Abstract

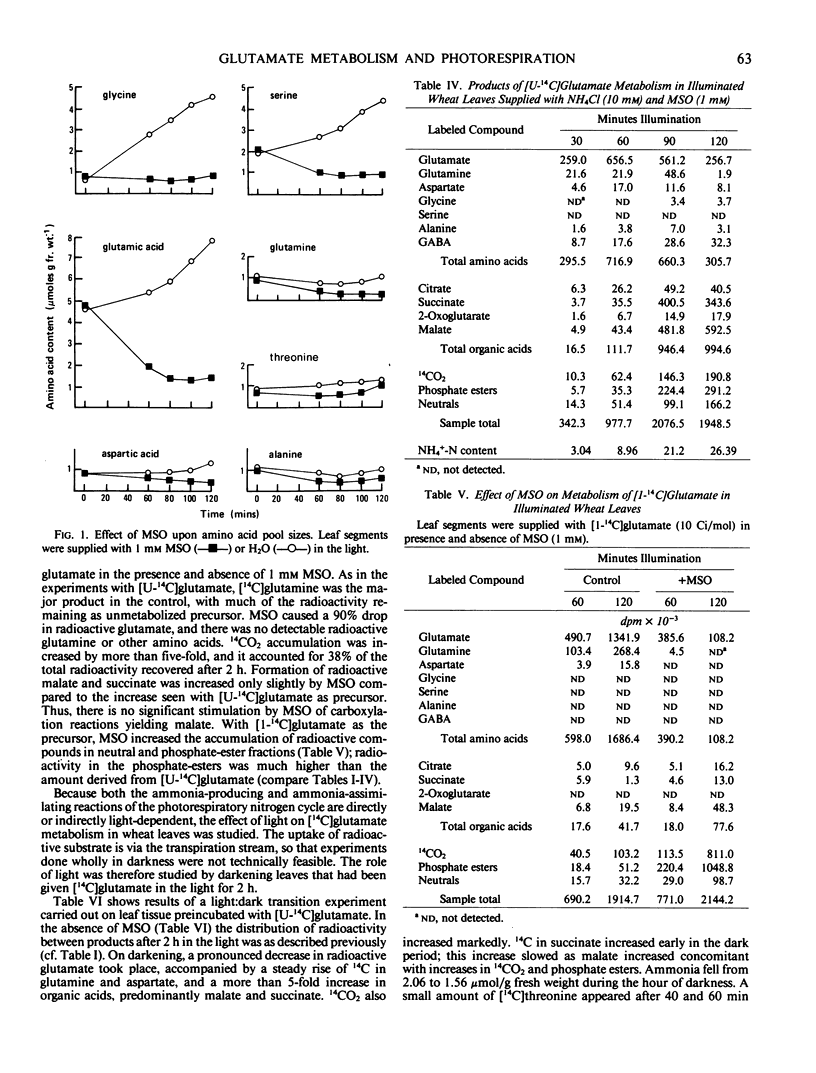

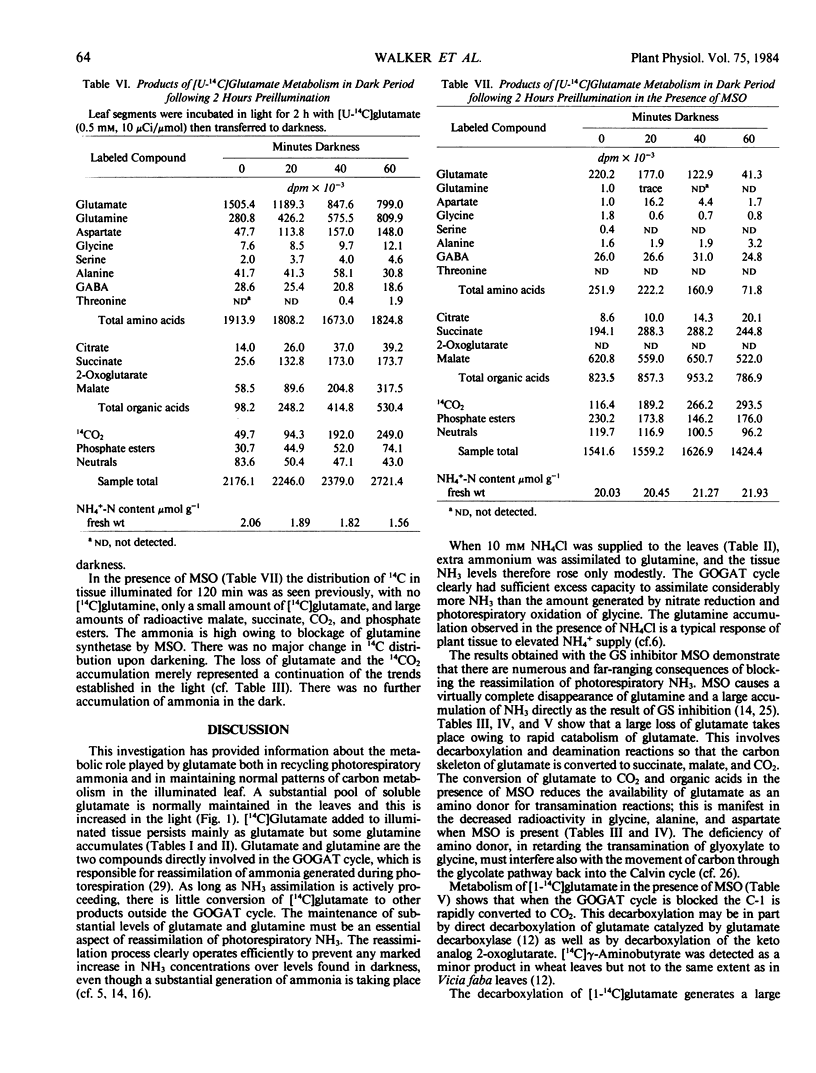

The effects of methionine sulfoximine and ammonium chloride on [14C] glutamate metabolism in excised leaves of Triticum aestivum were investigated. Glutamine was the principal product derived from [U14C]glutamate in the light and in the absence of inhibitor or NH4Cl. Other amino acids, organic acids, sugars, sugar phosphates, and CO2 became slightly radioactive. Ammonium chloride (10 mm) increased formation of [14C] glutamine, aspartate, citrate, and malate but decreased incorporation into 2-oxoglutarate, alanine, and 14CO2. Methionine sulfoximine (1 mm) suppressed glutamine synthesis, caused NH3 to accumulate, increased metabolism of the added radioactive glutamate, decreased tissue levels of glutamate, and decreased incorporation of radioactivity into other amino acids. Methionine sulfoximine also caused most of the 14C from [U-14C]glutamate to be incorporated into malate and succinate, whereas most of the 14C from [1-14C]glutamate was metabolized to CO2 and sugar phosphates. Thus, formation of radioactive organic acids in the presence of methionine sulfoximine does not take place indirectly through “dark” fixation of CO2 released by degradation of glutamate when ammonia assimilation is blocked. When illuminated leaves supplied with [U-14C] glutamate without inhibitor or NH4Cl were transferred to darkness, there was increased metabolism of the glutamate to glutamine, aspartate, succinate, malate, and 14CO2. Darkening had little effect on the labeling pattern in leaves treated with methionine sulfoximine.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ATFIELD G. N., MORRIS C. J. Analytical separations by highvoltage paper electrophoresis. Amino acids in protein hydrolysates. Biochem J. 1961 Dec;81:606–614. doi: 10.1042/bj0810606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azcón-Bieto J., Lambers H., Day D. A. Effect of photosynthesis and carbohydrate status on respiratory rates and the involvement of the alternative pathway in leaf respiration. Plant Physiol. 1983 Jul;72(3):598–603. doi: 10.1104/pp.72.3.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dry I. B., Wiskich J. T. Role of the external adenosine triphosphate/adenosine diphosphate ratio in the control of plant mitochondrial respiration. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1982 Aug;217(1):72–79. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(82)90480-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz T. A., Peterson D. M., Durbin R. D. Sources of ammonium in oat leaves treated with tabtoxin or methionine sulfoximine. Plant Physiol. 1982 Feb;69(2):345–348. doi: 10.1104/pp.69.2.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan B. R., Givan C. V. Effects of Light and Inhibitors on Glutamate Metabolism in Leaf Discs of Vicia faba L: Sources of ATP for Glutamine Synthesis and Photoregulation of Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Metabolism. Plant Physiol. 1979 Dec;64(6):1043–1047. doi: 10.1104/pp.64.6.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea P. J., Miflin B. J. Alternative route for nitrogen assimilation in higher plants. Nature. 1974 Oct 18;251(5476):614–616. doi: 10.1038/251614a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin F., Winspear M. J., Macfarlane J. D., Oaks A. Effect of Methionine Sulfoximine on the Accumulation of Ammonia in C(3) and C(4) Leaves : The Relationship between NH(3) Accumulation and Photorespiratory Activity. Plant Physiol. 1983 Jan;71(1):177–181. doi: 10.1104/pp.71.1.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough H. The determination of ammonia in whole blood by a direct colorimetric method. Clin Chim Acta. 1967 Aug;17(2):297–304. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(67)90133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally S. F., Hirel B., Gadal P., Mann A. F., Stewart G. R. Glutamine Synthetases of Higher Plants : Evidence for a Specific Isoform Content Related to Their Possible Physiological Role and Their Compartmentation within the Leaf. Plant Physiol. 1983 May;72(1):22–25. doi: 10.1104/pp.72.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redgwell R. J. Fractionation of plant extracts using ion-exchange Sephadex. Anal Biochem. 1980 Sep 1;107(1):44–50. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90489-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed A. J., Canvin D. T. Light and Dark Controls of Nitrate Reduction in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Protoplasts. Plant Physiol. 1982 Feb;69(2):508–513. doi: 10.1104/pp.69.2.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville S. C., Ogren W. L. An Arabidopsis thaliana mutant defective in chloroplast dicarboxylate transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Mar;80(5):1290–1294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.5.1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo K. C., Morot-Gaudry J. F., Summons R. E., Osmond C. B. Evidence for the Glutamine Synthetase/Glutamate Synthase Pathway during the Photorespiratory Nitrogen Cycle in Spinach Leaves. Plant Physiol. 1982 Nov;70(5):1514–1517. doi: 10.1104/pp.70.5.1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]