Abstract

Dilutions of raw seawater produced a bacterial isolate capable of extended growth in unamended seawater. Its 2.9-Mb genome size and 40-fg dry mass were similar to values for many naturally occurring aquatic organotrophs, but water and DNA comprised a large portion of this small chemoheterotroph, as compared to Escherichia coli. The isolate used only a few aromatic hydrocarbons and acetate, and glucose and amino acid incorporation were entirely absent, although many membrane and cytoplasmic proteins were inducible; it was named Cycloclasticus oligotrophus. A general rate equation that incorporates saturation phenomena into specific affinity theory is derived. It is used to relate the kinetic constants for substrate uptake by the isolate to its cellular proteins. The affinity constant KA for toluene was low at 1.3 μg/liter under optimal conditions, similar to those measured in seawater, and the low value was ascribed to an unknown slow step such as limitation by a cytoplasmic enzyme; KA increased with increasing specific affinities. Specific affinities, a°s, were protocol sensitive, but under optimal conditions were 47.4 liters/mg of cells/h, the highest reported in the literature and a value sufficient for growth in seawater at concentrations sometimes found. Few rRNA operons, few cytoplasmic proteins, a small genome size, and a small cell size, coupled with a high a°s and a low solids content and the ability to grow without intentionally added substrate, are consistent with the isolation of a marine bacterium with properties typical of the bulk of those present.

Bacteria are the dominant transthreptic (across-surface-feeding) group of chemoheterotrophic organisms in aquatic systems. They regulate the concentrations of dissolved biogenic organics at nanomolar concentrations in the oceans (7) and help support food webs (48). These diverse (3, 19, 39), mostly planktonic oligobacteria are infrequently studied because few regarded as typical in the environment have been successfully cultivated (54, 55). Their nutrient collection ability remains in question because the specific affinities reported for cultured bacteria are too small to support presumed rates of growth in pelagic systems (6). Extinction culture, i.e., dilution of marine populations with unamended sterile seawater to a few organisms, often produces pure cultures (13). The first culture obtained by this technique was isolate RM 1, later referred to as RB1 (57). It persisted through numerous subcultures in Resurrection Bay seawater without substrate addition, allowing further characterization, and a 5.7-kb chromosomal DNA fragment was sequenced (57).

In this communication, we show that specific affinities are sufficiently large to support growth at ambient hydrocarbon concentrations in seawater, but values vary with experimental protocol. To sharpen the kinetic analysis, specific affinity theory, where nutrient uptake is specified by a rate constant that derives from the amount of permease or initial enzyme, is extended to accommodate saturation phenomena and constants related to organism composition. The isolate is phylogenetically characterized and its nutritional and physiological aspects are described by using the theory along with new flow cytometric methods (42) to help understand the ability of aquatic bacteria to persist in a dilute, predator-inhabited environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture and analyses.

Extinction culture RB1 was obtained as a 108 dilution of Resurrection Bay seawater (13) and maintained in glycerol at −50°C. Dilution was done with unamended seawater from Resurrection Bay, Alaska, prepared by filtration through fired Gelman A/E 47-mm-diameter filters, autoclaving, refiltering through other fired Gelman filters, and aseptically siphoning the sterile filtrate into incubation chambers. Culture purity was ascertained from flow cytometry patterns and by microscope observation of colonies on agar plates following incubation for 10 days at 20°C. Population density, dry weight, DNA content, and biomass were determined by flow cytometry (10). The standard curve for biomass was taken from light scatter theory (28) after corrections for system geometry, axial ratio, and formaldehyde sorption, and calibration from the radioactivity of 14[C]acetate-grown cells together with CHN analyses (42). Cell volume was determined by electrical impedance (model ZBI Coulter counter), and buoyant density was determined by centrifugation in Percoll (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). DNA was determined from the DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) fluorescence of single cells (10) by using Escherichia coli containing integral genome copies with a size of 4.7 Mbp (43) or 5.17 fg and a GC content of 50 mol% (29) as a standard. The AT bias of DAPI (59) was corrected in accordance with the GC content of the isolates, 52.7 mol% for Marinobacter sp. strain T2 (20) and 41.6 mol% for isolate RB1 (20). Light scatter and fluorescence axes of the cytograms were converted to dry mass and DNA per cell by use of formulations of the standard curves. Phospholipid fatty acids were determined by Microbial Insights, Inc., Knoxville, Tenn.

Substrate usage.

Autoclaved synthetic seawater (13) was amended with individual substrates or mixtures of substrate at 100 mg/liter. The mixture contained 30% carbohydrates (glucose, fructose, fucose, galactose, rhamnose, and arabinose), 20% organic acids (acetate, lactate, glycolate, and succinate), 10% alcohols (mannitol, glycerol, and ethanol), 20% organic acids (acetate, lactate, glycolate, and succinate), 20% casein hydrolysate, and 20% peptone. Volatiles were added as vapors. Flasks were inoculated with 104 to 106 of acetate-grown cells/ml at 25°C and observed for change in population density, cell size, and DNA per cell by flow cytometry. For amino acids and glucose uptake, acetate (100 mg/liter)-grown cells were washed three times by centrifugation, filtered (pore size, 1 μm) to remove aggregates, and incubated with radiolabeled substrate at 25°C. Transformation rates of toluene were measured with purified [U-14C]hydrocarbon (NEN Life Science Products) by toluene-grown washed cells as previously described (41). Cell production by continuous culture (31) was limited by injection of toluene to 20 mg/liter into the feed carboy headspace and operated at a dilution rate of 0.1/h. Cells were collected from the reactor by syringe, aerated for 20 min to remove residual toluene, and used directly for uptake measurements. Kinetic constants were obtained by using programs written to give a best fit to v versus S plots (see Table 1), logarithmic transformations, and affinity plots in combination.

TABLE 1.

Nomenclature

| Term | Definition | Dimensions |

|---|---|---|

| a°S | Specific affinity (for substrate S in this case); base or unsaturated value; aKAS value at S = KA | liters mg of cells−1 h−1 |

| a°max | Specific affinity of a perfectly absorbing sphere | liters mg of cells−1 h−1 |

| aS | Specific affinity for substrate S as reduced by saturation | liters mg of cells−1 h−1 |

| A | Acetate | g liter−1 |

| B | Toluene | g liter−1 |

| c | Constant | liters cell (g of cells site h)−1 |

| D | Molecular diffusion constant | cm2 s−1 |

| k | Rate constant | liter particle−1t−1 day−1 |

| kcat | Catalytic constant | mol of substrate transformed mol of protein−1 s−1 |

| KA | Affinity constant: concentration of S at a°S/2 | g liter−1 |

| Km | Michaelis-Menten constant: concentration of S at Vmax/2 | g liter−1 |

| M | Molecular mass | Da |

| μ | Growth rate | h−1 |

| N | Number of molecules of a particular permease | molecules cell−1 |

| ρ | Organism density | g of cell material cm−3 |

| R | Resistivity | dimensionless |

| ζ | Absorption coefficient | dimensionless |

| rX | Radius of spherical cell | cm |

| rs | Effective radius of a permease site | cm |

| S | Concentration of substrate (general) | g liter−1 |

| τ | Residence time | cell site s−1 molecule−1 |

| v | Rate of substrate uptake by a cell (vx) or population of cells | g of substrate liter−1 h−1; g of substrate cell−1 h−1 |

| Vmax | Maximaliterrate of substrate accumulated | g of substrate accumulated g of cells−1 h−1 |

| X | Biomass | g of cells (wet weight) liter−1 |

| Y | Cell yield | g of cells produced (g of substrate consumed)−1 |

DNA purification and analysis.

Genomic DNA was purified from isolates after detergent lysis (22). The small-subunit rRNA-encoding genes (rDNA) were amplified from positions 27 to 1492 (E. coli numbering) as described previously (25). PCR-amplified products were either cloned into the pCRII vector (Invitrogen, Inc., Carlsbad, Calif.) or purified on Wizard columns (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Clones and PCR products were sequenced by using the ABI Catalyst 800 for Taq cycle sequencing and the ABI 373 A sequencer for analysis of products. A collection of 10 primers was used for rDNA sequencing, resulting in an average redundancy of 2.5 per nucleotide position. Sequences were aligned manually on the basis of conserved regions of primary sequence and secondary structure. A phylogenetic tree was inferred from 1,272 positions by using fastDNAml (38).

The number of 16S rDNA genes was estimated by restricting purified genomic DNA with three restriction enzymes (PvuII, PstI, and SacI) and separating the fragments on a 1.0% agarose gel. Southern analyses of the restriction digests were performed by using a digoxigenin-dUTP-labeled probe complementary to a 5′ region (positions 8 to 519) of the E. coli B strain 16S rDNA.

Homologs to tfdA genes were amplified by using conserved primers and stringent reaction conditions that provided specificity with divergent bacterial isolates (25).

Protein separations.

Acetate- or toluene-grown cells were disrupted with lysozyme in a French pressure cell (16) and separated into soluble cytoplasmic and membrane fractions by centrifugation at 155,000 × g. The membrane fraction was taken up in phosphate-ethanol-glycerol buffer and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) as reported previously (56) and modified as described in the Millipore Investigator manual, and the proteins were quantified by densitometry (Alpha Innotech IS-1000; Innotech, San Leandro, Calif.) of silver-stained gels.

RESULTS

Kinetic theory.

The collision frequency of substrate molecules with a cell can be described by a per-particle rate constant, k (51). For a substrate of molecular mass M, concentration S, and diffusion constant D, and a cell of radius rx (Table 1), k = 4πrxD/1,000 (1). For an organism of density 1.04 g cm3, the equation k = 10 DM/rx2 describes substrate collection by a perfectly collecting sphere and is the maximal value for specific affinity (4) a°max. At subsaturating concentrations, the observable rate of uptake, v, for a cell population of biomass X is smaller than that described by a°max in proportion to the surface area unavailable to colliding molecules for transport, and entrance is resisted by the cell envelope more than it would be if the cell were comprised of water alone. This resistance can be specified in terms of an absorbability constant, ζ, so that the uptake rate is:

|

1 |

Converting absorbability back to resistivity, R, where ζ = 1 − R, and with R = (a°max − a°S)/a°max, the rate equation may be written in terms of the base or saturation-independent value of the specific affinity a°S:

|

2 |

Assuming that uptake requires interaction with a permease or initial enzyme, the specific affinity depends on the number or aggregate effective area of the active sites of these proteins and is reduced by saturation phenomena to some value, aS. At small substrate concentrations where v is unaffected by saturation, aS approaches a°S. The population of molecules in the organism devoted to substrate uptake may be approximated by comparing this rate constant for the total active-site area of the protein in question with the corresponding rate constant for the whole cell. In the case of N substrate-collecting molecules with effective site radius rs:

|

3 |

As substrate concentrations increase, resistivity is increased by saturation and, where the resistance is hyperbolic, the rate equation is completely specified by a°S and Vmax (9). Rearranging the Michaelis-Menten equation by substituting a°S, the initial slope of the v versus S curve, for Vmax/Km:

|

4 |

and a v/S versus v or affinity plot gives the two kinetic constants a°S and Vmax as intercepts. Where Vmax is experimentally indeterminant (40) or the kinetics are nonhyperbolic (34), the v/S intercept remains the base value of the specific affinity, and the saturation-dependent affinity, aS is v/S, i.e., the value whose product is rate at any substrate concentration, S. Specific affinity is obtained as units of liters per gram of cells per hour by taking N as the number of permease molecules, kcat as their catalytic constant expressed as a residence time τ = 1/kcat, and aS as v/S from equation 2. Surface area is converted to wet mass by use of cell density, and choosing c = 5DMrs2/2rX4 liters cell (g of cells site h)−1 gives the following:

|

5 |

The numerator describes the unsaturated or maximal observable value of the specific affinity as a°S = Nc. Inspection shows that the saturation-dependent specific affinity, aS, approaches a°S at low concentrations and zero at high concentrations, the affinity constant KA is S at a°S/2, Km remains S at Vmax/2, and the general rate equation becomes:

|

6 |

Characteristics.

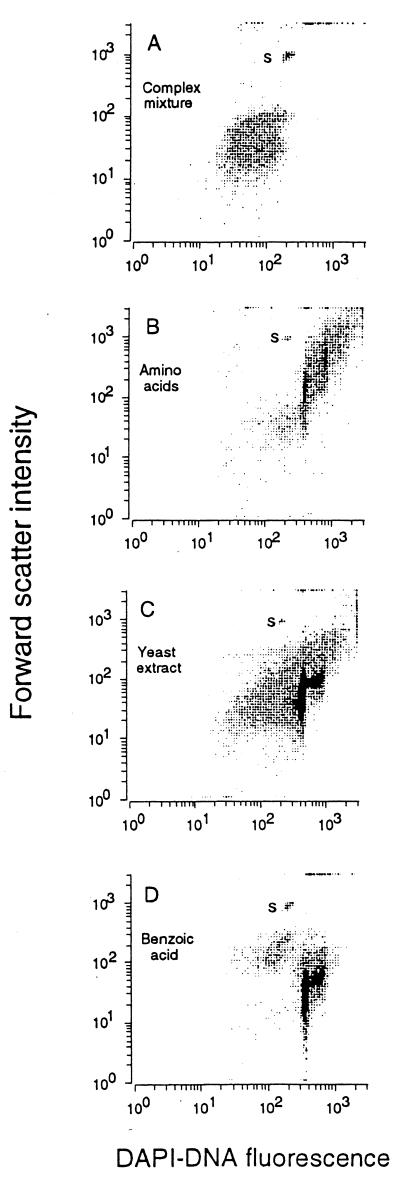

RB1 populations diluted to a single cell in unamended sterile seawater attained 105 organisms/ml. These small populations were sufficient for phylogenetic analysis that suggested a previously undescribed genus and for characterization by flow cytometry. Addition of sugars, amino acids, organic and fatty (lipoic) acids, alcohols, polyols, glucan, and lignin derivatives such as anisoin (4,4′-dimethoxybenzoin) facilitated little further increase to the base population of 105/ml. A complex mixture of common substrates transformed the inoculum into cells with low DAPI-DNA fluorescence (Fig. 1). Natural media such as yeast extract gave slightly larger cell populations, but cytograms plotting DNA versus biomass remained poorly resolved, suggesting that the additions to media were also unhelpful in providing larger populations. The low-fluorescence or “dim” cells produced often appear in old cultures (42) and in freshwater and seawater populations as well (11). Since the dry biomass of these dim cells is often the same as that for growing cells (Fig. 1A is an exception), much of the DNA may be degraded (26) but retained. Flow cytometry has been used previously to detect apoptosis in eukaryotic cells (36), changes which include DNA fragmentation (17), and data show that it can be used to indicate the DNA status of bacterial cells and for development of suitable growth conditions as well.

FIG. 1.

Isolate characteristics after inoculation into various media (as indicated on the figure).

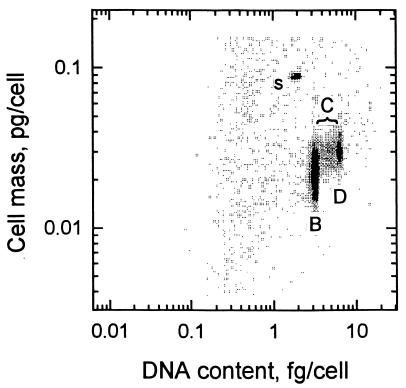

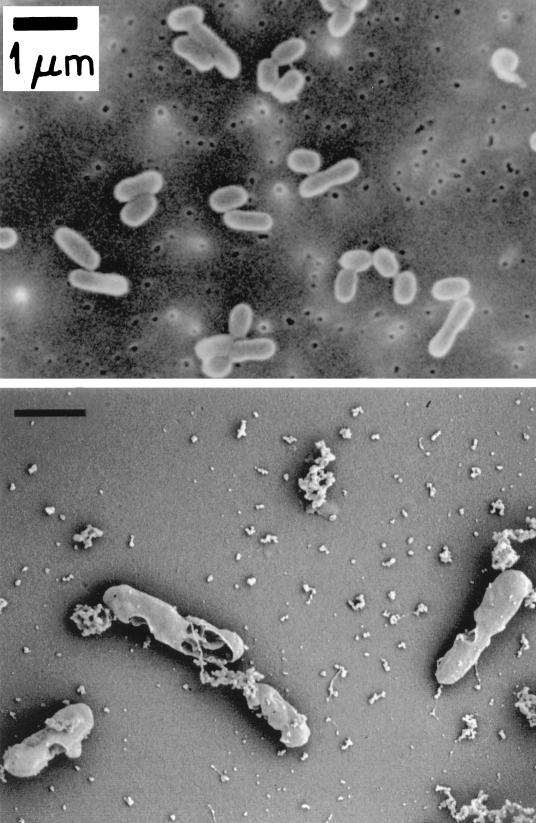

With acetate present in high (100-mg/liter) concentrations, smooth translucent, colorless microscopic colonies appeared on agar plates in 10 days and turbid cultures were produced in liquid culture. Liquid cultures resulted in cytograms (Fig. 2) showing dry weights of from 15 to 45 fg (dry weight)/cell comprised of mostly B-phase cells with some D-phase (two-chromosome) cells (15) and a few replicating C-phase cells. Cell shape was that of a short rod defined by a thin cell envelope (Fig. 3), and flagella appeared to be present. Mean values for the cells of cultures in various stages of growth, as indicated by the range in single-chromosome content, are compared for three species (Table 2). Both the dry weight and the genome size of RB1 were comparatively small, but the DNA content was large, as shown in Table 2.

FIG. 2.

Cytogram showing cells before (B), during (C), and following (D) replication. s, standard spheres.

FIG. 3.

Scanning (top) and scanning cryogenic (bottom) electron micrographs of the isolate.

TABLE 2.

Physiological characteristics of C. oligotrophus and conventional isolates

| Organism | % ln chromo-some cells (no. of cultures) | Mean dry mass ± SD (fg/cell) | Solids (% wet wt) | Density (g/cm3)a | Genome size (Mbp) | DNA (% dry wt) | No. of ribosomal operons | No. of membrane proteins/no. of cytoplasmic proteinsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycloclasticus oligotrophus (RB1) | 30–80 (10) | 40.1 ± 8 | 16 | 1.07 ± 0.01 | 2.9 | 14 | 1 | 210/170 |

| Marinobacter arcticus (Pseudomonas sp. strain T2) | 65–85 (3) | 52 ± 4 | 20 | 1.075 ± 0.00 | 4.1 | 11 | 2 | 300/290 |

| Escherichia coli | 65–85 (10) | 352 ± 147 | 29 | 1.10 ± 0.005 | 4.7 | 2.2 | 7 | 860b |

a Values are means ± standard deviations.

b Total number of resolved proteins (56).

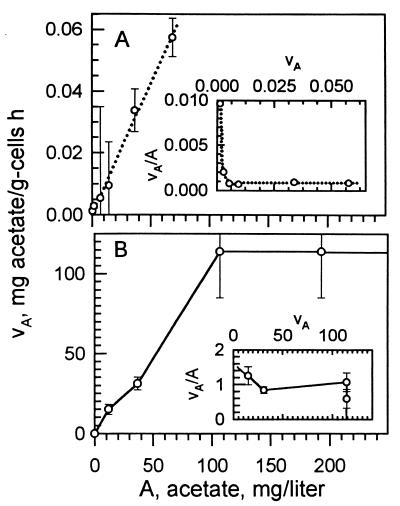

Amphiphile kinetics.

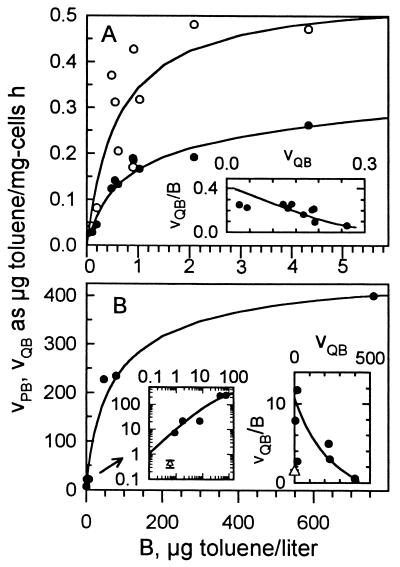

The maximal growth rate, μmax, on acetate was 0.19/h in batch culture with a cell yield of 1.24 mg (wet weight) of cells produced per mg of acetate consumed. Washed cells incubated with [14C]acetate gave linear rates of incorporation for an hour, but the specific affinity (Fig. 4) was only 9 × 10−2 liters/g of cells/h. Uptake rates were also linear with substrate concentration to give a concave-side up affinity plot (Fig. 4A, inset).

FIG. 4.

Acetate (substrate A) uptake kinetics. (A) Rate vA of [14C]acetate uptake by washed cells at 1.2 mg of cells/ml over 2 min. The slope gives a specific affinity of a°A = 0.09 liters/mg of cells/h; other constants from the affinity plot (inset) are indeterminant. (B) Uptake rates of acetate vA (= μY) from the growth rates μ at 12 to 195 mg of acetate/liter over 30 h and cell yield Y (=1.24 g of cells [wet weight]/g of acetate used). The kinetic constants are a°A = 1.5 liters/g of cells/h and Vmax = 125 mg of acetate/g of cells/h from the affinity plot intercepts (inset).

In batch culture, the acetate concentration remained essentially unchanged during 50 h of substrate-limited growth because of the low affinities, and the kinetic constants could be evaluated. The resulting rates of growth, together with cell yield, transformed into a linear dependency of uptake rate on concentration (Fig. 4B). Two populations appeared at moderate rates of growth (Fig. 2). The ratio of cells with two, as compared to one, chromosomes increased with growth rate μ according to μ = kD/B, where k is 1.74/day, as the acetate concentration increased from 12 to 107 mg/liter. This demonstrated the range of acetate concentrations that was effective in growth rate control. The associated specific affinity of 1.5 liters (g of cells h)−1 was small but 16 times the value directly observed from [14C]acetate uptake. At higher concentrations, the increase in uptake rate was truncated by μmax.

Growth substrates.

When washed acetate-grown cells were incubated with glucose or an amino acid mixture, incorporation was negligible (Table 3). The highest specific affinity attained was 0.003 liters/mg of cells/h, indicating a resistivity, R, to incorporation of only 1 × 10−9 to 5 × 10−9, or very nearly unity as compared with a perfect resistance of exactly unity. Growth strategies of oligobacteria often include the concomitant use of multiple substrates to increase the usable concentration of substrate (5). However, data show an absence of incorporation of trace amounts of radioactivity from hydrolysis products of carbohydrates and amino acids by active cultures.

TABLE 3.

Resistance to absorption of glucose and amino acids

| Substrate | Concn (μg liter−1) | Radio-activity (dpm ml−1) | Biomass (μg ml−1) | Incuba-tion time (min) | Filtered radioactivity (dpm/2 ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 10.1 | 46,000 | 15.6 | 0.5 | 46 |

| 10.1 | 46,000 | 15.6 | 900 | 29 | |

| 10.1 | 46,000 | 125 | 900 | 44 | |

| Amino acids | 0.6 | 27,390 | 5.2 | 0.5 | 45 |

| 0.6 | 27,390 | 5.2 | 3,800 | 93 | |

| 12.7 | 119,350 | 5.2 | 3,800 | 133 |

Dilution to about 1 cell of a culture that was maintained on acetate for 3 years into 20 ml of unsupplemented seawater resulted in cultures with usual characteristics (Table 4), showing that the ability to grow in very dilute media is a constitutive property of RB1. The DNA content of the 21-day unamended seawater culture is consistent with a growth rate of 0.9/day, neglecting a small C-phase population. A number of hydrocarbons were found to support populations in the milligram-per-liter range from an acetate-grown inoculum including naphthalene, phenanthrene, biphenyl, and toluene. Various monoterpenes, dodecane, and methane did not support growth.

TABLE 4.

Sustained ability of isolate RB1 to grow on unamended seawater

| Incubation time (days) | Population (cells/ml) | Dry mass (fg/cell) | Vol (μm3/cell)a | Vol of ln cells (μm3) | Avg DNA content (fg/cell) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0b | 0.05 | 37.8 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 4.1 |

| 18 | 30,000 | 41.1 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 4.4 |

| 0c | 3,000 | 41.1 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 4.4 |

| 21 | 180,000 | 48.9 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 4.8 |

a Calculated from light scatter intensity, a dry weight/wet weight ratio of 0.20, and a density of 1.04 g/cm3.

b The inoculum was subcultured 28 times on 100 mg of acetate liter−1, diluted to 50 cells in 5 μl, and added to 50 ml of unamended seawater.

c The inoculum was a 1:10 dilution of the 18-day culture.

Toluene uptake.

14[C]toluene supplied to washed cells appeared as CO2 (Fig. 5), cell material, and nonvolatile metabolic products (41) distributed among several compounds that remain unidentified in dilute-substrate experiments (λmax for the mixture was 401.5 nm). Use of small populations was required to avoid premature depletion during the several minutes needed to establish a time course for substrate uptake by these very active cells. Time course curves for 14CO2 evolution were linear and without significant intercept values at time zero. The accumulation rate of 14C-labeled nonvolatile metabolic products was more erratic and may have been affected by resorption; 70% of the product radioactivity accumulated over the first few minutes was lost in high-biomass experiments. Radioactivities collected as cells on membrane filters (data not shown) were inconsistent, giving an error of approximately 30% due to the large membrane filter/biomass ratio used, but values were near those for 14CO2. From these and other data, we estimate a yield of cells-carbon dioxide-products of 1:1.00:1.95, similar to that for Marinobacter arcticus (41). Specific affinities calculated from uptake rates and cell yield increased substantially when uptake was observed over longer incubation times, as facilitated by reducing biomass to nanogram-per-milliliter quantities (Table 5). A large value was obtained from continuously grown cells as well. Competitive displacement of label from residual toluene was estimated at 90% after sparging for 2 min from the increase in specific affinity and decrease in radioactivity; 20 min was allowed for complete removal. Passage through 1.2-μm-pore-size filters had little effect on observed specific affinities and precluded overestimation of values due to the presence of small clumps undetected by flow cytometry, although these were presumed to be absent from the low value of the above-scale particle count.

FIG. 5.

Toluene (substrate B) uptake kinetics. (A) Uptake over 4 min with 2,590 μg of cells/liter; (B) uptake over 90 min with 2.4 μg of cells/liter. [14C]toluene uptake was from the rate of liberation of oxidation products (VPB) (○) and CO2 (VQB) (•) and was calculated as toluene mass; toluene uptake rates from CO2 recovered from continuously grown cells (▵) are also shown (31). Rates were calculated from the appearance of cell material, CO2, and metabolic products.

TABLE 5.

Effect of experimental protocol on the kinetic constants for toluene uptake

| Biomass wet wt (ng/ml) | Incuba-tion time (min) | a°QB (liters/mg of cells/h)a | KA (μg/liter)b | Km (μg/liter) | Vmax (μg of B/mg of cells/h)c | a°B (liters/ mg of cells/hc) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,590 | 4 | 0.55 | 1.3 | 0.9 | >2 | 2.2 |

| 600d | 4.5 | 2.7 | 10.6 | |||

| 2.4 | 90 | 12b | 34 | 60 | >1,215 | 47.4 |

a Partial affinity calculated from that portion of toluene (substrate B) used and collected as product, P, or carbon dioxide, Q.

b Concentration at half-maximal specific affinity.

c Calculated from carbon dioxide production and yield.

d Uptake using toluene-limited cells grown in continuous culture.

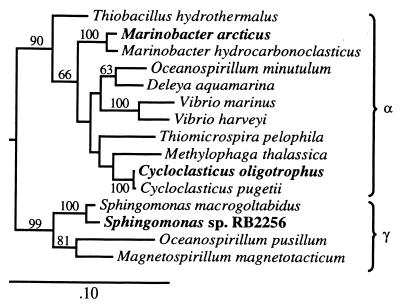

Taxonomy.

The 16S rDNA of the isolate is phylogenetically related to the recently described Cycloclasticus pugetii (18) and used to designate the organism as Cycloclasticus oligotrophus (57). Differentiation is based on small size and essentially absolute inability to utilize polar substrates such as amino acids (Fig. 1 and Table 3). The enrichment culture isolate used for physiological comparison (Table 2) was obtained from ballast water of the tanker Mobile Arctic in Port Valdez, Alaska, and also grows on toluene (a°B = 0.63 liters/mg of cells/h and KA = 66 μg/liter [41]) but uses amino acids (a°S = 4.1 liters/mg of cells/h, KA = 136 μg/liter for a mixture [unpublished data]). It is phylogenetically similar to Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus (20) but grows on glucose and is referred to as Marinobacter arcticus. Phylogenetic locations relative to some other aquatic bacteria are shown in Fig. 6.

FIG. 6.

Phylogenetic tree of Proteobacteria inferred by maximum-likelihood analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences. The oligobacteria discussed are indicated by boldface type. The marker bar represents evolutionary distance.

Structural genes.

Five open reading frames sequenced from chromosomal DNA (57) included homologs with the large and small subunits of biphenyl dioxygenase as well as an unidentified membrane protein. Only a single copy of the rRNA operon (44) was present in C. oligotrophus. Both C. oligotrophus and M. arcticus contained genes that were amplified when tfdA-specific primers were used in the PCR. The tfdA gene product has been associated with the metabolism of chlorinated hydrocarbons (25). The PCR products from C. oligotrophus were approximately 400 and 450 bp, while the product from M. arcticus was about 600 bp, compared to only 360 bp for the fragment from Alicaligenes atrophies (25).

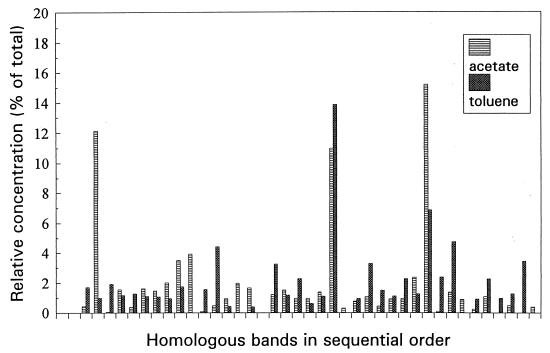

Cytoarchitecture.

Indigenous marine bacteria are comparatively small, a morphological characteristic that has impeded observation. They also are thought to be quite dense, with carbon content increasing to 0.38 g/cm with decreasing size (33); however, the required cell volume data are difficult to measure by microscope due to their small size. Flow cytometry and radioactivity of 14[C]acetate-grown C. oligotrophus (42) gave the expected low dry weight for a typical marine bacterium (Table 2), but the total solids content was only 16% as calculated from cell volume according to Coulter Counter and buoyant density. While the CHN ratio was normal at 47:5.6:9.2% by CHN analysis, the carbon content was also low at 7% of wet cell mass according to the radioactivity measurements. Dry weight was corroborated by comparatively low equilibrium density measurements. Also, the refractive index by minimal optical density in serum albumin was 1.025, to give a low dry weight (27) of 19%. This compares with a refractive index of 1.039 for E. coli and a dry weight content of 27 to 30%, and the organism was more dilute than expected for marine bacteria (35). One result of the low dry weight was a DNA content six times that of E. coli on a dry mass basis despite a genome that is little more than half the size.

Two-dimensional electrophoretic patterns suggested fewer proteins in C. oligotrophus than in M. arcticus and E. coli (Table 2), consistent with organism simplicity. Among the 210 cytoplasmic and 170 membrane peptides resolved, about 50 in each appeared as unique toluene-inducible spots. Among the major membrane peptides, the concentration of at least four more doubled in the presence of acetate, and induction by toluene was equally strong for 11 others (Fig. 7). Two cytoplasmic toluene-inducible proteins, according to their N-terminal amino acid sequences, were related to catechol 2,3-dioxygenase and dihydroxynaphthalene dioxygenase (unpublished data). Data show that although few growth substrates have been identified, this small low-DNA organism retains the ability to adjust its protein composition to environmental conditions.

FIG. 7.

Densitometry scans of one-dimensional SDS-PAGE gels from the membrane protein fractions of acetate- and toluene-grown cells.

The unsaturated fatty acid content of acetate-grown C. oligotrophus increased with growth on toluene at the expense of stearic and oleic acids (Table 6) and the major trans fatty acid, 16:w7t, present at 2.4%, was nearly eliminated with growth on toluene.

TABLE 6.

Whole-cell phospholipid fatty acid composition of RB1

| Common name of fatty acid | No. of carbons | Unsaturation | Fatty acid (%)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate grown | Toluene grown | |||

| Palmitic | 16 | 0 | 39 | 38 |

| Hexadecanoic | 16 | cis-7 | 27 | 60 |

| 16 | trans-7 | 2.4 | 0.1 | |

| Palmitoleic | 16 | cis-9 | 3.4 | |

| Stearic | 18 | 0 | 10.7 | 1.2 |

| Oleic | 18 | cis-9 | 6.4 | |

DISCUSSION

Composition.

The dry cell mass of C. oligotrophus was 15 to 20 fg/cell when growth rates were restricted, maximal at 80 fg/cell, and similar to values for populations from the Gulf of Alaska, where means ranged from 30 to 37 fg/cell between those collected at the sea surface and those collected at a depth of 1400 m (unpublished data). Mass was at the 15th percentile of bacteria from the Gulf profile; i.e., 85% of the particles having >1.5 fg of DNA and a 7-fg dry cell mass were smaller (unpublished data). Yet the organism was far smaller than most aquatic bacteria that have been isolated and perpetuated in pure culture. The DNA content of 3.2 fg (2.9 Mb)/genome was the same as the mean value of 3.1 to 3.2 fg for total DNA in the depth series. The large DNA content retained following cultivation in unamended seawater (Table 4, 21-day culture) is, in the absence of a long lag phase, indicative of a growth rate that is higher than justified by initial and final cell populations. Chromosome runout, or production of some two-chromosome-containing cells following exhaustion of the natural substrate (2), occurs in the isolate (47) and provides an explanation for this apparent discrepancy between growth rate and cell cycle theory (23). DNA comprised much of the cytoplasm of smaller bacteria in seawater, so these organisms may approach a minimum dry weight for their genome size. Induction (41) and regulation (46) of proteins for hydrocarbon metabolism are known and, although the genome size of the isolate is comparatively small (Table 2), the ability to regulate was encoded within this small genome. Only about 5% of the in situ forms from the depth series contained less than 1.5 fg of DNA, which suggests a lower limit for pelagic marine bacteria. Small size and low dry weight maximize the surface-to-volume ratio for effective nutrient accumulation, minimize endogenous costs, and reduce value to predators. However, the small genome size could restrict metabolic flexibility. Organisms with very low amounts of DNA have not yet appeared in our extinction cultures. The only other known extinction culture isolate, Sphingomonas sp. strain RB2256, also has a high specific affinity for substrate and but one rRNA operon copy (45). Because DNA is a major fraction of the dry weight of C. oligotrophus, minimizing it represents a way of allowing small size. Similarity in size and DNA content to in situ organisms and the retained ability to grow on unamended seawater suggest that the isolate may be rather typical of marine bacteria.

Nutrition.

The low specific affinity for acetate indicated that uptake of this substrate was incidental and of little use to the organism in the environment, and the large affinity constant with specific affinity abruptly truncated by μmax suggested that acetate was not actively transported. The increase in trans fatty acids during growth on this low-affinity substrate is consistent with increased stress (58) and that less fluid membranes are not used for defense against 30-mg/liter concentrations of toluene used in culture media. Acetate is, however, advantageous for use in laboratory media since large concentrations of the substrate can be added without substrate inhibition. Potential difficulties from substrate-accelerated death due to unintentionally added polar substrates in inhibitory concentrations during isolation were avoided by an essentially perfect resistance to their incorporation, as determined by glucose and amino acid uptake data, possibly contributing to our success in isolation.

Organism sensitivity to environmental change is suggested by the large increase in specific affinity and Vmax for both acetate and toluene that is facilitated by continuous undisturbed growth in batch culture, long incubation times at extremely small populations, or by continuous culture. Such sensitivity is consistent with the even larger increase in the specific affinity observed for phosphate when care was taken to use populations directly from continuous culture with minimal manipulation (40). These phosphate data also showed an extreme variability in Vmax due to manipulation, as reported here for acetate and toluene. Affinities of transthreptic organisms may often be underestimated because the flux computed from growth rates is difficult to attain in uptake experiments and presumed growth rates in the oceans are higher than justified by most measurements of specific affinity (6). Comparisons of specific affinities with those from other systems and with expected flux requirements for growth may help alleviate or explain these discrepancies.

Kinetics.

The maximal specific affinity for toluene use by C. oligotrophus is uncertain, but the observed value of 47.4 liters/mg of cells/h is the largest known for various organism-substrate combinations (6). It compares with a molecular collision frequency sufficient to attain a specific affinity of about 6,000 liters/mg of cells/h, meaning that the resistance, R, to unimpeded flow into the organism is 0.992, giving an absorbability, ζ, of 0.8% of the theoretical maximum, where all molecular collisions with the cell surface are successful. The specific affinity for continuously grown cells was only slightly lower, and the standard error of the measurement was small (Fig. 6). The reduction could have been due to the sensitivity of the organism to unavoidable population disturbance during the aeration step between cell harvest and uptake measurement or to unexpected oxygen limitation since the process is electron acceptor sensitive (32).

Rates of growth with in situ toluene concentrations measured at 1 μg/liter (12) can be calculated from the data of Table 5 and equation 4. To do this, we substitute a°B for Nc in equation 5 to obtain nutrient collection on an organism, rather than enzyme molecule, basis; set KAcτ at unity so that the denominator is 2 since the affinity constant KA is the substrate concentration at which the specific affinity is half its maximal value, a°B; and with KA = B = 1.3 μg/liter, solve for cτ to obtain (2 − 1)/1.3 × 10−6 = 0.769 × 106 liters2/g of cells/g of substrate/h. At B = 1 × 10−6 g/liter, the specific affinity at 1 μg/liter is 47.4 × 103/[1 + (1 × 10−6)(0.769 × 106)] = 26.8 × 103 liters/g of cells/h. With aB determined, equation 6 may be written in terms of the specific rate of growth, μB, from the toluene (substrate B) component of the medium:

|

7 |

With a cell yield Y of 0.46 mg (wet weight) of cells/mg of toluene used from radioactivity incorporation, the specific growth rate is (26.4 × 103)(1 × 10−6)(0.46) = 0.012/h or 0.29/day. Specific affinities for substrates should be additive when rates involve different rate-limiting steps so that concomitant utilization of only two other substrates at equivalent affinities and concentrations should allow the organisms to exceed a doubling time of 1 day. The value of reporting this kinetic constant is suggested by literature data from which specific affinities may be calculated that give insufficient values for observed rates of culture growth at all but very large concentrations of substrates (6). Inclusion would help clarify the abilities of populations to grow at small substrate concentrations because the scale is absolute rather than normalized to Vmax, because most aquatic microbial populations are nutrient limited, and because a°s is sensitive to some difficult-to-avoid systematic errors.

Environmental applications.

Use of exogenous toluene in seawater samples is too rapid (8) for likely support of the required enzyme systems by anthropogenic sources, but hydrocarbons might be formed as electron sinks during anaerobic metabolism of complex organics from plant material deposited in underlying sediments. The presence of a PCR product amplified by tfdA-specific primers, the first enzyme in the pathway for the degradation of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, further suggests a role for biogenic hydrocarbons in the nutrition of C. oligotrophus. Large quantities of bromoform occur in coastal seawater (7), and chlorinated hydrocarbons can provide a vehicle for chlorine removal in plants (21). The isolate also contains glutathione-S-transferase (57), which may assist in dechlorination (24) prior to exergonic metabolism of halogenated hydrocarbons, so there appears to be potential supplies of both hydrocarbons and chlorinated hydrocarbons to support hydrocarbon-oxidizing bacteria in the ocean.

The observed specific affinity for toluene is 100 to 1,000 times the value for the bacterioplankton community toward amino acids, both in freshwater and marine systems (unpublished), and values range over a factor of 300 for various cultures (Table 7). Assuming minimal systematic effects on the determination of kinetic constants, some organisms are 300 times better at collecting toluene from low concentrations than others. Ambient toluene may be partitioned from low external concentrations to higher concentrations within the membrane lipid (50) and, because of the direct relationship between permeability and partition coefficient (30), diffuse unimpeded into the cytoplasm. The specificity of dioxygenases is broad (53), and the quantity available for toluene oxidation can be estimated at 2,500 molecules per cell (6), so permeases may not be required. At Vmax, the residence time of toluene on dioxygenase molecules could be as long as 250 ms, and if the collection area of the active site has a radius of 10 Å to give c = 9.2 liters cell (g of cells site h)−1, the specific affinity is 84 liters/mg of cells/h, only about twice that observed. Solving equation 4 for S gives an affinity constant, KA, of 4.6 μg/liter that is near the measured value of 1.3 μg/liter. The small affinity constant for this oligotroph, compared to most measured values for bacteria (5), might be attributed to small amounts of enzyme in metabolic pathways, amounts that are sufficient for growth when nutrient concentrations are low and rates are low but small enough to increase residence time in metabolic pathways. This may be seen from equation 5, where the saturation-dependent specific affinity decreases with increasing τ. At environmentally excessive concentrations, overloaded pathways from the large amounts of initial enzyme produced to collect substrate cause an increase in the effective τ, i.e., residence time, based on the rate of substrate passage through the whole pathway including steps catalyzed by small numbers of enzyme molecules. Small specific affinities may be associated with large saturation constants and maximal velocities for rapid metabolism at high concentrations as indicated by large Vmax values (Table 7). The large specific affinity is thought to be related to the amount of initial enzyme, and the small affinity constant is taken as flux limitation by the amount of downstream enzyme consistent with the concept of flux-limiting enzymes (37). That Km exceeds KA is expressed by the concave-side-up affinity plots. Simulations show that these kinetics are consistent with both stimulation of slow steps such as macromolecule synthesis through positive feedback to give an effective increase in τ and the concentration-dependent shift in the control point of a metabolic pathway mentioned above. The low affinity constants for toluene uptake are consistent with in situ Km values (Table 7), and the decreased affinity with increased saturation constants is consistent with specific affinity theory but not with the application of Michaelis-Menten concepts for enzymes to whole cells.

TABLE 7.

Comparison of kinetic constants for toluene use in various systems

| Culture | Specific affinity (liters/mg of cells/h) | Km (μg/liter) | Vmax (g of toluene/g of cells/h) | Refer-ence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycloclasticus oligotrophusa | 47.4 | 60 | 1.21 | This study |

| Pseudomonas acinetobacterb | 3.34 | 1,168 | 1.16 | 52 |

| Total seawater populationc | 0.390 | 1.9 | 8 | |

| Marinobacter arcticusa | 0.320 | 66 | 0.01 | 41 |

| Pseudomonas putidaa | 0.316 | 63 | 0.02 | 41 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescensd | 0.312 | 1,800 | 5.62 | 49 |

| Pseudomonas fragid | 0.140 | 1,960 | 0.44 | 14 |

a Data from CO2 production and cell yield by washed cells.

b Data from analysis of the decay rate of pentane extracts; specific affinities estimated from Vmax/Km for these and subsequent data.

c Data from CO2 production and cell yield in fresh sample.

d Data from headspace analysis of the rate of toluene decay.

The growth substrates that sustain this organism in unamended seawater media remain unknown. This is also true for pelagic bacteria, given observed specific affinities for common substrates, if one assumes a homogeneous distribution of dissolved organics and that most of the approximately 106 cells/ml are both metabolically active and reproducing. Although care was taken to exclude hydrocarbon vapors from the incubation chambers, complete elimination may not have taken place. Alternatively, untested substrate combinations may have been used by this induction-capable isolate. The kinetic constants shown here are the first that are consistent with growth in the pelagic marine environment at measured concentrations of organic substrate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Luis Pinto for electrophoretic analyses and Rosemary Ruff, formerly of this institution, and Ya Chen, of the University of Wisconsin Integrated Microscopy Resource, for electron microscopy.

Support was provided by the Ocean Sciences and Metabolic and Cellular Biochemistry sections of the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berg H C, Purcell E M. Physics of chemoreception. Biophys J. 1977;20:193–219. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(77)85544-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binder B J, Chisholm S W. Cell cycle regulation in marine Synechococcus. sp. strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:708–717. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.708-717.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Britshgi T B, Giovannoni S J. Phylogenetic analysis of natural marine bacterioplankton population by rRNA cloning and sequencing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1701–1713. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.6.1707-1713.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Button D K. Differences between the kinetics of nutrient uptake by microorganisms, growth and enzyme kinetics. Trends Biochem Sci. 1983;8:121–124. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Button D K. The physical base of marine bacterial ecology. Microb Ecol. 1994;28:273–285. doi: 10.1007/BF00166817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Button D K. Nutrient uptake by microorganisms according to kinetic parameters from theory as related to cytoarchitecture. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:636–645. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.636-645.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Button D K, Jüttner F. Terpenes in Alaskan waters: concentrations, sources, and the microbial kinetics used in their prediction. Mar Chem. 1989;26:57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Button D K, Robertson B R. Dissolved hydrocarbon metabolism: the concentration-dependent kinetics of toluene oxidation in some North American estuaries. Limnol Oceanogr. 1986;31:101–111. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Button D K, Robertson B R. Kinetics of bacterial processes in natural aquatic systems based on biomass as determined by high-resolution flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1989;10:558–563. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990100511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Button D K, Robertson B R. Use of high-resolution flow cytometry to determine the activity and distribution of aquatic bacteria. In: Kemp P F, Sherr B F, Sherr E B, Cole J J, editors. Handbook of methods in aquatic microbial ecology. Ann Arbor, Mich: Lewis Publishers; 1993. pp. 163–173. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Button D K, Robertson B R, Jüttner F. Microflora of a subalpine lake: bacterial populations, size, and DNA distributions, and their dependence on phosphate. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1996;21:87–101. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Button D K, Robertson B R, McIntosh D, Jüttner F. Interactions between marine bacteria and dissolved-phase and beached hydrocarbons after the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:243–251. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.1.243-251.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Button D K, Schut F, Quang P, Martin R M, Robertson B. Viability and isolation of typical marine oligobacteria by dilution culture: theory, procedures, and initial results. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:881–891. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.3.881-891.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang M K, Voice T C, Criddle C S. Kinetics of competitive inhibition and cometabolism in the biodegradation of benzene, toluene, and p-xylene by two Pseudomonas isolates. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1993;41:1057–1065. doi: 10.1002/bit.260411108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper S. Bacterial growth and division: biochemistry and regulation of prokaryotic and eukaryotic division cycles. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cull M, McHenry C S. Preparation of extracts from prokaryotes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;182:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82014-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darzynkiewicz Z, Bruno S, Del Bino G, Gorczyca W, Hotz M A, Lassota P, Traganos F. Features of apoptotic cells measured by flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1992;13:795–808. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990130802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dyksterhouse S E, Gray J P, Herwig R P, Lara J C, Staley J T. Cycloclasticus pugetii gen., sp. nov., an aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacterium from marine sediments. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:116–123. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-1-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuhrman J A, McCallum K, Davis A A. Phylogenetic diversity of subsurface marine microbial communities from the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1294–1302. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1294-1302.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gauthier M J, LaFay B, Christen R, Fernandez L, Acquaviva M, Bonin P, Bertrand J-C. Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus gen. nov., sp. nov., a new, extremely halotolerant, hydrocarbon-degrading marine bacterium. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:568–576. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-4-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geigert J, Neidleman S L, De Witt S K, Dalietos D J. Halonium ion-induced biosynthesis of chlorinated marine metabolites. Phytochemistry. 1984;23:287–290. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giovannoni S J, DeLong E F, Schmidt T M, Pace N R. Tangential flow filtration and preliminary phylogenetic analysis of marine picoplankton. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2572–2575. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.8.2572-2575.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray J W, Dolbeare F, Pallavicini M G. Quantitative cell-cycle analysis. In: Melamed M R, Lindmo T, Mendelsohn M L, editors. Flow cytometry and sorting. 2nd. ed. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss, Inc.; 1990. pp. 445–467. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hofer B, Backhaus S, Timmis K N. The biphenyl/polychlorinated biphenyl-degradation locus (ph) of Pseudomonas sp. LB400 encodes four additional metabolic enzymes. Gene. 1994;144:9–16. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hogan D A, Buckley C H, Nakatsu C H, Schmidt T M, Hausinger R P. Distribution of the tfdA gene in soil bacteria that do not generate 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) Microb Ecol. 1997;34:90–96. doi: 10.1007/s002489900038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kapuscinski J, Yanagi K. Selective staining by 4′,6-diamidine-2-phenylindole of nanogram quantities of DNA in the presence of RNA on gels. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;6:3535–3542. doi: 10.1093/nar/6.11.3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koch A L. Some calculations on the turbidity of mitochondria and bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1961;51:429–441. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(61)90599-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koch A L, Robertson B R, Button D K. Deduction of the cell volume and mass from forward scatter intensity of bacteria analyzed by flow cytometry. J Microbiol Methods. 1996;27:49–61. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krawiec S, Riley M. Organization of the bacterial chromosome. Microbiol Rev. 1990;54:502–539. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.4.502-539.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakshminarayanaiah N. Equations of membrane biophysics. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Law A T, Button D K. Modulation of the affinity of a marine pseudomonad for toluene and benzene by hydrocarbon exposure. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;51:469–476. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.3.469-476.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leahy J G, Olsen R H. Kinetics of toluene degradation by toluene-oxidizing bacteria as a function of oxygen concentration, and the effect of nitrate. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;23:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee S, Fuhrman J A. Relationships between biovolume and biomass of naturally derived marine bacterioplankton. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1298–1303. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.6.1298-1303.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewis D L, Hodson R E, Hwang H M. Kinetics of mixed microbial assemblages enhance removal of highly dilute organic substrates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2054–2058. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.8.2054-2057.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loferer-Krössbacher M, Klima J, Psenner R. Determination of bacterial cell dry mass by transmission electron microscopy and densitometric image analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:688–694. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.688-694.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mentz F, Baudet S, Blanc C, Issaly F, Merle-Beral H. Simple, fast method of detection of apoptosis in lymphoid cells. Cytometry. 1998;32:95–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newsholme E A, Crabtree B. Flux-generating and regulatory steps in metabolic control. Trends Biochem Sci. 1981;6:53–56. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olsen G J, Matsuda H, Hagstrom R, Overbeek R. FastDNAml: a tool for construction of phylogenetic trees of DNA sequences using maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci. 1994;10:41–48. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pace N. A molecular view of microbial diversity and the biosphere. Science. 1997;276:734–740. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robertson B R, Button D K. Phosphate-limited continuous culture of Rhodotorula rubra: kinetics of transport, leakage, and growth. J Bacteriol. 1979;138:884–895. doi: 10.1128/jb.138.3.884-895.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robertson B R, Button D K. Toluene induction and uptake kinetics and their inclusion in the specific-affinity relationship for describing rates of hydrocarbon metabolism. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2193–2205. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.9.2193-2205.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robertson B R, Button D K, Koch A L. Determination of biomasses of small bacteria at low concentrations in a mixture of species with forward light scatter measurements by flow cytometry. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3900–3909. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3900-3909.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rudd K E, Miller W, Ostell J, Benson D A. Alignment of Escherichia coli K12 DNA sequences to a genomic restriction map. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:313–321. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.2.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt T. Multiplicity of ribosomal RNA operons in prokaryotic genomes. In: DeBruijn F J, Lupiski J R, Weinstock G, editors. Bacterial genomes: physical structure and analysis. New York, N.Y: Chapman and Hall; 1997. pp. 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schut F, Gottschal J C, Prins R A. Isolation and characterization of the marine ultramicrobacterium Sphingomonas sp. strain RB2256. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1997;20:363–369. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Selifonova O V, Eaton R W. Use of an ipb-lux fusion to study regulation of the isopropylbenzene catabolism operon of Pseudomonas putida RE204 and to detect hydrophobic pollutants in the environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:778–783. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.778-783.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shapiro H M. Practical flow cytometry. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: Alan R. Liss; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sherr E B, Sherr B F. High rates of consumption of bacteria by pelagic ciliates. Nature. 1987;325:710–711. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shreve G S, Vogel T M. Comparison of substrate utilization and growth kinetics between immobilized and suspended Pseudomonas cells. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1992;41:370–379. doi: 10.1002/bit.260410312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sikkema J. Interactions of cyclic hydrocarbons with biological membranes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8022–8028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smoluchowski M V. Versuch einer mathematischen theorie der koagulationskinetik kolloider, losungen. Z Phys Chem. 1916;92:129–168. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sommer H M, Holst H, Spliid H. Nonlinear parameter estimation in microbiological degradation systems and statistic test for common estimation. Environ Int. 1995;21:551–556. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spain J C, Zylstra G J, Blake C K, Gibson D T. Monohydroxylation of phenol and 2,5-dichlorophenol by toluene dioxygenase in Pseudomonas putida F1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2648–2652. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.10.2648-2652.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suzuki M T, Rappé M S, Haimberger Z W, Winfield H, Adair N, Ströbel J, Giovannoni S J. Bacterial diversity among small-subunit rRNA gene clones and cellular isolates from the same seawater sample. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:983–989. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.983-989.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tuomi P, Torsvik T, Heldal M, Bratbak G. Bacterial population dynamics in a meromictic lake. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2181–2188. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2181-2188.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.VanBogelen R A, Olson E R, Wanner B L, Neidhardt F C. Global analysis of proteins synthesized during phosphorus restriction in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4344–4366. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4344-4366.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Y, Lau P C K, Button D K. A marine oligobacterium harboring genes known to be part of aromatic hydrocarbon degradation pathways of soil pseudomonads. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2169–2173. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.2169-2173.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weber F J, Isken S, de Bont J A M. Cis/trans isomerization of fatty acids as a defense mechanism of Pseudomonas putida strains to toxic concentrations of toluene. Microbiology. 1994;140:2013–2017. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-8-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilson W D, Tanious F A, Barton H J, Jones R L, Fox K, Wydra R L, Strekowski L. DNA sequence dependent binding modes of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) Biochemistry. 1990;29:8452–8461. doi: 10.1021/bi00488a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]