Abstract

Background:

Patients with stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA) and periodontal disease (PD) are at increased risk for cardiovascular events. PD treatments that can improve stroke risk factors were tested if they might assist patients with cerebrovascular disease.

Methods:

In this multicenter phase II trial, patients with stroke/TIA and moderately severe PD were randomly assigned to intensive or standard PD treatment arms. The primary outcome measure was a composite of death, myocardial infarction (MI), and recurrent stroke, as well as adverse events. Secondary outcome included changes in stroke risk factors.

Results:

A total of 1209 patients with stroke/TIA were screened, of who 481 met PD eligibility criteria. Of the 280 patients were randomized to intensive arm (N=140) and standard arm (N=140). In 12-month period, primary outcome occurred in 11 (8%) in the intensive arm and 17 (12%) in the standard arm. The intensive arm was non-superior to the standard arm (HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.30–1.38) with similar rates of adverse events (sepsis 2.1% vs. 0.7%, dental bleeding 1.4% vs. 0% and infective endocarditis 0.7% vs. 0%). Secondary-outcome improvements were noted in both arms with diastolic blood-pressure (DBP) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (p<0.05).

Conclusions:

In patients with recent stroke/TIA and PD, intensive PD treatment was not superior to standard PD treatment in prevention of stroke/MI/death. Fewer events were noted in the intensive arm and the 2-arms were comparable in the safety outcomes. Secondary outcome measures showed a trend towards improvement, with significant changes noted in DBP and HDL in both treatment arms.

Keywords: Periodontal Disease, Dental Caries, Myocardial Infarction, Stroke

Subject Terms: Ischemic Stroke, Myocardial Infarction, Dental Infection

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Stroke is the second leading cause of death worldwide, the fifth leading cause of death in the United States, as well as the leading cause of long-term adult disability both worldwide and in the United States1. Recurrent vascular events serve as a substantial contributing factor to the annual stroke rate in the United States2. Several observational studies have shown that periodontal disease (PD) is positively associated with incident vascular event, particularly ischemic stroke, suggesting it may be a potentially modifiable risk factor for stroke3. In a hospital-based cohort study of patients with stroke/TIA, we reported an independent association between moderate to severe PD with recurrent vascular events 4. Within the United States, stroke remains more common in the Southeastern states, referred to as the “stroke belt”. Periodontitis is a destructive form of PD that affects approximately half of US adults 45 and older, and it is more common in the Southeastern “stroke belt” states.5,6

Stroke continues to disproportionately affect African Americans7.The reasons for this racial disparity are not entirely explained by traditional stroke risk factors. The Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study found that tooth loss due to PD was more common among African Americans than whites, and tooth loss was associated with higher stroke risk and stroke risk factors in the stroke belt5. Given these two associations, REGARDS investigators proposed that PD may be contributing to the racial disparity in stroke. Additional data from this study shows that low socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with greater tooth loss and is seen more frequently in African Americans as opposed to their white counterparts4. Since African Americans are at higher risk of PD and vascular events, and treating periodontitis improves atherosclerotic profile and reduces blood pressure in persons with hypertension, it is possible that PD treatment reduces the risk for vascular events8,9. PeRiodontal treatment to Eliminate Minority InEquality and Rural disparities in Stroke (PREMIERS) study was a trial designed to test whether intensive PD treatment reduces the risk of recurrent vascular events among ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA survivors in comparison with standard PD treatment. Additionally, we measured blood pressure, hemoglobin A1C, fasting lipid profile and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) at baseline and after 12-months of PD treatment as secondary outcome measures.

Methods Trial

Design

PREMIERS (www.ClinicalTrials.gov NCT 02541032) was a multicenter, open-label, masked endpoint, adaptive randomization phase II trial in recent stroke or high-risk TIA patients with moderately severe PD10. The primary objective was to evaluate the effect of intensive PD treatment on recurrent vascular events among stroke and high-risk TIA survivors when compared with standard PD treatment. Strict protocols were followed with all adverse events identified and select adverse events that may be associated with PD treatment were reported. Trial activities were conducted in both the inpatient and outpatient clinical settings of the Neurology and Dental departments at both Prisma Health-University of South Carolina and The University of North Carolina- Chapel Hill. This study was approved by the institutional review boards, Human Subjects Research Office of Human Research Ethics at University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and the Prisma Health Institutional Review Board. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Trial Population

Patients ages 18 and above who were admitted to the hospital with recent ischemic stroke or high-risk TIA (defined as ABCD2 score ≥4) were assessed by a study investigator for clinical eligibility, and then consented for the screening dental examinations conducted by clinical calibrated dental examiners. Patients with at least five natural teeth present and signs of moderately severe PD were considered eligible for enrollment (≤ 90 days from index event).

Adaptive Randomization & Masking

After obtaining study informed consent, information regarding the patient’s stroke severity, based on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) obtained at admission, race (questionnaire), SES (questionnaire) and Essen Stroke Risk Score were collected11. SES measure included level of education and annualized household income. The patients were randomized to treatment arms using an adaptive randomization technique ensuring treatment groups were balanced with respect to race, SES, NIHSS and Essen Stroke Risk Score. This adaptive randomization was conducted internally through the Carolina Data Acquisition and Reporting Tool (CDART), a data management tool designed and implemented by the UNC Collaborative Studies Coordinating Center. All individuals who evaluated study outcomes were blinded to the intervention assignments.

PD Treatment

Participants were assigned 1:1 to the standard or intensive treatment groups. The intensive treatment included supragingival and subgingival scaling and root planning using hand instruments and ultrasonic scalers under local anesthesia, extraction of hopeless teeth, local antibiotics (minocycline HCL microspheres, Arestin, Orapharma, USA), oral hygiene instructions (OHI), and supportive PD therapy including PD maintenance, local antibiotics and OHI at each subsequent study visit12,13.The intensive group completed up to five sessions of full-mouth intensive removal of dental plaque biofilms. Teeth that were non-restorable and/or severely affected by periodontitis (periodontal destruction extending to the apical third of the roots, class III furcation, and/or grade ≥ 3 mobility) were extracted after supragingival and subgingival scaling and root planning. Local antibiotic was applied subgingivally to intensive- treatment arm participants at every visit and at the final visit for the standard-treatment arm. The local administration allows for the antibiotic to be placed without crossing into the bloodstream and producing systemic effects14,15. Supportive PD therapy was provided to those randomized into the intensive arm and consists of supragingival mechanical scaling and prophylaxis as indicated and the application of minocycline microspheres into the remaining sites with PD ≥ 5 mm. Participants were also provided with a state-of-the-art ultrasonic toothbrush (Sonicare Flexcare Platinum Sonic Toothbrush, Philips) as well as an interdental cleaner (Sonicare Airfloss Plus, Philips) loaded with an antibacterial mouth rinse (Sonicare BreathRx, Philips). The intensive treatment received these Philips products at the baseline visit.

The standard treatment included full mouth supragingival scaling using hand instruments and ultrasonic scalers under constant irrigation to remove only supragingival plaque and calculus. This was followed by supragingival polishing with abrasive dental polishing paste. Patients were informed of the presence and severity of their PD and advised to seek PD treatment by a dentist or referred for care if their oral condition required immediate attention. All patients, including the standard-treatment group, were reexamined at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months to assure safety. All participants had their periodontal condition monitored to assure no progression of disease. If any site demonstrated an increase in PD > 3 mm, those patients received site- specific subgingival scaling and root planning. At the final 12-month visit they were offered intensive-treatment as described above.

PD Assessment

Clinical measures of PD included Plaque Index (PI), Gingival Index (GI), bleeding on probing (BOP), probing depth, and inter-proximal clinical attachment loss (iCAL) on four sites per tooth16. The number of sites with BOP and probing depth measured at baseline and final visit (12-months) were used as measures of periodontal treatment outcome. Patients were classified using the Periodontal Profile Classes system, which has seven stages to assess severity of PD at baseline. Stage I (healthy/incidental disease) to stage IV (severe disease) are in individuals who are largely dentate, while stages V-VII are those with increasing tooth loss and varying patterns of PD17.

Trial outcomes

The study used major adverse cardiovascular events in the form of ischemic stroke, MI, and cardiovascular death as the primary outcome events. The neurologist monitored at visits for each of these events and checked patient vitals to ensure that all stroke-related risk factors were adequately controlled by medications. Outcome events and select safety outcome events were adjudicated by the site Principal Investigators. The secondary outcomes assessed that were included are blood pressure, hemoglobin A1C, fasting lipid profile and hs-CRP10. Blood pressure was recorded as an averaged triplicate reading from a semiautomatic Omron oscillometric BP monitor. Serial blood samples were collected and assessed for hemoglobin A1C, fasting lipid profile and hs-CRP as measures of stroke risk 10.

The trial outcome events, and selected safety outcome events were submitted to the Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) periodically, as indicated by the study protocol. The study suspension rule was that if the cardiovascular death event rate was significantly higher in one arm when compared with the other arm, the study would be suspended.

Statistical considerations

Our sample size estimation was based on longitudinal data in a cohort of 106 stroke/TIA patients with a high 12-month composite event rate of 14%4. We estimated that the 12-month event rate in the intensive treatment arm would mimic that seen in stroke/TIA with minimal to mild PD (12%) and that in the standard treatment arm would mimic that in moderate to severe PD (30%) translating to an odds ratio of 0.32. Accordingly, the required sample size to detect a medium effect is approximately 64 per group; this translated to having power to detect an odds ratio of at least 0.26 in logistic regression. Given our plan to enroll 140 evaluable patients per group, we would have 80% power to detect an odds ratio of 0.45 for treatment (and 0.298 for the race by treatment interaction) assuming a 10% attrition rate10. We anticipated very little attrition (~10% missing data), and so the trial was powered to detect effect sizes that was between small and medium standardized sizes (approximately at 0.30 standard deviations).

Analysis of primary outcome event was performed on an intention-to-treat basis. The primary outcome was analyzed by means of the time-to-first-event method. Cumulative event-free probabilities were calculated with the use of Kaplan–Meier analysis and tested with the use of the log-rank statistic based on a two-sided type I error rate of 0.05. We first tested the proportional hazards assumption by including time dependent covariate in the Cox regression model. Then we used Cox proportional hazards regression model to estimate the effect of intensive PD treatment, as compared with standard PD treatment, as a hazard ratio with 95% confidence intervals. In planned supplementary analyses, the Cox model was used to estimate the hazard ratio for the primary outcome after adjustment for pre-specified baseline covariates and to test for interactions between treatment and covariates in 9 pre-specified subgroups, with p values reflecting a Bonferroni adjustment for multiple testing 18. There were no missing time-to-event data as patients not keeping appointment(s) were reached by phone, and data was verified by obtaining medical records and/or death certificate. Secondary outcome measures of blood pressure (systolic and diastolic), hemoglobin A1C and fasting lipid profile were assessed at baseline and 12 months. Missing data on secondary outcomes were first analyzed to ensure that they were missing at random, ranged between 5–30% and handled by multiple imputation. They were individually analyzed in each treatment arm using pair-sampled t-test for normally distributed continuous variable and Wilcoxon Sign Rank test for non- normally distributed continuous variables. We used SAS software, version 9.4, for all analyses.

Results

Trial Population

Between January 1, 2016, and December 31, 2020, 1209 ischemic stroke/high risk TIA patients were screened, with 481 (40%) showing evidence of moderately severe PD (Figure 1). Of these, 165 were excluded for medical reasons, and there were 36 screen failures, indicating an inability to meet the criteria for randomization at baseline visit. Of the 280 with moderately severe PD who passed screening and were not excluded for medical reasons, 140 were randomized to intensive PD treatment and 140 to standard PD treatment. The two study arms had similar characteristics at baseline with exception of diabetes (36% in standard arm and 51% in the intensive treatment arm, p=0.01) and BMI (mean±SD= 29.2±6.0 in standard treatment arm and 30.9±6.8 in intensive treatment arm, p=0.02) as depicted in Table 1. In the two study arm groups, the mean age was 60.3 and 59.3 years, respectively. The index event was stroke in 90% of the patients in the standard treatment group and 92% in the intensive treatment group; the median times from the index event to randomization were 44 days and 50 days, respectively, and the highest proportion randomized were in Stage IV PPC with severe PD (69% in standard treatment arm and 63% in the intensive treatment arm), respectively. High proportions of the study subjects (78% in the standard arm and 75% in intensive arm) reported not seeing a dentist or receiving any dental treatment for more than one year prior to the index event. While fairly balanced this was not a criterion used to randomize subjects.

Figure 1: Consort Diagram.

Summary of the trial population – including patient numbers who were screened, randomized into each arm of the trial, and follow-up analysis. TIA – Transient Ischemic Attack, PD – Periodontal Disease

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients at Baseline

| Characteristics | Standard Treatment (n = 140) | Intensive Treatment (n=140) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (yr) † | 60.3±11.9 | 59.3±11.2 | 0.46 |

|

| |||

| Sex (%) | |||

| Female | 51 (36) | 49 (35) | 0.80 |

| Male | 89 (64) | 91 (65) | |

|

| |||

| Race (%) | |||

| African American | 104 (74) | 103 (74) | 0.89 |

| White | 36 (26) | 37 (26) | |

|

| |||

| High-risk TIA (ABCD2 ≥4) | 14 (10%) | 11 (8%) | 0.53 |

|

| |||

| TOAST Stroke subtype | |||

| Large artery atherothrombosis | 24 (19%) | 38 (30%) | |

| Cardioembolism | 27 (21%) | 22 (17%) | 0.25 |

| Small vessel occlusive disease | 37 (29%) | 37 (29%) | |

| Cryptogenic | 38 (30%) | 32 (25%) | |

|

| |||

| NIHSS, median (range) ‡ | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) | 0.87 |

|

| |||

| Essen Stroke Risk, median (range) ‡ | 2 (2–3.8) | 2 (1–3) | 0.60 |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| Basic | 2 (1) | 5 (4) | |

| Intermediate | 81 (58) | 67 (48) | 0.17 |

| Advanced | 57 (41) | 68 (49) | |

|

| |||

| Annual household income | |||

| <$15,000 | 35 (25) | 33 (24) | |

| $15,000–24,999 | 35 (25) | 30 (21) | |

| $25,000–34,999 | 17 (12) | 19 (14) | |

| $35,000–49,999 | 26 (19) | 18 (13) | 0.42 |

| $50,000–74,999 | 8 (6) | 11 (8) | |

| $75,000–99,999 | 7 (5) | 10 (7) | |

| ≥$100,000 | 4 (3) | 12 (9) | |

| Refused | 8 (6) | 7 (5) | |

|

| |||

| Hypertension (%) | 121 (86) | 125 (89) | 0.46 |

|

| |||

| Diabetes (%) | 51 (36) | 72 (51) | 0.01 |

|

| |||

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 23 (16) | 25 (18) | 0.75 |

|

| |||

| Smoking (%) | |||

| Never | 48 (34) | 50 (36) | |

| Former | 51 (36) | 61 (44) | 0.22 |

| Current | 41 (29) | 29 (21) | |

|

| |||

| Alcohol (%) | |||

| Never | 27 (19) | 29 (21) | |

| Former | 55 (39) | 45 (32) | 0.45 |

| Current | 58 (41) | 66 (47) | |

|

| |||

| Body Mass Index† | 29.2±6.0 | 30.9±6.8 | 0.02 |

|

| |||

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) † | 184.2±55.2 | 179.0±53.4 | 0.42 |

|

| |||

| LDL† | 102.9±47.9 | 99.3±43.6 | 0.52 |

|

| |||

| HDL† | 55.6±20.7 | 54.0±18.1 | 0.49 |

|

| |||

| Triglycerides (mg/dl)‡ | 112.5 (83.0–150.8) | 113.5 (74.3–163.8) | 0.49 |

|

| |||

| hs- CRP (mg/dl)‡ | 0.63 (0.32–1.59) | 0.75 (0.24–1.83) | 0.70 |

|

| |||

| WW PPC Stages | |||

| Stage I | 0 | 0 | |

| Stage II | 4 (3) | 2 (1) | |

| Stage III | 7 (5) | 4 (3) | |

| Stage IV | 96 (69) | 88 (63) | 0.49 |

| Stage V | 15 (11) | 19 (14) | |

| Stage VI | 9 (6) | 16 (11) | |

| Stage VII | 9 (6) | 11 (8) | |

mean±standard deviation

median (inter-quartile range)

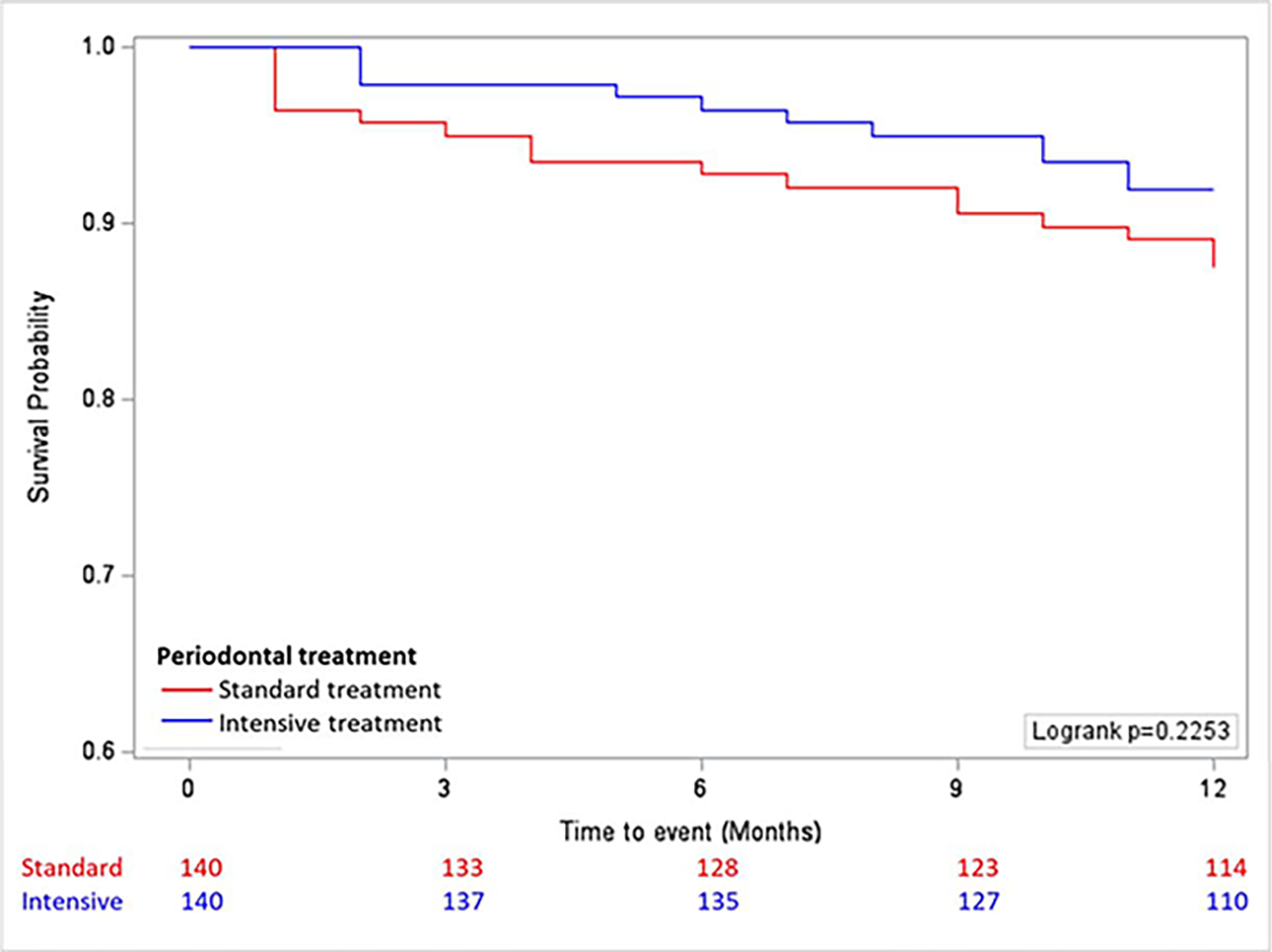

On introduction of time-dependent covariate in the Cox regression analysis, it showed a non- significant result (composite outcome p=0.426, ischemic stroke p=0.255, myocardial infarction p=0.568, death p=0.574) indicating the proportional hazards assumptions was met for each event type. During a median follow-up of 12-months, there were 17 composite events in the standard treatment arm [ischemic stroke (n=10), MI (n=6) or CV death (n=6)] and 11 in the intensive treatment arm had a composite event [ischemic stroke (n=10), MI (n=2) or CV death (N=7)], with no patient lost-to-follow-up for primary outcome measure standard (Table 2). The primary outcome of composite of ischemic stroke/MI/CV death occurred in 17 of 140 (12%) in the standard treatment group and in 11 of 140 (8%) in the intensive treatment group (hazard ratio 0.63 in the intensive treatment group; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.30 to 1.34) (Table 2). This finding did not change after adjustment for covariates. The rates of each subtype for composite events were similar in the two treatment arms and the hazards ratio remained identical after adjustment of covariates. The composite events are depicted in the Kaplan- Meier survival curve (Figure 2) with no statistically significant difference between the intensive treatment arm and the standard treatment arm (Logrank p value = 0.2253). There was no significant interaction noted in the association between treatment and composite event outcome, when stratified by age, sex, race, BMI, LDL cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, education level and severe periodontal disease (PPC stage) as depicted in supplemental figure S1. Although statistically nonsignificant, intensive treatment effect on composite vascular event was note in the patients with hypertension and those with mild- moderate PD.

Table 2.

Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95% Cis) for the association of intensive PD treatment, primary outcome of composite of stroke, myocardial infarction and death, ischemic stroke, MI and death compared with standard PD treatment.

| Standard (n=140) |

Intensive (n=140) |

Crude HR | 95% CI | Adjusted HR* | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite | 17 | 11 | 0.63 | 0.30–1.34 | 0.72 | 0.33–1.56 |

| Stroke | 10 | 10 | 1.02 | 0.42–2.44 | 1.04 | 0.43–2.54 |

| MI | 6 | 2 | 0.76 | 0.14–4.18 | 0.69 | 0.09–5.45 |

| Death | 6 | 7 | 1.42 | 0.45–4.46 | 1.79 | 0.45 –7.09 |

Adjusted for diabetes and BMI

Figure 2: Kaplan Meier Curve for time to composite event (Stroke/MI/Death) in Intensive and Standard Treatment Arm.

Summary of total composite events as survival probability by time to event in months, showing no statistically significant difference between the two treatment arms (Logrank test). The image was created using SAS Version 9.4. The number of patients at each timepoint, as indicated in the panel below the x axis.

Secondary outcomes are depicted in the intensive and standard treatment arms at baseline and 12-months (Table 3). A consistent finding noted across both treatment arms, diastolic pressure was significantly lower (intensive treatment arm, baseline 89±11 vs. 12-month 84±23, p=0.004; as well as standard treatment arm, baseline 89±12 vs. 12-month 84±22, p=0.008). There was also noted a nonsignificant trend of lower systolic blood pressure in both arms. HbA1c was non-significantly lower (intensive treatment arm, baseline 6.8±1.8 vs. 12-month 6.5±2.0, p=0.065); and significantly lower in the standard treatment arm (baseline 6.4±1.6 vs. 12-month 6.1±1.6, p=0.018). Total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides were significantly higher at 12-months in both treatment arms. HDL cholesterol was significantly higher (intensive treatment arm, baseline 54±18 vs. 12-month 70±22, p<0.001; as well as standard treatment arm, baseline 56±21 vs. 12-month 66±20, p<0.001). Serum hs-CRP was non-significantly lower (intensive treatment arm, median 0.75 vs. 12-month 0.52, p=0.206); and significantly lower in the standard treatment arm (baseline 0.63 vs. 12-month 0.33, p=0.004). There was no significant time-treatment interaction noted with any of these parameters, suggesting secondary outcome measures did not change by time and by treatment group.

Table 3.

Effect of standard and intensive PD treatment, on secondary outcome of blood pressure, hemoglobin A1C and lipid profile, over 12-month period.

| Standard PD treatment | Intensive PD treatment | Treatment- time interaction‡ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary outcome | Baseline | 12-month | p- value | Baseline | 12-month | p- value | p-value | |

| Blood pressure | Systolic (mm Hg) | 141 ± 21 | 137 ± 34 | 0.134 | 139 ± 19 | 135 ± 38 | 0.258 | 0.895 |

| Diastolic (mm Hg) | 89 ± 12 | 84 ± 22 | 0.008 | 89 ± 11 | 84 ± 23 | 0.004 | 0.713 | |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.4 ± 1.6 | 6.1 ± 1.6 | 0.018 | 6.8 ± 1.8 | 6.5 ± 2.0 | 0.065 | 0.949 | |

| Lipids | Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 184 ± 55 | 211 ± 74 | 0.038 | 179 ± 53 | 219 ± 70 | <0.001 | 0.221 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 103 ± 48 | 116 ± 59 | 0.013 | 99 ± 44 | 117 ± 54 | <0.001 | 0.560 | |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 56 ± 21 | 66 ± 20 | <0.001 | 54 ± 18 | 70 ± 22 | <0.001 | 0.070 | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL)* | 113 (83–151) | 123 (77–192) | 0.027§ | 114 (74–164) | 132 (93–188) | 0.007§ | 0.553 | |

| Inflammation | hs-CRP (mg/dl)* | 0.63 (0.32–1.58) | 0.33 (0.07–1.02) | 0.004§ | 0.75 (0.23–1.83) | 0.52 (0.21–5.31) | 0.206§ | 0.359 |

Mean±standard deviation except where indicated

median (interquartile range)

p-value for paired sample t-test, except where indicated

Wilcoxon Signed Rank test

Wilk’s lambda derived from repeated measure two-way analysis of variance

The intensive treatment had a stronger significant effect on the number of sites with BOP (baseline 64±36 vs. 12-month 42±29, p<0.001) compared to standard treatment (baseline 65±39 vs. 12-month 49±33, p<0.001). Similarly, the intensive treatment had a stronger significant effect on the number of sites with pocket depth ≥4 mm (baseline 45±25 vs. 12- month 29±24, p<0.001) compared to standard treatment (baseline 48±29 vs. 12-month 40±27, p<0.001). These results suggest a modest but significant treatment effect on PD outcomes in both arms. A more detailed presentation on all the measured PD outcomes, is beyond the scope of this paper.

Selected Safety Outcomes (Adverse Events)

We report the rates of selected adverse events between intensive and standard PD treatment arms (Table 4) that may be specifically associated with dental treatment in patients with ischemic stroke/ high-risk TIA. There was a reported small proportion of patients that presented to the hospital for treatment of sepsis, dental bleeding or infective endocarditis with no statistical difference between treatment arms. The single patient in the intensive treatment with infective endocarditis grew Staphyloccocus epidermidis in blood and heart valve tissue culture, a pathogen common in skin and mucosal membranes, but not generally detected in the oral cavity19.

Table 4.

Selected adverse events between intensive and standard treatment arms.

| Standard (n=140) |

Intensive (n=140) |

p value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis | 1 (0.7%) | 3 (2.1%) | 0.62 |

| Dental bleeding | 0 | 2 (1.4%) | 0.50 |

| Infective endocarditis | 0 | 1 (0.7%) | 0.99 |

Fisher’s exact test

Discussion

Severe gum disease affects 40% of those with ischemic stroke or TIA in a sample of the disparity population of the “stroke belt”5. Several observational studies have reported an association between PD and increased rate of ischemic stroke3. This first of its kind randomized clinical trial analysis of a primary outcome of recurrent composite vascular events failed to show superiority of intensive treatment to standard treatment of PD in prevention of the primary outcome (stroke/MI/death). In a previous study with similar study arms, intensive PD treatment resulted in acute, short-term systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. However, 6 months after therapy, the benefits in oral health were associated with improvement in endothelial function 20. Prior randomized clinical trials also showed that intensive PD treatment led to improvement in stroke and cardiovascular risk factors including hypertension, fasting blood glucose and lipid profile 21. In a prior observational cohort study we found that moderately severe PD was associated with a higher annual rate of composite vascular events in those with high or moderately severe PD (25% over first year and 40% over two-years) and was higher than those without moderately severe or low PD (15% over first year and 25% over two-years)4. Of note, this was an observational study without any specifically prescribed PD treatment. This study serves the basis for our sample size calculation with an assumption that the severe PD would be reflective of the standard or no treatment arm, whereas low PD would be reflective of the intensive treatment arm. The rates of composite vascular events are lower in our standard treatment arm (12%) and the intensive treatment arm (8%) in this study than in the observational study that was used to estimate the sample size calculation. The lower rates noted in our treatment arms may reflect an effect of the standardized stroke prevention strategy or an effect of frequent dental care or both. Of note, the largest group of our patients were African-American, and they were classified as having severe PD -Stage IV disease (Table 1). A recent study show that African-Americans to have high bacteria and systemic antibody responses, with increased risk for periodontal disease and less amenable to treatment17. Secondary outcome analysis noted improved diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and HDL levels in both treatment arms. Recent studies have pointed to this causal relationship between PD and hypertension. It has been shown that these patients generally present with increased arterial BP levels and have between a 30% to 70% higher chance of presentation of hypertension, especially in instances of gingival inflammation22–24. In this study, we saw that both treatments lowered systolic blood pressure (SBP) and significantly lowered DBP in patients with ischemic stroke/high-risk TIA. Studies have shown that patients with PD have elevated LDL and triglyceride levels and decreased HDL levels25,26. Despite an increase in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol and triglycerides in both treatment arms, we do report increases in HDL levels, implicating a possible mechanism by which both forms of PD treatment may lower stroke risk27. Prior studies noted changes in cardiovascular risk profile with intensive treatment in healthy volunteers over a 6-month period21.Our findings on DBP and HDL levels are the first to be noted in ischemic stroke/high-risk TIA patients and may help explain lower recurrent cardiovascular event rates in both treatment arms. Interestingly, in our study we report a lowering of hs-CRP and HbA1c levels that were significant in the standardized treatment arm, and a non-significant in the intensive treatment arm. The dampened effect of the intensive treatment arm may be explained by higher levels of systemic inflammation triggered by the frequent intensive treatment mandated by the study protocol. Systemic inflammation has been tied to insulin resistance and blood glucose control28.

We did not note a significant interaction in the association between intensive PD treatment and composite event outcome, when stratified by age, sex, race, BMI, LDL cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes, smoking and, education level and severe periodontal disease. We did not estimate our sample size to adequately test the interactions. However stratified analyses did show that intensive treatment had a beneficial effect in those with hypertension and mild PD (PPC stage II-IV). This may be explained by the fact that intensive treatment lowered blood pressure and was more effective in treatment of mild to moderate PD.

A limitation in our study design is the predominant proportion of severe PD (stage IV PPC) less amenable to PD treatments. This may be an explanation why only a modest treatment effect on PD outcomes was observed in patients with ischemic stroke/high-risk TIA in both intensive and standard treatment arms with a larger effect noted in the intensive arm. We also report very low rates of related adverse events that were not significantly different in the two study arms. This study is a phase II effectiveness and safety trial with power calculation based on a modest effect size between a group with intensive PD treatment and a control PD treatment arm. In the original protocol (Supplemental File and www.ClinicalTrials.gov NCT 02541032), we proposed to enroll 200 patients in each arm with the ultimate goal of 180 evaluable patients in each group. Approximately two-years into the study it was determined that the target enrollment could not be met within the funding period, with the approval of the study sponsor and DSMB, the protocol was modified to a lower sample size 140 evaluable patients in each treatment group with details of sample size and power calculation10. The study provides important insight into the development of a future phase III clinical trial. We will need to enroll 550 (225 per group) to achieve 80% power to detect an odds ratio of 1.5 if baseline probability is 0.08. The study may also need a longer follow-up of 24 months to note a significant difference in event rates as noted in the preliminary cohort study.

In conclusion, the PREMIERS phase II trial failed to establish superiority of intensive treatment to standard treatment of PD in prevention of primary outcome (stroke/MI/death). Both treatment arms appear to be safe in patients with ischemic stroke/high-risk TIA. This secondary outcome analysis gives some important insight into the role of dental treatment in improving risk factor profiles that may be important in prevention of secondary vascular event after ischemic stroke/high-risk TIA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The study protocol has previously been published and can be found at the below citation.

Redd KT, Phillips ST, McMillian B, Giamberardino L, Hardin J, Glover S, Merchant A, Susin C, Beck JD, Offenbacher S, Sen S. PeRiodontal Treatment to Eliminate Minority Inequality and Rural Disparities in Stroke (PREMIERS): A Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled Study. Int J Cerebrovasc Dis Stroke. 2019;2(2):121. Epub 2019 Nov 8. PMID: 32159164; PMCID: PMC7064156.

Sources of Funding

1 R01 MD009738 PeRiodontal treatment to Eliminate Minority InEquality and Rural disparities in Stroke (PREMIERS) supported by National Institute of Minority Health Disparity.

Orapharma provides the study medication Arestin®

Philips Oral Healthcare provides electric toothbrushes, air flosser, mouthwash, and funds to further support study efforts

North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute Data and Safety Monitoring Board (NC TraCS DSMB) is funded by the NC Clinical and Translational Science Award –CTSA (UL1TR002489)

NIH funded the study, while Phillips and Orapharma donated supplies & products. None of the sponsors had impact on the study design.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BP

Blood Pressure

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- BOP

Bleeding On Probing

- CI

Confidence Interval

- CV

Cardiovascular

- DBP

Diastolic Blood Pressure

- GI

Gingival Index

- HDL

High-Density Lipoprotein

- HR

Hazard Ratio

- hs-CRP

high-sensitivity C-Reactive Protein

- iCAL

inter-proximal Clinical Attachment Loss

- LDL

Low-Density Lipoprotein

- MI

Myocardial Infarction

- NIHSS

National Institute of Health Stroke Scale

- OHI

Oral Hygiene Instructions

- PD

– Periodontal Disease

- PI

Plaque Index

- PPC

Periodontal Profile Class

- SBP

Systolic Blood Pressure

- SES

Socioeconomic Status

- TIA

Transient Ischemic Attack

Footnotes

Disclosure:

Dr. Susin reports compensation from Geistlich Pharma, North America, Inc. for consultant services and compensation from Nobel Biocare USA for consultant services

References

- 1.Statistics NCfH. Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2014. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, de Ferranti S, Després JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, et al. ; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lafon A, Pereira B, Dufour T, Rigouby V, Giroud M, Béjot Y, Tubert-Jeannin S. Periodontal disease and stroke: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:1155–61, e66. doi: 10.1111/ene.12415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sen S, Sumner R, Hardin J, Barros S, Moss K, Beck J, Offenbacher S. Periodontal disease and recurrent vascular events in stroke/transient ischemic attack patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:1420–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.06.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.You Z, Cushman M, Jenny NS, Howard G; REGARDS. Tooth loss, systemic inflammation, and prevalent stroke among participants in the reasons for geographic and racial difference in stroke (REGARDS) study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:615–619. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eke PI, Borgnakke WS, Genco RJ. Recent epidemiologic trends in periodontitis in the USA. Periodontol 2000. 2020;82:257–267. doi: 10.1111/prd.12323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levine DA, Duncan PW, Nguyen-Huynh MN, Ogedegbe OG. Interventions targeting racial/ethnic disparities in stroke prevention and treatment. Stroke. 2020;51:3425–3432. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teeuw WJ, Slot DE, Susanto H, Gerdes VE, Abbas F, D’Aiuto F, Kastelein JJ, Loos BG. Treatment of periodontitis improves the atherosclerotic profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:70–79. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma S, Sridhar S, McIntosh A, Messow CM, Aguilera EM, Del Pinto R, Pietropaoli D, Gorska R, Siedlinski M, Maffia P, et al. Periodontal therapy and treatment of hypertension-alternative to the pharmacological approach. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacol Res. 2021;166:105511. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Redd KT, Phillips ST, McMillian B, Giamberardino L, Hardin J, Glover S, Merchant A, Susin C, Beck JD, Offenbacher S, et al. PeRiodontal Treatment to Eliminate Minority Inequality and Rural Disparities in Stroke (PREMIERS): a multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Int J Cerebrovasc Dis Stroke. 2019;2:121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzek S, Leistritz L, Witte OW, Heuschmann PU, Fitzek C. The Essen Stroke Risk Score in one-year follow-up acute ischemic stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;31:400–407. doi: 10.1159/000323226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silness J, Loe H Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–135. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6. doi: 10.1902/annals.1999.4.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lampl Y, Boaz M, Gilad R, Lorberboym M, Dabby R, Rapoport A, Anca-Hershkowitz M, Sadeh M. Minocycline treatment in acute stroke: an open-label, evaluator-blinded study. Neurology. 2007;69:1404–1410. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000277487.04281.db [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fagan SC, Cronic LE, Hess DC. Minocycline development for acute ischemic stroke. Transl Stroke Res. 2011;2:202–208. doi: 10.1007/s12975-011-0072-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benamghar L, Penaud J, Kaminsky P, Abt F, Martin J. Comparison of gingival index and sulcus bleeding index as indicators of periodontal status. Bull World Health Organ. 1982;60:147–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchesan JT, Moss K, Morelli T, Teles FR, Divaris K, Styner M, Ribeiro AA, Webster-Cyriaque J, Beck J. Distinct microbial signatures between periodontal profile classes. J Dent Res. 2021;100:1405–1413. doi: 10.1177/00220345211009767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hochberg Y A sharper bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika 1988;75:800–802. doi: 10.1093/biomet/75.4.800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otto M Staphylococcus epidermidis--the ‘accidental’ pathogen. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:555–567. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tonetti MS, D’Aiuto F, Nibali L, Donald A, Storry C, Parkar M, Suvan J, Hingorani AD, Vallance P, Deanfield J. Treatment of periodontitis and endothelial function. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:911–920. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Aiuto F, Parkar M, Nibali L, Suvan J, Lessem J, Tonetti MS. Periodontal infections cause changes in traditional and novel cardiovascular risk factors: results from a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am Heart J. 2006;151:977–984. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muñoz Aguilera E, Suvan J, Buti J, Czesnikiewicz-Guzik M, Barbosa Ribeiro A, Orlandi M, Guzik TJ, Hingorani AD, Nart J, D’Aiuto F. Periodontitis is associated with hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:28–39. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvz201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Czesnikiewicz-Guzik M, Osmenda G, Siedlinski M, Nosalski R, Pelka P, Nowakowski D, Wilk G, Mikolajczyk TP, Schramm-Luc A, Furtak A, et al. Causal association between periodontitis and hypertension: evidence from Mendelian randomization and a randomized controlled trial of non-surgical periodontal therapy. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:3459–3470. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pietropaoli D, Monaco A, D’Aiuto F, Muñoz Aguilera E, Ortu E, Giannoni M, Czesnikiewicz-Guzik M, Guzik TJ, Ferri C, Del Pinto R. Active gingival inflammation is linked to hypertension. J Hypertens. 2020;38:2018–2027. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bullon P, Morillo JM, Ramirez-Tortosa MC, Quiles JL, Newman HN, Battino M. Metabolic syndrome and periodontitis: is oxidative stress a common link? J Dent Res. 2009;88:503–518. doi: 10.1177/0022034509337479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Penumarthy S, Penmetsa GS, Mannem S. Assessment of serum levels of triglycerides, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and lowdensity lipoprotein cholesterol in periodontitis patients. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2013;17:30–35. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.107471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Ebrahim S. HDL-Cholesterol, total cholesterol, and the risk of stroke in middle-aged British men. Stroke. 2000;31:1882–1888. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.8.1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luc K, Schramm-Luc A, Guzik TJ, Mikolajczyk TP. Oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in prediabetes and diabetes. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2019;70:809–824. doi: 10.26402/jpp.2019.6.01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.