Abstract

BACKGROUND

Exercise-based interventions prevent or delay symptoms and complications of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and are highly recommended for T2D patients; though with very low participation rates. Τelerehabilitation (TR) could act as an alternative to overcome the barriers preventing the promotion of T2D patients’ well-being.

AIM

Determine the effects of a six-week TR program on glycemic control, functional capacity, muscle strength, PA, quality of life and body composition in patients with T2D.

DESIGN

A multicenter randomized, single-blind, parallel-group clinical study.

SETTING

Clinical trial.

POPULATION

Patients with T2D.

METHODS

Thirty T2D patients (75% male, 60.1±10.9 years) were randomly allocated to an intervention group (IG) and a control group (CG) with no exercise intervention. IG enrolled in a supervised, individualized exercise program (combination of aerobic and resistance exercises), 3 times/week for 6 weeks at home via a TR platform. Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), six-minute walk test (6MWT), muscle strength (Hand Grip Strength Test [HGS], 30-Second Chair Stand test [30CST] physical activity [IPAQ-SF]), quality of life (SF-36) and anthropometric variables were assessed.

RESULTS

Two-way repeated-ANOVA showed a statistically significant interaction between group, time and test differences (6MWT, muscle strength) (V=0.33, F [2.17]=4.14, P=0.03, partial η2=0.22). Paired samples t-test showed a statistically significant improvement in HbA1c (Z=-2.7), 6MWT (Μean Δ=-36.9±27.2 m, t=-4.5), muscle strength (Μean Δ=-1.5±1.4 kg, t=-2.22). Similarly, SF-36 (mental health [Μean Δ=-13.3±21.3%], general health [Μean Δ=-11.4±16.90%]) were statistically improved only in IG.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings of this study indicate that a 6-week supervised home-based TR exercise program induced significant benefits in patients with T2D, thus enabling telehealth implementation in rehabilitation practice as an alternative approach.

CLINICAL REHABILITATION IMPACT

Home-based exercise via the TR platform is a feasible and effective alternative approach that can help patients with T2D eliminate barriers and increase overall rehabilitation utilization.

Keywords: Key words: Telerehabilitation; Diabetes mellitus, type 2; Walk test

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by the presence of a chronic increase in blood sugar (hyperglycemia), accompanied by an impairment in the metabolism of glucose, lipids and proteins.1 According to the International Diabetes Federation, approximately 463 million adults (20-79 years old) live with DM, while by 2045, this number is expected to increase rapidly and reach 783 million.2

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is the most common form of diabetes and accounts for 90-95% of all cases. T2D is caused due to insufficient production of insulin or desensitization of insulin receptors that precludes the entry of glucose into the cell.3 Chronic hyperglycemia in diabetes is associated with long-term damage, dysfunction, and failure of various organs and tissues.1 Complications from diabetes can be classified as microvascular or macrovascular. Microvascular complications include nervous system damage (neuropathy), renal system damage (nephropathy) and eye damage (retinopathy). Macrovascular complications include cardiovascular disease, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease.4

Physical activity (PA) and exercise programs are the cornerstones in managing DM, along with dietary and pharmacological interventions.5 Exercise plays a significant role both in the prevention and control of T2D and diabetes-related health complications.6 Current guidelines recommend that patients with T2D should perform at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise per week along with resistance exercises (at least 3 times/week). Engaging T2D patients in aerobic and resistance exercises for more than 150minutes per week is proven effective in their glycemic control and the prevention of cardiovascular diseases.7

Despite the well-known benefits of exercise, patients with T2D are less likely to meet the recommendations for exercise; thus, their compliance appears to be extremely low.8 It must be mentioned, though, that physical inactivity and sedentary lifestyle increase risk and potentially worsen chronic health conditions.9 The main barriers to exercise participation are lack of time, accessibility, low personal motivation, and the Covid-19 pandemic.10, 11 Additionally, socio-demographic factors, long-distance traveling to rehabilitation facilities, or working obligations hinder participation in either hospital-based or outpatient rehabilitation programs.12, 13 Exercise is perceived as costly in terms of time, organization, and personal investment.14 As a result, a high percentage of patients do not benefit from the advantages of attending rehabilitation programs.12, 13

Telemedicine is a promising approach to delivering personalized health care at home, providing certain benefits, such as improved access to healthcare services, qualitative enhancement of healthcare management, and reducing potential cost and time.14, 15 Telehealth interventions positively improve DM control self-management in primary healthcare settings. Previous diabetes-telemedicine and telerehabilitation (TR) interventions aimed to develop efficient lifestyle behavior changes, which included blood glucose monitoring, dietary and PA consultancy, and psychosocial support.16 A review on telehealth interventions (smartphones, mobile applications and wearable devices) in T2D patients reported that mobile phone-based interventions with clinical feedback improved the levels of HbA1c compared to standard care or other non-health approaches by as much as 0.8%.17 The use of telehealth in monitoring HbA1c levels suggests that telemonitoring effectively controls HbA1c levels in patients with T2D.14 According to a recent meta-analysis, smartphone application-based diabetes self-management intervention could significantly improve glycemic control and self-management performance.18 Furthermore, the implementation of a remote, tele-assessed 6MWT performed outdoors appears as a valid and reliable tool to assess T2D patients’ functional capacity.19

Even though some studies have evaluated the efficacy of telehealth interventions in the management of T2D, the literature review reveals limited data concerning exercise-based TR interventions. Diabetes-TR may be more comprehensive and effective in managing T2D patients by addressing modifiable factors such as exercise.20 In TR, patients are not restricted to a community-based environment and can safely implement the rehabilitation components within their daily routine at home.21 Although there is only one supervised TR study in the existing literature on patients with T2D,22 our study is the first to examine the efficacy of a supervised TR program according to exercise recommendations (combined aerobic and resistance training). Therefore, it is essential to create interventions that circumvent the barriers to exercise for patients with diabetes. TR may be effective as part of a rehabilitation program in increasing patient adherence to exercise by minimizing barriers such as geographical distance and time constraints. Previous exercise-based TR studies have shown that a six weeks period of exercise intervention is a sufficient period to gain health benefits.23 The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of TR on glycemic control, functional capacity, muscle strength, PA, quality of life and body composition.

Materials and methods

Study design

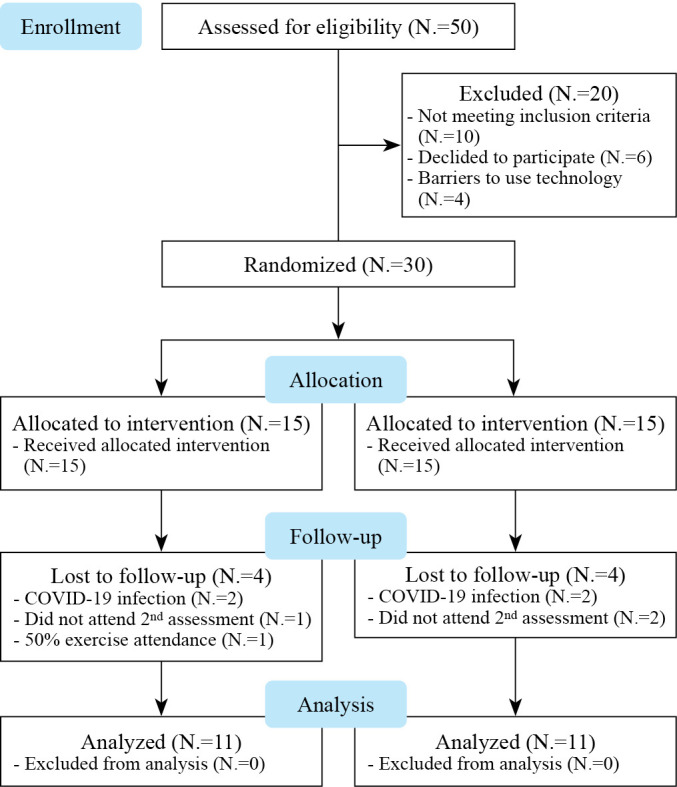

A multicenter, single-blind, randomized, parallel-group pilot study (NCT05145465, ClinicalTrials.gov) was conducted to examine the effectiveness of a supervised home-based TR program in patients with T2D. All patients signed informed consent prior to participating in the study. This study included: recruitment, baseline assessment, randomization, 6 weeks of intervention via TR, and follow-up assessment). The flowchart of the study design is shown in Figure 1. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Thessaly (Protocol Record 716/23-09-2021). The study inclines to CONSORT guidelines of reporting trials.

Figure 1.

—Study flowchart.

Study sample

Fifty patients with T2D, both men and women, were recruited from the General Hospital of Lamia, private diabetic clinics in Lamia, and the regional Association of Diabetic Patients. Inclusion criteria were: 1) patients aged above 40 years; 2) diagnosis of T2D based on the criterion of the American Diabetes Association; 3) patients who were under medical supervision and were receiving medication to regulate sugar levels properly. Exclusion criteria were the coexistence of: 1) type 1 DM; 2) neurological disease; 3) recent surgery; 4) unstable cardiovascular diseases; and 5) dementia.

Recruitment/randomization

Participants’ recruitment was fulfilled in 2 steps. Initially, fifty (50) potential patients were recruited and checked for eligibility based on their medical records. Out of the 50 patients, 30 met the inclusion criteria and were further randomly assigned into two groups via a computerized allocation system applying an algorithm in proportion 1:1. Finally, 15 patients were randomly assigned to the intervention group (IG) and 15 to the control group (CG).

Sample size

Sample size calculation was performed with the software G*Power 3.1.9.4. For the F test, the detection of small effect size (f=0.2) at a predetermined a=0.05 and b=0.80, a total of 24 participants were required to examine the recurrent ANOVA. After adjusting for the potential of dropouts (estimated attrition rate of 10%), a minimum sample of 28 patients was required.

Data collection and blinding

The same qualified physiotherapist-assessors performed all clinical assessments at baseline and after the intervention. All assessors were blinded to group allocation and were not involved in the intervention. Intervention via TR was conducted by a different qualified physiotherapist who was not involved in the assessments. Patients were not possible to be blinded to allocation. At the end of each assessment, the data was stored, and the researchers had no further access. Data were encoded in a spreadsheet and sent to another researcher to perform the data analysis.

Intervention

The IG received a 6-week supervised exercise-based TR program, 3 times a week, for 60 minutes per session. TR exercise was implemented in each patient’s home environment. Patients in the CG did not receive supervised exercise during the study period. Patients from both groups received verbal and written general information on diabetes, self-care, exercise, PA and diet recommendations. All patients also obtained written support material about exercise types, intensity, and duration.

TR intervention

Under the supervision of a physiotherapist, patients of the IG attended a first educational session at the university facilities for familiarization with the exercise training modalities and the use of the monitoring equipment (pulse oximeter, blood pressure monitor, glucose monitor, smartwatches, or activity trackers). Skype platform was installed on each patient’s mobile device (laptop, tablet, smartphone) during the educational session, and a test video call was performed individually for each patient.

Aerobic and resistance training were individually prescribed for each patient at the beginning of the first session at the university facilities as mentioned above. The patient’s vital signs [pulse rate and blood pressure (BP-B2 Easy, Microlife Corporation, Widnau, Switzerland), oxygen saturation - SpO2 (Pulse Oximeter FOX-350, I-TECH, Italy), and blood glucose (FreeStyle Lite [Abbott Diabetes Care Inc., Alameda, CA, USA] were measured and recorded at rest position). Aerobic exercise intensity was initially set for all patients at 60% heart rate (HR) reserve and gradually increased each week. The target HR zone was calculated using the Karvonen formula and the prediction of HRmax was calculated in accordance with the patient’s β-blockers therapy.24, 25 The target intensity of exercise was prescribed in intensity ranging from 60% to 80% according to exercise guidelines (Table I). Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) was used to prescribe resistance training. The patients in the educational session performed resistance evaluation of the upper and lower muscles using a weight that they could lift 10 times in a row. The target intensity was selected so that the RPE score ranged from 13-14 on the Borg (6-20 RPE) Scale. A score of 14 may correspond with 8-12 repetitions of 40% 1RM during resistance training for elderly individuals. Patients in our study performed two sets of 10 repetitions and exercise intensity ranged from 13-14 of RPE (“somewhat hard”). For the upper extremity, patients used household items (e.g., water bottles, cans) and ankle weights for the lower body. Each patient was given the necessary equipment only for the lower body.

Table I. — Aerobic training prescription.

| Τarget-training HR=HRrest+(60-80% of HRreserve), ΗRreserve=HRmax-HRrest, Prediction of HRmax when patients receiving β-blockers therapy (37) Without beta-blocker medication=206.9 – (0.67 x age) With beta-blocker medication=164 – (0.7 x age) |

Following initial training, all patients in the IG group received a TR program over 6 weeks via internet-based video conferences under the direct supervision of a physiotherapist. The TR program was delivered via a synchronous videoconferencing platform to groups of up to four patients; thus, enabling real-time monitoring, feedback, and exercise modification. Patients attended three sessions of 60 minutes of exercise per session per week. Each session consisted of a 10-minute warm-up, 40-minutes of aerobic and strength exercises, and a 10-minute recovery time (Table II).

Table II. — Telerehabilitation exercise program.

| Warm up/duration 10 minutes | |

| Marching on the spot (5 minutes) Stretching: Hamstrings, quadriceps, calf, triceps, biceps, chest, latissimus dorsi (5 minutes) | |

| Aerobic exercise training/duration 20 minutes continuous | Resistance training/duration 20 minutes |

| Intensity: Target training HR= HRrest+(60 - 80% HRreserve) Marching on the sport Modified jumping jacks side & back Mini Squats Knee to Elbow Lunges Step up Box only hands Box with lateral steps Box with back steps Lateral steps with back kick |

Intensity: 13-14 RPE 2 sets 10 repetitions each set Resting <60’ between sets Mini squats Sit-to stand Biceps curl Front-chest Wall press Knee extension Hip abduction Hip extension Hamstring curl |

| Recovery time | Duration 10 minutes 5 minutes 5 minutes |

| Marching on the spot Stretching (same as warm up) Calf raises |

|

Exercise safety in patients with T2D

An essential aspect of our study was to increase the medical safety of exercise intervention. Patients with T2D who plan to increase their exercise activity or are at high-risk levels (coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, hypertension, cigarette smoking, dyslipidemia, retinopathy, or nephropathy), may benefit from taking a medical checkup and possible exercise stress test before starting such activities7. However, pre-exercise medical clearance is unnecessary for asymptomatic individuals receiving diabetes care with low- or moderate-intensity PA prescription.7 All patients in our study followed a thorough medical examination by diabetologists and met lower-risk criteria; thus, routine exercise testing with spiroergometry and ECG monitoring was not advised. Another essential aspect when patients with T2D participate in exercise is the search for potential hypoglycemia risks.

Furthermore, all exercise experts must be aware of patients’ medication to ensure safety during exercise. Beta-blockers reduce HR during exercise, diuretics can lead to dehydration and electrolyte imbalances, and statins can lead to myopathy (myalgia, myositis). Furthermore, it is necessary to emphasize that healthcare workers, especially physiotherapists providing exercise-based intervention, should be educated and skilled in cardiopulmonary resuscitation.26

Safety during TR

All exercise TR sessions were implemented under the direct real-time supervision of a physiotherapist. Furthermore, all patients in TR had their own home-telemonitoring devices such as pulse oximeter, blood pressure monitor, glucose monitor, and some patients owned smartwatches or activity trackers. Patients were guided to self-monitor and report their blood sugar, blood pressure, HR, and SpO2 levels at the start and end of each TR session. The patients monitored HR and SpO2 during the entire TR session. Due to constant movement of patients during the aerobic exercise, pulse oximeters did not always record the HR. As a result besides the pulse oximeter, the RPE scale was used in order to help the patients to be aligned with the prescribed HR intensity during the aerobic training session. To ensure training safety, all patients had to display a HRrest<120 bpm, resting systolic and diastolic blood pressure less than 180 mmHg and 100 mmHg, respectively, and SpO2>90% before entering a session. Patients were informed about the hypoglycemic symptoms (feeling of dizziness, fatigue, palpitation, or general discomfort) and were advised to stop exercising at their occurrence.27 Education material with safety precaution instructions was provided to each patient for self-management knowledge and diabetes education.

Outcome measures

Patients were assessed at baseline and after the completion of the intervention. Primary outcomes were glycemic control (HbA1c), functional capacity, and muscle strength. Secondary outcomes included level of PA, quality of life and anthropometric measurements.

Primary outcomes

Functional capacity

Functional capacity was evaluated via the six-minute walk test (6MWT) following the American Thoracic Society’s criteria.28 The 6MWT is a reliable test that complements functional capacity assessment in patients with T2D.29 Two 6MWTs were conducted to account for a learning effect, and the test with the best score was used in statistical analysis.30 The patients rested for at least 10 minutes before performing the first 6MWT, and for at least 30 minutes between tests or until SpO2, HR, and exertion had returned to resting levels. The patients were encouraged to walk as far as possible in 6 minutes in a 30-m-long indoor corridor with cones at the end. Blood pressure (BP B2 Easy, Microlife Corporation), HR, SpO2 (Pulse Oximeter FOX-350, I-TECH, Sassuolo, Modena, Italy) and RPE were measured before and after the test, and the 6MWT distance was recorded.31, 32

Muscle strength

Upper body strength: Hand Grip Strength Test (HGS) (Sammons Jamar Hydraulic Hand Dynamometer, Sammons Preston, Bolingbrook, IL, USA), was used to assess upper body muscular strength, in accordance with the American Society of Hand Therapists.33 Patient was sitting on a chair with back support, knees and hips were bent at about 90°, shoulders adducted and neutrally rotated, elbow flexed at 90°, forearm in neutral and wrist between 0 and 30° of dorsiflexion. Each patient performed the test three times with the dominant arm, allowing a 1-minute rest period between measures. The grip position of the dynamometer was adjusted to each individual’s hand size.34 The average of the three tests was selected for the statistical analysis. Test-retest reliability for HGT in diabetic patients was 0.98 (ICC, 95% confidence interval), and the minimal detectable change (MDC) score was 4.0 kg.29

Lower body strength: the 30-Second Chair Stand Test (30CST) was used to assess lower body strength and endurance. Only the number of full stands that the patient could raise to a complete stand from a seated position with back straight and feet flat on the floor with the arms folded across the chest within 30 seconds were taken into account. A standard chair (44 cm height) was used. Test-retest reliability for 30CTS in diabetic patients was 0.92 (ICC, 95% confidence interval), and MDC score was 3.3 repetitions.27

Secondary outcomes

PA

The patients’ PA level was assessed with the Greek version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF), which is a valid and reliable assessment tool for the Greek population.35

Quality of life

Quality of life was assessed via the Greek-translated version of the SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36): The self-administered SF-36 questionnaire is a 36-item scale that measures eight aspects of Health-Related Quality of Life. It measures the following scales: physical functioning, physical health, bodily pain, general health, vitality, emotional role, social functioning, and mental health.36

Anthropometric characteristics

Anthropometric characteristics included height, weight, Body Mass Index (BMI), hip circumference measurement, waist circumference measurement, and waist/hip ratio. Height was measured using a stadiometer (SECA 213, seca GmbH & Co, Hamburg, Germany), and weight was measured with a digital scale (Tanita, Tanita Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Body Mass Index was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m2). Waist/hip ratios were also calculated. Waist and hip circumference were measured with a tape measure. Waist circumference (WC) was taken from the umbilicus level, and hip circumference was taken from the femur trochanter major. Both measurements were conducted during the exhalation phase using a tape measure while the patient was standing on both feet with equal weight on each (the values of hip and waist measurements were recorded in centimeters).

Statistical analysis

In the IG, only the patients who completed at least 50% of all the sessions (≥9 out of 18) were included in the final analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 for Windows. Descriptive statistics were presented as (mean, standard deviation, and percentage) for both groups. A Shapiro-Wilk Test was used to examine the normality of data distribution. Paired t-tests (or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests) were conducted to examine the statistical significance of the outcomes for all dependent variables within both groups. Independent sample t-tests (or Mann-Whitney U Tests) were conducted to examine the statistical significance of the outcomes for all dependent variables between both groups. The effect size was calculated using Cohen’s d test to estimate the magnitude of the intervention’s effect on fall-related factors. Cohen classified effects as small (d=0-0.2), medium (d=0.3-0.5) and large (d≥0.6) (12). The effects were expressed by using means, SDs, mean differences, 95% CIs, % change, t-statistics, df’s, pre-post correlations (r), and P values. A two-way mixed ANOVA was used to examine the statistical significance of between-group interactions of the main effects, pre, and post-intervention. The statistical significance was set at P<0.05 in all analyses.

Results

A total of 30 T2D patients agreed to participate and were randomized to IG (N.=15), and CG (N.=15). Figure 1 shows the flow of patients throughout the study. Eight patients (IG, N.=4; CG, N.=4) dropped out during the 6-week intervention period. The attriction rate was calculated 26.6%. Reasons for dropping out included loss of interest (IG, N.=1; CG, N.=2), low exercise attendance (<50%) (IG, N.=1) and Covid-19 disease (IG, N.=2; CG, N.=2).

No serious exercise-related adverse events occurred in IG. The basic characteristics of the study population are described in Table III. The mean age was 60.3±9.3 years for the IG and 60.8±13.6 years for the CG. A total of 7 (31.8%) women participated in this study. Eleven patients (IG, N.=4 [36.4%]; CG, N.=7 [63.9%]) were receiving oral drug treatment while the rest eleven patients (IG, N.=7 [63.9%]; CG, N.=4, 36.4%]) were under insulinotherapy. Significally higher outcome measurements for BMI and WC were observed between the two groups in favor of the IG (P>0.05).

Table III. — Characteristics of the patients.

| Intervention group (IG) Mean±SD |

Control group (CG) Mean±SD |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (N.) | 11 | 11 | |

| Gender (male/female) | 8 (72.7%)/3 (27.3%) | 7 (63.9%)/4 (36.4%) | |

| Age±SD (years) | 60.3±9.3 | 60.8±13.6 | 0.9 |

| Height (cm) | 171±6.1 | 170±9.0 | 0.3 |

| Weight (kg) | 101.1±21.0 | 85.4±14.6 | 0.08 |

| BMI (kg /m2) | 34.4±5.7 | 27.9±2.8 | 0.05 |

| WHR | 0.9±0.1 | 0.9±0.1 | 0.2 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 116.0±13.3 | 100.6±7.2 | 0.05 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.4±2.1 | 6.9±1.2 | 0.3 |

Data expressed as mean±SD or N. (%). BMI: Body Mass Index; WHR: Waist Hip Ratio; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin.

Primary outcomes

Glucose control

HbA1c value was significantly decreased in the IG group at the end of the 6-week intervention period (Meanbefore: 7.4±2.2% Meanafter: 6.4±0.7%) with a large effect size (HbA1c, d=0.81). Whilst there was no significant change in the CG for HbA1c value over this 6-week intervention period (P>0.05) (Table IV).

Table IV. — Results of glucose control.

| Variables | Group | Before Mean±SD |

After Mean±SD |

Wilcoxon (Z) | P value | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c (%) | Intervention Control |

7.4±2.2 6.9±1.3 |

6.4±0.7 7.0±1.1 |

-2.70 -0.76 |

0.007 0.45 |

0.81 0.27 |

| IPAQ (METs.min/wk) | Intervention Control |

2594±2105 2940±3540 |

3351±2455 3774±2427 |

-1.06 -0.89 |

0.29 0.37 |

0.32 0.29 |

Data expressed as mean±SD. HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; IPAQ: International Physical Activity Questionnaire.

Functional capacity

There was a significant overall improvement for the IG in the 6MWD over the 6-week intervention period (P<0.05) (Mean distance before: 516m versus Mean distance after: 553m), (Mean distance Δbefore-after: -36.9±27.2), representing a large effect size on functional capacity (6MWT, d=0.81). There was no significant change in the CG for 6MWT over the 6-week intervention period (P>0.05) (Table V).

Table V. — Results of the functional capacity.

| Variables | Group | Before Mean |

After Mean |

MD before-after Mean (SD) |

t-test | P value | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6MWT(m) | Intervention Control |

516 548 |

553 549 |

-36.9 (27.2) -1.0 (39.6) |

-4.50 -0.07 |

0.001 0.94 |

0.81 0.02 |

| HGS (kg) | Intervention Control |

37.5 40.8 |

39.0 41.4 |

-1.5 (1.4) -0.6 (3.6) |

-2.22 -0.53 |

0.05 0.60 |

0.57 0.18 |

| 30CST (repetitions) SF-36 Mental health (%) SF-36 General health (%) |

Intervention Control |

12.1 14.7 |

14.1 14.6 |

-2.0 (1.3) 0.1 (1.1) |

-3.51 0.31 |

0.006 0.76 |

0.72 0.11 |

| Intervention Control |

72.2 65.3 |

85.4 65.8 |

-13.3 (21.3) -0.5 (20.6) |

-2.06 0.65 |

0.05 0.95 |

||

| Intervention | 70.9 | 82.3 | -11.40 (16.9) | -2.23 | 0.05 | ||

| Control | 77.2 | 77.8 | -0.6 (25.4) | -0.06 | 0.94 |

Data expressed as mean±SD. 6MWT: 6-Minute Walk Test; HGS: hand grip strength; 30CST: 30seconds Chair Stand Test.

Muscle strength

HGS and 30CST were statistical significantly improved in the IG over the 6-week intervention period (P<0.05) (HGS: [mean strength before: 37.5 kg versus mean strength after: 39 kg], [Mean strength Δbefore-after: -1.5±1.4 kg]), (30CST: [mean repetitions before: 12.1 versus mean repetitions after: 14.1], [mean repetitions Δbefore-after: -2.0±1.3 rep]). The magnitude of the differences in the IG represents a medium effect size on the upper body muscular strength (HGS, d=0.57) and a large effect on lower extremity strength (30CST, d=0.72). There were not significant changes in the CG for the HGS and 30CST over this 6-week period (Table V).

Secondary outcomes

PA

IPAQ scores did not statistically significant changed both in the IG and CG over the study period (Table IV).

Quality of life

For the SF-36 questionnaire, only two of the eight aspects significantly changed in the IG over the 6-week intervention period. In particular Mental Health and General Health significantly improved (mental health [mean before: 72.2% versus Mean after: 85.4%], [Mean Δbefore-after: -0.5±20.6%]), (general health [mean before: 70.9% versus mean after: 82.3%], [mean Δbefore-after: -0.6±25.4%]). There were no significant changes in any of the eight aspects of SF-36 in the CG over this study period (Table V).

Body composition

A statistically significant decrease was observed only in the IG over the 6-week intervention period for the weight (mean weight before: 101.2 kg versus mean weight after: 99.0 kg], [mean weight Δbefore-after: 1.8±2.3 kg]), ΒΜΙ ([mean value before: 34.4 versus mean value after: 33.4], [mean value Δbefore-after: 0.6±0.7 (kg/m2)] and WC [mean circumference before: 116 cm versus Mean circumference after: 112 cm], [mean circumference Δbefore-after: 3.3±2.5 cm]). The magnitude of the differences in the IG represents a large effect size on body composition (weight, d=0.61), (BMI, d=0.64) and (waist circumference, d=0.80). There were no statistically significant changes in any of these characteristics in the CG over this study period (P>0.05) (Table VI).

Table VI. — Results of the body composition.

| Variables | Group | Mean (before) | Mean (after) | Mean Difference (before-after) | t-test | P value | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | Intervention | 101.2 | 99.4 | 1.80 (2.25) | 2.50 | 0.03 | 0.61 |

| Control | 85.5 | 86.3 | -0.86 (1.90) | -1.32 | 0.22 | 0.42 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | Intervention | 34.4 | 33.8 | 0.60 (0.70) | 2.70 | 0.02 | 0.64 |

| Control | 27.9 | 28.2 | -0.30 (0.70) | -1.23 | 0.25 | 0.40 | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | Intervention | 116.0 | 112.0 | 3.30 (2.50) | 4.35 | 0.001 | 0.80 |

| Control | 100.5 | 101.2 | -0.60 (1.26) | -1.42 | 0.2 | 0.45 | |

| WHR (value) | Intervention | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.01 (0.02) | 1.90 | 0.08 | 0.51 |

| Control | 0.94 | 0.95 | -0.01 (0.01) | -1.55 | 0.16 | 0.48 |

Data expressed as mean±SD. BMI: Body Mass Index; WHR: Waist Hip Ratio.

Comparison of measurement changes between the intervention and control group

The results of the two-way ANOVA showed a significant interaction of time and group, for the 6MWT and HGS Test, between the IG and the CG. Box’s Test was found to be non-significant (P=0.026). Based on Pillai’s Trace ANOVA revealed statistically significant effect between groups, time and (6MWT and HGS) and revealed a significant effect (V=0.33, F [2.17]=4.14, P=0.03, partial η2=0.22). Partial Eta squared (ηp2) in both groups indicates a high effect size (ηp2=0.65) (Table VII).

Table VII. — Comparison of measurement changes between the intervention and control group.

| Variables | Effects | Team x time F (2.17) |

η2 | P value | Observed power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group*Time | 4.14 | 0.38 | 0.03 | 0.65 | |

| 6MWT (m) | Time effect | 6.42 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.66 |

| Group*Time | 5.75 | 0.24 | 0.027 | 0.62 | |

| HGS (kg) | Time effect | 1.78 | 0.09 | 0.199 | 0.24 |

| Group*Time | 0.06 | 0.003 | 0.812 | 0.057 |

Discussion

The primary aim of the current study was to determine the short-term effectiveness of a supervised TR exercise program for patients with T2D. The findings of this study indicate that a 6-week supervised TR exercise program induced significant benefits in patients with T2D. The TR group attented an average of 15 out of 18 TR sessions, which is an indicate of a very good compliance. The main reasons for not attending at those sessions were mostly the bad internet connection and urgent family reasons.

In our study, we ensured patients’ safety during exercise sessions through individual exercise prescriptions, the use of monitor devices, and real-time supervision. Prescribing a diabetic’s exercise endurance intensity by percentages of maximal HR or HR range and not based on individual thresholds may lead to overload of exercise intensity.37 Therefore, it is advised to take the resting HR into account and calculate the HR reserve for more accurate endurance training intensity determination in patients with T2D. Taking this into consideration, in our study, we prescribed the exercise endurance intensity using the resting HR through the Karvonen formula in accordance with patients’ medication (beta-blockers).25 Beta-blockers can slow HR response to exercise and lower maximal exercise capacity due to their chronotropic and inotropic negative effects.38

In our study, the real-time supervision and telemonitoring of the exercise sessions by a physiotherapist may have also contributed to the prevention of acute adverse events. The regular monitoring of the blood glucose levels (immediately before and after exercise training, and a few hours after exercise training) was implemented in every session, as recommended for safety reasons.39 In case of hypoglycemia (glucose level <100 mg/dL), patients received one light snack prior to the session, and in case of hypoglycemia during the exercise, the instruction was to stop the exercise immediately and consume fast-acting carbohydrates (sugar or juice). According to a previous study, ECG monitoring during cardiac rehabilitation is unnecessary when patients are low-risk and can safely exercise in community-based cardiac rehabilitation settings.40 All patients in our TR study had an initial 6MWT distance higher than 450 m which is also higher than the values in the literature for healthy individuals.

Another important innovative aspect of our study was the inclusion of low-cost exercise strategies. Our exercise program has been proven feasible, easy to implement, and has potential for home-based environmental, since it does not require expensive equipment or spacious indoor facilities.

Recent studies reported that telehealth interventions effectively improve glycemic control and can lead to an approximately 0.22-0.64% decrease in HbA1c levels in patients with T2D.41-43 Most of these interventions included synchronous and asynchronous approaches (via email, video conference and mobile applications). However, there are hardly any TR studies involving exercise in patients with T2D in the literature. Our study found a 0.99% decrease in HbA1c levels in the TR group, while in the CG, HbA1c did not change. Similarly, in the study of Duruturk & Özköslü, patients who performed a supervised home-based exercise program significantly decreased their HbA1c levels.22

Besides being an important indicator of long-term glycemic control, the HbA1c level is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease in patients with T2D. According to Stratton et al., a reduction in HbA1c levels by 1% can reduce the risk of microvascular complications by 37% and death related to diabetes by 21%.44 The weekly amount of exercise indicates a significant role in improving glycemic control. In a previous exercise telemonitoring study (tele-HR monitor and weekly phone calls for six months), patients did not improve HbA1c% or quality of life even though they presented higher exercise attendance rates compared to the control group, probably due to insufficient exercise volume.45

Another important factor in TR studies is feedback. In our study, exercise supervision was implemented via video conference supervision, thus, enabling real-time monitoring, feedback, and direct exercise modification for each patient. TR interventions that involved more interaction between healthcare providers and patients or personalized patient feedback were more likely to improve HbA1c.46 In contrast, a previous telemedicine study found that patients in an internet-based exercise group achieved a 0.9% decrease in HbA1c even though the exercise was implemented only via asynchronous video feedback, without supervision or a personalized interaction between patients and healthcare providers.47

Functional capacity is a strong predictor of mortality in T2D patients, and it has been observed that patients with T2D are associated with lower functional capacity compared to healthy subjects. A previous study has shown a clinically significant 21-23% reduction in mortality risk for every 1-MET increase in the functional capacity of patients with T2D.48 Regarding functional capacity, we found that the 6MWT distance was improved only in IG by 36.9m. This result demonstrates that the intervention was effective since the MDC in the 6MWT in patients with T2D was found to be 27.37m.29 Similar to these results in the study of Duruturk & Özköslü, patients in the TR group significantly improved functional capacity. Previous diabetes telehealth studies without exercise supervision have also shown improvements in functional capacity.45, 47

Regarding muscle strength, we only found a significant improvement in both upper and lower body muscle strength in the TR group. HGS test improved by 1.5 kg and 30CST by 2 repetitions. The magnitude of these differences represents a medium effect size on the upper body muscular strength (HGS, d=0.57) and a significant effect on lower extremity strength (30CST, d=0.72). Similar to these results, muscle strength improved in other TR exercise studies in cardiac, cancer, and Covid-19 patients.49, 50 The only TR study with real-time exercise supervision in patients with T2D showed improvements in upper-body muscle strength.22 However, the measurements of the 30CST did not significantly change after the intervention period. These differences may be due to the exercise-protocol design since our prescription implemented combined aerobic and resistance training, while in the study of Duruturk & Özköslü, patients followed calisthenics exercise without additional resistance.22

In our study, PA was measured by a self-reported method and did not significantly change both in IG and CG. This may be caused by patients’ higher baseline PA levels and a lower potential for further improvements. The patient’s baseline PA levels were 2594 METs.min/wk for IG and 2940 METs.min/wk for CG, higher than the values given in the literature for healthy controls within the same age group. Measuring PA by self-reporting methods might have caused over-reporting.51 In a previous TR study, PA was measured with pedometers, and an increase in the average number of steps was detected after the treatment in both IG and CG.47 Previous studies support that using self-monitoring technologies such as pedometers can enhance motivation and disease self-management in patients with T2D.52

In terms of quality of life, better scoring levels are associated with a lower level of HbA1c.53 Additionally, a decrease in HbA1c levels is associated with improved psychological outcomes of quality of life.22, 45, 47 In our study, significant increases were noted in terms of mental and general health by 13.4% and 11.4%, alongside levels of HbA1c.

Regarding body composition measures, IG significantly decreased their body weight by 1.7 kg, BMI by 0.57 kg/m2, and WC by 3.3 cm. A previous study has shown that combined supervised exercise is more effective in weight reduction than unsupervised exercise.54 Moreover, BMI did not significantly change after a home-based unsupervised exercise program, while patients significantly decreased WC.47 WC is more reflective of visceral obesity than BMI.55 In another study, even though BMI did not change after a TR intervention, patients improved body mass which is a more important indicator than BMI in predicting risk for T2D.56 Thus, the limited effect of the intervention on body composition could be due to the short duration of the intervention or due to the patient’s dietary habits. Although our patients received general information and advice on diabetic diet, they did not receive an individualised dietary counselling. Therefore, future TR studies should design a more extended intervention period to improve cardiovascular risk factors in the long term.57, 58 Moreover, considering a comprehensive approach, it would be essential to include nutritional support through the Mediterranean diet in the real-time intervention, which could have even more significant impacts on the secondary prevention of major cardiovascular events.59

Limitations of the study

Among the limitations of this study is the short-term duration of the intervention. Due to the study design, it was not possible to blind patients to study allocation. In addition, the small sample size was and the genderly inbalanced sample indicate bias. BMI and WC at baseline outcome measurements were not similar in both groups; particular parameters were significantly higher in the IG. Another limitation is that patient’s telemonitoring devices were not assessed in terms of reliability and validity. In addition, most of the patients were using a pulse oximeter in order to track the average adhered HR, which due to constant movement did not always record the HR.

Conclusions

The findings of this study contribute to the growing body of evidence about the use of TR for T2D management while providing further information for clinicians. The results support telehealth implementation in rehabilitation practice as an alternative approach. Future TR studies should focus on long-term comprehensive exercise interventions using accurate wearable devices in larger populations.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge clinical physiotherapist for their support in this work.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest :The authors certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

Funding :This research was funded by the Ministry of Health, Czech Republic; conceptual development of research organization (FNBr, 65269705).

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association . 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care 2020;43(Suppl 1):S14–31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=31862745&dopt=Abstract 10.2337/dc20-S002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2022;183:109119. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=34879977&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahn SE, Cooper ME, Del Prato S. Pathophysiology and treatment of type 2 diabetes: perspectives on the past, present, and future. Lancet 2014;383:1068–83. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=24315620&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62154-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Diabetes Association . (2) Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015;38(Suppl):S8–16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=25537714&dopt=Abstract 10.2337/dc15-S005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amanat S, Ghahri S, Dianatinasab A, Fararouei M, Dianatinasab M. Exercise and Type 2 Diabetes. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020;1228:91–105. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32342452&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/978-981-15-1792-1_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sgrò P, Emerenziani GP, Antinozzi C, Sacchetti M, Di Luigi L. Exercise as a drug for glucose management and prevention in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2021;59:95–102. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=34182427&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.coph.2021.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, Regensteiner JG, Blissmer BJ, Rubin RR, et al. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Diabetes Care 2010;33:147–67. 10.2337/dc10-9990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duclos M, Dejager S, Postel-Vinay N, di Nicola S, Quéré S, Fiquet B. Physical activity in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension—insights into motivations and barriers from the MOBILE study. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2015;11:361–71. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=26170686&dopt=Abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patterson R, McNamara E, Tainio M, de Sá TH, Smith AD, Sharp SJ, et al. Sedentary behaviour and risk of all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality, and incident type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose response meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol 2018;33:811–29. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=29589226&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s10654-018-0380-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin CG, Pomares ML, Muratore CM, Avila PJ, Apoloni SB, Rodríguez M, et al. Level of physical activity and barriers to exercise in adults with type 2 diabetes. AIMS Public Health 2021;8:229–39. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=34017888&dopt=Abstract 10.3934/publichealth.2021018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pepera G, Tribali MS, Batalik L, Petrov I, Papathanasiou J. Epidemiology, risk factors and prognosis of cardiovascular disease in the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic era: a systematic review. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2022;23:28. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=35092220&dopt=Abstract 10.31083/j.rcm2301028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winnige P, Filakova K, Hnatiak J, Dosbaba F, Bocek O, Pepera G, et al. Validity and Reliability of the Cardiac Rehabilitation Barriers Scale in the Czech Republic (CRBS-CZE): Determination of Key Barriers in East-Central Europe. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:13113. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=34948722&dopt=Abstract 10.3390/ijerph182413113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antoniou V, Pasias K, Loukidis N, Exarchou-Kouveli KK, Panagiotakos DB, Grace SL, et al. Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Psychometric Validation of the Greek Version of the Cardiac Rehabilitation Barriers Scale (CRBS-GR): What Are the Barriers in South-East Europe? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023;20:4064. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=36901075&dopt=Abstract 10.3390/ijerph20054064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batalik L, Filakova K, Sladeckova M, Dosbaba F, Su J, Pepera G. The cost-effectiveness of exercise-based cardiac telerehabilitation intervention: a systematic review. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2023;59:248–58. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=36692413&dopt=Abstract 10.23736/S1973-9087.23.07773-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antoniou V, Davos CH, Kapreli E, Batalik L, Panagiotakos DB, Pepera G. Effectiveness of Home-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation, Using Wearable Sensors, as a Multicomponent, Cutting-Edge Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med 2022;11:3772. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=35807055&dopt=Abstract 10.3390/jcm11133772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milani R, Chava P, Wilt J, Entwisle J, Karam S, Burton J, et al. Improving Management of Type 2 Diabetes Using Home-Based Telemonitoring: cohort Study. JMIR Diabetes 2021;6:e24687. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=34110298&dopt=Abstract 10.2196/24687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitsiou S, Paré G, Jaana M, Gerber B. Effectiveness of mHealth interventions for patients with diabetes: an overview of systematic reviews. PLoS One 2017;12:e0173160. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=28249025&dopt=Abstract 10.1371/journal.pone.0173160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He Q, Zhao X, Wang Y, Xie Q, Cheng L. Effectiveness of smartphone application-based self-management interventions in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Adv Nurs 2022;78:348–62. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=34324218&dopt=Abstract 10.1111/jan.14993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pepera G, Karanasiou E, Blioumpa C, Antoniou V, Kalatzis K, Lanaras L, et al. Tele-Assessment of Functional Capacity through the Six-Minute Walk Test in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Type 2: Validity and Reliability of Repeated Measurements. Sensors (Basel) 2023;23:1354. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=36772396&dopt=Abstract 10.3390/s23031354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan SY, Mei Wong JL, Sim YJ, Wong SS, Mohamed Elhassan SA, Tan SH, et al. Type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus: A review on current treatment approach and gene therapy as potential intervention. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2019;1:364–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antoniou V, Xanthopoulos A, Giamouzis G, Davos C, Batalik L, Stavrou V, et al. Efficacy, efficiency and safety of a cardiac telerehabilitation programme using wearable sensors in patients with coronary heart disease: the TELEWEAR-CR study protocol. BMJ Open 2022;12:e059945. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=35738643&dopt=Abstract 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duruturk N, Özköslü MA. Effect of tele-rehabilitation on glucose control, exercise capacity, physical fitness, muscle strength and psychosocial status in patients with type 2 diabetes: A double blind randomized controlled trial. Prim Care Diabetes 2019;13:542–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=31014938&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.pcd.2019.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dadgostar H, Firouzinezhad S, Ansari M, Younespour S, Mahmoudpour A, Khamseh ME. Supervised group-exercise therapy versus home-based exercise therapy: their effects on Quality of Life and cardiovascular risk factors in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2016;10(Suppl 1):S30–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=26822461&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.dsx.2016.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Batalik L, Pepera G, Papathanasiou J, Rutkowski S, Líška D, Batalikova K, et al. Is the Training Intensity in Phase Two Cardiovascular Rehabilitation Different in Telehealth versus Outpatient Rehabilitation? J Clin Med 2021;10:4069. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=34575185&dopt=Abstract 10.3390/jcm10184069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brawner CA, Ehrman JK, Schairer JR, Cao JJ, Keteyian SJ. Predicting maximum heart rate among patients with coronary heart disease receiving beta-adrenergic blockade therapy. Am Heart J 2004;148:910–4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15523326&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pepera G, Xanthos E, Lilios A, Xanthos T. Knowledge of cardiopulmonary resuscitation among Greek physiotherapists. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2019;89. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=31711281&dopt=Abstract 10.4081/monaldi.2019.1124 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Stefanakis M, Batalik L, Antoniou V, Pepera G. Safety of home-based cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review. Heart Lung 2022;55:117–26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=35533492&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2022.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories . ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12091180&dopt=Abstract 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alfonso-Rosa RM, Del Pozo-Cruz B, Del Pozo-Cruz J, Sañudo B, Rogers ME. Test-retest reliability and minimal detectable change scores for fitness assessment in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Rehabil Nurs 2014;39:260–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=23780835&dopt=Abstract 10.1002/rnj.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spencer LM, Alison JA, McKeough ZJ. Six-minute walk test as an outcome measure: are two six-minute walk tests necessary immediately after pulmonary rehabilitation and at three-month follow-up? Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2008;87:224–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=17912139&dopt=Abstract 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181583e66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1982;14:377–81. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=7154893&dopt=Abstract 10.1249/00005768-198205000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pepera GK, Sandercock GR, Sloan R, Cleland JJ, Ingle L, Clark AL. Influence of step length on 6-minute walk test performance in patients with chronic heart failure. Physiotherapy 2012;98:325–9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=23122439&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.physio.2011.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacDermid J, Solomon G. Therapists ASoH. Clinical assessment recommendations 3rd edition: Impairment-based conditions. Third edition ed: Mount Laurel, NJ: American Society of Hand Therapists; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pepera G, Christina M, Katerina K, Argirios P, Varsamo A. Effects of multicomponent exercise training intervention on hemodynamic and physical function in older residents of long-term care facilities: A multicenter randomized clinical controlled trial. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2021;28:231–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=34776146&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.jbmt.2021.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papathanasiou G, Georgoudis G, Georgakopoulos D, Katsouras C, Kalfakakou V, Evangelou A. Criterion-related validity of the short International Physical Activity Questionnaire against exercise capacity in young adults. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010;17:380–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=19940775&dopt=Abstract 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328333ede6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pappa E, Kontodimopoulos N, Niakas D. Validating and norming of the Greek SF-36 Health Survey. Qual Life Res 2005;14:1433–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16047519&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s11136-004-6014-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moser O, Tschakert G, Mueller A, Groeschl W, Eckstein ML, Koehler G, et al. Different Heart Rate Patterns During Cardio-Pulmonary Exercise (CPX) Testing in Individuals With Type 1 Diabetes. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:585. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30333794&dopt=Abstract 10.3389/fendo.2018.00585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sigal RJ, Purdon C, Bilinski D, Vranic M, Halter JB, Marliss EB. Glucoregulation during and after intense exercise: effects of beta-blockade. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994;78:359–66. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=7906280&dopt=Abstract [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hansen D, Peeters S, Zwaenepoel B, Verleyen D, Wittebrood C, Timmerman N, et al. Exercise assessment and prescription in patients with type 2 diabetes in the private and home care setting: clinical recommendations from AXXON (Belgian Physical Therapy Association). Phys Ther 2013;93:597–610. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=23392184&dopt=Abstract 10.2522/ptj.20120400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pepera G, Bromley P, Sandercock G. A pilot study to investigate the safety of exercise training and testing in cardiac rehabilitation patients. Br J Cardiol 2013;20:78. [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Storch K, Graaf E, Wunderlich M, Rietz C, Polidori MC, Woopen C. Telemedicine-Assisted Self-Management Program for Type 2 Diabetes Patients. Diabetes Technol Ther 2019;21:514–21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=31287736&dopt=Abstract 10.1089/dia.2019.0056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eberle C, Stichling S. Clinical Improvements by Telemedicine Interventions Managing Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes: systematic Meta-review. J Med Internet Res 2021;23:e23244. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33605889&dopt=Abstract 10.2196/23244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee PA, Greenfield G, Pappas Y. The impact of telehealth remote patient monitoring on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:495. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=29940936&dopt=Abstract 10.1186/s12913-018-3274-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, Matthews DR, Manley SE, Cull CA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ 2000;321:405–12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10938048&dopt=Abstract 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marios T. A Smart N, Dalton S. The Effect of Tele-Monitoring on Exercise Training Adherence, Functional Capacity, Quality of Life and Glycemic Control in Patients With Type II Diabetes. J Sports Sci Med 2012;11:51–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=24137063&dopt=Abstract [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faruque LI, Wiebe N, Ehteshami-Afshar A, Liu Y, Dianati-Maleki N, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Alberta Kidney Disease Network . Effect of telemedicine on glycated hemoglobin in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. CMAJ 2017;189:E341–64. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=27799615&dopt=Abstract 10.1503/cmaj.150885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akinci B, Yeldan I, Satman I, Dirican A, Ozdincler AR. The effects of Internet-based exercise compared with supervised group exercise in people with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled study. Clin Rehabil 2018;32:799–810. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=29417832&dopt=Abstract 10.1177/0269215518757052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kokkinos P, Myers J, Nylen E, Panagiotakos DB, Manolis A, Pittaras A, et al. Exercise capacity and all-cause mortality in African American and Caucasian men with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32:623–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=19196898&dopt=Abstract 10.2337/dc08-1876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Batalik L, Filakova K, Radkovcova I, Dosbaba F, Winnige P, Vlazna D, et al. Cardio-Oncology Rehabilitation and Telehealth: Rationale for Future Integration in Supportive Care of Cancer Survivors. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022;9:858334. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=35497988&dopt=Abstract 10.3389/fcvm.2022.858334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cancino-López J, Vergara PZ, Dinamarca BL, Contreras PF, Cárcamo LM, Ibarra NC, et al. Telerehabilitation is Effective to Recover Functionality and Increase Skeletal Muscle Mass Index in COVID-19 Survivors. Int J Telerehabil 2021;13:e6415. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=35646231&dopt=Abstract 10.5195/ijt.2021.6415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson-Kozlow M, Sallis JF, Gilpin EA, Rock CL, Pierce JP. Comparative validation of the IPAQ and the 7-Day PAR among women diagnosed with breast cancer. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2006;3:7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=16579852&dopt=Abstract 10.1186/1479-5868-3-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lidegaard LP, Schwennesen N, Willaing I, Faerch K. Barriers to and motivators for physical activity among people with Type 2 diabetes: patients’ perspectives. Diabet Med 2016;33:1677–85. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=27279343&dopt=Abstract 10.1111/dme.13167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Daher AM, AlMashoor SA, Winn T. Glycaemic control and quality of life among ethnically diverse Malaysian diabetic patients. Qual Life Res 2015;24:951–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=25352036&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s11136-014-0830-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pan B, Ge L, Xun YQ, Chen YJ, Gao CY, Han X, et al. Exercise training modalities in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2018;15:72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30045740&dopt=Abstract 10.1186/s12966-018-0703-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Okorodudu DO, Jumean MF, Montori VM, Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Erwin PJ, et al. Diagnostic performance of body mass index to identify obesity as defined by body adiposity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes 2010;34:791–9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=20125098&dopt=Abstract 10.1038/ijo.2010.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li J, Wei D, Liu S, Li M, Chen X, Chen L, et al. Efficiency of an mHealth App and Chest-Wearable Remote Exercise Monitoring Intervention in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Prospective, Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021;9:e23338. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33560244&dopt=Abstract 10.2196/23338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Batalik L, Pepera G, Su JJ. Cardiac telerehabilitation improves lipid profile in the long term: insights and implications. Int J Cardiol 2022;367:117–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=36055472&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.ijcard.2022.08.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Batalik L, Dosbaba F, Hartman M, Konecny V, Batalikova K, Spinar J. Long-term exercise effects after cardiac telerehabilitation in patients with coronary artery disease: 1-year follow-up results of the randomized study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2021;57:807–14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33619944&dopt=Abstract 10.23736/S1973-9087.21.06653-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Delgado-Lista J, Alcala-Diaz JF, Torres-Peña JD, Quintana-Navarro GM, Fuentes F, Garcia-Rios A, et al. CORDIOPREV Investigators. Long-term secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet and a low-fat diet (CORDIOPREV): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2022;399:1876–85. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=35525255&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00122-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]