Abstract

We sequenced the pepP gene of Lactococcus lactis, which encodes an aminopeptidase P (PepP), and demonstrated that the X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase PepX plays a more important role than PepP in nitrogen nutrition. PepP shares homology with methionine aminopeptidases and could play a role in the maturation of nascent proteins.

The proteolytic system of lactic acid bacteria is involved in two major events during the technological use of the bacteria. First, it ensures the nitrogen nutrition in hydrolyzing caseins (15). Second, during cheese ripening, it contributes to the development of flavor by releasing free amino acids which are precursors of aromatic compounds (42). In addition, although it is poorly documented, the proteolytic system of lactic acid bacteria is involved in more physiological and universal functions such as protein turnover, protein maturation, signal peptide processing, degradation of abnormal proteins, and inactivation of regulatory proteins (17).

Since milk contains only small amounts of free amino acids and small peptides, the optimal growth of lactococci in milk depends on the hydrolysis of caseins. This is accomplished by the primary action of an extracellular cell wall proteinase which hydrolyzes caseins into oligopeptides. The oligopeptides are transported into bacteria, where they are further hydrolyzed by intracellular peptidases (15). The high proline content of caseins limits the efficiency of the proteolytic system in releasing free amino acids. Most of the peptidases with general specificity are indeed unable to hydrolyze peptide bonds involving proline. Thus, the proline-specific peptidases already identified in lactococci probably play a major role in casein breakdown.

The X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase (PepX; EC 3.4.14.5; able to release X-Pro dipeptides from the N-terminal end of peptide chains) is the most-studied proline-specific peptidase in lactococci. PepX of Lactococcus lactis was purified and characterized (4, 14, 18, 41, 43, 46), and its gene was cloned and sequenced (23, 32). In addition to PepX, an aminopeptidase P (PepP; EC 3.4.11.9) was purified and characterized in L. lactis (21, 24). This intracellular metalloenzyme releases N-terminal amino acids when proline is in the penultimate position. Moreover, it displays a specificity for X-Pro-Pro N termini, which constitutes an original property since it is not found in other aminopeptidases P already described.

According to their complementary specificities, PepP and PepX were considered peptidases that are able to initiate the degradation of proline-containing peptides in two different pathways (5), but their relative importance in this degradation remains unknown.

To evaluate the role of the two proline-specific aminopeptidases, PepP and PepX, in nitrogen nutrition, we cloned and sequenced the pepP gene and constructed mutants negative for PepP and PepX as well as a PepX−-PepP− double mutant. We demonstrated that, unlike PepX, PepP did not play a major role in nitrogen nutrition and probably had another specific function in bacteria.

The chromosomal gene pepP encodes an intracellular aminopeptidase P.

We characterized the pepP gene encoding the lactococcal aminopeptidase P in L. lactis NCDO763 in a two-step procedure. First we identified the pepP gene; then we sequenced it and its flanking sequences. To identify the pepP gene, we purified PepP (21) and, after protein electrophoresis (16) and Western blotting (22), we determined its N-terminal sequence: Met-Arg-Ile-Glu-Lys-Leu-Lys-Val-Lys-Met-Leu-Thr-Glu-Asn-Ile-Lys-Ser-Leu-Leu-Ile-Thr-Asp-Met-Lys-Asn-Ile-Phe-Tyr-Leu-Thr (model 477A; Applied Biosystems, San Jose, Calif.). From the N-terminal sequence of PepP, we amplified with degenerate oligonucleotides a DNA fragment which was further cloned into pBluescript SK(+) (Table 1) and sequenced (373 DNA sequencer; Applied Biosystems). From this fragment, a 1.63-kb DNA sequence containing the whole pepP gene and two incomplete open reading frames (ORF1 and ORF3) was amplified by inverse PCR and sequenced. pepP encodes a protein with a molecular mass of 46 kDa, which is in accordance with the molecular mass of the purified protein PepP. Moreover, the N-terminal sequence of the protein deduced from the gene is identical to that sequenced from the protein, which shows that PepP is not subjected to any maturation at its N-terminal part. In addition, we did not find any typical hydrophobic sequence encoding a putative signal sequence which confirmed the intracellular location of PepP (21). A consensus ribosome-binding site (19) was found 6 bp upstream of the ATG start codon of pepP and was found to have a ΔG of −13.8 kcal/mol. In the whole nucleotide sequence, only one putative terminator structure was found downstream of ORF1. Close to the latter and upstream of pepP, a potential −10 extended promoter structure, fitting rather well with that observed in Streptococcus pneumoniae (37), was found. Another potential promoter was observed upstream of ORF3. The absence of a putative terminator downstream of pepP suggested that the gene encoding the aminopeptidase P belongs to an operon. pepP was similarly amplified from L. lactis NCDO763 and from L. lactis MG1363 (plasmid-free strain), which demonstrated its chromosome localization.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant phenotype or genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| L. lactis subsp. cremoris | ||

| NCDO763 | Wild-type strain | 8 |

| TIL46 | 2-kb plasmid-free derivative of NCDO763 | 29 |

| MG1363 | Plasmid-free derivative of NCDO712 | 11 |

| TIL54 | Tcr, Emr, derivative of TIL46 containing pTIL18B | This work |

| TIL55 | Tcr, PepX− derivative of TIL54 | This work |

| TIL200 | Apr, Emr, PepP− derivative of TIL46 | This work |

| TIL201 | Apr, Emr, Tcr, PepP−-PepX− derivative of TIL46 | This work |

| Escherichia coli TG1 | 12 | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript SK(+) | Apr, M13 ori,a pBr322 ori | Stratagene (La Jolla, Calif.) |

| pTAg | Apr, Kmr | R&D Systems |

| pG+host4 | Emr, ori thermosensitive,b 3.8 kb | 20 |

| pIL253 | Emr, 4.9 kb | 39 |

| pTIL16 | Apr, pepX in pBluescript SK(+), 5.2 kb | This work |

| pTIL18A | Apr, Tcr, integration of Tc cassette in pepX (BglII site of pTIL16), 9.2 kb | This work |

| pTIL18B | Tcr, Emr, cloning the interrupted pepX gene in BamHI and XhoI sites of pG+host4, 11.8 kb | This work |

| pTIL101 | Apr, pepP fragment in pTAg, 4.5 kb | This work |

| pTIL102 | Apr, Emr, Sau3A fragment of pIL253 in pepP (BamHI site of pTIL101), 5.7 kb | This work |

| pTIL131 | Apr, pepP N-terminal part in pBluescript SK(+), 3 kb | This work |

ori, origin of replication.

Contains the E. coli thermosensitive origin of replication.

PepP belongs to the methionine aminopeptidase family.

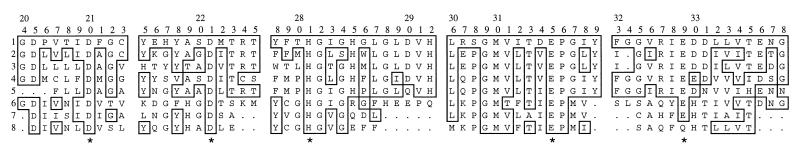

In order to identify similar proteins, the EMBL, GenBank, and DDBJ databases were screened with the deduced ORF1, PepP, and ORF3 amino acid sequences. PepP displays a significant homology with other aminopeptidases P, prolidases, and methionine aminopeptidases, which all belong to the M24 family of metallopeptidases (35). The highest homologies were found with potential aminopeptidase P from Bacillus subtilis (44% identity) (28), Mycoplasma genitalium (32% identity) (10), and Haemophilus influenzae (31% identity) (9) and with prolidase from Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis (33% identity) (40). The highest homology with methionine aminopeptidases was obtained with those from M. genitalium (10), Salmonella typhimurium (30), and B. subtilis (31) (24 to 25% identity). PepP also showed homologies with creatinase from Pseudomonas putida (31% identity) (7), which has been shown to have a tertiary fold similar to that of the methionine aminopeptidase from Escherichia coli (2), although it is neither a peptidase nor a metal-dependent enzyme. The Asp 210, Asp 221, His 281, Glu 315, and Glu 329 residues were identified as potential metal ligands of the PepP protein of L. lactis, and the sequences around them are well conserved (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Conservation of sequences around the cobalt ligands of the methionine aminopeptidase family (M24). Residues are numbered according to L. lactis aminopeptidase P. The cobalt ligands identified in E. coli methionine aminopeptidase (36) are indicated with asterisks. Residues identical to those in L. lactis aminopeptidase P are boxed. 1, L. lactis aminopeptidase P; 2, E. coli aminopeptidase P; 3, Streptomyces lividans aminopeptidase P; 4, human prolidase; 5, E. coli prolidase; 6, E. coli methionine aminopeptidase; 7, B. subtilis methionine aminopeptidase; 8, yeast methionine aminopeptidase.

Significant homologies were found for the proteins encoded by ORF1 (70-amino-acid sequence length) and ORF3 (39-amino-acid sequence length), although they were deduced from partial amino acid sequences. The protein encoded by ORF1 presents a significant homology with kasugamycin dimethyladenosine transferases of B. subtilis (45% identity) (33) and Mycoplasma capricolum (32% identity) (27). The ORF3 product displays a homology with the elongation factor P (EF-P) of Corynebacterium glutamicum (39.5% identity) (34) and the same putative factor of B. subtilis (44% identity) (28). The fact that a gene homologous to the L. lactis NCDO763 pepP gene was found in all the lactococcal strains tested, including those of plant origin, and in many other bacteria—especially M. genitalium, which possesses the smallest genome sequenced (10)—indicated that PepP could play a universal role in bacteria. The presence, downstream of pepP, of a gene coding for a protein homologous to an EF-P from E. coli (1) suggested a possible role of PepP during protein synthesis. Interestingly, in B. subtilis, the same organization was recently found: a gene encoding a protein 44% identical to PepP was followed by a gene encoding a protein 43% identical to the EF-P from E. coli (28).

PepP is widespread in L. lactis strains.

Southern hybridization experiments under low-stringency conditions (20% formamide) (38) with a pepP probe revealed the presence of genes homologous to pepP in the seven lactococcal strains tested (L. lactis NCDO763, Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis IL1403, Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363, Wg2, AM2, and E8, and L. lactis subsp. lactis CNRZ2118, of plant origin). However, no signal was visible for the other lactic acid bacteria tested: Streptococcus thermophilus CNRZ302, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus ATCC 11842, Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei CNRZ62, Lactobacillus helveticus CNRZ223, and Lactobacillus plantarum CNRZ1008.

Unlike PepX, PepP does not affect lactococcal growth in milk.

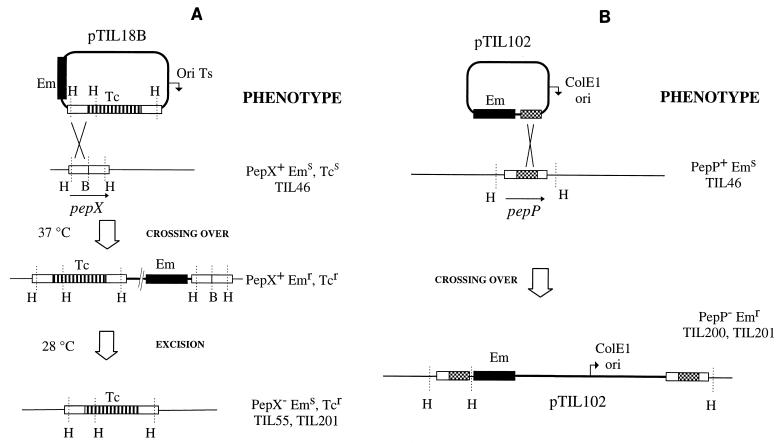

To investigate whether PepP is important and/or complementary to PepX during growth of L. lactis, we constructed PepP, PepX, and a double PepP-PepX-negative mutant (Table 1). The integration vectors pTIL18B and pTIL102 were used to disrupt pepX and pepP genes in the TIL46 strain, respectively (Fig. 2). The disruptions of pepP and pepX were checked by Southern hybridization. The analysis of the plasmid profile of all mutated strains confirmed their L. lactis TIL46 origin (data not shown). The levels of PepP and PepX activities were measured in cell extracts of negative mutants and wild-type strains (50 mM TEA-HCl buffer, pH 7, 30°C). The increase in fluorescence (λex = 320 nm, λem = 417 nm) due to hydrolysis of Lys(Abz)-Pro-Pro-pNa (Bachem) by PepP and the increase of absorbance (405 nm) due to hydrolysis of Ala-Pro-pNa by PepX were totally lost in PepP- and PepX-negative mutants, respectively. The maximal growth rates in M17 at 30°C, assessed by spectrophotometric measurements at 450 nm (CERES900; BioTek Instruments, Winooski, Vt.), were similar for the wild-type strain and PepP- and/or PepX-negative mutants. The maximal growth rates in milk at 30°C, assessed by enumeration with a spiral system (model DS; Spiral System, Cincinnati, Ohio), were 0.93 ± 0.09 h−1 for the wild type, 0.89 ± 0.07 for the PepP− mutant, 0.70 ± 0.15 for the PepX− mutant, and 0.68 ± 0.11 for the PepP−-PepX− mutant. We observed that in milk the growth of the PepX-negative mutant was slightly but clearly affected, as already observed by Mierau et al. (25). In contrast, the PepP-negative mutant did not grow significantly slower than the wild-type strain. This indicated that PepP did not play a major role in the nitrogen nutrition of lactococci. This conclusion challenges the model of prolyl peptide degradation proposed by Booth et al. (5), who hypothesized that the X-Pro-Y-Z- peptides could be hydrolyzed either by PepX or by PepP. The absence of any effect of PepP deficiency both in the wild-type strain and in the PepX-negative mutant indicated that PepP is not involved in the degradation of casein-derived prolyl peptides during growth in milk. Consequently, we postulated that PepP had another function in lactococci.

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the integrations of the tetracycline resistance cassette into the pepX gene (A) and of the plasmid pTIL102 into the pepP gene (B). Both genes are indicated by empty bars, and the internal fragment of the pepP gene used for the integration is shown by a dotted bar. The arrows in plasmids pTIL18B and pTIL102 indicate the E. coli thermosensitive origin of pG+host4 and the E. coli origin of replication of the pTAg plasmid, respectively. The relevant phenotypes of the clones are indicated on the right. H, HindIII restriction site; B, BglII restriction site.

PepP liberates N-terminal methionine.

To investigate whether PepP is able to release the N-terminal methionine when proline is in the penultimate position, the peptides Arg-Pro-Pro-Gly-Phe (the best substrate among those previously tested [21]), Met-Pro-Pro-Gly-Phe, and Met-Gly-Gly-Gly-Phe were synthesized (Applied Biosystems 432A synergy peptide synthesizer; Perkin-Elmer, San Jose, Calif.) and tested as substrates. They were incubated at 37°C in 50 mM TEA-HCl buffer (pH 7) (0.5 mM final concentration) with a partially purified fraction of aminopeptidase P (50% pure) containing none of the other already-characterized lactococcal peptidases. The release of Met from Met-Pro-Pro-Gly-Phe was twofold faster than that of Arg from Arg-Pro-Pro-Gly-Phe, which demonstrated that Met-Pro-Pro-Gly-Phe is a good substrate for PepP. The absence of hydrolysis of Met from Met-Gly-Gly-Gly-Phe confirmed the proline-specific property of PepP (21), as already shown with PepP from E. coli (44). Although the physiological role of N-terminal methionine hydrolysis from proteins is not completely understood, it is well established that the amino-terminal methionine is removed enzymatically after the initiation of the translation of intracellular proteins. Methionine is hydrolyzed by a methionine aminopeptidase (PepM), and the extent of methionine release depends on the nature of the second amino acid (13). PepM easily liberates methionine when a proline is in the penultimate position, but in vitro and in vivo experiments showed that a proline in the third position inhibits PepM activity (3, 13). PepP can help to increase the efficiency of release of the N-terminal methionine, as shown in in vivo experiments with PepP from E. coli (45). In an E. coli strain overproducing PepP and expressing human interleukin-6 (with a Met-Pro- N-terminal sequence), the rate of removal of the initial methionine is 99% compared to a rate of 85% in a strain in which the PepP is not overproduced. This observation demonstrated that the PepP could play a role in the maturation of nascent proteins. PepP never replaces PepM, since PepM is essential for bacterial cell growth (6, 26), but may play a role in the maturation of specific proteins.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank, EMBL, and DDBJ nucleotide sequence accession number is Y08842.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by European Community grant BIO2-CT-94-6387 and contract ERBBIO4CT960016.

We thank Patricia Anglade for N-terminal protein sequencing, Christian Ouali for peptide synthesis, Vincent Juillard for his help and advice in the measurements of bacterial growth rates, and Pierre Renault, Françoise Rul, Emmanuelle Maguin, and Patrick Taillez for gifts of lactic acid bacterium DNA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoki H, Adams S-L, Chung D-G, Yaguchi M, Chuang S-E, Ganoza M C. Cloning, sequencing and overexpression of the gene for prokaryotic factor EF-P involved in peptide bond synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6215–6220. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.22.6215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bazan J F, Weaver L H, Roderick S L, Huber R, Matthews B W. Sequence and structure comparison suggest that methionine aminopeptidase, prolidase, aminopeptidase P, and creatinase share a common fold. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2473–2477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Bassat A, Bauer K, Chang S-Y, Myambo K, Boosman A, Chang S. Processing of the initiation methionine from proteins: properties of the Escherichia coli methionine aminopeptidase and its gene structure. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:751–757. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.2.751-757.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Booth M, Fhaolain I N, Jennings P V, O’Cuinn G. Purification and characterization of a post-proline dipeptidyl aminopeptidase from Streptococcus cremoris AM2. J Dairy Res. 1990;57:89–99. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booth M, Donnelly W J, Fhaolain I N, Jennings P V, O’Cuinn G. Proline-specific peptidases of Streptococcus cremoris AM2. J Dairy Res. 1990;57:79–88. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang S-Y P, McGary E C, Chang S. Methionine aminopeptidase gene of Escherichia coli is essential for cell growth. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4071–4072. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.4071-4072.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coll M, Knof S H, Ohoga Y, Messerschmidt A, Huber R, Moellering H, Rüssmann L, Schumacher G. Enzymatic mechanism of creatine amidinohydrolase as deduced from crystal structures. J Mol Biol. 1990;214:597–610. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90201-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies F L, Underwood H M, Gasson M J. The role of plasmid profiles for strain identification in lactic streptococci and the relationship between Streptococcus lactis 712, ML3 and C2. J Appl Bacteriol. 1981;51:325–337. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, et al. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraser C M, Gocayne J D, White O, Adams M D, Clayton R A, Fleischmann R D, Bult C J, Kerlavage A R, Sutton G, Kelley J M, et al. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science. 1995;270:397–403. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gasson M J. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO 712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast-induced curing. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:1–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.1-9.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson T J. Studies on the Epstein-Barr virus genome. Ph.D. thesis. Cambridge, England: University of Cambridge; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirel P-H, Schmitter J-M, Dessen P, Fayat G, Blanquet S. Extent of N-terminal methionine excision from Escherichia coli proteins is governed by side-chain length of the penultimate amino acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8247–8251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiefer-Partsch B, Bockelmann W, Geis A, Teuber M. Purification of an X-prolyl-dipeptidyl aminopeptidase from the cell wall proteolytic system of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1989;31:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kunji E R S, Mierau I, Hagting A, Poolman B, Koonings W N. The proteolytic system of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:187–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00395933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazdunski A M. Peptidases and proteases of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1989;63:265–276. doi: 10.1016/0168-6445(89)90035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lloyd R J, Pritchard G G. Characterization of X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis H1. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludwig W, Seewaldt E, Klipper-Bälz R, Schleiffer K H, Magrum L, Woese C R, Fox G E, Stackebrandt E. The phylogenetic of Streptococcus and Enterococcus. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:543–551. doi: 10.1099/00221287-131-3-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maguin E, Duwat P, Hege T, Ehrlich D, Gruss A. New thermosensitive plasmid for gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5633–5638. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.17.5633-5638.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mars I, Monnet V. An aminopeptidase P from Lactococcus lactis with original specificity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1243:209–215. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(94)00028-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsudaira P. The sequence from picomole quantities of proteins electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10035–10038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayo B, Kok J, Venema K, Bockelmann W, Teuber M, Reinke H, Venema G. Molecular cloning and sequencing analysis of the X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase gene from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:38–44. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.38-44.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonnell M, Fitzgerald R, Fhaolain I N, Jennings P V, O’Cuinn G. Purification and characterization of aminopeptidase P from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris. J Dairy Res. 1997;64:399–407. doi: 10.1017/s0022029997002318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mierau I, Kunji E R S, Leenhouts K J, Hellendoorn M A, Haandrikman A J, Poolman B, Konings W N, Venema G, Kok J. Multiple-peptidase mutants of Lactococcus lactis are severely impaired in their ability to grow in milk. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2794–2803. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2794-2803.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller C G, Kukral A M, Miller J L, Movva N R. pepM is an essential gene in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5215–5217. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5215-5217.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyata M, Sano K-I, Okada R, Fukumura T. Mapping of replication initiation site in Mycoplasma capricolum genome by two-dimensional gel-electrophoretic analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4816–4823. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.20.4816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizuno M, Masuda S, Takemaru K-I, Hosono S, Sato T, Takeuchi M, Kobayashi Y. Systematic sequencing of the 283 kb 210°-232° region of the Bacillus subtilis genome containing the skin element and many sporulation genes. Microbiology. 1996;142:3103–3111. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-11-3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monnet V, Nardi M, Chopin A, Chopin M-C, Gripon J-C. Biochemical and genetic characterization of PepF, an oligopeptidase from Lactococcus lactis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32070–32076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Movva N R, Semon D, Meyer C, Kawashima E, Wingfield P, Miller J L, Miller C G. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the Salmonella typhimurium pepM gene. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;223:345–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00265075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura K, Nakamura A, Takamatsu H, Yoshikawa H, Yamane K. Cloning and characterization of a Bacillus subtilis gene homologous to E. coli secY. J Biochem. 1990;107:603–607. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nardi M, Chopin M-C, Chopin A, Cals M-M, Gripon J-C. Cloning and DNA sequence analysis of an X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase gene from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis NCDO 763. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:45–50. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.45-50.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogasawara N, Nakai S, Yoshikawa H. Systematic sequencing of the 180 kilobase region of the Bacillus subtilis chromosome containing the replication origin. DNA Res. 1994;1:1–14. doi: 10.1093/dnares/1.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramos A, Macias J R, Gil J A. Cloning, sequencing and expression of the gene encoding the elongation factor P in the amino-acid producer Brevibacterium lactofermentum (Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13869) Gene. 1997;198:217–222. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00317-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rawlings N D, Barrett A J. Evolutionary families of metallopeptidases. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:183–228. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roderick S L, Matthews B W. Structure of the cobalt-dependent methionine aminopeptidase from Escherichia coli: a new type of proteolytic enzyme. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3907–3912. doi: 10.1021/bi00066a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sabelnikov A G, Greenberg B, Lacks S A. An extended −10 promoter alone directs transcription of the DpnII operon of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Mol Biol. 1995;250:144–155. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simon D, Chopin A. Construction of a vector plasmid family for molecular cloning in Streptococcus lactis. Biochimie. 1988;70:559–566. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(88)90093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stucky K, Klein J R, Schuller A, Matern H, Henrich B, Plapp R. Cloning and DNA sequence analysis of pepQ, a prolidase gene from Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis DSM7290 and partial characterization of its product. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;247:494–500. doi: 10.1007/BF00293152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan P S T, Chapot-Chartier M-P, Pos K M, Rousseau M, Boquien C-Y, Gripon J-C, Konings W N. Localization of peptidases in lactococci. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:285–290. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.1.285-290.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Urbach G. Contribution of lactic acid bacteria to flavour compound formation in dairy products. Int Dairy J. 1995;5:877–903. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yan T-R, Ho S-C, Hou C L. Catalytic properties of X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris nTR. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1992;56:704–707. doi: 10.1271/bbb.56.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yasueda H, Nagase K, Hosoda A, Akiyama Y, Yamada K. High-level direct expression of semi-synthetic human interleukin-6 in Escherichia coli and production of N-terminus Met-free gene product. Bio/Technology. 1990;8:1036–1040. doi: 10.1038/nbt1190-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yasueda H, Kikuchi Y, Kojima H, Nagase K. In-vivo processing of the initiator methionine from recombinant human interleukin-6 synthesized in Escherichia coli overproducing aminopeptidase-P. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1991;36:211–215. doi: 10.1007/BF00164422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zevaco C, Monnet V, Gripon J-C. Intracellular X-prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis: purification and properties. J Appl Bacteriol. 1990;68:357–366. [Google Scholar]