Abstract

Objective

Caesarean section is associated with higher blood loss than vaginal delivery. This study was performed to compare the safety and efficacy of preoperative versus postoperative rectal and sublingual misoprostol use for prevention of blood loss in women undergoing elective caesarean delivery.

Methods

Eligible patients in Southeast Nigeria were randomly classified into those that received 600 µg of preoperative rectal, postoperative rectal, preoperative sublingual, and postoperative sublingual misoprostol. All patients received 10 units of intravenous oxytocin immediately after delivery. Data were analysed with SPSS Version 23.

Results

Preoperative sublingual misoprostol use caused the highest postoperative packed cell volume, least change in the packed cell volume, and lowest intraoperative blood loss. Preoperative sublingual and rectal misoprostol use was associated with better haematological indices and maternal outcomes than postoperative use by these routes. However, preoperative sublingual and rectal use caused more maternal side effects than postoperative use by these routes.

Conclusion

Preoperative sublingual misoprostol was associated with the most favourable haematological indices. Although preoperative sublingual and rectal misoprostol use caused more maternal side effects, these routes were associated with better haematological indices and maternal outcomes than postoperative sublingual and rectal misoprostol use.

Keywords: Caesarean section, blood loss, preoperative, postoperative, sublingual misoprostol, rectal misoprostol, Nigeria

Introduction

Caesarean section has contributed to reduction of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. However, this procedure is associated with complications, including intraoperative haemorrhage, postpartum haemorrhage (PPH), infection, and postoperative adhesion formation. The risk of such complications underscores the need to take necessary precautions to achieve safe delivery. Globally, the incidence of caesarean deliveries has been trending upward. Approximately 21.1% of women worldwide deliver by caesarean section, with regional variations ranging from 5.0% in sub-Saharan Africa to 42.8% in Latin America and the Caribean. 1 The 2018 Nigerian Demographic and Health Survey showed that the rate of caesarean section was 3%. 2

PPH accounts for 50% of maternal mortality in poor countries. 3 Caesarean section is associated with twice the amount of blood loss as vaginal delivery. 4 Intraoperative blood loss is a complication that can occur during caesarean section. In 2011, a systematic review of 21 studies showed that the rate of intraoperative blood loss and blood transfusion increased as the incidence of caesarean deliveries increased. 5 Increased intraoperative blood loss can lead to increased maternal morbidity and mortality.

Uterotonics are used to reduce intraoperative and postoperative bleeding during caesarean section. Uterotonics comprise oxytocin, methylergometrine, and prostaglandins. Misoprostol is a prostaglandin E1 analogue that is commonly used in obstetrics for the prevention and reduction of blood loss. 6 Misoprostol is affordable and readily available, and it does not require any special preservation. It can be administered through multiple routes (vaginal, rectal, sublingual, or oral) and has a wide safety margin, making it a standard preventive and treatment option for PPH especially in resource-poor countries. 7 The mean time to reaching the peak concentration of sublingual and rectal misoprostol is 30 minutes and 40 to 65 minutes, respectively. 8 , 9 The onset of action and duration of action of sublingual misoprostol are 11 minutes and 3 hours, respectively, 10 and those of rectal misoprostol are 100 minutes and 4 hours, respectively. 10 The slower onset of action and longer duration of rectal misoprostol within the circulation may be responsible for its usefulness in reduction of intraoperative and postoperative blood loss during caesarean section. The adverse effects of misoprostol, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, fever, and chills, are dose-dependent. The recommended dose of misoprostol for prevention of PPH is 600 µg. 11

Previous studies in Benin, Nigeria, and Egypt showed that that the mean intraoperative blood loss volume was significantly lower in the sublingual than rectal group.12–15 However, sublingual misoprostol use had more maternal side effects than rectal use.12–15 A randomised controlled trial by Youssef et al. 16 comparing preoperative and postoperative sublingual misoprostol for prevention of PPH during caesarean section showed that the mean intraoperative and postoperative blood loss volumes were lower in the preoperative than postoperative group. However, a significantly higher proportion of patients who received sublingual misoprostol preoperatively had fever and chills than patients who received sublingual misoprostol postoperatvely. 16 A randomised controlled trial on the safety and efficacy of preoperative rectal misoprostol for prevention of intraoperative and postoperative blood loss in patients undergoing elective caesarean delivery by Maged et al. 17 in Egypt showed that the intraoperative and 24-hour postoperative blood loss volumes were significantly lower in the preoperative than postoperative misoprostol group. The preoperative misoprostol group also had a higher postoperative haemoglobin concentration than the postoperative group. Moreover, a significantly higher proportion of patients in the postoperative group needed additional uterotonics. 17

A Medline search revealed very few studies to date comparing preoperative versus postoperative misoprostol use during caesarean section among pregnant women. Most of these studies were performed in the Middle East and Asia. The paucity of studies on this subject matter, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, underscores the need for such research in Southeast Nigeria. Therefore, the present study was performed to compare the safety and efficacy of preoperative versus postoperative misoprostol for the prevention of intraoperative and postoperative blood loss in women undergoing elective caesarean delivery. The findings from this study may strengthen or refute the existing evidence.

Materials and methods

Southeast Nigeria is located in the southeastern part of Nigeria and comprises five states: Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, and Imo States. This region is predominantly Igbo and has a population of 16.4 million people based on a 2006 population census. 18

The University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital (UNTH) is a tertiary hospital in Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu State. It has a functional obstetrics and gynaecology department and serves as a referral centre for other hospitals in Nigeria and Cameroun.

Enugu State University of Science and Technology Teaching Hospital (ESUTTH) in Park Lane, Enugu State is a tertiary hospital located in the Enugu metropolis. It has a functional obstetrics and gynaecology unit and receives referrals from other hospitals in Enugu State and neighbouring states.

Alex Ekwueme Federal University Teaching Hospital, Abakaliki (AEFUTHA) is also a tertiary hospital in Abakaliki, Ebonyi State. It has a functional obstetrics and gynaecology department. AEFUTHA receives referrals from other hospitals in Ebonyi State and neighbouring states.

Bishop Shanahan Hospital (BSH) is a secondary care Catholic hospital in Nsukka. The hospital has specialists in obstetrics and gynaecology, general surgery, urology, orthopaedic surgery, cardiology, endocrinology and paediatrics. The hospital receives referrals from neighbouring communities in Enugu, Anambra, Kogi, and Benue States.

The study population comprised pregnant women who underwent elective caesarean section at these four hospitals. The proportion of patients recruited from each of the hospitals was based on the patient load at each hospital.

Study design

In this multi-centre prospective single-blind randomised controlled trial, semi-structured questionnaires were used to collate information from consenting eligible pregnant women who were scheduled for elective caesarean section at term (gestational age of 37–41 weeks). A computer was used to generate random numbers, and each number was placed in a sealed brown envelope. Each number corresponded to Group 1, 2, 3, or 4, up to the sample size. Written consent was obtained from each eligible participant. Patients in Group 1 (preoperative rectal misoprostol) received 600 µg of rectal misoprostol (Cytotec; Pfizer, New York, NY, USA) after spinal anaesthesia and urethral catheterisation. Patients in Group 2 (postoperative rectal misoprostol) received 600 µg of rectal misoprostol (Cytotec; Pfizer) immediately after abdominal closure and vaginal cleaning. Patients in Group 3 (preoperative sublingual misoprostol) received 600 µg of sublingual misoprostol (Cytotec; Pfizer) after spinal anaesthesia and urethral catheterisation. Patients in Group 4 (postoperative sublingual misoprostol) received 600 µg of sublingual misoprostol (Cytotec; Pfizer) immediately after abdominal closure and vaginal cleaning. The preoperative and postoperative packed cell volume (PCV) were checked at admission and 24 hours after caesarean section, respectively. All patients received 10 units of intravenous oxytocin immediately after delivery. The intraoperative blood loss volume was calculated using the following formula 4 :

Intraoperative blood loss

= estimated blood volume

× (preoperative haematocrit

− postoperative haematocrit)/ preoperative haematocrit.

The estimated blood volume was calculated as the patient’s weight in kilograms ×85. 17 The second method of calculation involved weighing the abdominal sponges both before use and after the procedure. The intraoperative blood loss was calculated by determining the difference in the weight of the sponges before and after caesarean section and adding the volume of blood inside the suction apparatus. For the purpose of this study, the intraoperative blood loss was calculated by determining the average blood loss derived from the two methods. Both groups of patients were followed up for 24 hours after caesarean section.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was the volume of intraoperative blood loss.

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures were occurrence of primary PPH (bleeding of >1000 mL within 24 hours after caesarean section), use of extra uterotonics, use of blood transfusion, occurrence of shivering, pyrexia (>38°C), headache, nausea and vomiting, neonatal outcomes (Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes), and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit.

Blinding

The researchers and trained research assistants who measured the intraoperative blood loss and followed the patients for up to 24 hours after caesarean section were blinded to each patient’s intervention. This was achieved by ensuring that the investigators were not present during the intervention and were only called to check the outcome measures at the end of surgery.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated using the sample size calculation technique typically used in clinical superiority studies when the outcome measure was dichotomous 19 :

N = minimum sample size

Z1−α = 1.645

Z1−β = 0.845

P1 = percentage change in PCV in the postoperative misoprostol group = 17.08% 17 and P2 = percentage change in PCV in the preoperative misoprostol group = 6.05% 17

P = average proportion of exposed cases =proportion of exposed cases + proportion of control exposed/2

P = P1 + P2/2

P = (0.1708 + 0.0605)/2 = 0.11565

1 – P = 1 − 0.11565 = 0.88435

d = real difference between two treatment effects = (0.1708 − 0.06050) = 0.1103

δ0 = clinically acceptable margin = 0.02

d − δ0 = 0.1103 − 0.02 = 0.0903

N = [2(1.645 + 0.845) 2 × 0.1165 × 0.88435]/(0.0903) 2

N = 157

After adding 10% attrition, N = 173

Therefore, each of the 4 groups comprised 173 patients.

Inclusion criteria

All consenting pregnant women who had singleton pregnancies at 37 to 41 weeks’ gestation and had no medical disorders were included in the study. All patients received spinal anaesthesia before the caesarean delivery.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were hypertensive disease in pregnancy, multiple gestation, diabetes mellitus, asthma, sickle cell anaemia, liver disease, cardiac disorder, preterm delivery, gestational age of >41 weeks, scheduled for emergency caesarean section, pregnancy coexisting with uterine fibroid, allergy to prostaglandins, general anaesthesia, and refusal to give consent to participate in the study.

Data analysis

The data were analysed using SPSS Version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables were analysed with the chi-square test, and continuous variables were analysed by analysis of variance. Tukey’s post-hoc analysis was used to determine the actual variables that were statistically significant from the analysis of variance. P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The reporting of this study conforms to the CONSORT statement. 20

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee, UNTH (registration number: NHREC/05/01/2008B-FWA00002458-1RB00002323, date: 15 November 2021). Institutional permission for the study was further obtained from ESUTTH, AEFUTHA, and BSH. This randomised controlled trial was registered by the Pan African Clinical Trials Registry (identification number: PACTR202201537109837, date: 6 January 2022). The trial was performed from 10 January 2022 to 23 December 2022.

Results

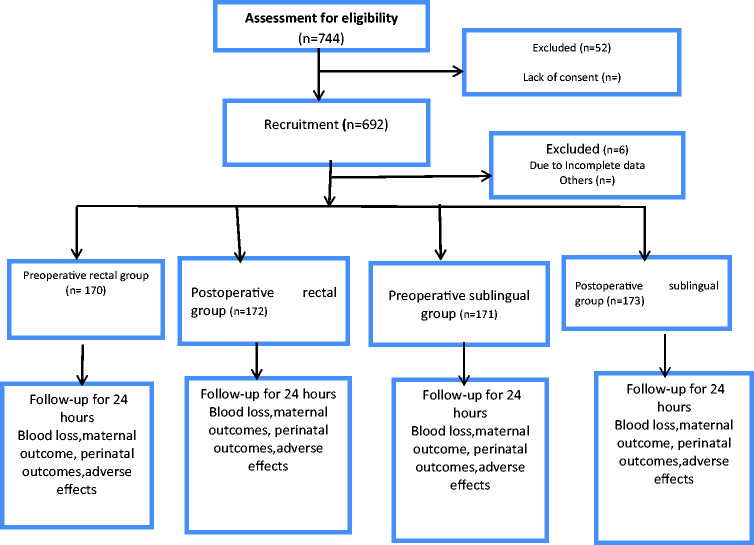

In total, 262, 194, 140, and 96 patients were recruited from AEFUTHA, ESUTTH, BSH, and UNTH, respectively. Figure 1 shows the flow chart of participant selection. Data were analysed for 171, 173, 170, and 172 patients in Groups 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Table 1 shows a comparison of the patients’ sociodemographic characteristics. There was no statistically significant difference in age, parity, residential address, occupation, or education among the four groups. Table 2 shows a comparison of the obstetric parameters among Groups 1, 2, 3, and 4. There was no statistically significant difference in the surgeons’ skill level, type of incision, indication for caesarean section, gestational age, intraoperative time, or patients’ weight among the four groups. Table 3 shows a comparison of the haematological parameters among Groups 1, 2, 3, and 4. There was no statistically significant difference in the preoperative PCV among the patients. However, there was a statistically significant difference in the mean postoperative PCV and mean change in PCV among the patients (P < 0.01). Table 4 shows the results of Tukey’s honestly significant difference post-hoc test for comparison of haematological parameters among Groups 1, 2, 3, and 4. The mean postoperative PCV was significantly higher in patients who received preoperative sublingual than preoperative rectal misoprostol (P = 0.034), preoperative sublingual than postoperative rectal misoprostol (P < 0.001), and postoperative sublingual than postoperative rectal misoprostol (P = 0.029). The mean change in PCV was significantly smaller in patients who received preoperative sublingual than preoperative rectal misoprostol, postoperative sublingual than preoperative rectal misoprostol, preoperative sublingual than postoperative rectal misoprostol, postoperative sublingual than postoperative rectal misoprostol, and preoperative sublingual than postoperative sublingual misoprostol (P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient selection.

Table 1.

Comparison of patients’ sociodemographic characteristics.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Group 1 (n = 170) | Group 2 (n = 172) | Group 3 (n = 171) | Group 4 (n = 173) | χ2 | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 29.58 ± 5.00 | 29.30 ± 5.94 | 29.65 ± 4.96 | 29.47 ± 5.00 | 0.145 | 0.93 | |

| Mean parity | 2.40 ± 1.40 | 2.37 ± 1.43 | 2.39 ± 1.43 | 2.33 ± 1.48 | 0.080 | 0.97 | |

| Residence | 2.548 | 0.46 | |||||

| Rural | 47 (27.6) | 30 (17.4) | 29 (17.0) | 47 (27.2) | |||

| Urban | 123 (72.4) | 142 (82.6) | 142 (83.0) | 126 (72.8) | |||

| Occupation | 16.209 | 0.37 | |||||

| Unemployed | 52 (30.6) | 65 (37.8) | 41 (24.0) | 32 (18.5) | |||

| Employed | 118 (69.4) | 107 (62.2) | 130 (76.0) | 141 (81.5) | |||

| Educational qualification | 10.587 | 0.31 | |||||

| Primary | 14 (8.3) | 3 (1.8) | 6 (3.5) | 11 (6.4) | |||

| Secondary | 57 (33.5) | 94 (54.7) | 59 (34.5) | 79 (45.7) | |||

| Tertiary | 99 (58.3) | 75 (43.6) | 106 (62.0) | 83 (48.0) |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

Table 2.

Comparison of patients’ obstetric parameters.

| Obstetric parameters | Group 1 (n = 170) | Group 2 (n = 172) | Group 3 (n = 171) | Group 4 (n = 173) | χ2 | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeon | 6.053 | 0.42 | |||||

| Consultants | 33 (19.4) | 47 (27.3) | 65 (38.0) | 54 (31.2) | |||

| Senior registrars | 137 (80.6) | 135 (72.7) | 106 (62.0) | 119 (68.8) | |||

| Type of incision | 0.147 | 0.70 | |||||

| Subumbilical midline | 25 (14.7) | 23 (13.4) | 20 (11.7) | 26 (15.0) | |||

| Pfannenstiel | 145 (85.3) | 149 (86.6) | 151 (88.3) | 147 (85.0) | |||

| Indications for CS | 2.912 | 0.09 | |||||

| Two or more previous CS procedures | 97 (57.1) | 107 (62.2) | 111 (64.9) | 125 (72.3) | |||

| Foetal macrosomia | 12 (7.1) | 9 (5.2) | 18 (10.5) | 15 (8.7) | |||

| Malpresentation | 18 (10.6) | 15 (8.8) | 8 (4.7) | 13 (7.5) | |||

| Maternal request | 43 (25.3) | 45 (26.2) | 34 (19.9) | 20 (11.6) | |||

| Mean gestational age (days) | 268.08 ± 6.97 | 268.86 ± 7.01 | 268.36 ± 6.71 | 269.13 ± 6.35 | 0.881 | 0.45 | |

| Mean intraoperative time (minutes) | 61.67 ± 17.58 | 61.47 ± 19.15 | 61.41 ± 19.48 | 61.98 ± 19.93 | 0.031 | 0.99 | |

| Mean patient weight (kg) | 80.46 ± 14.83 | 81.32 ± 12.08 | 81.38 ± 8.12 | 81.79 ± 9.84 | 0.405 | 0.75 |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

CS, caesarean section.

Table 3.

Comparison of haematological parameters among Groups 1, 2, 3, and 4.

| Haematological parameters | Group 1 (n = 170) | Group 2 (n = 172) | Group 3 (n = 171) | Group 4 (n = 173) | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative PCV (%) | 33.92 ± 2.97 | 33.34 ± 2.00 | 33.47 ± 1.71 | 33.56 ± 1.86 | 1.467 | 0.22 |

| Postoperative PCV (%) | 28.53 ± 1.68 | 28.07 ± 2.73 | 29.17 ± 2.34 | 28.72 ± 1.79 | 7.513 | <0.01 |

| Change in PCV | 15.89 ± 2.29 | 15.81 ± 1.73 | 12.85 ± 2.34 | 14.42 ± 1.02 | 95.208 | <0.01 |

| Mean blood loss by formula | 482.60 ± 120.77 | 525.90 ± 128.65 | 435.36 ± 98.85 | 497.78 ± 115.35 | 18.151 | <0.01 |

| Mean blood loss by gravimetric method | 603.72 ± 298.33 | 677.53 ± 300.56 | 590.18 ± 215.91 | 635.57 ± 310.58 | 3.2065 | 0.0227 |

| Mean blood loss (mL) | 541.46 ± 287.04 | 612.17 ± 258.16 | 512.26 ± 166.57 | 563.33 ± 286.95 | 4.707 | <0.01 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

PCV, packed cell volume.

Table 4.

Tukey’s honestly significant difference post-hoc test for comparison of haematological parameters among Groups 1, 2, 3, and 4.

| Haematological parameters | Group comparison | Mean difference | 95% CI (lower, upper) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean postoperative PCV (%) | Preop rectal vs. Postop rectal | −0.4600 | −1.0663, 0.1463 | 0.2069 |

| Preop rectal vs. Preop sublingual | 0.6400 | 0.0329, 1.2471 | 0.0342 | |

| Preop rectal vs. Postop sublingual | 0.1900 | −0.4154, 0.7954 | 0.8507 | |

| Postop rectal vs. Preop sublingual | 1.1000 | 0.4946, 1.7054 | <0.0001 | |

| Postop rectal vs. Postop sublingual | 0.6500 | 0.0464, 1.2536 | 0.0290 | |

| Preop sublingual vs. Postop sublingual | −0.4500 | −1.0545, 0.1545 | 0.2219 | |

| Mean change in PCV | Preop rectal vs. Postop rectal | −0.0800 | −0.6139, 0.4539 | 0.9805 |

| Preop rectal vs. Preop sublingual | −3.0400 | −3.5747, −2.5053 | <0.0001 | |

| Preop rectal vs. Postop sublingual | −1.4700 | −2.0032, −0.9368 | <0.0001 | |

| Postop rectal vs. Preop sublingual | −2.9600 | −3.4931, −2.4269 | <0.0001 | |

| Postop rectal vs. Postop sublingual | −1.3900 | −1.9216, −0.8584 | <0.0001 | |

| Preop sublingual vs. Postop sublingual | 1.5700 | 1.0376, 2.1024 | <0.0001 |

PCV, packed cell volume; CI, confidence interval; Preop, preoperative; Postop, postoperative.

Table 5 shows the results of Tukey’s honestly significant difference post-hoc test for comparison of intraoperative blood loss among Groups 1, 2, 3, and 4. The mean blood loss volume calculated by the formula was significantly smaller in patients who received preoperative rectal than postoperative rectal misoprostol (P = 0.003), preoperative sublingual than preoperative rectal misoprostol (P = 0.001), preoperative sublingual than postoperative rectal misoprostol (P < 0.001), and preoperative sublingual than postoperative sublingual misoprostol (P < 0.001). The mean blood loss volume determined by the gravimetric method was significantly smaller in patients who received preoperative sublingual than postoperative rectal misoprostol (P = 0.023). The mean total blood loss was also significantly lower in patients who received preoperative sublingual than postoperative rectal misoprostol (P = 0.002). Table 6 shows a comparison of the maternal and perinatal outcomes among Groups 1, 2, 3, and 4. The birth weight of neonates in Group 3 was significantly higher than that of neonates in the other groups (P < 0.01). However, there was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of PPH, use of extra uterotonics, blood transfusion, Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes, or neonatal intensive care unit admission.

Table 5.

Tukey’s honestly significant difference post-hoc test for comparison of intraoperative blood loss among Groups 1, 2, 3, and 4.

| Blood loss | Group comparison | Mean difference | 95% CI (lower, upper) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean blood loss by formula (mL) | Preop rectal vs. Postop rectal | 43.30 | 10.8828, 75.7172 | 0.0034 |

| Preop rectal vs. Preop sublingual | −47.24 | −79.7043, −14.7757 | 0.0011 | |

| Preop rectal vs. Postop sublingual | 15.18 | −17.1906, 47.5506 | 0.6224 | |

| Postop rectal vs. Preop sublingual | −90.54 | −122.9095, −58.1705 | <0.0001 | |

| Postop rectal vs. Postop sublingual | −28.12 | −60.3955, 4.1555 | 0.1127 | |

| Preop sublingual vs. Postop sublingual | 62.42 | 30.0972, 94.7428 | <0.0001 | |

| Mean blood loss by gravimetric method (mL) | Preop rectal vs. Postop rectal | 73.81 | −5.2627, 152.8827 | 0.0773 |

| Preop rectal vs. Preop sublingual | −13.54 | −92.7275, 65.6475 | 0.9715 | |

| Preop rectal vs. Postop sublingual | 31.85 | −47.1090, 110.8090 | 0.7269 | |

| Postop rectal vs. Preop sublingual | −87.35 | −166.3063, −8.3937 | 0.0233 | |

| Postop rectal vs. Postop sublingual | −41.96 | −120.6871, 36.7671 | 0.5173 | |

| Preop sublingual vs. Postop sublingual | 45.39 | −33.4525, 124.2325 | 0.4488 | |

| Mean total blood loss (mL) | Preop rectal vs. Postop rectal | 70.7100 | −0.1724, 141.5924 | 0.0508 |

| Preop rectal vs. Preop sublingual | −29.2000 | −100.1853, 41.7853 | 0.7146 | |

| Preop rectal vs. Postop sublingual | 21.8700 | −48.9105, 92.6505 | 0.8565 | |

| Postop rectal vs. Preop sublingual | −99.9100 | −170.6881, −29.1319 | 0.0017 | |

| Postop rectal vs. Postop sublingual | −48.84 | −119.4126, 21.7326 | 0.2836 | |

| Preop sublingual vs. Postop sublingual | 51.0700 | −19.6060, 121.7460 | 0.2462 |

NB: Mean total blood loss was the average of intraoperative blood loss by formula and gravimetric method.

CI, confidence interval; Preop, preoperative; Postop, postoperative.

Table 6.

Comparison of maternal and perinatal outcomes among Groups 1, 2, 3, and 4.

| Outcomes | Group 1 (n = 170) | Group 2 (n = 172) | Group 3 (n = 171) | Group 4 (n = 173) | χ2 | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary PPH | 7.814 | 0.25 | |||||

| Yes | 9 (5.3) | 29 (16.9) | 9 (5.3) | 25 (14.5) | |||

| No | 161 (94.7) | 143 (83.1) | 162 (94.7) | 148 (85.5) | |||

| Use of extra uterotonics | 2.375 | 0.88 | |||||

| Yes | 28 (16.5) | 30 (17.4) | 18 (10.5) | 25 (14.5) | |||

| No | 142 (83.5) | 142 (82.6) | 153 (89.5) | 148 (85.5) | |||

| Use of blood transfusion | 5.295 | 0.51 | |||||

| Yes | 5 (2.9) | 18 (10.5) | 6 (3.5) | 14 (8.1) | |||

| No | 165 (97.1) | 154 (89.5) | 165 (96.5) | 159 (91.9) | |||

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.26 ± 0.45 | 3.15 ± 0.47 | 3.40 ± 0.60 | 3.25 ± 0.49 | 7.080 | <0.01 | |

| 1-minute Apgar score | 7.89 ± 1.70 | 8.24 ± 1.49 | 8.03 ± 1.88 | 8.00 ± 1.86 | 1.211 | 0.31 | |

| 5-minute Apgar score | 9.38 ± 1.64 | 9.57 ± 1.44 | 9.25 ± 1.97 | 9.40 ± 1.62 | 1.052 | 0.37 | |

| NICU admission | 0.170 | 0.98 | |||||

| Yes | 33 (19.4) | 30 (17.4) | 35 (20.5) | 32 (18.5) | |||

| No | 137 (81.6) | 142 (82.6) | 136 (79.5) | 141 (81.5) |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

PPH, postpartum haemorrhage; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

A comparison of the maternal and perinatal outcomes between Groups 1 and 2 is shown in Table 7. The incidence of primary PPH, use of extra uterotonics, Apgar score at 1 minute, and birth weight of neonates were significantly higher in patients who received postoperative rectal than preoperative rectal misoprostol (P < 0.05). Table 8 shows a comparison of the maternal and perinatal outcomes between Groups 3 and 4. The incidence of primary PPH was significantly higher in patients who received postoperative sublingual than preoperative sublingual misoprostol (P = 0.004). However, the mean birth weight of neonates was significantly higher among mothers who received preoperative sublingual than postoperative sublingual misoprostol (P = 0.012). Table 9 shows a comparison of the maternal side effects of the interventions among Groups 1, 2, 3, and 4. The incidence of nausea was significantly higher in Group 1 than in the other groups. Table 10 shows a comparison of the maternal side effects of the interventions between Groups 1 and 2. The incidences of headache and vomiting were significantly higher in patients who received preoperative rectal than postoperative rectal misoprostol (P < 0.05). However, the incidence of shivering was higher in those who received postoperative rectal than preoperative rectal misoprostol (P < 0.001). Table 11 shows a comparison of the maternal side effects of the interventions between Groups 3 and 4. The incidence of nausea was significantly higher in patients who received preoperative sublingual than postoperative sublingual misoprostol (P < 0.001).

Table 7.

Comparison of maternal and perinatal outcomes between Groups 1 and 2.

| Outcomes | Group 1 (n = 170) | Group 2 (n = 172) | χ2 | 95% CI (lower, upper) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary PPH | 11.581 | 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 9 (5.3) | 29 (16.9) | |||

| No | 161 (94.7) | 143 (83.1) | |||

| Use of extra uterotonics | 0.057 | 0.811 | |||

| Yes | 28 (16.5) | 30 (17.4) | |||

| No | 142 (83.5) | 142 (82.6) | |||

| Use of blood transfusion | 7.716 | 0.006 | |||

| Yes | 5 (2.9) | 18 (10.5) | |||

| No | 165 (97.1) | 154 (89.5) | |||

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.26 ± 0.45 | 3.15 ± 0.47 | 0.012, 0.208 | 0.028 | |

| 1-minute Apgar score | 7.89 ± 1.70 | 8.24 ± 1.49 | −0.690, −0.010 | 0.044 | |

| 5-minute Apgar score | 9.38 ± 1.64 | 9.57 ± 1.44 | −0.5168, 0.138 | 0.256 | |

| NICU admission | 0.221 | 0.639 | |||

| Yes | 33 (19.4) | 30 (17.4) | |||

| No | 137 (81.6) | 142 (82.6) |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

CI, confidence interval; PPH, postpartum haemorrhage; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Table 8.

Comparison of maternal and perinatal outcomes between Groups 3 and 4.

| Outcomes | Group 3 (n = 171) | Group 4 (n = 173) | χ2 | 95% CI (lower, upper) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary PPH | 8.150 | 0.004 | |||

| Yes | 9 (5.3) | 25 (14.5) | |||

| No | 162 (94.7) | 148 (85.5) | |||

| Use of extra uterotonics | 1.211 | 0.271 | |||

| Yes | 18 (10.5) | 25 (14.5) | |||

| No | 153 (89.5) | 148 (85.5) | |||

| Use of blood transfusion | 3.300 | 0.069 | |||

| Yes | 6 (3.5) | 14 (8.1) | |||

| No | 165 (96.5) | 159 (91.9) | |||

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.40 ± 0.60 | 3.25 ± 0.49 | 0.034, 0.266 | 0.012 | |

| 1-minute Apgar score | 8.03 ± 1.88 | 8.00 ± 1.86 | −0.367, 0.427 | 0.882 | |

| 5-minute Apgar score | 9.25 ± 1.97 | 9.40 ± 1.62 | −0.532, 0.232 | 0.441 | |

| NICU admission | 0.213 | 0.644 | |||

| Yes | 35 (20.5) | 32 (18.5) | |||

| No | 136 (79.5) | 141 (81.5) |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

CI, confidence interval; PPH, postpartum haemorrhage; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Table 9.

Comparison of maternal side effects of interventions among Groups 1, 2, 3, and 4.

| Maternal side effects | Group 1 (n = 170) | Group 2 (n = 172) | Group 3 (n = 171) | Group 4 (n = 173) | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shivering | 11.882 | 0.22 | ||||

| Yes | 128 (75.3) | 133 (77.3) | 118 (69.0) | 148 (85.5) | ||

| No | 42 (24.7) | 39 (22.7) | 53 (31.0) | 25 (14.5) | ||

| Pyrexia | 0.311 | 0.96 | ||||

| Yes | 24 (14.1) | 24 (14.0) | 29 (17.0) | 29 (16.8) | ||

| No | 146 (85.9) | 148 (86.0) | 142 (83.0) | 144 (83.2) | ||

| Headache | 4.070 | 0.25 | ||||

| Yes | 5 (2.9) | 3 (1.7) | 12 (7.0) | 4 (2.3) | ||

| No | 165 (97.1) | 169 (88.3) | 159 (93.0) | 169 (97.7) | ||

| Nausea | 14.909 | <0.01 | ||||

| Yes | 24 (14.1) | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.2) | 4 (2.3) | ||

| No | 146 (85.9) | 169 (88.3) | 169 (98.8) | 169 (97.7) | ||

| Vomiting | 11.580 | 0.07 | ||||

| Yes | 2 (1.2) | 6 (3.5) | 24 (14.0) | 4 (2.3) | ||

| No | 168 (98.8) | 166 (86.5) | 147 (86.0) | 169 (97.7) |

Data are presented as n (%).

Table 10.

Comparison of maternal side effects of interventions between Groups 1 and 2.

| Maternal side effects | Group 1 (n = 171) | Group 2 (n = 173) | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shivering | 13.424 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 118 (69.0) | 148 (85.5) | ||

| No | 53 (31.0) | 25 (14.5) | ||

| Pyrexia | 0.002 | 0.961 | ||

| Yes | 29 (17.0) | 29 (16.8) | ||

| No | 142 (83.0) | 144 (83.2) | ||

| Headache | 4.293 | 0.038 | ||

| Yes | 12 (7.0) | 4 (2.3) | ||

| No | 159 (93.0) | 169 (97.7) | ||

| Nausea | 15.806 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 24 (14.0) | 4 (2.3) | ||

| No | 147 (86.0) | 169 (97.7) | ||

| Vomiting | 0.655 | 0.418 | ||

| Yes | 2 (1.2) | 4 (2.3) | ||

| No | 169 (98.8) | 169 (97.7) |

Data are presented as n (%).

Table 11.

Comparison of maternal side effects of interventions between Groups 3 and 4

| Maternal side effects | Group 3 (n = 170) | Group 4 (n = 172) | χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shivering | 0.195 | 0.659 | ||

| Yes | 128 (75.3) | 133 (77.3) | ||

| No | 42 (24.7) | 39 (22.7) | ||

| Pyrexia | 0.002 | 0.965 | ||

| Yes | 24 (14.1) | 24 (14.0) | ||

| No | 146 (85.9) | 148 (86.0) | ||

| Headache | 0.536 | 0.464 | ||

| Yes | 5 (2.9) | 3 (1.7) | ||

| No | 165 (97.1) | 169 (88.3) | ||

| Nausea | 2.000 | 0.157 | ||

| Yes | 2 (1.2) | 6 (3.5) | ||

| No | 168 (98.8) | 166 (86.5) | ||

| Vomiting | 18.002 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 24 (14.1) | 3 (1.7) | ||

| No | 146 (85.9) | 169 (88.3) |

Data are presented as n (%).

Discussion

This study showed that the mean postoperative PCV was significantly higher in patients who received preoperative sublingual misoprostol than in the other groups of patients. The mean change in the PCV was also lowest in patients who received preoperative sublingual misoprostol than in the other groups. The mean intraoperative blood loss was highest and lowest in patients who received postoperative rectal and preoperative sublingual misoprostol, respectively. The mean intraoperative blood loss was significantly higher in patients who received postoperative rectal than preoperative rectal misoprostol. The mean changes in the PCV and intraoperative blood loss as calculated by the formula were significantly lower in patients who received preoperative sublingual than postoperative sublingual misoprostol. The incidence of primary PPH, use of extra uterotonics, and Apgar score at 1 minute were significantly higher in patients who received postoperative rectal than preoperative rectal misoprostol. The incidence of primary PPH was higher in patients who received postoperative sublingual than preoperative sublingual misoprostol. The incidence of nausea was significantly higher in patients who received preoperative rectal misoprostol than in the other groups of patients. The incidences of headache and vomiting were significantly higher in patients who received preoperative rectal than postoperative rectal misoprostol. However, the incidence of shivering was higher in patients who received postoperative rectal than preoperative rectal misoprostol. The incidence of nausea was significantly higher in patients who received preoperative sublingual than postoperative sublingual misoprostol.

The use of preoperative sublingual misoprostol in this study was associated with better postoperative haematological indices when compared with postoperative sublingual misoprostol and both preoperative and postoperative rectal misoprostol. This finding underscores the need for preoperative sublingual misoprostol use in patients undergoing obstetric care. The lower intraoperative blood loss in patients who received preoperative sublingual than postoperative sublingual misoprostol in this study is similar to the finding by Youssef et al. 16 in Egypt. The significantly smaller change in the PCV in patients who received preoperative sublingual than postoperative sublingual misoprostol is also similar to their finding. 16 This could be attributed to the earlier onset of action of sublingual misoprostol when given preoperatively than postoperatively. 8

The lower intraoperative blood loss in patients who received preoperative rectal than postoperative rectal misoprostol in this study is also similar to the finding reported by Maged et al. 17 in Egypt. However, the lack of a significant difference in the mean postoperative PCV and change in PCV between patients who received preoperative and postoperative rectal misoprostol in this study is not consistent with the findings of Maged et al. 17 The finding of better postoperative haematological indices in patients who received sublingual than rectal misoprostol in our study is similar to previous reports in Nigeria and Egypt.12–15 This might be attributed to the earlier onset of action of sublingual than rectal misoprostol. 8

This study also showed a higher incidence of primary PPH and blood transfusion use in patients who received postoperative rectal than preoperative rectal misoprostol, indicating that preoperative rectal misoprostol use is more effective than postoperative rectal misoprostol use. The significantly lower 1-minute Apgar score in the neonates of mothers who received preoperative rectal than postoperative rectal misoprostol may have been due to the earlier onset of uterine contraction in the former than latter group. The similar 5-minute Apgar scores between mothers who received preoperative rectal and postoperative rectal misoprostol in this study can be attributed to the high-quality neonatal resuscitation services in the study centres. We also found a higher incidence of primary PPH in patients who received postoperative sublingual than preoperative sublingual misoprostol, consistent with the report by Maged et al. 17 in Egypt.

The significantly higher incidence of nausea in patients who received preoperative rectal misoprostol than postoperative rectal misoprostol and both preoperative and postoperative sublingual misoprostol underscores the need for prophylactic use of antinausea drugs during caesarean section among these participants. The higher incidences of shivering, headache, and nausea in patients who received preoperative rectal than postoperative rectal misoprostol may have been due to the earlier onset of action of preoperative than postoperative rectal misoprostol. Likewise, the higher incidence of vomiting in patients who received preoperative sublingual than postoperative sublingual misoprostol may have been due to the earlier onset of action in the former than latter group. The higher side effect profile of preoperative than postoperative misoprostol use underscores the need for prophylactic interventions against such side effects by anaesthetists.

Strengths of this study

This was a randomised controlled trial, and blinding of the investigators helped to minimise errors due to bias. Additionally, the intraoperative blood loss was determined by the average blood loss calculated using a formula and a gravimetric method.

Limitations of this study

The surgeries were performed by different surgeons with different skill levels, which might have contributed to the different levels of intraoperative blood loss volumes. Additionally, the intraoperative blood loss calculation by the gravimetric method might had been less accurate because of the sponges being soaked with both blood and amniotic fluid. Finally, intra- and inter-observer errors may have occurred among the investigators while checking the outcome measures.

Conclusion and recommendations

Preoperative sublingual misoprostol use was associated with the highest postoperative PCV and smallest changes in the PCV and intraoperative blood loss when compared with postoperative sublingual, preoperative rectal, and postoperative rectal misoprostol use among pregnant women undergoing caesarean section. Sublingual misoprostol use was associated with better haematological indices than rectal misoprostol use. Additionally, preoperative sublingual and rectal misoprostol use was associated with better haematological indices than postoperative sublingual and rectal misoprostol use. Preoperative sublingual and rectal misoprostol use was associated with better maternal outcomes than postoperative sublingual and rectal misoprostol use. However, preoperative sublingual and rectal misoprostol use caused worse maternal side effects than postoperative sublingual and rectal misoprostol use. Therefore, preoperative sublingual and rectal misoprostol use during caesarean section is recommended to help reduce intraoperative and postoperative blood loss. Further research is needed to strengthen or refute the existing evidence.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-imr-10.1177_03000605231213242 for Preoperative versus postoperative misoprostol use for prevention of blood loss during caesarean section in pregnant women at term: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial by Leonard Ogbonna Ajah, Monique Iheoma Ajah, Hyginus Uzo Ezegwui, Theophilus Ogochukwu Nwankwo, Chukwuemeka Anthony Iyoke and Wilson Ndukwe Nwigboji in Journal of International Medical Research

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-imr-10.1177_03000605231213242 for Preoperative versus postoperative misoprostol use for prevention of blood loss during caesarean section in pregnant women at term: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial by Leonard Ogbonna Ajah, Monique Iheoma Ajah, Hyginus Uzo Ezegwui, Theophilus Ogochukwu Nwankwo, Chukwuemeka Anthony Iyoke and Wilson Ndukwe Nwigboji in Journal of International Medical Research

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. Jeremiah Eze, Matthew Obajiobi, Camillus Egbe, and Chinedu Obi for their participation in the study as trained research assistants.

Author contributions: L.O. Ajah was involved in the study concept, design, planning, and conduct; data analysis; and manuscript writing.

M.I. Ajah was involved in the study design, planning, and conduct; data analysis; and manuscript writing.

H.U. Ezegwui was involved in the study design, planning, and conduct; data analysis; and manuscript writing.

T.O. Nwankwo was involved in the study conduct, data analysis, and manuscript writing.

C.A. Iyoke was involved in the study conduct, data analysis, and manuscript writing.

W.N. Nwigboji was involved in the study conduct, data analysis, and manuscript writing.

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Funding: This research was self-funded; it received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ORCID iD: Leonard Ogbonna Ajah https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4945-667X

Data availability statement

The data for this study are readily available on request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, et al. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health 2021; 6: e005671. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF. 2019. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018.Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernández-Castro F, López-Serna N, Treviño-Salinas EM, et al. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of buccal misoprostol to reduce the need for additional uterotonic drugs during cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016; 132: 184–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maged AM, Helal OM, Elsherbini MM, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of preoperative tranexamic acid among women undergoing elective cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015; 131: 265–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall NE, Fu R, Guise JM. Impact of multiple cesarean deliveries on maternal morbidity: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 205: 262.e1–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajwa SK, Bajwa SJ, Kaur H, et al. Management of third stage of labor with misoprostol: a comparison of three routes of administration. Perspect Clin Res 2012; 3: 102–108. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.100666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ragab A, Barakat R, Alsammani MA. A randomized clinical trial of preoperative versus postoperative misoprostol in elective cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2016; 132: 82–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang OS, Schweer H, Seyberth HW, et al. Pharmacokinetics of different routes of administration of misoprostol. Hum Reprod 2002; 17: 332–336. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meckstroth KR, Whitaker AK, Bertisch S, et al. Misoprostol administered by epithelial routes: drug absorption and uterine response. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 108: 582–590. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000230398.32794.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang OS, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Ho PC. Misoprostol: pharmacokinetic profiles, effects on the uterus and side-effects. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2007; 99: S160–S167. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris JL, Khatun S. Clinical guidelines-the challenges and opportunities: what we have learned from the case of misoprostol for postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019; 144: 122–127. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Omozuwa ES, Okonkwo CA. Randomized controlled trial of sublingual and rectal misoprostol administration on blood loss at elective caesarean section. Eur J Biol Med Sci Res 2018; 7: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosni NM, Abd El-Aal NK, Gawwad RE, et al. Comparison between preoperative sublingual and rectal misoprostol on blood loss in elective cesarean delivery. Menoufia Med J 2021; 34: 1189–1194. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sayed MA, Sayed MS, Ibrahim MM. Comparison between the effect of sublingual and rectal misoprostol on hemoglobin level change before and after caesarean section. Egypt J Med Res 2020; 1: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sweed MS, El-Saied MM, Abou-Gamrah AE, et al. Rectal vs. sublingual misoprostol before cesarean section: double-blind, three-arm, randomized clinical trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2018; 298: 1115–1122. doi: 10.1007/s00404-018-4894-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Youssef A, Khalifa M, Bahaa M, et al. Comparison between preoperative and postoperative sublingual misoprostol for prevention of postpartum hemorrhage during cesarean section: a randomized clinical trial. Open J Obstet Gynecol 2019; 9: 529–538. doi: 10.4236/ojog.2019.94052. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maged AM, Fawzi T, Shalaby MA, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the safety and efficacy of preoperative rectal misoprostol for prevention of intraoperative and postoperative blood loss at elective cesarean delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2019; 147: 102–107. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Federal Republic of Nigeria. 2006 Population and Housing Census. National Population Commission 2010; 4: 1–371. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhong B. How to calculate sample size in randomized controlled trial? J Thorac Dis 2009; 1: 51–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT Group. BMJ 2010; 340–332. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-imr-10.1177_03000605231213242 for Preoperative versus postoperative misoprostol use for prevention of blood loss during caesarean section in pregnant women at term: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial by Leonard Ogbonna Ajah, Monique Iheoma Ajah, Hyginus Uzo Ezegwui, Theophilus Ogochukwu Nwankwo, Chukwuemeka Anthony Iyoke and Wilson Ndukwe Nwigboji in Journal of International Medical Research

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-imr-10.1177_03000605231213242 for Preoperative versus postoperative misoprostol use for prevention of blood loss during caesarean section in pregnant women at term: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial by Leonard Ogbonna Ajah, Monique Iheoma Ajah, Hyginus Uzo Ezegwui, Theophilus Ogochukwu Nwankwo, Chukwuemeka Anthony Iyoke and Wilson Ndukwe Nwigboji in Journal of International Medical Research

Data Availability Statement

The data for this study are readily available on request from the corresponding author.