Abstract

Background:

Increasing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use is a critical part of ending the HIV epidemic. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, many PrEP services transitioned to a telehealth model (telePrEP). This report evaluates the effect of COVID-19 and the addition of telePrEP on delivery of PrEP services at the Denver Sexual Health Clinic (DSHC), a regional sexual health clinic in Denver, CO.

Methods:

Prior to COVID-19, DSHC PrEP services were offered exclusively in-clinic. In response to the pandemic, after March 15, 2020, most PrEP initiation and follow up visits were converted to telePrEP. A retrospective analysis of DSHC PrEP visits compared pre-COVID-19 (September 1, 2019 to March 15, 2020) to post-COVID-19 (March 16, 2020 to September 30, 2020) visit volume, demographics, and outcomes.

Results:

The DSHC completed 689 PrEP visits pre-COVID-19 and maintained 96.8% (n=667) of this volume post-COVID-19. There were no differences in client demographics between pre-COVID-19 (n=341) and post-COVID-19 PrEP start visits (n=283) or between post-COVID-19 in-clinic (n=140) vs telePrEP start visits (n=143). There were no differences in 3–4-month retention rates pre-COVID-19 (n=17/43) and post-COVID-19 (n=21/43) (P=0.52) or between in-clinic (n=12/21) and telePrEP clients (n=9/22) in the post-COVID-19 window (P=0.37). Also, there were no significant differences in lab completion rates between in-clinic (n=140/140) and telePrEP clients (n=138/143) (P=0.06) and prescription fill rates between in-clinic (n=115/136) and telePrEP clients (n=116/135) in the post-COVID-19 window (P=0.86).

Conclusions:

Implementation of TelePrEP enabled the DSHC to sustain PrEP services during the COVID-19 pandemic without significant differences in demographics, engagement, or retention in PrEP services.

Keywords: HIV, Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, Telehealth, COVID-19 pandemic, telePrEP

Short Summary:

Implementation of telehealth HIV PrEP delivery enabled the Denver Sexual Health Clinic to sustain PrEP services during the COVID-19 pandemic without significant differences in demographics, engagement, or retention in PrEP services.

INTRODUCTION

Over 1.1 million people in the United States are living with HIV and almost 37,000 people are newly diagnosed with HIV every year.1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends oral or injectable HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for prevention of HIV. Although PrEP has been shown to be safe and effective at reducing the risk of acquiring HIV, in 2018, only 18% of the estimated 1.2 million people with an indication for PrEP were receiving it.2 Of those who receive a prescription for PrEP, estimates of real-world retention rates vary greatly by study and time frame but range from (15% - 76%) and are lower in community-based health centers.3–9 Innovative approaches aimed at increasing PrEP use and retention are needed.

Multiple barriers exist to expanding PrEP use and retention including limited access to PrEP services due to geographic isolation and stigma around HIV risk factors.10,11 These barriers were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Access to HIV prevention services were disrupted by mandatory lockdowns, social distancing, and the reassignment of public health personnel from sexual health services to the COVID-19 pandemic response.12,13 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, several pilot studies demonstrated the feasibility of using telehealth for delivery of PrEP services (telePrEP) to overcome delivery barriers. 14–16 However, conclusions from these studies were limited due to small sample sizes or the unique setting of the programs.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, public health guidance encouraged traditionally in-clinic PrEP delivery programs to rapidly adapt and offer telehealth services to ensure continuity of PrEP care.17 The development of PrEP telehealth (telePrEP) was enabled by changes to telehealth regulations and payer reimbursement models.18 Several small reports observed significant disruptions in PrEP delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic.12,13 However, there is limited information on the success of programs that were able to develop telePrEP services during the pandemic. Understanding the impact of telePrEP implementation in established, large PrEP clinics in response to COVID-19, will help inform the potential successes and barriers for this PrEP delivery method as the U.S. moves forward in advancing HIV prevention interventions.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Denver Sexual Health Clinic (DSHC) rapidly established a telePrEP delivery model to complement traditional in-clinic PrEP. TelePrEP services were offered to improve access to PrEP services in the setting of mandatory lockdowns and social distancing. The aims of this study are to describe the response of the DSHC PrEP program to the COVID-19 pandemic and evaluate the efficacy of telePrEP in supporting a diverse population in PrEP engagement and retention to PrEP services by comparing PrEP initiation and follow-up visits before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Period

In mid-March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the resultant mandatory stay-at-home order, the DSHC rapidly converted from only offering traditional in-clinic appointments for PrEP services to offering in-clinic or telePrEP options. In order to compare PrEP program outcomes before and after the introduction of telePrEP and the onset of COVID-19, a retrospective chart review and analysis was performed for all PrEP visits from September 1, 2019 to March 15, 2020 (pre-COVID-19) and from March 16, 2020 to September 31, 2020 (post-COVID-19). The location of PrEP visit (in-clinic vs. telePrEP) and type of PrEP visit (start or follow-up) was collected. Additionally, client demographic and outcome data (laboratory completion rate, prescription fill rate, and 3–4 month follow up rate) were collected from all in-clinic PrEP start visits pre-COVID-19 and all in-clinic or telePrEP start visits post-COVID-19 when the DSHC transitioned to offering telePrEP. In the analysis of client demographics and outcomes, clients with multiple PrEP start visits within the study period, only the first PrEP start visit in each study window was analyzed.

PrEP Program

All clients who are eligible for PrEP can initiate PrEP at DSHC, but DSHC only provides continuity PrEP services including follow-up visits to persons without insurance who enroll in the state PrEP assistance program, the Public Health Intervention Program (PHIP). PHIP clients follow-up at DSHC every three months by telePrEP or in-clinic visits. Clients who have private insurance or are not eligible for the PHIP program are referred to a primary care provider for ongoing PrEP services. All PrEP clients receive PrEP navigation services.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the DSHC only offered in-clinic visits for PrEP services. Following mid-March 2020 and the start of COVID-19 pandemic related restrictions, clients were offered telePrEP visits for PrEP initiation or follow-up unless indications for an in-clinic evaluation were met. Indications for an in-clinic evaluation included: symptoms of a sexually transmitted infection (STI), exposure to an STI, STI follow-up, or other services requiring in-clinic management. Clients who had a telePrEP appointment were provided PrEP services either by telephone or web-based video platform. For telePrEP clients, lab-only visits were planned during the telePrEP visit and had to be completed prior to prescription of PrEP medications. Following laboratory test completion, PrEP prescriptions were sent to the client’s pharmacy of choice.

Measures

PrEP visits were extracted from the DSHC electronic medical record (EMR) system and then classified through chart review as an in-clinic or telePrEP start (not currently on PrEP medication) or follow-up visit (currently on PrEP medication) according to provider documentation. Multiple PrEP start visits, or “restart” visits occurred when providers documented the client had not been taking PrEP medication for 1 month or longer. Client demographic factors including age, sex assigned at birth, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation were also extracted from the EMR. Sexual behavior was used as a correlate of sexual orientation and was determined by client -reported sexual contact within the last 12 months and was categorized as men who have sex with men (MSM), men who have sex with men and women (MSMW), men who have sex with women (MSW), women who have sex with men (WSM), and women who have sex with men and women (WSMW). Other demographic variables were categorized as listed in Table 1. Laboratory completion was defined as completion of ordered labs within two weeks of a PrEP visit.

Table 1.

Client demographics for PrEP starts by COVID-19 pandemic window and visit type

| Demographics | Total PrEP Start Visits N=624 | Pre-COVID-19 PrEP Start N=341 | Post-COVID-19 PrEP Start N=283 | p valuea | Post-COVID-19 PrEP Start Visits | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| In-Clinic N=140 | TelePrEP N=143 | p valuea | |||||

| Age (n, %) | 0.95 | 0.34 | |||||

| 18–29 | 367 (58.9) | 199 (58.4) | 168 (59.4) | 89 (63.6) | 79 (55.2) | ||

| 30–49 | 240 (38.5) | 133 (39.0) | 107 (37.8) | 48 (34.3) | 59 (41.3) | ||

| >49 | 17 (2.7) | 9 (2.6) | 8 (2.8) | 3 (2.1) | 5 (3.5) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Sex assigned at birth (n, %) | 0.05 | 0.54 | |||||

| Male | 589 (94.4) | 317 (93.0) | 272 (96.1) | 134 (95.7) | 138 (96.5) | ||

| Female | 34 (5.4) | 24 (7.0) | 10 (3.5) | 6 (4.3) | 4 (2.8) | ||

| Unknown/missing | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Sexual Orientation | 0.25 | 0.67 | |||||

| Men who have sex with men | 400 (64.1) | 223 (65.4) | 177 (62.5) | 107 (76.4) | 70 (49.0) | ||

| Men who have sex with men and women | 69 (11.1) | 40 (11.7) | 29 (10.3) | 21 (14.8) | 8 (1.4) | ||

| Women who have sex with men | 21 (3.4) | 14 (4.1) | 7 (2.5) | 5 (3.6) | 2 (1.4) | ||

| Men who have sex with women | 12 (1.9) | 10 (2.9) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | ||

| Women who have sex with men and women | 5 (0.8) | 4 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Unknown/missing | 117 (18.8) | 50 (14.6) | 67 (23.7) | 5 (3.6) | 62 (43.4) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Race/Ethnicity (n, %) | 0.79 | 0.19 | |||||

| White/Non-Hispanic | 309 (49.5) | 163 (47.8) | 146 (51.6) | 75 (53.5) | 71 (49.7) | ||

| Hispanic or Latino (all races) | 222 (35.6) | 124 (36.6) | 98 (34.6) | 47 (33.6) | 51 (35.7) | ||

| Black/African American/Non-Hispanic | 46 (7.4) | 28 (8.2) | 18 (6.4) | 12 (8.6) | 6 (4.2) | ||

| Asian/Non-Hispanic | 17 (2.7) | 11 (3.2) | 6 (2.1) | 2 (1.4) | 4 (2.8) | ||

| Multiracial/Other | 23 (3.7) | 12 (3.5) | 11 (3.9) | 2 (1.4) | 9 (6.3) | ||

| Unknown/missing | 7 (1.1) | 3 (0.9) | 4 (1.4) | 2 (1.4) | 2 (1.4) | ||

Abbreviations: PrEP = HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis; telePrEP = PrEP services using telehealth.

p-value represents comparison of between pre vs. post COVID groups or in-clinic vs. telehealth groups using Fisher’s exact test excluding missing/unknown

Prescription dispense was defined as documentation of filling PrEP medications within two weeks of a PrEP visit. Internal and external pharmacy prescription dispense data was available through the DSHC EMR. Outside pharmacies utilized Allscripts® for prescription dispense data. Chart review was performed on records with no data in the dispense fields to confirm there was no evidence of a PrEP prescription being filled. Twenty clients either had hard-copy printed prescriptions or conflicting information on prescription dispenses in the EMR and were excluded from the prescription dispense analysis.

To assess continued engagement in DSHC PrEP services, retention at 3–4 months was defined as a follow-up encounter for PrEP services between 2.5 and 4.5 months after a PrEP start in clients who were eligible for ongoing subsidized PrEP services (PHIP clients). Only clients who enrolled in PHIP were included for follow-up encounter analysis as clients with private insurance and those who did not enroll in PHIP were referred to a primary care provider for ongoing PrEP care.

Data Analysis

Data and statistical analysis were performed using SAS® statistical software (version 7.15). Frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical and ordinal variables. Medians and interquartile ranges were presented for discrete variables. Differences in client demographics, lab completion, prescription dispense, and follow-up encounters between client groups (pre vs. post COVID-19 pandemic and telePrEP vs. in-clinic visits post-COVID-19) were compared using the Fisher’s exact test. All statistical tests were performed as 2-sided tests with a level of significance of P<0.05.

Human Subjects

This work was approved for quality improvement and program evaluation by the Quality Improvement Review Committee at the Office of Research at Denver Health (Denver, CO).

RESULTS

PrEP Appointment Types and Clinic Volume

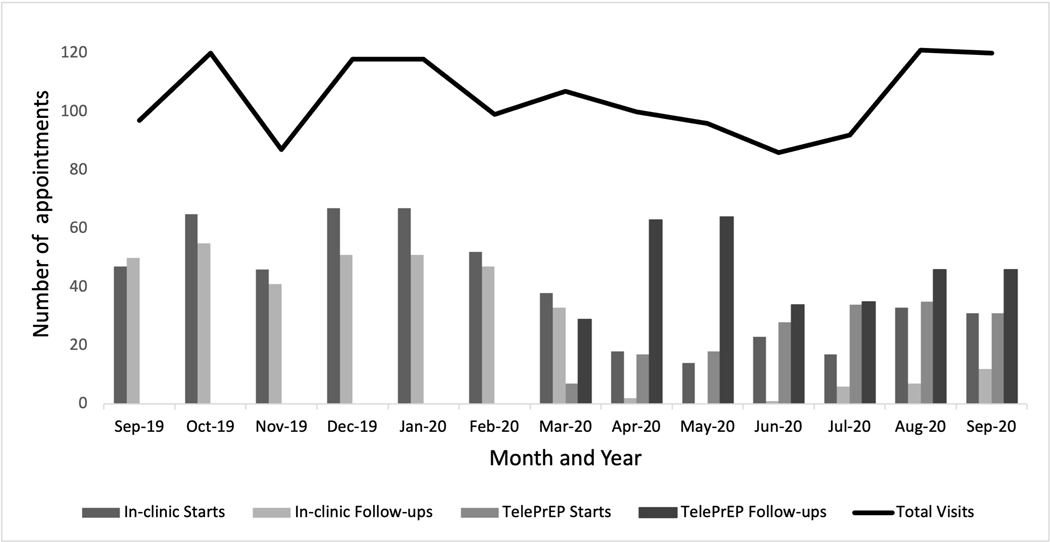

The monthly PrEP delivery volumes and appointment types at DSHC are presented in Figure 1 for the study period. Overall, DSHC was able to maintain 96.8% of the total PrEP visit volume in the post-COVID-19 window (n=667) compared to the pre-COVID-19 window (n=689). PrEP start visits decreased 12.9% post-COVID-19 (n=318) compared to pre-COVID-19 (n=365). There was an 7.7% increase in PrEP follow-up visit volume post-COVID-19 (n=349) compared to pre-COVID-19 (n=324). In the post-COVID-19 timeframe, 52.8% (168/318) of PrEP start visits and 90.5% (316/349) of PrEP follow-up visits occurred via telePrEP.

Figure 1.

PrEP appointment types and total volume by month, DSHC, September 2019 – September 2020. Abbreviations: PrEP = HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis; DSHC = Denver Sexual Health Clinic; telePrEP = PrEP services using telehealth.

Client Demographics

The first PrEP start visit for a client was selected in each timeframe window (pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19) to compare characteristics and outcomes. There were 624 first PrEP start visits among 594 unique clients across the two study timeframe windows with 30 clients who had a PrEP start visit in both the pre- and post-COVID-19 windows. Of the 624 PrEP start visits during the entire study period, 58.9% were with clients <30 years old, 94.4% were male, 49.5% were White/Non-Hispanic, and 78.9% identified as MSM (excluding unknown/missing responses [n=117, 18.8%]). Client demographics were compared between clients who started PrEP in the pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 windows (Table 1). There were no significant differences in age, sex assigned at birth, race/ethnicity, or sexual orientation between clients starting PrEP in the pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 windows. Client demographics were also compared between clients in the post-COVID-19 window who started PrEP with an in-clinic visit compared to a telePrEP visit when both these services were offered. There were no significant differences in age, sex assigned at birth, race/ethnicity, or sexual orientation, between these groups.

Outcomes of PrEP Initiation

Successful laboratory completion and prescription dispenses for clients who started PrEP in the pre-COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 windows were compared (Table 2). Although there was a small but significant difference in successful laboratory completion between clients starting PrEP pre-COVID-19 (100%; n=341) compared to clients post-COVID-19, 98.2% (278/283) of clients starting PrEP post-COVID-19 completed their labs as ordered (p=0.02). Notably, during the pre-COVID-19 window, 92.5% (308/333) of clients starting PrEP had documentation of a prescription dispense compared to 85.2% (231/271) of clients starting PrEP in the post-COVID-19 window (p = 0.005.) There were no significant differences in 3–4-month follow-up appointment completion among PHIP clients between pre-COVID-19 (39.5%) and post-COVID-19 windows (48.8%) (p=0.52).

Table 2.

Outcomes of PrEP start visits by COVID-19 pandemic window and visit type

| PrEP start visit outcomes | Pre-COVID-19 PrEP Start Visits | Post-COVID-19 PrEP Start Visits | p valuea | Post-COVID19 PrEP Start Visits | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| In-clinic PrEP | TelePrEP | p valuea | ||||

| Laboratory completion (n, %) | N=341 | N=283 | N=140 | N=143 | ||

| Yes | 341 (100.0) | 278 (98.2) | 0.02 | 140 (100.0) | 138 (96.5) | 0.06 |

| No | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (3.5) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Prescription filledb (n, %) | N=333 | N=271 | N=136 | N=135 | ||

| Yes | 308 (92.5) | 231 (85.2) | 0.005 | 115 (84.6) | 116 (85.9) | 0.86 |

| No | 25 (7.5) | 40 (14.8) | 21 (15.4) | 19 (14.1) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Follow-up visit at 3–4 monthsc (n, %) | N=43 | N=43 | N=21 | N=22 | ||

| Yes | 17 (39.5) | 21 (48.8) | 0.52 | 12 (57.1) | 9 (40.9) | 0.37 |

| No | 26 (60.5) | 22 (51.2) | 9 (42.9) | 13 (59.1) | ||

Abbreviations: PrEP = HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis; DSHC = Denver Sexual Health Clinic; telePrEP = PrEP services using telehealth.

A difference was deemed to be statistically significant if P<0.05. For clarity, statistically significant findings have been presented in boldface.

Prescription dispense status was not available for 20 clients (8 pre-COVID 19 and 12 post-COVID 19)

Follow-up visits at 3–4 months only included clients eligible for 3–4-month follow up visit through PHIP.

During the post-COVID-19 window, there was no significant difference in successful laboratory completion between clients starting PrEP by telePrEP compared to in-clinic visits, and 96.5% (138/143) of clients using telePrEP completed their labs as ordered (Table 2). During the post-COVID-19 window, there were no significant differences in successful prescription dispense or 3–4-month follow up appointment completion between clients using telePrEP compared to in-clinic visits.

DISCUSSION

With up to 37,000 new HIV diagnoses across the United States each year, increasing PrEP use is a critical part of addressing and ending the HIV epidemic.1,19 The COVID-19 pandemic forced rapid, substantial, and far-reaching changes to HIV prevention services including PrEP. The results of this study demonstrate that telePrEP enabled the DSHC to sustain PrEP delivery services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Among people starting PrEP pre and post COVID-19, there was no significant difference in age, race or ethnicity although there was a trend toward lower rates of women starting PrEP post-COVID-19 and institution of telePrEP will require further assessment with a larger sample size.

Telehealth is defined by the United States Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA) as “the use of electronic information and telecommunication technologies to support long-distance clinical health care, client, and professional health-related education, health administration, and public health” and includes a number of different modalities and program types.20 Telehealth has demonstrated an ability to increase access to care and the Infectious Disease Society of America supports the use of telehealth services such as telePreP to provide timely infectious disease care to resource-limited populations.21 The results of this study are in line with pre-COVID-19 studies demonstrating high acceptance, adherence, and satisfaction with telePrEP. Specifically, two recent studies demonstrated the feasibility of using telePrEP services in a small group of MSM.22,23 A larger study involving a regional collaborative between public health professionals, academics, and pharmacists in Iowa demonstrated similar acceptance and satisfaction with a video-conferencing based telePrEP program and showed 96% adherence to indicated laboratory monitoring.16

However, there is concern that a transition to telehealth services for HIV prevention may create a “digital divide”, defined as unequal access to or ability to engage in care using technological means, which may exacerbate inequities in access to PrEP care due to disparities in social determinants of health.24 Previous research has linked successful telehealth use to age, race, ethnicity, gender, income, education level, housing stability, mental health, and substance use.24,25 Furthermore, there are concerns that limitations in technology, technical literacy, connectivity, and personal privacy will negatively impact access to telehealth.24 Nonetheless in this study, the addition of telePrEP services did not result in significant differences in client demographics between those initiating PrEP in clinic or via telehealth.

This study had several strengths. The study population was larger than most other reports of telePrEP programs administered through public health clinics.15,16,22 This study presented information on PrEP initiation and engagement, and finally, data presented addressed a literature gap regarding the impact of COVID-19 on PrEP services and the use of telePrEP to overcome this impact.

This study also had several limitations. Clients were only offered telePrEP services at scheduling if they reported no issues that would require in-clinic evaluation. This may result in significant differences between in-clinic and telePrEP populations which make comparison between these groups challenging. However, this is the real-world scenario for most HIV prevention services as in-clinic visits will always be necessary for certain individuals with clinical concerns requiring physical evaluation. Our program did not offer online PrEP services or home lab testing which may further address issues of geographic isolation and stigma. Further study is needed to determine if home testing options could improve reach of services, racial disparities in PrEP uptake or PrEP retention. Also, this study was done at a single regional sexual health clinic in Denver, Colorado, and may not be generalizable to other areas or clinical settings. Furthermore, disparities in care related to telePrEP access may not have been discovered in this study due to the relatively small size of the DSHC PrEP program, and further studies evaluating potential disparities are warranted. Additionally, a large proportion of clients did not have sexual orientation information available. This study was not able to evaluate other important social determinants of health and risk factors which should be evaluated in future work including education level, income, substance abuse and history of STIs. Finally, the number of clients eligible for a 3–4-month follow up was small and those who did not have a follow up encounter may have established care with another provider resulting in lower measurements of PrEP engagement in care.

The findings of this study have several important implications for increasing PrEP use and retention. First, although this study demonstrates a modest decrease in laboratory completion and medication dispensed for PrEP in clients in the post-COVID-19 window, there was no difference between clients receiving in-clinic or telePrEP services. This study adds to the literature demonstrating that telePrEP is a useful model to support PrEP use and may help overcome barriers to accessing PrEP services. Additionally, even in populations who don’t experience significant barriers to accessing PrEP, telePrEP may be a more convenient and preferred modality for PrEP services due to reduced time demands for telehealth visits, but this was not evaluated in this study. Supporting permanent changes to telehealth infrastructure such as regulations and payer reimbursement models, which accelerated the rapid expansion of telePreP programs during the COVID-19 pandemic, should be considered to enable the sustainability of telePrEP programs. Finally, telePrEP services should be continually evaluated for their potential to exacerbate a “digital divide”, which may intensify existing inequities in PrEP care.

Despite the many challenges to healthcare delivery in 2020, the addition of telePrEP enabled the DSHC to sustain PrEP delivery services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Factors contributing to the successes of the DSHC program included availability of experienced PrEP providers who could solely focus on the telePrEP program post-COVID; ability to re-assign clerical staff to provide support to the telePrEP providers; pharmacy medication delivery options; and capacity of the electronic health record to accommodate web-based visits. Barriers included high learning curve for providers learning to use new software for web-based visits, which contributed to higher use of telephone visits. Additional barriers included clients finding private location to complete the visit; need to convert a telephone visit to an in-clinic visit once clinical concerns were identified during the visit; clients having strong internet connection and download software or web browser needed to complete web-based visits. Despite these barriers, the implementation of telePrEP services compared to in-clinic services did not result in significant disparities in access to care by the other client demographics measured. In addition, completion of labs for telePrEP clients was high, and although prescription fills declined in the post-COVID-19 timeframe, it did not differ significantly between clients starting PrEP in clinic compared to those starting by telePrEP. More data is needed to assess engagement given our low sample size for three-month visits. TelePrEP is a promising new tool. Further studies are needed to fully investigate its effect on PrEP access and engagement.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

David M. Higgins, MD, MS was supported by the HRSA of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number D33HP31669 and the National Network of Sexually Transmitted Diseases Clinical Prevention Training Centers, Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Subcomponent A2 [grant number CDC-RFA-PS20-2004]. This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS, CDC or the U.S. Government.” The authors also acknowledge the extraordinary efforts of the PrEP navigation team at the Public Health Institute at Denver Health including Alex Delgado, Alondra Landra, and Tara Hixson.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

No sources of funding were obtained specifically for this study and for all authors, no conflicts of interest were declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2020; vol. 33. Accessed July 14, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center for Disease Control and Prevention: US Public Health Service: Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States - 2021 Update: a clinical practice guideline. Accessed 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2021.pdf

- 3.Rusie LK, Orengo C, Burrell D, et al. Preexposure Prophylaxis Initiation and Retention in Care Over 5 Years, 2012–2017: Are Quarterly Visits Too Much? Clin Infect Dis. Jul 2 2018;67(2):283–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu L, Schumacher C, Chandran A, et al. Patterns of PrEP Retention Among HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Users in Baltimore City, Maryland. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Dec 15 2020;85(5):593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krakower D, Maloney KM, Powell VE, et al. Patterns and clinical consequences of discontinuing HIV preexposure prophylaxis during primary care. J Int AIDS Soc. Feb 2019;22(2):e25250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hojilla JC, Vlahov D, Crouch PC, et al. HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Uptake and Retention Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in a Community-Based Sexual Health Clinic. AIDS Behav. Apr 2018;22(4):1096–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spinelli MA, Scott HM, Vittinghoff E, et al. Missed Visits Associated With Future Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Discontinuation Among PrEP Users in a Municipal Primary Care Health Network. Open Forum Infect Dis. Apr 2019;6(4):ofz101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hevey MA, Walsh JL, Petroll AE. PrEP Continuation, HIV and STI Testing Rates, and Delivery of Preventive Care in a Clinic-Based Cohort. AIDS Educ Prev. Oct 2018;30(5):393–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lankowski AJ, Bien-Gund CH, Patel VV, et al. PrEP in the Real World: Predictors of 6-Month Retention in a Diverse Urban Cohort. AIDS Behav. Jul 2019;23(7):1797–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hubach RD, Currin JM, Sanders CA, et al. Barriers to Access and Adoption of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Among Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM) in a Relatively Rural State. AIDS Educ Prev. Aug 2017;29(4):315–329. 5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegler AJ, Bratcher A, Weiss KM, et al. Location location location: an exploration of disparities in access to publicly listed pre-exposure prophylaxis clinics in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. Dec 2018;28(12):858–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brawley S, Dinger J, Nguyen C, Anderson J. Impact of COVID-19 related shelter-in-place orders on PrEP access, usage and HIV risk behaviors in the United States. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2020;23(S4):e25547.32649039 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krakower D, Solleveld P, Levine K, Mayer K. Impact of COVID-19 on HIV preexposure prophylaxis care at a Boston community health center. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2020;23(S4):e25547.32649039 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Touger R, Wood BR. A Review of Telehealth Innovations for HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP). Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2019/02/01 2019;16(1):113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stekler JD, McMahan V, Ballinger L, et al. HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Prescribing Through Telehealth. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2018;77(5):e40–e42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoth AB, Shafer C, Dillon DB, et al. Iowa TelePrEP: A Public-Health-Partnered Telehealth Model for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Preexposure Prophylaxis Delivery in a Rural State. Sex Transm Dis. Aug 2019;46(8):507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCray E, Mermin J;. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed May 31, 2022. https://www.hiv.gov/blog/prep-during-covid-19

- 18.Budak JZ, Scott JD, Dhanireddy S, Wood BR. The Impact of COVID-19 on HIV Care Provided via Telemedicine-Past, Present, and Future. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. Apr 2021;18(2):98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report. Vol. 32. 2019. May. Accessed November 10, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Health Resources & Services Administration. What is Telehealth? Official website of the Health Resources and Services Administration. Updated March 2022. Accessed June 01, 2022. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/topics/telehealth/what-is-telehealth [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young JD, Abdel-Massih R, Herchline T, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Position Statement on Telehealth and Telemedicine as Applied to the Practice of Infectious Diseases. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2019;68(9):1437–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Player MS, Cooper NA, Perkins S, Diaz VA. Evaluation of a telemedicine pilot program for the provision of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in the Southeastern United States. AIDS Care. Jan 2 2022:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Refugio ON, Kimble MM, Silva CL, et al. Brief Report: PrEPTECH: A Telehealth-Based Initiation Program for HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis in Young Men of Color Who Have Sex With Men. A Pilot Study of Feasibility. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Jan 1 2019;80(1):40–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood BR, Young JD, Abdel-Massih RC, et al. Advancing Digital Health Equity: A Policy Paper of the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the HIV Medicine Association. Clin Infect Dis. Mar 15 2021;72(6):913–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez JA, Clark CR, Bates DW. Digital Health Equity as a Necessity in the 21st Century Cures Act Era. JAMA. 2020;323(23):2381–2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]