Abstract

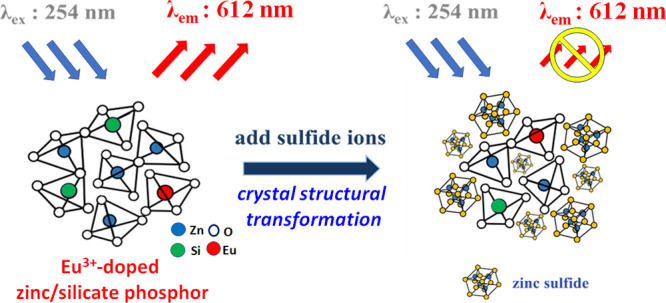

A mesoporous Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphor with a large surface area (>100 m2g–1) and amorphous structure was prepared in an aqueous solution without using any organic template. The residual concentration of the Zn2+ ion in the filtrate is lower than the standard of effluent 3.5 ppm under a pH 8–11 preparation condition. When a sulfide ion (S2–) is present in aqueous solution, the phosphor can react with the sulfide ion to transform from the amorphous structure to the crystalline ZnS, which causes structural transformation and a subsequent decrease in luminescent intensity. This distinct phosphor with a high surface area and amorphous structure can be applied through the structure transformation mechanism for highly selective and sensitive detection of the sulfide ions at low concentrations. In addition, the luminescent efficiency was obtained from adjustments in the pH value, calcination temperature, and Eu3+ ion concentration. The quenching efficiency, the limit of detection (CLOD), S2– ion selectivity, and phosphor regeneration ability were systematically explored in sulfide ion detection tests. Due to the novel S2– ion-induced structural transformation, we found that the amorphous Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors demonstrate a CLOD sensitivity as low as 1.8 × 10–7 M and a high Stern–Volmer constant (KSV) of 3.1 × 104 M–1. Furthermore, the phosphors were easily regenerated through simple calcination at 500 °C and showed a KSV value of 1.4 × 104 M–1. Overall, the Eu3+-doped zinc/silicates showed many advantageous properties for detecting sulfide ions, including low toxicity, green synthesis, good selectivity, high sensitivity, and good renewability.

1. Introduction

Sulfides exist in many forms, including hydrogen sulfides (HS–), orthosulfides (S2–), polysulfides (Sn2–), and sulfur oxides (SOx).1,2 They react easily with acidic solutions to produce corrosive and toxic hydrogen sulfide (H2S) gas.3 Even in concentrations as low as 4.7 × 10–4 ppm, H2S significantly adversely affects human health.4 In Taiwan, the effluent standard for the sulfide ion is 1.0 ppm. Moreover, the H2S interacts strongly with metal and can damage metal pipelines, corrode metallic equipment, and poison catalysts.5,6 Furthermore, fossil fuels usually produce large amounts of SOx on combustion, forming sulfuric acid fog and contributing to acid rain.7 Consequently, the need for efficient methods to detect and remove sulfide compounds is a significant concern nowadays.8

Many methods have been proposed for sulfide detection, including photochemical,9,10 titrimetric,11 electrochemical,12,13 and ion chromatographic.14 In traditional spectrophotometry methods, dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine (DMPD) reacts with H2S in water under acidic conditions to produce methylene blue.15 The concentration of sulfide ions in the water is then evaluated by measuring the intensity of the methylene blue emissions at a wavelength of 664 nm. Studies have shown that the limit of detection (CLOD) can be as much as 1.6 × 10–6 M when using such methods.16 However, while this CLOD is adequate for detecting sulfide ions at concentrations as low as 1.0 ppm (around 3.1 × 10–5 M) in wastewater,17 DMPD is toxic and carcinogenic to humans. Moreover, the methylene blue produced in the reaction process is environmentally unfriendly.18 Consequently, synthesizing highly selective, stable, and reusable sulfide ion detection materials has been required.

According to the literature,19−22 zinc silicate converts to Willemite (Zn2SiO4) crystalline phase under high-temperature treatment. The Willemite can then be used as a host material for many luminescence ions. For example, phosphors with different luminescence wavelengths can be obtained by incorporating metal ions with empty orbital domains into the Willemite crystal structure. In 1994, Blasse et al. discovered that Zn2SiO4 doped with Eu3+ exhibits red luminescence properties and has excellent luminescence efficiency.20,21 Wang et al. used the ZnO/SiO2 nanocomposite as the sulfide sensor based on room-temperature phosphorescence.19 However, most existing methods for synthesizing phosphors are complex and environmentally nonfriendly.18−20

Consequently, researchers have proposed various methods for synthesizing high surface area phosphors using porous materials as hard templates or surfactants as soft templates.23,24 These synthesis routes require a high temperature (greater than 150 °C) reaction system, prolonged reaction time (longer than 3 days), or waste of organic chemicals. This makes the synthesis process hazardous, the emission of greenhouse gas CO2, and energy- and time-consuming. Moreover, the residue solution containing toxic transition-metal ions and organic templates cannot be easily decomposed naturally; hence, environmental pollutants are often produced.

In the present study, the mesoporous Eu3+-doped zinc/silicates emitting red luminescence under 254 nm UV irradiation were prepared by a simple coprecipitation method in a one-pot reaction. The residual concentration of the Zn2+ ion in the filtrate can be lower than the standard of effluent 3.5 ppm in Taiwan under a pH of 8–11. Distinct from the typical phosphors with a crystal structure, porous and amorphous Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphor could have a high potential for applications in the adsorption and detection of toxic ions. This study found that the S2– ions react with Zn2+ ions in the amorphous Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphor, forming crystalline ZnS. This novel structural transformation causes a subsequent decrease in luminescent intensity. The sulfide-phosphor structural transformation mechanism could be applied for highly selective and sensitive sulfide detection tests. In addition, the effects of the phosphors’ pH value, calcination condition, and the Eu3+-dopant content and dispersity on the luminescence intensity, porosity, and crystallinity were systematically studied. To demonstrate the advantages in detecting the mesoporous Eu3+-doped zinc/silicates, CLOD, quenching constant (KSV), and renewability were then explored in sulfide-ion detection tests.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Preparation of Eu3+-Doped Zinc/Silicate Phosphors

All chemicals were used without further purification. The Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors were prepared via a simple coprecipitation method. In a typical synthetic process, 2.26 g of ZnSO4 (99.5%, Acros) and 2.36 g of sodium silicate (27% aqueous solution, Sigma-Aldrich) were dissolved separately in 100.0 and 20.0 mL of water. 5.0 mL of 0.0295 M EuCl3 (99.99%, Acros) aqueous solution was added to the ZnSO4 solution, and the pH value was adjusted to 1.0 using 0.6 M H2SO4(aq). Under acidic conditions (pH 1.0), the precipitation of the Zn2+ and Eu3+ ions can be avoided, and the silicate condensation rate is slow. After forming a stable solution of these ions, a slow neutralization induces a homogeneous co-condensation of all composites that makes it easier to obtain the desired product. The sodium silicate solution was then added to the Zn2+/Eu3+ acidic solution, and the final pH value was adjusted to 8.0–12.0 using 2.0 M NaOH(aq). After stirring at 40 °C for 2 h, the resulting gel solution was hydrothermally treated at 100 °C for 24 h. The resulting precipitate was filtered, dried, and then calcinated at 400–700 °C for 3 h to obtain the final Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate powder. The Zn/Si molar ratio of the Eu3+-doped zinc/silicates is around 0.8.

2.2. Characterization and Quenching Performance of the Eu3+-Doped Zinc/Silicate Phosphors

The XRD patterns of the various samples were taken with an X–ray diffractometer (XRD-7000S, Shimadzuu) using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15374 nm) operating at 40 kV and 20 mA. The ATR-IR spectra were recorded using a Bruker ALPHA spectrometer. The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and BET surface area were measured using a Micromeritics TriStar II volumetric adsorption analyzer. The phosphors’ structure and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy were characterized through high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) acquired at 200 kV using a JEOL JEM2100F. Luminescence measurements were performed using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Hitachi F-4500 FL) with excitation and emission slit widths of 2.5 and 5.0 nm, respectively. In performing the measurements, the voltage of the photomultiplier tube was set as 700 V, and the scan speed was selected as 1200 nm min–1. Luminescence measurements were obtained for Na2S solutions at 0–10 ppm concentrations. For each solution, the Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors were allowed to interact with the sulfide ions for 20 min, and the luminescence spectra were then obtained at the maximum excitation and emission wavelengths of 254 and 612 nm, respectively. Each data point in the spectrum is generated by taking at least two sample measurements. Each sample’s size is repeated five times to ensure accuracy and reduce variability. The final reported value for each data point is the average of these measurements. The error in the measurements is below 5%.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of the pH Condition on the Preparation of Phosphors

The pH values of the reaction solutions fundamentally affect the precipitation rate of the zinc hydroxide, the condensation rate of the silica precursors, and the crystallinity and metal-ion dispersion of the products.23−26 Thus, in the present study, the pH value used in synthesizing the phosphor was varied in the range of pH 8–12 to examine the effects of the pH value on the crystallinity, porosity, and luminescence intensity of the resulting products. As shown in Figure 1A, all of the products had an amorphous zinc/silicate structure. FT-IR spectra were further acquired, as shown in Figure 1B. The results revealed that all samples demonstrate a characteristic peak associated with Zn–O–Si stretching at a wavenumber of 1010 cm–1. The typical peak of Si–O–Si alone occurs at a wavenumber of 1120 cm–1.27 Thus, the FT-IR spectra indicate that a homogeneous mutual bonding between the Zn2+ ions and silicates can occur at a pH range of 8–12.

Figure 1.

(A) XRD patterns, (B) IR spectra, (C) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, and (D) luminescence spectra of Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors synthesized at pH (I) 8.0, (II) 9.0, (III) 10.0, (IV) 11.0, and (V) 12.0 after calcination at 500 °C (Eu3+/Zn2+ molar ratio: 1.9 × 10–2).

The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms (Figure 1C) of the Eu3+-doped zinc/silicates are all type IV isotherms with an H1-type hysteresis loop, indicating the presence of a mesoporous structure. The specific surface areas of the zinc/silicates lay in the range of 52–164 m2g–1 following calcination at 500 °C. The sample synthesized at pH 10 has the highest specific surface area of 164 m2g–1. The luminescence intensity of the phosphors was measured as shown in Figure 1D. All of the Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors showed a maximum red luminescence intensity at a wavelength of 612 nm under UV excitation at a wavelength of 254 nm. Eu3+ ions are known for their distinctive emission features in the visible range due to electronic transitions between different energy levels. Eu3+ ions exhibit several 5D0 → 7FJ transitions, each corresponding to a different final state. In this study, the 5D0 → 7F1 transition emits orange-red light at approximately 590 nm, and the 5D0 → 7F2 transition results in reddish-orange emission at about 612 nm transitions were observed.20 For pH values of 8–11, the peak intensity of the luminescence at 612 nm is almost the same, as shown in Figure 1D. In contrast, the peak intensity was significantly reduced for the phosphors synthesized at pH 12.0. Among all the phosphors, the sample synthesized at pH 10.0 demonstrates the strongest luminescence intensity. The low luminescence intensity of the phosphors synthesized at high pH values of 11 and 12 may be attributed to ZnO being an amphoteric material.28 Thus, some Zn2+ ions are dissolved under high pH conditions. It is noted that this assertion is consistent with the results presented in Table S1, which show a higher Zn2+ ion concentration in the filtrate for the phosphors synthesized at pH of 11 and 12. As the Zn content of the zinc/silicates reduces, the change in the structure of the main lattice results in a lower energy transfer efficiency, and hence the luminescence intensity decreases. For the phosphor prepared at pH 10, the residual filtrate has a Zn2+ ion content of less than 1.0 ppm (effluent standard in Taiwan) and is thus consistent with the 3.5 ppm wastewater standard in Taiwan.17 In brief, we have provided an environmentally friendly method to prepare the Eu3+-doped zinc/silicates with high specific surface area and luminescence intensity of all the prepared phosphors. Because of the highest surface area, luminescence intensity, and environmental friendliness, pH 10 was used to study other synthesis factors.

3.2. Effects of Calcination Temperature on Luminescence Intensity and Crystallinity of the Eu3+-Doped Zinc/Silicate Phosphors

It is known that the amorphous Eu3+-doped zinc/silicates readily transform to Eu3+-doped Zn2SiO4 and also improved the overall crystallinity and luminescence intensity after high-temperature calcination.29 Thus, in the present study, the synthesized Eu3+-zinc/silicate composites were calcinated at various temperatures of 400–700 °C to clarify the effect of the calcination temperature on the crystallinity, surface area, and luminescence intensity of the resulted phosphors. As shown in Figure 2A, the Eu3+-zinc/silicates had an amorphous structure prior to calcination. For calcination temperatures of 400–600 °C, the amorphous structure was retained; however, the specific surface area reduced from 151 to 40 m2g–1 (as shown in Table 1 and Figure S1), while the luminescence intensity increased from 914 to 1735 au (Figure 2B and Table 1). At calcination temperatures higher than 700 °C, the phosphors exhibited the Zn2SiO4 crystal structure, and the representative XRD peaks of the Zn2SiO4 (Willemite) were observed. The increase of the crystallinity in the phosphors leads to a significant reduction in the specific surface area (0.33 m2g–1) with a high luminescence intensity (2200 au) (Figure 2B and Table 1). Here, the luminescence properties of the Eu3+-doped zinc/silicates were observed under UV lamps with emission wavelengths of 254 and 365 nm, respectively. Figure S2 shows the observation results obtained under the two illumination wavelengths for the samples prepared without calcination and with calcination at different temperatures. However, the luminescence intensity is strongly enhanced under a shorter wavelength of 254 nm and increases with increased calcination temperature.

Figure 2.

(A) XRD patterns and (B) luminescence spectra of Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors synthesized at calcination temperatures of (I) 400 °C, (II) 500 °C, (III) 600 °C, and (IV) 700 °C (pH: 10.0, Eu3+/Zn2+ molar ratio: 1.9 × 10–2).

Table 1. Physical Properties of Phosphors Prepared with Different Calcination Temperatures.

| temperature/°C | phosphor intensity | structure | surface area/m2g–1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | 279 | amorphous | 210 |

| 400 | 914 | amorphous | 151 |

| 500 | 1569 | amorphous | 143 |

| 600 | 1735 | amorphous | 40 |

| 700 | 2200 | Willemite | 0.33 |

To examine the dispersity of the activator ions Eu3+, HR-TEM images (Figure 3) of the Si, Zn, and Eu elements in the Eu3+-doped zinc/silicates with a Eu3+/Zn2+ molar ratio of 1.9 × 10–2 under 500 °C calcination are almost the same. This result indicates that the Zn2+, silicate, and Eu3+ activator ions are homogeneously dispersed in the zinc/silicate matrix. Due to good dispersion and high surface area, this novel Eu3+-doped zinc/silicates demonstrate high luminescence intensity of the Eu3+ activator ions.

Figure 3.

HR-TEM image of Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors synthesized with a Eu3+/Zn2+ molar ratio of 1.9 × 10–2 under 500 °C calcination.

3.3. Effect of Structure on Sulfide Ion Detection Sensitivity of Eu3+-Doped Zinc/Silicate Phosphors

To study the structural effect on the Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors for sulfide ion detection, the luminescence quenching behaviors were explored at different S2– ion concentrations. The phosphors calcined at 500 and 700 °C have amorphous and Willemite structures, respectively. At higher calcination temperatures, the phosphor with Willemite structure exhibits higher luminescence intensity than that of the amorphous structure (Figure 4A). After immersion in different sulfide ion concentrations for the evaluation of the quenching effect of the luminescence, it was reasonably assumed that the luminescence intensity of the immersed phosphors was proportional to the unquenched phosphor content. Thus, the S2– detection sensitivity was defined as α = (I0 – I)/I0, where I0 is the luminescence intensity in deionized (DI) water, and I is the quenched luminescence intensity.30 Interestingly, the α value of the sample calcinated at 500 °C (α value = 0.6–0.95) was all higher than that of the sample prepared after 700 °C-calcination (α value = 0–0.15) (Figure 4B). Further detailed measurements were conducted on the sample calcinated at 500 °C, focusing on the luminescence intensity after soaking in sulfide ions solution at concentrations ranging from 0 to 50 ppm (Figure S3). Notably, the luminescence intensity gradually decreased within the 0 to 10 ppm range. At [S2–] ≈ 10 ppm, the residual luminescence is only about 20% of the I0 (with an α value of around 0.8). As the sulfide ion concentration increased to 50 ppm, the luminescence was almost quenched (I ≈ 0), with the α value approaching 1.0. To understand this novel luminescence-quench of the amorphous phosphors by S2– ion, XRD measurements were conducted on the phosphors after immersion in different [S2–] solutions (Figure 4C). In the presence of sulfide ions at a concentration higher than 10 ppm, a noticeable crystalline ZnS structure was observed. As the [S2–] increases, the crystallinity of the ZnS structure increases. The result confirms that the Zn2+ sites in the amorphous phosphor can react with sulfide ions to transform into the crystal ZnS structure and significantly decrease luminescence intensity. This novel amorphous → crystal structural transformation causes luminescence quenching and is still required for further study. In contrast, the Willemite crystal structure of the 700 °C-calcined Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate remained even at high [S2–] concentrations and had low decay in luminescence intensity. Based on this S2–-induced structural transformation and obvious quenching on the luminescent, we would like to use the amorphous Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors to develop a fast detector toward S2– ion. In addition, when the phosphor is used for S2– ion detection, the criteria for the phosphor include high luminescence intensity and amorphous structure to achieve ZnS formation for improving detection sensitivity.

Figure 4.

(A) Luminescence spectra and (B) S2– detection sensitivity of synthesized phosphors at calcination temperatures of (I) 500 °C and (II) 700 °C. (C) XRD patterns of the phosphor at a calcination temperature of 500 °C after testing under different S2– concentrations of (i) 0 ppm, (ii) 10 ppm, (iii) 100 ppm, and (iv) 250 ppm.

3.4. Eu3+ Content on Luminescence Intensity of the Eu3+-Doped Zinc/Silicate Phosphors

In addition to the calcination temperature, the amount of activator ions Eu3+ doped to the zinc/silicates also affects the luminescence intensity. As the Eu3+/Zn2+ ratio in the phosphor increases, the overall fluorescence intensity also increases. However, when the ratio increases to a specific value, there is a quenching effect due to the high Eu3+ concentration, leading to a decreasing trend in overall fluorescence intensity. For improving the detection sensitivity of the S2– ions, further synthesis of the Eu3+-doped zinc/silicates was performed using a calcination temperature of 500 °C and the Eu3+/Zn2+ molar ratios in the range of 3.7 × 10–3–5.5 × 10–2. The XRD pattern of the sample synthesized with the lowest Eu3+/Zn2+ molar ratio of 3.7 × 10–3 showed a peak corresponding to the zinc-Stevensite crystalline phase. However, all of the other samples showed an amorphous structure (Figure 5A). The existence of this amorphous structure results from the significant size difference between the Eu3+ and Zn2+ ions (i.e., 0.095 and 0.074 nm, respectively), which leads to a significant lattice mismatch or crystal distortion. As the Eu3+/Zn2+ molar ratio increases beyond 3.7 × 10–3, the lattice distortion effect and unpacked crystal structure become significant, and hence, the zinc-Stevensite phase transforms into the amorphous structure. The overall luminescence intensity of the phosphors increased significantly as the Eu3+/Zn2+ ratio increased from 3.7 × 10–3 to 3.7 × 10–2 (Figure 5B,C). However, the luminescence intensity reduced slightly as the Eu3+/Zn2+ ratio was further increased to 5.5 × 10–2 due to a concentration quenching effect.31 The Eu3+/Zn2+ molar ratios of 3.7 × 10–2 in the phosphors show the highest luminescence intensity. Although the experimental results showed a slightly higher α value for the Eu3+/Zn2+ ratio of 3.7 × 10–2 compared to the other two ratios, its performance in quenching sulfides within the typical wastewater standard range of 1.0 ppm showed no significant difference compared to samples with lower Eu3+ ratios. Furthermore, if the material is to be synthesized in large quantities to meet industrial demands, a higher Eu3+ ratio would incur more significant raw material costs. Therefore, a Eu3+/Zn2+ ratio of 1.9 × 10–2 was selected as the optimal ratio.

Figure 5.

(A) XRD patterns, (B) luminescence spectra, and (C) luminescence intensity of Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors synthesized with Eu3+/Zn2+ molar ratios of (I) 3.7 × 10–3, (II) 1.9 × 10–2, (III) 2.9 × 10–2, (IV) 3.7 × 10–2, and (V) 5.5 × 10–2 (pH: 10.0).

3.5. Selectivity in the Sulfide Ion Detection

Industrial wastewater usually contains many complex anions, and the composition of these ions varies greatly depending on the application. Thus, in addition to a good adsorption performance and high stability, effective detection adsorbents should also have high ion selectivity. Accordingly, the luminescence quenching reaction of the Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors was evaluated for simulated wastewater samples containing different anions with a concentration of 1.0 ppm and a neutral environment (pH 7). As shown in Figure 6, the luminescence intensity of the phosphors reduced by around 30% following the reaction with the sulfide ions compared to that in a pure DI water sample. However, the luminescence intensity showed virtually no change when exposed to other ions. Thus, the high selectivity of the Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors for sulfide ions in wastewater was confirmed. In the presence of different anions, it was observed that only sulfide ions could react with the amorphous Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors, leading to a significant change in luminescence intensity. This result indicates that the amorphous phosphors used in this study exhibit excellent selectivity for sulfide ion detection.

Figure 6.

Selectivity of Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors for luminescence quenching with different anions (pH 7.0/concentration: 1.0 ppm).

3.6. Sulfide Ion Detection Limit (CLOD) of Eu3+-Doped Zinc Silicates

Distinct from the typical phosphors with low surface areas and rigid crystal structures, amorphous phosphors with large surface areas and flexible structures could be used for adsorption and detection applications. In this study, the CLOD of the amorphous Eu3+dopped zinc/silicate phosphors with high surface area was derived from the standard deviation of five sets of blank analysis noise by tripling the slope of the calibration curve (99.7% confidence level), i.e.,

where Ysample is the sample’s peak intensity, Yblank is the peak intensity of the blank sample (DI water), m is the slope of the calibration curve, and C is the S2– concentration.

The detection limit was calculated as CLOD = [(t × S) ÷ m] where t = 3 under a 99.7% confidence level, and S is the standard deviation. The detection limit of the zinc/silicate phosphors was evaluated over the sulfide ion concentration range of 0–0.8 ppm. The luminescence intensities for sulfide concentrations of 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 ppm were 1990, 1756, 1571, 1287, and 1151 au, respectively. The individual luminescence intensity values were subtracted from the blank signal intensity (for which the luminescence intensity was not quenched). The resulting absolute value was plotted along the Y-axis against the corresponding sulfide ion concentration along the X-axis. The calibration equation thus obtained was found to be Y = 1329X, with a correlation coefficient of R2 = 0.9902 (Figure 7). After getting the value of m, the standard deviation (S = 2.46) of the five sets of blank analysis noise (93.26, 96.02, 95.43, 90.25, and 91.56 au) was calculated, and a CLOD value of 1.8 × 10–7 M was obtained by tripling the slope of the line (m = 1329).

Figure 7.

Luminescence intensity of Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors for different S2– concentrations (0.0–0.8 ppm).

The deactivation behavior of the zinc/silicates in the presence of different S2– concentrations was further evaluated using the Stern–Volmer equation, I0/I = KSV[C]+1, where I0 is the initial luminescence intensity of the phosphors in DI water, I is the luminescence intensity of the phosphors in the presence of sulfide ion, and [C] is the sulfide ion concentration. Furthermore, KSV is the luminescence quenching constant, where a higher value indicates a greater sensitivity of the phosphors to the quenching agent. The luminescence intensity measurements at different Na2S concentrations over the range of 0–1.0 ppm were substituted into the Stern–Volmer equation. They were found to yield a linear relation (Figure 8). The regression analysis results showed that the intensity (Y) and concentration (X) were related as Y = 0.9434X+1. The quenching constant, KSV, was thus determined to be 3.1 × 104 M–1. It is noted that this value is higher than the typical KSV value obtained in conventional optical detection methods based on methylene blue, i.e., 1.4 × 103 M–1.16

Figure 8.

Stern–Volmer equation for luminescence quenching reaction of Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors at different S2– ion concentrations (0.0–1.0 ppm).

3.7. Renewability of Eu3+-Doped Zinc Silicate Phosphors

In keeping with the principles of green chemistry, reusing the Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors following the sulfide ion detection process is desirable. Accordingly, the renewability of the phosphors was evaluated by calcinating the absorbents at a temperature of 500 °C for 3 h. The phosphors retained an amorphous structure after the removal of the S2– (Figure 9A). In addition, no ZnS characteristic peaks were observed in either XRD pattern due to the low concentration of Na2S(aq) (1.0 ppm). The phosphor retained an amorphous structure after regeneration. However, the specific surface area reduced from 136 to 108 m2g–1 (Figure 9B). The luminescence intensities of the phosphors were measured before and after adsorption of S2–, respectively, and following regeneration. The raw phosphor showed a luminescence intensity of 1773 au (Figure 9C). Following the adsorption of S2–, the luminescence intensity reduced to 1008 au (a reduction of approximately 43.1%). However, after calcination at 500 °C, the luminescence intensity was restored to 1482 au (approximately 83.6% of the original intensity). In addition, the Stern–Volmer equation showed a linear relationship between the quenching effect of the regenerated phosphors and the Na2S(aq) concentration over the range of 0.1–1.0 ppm (Figure 9D). Notably, the quenching constant (KSV) of the regenerated phosphors was calculated to be 1.4 × 104 M–1. Table 2 compares the CLOD and KSV performance of the present Eu3+-doped zinc/silicates with those of a conventional methylene blue optical detection method and several other sulfide ion detection methods reported in the literature.15,19,30−34 The results confirm that the amorphous Eu3+-doped zinc/silicates have a better CLOD and KSV performance than the methylene blue detection method and generally outperform all related methods.

Figure 9.

(A) XRD patterns, (B) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, and (C) luminescence spectra of (I) raw phosphor, (II) phosphor quenched with S2–, and (III) regenerated phosphor. (D) Stern–Volmer equation for luminescence quenching reaction of regenerated phosphor for different S2– concentrations (0.0–1.0 ppm).

Table 2. Sulfide Detection Ability of Present Eu3+-Doped Zinc/Silicate Phosphors and Other Phosphors Reported in the Literature.

| materials | limit of detection/M | KSV/ M–1 | references |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate | 1.8 × 10–7 | 3.1 × 104 | present study |

| methylene blue | 1.6 × 10–6 | 1.4 × 103 | (15) |

| ZnO/SiO2 nanocomposite | 1.3 × 10–6 | (19) | |

| Eu3+@Bio-MOF-1 | 1.1–6.8 × 10–7 | (30) | |

| cyclen-appended BINOL derivative | 1.6 × 10–5 | (32) | |

| MoS2 nanosheets | 4.2 × 10–7 | (33) | |

| SiO2@Eu-dpa | 2.9 × 104 | (34) |

4. Conclusions

This study has synthesized the amorphous Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors with a high luminescence intensity, high specific surface area (>100 m2g–1), high selectivity for S2– ions, and good renewability through a simple one-pot coprecipitation method. The synthesized amorphous phosphors have been successfully applied to determine sulfide ions in water. The results have shown that the limit of detection (CLOD = 1.8 × 10–7 M) and quenching constant (KSV = 3.1 × 104 M–1) of the synthesized phosphors are higher than those of a conventional methylene blue optical detection method (i.e., 1.6 × 10–6 and 1.4 × 103 M–1, respectively). Furthermore, the phosphors can be regenerated through a simple calcination process at 500 °C for 3 h. The results show that the proposed coprecipitation method provides an efficient and environmentally friendly approach for preparing other mesoporous silicate-base phosphors with amorphous structures to detect different pollutants. In addition, this study has developed a novel detection method for sulfide ions based on the apparent quenching in luminescence intensity by structural transformation. This approach holds potential for future applications in various detection systems toward different analytes.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, for financial support of the present research. The authors gratefully acknowledge using JEOL JEM-2100F Cs STEM of NSTC 111-2731-M-006-001 belonging to the Core Facility Center of National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.3c06823.

Residual concentration of zinc ions in the filtrate of phosphors synthesized at different pH values; N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of Eu3+-doped zinc/silicate phosphors synthesized at different calcination temperatures; photographs of phosphors regenerated using different calcination temperatures under UV irradiation; and luminescence spectra for phosphor calcination at 500 °C (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Liu Y. C.; Teng L. L.; Yin B. L.; Meng H. M.; Yin X.; Huan S. Y.; Song G. S.; Zhang X. B. Chemical design of activatable photoacoustic probes for precise biomedical applications. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 6850–6918. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S.; Sharma S. Temperature-based selective detection of hydrogen sulfide and ethanol with MoS2/WO3 composite. ACS Omega 2022, 7 (7), 6075. 10.1021/acsomega.1c06471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu F. D.; Zhang S. D.; Huang C. Z.; Guo X. Y.; Zhu Y.; Thomas T.; Guo H. C.; Attfield J. P.; Yang M. H. Surface functionalized sensors for humidity-independent gas detection. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 6561–6566. 10.1002/anie.202015856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Zhang S. Q.; Lu Y.; Zhang J. Y.; Zhang X.; Wang R. Z.; Huang J. Highly selective and sensitive detection of volatile sulfur compounds by ionically conductive metal-organic frameworks. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2104120 10.1002/adma.202104120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. J.; Huang B. C.; Yu C. L.; Lu M. J.; Huang H.; Zhou Y. L. Research progress, challenges, and perspectives on the sulfur and water resistance of catalysts for low-temperature selective catalytic reduction of NOx by NH3. Appl. Catal., A 2019, 588, 117207 10.1016/j.apcata.2019.117207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar U. C.; Alhooshani K. R.; Adamu S.; Al Thagfi J.; Saleh T. A. The effect of calcination temperature on the activity of hydrodesulfurization catalysts supported on mesoporous activated carbon. J. Cleaner Prod. 2019, 211, 1567–1575. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saidur R.; Abdelaziz E. A.; Demirbas A.; Hossain M. S.; Mekhilef S. A review on biomass as a fuel for boilers. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2262–2289. 10.1016/j.rser.2011.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L. L.; Sedgwick A. C.; Sun X. L.; Bull S. D.; He X. P.; James T. D. Reaction-based fluorescent probes for the detection and imaging of reactive oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur species. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 2582–2597. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei P.; Xiao L.; Gou Y.; He F.; Wang P.; Yang X.; Yue Z.; Lisdat F.; Parak W. J.; Hickey S. G.; Tu L. P.; Sabir N.; Dorfs D.; Bigall N. C. A novel peptide-based relay fluorescent probe with a large Stokes shift for detection of Hg2+ and S2– in 100% aqueous medium and living cells: Visual detection via test strips and smartphone. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2023, 285, 121836 10.1016/j.saa.2022.121836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H.; Jin X.; Zhou H.; Yang Z.; Bai H.; Yang J.; Li Y.; Ma Y.; She M. Fabrication of carbon dots for sequential on–off-on determination of Fe3+ and S2– in solid-phase sensing and anti-counterfeit printing. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 7473–7483. 10.1007/s00216-021-03709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hine C.; Mitchell J. R. Endpoint or kinetic measurement of hydrogen sulfide production capacity in tissue extracts. Bio-Protoc. 2017, 7, e2382 10.21769/BioProtoc.2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X.; Mutus B. Electrochemical detection of sulfide. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2013, 32, 247–256. 10.1515/revac-2013-0008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duc C.; Boukhenane M. L.; Wojkiewicz J. L.; Redon N. Hydrogen sulfide detection by sensors based on conductive polymers: A review. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 215. 10.3389/fmats.2020.00215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y.; Li G.; Wu D.; Zheng F.; Zhang X.; Liu J.; Hu N.; Wang H.; Wu Y. Determination of hydrogen sulfide in wines based on chemical-derivatization-triggered aggregation-induced emission by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 876–883. 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b04454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moest R. Hydrogen sulfide determination by the methylene blue method. Anal. Chem. 1975, 47, 1204–1205. 10.1021/ac60357a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gore A. H.; Vatre S. B.; Anbhule P. V.; Han S.-H.; Patil S. R.; Kolekar G. B. Direct detection of sulfide ions [S2–] in aqueous media based on fluorescence quenching of functionalized CdS QDs at trace levels: analytical applications to environmental analysis. Analyst 2013, 138, 1329–1333. 10.1039/c3an36825d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syu J. H.; Cheng Y. K.; Hong W. Y.; Wang H. P.; Lin Y. C.; Meng H. F.; Zan H. W.; Horng S. F.; Chang G. F.; Hung C. H.; Chiu Y. C.; Chen W. C.; Tsai M. J.; Cheng H. Electrospun fibers as a solid-state real-time zinc ion sensor with high sensitivity and cell medium compatibility. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 1566–1574. 10.1002/adfm.201201242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y. B.; Lu J.; Zhou Y.; Liu Y. D. Recent advances for dyes removal using novel adsorbents: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 352–365. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N.; Zhou T.; Wang J.; Yuan H.; Xiao D. Sulfide sensor based on the room-temperature phosphorescence of ZnO/SiO2 nanocomposite. Analyst 2010, 135, 2386–2393. 10.1039/c0an00081g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaafar S. H.; Zaid M. H. M.; Matori K. A.; Aziz S. H. A.; Mohamed Kamari H.; Honda S.; Iwamoto Y. Influence of calcination temperature on crystal growth and optical characteristics of Eu3+ doped ZnO/Zn2SiO4 composites fabricated via simple thermal treatment method. Crystals 2021, 11, 115. 10.3390/cryst11020115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blasse G.; Grabmaier B., A general introduction to luminescent materials. In Luminescent materials; Springer: 1994; pp 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Montes D.; Tocuyo E.; González E.; Rodríguez D.; Solano R.; Atencio R.; Ramos M. A.; Moronta A. Reactive H2S chemisorption on mesoporous silica molecular sieve-supported CuO or ZnO. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 168, 111–120. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2012.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nasi L.; Calestani D.; Besagni T.; Ferro P.; Fabbri F.; Licci F.; Mosca R. ZnS and ZnO nanosheets from ZnS(en)0.5 precursor: nanoscale structure and photocatalytic properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 6960–6965. 10.1021/jp2112439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toyama S.; Takesue M.; Aida T. M.; Watanabe M.; Smith R. L. Jr. Easy emission-color-control of Mn-doped zinc silicate phosphor by use of pH and supercritical water conditions. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2015, 98, 65–69. 10.1016/j.supflu.2015.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. Y.; Chang Y. C.; Hung W. Y.; Lin H. P.; Shih H. Y.; Xie W. A.; Li S. N.; Hsu C. H. Green synthesis of porous Ni-silicate catalyst for hydrogen generation via ammonia decomposition. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 9748–9756. 10.1002/er.5641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J. H.; Bai Y. Q.; Wang Q. Reconstruction of colloidal spheres by targeted etching: A generalized self-template route to porous amphoteric metal oxide hollow spheres. Langmuir 2015, 31, 4566–4572. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b00638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R.; King A.; Nayak B. B. Influence of calcination temperature on phase, powder morphology and photoluminescence characteristics of Eu-doped ZnO nanophosphors prepared using sodium borohydride. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 847, 156382 10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.156382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Sun J.; Zhang W. H.; Ma X. X.; Lv J. Z.; Tang B. A near-infrared ratiometric fluorescent probe for rapid and highly sensitive imaging of endogenous hydrogen sulfide in living cells. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 2551–2556. 10.1039/c3sc50369k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu G.; Han Y.; Zhu X.; Gong J.; Luo T.; Zhao C.; Liu J.; Liu J.; Li X. Sensitive detection of sulfide ion based on fluorescent ionic liquid-graphene quantum dots nanocomposite. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 658045 10.3389/fchem.2021.658045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng H.; Yan B. A. Eu (III) doped metal-organic framework conjugated with fluorescein-labeled single-stranded DNA for detection of Cu (II) and sulfide. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 988, 89–95. 10.1016/j.aca.2017.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.; Tang B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission luminogens for activity-based sensing. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 2559–2570. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M. Q.; Li K.; Hou J. T.; Wu M. Y.; Huang Z.; Yu X. Q. BINOL-based fluorescent sensor for recognition of Cu (II) and sulfide anion in water. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 8350–8354. 10.1021/jo301196m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Hu J.; Zhuang Q.; Ni Y. Label-free fluorescence sensing of lead (II) ions and sulfide ions based on luminescent molybdenum disulfide nanosheets. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 2535–2541. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b01639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lian X.; Yan B. Novel core–shell structure microspheres based on lanthanide complexes for white-light emission and fluorescence sensing. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 2666–2673. 10.1039/C5DT03939H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.