dermatitis. 2022;33:e25–e29. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rossi M., Rovati C., Arisi M., Soglia S., Calzavara-Pinton P. Management of adult patients with severe atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab during COVID-19 pandemic: a single-center real-life experience. Dermatolog Ther. 2020;33 doi: 10.1111/dth.13765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Musallam N., Dalal I., Almog M., Epov L., Romem A., Bamberger E., et al. Food allergic reactions during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in Israeli children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021;32:1580–1584. doi: 10.1111/pai.13540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soller L., Cameron S.B., Chan E.S. Exploring epinephrine use by food-allergic families during COVID-19 pandemic in British Columbia. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2021;17(Suppl 1) 21. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alvaro-Lozano M., Sandoval-Ruballos M., Giovannini M., Jensen-Jarolim E., Sahiner U., Tomic Spiric V., et al. Allergic patients during the COVID-19 pandemic—clinical practical considerations: an European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology survey. Clin Transl Allergy. 2022;12 doi: 10.1002/clt2.12097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anagnostou A., Lawrence C., Tilles S.A., Laubach S., Donelson S.M., Yassine M., et al. Qualitative interviews to understand health care providers’ experiences of prescribing licensed peanut oral immunotherapy. BMC Res Notes. 2022;15:273. doi: 10.1186/s13104-022-06161-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nachshon L., Goldberg M.R., Levy M.B., Epstein-Rigbi N., Koren Y., Elizur A. Home epinephrine-treated reactions in food allergy oral immunotherapy: lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 lockdown. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;127:451–455. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2021.05.008. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Białynicki-Birula R., Siemasz I., Otlewska A., Matusiak Ł., Szepietowski J.C. Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on hospitalizations at the tertiary dermatology department in south-west Poland. Dermatolog Ther. 2020;33 doi: 10.1111/dth.13738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goksin S., Imren I.G., Cenk H., Kacar N., Duygulu S. The effects of changing lifestyle and daily behaviours in the first months of COVID-19 outbreak on dermatological diseases: retrospective cross-sectional observational study. Turkiye Klin Dermatol. 2022;32:47–55. doi: 10.5336/dermato.2021-86574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Picardi A., Abeni D. Stressful life events and skin diseases: disentangling evidence from myth. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70:118–136. doi: 10.1159/000056237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gokcek G.E., Solak E.O., Colgecen E., Borlu M. Impact of coronavirus in a dermatology outpatient clinic: a single-center retrospective study. Erciyes Med J. 2022;44:200–207. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Turan Ç., Öner Ü., Metin N. Change in dermatology practice during crisis and normalization periods after the COVID-19 pandemic and potential problems awaiting us. Turkderm Turkish Arch Dermatol Venereol. 2021;55:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Turkmen D., Altunisik N., Mantar I., Durmaz I., Sener S., Colak C. Comparison of patients’ diagnoses in a dermatology outpatient clinic during the COVID-19 pandemic period and pre-pandemic period. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75 doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mangini C.S.M., Vasconcelos R.C.F., Rodriguez E.V.R., Oliveira I.R.L. Social isolation: main dermatosis and the impact of stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2022;20 doi: 10.31744/einstein_journal/2022AO6320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yoon D., Kim K.E., Lee J.E., Kim M., Kim J.H. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on medical use of military hospitals in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36:1–11. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choi H.G., Kim J.H., An Y.H., Park M.W., Wee J.H. Changes in the mean and variance of the numbers of medical visits for allergic diseases before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4266. doi: 10.3390/jcm11154266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Khalil G., Choudhry T., Ozyigit L.P., Williams M., Khan N. Anaphylaxis in emergency department unit: before and during COVID-19. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:160. doi: 10.1111/all.14873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sano K., Nakamura M., Ninomiya H., Kobayashi Y., Miyawaki A. Large decrease in paediatric hospitalisations during the COVID-19 outbreak in Japan. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2021;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-001013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Attanasi M., Porreca A., Papa G.F.S., Di Donato G., Cauzzo C., Patacchiola R., et al. Emergency department visits for allergy-related disorders among children: experience of a single Italian hospital during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2021;16:786. doi: 10.4081/mrm.2021.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen G., DunnGalvin A., Campbell D.E. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life for children and adolescents with food allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2022;52:162–166. doi: 10.1111/cea.13973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Soyak Aytekin E., Tuten Dal S., Unsal H., Akarsu A., Ocak M., Sahiner U.M., et al. Food allergy management has been negatively impacted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asthma Allergy Immunol. 2021;19:71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leef C., Horton C., Lee T., Lee G., Tison K., Vickery B.P. Exploring barriers to commercial peanut oral immunotherapy treatment during COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10:309–311.e301. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maeta A., Takaoka Y., Nakano A., Hiraguchi Y., Hamada M., Takemura Y., et al. Progress of home-based food allergy treatment during the coronavirus disease pandemic in Japan: a cross-sectional multicenter survey. Children. 2021;8:919. doi: 10.3390/children8100919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tovar S., Osheim A., Schultz E. Use of telehealth visits for patients during the COVID-19 pandemic in an allergy/immunology network. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205:A5592. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Noronha L., Leech S., Nicola B. An audit of the home food introduction service developed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:1661–1662. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chua G.T., Chan E.S., Soller L., Cook V.E., Vander Leek T.K., Mak R. Home-based peanut oral immunotherapy for low-risk peanut-allergic preschoolers during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Front Allergy. 2021;2 doi: 10.3389/falgy.2021.725165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chotai R., Leech S., Brathwaite N., Townsend C., Heath S., Ferreira T., et al. Home food introduction service: an initiative for sustaining paediatric allergy services during recovery from COVID-19. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:182–183. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yeroushalmi S., Millan S.H., Nelson K., Sparks A., Friedman A.J. Patient perceptions and satisfaction with teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey-based study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:178–183. doi: 10.36849/JDD.5714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Raiker R., Pakhchanian H., Baker M., Hochman E., Deng M. A multicenter analysis of patients using telemedicine for dermatological conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Invest Dermatol. 2021;141:B14. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gupta M., Bhargava S. The profile of teledermatology consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic: an observational study. Our Derm Online. 2020;11(suppl 2):10–12. doi: 10.7241/ourd.2020S2.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ngo S.Y., Bauer M., Carel K. Telemedicine utilization and incorporation of asynchronous testing in a pediatric allergy clinic during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10:1096–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2022.01.004. e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ufodiama C.E., Touyz S.J.J., Fitzgerald D.A., Hunter H.J.A., McMullen E., Warren R.B., et al. Remote consultations: an audit of the management of dermatology patients on biologics during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:2697. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2037496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mac Mahon J., Hourihane J.O.B., Byrne A. A virtual management approach to infant egg allergy developed in response to pandemic-imposed restrictions. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:360–363. doi: 10.1111/cea.13794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brunasso A.M.G., Massone C. Teledermatologic monitoring for chronic cutaneous autoimmune diseases with smartworking during COVID-19 emergency in a tertiary center in Italy. Dermatolog Ther. 2020;33 doi: 10.1111/dth.13695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fathy R., Briker S., Rodriguez O., Barbieri J.S. Comparing antibiotic prescription rates between in-person and telemedicine visits. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:438–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Al Dhafiri M., Al Haddad S., Al Ameer M., AlHaddad S., Albaqshi H., Kaliyadan F. The burden of parents of children with atopic dermatitis during the pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;39:12–73. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Duan G., Lambert R., Hight R., Rosenblatt A. Comparison of pediatric dermatology conditions across telehealth and in-person visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:1260–1263. doi: 10.36849/JDD.6843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Powell E., Berk O., Smith W., Quincey R., Young L., Clark A., et al. Patient, family and healthcare provider satisfaction with telemedicine in the COVID-19 era. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:1690–1691. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mustafa S.S., Vadamalai K., Ramsey A. Patient satisfaction with in-person, video, and telephone allergy/immunology evaluations during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:1858–1863. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Baaske A.V., Chan E.S., Mak R., Wong T., Hildebrand K.J., Erdle S., et al. Patient satisfaction with a virtual healthcare program for food allergen immunotherapy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2022;17(Suppl 1):27. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chan S.E., Jeimy S., Hanna M., Cook E.V., Mack P.D., Abrams E.M., et al. Caregiver and allergist views on virtual management of food allergy: a mixed methods study. Allergy. 2021;76:331. doi: 10.1111/pai.13539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Latrous M., Zhu R., Jeimy S., Mack D., Soller L., Chan E., et al. Web-based infant food introduction (WIFI): improving access to allergist-supervised infant food introduction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:AB169. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schoonover A., Uyehara A., Goldman M. Continuing peanut oral immunotherapy via telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147:AB109. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Musters A.H., Broderick C., Prieto-Merino D., Chiricozzi A., Damiani G., Peris K., et al. The effects of systemic immunomodulatory treatments on COVID-19 outcomes in patients with atopic dermatitis: results from the global SECURE-AD registry. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37:365–381. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ozturk A.B., Baççloǧlu A., Soyer O., Civelek E., Şekerel B.E., Bavbek S. Change in allergy practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2021;182:49–52. doi: 10.1159/000512079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tsao L.R., Villanueva S.A., Pines D.A., Pham M.N., Choo E.M., Tang M.C., et al. Impact of rapid transition to telemedicine-based delivery on allergy/immunology care during COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:2672–2679. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.04.018. e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chan E.S., Jeimy S., Hanna M., Cook V.E., Mack D.P., Abrams E.M., et al. Caregiver views on virtual management of food allergy: a mixed-methods study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021;32:1568–1572. doi: 10.1111/pai.13539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Walsh N., Sanneerappa P.B., Lewis S., Alsaleemi A., Coghlan D., O’Carroll C., et al. Patient and caregiver satisfaction with novel en masse oral food challenge performance. Allergy. 2021;76:539–540. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Al Saleemi A., Farren L., McCarthy K.F., Hourihane J., Byrne A.M., Trujillo J., et al. Management of anaphylaxis in children undergoing oral food challenges in an adapted COVID-19 field hospital. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106:e52. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2021-322920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kanchanatheera M. Evaluation of the paediatric home based food reintroduction service at Bristol Royal Hospital for Children. In: British Society for Allergy and Immunology (BSACI) Abstracts of the World Allergy Organization (WAO) and BSACI 2022 UK Conference; April 25-27, 2022; Edinburgh International Conference Centre (EICC). Clin Exp Allergy. 2022;52:998–1069. doi: 10.1111/cea.14204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]