Abstract

Background:

Despite initial response to platinum-based chemotherapy and PARP inhibitor therapy (PARPi), nearly all recurrent high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSC) will acquire lethal drug resistance; indeed, ~15% of individuals have de novo platinum-refractory disease.

Objectives:

To determine the potential of anti-microtubule agent (AMA) therapy (paclitaxel, vinorelbine and eribulin) in platinum-resistant or refractory (PRR) HGSC by assessing response in patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models of HGSC.

Design and methods:

Of 13 PRR HGSC PDX, six were primary PRR, derived from chemotherapy-naïve samples (one was BRCA2 mutant) and seven were from samples obtained following chemotherapy treatment in the clinic (five were mutant for either BRCA1 or BRCA2 (BRCA1/2), four with prior PARPi exposure), recapitulating the population of individuals with aggressive treatment-resistant HGSC in the clinic. Molecular analyses and in vivo treatment studies were undertaken.

Results:

Seven out of thirteen PRR PDX (54%) were sensitive to treatment with the AMA, eribulin (time to progressive disease (PD) ⩾100 days from the start of treatment) and 11 out of 13 PDX (85%) derived significant benefit from eribulin [time to harvest (TTH) for each PDX with p < 0.002]. In 5 out of 10 platinum-refractory HGSC PDX (50%) and one out of three platinum-resistant PDX (33%), eribulin was more efficacious than was cisplatin, with longer time to PD and significantly extended TTH (each PDX p < 0.02). Furthermore, four of these models were extremely sensitive to all three AMA tested, maintaining response until the end of the experiment (120d post-treatment start). Despite harbouring secondary BRCA2 mutations, two BRCA2-mutant PDX models derived from heavily pre-treated individuals were sensitive to AMA. PRR HGSC PDX models showing greater sensitivity to AMA had high proliferative indices and oncogene expression. Two PDX models, both with prior chemotherapy and/or PARPi exposure, were refractory to all AMA, one of which harboured the SLC25A40-ABCB1 fusion, known to upregulate drug efflux via MDR1.

Conclusion:

The efficacy observed for eribulin in PRR HGSC PDX was similar to that observed for paclitaxel, which transformed ovarian cancer clinical practice. Eribulin is therefore worthy of further consideration in clinical trials, particularly in ovarian carcinoma with early failure of carboplatin/paclitaxel chemotherapy.

Keywords: anti-microtubule agent, eribulin, high-grade serous ovarian cancer, homologous recombination deficiency, paclitaxel, platinum resistance, proliferative index

Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC) remains the deadliest form of gynaecological malignancy. The standard initial treatment for OC is surgery (either primary or interval debulking surgery following neoadjuvant chemotherapy) and platinum-based chemotherapy in combination with a taxane agent.1–3 Around 25–30% of OC will relapse early or fail to respond to first-line chemotherapy, becoming platinum-resistant or refractory (PRR) and these are associated with poor response rates to subsequent lines of therapies. 1 Despite initial good response rates to debulking surgery and systemic therapies for most patients, more than 70% of OC will recur and become increasingly drug resistant, accounting for ~70–80% of all gynaecological malignancy-related deaths.4,5

High-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSC) represents over 70% of all OC. The most frequently mutated gene in HGSC is TP53 (up to 96% of cases 6 ) and is thought to be the earliest genetic event in HGSC tumorigenesis. 7 Genomic instability is a common feature of HGSC, with focal amplifications of CCNE1, MYC and MECOM, each being observed in more than 20% of cases. 8 Mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 are observed in about 13% and 7% of cases, respectively, with about 65% of these being germline mutations.9–11 However, defects in the homologous recombination repair (HRR) pathway are reported in up to 50% of HGSC, including BRCA1/2 mutation, BRCA1/RAD51C promoter hypermethylation, and mutations in other HRR-related genes. 8 HRR deficiency (HRD) is associated with sensitivity to platinum compounds and PARP inhibitors (PARPi). 12 PARPi therapy has revolutionized treatment for individuals with HRD HGSC, with the potential for a cure for some individuals on the horizon.13,14

Platinum resistance or platinum-refractory progression is a strong clinical indicator for further treatment failure and poor prognosis. 15 Platinum-resistant HGSC, either de novo or acquired, is most commonly associated with the absence of HRD. Indeed, an HGSC can lose its HRD state, leading to acquired platinum resistance, due to a variety of molecular mechanisms, such as the development of secondary mutations within a primary HRD mutation, of, for example, BRCA1/2, RAD51C/D or BRIP1 (secondary or reversion mutations),16–21 or loss of BRCA1 or RAD51C promoter hypermethylation.19,22,23 Clinical platinum resistance, occurring following first-line chemotherapy, can also occur due to amplification/activation of oncogenes, which may be pre-existing (e.g. CCNE1, MYC 8 ), increased expression of ABCB1, which encodes the multidrug-resistant protein 1 (MDR1), 19 as well as alterations in the tumour microenvironment (TME). 24 Current treatment options for PRR tumours are anti-microtubule agents (AMA; paclitaxel and docetaxel), anthracyclines (doxorubicin liposomal), antimetabolites (gemcitabine) and alkylating agents (cyclophosphamide), alone or in combination with an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (bevacuzimab). Unfortunately, the response rates for these options are low, ranging between 15% and 20% as a single agent 25 and ~27% in combination with bevacizumab. 26

AMA act by targeting the hollow filamentous intracellular structures that play essential roles in cell growth and division, cell movement and intracellular transportation such as cytoplasmic streaming. 27 Microtubules are lengthened by a polymerization process whereby tubulins are added to the (+) ends of the microtubules and shortened by de-polymerization of the (+) end resulting in the disintegration of the microtubule in a controlled manner. 28 Paclitaxel binds to the inner part of the microtubules and disrupts the microtubule function by promoting microtubule polymerization and inhibiting depolymerization. 29 Vinorelbine is a microtubule polymerizer and binds to both the outer surface of the microtubules and the (+) end, inhibiting both polymerization and depolymerization of microtubules. 30 Vinorelbine is more effective than paclitaxel in the MYCN-driven epithelial OC subtype (also known as Stem A subtype) than in non-Stem A OC cell lines. 31 By contrast, eribulin binds exclusively to the (+) end of microtubules, resulting in inhibition of microtubule polymerization and promoting depolymerization, 32 which eventually leads to microtubule shortening. Eribulin has been shown to reverse epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition processes, improve the TME 33 and have a synergistic effect with immunotherapies, such as pembrolizumab, in breast cancer. 34 At present, neither vinorelbine nor eribulin is a standard treatment for HGSC due to its relatively poor responses in phase II clinical trials that were non-biomarker-driven studies.35–37

Patient-derived xenografts (PDX), involving implantation of human tumour tissue into immune-compromised mice, are well-established preclinical models that offer significant insights into exploring novel therapeutic approaches. 38 Their main putative advantage is the retention of molecular and phenotypic fidelity of the original tumour, which requires rigorous validation and molecular profiling to deem a PDX suitable for specific preclinical therapeutic exploration.

We characterized a cohort of PRR HGSC PDX models generated from treatment naïve or post-systemic therapy specimens, representative of individuals with PRR HGSC in the clinic. Given the importance of paclitaxel in the clinic and evidence for the potential role of AMAs in HGSC, 31 we explored targeting microtubules with vinorelbine and eribulin, which are not currently used in OC in the clinic and revealed efficacy for these agents in PRR HGSC PDX.

Methods

Patient samples, survival analyses and study approval

Surgical, biopsy or ascites HGSC samples were collected from patients without previous treatment (chemo-naïve) or with multiple lines of prior therapy (post-chemo) from the Royal Women’s Hospital (Table 1). Clinical follow-up of patient outcomes was obtained from the medical record and AOCS.

Table 1.

Characteristics of HGSC in the cohort generated from individuals who are chemo-naïve and who had received prior treatment with either chemotherapy and/or a PARPi.

| PDX ID | Age of patient | Stage at diagnosis | Germline BRCA status | Initial somatic BRCA status | Presumed platinum resistance mechanism | Other molecular findings | Number of treatments | Lines of treatment prior tissue collection | Lines of treatment after obtaining tissue for PDX | TTD from diagnosis (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

#183*

CN |

65 | IIIC | RAD51C homozygous promoter methylation # | BRCA2:c.6803G > A (likely benign) | TP53:c.661G > T, PARP1:c.2008C > A, EPHA7;c.2326G > A, FAT1;C.6440_6447del, BRD4:c.474G > C (VUS), PTEN del | Nil | (1) Carboplatin + paclitaxel + bevacuzimab,(2) Carboplatin + paclitaxel,(3) Carboplatin + gemcitabine | 37 | ||

|

#201

CN |

67 | IIIC | Wild type | TP53; c.422G > A, NOTCH3;c.6195-6196GC > A, PTEN del, MYC amp, CCNE1 amp, BCL2L1 amp, SRC amp, AURKA amp, GNAS amp, ARID1A:c.128_129imsGGC (VUS), BRD4 rearr, NOTCH3 rearr | Nil | (1) Carboplatin + paclitaxel,(2) Carboplatin(3) weekly paclitaxel | 42 | |||

|

#29

CN |

89 | IIIC | Wild type | BRCA2:c.1514T > C (likely benign) | TP53:c.840A > C, KRAS amp, CCNE1 amp, CCND2 amp, MCL1 amp, EPHB1 amp | Nil | No treatment | <1 | ||

|

#198

CN |

44 | IIIC | Wild type | TP53:c.80delC, PIK3CA:c.3140A > T, RB1:exon1-20 del, RHOA:c.118G > C, ARID1A:c.5116delC, XRCC2:c.110C > A, FOXA1 del | Nil | No treatment | 1 | |||

|

#87

CN |

73 | IIIC | Wild type | TP53:c.96_97insAG, GNAS amp | Nil | N/A | 18 (alive) | |||

|

#148

CN |

68 | IIIC | Wild type | TP53:c.273G > A, KRAS:c.35G > T, BLM:c.2208T > G, DCLRE1C:c.1558dupA, MYC amp, AKT2 amp | Nil | (1) Carboplatin + paclitaxel(2) Olaparib (PARPi) | 20 | |||

|

#13

CN |

51 | IIIC | Wild type | BRCA2:c.5517_5518delAG | TP53:c.657_665del, MAP2K1:c.167A > C | Nil | (1) Carboplatin + paclitaxel(2) Topotecan(3) Docetaxel | 16 | ||

|

#95

PT |

71 | IIIC | BRCA2:c.5946del | BRCA2:c.5888_5935delinsTCATAAGTCAGTCTCATCT, RECQL4 amp[1,2] | TP53:c.626_627del, RAD50:c.587G > C, NF1:c.7867C > A (VUS), MYC amp, PIK3CA amp | 5 | (1) Carboplatin + weekly paclitaxel(2) Carboplatin(3) Carboplatin + gemcitabine(4) Olaparib (PARPi; 20-month PARPi maintenance)(5) Carboplatin | (1) Liposomal doxorubicin | 72 | |

|

#111

PT |

NA | IIIC | Wild type | TP53:c.700T > A, GNAS:c.489C > G, CCNE1 amp, LRP1B del, EPHB1:c.1922C > T (VUS), KMT2A:c.6094G > T (VUS) | 5 | (1) Carboplatin + paclitaxel(2) Liposomal doxorubicin(3) Gemcitabine(4) AURK inhibitor(5) Weekly paclitaxel | (1) Olaparib + cyclophosphamide | 31 | ||

|

#931

PT |

53 | IV | Wild type | BRCA2:c.1313dupA | BRCA2:c.1300_1332del, BRCA2:c.1311_1313del | TP53:c.743G > A, RB1 del, PIK3CA amp, CCNE1 amp, SOX2 amp, BCL2L1 amp, TERC amp, GNAS:c.499A > G (VUS) | 7 | (1) Carboplatin + paclitaxel/gemcitabine(2) Carboplatin ± cediranib ± maintenance cediranib(3) Liposomal doxorubicin(4) Weekly paclitaxel(5) Docetaxel,(6) Cisplatin(7) Bevacizumab | Nil | 61 |

|

#32

PT |

60 | IIIC | Wild type | BRCA1:c.1251delT | RECQL4 amp[1,2] | TP53:c.97-1_97-6del, FANCA:c.3788_3790del (germline), MYC amp, PIK3CA:c.129A > G, GNAS amp | 5 | (1) Carboplatin + paclitaxel,(2) Carboplatin + gemcitabine(3) Olaparib (PARPi) + cyclophosphamide (19-month PARPi treatment)(4) Carboplatin + paclitaxel,(5) Liposomal doxorubicin | (1) Cisplatin | 92 |

|

#217

PT |

53 | IV | BRCA1:c.895_896del | BRCA1:c.670+281_1101del | TP53:c.963delA, PTEN:c.166delT, GNAS:c.2307C > A | 6 | (1) Platinum-based chemotherapy(2) Pamiparib (PARPi; 14-month PARPi treatment)(3) Carboplatin + paclitaxel(4) Novel agent trial therapy(5) Liposomal doxorubicin | (1) Carboplatin + gemcitabine; olaparib (PARPi; maintenance for one cycle only) | 96 | |

|

#169

PT |

34 | IIIC | Wild type | BRCA1 homozygous promoter methylation | BRCA1 heterozygous promoter methylation | TP53:c.380C > T, PPM1D:c.1384C > T, RB1 del | 2 | (1) Carboplatin + paclitaxel,(2) Carboplatin | (1) Liposomal doxorubicin + bevacuzimab(2) Docetaxel | 18 |

|

#86

PT |

54 | IIIC | BRCA2:c.5946delT | BRCA2:c.6331_6841+200delinsTCAG, RECQL4 amp[1,2], SLC25A40-ABCB1 fusion[3] | TP53; c.827C > G, CDKN2A del | 6 | (1) Carboplatin + paclitaxel + bevacuzimab(2) Carboplatin/cisplatin + gemcitabine(3) Olaparib (PARPi; 6-month PARPi maintenance)(4) Liposomal doxorubicin then olaparib (PARPi) 2 cycles discontinued(5) Cisplatin + gemcitabine,(6) Cyclophosphamide | Nil | 47 |

PDX #183 was a chemo-naïve platinum-sensitive HGSC PDX model included as a comparator for PDX platinum response. # Homozygous promoter methylation of RAD51C is known to confer HRD and sensitivity to PARPi.

AURK, aurora kinase inhibitor trial; CN, chemo-naive; HGS FT, high-grade serous fallopian tube; HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; HRD, homologous recombination DNA repair; PARPi, PARP inhibitor therapy in bold; PDX, patient-derived xenograft; PT, post-treatment; TTD, time to death of patient.

Overall survival of each patient in the study was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or the last known clinical assessment. Survival data for patients with HGSC were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) for comparison (n = 488). Overall survival was calculated by log-rank test (Mantel–Cox) using Prism v8.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

PDX generation and treatment

All experiments involving animals were performed according to the National Health and Medical Research Council Australian Code for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes 8th Edition, 2013 (updated 2021) and were approved by the WEHI Animal Ethics Committee (2016.023). PDX #169 and #86 were generated by mixing tumour cells isolated from ascites with Matrigel Matrix (Corning) and transplanting subcutaneously into NOD-scid IL2Rγnull recipient mice as previously described. 22 All other PDX were generated by transplanting fragments of tumour tissue subcutaneously into NOD-scid IL2Rγnull recipient mice (T0 = founder mouse). The founder tumours were harvested and transplanted into additional recipient mice to generate the T1 cohorts (T1 = passage 1), and immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed and reviewed by a gynaecological pathologist. We have previously published data on five of these HGSC PDX models (#13, #29, #169, #183 and #201) and our methods and validation of PDX through the process of passaging are described in more detail.22,23,42

Recipient mice bearing T2-T7 tumours (180–300 mm3 in size) were randomly assigned to cisplatin (Pfizer), paclitaxel (Bristol-Myers Squibb), vinorelbine (Pfizer), eribulin (Eisai Inc.) or vehicle treatment groups. The vehicle for all treatments was Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS). The in vivo treatment regimens were as follows: cisplatin, 4 mg/kg, administered by intraperitoneal (IP) injection on days 1, 8 and 18; paclitaxel, 25 mg/kg, administered by IP injection twice a week for 3 weeks; vinorelbine, 15 mg/kg, delivered by intravenous injection on days 1, 8 and 18; and eribulin, 1 mg/kg, by IP injection three times a week for 3 weeks. Electronic calliper measurements of tumour size were taken twice a week until tumours reached the ethical endpoint (>700 mm3) or mice reached the experimental endpoint, 120 days post-treatment. Data collection was conducted using the Studylog LIMS software (Studylog Systems, San Francisco, CA, USA). Graphing and statistical analysis were conducted using the SurvivalVolume package. 43 Time to progression (TTP or PD), time to harvest (TTH) and treatment responses are as defined previously. 42

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumour samples were sectioned and were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E), as well as being sent for automatic immunostaining using the Ventana BenchMark Ultra fully automated staining instrument (Roche Diagnostics, USA). The following antibodies were used: anti-Ki-67 (MIB-1, Dako), anti-PAX8 (polyclonal, Proteintech) and anti-p53 (DO-7, Dako). H&E and IHC slides were scanned digitally at 20× magnification using the Panoramic 1000 scanner (3DHISTECH Ltd.). High-definition images were uploaded into CaseCenter (3DHISTECH Ltd.) and images were processed using FIJI image analysis software. 44 Ki-67 staining was quantified using CellProfiler™ (Broad Institute) in 4–6 fields of view for three independent tumours of each PDX model (i.e. 11–18 total fields of view per PDX model).

DNA sequencing

Targeted sequencing using the Foundation Medicine T5a panel, which sequences 287 cancer-related genes, was carried out on seven PRR PDX tumours (#201, #29, #148, #13, #111, #931 and #169) and #183. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was carried out on five PDX tumours (#87, #95, #32, #217 and #86), and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was carried out on one patient tumour (#198). Mutations in HRR DNA repair genes were assessed by sequencing patient and PDX samples using the NGS-based BROCA-HR assay. 45 The BROCA_HRv4 assay was used to analyse PDX #13 and #29, with results published previously. 42 The BROCA-HRv6 assay was used to analyse PDX #169 and #201 published previously. 22 The BROCA-HRv7 assay was used to analyse all other PDX, with results for PDX #183 published previously. 23 PDX samples were also sequenced using Foundation Medicine’s NGS-based T5a assay, 46 with results for PDX #13, #29, #169 and #201 published previously. 22

WES was performed on DNA extracted from five snap-frozen PDX tumours (#87, #95, #32, #217 and #86) or whole blood using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). DNA was quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS or BR kits (ThermoFisher Scientific). Libraries were generated using the SureSelect Low Input Clinical Research Exome v2 library prep. Sequencing using 2 × 150 bp NovaSeq 6000 was performed.

WGS was carried out on DNA extracted from one snap-frozen patient tumour (#1198) and whole blood using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen). DNA was quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS or BR kits (ThermoFisher Scientific). Libraries were prepared using the Illumina TruSeq Nano library method using 200 ng of DNA. Extracted DNA was sheared using the Covaris M220 Focussed-ultrasonicator with a target fragment length of 550 bp through bead size selection. The Illumina TruSeq nano DNA library preparation kit was used for end repair and adenylation of 3′ fragment end. The libraries were assessed for quality (Qubit, TapeStation4200 and KAPA Illumina library quantification kit using qPCR QuantStudio6) prior to normalization and pooling before loading onto the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 for sequencing using paired 150 bp reads.

For WES and WGS, the average sequencing depth was 36X for germline and 75X for tumour (Supplemental Table S4).

Genome sequencing analysis

A bionix 47 pipeline was used to process samples from sequencing data to variant calls. Sequences were aligned to Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 38 (GRCh38) using minimap2 v2.17, 48 and also to the Mus Musculus reference GRCm38 for PDX. Mouse-derived sequences were removed with XenoMapper v1.0.2. 49 WES used the Agilent SureSelect Clinical Research Exome V2, with reads filtered to 100 bp on each side of capture regions. Small mutations were called using Octopus v0.7.0 50 and annotated using SnpEff v4.3. 51 Copy number variants were called using FACETS v0.6.1. 52 Structural variants were called using GRIDSS (v2.13.2)53,54 and annotated using StructuralVariantAnnotation (Version 1.12.0). 55 Single nucleotide variants were checked against the ClinVar public archive of reports of the relationships among human variations and phenotypes (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/), and in-silico predictor of pathogenicity MutationTaster, 56 using dbNSFP v4.2a. 57

DNA methylation analysis

Promoter methylation of BRCA1 and RAD51C was determined as previously described.17,23

Immunoblotting

Tumours were homogenized in ice-cold RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris; pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS in H2O, supplemented with a complete mini protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche) using Precellys Ceramic Kit tubes in the Precellys 24 homogenizing instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Proteins from lysates were separated on NuPAGE® Novex® Bis-Tris 10% gels (Thermo Fish Scientific). Gels were transferred onto PVDF membranes using the iBlot™ Transfer system (Thermo Fish Scientific). Membranes were probed with antibodies specific for Cyclin E1 (HE12, Millipore), MYC (9E10, Santa Cruz Biotech), MDR1 (E1Y7S, Cell Signalling), or β-Actin (AC-15, Sigma).

ABCB1 Q-RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from snap-frozen PDX tumours using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using random primers (Promega) and M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega). Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (Q-RT-PCR) was used to measure ABCB1 transcript abundance. Q-RT-PCR was performed in triplicate to examine ABCB1 expression, with internal housekeeping genes GAPDH and HPRT used for normalization as previously described. 41 Testing for the presence of the SLC25A40-ABCB1 fusion transcript was also performed as previously described. 41

Statistical analysis

Survival analysis was performed using the log-rank test on Kaplan–Meier survival function estimates. Statistical significance representations: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Results

Generation of a cohort of HGSC PDX models from chemo-naïve patients with poor survival outcomes and patients who had received multiple lines of treatment

We developed 13 PDX models of PRR HGSC: six PDX models were generated from HGSC tissue from individuals who had not received prior chemotherapy (chemo-naïve HGSC samples) and seven PDX models were from HGSC collected from individuals who had received prior treatment with either chemotherapy and/or a PARPi (post-chemotherapy HGSC samples). An additional chemo-naïve model (PDX #183), which was platinum sensitive, was included for comparison (Table 1). Of these 14 PDX models, 12 were generated from tumour tissue with minimal manipulation and two PDX (#169 and #86) were generated from ascites. Post-chemotherapy samples used for generating PDX had been exposed to a median of five (range: 2–7) lines of treatment (including up to one line of targeted therapy; Table 1). Four out of seven patients had also received PARPi as part of their treatment regimens: two as maintenance therapy, and two upon progression. The latter two patients received subsequent lines of treatment prior to collection of the tumour sample used for PDX generation (detailed in Table 1).

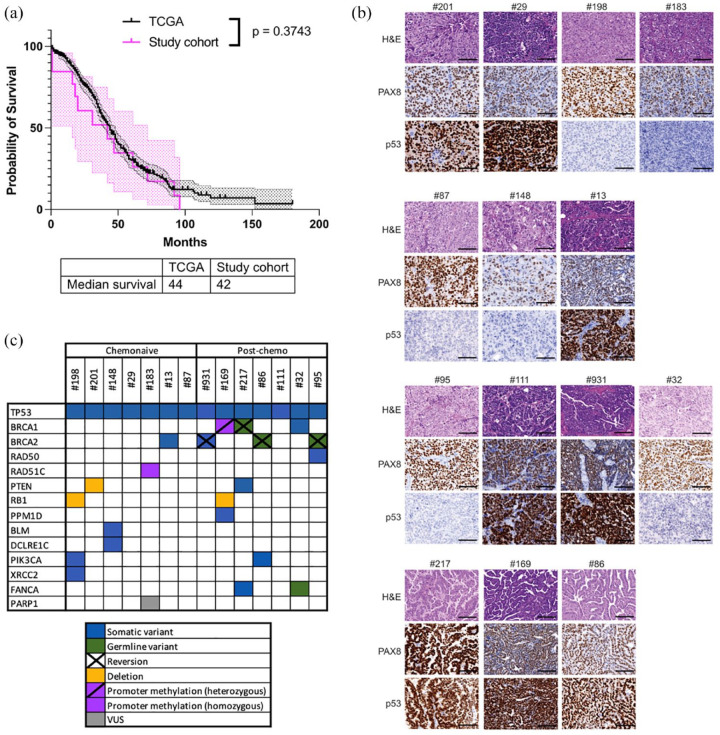

The overall median survival time for the entire cohort of individuals from whom the PDX were generated, measured from initial diagnosis to death, was similar to the overall OC cohort in TCGA [42.0 months versus 44.0 months, p = 0.3743; Figure 1(a)]. Of these 14 individuals, seven HGSC were assessed as being HRD, consistent with the expected proportion of ~50% HGSC being HRD. Individuals from the chemo-naïve cohort had an overall median survival time which was significantly poorer compared to the outcome of all individuals diagnosed with OC in TCGA (overall OC cohort), due to the predominance of cases in this chemo-naïve cohort being PRR (six of seven cases), based on our selection criteria for this study (18.0 months versus 44.0 months, p = 0.0004; Supplemental Figure S1). In keeping with the emergence of acquired treatment resistance, the median overall survival of individuals in the post-chemotherapy cohort was poor from the time of tumour collection (8 months).

Figure 1.

Characterization of a cohort of HGSC PDX representative of the patient population. (a) Overall survival of HGSC patients in TCGA (n = 488) compared to the patients from which the PDX cohort was derived (n = 13). Median overall survival, from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last known follow-up, for the TCGA cohort was 44 months and for our 13 cases was 42.0 months. Cases in the chemo-naïve cohort were predominantly platinum-resistant or refractory and two individuals were too unwell to receive chemotherapy, consistent with the reduced median OS. (b) Representative images of tumour sections stained with H&E, PAX8 and p53 for each PDX model. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (c) Summary of HR genes altered in the PDX models.

HGSC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; PDX, patient-derived xenograft; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

PDX models were all confirmed to be HGSC following review by a gynaecological histopathologist. All PDX models and all baseline and archival samples were confirmed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) to express PAX8, consistent with the majority of HGSC [Figure 1(b)]. All PDX exhibited abnormal expression of p53 (negative or strong staining), in keeping with their original HGSC p53 status based on their clinical histopathology reports [Figure 1(b)].

Homologous recombination DNA repair pathway analysis of HGSC and PDX

An important determinant of platinum response is the HRR gene mutation status and hence targeted sequencing of genes involved in DNA repair was carried out on all PDX and six patient samples (Table 1). All 14 cases harboured pathogenic mutations in TP53 [Figure 1(c), Table 1 and Supplemental Table S1], consistent with p53 expression by IHC (null or strong). All chemo-naïve PDX were wild type for BRCA1/2, except for PDX #13 which contained a frameshift mutation in BRCA2 [G1840fs*5; Figure 1(c), Table 1 and Supplemental Table S2]. In the cohort of PDX derived from individuals who had received prior chemotherapy and/or PARPi, five out of seven HGSC were confirmed to have pathogenic BRCA1/2 mutations (Supplementary Table S2). In line with the drug-resistant phenotype of these cases, secondary reversion mutations were observed, one in BRCA1 and three in BRCA2 [Figure 1(c), Table 1 and Supplemental Table S2].

Two PDX models, #183 and #169, were previously reported to harbour RAD51C and BRCA1 promoter methylation, respectively.22,23 PDX #183 (platinum-sensitive case) was derived from a chemo-naïve patient, harboured homozygous methylation of the RAD51C promoter [Figure 1(c) and Table 1] and was sensitive to platinum chemotherapy and PARPi. 23 By contrast, PDX #169 was derived from a young woman with platinum-refractory HGSC (Table 1), with confirmed heterozygous methylation of the BRCA1 promoter, in comparison with archival patient surgical samples which had previously been shown to contain homozygous BRCA1 promoter methylation. 22

Although not identified in the baseline patient tumour, mutations in XRCC2, RAD50 and PARP1 were also identified in one PDX each (Table 1). These mutations could have been present in subclones not sampled in the patient tumours. Although not in HRR genes, mutations that may modulate sensitivity to PARPi were also identified in PIK3CA (two PDX), PTEN (two PDX) and RB1 [three PDX; Figure 1(c) and Table 1]. Three PDX models, which lacked HRR gene mutations as detected by targeted sequencing and lacked promoter methylation of either BRCA1 or RAD51C, were refractory to PARPi therapy [Kondrashova et al. 22 and Figure 1(c), Table 2 and Supplemental Figure S2].

Table 2.

Responses of HGSC PDX to treatment with cisplatin or paclitaxel, vinorelbine or eribulin.

| PDX model | Type | Treatment | Number of mice (n) | Time to PD (days) | Median TTH (days) |

p Value cf. Vehicle |

p Value cf. Cisplatin |

p Value cf. Paclitaxel |

p Value cf. Vinorelbine |

p Value cf. Eribulin |

Drug response score 27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #183* | Chemo-naïve | Vehicle | 24 | 14 | 50 | <0.0001 | 0.0007 | 0.0003 | 0.0001 | ||

| Cisplatin | 9 | 115 | >120 | <0.0001 | 0.0833 | 0.0812 | 0.4386 | Sensitive | |||

| Paclitaxel | 6 | >120 | >120 | 0.0007 | 0.0833 | 0.1053 | 0.4386 | Sensitive | |||

| Vinorelbine | 6 | 91 | >120 | 0.0003 | 0.0812 | 0.1053 | 0.3454 | Resistant | |||

| Eribulin | 5 | 101 | >120 | 0.0001 | 0.4386 | 0.4386 | 0.3454 | Sensitive | |||

| #148 | Chemo-naïve | Vehicle | 17 | 10 | 50 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | |||

| Cisplatin | 11 | 87 | 116 | <0.0001 | 0.0922 | 0.4953 | Resistant | ||||

| Paclitaxel | 0 | ||||||||||

| Vinorelbine | 7 | 77 | 102 | 0.0001 | 0.0922 | 0.0245 | Resistant | ||||

| Eribulin | 5 | 91 | 120 | 0.0003 | 0.4953 | 0.0245 | Resistant | ||||

| #13 | Chemo-naïve | Vehicle | 18 | 10 | 43 | 0.0002 | 0.0030 | 0.0010 | 0.0005 | ||

| Cisplatin | 6 | 80 | >120 | 0.0002 | 0.0664 | 0.7095 | 0.2467 | Resistant | |||

| Paclitaxel | 5 | 70 | 88 | 0.0030 | 0.0664 | 0.2597 | 0.9374 | Resistant | |||

| Vinorelbine | 6 | 80 | 109 | 0.0010 | 0.7095 | 0.2597 | 0.9526 | Resistant | |||

| Eribulin | 6 | 70 | 116 | 0.0005 | 0.2467 | 0.9374 | 0.9526 | Resistant | |||

| #87 | Chemo-naïve | Vehicle | 15 | 7 | 29 | 0.0010 | 0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | ||

| Cisplatin | 7 | 14 | 85 | 0.0010 | 0.1037 | 0.0107 | 0.1044 | Refractory | |||

| Paclitaxel | 7 | 115 | >120 | 0.0001 | 0.1037 | 0.2775 | 0.7849 | Sensitive | |||

| Vinorelbine | 7 | 94 | >120 | <0.0001 | 0.0107 | 0.2775 | 0.1879 | Resistant | |||

| Eribulin | 8 | 119 | >120 | 0.0002 | 0.1044 | 0.7849 | 0.1879 | Sensitive | |||

| #32 | Post-chemo | Vehicle | 13 | 7 | 43 | 0.0004 | 0.0004 | 0.0004 | 0.0001 | ||

| Cisplatin | 5 | 14 | 99 | 0.0004 | 0.7289 | 0.3835 | 0.3314 | Refractory | |||

| Paclitaxel | 5 | 77 | 95 | 0.0004 | 0.7289 | 0.9667 | 0.6727 | Resistant | |||

| Vinorelbine | 5 | 73 | 102 | 0.0004 | 0.3835 | 0.9667 | 0.7220 | Resistant | |||

| Eribulin | 6 | 66 | 109 | 0.0001 | 0.3314 | 0.6727 | 0.7220 | Resistant | |||

| #201 | Chemo-naïve | Vehicle | 30 | 10 | 32 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | ||

| Cisplatin | 15 | 45 | 85 | <0.0001 | 0.0008 | 0.0012 | 0.0011 | Refractory | |||

| Paclitaxel | 7 | >120 | >120 | <0.0001 | 0.0008 | 0.0712 | 1.0 | Sensitive | |||

| Vinorelbine | 9 | 108 | >120 | <0.0001 | 0.0012 | 0.0712 | 0.0922 | Sensitive | |||

| Eribulin | 5 | >120 | >120 | 0.0002 | 0.0011 | 1.0 | 0.0922 | Sensitive | |||

| #29 | Chemo-naïve | Vehicle | 8 | 7 | 43 | 0.2684 | 0.0021 | 0.0085 | 0.0008 | ||

| Cisplatin | 5 | 7 | 60 | 0.2684 | 0.0035 | 0.0330 | 0.0018 | Refractory | |||

| Paclitaxel | 5 | >120 | >120 | 0.0021 | 0.0035 | 0.3711 | 1.0 | Sensitive | |||

| Vinorelbine | 5 | >120 | >120 | 0.0085 | 0.0330 | 0.3711 | 0.3173 | Sensitive | |||

| Eribulin | 5 | >120 | >120 | 0.0008 | 0.0018 | 1.0 | 0.3173 | Sensitive | |||

| #198 | Chemo-naïve | Vehicle | 17 | 7 | 22 | 0.0083 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| Cisplatin | 8 | 7 | 29 | 0.0083 | 0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | Refractory | |||

| Paclitaxel | 8 | >120 | >120 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.5073 | 0.1643 | Sensitive | |||

| Vinorelbine | 8 | >120 | >120 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.5073 | 0.5060 | Sensitive | |||

| Eribulin | 8 | >120 | >120 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.1643 | 0.5060 | Sensitive | |||

| #95 | Post-chemo | Vehicle | 16 | 7 | 43 | 0.0035 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 | ||

| Cisplatin | 9 | 10 | 78 | 0.0035 | 0.0004 | 0.0004 | 0.0036 | Refractory | |||

| Paclitaxel | 7 | >120 | >120 | 0.0001 | 0.0004 | 0.3315 | 0.9701 | Sensitive | |||

| Vinorelbine | 7 | >120 | >120 | 0.0001 | 0.0004 | 0.3315 | 0.4229 | Sensitive | |||

| Eribulin | 6 | >120 | >120 | 0.0002 | 0.0036 | 0.9701 | 0.4229 | Sensitive | |||

| #111 | Post-chemo | Vehicle | 19 | 7 | 46 | 0.0042 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||

| Cisplatin | 7 | 7 | 74 | 0.0042 | 0.0216 | 0.0003 | 0.0047 | Refractory | |||

| Paclitaxel | 8 | 77 | 120 | <0.0001 | 0.0216 | 0.0249 | 0.2004 | Resistant | |||

| Vinorelbine | 7 | 115 | >120 | <0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.0249 | 0.2327 | Sensitive | |||

| Eribulin | 5 | 105 | >120 | 0.0001 | 0.0047 | 0.2004 | 0.2327 | Sensitive | |||

| #931 | Post-chemo | Vehicle | 26 | 10 | 36 | 0.0931 | <0.0001 | 0.0004 | 0.0011 | ||

| Cisplatin | 10 | 7 | 81 | 0.0931 | 0.0041 | 0.0297 | 0.0149 | Refractory | |||

| Paclitaxel | 9 | >120 | >120 | <0.0001 | 0.0041 | 0.6955 | 0.4524 | Sensitive | |||

| Vinorelbine | 7 | >120 | >120 | 0.0004 | 0.0297 | 0.6955 | 0.3666 | Sensitive | |||

| Eribulin | 7 | 91 | 109 | 0.0011 | 0.0149 | 0.4524 | 0.3666 | Resistant | |||

| #217 | Post-chemo | Vehicle | 14 | 7 | 25 | 0.0164 | <0.0001 | 0.0071 | 0.0001 | ||

| Cisplatin | 7 | 7 | 53 | 0.0164 | 0.0005 | 0.4839 | 0.0555 | Refractory | |||

| Paclitaxel | 7 | 73 | 95 | <0.0001 | 0.0005 | 0.0007 | 0.0040 | Resistant | |||

| Vinorelbine | 7 | 14 | 50 | 0.0071 | 0.4839 | 0.0007 | 0.0001 | Refractory | |||

| Eribulin | 7 | 50 | 74 | 0.0001 | 0.0555 | 0.0040 | 0.0001 | Resistant | |||

| #169 | Post-chemo | Vehicle | 30 | 10 | 46 | 0.1275 | 0.0389 | 0.5507 | 0.0250 | ||

| Cisplatin | 9 | 10 | 67 | 0.1275 | 0.3241 | 0.3795 | 0.3102 | Refractory | |||

| Paclitaxel | 6 | 17 | 78 | 0.0389 | 0.3241 | 0.1294 | 0.9895 | Refractory | |||

| Vinorelbine | 6 | 7 | 67 | 0.5507 | 0.3795 | 0.1294 | 0.0960 | Refractory | |||

| Eribulin | 6 | 10 | 75 | 0.0250 | 0.3102 | 0.9895 | 0.0960 | Refractory | |||

| #86 | Post-chemo | Vehicle | 15 | 7 | 46 | 0.0411 | 0.6982 | 0.9431 | 0.3008 | ||

| Cisplatin | 7 | 7 | 78 | 0.0411 | 0.0187 | 0.0452 | 0.0043 | Refractory | |||

| Paclitaxel | 6 | 10 | 60 | 0.6982 | 0.0187 | 0.7262 | 0.0186 | Refractory | |||

| Vinorelbine | 7 | 10 | 50 | 0.9431 | 0.0452 | 0.7262 | 0.1302 | Refractory | |||

| Eribulin | 6 | 7 | 39 | 0.3008 | 0.0043 | 0.0186 | 0.1302 | Refractory |

PDX ordered according to response to platinum (one platinum-sensitive comparator PDX, two platinum-resistant PDX, then 11 refractory PDX). In 5 out of 10 platinum-refractory PDX (50%), eribulin treatment was more efficacious than treatment with cisplatin (TTH p < 0.015, log-rank test). Six out of ten (60%) platinum-refractory PDX were either sensitive or resistant to Eribulin. In 9 out of 13 (69%) PRR PDX, the TTH for eribulin was >100 days (29–99 days for cisplatin), with two of the three remaining PDX not requiring harvest post-treatment for >70 days (53 and 67 days for cisplatin). Only one PDX was TTH for eribulin similar to that of vehicle (#86, ABCB1 fusion present). These results were similar to those observed for paclitaxel, a drug which transformed OC clinical practice. *PDX #183 was a chemo-naïve platinum-sensitive HGSC PDX model included as a comparator for PDX platinum response.

HGSC, High-grade serous cancer; PDX, Patient-derived xenograft; TTH, time to harvest of PDX; PD, progressive disease, defined as an increase in tumour volume of >20% from 0.2 cm3, or from nadir post-treatment (if nadir ⩾ 0.2 cm3) occurring ⩾100 days from the start of treatment; CR, complete remission, defined as tumour volume <0.2 cm3; PR, partial remission, defined as a reduction in tumour volume of >30% from baseline. PDX were considered sensitive to a drug if the average PDX tumour volume of the recipient mice underwent initial regression (with either CR or PR, followed by PD occurring ⩾100 days from the start of treatment. PDX were considered resistant to a drug if initial tumour regression (CR or PR) or stable disease (SD) was followed by PD within 100 days from the start of treatment. PDX were considered refractory to a drug if three or more mice bearing that PDX failed to respond (no tumour regression resulting in either CR, PR or SD) during treatment (days 1–18). Platinum status in bold. Eribulin median TTH in bold, including p values (log-rank test) for eribulin versus cisplatin, and where this was not significant, p value for eribulin versus placebo. One PDX (#148) was not treated with paclitaxel, however, vinorelbine and eribulin responses were tested in all 14 models.

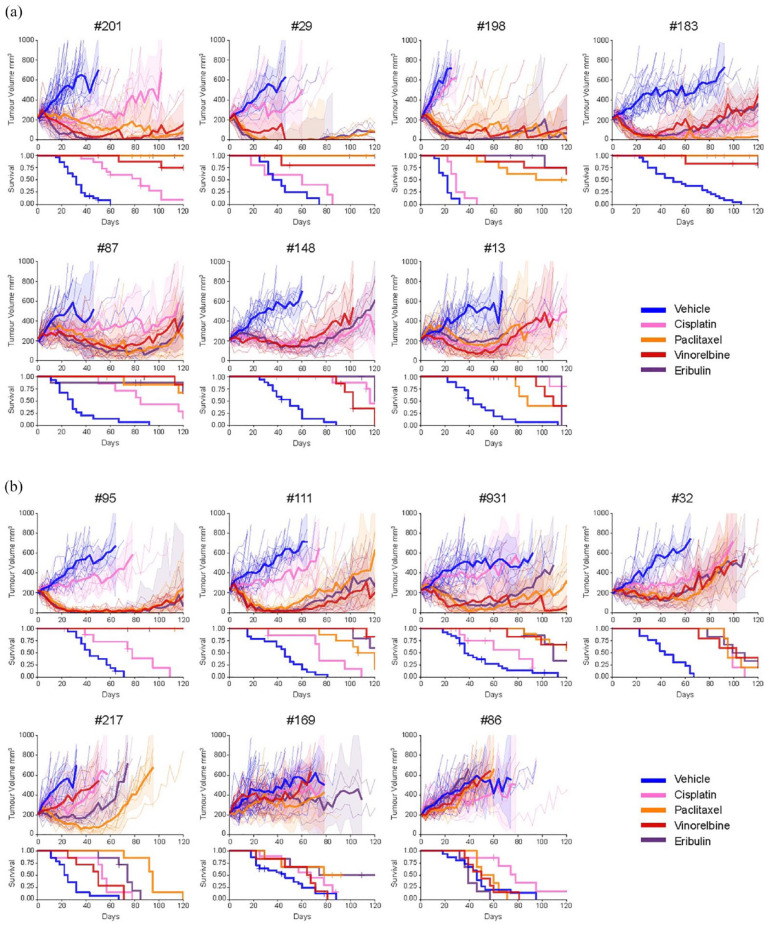

All PDX models were resistant or refractory to platinum-based chemotherapy

Platinum chemotherapy is one of the standard-of-care treatments for HGSC. Therefore, this PRR PDX cohort was expanded and mice were randomized to the maximum tolerated dose of cisplatin (4 mg/kg on days 1, 8 and 18) or vehicle control (DPBS) arms. Responses were described as platinum sensitive, resistant or refractory as previously published, in keeping with clinically relevant responses (see Supplemental Table S3). 42 Chemo-naïve HGSC PDX exhibited better responses to cisplatin than did post-chemotherapy HGSC PDX [Figures 2(a), (b) and 3(a) and Table 2]. A chemo-naïve platinum-sensitive PDX (PDX #183) was included to demonstrate platinum-response. Two PDX (#148 and #13, both chemo-naïve) were resistant to cisplatin. The remaining 11 PDX were refractory to cisplatin [Figures 2(a) and 3(a)].

Figure 2.

HGSC PDX models mostly displayed improved responses to anti-microtubule agents compared to cisplatin. (a) In vivo treatment of mice bearing chemo-naïve HGSC PDX tumours with DPBS (vehicle control), cisplatin (4 mg/kg), paclitaxel (25 mg/kg), vinorelbine (15 mg/kg) and eribulin (1 mg/kg). (b) In vivo treatment of mice bearing post-chemotherapy/PARPi HGSC PDX tumours with DPBS (vehicle control), cisplatin (4 mg/kg), paclitaxel (25 mg/kg), vinorelbine (15 mg/kg) and eribulin (1 mg/kg). A number of mice and p values for each model and treatment are shown in Table 2. Tumour volumes for individual mice are indicated by dotted lines with the solid line representing the mean. Shaded area = 95% confidence interval. Time to PD and harvest (TTH) are shown in Table 2.

DPBS, Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline; HGSC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; PD, progressive disease; PDX, patient-derived xenograft; PARPi, TTH, time to harvest.

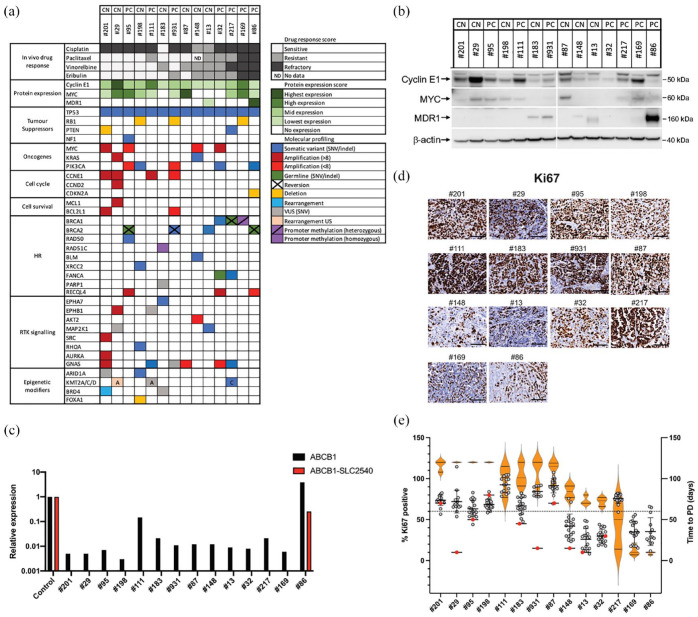

Figure 3.

HGSC PDX models with markers of increased proliferation exhibit increased sensitivity to anti-microtubule agents. (a) Summary of drug response, protein expression and gene alterations in PDX models. (b) Expression of Cyclin E1, MYC and MDR1 in tumours from each HGSC PDX model as determined by Western Blot analysis. Samples are ordered left to right based on sensitivity to eribulin, with the most sensitive models on the left (a representative blot is shown; a lane was removed as indicated by the vertical line). β-actin was used as a loading control. (c) Expression of ABCB1 and the SLC25A40-ABCB1 fusion transcript as determined by qPCR analysis. A patient-derived cell line AOCS18.5, previously shown to be positive for the SLC25A40-ABCB1 fusion, 41 was used as a positive control. (d) Representative images of tumour sections stained with Ki-67 for each PDX model. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (e) Quantification of Ki-67 staining in PDX tumours (grey dots, with mean and SD; across the PDX cohort, the Ki-67 range was 26–92% with an overall mean of 61%; using a cutoff of >60% for high (dashed line), eight PRR PDX models (not including the platinum-sensitive model, #183) had high Ki-67), baseline tumours (red dots) and associations with time to PD for treatment with three AMAs (paclitaxel, vinorelbine and eribulin) in vivo (orange violin plots).

HGSC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; PDX, patient-derived xenograft; PRR, platinum-resistant or refractory.

Within the cisplatin-refractory category, four PDX (#201, #87, #32 and #169), two of which were chemo-naïve, exhibited no tumour regression; however, disease stabilization prior to PD resulted in statistically significant improvements in median TTH compared to vehicle-treated mice. Seven other PDX, two of which were also chemo-naïve, exhibited no regression and had no statistically significant improvements in median TTH compared with vehicle-treated mice [Figures 2 and 3(a) and Table 2].

AMAs were efficacious in platinum-refractory HGSC PDX

To test responses to AMA, mice harbouring PDX were treated with clinically relevant dosing regimens of paclitaxel (at 25 mg/kg twice a week for 3 weeks), vinorelbine (15 mg/kg days 1, 8 and 18) or eribulin (1 mg/kg three times a week for 3 weeks). In vivo drug responses were scored with similar criteria as for cisplatin.

Paclitaxel sensitivity, defined as tumour regression with no PD within 100 days following the last dose of paclitaxel, was demonstrated for six PDX, all of which were platinum refractory (PDX #201, #29, #198, #95, #931 and #87). Four PDX were resistant to paclitaxel, demonstrating short-lived tumour regression, with progression between 50 and 100 days. Two PDX, both platinum refractory, were also refractory to paclitaxel [PDX #169 and #86, neither was chemo-naïve; Figures 2 and 3(a) and Table 2]. Overall, six out of 12 PRR PDX demonstrated improvement in median TTH for paclitaxel compared to cisplatin: #201, #29, #198, #95, #111, all >120 days versus 29–85 days (p < 0.005) and PDX #217: 95 days versus 53 days (p = 0.0005; Table 2).

Vinorelbine sensitivity was also demonstrated for six PDX, all of which were platinum refractory (PDX #201, #29, #198, #95, #931, all sensitive to paclitaxel and PDX #111). Five PDX were vinorelbine-resistant. Three PDX, all of which were platinum refractory, were refractory to vinorelbine [PDX #217, #169 and #86, none were chemo-naïve; Figures 2 and 3(a) and Table 2]. Overall, seven out of 13 PRR PDX demonstrated improvement in median TTH for vinorelbine compared to cisplatin: #201, #29, #198, #95, #87, #111 and #931, all >120 days versus 29–85 days (p = 0.0001–0.04; Table 2).

Eribulin sensitivity was also demonstrated for six PDX, all of which were platinum refractory as well as being sensitive to either paclitaxel, vinorelbine or both (PDX #201, #29, #198, #95, #87 and #111). Five PRR PDX were eribulin resistant. The two PDX which were refractory to platinum, paclitaxel and vinorelbine, were also refractory to eribulin [PDX #169 and #86; Figures 2 and 3(a) and Table 2]. Overall, 6 out of 13 PRR PDX demonstrated improvement in median TTH for eribulin compared to cisplatin: #201, #29, #198, #95, #111, all > 120 days versus 29–85 days (p = 0.0001–0.005) and PDX #931: 109 days versus 81 days p < 0.015 (Table 2).

In summary, the four most drug-resistant HGSC PDX models (#169, #86, #32 and #217) were derived from individuals who had received prior chemotherapy and, in three cases, PARPi (Tables 1 and 2). PDX #169 and #86 were refractory to all four drugs tested (cisplatin, paclitaxel, vinorelbine and eribulin). By contrast, four platinum refractory PDX (#201, #29, #198 and #95) were sensitive for more than 100 days to all AMA tested (paclitaxel, vinorelbine and eribulin), including one PDX (#95) that was derived from an individual who had received prior chemotherapy and PARPi (Tables 1 and 2). In five out of 11 platinum refractory HGSC PDX (50%), eribulin was more efficacious than cisplatin, with a longer time to progression (p < 0.03 per PDX) and with TTH for tumours following eribulin treatment being greater than 120 days (end of the experiment). The platinum-sensitive PDX, #183, was also sensitive to paclitaxel and eribulin (PD ⩾ 100 days post-treatment start), with TTH > 120 days for all three AMA, compared with vehicle (p < 0.001), as was a second platinum-sensitive PDX (data not shown).

Sensitivity to AMA based on BRCA1/2 status and prior therapies

The most sensitive PDX to AMA was PDX #95 [time to PD > 120d for paclitaxel (P), vinorelbine (V) and eribulin (E)] (Table 2), somewhat surprisingly, as the individual had undergone five lines of therapy, including PARPi, prior to biopsy resulting in PDX generation (Table 1). The individual was known to carry a germline BRCA2 pathogenic variant, which was also identified in the corresponding PDX samples. A secondary somatic deletion and insertion in BRCA2 was also identified in the tumour specimen used for PDX generation, located just upstream of the original deletion, which restored the reading frame of BRCA2 and is predicted to restore BRCA2 function [Figures 1(c) and 3(a) and Supplemental Table S2].

PDX #931 also displayed AMA sensitivity (time to PD > 120d, >120d and 91d for P, V and E, respectively) despite being generated from a patient who had received seven prior lines of therapy (Tables 1 and 2). This PDX also harboured a somatic BRCA2 pathogenic mutation, as well as a secondary somatic BRCA2 mutation that restored the open reading frame, presumably as a resistance mechanism to platinum chemotherapy [Figures 1(c) and 3(a) and Supplemental Table S2].

PDX #32 and #217 were both derived from HGSC with BRCA1 pathogenic mutations and both displayed initial response followed by resistance to AMA (time to PD 77d, 73d, 66d and 73d, 14d, 50d, for P, V, E, respectively), deriving some benefit, despite five to six prior lines of therapy including PARPi (Tables 1 and 2). PDX #217 also harboured a secondary somatic mutation in BRCA1 predicted to either create a premature stop at codon 234, or alternative splicing of BRCA1 [Figures 1(c) and 3(a) and Supplemental Table S2].

By contrast, the most refractory PDX to AMA was PDX #86 (time to PD 150d, 10d, 7d, for P, V, E, respectively); this PDX had a BRCA2 pathogenic mutation and consistent with the six prior lines of therapy (including PARPi), and being platinum-refractory, this HGSC had acquired a secondary somatic mutation in BRCA2, although the functional consequences have not been proven [Figures 1(c) and 3(c) and Tables 1 and 2].

Despite these HGSC cases being heavily pre-treated, with acquired resistance to platinum and three out of four BRCA1/2-mutated cases containing putative secondary mutations in BRCA1/2, efficacy was observed for AMA. Two out of four heavily pre-treated BRCA1/2-mutated PDX had sustained responses to eribulin (BRCA2-mutated #95, #931: time to PD > 120d and 91d, respectively) and the other two PDX had moderate responses (BRCA1-mutated #32, #217: time to PD 77d and 73d, respectively; Tables 1 and 2). Of note, platinum responses were much shorter, with time to PD of 7–14 days for all four of these BRCA1/2-mutated PDX.

AMAs were highly effective in HGSC PDX models despite the presence of poor prognostic biomarkers

To further characterize the HGSC PDX models, additional sequencing was carried out on patient and/or PDX samples, where available. Overall, PDX samples harboured the type of genomic profiles expected for HGSC, which were consistent with BROCA panel sequencing results: with ubiquitous TP53 mutation (14/14 cases), RB1 deletion (3/14 cases), PTEN alterations (2/14 cases) and NF1 mutation in one case [Figure 3(a)]. Established known poor prognostic oncogenic events were also identified in many samples; MYC amplification (4/14 cases), PIK3CA activating mutations or amplification (5/14 cases), CCNE1 amplification (4/14 cases) and CCND2 amplification in one case [Figures 1(c) and 3(a)]. Importantly, four PDX models (#29, #201, #95 and #32) harboured two oncogenic events related to treatment resistance [Figure 3(a)]. In addition, PDX #111 was shown to have >30 copies of CCNE1.

Although RB1 loss has been reported to be associated with prolonged overall survival in HGSC in association with BRCA1/2 mutation,58,59 we observed a deletion in RB1 in three platinum refractory cases of HGSC. Indeed, the most AMA sensitive of these three cases (sensitive to all three AMA), #198, did not contain a BRCA1/2 mutation. A second RB1-deleted case, which was sensitive to two out of three AMA, was BRCA2 mutated, but also contained a secondary mutation in BRCA2. The third RB1-deleted case was profoundly refractory to all AMA and contained loss of promoter methylation of BRCA1. A likely pathogenic mutation in RHOA was also identified in #198, the most AMA-sensitive RB1-deleted case. RHOA encodes the small GTPase, Ras homolog gene family member A (RhoA), 60 which plays a central role in regulating cell shape, polarity and locomotion and hence may be relevant for AMA response. This model also contained potentially sensitizing mutations in ARID1A and XRCC2.

Strikingly, the four HGSC PDX most sensitive to AMA (#201, #29, #198 and #95) harboured multiple molecular markers of drug resistance, such as aberrant expression of oncogenes (CCNE1, MYC and KRAS), as well as PI3K pathway activation (PIK3CA mutation/amplification) and apoptosis evasion [MCL1 and BCL2L1 amplification; Figure 3(a)]. By contrast, two of the four HGSC PDX most resistant/refractory to AMA (#32 and #86, both post-chemotherapy models) also harboured multiple molecular markers of drug resistance such as loss of a tumour suppressor gene (CDKN2A), aberrant oncogene expression (MYC amplification), as well as PI3K pathway activation [PIK3CA mutation or amplification; Figure 3(a)].

To determine whether CCNE1 and MYC amplification correlated with increased expression of Cyclin E1 and MYC, respectively, Western blotting was performed. Three PDX (#29, #111 and #169) had very high expression of Cyclin E1 and six PDX had moderate expression [Figure 3(b)]. These included the four models that harboured CCNE1 amplification [#29, #111: high expression, >8× amplification; #201, #931: moderate expression, #201 >8× amplification; Figure 3(a)]. The more AMA-sensitive PDX models had higher expression of Cyclin E1. Expression of MYC was detected at moderate levels in six PDX (#29, #95, #198, #111, #87 and #169) and correlated with the more AMA-sensitive models [Figure 3(b)]. Interestingly, PDX #95, which displayed the greatest sensitivity to AMA was the only model with MYC amplification that also expressed detectable MYC protein by Western analysis [Figure 3(b)]. The three other PDX with MYC amplification (#201, #148 and #32) had very low or undetectable levels of MYC by Western blotting [Figure 3(b)].

Drug resistance in PDX #86 is likely mediated by a transcriptional fusion involving ABCB1

Upregulation of MDR1 expression has previously been reported in post-treatment HGSC, as a result of a transcriptional fusion involving ABCB1.19,41 The SLC25A40-ABCB1 fusion is the most common fusion observed. 41 Therefore, the presence of an SLC25A40-ABCB1 fusion as well as total expression of the ABCB1 gene were assessed in all 14 PDX samples using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). A patient-derived cell line AOCS18.5, previously shown to be positive for the SLC25A40-ABCB1 fusion, 41 was used as a positive control. PDX #86 was the only PDX found to harbour the SLC25A40-ABCB1 fusion [Figure 3(c)]. This BRCA2-mutated PDX also had the highest expression of ABCB1, consistent with western blotting data showing high MDR1 expression [Figure 3(b) and (c)]. It was not possible to test all primary patient samples as sufficient pure tumour material was not available.

Response to AMAs is correlated with a high proliferative index

In addition to observing the high expression of proteins usually associated with cellular proliferation, such as Cyclin E1 and MYC, we also observed an intriguing association of staining with the proliferation marker, Ki-67, by IHC in response to AMA [Figure 3(d)]. Firstly, HGSC expressing higher levels of Cyclin E1 and MYC assessed by Western blotting (#201, #29, #95, #111, #931 and #87) were highly proliferative, as indicated by high levels of Ki-67 staining [Figure 3(d) and (e); high >60% Ki-67 positive]. Secondly, the four platinum-refractory PDX, all of which were sensitive for more than 100 days to all three AMA tested (#201, #29, #95 and #198) also had high Ki-67 staining. Only one of these AMA-sensitive PDX was BRCA1/2-mutated (PDX #95), with the other three being BRCA1/2 / /HR gene WT. Thirdly, three out of four of the more AMA-responsive BRCA1/2-mutated PDX had high levels of Ki-67 staining [#95, #931, #217: only #32 did not; Figure 3(d) and (e)].

By contrast, despite harbouring MYC amplification (although low MYC expression by Western blotting), PDX #148 and #32 each had Ki-67 expression which was in the lower range of our models [Figure 3(d) and (e)]. The BRCA2-mutated PDX #86, with an ABCB1 fusion, had low Ki-67 staining [Figure 3(d) and (e)]. Finally, the other two models (#13 and #169) with very low expression of Ki-67 were also very drug resistant.

Ki-67 staining was also performed on baseline patient HGSC tissue for 10 cases and this reflected the staining observed for PDX derived from those samples, apart from PDX #29 and #931 (low in baseline patient sample and high in PDX; Supplemental Figure S3). Therefore, the more AMA-sensitive HGSC PDX models had high proliferative indices, as evidenced by high Ki-67 staining.

Discussion

We demonstrated that the AMAs, eribulin and vinorelbine, were effective in platinum resistant or refractory HGSC PDX, to a similar degree as paclitaxel, which has been transformative in the treatment of HGSC. Importantly, this was observed in PDX derived from individuals with HGSC who had been heavily pre-treated, including with prior PARPi. Four out of eleven (36%) platinum refractory PDX were sensitive to all three AMA tested. Strikingly, three of these AMA-sensitive PDX had amplification of CCNE1, which is usually considered a marker of drug resistance perhaps in keeping with the observation in the ARIEL2 trial that HGSC with a CR or PR to the PARP inhibitor, rucaparib, could contain CCNE1 amplifications. 61

These findings reveal eribulin and vinorelbine to be additional chemotherapeutic agents of potential clinical utility in HGSC. In HGSC, first-line response to platinum chemotherapy alone is around 50%, 62 however, with the addition of paclitaxel, response rates increase to around 70%. 63 It has been hypothesized that carboplatin and paclitaxel may provide independent chances of response, rather than being synergistic. 64 As eribulin has an improved toxicity profile when compared with vinorelbine or paclitaxel, 65 potentially resulting in improved dose delivery and eribulin has effects on the tumour microenvironment which may be helpful, especially for HGSC with components of carcinosarcoma, 66 eribulin may provide a better second chance of response than does paclitaxel as a first-line platinum partner.

Of note, three PDX containing both a BRCA1/2 primary mutation, as well as a secondary BRCA1/2 mutation likely to restore the open reading frame, responded to eribulin, with one PDX responding to all three AMA tested and the other with sustained responses to eribulin. By contrast, the four most AMA-resistant PDX were developed from HGSC which harboured either putative secondary mutations of BRCA1/2 or loss of BRCA1 methylation. Despite the latter, these observations suggest there is potential for AMA efficacy in the post-PARPi setting, for which there is an urgent need for more therapeutic options.

In our PDX models, eribulin was as efficacious as paclitaxel, with 5/10 (50%) platinum-refractory PDX continuing under observation for >120 days (the end of the experiment) without evidence of tumour recurrence, despite having received only 21 days of eribulin treatment. Eribulin is a well-tolerated drug in the clinic with less neurotoxicity reported compared to paclitaxel, 65 and these data provide preclinical support for renewed exploration of eribulin in clinical trials of HGSC, which is particularly relevant given the recent demonstration of efficacy for a tolerable antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) of eribulin, including in HGSC. 67

Additional genomic profiling indicated that our PRR HGSC PDX cohort harboured multiple oncogenic events known to be associated with a poor prognosis, including PIK3CA aberrations in three PDX, and MYC amplifications in four PDX models. Unexpectedly, these poor prognostic events were more often seen in the PDX that exhibited greater sensitivity to AMA. Intriguingly, whether or not MYC or CCNE1 amplifications were present, overall higher expression of the encoded proteins was observed in AMA-sensitive PDX, compared with AMA-resistant/refractory PDX.

In the more AMA-sensitive PDX, a higher proliferative index, as assessed by Ki-67 staining, was also observed in the more AMA-sensitive HGSC PDX models. By contrast, the most drug-resistant PDX, which was refractory to platinum, paclitaxel, vinorelbine and eribulin, had very low expression of Ki-67. Whilst platinum resistance may be driven by oncogenic events, 19 such as CCNE1 (#29, #111, #169) and MYC (#87, #169) amplification or overexpression, this does not appear to be the case for AMA response. Consistent with this, a previous study found significantly higher tumour proliferation rates in HGSC patients with long progression-free and overall survival. 58 These data demonstrate high Ki-67 expression, with a cutoff observed in this study of >60% positive expression, to be an indicator of AMA sensitivity, and that this biomarker should be assessed in future clinical trials.

RB1 loss has been associated with prolonged overall survival in HGSC in association with BRCA1/2 mutation 58 ; however, the most AMA-sensitive RB1-deleted case did not have a BRCA1/2 mutation in our cohort. To better understand treatment outcomes, we looked at additional molecular features of these cases. RhoA has been reported to interact with microtubules to facilitate cytokinesis, 68 playing a central role in regulating cell shape, polarity and locomotion through its effect on actin polymerization, actomyosin contractility, cell adhesion and microtubule dynamics. Interestingly, a mutation was observed in RHOA, in the most AMA-sensitive RB1-deleted PDX. Therefore, we hypothesize that mutation of RHOA may have contributed to AMA sensitivity in this model. By contrast, the other two RB1-deleted PDX contained no such potentially drug-sensitizing mutations.

Over-expression of MDR1 is known to cause cellular efflux of many cancer therapeutics drugs, including paclitaxel and eribulin.69,70 ABCB1 fusions and upregulation of MDR1 have previously been reported in post-treatment HGSC.19,41 The presence of an SLC25A40-ABCB1 fusion provides the most likely resistance mechanism, for the BRCA2-mutated (primary and secondary mutations) PDX model, which was refractory not only to cisplatin but also to all three AMA tested.

In summary, we annotated a cohort of aggressive PRR HGSC PDX, demonstrating that AMA, including the clinically well-tolerated drug, eribulin, demonstrated impressive in vivo activity. We observed activity in BRCA1/2-mutated PDX models, despite these deriving from heavily pre-treated individuals, strikingly, some of whose HGSC harboured secondary BRCA1/2 mutations. We identified likely mechanisms of drug resistance to AMA, such as upregulation of MDR1 and the presence of additional oncogenic events, although over-expression of two of these, MYC and CYCLIN E, did not appear to correlate with AMA resistance. These data indicate that eribulin, which is well-tolerated and coming off patent, or its ADC, farletuzumab ecteribulin, should be prioritized for clinical trials, preferably early during the HGSC treatment journey, initially for no/poor response to platinum, or for individuals who have developed secondary mutations in BRCA1/2 in their HGSC following chemotherapy/PARPi. Importantly, high Ki-67 expression correlated with AMA sensitivity in PRR HGSC, either at baseline or after many prior therapeutic regimens and should be assessed as a biomarker in clinical trials.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tam-10.1177_17588359231208674 for The microtubule inhibitor eribulin demonstrates efficacy in platinum-resistant and refractory high-grade serous ovarian cancer patient-derived xenograft models by Gwo Yaw Ho, Cassandra J. Vandenberg, Ratana Lim, Elizabeth L. Christie, Dale W. Garsed, Elizabeth Lieschke, Ksenija Nesic, Olga Kondrashova, Gayanie Ratnayake, Marc Radke, Jocelyn S. Penington, Amandine Carmagnac, Valerie Heong, Elizabeth L. Kyran, Fan Zhang, Nadia Traficante, Ruby Huang, Alexander Dobrovic, Elizabeth M. Swisher, Orla McNally, Damien Kee, Matthew J. Wakefield, Anthony T. Papenfuss, David D. L. Bowtell, Holly E. Barker and Clare L. Scott in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-2-tam-10.1177_17588359231208674 for The microtubule inhibitor eribulin demonstrates efficacy in platinum-resistant and refractory high-grade serous ovarian cancer patient-derived xenograft models by Gwo Yaw Ho, Cassandra J. Vandenberg, Ratana Lim, Elizabeth L. Christie, Dale W. Garsed, Elizabeth Lieschke, Ksenija Nesic, Olga Kondrashova, Gayanie Ratnayake, Marc Radke, Jocelyn S. Penington, Amandine Carmagnac, Valerie Heong, Elizabeth L. Kyran, Fan Zhang, Nadia Traficante, Ruby Huang, Alexander Dobrovic, Elizabeth M. Swisher, Orla McNally, Damien Kee, Matthew J. Wakefield, Anthony T. Papenfuss, David D. L. Bowtell, Holly E. Barker and Clare L. Scott in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Stoev, R. Hancock and K. Barber for their technical assistance. We thank Eisai Inc. for supplying eribulin; Clovis Oncology for funding Foundation Medicine sequencing of PDX; Prof Sean Grimmond and colleagues for whole genome sequencing of #198, analysis performed by Papenfuss laboratory, WEHI. This work was made possible through the Australian Cancer Research Foundation. The Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command under DAMD17-01-1-0729, The Cancer Council Victoria, Queensland Cancer Fund, The Cancer Council New South Wales, The Cancer Council South Australia, The Cancer Council Tasmania and The Cancer Foundation of Western Australia (Multi-State Applications 191, 211 and 182) and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC; ID199600; ID400413 and ID400281). The Australian Ovarian Cancer Study gratefully acknowledges additional support from Ovarian Cancer Australia and the Peter MacCallum Foundation. The AOCS also acknowledges the cooperation of the participating institutions in Australia and acknowledges the contribution of the study nurses, research assistants and all clinical and scientific collaborators to the study. The complete AOCS Study Group can be found at www.aocstudy.org. We would like to thank all the individuals who participated in these research programmes.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Gwo Yaw Ho  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1195-2296

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1195-2296

Matthew J. Wakefield  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6624-4698

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6624-4698

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Gwo Yaw Ho, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia; Department of Medical Biology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia; The Royal Women’s Hospital, Parkville, VIC, Australia; School of Clinical Sciences, Monash University, Clayton Road, Clayton, VIC 3168, Australia.

Cassandra J. Vandenberg, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia; Department of Medical Biology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Ratana Lim, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Elizabeth L. Christie, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, VIC, Australia Sir Peter MacCallum Department of Oncology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Dale W. Garsed, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, VIC, Australia Sir Peter MacCallum Department of Oncology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Elizabeth Lieschke, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia; Department of Medical Biology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Ksenija Nesic, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia; Department of Medical Biology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Olga Kondrashova, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia; Department of Medical Biology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia; QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute, Herston, QLD, Australia.

Gayanie Ratnayake, The Royal Women’s Hospital, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Marc Radke, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Jocelyn S. Penington, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia

Amandine Carmagnac, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Valerie Heong, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Elizabeth L. Kyran, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia

Fan Zhang, Department of Surgery, Austin Health, University of Melbourne, Heidelberg, VIC, Australia.

Nadia Traficante, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; Sir Peter MacCallum Department of Oncology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Ruby Huang, National Taiwan University, Taipei.

Alexander Dobrovic, Department of Surgery, Austin Health, University of Melbourne, Heidelberg, VIC, Australia.

Elizabeth M. Swisher, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Orla McNally, The Royal Women’s Hospital, Parkville, VIC, Australia; Sir Peter MacCallum Department of Oncology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Damien Kee, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia; Sir Peter MacCallum Department of Oncology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia; Department of Medical Oncology, Austin Hospital, Heidelberg, VIC, Australia.

Matthew J. Wakefield, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Anthony T. Papenfuss, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia Department of Medical Biology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia; Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; Sir Peter MacCallum Department of Oncology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

David D. L. Bowtell, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; Sir Peter MacCallum Department of Oncology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Holly E. Barker, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia; Department of Medical Biology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Clare L. Scott, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, Parkville, VIC, Australia; Department of Medical Biology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia; The Royal Women’s Hospital, Parkville, VIC, Australia; Sir Peter MacCallum Department of Oncology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Patient tumour specimens under the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study or WEHI Stafford Fox Rare Cancer Programme. Additional human ethics approval was obtained from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (WEHI; HREC #10/05 and #G16/02). Informed consent was obtained from all patients, and all experiments were performed according to the human ethics guidelines.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Gwo Yaw Ho: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Cassandra J. Vandenberg: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Ratana Lim: Data curation; Resources.

Elizabeth L. Christie: Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Dale W. Garsed: Data curation; Writing – review & editing.

Elizabeth Lieschke: Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Ksenija Nesic: Investigation; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Olga Kondrashova: Data curation; Investigation; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Gayanie Ratnayake: Investigation; Resources.

Marc Radke: Resources.

Jocelyn S. Penington: Data curation; Methodology; Resources.

Amandine Carmagnac: Data curation; Resources.

Valerie Heong: Conceptualization; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Elizabeth L. Kyran: Data curation; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Fan Zhang: Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Nadia Traficante: Investigation; Project administration; Resources.

Ruby Huang: Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Alexander Dobrovic: Data curation; Writing – review & editing.

Elizabeth M. Swisher: Writing – review & editing.

Orla McNally: Methodology; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Damien Kee: Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Matthew J. Wakefield: Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Writing – review & editing.

Anthony T. Papenfuss: Resources; Software; Writing – review & editing.

David D. L. Bowtell: Conceptualization; Writing – review & editing.

Holly E. Barker: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Supervision; Writing – original draft.

Clare L. Scott: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Resources; Supervision; Writing – original draft.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by fellowships and grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council [NHMRC Australia; Project Grant 1081178 (DDB, CLS), Senior Research Fellowship 1116955 (ATP); Investigator Grants 2009783 (CLS), 2008631 (OK)]; the Stafford Fox Medical Research Foundation (CJV, RL, ATP, CLS and HEB); the Lorenzo and Pamela Galli Medical Research Trust (ATP); Cancer Council Victoria (Sir Edward Dunlop Fellowship in Cancer Research, CLS); the Victorian Cancer Agency [Clinical Fellowships CRF10-20, CRF16014 (CLS)]; Herman Trust University of Melbourne (CLS); CRC Cancer Therapeutics [Grant support (CLS), PhD top-up scholarship (GYH)]; Australian Commonwealth Government and the University of Melbourne [Research Training Programme Scholarship (GYH)]; Monash University, School of Clinical Sciences [Early Career Clinician-scientist Fellowship (GYH)]; Ovarian Cancer Australia (PhD Scholarship to VH); The research benefitted by support from the Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support and Australian Government NHMRC Independent Research Institute Infrastructure Support.

Eisai Inc. provided drug support for this study. DDB declares Consultant for Exo Therapeutics. CLS declares Advisory Boards for AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology, Roche, Eisai Inc., Sierra Oncology, Takeda, MSD, EpsilaBio and Grant/Research support from Clovis Oncology, Eisai Inc., Sierra Oncology, Roche, Beigene, AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim. EMS declares Scientific Advisory Board for Ideaya Biosciences and DSMB role for Novartis. Other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Availability of data and materials: The following data sets have been deposited in the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA) under accession number EGAS0000xxx: WES data for PDX tumours #87, #95, #32, #217 and #86, or WGS data for patient samples #1198. A data transfer agreement is required.

References

- 1. Jelovac D, Armstrong DK. Recent progress in the diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2011; 61: 183–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ozols RF, Bundy BN, Greer BE, et al. Phase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 3194–3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Piccart MJ, Bertelsen K, James K, et al. Randomized intergroup trial of cisplatin-paclitaxel versus cisplatin-cyclophosphamide in women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: three-year results. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92: 699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bowtell DD, Böhm S, Ahmed AA, et al. Rethinking ovarian cancer II: reducing mortality from high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2015; 15: 668–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Matulonis UA, Sood AK, Fallowfield L, et al. Ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2: 16061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ahmed AA, Etemadmoghadam D, Temple J, et al. Driver mutations in TP53 are ubiquitous in high grade serous carcinoma of the ovary. J Pathol 2010; 221: 49–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Testa U, Petrucci E, Pasquini L, et al. Ovarian cancers: genetic abnormalities, tumor heterogeneity and progression, clonal evolution and cancer stem cells. Medicines 2018; 5: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 2011; 474: 609–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kanchi KL, Johnson KJ, Lu C, et al. Integrated analysis of germline and somatic variants in ovarian cancer. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Norquist BS, Brady MF, Harrell MI, et al. Mutations in homologous recombination genes and outcomes in ovarian carcinoma patients in GOG 218: an NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Clin Cancer Rev 2018; 24: 777–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pennington KP, Walsh T, Harrell MI, et al. Germline and somatic mutations in homologous recombination genes predict platinum response and survival in ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20: 764–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morgan RD, Clamp AR, Evans DGR, et al. PARP inhibitors in platinum-sensitive high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2018; 81: 647–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Banerjee S, Moore KN, Colombo N, et al. Maintenance olaparib for patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer and a BRCA mutation (SOLO1/GOG 3004): 5-year follow-up of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2021; 22: 1721–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 2495–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stuart GC, Kitchener H, Bacon M, et al.; Participants of 4th Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference (OCCC) and Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup. 2010 Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) consensus statement on clinical trials in ovarian cancer: report from the Fourth Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2011; 21: 750–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bouwman P, Jonkers J. Molecular pathways: how can BRCA-mutated tumors become resistant to PARP inhibitors? Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20: 540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kondrashova O, Nguyen M, Shield-Artin K, et al. Secondary somatic mutations restoring RAD51C and RAD51D associated with acquired resistance to the PARP inhibitor Rucaparib in high-grade ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Discov 2017; 7: 984–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lord CJ, Ashworth A. Mechanisms of resistance to therapies targeting BRCA-mutant cancers. Nat Med 2013; 19: 1381–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patch AM. Whole-genome characterization of chemoresistant ovarian cancer. Nature 2015; 521: 489–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sakai W, Swisher EM, Karlan BY, et al. Secondary mutations as a mechanism of cisplatin resistance in BRCA2-mutated cancers. Nature 2008; 451: 1116–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burdett NL, Willis MO, Alsop K, et al. Multiomic analysis of homologous recombination-deficient end-stage high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat Genet 2023; 55: 437–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kondrashova O. Methylation of all BRCA1 copies predicts response to the PARP inhibitor rucaparib in ovarian carcinoma. Nat Commun 2018; 9: 3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nesic K, Kondrashova O, Hurley RM, et al. Acquired RAD51C promoter methylation loss causes PARP inhibitor resistance in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res 2021; 81: 4709–4722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pogge von Strandmann E, Reinartz S, Wager U, et al. Tumor-host cell interactions in ovarian cancer: pathways to therapy failure. Trends Cancer 2017; 3: 137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lindemann K, Gao B, Mapagu C, et al.; Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. Response rates to second-line platinum-based therapy in ovarian cancer patients challenge the clinical definition of platinum resistance. Gynecol Oncol 2018; 150: 239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pujade-Lauraine E, Hilpert F, Weber B, et al. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: the AURELIA open-label randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 1302–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ganguly S, Williams LS, Palacios IM, et al. Cytoplasmic streaming in Drosophila oocytes varies with kinesin activity and correlates with the microtubule cytoskeleton architecture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: 15109–15114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brouhard GJ, Rice LM. Microtubule dynamics: an interplay of biochemistry and mechanics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018; 19: 451–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arnal I, Wade RH. How does taxol stabilize microtubules? Curr Biol 1995; 5: 900–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]