Abstract

Negative, destructive, and abusive behaviors in romantic relationships can vary from explicit kinds of abuse and aggression to more subtle and seemingly innocuous slights against or ways of treating a partner. However, regardless of the severity or explicit nature, these behaviors all, to one extent or another, reflect acts of invalidation, disrespect, aggression, or neglect toward a partner, and could be considered maltreatment of a partner. The current paper proposes the term partner maltreatment as a broad overarching concept, which was used to facilitate a meta-analytic synthesis of the literature to examine the associations between attachment insecurity (i.e., attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance) and perpetration of partner maltreatment. Additionally, this paper situated partner maltreatment within an attachment-based diathesis-stress perspective to explore the moderating role of stress. Five databases were systematically searched for published and unpublished studies that examined the direct association between perpetrator’s adult attachment orientation and perpetration of partner maltreatment behaviors. We synthesized effect sizes from 139 studies (N = 38,472) and found the effect between attachment insecurity and acts of partner maltreatment varied between r = .11 to .21. Our findings provide meta-analytic evidence to suggest that attachment insecurity is a significant individual vulnerability factor (diathesis) associated with partner maltreatment; and that when individuals with an insecure attachment orientation experience stress, the tendency to perpetrate partner maltreatment is typically heightened. The findings of this meta-analysis provide empirical evidence for the importance of considering and addressing contextual factors, especially stress, for those individuals and couples seeking therapy for partner maltreatment.

Keywords: partner maltreatment, attachment theory, stress, romantic relationships, diathesis-stress

Over the last two decades, the perpetration of destructive and abusive behaviors in romantic relationships has been the source of much investigation. Throughout this period, there has been significant attention focused on understanding the role of individual differences as critical impellors that heighten peoples’ tendencies to maltreat romantic partners (Finkel & Eckhardt, 2013). One of the most widely studied individual difference variables is attachment orientations (i.e., chronic patterns of cognition, affect, and behavior in close relationships; Gillath et al., 2016; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016; Simpson & Rholes, 2012). The interest in the study of attachment orientations is largely due to the rich interpersonal dynamics described as part of the normative and individual difference components of human bonding within attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969, 1982; Cassidy & Shaver, 2002; Gillath et al., 2016; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016; Simpson & Rholes, 2012). According to attachment theory, deviations from modal (species-typical) attachment processes manifest in the form of insecure attachment orientations (Simpson & Karantzas, 2019)—namely—attachment anxiety (i.e., chronic need for approval, preoccupation with relationships) and attachment avoidance (i.e., discomfort with closeness, chronic distrust of others; Brennan et al., 1998; Fraley & Waller, 1998; Gillath et al., 2016). Thus, associations between attachment insecurity and negative, destructive as well as abusive relationship behaviors are thought to reflect manifestations of the chronic concerns and worries that underpin insecure attachment orientations (Gillath et al., 2016; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016).

Despite the large number of studies that have investigated the associations between attachment orientations and negative, destructive, and abusive behaviors, there are numerous inconsistencies in the direction and magnitude of the associations reported. Additionally, research has typically focused on the most severe of destructive relationship behaviors in the form of intimate partner abuse (IPA; Velotti et al., 2018; Velotti et al., 2022). Yet, there exists a substantial body of work regarding a wide array of relationship behaviors that extend beyond IPA—but are nonetheless destructive and toxic—and in which, a systematic synthesis of the literature is absent. This absence is largely because research concerning negative, destructive, and abusive relationship behaviors has been conducted across two independent fields of research. The first is situated within the family violence sector and relates to violent, coercive controlling, and aggressive acts of IPA. The second is situated within the field of relationship science and pertains to the study of problematic conflict patterns and various other negative relationship processes (e.g., failure to supportively attend to the socio-emotional needs of a partner, acts of relationship betrayal, or breaches of partner trust).

However, when examining studies that have investigated attachment orientations and destructive or abusive acts across these two fields of research, a clear conceptual overlap emerges between the relationship behaviors studied within each field, particularly when the focus is on non-physical negative acts. For instance, it becomes difficult to disentangle aspects of psychological abuse and neglect, which are most commonly studied in the family violence sector, from corrosive relationship behaviors such as emotional withdrawal, hostility, or contempt, typically studied within relationship science. In fact, what many of the negative, destructive, and abusive relationship behaviors share across both fields of study is that these behaviors all, to one extent or another, maltreat the partner.

With this in mind, could the destructive relationship behaviors studied across the two fields of research be synthesized as part of an integrative conceptualization which captures the essential features of negative, destructive, and abusive relationship behaviors across the spectrum of severity: from the subtle and seemingly innocuous slights against one’s partner to highly explicit forms of psychological abuse and physical aggression? If so, can such a conceptualization facilitate the synthesis of the large body of research investigating the associations between attachment orientations and the many and varied negative, destructive, and abusive behaviors studied across the areas of family violence and relationship science? In this paper, we propose that such a conceptualization exists and can be used as a framework to systematically organize the literature across both fields of research. We term this construct partner maltreatment and broadly define it as any subtle or overt act of invalidation, aggression, disrespect, or neglect directed toward a partner and/or romantic relationship.

The current paper adopts the proposed broad conceptualization of partner maltreatment to systematically evaluate the associations between attachment orientations and maltreatment behaviors in romantic relationships. Additionally, the current paper acknowledges that across both the family violence and relationship science fields, the associations between attachment orientations and partner maltreatment are studied within the context of stress. This focus on stress is for two reasons. First, contemporary models of aggression and relationship functioning draw on person-by-situation frameworks to explain how stressful situations can strengthen the association between personal vulnerabilities and the tendency to maltreat (Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Finkel, 2007; Finkel & Eckhardt, 2013). Second, attachment orientations are, in part, considered to reflect individual differences in the interpersonal regulation of distress (Gillath et al., 2016; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Because insecure attachment orientations are associated with difficulties regulating distress (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2019), attachment insecurity is considered a personal vulnerability factor (i.e., diathesis) that is associated with an increase in negative interpersonal outcomes under stressful situations (Simpson & Rholes, 2012). With this in mind, a number of studies have situated the study of attachment orientations and maltreatment behaviors within a diathesis-stress framework (e.g., Karantzas & Kambouropoulos, 2019; Simpson et al., 1996; Simpson & Rholes, 2012). However, the role of stress in this association is yet to be systematically reviewed or evaluated within the literature. Therefore, we apply a diathesis-stress framework to organize the first review of the research that has investigated the associations between attachment orientations and partner maltreatment and highlight the moderating role of stress.

Partner Maltreatment

We broadly define partner maltreatment as any subtle or overt act of invalidation, disrespect, aggression, or neglect of a romantic partner and/or the romantic relationship. Empirical work across disciplines has identified a diverse array of destructive and abusive relationship behaviors, which can manifest in a myriad of ways. However, we suggest that acts of maltreatment involve the use of cognitive and behavioral tactics which undermine, coerce, dismiss, control, or belittle the partner in order to attain one’s own needs or goals over and above consideration of the partner’s needs or goals. Hence, perpetration of partner maltreatment often demonstrates a clear lack of care, concern, or regard for a partner.

The wide array of negative relationship behaviors that can be included as part of this broad definition can be organized into three related, yet distinct, dimensions of behavior. These behaviors are (1) IPA, (2) destructive conflict patterns, and (3) corrosive relationship behaviors. Nested within each of these dimensions of partner maltreatment are facets of maltreatment behaviors which are outlined in Table S1 of the Supplement Material. The proposed broad dimensions of partner maltreatment behavior are not mutually exclusive from one another. Rather, the proposed behavioral dimensions assumed to underpin partner maltreatment can co-vary such that individuals can simultaneously exhibit more than one dimension of maltreatment behavior.

Nevertheless, while these three behavioral dimensions are related, they are distinct. For example, behaviors which are classified as IPA are coercive and frightening and are used to exert dominance and control over a partner. Whereas behaviors that are classified as either destructive conflict patterns or corrosive relationship behaviors do not incite fear for one’s physical safety and, therefore, remain distinct from IPA behavior. Furthermore, destructive conflict behaviors and corrosive relationship behaviors differ from one another in important ways. Destructive conflict patterns reflect various avoidance and escalating strategies couples enact during a conflict interaction. In contrast, corrosive relationship behaviors reflect acts that generally foster a dysfunctional relationship climate. These behaviors occur outside of a conflict interaction and capture many negative acts such as relationship betrayals, making unrealistic demands of relationship partners, responding insensitively to the needs of a partner, to name but a few. We expand further on each of these behavioral dimensions in the subsections below.

Behavioral Dimensions of Partner Maltreatment

IPA captures violent, aggressive, coercive controlling, and harmful behaviors that are deliberately used to incite fear, erode the partner’s sense of self-worth and autonomy, and/or exert control and power over the partner (Johnson, 2010; Stark, 2007; Stark & Hester, 2019). As shown in Table S1 (see Supplement Material), such behaviors can include physical violence, sexual coercion, psychological aggression (including coercive control), and stalking. There are countless ways someone can engage in physical or psychological harm against a romantic partner; however, a defining feature of this dimension of partner maltreatment is the use of severe and intentional physical and/or psychological force and dominance to harm, control, entrap, and/or subjugate a partner.

Destructive conflict patterns encompass a range of invalidating and disrespectful behaviors that occur specifically within the context of conflict between relationship partners. These patterns of conflict behavior can include destructive engagement or conflict avoidance (e.g., Feeney & Karantzas, 2017). Destructive engagement refers to dominating, manipulative, and confrontational behaviors that escalate and perpetuate conflict. Conflict avoidance reflects behaviors in which an individual physically or psychologically withdraws from the conflict (see Table S1). At face value, some of the behaviors that are considered to represent destructive conflict patterns may seem to overlap with aspects of psychological aggression. However, behaviors are classified as destructive conflict patterns rather than psychological aggression when they do not evoke the kind of fear or intimidation where a partner can feel entrapped and/or physically unsafe, which is seen as a key feature of coercive control in IPA (Stark & Hester, 2019). Additionally, maltreatment behaviors nested within the destructive conflict patterns dimension are devoid of egregious abusive acts, such as violence or physical aggression. Moreover, unlike behaviors that feature across other facets of partner maltreatment, behaviors indicative of destructive conflict patterns only manifest within conflict situations; hence, there is little ongoing or pervasive display of such behaviors outside of the disagreements or discussions of relationship issues.

Finally, corrosive relationship behaviors refer to various negative behaviors and interactions between couples that generally foster a dysfunctional relationship climate. As shown in Table S1, these corrosive relationship behaviors include (1) excessive proximity maintenance—a chronic desire to remain physically or emotionally close with a partner; (2) insensitive caregiving—a lack of sensitivity or responsiveness to a partner’s needs, such that the support or care provided to a partner is either intrusive and overbearing (referred to as compulsive caregiving; Kunce & Shaver, 1994) or emotionally detached and withdrawn (i.e., distant caregiving; Kunce & Shaver, 1994); (3) manipulation—the manipulation of a partner’s emotions or thoughts to garner a partner’s attention or affection; (4) unrealistic demands—making unrealistic demands for a partner to change their behavior, make sacrifices, or maintain excessively high standards; and (5) relationship betrayals—violation of relationship norms or a partner’s trust. For behaviors nested within this dimension, it would be rare that a single act would reflect partner maltreatment; rather, it is the chronicity or consistency with which such behaviors are enacted that constitutes partner maltreatment. Although the behaviors that constitute this dimension can trigger conflict, these behaviors do not describe patterns of conflict and can occur outside of a conflict interaction. Hence, these behaviors cannot be purely categorized as destructive conflict patterns. Additionally, corrosive relationship behaviors are not regarded as IPA because these behaviors are not violent or aggressive in nature, nor do they incite fear or exercise coercive control of a partner. Therefore, although related to other behavioral dimensions of partner maltreatment, corrosive relationship behaviors do indeed warrant being considered a dimension unto itself.

Insecure Attachment Orientations and Partner Maltreatment

Within the literature that focuses on adult attachment, insecure attachment orientations are conceptualized as being underpinned by two dimensions—attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance (Brennan et al., 1998; Fraley & Waller, 1988). Attachment anxiety is characterized by an excessive need for closeness and a chronic fear of rejection in close relationships (Brennan et al., 1998; Fraley et al., 2000). On the other hand, attachment avoidance is characterized by a lack of trust in others and a desire to maintain self-reliance rather than turning to romantic partners for support (Brennan et al., 1998). Both insecure attachment orientations are associated with various negative relationship behaviors and outcomes (for a review see Gillath et al., 2016; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016; Simpson & Karantzas, 2019). Especially relevant to the current review, these negative outcomes include IPA, destructive conflict patterns, and corrosive relationship behaviors—the behavioral dimensions that we propose constitute partner maltreatment (Bartholomew & Allison, 2006; Feeney & Karantzas, 2017).

Attachment Anxiety and Partner Maltreatment

Individuals high on attachment anxiety tend to be chronically concerned that their partner might leave them, does not love them, or lacks the capacity or willingness to respond to their needs (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). As such, individuals with an anxious attachment tend to display excessive dependence and require constant reassurance from, and closeness with, romantic partners (Feeney & Karantzas, 2017). When faced with distressing situations, these individuals have difficulty self-regulating negative affect and instead tend to engage in hyperactivating strategies (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2011, 2016). These strategies involve the upward regulation of distress as well as intense and persistent attempts at seeking closeness or garnering the attention of a significant other (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). For example, when stressed, these individuals may exaggerate experiences of emotional hurt in an effort to secure their partner’s attention and care (Feeney & Karantzas, 2017; Jayamaha et al., 2016; Overall, Girme, et al., 2014). Essentially, anxiously attached individuals will use insistent, and at times, demanding, clinging, coercive, and manipulative tactics to attain proximity, support, or love from their partner (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2011).

The characteristics of hypersensitivity to rejection along with an inability to constructively regulate distress means that people high on attachment anxiety are predisposed to perpetrating an array of partner maltreatment behaviors identified within the dimensions of IPA, destructive conflict, and corrosive relationship behavior. Indeed, attachment anxiety is often found to be associated with the perpetration of IPA (e.g., Dutton & White, 2012; Follingstad et al., 2002; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2011; Roberts & Noller, 1998; Wright, 2017). Within the context of couple conflict, attachment anxiety is associated with escalating conflict behaviors, such as partner criticism, blame, coercion, contempt, and exerting dominance (Bonache et al., 2019; Crangle & Hart, 2017; Creasey, 2002; Feeney, 2017; Feeney & Fitzgerald, 2018). Outside the context of conflict, attachment anxiety is associated with various corrosive relationship behaviors, such as invading their partner’s privacy (Feeney, 1999; Lavy et al., 2013), manipulating a partner by inciting guilt in order to garner their partner’s compliance and affection (Overall et al., 2014), and insisting, intrusive, and overbearing caregiving (Brock & Lawrence, 2014).

Attachment avoidance and partner maltreatment

Individuals with an avoidant attachment orientation have learned to regulate their distress by cognitively and behaviorally disengaging with or suppressing distress when they perceive a threat; these behaviors are termed deactivating strategies (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2011). Hence, avoidantly attached individuals are likely to dismiss, downplay, distract, or completely withdraw from threats and inhibit any distress-related thoughts and feelings (Feeney, 2017; Feeney & Karantzas, 2017; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2011). Consequently, these individuals tend to be less invested in their relationships and so they strive to maintain independence from their partners (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). In fact, individuals high on attachment avoidance tend to proactively limit intimacy to avoid the pain of potential rejection (Edelstein & Shaver, 2004).

As individuals with an avoidant attachment orientation tend to downplay vulnerability or dependence, they can be predisposed to perpetrating various invalidating and neglectful maltreatment behaviors. Although associations between attachment avoidance and some aspects of partner maltreatment, such as conflict avoidance and neglect of a partner have been consistently demonstrated across studies, there have been mixed findings in the literature regarding the association between attachment avoidance and acts of IPA. Some studies have found little to no association between attachment avoidance and the perpetration of IPA (e.g., Bookwala, 2002; Henderson et al., 2005; Lawson & Malnar, 2011) and other studies have found a significant positive correlation (e.g., Barbaro & Shackelford, 2019; Frey et al., 2011; Gabbay & Lafontaine, 2017; Gormley & Lopez, 2010). Attachment theory suggests that, given their use of deactivating strategies, engaging in maltreatment behaviors such as acts of IPA would be atypical for individuals high on attachment avoidance (Bartholomew & Allison, 2006). However, research regarding a significant positive correlation between attachment avoidance and IPA has suggested individuals high on attachment avoidance may use abusive tactics to create distance from their partner (Bartholomew & Allison, 2006; Dutton & White, 2012) and may lash out aggressively when attempts to distance from their partner fail (Allison et al., 2008; Feeney, 2017; Karantzas & Kambouropoulos, 2019; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003).

Similarly, in order to maintain a sense of independence and control in the context of conflict with a partner, avoidantly attached individuals may refuse to engage in a conflict discussion, display an unwillingness to deal with their partner’s distress and needs, dismiss the importance of the issue, limit disclosure and openness, and create physical or psychological distance (Feeney & Karantzas, 2017; Nichols et al., 2015; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003, 2016). Beyond the realm of conflict, individuals high on attachment avoidance also tend to emotionally disconnect from, and neglect their partner, as well as minimize their sense of responsibility toward their romantic partner (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2003, 2016). Hence, attachment avoidance has been associated with corrosive relationship behaviors, such as distant and uninvolved provision of care and support for their partners (Braun et al., 2012; Collins & Feeney, 2000; Verhofstadt et al., 2007) and acts of infidelity (Allen & Baucom, 2004; DeWall et al., 2011).

Although insecure attachment orientations are an important individual difference variable that is associated with the perpetration of various maltreatment behaviors in romantic relationships (Bartholomew & Allison, 2006; Dutton & White, 2012; Feeney & Karantzas, 2017), it is likely that contextual factors moderate this association as not all individuals with an insecure attachment orientation will maltreat their partner. Moreover, even insecurely attached individuals that engage in maltreatment, do not enact these behaviors at all times (e.g., Karantzas & Kambouropoulos, 2019). Under what circumstances, then, would someone with an anxious or avoidant attachment orientation maltreat their partner? Given attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance are associated with differential ways of regulating distress, research has increasingly considered stress as a critical contextual moderator that may strengthen the associations between attachment insecurity and maladaptive behaviors in close relationships (Simpson & Rholes, 2012, 2017).

Attachment Insecurity, Stress, and Partner Maltreatment

Broadly, stress results from problematic or challenging situations that are perceived as having a negative, harmful, threatening, or demanding impact (Randall & Bodenmann, 2009). The experience of stress is an inevitable part of everyday life in close relationships and is a contextual factor that may contribute to, and perpetuate cycles of, maltreatment (Karantzas et al., 2017; Randall & Bodenmann, 2009, 2017). Moreover, stress is particularly relevant in the study of partner maltreatment because many of the situations within which partner maltreatment may occur (especially those pertaining to situational couple violence and other escalating cycles of conflict) are, in and of their nature, distressing. Although a direct relationship between experiencing stress and various forms of partner maltreatment has been suggested (Cano & Vivian, 2003; Neff & Karney, 2017), contemporary approaches have highlighted that stress does not sufficiently explain partner maltreatment (Eckhardt & Parrott, 2017; Karantzas et al., 2017). Rather, stress is thought to interact with existing individual vulnerability factors related to maltreatment, such as attachment insecurity. This “person-by-situation interaction” perspective aligns with the increasing application of diathesis-stress type models to understanding the genesis and maintenance of destructive relationship behaviors, including interpersonal aggression and alike (Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Finkel, 2007; Finkel & Eckhardt, 2013).

Diathesis-Stress Model

Broadly speaking, the diathesis-stress model suggests the presence of stress strengthens the relationship between a given vulnerability (i.e., a diathesis), such as attachment insecurity, and a negative outcome, such as partner maltreatment (Ingram & Luxton, 2005; Monroe & Simmons, 1991). The diathesis-stress model has guided research into the understanding of attachment insecurity as a vulnerability factor in a range of negative relationship outcomes (Simpson & Rholes, 2012, 2017). Research has applied a diathesis-stress perspective to understand the ways attachment insecurity and stress are likely to converge in the prediction of negative outcomes in close relationships (e.g., Simpson et al., 1996; Simpson & Rholes, 2012, 2017). Thus, drawing on a diathesis-stress perspective to understand the association between attachment insecurity and partner maltreatment may provide important insights into the seemingly inconsistent findings in the literature regarding the association between attachment insecurity (particularly attachment avoidance) and various maltreatment outcomes.

The Current Meta-Analysis

Drawing on our proposed conceptualization of partner maltreatment, we conducted a quantitative synthesis of the literature into the associations between adult insecure attachment orientations and partner maltreatment (at the overall level) and estimated the associations between attachment orientations and the three broad dimensions that constitute partner maltreatment—IPA, corrosive relationship behaviors, and destructive conflict patterns. Moreover, drawing on an attachment-informed diathesis-stress model, we also examine the extent to which stress moderates the associations between insecure attachment orientations and partner maltreatment at the overall level and the three primary dimensions of partner maltreatment.

We propose a series of predictions regarding the associations between attachment orientations and partner maltreatment. We hypothesize that attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance will be positively associated with (1) partner maltreatment overall, and (2) the three behavioral dimensions of IPA, destructive conflict patterns, and corrosive relationship behaviors. Furthermore, in line with the diathesis-stress model, we hypothesize that (3) stress will moderate (i.e., strengthen) the associations outlined in hypotheses 1 and 2.

Method

A systematic literature search following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009) guidelines was completed in August 2019. Protocols for the database searches, study inclusion and exclusion criteria, and data extraction were developed a priori.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria

Initially, we systematically searched a series of electronic databases and the papers identified were assessed against the predetermined inclusion criteria. Retrieved papers were retained if they were (1) original research, (2) written in English, and (3) examined the direct association between the perpetrator’s adult attachment orientation and perpetration of partner maltreatment behaviors. Additionally, studies were retained only if (4) sufficient data to permit calculation of effect sizes were provided. Book chapters, conference papers, and doctoral dissertations were included if the data were not presented elsewhere.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were not retained if the study samples included participants under the age of 18. Single case studies, qualitative studies, and studies reporting data exclusively for victims of partner maltreatment behaviors were excluded. Additionally, studies were not retained if the measures of attachment did not specifically measure adult attachment. Statistically dependent samples were excluded to avoid double counting (Borenstein et al., 2009; Ellis, 2010). Specifically, if multiple studies drew from the same sample, only one study using the sample was included with preference given to the study with the largest sample size or for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Search Strategy

Before finalizing the search strategy, the research team consulted with a university library specialist. The search for relevant studies was conducted in August 2019. We conducted parallel systematic searches on five EBSCOhost databases (PsycINFO, Medline Complete, Academic Search Complete, Psychological and Behavioral Science Collection, and Social Work Abstracts). Search terms encompassed three major concepts— adult attachment, romantic relationships, and partner maltreatment, as detailed in Supplementary Material (see Table S2). In order to add precision to the search, suffixes (“TI” OR “AB”) were added to the terms to allow us to limit the search for the key terms in the title and abstract specifically (Taylor et al., 2003). No further limitations were added.

Study Selection, Quality Assessment, and Data Extraction

Study selection

One member of the research team screened all records from the database search and assessed the full-text articles for eligibility against the predetermined criteria. Another research team member independently assessed a random selection (30%) of the full-text articles for eligibility against the predetermined criteria, with unanimous consensus reached through discussion among all authors.

Quality assessment

Methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS; Downes et al., 2016). The AXIS assesses the quality, design, risk of bias, and selective reporting of non-experimental, cross-sectional research. The AXIS requires a yes/no response to a checklist of items regarding the appropriateness of a study’s sampling approach for meeting the aims (i.e., sample size justification, sampling frame, and sample selection), the use of valid and reliable measures for the outcomes, description of the data analysis plan, complete reporting of the methodological procedure, comprehensive and consistent description of the results, justified and consistent interpretations and conclusions, and compliance with research ethics standards. Although the tool was not designed to compute a quality numerical scale, numerical scales have been applied to the tool in systematic-reviews and meta-analyses of correlational and cross-sectional studies across disciplines (Jordan et al., 2018; Marzi et al., 2018; Wong et al., 2018). In the current meta-analyses, we evaluated study quality by the percentage of the AXIS tool criteria satisfied, where we determined a study to be of high research quality if the characteristics of the study fulfilled greater than 80% of the AXIS tool criteria.

Data extraction

One member of the research team extracted all data, which was then reviewed by another research team member. Data extraction included study characteristics (e.g., sample size, source of the sample, data collection method, measures of adult attachment orientation used, type of partner maltreatment) and any quantitative data relevant to the estimation of effect sizes in the meta-analysis. Despite some studies having other key findings or a wider focus, only the data addressing the association between insecure attachment orientations and partner maltreatment perpetration were extracted from the studies. Where studies reported results separately for men and women, independent effect sizes were calculated. Effect sizes of longitudinal studies with various time points were averaged so only one effect size of the association between attachment orientation and partner maltreatment was included. Of the included studies, stress was extracted as a moderator if (1) events or symptoms of stress were explicitly measured, (2) stress was induced in an experimental design, or (3) stress was implied by the population within which the research was conducted (e.g., couples new to parenthood or couples dealing with the chronic illness of a partner).

Finally, in line with contemporary conceptualizations of adult attachment orientations (Brennan et al., 1998; Gillath et al., 2016), the current meta-analysis considered attachment orientations as continuously distributed along the dimensions of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance. As such, results are discussed in terms of the two primary dimensions. Although some of the studies that were included in the current meta-analysis used categorical measures of attachment, these were either grouped dimensionally or preference was given to the continuous measures of attachment orientation. It has been demonstrated that categorical measures of attachment are underpinned by the dimensions of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance (Fraley & Waller, 1998; Gillath et al., 2016), which allows for this grouping in the current meta-analysis.

Data Analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted in Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3.3.070 (CMA; Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA; Borenstein et al., 2009). Extracted effect sizes from each included study were entered into CMA. The effect size metric varied across the studies; hence to allow for cross-study comparison all reported effect sizes were converted to a common metric—Pearson’s r correlation—within CMA. CMA also calculates ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CI) for all effect sizes to determine whether correlations significantly differed from zero. We conducted separate meta-analyses using each of the two attachment dimensions as predictor variables.

To account for potential statistical dependence that can arise from extracting multiple effect size estimates from the same study (i.e., multiple measurements completed by the same sample), the unit of analysis was set at the level of the study in CMA. This feature in CMA allows the program to combine multiple effect size estimates from a single study into one effect (Borenstein et al., 2009). Additionally, because of the variability within the included individual studies’ characteristics, all effect sizes were analyzed using a random effects model (Borenstein et al., 2010; Card, 2012). The heterogeneity of the current meta-analytic effect sizes was assessed using the Q statistic (Cochran, 1954) and the I2 (Higgins & Thompson, 2002).

The analyses were conducted in three stages. In the first stage, we estimated effect sizes for the association between attachment orientations and the perpetration of partner maltreatment overall, as well as with the dimensions theorized to comprise partner maltreatment (i.e., IPA, destructive conflict patterns, and corrosive relationship behaviors).

In the second stage, to determine the robustness of the findings established in the first stage, and to account for any methodological effects, we also investigated particular sample and study characteristics. To do this, we conducted a series of subgroup analyses to investigate whether the main effects were moderated by methodological variables (e.g., method of measuring outcomes), population type (e.g., community vs. student vs. clinical vs. offender populations) and approaches taken to measuring attachment orientations (e.g., continuous vs. categorical assessments). Z-tests were used to compare effect size estimates for each subgroup analysis against the overall average effect sizes established in the meta-analyses. If there were no statistically significant differences between the subgroup effect estimates and the overall averaged effect sizes, it would suggest the overall averaged effect sizes obtained in this meta-analysis are robust to methodological effects.

In the third stage, subgroup analyses were undertaken to determine the extent to which the associations between attachment orientations and partner maltreatment overall, as well as the three dimensions suggested to comprise partner maltreatment, were moderated by stress. Similar to the analyses in stage two, Z-tests were conducted to compare the effect estimate of the subgroup analysis against the overall averaged effect sizes; where a significant Z-test would indicate stress had significantly moderated the associations.

Publication Bias

Publication bias was assessed by visually inspecting the funnel plots of the main combined effects reported. Additionally, to determine whether any detected asymmetry of the funnel plots (i.e., potential publication bias) was statistically significant, Egger’s test of the intercept (Egger et al., 1997) was conducted. Where statistically significant publication bias was detected, we implemented Duval and Tweedie’s (2000) trim-and-fill analysis.

Sensitivity Analysis

A one-study-removed analysis was conducted in CMA to assess whether the overall averaged effect size estimates are unduly influenced by any potential outlier studies. The one-study-removed analysis systematically removes a single study at a time and recalculates the overall averaged effect with that one study removed from the average estimate. Hence, the one-study-removed analysis re-calculates as many effect sizes as there are studies in the overall meta-analysis. If the recalculated effect size falls outside the 95% CI of the overall average effect size, then the removed study is considered an outlier affecting the robustness of the findings.

Results

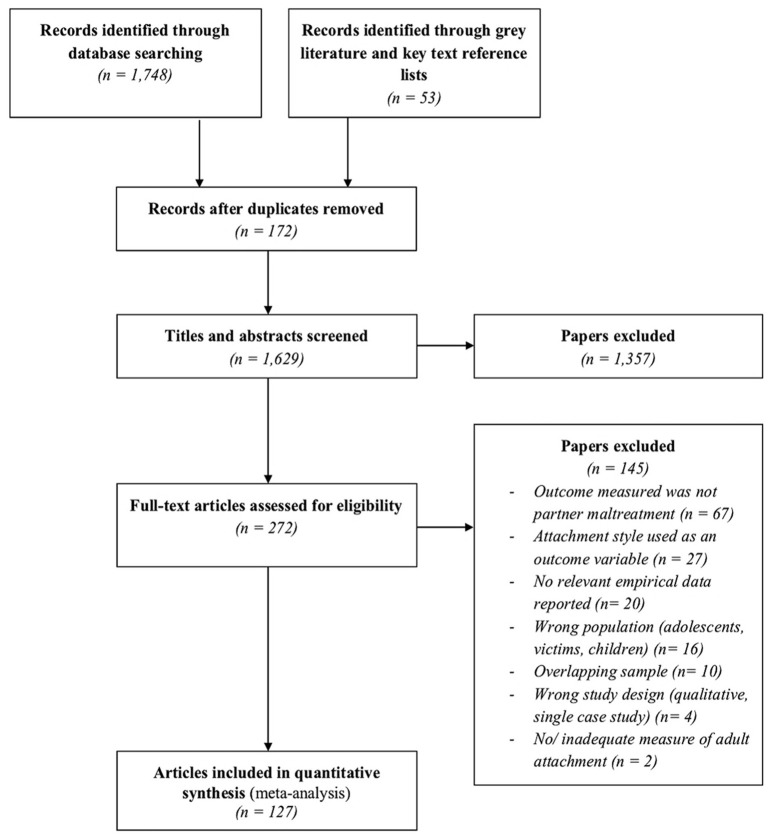

The initial search yielded 1,801 records and the screening process yielded a total of 127 records (see Figure 1—PRISMA flowchart). Of these 127 records, 6 records detailed multiple studies assessing the effect of attachment insecurity on partner maltreatment behaviors. Therefore, a total of 139 studies were included in the meta-analysis. From this sample of 139 studies, only a small number of studies reported effect sizes that could be extracted for the investigation of stress as a moderator of the association between attachment orientation and the perpetration of partner maltreatment (k = 11; see Supplement Material, Table S3). Further details regarding the characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis are presented in the Supplement Material (Table S3).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart.

Study Quality

The majority of studies included in the meta-analysis demonstrated high research quality across the domains of the AXIS critical appraisal tool (see Supplement Material, Table S4). Of the 139 studies in the current meta-analysis, 131 studies fulfilled greater than 80% of the AXIS criteria. All studies were considered to have a clear statement of the aims and an appropriate research design to address the aims. However, commonly missed AXIS criteria included relying on convenience sampling, failure to report whether the sample size was calculated to ensure sufficient statistical power, and failure to include any measures to address, categorize, or describe non-responders.

There were eight studies that failed to satisfy at least 80% of the AXIS criteria. Specifically, all eight of these studies did not include the aforementioned commonly missed criteria, and furthermore, they did not report compliance with ethical standards or conflict of interest. Nevertheless, it was deemed that not reporting ethics approval and stating a conflict of interest was of no critical impact to the studies’ quality. Hence, no studies were excluded on the basis of quality.

The Association Between Attachment Insecurity and Partner Maltreatment

Attachment anxiety

The average weighted effect size between attachment anxiety and the perpetration of partner maltreatment overall was small but significant (see forest plot [Figure S1 in Supplement Material]; see Table 1). Similarly, the effect sizes between attachment anxiety and the three dimensions of partner maltreatment—IPA, destructive conflict patterns, and corrosive relationship behaviors—also demonstrated small yet significant associations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Random-Effects Meta-Analysis of Relationships Between Attachment Orientation and Partner Maltreatment across All Studies.

| Relationship | k | r | 95% CI | Q | I2 (%) | Moderated r | Z-test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment anxiety | |||||||

| Partner maltreatment | 134 | .19 *** | .15, .22 | 1076.77 *** | 87.65 | .24 *** | 2.15 * b |

| Intimate partner abuse | 68 | .19 *** | .13, .25 | 864.00 *** | 92.26 | .24 ** | 0.61 |

| Destructive conflict patterns | 37 | .17 *** | .13, .21 | 117.43 *** | 69.34 | .23 *** | 1.85 * a |

| Corrosive relationship behavior | 24 | .21 *** | .16, .26 | 90.56 *** | 74.60 | .29 *** | 1.44 |

| Attachment avoidance | |||||||

| Partner maltreatment | 125 | .14 *** | .10, .19 | 1784.50 *** | 93.05 | .21 *** | 2.95 ** b |

| Intimate partner abuse | 61 | .11 * | .02, .19 | 1449.18 *** | 95.90 | .35 ** | 4.53 *** b |

| Destructive conflict patterns | 34 | .20 *** | .14, .25 | 386.53 *** | 91.20 | .17 * | −0.91 |

| Corrosive relationship behavior | 23 | .12 *** | .06, .17 | 189.67 *** | 88.40 | .14 * | 0.27 |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

One-tailed.

Two-tailed.

p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Table 2.

A Summary of Critical Findings and Implications.

| Critical Findings |

|---|

| • In organizing the diverse array of harmful behaviors perpetrated in relationships, the paper introduces an integrative concept termed partner maltreatment. • Attachment anxiety is associated with partner maltreatment perpetration; however, at the meta-analytic level, this is a small to moderate effect (r = .19. CI [.15, .22], p < .001). • Likewise, attachment avoidance is associated with partner maltreatment perpetration, but the effect is small at a meta-analytic level (r = .14, CI [.10, .19], p < .001). • Stress significantly moderates the association of both insecure attachment orientations with partner maltreatment perpetration, such that when individuals with attachment anxiety or attachment avoidance experience stress, the propensity to maltreat is significantly exacerbated. |

| Implications for Practice, Policy, and Research |

| • Our findings support the application of an attachment theory framework to guide clinical approaches to assessment and intervention for couples experiencing partner maltreatment. • Our findings also provide empirical evidence for the importance of considering and addressing contextual factors, especially stress, for those individuals and couples seeking therapy for partner maltreatment. Helping individuals and couples to identify and understand the impact of stress on their behavior in their romantic relationship may introduce a tangible and readily modifiable point of intervention, which may significantly attenuate an individual’s propensity to maltreat their partner. • The construct of partner maltreatment affords researchers and policymakers a framework to derive a more comprehensive and integrative understanding of the many and varied forms of negative, destructive, and abusive behaviors that occur in close relationships. |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

Attachment avoidance

Like the associations between attachment anxiety and partner maltreatment, similar associations emerged for the association between attachment avoidance and the perpetration of partner maltreatment overall, as well as with the dimensions of partner maltreatment, where the average weighted effect sizes were also small yet significant (see forest plot [Figure S2]; see Table 1).

Analysis of Heterogeneity

Based on Cochran’s Q (Borenstein et al., 2009), there was significant heterogeneity in the estimates of both attachment anxiety, Q(124) = 1054.38, p < .001, and attachment avoidance, Q(113) = 1967.77, p < .001. I2 results indicated a large proportion of heterogeneity in attachment anxiety [I2 = 88.24] and attachment avoidance [I2 = 94.26]. This indicated that the variance in effect sizes may be likely due to sampling error and study characteristics, and therefore moderating variables could be present. We conducted a series of subgroup analyses of the association between attachment orientations and partner maltreatment behaviors in relation to methodological characteristics (e.g., measure of attachment and measure of dependent variable) and sample characteristics (e.g., sample type—clinical, student, community, and offender populations) of the included studies.

Study characteristic subgroup analyses

We undertook a series of subgroup analyses in CMA to investigate the potential moderating effect of the type of attachment measure used (categorical vs. dimensional), the type of method used to measure the dependent variable (self-report vs. observational), and the sampling type (community vs. student vs. clinical vs. offender populations). We analyzed the effect of each moderator separately. Each of these subgroup analyses revealed no statistically significant difference in the effect sizes between the unmoderated and moderated associations, indicating that these methodological variables made near-to-no contribution to the variance (see Supplement Mate, Table S5).

Attachment Insecurity, Partner Maltreatment, and Stress

Subgroup analyses revealed that stress was found to be a significant moderator of the association between attachment anxiety and partner maltreatment perpetration (Z = 2.15, p < .05), as well as the association between attachment avoidance and partner maltreatment perpetration (Z = 2.95, p < .01; see Table 1). Specifically, the effect sizes as moderated by stress were larger in magnitude compared to the unmoderated effects for the associations between both attachment dimensions and partner maltreatment overall as well as most of the associations between the attachment dimensions the three dimensions of partner maltreatment. The only exception was that the association between attachment avoidance and destructive conflict patterns was lower than the unmoderated effect. However, as seen in Table 1, this attenuated effect did not reflect a significant reduction in effect size; indicating that stress did not moderate the association between attachment avoidance and destructive conflict patterns.

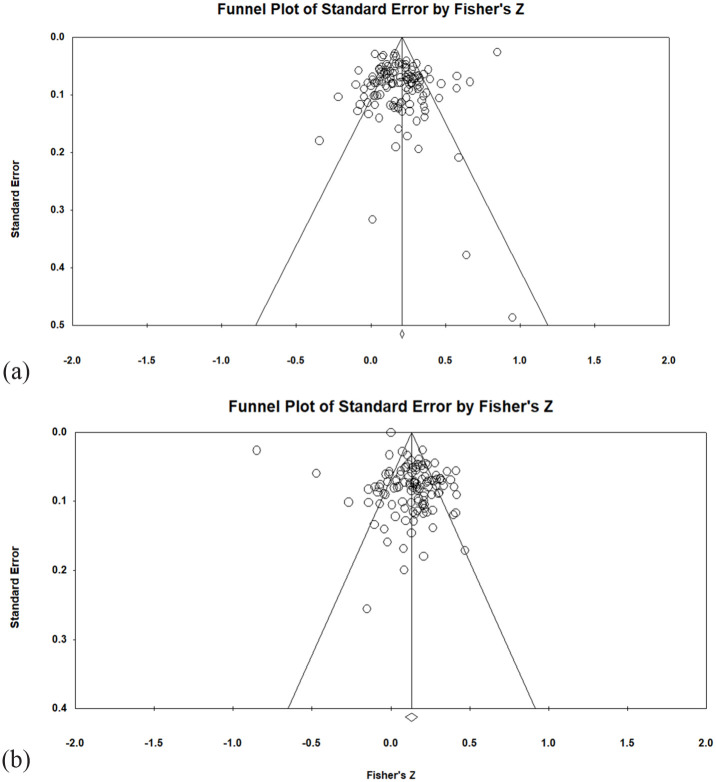

Publication Bias

We assessed the impact of publication bias on the size of the effects reported by examining the funnel plots of the analyses of both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance and using two statistical indicators. First, we visually inspected the funnel plot for the analysis of attachment anxiety (see Figure 2a). The plotted studies were mostly clustered toward the top of the funnel in a symmetrical pattern for the effect size regarding partner maltreatment overall. Egger’s test of the intercept (Egger et al., 1997) indicated there was no statistically significant asymmetry detected in the funnel plot of attachment anxiety under random effects model (Intercept = −0.79; 95% CI [−2.01, 0.42]; p = 0.10). This suggested there was no apparent publication bias detected for the average effect size for attachment anxiety reported in the current meta-analysis. Given this statistical indicator and the high portion of unpublished studies included in this meta-analysis, it was reasonable to conclude the risk of publication bias in the average effect size estimate for attachment anxiety reported in the current meta-analysis was low.

Figure 2.

(a) Funnel plot attachment anxiety. (b) Funnel plot attachment avoidance.

Next, we assessed the likelihood of publication bias and its impact on the associations between attachment avoidance and overall partner maltreatment. Although the studies on the funnel plot for attachment avoidance were mostly clustered at the top of the graph, the asymmetry observed suggested that publication bias may be present in the attachment avoidance analysis (see Figure 2b). Confirming this, Egger’s test of the intercept (Egger et al., 1997) demonstrated a potential for publication bias (Intercept = 1.64; 95% CI [0.92, 2.36]; p < .001). In light of this finding, we conducted Duval and Tweedie’s (2000) trim-and-fill method to quantify the magnitude of the bias.

Durval and Tweedie’s (2000) trim-and-fill method suggested 29 studies were missing to the left of the mean effect of attachment avoidance under the random effects model. The trim-and-fill analysis suggested if publication bias were accounted for, the overall effect size would be adjusted to r = .07 (95% CI [0.04, 0.10], p < .01). Although the adjusted effect size remained positive, significant, and the adjusted confidence intervals did not cross zero, the trim-and-fill analysis suggested the overall effect size was attenuated to be small in magnitude. Together, these statistical indicators suggested that the average effect size for attachment avoidance reported in the current meta-analysis may reflect evidence of publication bias.

Sensitivity Analysis

The one-study-removed analyses showed that the results of the two analyses (e.g., attachment anxiety on overall partner maltreatment and attachment avoidance on overall partner maltreatment) were stable and not dependent on any one study alone (see Supplement Material, Figure S3 and Figure S4). Specifically, all recalculated effect sizes were estimated within the 95 percent confidence interval of the average effect size for attachment anxiety (95% CI [0.16, 0.22]) and attachment avoidance (95% CI [0.09, 0.17]). Therefore, no study was considered to be an outlier.

Discussion

The conceptualization of partner maltreatment proposed as part of this paper provides an important organizing framework to examine the associations between attachment orientations and relationship behaviors that reflect acts of invalidation, disrespect, aggression, and neglect toward a partner. The behaviors that encompass partner maltreatment range from severe and overt acts, such as interpersonal abuse, through to behaviors that can be considered more subtle and less egregious in nature, such as conflict avoidance, manipulation, and insensitive caregiving. Importantly, the concept of partner maltreatment afforded the synthesis of a large body of studies across two distinct, yet complementary areas of research into attachment orientations and the perpetration of destructive and abusive relationship behaviors: the fields of family violence and relationship science. Additionally, the current meta-analysis significantly advances our understanding of the role of insecure attachment orientations in the perpetration of partner maltreatment by examining the moderating role of stress—a critical factor to consider not only within the context of maltreatment but also when examining attachment dynamics. Until this point, the moderating role of stress has not been systematically reviewed and evaluated in the literature. As such, the current meta-analysis situated partner maltreatment within a diathesis-stress perspective. To address the aims of this review, we synthesized the effect sizes from 139 studies that were identified as investigating the association between adult attachment orientations and the perpetration of partner maltreatment.

Attachment Insecurity and Partner Maltreatment

As hypothesized, we found a significant positive association between attachment anxiety and overall partner maltreatment perpetration and between attachment avoidance and overall partner maltreatment perpetration. Additionally, these small but significant positive associations were found across the three primary dimensions of partner maltreatment behavior: IPA, destructive conflict patterns, and corrosive relationship behaviors. Specifically, the estimated effects between attachment orientations and partner maltreatment overall and across the specific maltreatment dimensions ranged from r = .11 to r = .21. Taken together, the associations demonstrate that attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance are reliably associated with the perpetration of maltreatment behaviors in romantic relationships. An explanation for these associations emerges when considering the typical underlying interpersonal distance regulation goals associated with attachment anxiety (i.e., desire for closeness) and avoidance (i.e., desire for distance).

Indeed, an anxious attachment orientation is largely characterized by the need for excessive reassurance and closeness with one’s partner (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2011). As such, individuals high on attachment anxiety tend to pursue, approach, and engage their romantic partner in an effort to increase physical or emotional closeness to their partner (Allison et al., 2008). At times when this goal cannot be attained, it may be that these individuals pursue their partner in more negative, coercive, and destructive ways in line with the hyperactivating strategies that underpin attachment anxiety (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2011).

Additionally, consistent with the deactivating strategies that are characteristic of attachment avoidance (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2011), our findings suggest individuals high on attachment avoidance tend to engage in behavior indicative of partner maltreatment. An avoidant attachment orientation is marked by a chronic need for distance and independence (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2011). As such, individuals high on attachment avoidance may engage in maltreatment behavior as a means to create or maintain interpersonal distance (Allison et al., 2008). People high on attachment avoidance may typically withdraw, neglect, dismiss, and invalidate their partner (Feeney & Karantzas, 2017; Gillath et al., 2016), which are behaviors indicative of partner maltreatment. However, in situations where their defensive processes have failed to create a desired level of physical or emotional distance from their romantic partner, an individual high on attachment avoidance may also lash out in confrontational, hostile, aggressive and, even, physically violent ways that are uncharacteristic of their typical avoidant patterns of maltreatment (Allison et al., 2008; Bartholomew & Allison, 2006; Karantzas & Kambouropoulos, 2019).

Our findings are consistent with recent meta-analyses which have also estimated a small effect size for the association between insecure attachment orientations and IPA (a single dimension of partner maltreatment; Velotti et al., 2018; Velotti et al., 2022; Spencer, 2021). Our findings, however, significantly extend on this work by integrating other aspects of maltreatment and synthesizing the associations between attachment and the study of a broader range of negative, destructive, and abusive relationship behaviors. Nevertheless, the effect of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance on all forms of partner maltreatment remains small, whether at the overall level of the construct—which includes overt and violent acts through to more subtle and seemingly innocuous behavior—or with the three primary dimensions of maltreatment. These small associations in the current meta-analysis may be reflective of inconsistencies in the results found across the studies included. As a case in point, approximately 30% of studies in the current meta-analysis found attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance had zero or, even, a negative association with partner maltreatment; whereas another portion of studies found large associations (e.g., >0.5; Cohen, 1988; see Supplement Material, Figure S1 and S2). Although our sensitivity analyses indicated that the average weighted effect sizes were stable and not unduly influenced by any one study, the inconsistent findings across studies suggest that the likelihood of maltreating a partner may fluctuate for individuals high on attachment anxiety and/or attachment avoidance. Below, we explore the moderating role of stress, which may speak to the heterogeneity of effects evidenced in the literature.

Attachment Insecurity, Stress, and Partner Maltreatment

Models related to various forms of maltreatment, such as the I3 Model (pronounced “I-cubed”) and the General Aggression Model, highlight the critical interactive role of stress in the enactment of negative, destructive, and abusive relationship behaviors (Allen et al., 2018; Anderson & Bushman, 2002; Eckhardt & Parrot, 2017). Additionally, from an attachment theory perspective, stress is considered a critical factor in understanding attachment dynamics within close relationships (Simpson & Rholes, 1996, 2012, 2017). As such, we incorporated a diathesis-stress perspective to test the moderating role of stress in the association between attachment orientations and partner maltreatment overall. Consistent with the diathesis-stress perspective, stress moderated (i.e., strengthened) the association between attachment anxiety and partner maltreatment overall, as well as the association between attachment avoidance and partner maltreatment overall. These findings suggest that for insecurely attached individuals, stress can indeed heighten the propensity to maltreat a partner. However, when we examined the moderating effect of stress on the associations between attachment insecurity and the behavioral dimensions of partner maltreatment, the findings were less consistent.

For example, the associations between attachment anxiety or avoidance and the three dimensions of partner maltreatment were typically higher in magnitude when moderated by stress; however, for the most part, the moderated effect sizes were not significantly different to the unmoderated effect sizes. Specifically, although the moderated associations were positive and significant, z-tests revealed that only two of these associations were significantly larger than the unmoderated associations. Of these two significant moderated effects, the first revealed stress significantly strengthened the association between attachment anxiety and destructive conflict patterns, indicating that an anxiously attached individual’s tendency to engage destructively in conflict with a partner is exacerbated by stress. Indeed, this is in line with their tendency to experience a heightened distress response in times of stress that can heighten dysfunctional behaviors in close relationships (Collins & Read, 1994; Simpson et al., 1996; Tran & Simpson, 2009).

The second significant moderated effect indicated that stress strengthened the association between attachment avoidance and IPA, indicating that stress may be an important moderating factor in understanding why individuals high on attachment avoidance may engage in IPA. Recent research indicates that individuals high in attachment avoidance enact relationship aggression as a defensive fight response in stressful conflict situations when there is little opportunity to avoid confrontation (Karantzas & Kambouropoulos, 2019). Consequently, when experiencing heightened stress, individuals high in attachment avoidance may aggressively act out to limit conflict engagement and further escalation of distress. It may be that when stress reaches a particularly high level, strategies of withdrawal and avoidance do not aid avoidant individuals to meet their goal for interpersonal distance. That is, the tendency to behave in an aggressive, confronting, and pursuit-like manner increases when stress reaches a point at which avoidant individuals can no longer suppress or downregulate their stress.

Together these findings provide meta-analytic support for the application of attachment-based diathesis-stress model to the study of partner maltreatment. Specifically, these findings suggest that attachment insecurity is a diathesis which predisposes individuals to perpetrate partner maltreatment, and when individuals with an anxious or avoidant attachment orientation experiences stress, the tendency to perpetrate partner maltreatment is heightened. However, the findings in the current meta-analyses must be considered in light of the sample characteristics of the primary studies included in the meta-analyses. Although subgroup analyses indicated, there were no significant difference between sample types (e.g., community, student, clinical and offender populations; see Supplement Material, Table S5), it is important to note that the vast majority of samples were university students or community samples, which in the IPV literature are thought to have typically, but not all the time, less severe or high-risk abuse tactics (Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al., 2012). Additionally, most studies’ samples consisted of participants who were identified as heterosexual. However, partner maltreatment is not unique to heterosexual couples (Trombetta & Rollè, 2022). Thus, to expand the generalizability of the findings from the current meta-analysis, future research should be conducted with more diverse and representative samples. Further discussion of the limitations of this meta-analysis and future research directions are presented below.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this review integrates two large research fields regarding negative relationship behaviors and represents the first quantitative examination of the association between attachment orientations and partner maltreatment and the moderating role of stress, there are some limitations. First, although the findings point to a significant positive association between both dimensions of attachment insecurity and partner maltreatment, these results do not necessarily indicate a causal relationship. Our meta-analysis established the magnitude of the associations between these variables—findings which do not imply causation. Furthermore, the majority of these studies were cross-sectional in nature, and thus, are further limited in our ability to make any causal inferences.

Second, publication bias was detected in the estimate of the association between attachment avoidance and partner maltreatment. Visual inspection of the funnel plot asymmetry indicated the estimate may be inflated, and statistical correction for this bias estimates the effect to be small in magnitude. However, this adjusted effect remained positive, significant, and the adjusted 95 percent confidence intervals did not cross zero. As such, we have some confidence about the significant association between attachment avoidance and partner maltreatment.

Third, there was a high degree of heterogeneity when estimating the effects for attachment anxiety on partner maltreatment and attachment avoidance on partner maltreatment. Despite sensitivity analyses suggesting that the average weighted effect sizes are stable and not dependent on any one study, examination of the forest plots (see Supplement Material, Figure S1 and S2) revealed inconsistencies in the associations reported across the studies included in the current meta-analyses. Given our subgroup analyses revealed no significant variability in terms of methodological aspects of studies (i.e., sample population type, attachment measure used, and method of measuring outcomes), the degree of heterogeneity may suggest that an insecure attachment orientation is just one of a number of factors that contribute to the perpetration of negative behaviors in romantic relationships.

Indeed, the etiology of partner maltreatment is complex and, as has been suggested in the current meta-analysis, it is critical to consider the context within which maltreatment occurs. In fact, there are likely to be many important contextual variables—such as stressful conditions and other potential explanatory variables—that are likely to be associated with the perpetration of partner maltreatment (Capaldi et al., 2012; Finkel, 2007). Hence, future research in this area should move beyond focusing on direct associations between attachment insecurity and these maltreatment behaviors, and instead, prioritize uncovering the explanatory variables and contextual factors that can make sense of the heterogeneity of effects evidenced in the literature.

Finally, the data available to determine the moderating role of stress only allowed for a course dichotomization of stress (i.e., presence of stress versus absence of stress), and some categorizations of stress were implied by the population within which the research was conducted (e.g., couples new to parenthood or couples dealing with the chronic illness of a partner). A limitation with these categorical operationalizations of stress is that it assumes between category variance is more important than within category variance. Nevertheless, continuous measures of stress capture variability that is meaningful across the stress continuum. Thus, future research may look toward incorporating validated measures of stress to allow for a more comprehensive assessment and modeling of the role of stress in the association between attachment orientations and partner maltreatment.

Conclusion

The current meta-analysis provides a highly integrative review, which draws together two disparate, yet complementary literatures regarding negative, destructive, and abusive behaviors within a cohesive framework of partner maltreatment. The conceptualization of partner maltreatment as a broad overarching construct facilitated a systematic and structured synthesis of the literature to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the role of attachment orientations and the moderating effect of stress in the perpetration of partner maltreatment. Our findings provide meta-analytic evidence to suggest that attachment insecurity (i.e., levels of attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance) is an important individual vulnerability factor (diathesis) associated with partner maltreatment. Our meta-analysis also suggests, when individuals with an insecure attachment orientation experiences stress, the tendency to perpetrate partner maltreatment is heightened. These findings provide support for the application of a diathesis-stress model in understanding the enactment of negative, destructive, and abusive behaviors in romantic relationships. It is hoped that the findings of this meta-analysis provide a basis for future research on attachment orientations and partner maltreatment perpetration as well as inform therapeutic directions when working with couples experiencing such negative and destructive behaviors in their romantic relationships.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tva-10.1177_15248380231161012 for The Role of Attachment, Insecurity, and Stress in Partner Maltreatment: A Meta-Analysis by Laura Knox, Gery Karantzas and Elizabeth Ferguson in Trauma, Violence, & Abuse

Author Biographies

Laura Knox is a research fellow and PhD candidate within the School of Psychology at Deakin University, and a counselling psychologist. Her research focuses on social psychology, romantic relationships, partner maltreatment, adult attachment, and stress. She has extensive experience in systematic synthesis of research literature.

Gery Karantzas, PhD, is a Professor in the School of Psychology and Director of the Science of Adult Relationships Laboratory at Deakin University. He has authored approximately 100 publications largely within the area of couple and family relationships. His work is generally underpinned by an attachment theory perspective.

Elizabeth Ferguson is a research assistant at Deakin University and a clinical psychologist. Her research focuses on clinical and social psychology, and the role of self-regulation and partner regulation in romantic relationship conflict. She has extensive experience in systematic synthesis of research literature.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This project was supported through the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Portions of these findings were presented as a talk presented in a symposium entitled “Insights into intimate partner maltreatment, abuse and aggression,” at the 18th Annual Psychology of Relationships Interest Group Conference, Melbourne, Australia.

Data Availability: Study data for all analyses contained in this article are located on Open Science Framework—https://osf.io/kdu7x/?view_only=efa6b4aaf9de48348607064c06e5b20c.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Laura Knox  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4339-2660

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4339-2660

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

A list of references included in the meta-analyses can be found in Supplement Material (p. 44).

- Allen E. S., Baucom D. H. (2004). Adult attachment and patterns of extradyadic involvement. Family Process, 43, 467–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J. J., Anderson C. A., Bushman B. J. (2018). The general aggression model. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, 75–80. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison C. J., Bartholomew K., Mayseless O., Dutton D. G. (2008). Love as a battlefield: Attachment and relationship dynamics in couples identified for male partner violence. Journal of Family Issues, 29(1), 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C. A., Bushman B. J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 27–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaro N., Shackelford T. K. (2019). Environmental unpredictability in childhood is associated with anxious romantic attachment and intimate partner violence perpetration. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(2), 240–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew K., Allison C. J. (2006). An attachment perspective on abusive dynamics in intimate relationships. In Mikulincer M., Goodman G. S. (Eds.), Dynamics of Romantic Love (pp. 102–127). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bonache H., Gonzalez-Mendez R., Krahé B. (2019). Adult attachment styles, destructive conflict resolution, and the experience of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(2), 287–309. 10.1177/0886260516640776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala J. (2002). The role of own and perceived partner attachment in relationship aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 17(1), 84–100. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M., Hedges L. V., Higgins J. P. T., Rothstein H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley. 10.1002/9780470743386 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M., Hedges L. V., Higgins J. P., Rothstein H. R. (2010). A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(2), 97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Attachment (Vol. 1). Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1982). Attachment and loss: retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52(4), 664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M., Hales S., Gilad L., Mikulincer M., Rydall A., Rodin G. (2012). Caregiving styles and attachment orientations in couples facing advanced cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 21(9), 935–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan K. A., Clark C. L., Shaver P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In Simpson J. A., Rholes W. S. (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp 46–76). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Brock R. L., Lawrence E. (2014). Intrapersonal, interpersonal, and contextual risk factors for overprovision of partner support in marriage. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(1), 54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano A., Vivian D. (2003). Are life stressors associated with marital violence? Journal of Family Psychology, 17(3), 302–314. 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D. M., Knoble N. B., Shortt J. W., Kim H. K. (2012). A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 3(2), 231–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card N. A. (2012). Applied meta-analysis for social science research. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J., Shaver P. R. (Eds.). (2002). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Rough Guides. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran W. G. (1954). The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics, 10(1), 101. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Collins N. L., Feeney B. C. (2000). A safe haven: An attachment theory perspective on support seeking and caregiving in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(6), 1053–1073. 10.1037/0022-3514.78.6.1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins N. L., Read S. J. (1994). Cognitive representations of attachment: The structure and function of working models. In Bartholomew K., Perlman D. (Eds.), Attachment processes in adulthood (pp. 53–90). Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Crangle C. J., Hart T. L. (2017). Adult attachment, hostile conflict, and relationship adjustment among couples facing multiple sclerosis. British Journal of Health Psychology, 22(4), 836–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creasey G. (2002). Associations between working models of attachment and conflict management behaviour in romantic. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49(3), 365–375. [Google Scholar]

- DeWall C. N., Lambert N. M., Slotter E. B., Pond R. S., Jr., Deckman T., Finkel E. J., Luchies L. B., Fincham F. D. (2011). So far away from one’s partner, yet so close to romantic alternatives: Avoidant attachment, interest in alternatives, and infidelity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(6), 1302–1316. 10.1037/a0025497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downes M. J., Brennan M. L., Williams H. C., Dean R. S. (2016). Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open, 6(12), 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton D. G., White K. R. (2012). Attachment insecurity and intimate partner violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 17(5), 475–481. 10.1016/j.avb.2012.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duval S., Tweedie R. (2000). Trim and Fill: A simple funnel-plot—based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt C. I., Parrott D. J. (2017). Stress and intimate partner aggression. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 153–157. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein R. S., Shaver P. R. (2004). Avoidant attachment: Exploration of an oxymoron. In Mashek D. J., Aron A. (Eds.), Handbook of closeness and intimacy (pp. 397–414). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Smith G. D., Schneider M., Minder C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis P. D. (2010). The essential guide to effect sizes: Statistical power, meta-analysis, and the interpretation of research results. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney J. A. (1999). Issues of closeness and distance in dating relationships: Effects of sex and attachment style. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 16(5), 571–590. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney J. A. (2017). Understanding couple conflict from an attachment perspective. In Fitzgerald J. (Ed.), Foundations for couples therapy (pp. 103–113). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney J., Fitzgerald J. (2018). Attachment, conflict and relationship quality: Laboratory-based and clinical insights. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney J. A., Karantzas G. C. (2017). Couple conflict: Insights from an attachment perspective. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel E. J. (2007). Impelling and inhibiting forces in the perpetration of intimate partner violence. Review of General Psychology, 11(2), 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel E. J., Eckhardt C. I. (2013). Intimate partner violence. In Simpson J. A., Campbell L. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of close relationships (p. 452–474). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad D. R., Bradley R. G., Helff C. M., Laughlin J. E. (2002). A model for predicting dating violence: Anxious attachment, angry temperament, and need for relationship control. Violence and Victims, 17(1), 35–47. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley R. C., Waller N. G. (1998). Adult attachment patterns: A test of the typological model. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley R. C., Waller N. G., Brennan K. A. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(2), 350–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey L. M., Blackburn K. M., Werner–Wilson R. J., Parker T., Wood N. D. (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder, attachment, and intimate partner violence in a military sample: A preliminary analysis. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 23(3–4), 218–230. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbay N., Lafontaine M. F. (2017). Understanding the relationship between attachment, caregiving, and same sex intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence, 32, 291–304. [Google Scholar]

- Gillath O., Karantzas G. C., Fraley R. C. (2016). Adult attachment: A concise introduction to theory and research. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gormley B., Lopez F. G. (2010). Psychological abuse perpetration in college dating relationships: Contributions of gender, stress, and adult attachment orientations. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(2), 204–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]