Abstract

Objective

The Japanese government suspended the proactive recommendation of the human papillomavirus vaccine (HPVv) in 2013, and the vaccination rate of HPVv declined to <1% during 2014–2015. Previous studies have shown that the recommendation by a physician affects a recipient’s decision to receive a vaccine, and physicians’ accurate knowledge about vaccination is important to increase vaccine administration. This study aimed to evaluate the association between physicians’ knowledge of vaccination and the administration or recommendation of HPVv by primary care physicians (PCPs) in the absence of proactive recommendations from the Japanese government.

Design

Cross-sectional study analysed data obtained through a web-based, self-administered questionnaire survey.

Setting

The questionnaire was distributed to Japan Primary Care Association (JPCA) members.

Participants

JPCA members who were physicians and on the official JPCA mailing list (n=5395) were included.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary and secondary outcomes were the administration and recommendation of HPVv, respectively, by PCPs. The association between PCPs’ knowledge regarding vaccination and each outcome was determined based on their background and vaccination quiz scores and a logistic regression analysis to estimate the adjusted ORs (AORs).

Results

We received responses from 1084 PCPs and included 981 of them in the analysis. PCPs with a higher score on the vaccination quiz were significantly more likely to administer the HPVv for routine and voluntary vaccination (AOR 2.28, 95% CI 1.58 to 3.28; AOR 2.71, 95% CI 1.81 to 4.04, respectively) and recommend the HPVv for routine and voluntary vaccination than PCPs with a lower score (AOR 2.17, 95% CI 1.62 to 2.92; AOR 1.88, 95% CI 1.32 to 2.67, respectively).

Conclusions

These results suggest that providing accurate knowledge regarding vaccination to PCPs may improve their administration and recommendation of HPVv, even in the absence of active government recommendations.

Keywords: Primary Care, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE, Community child health

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This is the first study to evaluate the association between primary care physicians’ (PCPs) vaccination knowledge and human papillomavirus vaccine administration and recommendation without proactive recommendation from the Japanese government.

This nationwide study targeted the physician members of the Japan Primary Care Association, which is the largest academic society for PCPs in Japan.

A limitation of this study was its potential selection bias due to the voluntary participation of the PCPs in the survey.

Furthermore, the effects of vaccine hesitancy among parents and media on the PCPs were not evaluated.

Introduction

The WHO recognises cervical cancer and other human papillomavirus (HPV)-related diseases as important global public health concerns and recommends the inclusion of HPV vaccines (HPVv) in national immunisation programmes.1 In Japan, HPVv was introduced in 2009 as a voluntary vaccine without recommendation or funding from the government.2 3 In 2010, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) initiated an urgent promotional campaign for vaccination, and the Government of Japan provided subsidies to local governments for HPVv.2 3 This campaign was successful, and the vaccination rate of HPVv increased to 70%–80% in the targeted group of young girls in 2012.3–6 In April 2013, free-of-charge HPV vaccination of girls aged 12–16 years was initiated as part of the routine vaccination programme.3 7 8 On the other hand, three doses of voluntary bivalent HPVv for ≥10 years females and quadrivalent HPVv for ≥9 years females cost approximately ¥45 000 (US$450, as of April 2013). However, the media widely reported concerns regarding potential adverse effects of HPV vaccination among young girls, including complex regional pain syndrome, giving rise to social distrust and vaccine hesitancy related to HPVv.3 4 7 9 Consequently, the MHLW suspended proactive recommendation of HPV vaccination in June 20137 10; the local governments stopped sending individual notifications to the homes of girls eligible for HPVv although it continued being a part of the routine vaccine programme.10 The HPV vaccination rate declined to less than 1% during 2014–2015.5 6

The Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety (GACVS) reviewed the safety data of HPVv from 2008 to 2015 and found it to be extremely safe.11 In 2017, the GACVS expressed concerns regarding the situation in Japan, stating that the mortality rate from cervical cancer was expected to increase because HPVv was not proactively recommended.11 Suzuki et al reported that there was no association between HPVv and adverse postvaccination symptoms in Nagoya, Japan.12 However, the MHLW did not resume the proactive recommendation of HPV vaccination as of 2019. Vaccine hesitancy has also been reported in other countries, and the WHO identified it as one of 10 threats to global health in 2019.13

Previous studies have shown that vaccine recommendation by a physician affects the recipient’s decision in receiving a vaccine.14–19 Thus, it is important for physicians to have accurate knowledge regarding vaccination to increase vaccine administration or recommendation rates.20–22 In Japan, the HPVv is administered not only by paediatricians, obstetricians and gynaecologists (OBGYNs), but also by primary care physicians (PCPs).23 24 A 2012 nationwide survey on practices and attitudes towards vaccination among PCPs in Japan23 24 showed that the proportion of PCPs administering and actively recommending HPVv was 58.3% and 46.5%, respectively.23 A significant association between PCPs’ awareness of public subsidies for HPVv and recommendation of HPVv vaccination was reported.24 As previously indicated, the government vaccination policy for the HPVv changed following the survey,23 24 and it was expected that these proportions would also change. However, the current fraction of PCPs administering or recommending the HPVv and the association between PCPs’ knowledge about vaccination and their attitude towards HPVv in Japan remain unknown. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the association between PCPs’ knowledge about vaccination and the administration or recommendation of HPVv without proactive recommendation by the government.

Methods

Study design, setting and population

This cross-sectional study analysed data obtained from a web-based, self-administered questionnaire conducted by the Preventive Medicine and Health Promotion Committee Vaccine Team of the Japan Primary Care Association (JPCA), which is the largest academic association for PCPs in Japan. Most JPCA physicians were internists working as PCPs at clinics or hospitals. The survey was conducted from March to June 2019, and the inclusion criteria were JPCA members who were physicians and on the official mailing list for JPCA members. PCPs who were junior residents within 2 years after graduation from medical school were excluded, as this group cannot administer outpatient vaccinations without the supervision of attending physicians. We excluded PCPs who lived outside Japan, were retired, employed in a non-clinical setting or had missing data.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in this study.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire items were obtained from previous questionnaires administered by the Preventive Medicine and Health Promotion Committee Vaccine Team of JPCA23 24 and were distributed using the online mailing list for JPCA members. The questionnaire was conducted using an online tool, SurveyMonkey. The questionnaire was self-conducted and anonymous. It collected data on the participating physicians’ attitudes regarding vaccines, including HPVv (administration or recommendation), through a vaccination quiz; information resources on vaccinations; and baseline characteristics, such as sex, career after graduation, main practice category, practice setting, provision of daily paediatric medical service, population size of the main working area as an administrative unit of the local government, experience as a kindergarten or school physician, and experience raising children (details in main outcome, main factor, vaccination quiz and other factors).

Main outcome

The primary outcomes of this study were the administration of HPVv for routine and voluntary vaccination, respectively. The PCPs were asked to respond with ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the following question: ‘Do you administer routine/voluntary human papillomavirus vaccine?’ Then, we investigated the association between PCPs’ knowledge of vaccination and vaccine administration for each routine and voluntary vaccination, after adjusting for potential confounders (described in other factors).

The secondary outcomes of this study were the recommendation of routine and voluntary HPV vaccination by PCPs. The respondents were asked, ‘How do you recommend routine/voluntary vaccination for HPV?’ The following response options were provided using a Likert-type scale: ‘actively recommend’, ‘recommend occasionally’, ‘no opinion’, ‘do not actively recommend’ and ‘do not recommend’. The response ‘actively recommend’ was considered ‘recommending behaviour’, which is a more positive behaviour.15 Furthermore, the responses ‘recommend occasionally’, ‘no opinion’, ‘do not actively recommend’ and ‘do not recommend’ were considered ‘non-recommending behaviour’. Then, we investigated the association between PCPs’ knowledge of vaccination and vaccine recommendation for routine and voluntary vaccination after adjusting for possible confounders (described in other factors).

Main factor

The main factor was PCPs’ knowledge of vaccination, which was assessed based on a vaccination quiz. The quiz was created by the Preventive Medicine and Health Promotion Committee Vaccine Team of the JPCA using the Delphi method.25 The quiz comprised six general vaccine questions encompassing Japanese vaccination affairs, including a question on HPVv. Scores of 0–6 were assigned based on the number of correct answers to each of the six questions. To obtain a binary variable, we designated scores above the average as high and those below the average as low. The vaccination quiz score (high or low) was considered an independent variable.

Vaccination quiz

Q1. A 12-year-old boy has no history of mumps vaccination according to the Maternal and Child Health Handbook. His mother states that he had developed mumps in his childhood. She mentions that he had visited a clinic with bilateral parotid gland swelling, and the doctor had suspected mumps based on clinical examination without blood tests. Is it then correct to recommend a mumps vaccine to the boy? (Correct answer: correct)

Q2. A 3-month pregnant woman requests an influenza vaccine, and the only available influenza vaccine in the hospital contains thimerosal. Is this vaccine acceptable or contraindicated for this patient? (Correct answer: acceptable)

Q3. Is the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine, an inactivated vaccine, less likely to cause swelling when injected intramuscularly than when injected subcutaneously? (Correct answer: correct)

Q4. Is there a limit to the number of vaccines (including live vaccines) that can be concurrently administered? (Correct answer: there is no limit)

Q5. Is it correct that ‘suspending proactive recommendation of HPV vaccination’ means ‘withholding local governments from sending individual pre-vaccination screening questionnaires for HPV vaccine and notices to each household and actively calling for HPV vaccination through various media rather than the suspension of routine vaccination’? (Correct answer: correct)

Q6. Is it correct that under the ‘Adverse Event Following Immunisation reporting system’, physicians are obligated to report to the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA) when a vaccinated individual begins exhibiting certain symptoms? (Correct answer: correct)

Other factors

Other factors included the physician’s sex, postgraduate years (3–5, 6–10, 11–20, 21–30, 31–40 and ≥41 years), any specialist qualifications, including those related to primary care, main practice category (primary care; family physician, general practitioner, hospitalist/general physician or others; paediatricians, OBGYNs, industrial physician, researcher, administrative staff and others), practice setting (eg, university hospital or general hospital, other hospital, clinic, others; university, research institution, government and health organisation), proportion of paediatric patients (number of paediatric patients with respect to the total patient population) that was high (≥10%) or low (<10%), main working area as an administrative unit of the local government in an urban area (≥50 000 people), experience as a kindergarten or school physician, experience raising children as a parent and information resources about vaccinations (government, academic, commercial,26 online professional community such as website/Facebook group/Twitter/JPCA mailing list27 and none).

Statistical analysis

We performed univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis to estimate the ORs, adjusted ORs (AORs) and 95% CIs, using binary variables for the main outcome. We investigated the association between PCPs’ knowledge of vaccination and HPVv administration or recommendation.

Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed by adjusting for the following possible confounding factors: physician’s sex, postgraduate year, possession of any specialist qualifications, including primary care, main practice category, practice setting, a high or low proportion of paediatric patients, experience raising children as a parent and information resources about vaccinations.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to inspect each variation only for HPVv knowledge (correct or incorrect) rather than for the total quiz score. We used penalised maximum likelihood logistic regression for the analyses when any confounding factors were completely separated.28

The analysis participants were selected after excluding participants with missing data for the main outcome, main factor and the above-mentioned possible confounders.

All statistical analyses used two-tailed tests of significance, with significance set at p<0.05. Analyses were performed using Stata/SE V.14.2 (StataCorp).

Results

Study flow and demographics

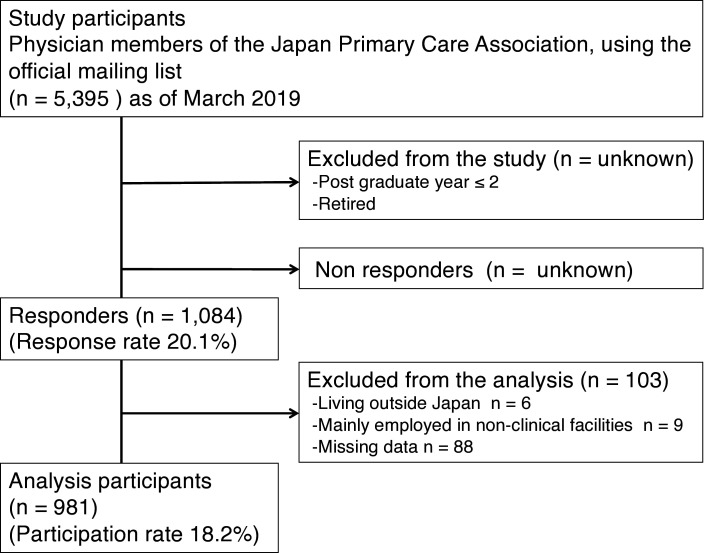

Of the 10 470 physician members of the JPCA, 5075 who did not subscribe to JPCA mails and were, therefore, not on the mailing list were excluded. We received responses from 1084 of 5395 PCPs, with a response rate of 20.1%. The respondents were from all 47 prefectures of Japan. An additional 103 participants were excluded because they lived outside Japan, performed nonclinical work or had missing data. The analysis included 981 participants (figure 1). The median (IQR) score for the vaccination quiz was 4 (range 2–5) points. The minimum and maximum scores were 0 and 6 points, respectively, and the mean (SD) score was 3.47 (1.68) points. To obtain a binary variable, scores of ≥4 were designated as high, and scores of ≤3 as low. Evaluation of the participant baseline characteristics revealed that 739 (75.3%) participants were men, 358 (36.5%) had worked for 11–20 years after graduation, 420 (42.8%) worked in clinics, 719 (73.3%) worked in the urban areas and 283 (28.9%) worked in a clinical setting where the proportion of paediatric patients was ≥10% (table 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants

| Participants, n=981 | |

| n (%) | |

| Sex: male | 739 (75.3), missing 0 |

| Postgraduate year (year) | Missing 0 |

| 3–5 | 92 (9.4) |

| 6–10 | 178 (18.1) |

| 11–20 | 358 (36.5) |

| 21–30 | 193 (19.7) |

| 31–40 | 134 (13.7) |

| ≥41 | 26 (2.7) |

| Main practice category: primary care | 697 (71.1), missing 0 |

| Practice setting | Missing 3 (0.3) |

| University hospital or general hospital | 281 (28.6) |

| Other hospital | 254 (25.9) |

| Clinic | 420 (42.8) |

| Others (eg, university, research institution, government and health organisation) | 23 (2.3) |

| Providing daily paediatric medical service (≥10% of total patients) | 283 (28.9), missing 0 |

| Mainly working in an urban area (≥50 000 people as an administrative unit of the local government) | 719 (73.3), missing 2 (0.2) |

| Experience as kindergarten or school physician | 474 (48.3), missing 0 |

| Experience raising children | 721 (73.5), missing 0 |

Main practice category: primary care: answered main practice category as family physician or general practitioner or hospitalist/general physician.

Factors associated with HPVv administration under routine vaccination

We found that 229 PCPs (23.3%) administered HPVv under routine vaccination (table 2). PCPs with higher vaccination quiz scores were significantly more likely to administer HPVv as routine vaccination than those with lower scores (AOR 2.28, 95% CI 1.58 to 3.28, p<0.001) (online supplemental table 1-1). There was also a positive association between the administration of routine HPV vaccination and PCPs who worked at clinics (AOR 2.64, 95% CI 1.60 to 4.36, p<0.001), those who had a higher proportion of paediatric patients (AOR 1.78, 95% CI 1.24 to 2.55, p=0.002) and those who had experience as a kindergarten or school physician (AOR 2.12, 95% CI 1.45 to 3.10, p<0.001) (online supplemental table 1-1).

Table 2.

Vaccination quiz scores and HPV vaccine administration or recommendation levels among primary care physicians

| Recommendation level for HPV vaccine, n (%) | |||||||

| Vaccination quiz | Total, n (%) | Administration of HPV vaccine | Actively recommend | Recommend occasionally | No opinion | Do not actively recommend | Do not recommend |

| Routine HPV vaccination, n=981 Voluntary HPV vaccination, n=981 |

|||||||

| High scores (4–6 points) | 511 (52.1) | 172 (33.7) 132 (25.8) |

248 (48.5) 131 (25.6) |

179 (35.0) 211 (41.3) |

59 (11.6) 120 (23.5) |

19 (3.7) 31 (6.1) |

6 (1.2) 18 (3.5) |

| Low scores (0–3 points) | 470 (47.9) | 57 (12.1) 43 (9.2) |

160 (34.0) 85 (18.1) |

140 (29.8) 147 (31.3) |

122 (26.0) 168 (35.7) |

30 (6.4) 44 (9.4) |

18 (3.8) 26 (5.5) |

| Total | 981 (100) | 229 (23.3) 175 (17.8) |

408 (41.6) 216 (22.0) |

319 (32.5) 358 (36.5) |

181 (18.5) 288 (29.4) |

49 (5.0) 75 (7.7) |

24 (2.5) 44 (4.5) |

HPV, human papillomavirus.

bmjopen-2023-074305supp001.pdf (56.7KB, pdf)

Factors associated with HPVv administration under voluntary vaccination

We found that 175 PCPs (17.8%) administered HPVv under voluntary vaccination. PCPs with higher scores on the vaccination quiz were significantly more likely to administer HPVv as voluntary vaccination than those with lower scores (AOR 2.71, 95% CI 1.81 to 4.04, p<0.001) (online supplemental table 1-2). There was also a positive association between administration of voluntary HPVv and PCPs who acquired information from governments (AOR 1.90, 95% CI 1.17 to 3.08, p=0.009) and those who participated in a social network service or mailing list from an individual or group of medical service providers (AOR 1.82, 95% CI 1.25 to 2.64, p=0.002) (online supplemental table 1-2).

bmjopen-2023-074305supp002.pdf (56.3KB, pdf)

Factors associated with HPVv recommendation under routine vaccination

The PCPs selected the following options regarding the recommendation of HPVv under routine vaccination: ‘actively recommend’, 408 PCPs (41.6%); ‘recommend occasionally’, 319 PCPs (32.5%); ‘no opinion’, 181 PCPs (18.5%); ‘do not actively recommend’, 49 (5.0%) and ‘do not recommend’, 24 (2.5%) (table 2). PCPs with higher scores on the vaccination quiz were significantly more likely to recommend HPVv under routine vaccination than those with lower scores (AOR 2.17, 95% CI 1.62 to 2.92; p<0.001) (online supplemental table 2-1). However, there was a negative association between recommending routine HPV vaccination and PCPs who worked at other hospitals (AOR 0.69, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.00, p=0.048) and clinics (AOR 0.67, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.98, p=0.041), those who had a higher proportion of paediatric patients (AOR 0.50, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.70, p<0.001) and those who acquired information from government sources (AOR 0.69, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.96, p=0.026) (online supplemental table 2-1).

Factors associated with HPVv recommendation under voluntary vaccination

The PCPs selected the following options regarding the recommendation of HPVv under voluntary vaccination: ‘actively recommend’, 216 PCPs (22.0%); ‘recommend occasionally’, 358 (36.5%); ‘no opinion’, 288 (29.4%); ‘do not actively recommend’, 75 (7.7%) and ‘do not recommend’, 44 (4.5%) (table 2).

PCPs with higher vaccination quiz scores were significantly more likely to recommend HPVv under voluntary vaccination than those with low scores (AOR 1.88, 95% CI 1.32 to 2.67, p<0.001) (online supplemental table 2-2). There was also a positive association between the recommendation of voluntary HPV vaccination and PCPs who were male (AOR 1.67, 95% CI 1.12 to 2.49, p=0.012) and those who participated in a social network service or mailing list for medical service from an individual or group of providers (AOR 1.56, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.24, p=0.016). However, there was a negative association between the recommendation of voluntary HPV vaccination and PCPs who had a higher proportion of paediatric patients (AOR 0.52, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.78, p=0.002) and those who had experience raising children (AOR 0.67, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.00, p=0.049) (online supplemental table 2-2).

The correlation coefficient between vaccine administration and recommendation for routine and voluntary HPV vaccination was 0.17 and 0.23, respectively.

Sensitivity analysis

PCPs with correct responses to the HPV vaccination quiz were significantly more likely to administer HPVv than those with incorrect responses regarding routine vaccination (AOR 2.06, 95% CI 1.38 to 3.09, p<0.001) and voluntary vaccination (AOR 2.16, 95% CI 1.39 to 3.34, p=0.001).

PCPs with correct responses to the HPV vaccination quiz were also significantly more likely to recommend HPV vaccination than those with incorrect responses regarding routine (AOR 1.51, 95% CI 1.12 to 2.04, p=0.006) and voluntary vaccination (AOR 1.53, 95% CI 1.07 to 2.19, p=0.02).

Discussion

Vaccine hesitancy is a global health concern,13 and hesitancy for HPV vaccination has been reported in many countries, including Japan.4–6 This is the first study to focus on the association between PCPs’ knowledge of vaccination and their practice or attitude towards HPVv in the absence of proactive recommendations from the government of Japan. We found positive associations between accurate vaccination knowledge among PCPs and the administration or recommendation of HPVv under routine and voluntary vaccination. In addition, the sensitivity analysis showed that physicians with accurate knowledge of HPV vaccination were likely to recommend HPVv.

A 2021 systematic review of 96 papers from 34 countries examined the perceptions, knowledge and recommendations of healthcare providers regarding vaccines. It showed that the healthcare providers’ recommendations were positively associated with their knowledge and experience, beliefs about disease risk and perceptions of vaccine safety, necessity and efficacy.29 The present results are consistent with these findings.29 In Lebanon, where HPVv is not included in the national routine vaccination schedule as of 2017, physicians practising in OBGYN, paediatrics, family medicine and infectious diseases with greater knowledge regarding HPV and HPVv recommend HPVv more often than physicians with less knowledge (AOR 3.4).30 Further, in the USA, higher rates of completion of three HPVv doses (IRR 1.28) were observed among the patients of primary care clinicians, including family medicine physicians, paediatricians, and family and paediatric nurse practitioners, with greater knowledge regarding HPV and HPVv.31 Our results also support these findings. Another study investigating the association between PCPs’ knowledge of vaccination and the administration or recommendation of voluntary mumps vaccination for adults showed the same positive associations.32

Compared with that in our previous study from 2012,23 the proportion of PCPs recommending or administering HPVv was lower in this study: the proportion of HPVv administration decreased from 58.3% for voluntary vaccination alone23 to 23.3% for routine vaccination and 17.8% for voluntary vaccination (table 2). The proportion of PCPs recommending HPVv decreased from 46.5% for voluntary vaccination alone23 to 41.6% for routine vaccination and 22.0% for voluntary vaccination (table 2).

A study conducted among paediatricians in Osaka, Japan, in 2020 and 2021 revealed that the proportion of paediatricians who administered or actively recommended the HPVv for routine vaccination was 44.5% and 32.5% in 2020 and 67.9% and 40% in 2021, respectively.33 In addition, a study conducted among OBGYNs in Osaka, Japan, showed that the proportion of OBGYNs recommending the HPVv for teenagers was 70.1% in 20173 and 84.6% in 2019.34 As of 2018, the proportion of family physicians and paediatricians in the USA administering the HPVv was 84.1% and 95.3%, respectively,35 and the proportion of those who strongly recommended the HPVv was 72%–90% and 85%–99% (female patients aged 11–12 years, 13–14 years and ≥15 years), respectively.35 Our study revealed that in Japan, PCPs may administer routine HPVv less than paediatricians33 and actively recommend routine HPVv more than paediatricians33 but less than OBGYNs.3 In addition, our study shows that Japanese PCPs may administer or recommend the HPVv less than family physicians in the USA.35

We also found positive associations between different information resources and administration or recommendation of voluntary HPV vaccination. Information resources from social network services or mailing lists from medical service providers seem to be positively associated with the administration or recommendation of voluntary HPV vaccination. This might be because PCPs use virtual communities as valuable knowledge portals for clinically relevant information36 and could be interested in how and why other physicians recommend and administer vaccination.22 32 Government information resources were positively associated with the administration of voluntary HPVv but were negatively associated with the recommendation of routine HPVv. As of 2019, the MHLW had not resumed the proactive recommendation of routine HPV vaccination. Although the suspension of proactive recommendation was not intended to discontinue routine vaccination, it may have been misinterpreted as discontinuation of routine vaccination by some PCPs. Therefore, PCPs referring to government sources for information regarding this policy may administer HPVv as part of voluntary instead of routine vaccination and may not recommend routine HPV vaccination. Alternatively, PCPs aware of the suspension may lose confidence to recommend the HPVv. A previous study reported that the lack of government recommendations was a barrier for PCPs to recommend vaccination.23 In November 2021, the MHLW ended this suspension and resumed proactively recommending HPV vaccination for girls born in or after the fiscal year (FY) 2006, beginning in April 2022,37 and provided ‘catch-up vaccinations’ for 3 years, from April 2022 to March 2025, for females born from FY1997 to FY2005, who became eligible for routine HPV vaccination and may have missed the opportunity to receive the vaccination because of the suspension.38 39 The results of our study suggest that providing accurate knowledge and information about HPV vaccination to PCPs may help promote HPVv administration and recommendation by PCPs and thereby increase the vaccination rate. The JPCA vaccine team provides information about vaccination through websites40 and regular onsite and online vaccine seminars for physicians.41 Further research can help determine the optimal methods to provide accurate knowledge regarding vaccination to healthcare providers with vaccine hesitancy.42

Our study also shows that PCPs working at clinics, providing daily paediatric medical services (more than 10% of total patients), and with experience as kindergarten or school physicians tend to administer routine HPV vaccination (online supplemental table 1-1). The target population for routine HPV vaccination is girls aged 12–16 years, and PCPs experienced in treating this group may better understand the need for routine vaccination; therefore, they may be more likely to administer the vaccine. In contrast, PCPs working at clinics or other hospitals providing daily paediatric medical services (more than 10% of total patients) were less likely to recommend routine HPV vaccination (online supplemental table 2-1). In addition, PCPs providing daily paediatric medical services (more than 10% of total patients) and with experience in raising children tended to be less likely to recommend voluntary HPV vaccination (online supplemental table 2-2). These results suggest that PCPs with more opportunity to provide medical service to girls aged 12–16 years may have less confidence to recommend the HPVv during the suspension of proactive recommendation by the MHLW or may be more affected by the anxiousness or hesitancy of the parents.19 23 43

This study has some limitations. First, there was a potential selection bias due to the low response rate. PCPs who more actively promoted vaccination may have been more likely to respond, and the actual proportion of PCPs administering or recommending HPVv may be lower. Second, our study did not consider voluntary HPV vaccination for men. In Japan, as of 2019, the target group for both routine and voluntary HPV vaccination included only women. However, in 2020, administration of voluntary quadrivalent HPVv was approved for men. Third, our study did not evaluate 9-valent HPVv for voluntary vaccination, although in 2021, the 9-valent HPVv was approved for voluntary vaccination44 and will be approved for routine vaccination from April 2023 onwards.45 Future studies should include both men and women and consider the 9-valent HPVv. Fourth, we did not evaluate the effects of vaccine hesitancy among parents or mainstream media and social media on the PCPs.43 The effect of vaccine hesitancy should be considered as one of the exposures in future studies. Fifth, we did not evaluate the effects of unknown confounding factors, which is a general limitation of observational studies. Finally, although the study participants were physician members of the JPCA, the largest society for PCPs in Japan, the generalisability of the results to PCPs outside of Japan is unclear. The policy for HPVv administration in Japan38 changed after this study was conducted, and further surveys are needed to assess the current situation of HPVv administration and attitudes among PCPs.

Our results suggest that providing accurate knowledge regarding vaccination to PCPs may improve their administration and recommendation of the HPVv, even in the absence of active government recommendations.

Conclusions

We revealed a positive association between PCPs’ knowledge of vaccines and the administration or recommendation of routine and voluntary HPV vaccination without a proactive recommendation from the government. Several factors influence PCPs’ perception of HPV vaccinations, ultimately affecting public healthcare. The results of our study can be applied to other countries with similar vaccination-related concerns, such as vaccine hesitancy and disagreements on vaccine policy between the scientific community and governments.9 46

Our results suggest that providing more knowledge about vaccination to PCPs may increase their likelihood to administer or recommend the HPVv, thereby improving vaccination rates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tesshu Kusaba, President of the Japan Primary Care Association and head office staff for helping us disseminate the questionnaire. We also thank all physicians who participated in this survey. We thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Rei SUGANAGA

Contributors: All authors declare they have contributed to this article. YS designed and implemented the questionnaire survey, contributed to data analysis and interpretation, drafted the manuscript and critically revised it. JT designed and implemented the questionnaire survey, contributed to data interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. RS, KN, YN, HC, TK and AM designed and implemented the questionnaire survey, contributed to data interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. MM contributed to data interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. TO and TS disseminated the questionnaire and critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved this manuscript version for submission. YS acts as the guarantor for this study.

Funding: This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number JP19K19445).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Osaka Medical College (Rin-763). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Electronic address Swi. human Papillomavirus vaccines: WHO position paper, may 2017-recommendations. Vaccine 2017;35:5753–5. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.05.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanley SJB, Yoshioka E, Ito Y, et al. Acceptance of and attitudes towards human Papillomavirus vaccination in Japanese mothers of adolescent girls. Vaccine 2012;30:5740–7. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawada M, Ueda Y, Yagi A, et al. HPV vaccination in Japan: results of a 3-year follow-up survey of Obstetricians and gynecologists regarding their opinions toward the vaccine. Int J Clin Oncol 2018;23:121–5. 10.1007/s10147-017-1188-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ueda Y, Enomoto T, Sekine M, et al. Japan's failure to vaccinate girls against human Papillomavirus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:405–6. 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanley SJB, Yoshioka E, Ito Y, et al. HPV vaccination crisis in Japan. Lancet 2015;385. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61152-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sekine M, Kudo R, Adachi S. Japanese crisis of HPV vaccination. Int J Pathol Clin Res 2016;2:1–3. 10.23937/2469-5807/1510039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yagi A, Ueda Y, Egawa-Takata T, et al. Realistic fear of Cervical cancer risk in Japan depending on birth year. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2017;13:1700–4. 10.1080/21645515.2017.1292190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shono A, Kondo M. Factors that affect voluntary vaccination of children in Japan. Vaccine 2015;33:1406–11. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inokuma Y, Kneller R. Imprecision in adverse event reports following immunization against HPV in Japan and COVID-19 in the USA, UK, and Japan-and the effects of vaccine hesitancy and government policy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2023;79:269–78. 10.1007/s00228-022-03412-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan . Correspondence about the routine vaccination of human papilloma virus infection (recommendation), . 2013Available: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/kekkaku-kansenshou28/pdf/kankoku_h25_6_01.pdf [Accessed 25 Mar 2023].

- 11.World Health Organization . Meeting of the global advisory committee on vaccine safety, 7–8 June 2017. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2017;92:393–402.28707463 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki S, Hosono A. No association between HPV vaccine and reported post-vaccination symptoms in Japanese young women: results of the Nagoya study. Papillomavirus Res 2018;5:96–103. 10.1016/j.pvr.2018.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization . WHO Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019, . 2019Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 [Accessed 25 Mar 2023].

- 14.Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: a theory-informed, systematic review. Preventive Medicine 2007;45:107–14. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oster NV, McPhillips-Tangum CA, Averhoff F, et al. Barriers to adolescent immunization: a survey of family physicians and Pediatricians. J Am Board Fam Med 2005;18:13–9. 10.3122/jabfm.18.1.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor JA, Darden PM, Slora E, et al. The influence of provider behavior, parental characteristics, and a public policy initiative on the immunization status of children followed by private Pediatricians: a study from pediatric research in office settings. Pediatrics 1997;99:209–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuchiya Y, Shida N, Izumi S, et al. Factors associated with mothers not vaccinating their children against Mumps in Japan. Public Health 2016;137:95–105. 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, et al. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: the impact of recommendation quality. Vaccine 2016;34:1187–92. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilkey MB, McRee AL. Provider communication about HPV vaccination: A systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016;12:1454–68. 10.1080/21645515.2015.1129090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collange F, Fressard L, Pulcini C, et al. General practitioners' attitudes and behaviors toward HPV vaccination: A French national survey. Vaccine 2016;34:762–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.12.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong MCS, Lee A, Ngai KLK, et al. Practice and barriers on vaccination against human Papillomavirus infection: A cross-sectional study among primary care physicians in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e71827. 10.1371/journal.pone.0071827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paterson P, Meurice F, Stanberry LR, et al. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine 2016;34:6700–6. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakanishi Y, Hara M, Fukumori N, et al. Primary care physician practices, recommendations, and barriers to the provision of routine and voluntary Vaccinations in Japan. An Official Journal of the Japan Primary Care Association 2014;37:254–9. 10.14442/generalist.37.254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakanishi Y, Yamamoto Y, Hara M, et al. Public subsidies and the recommendation of child vaccines among primary care physicians: a nationwide cross-sectional study in Japan. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020923. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 1995;311:376–80. 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watkins C, Moore L, Harvey I, et al. Characteristics of general practitioners who frequently see drug industry representatives: national cross sectional study. BMJ 2003;326:1178–9. 10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klee D, Covey C, Zhong L. Social media beliefs and usage among family medicine residents and practicing family physicians. Fam Med 2015;47:222–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heinze G, Schemper M. A solution to the problem of separation in logistic regression. Stat Med 2002;21:2409–19. 10.1002/sim.1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin C, Mullen J, Smith D, et al. Healthcare providers' vaccine perceptions, hesitancy, and recommendation to patients: A systematic review. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9:713. 10.3390/vaccines9070713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abi Jaoude J, Khair D, Dagher H, et al. Factors associated with human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine recommendation by physicians in Lebanon, a cross-sectional study. Vaccine 2018;36:7562–7. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rutten LJF, St Sauver JL, Beebe TJ, et al. Clinician knowledge, clinician barriers, and perceived parental barriers regarding human Papillomavirus vaccination: association with initiation and completion rates. Vaccine 2017;35:164–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeuchi J, Sakanishi Y, Okada T, et al. Factors associated between behavior of Administrating or recommending Mumps vaccine and primary care physicians' knowledge about vaccination: A nationwide cross-sectional study in Japan. J Gen Fam Med 2022;23:9–18. 10.1002/jgf2.471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kubota M, Kondo K, Tomiyoshi Y, et al. Survey of Pediatricians concerning the human Papillomavirus vaccine in Japan: positive attitudes toward vaccination during the period of Proactive recommendation being withheld. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022;18:2131337. 10.1080/21645515.2022.2131337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagase Y, Ueda Y, Abe H, et al. Changing attitudes in Japan toward HPV vaccination: a 5-year follow-up survey of Obstetricians and gynecologists regarding their current opinions about the HPV vaccine. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 2020;16:1808–13. 10.1080/21645515.2020.1712173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kempe A, O’Leary ST, Markowitz LE, et al. HPV vaccine delivery practices by primary care physicians. Pediatrics 2019;144:e20191475. 10.1542/peds.2019-1475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rolls K, Hansen M, Jackson D, et al. How health care professionals use social media to create virtual communities. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e166. 10.2196/jmir.5312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan . Notices and Administrative Communication Regarding HPV Vaccine, . 2021Available: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000875155.pdf [Accessed 25 Mar 2023].

- 38.Yagi A, Ueda Y, Nakagawa S, et al. n.d. Can catch-up Vaccinations fill the void left by suspension of the governmental recommendation of HPV vaccine in Japan Vaccines;10:1455. 10.3390/vaccines10091455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan . Notices and Administrative Communication Regarding HPV Vaccine, . 2022Available: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000915791.pdf [Accessed 25 Mar 2023].

- 40.Committee for Infectious Diseases, Vaccine Team, Japan Primary Care Association . Vaccination Website “Vaccination for all", Available: https://www.vaccine4all.jp [Accessed 25 Mar 2023].

- 41.Committee for Infectious Diseases, Vaccine Team, Japan Primary Care Association . The 5th vaccine seminar “Tiger’s Den" 2022 was held!, . 2022Available: https://www.vaccine4all.jp/topics-detail.php?tid=63 [Accessed 25 Mar 2023].

- 42.Lip A, Pateman M, Fullerton MM, et al. Vaccine hesitancy educational tools for Healthcare providers and Trainees: A Scoping review. Vaccine 2023;41:23–35. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.09.093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsui J, Vincent A, Anuforo B, et al. Understanding primary care physician perspectives on recommending HPV vaccination and addressing vaccine hesitancy. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021;17:1961–7. 10.1080/21645515.2020.1854603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan . Q & A regarding HPV vaccine. 2022. Available: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou/hpv_qa.html#Q2-2 [Accessed 25 Mar 2023].

- 45.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan . Information provisions and Administrative Communication Regarding HPV Vaccine, . 2022Available: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/001021317.pdf [Accessed 25 Mar 2023].

- 46.Okubo R, Yoshioka T, Ohfuji S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its associated factors in Japan. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9:662. 10.3390/vaccines9060662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-074305supp001.pdf (56.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-074305supp002.pdf (56.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.