Abstract

Poultry coccidiosis is an important devitalizing enteric protozoan disease caused by a group of obligatory intracellular apicomplexan parasites of the Genus Eimeria contributing to major economic loss in commercial poultry worldwide. As the current method of chemotherapeutic control using ionophores in feed had led to development of drug resistant isolates, the need for development of prophylactic vaccines is the most viable alternate and eco-friendly control strategy as on date. Of the several candidate vaccines, the EmGam 56 is one of the most promising candidates which protect the birds against E. maxima, E. tenella and E. acervulina, the three most pathogenic coccidian species infecting commercial chicken. EmGam56 is a major wall forming component of macrogametocyte of E. maxima and a candidate with high immunogenicity and low virulence. The present study was planned and carried out for the generation of E.coli expressed recombinant gametocyte antigen-EmGam56 using pET 28(a+) as cloning vector and BL21 DE3 (pLysS) as prokaryotic expression system in a Bio-fermentor (New Brunswick™ Scientific BioFlo 310). The recombinant protein was purified by conventional (Ammonium sulphate precipitation) and by automatic purification system (AKTA prime) in Ni-NTA column for a planned immunization trial with experimental chickens.

Keywords: Eimeria maxima, Recombinant protein, EmGam56, Gametocyte antigen, Purification

Introduction

Poultry coccidiosis is the most economically important obligatory intracellular enteric protozoan disease caused by seven Apicomplexan species under the genus Eimeria. The global economic losses due to poultry coccidiosis has been estimated more than USD 14.5 billion (Lee et al. 2022) due to the severe mortality and morbidity and for the cost control measures (Habtamu and Gebre 2019). The current coccidiosis control strategies depends on prophylactic or therapeutic usage of anticoccidial drugs, which can lead to development of drug resistant field strains (Quiroz-Castaneda and Dantan-Gonzalez 2015) and drug residues in the animal food products. There are seven important chicken Eimeria species, of which Eimeria maxima is moderately pathogenic with high immunogenicity.

The homologues of E. maxima gametocyte protein EmGam56 present in E.tenella, E. acervulina and share regions of tyrosine. In addition, the precursor proteins break into smaller identical peptides among the three Eimeria species, which integrated into the inner oocyst wall. The conserved genes presence in the homologous region of EmGam56 confers the cross protection among these 3 Eimeria species (Belli et al. 2009).

Conserved genes for the gametocyte protein (Gam 56) present among these 3 Eimeria species enable the EmGam 56 protein as candidate antigens to provide effective protective immunity against these Eimeria species.

Materials and methods

Propagation of monospecific culture of Eimeria maxima

Day-old coccidian-free commercial White leghorn chicks (BV-300 strain) (n = 20) were procured from Sri Venkateswara Hatcheries (Hyderabad, India) and raised in a sterile brooder cage with provision of ad libitum anticoccidial drugs free water and feed. The birds were examined for Eimeria infection periodically using conventional faecal examination. Birds were challenged with pure E. maxima oocysts culture (from Veterinary College and Research Institute, Namakkal, TamilNadu, India) orally on Day-26. The oocysts were isolated from four days post-challenge (dpc) and propagated by subsequent passages in three weeks old coccidia free birds. The purity of oocysts was evaluated by species-specific nested PCR based on ribosomal Internal Transcribed Spacer-I (ITS-I) region as described by Bhaskaran et al. (2010).

RNA extraction and amplification of EmGam56 coding sequence

The purification, sporulation and excystation of oocysts of E. maxima were done as mentioned by Wallach et al. (1990). Briefly, oocysts were harvested from faecal samples of infected birds using saturated salt solution by flotation technique and purified with 4% hypochlorite solution. The oocysts were incubated with 2.5% (w/v) potassium dichromate solution for 48 h at 25 °C with constant agitation. The sporozoites were obtained by subjecting the oocyst suspension to mechanical disruption using glass beads (1 mm diameter; Sigma-Aldrich, USA), followed by incubating the suspension with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) comprising of 0.25% (w/v) trypsin and 1% (w/v) sodium taurodeoxycholate (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at 41 °C for 3 h in shaker incubator. Total RNA was extracted from sporozoites using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA). The Open Reading Frame of EmGam56 was amplified using the primer sequences (P1:5´-CCCAAGCTTACCATGGCCCGCCTCGGCCTCG-3´ and P2:5´-CCCGAATTCGGTCGTT¬TAGAAGGGCATGG-3´) containing EcoRI and Hind III restriction enzyme sites and under the thermal cyclic condition as described by Xu et al. (2013). The EmGam 56 gene was cloned into prokaryotic expression system using pET 28a(+) (Novogen, NJ) downstream from an NH2-terminal His-6 epitope tag. The insertion of EmGam 56 (1754 bp) in plasmid was verified and transformed into component Escherichia coli BL21pLysS (DE3) cell (Invitrogen, USA).

Expression and purification of recombinant EmGam 56

Isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG, Bangalore Genei, India) (1 mM) was used to induce recombinant protein expression from E.coli clone using mass fermentor (New Brunswick Scientific) at OD600 = 0.6 for overnight at 25 °C with constant agitation (150 rpm). The induced bacterial cells were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C and then centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 20 min. The cleared lysate was prepared and purified using Ni-NTA chromatography under denaturing condition as per the protocol provided by manufacturer (Qiagen, Germany). The protein concentration of purified protein was measured using Bicinchoninic acid kit (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Characterization of purified recombinant EmGam 56 has been done by 12 per cent SDS-PAGE analysis under reducing condition (Laemmli 1970). In Western blot analysis, the antibody reactivity of specific chicken antisera (1:25 dilution-Primary antibody) against purified recombinant EmGam56 protein was confirmed, when 1:400 dilution of rabbit anti-chicken IgG HRP conjugated antibody used as a secondary antibody (Towbin et al. 1979).

Immunisation trial

Day old specific-pathogen free commercial broiler chicks (n = 40) were purchased as day old chicks (IAEC approval letter no.1803/DFBS/IAEC/2019, dated: 31.12.2019) from Suguna Foods Private Limited, Coimbatore. The birds were reared under clean confinement animal house and fed with anticoccidial drug free diet throughout the experiment. The birds were separated into two groups (Group I- EmGam 56, Group II- Infected control). The Group-I were immunized with 50 μg Gam-56 emulsified in Montanide ISA 71 VG adjuvant, intramuscularly on Day-7, followed by same dose of secondary immunization, subcutaneously on Day-14. Both groups of birds were challenged with 20,000 virulent mixed oocyst cultures of E. maxima, E. tenella and E. acervulina, orally on Day-21.

Assessment of protective efficacy of EmGam 56

In the present immunisation trial, the protective efficacy of recombinant EmGam 56 was assessed through challenge experiments in birds using heterologous species of E.maxima, E.tenella and E.acervulina. Previously, the protective efficiency of EmGam 82 and EtMIC1 recombinant proteins were evaluated against heterologous challenge studies in immunized group of chicken (Vijayashanthi et al. 2022). Briefly, the performance parameter of both groups were measured by means of body weight gain using standard weighing balance on 7, 14, 28, 42, and 56 days post immunization (dpi). The parasitological parameters were estimated by oocyst shedding from five days post-challenge (dpc) to 12 dpc using modified Mc master technique and lesion scoring (7dpc to 12 dpc) as evaluated by Raman et al. (2011). The antibody titre of immunized group was estimated by indirect ELISA using pre and post immunization sera (0, 14, 21 and 29 dpi) against recombinant EmGam56.

Results

Expression and purification of recombinant EmGam 56 protein

The scaling up process of E.coli-expressed recombinant EmGam56 yielded 2.5 g of wet bacterial mass/litre under the optimal cultural condition after overnight induction. The total protein concentration of affinity purified EmGam56 was measured as 0.9147 mg/kg by Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method. The antibodies produced in the immunized birds (Group-I) recognised the purified EmGam56 protein at 56 kDa.

Characterisation of purified EmGam 56 protein

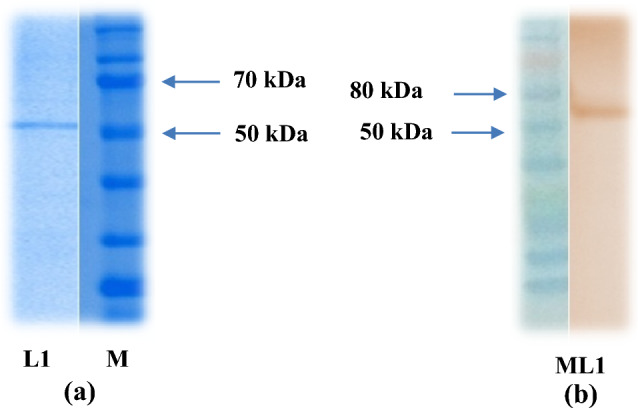

SDS-PAGE analysis (12%) of affinity purified EmGam 56 protein revealed a prominent peptide band at 56 kDa with Coomassie blue stain (Fig. 1a) and the antibody reactivity has been confirmed by using the anti-sera of EmGam56 immunized chicken in western blot assay (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Characterisation (a) and Western blot analysisagainst immunizedanti-EmGam 56 (b) of purified EmGam 56 L1- Purified recombinant EmGam 56, M-Protein marker

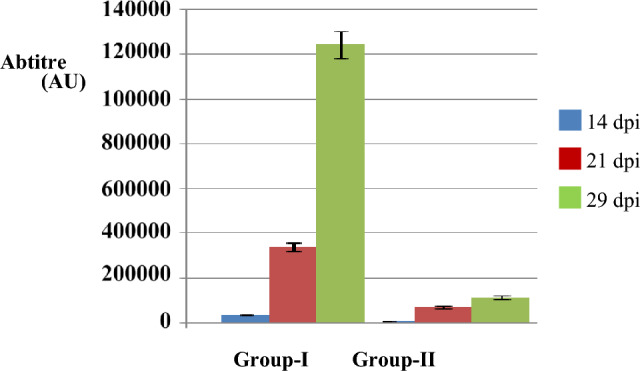

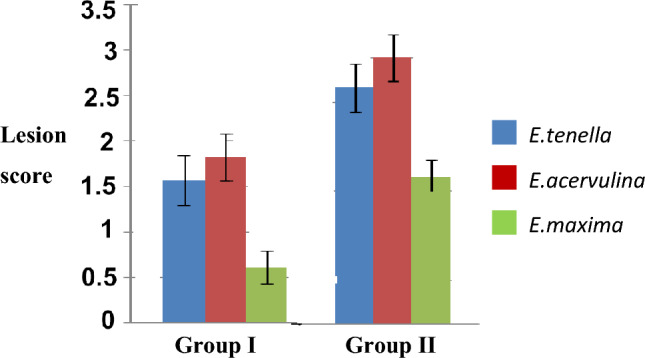

Efficacy of EmGam 56 in immunized group

The average body weight of group of birds immunized with antigen was higher than control group (infected) since 35 dpi (Table 1). The birds immunized with purified EmGam56 showed marked reduction in oocyst output from 8 dpc compared with control (infected) using oocyst flotation technique (Table 2). The antibody titres of group of birds immunized were 127.4 (± 20.23), 365.1(± 45.21) and 1255(± 115.56) on 14, 21 and 29 dpi (Fig. 2). The birds received EmGam56 antigen revealed noticeably lesser intestinal lesions especially against E.maxima compared with control (infected birds) group (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Body weight gain (in kg)

| Average weight gain of birds | EmGam 56 | Infected control |

|---|---|---|

| 7 days old | 125.05 | 127.31 |

| 14 days old | 293.5467 | 306.0251 |

| 28 days old | 657.3867 | 604.451 |

| 42 days old | 1055.141 | 965.111 |

| 56 days old | 1529.31 | 1432.11 |

Table 2.

Oocyst output (OPG)

| Groups | 5 dpc | 6 dpc | 7 dpc | 8dpc | 9 dpc | 10 dpc | 11 dpc | 12 dpc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EmGam 56 | 98,104 | 213,568 | 40,102 | 27,558 | 43,003 | 25,282 | 19,320 | 8014 |

| Infected control | 11,242 | 351,500 | 597,628 | 95,378 | 58,021 | 40,680 | 23,342 | 10,705 |

Fig. 2.

Comparison of antibody response of birds immunized with EmGam-56 (Group-I) with control (infected) (Group-II) against anti-EmGam 56 chicken sera

Fig. 3.

Comparison ofaverage intestinal lesion score on 7dpc of birds immunized with EmGam 56 birds (Group I) with birds challenged with mixed oocyst culture of E. maxima, E. acervulina and E. tenella (control) (Group-II)

Discussion

As of now, there is no indigenously manufactured live anticoccidial vaccine available for commercial poultry in India. The currently available imported vaccines are from exotic strains of coccidia with few reports of low efficacy due to genetic diversity of the field isolates (Fornace et al. 2013; Blake et al. 2021). Moreover, development and production of live attenuated oocyst vaccine requires continuous passage of Eimeria oocyst through several batches of live chicken, which is time consuming, laborious and expensive. Hence research works on recombinant anticoccidial vaccines are gaining importance worldwide, replacing the live vaccines. Among the several vaccine candidates, EmGam56, Gam82 and EtMIC1 were found as potential candidates offering higher protection for the most pathogenic species of Eimeria affecting the commercial poultry. Most of these proteins are structural components of apicomplexan developmental stages and play major role in host-parasite relationship and invasion. Among the several protein targets, Gam56 has been used in the present study as it is considered as the major oocyst wall forming component of the genus Eimeria and a good target for immune response. The gametocyte antigen also induces transmission blocking immunity and the maternal antibodies may pass through egg yolk to the embryos providing protection in birds up to 8 weeks of age (Wallach et al. 2008). Immunization of hens with affinity purified gametocyte antigen (APGA) of E.maxima induced cross-species maternal immunity against E. acervulina and E. tenella infection (Wallach et al. 1995).

The characterization of purified recombinant EmGam 56 in this study revealed a prominent band at 56 kDa as observed earlier using mass spectrometry analysis (Belli et al. 2002). In the present study, the immunized birds were found to have higher body weight gain than the non-immunized control birds as observed in several such studies (Wallach et al. 2008; Xu et al. 2013). The immunized group showed lesser oocyst output than non-immunized infected control group (Ding et al. 2012). Whereas, the higher dose of E.maxima oocyst in experimental infection showed negative impact on average body weight gain in infected birds than mild infection (Teng et al. 2021).

The antibody titre of immunized bird group in this study increased approximately ten-fold times on 29 dpi than 14 dpi and non-immunized infected control group. Birds immunized with recombinant APGA containing Gam 56 antigen observed significant level of antibody response even after 10–12 weeks of primary immunization (Belli et al. 2004).

Ding et al. 2012 reported that the birds immunized with higher doses (1.5 ml or 3 ml) of anti-GST-Gam56 IgY antibodies showed 3–4 folds lesser oocyst shedding and lesion score along with significantly higher body weight gain than immunized group with lower dose (0.3 ml) and infected control group. The immunized birds with EtGam 56 showed reduced morbidity and mortality rate. However, the progeny of immunized breeder hens with purified Gametocyte antigen of E.maxima (CoxAbic) confers maternal immunity along with 63% reduction in total oocyst shedding (Wallach et al. 2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Project Director, Translational Research Platform for Veterinary Biologicals, Centre for Animal Health Studies, Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Chennai for providing the laboratory facilities and Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science Technology, Govt of India for the financial support provided.

Funding

This research work was funded by Department of Biotechnology, Ministry of Science Technology, Government of India (DBT Sanction no.102/IFD/DBT/SAN.2680/2011–2012).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Necessary ethical approval was obtained for this study as per IAEC Approval Letter No. 1803/DFBS/IAEC/2019 of Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Chennai-7.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Belli SI, Leea M, Thebo P, Wallach MG, Schwartsburd B, Smith NC. Biochemical characterisation of the 56 and 82 kDa immunodominant gametocyte antigens from Eimeria maxima. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:805–816. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belli SI, Mai K, Skene CD, Gleeson MT, Witcombe DM, Katrib M, Finger A, Wallach MG, Smith NC. Characterisation of the antigenic and immunogenic properties of bacterially expressed, sexual stage antigens of the coccidian parasite, Eimeria maxima. Vaccine. 2004;22:4316–4325. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belli SI, Ferguson DJ, Katrib M, Slapetova I, Mai K, Slapeta J, Flowers SA, Miska KB, Tomley FM, Shirley MW, Wallach MG, Smith NC. Conservation of proteins involved in oocyst wall formation in Eimeria maxima, Eimeria tenella and Eimeria acervulina. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskaran MS, Venkatesan L, Aadimoolam R, Harikrishnan TJ, Sriraman R. Sequence diversity of internal transcribed spacer-1 (ITS-1) region of Eimeria infecting chicken and its relevance in species identification from Indian field samples. Parasitol Res. 2010;106:513–521. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1696-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake D, Vrba V, Xia D, Danladi Jatau I, Spiro S, Nolan MJ, Underwood G, Tomley F. Genetic and biological characterisation of three cryptic Eimeria operational taxonomic units that infect chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus) Int J Parasitol. 2021;51(8):621–634. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2020.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Liu QR, Han JP, Qian WF, Liu Q. Anti-recombinant gametocyte 56 protein IgY protected chickens from homologous coccidian infection. J Integ Agri. 2012;11(10):1721–1728. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(12)60176-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornace KM, Clark EL, Macdonald SE, Namangala B, Karimuribo E, Awuni JA, Thieme O, Blake DP, Rushton J. Occurrence of Eimeria species parasites on small-scale commercial chicken farms in Africa and indication of economic profitability. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e84254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habtamu Y, Gebre T. Poultry coccidiosis and its economic impact: review article. Br Poult Sci. 2019;8(3):76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during theassembly of heat of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Lu M, Lillehoj HS. Coccidiosis: recent progress in host immunity and alternatives to antibiotic strategies. Vaccines. 2022;10:215. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10020215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiroz-Castaneda RE, Dantan-Gonzalez E. Control of avian coccidiosis: future and present natural alternatives. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2015/430610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman M, Banu SS, Gomathinayagam S, DhinakarRaj G. Lesion scoring technique for assessing the virulence and pathogenicity of Indian field isolates of avian of avian Eimeria species. Veterinarski Arhiv. 2011;81(2):259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Teng PY, Choi J, Tompkins Y, Lillehoj H, Kim W. Impacts of increasing challenge with Eimeria maxima on the growth performance and gene expression of biomarkers associated with intestinal integrity and nutrient transporters. Vet Res. 2021;52:81. doi: 10.1186/s13567-021-00949-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin HT, Staehelin TT, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1979;76(9):4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayashanthi R, Raman M, Kasthuri B, Madan N, Azhahianambi P, Dhinakarraj G. Development of subunit vaccine against poultry coccidiosis. Ind J Vet Sci and Biotech. 2022;18(1):7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wallach M, Pillemer YarusS, Halabi A, Pugatsch T, Mencher D. Passive immunization of chickens against Eimeria maxima infection with a monoclonal antibody developed against agametocyte antigen. Infect Immun. 1990;58(2):557–562. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.2.557-562.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach M, Smith NC, Petracca M, Miller CMD, Eckert J, Braun R. Eimeria maxima gametocyte antigens: potential use in a subunit maternal vaccine against coccidiosis in chickens. Vaccine. 1995;13:347–354. doi: 10.1016/0264-410X(95)98255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach MG, Ashash U, Michael A, Smith NC. Field application of a subunit vaccine against an enteric protozoan disease. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(12):e3948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Zhang Y, Tao J. Efficacy of a DNA vaccine carrying Eimeria maxima Gam56 antigen gene against coccidiosis in chickens. Korean J Parasitol. 2013;51(2):147–154. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2013.51.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]