Abstract

During the past few years, Ralstonia (Pseudomonas) solanacearum race 3, biovar 2, was repeatedly found in potatoes in Western Europe. To detect this bacterium in potato tissue samples, we developed a method based on fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). The nearly complete genes encoding 23S rRNA of five R. solanacearum strains and one Ralstonia pickettii strain were PCR amplified, sequenced, and analyzed by sequence alignment. This resulted in the construction of an unrooted tree and supported previous conclusions based on 16S rRNA sequence comparison in which R. solanacearum strains are subdivided into two clusters. Based on the alignments, two specific probes, RSOLA and RSOLB, were designed for R. solanacearum and the closely related Ralstonia syzygii and blood disease bacterium. The specificity of the probes was demonstrated by dot blot hybridization with RNA extracted from 88 bacterial strains. Probe RSOLB was successfully applied in FISH detection with pure cultures and potato tissue samples, showing a strong fluorescent signal. Unexpectedly, probe RSOLA gave a less intense signal with target cells. Potato samples are currently screened by indirect immunofluorescence (IIF). By simultaneously applying IIF and the developed specific FISH, two independent targets for identification of R. solanacearum are combined, resulting in a rapid (1-day), accurate identification of the undesired pathogen. The significance of the method was validated by detecting the pathogen in soil and water samples and root tissue of the weed host Solanum dulcamara (bittersweet) in contaminated areas.

Bacterial wilt or brown rot disease is caused by Ralstonia solanacearum (Smith) (44) (synonyms: Pseudomonas solanacearum [Smith] Smith and Burkholderia solanacearum [Smith]) [43]). The genus Ralstonia has been classified in the beta subclass of the Proteobacteria (20, 25) and falls within rRNA homology group II of the taxon Pseudomonas (29). Many bacteria in this group are potential pathogens for animals and plants (28). Ralstonia pickettii, causing opportunistic infections in humans; Ralstonia syzygii, the causal agent of Sumatra disease of cloves (Syzygium aromaticum) (31); and the blood disease bacterium (BLDB), the causal agent of blood disease of bananas in Indonesia (7), were determined to be very closely related to R. solanacearum based on DNA-DNA and DNA-rRNA hybridizations (30, 31) and 16S rRNA sequence comparisons (34, 37). These species, however, can easily be differentiated from the latter bacterium by host specificity, physiological properties, and geographic distribution (14).

The species R. solanacearum represents a heterogeneous group of strains that has been subdivided into five host-specific races and five biovars based on biochemical properties (14). More recently, genetic analysis of different strains, based on restriction fragment length polymorphism and 16S rRNA sequence analysis, resulted in the postulation of two distinct clusters (6, 37). However, more information is needed to elucidate the relationship of R. solanacearum with the closely related plant pathogens R. syzygii and BLDB strains. R. solanacearum causes significant losses of potatoes and other economically important crops in tropical and subtropical and some warm temperate regions of the world (14). Recently, an increased occurrence in Europe, with a larger outbreak in The Netherlands in 1995, has been reported (18). To control brown rot disease in potatoes, a reliable detection system for the pathogen in its latent form is very important. In advanced stages of infection, the symptoms in potato tubers are clearly visible as vascular discoloration and excretion of bacterial slime. In early stages and in the case of latent infections, however, there are no visible symptoms and the pathogen has to be detected by serological or DNA-based detection methods. Moreover, epidemiological and ecological studies of the distribution of the pathogen in soil, water, and additional host plants (16, 18) are seriously hampered by the lack of reliable detection methods.

In Europe, potato samples are currently screened by using indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) microscopy, following an approved European Plant Protection Organization method (4). In the case of IIF positives, potato sample extracts are plated on the semiselective medium SMSA (10), modified according to the work of Elphinstone et al. (8). To confirm the presence of the pathogen, typical colonies obtained by plating on SMSA are purified and the culture is identified by fatty acid analysis (17), IIF staining, and a pathogenicity test on tomatoes. PCR detection (34) has been used as an alternative to IIF and/or the confirmatory test but was found until now to be not reliable enough (18). The IIF detection technique is not completely reliable due to possible cross-reactions with some other, harmless bacteria (16).

Present identification and confirmation techniques are laborious and time-consuming (more than 2 weeks). The objective of the present study was to develop a fast and reliable detection technique to be used as a second confirmatory method. It has been shown that fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) is a strong tool for detecting bacteria in environmental samples (2, 3). However, FISH has not yet been applied to the detection of brown rot bacteria. PCR detection with R. solanacearum with the primer set developed by Seal et al. (34), targeting 16S rRNA, has shown substantial cross-reactions (this study and reference 38a). Further analysis of 16S rRNA sequences showed no possibility of developing an R. solanacearum-specific probe. Therefore, the 23S rRNA molecule, being twice the size of the 16S rRNA and containing regions that are more variable, was chosen as an alternative target.

In this paper, we report the sequence analysis of genes encoding 23S rRNA (23S rDNA) and the development of two probes specific for R. solanacearum, the closely related R. syzygii, and BLDB strains. Their use in FISH detection experiments is shown, and the validity of the method is discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

All strains tested in this study are described in Table 1, together with their origins and some characteristics. The strains were lyophilized for long-term storage. Ralstonia strains were also stored in sterile demineralized water at room temperature for more than 1 year. Strains were grown routinely on yeast-peptone-glucose (YPG) agar containing the following (per liter): yeast extract, 5 g; peptone, 10 g; glucose, 5 g; and agar, 15 g. The incubation temperature was 28°C in all cases, except for Clavibacter strains that were incubated at 21°C.

TABLE 1.

List of 88 strains used in the study

| Strainb | Race | Biovar | Origin | Countryc | Detection signal

|

Dot blotf | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCAd | PCRe | ||||||

| Ralstonia solanacearum | |||||||

| PD511 = NCPPB 325 | 1 | 1 | Lycopersicon esculentum | USA | + (6,400) | + | a1 |

| PD1449a | 1 | 1 | Lycopersicon esculentum | USA | + (6,400) | + | a2 |

| PD278a | 1 | 3 | Solanum tuberosum | Indonesia | + (6,400) | + | a3 |

| PD1450a | 1 | 4 | Solanum tuberosum | Sri Lanka | + (12,800) | + | a4 |

| PD1682 | 1 | 3 | Zingiber officinale | Thailand | + (12,800) | + | a5 |

| PD1445a | 2 | 1 | Musa sp. | Panama | + (12,800) | + | a6 |

| PD1446 | 2 | 1 | Heliconia sp. | Costa Rica | + (3,200) | + | a7 |

| PD1653 | 2 | 1 | Musa sp. | Honduras | + (12,800) | + | a8 |

| PD441 = IPO 267 | 3 | 2 | Solanum tuberosum | Sweden | + (12,800) | + | b1 |

| PD446 | 3 | 2 | Solanum tuberosum | Egypt | + (12,800) | + | b2 |

| PD1428 = UQM 01059 | 3 | 2 | Solanum tuberosum | Australia | + (12,800) | + | b3 |

| PD2762a | 3 | 2 | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | + (12,800) | + | b4 |

| PD2763 = IPO 1609 | 3 | 2 | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | + (12,800) | + | b5 |

| PD2969 | 3 | 2 | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | + (6,400) | + | b6 |

| PD2970 | 3 | 2 | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | + (6,400) | + | b7 |

| PD2281 | 1 | 4 | Curcuma sp. | The Netherlands | + (12,800) | + | b8 |

| PD2272 | 1 | 4 | Curcuma longa | The Netherlands | + (6,400) | + | c1 |

| PD2883 = NCPPB 501 | 3 | Brassica oleracea bv. capitata | Mauritius | + (6,400) | + | c2 | |

| PD2884 = NCPPB 283 | 1 | Solanum panduraforme | Zimbabwe | + (6,400) | + | c3 | |

| PD2885 = NCPPB 337 | 1 | Nicotiana tabacum | USA | + (6,400) | + | c4 | |

| PD2886 = NCPPB 500 | 3 | Vica faba | Mauritius | + (6,400) | + | c5 | |

| PD2887 = NCPPB 502 | 3 | Casuarina aquisetifolia | Mauritius | + (6,400) | + | c6 | |

| PD2888 = NCPPB 503 | 3 | Dahlia sp. | Mauritius | + (6,400) | + | c7 | |

| PD2890 = NCPPB 791 | 3 | Eclipta alba | Costa Rica | + (6,400) | + | c8 | |

| PD2891 = NCPPB 1045 | 3 | Solanum melongena | Kenya | + (6,400) | + | d1 | |

| PD2892 = NCPPB 1484 | 3 | Strelitaia reginae | Mauritius | + (6,400) | + | d2 | |

| PD2893 = NCPPB 1486 | 3 | Arachis hypogaea | Uganda | + (6,400) | + | d3 | |

| PD2898 = NCPPB 505 | 1 | Symphytum sp. | Zimbabwe | + (6,400) | + | d4 | |

| BLDB | |||||||

| PD2100 = GSPB 1845 | Musa ABB | Indonesia | + (3,200) | + | d5 | ||

| PD2101 = GSPB 1790 | Musa AAA | Indonesia | + (1,600) | + | d6 | ||

| PD2110 = GSPB 1791 | Unknown | Indonesia | + (800) | + | d7 | ||

| Ralstonia syzygii | |||||||

| PD2093 = GSPB 2088 | Syzygium sp. | Indonesia | + (12,800) | + | d8 | ||

| PD2094 = GSPB 2090 | H. falva (vector) | Indonesia | + (12,800) | + | e1 | ||

| PD2095 = GSPB 2093 | Syzygium sp. | Indonesia | + (12,800) | + | e2 | ||

| Ralstonia pickettii | |||||||

| PD1285 | Blood | Malaysia | w (25) | ± | e3 | ||

| PD1287 | Eye swab | Malaysia | w (25) | ± | e4 | ||

| PD1510 | w (25) | ± | e5 | ||||

| PD1513 = NHI 76/2779 | Blood culture | New Zealand | w (100) | − | e6 | ||

| PD1514 = NHI 76/3915 | Crystal violet solution | New Zealand | − | − | e7 | ||

| PD1515 = NHI 81/0160a | Wound | New Zealand | + (400) | − | e8 | ||

| PD2783 | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | w (100) | ± | f1 | ||

| PD2847 | Cucumis sativus | The Netherlands | + (25) | ± | f2 | ||

| PD2848 | Cucumis sativus | The Netherlands | w (25) | ± | f3 | ||

| PD2850 | Sludge | The Netherlands | − | ± | f4 | ||

| Burkholderia cepacia | |||||||

| PD959 = NCPPB 2993 | Allium cepa | Unknown | w (100) | ± | f5 | ||

| PD1700 = CFBP 1434 | Allium cepa | Unknown | + (25) | ± | f6 | ||

| PD1489 = LMG 6995 | Male patient | Sweden | w (25) | ± | f7 | ||

| IPO 1703 = NCPPB 946 | UK | − | − | f8 | |||

| Burkholderia gladioli | |||||||

| PD981 = NCPPB 1891 | Gladiolus sp. | Unknown | w (25) | ± | g1 | ||

| PD1706 = CFBP 1435 | Allium cepa | USA | w (100) | ± | g2 | ||

| Pseudomonas cichorii PD1701 = NCPPB 907 | Chrysanthemum morifolium | Italy | w (25) | ± | g3 | ||

| Pseudomonas fluorescens PD1702 = CFBP 1968 | Apium graveolens | Italy | − | − | g4 | ||

| Pseudomonas marginalis PD1592 = NCPPB 1232 | Musa sp. | Uganda | − | − | g5 | ||

| Pseudomonas corrugata PD1707 = CFBP 2431 | Unknown | Unknown | − | − | g6 | ||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PD1283 | Sputum | Malaysia | − | − | g7 | ||

| Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae PD1704 = NCPPB 281 | Syringa vulgaris | UK | + (100) | − | g8 | ||

| Pseudomonas gladioli pv. allulicola PD973 = NCPPB 947 | Unknown | Unknown | w (25) | ± | h1 | ||

| Pseudomonas viridiflava PD1705 = NCPPB 1249 | Chrysanthemum morifolium | UK | − | − | h2 | ||

| Pseudomonas putida PD1596 = ATCC 17430 | Unknown | Unknown | − | − | h3 | ||

| Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus PD323 = NCPPB 2140 | Solanum tuberosum | Unknown | w (100) | − | h4 | ||

| Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis PD223 = NCPPB 2979 | Lycopersicon lycopersion | Hungary | w (25) | − | h5 | ||

| Erwinia chrysanthemi | |||||||

| PD484 = IPO 764 | w (25) | − | h6 | ||||

| PD551 | Kalanchoe blossfeldiana | The Netherlands | w (25) | − | h7 | ||

| PD2792 | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | − | − | h8 | ||

| PD2796 | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | − | − | i1 | ||

| Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora | |||||||

| PD578 | Solanum tuberosum | w (25) | − | i2 | |||

| IPO 1710 = INRA 2.33 | France | w (100) | − | i3 | |||

| Erwinia carotovora subsp. atroseptica PD230 = IPO 161 | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | w (25) | − | i4 | ||

| Lactic acid bacteria | |||||||

| PD70 | w (25) | − | i5 | ||||

| PD71 | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | w (25) | − | i6 | ||

| PD199 | Solanum tuberosum | North Yemen | w (25) | − | i7 | ||

| PD1192 | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | w (25) | − | i8 | ||

| Aureobacterium liquefaciens IPO 1692 = IVIA 1580.6 | Spain | + (400) | − | i1 | |||

| Rathayibacter tritici IPO 1690 = IVIA 1580.3 | Spain | + (800) | + | i2 | |||

| Ochrobactrum anthropi | |||||||

| IPO 1682 = IVIA 1521.10.1 | Spain | − | − | i3 | |||

| IPO 1689 | − | − | i4 | ||||

| Paenibacillus polymyxa IPO 1721 = CFBP1954 | France | w (25) | + | i5 | |||

| Saphrophytes | |||||||

| PD1685 | Solanum tuberosum | Poland | + (25) | + | i6 | ||

| PD1687 | Solanum tuberosum | Poland | w (25) | + | i7 | ||

| PD1689 | Solanum tuberosum | Poland | w (25) | + | i8 | ||

| PD2809 | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | + (400) | − | k1 | ||

| PD2813 | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | + (200) | − | k2 | ||

| PD2318 | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | w (50) | + | k3 | ||

| PD2818 | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | + (50) | − | k4 | ||

| PD226 = IPO 502 | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | w (25) | + | k5 | ||

| IPO S339 = 15a | Solanum tuberosum | The Netherlands | + (12,800) | − | k6 | ||

| IPO S342 = IC137 | Soil | The Netherlands | + (12,800) | − | k7 | ||

| PD2778 | Milk | The Netherlands | w (25) | ± | k8 | ||

a Used for sequence analysis.

b PD strains are from the culture collection of the Plant Protection Service, Wageningen, The Netherlands; IPO strains are from the culture collection of the Research Institute for Plant Protection, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

c USA, United States of America; UK, United Kingdom.

d Serological reaction with antiserum IPO 9523B-K1 (homolog of PD441) against R. solanacearum. +, −, and w, positive, negative, and weak, respectively. Numbers in parentheses indicate the dilution series tested. The dilution series tested was 25, 50, 100, 200, etc., up to 25,600.

e PCR amplification signal with 16S rDNA primer developed by Seal et al. (34). +, −, and ±, positive, negative, and aspecific, respectively.

f Position on the dot blot.

DNA extraction.

Bacterial strains were grown for 2 days in liquid YPG medium. For DNA extraction, cells of a 1.5-ml culture were pelleted by centrifugation for 5 min at 5,000 × g. Thereafter, cells were washed once in water and lysed by adding sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to a final concentration of 1% (wt/vol). Subsequently, DNA was purified by a standard phenol-chloroform protocol (33).

Amplification of the 23S rRNA gene.

Almost the full length (99.3%) of the 23S rRNA gene was amplified in two PCRs. The first part of the 23S rRNA gene (5′ end), called PCR A, was amplified by using primer 1493f16, located at the end of the 16S rRNA gene, and primer 1622r23. The second part (3′ end), called PCR B, was amplified by using primers 1057f23 and 2861r23, giving an overlap of 500 nucleotides with product PCR A. Primers used for amplification and sequencing, were slightly modified to obtain similar annealing temperatures for each primer pair (Table 2). The PCRs were carried out in a GeneAmp PCR System 2400 (Perkin-Elmer Corp., Norwalk, Conn.) with the Expand High Fidelity PCR System according to the recommendations of the supplier (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). The reaction mixture (100 μl) contained 10 μl of 10× Taq buffer, 100 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden), 100 nM (both) primers (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium), 1.75 U of High Fidelity Taq enzyme mix, 3 mM MgCl, and 1 μl of the template DNA solution (approximately 100 ng/μl). The thermocycler program for amplification was as follows: initial denaturation for 5 min at 94°C, 40 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 1 min at the respective annealing temperature, and 2 min at 72°C; and a final extension of 7 min at 72°C. The annealing temperature for PCR A was 54°C, and that for PCR B was 52°C. The amplified products were purified with the Qiaquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany).

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide sequences of primers used for amplification and sequence analysis

| Primera | Positionb | Sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1493f16 | 1493–1511c | 5′ GGCTGGATCACCTCCTTTC 3′ | 26 |

| 577r23 | 577–559d | 5′ CATTATACAAAAGGTACGC 3′ | Modification of reference 21 |

| 1057f23 | 1057–1075d | 5′ ADGTTGGCTTAGAAGCAGC 3′ | Modification of reference 24 |

| 1108r23 | 1108–1091d | 5′ AYYAGTGAGCTATTACGC 3′ | This study |

| 1602f23 | 1602–1620d | 5′ TACCSCAAACCGACACAGG 3′ | This study |

| 1622r23 | 1622–1605d | 5′ CACCTGTGTCGGTTTGSG 3′ | Modification of reference 21 |

| 2053f23 | 2053–2069d | 5′ GACGGAAAGACCCCRTG 3′ | Modification of reference 21 |

| 2654f23 | 2654–2669d | 5′ AGTACGAGAGGACCGG 3′ | 21 |

| 2861r23 | 2861–2843d | 5′ ATTACTGCGCTTMCACACC 3′ | This study |

a Abbreviations according to International Union of Bacteriologists codes.

b Nucleotide numbering according to E. coli sequence (5).

c Target is 16S rDNA.

d Target is 23S rDNA.

Sequence analysis.

To analyze the sequences of the 23S rRNA gene, a direct sequencing approach was used. The sequence primers had a 5′-IRD-41 modification (infrared label; MWG-Biotech GmbH, Ebersberg, Germany). A total of seven primers were used to obtain the nearly complete sequence (Table 2). The sequence of PCR A was analyzed with primers 577r23, 1108r23, and 1622r23; PCR B was analyzed with primers 1057f23, 1602f23, 2053f23, and 2654f23. From each purified PCR product (± 2.0 kb), approximately 0.8 μg of DNA was used in a sequence reaction. For sequence analysis, a Thermo Sequenase Fluorescent Labelled Primer Cycle Sequencing kit with 7-deaza-dGTP (Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) and the Li-Cor DNA Sequencer 4000 (Li-Cor, Lincoln, Nebr.) were used. Sequencing reactions were performed in an Amplitron II (Thermolyne, Dubuque, Iowa) with the following thermocycler program: 3 min at 94°C and 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 45°C, and 15 s at 72°C. Sequences were handled and aligned with the programs available on the Internet (35, 41).

Phylogenetic analysis.

The determined 23S rRNA sequences were aligned with the ARB software package (36), which also takes into consideration the secondary structure. Calculations of evolutionary distances were done according to the method of Felsenstein (11). A phylogenetic tree (i.e., an unrooted tree) as defined by Woese (40) was constructed by the neighbor joining method (32) as implemented in the ARB package.

RNA extraction.

For RNA isolation, each strain was grown in 5 ml of liquid YPG medium until mid-log phase (1 to 2 days). All glassware was baked at 180°C for 6 h, solutions were sterilized by autoclaving, and all isolation steps were performed at 4°C or on ice. Cells were pelleted in a precooled centrifuge at 3,500 × g for 10 min at 4°C and stored at −20°C. Each pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of TN150 buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl [12]) and transferred to a 2-ml bead-beater tube containing 0.3 g of 0.1-mm-diameter zirconium beads (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, Okla.) and 150 μl of acid phenol (33). The tubes were treated in a Mini-Beadbeater (Biospec Products) three times for 30 s at 5,000 rpm. Subsequently, samples were purified by a standard phenol-chloroform protocol (33). The nucleic acids were precipitated by adding 0.1 volume of 2 M NaAc (pH 4.2; a low pH preferably precipitates rRNA) and 1 volume of cold isopropanol. The RNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 15 min, and the pellet was washed with 500 ml of 70% cold ethanol and again centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min. The isolated rRNA was resuspended in 100 μl of RNA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0). The concentration of the total RNA isolated was determined visually in a 3% agarose ethidium bromide-stained gel with a known concentration of rRNA standard (purified Escherichia coli rRNA; Boehringer).

Dot blot hybridizations.

Approximately 200 ng of each isolated rRNA was blotted on a nylon membrane (Hybond-N; Amersham) with a Hybri Dot manifold (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.). The membrane was pretreated with 10 ml of hybridization solution (0.5 M phosphate buffer, 1% bovine serum albumin, 7% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.2) for 1 h, before addition of 1 μl of 10 μmol of oligonucleotide probe stock liter−1 5′ labeled with 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham). Hybridization was performed at 42°C with the universal 23S rRNA targeted probe 1108r23 or at 45°C with the newly developed R. solanacearum-specific probes. The membranes were washed twice with 0.1% SDS–0.2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) for 20 min at 42°C for the universal probe and 48°C for the specific probes. Visualization of the radioactive signal was done with the PhosphorImager system (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.).

FISH.

Pure cultures used for in situ hybridization were grown in liquid YPG medium at 28°C for 1 day, and each culture was diluted to approximately 106 cells ml−1. Bacteria from naturally infected potato tubers were extracted following the standard protocol of the European Plant Protection Organization (4). Colonies that appeared on semiselective SMSA medium after plating of concentrated surface water samples were diluted in sterile water to approximately 106 cells ml−1. For the extraction of R. solanacearum from bittersweet (Solanum dulcamara), plants were collected and roots were washed in sterile water. Root samples and (basal) stem samples of individual plants were surface sterilized with 70% ethanol and dried on tissue paper. Stem pieces and roots (crushed) were left for at least 30 min in 5 ml of sterile phosphate buffer (0.05 M, pH 7.2). The extracts were concentrated 50 times by centrifugation. Subsequently, 50 μl of the diluted pure cultures or potato tuber or bittersweet extracts was pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 4,000 × g. Cells were fixed for 2 h at 4°C by resuspending the pellet in an equal amount of a freshly prepared 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) solution in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (10 mM phosphate buffer [pH 7.4] and 140 mM NaCl). After fixation, the samples were washed twice with PBS and resuspended in 50 μl of PBS. Ten microliters of each sample was spotted in duplicate on a 10-well microscope slide and dried at room temperature. The samples on the slide were dehydrated by incubation for 2 min in 50, 80, and 96% ethanol. In situ hybridization was performed at 45°C by adding 10 μl of hybridization solution (containing 0.9 M NaCl, 20% formamide, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 0.01% SDS, and 0.5 μl of each 10 μM probe stock) to each well. The synthetic oligonucleotide probes were labeled either with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) for the eubacterial probe EUB338 (1) or with Cy3 (Biological Detection Systems, Pittsburgh, Pa.) for the specific probes RSOLA and RSOLB (MWG-Biotech GmbH. Labeled probes were purified by high-pressure liquid chromatography. In FISH experiments, each sample was hybridized simultaneously with probe EUB338 and probe RSOLA or RSOLB. Slides were incubated at 45°C for 4 h or overnight in an equilibrated moist chamber. A shorter incubation time showed less reproducible results (data not shown). Excess probe was removed by washing the slide twice in hybridization solution without formamide for 20 min at 48°C. Slides were dipped in water, air dried, and mounted in Vectashield Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.); coverslip was applied; and slides were immediately observed with a Zeiss Axioplan microscope fitted for epifluorescence microscopy. When FISH detection was combined with subsequent IIF detection, after washing, 25 μl of 1/1,600-diluted polyclonal antibody (IPO 9523B-K1, homolog of R. solanacearum PD441) was applied to each well, incubated for 30 min at room temperature in a moist chamber, and washed for 3 min with PBS-Tween (0.1%) and PBS. Subsequently, 25 μl of 1:100 swine–anti-rabbit FITC conjugate (Nordic, Tilburg, The Netherlands) was applied and slides were incubated for 30 min in a moist chamber. Slides were washed again for 3 min at room temperature with PBS-Tween and PBS. Slides were subsequently treated as described above.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 23S rDNA sequences from R. solanacearum PD278, PD1445, PD1449, PD1450, and PD2762 and R. pickettii PD1515 were deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF012416 to AF012421, respectively.

RESULTS

Sequence of 23S rDNA and phylogenetic analysis.

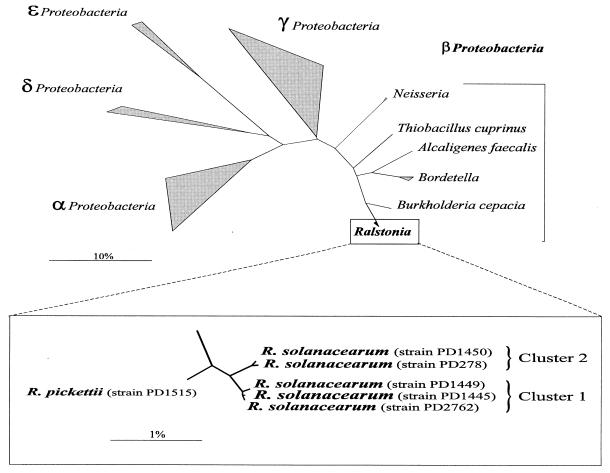

For the development of a specific R. solanacearum probe, five R. solanacearum strains (Table 1) representing race 1, biovars 1, 3, and 4; race 2, biovar 1; and race 3, biovar 2, and one R. pickettii strain (Table 1) were chosen for sequence analysis. R. pickettii was chosen as a closely related species that should be differentiated from the former species, as they may occur in similar habitats. For each strain, the 23S rDNA was amplified by using the two primer pairs 1493f16-1057r23 and 1056f23-2861r23. A PCR product of about 2 kb was obtained from all six Ralstonia strains. Direct sequencing of these PCR products after purification gave no difficulties and eliminated the need to clone the two PCR products. Comparison of the 2,816 sequence positions determined for the six strains resulted in only 35 differences, supporting the expected close relationship between the analyzed strains. For example, the nucleotide sequences of the R. solanacearum race 3, biovar 2 strain (PD2762) isolated from potato (Solanum tuberosum) in The Netherlands and the race 2, biovar 1 strain (PD1445) isolated from bananas (Musa sp.) in Panama showed just one difference. For all five R. solanacearum strains, the 23S rDNA sequence differed at only 12 sequence positions from that for R. pickettii. The R. solanacearum strains are clearly subdivided into two clusters. Cluster 1 includes biovar 1 (strains PD1445 and PD1449) and biovar 2 (PD2762), and cluster 2 includes biovar 3 (PD278) and biovar 4 (PD1450). The sequence similarity values of R. pickettii PD1515 for clusters 1 and 2 are 99.3 and 99.0%, respectively. The relationship among the strains is visualized in an unrooted neighbor joining tree (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Unrooted phylogenetic tree from 23S rRNA sequences showing the relationships of the examined sequences to the major groups of the Proteobacteria. Bars indicate 10% and 1% sequence divergence, respectively.

Design of oligonucleotide probes.

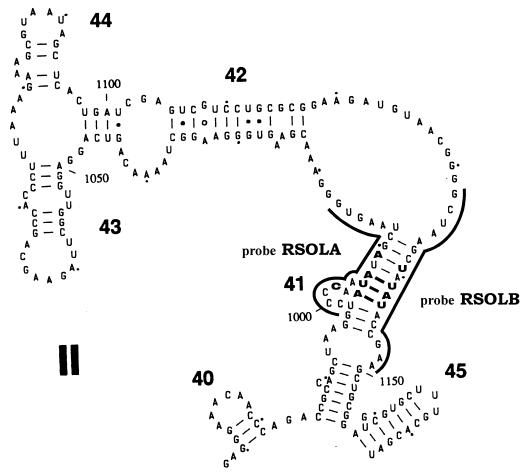

Despite the fact that only a few sequence differences were found between the analyzed 23S rDNA sequences of the R. solanacearum strains and that of the R. pickettii strain, two specific probes could be designed. In region II of the 23S rRNA sequence (15) at positions 1007 to 1009 and 1143 to 1145, different nucleotides are present in the R. pickettii strain compared to all R. solanacearum strains. In these regions, no differences exist among the 23S rRNA sequences of the R. solanacearum strains. The discriminating triplets are part of a stem loop structure in region II, at complementary positions (Fig. 2), and they form the basis for the construction of the specific probes RSOLA and RSOLB (positions 1005 to 1023 [sequence, 5′ CACTTAGCCAATCTTAGGG 3′] and positions 1139 to 1156 [sequence, 5′ TTCGGTGACTGGCTTAGC 3′], respectively). (Nucleotides are numbered according to the E. coli sequence.) Because the nucleotides were found to be part of a secondary stem loop structure, probes were designed in a way so that non-base-pairing nucleotides were also included in the probe sequence. When sequences were compared to the 23S rDNA database, the most closely related sequence was that from Burkholderia cepacia, showing four (RSOLA) and five (RSOLB) mismatches.

FIG. 2.

Part of region II of the secondary structure model for the 23S rRNA molecule of B. cepacia (15). Regions where the two specific probes are located are represented by a single line; the nucleotides that do not match those in R. solanacearum are shown in boldface.

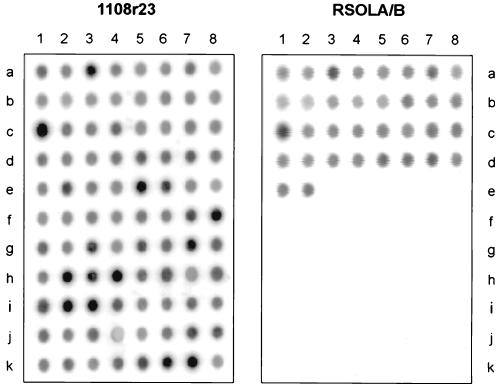

Probe specificity in dot blot experiments.

Specificity of the R. solanacearum probes RSOLA and RSOLB was tested by dot blot hybridization. rRNA was isolated from 88 strains (Table 1) covering closely related bacteria, strains that yielded a cross-reaction in the IIF test, and/or those that gave an amplification product in 16S rDNA-PCR detection according to the work of Seal et al. (34) (Table 1). Probe RSOLA hybridized with all R. solanacearum strains and with the very closely related R. syzygii and BLDB strains (Fig. 3); similar results were obtained with probe RSOLB (data not shown). Both probes showed high specificity, since even under low-stringency washing conditions (i.e., 48°C and 0.2× SSC) the above-mentioned results were obtained. Hybridization of the same membrane with the universal probe 1108r23 yielded positive signals for all strains used, indicating the presence of bacterial 23S rRNA on the blot (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Dot blot hybridization of two identical filters containing rRNA of 88 strains, including R. solanacearum, R. syzygii, BDLB, R. pickettii, different Pseudomonas strains, representatives of plant-pathogenic genera, and potato saprophytes. The filter was hybridized with eubacterial probe 1108r23 and subsequently with R. solanacearum-specific probe RSOLA or RSOLB. The positions of the strains on the dot blot are given in Table 1.

FISH with specific probes RSOLA and RSOLB.

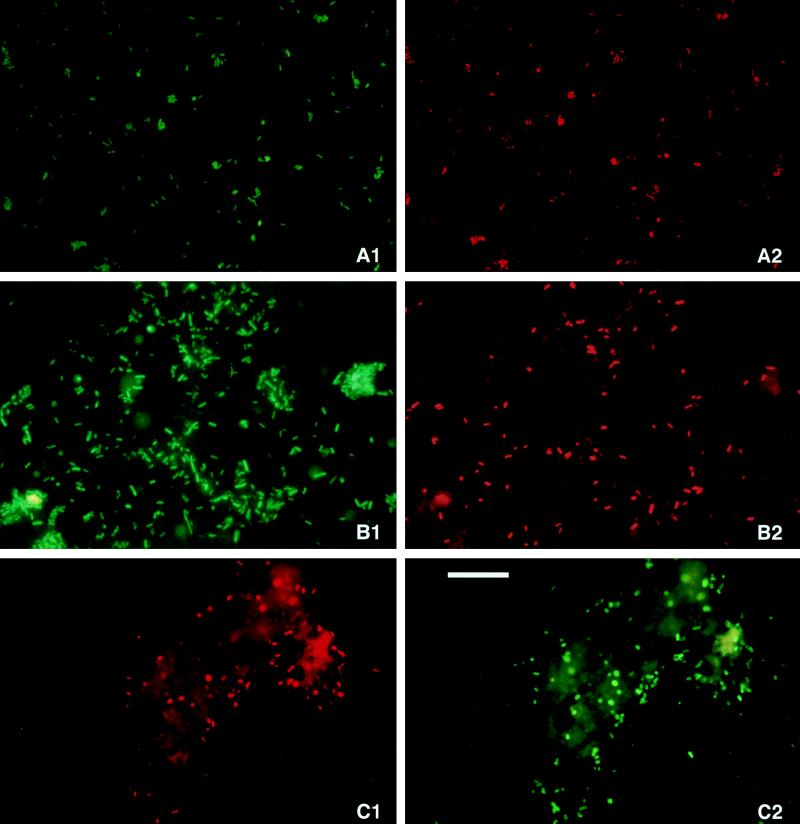

The usefulness of the designed probes in FISH detection was tested with pure cultures and potato tuber samples. Specific hybridization and high fluorescence signal with cells of R. solanacearum were observed with probe RSOLB in pure cultures and potato tuber samples (Fig. 4A and B). Unexpectedly, probe RSOLA gave a less intense signal with the same target cells. Simultaneous hybridization with probes RSOLA and RSOLB did not improve the hybridization signal. The strength of the fluorescent signal varied between individual R. solanacearum cells, probably reflecting their individual metabolic state of activity (39). Activation of the cells by incubating the samples overnight in phosphate buffer improved the fluorescence signal and occasionally also the number of cells detectable (data not shown). In experiments where FISH detection was combined with subsequent IIF detection, approximately 60% of cells reacting with the antibody were detected in FISH with probe RSOLB (Fig. 4C). Background fluorescence of organic particles in tuber extracts did not really hamper the interpretation of the microscopic observations. R. solanacearum cells (i.e., small rods of 1 to 2 μm in length) could easily be recognized between autofluorescent plant debris.

FIG. 4.

FISH detection of R. solanacearum. (A) Freshly grown pure culture (1 day in YPG medium); (B and C) naturally infected potato (S. tuberosum) tuber tissue. Hybridization was performed with the R. solanacearum-specific probe RSOLB targeted to the 23S rRNA labeled with the red excitation stain Cy3 (A2, B2, and C1), together with eubacterial probe Eub338 labeled with the green excitation stain FITC (A1 and B1). FISH detection was followed by IIF detection with a specific antibody raised against R. solanacearum labeled with FITC (C2). Scale bar (all panels), 20 μm.

FISH detection of R. solanacearum in environmental samples other than potato tissue.

In an attempt to study the survival of R. solanacearum in the environment outside its major host, potatoes, we initiated a pilot study to detect the bacterium in soil, water, and the weed host, bittersweet. By plating concentrated surface water and soil from contaminated areas on (semi-)selective medium, the FISH technique can easily be used to detect the pathogen in smears of colonies (data not shown). The pathogen was also most regularly detected in root and stem parts of bittersweet that grew along contaminated waterways.

DISCUSSION

During the last few years, an increasing number of applications of the FISH technique to detection of plant-pathogenic bacteria have been published (22, 38). We report here the successful use of FISH to detect the brown rot-causing bacterial species, R. solanacearum, in environmental samples.

As the 16S rDNA did not show sufficient sequence difference to develop a specific probe, we analyzed six 23S rDNA genes of five R. solanacearum strains and one R. pickettii strain. The topology of the unrooted tree (Fig. 1) showed a strong resemblance to similar data created with 16S rRNA sequences (20, 23, 37). These analyses confirmed that R. solanacearum strains are subdivided into two clusters. Remarkably, restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis with DNA probes showed the same two clusters (6). The sequence similarity values between R. pickettii PD1515 and the R. solanacearum clusters (with cluster 1 and 2, 99.3 and 99.0%, respectively) are higher than the value of 98.4% calculated by Xiang et al. (42) based on 16S rRNA.

The number of sequence differences found between 23S rDNA of R. solanacearum and that of R. pickettii was large enough to design specific probes. Only sequence positions that were identical for all analyzed R. solanacearum 23S rDNA sequences could be used to develop an R. solanacearum-specific probe. At only 12 sequence positions, the 23S rDNA sequence was identical for all R. solanacearum strains and different from the R. pickettii 23S rDNA sequence. It is striking that six differences are present in two complementary triplet nucleotides, both part of a stem loop structure in region II, separated by approximately 140 nucleotides. The likelihood that other species possess these substitutions is rather low. By using these triplet nucleotides, two specific probes (RSOLA and RSOLB) could be developed. When the two probes were hybridized with RNA isolated from 88 strains of different species, they appeared to be very specific. Only the closely related plant pathogens R. syzygii and BLDB strains could not be distinguished from the R. solanacearum strains by using the probes RSOLA and RSOLB. However, both species have been recorded only in Indonesia, associated with diseases of cloves (Syzygium sp.) and bananas, respectively. Similar findings were made by Seal et al. (34) with 16S rRNA sequences. The probes are therefore considered to be useful in FISH detection of R. solanacearum, but further evaluation of specificity, by using field samples, is necessary. RSOLA and RSOLB both gave equal hybridization signals in dot blots of equal strength. However, in whole-cell experiments, probe RSOLA showed a much weaker hybridization signal than did probe RSOLB; the latter was therefore used in FISH experiments. The difference in hybridization efficiency between the probes in whole-cell experiments may be due to steric hindrance of the probe-target binding site (13). Probes RSOLB and EUB338 gave a strong signal with cells grown in pure culture and with cells in naturally infected potato tubers.

The FISH technique is valuable not only for guaranteeing a better export quality of seed potatoes but also in studying the epidemiology of the pathogen and tracing the ecological niches where the bacteria can survive. Our FISH observations confirm the results of previous studies that the bacteria are present in soil from contaminated potato fields and in surface water from agricultural areas (9, 19). Application of FISH therefore is very helpful in understanding the survival and spread of the bacteria in contaminated soil and water. It will therefore be a good alternative to PCR and IIF, which are normally used for verification. In addition, the FISH technique confirmed that the bacteria occur most frequently in a latent form in bittersweet and are not easily isolated from this host (18). Application of FISH could therefore be very helpful in studying the epidemiology of brown rot disease in latently infected weed hosts.

The subsequent application of FISH and IIF detection in potato tuber tissue showed that, of all cells reacting with the specific antibody, approximately 60% also gave a fluorescent signal in FISH detection. This percentage is low in comparison with the value of more than 90% obtained by Li et al. (22) with pure cultures of Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus. Potato tuber tissue samples that were used in our experiments were stored at −20°C for more than 1 year; this can result in significant rRNA degradation of individual cells. Also, a low state of activity of individual cells will result in a low rRNA content in the cells (3, 39). Cells of low activity will therefore give a weak visual fluorescent signal, or none, in FISH experiments. In IIF detection, the polyclonal antibody will react with all cells, active or inactive, or even dead cells. Also, cells cross-reacting with the polyclonal antibody will influence this ratio. In FISH, the presence of dead or inactive cells will influence the detection limit of this technique compared to that of IIF. In certain cases (i.e., old samples), the number of detectable viable cells in FISH can be improved by activating the bacteria (27).

By simultaneously applying IIF and FISH to detect R. solanacearum, two independent targets for identification are combined. This could result in a very accurate identification of specific cells, improving the reliability of diagnosis. The FISH detection procedure for R. solanacearum can be completed in 1 day. This FISH test can therefore assist in reducing the number of false-positive reactions when it is used after the IIF screening. Only a very small number of samples would have to be subjected to further confirmatory tests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Arable Sector and the Dutch Potato Industries in particular. We thank Hans Derks (Plant Protection Service, Wageningen, The Netherlands) for helping us with the strain collection, Jan van der Wolf (IPO, Wageningen, The Netherlands) for providing us with some bacterial strains, Wilma Akkermans for assisting with sequence analysis, and Hugo Ramirez-Saad and Willem de Vos for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann R I, Binder B J, Olson R J, Chisholm S W, Devereux R, Stahl D A. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1919–1925. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1919-1925.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R I, Krumholz L, Stahl D A. Fluorescent-oligonucleotide probing of whole cells for determinative, phylogenetic, and environmental studies in microbiology. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:762–770. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.762-770.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann R I, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anonymous. Quarantine procedure no. 26. Pseudomonas solanacearum. Bull OEPP. 1992;20:255–262. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brosius J, Dull T J, Noller H F. Complete nucleotide sequence of the 23S ribosomal RNA gene from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:201–204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.1.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook D, Barlow E, Sequeira L. Genetic diversity of Pseudomonas solanacearum: detection restriction fragment length polymorphisms with DNA probes that specify virulence and the hypersensitive response. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1989;2,3:113–121. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eden-Green S J, Sastraatmadja H. Blood disease present in Java. FAO Plant Prot Bull. 1990;38:49–50. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elphinstone J G, Hennessy J, Wilson J K, Stead D E. Sensitivity of different methods for the detection of Ralstonia solanacearum in potato tuber extracts. Bull OEPP. 1996;26:663–678. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elphinstone J G, Stanford J G H, Stead D E. Detection of Ralstonia solanacearum in potato tubers, Solanum dulcamara, and associated irrigation water. In: Prior P, Allen C, Elphinstone J G, editors. Bacterial wilt disease: molecular and ecological aspects. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1998. pp. 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engelbrecht M C. Modifications of a semi-selective medium for the isolation of Pseudomonas solanacearum. Bact Wilt Newsl. 1994;10:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP phylogenetic inference package version 3.5.1. Seattle: Department of Genetics, University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felske A, Engelen B, Nübel U, Backhaus H. Direct ribosome isolation from soil to extract bacterial rRNA for community analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4162–4167. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4162-4167.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frischer M E, Floriani P J, Nierzwicki-Bauer S A. Differential sensitivity of 16S rRNA targeted oligonucleotide probes used for fluorescence in situ hybridization is a result of ribosomal higher order structure. Can J Microbiol. 1996;42:1061–1071. doi: 10.1139/m96-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayward A C. Biology and epidemiology of bacterial wilt caused by Pseudomonas solanacearum. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1991;29:65–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.29.090191.000433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Höpfl P, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H, Larsen N. The 23S ribosomal RNA higher-order structure of Pseudomonas cepacia and other prokaryotes. Eur J Biochem. 1989;185:355–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janse J D. A detection method for Pseudomonas solanacearum in symptomless potato tubers and some data on its sensitivity and specificity. Bull OEPP. 1988;18:343–351. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janse J D. Infra- and intraspecific classification of Pseudomonas solanacearum strains, using whole cell fatty acid analysis. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1991;12:335–345. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janse J D. Potato brown rot in western Europe—history, present occurrence and some remarks on possible origin, epidemiology and control strategies. Bull OEPP. 1996;26:679–695. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janse J D, Araluppan F A X, Schaus J, Wennekers M, Westerhuis W. Experiences with bacterial brown rot Ralstonia solanacearum biovar 2, race 3 in The Netherlands. In: Prior P, Allen C, Elphinstone J G, editors. Bacterial wilt disease: molecular and ecological aspects. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1998. pp. 146–152. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kersters K, Ludwig W, Vancanneyt M, De Vos P, Gillis M, Schleifer K-H. Recent changes in the classification of Pseudomonas: an overview. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19:465–477. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lane D J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons; 1991. pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, De Boer S H, Ward L J. Improved microscopic identification of Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus cells by combining in situ hybridization with immunofluorescence. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1997;24:431–434. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1997.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X, Dorsch M, Del Dot T, Sly L I, Stackebrandt E, Hayward A C. Phylogenetic studies of the rRNA group II pseudomonads based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. J Appl Bacteriol. 1993;74:324–329. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ludwig W, Kirchhof G, Klugbauer N, Weizenegger M, Betzl D, Ehrmann M, Hertel C, Jilg S, Tatzel R, Zitzelsberger H, Liebl S, Hochberger M, Shah J, Lane D, Wallnöfer P R, Schleifer K-H. Complete 23S ribosomal RNA sequences of gram-positive bacteria with a low DNA G+C content. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992;15:487–501. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludwig W, Rosselló-Mora R, Aznar R, Klugbauer S, Spring S, Reetz K, Beimfohr C, Brockmann E, Kirchhof G, Dorn S, Bachleither M, Klugbauer N, Springer N, Lane D, Nietupsky R, Weizenegger M, Schleifer K-H. Comparative sequence analysis of 23S rRNA from Proteobacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1995;18:164–188. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maggia L, Nazaret S, Simonet P. Molecular characterization of Frankia isolates from Casuarina equisitifolia root nodules harvested in West Africa (Senegal and Gambia) Acta Oecol. 1992;13:453–461. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ouverney C C, Fuhrman J A. Increase in fluorescence intensity of 16S rRNA in situ hybridization in natural samples treated with chloramphenicol. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2735–2740. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2735-2740.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palleroni N J. Genus I. Pseudomonas. In: Krieg N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1984. pp. 141–199. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palleroni N J, Kunisawa R, Contopoulou R, Doudoroff M. Nucleic acid homologies in the genus Pseudomonas. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1973;23:333–339. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ralston E, Palleroni N J, Doudoroff M. Pseudomonas pickettii, a new species of clinical origin related to Pseudomonas solanacearum. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1973;23:15–19. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts S J, Eden-Green S J, Jones P, Ambler D J. Pseudomonas syzygii, sp. nov., the cause of Sumatra disease of cloves. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1990;13:34–43. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seal S E, Jackson L A, Young J P W, Daniels M J. Differentiation of Pseudomonas solanacearum, Pseudomonas syzygii, Pseudomonas pickettii and Blood Disease Bacterium by partial 16S rRNA sequencing: construction of oligonucleotide primers for sensitive detection by polymerase chain reaction. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1587–1594. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-7-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skulachev V P. Multiple alignment. Moscow, Russia: Belozersky Institute of Physico-Chemical Biology, Moscow State University; 1997. http://www.genebee.msu.su/services/malignreduced.html [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strunk O, Ludwig W. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Munich, Germany: Department of Microbiology, Technical University of Munich; 1995. http://www.mikro.biologie.tu-muenchen.de [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taghavi M, Hayward C, Sly L I, Fegan M. Analysis of the phylogenetic relationships of strains of Burkholderia solanacearum, Pseudomonas syzygii, and the blood disease bacterium of banana based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:10–15. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Beuningen A, Derks H, Janse J. Proceedings of International Symposium of 75 Years of Phytopathological and Resistance Research 1995. Aschersleben, Germany: Bundesanstalt für Züchtungsforschung an Kulturpflanzen; 1995. Detection and identification of Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus with special attention to fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH) using 16S rRNA targeted oligonucleotide probe H-2; pp. 266–269. [Google Scholar]

- 38a.van der Wolf, J. Unpublished results.

- 39.Wagner R. The regulation of ribosomal RNA synthesis and bacterial cell growth. Arch Microbiol. 1994;161:100–109. doi: 10.1007/BF00276469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woese C R. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:221–271. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Worley K C, Smidt R, Wiese B, Culpepper P. The BCM search launcher, Human Genome Center, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics. Houston, Tex: Baylor College of Medicine; 1998. http://kiwi.imgenbcm.tmc.edu:8088/search-launcher/launcher.html . [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiang L, Dorsch M, Del Dot T, Sly L I, Stackebrandt E, Hayward A C. Phylogenetic studies of the rRNA group II pseudomonads based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. J Appl Bacteriol. 1993;74:324–329. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yabuuchi E, Kosako Y, Oyaizu H, Yano I, Hotta H, Hashimoto Y, Ezaki T, Arakawa M. Proposal of Burkholderia gen. nov. and transfer of seven species of the genus Pseudomonas group II to the new genus, with the type species Burkholderia cepacia (Palleroni & Holmes, 1981) comb. nov. Microbiol Immunol. 1992;36:1251–1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1992.tb02129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yabuuchi E, Kosako Y, Yano I, Hotta H, Nishiuchi Y. Transfer of two Burkholderia and an Alcaligenes species to Ralstonia gen. nov.: proposal of Ralstonia pickettii (Ralston, Palleroni and Doudoroff 1973) comb. nov., Ralstonia solanacearum (Smith 1896) comb. nov. and Ralstonia eutropha (Davis 1969) comb. nov. Microbiol Immunol. 1995;39:897–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb03275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]