Abstract

Introduction and importance

Occult breast cancer (OBC) is defined as a clinically recognizable metastatic carcinoma arising from an undetectable primary breast tumor.

Presentation of case

We report in this work 2 cases of occult breast cancer treated at the Mohammed VI center of onco-gynecology of the CHU of Casablanca.

Clinical discussion

Significant advances in breast imaging have occurred since its description, decreasing its incidence. However current management is based upon old studies, with variable clinical, radiological and pathological definitions of OBC.

Conclusion

The introduction of better diagnostic techniques and more detailed pathology continue to impact the true incidence of OBC.

Summary

Carcinoma of unknown primary is an intriguing clinical phenomenon that is defined as biopsy-proven metastasis of a malignant tumor in the absence of an identifiable primary site after a complete clinical workup. Carcinoma of unknown primary accounts for approximately 3 to 5% of all cancer diagnoses, and consists of a heterogeneous group of tumors that have acquired the ability to metastasize before the development of a clinically evident primary lesion. Clinical and radiological examinations represent the first steps in the diagnostic algorithm for Carcinoma of unknown primary syndrome. However, histological and immunohistochemical analyses, together with evaluation by a multidisciplinary team and adequate therapy are essential for the diagnosis and treatment of Carcinoma of unknown primary syndrome of OBC. We report in this work 2 cases of occult breast cancer treated at the Mohammed VI center of onco-gynecology of the CHU of Casablanca; A multidisciplinary approach including surgery, radiotherapy, hormonal and biological therapy was implemented. Currently, 10 month after the first presentation, the two patient received ipsilateral breast radiotherapy and sequential adjuvant chemotherapy followed by hormone therapy. Evolution was marked by good control.

Keywords: Occult primary breast cancer, Carcinoma of unknown primary, Axillary metastasis

Highlights

-

•

proven metastasis of a malignant tumor in the absence of an identifiable primary site after a complete clinical workup

-

•

clinically recognizable metastatic carcinoma arising from an undetectable primary breast tumor

-

•

Occult primary breast cancer is a very rare entity of breast cancer

-

•

Breast MRI is a consolidated indication for the search for an occult primary tumor of the breast when the first level examinations have not revealed any suspicious lesions

1. Introduction

Occult breast cancer (OBC) was first described by Halsted in 1907 and is defined as clinically recognizable metastatic cancer arising from an undetectable primary breast tumor [1]. It accounts for 0.3–1 % of all breast cancers [2], with axillary and cervical lymph node metastases being the first presentation of a CUP syndrome [3]. Despite the limited amount of information regarding the management and outcomes of this rare disease, results from several studies have suggested that OBC has a similar or more favorable survival rate compared to non-occult stage II breast cancer. [4,5] However, even with the possibility of modern investigative techniques, such as mammography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), OBC still a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Furthermore, there is no consensus regarding the prognostic factors of OBC [6]. We conducted this article to assess the management and prognostic factors in 2 patients with Occult breast cancer at the Mohammed VI center of onco-gynecology of the CHU of Casablanca.

This case report was prepared in accordance with the SCARE guidelines.

2. Observation

2.1. 1st case

A 52 years old woman with no particular pathological history or toxic habit, who consults for a left axillary lymphadenopathy. The clinical examination finds a mobile left axillary ADP in relation to the 2 planes of 2 cm; the ultrasound mammography does not reveal any abnormality in the breasts apart from necrotic left axillary lymphadenopathy of 2 cm on average classified ACR4 (Fig. 1), An adenectomy was performed has shown Lymph node metastasis of a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, first evoking a breast origin. The immunohistochemical study found Over-expression of: ER (estrogen receptor) at 50 %, and anti-Cytokeratin (CK7 and CK20); The tumor does not express: Anti mammoglobin or Anti napsin A or Anti P 40. This IHC profile confirms the primary mammary origin.

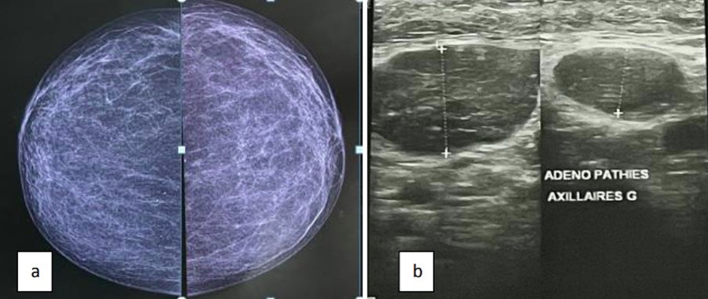

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound (b) mammography (a) showing axillary lymphadenopathy without glandular abnormality

On breast MRI Infiltration of axillary fat enhanced by PDC, post-operative appearance, associated with mediastinal and right pulmonary hilar lymphadenopathy of variable size, without abnormality in the mammary gland (Fig. 2). The thoraco-abdo-pelvein CT shows mediastinal ADPs at Barety's compartment measuring 16*18 mm and 22*34 mm respectively With right hilar ADPs measuring 20*22 m and 21*19 mm. Left axillary fat infiltration measuring 22*25 mm (Fig. 1). The patient underwent supero-external quadrantectomy in our department, a decision taken at the multidisciplinary consultation meeting (RCP). The anatomo-pathological result: absence of malignancy.

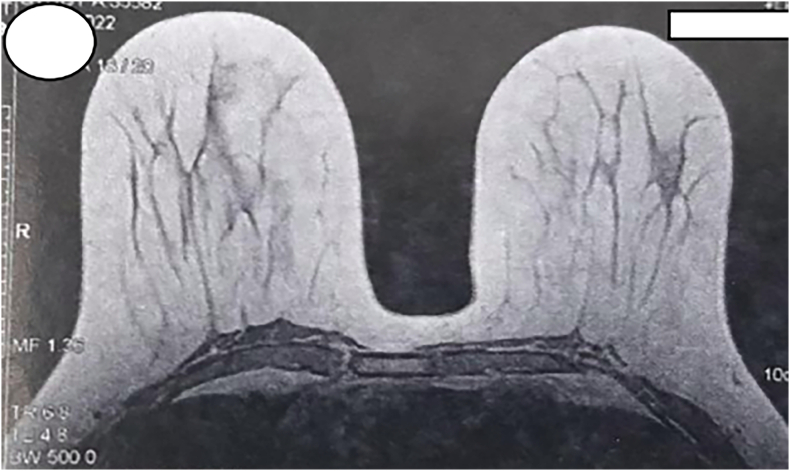

Fig. 2.

Breast MRI showing no radiological abnormalities

2.2. 2nd case

A 51 years old woman, with no particular pathological history, who consults for a left axillary adenopathy of 2 cm mobile in relation to the 2 planes. Ultrasound mammography does not find any radiological breast abnormalities apart from five contiguous hypoechoic left axillary adenopathies without visible hilum of 8 mm, 10 mm, 10 mm, 17 mm and 27 mm of small diameter, classified ACR0 without breast abnormality (Fig. 3). objective breast MRI of oval left axillary adenomegaly, with the largest preserved architecture, measures 20*12 mm. (Fig. 4). An adenectomy reveals a lymph node location of a poorly differentiated and invasive carcinoma, including IHC: RE: 0 %, PR: 0 %, Ki67 at 50 % Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-2: 3+. Over-expression of CK7 and GATA3. And absence of expression of CK20 or Mammoglobin. the IHC profile suggests a breast origin. The patient had a supero-external quadrantectomy following the decision of the CPR, the anatomo-pathological result: absence of malignancy. A PETSCAN with 18F-FDG was performed showing a diffuse and heterogeneous breast hyper metabolism in the upper quadrants without an individualizable frank focus of postoperative appearance and a hyper metabolic ADP under the right angulo-mandibular of a non-specific appearance (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Ultrasound (b) mammography (a) showing axillary lymphadenopathy without glandular abnormality

Fig. 4.

Breast MRI showing no radiological abnormalities

Fig. 5.

18F-FDG PETSCAN showing diffuse breast hypermetabolism

The two patient received ipsilateral breast radiotherapy and sequential adjuvant chemotherapy (anthracycline - taxane) followed by hormone therapy. Evolution was marked by good control after a median follow up of 10 months.

3. Discussion

Occult primary breast cancer is a very rare entity of breast cancer, it represents less than 1 % of all breast cancers, and is defined as a carcinoma that has metastasized to the armpit in the absence radiological or physical signs of disease in the breast [2]. It presents a real challenge for diagnosis and therapeutic management in the absence of a consensual attitude due to the lack of high quality randomized clinical trials. Its pathophysiology is poorly understood. The management is essentially based on the clinical examination: a complete questioning with the family history of cancer and the personal history of benign tumor The senological clinical examination, pelvic examinations [7]. Malignant neoplasms of other organs known to metastasize to the axillary nodes include melanomas and carcinomas of lung, thyroid, stomach, colon, rectum, pancreas and ovaries through lymphatic drainage [8]. However, these metastases are rarely the first signs of disease, that's why a large number of para-clinical investigations are necessary for the differential diagnosis; as first intention are ultrasound mammography, thoraco-abdominopelvic computed tomography. Breast MRI is a consolidated indication for the search for an occult primary tumor of the breast when the first level examinations have not revealed any suspicious lesions (sensitivity of 88 to 100 %) [9]. The realization of biopsies with anatomo-pathological and IHC study provides a diagnostic orientation in about 90 % of undifferentiated malignant tumors. The interest of PET-CT and endoscopic explorations is discussed. PET is indicated for the diagnosis of the primary tumor in these difficult cases, especially in women with radio-dense breasts [10]. The interest of the immunohistochemical study by looking for estrogen and progesterone expression which suggest breast cancer, but ER/PR negative does not exclude the diagnosis, it should not be forgotten that other carcinomas (colon, ovarian, endometrial, kidney and melanoma cancer) may exhibit detectable ER/PR expression [11]. Kaufmann et al. investigated the possibility of differentiating metastatic breast carcinomas from other metastatic adenocarcinomas by immunohistochemistry. The study showed the sensitivity and specificity of ER expression in breast carcinoma compared to all other carcinomas were 0.63 and 0.95. They also reported the utility of crude cystic disease fluid protein 15 (GCDFP-15; also known as BRST-2), which is an apocrine differentiation marker. The sensitivity and specificity of GCDFP-15 expression were 0.98 and 0.62, respectively. The GCDFP-15 and/or ER or PR combination had a sensitivity of 0.83 and a specificity of 0.93 for breast carcinomas [12]. Mammaglobin antibody is another sensitive marker of breast carcinoma. Bhargava et al. recently reported that the sensitivity of mammaglobin is better than that of GCDFP-15, but lacks the specificity of GCDFP-15 [11]. Regarding therapeutic management, there is no clear consensus on the optimal treatment of occult breast cancer. The classic therapy of choice was radical mastectomy. Recent studies have shown no significant difference between mastectomy and more conservative treatments, such as limited resection (blind upper lateral quadrantectomy) and/or radiotherapy. The choice of a treatment regimen remains controversial, the literature does not clearly support the mass use of one or the other [13] A survey of the preferred therapeutic strategy of 1837 breast surgeons (American Society of Breast Surgeons, 2005) showed that: 43 % preferred radio-chemotherapy, 37 % breast surgery, the others opted for surveillance. Monitoring of the affected breast not being an appropriate choice, Shannon and al noted a higher rate of local recurrence in patients who received no radiological treatment compared to those who did (69 % versus 12.5 %) [14]. Ellerbroek et al. reported that detection of a primary focus within 5 years was higher in patients who did not receive radiation therapy than in those who did (57 % versus 17 %, respectively), this approach is not acceptable to most breast surgeons [15]. Surgery remains the intervention most widely applied in clinical practice, with the possibility of detecting a main focus in 40 % to 80 % of cases on mastectomy. Blanchard and Farley studied 35 patients with OBC [16], and observed that overall survival in patients who had a mastectomy (72.7 %) was superior to those who had breast-conserving surgery; the recurrence rate was higher low (36 % versus 81 %). It is therefore necessary to add radio-chemotherapy after local therapy for optimal management with improved survival in patients who have undergone axillary dissection compared to those who have had an axillary biopsy. Axillary radiotherapy after surgery is essential to reduce the risk of local axillary recurrence [17]. Studies have confirmed that it is an appropriate alternative to mastectomy. Exclusive radiotherapy of the breast is a therapeutic option little studied in the literature. However, it appears to be an interesting alternative to radical mastectomy according to the retrospective study by Vlastos et al. The irradiation field includes the affected breast in case of breast-conserving surgery, while there is not much information on irradiation of the chest wall after mastectomy. Knowing that breast radiation therapy can lead to breast fibrosis and distortion of the shape of the breasts, which may betray the initial objective of breast preservation [18]. Authors recommend carrying out a minimal locoregional treatment when possible, which would improve the overall survival and without recurrence of the patients, there is no significant difference between mastectomy and parietal radiotherapy alone, in terms of overall survival at 5 years or disease-free survival. However, there are no prospective studies on the subject [19].

4. Conclusion

Management of the large group of patients who do not fit into any currently identified treatment subset continues to be an important concern. Axillary dissection with breast conservation and ipsilateral breast radiotherapy seems to be a good treatment option and can be recommended to improve local control in addition to aesthetic results. Although some researchers suggest careful monitoring without further treatment, other studies have shown that the prognosis is better for women undergoing either radiation therapy or mastectomy, with a slight survival advantage for patients who have undergone mastectomy.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Ethical approval was waived by the authors institution

Ethics statement

CHU Ibn Roched

Sources of funding

None.

Ethical approval

I declare on my honor that the ethical approval has been exempted by my establishment.

Consent

Written informed consent for publication of their clinical details and/or clinical images was obtained from the patients. And identities were preserved.

Author contribution

BENCHRIFI YOUNESS: correction the paper

CHERKAOUI AMAL: writing the paper

TOSSI SARA: writing the paper

Benhassou Mustapha: correction of the paper

Ennachit Simohamed: correction of the paper

Kerroumi Mohamed: correction of the paper

Guarantor

CHERKAOUI AMAL

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare having no conflicts of interest for this article.

References

- 1.Halsted W.S.I. The results of radical operations for the cure of carcinoma of the breast. Ann. Surg. 1907 Jul;46(1):1–19. doi: 10.1097/00000658-190707000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbieria Erika, Annunziata Chiara, Anghelonea Pasqualina, Gentilea Damiano, La Rajaa Carlotta, Bottinia Alberto, Tinterria Corrado. Metastases from occult breast cancer: a case report of carcinoma of unknown primary syndrome. Case Rep. Oncol. 2020;13:1158–1163. doi: 10.1159/000510001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen P.P., Occult Kimmel M. Breast carcinoma presenting with axillary lymph node metastases: a follow-up study of 48 patients. Hum. Pathol. 1990;21:518–523. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90008-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker G.V., Smith G.L., Perkins G.H., Oh J.L., Woodward W., Yu T.K., et al. Population-based analysis of occult primary breast cancer with axillary lymph node metastasis. Cancer. 2010 Sep;116(17):4000–4006. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montagna E., Bagnardi V., Rotmensz N., et al. Immunohistochemically defined subtypes and outcome in occult breast carcinoma with axillary presentation. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011;129:867–875. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1697-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krämer A., Hübner G., Schneeweiss A., Folprecht G., Neben K. Carcinoma of unknown primary – an orphan disease? Breast Care (Basel) 2008;3(3):164–170. doi: 10.1159/000136001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouldamer L., et al. Axillary lymph node metastases from unknown primary: a French multicentre study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. avr. 2018;223:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abe H., Naitoh H., Umeda T., Shiomi H., Tani T., Kodama M., Okabe H. Occult breast cancer presenting axillary nodal metastasis: a case report. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000;30(4):185–187. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyd047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stomper Paul C., Waddell Brad E., Edge Stephen B., Klippenstein Donald L. Breast MRI in the evaluation of patients with occult primary breast carcinoma. The Breast Journal. 05 January 2002;5(4):230–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.1999.99004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melania Costantini et al., « Axillary Nodal Metastases from Carcinoma of Unknown Primary (CUPAx): Role of ContrastEnhanced Spectral Mammography (CESM) in Detecting Occult Breast Cancer - PubMed ». [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Bhatia S.K., Saclarides T.J., Witt T.R., Bonomi P.D., Anderson K.M., Economou S.G. Hormone receptor studies in axillary metastases from occult breast cancers. Cancer. mars 1987;59(6):1170–1172. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870315)59:6<1170::aid-cncr2820590623>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaufmann O., Deidesheimer T., Muehlenberg M., Deicke P., Dietel M. Immunohistochemical differentiation of metastatic breast carcinomas from metastatic adenocarcinomas of other common primary sites. Histopathology. 1996;29(3):233–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1996.tb01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massard C., Rochaix P., Ilié M. 2016. Cancer de primitif inconnu (CAPI): un nouvel espoir? p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shannon C., Smith I.E. Breast cancer in adolescents and young women. Eur. J. Cancer. 2003;39(18) doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00669-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellerbroek N., et al. Treatment of patients with isolated axillary nodal metastases from an occult primary carcinoma consistent with breast origin. 1 October 1990;66(7):1461–1467. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901001)66:7<1461::aid-cncr2820660704>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu, et al. Diagnoses and therapy of occult breast cancer: a systematic review. J. Mol. Biomark Diagn. 2016 S:2. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vlastos G., et al. Feasibility of breast preservation in the treatment of occult primary carcinoma presenting with axillary metastases. Ann. Surg. Oncol. juin 2001;8(5):425–431. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0425-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barton S.R., Smith I.E., Kirby A.M., Ashley S., Walsh G., Parton M. The role of ipsilateral breast radiotherapy in management of occult primary breast cancer presenting as axillary lymphadenopathy. Eur. J. Cancer. sept. 2011;47(14):2099–2106. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.F. Couder et al, « Envahissement ganglionnaire axillaire sans tumeur primitive mammaire retrouvée: à propos de 16 cas issus d'une cohorte de 7770 patientes. [DOI] [PubMed]