Abstract

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a devastating monogenic neurodegenerative disease characterized by early, selective pathology in the basal ganglia despite the ubiquitous expression of mutant huntingtin. The molecular mechanisms underlying this region-specific neuronal degeneration and how these relate to the development of early cognitive phenotypes are poorly understood. Here we show that there is selective loss of synaptic connections between the cortex and striatum in postmortem tissue from patients with HD that is associated with the increased activation and localization of complement proteins, innate immune molecules, to these synaptic elements. We also found that levels of these secreted innate immune molecules are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of premanifest HD patients and correlate with established measures of disease burden.

In preclinical genetic models of HD, we show that complement proteins mediate the selective elimination of corticostriatal synapses at an early stage in disease pathogenesis, marking them for removal by microglia, the brain’s resident macrophage population. This process requires mutant huntingtin to be expressed in both cortical and striatal neurons. Inhibition of this complement-dependent elimination mechanism through administration of a therapeutically relevant C1q function-blocking antibody or genetic ablation of a complement receptor on microglia prevented synapse loss, increased excitatory input to the striatum and rescued the early development of visual discrimination learning and cognitive flexibility deficits in these models. Together, our findings implicate microglia and the complement cascade in the selective, early degeneration of corticostriatal synapses and the development of cognitive deficits in presymptomatic HD; they also provide new preclinical data to support complement as a therapeutic target for early intervention.

Subject terms: Microglia, Huntington's disease

Microglia mediate the early and selective degeneration of corticostriatal synapses and the development of cognitive deficits in presymptomatic Huntington’s disease via the complement cascade.

Main

Huntington’s disease (HD) is the most common autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disease. It is characterized by progressive motor, cognitive and psychiatric symptoms, with onset of the manifest phase typically occuring around 45 years of age1. Currently, there are no therapies that modify disease onset or progression.

HD is caused by a CAG repeat expansion mutation in the HTT (huntingtin) gene encoding an expanded polyglutamine (PolyQ) tract in the mutant huntingtin protein2,3. Based on this genetic finding, multiple transgenic animal models have been generated to interrogate the underlying biology of the disease4,5; however, the molecular mechanisms that drive early and selective degeneration of basal ganglia circuits and how these relate to cognitive phenotypes remain poorly understood6–23. The corticostriatal pathway, which connects intratelencephalic and pyramidal tract neurons in the cortex with medium spiny neurons (MSNs) and cholinergic interneurons (ChIs) in the striatum, is affected at very early stages of disease progression19,24. Electrophysiological recordings in mouse models and structural and functional imaging of patients with HD in the premanifest stage of the disease reveal altered white matter structure and functional connectivity in this pathway, which correlates with a more rapid cognitive decline18,25–29. Reductions in synaptic marker levels suggest that corticostriatal synapses are lost, but it is unknown whether this loss occurs before onset of motor and cognitive deficits or why corticostriatal synapses are selectively vulnerable22.

Studies in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia have demonstrated a link between synaptic loss and components of the classical complement cascade, a group of secreted ‘eat me’ signals that mediate recognition and engulfment of synaptic elements by microglia during development and in disease contexts30–36. Although this mechanism of synaptic elimination has never been explored in HD, transcriptional profiling, brain imaging and analysis of patient-derived serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) have indicated an altered neuro-immune state in premanifest HD patients37–44. In mouse models, microglia have also been found to display changes in morphology, deficits in motility and an altered transcriptional profile during the symptomatic phase of the disease45–53. Separately, transcriptomic studies have identified increased expression of complement proteins and their regulators in the basal ganglion of postmortem tissue from patients with HD54–57, suggesting that complement proteins and microglia are dysregulated. However, neither complement nor microglia has been studied at early stages of the disease, and it is unknown whether they contribute to synapse loss or the development of early cognitive deficits in HD.

By integrating findings from postmortem HD brain samples and two preclinical HD mouse models, we provide evidence that microglia and complement coordinate to selectively target corticostriatal synapses for early elimination in the dorsal striatum—a process initiated only when mutant HTT (mHTT) is expressed in both cortical and striatal neurons. Inhibition of synaptic elimination through administration of a therapeutic C1q function-blocking antibody (ANX-M1, Annexon Biosciences) or genetic ablation of microglial complement receptor 3 (CR3/ITGAM) reduces loss of corticostriatal synapses and improves visual discrimination learning and cognitive flexibility impairments at early stages of disease progression in HD models. We further show that aspects of this pathological synapse elimination mechanism may be operating in premanifest HD patients, as complement protein levels in the CSF of patients with HD correlate with an established predictor of both pathological severity and disease onset.

Results

Selective loss of corticostriatal synapses in patients with HD is associated with complement activation and changes in microglia

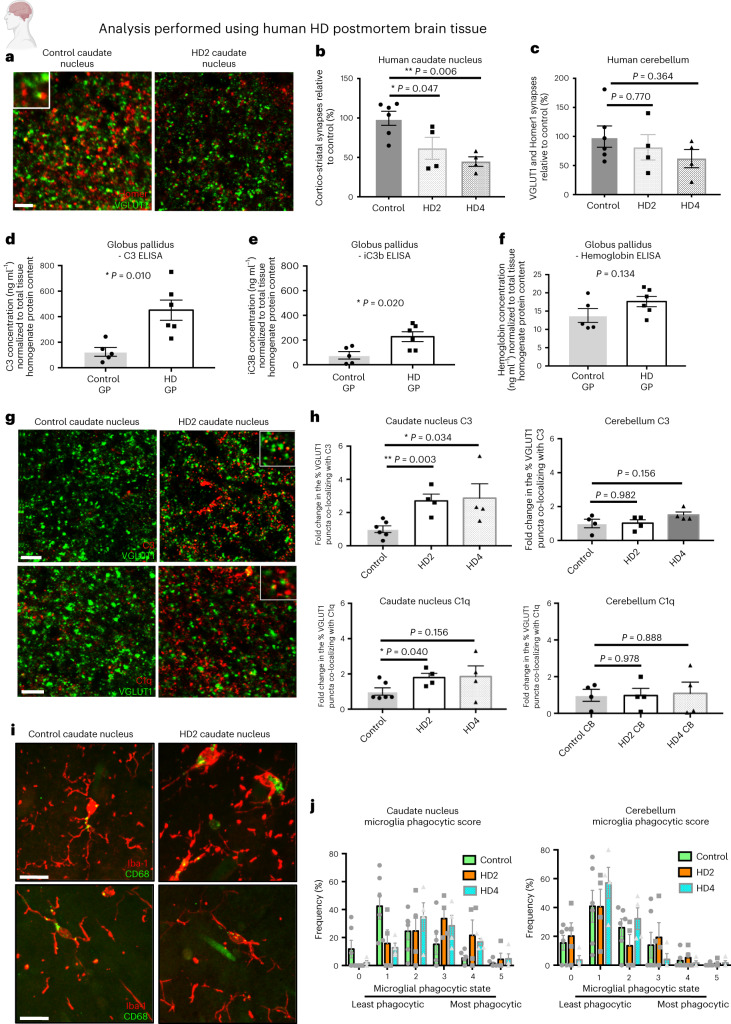

To test whether there is selective loss of corticostriatal synapses in patients with HD, we assessed glutamatergic excitatory synapses in postmortem tissue from the caudate nucleus (part of the striatum) and cerebellum of control individuals (no documented evidence of neurodegenerative disease) and patients with HD with different Vonsattel grades of striatal HD neuropathology58–61. Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of corticostriatal synapses, as denoted by co-localization of excitatory postsynaptic marker Homer1 and presynaptic corticostriatal marker VGLUT1, revealed a progressive and significant loss in the caudate of the HD tissue relative to that seen in tissue from control individuals (Fig. 1a,b). Conversely, we observed no difference in VGLUT1-positive glutamatergic synapses in the cerebellum, which is less affected in HD (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1a–c).

Fig. 1. Loss of corticostriatal synapses, increased activation and association of complement proteins with synaptic elements and adoption of a more phagocytic microglial state are evident in postmortem brain tissue from patients with HD.

a, Representative confocal images showing staining for corticostriatal specific presynaptic marker VGLUT1 and postsynaptic density protein Homer1 in the postmortem caudate nucleus of a control individual and a Vonsattel grade 2 patient with HD (Supplementary Table 2). Scale bar, 5 μm. b, Quantification of corticostriatal synapses (co-localized VGLUT1 and Homer1 puncta) in the caudate nucleus of control, Vonsattel grade 2 and Vonsattel grade 4 HD tissue, n = 6 control, n = 4 HD with Vonsattel 2 tissue grade and 4 HD with Vonsattel 4 tissue grade. One-way ANOVA P = 0.0058; Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, control versus HD2 P = 0.0474; control versus HD4 P = 0.0061; HD2 versus HD4 P = 0.537. c, The same analysis carried out in the molecular layer of the folia of the cerebellum (an area thought to be less impacted by disease) showed no change, n = 6 control individuals, 4 HD Vonsattel grade 2 and 4 HD Vonsattel grade 4. One-way ANOVA, P = 0.393; Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, control versus HD2 P = 0.770; control versus HD4 P = 0.365; HD2 versus HD4 P = 0.791. d, ELISA measurements of complement component C3 in extracts from the globus pallidus (GP) of postmortem tissue from manifest HD patients and control individuals (Supplementary Table 2) after normalization for total tissue homogenate protein content, n = 5 control GP and 6 HD GP. ANCOVA controlling for the effect of age F2,10 = 8.74, P = 0.010. e, ELISA measurements of complement component iC3b in the same extracts as d. ANCOVA controlling for the effect of age F2,10 = 6.71, P = 0.020. f, ELISA hemoglobin measurements in the same extracts as d. Unpaired two-tailed t-test P = 0.134. g, Representative confocal images showing staining for VGLUT1 together with C3 or C1q in the postmortem caudate nucleus of a control individual and a patient with HD who has been assessed to be Vonsattel grade 2. Scale bar, 5 μm. Insets show examples of co-localization of both complement proteins with presynaptic marker VGLUT1. h, Quantification of the percentage of VGLUT1+ glutamatergic synapses associating with C3 and C1q puncta in the caudate nucleus and cerebellum of postmortem tissue from patients with HD assessed to be either Vonsattel grade 2 or Vonsattel grade 4 relative to that seen in tissue from control individuals. For C3 in the caudate nucleus samples, n = 6 control individuals, n = 4 HD individuals with Vonsattel tissue grade 2 and n = 4 HD individuals with Vonsattel grade 4. One-way ANOVA, P = 0.029. Unpaired two-tailed t-test control versus HD2 P = 0.003; control versus HD4 P = 0.034. For C1Q in the caudate nucleus samples, n = 6 control individuals, n = 4 HD individuals with Vonsattel tissue grade 2 and n = 4 HD individuals with Vonsattel tissue grade 4. One-way ANOVA, P = 0.181. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, control versus HD2 P = 0.040, control versus HD4 P = 0.156. For C3 and C1Q in the cerebellum samples, n = 4 control individuals, n = 4 HD individuals with Vonsattel tissue grade 2 and n = 4 HD individuals with Vonsattel tissue grade 4. For C3, one-way ANOVA, P = 0.215. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, control versus HD2 P = 0.982; control versus HD4 P = 0.156. For C1q, one-way ANOVA, P = 0.981. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, control versus HD2 P = 0.978; control versus HD4 P = 0.888. i, Representative confocal images showing staining for Iba-1 and CD68 in the caudate nucleus and cerebellum of postmortem tissue from a control individual and a patient with HD (Vonsattel grade 2). Scale bar, 20 μm. j, Quantification of microglia phagocytic state based on changes in morphology and CD68 levels. For caudate nucleus samples, n = 6 control individuals, n = 4 HD individuals with Vonsattel tissue grade 2 and n = 4 HD individuals with Vonsattel tissue grade 4. Multiple unpaired two-tailed t-tests, control versus HD2; score 0 P = 0.253, score 1 P = 0.01, score 2 P = 0.984, score 3 P = 0.077, score 4 iP = 0.116 and score 5 P = 0.776. Control versus HD4; score 0 P = 0.255, score 1 P = 0.039, score 2 P = 0.382, score 3 P = 0.256, score 4 P = 0.006 and score 5 P = 0.309. For cerebellum samples, n = 6 control individuals, n = 4 HD individuals with Vonsattel tissue grade 2 and n = 4 HD individuals with Vonsattel tissue grade 4. Multiple unpaired two-tailed t-tests, control versus HD2; score 0 P = 0.635, score 1 P = 0.988, score 2 P = 0.243, score 3 P = 0.706, score 4 P = 0.610 and score 5 P = 0.477. Control versus HD4; score 0 P = 0.120, score 1 P = 0.348, score 2 P = 0.538, score 3 P = 0.415, score 4 P = 0.609 and score 5 P = 0.418. All error bars represent s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

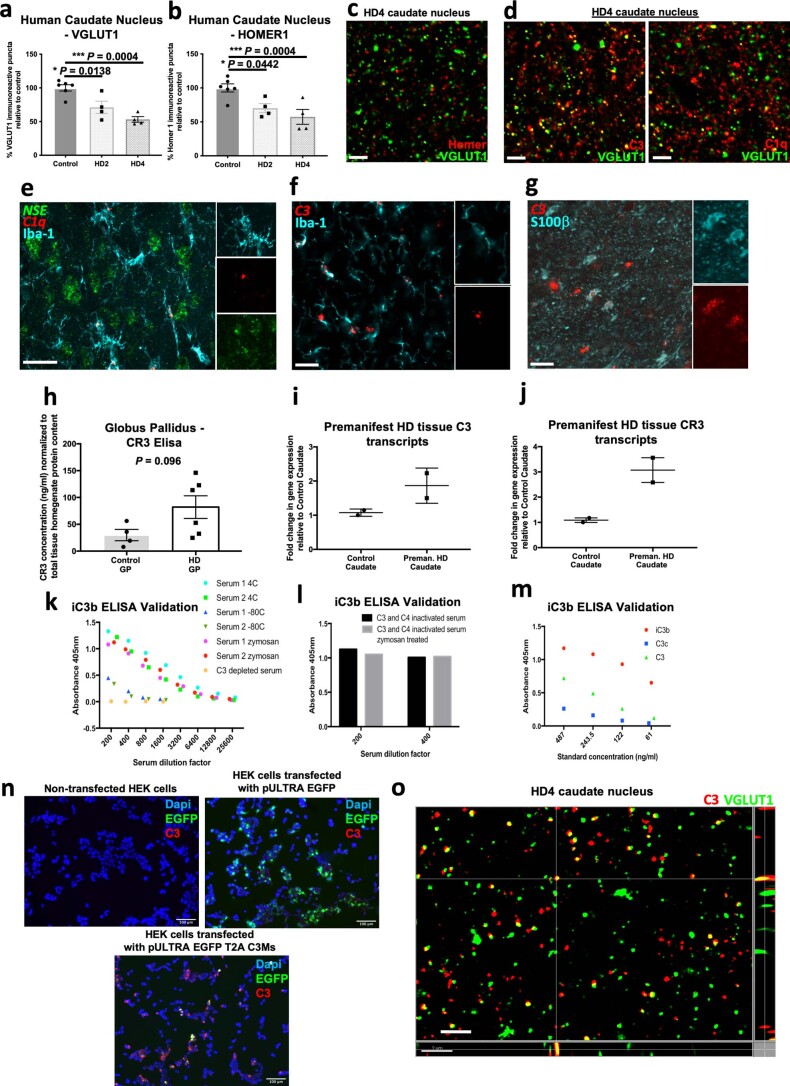

Extended Data Fig. 1. Loss of specific synaptic populations, activation and association of complement proteins with synaptic elements and adoption of a more phagocytic microglial state are evident in postmortem brain tissue from HD patients.

(a) Bar chart showing quantification of VGLUT1 immunoreactive puncta in the caudate nucleus of control, Vonsattel grade 2 HD and Vonsattel grade 4 HD tissue, n = 6 control, n = 4 HD with Vonsattel 2 tissue grade and 4 HD with Vonsattel 4 tissue grade. One way anova p = 0.0005; Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, control vs HD2 p = 0.0138; control vs HD4 p = 0.0004; HD2 vs HD4 p = 0.172. (b) Bar chart showing quantification of HOMER1 immunoreactive puncta in the caudate nucleus of control, Vonsattel grade 2 HD and Vonsattel grade 4 HD tissue, n = 6 control, n = 4 HD with Vonsattel 2 tissue grade and 4 HD with Vonsattel 4 tissue grade. One way anova p = 0.0054; Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, control vs HD2 p = 0.0442; control vs HD4 p = 0.0058; HD2 vs HD4 p = 0.541. (c) Representative confocal image showing staining for corticostriatal synaptic markers in the caudate nucleus of an HD patient, who has been assessed to be Vonsattel grade 4. Scale bar = 5 μm. This experiment was repeated 3 times. (d) Left panel is a representative confocal image showing staining for C1Q and VGLUT1 in the caudate nucleus of an HD patient, who has been assessed to be Vonsattel grade 4. Scale bar = 5 μm. Right panel is a representative confocal image showing staining for C3 and VGLUT1 in the caudate nucleus of an HD patient, who has been assessed to be Vonsattel grade 4. Scale bar = 5 μm. This experiment was repeated 3 times. (e) Representative confocal image of in situ staining for C1Q and NSE alongside IHC for microglial marker IBA1 in the caudate nucleus of postmortem tissue from an HD patient (Vonsattel grade 2). Scale bar = 20 μm. (f) Representative confocal image of in situ staining for C3 alongside IHC for microglial marker IBA1 in the caudate nucleus of postmortem tissue from an HD patient (Vonsattel grade 2). Scale bar = 20 μm. This experiment was repeated 3 times. (g) Representative confocal image of an in situ staining for C3 alongside IHC for astrocytic marker S100β in the caudate nucleus of postmortem tissue from an HD patient (Vonsattel grade 2). Scale bar = 20 μm. This experiment was repeated 3 times. (h) Bar chart showing ELISA measurements of the concentration of complement receptor CR3 in proteins extracted from the globus pallidus (GP) of postmortem tissue from manifest HD patients and control (no documented evidence of neurodegenerative disease; see Methods and supplemental table 2) individuals after normalization for total tissue homogenate protein content, n = 4 control GP and 6 HD GP (there was not enough protein available from one of the control sample that had previously been employed in the C3, iC3b and hemoglobin ELISA’s (the results of which are depicted in Fig. 5a,b and c) and as such it was not tested here). Unpaired two-tailed t-test p = 0.096 (i) Dot plot showing the fold change in mRNA levels of complement component C3 in samples from the caudate nucleus of two premanifest HD patients relative to those seen in two clinically normal (see Methods and Supplemental table 2) individuals. (j) Dot plot showing the fold change in mRNA levels of complement receptor CR3 in samples from the caudate nucleus of two premanifest HD patients relative to those seen in two clinically normal (see Methods and Supplemental table 2) individuals. (k) Superimposed scatter blot showing the relative absorbance values of different serum samples employed in the iC3b ELISA. Note that in two independent serum samples, in which the complement pathway has been activated either by incubating the serum at 4 °C for 7 days or treating with 10 mg/ml of zymosan for 30 min at 37 °C, the absorbance values for the highest concentration of serum tested are approximately double that of the same samples left untreated and maintained at -80 °C. Thus demonstrating that this assay reflects complement cascade activation as would be predicted for an ELISA measuring levels of iC3b, a cleavage fragment of complement component C3 formed following cascade activation. (l) Bar graph showing the relative absorbance values of C3/C4 inactivated serum samples employed in the iC3b ELISA. Note that, unlike in (k) treatment of this serum with zymosan fails to increase levels of iC3b. Thus confirming the specificity of the ELISA by demonstrating that it reflects changes in a species that increases in response to complement cascade activation but is prevented from forming in the absence of functioning C3 and C4. (m) Superimposed scatter blot showing the relative absorbance values of different concentrations of complement component C3 standards purified from human serum using PEG precipitation and DEAE ion chromatography. Note that at all concentrations tested iC3b (generated by the cleavage of C3b with factor I in the presence of factor H) gave a higher absorbance value than uncleaved full length C3 or a subsequent cleavage component C3c (generated by treating iC3b with “trypsin like” proteases). Thus further demonstrating the specificity of this ELISA for iC3b versus the full-length protein or other cleavage components. (n) Representative images of non-transfected HEK 293 cells or those transfected with pULTRA EGFP or pULTRA EGFP T2A C3Ms stained with the same C3 antibody employed in the immunohistochemical analysis depicted in this figure and in Fig. 3, Extended Data Fig. 3, Fig. 5, Extended Data Fig. 8g, and Extended Data Fig. 4. Scale bar = 100 μm. (o) Orthogonal view of a representative structured illumination image showing C3 and VGLUT1 staining in the caudate nucleus of tissue from an HD patient (Vonsattel grade 4). Scale bar = 2 μm. For bar charts, bars depict the mean This experiment was repeated four times. All error bars represent SEM. Stars depict level of significance with *=p < 0.05, **p = <0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

To determine whether complement proteins could contribute to loss of corticostriatal synapses, we measured levels of C3 and its activated cleavage component iC3b (a cognate ligand for microglial CR3), which functions downstream in the complement pathway as an opsonin (marking substances for removal by phagocytic cells)62,63. Extracts from the globus pallidus, a component of the basal ganglion structure64–66, of patients with HD showed higher levels of both C3 and iC3b relative to those found in samples from age-matched controls despite both sets of extracts displaying similar levels of blood contamination (Fig. 1d–f and Extended Data Fig. 1k–m).

IHC analysis of postmortem tissue from the caudate nucleus and cerebellum of patients with HD (Vonsattel grade 2 and grade 4) and age-matched controls also revealed increased association of both complement component C1Q, the initiator of the classical complement cascade (expressed by microglia; Extended Data Fig. 1e) and C3 (expressed by both astrocytes and microglia; Extended Data Fig. 1f,g) with corticostriatal synapses in the caudate nucleus of HD brains. There was, however, no increased association of complement proteins with glutamatergic synapses in the cerebellum (a less disease-affected region), which correlates with the relative preservation of these structures in this region (Fig. 1g,h and Extended Data Fig. 1c,d,o).

Microglia in the HD tissue set displayed a region-specific shift toward a more phagocytic phenotype relative to that seen in age-matched controls, adopting a more amoeboid morphology and possessing higher levels of lysosomal marker CD68 (Fig. 1i,j). Consistent with previous transcriptomic studies, we also found that levels of the microglia-specific complement receptor 3 (CR3) were elevated in the HD globus pallidus; however, with the current sample size, this difference was not statistically significant (Extended Data Fig. 1h).

To test whether complement-mediated microglial synaptic elimination could occur in premanifest HD, we performed quantitative RT–PCR on RNA extracted from two rare samples of caudate nucleus from premanifest HD patients and found that levels of C3 and CR3 transcripts were elevated relative to controls (Extended Data Fig. 1i,j), consistent with a previous study that used unbiased transcriptomic profiling in the BA9 region of premanifest HD patients55. Together these results demonstrate that corticostriatal synapses are selectively and progressively lost in postmortem tissue from patients with HD and that this is accompanied by increased complement protein levels, activation and synaptic localization of complement proteins as well as phenotypic changes in microglia that suggest that complement-mediated synaptic elimination might be contributing to this synaptic pathology.

Early and specific loss of corticostriatal synapses in HD mouse models

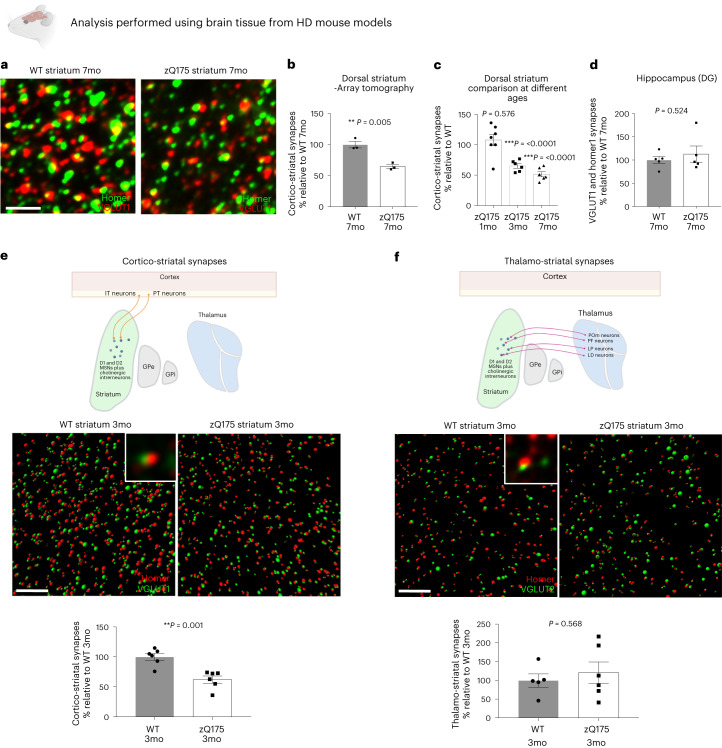

To further explore mechanisms underlying this synaptic pathology and determine whether corticostriatal synapses are selectively vulnerable early in disease, we quantified corticostriatal synapses together with the thalamostriatal synapse population (the other significant source of excitatory input to the striatum)67–69 in the dorsolateral striatum of zQ175 knock-in and BACHD human genomic transgenic mouse models of HD70,71. Both models develop a variety of electrophysiological abnormalities and have a similar timecourse of striatal and cortical atrophy, with zQ175 mice showing relatively mild motor deficits at 7 months of age17,19,22,70–76.

Consistent with previous functional studies that suggested a reduction of glutamatergic inputs onto MSNs, we found ~50% fewer corticostriatal synapses in the dorsolateral striatum of 7-month-old zQ175 mice72,74,77,78 (Fig. 2a–c). Interestingly, this loss was not observed in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, a less disease-affected brain region (Fig. 2d), and was replicated in the BACHD model (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b). Concordantly, immunoblot analysis found reduced levels of synaptic markers in the striatum but not in the less disease-affected cerebellum in 7-month-old zQ175 mice (Extended Data Fig. 2c–i).

Fig. 2. Early and selective loss of corticostriatal synapses in HD.

a, Representative array tomography projections of dorsolateral striatum of 7-month-old zQ175 and WT littermates stained with antibodies to Homer1 and VGLUT1. Scale bar, 3 μm. b, Imaris and MATLAB quantification of synapse numbers in the array tomography projections, n = 3 WT mice and 3 zQ175. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, P = 0.0048. c, Quantification of corticostriatal synapses in the dorsolateral striatum of zQ175 mice at different ages expressed as a % of WT numbers at the same age, n = 7 WT mice and 7 zQ175 mice at 1 month of age; n = 6 WT and 6 zQ175 mice at 3 months of age; and n = 6 WT and 6 zQ175 mice at 7 months of age. Unpaired two-tailed t-test relative to WT at each age at 1 month of age P = 0.576, at 3 months of age P = 0.000064 and at 7 months of age P = 0.000007. d, Quantification of VGLUT1-labeled glutamatergic synapses in the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus of 7-month-old zQ175 mice and WT littermates, n = 5 WT mice and 5 zQ175 mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, P = 0.524. e, SIM images show a significant reduction in the number of corticostriatal synapses in the dorsolateral striatum of 3-month-old zQ175 mice. Pictograms show synapses defined as presynaptic and postsynaptic spheres (rendered around immunofluorescent puncta) whose centers are less than 0.3 μm apart. Inset shows a representative example of co-localized presynaptic and postsynaptic puncta rendered through SIM imaging. Scale bar, 5 μm. Bar chart shows MATLAB quantification of corticostriatal synapses, n = 6 WT mice and 6 zQ175 mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, P = 0.001. f, SIMs showing no difference in the numbers of thalamostriatal synapses at 3 months of age as denoted by staining with the presynaptic marker VGLUT2. Scale bar, 5 μm. Bar chart shows quantification of these images, n = 5 WT and 6 zQ75 mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, P = 0.568. For bar charts, bars depict the mean. All error bars represent s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. GPe, globus pallidus externa; GPi, globus pallidus internus; IT, intratelencephalic; LD, laterodorsal nucleus; LP, lateral posteria nucleus; mo, months old; POm, posterior medial nucleus; PF, parafascicular thalamic nucleus; PT, pyramidal tract; SIM, structured illumination microscopy.

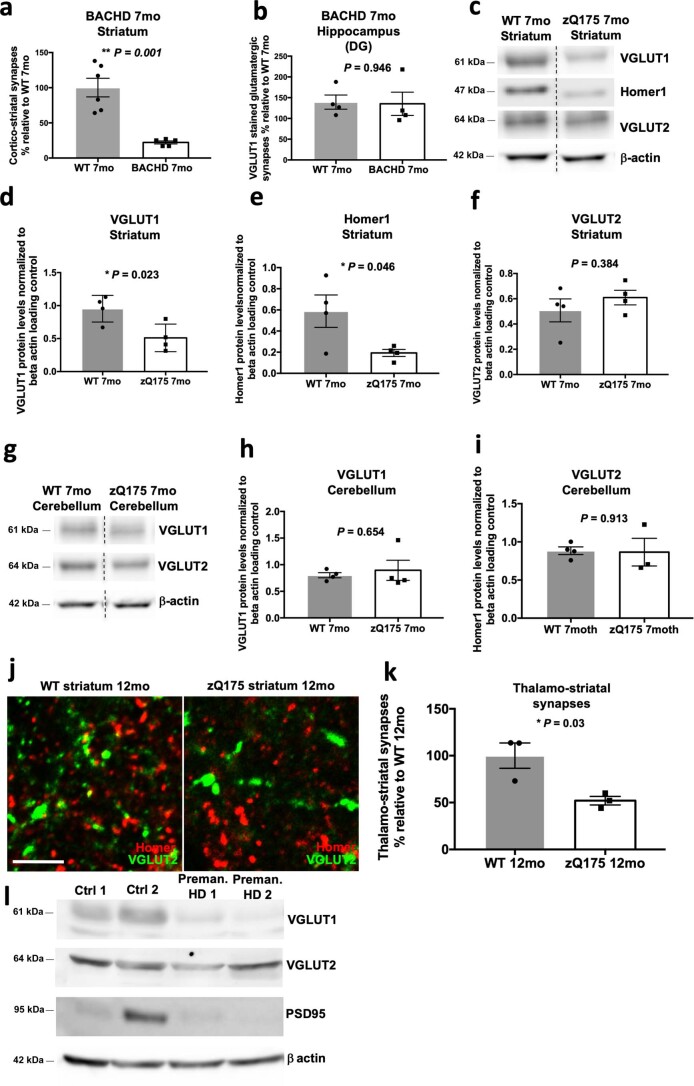

Extended Data Fig. 2. Early and selective loss of corticostriatal synapses in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease.

(a) Bar chart shows quantification of corticostriatal synapses in the dorsolateral striatum of 7 mo BACHD mice and WT littermates, n = 6 WT 5 BACHD mice (3 F and 3 M for WT and 2 F and 3 M for BACHD). Unpaired two-tailed t-test p = 0.001. (b) Bar chart shows quantification of VGLUT1 stained glutamatergic synapses in the hippocampus (dentate gyrus) of 7 mo BACHD mice and WT littermates, n = 4 WT and 4 BACHD mice (2 F and 2 M for both genotypes). Unpaired two-tailed t-test p = 0.946. (c) Representative immunoblot showing that levels of pre and postsynaptic markers of the corticostriatal synapse, VGLUT1 and Homer1 respectively, are reduced in the striatum of 7 mo zQ175 mice relative to that seen in WT littermate controls but levels of the thalamostriatal synapse marker, VGLUT2, are not. Hashed lines are used to denote the fact that non-adjacent lanes from the same immunoblot are being depicted. Images showing the full lane chemiluminescent signal can be found in Source data 1. (d,e,f) Bar charts showing quantification of the relative protein levels of these synaptic markers in 7 mo zQ175 mice and WT littermates, n = 4 WT and 4 zQ175 mice (2 F and 2 M for both genotypes). Unpaired two-tailed t-tests, VGLUT1 p = 0.0227; Homer1 p = 0.0455; VGLUT2 p = 0.3836 (g) Representative immunoblot showing that protein levels of VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 are not changed in the cerebellum of 7 mo zQ175 mice relative to that seen in WT littermate controls. Hashed lines are used to denote the fact that non adjacent lanes from the same immunoblot are being depicted. Images showing the full lane chemiluminescent signal can be found in Source data 1. (h,i) Bar charts showing quantification of relative protein levels in the cerebellum of 7 mo zQ175 mice and WT littermates, for VGLUT1 n = 4 WT and 4 zQ175 mice (2 F and 2 M for both genotypes) for VGLUT2 n = 4 WT and 3 zQ175 mice (2 F and 2 M for WT and 2 F and 1 M for zQ175). Unpaired two-tailed t-tests, VGLUT1 p = 0.654; VGLUT2 p = 0.913. (j) Representative confocal images of VGLUT2 and Homer1 staining in the dorsolateral striatum of 12 mo zQ175 mice and WT littermates. Scale bar = 5 μm. (k) Bar chart shows quantification of colocalized VGLUT2 and Homer1 puncta denoting thalamostriatal synapses in these mice, n = 3 WT and 3 zQ175 mice (2 F and 1 M for both genotypes). Unpaired two-tailed t-test, p = 0.03 (l) Immunoblot of protein samples from the caudate nucleus of two premanifest HD patients and two clinically normal individuals stained with antibodies to VGLUT1, VGLUT2, PSD95 and β actin. Note the reduction in VGLUT1 levels (a marker of the corticostriatal synapse) and decrease in PSD-95 levels (a marker of the postsynaptic density) but no change in VGLUT2 levels (a marker of the thalamostriatal synapse), n = 2 caudate samples from control (clinically normal; see Methods and supplemental table 2) individuals and 2 caudate samples from individuals with premanifest HD. Images showing the full lane chemiluminescent signal can be found in source data 2. For bar charts, bars depict the mean. All error bars represent SEM. Stars depict level of significance with *=p < 0.05, **p = <0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

To test whether synapse loss occurs before onset of motor and cognitive deficits, we repeated the analysis in 3-month-old zQ175 mice and still saw a significant reduction of corticostriatal synapses (Fig. 2c,e). Notably, this did not appear to result from a developmental failure in synapse formation as, consistent with previous findings, no difference could be detected at 1 month of age in these mice (Fig. 2c)79.

The striatum receives excitatory inputs from both the cortex and thalamus, which can be distinguished by staining for presynaptic vesicular proteins VGLUT1 and VGLUT2, respectively67,68,80–84. Using antibodies to these markers, we found that corticostriatal synapses, but not thalamostriatal synapses, were lost in 3-month-old zQ175 mice (Fig. 2e,f). Only when mice were old enough to display motor deficits were both synaptic populations reduced, in line with previous reports in other HD models70,85–87 (Extended Data Fig. 2j,k). One group reported fewer thalamostriatal synapses in a different region of the striatum on postnatal day 21 (P21) and P35, presumably reflecting a developmental failure of synapse formation, although they used a different combination of synaptic markers that have been shown to be dependent on synaptic maturity for their localization at synaptic contacts79,88.

Consistent with the selective vulnerability of corticostriatal synapses, immunoblot analysis of two rare samples of caudate nucleus from premanifest HD patients also showed reductions in levels of corticostriatal marker VGLUT1 and postsynaptic marker PSD95 but not thalamostriatal marker VGLUT2 (Extended Data Fig. 2l), further suggesting selective vulnerability of the corticostriatal connection in HD. Taken together, these results show that corticostriatal synapse loss is an early event in the pathogenesis of mouse models of HD, occurring before onset of motor and cognitive deficits.

Complement components are upregulated and specifically localize to vulnerable corticostriatal synapses in HD mouse models

Emerging research implicates classical complement cascade activation in synaptic elimination both during normal development and in disease and injury contexts30–36. To test whether complement proteins could mediate selective loss of corticostriatal synapses, we investigated whether levels of C1q and C3 were elevated in disease-vulnerable brain regions. IHC analysis revealed that, similar to our findings in the postmortem caudate nucleus of patients with HD, levels of C1q and C3 were elevated in the striatum and motor cortex of 7-month-old zQ175 mice but not in the less disease-affected hippocampus (dentate gyrus)17,89 (Fig. 3a,b,d,e). In line with other studies, we found C1q to be predominantly expressed by microglia, whereas C3 was expressed by ependymal cells lining the lateral ventricle wall (Extended Data Fig. 3h,i)90,91. Both complement proteins were also significantly elevated at 3 months of age in the dorsolateral striatum of zQ175 mice, correlating with the earliest timepoint that we observed fewer corticostriatal synapses (Fig. 3c,f). Although further investigation showed no changes at 1 month of age, consistent with the absence of synapse loss at this timepoint, expression of C3 by ependymal cells was already significantly elevated in 2-month-old zQ175 mice, and C3 association with corticostriatal synapses was increased, demonstrating that changes in complement biology occur alongside some of the earliest reported pathologies in this mouse line71,72 (Extended Data Fig. 4a–h). These findings were replicated in the BACHD model (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b).

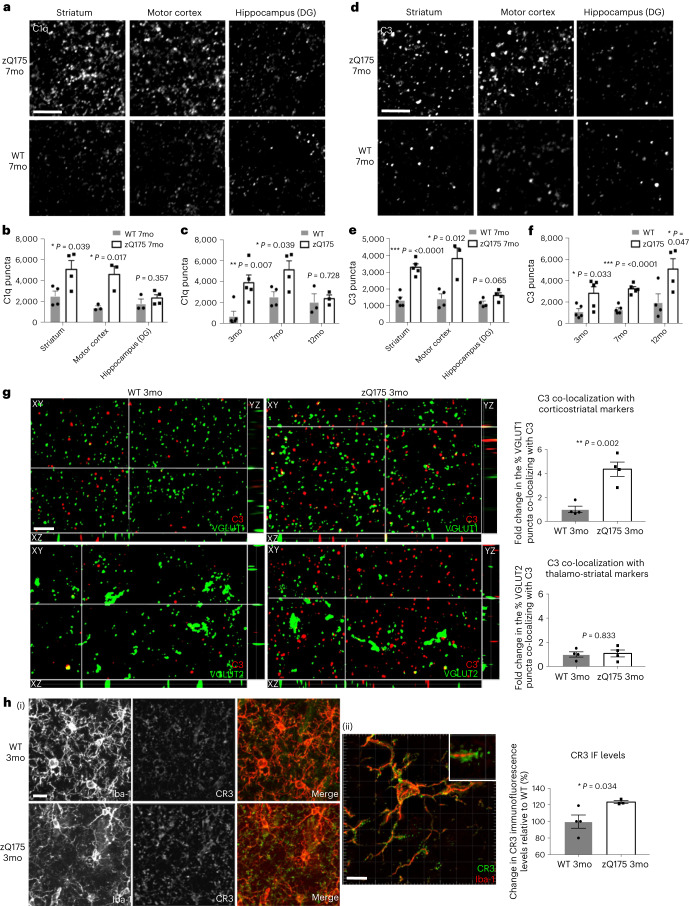

Fig. 3. Complement proteins associate with specific synapses and microglia increase their expression of complement receptors in HD mouse models.

a, Representative confocal images showing C1q staining in disease-affected (dorsolateral striatum and motor cortex) and less-affected regions (dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus) of zQ175 mice and WT littermate controls. Scale bar, 5 μm. b, Quantification of C1q puncta at 7 months of age, striatum n = 4 WT and 4 zQ175 mice, motor cortex n = 3 WT and 3 zQ175 mice and hippocampus n = 3 WT and 4 zQ175 mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test for comparisons of WT and zQ175 in each brain region, striatum P = 0.039, motor cortex P = 0.017 and hippocampus (DG) P = 0.357. c, Quantification of C1q puncta in the dorsolateral striatum at different ages in zQ175 mice and WT littermates—3 months of age n = 5 WT and 5 zQ175 mice; 7 months of age: same data represented in b; and 12 months of age n = 3 WT and 3 zQ175 mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test for comparisons of WT and zQ175 at each age—3 months of age P = 0.007, 7 months of age P = 0.039 and 12 months of age P = 0.728. d, Representative confocal images showing C3 staining in disease-affected and less-affected regions of zQ175 mice and WT littermate controls. Scale bar, 5 μm. e, Quantification of C3 puncta in 7-month-old zQ175 mice and WT littermate controls—striatum n = 5 WT and 5 zQ175 mice, motor cortex n = 4 WT and 3 zQ175 mice and hippocampus (DG) n = 4 WT and 4 zQ175 mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test for comparisons of WT and zQ175 in each brain region—striatum P = 0.000081, motor cortex P = 0.012 and hippocampus (DG) P = 0.065. f, Quantification of C3 puncta in the dorsolateral striatum at different ages in zQ175 mice and WT littermates—3 months of age n = 5 WT and 5 zQ175 mice; 7 months of age: same data represented in e; and 12 months of age n = 4 WT and 4 zQ175 mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test for comparisons of WT and zQ175 at each age—3 months of age P = 0.033, 7 months of age P = 0.000081 and 12 months of age P = 0.047. g, Orthogonal views of SIM images showing C3 and VGLUT1 or C3 and VGLUT2 staining in 3-month-old zQ175 or WT dorsolateral striatum. Scale bar, 5 μm. Bar charts show MATLAB quantification of co-localized C3 and VGLUT puncta from Imaris-processed images, n = 4 WT and 4 zQ175 mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-tests for comparisons of WT and zQ175—VGLUT1 and C3 P = 0.002; VGLUT2 and C3 P = 0.833. h (I), Representative confocal images of CR3 and Iba1 staining in the dorsal striatum of 3-month-old zQ175 and WT mice. Although levels of microglia (and macrophage) marker Iba1 do not change (Extended Data Fig. 4g), CR3 levels are increased in the process tips of microglia from zQ175 mice. Scale bar, 10 μm. h (II), SIM image showing CR3 localized to the process tips of microglia in the dorsal striatum of zQ175 mice. Scale bar, 10 μm. Bar chart shows quantification of average CR3 fluorescence intensity in the dorsal striatum, n = 4 WT and 3 zQ175 mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, P = 0.034. For bar charts, bars depict the mean. All error bars represent s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. mo, months old. IF, immunofluorescence.

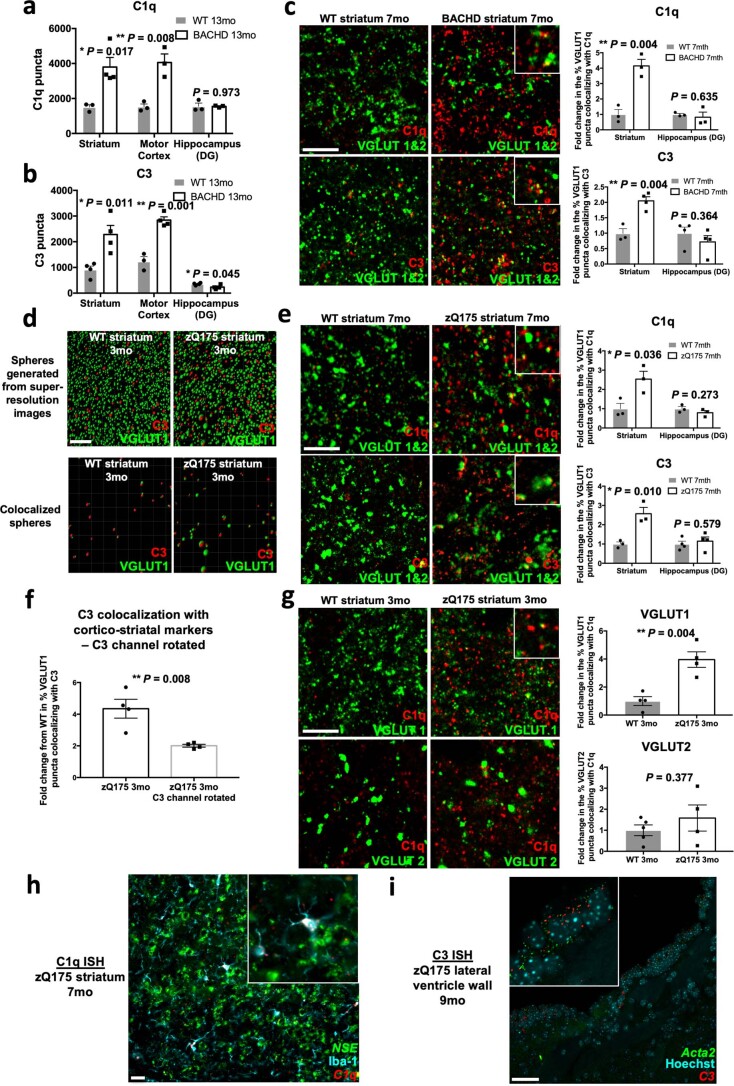

Extended Data Fig. 3. Complement proteins associate with specific synaptic connections in HD mouse models.

(a) Bar charts showing quantification of C1q puncta in different brain regions of 13 mo BACHD mice and WT littermates. In disease affected regions (dorsolateral striatum and motor cortex) of BACHD mice but not the less affected dentate gyrus there is a significant increase in the levels of C1q relative to that seen in WT littermates, striatum n = 3 WT and 4 BACHD mice (2 F and 1 M for WT and 2 F and 2 M for BACHD), motor cortex n = 3 WT and 3 BACHD mice (2 F and 1 M for both genotypes) and hippocampus (DG) n = 3 WT and 3 BACHD mice (2 F and 1 M for both genotypes). Unpaired two-tailed t-test for comparisons of WT and BACHD in each brain region, striatum p = 0.017, motor cortex p = 0.008, hippocampus (DG) p = 0.973. (b) Bar charts showing quantification of C3 puncta in different brain regions of 13 mo BACHD mice and WT littermates, striatum n = 4 WT and 4 BACHD mice (2 F and 2 M for both genotypes), motor cortex n = 3 WT and 4 BACHD mice (2 F and 1 M for WT and 2 F and 2 M for BACHD) and hippocampus (DG) n = 4 WT and 4 BACHD mice (2 F and 2 M for both genotypes). Unpaired two-tailed t-test for comparisons of WT and BACHD in each brain region, striatum p = 0.011, motor cortex p = 0.001, hippocampus (DG) p = 0.045. (c) Representative confocal images of the dorsolateral striatum of 7 mo WT and BACHD mice co-stained with C1q and VGLUT1 and 2 or C3 and VGLUT1 and 2. Note the increased association of both complement proteins with these synaptic markers in the BACHD tissue. Insets show examples of complement proteins co-localized with the presynaptic markers VGLUT1 and 2. Scale bar = 5 μm. Bar charts show quantification of the percentage of VGLUT 1 and 2 puncta colocalizing with C1q or C3 in the disease affected striatum and less disease affected hippocampus (DG), for C1q n = 3 WT and 3 BACHD mice (1 F and 2 M for WT and 2 F and 1 M for BACHD) for C3 n = 3 WT and 4 BACHD mice (2 F and 1 M for WT and 2 F and 2 M for BACHD). Unpaired two-tailed t-test for comparisons of WT and BACHD, Striatum C1q p = 0.004, Hippocampus (DG) C1q p = 0.635, Striatum C3 p = 0.004, Hippocampus (DG) C3 p = 0.364 (d) Representative pictographs of Imaris processed super-resolution images from the dorsolateral striatum of 7 mo WT and zQ175 mice co-stained with C3 and VGLUT1 in which the spheres function has been used to reflect immunoreactive puncta. The top two panels show all spheres generated from the super-resolution images and the bottom panels only show C3 and VGLUT1 spheres which are colocalized (defined as a distance of 0.3 μm or less between the center of each sphere). Scale bar = 5 μm. Note that there are more colocalized spheres in the 3 mo zQ175 striatum than in the 3 mo WT striatum. Quantification of these images is shown in the bar charts in Fig. 3g. (e) Confocal images of the dorsolateral striatum of 7 mo WT and zQ175 mice co-stained with C1q and VGLUT1 and 2 or C3 and VGLUT1 and 2. Bar charts show quantification of the percentage of VGLUT1 and 2 puncta colocalizing with C1q or C3 in disease affected regions (striatum) or less affected regions (dentate gyrus of the hippocampus), for C1q n = 3 WT and 3 zQ175 mice (3 F and 3 M for both genotypes), for C3 striatum n = 3 WT and 3 zQ175 mice (3 F and 3 M for both genotypes) and for C3 hippocampus (DG) n = 4 WT and 4 zQ175 mice (2 F and 2 M for both genotypes). Unpaired two-tailed t-test for comparisons of WT and zQ175, Striatum C1q p = 0.036, Hippocampus (DG) C1q p = 0.273, Striatum C3 p = 0.010, Hippocampus (DG) C3 p = 0.579. (f) Bar chart comparing the fold enrichment of C3 at VGLUT1 puncta in 3 mo zQ175 mice (taken from Fig. 3g) with that same analysis carried out after rotating the C3 channel 90 degrees, n = 4 WT and 4 zQ175 mice (2 F and 2 M for both genotypes). Unpaired two-tailed t-test p = 0.008 (g) Representative confocal images of the dorsolateral striatum of 3 mo zQ175 and WT mice co-stained with antibodies to C1q and VGLUT1 or C1q and VGLUT2. Scale bar = 5 μm. Bar charts show quantification of the % of VGLUT1 or VGLUT2 puncta colocalizing with C1q in both genotypes, for VGLUT1 n = 4 WT and 4 zQ175 mice (2 F and 2 M for both genotypes), for VGLUT2 n = 5 WT and 4 zQ175 mice (3 F and 2 M for WT and 2 F and 2 M for zQ175). Unpaired two-tailed t-test for comparisons of WT and zQ175, VGLUT1 p = 0.004, VGLUT2 p = 0.377 (h) Representative in situ hybridization (ISH) staining of C1q and NSE together with IHC for Iba1 in the dorsal striatum of 7 mo zQ175 mice. Inset shows a magnification of a selected area in the field. Scale bar = 20 μm. This experiment was repeated four times. (i) Representative ISH staining of C3 and Acta2 in the wall of the lateral ventricle. Inset shows a magnification of a selected area in the field Scale bar = 50 μm. This experiment was repeated three times. For bar charts, bars depict the mean. All error bars represent SEM. Stars depict level of significance with *=p < 0.05, **p = <0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

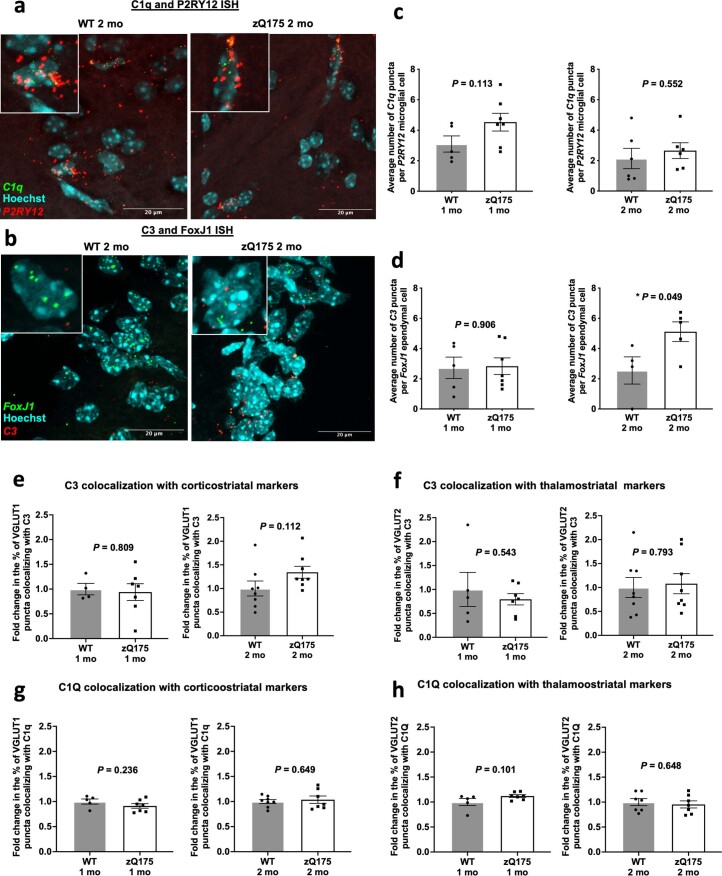

Extended Data Fig. 4. Expression and synaptic localization of complement proteins in HD mouse models.

(a) Representative in situ hybridization (ISH) staining of C1q and P2RY12 in the dorsal striatum of a 2 mo zQ175 mouse and a WT littermate. (b) Representative ISH staining of C3 and FoxJ1 in the wall of the lateral ventricle of a 2 mo zQ175 mouse and a WT littermate. For both a and b scale bar = 20 μm. (c) Bar charts showing quantification of RNAScope staining with the average number of IF C1q puncta in P2RY12 expressing microglia (in the dorsal striatum) determined for zQ175 mice and WT littermates at both 1 and 2 mo; 1 mo n = 5 WT and 7 zQ175 (3 F and 2 M for WT and 3 F and 4 M for zQ175) and 2 mo n = 6WT and 6 zQ175 (2 F and 4 M for WT and 3 F and 3 M for zQ175). Unpaired t test, at 1 mo p = 0.113 and at 2 mo p = 0.552. (d) Bar charts showing quantification of RNAScope staining with the average number of IF C3 puncta in FoxJ1 ependymal cells (present in the wall of the lateral ventricle) determined for zQ175 mice and WT littermates at both 1 and 2 mo; 1 mo n = 5 WT and 7 zQ175 (3 F and 2 M for WT and 3 F and 4 M for zQ175) and 2 mo n = 4 WT and 5 zQ175 (2 M and 2 F for WT and 2 F and 3 M for zQ175). Unpaired t test, at 1 mo p = 0.906 and at 2 mo p = 0.049. (e) Bar chart showing quantification of the percentage of VGLUT1 puncta colocalizing with C3 in the dorsolateral striatum of 1 and 2 mo zQ175 mice and WT littermates; At 1 mo n = 4 WT and 7 zQ175 mice (2 F and 2 M for WT and 4 M and 3 F for zQ175) and at 2 mo n = 8 WT and 8 zQ175 mice (2 F and 6 M for WT and 3 F and 5 M for zQ175). Unpaired two-tailed t-test, at 1 mo p = 0.809 and at 2 mo p = 0.112. (f) Bar chart showing quantification of the percentage of VGLUT2 puncta colocalizing with C3 in the dorsolateral striatum of 1 and 2 mo zQ175 mice and WT littermates; At 1 mo n = 5 WT and 7 zQ175 mice (2 F and 3 M for WT and 4 M and 3 F for zQ175) and at 2 mo n = 8 WT and 8 zQ175 mice (2 F and 6 M for WT and 3 F and 5 M for zQ175). Unpaired two-tailed t-test, at 1 mo p = 0.543 and at 2 mo p = 0.793. (g) Bar chart showing quantification of the percentage of VGLUT1 puncta colocalizing with C1Q in the dorsolateral striatum of 1 and 2 mo zQ175 mice and WT littermates; At 1 mo n = 5 WT and 7 zQ175 mice (2 F and 3 M for WT and 4 M and 3 F for zQ175) and at 2 mo n = 8 WT and 7 zQ175 mice (2 F and 6 M for WT and 3 F and 4 M for zQ175). Unpaired two-tailed t-test, at 1 mo p = 0.236 and at 2 mo p = 0.649. (h) Bar chart showing quantification of the percentage of VGLUT2 puncta colocalizing with C1Q in the dorsolateral striatum of 1 and 2 mo zQ175 mice and WT littermates; At 1 mo n = 5 WT and 7 zQ175 mice (2 F and 3 M for WT and 4 M and 3 F for zQ175) and at 2 mo n = 7 WT and 7 zQ175 mice (2 F and 5 M for WT and 3 F and 4 M for zQ175). Unpaired two-tailed t-test, at 1 mo p = 0.101 and at 2 mo p = 0.648. All error bars represent SEM. Stars depict level of significance with *=p < 0.05, **p = <0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

To assess whether C1q and C3 preferentially localize to specific subsets of synapses, we co-stained sections with antibodies to both complement proteins together with markers of corticostriatal and thalamostriatal synapses. We found a significantly higher percentage of glutamatergic synapses co-localized with C1q and C3 in the dorsolateral striatum but not in the hippocampus of 7-month-old zQ175 and BACHD mice relative to wild-type (WT) littermate controls (Extended Data Fig. 3c,e). This is consistent with unbiased proteomic assessments that showed enrichment of C1q in isolated synaptic fractions from the striatum of 6-month-old zQ175 mice92. Strikingly, at 3 months of age, when there is a selective loss of corticostriatal synapses in zQ175 mice, we observed an increased percentage of this synaptic population co-localizing with both C3 and C1q but no increased association of complement proteins with neighboring thalamostriatal synapses (Fig. 3g and Extended Data Figs. 3g and 4e–h). To demonstrate that this increase was not a result of a random association, we repeated the analysis with the C3 images rotated 90°, to simulate a chance level of co-localization, and saw that, for zQ175 mice, the association of complement proteins with corticostriatal markers (relative to that seen in WT littermates) was significantly reduced (Extended Data Fig. 3f).

CR3 is expressed exclusively by myeloid cells in the brain and binds to cleaved forms of C3 that opsonize cell membranes, prompting engulfment and elimination of these structures. In the dorsal striatum of 3-month-old zQ175 mice, CR3 levels were significantly increased and localized to microglia processes (Fig. 3h). Collectively, these results show that complement proteins localize specifically to vulnerable corticostriatal synaptic connections before onset of motor and cognitive deficits and that levels of their receptors are elevated on microglial cells, thereby demonstrating that they are present at the right time and place to mediate selective elimination of corticostriatal synapses.

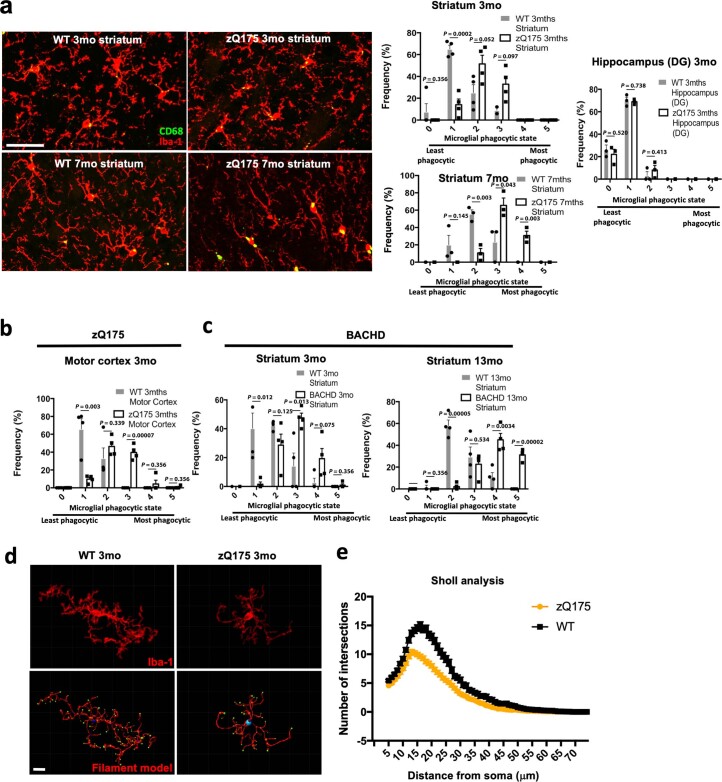

Microglia engulf corticostriatal projections and synaptic elements in HD mouse models

To test whether microglia engulf synaptic elements in HD models, we first investigated region-specific changes in microglia phenotypes consistent with adoption of a more phagocytic state93,94. Using an established combination of markers that incorporates both changes in cell morphology (Iba1) and CD68 lysosomal protein levels30,95, we found a significant shift toward a more phagocytic microglial phenotype in the striatum and motor cortex (another disease-affected brain region96,97) of 3-month-old and 7-month-old zQ175 mice. However, this was not seen in the less disease-affected hippocampus (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). Similar changes in morphology were observed using Sholl analysis, and a shift in phagocytic state was also seen in the striatum of BACHD mice (Extended Data Fig. 5c–e). To establish that the observed cells were not invading monocytes, we co-stained with Iba1 and microglia identity markers Tmem119 and P2ry12 (Extended Data Fig. 6a–c)98,99. Like complement proteins, phagocytic microglia are, thus, present at the right time and place to play a role in synaptic elimination.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Microglia in the striatum and motor cortex of HD mice adopt a more phagocytic profile.

(a) Representative maximum intensity projections generated from confocal images of Iba1 and CD68 staining in the dorsal striatum of 3 and 7 mo zQ175 mice and their WT littermates. Scale bar = 20 μm. Note the increased level of the lysosomal marker CD68 and the reduced branching and thicker process of the microglia in the zQ175 mice at both ages. Bar charts show quantification of the phagocytic state of microglia in these images with 5 being the most phagocytic and 0 the least. At both 3 and 7 mo microglia in the dorsal striatum of zQ175 mice show a shift towards a more phagocytic state, for 3 mo n = 4 WT and 4 zQ175 mice (2 F and 2 M for both genotypes); for 7 mo n = 3 WT and 3 zQ175mice (3 F and 3 M for both genotypes). Multiple unpaired two-tailed t-tests, at 3 mo for score 0 p = 0.356, for score 1 p = 0.0002, for score 2 p = 0.052, for score 3 p = 0.097; at 7 mo for score 1 p = 0.145, for score 2 p = 0.003, for score 3 p = 0.043, for score 4 p = 0.003. This is not the case in less disease affected regions such as the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, n = 3 WT and 3 zQ175 mice. Multiple unpaired two-tailed t-tests for score 0 p = 0.520, for score 1 p = 0.738, for score 2 p = 0.413. (b) Bar chart showing quantification of microglial phagocytic state in the motor cortex of 3 mo zQ175 mice and WT littermates. There is a shift towards a more phagocytic state in the zQ175 mice, n = 4 WT and 4 zQ175 mice (2 F and 2 M for both genotypes). Multiple unpaired two-tailed t-tests for score 1 p = 0.003, for score 2 p = 0.339, for score 3 p = 0.00007, for score 4 p = 0.356, for score 5 p = 0.356. (c) Bar charts, showing that there is also a shift towards a more phagocytic microglial state in the striatum of 3 mo and 13 mo BACHD mice, for both 3 mo and 13 mo n = 4 WT and 4 BACHD mice (2 F and 2 M for both genotypes). Multiple unpaired two-tailed t-tests for 3 mo score 1 p = 0.012, for score 2 p = 0.125, for score 3 p = 0.013, for score 4 p = 0.075 and for score 5 p = 0.356; for 13 mo score 1 p = 0.356, for score 2 p = 0.00005, for score 3 p = 0.534, for score 4 p = 0.0034, score 5 p = 0.00002. (d) Confocal images and filament renderings of individual microglia stained with Iba1 in the dorsal striatum of 3 mo zQ175 mice and WT littermates. Scale bar = 10 μm. In the filament renderings the blue sphere indicates the soma, orange spheres denote branch points and green spheres indicate terminal points of microglial processes. (e) Sholl analysis of confocal images of microglia from the dorsal striatum of 3 mo zQ175 mice and WT littermates. Analysis was performed on filament rendered images using Imaris software, n = 3 WT and 4 zQ175 mice (2 F and 1 M for WT and 2 F and 2 M for zQ175) with over 100 cells analyzed per genotype. Two way anova, p = <0.0001 with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test shows a significant difference between WT and zQ175 at distances from the soma ranging from 11 to 30 μm p < 0.0001. For bar charts, bars depict the mean. All error bars represent SEM. Stars depict level of significance with *=p < 0.05, **p = <0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

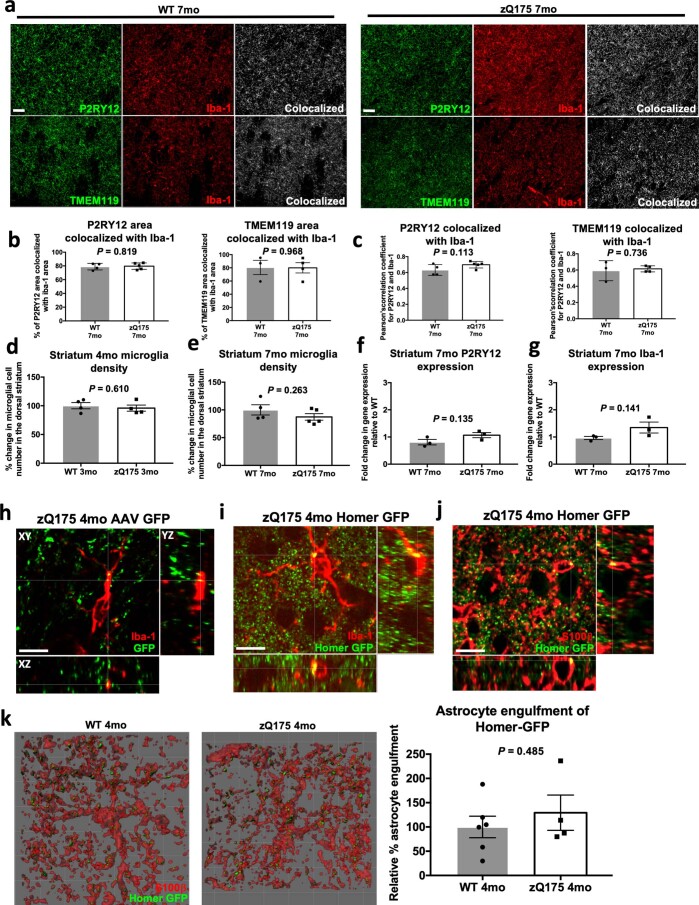

Extended Data Fig. 6. Microglia density and their levels of identity markers do not change in HD mice and striatal astrocytes do not engulf a greater amount of synaptic material.

(a) Confocal images of microglia in the dorsal striatum of 7 mo zQ175 mice and WT littermates co-stained with antibodies to Iba1 and putative microglia identity markers P2RY12 and TMEM119. Scale bar = 50 μm (b) Bar charts show the % of P2RY12 and TMEM119 immunoreactive area above a set threshold (determined using an algorithm developed by Costes and Lockett203) that colocalizes with the area of Iba1 staining for the images in (a), for P2RY12 and Iba1 n = 4 WT and 5 zQ175 mice (2 F and 2 M for WT and 3 F and 2 M for zQ175); for TMEM119 and Iba1 n = 3 WT and 4 zQ175 mice (2 F and 1 M for WT and 2 M and 2 F for zQ175). Unpaired two-tailed t-test for comparison of WT and zQ175 mice, for P2RY12 and Iba1 p = 0.819 and for TMEM119 and Iba1 p = 0.968. (c) Bar charts show the Pearson’s correlation coefficient for Iba1 and P2RY12 and Iba1 and TMEM119 for the images shown in (a), for P2RY12 and Iba1 n = 4 WT and 5 zQ175 mice (2 F and 2 M for WT and 3 F and 2 M for zQ175); for TMEM119 and Iba1 n = 3 WT and 4 zQ175 mice (2 F and 1 M for WT and 2 M and 2 F for zQ175). Unpaired t test for comparison of WT and zQ175 mice P2RY12 and Iba1 p = 0.113 and for TMEM119 and Iba1 p = 0.736. (d) Bar chart shows quantification of microglial cell density in the dorsal striatum of 4 mo zQ175 mice and WT littermates, n = 4 WT and 4 zQ175 mice (2 F and 2 M for both genotypes). Unpaired two-tailed t-test p = 0.610. (e) Bar chart shows quantification of microglial cell density in the striatum of 7 mo Q175mice and WT littermates, n = 4 WT and 5 zQ175 mice (2 F and 2 M for WT and 3 F and 2 M for zQ175). Unpaired two-tailed t-test p = 0.263 (f) Bar chart shows the level of P2RY12 transcripts in striatal extracts from 7 mo zQ175 mice and WT littermates, n = 3 WT and 3 zQ175 mice (3 F and 3 M for both genotypes). Unpaired two-tailed t-test p = 0.135. (g) Bar chart shows the level of Iba1 transcripts in striatal extracts from 7 mo zQ175 and mice and WT littermates, n = 3 WT and 3 zQ175 mice (3 F and 3 M for both genotypes). Unpaired two-tailed t-test p = 0.141. (h) Representative orthogonal view of an Iba1 stained microglia in the dorsal striatum of a 4 mo zQ175 mice that had previously received a motor cortex injection of pAAV2-hsyn-EGFP at P1/2. Scale bar = 10 μm This experiment was repeated 6 times. (i) Representative orthogonal view of an Iba1 stained microglia in the dorsal striatum of a 4 mo zQ175 Homer-GFP mouse. Scale bar = 10 μm. This experiment was repeated 5 times. (j) Representative orthogonal view of an S100β stained astrocyte in the dorsal striatum of a 4 mo zQ175 Homer-GFP mouse. Scale bar = 10 μm. This experiment was repeated four times. (k) Representative surface rendered images of S100β stained astrocytes (red) and engulfed Homer-GFP inputs (green) in the dorsal striatum of 4 mo zQ175 Homer-GFP mice and WT Homer-GFP littermates. Scale bar = 10 μm. Bar chart shows quantification of the relative % astrocyte engulfment of Homer-GFP (the volume of engulfed Homer-GFP expressed as a percentage of the total volume of the astrocyte) in 4 mo zQ175 Homer-GFP mice relative to that seen in WT Homer-GFP littermate controls, n = 6 WT Homer-GFP and 4 zQ175 Homer-GFP mice (3 F and 3 M for WT Homer-GFP and 2 F and 2 M for zQ175 Homer-GFP mice). Unpaired two-tailed t-test, p = 0.485. For bar charts, bars depict the mean. All error bars represent SEM. Stars depict level of significance with *=p < 0.05, **p = <0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

To directly test whether microglia engulf more corticostriatal inputs in HD mice, we labeled cortical neurons with a stereotactic injection of pAAV2-hsyn-EGFP into the motor cortex of PD1 zQ175 and WT littermate mice (schematized in Fig. 4a). Microglial engulfment in the ipsilateral dorsal striatum was then assessed at 4 months of age (as described in refs. 95,100). We found that microglia in the striatum of 4-month-old zQ175 mice contained a greater volume of labeled projections compared to WT littermate controls (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 6h). Notably, no differences in the number of Iba1-stained cells or transcripts for microglia-specific markers, which could have confounded interpretation of these data, were detected in the zQ175 striatum (Extended Data Fig. 6d–g).

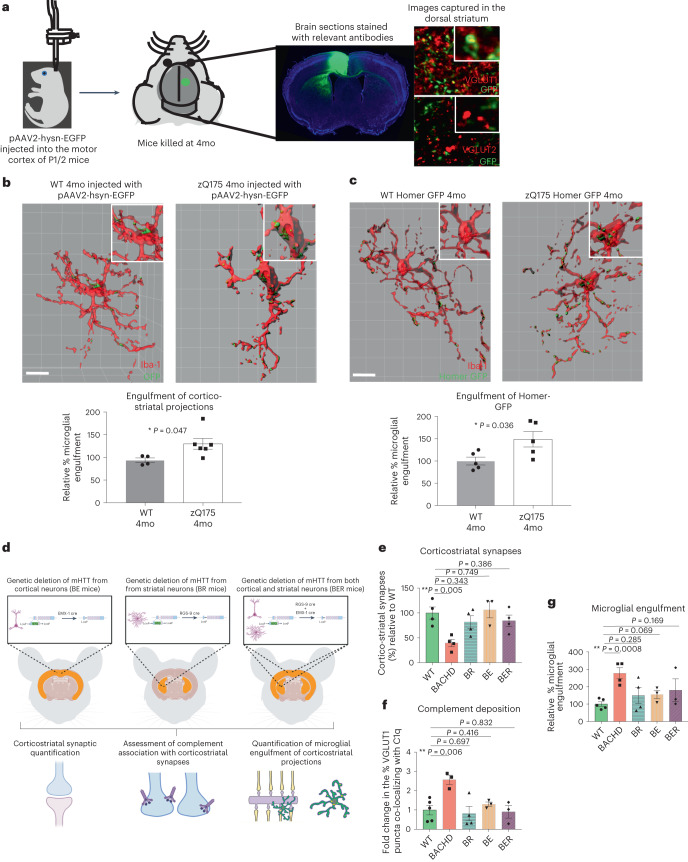

Fig. 4. Microglia in the striatum of HD mice engulf more corticostriatal projections and synaptic material in a manner that is dependent on expression of neuronal mHTT.

a, Schematic showing labeling of corticostriatal projections with pAAV2-hsyn-EGFP injection into the motor cortex of neonatal mice. Panels to the right show co-localization of GFP signal in the dorsal striatum with VGLUT1, a marker of the corticostriatal synapse, but not VGLUT2, a marker of the thalamostriatal synapse. b, Representative surface-rendered images of Iba1+ microglia and engulfed GFP-labeled corticostriatal projections in the dorsal striatum of 4-month-old zQ175 and WT mice. Scale bar, 10 μm. Bar chart shows quantification of the relative % microglia engulfment (the volume of engulfed inputs expressed as a percentage of the total volume of the microglia) in 4-month-old zQ175 mice relative to that seen in WT littermate controls. All engulfment values were normalized to the total number of inputs in the field, n = 4 WT and 6 zQ175 mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, P = 0.047. c, Representative surface-rendered images of Iba1+ microglia and engulfed Homer-GFP in the dorsal striatum of 4-month-old zQ175 Homer-GFP mice and WT Homer-GFP littermates. Scale bar, 10 μm. Bar charts show quantification of the relative % microglia engulfment of Homer-GFP in 4-month-old zQ175 Homer-GFP mice relative to that seen in WT Homer-GFP littermate controls, n = 5 WT Homer-GFP and 5 zQ175 Homer-GFP mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, P = 0.036. d, Schematic showing the strategy that we adopted to genetically ablate mHTT from striatal neurons or cortical neurons or both populations before interrogating corticostriatal synaptic density, complement association with corticostriatal markers and microglial-mediated engulfment of these synapses in these mice. e, Quantification of the % of corticostriatal synapses in the dorsal striatum of BACHD, BR (deletion of mHTT in striatal neurons), BE (deletion of mHTT in cortical neurons) and BER (deletion of mHTT in striatal and cortical neurons) mice normalized to those seen in WT littermates, n = 4 WT mice, 4 BACHD mice, 4 BR mice, 3 BE mice and 4 BER mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test with comparison to WT, BACHD P = 0.005, BR P = 0.343, BE P = 0.749 and BER P = 0.386. f, % of VGLUT1 puncta co-localized with C1q in the dorsal striatum of BACHD, BR, BE and BER mice and WT littermate controls, n = 5 WT mice, 3 BACHD mice, 4 BR mice, 3 BE mice and 3 BER mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test with comparison to WT, BACHD P = 0.006, BR P = 0.697, BE P = 0.416 and BER P = 0.832. g, Quantification of the relative % microglial engulfment of corticostriatal projections in the dorsal striatum of BACHD, BR, BE, BER and WT mice, n = 5 WT mice, 4 BACHD mice, 4 BR mice, 3 BE mice and 3 BER mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test with comparison to WT, BACHD P = 0.0008, BR P = 0.285, BE P = 0.069 and BER P = 0.169. For bar charts, bars depict the mean. All error bars represent s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. mo, months old.

As this viral labeling method does not distinguish between engulfment of presynaptic bouton structures and axonal material, which might come from exosomes released from neurons or axosome shedding, we used a transgenic method to specifically assay engulfment of synaptic elements. zQ175 mice were crossed with mice in which postsynaptic marker homer1c is fused to a GFP tag (hereafter referred to as homer-GFP)101. Microglia in the dorsal striatum of zQ175 mice engulfed significantly more homer-GFP than those of their WT littermates (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 6i). Interestingly, in line with this result, a recent ultrastructural study found that microglia process interaction with synaptic clefts was also increased before onset of motor deficits in a different HD mouse model51. To ensure that expression of the transgene had not affected pathological synapse loss, we quantified homer-GFP puncta and Homer1 immunoreactive puncta at 7 months of age and saw the expected reduction of both in the zQ175 homer-GFP mice relative to homer-GFP littermates (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b). Collectively, these results show that microglia adopt a more phagocytic phenotype and engulf more synaptic material in the dorsal striatum of zQ175 mice.

Astrocyte dysfunction is linked to corticostriatal circuit abnormalities and motor and cognitive dysfunctions in HD mouse models, and astrocytes can also phagocytose synaptic material during developmental refinement102–105. To test whether astrocytes engulf corticostriatal synapses in HD models, we stained sections from Homer-GFP and zQ175 Homer-GFP mice with astrocyte marker S100β and performed engulfment analysis. Although astrocytes engulf synaptic elements in the striatum, the average volume of engulfed material was not altered in zQ175 mice relative to that seen in WT littermates (Extended Data Fig. 6j,k), demonstrating that engulfment of synaptic material by astrocytes is unlikely to play a significant role in the early synaptic loss that we observed.

Microglial engulfment and synapse loss are driven by mutant huntingtin expression in both cortical neurons and MSNs in the striatum

Mutant huntingtin (mHTT) is expressed ubiquitously; however, previous work demonstrated that specific HD pathologies can be driven by mHTT expression in different cell types10,19,49,106–111. To determine if elimination of corticostriatal synapses requires mHTT in both cortical and striatal neurons, we quantified synapse density, complement deposition and microglial engulfment in BACHD mice in which mHTT had been selectively ablated from the cortex (using Emx1-cre, ‘BE’ mice), striatum (using RGS9-cre ‘BR’ mice) or both (using both Emx-1 and RGS9-cre, ‘BER’ mice)19 (schematized in Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 1g). We found that genetic deletion of mHTT from the cortex, striatum or both completely rescued the loss of synapses normally seen in the BACHD model (Fig. 4e), consistent with a previous study showing that synaptic marker loss and corticostriatal synaptic transmission deficits are ameliorated by genetically deleting mHTT in either striatal or cortical neurons19. In addition, deposition of complement component C1q, as well as microglial engulfment, was reduced to WT levels (Fig. 4f,g). Thus, mHTT expression in both MSNs and cortical neurons is specifically required to initiate the complement deposition, microglial engulfment of synaptic elements and synapse loss that we observed in the BACHD model.

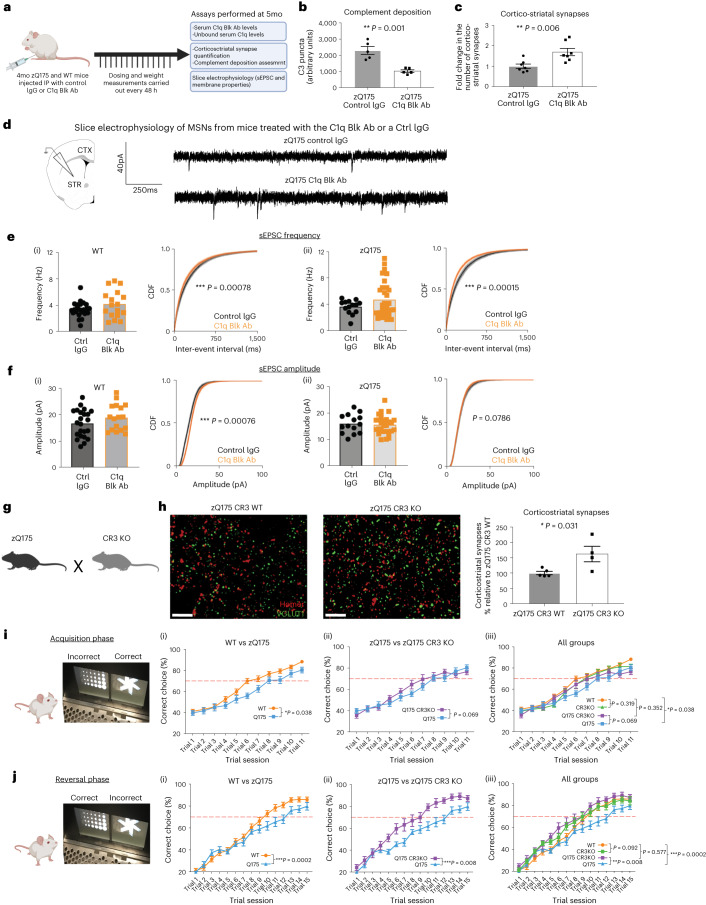

Early loss of corticostriatal synapses is rescued by inhibiting activation of the classical complement pathway or genetically ablating microglial CR3

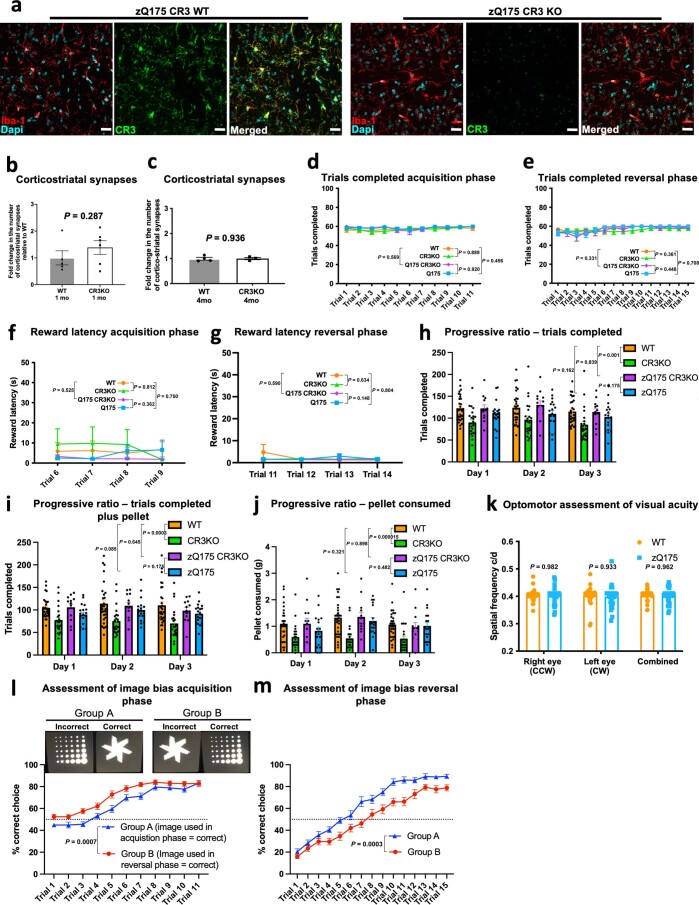

To test whether increased synaptic complement deposition and engulfment of corticostriatal inputs by microglia mediates selective elimination of these synapses in zQ175 mice, we blocked these processes using several approaches. To prevent microglial interaction with bound complement proteins, we genetically ablated CR3 in zQ175 mice (Extended Data Fig. 7a). This increased the number of corticostriatal synapses present in the dorsolateral striatum by 60% relative to zQ175 littermates expressing CR3 (Fig. 5g,h). This increase was not due to persistent effects related to differences in developmental pruning, as has been observed at the retinogeniculate synapse in CR3KO mice, or other aspects of altered biology, as CR3 ablation on a WT background did not alter corticostriatal synapse number at either 1 month or 4 months of age (Extended Data Fig. 7b,c). CR3 ablation also did not change the percentage of corticostriatal synapses found to be associated with C1q or C3, confirming that deposition of these proteins is an upstream event in the synaptic elimination mechanism and also that these complement proteins are not immediately cleared from synaptic terminals through other mechanisms (Extended Data Fig. 9d,e).

Extended Data Fig. 7. Blocking complement deposition can reduce synaptic loss in HD mice.

(a) Representative confocal images of the dorsal striatum of 4 mo zQ175 CR3 WT and 4 mo zQ175 CR3 KO mice stained with antibodies to Iba-1 and CR3. Scale bar = 20 µm. For bar charts, bars depict the mean and all error bars represent SEM. Stars depict level of significance with *=p < 0.05, **p = <0.01 and ***p < 0.0001. (b) Bar chart showing quantification of corticostriatal synapses in the dorsolateral striatum of 1 mo CR3KO mice and WT littermates, n = 5 WT mice and 6 CR3KO mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test p = 0.287. (c) Bar chart showing quantification of corticostriatal synapses in the dorsolateral striatum of 4 mo CR3KO mice and WT littermates, n = 4 WT mice and 3 CR3KO mice (2 F and 2 M for WT and 2 F and 1 M for CR3KO). Unpaired two-tailed t-test p = 0.9356. (d) Line graph showing the mean number of trials completed on each trial day for each genotype during the acquisition phase (maximum = 60), n = 29 WT mice (16 M, 13 F), 18 zQ175 mice (8 M, 10 F), 24 CR3KO mice (13 M, 11 F) and 13 zQ175 CR3KO mice (9 M, 4 F). Two way anova: for WT vs zQ175 p = 0.535 for the combination of genotype x trial session as a significant source of variation and p = 0.456 for genotype as a significant source of variation (shown on graph); for zQ175 vs zQ175 CR3KO p = 0.501 for the combination of genotype x trial session as a significant source of variation and p = 0.920 for genotype as a significant source of variation (shown on graph); for WT vs zQ175 CR3KO p = 0.689 for the combination of genotype x trial session as a significant source of variation and p = 0.569 for genotype as a significant source of variation (shown on graph); for WT vs CR3 KO p = 0.908 for the combination of genotype x trial session as a significant source of variation and p = 0.889 for genotype as a significant source of variation (shown on graph). (e) Line graph showing the mean number of trials completed on each trial day for each genotype during the reversal phase (maximum = 60), n = 29 WT mice, 18 zQ175 mice, 24 CR3KO mice and 13 zQ175 CR3KO mice. Two way anova: for WT vs zQ175 p = 0.787 for the combination of genotype x trial session as a significant source of variation and p = 0.708 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for zQ175 vs zQ175 CR3KO p = 0.899 for the combination of genotype x trial session as a significant source of variation and p = 0.448 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT vs zQ175 CR3KO p = 0.960 for the combination of genotype x trial as a significant source of variation and p = 0.331 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT vs CR3 KO p = 0.132 for the combination of genotype x trial session as a significant source of variation and p = 0.361 for genotype as a significant source of variation. (f) Line graph showing reward latency for each genotype for trial days 6,7,8 and 9 in the acquisition phase, n = 29 WT mice, 18 zQ175 mice, 24 CR3KO mice and 13 zQ175 CR3KO mice. Two way anova: for WT vs zQ175 p = 0.499 for the combination of genotype x trial session as a significant source of variation and p = 0.750 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for zQ175 vs zQ175 CR3KO p = 0.526 for the combination of genotype x trial session as a significant source of variation and p = 0.362 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT vs zQ175 CR3KO p = 0.868 for the combination of genotype x trial as a significant source of variation and p = 0.525 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT vs CR3 KO p = 0.240 for the combination of genotype x trial session as a significant source of variation and p = 0.812 for genotype as a significant source of variation. (g) Line graph showing reward latency for each genotype for trial days 11,12,13 and 14 in the reversal phase, n = 29 WT mice, 18 zQ175 mice, 24 CR3KO mice and 13 zQ175 CR3KO mice. Two way anova: for WT vs zQ175 p = 0.487 for the combination of genotype x trial session as a significant source of variation and p = 0.804 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for zQ175 vs zQ175 CR3KO p = 0.271 for the combination of genotype x trial session as a significant source of variation and p = 0.148 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT vs zQ175 CR3KO p = 0.751 for the combination of genotype x trial as a significant source of variation and p = 0.590 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT vs CR3 KO p = 0.431 for the combination of genotype x trial session as a significant source of variation and p = 0.634 for genotype as a significant source of variation. (h) Bar chart showing the average total number of trials completed by each genotype in the progressive ratio task, n = 29 WT mice, 18 zQ175 mice, 24 CR3KO mice and 13 zQ175 CR3KO mice. Two way anova: for WT vs zQ175 p = 0.919 for the combination of genotype x testing day as a significant source of variation and p = 0.162 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for zQ175 vs zQ175 CR3KO p = 0.391 for the combination of genotype x testing day as a significant source of variation and p = 0.175 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT vs zQ175 CR3KO p = 0.583 for the combination of genotype x testing day as a significant source of variation and p = 0.839 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT vs CR3 KO p = 0.754 for the combination of genotype x testing day as a significant source of variation and p = 0.0012 for genotype as a significant source of variation. (i) Bar chart showing the average total number of trials completed by each genotype in the progressive ratio task when the assay is conducted in the presence of a food pellet, n = 29 WT mice, 18 zQ175 mice, 24 CR3KO mice and 13 zQ175 CR3KO mice. Two way anova: for WT vs zQ175 p = 0.813 for the combination of genotype x testing day as a significant source of variation and p = 0.085 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for zQ175 vs zQ175 CR3KO p = 0.592 for the combination of genotype x testing day as a significant source of variation and p = 0.175 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT vs zQ175 CR3KO p = 0.247 for the combination of genotype x testing day as a significant source of variation and p = 0.645 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT vs CR3 KO p = 0.051 for the combination of genotype x testing day as a significant source of variation and p = 0.0003 for genotype as a significant source of variation. (j) Bar chart showing the amount in grams of a food pellet consumed by each genotype while carrying out the progressive ratio task, n = 29 WT mice, 18 zQ175 mice, 24 CR3KO mice and 13 zQ175 CR3KO mice. Two way anova: for WT vs zQ175 p = 0.470 for the combination of genotype x testing day as a significant source of variation and p = 0.321 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for zQ175 vs zQ175 CR3KO p = 0.399 for the combination of genotype x testing day as a significant source of variation and p = 0.482 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT vs zQ175 CR3KO p = 0.826 for the combination of genotype x testing day as a significant source of variation and p = 0.898 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT vs CR3 KO p = 0.153 for the combination of genotype x testing day as a significant source of variation and p = 0.000015 for genotype as a significant source of variation. (k) Bar chart showing the average performance of WT and zQ175 mice in the optomotor assay of visual acuity, n = 33 WT mice (18 M, 15 F) and 28 zQ175 mice (15 M, 13 F). Two way anova for WT vs zQ175 p = 0.598 for genotype as a significant source of variation with p = 0.982, 0.933 and 0.962 for the right eye, left eye or the combined performance of both respectively via Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. (l) Line graph showing image bias during the acquisition phase of the visual discrimination task, n = 15 WT mice in group A (where the image presentation is the same as that used for the testing in Fig. 5i) and 15 WT mice in group B (where the image presentation is the reverse of the used for the testing in Fig. 5i). Two way anova for Group A vs Group B p = 0.088 for group x trial as a significant source of variation and p = 0.0007 for group as a significant source of variation. (m) Line graph showing image bias during the reversal phase of the task, n = 15 WT mice in group A (9 M, 6 F) and 15 WT mice in group B (10 M, 5 F). Two way anova for Group A vs Group B p = 0.014 for genotype x group as a significant source of variation and p = 0.0003 for genotype as a significant source of variation. For bar charts, bars depict the mean and all error bars represent SEM. Stars depict level of significance with *=p < 0.05, **p = <0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

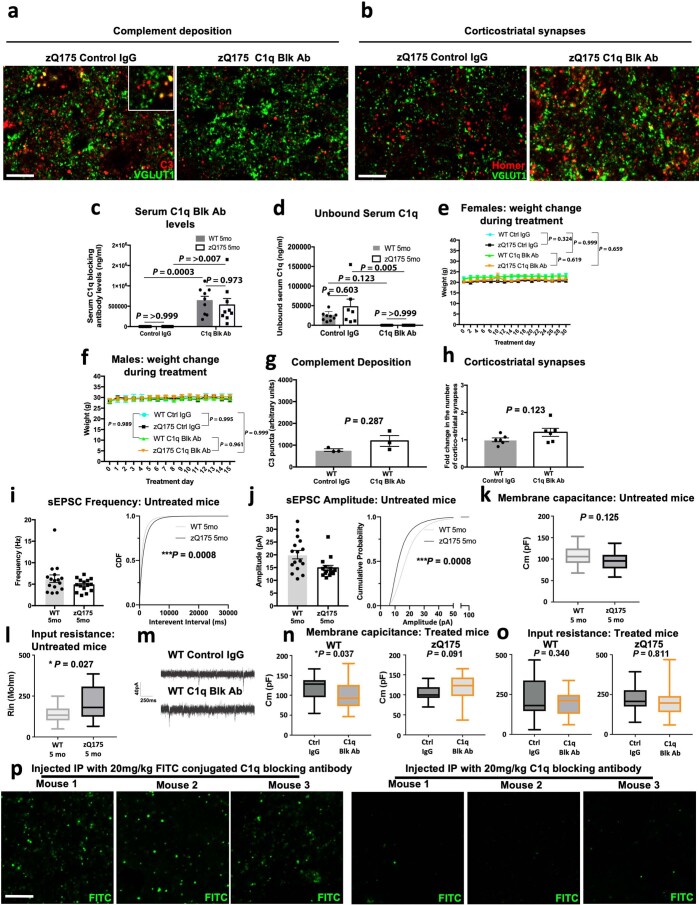

Fig. 5. Blocking complement deposition or microglial recognition of complement opsonized structures can reduce synaptic loss and prevent the development of cognitive deficits in HD mice.

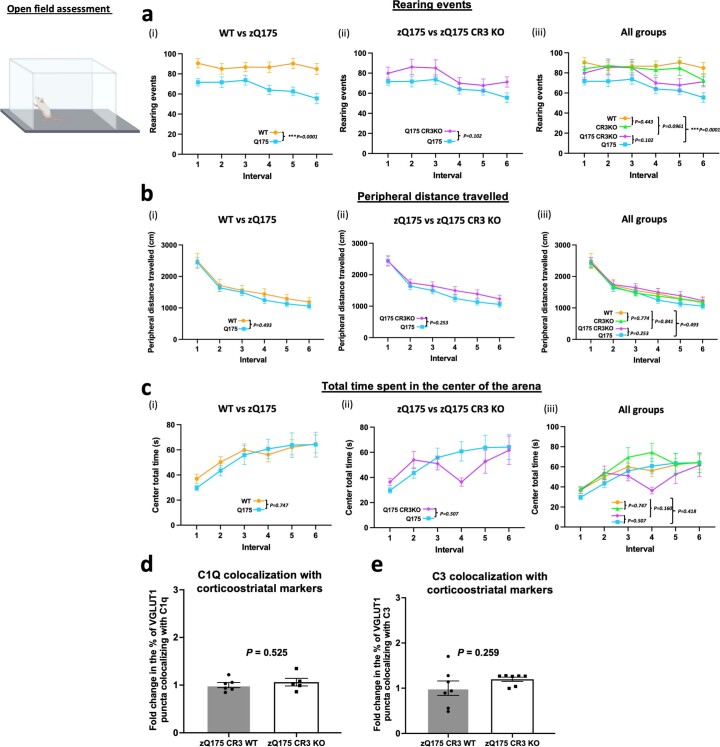

a, Schematic showing the experimental paradigm in which 4-month-old zQ175 mice and WT littermates were treated with the C1q Blk Ab or a control IgG for 1 month before being euthanized. b, Quantification of C3 puncta in the dorsolateral striatum of zQ175 mice treated with the C1q function-blocking antibody or a control IgG, n = 5 zQ175 mice treated with control IgG and 5 zQ175 mice treated with C1q function-blocking antibody. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, P = 0.001. c, Quantification of corticostriatal synapses in the dorsolateral striatum of zQ175 mice treated with the C1q function-blocking antibody or a control IgG, n = 7 zQ175 mice treated with control IgG and 6 zQ175 mice with the C1q function-blocking antibody. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, P = 0.006. d, Diagram depicting the strategy for carrying out electrophysiology recordings from coronal sections of treated mice and representative traces of sEPSCs recorded from MSNs in striatal slices from 5-month-old zQ175 mice that had been treated for 1 month with control IgG or the C1q function-blocking antibody. e, Cumulative distribution plots of inter-spike intervals (ISIs) obtained from whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings of MSN sEPSCs. Recordings were carried out in slices from WT and zQ175 mice after a 1-month treatment with control IgG or the C1q function-blocking antibody (Black = Control IgG, Orange = C1q function-blocking antibody). Bar charts show average frequency (Hz) per cell recorded across conditions. n = 23 cells from 7 mice for WT Ctrl IgG; n = 17 cells from 7 mice for WT C1q Blk Ab; n = 14 cells from 4 mice for zQ175 Ctrl IgG; and n = 23 cells from 7 mice for zQ175 C1q Blk Ab. For the cumulative distribution plots for WT, P = 0.00078, and for zQ175, P = 0.00015. f, Cumulative distribution plots of amplitude obtained from the same whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings of MSN sEPSCs as in e. Black = Control IgG, Orange = C1q function-blocking antibody. Bar charts show average amplitude (pA) per cell recorded across conditions for the same cells/mice represented in e. For the cumulative distribution plots, for WT P = 0.00076 and for zQ175 P = 0.0786. g, Diagram showing the two transgenic mice lines crossed together to generate the genotypes employed in assessments of visual discrimination learning and reversal performance. h, Representative SIM images of Homer1 and VGLUT1 staining in the dorsolateral striatum of 4-month-old zQ175 CR3 WT and zQ175 CR3 KO mice. Scale bar, 5 μm. Bar chart shows quantification of corticostriatal synapses, n = 5 zQ175 CR3 WT mice and 4 zQ175 CR3 KO mice. Unpaired two-tailed t-test, P = 0.031. i, After completion of shaping tasks (see Methods for details), the visual discrimination performance of 4-month-old WT, zQ175, CR3 KO and zQ175 CR3 KO mice was assessed using the Bussey–Sakisda operant touchscreen platform. Line charts show performance over 11 trial sessions (60 trials per session) of (i) WT and zQ175 mice, (ii) zQ175 and zQ175 CR3 KO mice and (iii) all groups, n = 29 WT mice, 18 zQ175 mice, 24 CR3KO mice and 13 zQ175 CR3KO mice. Two-way ANOVA: for WT versus zQ175 P = 0.038 for the combination of genotype × trial session as a significant source of variation and P = 0.01 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for zQ175 versus zQ175 CR3KO P = 0.069 for the combination of genotype × trial session as a significant source of variation and P = 0.568 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT versus zQ175 CR3KO P = 0.352 for the combination of genotype and trial as a significant source of variation and P = 0.068 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT versus CR3 KO P = 0.319 for the combination of genotype × trial session as a significant source of variation and P = 0.593 for genotype as a significant source of variation. j, After completion of the acquisition phase, visual presentations were switched so that the visual stimuli previously associated with reward provision were now the incorrect choice. Performance of WT, zQ175, CR3 KO and zQ175 CR3 KO mice in this reversal phase of the task was then assessed using the Bussey–Sakisda operant touchscreen platform. Line charts show performance over 15 trial sessions (60 trials per session) of (i) WT and zQ175 mice, (ii) zQ175 and zQ175 CR3 KO mice and (iii) all groups, for the same mice tested in i. Two-way ANOVA: for WT versus zQ175 P = 0.0002 for the combination of genotype × trial session as a significant source of variation and P = 0.080 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for zQ175 versus zQ175 CR3KO P = 0.008 for the combination of genotype × trial session as a significant source of variation and P = 0.003 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT versus zQ175 CR3KO P = 0.577 for the combination of genotype and trial as a significant source of variation and P = 0.072 for genotype as a significant source of variation; for WT versus CR3 KO P = 0.092 for the combination of genotype × trial session as a significant source of variation and P = 0.304 for genotype as a significant source of variation. For bar charts, bars depict the mean, and all error bars represent s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. CDF, cumulative distribution function.

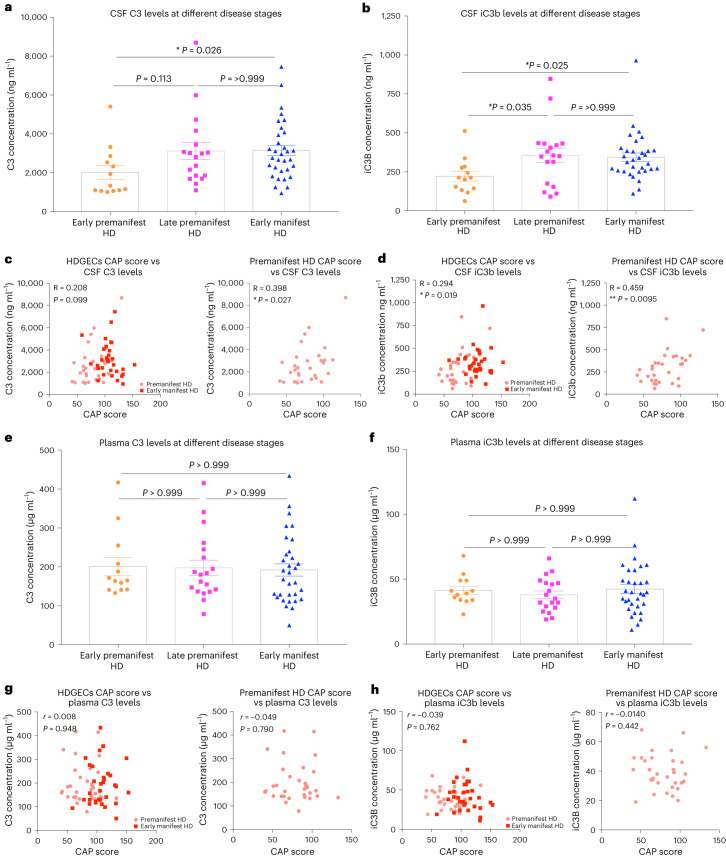

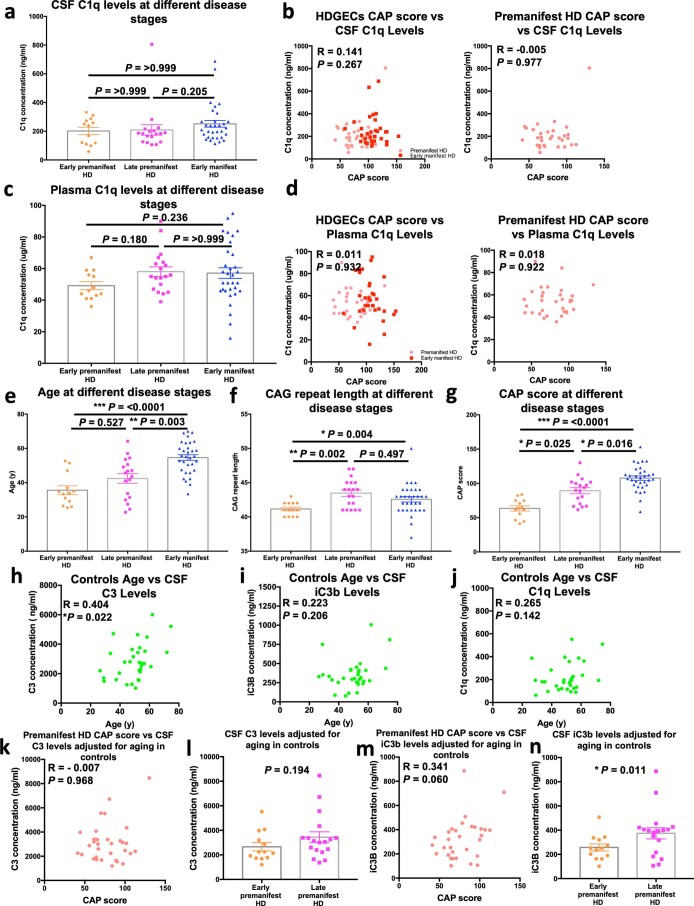

Extended Data Fig. 9. Preventing microglial recognition of complement opsonized structures can reduce development of impairments in some exploratory behaviors in HD mice.