Abstract

Introduction

Secondary postpartum hemorrhage is rare. The most common cause is retained placenta. Having a uterine scar dehiscence as an etiology is unusual. Complete dehiscence of the uterine scar is even rarer. This rare but serious cause of post-partum haemorrhage can be potentially life threatening due to severe hemorrhage if not managed in adequate time.

Presentation of case

We present the case of a 35-year-old patient, gravida 2 para 2. She had undergone two caesarean sections in our department and, after the last one in March 2021, she presented twice to our emergency department with relatively abundant metrorrhagia, but neither the clinical nor the radiological examinations revealed any abnormalities. At 43 days postpartum, she presented to the emergency with severe bleeding per vaginum. The bleeding was profuse, causing hemodynamic instability and severe acute anaemia. An explorative laparotomy was necessary to diagnose the etiology and manage the treatment. Surgical exploration revealed a lateral uterine rupture in the broad ligament and complete dislocation of the caesarean scar. An urgent hysterectomy was performed.

Discussion

Partial or complete dehiscence of the hysterorrhoea is a rare cause of secondary postpartum hemorrhage after caesarean section. When hysterorrhaphy dehiscence does occur, the origin of the bleeding is likely to be related to erosion of the vessels at the incision angles.

Conclusion

The diagnosis of partial or complete dehiscence of the uterine scar may be misleading in the absence of specific clinical or radiological signs. This condition must therefore be considered and suspected in cases of secondary postpartum hemorrhage.

Keywords: Caesarean section, Postpartum hemorrhage, Postpartum period, Surgical wound dehiscence, Case report

Highlights

-

•

Partial or complete dehiscence of the uterine scar must be suspected in cases of secondary post-partum haemorrhage.

-

•

Secondary post-partum haemorrhage can be life threatening.

-

•

Post-partum metrorrhagia should not be neglected and should be investigated.

1. Introduction

Secondary postpartum haemorrhage is classically defined as blood loss from the genital tract occurring between 24 h and 6 weeks [1]. While this condition occurs in just under 1 % of women [1], it has been shown to affect only 1/365 of caesarean section patients [2]. The main causes are infection, retained placental fragments or tissue, abnormal involution of the placental site, trophoblastic disease and inherited coagulopathies [2]. It is interesting to note that partial or complete dehiscence of the hysterorrhaphy has been shown to be a rare cause, which can be misleading in diagnosis. Here we describe a case of secondary postpartum haemorrhage due to uterine scar dehiscence to provide a comprehensive overview of the clinical presentation, diagnostic evaluation and management of this pathology that may contribute to the critical prognosis.

2. Case presentation

We are discussing a para 2 living 2 patients. The patient had no significant medical history. She has been monitored since the beginning of the pregnancy in our external consultation. Her pregnancy was without complications. In particular, she did not develop gestational diabetes. Due to the patient's unicatric uterus and transverse presentation, a caesarean section was performed at term and a subserosal dehiscence with a thin lower segment was noted intraoperatively. The extraction of the fetus was complicated by a left-angled extension without vascular damage. Separate sutures were used to repair the hysterorrhaphy and the refund line. The postoperative period was uneventful; the patient had no fever and was discharged 48 h after caesarean section. The patient consulted our emergency department on two occasions, 10 and 23 days postoperatively because of moderately severe metrorrhagia which suddenly resolved. On clinical examination, the patient was hemodynamically stable and had no tachycardia. The pelvic ultrasound revealed no abnormalities, and the hemoglobin level was 9.7 g/d. At 43 days postpartum, she presented to the emergency and she reported an episode of heavy vaginal bleeding at home. There was no previous history of any type of localized injury, fever, offensive vaginal discharge, sexual activity, or antiplatelet/anticoagulant use.

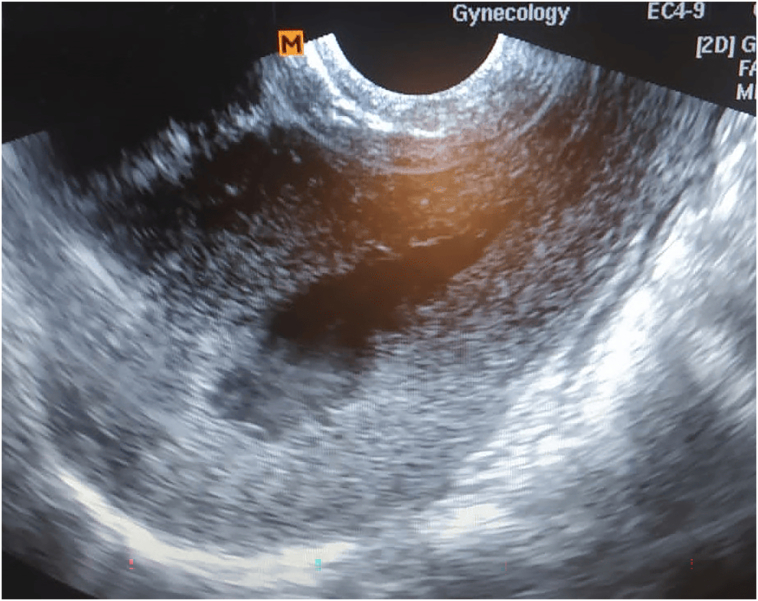

She was well oriented. She had a 110-bpm tachycardia, a blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg, and was quite pale. Lower abdominal pain was found upon abdominal examination, but there was no guarding or rigidity. Her uterus was completely retracted. During the speculum examination, 100 cm3 of clots were extracted from her vagina and the cervix was found to be in good health. There was only mild fresh endouterine bleeding. Compared with the early postoperative period, when hemoglobin was 10.7 g/dl, hemoglobin on admission was 4.7 g/dl. The platelet counts and all coagulation indicators were normal. The βhCG test was negative. Pelvic ultrasound showed a uterus with normal echo structure and size, no evidence of residual placental tissue in the uterine cavity with a hypoechoic intracavitary image of 18 mm without flow on color Doppler suggestive of hematometria (Fig. 1). The patient was kept under observation. She was given conservative treatment and was transfused with three packed red blood cells. The patient was hemodynamically stable, with no tachycardia and a hemoglobin of 7.3 post-transfusion. It was decided to proceed with further investigations. A pelvic angio-MRI to look for an arteriovenous malformation that might explain the clinical presentation with possible uterine artery embolization was planned. Unfortunately, she developed severe active haemorrhage and hemodynamic instability. On examination her blood pressure was 70/40 mmHg and she had a heart rate of 170 bpm. Speculum examination revealed a large amount of heavy red bleeding of endo-uterine origin. At this stage the hemoglobin level was 4.2 g/dl.

Fig. 1.

Sagittal section of the uterus showing a normal-sized uterus with a hematometria of 18 mm.

Considering these findings, the diagnosis of severe secondary haemorrhage was retained. The patient was immediately taken to the operating room where she benefited from rapid and intensive conditioning and resuscitation. The decision to perform an emergency laparotomy was therefore agreed by all members of the team, with the aim of investigating the etiology and managing the severe secondary postpartum haemorrhage. Surgical examination revealed a lateral uterine rupture in the broad ligament and complete dehiscence of the caesarean scar (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). A total inter-adnexal hysterectomy was then performed (Fig. 4). The hysterectomy was indicated in the case of heavy bleeding and a hemodynamically unstable patient. Five units of packed red blood cells were given to the patient. The procedure went off without any problems. The patient was hemodynamically stable at the end of the procedure and she was admitted to the postoperative unit for 48 h for follow-up with uncomplicated post-operative treatment. The surgical procedures were clinically and biologically successful. The post-operative hemoglobin level was 10.2 g/dl. the follow-up was uncomplicated. The patient received antibiotic prophylaxis and treatment to prevent thromboembolic complications. The patient was discharged after five days. The diagnosis was confirmed by anatomopathological examination of the hysterectomy specimen. The work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [3].

Fig. 2.

Per-operative view showing a 6 cm long hematoma of the broad ligament (yellow arrow). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 3.

Per-operative view showing total dislocation of the caesarean section scar (yellow star) communicating with a lateral rupture in the broad ligament (blue arrow). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 4.

Hysterectomy specimen showing the cesarean scar dislocation (green arrow) and the location of the lateral defect (yellow arrow). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3. Discussion

Secondary post-partum haemorrhage following Caesarean section is rare [1]. The most common cause is retained placenta. One uncommon cause that shouldn't be disregarded is partial or total dehiscence of the hysterorrhaphy, which compromises the patient's prognosis and poses serious health risks. When hysterorrhaphy dehiscence does occur, the origin of the bleeding is probably related to erosion of the vessels at the incision angles [2]. Reported risk factors are nulliparity, diabetes, emergency surgery, infection, and incision placed too low in the uterine segment [4]. Nulliparity can be associated with atonic postpartum hemorrhage, which is a primary cause of secondary postpartum hemorrhage [5]. The only risk factor that could be identified in our patient was the emergency caesarean section. The history of subserosal dehiscence with a thin lower segment at the time of the previous caesarean section and the extension of the hysterotomy angles may explain the fragility of the caesarean.

Although the cause of delayed scar dehiscence is unknown, it could be caused by elements such as poor wound healing, infection or trauma to the area. It is important to check for scar defects in all women who have significant postpartum bleeding after a caesarean section surgery [6]. The typical presentation in the cases described is profuse bleeding, painless because it may not include uterine contractions [6], and recurring bleeding [5]. The onset of symptoms varies from 7 to 43 days postpartum [6]. Our patient also presented with profuse, painless, recurrent bleeding.

In cases of subsequent postpartum haemorrhage brought on by uterine scar dehiscence, pelvic ultrasonography may not be helpful in making a diagnosis. The only thing that a normal transvaginal ultrasound may detect in the scar area is fluid buildup or hematoma. The better way to detect dehiscence, though, may be using a 3D ultrasound [4]. In order to identify and pinpoint the cause of bleeding, other imaging techniques like MRI angiography, CT angiography, and catheter angiography may be more effective [2]. In our case, the diagnosis was made during surgery.

Secondary postpartum hemorrhage caused by uterine scar dehiscence is a rare but significant condition that must be treated right away. Conservative care, surgical management, and uterine artery embolization are all possibilities for treating subsequent postpartum bleeding caused by uterine scar dehiscence [2,4,7]. The treatment method chosen is determined by the intensity of the bleeding, the patient's clinical condition, and the degree of the dehiscence. Conservative care entails closely monitoring the patient's vital signs and blood loss, as well as bed rest and the delivery of uterotonics to promote uterine contraction. Conservative therapy is normally performed first, but in severe situations, it may not be beneficial in stopping bleeding [2,4]. Surgical intervention can be required if conservative therapy is ineffective at controlling bleeding [2]. Laparotomy followed by re-suturing of the scar or hysterectomy are two surgical treatments. Resuturing after debridement can be done for uterine wound dehiscence, but if the margins of the wound are infected or if there is a marked endomyometritis or intraabdominal sepsis, hysterectomy may be needed [8]. It has also been reported that uterine scar dehiscence following caesarean section, as revealed by ultrasonography, can be treated laparoscopically and vaginally [9]. Hysteroscopic resection of the fibrotic tissue or the technique proposed by Donnez et al. have been proposed for the repair of uterine scar dehiscence [10]. Another strategy is uterine artery embolization, a minimally invasive treatment in which embolic chemicals are injected into the uterine arteries in order to stop blood flow to the uterus [11]. In our case, due to the abundance of bleeding, the decision was made to perform a hysterectomy. The degree of the bleeding, the patient's hemodynamic stability, and the goal for future fertility will all influence the treatment option [2].

4. Conclusion

Secondary postpartum haemorrhage due to dehiscence of the uterine scar after caesarean section is a rare but serious complication because of its high morbidity. Diagnosis of this complication is often difficult in the absence of specific clinical and radiological signs. However, with the increasing frequency of caesarean sections, clinicians need to be aware of this complication.

In order to maximize the opportunities and chances of success of conservative treatment in the management of this condition, the diagnosis should be suspected at an early stage if non-specific signs and symptoms persist after caesarean section.

Ethical approval

The study is exempt from ethnical approval in our institution. Only the patient's authorization is required. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Funding

Not applicable.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declared they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Data availability

Materials described in the manuscript, including all relevant raw data, will be freely available to any scientist wishing to use them for non-commercial purposes.

References

- 1.Chainarong N., Deevongkij K., Petpichetchian C. Secondary postpartum hemorrhage: incidence, etiologies, and clinical courses in the setting of a high cesarean delivery rate. PloS One. 2022;17(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0264583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thakur G., Karmakar P., Gupta P., Saha S.C. Uterine scar dehiscence: a rare cause of life-threatening delayed secondary postpartum hemorrhage—a case report and literature review. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. India. 2021;71(6):629–632. doi: 10.1007/s13224-021-01493-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrab C., Mathew G., Kirwan A., Thomas A., et al. The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical Case Report (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84(1):226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sengupta Dhar R., Misra R. Postpartum uterine wound dehiscence leading to secondary PPH: unusual sequelae. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;2012:154685. doi: 10.1155/2012/154685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ende H.B., Lozada M.J., Chestnut D.H., Osmundson S.S., Walden R.L., Shotwell M.S., et al. Risk factors for atonic postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021;137(2):305–323. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwong F.L., Hamoodi I. Postnatal diagnosis of an occult uterine scar dehiscence after three uncomplicated vaginal births after caesarean section: a case report. Case Rep. Women’s Health. 2020;27 doi: 10.1016/j.crwh.2020.e00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bharatam K.K., Sivaraja P.K., Abineshwar N.J., Thiagarajan V., Thiagarajan D.A., Bodduluri S., et al. The tip of the iceberg: post caesarean wound dehiscence presenting as abdominal wound sepsis. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2015;9:69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sengupta Dhar R., Misra R. Postpartum uterine wound dehiscence leading to secondary PPH: unusual sequelae. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;2012:154685. doi: 10.1155/2012/154685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu Z, Li H, Zhang J. Uterine dehiscence in pregnant with previous caesarean delivery. Ann. Med. 53(1):1265–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.La Rosa M.F., McCarthy S., Richter C., Azodi M. Robotic repair of uterine dehiscence. JSLS. 2013;17(1):156–160. doi: 10.4293/108680812X13517013317996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumari P., Abraham A., Regi A., Navaneethan P. Successful management of secondary postpartum haemorrhage due to post caesarean wound dehiscence with uterine artery embolisation. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021;10(6):2534–2536. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Materials described in the manuscript, including all relevant raw data, will be freely available to any scientist wishing to use them for non-commercial purposes.