Abstract

Current views of psychological therapies for trauma typically assume the traumatic event to be in the past. Yet, individuals who live in contexts of ongoing organized violence or experience intimate partner violence (IPV) may continue to be (re)exposed to related traumatic events or have realistic fears of their recurrence. This systematic review considers the effectiveness, feasibility, and adaptations of psychological interventions for individuals living with ongoing threat. PsychINFO, MEDLINE, and EMBASE were searched for articles that examined psychological interventions in contexts of ongoing threat of either IPV or organized violence and used trauma-related outcome measures. The search was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Data on study population, ongoing threat setting and design, intervention components, evaluation methods, and outcomes were extracted, and study quality was assessed using the Mixed-Method Appraisal Tool. Eighteen papers featuring 15 trials were included (12 on organized violence and 3 on IPV). For organized violence, most studies showed moderate to large effects in reducing trauma-related symptoms when compared to waitlists. For IPV, findings were varied. Most studies made adaptations related to culture and ongoing threat and found that providing psychological interventions was feasible. The findings, albeit preliminary with mixed methodological quality, showed psychological treatments can be beneficial and should not be withheld in the context of ongoing organized violence and IPV. Clinical and research recommendations are discussed.

Keywords: psychological trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, continuous traumatic stress, psychotherapy, violence, systematic review

Introduction

Existing diagnostic criteria, models, and treatment interventions of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) typically focus on trauma as a past event. Thereby we cannot ascertain if the recommended interventions apply in the context of continued threat. PTSD can only be diagnosed if symptoms of re-experiencing of traumatic events, avoidance, negative cognition, and mood, as well as alternations in arousal, have persisted for at least 1 month (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), meaning that a traumatic event would have occurred at least a month before diagnosis. In addition, prevailing models of trauma, such as the Cognitive Model of PTSD (Ehlers & Clark, 2000), conceptualize trauma exposure in relation to past occurrences, which lead to a sense of current threat. These conceptualizations do not specifically address the understanding and treatment of individuals and groups who are exposed to continuous actual or threatened traumatic events such as in war and conflict settings (Eagle & Kaminer, 2013). In such circumstances, the sense of current threat may not only be understandable but also be adaptive for survival (Rosenberg et al., 2008). The clinical position typically taken by professionals, however, is that “safety” and “stabilization” need to be established before commencing psychological treatments. For example, in intimate partner violence (IPV) research, participants are typically recruited from those who live in shelters and/or have not experienced any abuse for the previous month (Crespo & Arinero, 2010; Johnson et al., 2011). Although they might still experience threats and assaults from their (ex)partners, these studies excluded people who were still living in violent households. Other research does not distinguish between people with recent trauma history (within the last 12 months) or ongoing trauma through IPV (Keynejad et al., 2020). Not differentiating between past or ongoing trauma limits our understanding of effective psychological or psychosocial interventions for these individuals and communities. In addition to the argument for safety and stability comes the controversy whether offering treatment shortly after a traumatic event is advisable. Examples of this discussion include debriefing (van Emmerik et al., 2002) and Trauma Risk Management (Greenberg et al., 2010). Therefore, there is an urgent need to review the empirical evidence rather than relying on the normative clinical position. To resolve this clinical position, not only should we examine whether interventions are effective but also whether they cause harm.

Researchers have conceptualized ongoing trauma in various ways. Continuous traumatic stress (CTS) by Straker and The Sanctuaries Counselling Team (1987) describes emotional or behavioral responses to past and current danger resulting from living in states of realistic ongoing threat including political, civil, or community violence, while others have argued ongoing stressors or daily hassles are distinct constructs from past trauma (Tay & Silove, 2017) and should be approached separately. Researchers appear divided into two schools of thought: present-focused versus trauma-focused interventions. Diamond et al.’s (2010) work focused on addressing current dangers and anxiety rather than processing past traumatic events for people experiencing ongoing trauma stress response. On the other hand, the use of exposure-based trauma-focused therapies under ongoing threat was supported in case studies (Murray et al., 2013) and case series (Gillespie et al., 2002). These studies argue that past trauma impaired individuals’ ability to effectively manage the continuing. Therefore, trauma-focused treatments could play an important role in reducing distress and increasing coping for those living in ongoing threat situations. It seems that there are significant gaps in the evidence base regarding the distinct treatments and effectiveness for people living in the context of ongoing threat.

In implementation science, Brownson et al. (2012) argued that effectiveness might not be the only indicator that determines the success of an intervention. They suggested a framework including acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, cost, feasibility, fidelity, access to service, and sustainability. In particular, there are often feasibility challenges in conducting research and implementing psychological interventions in ongoing threat settings. These include security and safety concerns for clients and treatment providers, such as study sites being shut down due to bombings, as well as logistical problems for therapists and clients seeking to attend sessions, and difficulties for clients to concentrate in sessions (Murray et al., 2014). Feasibility of psychological interventions may also be impacted by cultural contexts in settings of ongoing threat. Culturally, there are debates over the validity of the concept of PTSD in developing regions and interventions may need to be adapted due to different interpretations of illness and reactions to stressors (Hinton & Lewis-Fernández, 2011). A review found that the majority of studies used the Western diagnosis of PTSD to treat non-Western cultures (Ennis et al., 2020). They also concluded that, although many PTSD intervention (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT] and eye moment desensitization and reprocessing [EMDR]) were originally developed in Western countries, the process of how and why cultural adaptations were made is often left unclear, or significant adaptations (such as inclusion of local stakeholders) were missed. In conclusion, when considering feasibility, practical considerations such as safety and security need to be taken into account, as well as cultural and context-specific adaptations. These challenges to feasibility should not prevent support for those under continuing threat; otherwise, support may be denied to those most in need of it.

The review that comes closest to addressing the current questions is a recent systematic review by Ennis et al. (2021), who examined trauma-focused CBTs for PTSD under ongoing threat. They reviewed 21 studies in populations with ongoing risk of war and community violence, IPV, and work-related traumatic events. Although medium to large treatment effects were found in favor of CBT compared to waitlist controls, the authors cautioned against drawing firm conclusions due to the paucity and heterogeneity of the studies. The current review aims to address the same issue from a broader perspective, and therefore updates and supplements that review. Firstly, Ennis and colleagues only included CBT interventions in their review, with the reasoning that it is recommended as first-line treatment for PTSD (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2017), without acknowledging that these recommendations are largely based on treatment of past trauma and in setting without current threat. They therefore may have missed valid and effective interventions for ongoing threat that utilize other approaches. Secondly, their review included populations where ongoing threat may have passed or changed from the original traumatizing events, which may dilute the clarity of interventions for ongoing threat. For example, they also included refugees living in camps and women living in shelters after IPV. Thirdly, while Ennis and colleagues note the importance of considering intervention adaptations due to ongoing threat and review these in their results, an even clearer focus on feasibility, which highlights adaptations in response to ongoing threat and cultural considerations, could help guide future researchers and clinicians. Lastly, Ennis et al. restricted their review to interventions that address PTSD. While this provides a clear structure, it may not measure the full spectrum of distress related to ongoing threat.

Aims

The current paper aimed to extend the Ennis et al. (2021) findings by including non-CBT interventions and feasibility. We included broader trauma-related distress outcomes and adopted a more specific definition of ongoing threat. The objectives of the current systematic review were to consider the effectiveness and feasibility of the full range of psychological interventions for psychological effects of traumatic events in contexts of ongoing threat.

The aim to assess feasibility was not restricted by the use of formal feasibility measures or criteria such as adherence rates. Instead, “feasibility” was considered as any of the “key areas of feasibility” noted by Bowen et al. (2009), such as the practicality of intervention delivery and participation, and implementation within the constraints in resources, as well as the adaptations to suit the populations and the context of ongoing threat (Bowen et al., 2009).

Method

Definition

To avoid confusion, we did not use the term CTS here as there are varied definitions of the construct in relation to whether or not ongoing stress includes daily stressors (Miller & Rasmussen, 2010; Nuttman-Shwartz & Shoval-Zuckerman, 2016). Instead, we used the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) definition of a traumatic event which includes actual or threatened risk of death or physical harm which an individual experienced, witnessed, or learned about (APA, 2013). In the current study, the definition of ongoing threat focused specifically on the following two areas: individuals living in (a) precarious and personally dangerous situation including ongoing socio-political conflict caused by organized violence such as political, armed, and community violence, and (b) IPV. It included ongoing and repeated exposure to direct or witnessed violence, abuse, attacks, armed robberies, bombings, shillings, killings, or ongoing threats of these traumas happening similar to the index trauma (see Supplemental Appendix C). Additionally, the ongoing threat should be related to the individuals’ index trauma for the studies to be included. We adopted the definition of index trauma from the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (Weathers et al., 2013) as either the worst single incident (e.g., “the accident”) or multiple but closely related incidents that caused distress (e.g., multiple bombings, repeated IPV).

Search Strategy

Prior to the systematic search, a brief literature search was conducted to examine key texts in this area and consultations were held with librarians and trauma experts to identify key words and possible intervention types to establish search terms, which included variations of CBT and Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET) etcetera. The final search terms can be found in Supplemental Appendix A. Terms were adapted in different bibliographic databases with database-specific filters and terms. The protocol was preregistered on Prospero (CRD42021277966). A systematic literature search was conducted on May 6, 2021 and updated on January 4, 2022 using PsycINFO (1806-2022), MEDLINE (1946-2022), EMBASE (1974-2022), as well as citation search. Citation search refers to both author citation search (finding all articles by an author) and looking through the bibliography of relevant articles. The search was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009) guidelines.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Table 1. We included children and adults who experienced at least one traumatic event with actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence as defined by the DSM-5 (APA, 2013). The populations of interest were those currently living in states of ongoing threat, specifically in contexts of organized violence (political, civil, or community violence) or IPV. We defined the ongoing threat as living in an environment with realistic and actual threat where traumatic events similar to the index trauma can happen, but not linked to daily stressors or hassles. The Inter-Agency Standing Committee’s (IASC) Guidelines for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergencies recommend a multilayered system of support with varying levels of specialization in the psychosocial support from prevention to treatment (IASC, 2007). We included focused, non-specialized support (focused individual, family or group interventions by trained and supervised workers, basic mental healthcare by primary healthcare workers), and specialized services (psychological or psychiatric support by specialists for people with severe mental disorders) (IASC, 2007). This categorization was used to facilitate evidence building by mapping onto existing internationally-recognized guidelines.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Peer-reviewed articles documenting empirical research, including but not limited to randomized controlled trials, controlled and uncontrolled studies, mixed-method studies, case series | Books, dissertation, conference papers, non-peer-reviewed articles, case studies |

| Participants experienced elevated level of distress as a result (e.g., traumatic stress symptoms, depression, anxiety and quality of life) and at least one of these indicators of distress were reported as an outcome | Not written in English |

| Populations including children and adult experiencing at least one traumatic event with actual or potential actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence as defined by the DSM-5 (APA, 2013) who were currently living in states of ongoing threat specifically in organized violence (political, civil or community violence) or intimate partner violence. The context of the ongoing threat is linked to the “index” traumatic event but not due to daily stressors or hassles | Articles not describing continuous threat; or when the ongoing threat context was not related to community/ political/ war violence, or intimate partner/ domestic violence |

| Interventions were psychologically informed targeting distress relating to the traumatic event(s). The interventions followed the top two levels of IASC guidelines on MHPSS which meant that they were focused, non-specialized support (focused individual, family or group interventions by trained and supervised workers, basic mental healthcare by primary healthcare workers), or specialized services (psychological or psychiatric supports by specialists for people with severe mental disorders) (IASC, 2007). | Exclusion of trauma types included medical trauma, combat/ veteran trauma, work-related trauma (e.g., police, paramedics, healthcare professionals), post-conflict areas or refugees resettled in camps in another country that were not experiencing conflicts, developmental trauma, children affected by parental conflict, vicarious trauma |

| Papers published in “predatory journals.” We decided to exclude studies from predatory journals based on the recommendations from (Munn et al., 2021). In the absence of a standardized definition of “predatory journal,” only indexed studies on bibliographic databases with stringent indexing criteria were included. When assessing the studies especially the ones from citation search and when the publishers’ credibility was queried, we measured those journals against criteria such as whether they were a member of Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) used the Think, Check, Submit campaign checklist (http://thinkchecksubmit.org/). |

Note. DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Data Extraction

The study characteristics extracted were author/s, year of publication, location where the study was conducted, type and definition of ongoing threat, type of intervention, intervention details (frequency, length, content, and provider), adaptations related to culture, context, and ongoing threat (feasibility), study outcomes (effectiveness) and challenges due to ongoing threat (feasibility).

The inclusion of the studies was screened by the first author SHY and cross-rated by HL for 20% of the total studies. At title and abstract screening, there were three disputed studies which were resolved through discussion with PS before full-text screening could proceed. At full-text screening, there were two disputed studies that were resolved after discussion within the research team (see Supplemental Appendix B for justifications).

Quality Appraisal

The methodological quality of included studies was assessed by SHY using the Mixed-Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT; Hong et al., 2018). HL cross-rated 20% of the included studies. The tool, designed for mixed-method systematic reviews, was chosen prior to data analysis as qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies were anticipated and included in the search criteria. This appraisal tool specifies not to create an overall score from the studies or exclude the studies based on the methodological quality. Instead, authors are advised to provide a detailed presentation of the ratings of each criterion to evaluate the strength of the evidence in the results and discussion. The items were designed and revised through a Delphi study (Hong et al., 2019) to increase content validity.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

A narrative synthesis (Popay et al., 2006) of the findings from the included studies was used, structured around demographic information, type of intervention and target, the construct definitions of ongoing threat, methodological quality and threats to validity, intervention design and outcome/effectiveness, and feasibility, challenges and treatment adaptations such as task-shifting (i.e., use of nonspecialist therapists) (Purgato et al., 2020) and cultural adaptations of the therapy.

Results

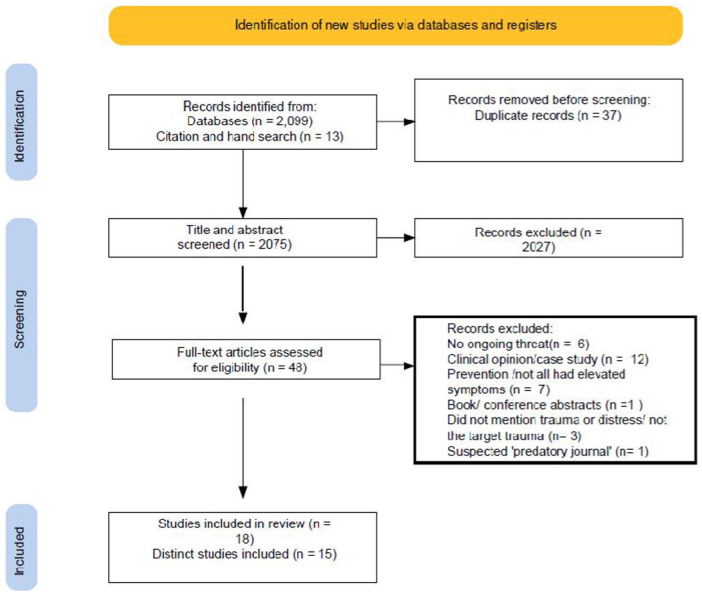

Eighteen papers met inclusion criteria, featuring 15 trials, involving 1867 individuals with elevated levels of trauma-related symptoms, who received psychological interventions while in an ongoing threat context. The updated search yielded 305 more unique entries, but none were relevant to the current review. The PRISMA flowchart is reported below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Note. PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Overview of the Included Studies and Demographics

Studies were conducted in 10 locations (see geographical distributions in Table 2).

Table 2.

Lists of Locations Where Included Studies Took Place.

| Location | Number of Included Papers |

|---|---|

| Colombia | 1 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 2 |

| Hong Kong | 1 |

| Indonesia | 1 |

| Iran | 2 |

| Iraq | 2 |

| Occupied Palestinian Territories | 4 |

| South Africa | 3 |

| Thailand | 1 |

| Zimbabwe | 1 |

The included studies were classified by level of evidence: randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental design and controlled studies, noncontrolled design, and case studies. Eleven out of 15 studies were RCTs, 2 studies adopted a nonrandomized noncontrolled group design, and 2 studies were case series.

The types of intervention are summarized in Table 3. Most studies in the current review used variations of CBT (n = 10, 66.7%), including trauma-focused CBT, internet CBT, NET, cognitive processing therapy (CPT), and teaching recovery techniques (TRT). The rest of the studies (n = 5) used group EMDR, an empowerment intervention, critical incident stress management (CISM), and tree of life healing circles. The intervention duration ranged from a one-off, 30-minute session to 14 weekly 90-minute sessions. An overview of trauma measures is shown in Supplemental Appendix D.

Table 3.

Descriptions of the Interventions.

| Type of Interventions | Number of Studies | Authors (year) | Intervention Details (Frequency, Length, Content, Provider) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT | Trauma-focused CBT | n = 2 | Dawson et al., (2018) | Five weekly 1-hour individual sessions with children, plus one 1-hour caregiver session, delivered by four high-school educated counselors. |

| Bryant et al., (2011) | Eight 1-hour individual CBT sessions delivered by Thai psychologists, psychiatrists or nurses. | |||

| Internet CBT | n = 2 | Wagner et al. (2012); Knaevelsrud et al. (2015) | Two weekly 45-minute writing assignment over a five-week period under the Interapy Internet CBT protocol (Lange et al., 2001). Delivered by Arabic-speaking psychotherapists or psychiatrists. | |

| NET | n = 2 | Orang et al. (2018) | Ten to 12 weekly 2-hour NET sessions delivered by two psychology Master-level counselors. | |

| Hinsberger et al. (2017); Hinsberger et al. (2020); Xulu et al. (2021) | Eight 2-hour sessions every second working day using FORNET in English with interpreters by four German and two South African NET therapists. | |||

| TRT | n = 2 | Barron et al. (2013); Barron et al. (2016) | Five TRT sessions delivered by counselors in pairs with 10 adolescents per group. | |

| CETA | n = 1 | Bonilla-Escobar et al. (2018) | Twelve to 14 weekly, 1.5-hour sessions delivered by lay psychosocial community workers (who were Afro-Columbian survivors of violence themselves and recognized leaders or caregivers in their communities) without previous mental health experience and supervised by psychologists. A modular transdiagnostic psychotherapy model based on CBT for low-resource contexts for PTSD, depression, anxiety, and other comorbid problems. | |

| CPT | n = 1 | Bass et al. (2013); Kaysen et al. (2020) | Eleven weekly 2-hour group CPT with 6–8 women per group, delivered by female psychosocial assistants with at least 4 years of post-primary school education. | |

| EMDR | n = 1 | Zaghrout-Hodali et al. (2008) | 4 sessions of 1.5–2-hour group EMDR (butterfly hug protocol by Wilson et al., 2020) and a 4–5 month follow-up, delivered by two therapists. The qualifications of the therapists were not stated in the paper. Sessions were conducted at intervals of 2 days for first three sessions and increased to 2 weeks between Sessions 3 and 4. | |

| Solution-focused counseling | n = 1 | Dinmohammadi et al. (2021) | Six weekly 90-min solution-focused counseling sessions delivered by the first author who held a master’s degree in midwifery counseling. | |

| Psychological debriefing | CISM | n = 1 | Thabet et al. (2005) | Seven weekly group sessions of CISM (Mitchell & Everly, 2000) delivered by a child psychiatrist with two facilitators (social worker and psychologist). |

| Tree of life community circle | n = 1 | Mpande et al., (2013) | Three-day session with a progression of eight guided conversations held in “circles” run by counselors. | |

| Empowerment program | n = 1 | Tiwari et al. (2005) | Single 30-minute session of Empowerment protocol by Parker et al. to enhance the women’s independence and control, including safety, choice-making and problem-solving, delivered by a midwife who had a postgraduate degree in counseling. | |

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; EMDR = eye moment desensitization and reprocessing; NET = narrative exposure therapy; CPT = cognitive processing therapy; TRT = Teaching Recovery Techniques; CISM = critical incident stress management; CBT = cognitive-behavioral therapy; FORNET = Forensic Offender Rehabilitation Narrative Exposure Therapy; CETA = Common Elements Treatment Approach.

How Ongoing Threat Was Constructed

Supplemental Appendix C summarizes how ongoing threat was constructed. Out of the 15 studies, 10 studies took place in the context of ongoing political and armed violence, 2 studies in the context of ongoing community violence, 1 of which with Afro-Colombians victims of conflict and torture, and 1 with traumatized perpetrators, and 3 studies featured ongoing IPV. Most studies adopted a descriptive approach when noting the ongoing threat, which included threats such as terrorist attacks, shootings, fire, and physical and psychological abuse (e.g., Hinsberger et al. 2020; Thabet et al. 2005). Only one study examined level of ongoing threat as an independent variable (Kaysen et al., 2020), where they compared the effectiveness of CPT under high and low levels of security threat across different locality districts.

The twelve studies targeting political and community violence were categorized into the ISAC pyramid for mental health and psychosocial support in emergency situations (IASC, 2007). Less than half of the studies (46.7%) examined specialized services provided by psychiatric and psychological professionals on a 1:1 basis. The other studies evaluated group programs or interventions provided by a range of mental health specialists and nonspecialists such as lay counselors.

To report types of trauma, Supplemental Appendix D lists out the measures used. Wagner et al. (2012) and Dawson et al. (2018) described self-reported types of traumatic experiences, two studies used the Harvard Trauma questionnaire to measure refugee trauma history (Bass et al., 2013; Kaysen et al., 2020), and two studies used the Exposure to War Stressors Questionnaire (Barron et al., 2013, 2016). For studies that examined ongoing IPV, the Life Events Checklist (Orang et al., 2018), and the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS and CTS-2) were used in Tiwari et al. (2005) and Dinmohammadi et al. (2021), respectively.

Methodological Quality and Threats to Validity

According to the MMAT (Hong et al., 2018), calculation of an overall score from the ratings of each criterion is discouraged. Instead, it is suggested that a description of the ratings of each criterion is provided to show the quality of the included studies. Supplemental Appendix E details the quality appraisal assessment of each study using MMAT. Threats to the validity of the evidence are included below.

Measures such as the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire and PTSD Symptom Scale were validated in developing countries and in different contexts, but other measures were not previously validated in the particular region of the studies (e.g., Barron et al., 2013; Dawson et al., 2018). Some subscales of measures (e.g., Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire) showed low reliability and had to be discarded in one study (Barron et al., 2013).

Two studies explicitly identified a lack of power due to early termination of the study because of an unstable political situation (Bryant et al., 2011; Dawson et al., 2018). Among the six studies comparing a trauma-focused intervention to another therapy, two used the same set of therapists for both intervention arms (Dawson et al. 2018; Mpande et al., 2013) which may have led to therapist drift, affecting the fidelity of the interventions. These, along with nine other studies, did not describe therapist fidelity to the interventions. In Dawson et al. (2018), the trauma-focused CBT intervention claimed by the authors blended therapeutic modalities including prolonged exposure and elements of NET, as part of the adaptation of treatment. Cluster randomization and counselor-based randomization (Bass et al., 2013; Barron et al., 2013, 2016) affected the characteristics and sizes of the groups. Eight out of thirteen studies with comparison groups (58.3%) reported unequal group sizes or baseline characteristics.

Effectiveness: Intervention Design and Outcomes

Supplemental Appendix F shows the study’s key findings and effect sizes. Cohen’s d effect size was used to indicate strength of intervention benefits or harms across interventions. Of the 13 studies with controlled group(s) design, 4 studies had an active therapeutic control group (i.e., another form of therapy) only without waitlist control, 7 studies had a passive waitlist or non-psychological support control group, 1 study had an active therapeutic control plus a passive control group, and 1 study had an active psychoeducation group and a passive control group. The calculation of dropout/treatment completion was not uniform (across different timepoints, questionnaire completion versus treatment completion). When examining treatment completion rate, it ranged from 37.5 to 100% (n = 14, median 91.2%), with the internet intervention studies having the lowest completion rates. All participants in the included study experienced at least one traumatic event and had elevated levels of trauma-related symptoms. However, not all participants reached clinical diagnostic threshold for PTSD.

Ongoing Socio-Political Conflict Caused by Organized Violence

Children

Four studies examined traumatized 7- to 15-year-old children. Three took place in the Occupied Palestine Territories (Barron et al., 2013, 2016; Thabet et al., 2005), and the other took place in Aceh, Indonesia (Dawson et al., 2018). In an adapted CBT intervention called TRT, when compared to waitlist controls, two classroom RCTs found significant effects of the TRT intervention on PTSD outcome (Barron et al., 2013, 2016). In terms of secondary outcomes, one found TRT significantly reduced depression and traumatic grief (Barron et al., 2013), whereas the other did not find significant effect on depression or dissociative experience (Barron et al., 2016). Nevertheless, in a non-RCT where children were allocated to CISM, psychoeducation and control groups, researchers found nonsignificant effect of CISM when compared to the other two groups on posttraumatic stress and depression outcomes (Thabet et al., 2005). When compared to another active treatment, in the RCT by Dawson et al. (2018) who compared the effectiveness of trauma-focused CBT to problem-solving therapy, although large effect size was found within the treatment intervention on PTSD, the between-group effect sizes on PTSD, depression, and anger were small and statistically nonsignificant for both child self-report and caregiver-report outcomes.

However, these results need to be interpreted with caution due to the methodological problems of these studies. Group sizes were unequal in Barron et al. (2013) and Thabet et al. (2005). Baseline characteristics differed across groups in Barron et al. (2013, 2016). There was a significantly higher level of posttraumatic stress (PTS) and mental health difficulties in the intervention group in Barron et al. (2013), and a significantly higher exposure to war stressors in the waitlist group for females in Barron et al. (2016). In terms of measures used, Thabet et al. (2005) adopted a measure of PTSD based on DSM-IIIR rather than DSM-IV, the diagnostic manual used at the time of the study. Dawson et al. (2018) indicated that the measures used were not validated in the local population. Moreover, the RCT by Dawson et al. (2018) was not 80% powered due to early termination, and there might be allegiance bias as the study used the same therapists for both active treatment conditions.

Adults

Cognitive-behavioral therapy

Four studies on adult trauma under ongoing political violence used various forms of CBT as the treatment modality. Bryant et al. (2011) compared CBT with supportive counseling among Thai individuals with PTSD after exposure to terrorism. Large effect size was found between groups for PTS though effect size was moderate at 3-month follow-up. However, for depression and grief, although there were moderate to large effect sizes post-intervention, the effect sizes were small at follow-up. Wagner et al. (2012) described a pilot case series of the RCT by Knavealud et al. (2015) on internet CBT for traumatized individuals in Iraq, compared with waitlist control. At post-intervention, large, controlled effect sizes were found for PTS, depression, anxiety and quality of life, and moderate controlled effect size was found for somatization (Knaevelsrud et al., 2015). However, the results from Bonilla-Escobar et al. (2018) showed a more complicated picture. They used an adapted CBT called CETA among Afro-Colombian victims of conflict and torture in two cities with ongoing community violence and armed conflict. CETA is a modular intervention where psychosocial workers can choose the order and dosing (number of sessions per element) of the components. These include encouraging participation, psychoeducation, cognitive coping, gradual exposure of trauma memories, cognitive processing, safety planning, relaxation, behavioral activation, and gradual in vivo exposure. Divergent results between two municipalities were found moderate to large, controlled effect sizes for PTS, depression, anxiety, and functional impairment in Buenaventura but nonsignificant and small effect sizes in Quibdo.

Several quality concerns were found. One study was only 50% powered due to early termination in Bryant et al. (2011), and the dropout rate was high (around 41%) in Knaevelsrud et al. (2015). In Bonilla-Escobar et al. (2018), the traumatic experiences were significantly higher in the CETA than control group in Buenaventura, whereas in Quibdo, the total mental health symptoms were higher in the control group. Furthermore, although the authors claimed that the culturally adapted outcome measure used has undergone validation, there was no justification for how the clinical cut-off score was determined.

Narrative exposure therapy

The three studies included that used NET for community trauma were all based on one trial (Hinsburger et al., 2017, 2020; Xulu et al., 2021). They used the Forensic Offender Rehabilitation Narrative Exposure Therapy (FORNET) which focused on reducing trauma symptoms as well as aggressive behaviors among traumatized ex-offenders in South Africa. In FORNET, narrative exposure includes not only the traumatic events but also perpetrated acts of violence. The trial results revealed a significant reduction of PTSD outcomes in FORNET group when compared to a non-trauma-focused CBT (meaning no trauma exposure) as well as a waitlist control. Controlled effect sizes on posttraumatic stress when compared to waitlist control was large at seven to 11-month follow-up. The large within-group effect size for FORNET was sustained at 15 to 20 months post-intervention. However, there was no significant difference for the number of perpetrated events or appetitive aggression post-intervention across all groups. Taking methodological quality into consideration, it seems that the study was not well-powered, with small sample size in the FORNET and CBT conditions and unequal group sizes. Those in the CBT group also were older than people in the other groups. Another confounding variable was that people in the treatment conditions were involved in another reintegration program prior to taking part in the trial when compared to those on the waiting list, which could potentially affect the intervention effect.

Cognitive processing therapy

One cluster-RCT (two studies) examined the use of group CPT among female sexual violence survivor in the context of ongoing political violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Bass et al., 2013; Kaysen et al., 2020). They found a significant reduction of PTSD symptoms, depression, and anxiety, as well as functional impairment. Secondary, separate efficacy analyses compared geographical regions, which were classified as high insecurity and low insecurity by the psychosocial supervisors (Kaysen et al., 2020). There was a higher attendance rate in the higher insecurity regions. A significant interaction between site security and session was found in the model where the authors claimed that by visual inspection of the slope of the session-by-session change in symptom score, people in regions of high security risks had a more rapid improvement than people in regions with lower risks. This conclusion is not well-supported by the data. The measure of setting-level insecurity (high/low insecurity) was a subjective judgment of the respective regional supervisors, and the outcome measure used was not a validated scale in itself.

Non-CBT interventions

The Tree of Life healing circle (TOL) was compared with a control intervention called psychoeducation and coping skills workshop (PACS) in a quasi-experimental group design (Mpande et al., 2013) that targeted people experiencing ongoing political and community violence in Zimbabwe. It was a nonrandomized, nonequivalent group study, where participants were allocated based on regions to avoid “contamination” of the findings as community members in the same region might disclose the intervention details to others. They found reduction of distress with large effect sizes in a locally devised and validated measure of distress, but small to moderate increases in quality-of-life measure. However, the effects between groups seemed to be comparable, and slightly larger effect sizes were seen in the PACS group. There were several confounds which potentially biased the findings, one being a higher baseline family problems and stressful life events in the TOL group, and the possibility of allegiance effect/therapist drift as they had the same set of facilitators across the two interventions.

The evidence on EMDR was inconclusive as only one case series (Zaghrout-Hodali et al., 2008) met our inclusion criteria. The researchers used this intervention in group setting and there was no statistical analysis or validated measure to indicate treatment outcome apart from an analog scale (subjective unit of distress) and qualitative feedback.

Ongoing IPV

Orang et al. (2018) used an RCT to examine women who were living with abusive partners in Iran. The results revealed small effect sizes of NET on PTS and depression measures when compared to treatment as usual which was sustained at 6-month follow-up. Nonsignificant results were found for secondary measures such as daily functioning. Methodological issues limiting the certainty of the findings included a relatively small sample size (n = 45) and a higher perceived stress scale in the NET group at baseline as a potential confound.

Two other RCTs examined solution-focused counseling (Dinmohammadi et al., 2021) and a one-off 30-minute empowerment session (Tiwari et al., 2005) for pregnant females experiencing ongoing IPV. However, the two studies did not focus on traumatic stress but instead focused on general quality of life and mental health as secondary outcome (primary outcome being the number of abusive events). Effect sizes were not reported, although Dinmohammadi et al. (2021) found significant improvement in general quality of life and mental health when compared to a control group, whereas in Tiwari et al. (2005), there was no change on the mental health subscale. Tiwari et al. (2005) commented that at post-intervention, more women in the control group experienced depression. Yet, there was insufficient reporting of baseline depression across the two groups and hence no conclusion on the effect of mood could be drawn. The primary outcomes of both studies were number of abusive events rather than well-being-related outcomes.

Feasibility: Treatment Models, Adaptations, and Challenges

Studies described practical challenges due to the ongoing threat (Table 4). Two studies (Bryant et al., 2011; Dawson et al., 2018) had to terminate recruitment prematurely due to ongoing attacks, and local authority being suspicious of the study. One study described challenges due to counselors dropping out because of personal trauma (Barron et al., 2016). Another study’s research team could not travel to the country due to security and safety concern (Wagner et al., 2012).

Table 4.

Feasibility, Challenges, and Treatment Adaptations.

| Author/s (year) | Adaptations Related to Culture, Context, and Ongoing Threat | Challenges Due to the Ongoing Threat |

|---|---|---|

| Bryant et al. (2011) | Thai meditation techniques encouraged rather than simply focusing on Western methods of relaxation. Modifying cognitive restructuring to recognize the realistic threats of possible terrorist attacks, to accept a level of risk to allow everyday activities such as buying food in the local market. |

Recruitment to the study was terminated prematurely due to increased terrorist attacks and health workers being targeted. |

| Hinsberger et al. (2017, 2020) | Added content on engaging in violence, exposure sessions were extended to include perpetrator events. Abandoned the narration element to facilitate participants’ trusts and openness. |

— |

| Bonilla-Escobar et al. (2018) | In Buenaventura, most surveys were conducted in a local church for security reasons. | — |

| Wagner et al. (2012); Knaevelsrud et al. (2015) | Treatment duration was set up to be longer than the original protocol. Most participants did not finish their treatment, took almost twice as long (on average 12 weeks) compared to participants in a Western context to complete treatment. More directive therapeutic stance as the healthcare professionals were seen as authoritative who gave expert advice in their culture. Refusal to give explicit advice might be seen as incompetence or indecisiveness. Participants were explicitly asked not to mention names of places or people to increase trust as some were worried about the risk of political infiltration and confidentiality of the data (worry that the website may be supported by intelligence agencies). Use of quotes and metaphors from the Koran by the therapists. |

Research coordinators could not travel to Iraq due to security concerns. |

| Dawson et al. (2018) | Elements of prolonged exposure therapy were used including the construction of a chronological narrative of the children’s life. The narrative component also reviewed historical elements such as family’s history, wider community and province to help understand the context of the traumatic events they experienced in their life. | The study was terminated prematurely due to local authorities shutting the study down, as the political unrest caused suspicion of Western activities in the region. The researchers were forced to leave the region. |

| Barron et al. (2013) | — | Counselor dropout in the study due to self-reported trauma, highlighting the challenge of conducting research in war zones |

| Barron et al. (2016) | — | — |

| Bass et al. (2013); Kaysen et al. (2020) | A psychoeducation session addressing how beliefs about sexual assault impact on women’s social status. Simplifying the jargons, use of verbal and pictorial rather than handwritten assignments due to high rate of illiteracy. Removal of two behavioral assignments to focus on the cognitive elements of the treatment. Adapting the language to Swahili and the therapy was named “mind and heart therapy” rather than CPT. | — |

| Zaghrout-Hodali et al. (2008) | Did not include elicitation of positive and negative cognitions, nor a validity of cognition rating scale or body scan unlike the original protocol, however, did not explain reasoning behind this. | — |

| Thabet et al. (2005) | The authors stated the intervention was adjusted to the ongoing political conflict context but did not further elaborate. | — |

| Mpande et al. (2013) | — | — |

| Orang et al. (2018) | Participation kept secret from partners. Allocated one to two sessions to work on issues related to safety, such as encouragement to seek help from police, lawyers, coping skills, safety planning, and human rights education. A short discussion of IPV occurrence in the past week at the beginning of each session to gauge readiness for the narrative exposure. |

— |

| Dinmohammadi et al. (2021) | — | — |

| Tiwari et al. (2005) | Participation was kept secret from partners. The research team suggested the women might establish a code with trusted friends and neighbors. |

Note. CPT = cognitive processing therapy; IPV = intimate partner violence.

In terms of modifications, in the context of political and community violence, adaptations for ongoing threat and cultural context were described in eight studies, but only seven of which described what the adaptations were. Culturally-specific interventions were included such as Thai meditation techniques (Bryant et al., 2011) and the use of metaphors from the Koran (Wagner et al., 2012; Knaevelsrud et al., 2015). To adapt for the ongoing threat context, one study included narrative exposure of the significant events in the community or province, in addition to narrating the personal life events (Dawson et al., 2018), and another study modified the cognitive restructuring element to factor in realistic threats (Bryant et al., 2011). To build trust, as some participants worried about political infiltration (Wagner et al., 2012), names and places were omitted in the written narratives, while another trial abandoned the narrative component (Hinsberger et al., 2017, 2020). For ongoing IPV, study participants (Tiwari et al., 2005; Orang et al., 2018) hid their participation from their partners. Orang et al. (2018) also included a safety planning session which focused on coping skills and human rights education. They checked in at the beginning of each narrative exposure session in relation to IPV occurrence to gauge readiness for the exposure.

Discussion

This systematic review sought to examine the effectiveness and feasibility of psychological interventions where the threat of ongoing traumatic events continued. The quality of reviewed research was poor, mostly due to the practical circumstances it was conducted in. Nevertheless, there was evidence of moderate to large effect sizes relative to waitlist controls for PTSD-related outcomes, with weaker evidence against active controls. For secondary outcomes, although large effect sizes were found in some studies examining depression and anxiety, these effect sizes became small to moderate at follow-ups. There were no significant effects on outcomes in studies that examined aggression and dissociation. There was also evidence for the feasibility of treatment and its application by nonspecialists. A summary of critical findings is in Table 5.

Table 5.

Critical Findings of This Review.

| Topic | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|

| Location | Studies were conducted in ten locations, which meant that this might not be representative of other regions with individuals experiencing ongoing threat. |

| Effectiveness | Most studies demonstrated effectiveness for posttraumatic stress-related outcomes in at least one of the treatment arms. Effect sizes were moderate to large when compared to waitlist but less clear when compared to active treatments. There was stronger evidence for CBT-based interventions. For secondary outcomes such as depression and anxiety, smaller effect sizes were found especially at follow-ups. |

| Feasibility | Most studies were feasible to implement and able to retain participants despite the unstable contexts. Task-shifting (use of nonspecialists) was feasible with having community members as therapists delivering interventions under supervision. |

Note. CBT = cognitive-behavioral therapy.

The conclusions of the present review are in line with those of Ennis et al. (2021) but with broader research questions and intervention modalities. The current findings go beyond Ennis et al.’s review of effectiveness of trauma-focused CBT. Specifically, this review adds evidence for the effectiveness of non-CBT interventions, secondary outcomes, and intervention feasibility. We used a broader definition of distress and stricter criteria of ongoing threat. For non-CBT studies, the three studies on Tree of Life, CISM, and group EMDR demonstrated less robust evidence and the data were less supportive of their effectiveness. We did not find any individual EMDR study from our search. Although a recent systemic review on group EMDR of adult and children populations for a range of mental health difficulties found promising results of this intervention (Kaptan et al., 2021), we cannot draw conclusions about its effectiveness in settings with ongoing threat, as the included group EMDR case series was based on analogue scales and qualitative feedback only.

Consistent with the argument from Keynejad et al. (2020) in their systematic review and meta-analysis on treating survivors of IPV in low-resource settings, many studies failed to differentiate ongoing versus past trauma. Hence, we only included studies which evidenced that the survivors experienced ongoing trauma such as living with the abusive partners, unlike that of Ennis et al. (2021). Based on our criteria, methodological issues have limited the strength of the evidence in psychological treatments for ongoing IPV. One study found a small to moderate effect sizes on traumatic stress and depression of NET when compared to treatment as usual sustained at follow-up (Orang et al., 2018). For non-trauma-focused interventions, one study demonstrated effectiveness using a solution-focused counseling approach on improving quality of life of pregnant abused women (Dinmohammadi et al., 2021), whereas the one-off empowerment program is likely not effective in terms of mental health (Tiwari et al., 2005).

Promising evidence was noted for feasibility and scalability in low-resource settings where conflicts were ongoing. Studies applied practical, contextual, and cultural adaptations, and upskilled community members in task-shifting, as more than half of the included interventions were conducted by lay counselors. Most participants were able to attend the sessions. This challenges common assumptions that psychological interventions are impossible in ongoing threat contexts. That said, some feasibility challenges remain, for example, local government disallowing research teams to conduct studies, forcing studies to be terminated (Bryant et al., 2011; Dawson et al., 2018), and fear of political infiltration which negatively affected participants’ trust and subsequent participation in the study (Knaevelsrud et al., 2015; Mpande et al., 2013; Wagner et al., 2012). While existing systemic reviews tend to focus on specific types of interventions, future reviews should closely consider the political and cultural context. Confidentiality around accessing therapy was particularly important in studies on IPV, and whether safety could be ensured for the women to attend. It appears that the included studies successfully maintained privacy and confidentiality, therefore making the interventions feasible.

Clinical Implications

Table 6 summarizes the clinical, research, and policy implications. This review suggests that psychological interventions for trauma-related difficulties do not cause harm, are feasible for populations under ongoing threat, and are most likely beneficial. The assumption that we should not offer psychological interventions in these settings is therefore not supported by the findings of this review. There was no evidence that suggested psychological interventions for those experiencing trauma were harmful.

Table 6.

Implications for Practice, Research, and Policy.

| Area | Implication |

|---|---|

| Practice | Psychological interventions in areas of ongoing threat appear feasible and likely beneficial in practice. Cultural adaptations appear feasible and should be included in practice such as incorporating local meditation techniques and religious texts, community narratives, and paying attention to somatization. Adaptations to address safety appear essential and should be included in settings of ongoing threat. |

| Research | Future research could explore and compare exposure-based and present-focused interventions, so we can better establish which interventions are best for whom. |

| Future studies could better conceptualize ongoing threat and use possible objective measurements and looking at how the level of ongoing threat impacts on the effectiveness and feasibility of the interventions. | |

| Policy | Our research recommends that policies should advise continued research into and practice of psychological interventions in context of ongoing threat. However, more research is needed before policies or guidelines can suggest any specific intervention method. |

Regarding cultural adaptation, studies should consider incorporating cultural elements and knowledge in treatments. Examples from the current review include integrating religious texts (Knaevelsrud et al., 2015; Wagner et al., 2012) and adopting indigenous meditation techniques (Bryant et al., 2011). An added benefit of training community workers as therapists is that they likely have more cultural knowledge about the regions and more culturally-specific manifestations of traumatic symptoms such as somatization, although supervisors would need to pay attention to the community workers’ well-being and personal trauma as they are likely to be exposed to the same ongoing trauma. It may be helpful to screen these lay therapists for traumatic stress symptoms as a safeguarding measure.

The ongoing nature of the trauma might lead to characteristics and responses different from the diagnostic criteria of PTSD in the DSM-5 (APA, 2013) and ICD-11 (World Health Organization, 2019). These populations might be more preoccupied with the present safety and anticipated danger rather than past index trauma (Nuttman-Shwartz & Shoval-Zuckerman, 2016). From the synthesis, it is still uncertain whether certain trauma-focused interventions or present-focused interventions are superior to others, or whether there would be synergistic effects if components from different treatments are used. Contrary to authors discussing CTS who did not advocate for exposure-based treatments for individuals under ongoing threat (Diamond et al., 2010; Eagle & Kaminer, 2013), the majority of the included interventions were exposure-based, such as trauma-focused CBT and NET, and showed benefits. This echoes Coventry et al.’s (2020) network meta-analysis findings that multicomponent interventions (included imaginal exposure and cognitive restructuring) were most effective for reducing trauma symptoms in refugees, veterans, childhood sexual abuse, or IPV survivors. Safety planning was mentioned in Orang et al. (2018) and seen as helpful, but not in other studies. Across the studies, descriptions about specific treatment adaptations to ongoing threat situations were limited.

Research Implications

While the controversy of advisability, effectiveness, and feasibility of psychological intervention for people in ongoing threat settings is still ongoing, it is important to operationalize the construct of ongoing threat so distinct conclusions can be drawn. In the included studies, ongoing threat was largely descriptive with a lack of objective measurement. For example, some studies simply mentioned “ongoing threat situation,” whereas the Life Events Checklist was used in other studies as a measure of trauma exposure. During the screening process, some studies did not specify if threat was ongoing or recent but ceased, which were not included in this review (Greene et al., 2021). Future studies should detail the extent of past and ongoing (re)exposure throughout the study period, to facilitate a richer understanding of the unique nature of ongoing threat in relation to people’s psychological responses in these contexts. Goral et al. (2021) devised a measure of “ongoing traumatic response” which could be used in future studies. They found that, unlike PTSD symptoms, CTS symptom severity was not significantly associated with level of exposure to trauma. The symptoms included reduced sense of safety, trust, and mental exhaustion, change in sense of self such as feelings of emptiness, hopelessness, and estrangement. Of the reviewed studies, none measured these responses. Future studies could include these constructs, to explore how these may be similar or different from complex PTSD and subsequently guide treatments.

At present, the discussion of whether psychological treatment for trauma should be offered when significant threat remains is informed only by the inference, which can be drawn from the present review and others, that treatment may be effective under such conditions. Future research should employ more diverse and rigorous methodologies in addition to using active and waitlist control to ascertain the effectiveness of both CBT and non-CBT interventions. For example, future studies could conceptualize the level and nature of ongoing threat as a mediator or moderator using psychometrically validated measures. Clearly it is essential to evaluate the same treatment in groups where threat is continued or not (such as ongoing IPV vs. historical IPV), alongside a control. This might be especially important as the differential findings across the two municipalities among Afro-Colombians survivors of torture and conflict might mean that intervention effective in one setting may not be generalized to another (Bonilla-Escobar et al., 2018). They argued that the nature of ongoing threat in the two regions possibly affected treatment effectiveness. This hypothesis would be useful to explore in future studies. As a result of the ongoing threat situation, research should document safety and security concerns to the research team and the mitigations/precautions adopted.

Group interventions in particular could address the individual exposure to the traumatic events versus collective exposure (Giacaman et al., 2007) and using community-based approaches, such as the new NETFact community intervention (Robjant et al., 2020).

Most outcome reporting was limited to distress relating to trauma, depression and anxiety, and only Hinsberger et al. (2017, 2020) included outcomes on somatization, a culturally-sensitive construct found in these populations (Hinton & Lewis-Fernández, 2011), which future studies could include. Given the inconsistent and variable quality of the studies, future studies could use standardized checklists such as TIDieR checklist (Hoffmann et al., 2014) and adhere to World Health Organization Mental Health Gap Action Programme guidelines (Keynejad et al., 2021) when designing and evaluating interventions.

Limitations and Diversity

The current studies include a diverse range of ages and genders. Participants were mostly from the geographical south, non-White, and from lower socioeconomic status, as these factors are correlated with areas of ongoing threat. Culture was particularly considered as a relevant factor for adaptations and to increase feasibility. Future studies could examine how other factors of diversity impact effectiveness and feasibility such as adaptations related to gender, age, or religion. Nevertheless, we are mindful of locations and communities with ongoing conflict that were not represented in the included studies. For example, the concept of CTS is used mostly in South Africa and Israel, but it is uncertain how this can be generalized and conceptualized in other regions. The review only included articles written in English which means we might have missed studies in other languages. The search strategy using only three databases and citation searching could be considered, where future studies could improve upon this by including more databases.

The definition of ongoing conflict could also be arbitrary. Some regions might officially have a ceasefire, yet conflicts between armed groups or civilians might still be occurring. Despite promising results of feasibility, our understanding based on the published studies might be biased as other regions with ongoing threat might not be researched, the situation might be too unstable for research, or negative results might not be published. There might also be differences in psychological needs at situations of acute threat versus prolonged ongoing threat. This review only included specialist interventions and targeted interventions. However, in areas of active conflict, other psychosocial interventions and community approaches are useful for meeting basic needs and achieving primary/secondary prevention which are not included in the review. Due to the limited number of studies found, we did not analyze the effectiveness between those delivered by specialists and nonspecialists.

Although the quantity and quality of studies does not yet let us draw firm conclusions, this does not negate the importance of the research question and of this review, which we hope other researchers will build on. This study complements the earlier review by Ennis et al. (2021) as we employed slightly different inclusion/exclusion criteria of ongoing threat and intervention modalities, as well as added discussion on feasibility. The current pre-registered review and synthesis also yields different clinical and research implications to advance the field. A stronger argument can be made with the non-overlapping studies we identified: asking whether interventions during ongoing threat are effective and feasible means we are paying attention to ongoing humanitarian crises and not withholding help, based on untested assumptions, to those who may need it the most. Building culturally-sensitive, evidence-based psychological interventions during ongoing threat can 1 day ease suffering, prevent re-traumatization, and start earlier healing in marginalized populations.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tva-10.1177_15248380231156198 for The Effectiveness and Feasibility of Psychological Interventions for Populations Under Ongoing Threat: A Systematic Review by See Heng Yim, Hjördis Lorenz and Paul Salkovskis in Trauma, Violence, & Abuse

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Francesca Brady for commenting on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Author Biographies

See Heng Yim (DClinPsych) is a clinical psychologist with PhD in clinical psychology at the Oxford Institute of Clinical Psychology Training. She is interested in community psychology, health inequalities, and the effectiveness of psychological interventions for marginalized populations including asylum-seekers, refugees, and survivors of human trafficking.

Hjördis Lorenz (PhD) is a doctoral candidate in clinical psychology at the Oxford Institute of Clinical Psychology Training. Prior to this, she completed a PhD in experimental psychology at the University of Oxford, focusing on well-being and PTSD prevention in student paramedics. She is interested in improving PTSD treatment and prevention for populations at high risk for PTSD through research and practice.

Paul Salkovskis (PhD) is the director of the Oxford Institute of Clinical Psychology Training and the Oxford Centre for Psychological Health, Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Oxford, and the Clinical Director of a Specialist Psychological Interventions Clinic. He has a long-standing career and publication record focused on the understanding and treatment of anxiety disorders including PTSD.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: See Heng Yim  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2241-1017

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2241-1017

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Reference

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI]

- American Psychological Association (APA). (2017). Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in adults. https://www.apa.org/about/offices/directorates/guidelines/ptsd.pdf.

- Barron I., Abdallah G., Heltne U. (2016). Randomized control trial of teaching recovery techniques in rural occupied palestine: Effect on adolescent dissociation. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 25(9), 955–973. 10.1080/10926771.2016.1231149 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barron I. G., Abdallah G., Smith P. (2013). Randomized control trial of a CBT trauma recovery program in Palestinian schools. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 18(4), 306–321. 10.1080/15325024.2012.688712 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bass J. K., Annan J., McIvor Murray S., Kaysen D., Griffiths S., Cetinoglu T., Wachter K., Murray L. K., Bolton P. A. (2013). Controlled trial of psychotherapy for congolese survivors of sexual violence. New England Journal of Medicine, 368(23), 2182–2191. 10.1056/NEJMoa1211853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Escobar F. J., Fandiño-Losada A., Martínez-Buitrago D. M., Santaella-Tenorio J., Tobón-García D., Muñoz-Morales E. J., Escobar-Roldán I. D., Babcock L., Duarte-Davidson E., Bass J. K., Murray L. K., Dorsey S., Gutierrez-Martinez M. I., Bolton P. (2018). A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral intervention for Afro-descendants’ survivors of systemic violence in Colombia. PLOS One, 13(12), e0208483. 10.1371/journal.pone.0208483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen D. J., Kreuter M., Spring B., Cofta-Woerpel L., Linnan L., Weiner D., Bakken S., Kaplan C. P., Squiers L., Fabrizio C., Fernandez M. (2009). How we design feasibility studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(5), 452–457. 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson R. C., Colditz G. A., Proctor E. K. (2012). Dissemination and implementation research in health. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant R. A., Ekasawin S., Chakrabhand S., Suwanmitri S., Duangchun O., Chantaluckwong T. (2011). A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of cognitive behavior therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in terrorist-affected people in Thailand. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 10(3), 205–209. 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00058.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coventry P. A., Meader N., Melton H., Temple M., Dale H., Wright K., Cloitre M., Karatzias T., Bisson J., Roberts N. P., Brown J. V. E., Barbui C., Churchill R., Lovell K., McMillan D., Gilbody S. (2020). Psychological and pharmacological interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental health problems following complex traumatic events: Systematic review and component network meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 17(8), e1003262. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo M., Arinero M. (2010). Assessment of the efficacy of a psychological treatment for women victims of violence by their intimate male partner. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13(2), 849–863. 10.1017/s113874160000250x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson K., Joscelyne A., Meijer C., Steel Z., Silove D., Bryant R. A. (2018). A controlled trial of trauma-focused therapy versus problem-solving in Islamic children affected by civil conflict and disaster in Aceh, Indonesia. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(3), 253–261. 10.1177/0004867417714333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond G. M., Lipsitz J. D., Fajerman Z., Rozenblat O. (2010). Ongoing traumatic stress response (OTSR) in Sderot, Israel. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 41(1), 19–25. 10.1037/a0017098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinmohammadi S., Dadashi M., Ahmadnia E., Janani L., Kharaghani R. (2021). The effect of solution-focused counseling on violence rate and quality of life of pregnant women at risk of domestic violence: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21(1), 221. 10.1186/s12884-021-03674-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle G., Kaminer D. (2013). Continuous traumatic stress: Expanding the lexicon of traumatic stress. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 19(2), 85–99. 10.1037/a0032485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A., Clark D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(4), 319–345. 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis N., Shorer S., Shoval-Zuckerman Y., Freedman S., Monson C. M., Dekel R. (2020). Treating posttraumatic stress disorder across cultures: A systematic review of cultural adaptations of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapies. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 587–611. 10.1002/jclp.22909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis N., Sijercic I., Monson C. M. (2021). Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder under ongoing threat: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 88, 102049. 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacaman R., Shannon H. S., Saab H., Arya N., Boyce W. (2007). Individual and collective exposure to political violence: Palestinian adolescents coping with conflict. European Journal of Public Health, 17(4), 361–368. 10.1093/eurpub/ckl260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie K., Duffy M., Hackmann A., Clark D. M. (2002). Community based cognitive therapy in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder following the Omagh bomb. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(4), 345–357. 10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00004-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goral A., Feder-Bubis P., Lahad M., Galea S., O’Rourke N., Aharonson-Daniel L. (2021). Development and validation of the Continuous Traumatic Stress Response scale (CTSR) among adults exposed to ongoing security threats. PLOS One, 16(5), e0251724. 10.1371/journal.pone.0251724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg N., Langston V., Everitt B., Iversen A., Fear N. T., Jones N., Wessely S. (2010). A cluster randomized controlled trial to determine the efficacy of Trauma Risk Management (TRiM) in a military population. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(4), 430–436. 10.1002/jts.20538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene M. C., Likindikoki S., Rees S., Bonz A., Kaysen D., Misinzo L., Njau T., Kiluwa S., Turner R., Ventevogel P., Mbwambo J. K. K., Tol W. A. (2021). Evaluation of an integrated intervention to reduce psychological distress and intimate partner violence in refugees: Results from the Nguvu cluster randomized feasibility trial. PLOS One, 16(6), e0252982. 10.1371/journal.pone.0252982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinsberger M., Holtzhausen L., Sommer J., Kaminer D., Elbert T., Seedat S., Augsburger M., Schauer M., Weierstall R. (2020). Long-term effects of psychotherapy in a context of continuous community and gang violence: Changes in aggressive attitude in high-risk South African adolescents. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 48(1), 1–13. 10.1017/S1352465819000365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinsberger M., Holtzhausen L., Sommer J., Kaminer D., Elbert T., Seedat S., Wilker S., Crombach A., Weierstall R. (2017). Feasibility and effectiveness of narrative exposure therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy in a context of ongoing violence in South Africa. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 9(3), 282–291. 10.1037/tra0000197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton D. E., Lewis-Fernández R. (2011). The cross-cultural validity of posttraumatic stress disorder: Implications for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety, 28(9), 783–801. 10.1002/da.20753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann T. C., Glasziou P. P., Boutron I., Milne R., Perera R., Moher D., Altman D. G., Barbour V., Macdonald H., Johnston M., Lamb S. E., Dixon-Woods M., McCulloch P., Wyatt J. C., Chan A.-W., Michie S. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 348, g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Q. N., Fàbregues S., Bartlett G., Boardman F., Cargo M., Dagenais P., Gagnon M.-P., Griffiths F., Nicolau B., O’Cathain A., Rousseau M.-C., Vedel I., Pluye P. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. 10.3233/EFI-180221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Q. N., Pluye P., Fàbregues S., Bartlett G., Boardman F., Cargo M., Dagenais P., Gagnon M.-P., Griffiths F., Nicolau B., O’Cathain A., Rousseau M.-C., Vedel I. (2019). Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: A modified e-Delphi study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 111, 49–59.e1. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) (2007). IASC Guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. IASC. https://www.who.int/mental_health/emergencies/guidelines_iasc_mental_health_psychosocial_june_2007.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. M., Zlotnick C., Perez S. (2011). Cognitive behavioral treatment of PTSD in residents of battered women’s shelters: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(4), 542–551. 10.1037/a0023822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaptan S. K., Dursun B. O., Knowles M., Husain N., Varese F. (2021). Group eye movement desensitization and reprocessing interventions in adults and children: A systematic review of randomized and nonrandomized trials. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 28(4), 784–806. 10.1002/cpp.2549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D., Stappenbeck C. A., Carroll H., Fukunaga R., Robinette K., Dworkin E. R., Murray S. M., Tol W. A., Annan J., Bolton P., Bass J. (2020). Impact of setting insecurity on Cognitive Processing Therapy implementation and outcomes in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1735162. 10.1080/20008198.2020.1735162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keynejad R. C., Hanlon C., Howard L. M. (2020). Psychological interventions for common mental disorders in women experiencing intimate partner violence in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(2), 173–190. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30510-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keynejad R., Spagnolo J., Thornicroft G. (2021). WHO mental health gap action programme (mhGAP) intervention guide: Updated systematic review on evidence and impact. Evidence Based Mental Health, 24(3), 124. 10.1136/ebmental-2021-300254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaevelsrud C., Brand J., Lange A., Ruwaard J., Wagner B. (2015). Web-based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in war-traumatized Arab patients: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(3), e71. 10.2196/jmir.3582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K. E., Rasmussen A. (2010). War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: Bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Conflict, Violence, and Health, 70(1), 7–16. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J. T., Everly Jr. G. S. (2000). Critical incident stress management and critical incident stress debriefings: Evolutions, effects and outcomes. Psychological Debriefing: Theory, Practice and Evidence., 71–90. 10.1017/CBO9780511570148.006 [DOI]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mpande E., Higson-Smith C., Chimatira R. J., Kadaira A., Mashonganyika J., Ncube Q. M., Ngwenya S., Vinson G., Wild R., Ziwoni N. (2013). Community intervention during ongoing political violence: What is possible? What works? Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 19(2), 196–208. 10.1037/a0032529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z., Barker T., Stern C., Pollock D., Ross-White A., Klugar M., Wiechula R., Aromataris E., Shamseer L. (2021). Should I include studies from “predatory” journals in a systematic review? Interim guidance for systematic reviewers. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 19(8), 1915–1923. https://journals.lww.com/jbisrir/Fulltext/2021/08000/Should_I_include_studies_from__predatory__journals.5.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L. K., Cohen J. A., Mannarino A. P. (2013). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for youth who experience continuous traumatic exposure. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 19(2), 180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L. K., Tol W., Jordans M., Zangana G. S., Amin A. M., Bolton P., Bass J., Bonilla-Escobar F. J., Thornicroft G. (2014). Dissemination and implementation of evidence based, mental health interventions in post conflict, low resource settings. Intervention (Amstelveen, Netherlands), 12(Suppl 1), 94–112. 10.1097/WTF.0000000000000070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttman-Shwartz O., Shoval-Zuckerman Y. (2016). Continuous traumatic situations in the face of ongoing political violence: The relationship between CTS and PTSD. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17(5), 562–570. 10.1177/1524838015585316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]