Abstract

Current mathematical models used by food microbiologists do not address the issue of competitive growth in mixed cultures of bacteria. We developed a mathematical model which consists of a system of nonlinear differential equations describing the growth of competing bacterial cell cultures. In this model, bacterial cell growth is limited by the accumulation of protonated lactic acid and decreasing pH. In our experimental system, pure and mixed cultures of Lactococcus lactis and Listeria monocytogenes were grown in a vegetable broth medium. Predictions of the model indicate that pH is the primary factor that limits the growth of L. monocytogenes in competition with a strain of L. lactis which does not produce the bacteriocin nisin. The model also predicts the values of parameters that affect the growth and death of the competing populations. Further development of this model will incorporate the effects of additional inhibitors, such as bacteriocins, and may aid in the selection of lactic acid bacterium cultures for use in competitive inhibition of pathogens in minimally processed foods.

The presence of pathogenic microorganisms on minimally processed refrigerated (MPR) vegetable products and the ability of these microorganisms to grow during storage have been documented (6, 25, 30, 33, 41, 43). Current trends are to extend the shelf life of MPR vegetable products by reducing the microbial load through washing or sanitizing procedures, modified-atmosphere packaging, and other methods (1, 5, 6, 17, 37). Development of these technologies has raised some concerns about how the microbial ecology of the products may be affected, and questions concerning the potential for growth of pathogens (17, 21, 23, 25, 43) have arisen. Jay (26) has argued that the success of sanitation procedures used to eliminate pathogenic bacteria from foods may have encouraged the emergence of Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli O157:H7, and other organisms as food-borne pathogens by reducing the competitive microorganism populations.

The use of competitive microflora to enhance the safety of MPR products has been proposed by a number of authors (reviewed in references 20, 24, and 44). It has been suggested that lactic acid bacteria (LAB) could be used for this, in part because of their “generally regarded as safe” (GRAS) status and because they are commonly used in food fermentations. LAB species in refrigerated food products can produce a variety of metabolites, such as lactic and acetic acids (which lower the pH), hydrogen peroxide, bacteriocins, etc., which are inhibitory to competing bacteria in foods, including psychrotrophic pathogens (15, 28, 36, 49). The safety of traditional fermented products has not been questioned, and the objective of using biocontrol cultures is not to ferment foods but to control microbial ecology if spoilage does occur. An example of the use of LAB biocontrol cultures is the Wisconsin process for ensuring the safety of bacon (45, 46). Recent studies of this type have included the use of protective cultures in a variety of refrigerated meat (4, 14, 40, 53) and vegetable (10, 38, 50, 51) products. While these studies have shown that the use of LAB as competitive cultures may be effective in preventing the growth of pathogens in foods, a detailed investigation into the mechanisms by which this competitive inhibition occurs has not been carried out.

We chose a modeling approach to examine the dynamic nature of the interference type of competition or amensalism, in which one bacterial culture inhibits the growth of another (and itself as well) by producing inhibitory metabolites. To our knowledge, no models of this type have been described previously. This type of bacterial competition is associated with biocontrol applications in foods, as well as food fermentations or spoilage, where there is usually an excess of nutrients. While models for other types of competition between species have been described, including parasitism, predation, competition for nutrients, etc. (reviewed in references 16 and 18), the mathematics and ecology literature on amensalism is very limited. Frederickson (18) concluded that “amensalism, interference-type competition, and indirect parasitism should be studied both mathematically and experimentally, since the sum total of quantitative knowledge concerning these interactions is near zero.” A long-term goal of this research is to develop a theoretical foundation for the use of biocontrol cultures in foods by determining the factors important in the predominance of biocontrol bacteria over pathogenic microorganisms.

A number of models have been developed to predict the growth of bacteria in foods (for reviews see references 3, 35, 42, and 54). Several common types of growth models, including the logistic, Gompertz, and Richards curves, have been shown to be special cases of a more general model (35, 47, 48). These models may be classified as empirical models; they describe sigmoidal functions that approximate bacterial growth curves of cell concentration versus time. A modified Gompertz curve (9, 19, 54), which may be used to predict the logarithm of cell concentration over time, has been found to most closely approximate bacterial growth (54). It has been argued, however, that the usefulness of empirical models is limited and that a more fundamental understanding of the changes that take place during batch growth of bacteria will require the use of mechanistic models (2, 34, 52). Mechanistic models may be developed from theoretical or experimentally determined data describing the cause or mechanism behind the dynamic changes observed in an experimental system. Our model may be classified as partially mechanistic, based on our use of organic acid and pH as variables that affect the growth and death of the competing cultures. As our understanding of how these factors affect bacterial growth increases, we may approach our goal of a fully mechanistic model.

Our primary model system consists of an LAB, Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis NCK401, in competition with a pathogen, L. monocytogenes F5069B, in a vegetable broth extract. In this system, lactic acid is the main inhibitory compound that affects the growth of the competing bacteria. Both of these organisms carry out homolactic fermentation. The inhibitory properties of organic acids, such as lactic acid, have been attributed to the protonated forms of the acids, which are uncharged and may therefore cross biological membranes. The resulting inhibition of growth may be due to the acidification of the cytoplasm and/or accumulation of acid anions inside the cell (39). In general, LAB are much more resistant to low pH values than other bacteria are. McDonald et al. (31) found that the low limiting internal pH of selected LAB correlated with the ability of these organisms to survive in vegetable fermentations. Important criteria for choosing LAB for use as biocontrol cultures should, therefore, include such factors as protonated acid sensitivity, pH sensitivity, and acid production rate. By incorporating these factors as parameters into our model, we were able to determine estimated values for these parameters and to gain insight into their relative importance in the competitive growth process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

Strain LA221 (NCK403 transformed with pGK12 [see below]), a non-nisin-producing derivative (22), was obtained from the USDA Food Fermentation Lab culture collection (Raleigh, N.C.). L. monocytogenes B164 (F5069, serotype 4b, transformed with pGKE [see below]) was obtained from C. Donnely of the University of Vermont. Plasmids pGKC and pGKE were derivatives (6a) of pGK12 (27) and carried the genes encoding either chloramphenicol resistance (pGKC) or erythromycin resistance (pGKE). LA221 was transformed with pGKC by electroporation by using a modification of the method of Luchansky et al. (29), as described by Breidt and Fleming (7). L. monocytogenes B164 was similarly transformed with pGKE by Romick (38). Both plasmids were determined to have stably transformed the bacteria (6b, 38). L. lactis LA221 was grown on M17 (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) broth containing 1.5% agar (Difco) and 1% glucose (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) for plate medium, and L. monocytogenes F5069 was grown on tryptic soy agar (TSA) (Difco) supplemented with 1% glucose (Sigma). To select for antibiotic-resistant strains, chloramphenicol (M17-glucose agar) or erythromycin (TSA-glucose agar) was added at a concentration of 5 μg/ml. Cucumber juice (CJ) medium containing 60% cucumber juice in water supplemented with 2% NaCl was prepared as described by Daeschel et al. (12).

Measurement of bacterial growth kinetics.

Bacterial growth rates were determined by using a microtiter plate reader, as described by Breidt et al. (8). Cells were grown in 200-μl fermentation volumes in a temperature-controlled microtiter plate reader (model EL312; Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, Vt.) placed inside a heating-cooling incubator (Ambi-Hi-Low Chamber; Lab-Line Instruments Inc., Melrose Park, Ill.). Incubation of the microtiter plate reader in the environment chamber allowed the microtiter plates to be incubated at constant temperatures above or below room temperature, as indicated below. The 200-μl culture broth preparations were overlaid with mineral oil to prevent evaporation during extended incubation. The microtiter plate reader was controlled with KinetiCalc software, version 2.03 (Bio-Tek), which allowed optical density readings to be taken every 1.5 h for up to 99 h. The resulting ASCII text data file was processed by using Regress software (8). In the competitive growth experiments, bacterial cell counts were determined by using a spiral plater (Autoplate 3000; Spiral Biotech, Inc., Bethesda, Md.) and a colony counter (Protos Plus; Bioscience International, Rockville, Md.).

Biological assays.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analyses of organic acids and sugars were carried out by using the single-injection method of McFeeters (32). An Aminex HPX-87H column was used along with 3 mM heptafluorobutyric acid (Aldrich Chemical Co. Inc., Milwaukee, Wis.) as the mobile phase. Organic acids were detected with a conductivity detector (model CDM-2; Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, Calif.), and sugars were detected in-line following NaOH addition with a pulsed amperometric detector (model PAD-2; Dionex). Data were collected by using Chrom Perfect software (Justice Innovations, Inc., Mountain View, Calif.) run on a 486/33 computer (Gateway2000, North Sioux City, S.D.). Protonated acid concentrations were calculated by using the Henderson-Hasselbach equation, based on the acid concentration and the pH of the medium. The pH values were determined by using a micro combination electrode (Accumet model 13-620-279; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, Pa.).

Statistics and programming.

Predicted data and parameters for the nonlinear differential equation model (see Appendix A) were determined with simulation software written in C++ (Borland C++ for Windows, version 4.5; Borland International, Inc., Scotts Valley, Calif.) by using a 486/33 computer (Gateway2000). This simulation program runs under the Microsoft Windows 95 environment. It allows entry of model parameter values, carries out numerical integration, and then graphically displays the observed and predicted results. The algorithm used a fourth-order Runge-Kutta numerical integration method (see Appendix B). A constant step size of 0.05 on a time scale of 0 to 100 U was used; the rate parameters and time for the experiment were adjusted to this scale for calculations, but the values reported below were corrected to represent real time. The pH values were converted to free hydrogen ion concentrations for all calculations.

The initial parameter estimates were obtained by manual iterations of changing the parameters, calculating the predicted growth results, and viewing the predicted and experimental results with the simulation software. Further fitting of the five-equation model with the simulation program was based on minimizing the total sum of squared errors for the observed values minus the expected values (for all time points of observed and predicted data) for the variables in the model. To prevent the error term from being dominated by the high cell and hydrogen ion concentrations, the log of the cell concentration and pH values were used for this calculation. The error term was evaluated for a sequence of parameter values determined by using a random walk procedure, starting from the initial estimated parameter values. For each step in the random walk, the parameters were adjusted by a scaled increment, either increasing, decreasing, or not changing the current value, with equal probability. With the simulation program, user-selected parameter values and increments were used for the random walk. This allowed some parameters, such as those for specific growth rates or MICs, to be held constant, while other values were changed during the random walk. The least-squares function was then recalculated, and if the value decreased, the changes were accepted and the new values were used for the next step in the random walk. A goodness-of-fit value, similar to R2 in linear regression, was also determined. For each variable in the model, this value was determined by using the equation 1 − (SSE/SST), where SSE (sum of squared errors) is the sum of squared errors as described above and SST (total sum of squares) is the sum of the squared deviations of the predicted values from the mean of the observed values. The mean of the five R2 values for each set of variables in the model was determined for each set of initial starting conditions.

MIC determinations.

MICs for the inhibition of growth by lactic acid were determined by measuring growth rates with different concentrations of acid in CJ broth medium. To determine the MICs for protonated acid, the pH and ionic strength of the medium were kept constant at 5.6 and 0.342 (equivalent to the ionic strength of 2% NaCl), respectively, while the concentration of protonated lactic acid was varied. The NaCl concentration was varied to maintain the constant ionic strength as the lactic acid anion concentration was increased. The contribution of malic acid ions (the major organic acid naturally present in CJ) to the ionic strength was included in the calculations to determine total ionic strength. The lactic acid used in these determinations was prepared from a concentrated stock solution (88% lactic acid; Sterling Chemicals, Inc., Texas City, Tex.). The 88% lactic acid solution was diluted 1:4 in deionized water. The diluted solution was then refluxed for approximately 16 h to hydrolyze lactic acid oligomers. A sample of the reflux solution was analyzed by HPLC by using an anion-exchange column (type HPX87-H; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) at 75°C along with a refractive index detector (model 410; Waters Associates, Inc., Milford, Mass.). The eluent was 0.01 N sulfuric acid at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. By comparing the chromatograms obtained before and after refluxing, we determined that the solution was monomeric by the absence on the chromatogram of secondary peaks which were initially present.

To determine the minimum pH that allowed growth, the ionic strength was kept constant at 0.342, as described above, and 50 mM malic acid was added to increase the buffering capacity. Total acid concentrations were determined by HPLC as described above. The growth rates were determined by using the microtiter plate method described above and triplicate (or more) independent fermentations. For all MIC determinations, the regression equation and coefficient were determined from the entire data set, but only the mean values for the data are shown below. The intercept of the regression line (extrapolated to give a specific growth rate of zero) was used to determine the predicted MICs.

Competitive growth experiments.

Cultures were prepared by growing cells overnight (for 16 h) at 30°C in CJ medium containing the appropriate antibiotic (chloramphenicol for LA221; erythromycin for B164) at a concentration of 5 μg/ml. The cells were harvested from these overnight cultures and resuspended in an equal volume of fresh CJ medium without antibiotics. The cells were diluted to the starting concentration by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (the preparations were diluted so that they were in the linear range of the spectrophotometer) and using a standard curve for optical density versus number of CFU per milliliter (data not shown). Twenty-milliliter portions of the cell suspensions containing mixed or pure cultures in CJ medium were injected aseptically through the septa of sterile Vacutainer tubes (16 by 165 mm; Becton-Dickinson and Co., Franklin Lakes, N.J.) that contained no additive. The tubes were incubated at 10°C in a heating-cooling water bath (MGW Lauda model RC2; Brinkmann Instrument Co., Westbury, N.Y.). Samples were obtained from the tubes (after mixing to ensure that the cells were evenly suspended) at different times by aseptically removing 1-ml portions with a syringe. Each 1-ml sample was used to determine the number of CFU per milliliter by diluting it as needed and plating it onto antibiotic-containing media with the spiral plater. The remaining sample was frozen at −20°C and saved for use in pH and HPLC analyses. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 48 h, and the number of CFU per milliliter in each sample was determined with the automated plate counter (as described above).

RESULTS

Dynamic growth model.

To characterize the potential of L. lactis as a biocontrol culture, competitive growth studies were carried out. The ability of L. lactis LA221 to inhibit the growth of L. monocytogenes F5069B in a mixed culture was investigated at 10°C. This temperature was chosen as an abuse temperature, like the temperatures that may occur when there is improper refrigeration of minimally processed foods. To understand the factors that allow one culture to predominate over another, we developed a model that incorporated the variables that directly affected the growth of each organism in the mixed culture (see Appendix A). The rate equations in the model were similar in form to the logistic equation for bacterial growth (16). Because L. lactis LA221 (an organism that does not produce nisin) and L. monocytogenes both carry out homolactic fermentation of glucose, the primary regulators of growth were assumed to be (protonated) lactic acid and the low pH of the medium during growth of these bacteria. Malic acid concentration was included as a variable in the model because our CJ medium contained malate (concentration, approximately 8 mM), which is naturally found in cucumbers. L. lactis ferments malate via a malolactic enzyme (11), which raises the pH of the medium and affects the growth of the cells.

The cell growth functions in the model allowed for separate parameters controlling the inhibition of growth (for example kp3 and kp5) and metabolism (kp4 and kp6). This is because the bacteria can continue to metabolize and produce lactic acid during the stationary phase when (we assume) growth has ceased, as measured by the number of CFU per milliliter. At some point, however, the metabolism of the microorganisms can no longer be maintained as the protonated acid concentration increases and the number of CFU declines. The lag phase was modeled in the computer simulation (data not shown) as a Heaviside function, which forced the specific growth rate to zero for the duration of this phase. For this model, protonated lactic acid and pH were assumed to be the only effectors of growth. Both L. monocytogenes and L. lactis produced lactic acid by homolactic fermentation. The L. lactis strain did not produce nisin. Further development of the model will include the effects of the bacteriocin nisin and possibly additional inhibitors of growth, such as hydrogen peroxide, which may be produced by LAB.

Mixed-culture growth experiments.

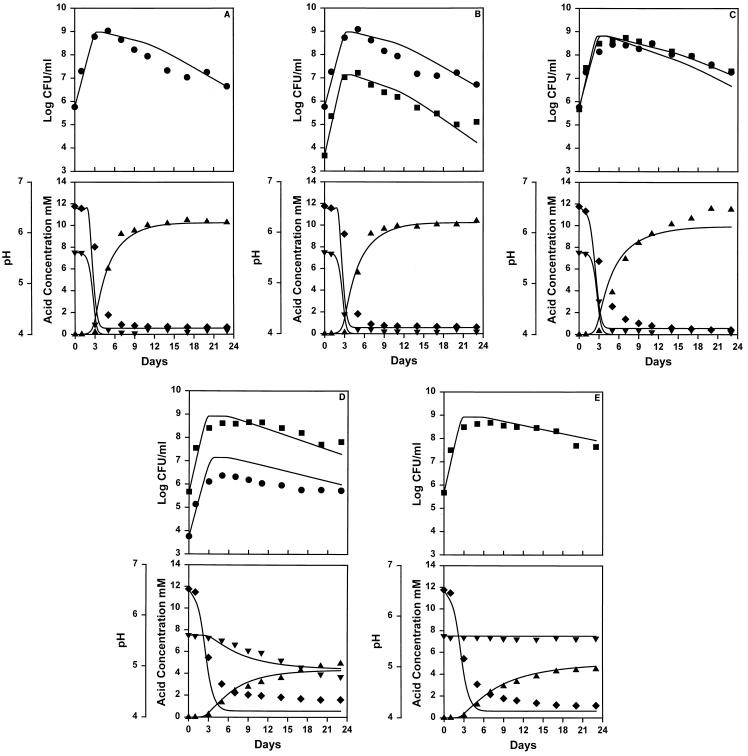

Figure 1 shows the observed and predicted results for growth of L. lactis and L. monocytogenes, both separately and in combination. The results predicted from the model in all cases were determined by using the parameter values shown in Table 1. The fit of the observed and predicted data was determined by using a measurement similar to R2, as described above. Figures 1A and E show the growth of L. lactis and L. monocytogenes in pure culture, respectively. In the mixed-culture experiments we used different ratios of initial cell concentrations for the mixed cultures; the ratios of L. lactis in competition with L. monocytogenes were 106:104 (Fig. 1B), 106:106 (Fig. 1C), and 104:106 (Fig. 1D). The mean pseudo-R2 values for growth both separately and in mixed culture were 0.940 (Fig. 1A), 0.922 (Fig. 1B), 0.896 (Fig. 1C), 0.832 (Fig. 1D), and 0.929 (Fig. 1E). The malic acid data was not used for the R2 calculation for the data shown in Fig. 1E because the predicted values did not change. Figure 1D shows that the L. lactis culture was inhibited by L. monocytogenes to a greater extent than predicted. This could have been due to some inhibitory effect of the L. monocytogenes culture not included in the model.

FIG. 1.

Observed and predicted results for the model. The observed data are indicated by symbols, and the predicted data are indicated by lines. The observed concentrations of L. lactis (•) and L. monocytogenes (■) (in log CFU per milliliter) are shown in the top panels, while the pH values (⧫), protonated lactic acid concentrations (in millimoles per liter) (▴), and malic acid concentrations (in millimoles per liter) (▾) are shown in the bottom panels. The same x axis is used for each pair of top and bottom panels.

TABLE 1.

Parameters used in the competitive growth model

| Parameter | Symbol(s) | Units | Estimated values

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. lactis | L. monocytogenes | Common | |||

| Specific growth rate | α, β | Hour−1 | 0.1049 | 0.1271 | |

| Protonated acid production rate | γ, δ | Millimoles CFU−1 hour−1 | 1.7 × 10−10 | 2.95 × 10−10 | |

| MIC (growth) of protonated acid | kp3, kp7 | Millimolar | 5.2 | 4.058b | |

| MIC (metabolism) of protonated acid | kp4, kp8 | Millimolar | 8.907 | 8.908b | |

| Maximum protonated acid concn | kp1, kp2 | Millimolar | 11.5 | 11.65b | |

| MIC (growth) of pH | kp5, kp9 | pH units | 4.405 | 4.892 | |

| MIC (metabolism) of pH | kp6, kp10 | pH units | 4.147 | 4.151 | |

| Minimum pHa | kp11 | pH units | 4.12 | 4.132 | |

| Malate utilization rate | θ | Millimoles CFU−1 hour−1 | 1.69 × 10−10 | 0 | |

| Buffering due to malate utilization | κ | Millimole−1 (malate) | −5.33 | ||

| Proton concentration change rate | ρ | Moles CFU−1 hour−1 | −5.472 | ||

For mixed cultures, this parameter takes the lowest pH value of the two listed parameter values.

These values were estimates only; growth was apparently controlled by pH, as described in the text.

Determination of parameter values.

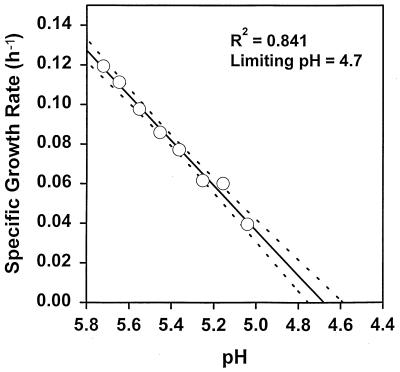

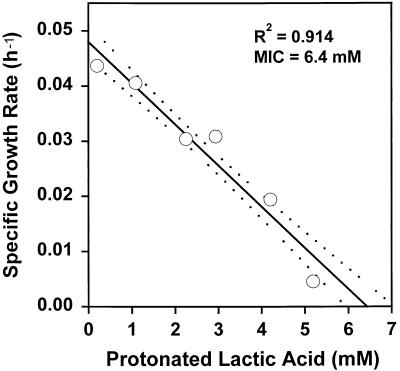

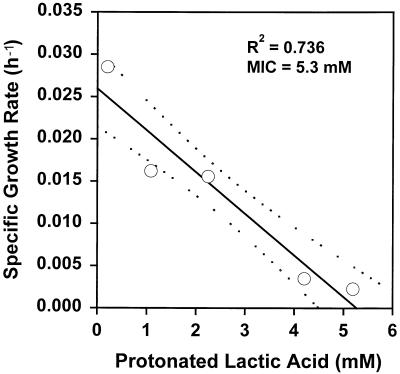

Table 1 shows the parameter estimates obtained with the model. To determine if the parameter values used in the model accurately reflected the parameter values for the bacterial cells, independent measurements were made for selected model parameters. Figure 2 shows the lowest pH value, pH 4.68, that allowed growth of L. monocytogenes in buffered CJ medium. The ionic strength of CJ medium was kept constant at 0.342, as described above. Figure 3 shows that the MIC of protonated lactic acid was 6.43 mM for L. monocytogenes in CJ medium when the ionic strength was 0.342 and the pH was kept constant at 5.6. Figure 4 shows similar data for the protonated acid MIC for L. lactis, which was found to be 5.3 mM. In addition, the specific growth rates for L. lactis (0.0932 h−1) and L. monocytogenes (0.1011 h−1) were measured independently in pure culture, and the resulting data, along with a summary of observed and estimated values from the model, are shown in Table 2. The parameter values for the inhibition of growth of L. monocytogenes by protonated acid were not accurately predicted by the model because in all cases, pH was found to be the limiting factor for growth for both mixed-culture growth and growth of L. monocytogenes in pure culture (as shown in Fig. 1B through E). Because regulators of pH and protonated acid were modeled as independent regulators of growth, only the most limiting of these factors can be predicted. While the pure-culture system can be modeled by using protonated acid as the sole growth-limiting factor (by changing the parameter values), the parameters used in this case do not allow the model to accurately predict the outcome of the competitive growth experiments (data not shown). For L. lactis, both protonated acid and pH were found to be important in the regulation of growth (Fig. 1A through D), giving the estimated parameter values shown in Table 1.

FIG. 2.

Limiting lower pH allowing the growth of L. monocytogenes. The mean values from five independent determinations of growth rate at each pH value are shown (○). The regression line for the entire data set (solid line) and the 95% confidence limits for the regression line (dashed lines) are also shown.

FIG. 3.

Limiting protonated acid concentration for the growth of L. monocytogenes. The mean values from five independent determinations of growth rate for each concentration of protonated acid are shown (○). The regression line for the entire data set (solid line) and the 95% confidence limits for the regression line (dashed lines) are also shown.

FIG. 4.

Limiting protonated acid concentration for the growth of L. lactis. The mean values from five independent determinations of growth rate for each concentration of protonated acid are shown (○). The regression line for the entire data set (solid line) and the 95% confidence limits (dashed lines) for the regression line are also shown.

TABLE 2.

Observed and predicted parameter values

| Parameter | Observed value | Predicted value |

|---|---|---|

| Specific growth rate (L. lactis) | 0.0923 h−1 | 0.1049 h−1 |

| Specific growth rate (L. monocytogenes) | 0.1011 h−1 | 0.1271 h−1 |

| MIC (growth) of protonated acid (L. lactis) | 5.3 mM | 5.2 mM |

| MIC (growth) of pH (L. monocytogenes) | pH 4.68 | pH 4.892 |

| MIC (growth) of protonated acid (L. monocytogenes) | 6.4 mM | —a |

—, This parameter was not predicted, as the growth was apparently controlled by pH, as described in the text.

DISCUSSION

Traditional bacterial growth models in food microbiology had the advantage of simplicity, and explicit solutions of the equations were possible. However, to understand the dynamic changes in the competitive growth of bacteria, more complex models may be needed. We used a series of nonlinear differential equations, which cannot be solved unless numerical methods are used. The Runge-Kutta algorithm which we used for numerical integration is widely used and relatively simple to program (13a). When a numerical approach is used, fewer limiting assumptions need to be made, and a mechanistic model can be used. The primary difficulty lies in picking the parameter values that allow the numerical solution to fit the observed data. As the complexity of the model grows and a number of data sets which use different initial starting conditions are generated, this problem becomes more difficult. To identify parameters, we developed computer software to carry out the numerical integration and graphically display the observed and predicted results, which allowed repeated trials of different parameter sets. A random search of the parameter space was then employed to find the best fit of the parameter values to the data. This random walk method was chosen for reasons of computational simplicity and because a complete search of all possible parameter combinations for even a very limited set of values was not possible for the 21 parameters of the model. Use of conventional minimization programs was confounded by the difficulty of programming a minimization algorithm to call a complex C++ function consisting of numerical integration of the model, followed by calculation of the sum of squared errors for the observed and predicted data. Further refinement of the parameter estimation algorithm will be the subject of future research. The model was validated by independent measurements of selected parameter values and by comparison of observed and predicted results. Because the parameter values for the model represent physical properties of the L. lactis and L. monocytogenes cells, they can aid in understanding how the growth of the competing cultures was controlled.

The parameter values obtained for the L. lactis and L. monocytogenes cultures were, in general, similar to each other, except that the acid production rate for L. lactis was faster than that for L. monocytogenes and the L. monocytogenes culture was more sensitive to low pH than the L. lactis culture was (Table 1). It was observed that the growth and death of the L. monocytogenes culture could be accurately predicted by the model only if pH was assumed to be the limiting variable. In every case (Fig. 1), growth of the L. monocytogenes culture ceased before the protonated acid concentration reached the independently determine MIC. This suggests that pH was the primary factor limiting the growth of L. monocytogenes for all of the initial starting conditions used in the model. An effective biocontrol culture for L. monocytogenes may, therefore, be one that produces a small amount of acid quickly to lower the pH, and large amounts of organic acid may not be needed.

It is interesting to note that as shown in Fig. 1D, the L. lactis culture did not grow as much as expected based on the prediction of the model. While this situation is not expected to occur in a biocontrol application (with the biocontrol culture having an initial cell number approximately 100 times smaller than the initial cell number of the target pathogen), this may indicate that the parameter values for the L. lactis culture are not optimized. An alternative explanation is that the L. monocytogenes culture produced some inhibitory metabolite not included in the model. Further research will include incorporating the effects of additional inhibitory metabolites of LAB, such as bacteriocins and hydrogen peroxide.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This investigation was supported in part by a research grant from Pickle Packers International, Inc., St. Charles, Ill, and by NRICGP grant 97-35201-4506.

Appendix

The model consists of a system of five differential equations with variables for the two cell types (N1 and N2), the protonated acid concentration (C), the concentration of hydrogen ions (P), and the malate concentration (M). Malate was included because L. lactis LA221 ferments malate by means of the malolactic enzyme, which raises the pH. The parameters are defined in Table 1.

|

A1 |

|

A2 |

|

A3 |

|

A4 |

|

A5 |

with

|

|

The growth functions (g1 and g2) modeled the inhibitory efects of protonated lactic acid or pH independently. This assumption was based on the work of Passos et al. (34), who modeled the growth of LAB in cucumber fermentations and found that the efects of pH, protonated lactic and acetic acids, and NaCl concentration could be modeled independently. The growth rate was modified by the minimum (min) value for a growth-limiting function. The functions Hi(C) and Hi(P) are discontinuous forcing functions (Heaviside functions) of the protonated acid and free hydrogen ion concentrations, respectively:

|

|

|

|

For H1 and H2, when C = kp3, C = kp4, P = kp5, or P = kp6, the value of the parameter was returned (similarly for H3 and H4). For any other value of C, the function is calculated as shown.

Appendix

For numerical integration, a Runge-Kutta single-step fourth-order method was used. The simulation program was based on the general algorithm (reviewed in reference 13):

|

|

|

|

|

The simulation program is available electronically. For information see http://www4.ncsu.edu/unity/users/f/fbreid/web/simwin.htm or contact the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams M R, Hartley A D, Cox L J. Factors affecting the efficacy of washing procedures used in the production of prepared salads. Food Microbiol. 1989;6:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baranyi J, Roberts T A. A dynamic approach to predicting bacterial growth in food. Int J Food Microbiol. 1994;23:277–294. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baranyi J, Roberts T A, Baranyi J, Roberts T A. Mathematics of predictive food microbiology. A dynamic approach to predicting bacterial growth in food. Int J Food Microbiol. 1995;26:199–218. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)00121-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry E D, Hutkins R W, Mandigo R W. The use of bacteriocin-producing Pediococcus acidilactici to control post-processing Listeria monocytogenes contamination of frankfurters. J Food Prot. 1991;54:681–686. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-54.9.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brackett R E. Influence of modified atmosphere packaging on the microflora and quality of fresh bell peppers. J Food Prot. 1990;53:255–257. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-53.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brackett R E. Shelf stability and safety of fresh produce as influenced by sanitation and disinfection. J Food Prot. 1992;55:808–814. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-55.10.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Breidt, F. Unpublished data.

- 6b.Breidt, F., and H. P. Fleming. Unpublished data.

- 7.Breidt F, Fleming H P. Competitive growth of genetically marked malolactic-deficient Lactobacillus plantarum in cucumber fermentations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3845–3849. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.12.3845-3849.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breidt F, Romick T L, Fleming H P. A rapid method for the determination of bacterial growth kinetics. J Rapid Methods Automation Microbiol. 1994;3:59–68. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchanan R L, Phillips J G. Response surface model for prediction of the effects of temperature, pH, sodium chloride content, sodium nitrate concentration, and atmosphere on the growth of Listeria monocytogenes. J Food Protect. 1990;53:370–376. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-53.5.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlin F, Nguyen-the C, Morris C E. Influence of background microflora on Listeria monocytogenes on minimally processed fresh broad-leaved endive (Cichorium endivia var. latifolia) J Food Prot. 1996;59:698–703. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-59.7.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caspritz G, Radler F. Malolactic enzyme of Lactobacillus plantarum: purification, properties, and distribution among bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1982;258:4907–4910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daeschel M A, McFeeters R F, Fleming H P, Klaenhammer T R, Sanozky R B. Mutation and selection of Lactobacillus plantarum strains that do not produce carbon dioxide from malate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:419–420. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.2.419-420.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danby J M A. Computer modeling. Richmond, Va: Willmann-Bell, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Danby, J. M. A. (North Carolina State University, Raleigh). Personal communication.

- 14.Degnan A J, Yousef A E, Luchansky J B. Use of Pediococcus acidilactici to control Listeria monocytogenes in temperature-abused vacuum-packaged wieners. J Food Prot. 1992;55:98–103. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-55.2.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeVuyst L, Vandamme E J. Antimicrobial potential of lactic acid bacteria. In: De Vuyst L, Vandamme E J, editors. Bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria. London, England: Blackie Academic and Professional; 1994. pp. 91–142. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edelstein-Keshet L. Mathematical models in biology. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill, Inc.; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farber J M. Microbiological aspects of modified-atmosphere packaging technology—a review. J Food Prot. 1991;54:58–70. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-54.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fredrickson A G. Behavior of mixed cultures of microorganisms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1977;31:63–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.31.100177.000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson A M, Bratchell N, Roberts T A. Predicting microbial growth: growth responses of Salmonellae in a laboratory medium as affected by pH, sodium chloride, and storage temperature. Int J Food Microbiol. 1988;6:155–178. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(88)90051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gombas D E. Biological competition as a preserving mechanism. J Food Saf. 1989;10:107–117. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hao Y-Y, Brackett R E. Influence of modified atmosphere on growth of vegetable spoilage bacteria in media. J Food Prot. 1993;56:223–228. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-56.3.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris L J, Fleming H P, Klaenhammer T R. Characterization of two nisin-producing Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis strains isolated from a commercial sauerkraut fermentation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1477–1483. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.5.1477-1483.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hintlian C B, Hotchkiss J H. Comparative growth of spoilage and pathogenic organisms on modified atmosphere-packaged cooked beef. J Food Prot. 1987;50:218–223. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-50.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holzapfel W H, Geisen R, Schillinger U. Biological preservation of foods with reference to protective cultures, bacteriocins, and food-grade enzymes. Int J Food Microbiol. 1995;24:343–362. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hotchkiss J H, Banco M J. Influence of new packaging technologies on the growth of microorganisms in produce. J Food Prot. 1992;55:815–820. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-55.10.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jay J M. Foods with low numbers of microorganisms may not be the safest foods, or why did human listeriosis and hemorrhagic colitis become foodborne diseases? Dairy Food Environ Sanit. 1995;15:674–677. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kok J, van der Vossen J M B M, Venema G. Construction of plasmid cloning vectors for lactic streptococci which also replicate in Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;48:726–731. doi: 10.1128/aem.48.4.726-731.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindgren S E, Dobrogosz W J. Antagonistic activities of lactic acid bacteria in food and feed fermentations. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1990;87:146–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luchansky J B, Muriana P M, Klaenhammer T R. Application of electroporation for transfer of plasmid DNA to Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, Listeria, Pediococcus, Bacillus, Staphylococcus, Enterococcus, and Propionibacterium. Mol Microbiol. 1988;2:637–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1988.tb00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madden J M. Microbial pathogens in fresh produce—the regulatory perspective. J Food Prot. 1992;55:821–823. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-55.10.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonald L C, Fleming H P, Hassan H M. Acid tolerance of Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2120–2124. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.7.2120-2124.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McFeeters R F. Single-injection HPLC analysis of acids, sugars, and alcohols in cucumber fermentations. J Agric Food Chem. 1993;41:1439–1443. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen-the C, Carlin F. The microbiology of minimally processed fresh fruits and vegetables. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1994;34:371–401. doi: 10.1080/10408399409527668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Passos F V, Fleming H P, Ollis D F, Hassan H M, Felder R M. Modeling the specific growth rate of Lactobacillus plantarum in cucumber extract. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;40:143–150. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pruitt K M, Kamau D N. Mathematical models of bacterial growth, inhibition, and death under combined stress conditions. J Ind Microbiol. 1993;12:221–231. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ray B. Cells of lactic acid bacteria as food biopreservatives. In: Ray B, Daeschel M, editors. Food biopreservatives of microbial origin. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1992. pp. 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reina L D, Fleming H P, Humphries E G. Microbiological control of cucumber hydrocooling water with chlorine dioxide. J Food Prot. 1995;58:541–546. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-58.5.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Romick T L. Biocontrol of Listeria monocytogenes, a psychrotrophic pathogen model, in low-salt, non-acidified, refrigerated vegetable products. Ph.D. thesis. North Carolina State University, Raleigh; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Russel J B. Another explanation of the toxicity of fermentation acids at low pH: anion accumulation versus uncoupling. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;73:363–370. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schillinger U, Kaya M, Lucke F-K. Behavior of Listeria monocytogenes in meat and its control by a bacteriocin-producing strain of Lactobacillus sake. J Appl Bacteriol. 1991;70:473–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1991.tb02743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schofield G M. Emerging foodborne pathogens and their significance in chilled foods. J Appl Bacteriol. 1992;72:267–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1992.tb01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skinner G E, Larkin J W, Rodehamel E J. Mathematical modeling of microbial growth: a review. J Food Saf. 1994;14:175–217. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sofos J N. Current microbiological considerations in food preservation. Int J Food Microbiol. 1993;19:87–108. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(93)90176-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stiles M E. Biopreservation by lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:331–345. doi: 10.1007/BF00395940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanaka N, Meske L, Doyle M P, Traisman E, Thayer D W, Johnston R W. Plant trials of bacon made with lactic acid bacteria, sucrose and lowered sodium nitrite. J Food Prot. 1985;48:679–686. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-48.8.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanaka N, Traisman E, Lee M H, Cassens R G, Foster E M. Inhibition of botulinum toxin formation in bacon by acid development. J Food Prot. 1980;43:450–457. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-43.6.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turner M E, Bradley E L, Kirk K A, Pruitt K M. A theory of growth. Math Biosci. 1976;29:367–373. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turner M E, Pruitt K M. A common basis for survival, growth, and autocatalysis. Math Biosci. 1978;39:113–123. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vandenberg P A. Lactic acid bacteria, their metabolic products and interference with microbial growth. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;12:221–238. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vescovo M, Orsi C, Scolari G, Torriani S. Inhibitory effect of selected lactic acid bacteria on microflora associated with ready-to-use vegetables. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1995;21:121–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1995.tb01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vescovo M, Torriani S, Orsi C, Macchiarlol F, Scolari G. Application of antimicrobial-producing lactic acid bacteria to control pathogens in ready-to-use vegetables. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996;81:113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb04487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whiting R C, Cygnarowicz-Provost M. A quantitative model for bacterial growth and decline. Food Microbiol. 1992;9:269–277. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winkowski K, Crandall A D, Montville T J. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes by Lactobacillus bavaricus MN in beef systems at refrigeration temperatures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2552–2557. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2552-2557.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zwietering M H, Jongenburger I, Rombouts F M, van’t Riet K. Modeling of the bacterial growth curve. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1875–1881. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1875-1881.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]