Abstract

Cyperus rotundus L. exhibits promising potential for the development of functional foods due to its documented pharmacological and biological activities. This study investigated the antioxidant and anti-diabetic properties of C. rotundus kombucha. The results demonstrated potent antioxidant activity with an IC50 value of 76.7 ± 9.6 µL/mL for the DPPH assay and 314.2 ± 16.9 µL/mL for the ABTS assay. Additionally, the kombucha demonstrated alpha-glucosidase inhibitory with an IC50 value of 142.7 ± 5.2 µL/mL. This in vitro antioxidant potential was further validated in vivo using Drosophila. Drosophila fed a high-sugar diet and supplemented with pure kombucha revealed significant increases in DPPH and ABTS free radical scavenging activity. Drosophila on a high-sugar diet supplemented with varying kombucha concentrations manifested enhanced resistance to oxidative stresses induced by H2O2 and paraquat. Concurrently, there was a notable decline in lipid peroxidation levels. Additionally, significant upregulations in CAT, SOD1, and SOD2 activities were observed when the high-sugar diet was supplemented with kombucha. Furthermore, in vivo assessments using Drosophila demonstrated significant reductions in alpha-glucosidase activity when fed with kombucha (reduced by 34.04%, 13.79%, and 11.60% when treated with 100%, 40%, and 10% kombucha, respectively). A comprehensive GC-MS and HPLC analysis of C. rotundus kombucha detected the presence of antioxidative and anti-glucosidase compounds. In conclusion, C. rotundus kombucha exhibits considerable antioxidant and anti-diabetic properties, demonstrating its potential as a beneficial beverage for health promotion.

Keywords: functional food, health benefit, herbal medicine, health promotion

1. Introduction

Cyperus rotundus L. from the Cyperaceae family, also known as purple nutsedge, is documented as a longevity remedy in ancient Thai manuscripts. Historically, this herb has been employed in traditional medicinal practices across China, India, Africa, Japan, and Arab nations to treat various ailments [1]. Numerous studies have provided evidence that the tubers and rhizomes of this particular plant have a wide range of therapeutic properties. These include antioxidant [2,3,4], anti-diabetic [5,6], and anti-obesity effects [7]. They also have antiallergic [8], antimicrobial [9], and antidiarrheal capabilities [10]. Moreover, they offer cardioprotective [11], gastroprotective [12], and hepatoprotective benefits [13]. The plant also exhibits immunomodulatory [14], neuroprotective [15,16], and anticarcinogenic properties [17]. Additionally, it has been found to have antiarthritic [18,19,20], anti-inflammatory, anti-uropathogenic [21], anticonvulsant [22], and antidepressant effects [23]. Recently reports have revealed that the hydroethanolic extract of C. rotundus enhances sexual behavior and fitness in Drosophila [24]. The supplementation of Drosophila with this extract resulted in an increase in lifespan and a decrease in oxidative stress-induced mortality [25]. In a Drosophila obesity model, supplementation with C. rotundus extract exhibited to extend lifespan in the presence of high-fat diet-induced mortality [26]. Given its demonstrated biological and pharmacological properties, this plant’s rhizomes and tubers have the potential to be used in the development of functional foods and beverages. These products may offer viable alternatives for disease prevention and therapeutic interventions.

The inhibition of alpha-glucosidase is critical for the effective management of type-2 diabetes, which is distinguished by hyperglycemia, resistance to insulin, and insufficient insulin secretion [27]. By decelerating the conversion of carbohydrates into simple sugars, alpha-glucosidase suppressants can reduce post-meal glucose increases, facilitating in maintaining of steady blood sugar levels and functioning as an effective diabetes treatment. In addition to their utility in the treatment of diabetes, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors have attracted attention for their therapeutic potential in treating a variety of diseases [28]. Some findings indicate that a delayed carbohydrate digestion process might increase the feeling of fullness, potentially reducing overall calorie consumption and nurturing weight reduction [29]. Currently, the majority of anti-glucosidase action research is conducted in in vitro settings, which may not replicate the complexity of living conditions. Animal research should be intensive in order to discover and validate promising drug candidates for the management of diabetes.

In scientific literature, kombucha is acknowledged for its putative health benefits, which range from improved digestive and immune function to cholesterol level modulation and detoxification processes [30,31]. Although empirical research addressing these assertions is still in its early stages, the beverage’s rising popularity is influenced by the global trend toward natural and probiotics-enriched foods and beverages. Numerous in vitro studies have investigated the bioactivities of kombucha and its constituents, but the number of published in vivo studies is significantly less. To obtain a comprehensive understanding, it is essential to expand in vivo studies, conduct detailed bio-accessibility and bioavailability assessments, and precisely identify bioactive compounds. These initiatives will facilitate a thorough investigation of distinctive molecular functions.

Drosophila melanogaster or fruit fly is recognized as a model organism for investigating metabolic disorders. This organism has contributed to the development of diabetes models that replicate the complexities of type-2 diabetes in humans. A technique for inducing T2D symptoms in Drosophila via high-sugar diets has been developed [32]. Comparable to human physiology, Drosophila contains insulin-producing cells, insulin-like molecules, and an insulin-receptive mechanism [33]. In both the larval and adult stages of Drosophila, characteristics similar to insulin resistance, such as metabolic disorders and disrupted insulin signaling, can be replicated [34]. The established effects of high-sugar diets on Drosophila include high blood sugar levels, insulin resistance, increased fat accumulation, and decreased lifespan [35]. In addition, researchers have investigated the effect of botanical extracts on preventing metabolic disruptions in Drosophila caused by a high sucrose intake. Additionally, fruit flies contain the glucosidase enzyme, which is essential for sugar adaptation [36]. Therefore, Drosophila is a suitable model for evaluating the alpha-glucosidase-inhibitory properties of specific compounds.

In this study, we investigated the antioxidant and anti-diabetic properties of C. rotundus kombucha both in vitro and in vivo. Additionally, we analyzed its phytochemical composition. Our findings serve to bridge the gap between in vitro observations and in vivo conditions, potentially emphasizing the prospective role of C. rotundus kombucha as a functional beverage for disease prevention or intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

a,a-Diphenyl-b-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 2,20-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline- 6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS), sodium phosphate monobasic, α-glucosidase, hydrogen peroxide, 1,1′-dimethyl-4,4′-bi-pyridinium dichloride (paraquat dichloride hydrate), CAT assay kit, SOD assay kit, and sodium phosphate dibasic were purchased from the Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). The SCOBY agent was purchased from Master Lab Company (Ubonratchathani, Thailand).

2.2. Plant Materials and Preparation of Kombucha

C. rotundus rhizomes and tubers were collected from crop fields in the Thai province of Singburi in April 2022. The Nattapong 01 voucher specimen was preserved at the Mahasarakham University Herbarium, with a collection date of 21 April 2022. The plant samples were washed and then dried for two days in a 50 °C hot air oven. After drying, the materials were pulverized to a fine powder. C. rotundus kombucha was prepared by boiling with 1% (w/v) C. rotundus powder for 10 min. After boiling, it was filtered through cheesecloth at a temperature of 95 °C. Subsequently, 5% sugar (w/v) was added, and the mixture was boiled for an additional 5 min. The boiled solution was then transferred to a sterile container. Once boiled solution was cooled, a 10% SCOBY (w/v) was added. The container was covered with cheesecloth and left to ferment at room temperature for 10 days.

2.3. GC-MS Analysis of C. rotundus Kombucha

Phytochemical analysis of the C. rotundus kombucha was performed utilizing a GC-MS apparatus (7890B GC/5977B MSD, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a 30 m HP-5MS capillary column, featuring a 250 mm diameter and a phase thickness of 0.25 mm. The kombucha sample was proportionally diluted with ethanol and introduced in a splitless mode. The oven started at 50 °C, maintained for 0.5 min, subsequently elevated to 250 °C at a rate of 10 °C per minute, and was sustained at this temperature for an additional 5 min. Helium (99.999%) served as the carrier gas with a regulated flow of 1.2 mL/min. The MS source temperature remained fixed at 230 °C, with a scan mode analysis spanning a mass range from 40 to 500. The compounds were identified using the NIST Mass Spectral Database.

2.4. HPLC Analysis of C. rotundus Kombucha

The evaluation of phenolic acids and flavonoids was conducted using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) from Agilent Technology, Santa Clara, CA, USA. The apparatus consisted of a protective guard column and an InertSustain® C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm i.d., 5 m; sourced from GL Sciences Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and 0.1% acetic acid in water, using following gradient: 0–5 min: 15% acetonitrile; 5–10 min: 25% acetonitrile; 10–20 min: 15% acetonitrile. The flow rate was 0.5 mL/min. At wavelengths of 280 and 320 nm, a diode array detector was employed to detect phenolic acids and flavonoids. The use of external standards facilitated the identification and comparison of individual phenolic acids and flavonoids within the samples.

2.5. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity

2.5.1. Scavenging DPPH Free Radical Activity Assay

The inhibitory effect on DPPH free radical activity of kombucha was evaluated by mixing 180 μL of kombucha solution with 20 μL of a 1 mM DPPH solution (solubilized in methanol). Reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at room temperature under no light. The absorbance at a wavelength of 517 nm was measured using an ELISA reader (Biochrome, UK) to determine the inhibitory effect. Each sample was examined three replicates. The inhibitory activity was calculated using the following formula:

| Inhibition (%) = ((Abs of control − Abs of sample)/(Abs of control)) × 100 |

where “Abs of the control” refers to the DPPH solution’s absorbance value without the sample.

The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was established from the regression equation derived from plotting the percentage of inhibition against kombucha concentrations (0–800 µL/mL, diluted with sterile water).

2.5.2. Scavenging ABTS Free Radical Activity Assay

The inhibitory effect of kombucha on ABTS free radical activity was assessed by mixing 20 µL of the kombucha solution with 180 µL of the ABTS• solution. The latter was prepared by combining 10 mL of 7 mM ABTS (in ultrapure water) with 10 mL of 2.45 mM ammonium persulphate and then incubating it overnight (12–16 h) at room temperature in the dark. The concentration of the ABTS radical (ABTS•) stock solution was verified at 734 nm. An ABTS• solution was prepared to achieve an absorption of approximately 0.700 at 734 nm. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. The absorbance at a wavelength of 734 nm was measured using an ELISA reader (Biochrome, UK) to determine the inhibitory effect. Each sample was examined three replicates. The inhibitory activity was calculated using the following formula:

| Inhibition (%) = ((Abs of control − Abs of sample)/(Abs of control)) × 100 |

where “Abs of the control” refers to the ABTS• solution’s absorbance value without the sample.

The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was established from the regression equation derived from plotting the percentage of inhibition against kombucha concentrations (0–800 µL/mL, diluted with sterile water).

2.6. In Vitro Anti-Alpha Glucosidase Activity

The inhibitory activity of the extracts against α-glucosidase was evaluated using a method described by Pistia-Brueggeman and Hollingsworth [37], with slight modifications. Briefly, 50 µL of α-glucosidase solution (0.5 U/mL in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) was mixed with 50 µL of either the kombucha solution or acarbose and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Subsequently, 50 µL of 5 mM p-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (dissolved in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) was added and the mixture was further incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The absorbance was then measured at 405 nm using a spectrophotometer (Biochrom, Cambridge, UK). The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was established from the regression equation derived from plotting the percentage of inhibition against kombucha concentrations (0, 100, 200, 400, 600, and 800 uL/mL, diluted with sterile water).

2.7. Drosophila Strain, Culture Conditions, and Experimental Design

The wild-type D. melanogaster Oregon-R-C strain was donated by the Department of Biology at Khon Kaen University. The flies were housed in a wheat cream medium enriched with yeast powder at 25.1 ± 0.2 °C, 70–80% relative humidity, and subjected to a 12:12 light/dark cycle in a laboratory setting. Every two days, surviving flies were relocated to vials with fresh food.

For the preparation of the high-sugar diet (HSD), 30 g of sucrose was dissolved in 100 mL of sterile water. In the case of the HSD + pure C. rotundus kombucha diet, 30 g of sucrose was dissolved in 100 mL of undiluted kombucha. For the HSD + 400 µL/mL (40%) and HSD + 100 µL/mL (10%) kombucha diets, kombucha was initially diluted to concentrations of 400 and 100 µL/mL, respectively, with sterile water. Thereafter, 30 g of sucrose was incorporated into each 100 mL of the diluted solutions.

Experiments were conducted using 5–7-day-old female flies, which were divided into four groups: HSD, HSD+ pure kombucha, HSD + 400 (40%) µL/mL kombucha, and HSD + 100 (10%) µL/mL kombucha. Each group consisted of 100 flies, with 20 flies per vial. The diets for each group were poured on the cotton sheet that placed in the bottom of the test vial (2.0 × 9.5 cm). Flies were deprived for two hours in an empty vial containing cotton cloth saturated with sterile water prior to treatment. After being starved for two hours, the flies were transferred to the test and fed for 4 h. The flies were transferred to an empty vial following the feeding period. Following euthanasia with 5% CO2 fumigation, the flies were chilled for ten minutes at −20 °C. The euthanized flies were subsequently transferred to a 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube. The fly samples were washed three times with 1.0 mL of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer. The samples were then homogenized using a pestle in 1.0 mL of the same buffer. The homogenate was subjected to a 10-min centrifugation at 10,000 rpm and 4 °C in order to remove fly debris. The supernatant was transferred to new 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes and kept on ice during preparation for measurement of antioxidant activity (DPPH and ABTS assays, CAT and SOD activities, and lipid peroxidation assay), α-glucosidase activity, and protein content.

The research protocol received approval from the Ethics Committee of Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat University (Ethical Clearance No. AN63008).

2.8. In Vivo Antioxidant Activity

2.8.1. Scavenging DPPH Free Radical Activity Assay

The inhibitory effect on DPPH free radical activity in Drosophila homogenate was evaluated by mixing 180 μL of the supernatant with 20 μL of a 1 mM DPPH solution (solubilized in methanol). Reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at room temperature under no light. The absorbance at a wavelength of 517 nm was measured using an ELISA reader (Biochrome, UK) to determine the inhibitory effect. Each sample was examined three replicates. The inhibitory activity was calculated using the following formula:

| Inhibition (%) = ((Abs of control − Abs of sample)/(Abs of control)) × 100 |

where “Abs of the control” refers to the DPPH solution’s absorbance value without the sample.

The inhibitory activity was normalized to the protein content in the supernatant.

2.8.2. Scavenging ABTS Free Radical Activity Assay

The inhibitory effect on ABTS free radical activity in Drosophila homogenate was evaluated by mixing 20 μL of the supernatant with 180 μL of ABTS• solution. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. The absorbance at a wavelength of 734 nm was measured using an ELISA reader (Biochrome, UK) to determine the inhibitory effect. Each sample was examined three replicates. The inhibitory activity was calculated using the following formula:

| Inhibition (%) = ((Abs of control − Abs of sample)/(Abs of control)) × 100 |

where “Abs of the control” refers to the ABTS• solution’s absorbance value without the sample.

The inhibitory activity was normalized to the protein content in the supernatant.

2.8.3. SOD Activity

SOD activity was determined using a Sigma-Aldrich reagent in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions and the sample preparation procedure. Fruit flies (n = 100, 20/vial) were ground in 1 mL of cold buffer and then centrifuged (1500× g for 5 min at 4 °C) to remove any remaining material. The supernatant (900 µL) underwent another centrifugation (10,000× g for 15 min at 4 °C). This supernatant was then used to measure the activity of SOD1. To evaluate SOD2 activity, the resultant pellet was redissolved in 0.5 mL of cold buffer. Each test was performed three times.

2.8.4. CAT Activity

The activity of CAT was evaluated using a kit from Sigma-Aldrich that measures the remaining hydrogen peroxide after the CAT reaction. In a summarized process, flies (n = 100, 20/vial) were ground in 1 mL of cold enzyme dilution buffer and then centrifuged (1500× g for 5 min at 4 °C) to eliminate any waste. A portion of the supernatant (500 µL) was then diluted in 20 mL of the assay buffer. It was combined with 25 µL of hydrogen peroxide solution and, after 1 min, the reaction was halted using 900 µL of 15 mM sodium azide. Subsequently, a 10 µL sample was introduced to a color reagent, which consisted of 0.25 mM 4-aminoantipyrine, 2 mM 3,5-dichloro-2-hydroxybenzenesulfinic acid, and peroxidase (0.5–1.5 U/mg). After incubating for 15 min at ambient temperature, the absorbance was recorded at 520 nm using an instrument supplied by UK-based Biochrome. This assay was repeated three times for accuracy.

2.8.5. Measurement of Lipid Peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation was assessed using a modified method from Zeb and Ullah [38], employing the TBAR technique and taking malondialdehyde as a reference. In a concise process, a 500 µL portion of the fly homogenate was combined with 10 mL of TBA reagent. This mixture was then heated for 15 min, allowed to cool, and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min to remove any sediment. The absorbance of the remaining supernatant was recorded at 532 nm using a Biochrome instrument from the UK. The concentration of MDA was calculated based on a standard curve derived from 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane.

2.8.6. H2O2 and Paraquat Challenge Tests

In order to evaluate resistance to hydrogen peroxide and paraquat (superoxide anion), distinct sets of flies were utilized. Female flies, aged 5–7 days, were starved for 2 h before being transferred to containers with filter paper saturated with either a 20 mM paraquat solution or a 10% hydrogen peroxide solution. These solutions were either unaltered or supplemented with C. rotundus kombucha at concentrations of pure, 400 µL/mL, or 100 µL/mL, and each was prepared using a 6% sucrose solution. The number of deceased flies was noted at four-hour intervals until no flies remained alive.

2.9. In Vivo Anti-Alpha Glucosidase Activity

The glucosidase activity in Drosophila was evaluated by combining 50 μL of supernatant with 50 μL of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer and 50 μL of 5 mM p-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (dissolved in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer). The reaction mixtures were incubated at ambient temperature for 30 min. The glucosidase activity was quantified at a wavelength of 405 nm using an ELISA reader (Biochrome, UK). The standard curve for alpha-glucosidase was established by plotting the optical density at 405 nm against enzyme concentrations ranging from 0.03–0.5 U/mL. Each specimen was examined in triplicate. The activities of the enzymes were adjusted to the protein concentration in the supernatant.

2.10. Protein Content Assay

The protein content of the homogenate derived from the entire body was determined using the Bradford (1976) method and Merck’s Bradford reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Concentrations were determined in mg/mL using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

The data were statistically analyzed using SPSS 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). One-way ANOVA was used for mean comparisons. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to determine the difference in survival curves. Statistical significance was defined as a p < 0.05. The significance levels for each experiment were denoted by the symbols * for p < 0.05 and ** for p < 0.01.

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Profiles of C. rotundus Kombucha

Table 1 shows the GC-MS-identified compounds of C. rotundus kombucha. It has been documented that the following compounds in kombucha exhibit biological activity: 3,5-dimethylpyrazole, 4H-pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl, 2-(4-methyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)ethan-1-amine, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural, 10-azido-1-decanethiol, 3-deoxy-D-mannoic lactone, 1-.beta.-d-ribofuranosyl-3-[5-tetraazolyl]-1,2,4-triazole, Nona-2,3-dienoic acid, ethyl ester, and stigmasterol.

Table 1.

The GC-MS profiling of Cyperus rotundus kombucha ferment.

| No. | Name | Chemical Formula | RT | Previously Reported Biological Activity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3,5-Dimethylpyrazole | C5H8N2 | 3.712 | Hypoglycemic activity Anti-aging |

[39,40] |

| 2 | Benzen-d5-amine | C6H2D5N | 4.008 | Not reported | NA |

| 3 | 5-.alpha.-Aminoethyltetrazole | C3H7N5 | 5.156 | Not reported | NA |

| 4 | 2,4-Dihydroxy-2,5-dimethyl-3(2H)-furan-3-one | C6H8O4 | 6.112 | Flavourant | [41] |

| 5 | Xylopyranoside, methyl-4-azido-4-deoxy-, .beta.-L | C6 H11N3O4 | 6.475 | Not reported | NA |

| 6 | Propylamine, N,N,2,2-tetramethyl-, N-oxide | C7H17N O | 6.992 | Not reported | NA |

| 7 | Furaneol | C6H8O3 | 7.546 | Not reported | NA |

| 8 | 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl | C6H8O4 | 9.535 | Antioxidant activity | [42] |

| 9 | Butyl-tert-butylisopropoxyborane | C11H25BO | 10.119 | Not reported | NA |

| 10 | 1-Tetrazol-2-ylethanone | C3H4N4O | 10.224 | Not reported | NA |

| 11 | 2-(4-Methyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)ethan-1-amine | C5H10N4 | 10.587 | Antioxidant, anti-proliferative, and anti-atherosclerotic activities |

[43] |

| 12 | Lactic acid, 2-methyl-, monoanhydride with 1-butaneboronic acid, cyclic ester | C8H15BO3 | 10.606 | Not reported | NA |

| 13 | 1-Tetrazol-2-ylethanone | C3H4N4O | 10.903 | Not reported | NA |

| 14 | Borinic acid, diethyl- | C4H11BO | 10.684 | Not reported | NA |

| 15 | 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural | C6H6O3 | 11.294 | Anticancer activity | [44] |

| 16 | 10-Azido-1-decanethiol | C10H21N3S | 12.604 | Anti-fungal activity | [45] |

| 17 | .beta.-D-Glucosyloxyazoxymethane | C8H16N2O7 | 13.532 | Not reported | NA |

| 18 | Ethanone, 1,1’-(2-ethyl-4,5-dimethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolane-4,5-diyl)bis | C10H17BO4 | 14.144 | Not reported | NA |

| 19 | 1,3,2-Dioxaborolane, 2-ethyl-4-(3-oxiranylpropyl)- | C9H17BO3 | 15.330 | Not reported | NA |

| 20 | Ethanone, 1-[5-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-2-ethyl-4-methyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-4-yl]- | C11H21BO3 | 18.036 | Not reported | NA |

| 21 | 3- Deoxy-D-mannoic lactone | C6H10O5 | 18.629 | Antibacterial activity Antioxidant and alpha-glucosidase inhibitor activities |

[46,47] |

| 22 | 1-.beta.-d-Ribofuranosyl-3-[5-tetraazolyl]-1,2,4-triazole | C8H11N7O4 | 21.239 | Analgesics, antipyretics, anti-convulsants, anti-inflammatory, immune modulatory activity | [48] |

| 23 | Nona-2,3-dienoic acid, ethyl ester | C11H18O2 | 24.949 | Antiviral activity | [49] |

| 24 | Stigmasterol | C29H48O | 29.530 | Anti-osteoarthritic activity Anti-hypercholestrolemic activity Anti-tumor Antioxidant Antimutagenic activity Anti-inflammatory activity CNS activities |

[50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58] |

NA = Not available.

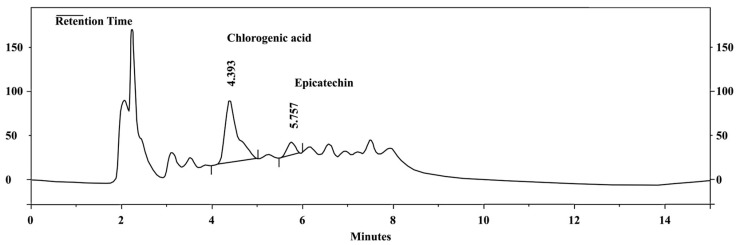

The phytochemical compounds of C. rotundus kombucha, analyzed using HPLC, are presented in Figure 1. The concentrations of chlorogenic acid and epicatechin were quantified using a standard curve. The range for chlorogenic acid was 3.13–50.00 µg/mL, described by the equation Y = 273,991x + 788,198. The range for epicatechin was 1.56–50.00 µg/mL, given by the equation Y = 166,769x + 560,043. As demonstrated in Figure 1, chlorogenic acid and epicatechin were detected at the concentration of 6.04 and 1.07 µg/g, respectively.

Figure 1.

The HPLC chromatograms of C. rotundus kombucha reveal the presence of chlorogenic acid and epicatechin.

3.2. Effects of C. rotundus Kombucha on In Vitro and In Vivo Antioxidant Activity

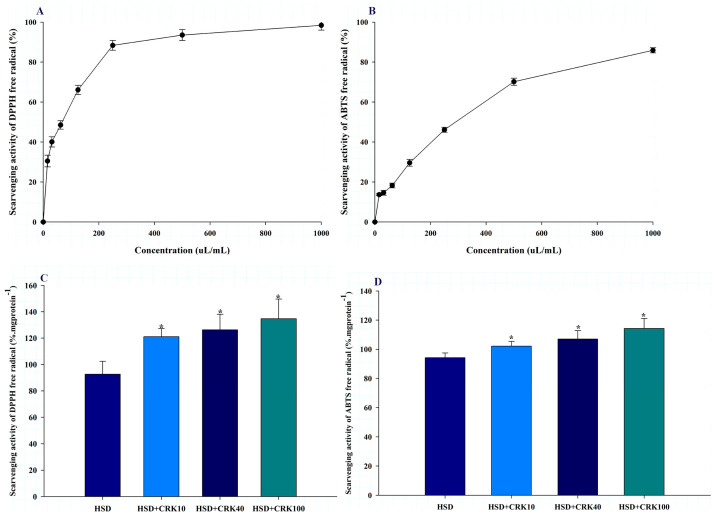

The antioxidant properties of C. rotundus kombucha were evaluated using two distinct assays: DPPH and ABTS. In the evaluation, the kombucha solution produced by C. rotundus exhibited significant antioxidant properties. For the DPPH assay, the IC50 was calculated to be 76.7 ± 9.6 µL/mL (Figure 2A). The IC50 value for the kombucha solution in the ABTS assay was 314.2 ± 16.9 µL/mL (Figure 2B). The antioxidant findings suggest that C. rotundus kombucha has significant antioxidant potential, as evidenced by its significant inhibitory activity at low concentrations. Consequently, consuming C. rotundus kombucha may provide the body with a beneficial source of antioxidants.

Figure 2.

The effects of C. rotundus kombucha on both in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activities. (A,B) The % inhibition of DPPH and ABTS free radicals in vitro, respectively. (C,D) the mean ± SD of % inhibition of DPPH and ABTS free radicals in Drosophila fed with a high-sugar diet (HSD), HSD supplemented with 10% C. rotundus kombucha (HSD + CRK10), HSD supplemented with 40% C. rotundus kombucha (HSD + CRK40), and HSD supplemented with 100% C. rotundus kombucha (HSD + CRK100), respectively. The One-Way ANOVA test was employed to determine differences among groups. * indicates statistically significant differences compared to the control group at p < 0.05.

The antioxidant potential of C. rotundus kombucha, as observed in vitro, was further confirmed in vivo using Drosophila as a test model, employing DPPH and ABTS assays. As shown in Figure 2C, Drosophila consuming a high-sugar diet supplemented with 100% kombucha exhibited a 45.44% increase in DPPH free radical scavenging activity relative to those consuming a high-sugar diet alone (p < 0.01). When the same diet was supplemented with 40% or 10% C. rotundus kombucha, the scavenging efficiency increased by 36.35% and 30.74%, respectively, compared to the HSD group (p < 0.05). Similar to the DPPH results, Drosophila on a high-sugar diet supplemented with 100% kombucha demonstrated a 21.22% increase in the ABTS free radical scavenging capacity compared to the HSD group (p < 0.01). Adding 40% or 10% C. rotundus kombucha to the diet increased scavenging rates by 13.52% and 8.39%, respectively, compared to the HSD group (p < 0.05) (Figure 2D). The findings of this study indicate that C. rotundus kombucha has significant antioxidant properties when consumed. This suggests that C. rotundus kombucha may be a beneficial beverage for reducing oxidative stress caused by free radicals.

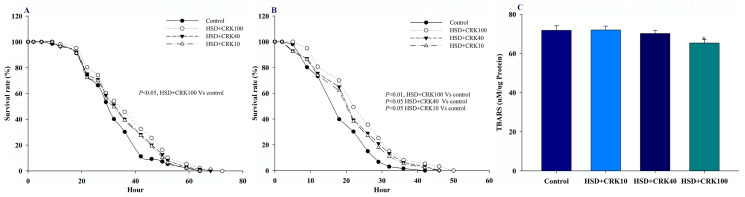

Figure 3A illustrates the effect of C. rotundus kombucha on the resistance of Drosophila on a high-sugar diet to H2O2-induced oxidative stress. When compared to the Drosophila group on a high-sugar diet, those fed with pure kombucha on a high-sugar diet experienced a rise in their maximum and 50% survival rates by 13.23% and 12.52%, respectively (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

The effect of C. rotundus kombucha supplementation on hydrogen peroxide (A) and paraquat (B) resistance and lipid peroxidation (C) in Drosophila fed a high-sugar diet (HSD), HSD supplemented with 10% C. rotundus kombucha (HSD + CRK10), HSD supplemented with 40% C. rotundus kombucha (HSD + CRK40), and HSD supplemented with 100% C. rotundus kombucha (HSD + CRK100). Survival was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier and log-rank tests. Differences were considered significant when the p value was less than 0.05. * indicates statistically significant differences compared to the HSD group at p < 0.05.

Figure 3B illustrates the effect of C. rotundus kombucha on the resistance of Drosophila fed a high-sugar diet to oxidative stress induced by paraquat. Compared to the group on a high-sugar diet alone, the Drosophila administered pure kombucha in addition to a high-sugar diet exhibited increases in their maximum and 50% survival rates by 21.74% and 23.67%, respectively (p < 0.01).

In this study, we evaluated the overall body lipid peroxidation (LPO) level to validate the antioxidant effects. As depicted in Figure 3C, Drosophila that consumed a high-sugar diet supplemented with pure kombucha demonstrated a notable reduction in LPO levels in comparison to the control group (p < 0.05).

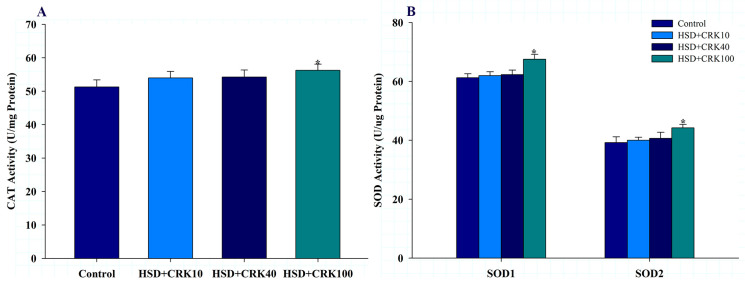

The results shown in Figure 4A,B indicate that when the high-sugar diet was enriched with pure kombucha, there was a significant increase in CAT, SOD1, and SOD2 activities, compared to Drosophila that consumed only a high-sugar diet (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

CAT (A) and SOD1 and SOD2 (B) levels in Drosophila fed a high-sugar diet (HSD), HSD supplemented with 10% C. rotundus kombucha (HSD + CRK10), HSD supplemented with 40% C. rotundus kombucha (HSD + CRK40), and HSD supplemented with 100% C. rotundus kombucha (HSD + CRK100). Data are presented as the mean ± SD. The One-Way ANOVA test was employed to determine differences among groups. * indicates statistically significant differences compared to the HSD group at p < 0.05.

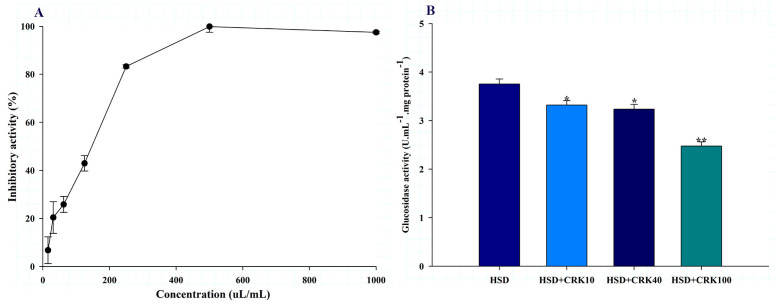

3.3. Effects of C. rotundus Kombucha on In Vitro and In Vivo Alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

The alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity of the C. rotundus kombucha is shown in Figure 5A. The kombucha solution produced by C. rotundus showed inhibition potential with IC50 values of 142.7 ± 5.2 µL/mL. This result suggests that C. rotundus kombucha may function as an anti-diabetic beverage by inhibiting sugar absorption and, consequently, regulating blood glucose levels, thereby potentially preventing insulin resistance.

Figure 5.

The effect of C. rotundus kombucha on the inhibition of α-glucosidase activity in vitro and in vivo. (A) The % inhibition of α-glucosidase activity in vitro. (B) α-glucosidase activity in Drosophila fed a high-sugar diet (HSD), HSD supplemented with 10% C. rotundus kombucha (HSD + CRK10), HSD supplemented with 40% C. rotundus kombucha (HSD + CRK40), and HSD supplemented with 100% C. rotundus kombucha (HSD + CRK100). The One-Way ANOVA test was employed to determine differences among groups. * and ** indicate statistically significant differences compared to the HSD group at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively.

The in vitro observation of the inhibitory effect of C. rotundus kombucha on alpha-glucosidase activity was confirmed in vivo using a Drosophila model. As shown in Figure 5B, Drosophila fed a high-sugar diet supplemented with 100% kombucha demonstrated a 34.04% decrease in glucosidase activity compared to those fed a high-sugar diet alone (p < 0.001). When the high-sugar diet was supplemented with either 40% or 10% C. rotundus kombucha, glucosidase activity decreased by 13.79% (p < 0.05) and 11.60% (p < 0.05), respectively, compared to Drosophila fed only the high-sugar diet. These results demonstrate in vitro and in vivo that C. rotundus kombucha significantly reduces glucosidase activity, indicating a possible anti-diabetic effect.

4. Discussion

C. rotundus is a plant that has been used as medicine and food to promote health for a long time. Biological and pharmacological studies have been conducted both in vitro and in animals that demonstrate the beneficial effects of this plant. Therefore, the application of this plant in developing functional food to maintain health or prevent disease is very attractive. The purpose of this study was to process rhizomes and tubers into kombucha, a beverage that recently gained increasing recognition. To determine its health benefits, we investigated the antioxidant and anti-diabetic properties of C. rotundus kombucha both in vitro and in vivo. Our results revealed that C. rotundus kombucha exhibits potent antioxidant activity, particularly in scavenging DPPH and ABTS free radicals. Our findings suggest that Drosophila treated with kombucha are more resistant to oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide and paraquat. This highlights the potent antioxidant properties of C. rotundus kombucha and indicates at the mechanism underlying its action.

Maintaining an appropriate balance between ROS production and elimination by various enzymatic and non-enzymatic agents is essential for cellular survival. In our research, we found that Drosophila treated with C. rotundus kombucha on a high-sugar diet exhibited enhanced activity of antioxidant enzymes, including SOD1, SOD2, and CAT, in comparison to flies on a high-sugar diet alone. This result is consistent with the findings of Wongchum et al. [26], who reported that the hydroethanolic extract from C. rotundus rhizome reduced paraquat-induced oxidative stress and increased the activity of antioxidant enzymes. Based on the chemical constituents found in the C. rotundus kombucha, Li et al. [59] showed that catechins from green tea can enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes in Drosophila. The antioxidant capabilities of extracts might be attributed to the presence of phenols, flavonoids, and various other chemical constituents. GC-MS and HPLC analysis detected antioxidant-containing compounds, including 2-(4-methyl-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)ethan-1-amine [43], 4H-pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl [42], 3-deoxy-D-mannoic lactone [47], stigmasterol [55], chlorogenic acid [60], and epicatechin [61]. The results of this study, combined with previous research, strongly suggest that the antioxidant potential of C. rotundus kombucha is linked to its antioxidant capacity and the activation of antioxidant enzymes.

A significant risk factor for the development of type-2 diabetes, which is characterized by elevated blood glucose levels, insulin resistance, and insufficient insulin secretion, is a high sugar intake. Reducing the activity of alpha-glucosidase is essential for managing and treating type-2 diabetes [27]. Similar to mammalian systems, Drosophila is a valuable model for investigating the anti-diabetic effects of natural substances [32]. Research has shown that a high-sugar diet leads to elevated blood sugar, insulin resistance, increased fat storage, and reduced life expectancy in Drosophila [35]. In addition, studies have revealed that fruit flies contain the glucosidase enzyme, which is essential for sugar absorption. In this study, we found that C. rotundus kombucha inhibited in vitro alpha-glucosidase activity with an IC50 of 142.7 ± 5.2 µL/mL. Compared to other plants, the review by Kashtoh and Baek [62] reported that the IC50 values for glucosidase activity varied from 0.53 ± 0.014 µg/mL to 1.873 ± 0.421 mg/mL. This suggests that C. rotundus kombucha is among the potent inhibitors. Our in vitro findings were verified in Drosophila; we observed a significant decrease in glucosidase activity in Drosophila fed a high-sugar diet supplemented with kombucha compared to those fed only a high-sugar diet. According to GC-MS and HPLC analysis, kombucha contains phytochemical compounds with anti-glucosidase properties. The evidence indicates that 3-deoxy-D-mannoic lactone derived from Distichochlamys citrea effectively inhibits α-glucosidase activity both in vitro and in silico [47]. Studies have shown that plant-derived stigmasterol can inhibit alpha-glucosidase activity [63,64,65]. Wang et al. [66] reported that chlorogenic acid inhibited alpha-glucosidase activity, similar to acarbose. Therefore, based on our findings and prior research, we suggest that C. rotundus kombucha might act as a preventative measure against diabetes by limiting dietary sugar absorption. Nonetheless, further studies are essential to comprehensively understand the underlying mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

Our research highlights the variety of health benefits associated with C. rotundus, which has been utilized historically for medicinal and dietary intentions. The processing of rhizomes and tubers of C. rotundus into kombucha, an increasingly popular health beverage, showed significant antioxidant properties, specifically in the inhibition of DPPH and ABTS free radicals. Furthermore, our study provides evidence that C. rotundus kombucha has been shown to enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes (SOD1, SOD2, and CAT) in Drosophila in response to oxidative stress; this result is consistent with findings from previous research. The analysis of its components showed a diverse collection of compounds abundant in antioxidants. We observed that kombucha inhibited alpha-glucosidase activity in the context of type-2 diabetes, indicating that it may have the ability to reduce dietary sugar absorption. In conclusion, our study provides preliminary evidence supporting the potential of C. rotundus kombucha as an herbal remedy for enhancing antioxidant levels and preventing type-2 diabetes. In accordance with contemporary health demands and trends, we recommend further development of kombucha as a functional beverage intended to promote overall health and reduce the risk of chronic metabolic diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Faculty of Thai Traditional and Alternative Medicine, Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat University and Research Unit of Thai Food Innovation, Department of Food Technology and Nutrition, Mahasarakham University, for providing instruments. We thank Chakkapong Thangthong, Plant Taxonomist, Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat University, for his assistance with plant identification. We thank Monthira Monthatong, Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Thailand, for providing the wild-type Drosophila.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript, A.D. Conceptualization, Supervision, Reviewing and Editing: A.T. and S.P. Conducted the experiments: N.W. and T.C. Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing—Reviewing and Editing and obtained funding: S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research protocol received approval from the Ethics Committee of Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat University (Ethical Clearance No. AN63008).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) and Mahasarakham University.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Pirzada A.M., Ali H.H., Naeem M., Latif M., Bukhari A.H., Tanveer A. Cyperus rotundus L.: Traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacological activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;174:540–560. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yazdanparast R., Ardestani A. In vitro antioxidant and free radical scavenging activity of Cyperus rotundus. J. Med. Food. 2007;10:667–674. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2006.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hema N., Avadhani R., Ravishankar B., Anupama N. A comparative analysis of antioxidant potentials of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of Cyperus rotundus (L.) Asian. J. Biomed. Pharm. Sci. 2013;3:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu Q.P., Cao X.M., Hao D.L., Zhang L.L. Chemical composition, antioxidant, DNA damage protective, cytotoxic and antibacterial activities of Cyperus rotundus rhizomes essential oil against foodborne pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:45231. doi: 10.1038/srep45231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raut N.A., Gaikwad N.J. Antidiabetic activity of hydro-ethanolic extract of Cyperus rotundus in alloxan induced diabetes in rats. Fitoterapia. 2006;77:585–588. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tran H.H., Nguyen M.C., Le H.T., Nguyen T.L., Pham T.B., Chau V.M., Nguyen H.N., Nguyen T.D. Inhibitors of α-glucosidase and α-amylase from Cyperus rotundus. Pharm. Biol. 2014;52:74–77. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2013.814692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Athesh K., Divakar M., Brindha P. Anti-obesity potential of Cyperus rotundus L. aqueous tuber extract in rats fed on high fat cafeteria diet. Asian. J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2014;7:88–92. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin J.H., Lee D.U., Kim Y.S., Kim H.P. Anti-allergic activity of sesquiterpenes from the rhizomes of Cyperus rotundus. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2011;34:223–228. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-0207-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aeganathan R., Rayar A., Ilayaraja S., Prabakaran K., Manivannan R. Anti-oxidant, antimicrobial evaluation and GC-MS analysis of Cyperus rotundus L. rhizomes chloroform fraction. Am. J. Ethnomedicine. 2015;2:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daswani P.G., Brijesh S., Tetali P., Birdi T.J. Studies on the activity of Cyperus rotundus Linn. tubers against infectious diarrhea. Indian. J. Pharmacol. 2011;43:340. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.81502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nazish J., Shoukat A. Cardioprotective and antilipidemic potential of Cyperus rotundus in chemically induced cardiotoxicity. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2012;14:989–992. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Güldür M.E., Ozgönül A., Kilic I.H., Sögüt O., Ozaslan M., Bitiren M., Yalcin M., Musa D. Gastroprotective effect of Cyperus rotundus extract against gastric mucosal injury induced by ischemia and reperfusion in rats. IJP-Int. J. Pharmacol. 2010;6:104–110. doi: 10.3923/ijp.2010.104.110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parvez M.K., Al-Dosari M.S., Arbab A.H., Niyazi S. The in vitro and in vivo anti-hepatotoxic, anti-hepatitis B virus and hepatic CYP450 modulating potential of Cyperus rotundus. Saudi. Pharm. J. 2019;27:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soumaya K.J., Dhekra M., Fadwa C., Zied G., Ilef L., Kamel G., Leila C.G. Pharmacological, antioxidant, genotoxic studies and modulation of rat splenocyte functions by Cyperus rotundus extracts. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013;13:28. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehdizadeh M., Hashem Dabaghian F., Shojaee A., Molavi N., Taslimi Z., Shabani R., Soleimani Asl S. Protective effects of Cyperus rotundus extract on amyloid β-peptide (1-40)-induced memory impairment in male rats: A behavioral study. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 2017;8:249. doi: 10.18869/nirp.bcn.8.3.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutalangka C., Wattanathorn J. Neuroprotective and cognitive-enhancing effects of the combined extract of Cyperus rotundus and Zingiber officinale. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017;17:135. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1632-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simorangkir D., Masfria M., Harahap U., Satria D. Activity anticancer n-hexane fraction of Cyperus rotundus L. Rhizome to breast cancer MCF-7 cell line. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019;7:3904. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2019.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biradar S., Kangralkar V.A., Mandavkar Y., Thakur M., Chougule N. Antiinflammatory, antiarthritic, analgesic and anticonvulsant activity of Cyperus essential oils. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2010;2:112–115. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsoyi K., Jang H.J., Lee Y.S., Kim Y.M., Kim H.J., Seo H.G., Lee J.H., Kwak J.H., Lee D.U., Chang K.C. (+)-Nootkatone and (+)-valencene from rhizomes of Cyperus rotundus increase survival rates in septic mice due to heme oxygenase-1 induction. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137:1311–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocha F.G., Brandenburg M.M., Pawloski P.L., Soley B.D.S., Costa S.C.A., Meinerz C.C., Baretta I.P., Otuki M.F., Cabrini D.A. Preclinical study of the topical anti-inflammatory activity of Cyperus rotundus L. extract (Cyperaceae) in models of skin inflammation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020;254:112709. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma A., Verma R., Ramteke P. Cyperus rotundus: A potential novel source of therapeutic compound against urinary tract pathogens. J. Herb. Med. 2014;4:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2014.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shivakumar S.I., Suresh H.M., Hallikeri C.S., Hatapakki B.C., Handiganur J.S., Kuber S., Shivakumar B. Anticonvulsant effect of Cyperus rotundus Linn rhizomes in rats. J. Nat. Remedies. 2009;9:192–196. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Z.L., Yin W.Q., Yang Y.M., He C.H., Li X.N., Zhou C.P., Guo H. New iridoid glycosides with antidepressant activity isolated from Cyperus rotundus. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2016;64:73–77. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c15-00686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wongchum N., Dechakhamphu A., Chaweerak S., Pinlaor S., Tanomtong A. Evaluation of aqueous and ethanol extracts of Cyperus rotundus L. on sexual behaviours and reproductive fitness in Drosophila melanogaster. Pharm. Sci. Asia. 2021;48:516–522. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wongchum N., Dechakhamphu A., Ma-ding A., Khamphaeng T., Pinlaor S., Pinmongkhonkul S., Tanomtong A. The effects of Cyperus rotundus L. extracts on the longevity of Drosophila melanogaster. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022;148:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2022.04.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wongchum N., Dechakhamphu A., Panya P., Pinlaor S., Pinmongkhonkul S., Tanomtong A. Hydroethanolic Cyperus rotundus L. extract exhibits anti-obesity property and increases lifespan expectancy in Drosophila melanogaster fed a high-fat diet. J. Herbmed. Pharmacol. 2022;11:296–304. doi: 10.34172/jhp.2022.35. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hossain U., Das A.K., Ghosh S., Sil P.C. An overview on the role of bioactive α-glucosidase inhibitors in ameliorating diabetic complications. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020;145:111738. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghani U. Re-exploring promising α-glucosidase inhibitors for potential development into oral anti-diabetic drugs: Finding needle in the haystack. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;103:133–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apovian C.M., Okemah J., O’Neil P.M. Body weight considerations in the management of type 2 diabetes. Adv. Ther. 2019;36:44–58. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0824-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.da Silva Júnior J.C., Mafaldo Í.M., de Lima Brito I., de Magalhães Cordeiro A.M.T. Kombucha: Formulation, chemical composition, and therapeutic potentialities. Curr. Res. Food. Sci. 2022;5:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.crfs.2022.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morales D. Biological activities of kombucha beverages: The need of clinical evidence. Trends. Food. Sci. Technol. 2020;105:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.09.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palanker Musselman L., Fink J.L., Narzinski K., Ramachandran P.V., Sukumar Hathiramani S., Cagan R.L., Baranski T.J. A high-sugar diet produces obesity and insulin resistance in wild-type Drosophila. Dis. Model. Mech. 2011;4:842–849. doi: 10.1242/dmm.007948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Partridge L., Alic N., Bjedov I., Piper M.D. Ageing in Drosophila: The role of the insulin/Igf and TOR signalling network. Exp. Gerontol. 2011;46:376–381. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris S.N.S., Coogan C., Chamseddin K., Fernandez-Kim S.O., Kolli S., Keller J.N., Bauer J.H. Development of diet-induced insulin resistance in adult Drosophila melanogaster. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. BBA-Mol. Basis. Dis. 2012;1822:1230–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Na J., Musselman L.P., Pendse J., Baranski T.J., Bodmer R., Ocorr K., Cagan R. A Drosophila model of high sugar diet-induced cardiomyopathy. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanimura T., Kitamura K., Fukuda T., Kikuchi T. Purification and partial characterization of three forms of α-glucosidase from the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biochem. 1979;85:123–130. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pistia-Brueggeman G., Hollingsworth R.I. A preparation and screening strategy for glycosidase inhibitors. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:8773–8778. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)00877-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeb A., Ullah F. A simple spectrophotometric method for the determination of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances in fried fast foods. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2016;2016:9412767. doi: 10.1155/2016/9412767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerritsen G.C., Dulin W.E. Effect of a new hypoglycemic agent, 3, 5-dimethylpyrazole, on carbohydrate and free fatty acid metabolism. Diabetes. 1965;14:507–515. doi: 10.2337/diab.14.8.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cavallini G., Donati A., Bergamini E. Antiaging Therapy: A Novel Target for Antilipolytic Drugs. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2014;14:551–556. doi: 10.2174/1389557514666140622205540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chukwu C., Omaka O., Aja P. Characterization of 2, 5-dimethyl-2, 4-dihydroxy-3 (2H) furanone, a flavourant principle from Sysepalum dulcificum. Nat. Prod. Chem. Res. 2017;5:2. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dilek Tepe H., Doyuk F. Determination of phytochemical content by chromatographic methods and antioxidant capacity in methanolic extract of jujube (Zizyphus jujuba Mill.) and oleaster (Elaeagnus a ngustifolia L.) Int. J. Fruit. Sci. 2020;20:S1876–S1890. doi: 10.1080/15538362.2020.1834900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Priyaa G.H., More S.S. Antioxidant, anti-proliferative, and anti-atherosclerotic effect of phytochemicals isolated from Trachyspermum ammi with honey in RAW 264.7 and THP-1 cells. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2022;18:143–151. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joel O.O., Maharjan R. Effects of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural isolated from Cola hispida on oral adenosquamous carcinoma and MDR Staphylococcus aureus. JMPHTR. 2021;8:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doughari J.H., Abraham M. Antifungal activity of Jatropha Curcas Linn on Candida albicans and Candida tropicalis associated with neonatal and infantile infections in Yola, Nigeria. Am. J. Agric. Biol. Sci. 2021;16:19–32. doi: 10.3844/ajabssp.2021.19.32. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shobana S., Vidhya V., Ramya M. Antibacterial activity of garlic varieties (ophioscordon and sativum) on enteric pathogens. Curr. Res. J. Biol. Sci. 2009;1:123–126. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Chen T., Cuong T.D., Quy P.T., Bui T.Q., Van Tuan L., Van Hue N., Triet N.T., Ho D.V., Bao N.C., Nhung N.T.A. Antioxidant activity and α-glucosidase inhibitability of Distichochlamys citrea MF Newman rhizome fractionated extracts: In vitro and in silico screenings. Chem. Pap. 2022;76:5655–5675. doi: 10.1007/s11696-022-02273-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kakarla L. Comparative Biochemical Studies on Indian Sedges Cyperus scariosus R Br and Cyperus rotundus L. Pharmacogn. J. 2017;8:598–609. doi: 10.5530/pj.2016.6.14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang X., Li J., Hong Y., Jiang C., Wu J., Wu M., Sheng R., Liu H., Sun J., Xin Y., et al. Antiviral effects of the petroleum ether extract of Tournefortia sibirica L. against enterovirus 71 infection in vitro and in vivo. Front. Pharmacol. 2022;13:999798. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.999798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gabay O., Sanchez C., Salvat C., Chevy F., Breton M., Nourissat G., Wolf C., Jacques C., Berenbaum F. Stigmasterol: A phytosterol with potential anti-osteoarthritic properties. Osteoarthritis. Cartil. 2010;18:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chandler R.F., Hooper S.N., Ismail H.A. Antihypercholesterolemic studies with sterols: Beta-sitosterol and stigmasterol. J. Pharm. Sci. 1979;68:245–247. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600680235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Batta A.K., Xu G., Honda A., Miyazaki T., Salen G. Stigmasterol reduces plasma cholesterol levels and inhibits hepatic synthesis and intestinal absorption in the rat. Metabolism. 2006;55:292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kasahara Y., Kumaki K., Katagiri S., Yasukawa K., Yamanouchi S., Takido M., Akihisa T., Tamura T. Carthami flos extract and its component, stigmasterol, inhibit tumour promotion in mouse skin two-stage carcinogenesis. Phytother. Res. 1994;8:327–331. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2650080603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao Z., Maloney D.J., Dedkova L.M., Hecht S.M. Inhibitors of DNA polymerase β: Activity and mechanism. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:4331–4340. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Panda S., Jafri M., Kar A., Meheta B. Thyroid inhibitory, antiperoxidative and hypoglycemic effects of stigmasterol isolated from Butea monosperma. Fitoterapia. 2009;80:123–126. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lim J.C., Park J.H., Budesinsky M., Kasal A., Han Y.H., Koo B.S., Lee S.I., Lee D.U. Antimutagenic constituents from the thorns of Gleditsia sinensis. Chem. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005;53:561–564. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Navarro A., De Las Heras B., Villar A. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating properties of a sterol fraction from Sideritis foetens Clem. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2001;24:470–473. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Garcia M., Saenz M., Gomez M., Fernández M. Topical antiinflammatory activity of phytosterols isolated from Eryngium foetidum on chronic and acute inflammation models. Phytother. Res. Int. J. Devoted. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Eval. Nat. Prod. Deriv. 1999;13:78–80. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(199902)13:1<78::AID-PTR384>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Y.M., Chan H.Y.E., Huang Y., Chen Z.Y. Green tea catechins upregulate superoxide dismutase and catalase in fruit flies. Mol. Nutr. Food. Res. 2007;51:546–554. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200600238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Singh A.K., Singla R.K., Pandey A.K. Chlorogenic acid: A dietary phenolic acid with promising pharmacotherapeutic potential. Curr. Med. Chem. 2023;30:3905–3926. doi: 10.2174/0929867329666220816154634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sheng Y., Sun Y., Tang Y., Yu Y., Wang J., Zheng F., Li Y., Sun Y. Catechins: Protective mechanism of antioxidant stress in atherosclerosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2023;14:1144878. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1144878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kashtoh H., Baek K.H. Recent updates on phytoconstituent alpha-glucosidase inhibitors: An approach towards the treatment of type two diabetes. Plants. 2022;11:2722. doi: 10.3390/plants11202722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Junejo J.A., Zaman K., Rudrapal M., Celik I., Attah E.I. Antidiabetic bioactive compounds from Tetrastigma angustifolia (Roxb.) Deb and Oxalis debilis Kunth.: Validation of ethnomedicinal claim by in vitro and in silico studies. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021;143:164–175. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2021.07.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lolok N., Sumiwi S.A., Ramadhan D.S.F., Levita J., Sahidin I. Molecular dynamics study of stigmasterol and beta-sitosterol of Morinda citrifolia L. towards α-amylase and α-glucosidase. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023:1–4. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2023.2243519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tasnuva S.T., Qamar U.A., Ghafoor K., Sahena F., Jahurul M.H.A., Rukshana A.H., Juliana M.J., Al-Juhaimi F.Y., Jalifah L., Jalal K.C.A., et al. α-glucosidase inhibitors isolated from Mimosa pudica L. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019;33:1495–1499. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2017.1419224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang S., Li Y., Huang D., Chen S., Xia Y., Zhu S. The inhibitory mechanism of chlorogenic acid and its acylated derivatives on α-amylase and α-glucosidase. Food Chem. 2022;372:131334. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.