Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have difficulties that limit their opportunities to interact with peers and family members. These behaviors can lead to social exclusion, and consequently social isolation. The aim was to compare social isolation of children and adolescents with ASD according to age, marital status, and number of siblings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Cross-sectional descriptive study in 37 subjects with ASD. Social isolation was assessed using a 6-item scale (with five alternatives). The sociodemographic variables were age, sex, marital status of parents, and number of siblings. Two groups were formed according to age (children from 4 to 10 years old and adolescents from 11 to 20 years old).

RESULTS:

For the total score of the social isolation scale, children showed a higher score (21.1 ± 4.7) than adolescents (17.7 ± 5.7). Children living with divorced parents had lower scores (16.2 ± 3.6), compared to married (22.2 ± 4.5) and cohabiting (22.8) children. For the number of siblings, with no siblings 17.2 ± 3.1 points, one sibling 22.2 ± 3.5 points, two siblings 22.1 ± 3.1 points, and three siblings 22.4 ± 3.2 points (P < 0.05). Age was related to social isolation (r = −0.30, P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION:

Children who live with divorced parents and have no siblings presented a higher degree of isolation in relation to their counterparts who live with both parents and have at least one sibling. Age plays a relevant role, with children aged 4–10 years presenting a lower degree of isolation than the adolescent group. It is suggested that the preservation of a functional family and the presence of siblings could contribute to improving social isolation.

Keywords: Adolescents, age, ASD, children, siblings, social isolation

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impaired reciprocal social communication and a pattern of restrictive, often non-adaptive, repetitive behaviors, interests, and activities.[1]

It has a neurobiological origin and accompanies the person throughout life, and it is affected mainly in two areas of the person's development, such as communication and social interaction, and flexibility of thought and behavior.[2]

Children and adolescents with ASD have language difficulties and may show antisocial behaviors such as aggression, withdrawal, or even seek self-stimulation, sometimes in response to stress or changes in routine.[3]

In fact, several studies in recent years have shown that common experiences among children with ASD include obsession, impaired social relationships, irregular levels of cognitive and intellectual functioning, language abnormalities, academic performance, parental stigmatization,[3,4,5,6] among others.

These social difficulties prevalent in children with ASD limit their opportunities to interact with peers and family members. In that sense, for parents, these behaviors can lead to social exclusion, and consequently social isolation.[7]

Indeed, social isolation of individuals with ASD is a concern shared by multiple stakeholder groups, including autism advocates, caregivers, and providers.[8] Classically, it has been defined by the US Institute of Medicine, IMEU,[9] as the absence of social interactions, contacts, and relationships with family and friends, with neighbors on an individual level and with “society at large” on a broader level.

Recently, the Oxford University Department of International Development defined social isolation as “the inadequate quality and quantity of social relationships with other people at the individual, group, community and broader social environment where human interaction takes place”.[10]

In general, it includes objective and/or subjective elements.[10] For example, objective social isolation relates to the actual amount of social contact someone has. However, subjective social isolation relates to the perceived adequacy of the quantity or quality of social relationships. It also incorporates concepts, such as perceived social support;[11] for example, loneliness is a form of subjective social isolation.

Consequently, caregivers and family members play an important role in supporting people with ASD throughout their lives,[12] so social support has been used and continues to be considered as an indicator of the degree of social isolation and may serve as a determinant in predicting the risk of disease and dysfunction.[9]

In that context, based on the fact that parents must educate, instruct, nurture, and care for children throughout childhood and adolescence, raising a child with ASD poses several unique challenges that may affect the stability of marriages,[13] commonly resulting in a higher risk of divorce compared to parents of children without disabilities.[14,15] In addition, within a family, the amount and frequency of interactions, the stability and accessibility of sibling relationships, shared experiences, and sibling roles provide ample opportunity for children to develop a range of social and emotional skills.[16,17]

Therefore, this study aimed to compare the social isolation of children and adolescents with ASD according to age, marital status, and number of siblings.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

An exploratory descriptive cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted on children and adolescents with ASD from municipal educational institutions in the central region of Chile (Talca, Rancagua, and Santiago).

Study participants and sampling

The sample selection was non-probabilistic by convenience. A total of 37 children and adolescents (32 boys and 5 girls) of both sexes were recruited. The age range ranged from 4 to 20 years. The average age of the parents was 36.85 ± 7.61 years, and the occupation of the father and/or guardian was 11 professionals with higher education, 7 with technical level, 15 housewives, and 4 working for hours.

The basis for considering children and adolescents with ASD was the presentation of the clinical history of each participant by the director of each of the schools.

For the evaluation of the social isolation variable, each parent was contacted by telephone to explain the objective of the study. Three of the researchers carried out this task for approximately 15 days.

Children enrolled in municipal special education schools with an age range of 4–20 years and those living with one or both parents were included. Children who studied in private schools, whose parents did not complete the applied scale, and those who did not authorize the application of the social isolation scale (two children) were excluded.

Data collection tool and technique

Social isolation was evaluated using the survey technique, whose instrument was a Likert-type scale of six questions, with five alternatives (always, almost always, sometimes, very little, and not at all). The sociodemographic variables of the children with ASD (age, sex, marital status of the parents, and number of siblings) were considered.

This instrument was proposed by Hawthorne,[18] with a Cronbach reliability of 0.81. It lasts approximately 5 min. It was applied to the parents of children with ASD through Google drive in May 2021.

The social isolation scale presented a Cronbach's alpha of r = 0.85 for this study. This indicates a high internal consistency for the sample studied.

Ethical consideration

The authors maintained all protocols before performing all procedures in this study with human participants in accordance with the ethical standards of the UCM research committee -208/2022 and the Declaration of Helsinki for Human Subjects.

Statistics

The normality of the data was verified by means of the Shapiro–Wilk test. Descriptive statistics of frequencies, percentages, ranges, averages (X), and standard deviation (SD) were analyzed. Differences between the two groups were determined by Student's t-test for independent samples. The effect size of the difference between the two groups was also determined using Cohen's d test. The effect size was considered small (Cohen's d = 0.2), medium (Cohen's d = 0.5), or large (Cohen's d = 0.8). Three-group comparisons were performed using ANOVA and Tukey's test of specificity. The relationship between social isolation scores and age was determined using Spearman's coefficient. In all cases, P < 0.05 was adopted. The results were processed and analyzed initially in excel spreadsheets and then in SPSS 18.0.

Results

The characteristics of the sample studied are shown in Table 1. It was organized according to age in two age groups (group 1: 4–10 years of age and group 2: 11–20 years of age), by marital status of the parents (married, divorced, and cohabiting), and by the number of siblings (none, one, two, and three).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample studied

| Variables | fi | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age groups | ||

| 4–10 years old | 24 | 64.9 |

| 11–20 years old | 13 | 35.1 |

| Total | 37 | 100 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 15 | 40.5 |

| Divorced | 3 | 8.1 |

| Cohabitant | 19 | 51.4 |

| Total | 37 | 100 |

| Number of siblings | ||

| None | 7 | 18.9 |

| One | 15 | 40.5 |

| Two | 11 | 29.7 |

| Three | 4 | 10.8 |

| Total | 37 | 100 |

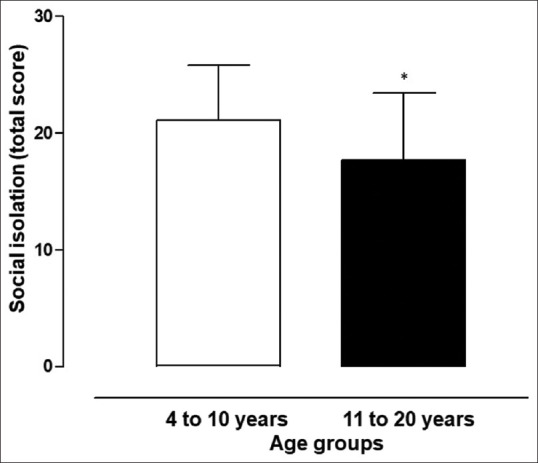

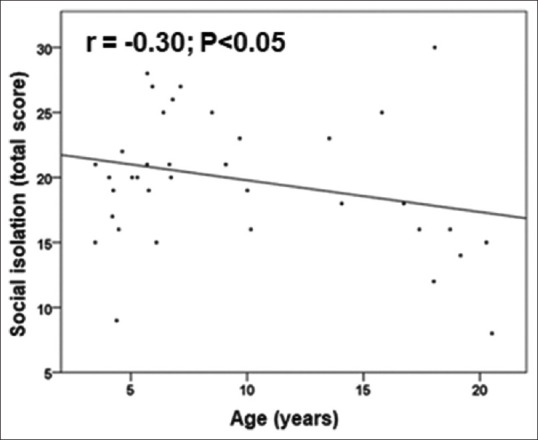

Comparisons between both age groups (children and adolescents with ASD) can be seen in Figure 1. Children showed higher values of social isolation (21.1 ± 4.7 points) in relation to adolescents (17.7 ± 5.7 points). These values are significant (P < 0.05), and the effect size was medium (0.65). This reflects that adolescents presented greater social isolation than their counterparts in the children's group. Furthermore, when age was related to the scores obtained in the social isolation scale [Figure 2], a negative association between both variables was determined (r = −0.30, P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Comparison of mean values of social isolation according to age groups in children and adolescents with ASD (*: difference in relation to 4–10 years)

Figure 2.

Relationship between age and number of siblings of children and adolescents with ASD

Comparisons of the values obtained in the social isolation scale according to marital status and number of siblings are shown in Table 2. Youngsters whose parents are divorced presented lower values in relation to their married and cohabiting counterparts (P < 0.05), and with a medium effect size of 0.59 and 0.70, respectively. However, there were no differences between children with married and cohabiting parents (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Social asylum of children and adolescents with ASD according to parental marital status and number of siblings

| Variables | n | X | SD | Average of the differences | CI 95% | Comparison between groups | Effect size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Ll | Ul | |||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Divorced | 3 | 16 | 3.6 | -- | -- | -- | Divorced vs married | −0.59 |

| Married | 15 | 22 | 4.5a | 6.0 | 0.02 | 11.98 | divorced vs cohabitant | −0.70 |

| Cohabitant | 19 | 23 | 3.3a | −6.6 | −12.5 | −0.73 | married vs cohanitant | −0,13 |

| Number of siblings | ||||||||

| None | 7 | 17 | 3.1 | -- | -- | -- | none vs one | −0.60 |

| One | 15 | 22 | 3.5* | −5.0 | −9.07 | −0.93 | none vs two | −0,62 |

| Two | 11 | 22 | 3.1* | −4.9 | −9.20 | −0.60 | none vs three | −0.62 |

| Three | 4 | 22 | 3.2* | −5.2 | −10.8 | 0.37 | ||

Legend: X: mean, SD: standard deviation, Li: lower limit, Ls: Upper limit, a: significant difference in relation to the divorced category; *: significant difference in relation to the no sibling category

However, when compared by the number of siblings, children with ASD who had no siblings presented lower mean values compared to the other categories who had one or more siblings (P < 0.05), with an effect size varying between 0.60 and 0.62.

Discussion

The results of the study have shown that children and adolescents living with divorced parents and those without siblings have shown a higher degree of social isolation in relation to their peers living with married or cohabiting parents and having one or more siblings in the family. In addition, children (4–10 years old) showed higher values than adolescents (11–20 years old). A negative correlation was even observed between age and social isolation, which can be interpreted to mean that at older ages there is a higher degree of social isolation among young people studied with ASD.

These results confirm that in children and adolescents with ASD, family, friends, and caregivers play an important role in support throughout life,[12] especially in functional families and with the presence of siblings, as demonstrated in this study. In fact, in the presence of dysfunctional families, as in the case of divorced parents, the upbringing of children may be conditioned to the rigidity of changes and adaptation to new family conditions. Especially when parents are forced to restructure their life project.

Sometimes, they have to deal with the feeling of having failed,[19] and conflicts between parents have negative effects on the children, producing difficulties at school, behavioral problems, negative self-concept, social problems with their peers, and difficulties in dealing with their parents.[20]

However, in relation to the number of siblings, the results have shown that having a sibling is relevant to improve social isolation. These findings are relevant, as they are consistent with the literature, since children with ASD who have siblings showed less severe social interaction deficits and better social adaptation skills than single children.[21,22]

In that sense, the findings emphasize the importance of sibling interactions as an opportunity for children with ASD to practice pro-social behaviors as noted by Rum et al.[23] Another recently conducted study indicates that the benefit of having older siblings on the social functioning of children with ASD could be explained by factors having to do, for example, with parents (more experienced parenting, less parental stress) and with the presence of typically developing older siblings (they function as a role model for the younger sibling with ASD).[22]

Regarding social isolation in children (4–10 years of age), compared with the group aged 11–20 years, the results indicate that children under 10 years of age presented a lower degree of social isolation than their older counterparts. This reflects the fact that adolescents and young adults presented a higher degree of social isolation.

Evidently, previous studies have reported that young people with ASD have less desire for social interaction, or a stronger desire to be alone[23] relative to children.[24] Thus, the evidence obtained in this study in the group of children (4–10 years old) indicates that they may be less likely to develop feelings of loneliness and social isolation at older ages.

In this context, the greater degree of social isolation observed in older youth could be detrimental to interpersonal relationships during adulthood, as physical health, psychosocial well-being, including quality of life, employment, and functional independence may be compromised.[8,25,26]

To our knowledge, no study of this nature has been identified in children and adolescents with ASD in Chile, so there is still an urgent need to explore and characterize in-depth social isolation in this type of population. This study can serve as a baseline for comparison with future research, given that data were collected during the pandemic times. Furthermore, it is recommended that future interventions be implemented before the transition from elementary to high school so that children are better equipped to face the social challenges of adolescence.[24]

Limitation and recommendation

Some limitations should be acknowledged in this study; for example, the type of sample selection (non-probabilistic) and the size is small, which limits generalization to other contexts. In addition, the cross-sectional descriptive study design does not allow us to determine causal relationships; therefore, future studies should carry out longitudinal studies, with which it is possible to verify changes in social isolation and explain causal relationships.

Conclusion

Based on the results obtained, this study concludes that children who live with divorced parents and have no siblings present a higher degree of isolation than their counterparts who live with both parents and have at least one sibling. In addition, age could play a relevant role, since children under 10 years of age presented a lower degree of isolation than the group of older adolescents aged 11–20 years. The results suggest that the preservation of a functional family and the presence of siblings could contribute to improving the sequelae of social isolation.

Financial support and sponsorship

This article is a work supported by the internal fund “UCM-IN-22218.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th. Washington, DC: APA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Confederación autismo España (CAE). Bienestar emocional en el trastorno del espectro del autista: Infancia y adolescencia. España. 2019. Available from: 20 October 2022. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

- 3.Alshaigi K, Albraheem R, Alsaleem K, Zakaria M, Jobeir A, Aldhalaan H. Stigmatization among parents of autism spectrum disorder children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2020;7:140–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpam.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lincoln AJ, Courchesne E, Kilman BA, Elmasian R, Allen M. A study of intellectual abilities in high-functioning people with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 1988;18:505–24. doi: 10.1007/BF02211870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szatmari P, Bartolucci G, Bremner R, Bond S, Rich S. A follow-up study of high-functioning autistic children. J Autism Dev Disord. 1989;19:213–25. doi: 10.1007/BF02211842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray DE. Coping over time: The parents of children with autism. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2006;50:970–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baxter AJ, Brugha TS, Erskine HE, Scheurer RW, Vos T, Scott JG. The epidemiology and global burden of autism spectrum disorders. Psychol Med. 2015;45:601–13. doi: 10.1017/S003329171400172X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGhee Hassrick E, Sosnowy C, Graham Holmes L, Walton J, Shattuck PT. Social capital and autism in young adulthood: Applying social network methods to measure the social capital of autistic young adults. Autism Adulthood. 2020;2:243–54. doi: 10.1089/aut.2019.0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine (IM) Division of Health Promotion and Disease Prevention; Berg RL, Cassells JS, editors. The Second Fifty Years: Promoting Health and Preventing Disability. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1992. p. 14. Social Isolation among Older Individuals: The Relationship to Mortality and Morbidity. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235604/ Available from: 15 October 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zavaleta D, Samuel K, Mills C. Social Isolation: A Conceptual and Measurement Proposal. Working Paper: 67. Oxford: Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Lloyd-Evans B, Giacco D, Forsyth R, Nebo C, Mann F, et al. Social isolation in mental health: A conceptual and methodological review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52:1451–61. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1446-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tint A, Weiss JA. Family wellbeing of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. Autism. 2016;20:262–75. doi: 10.1177/1362361315580442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seltzer MM, Krauss MW, Orsmond GI, Vestal C. Families of adolescents and adults with autism: Uncharted territory. In: Glidden LM, editor. International Review of Research on Mental Retardation. Vol. 23. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 267–94. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witt WP, Riley AW, Coiro MJ. Childhood functional status, family stressors, and psychological adjustment among school-aged children with disabilities in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:687–95. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.7.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wymbs BT, Pelham WE, Jr, Molina BSG, Gnagy EM, Wilson TK, Greenhouse JB. Rate and predictors of divorce among parents of youths with ADHD. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:735–44. doi: 10.1037/a0012719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cicirelli VG. Sibling influence throughout the lifespan. In: Lamb ME, Sutton-Smith, editors. Sibling Relationships: Their Nature and Significance Across the Lifespan. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1982. pp. 267–84. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buist KL, Deković M, Prinzie P. Sibling relationship quality and psychopathology of children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawthorne G. Measuring Social Isolation in older adults: Development and initial validation of the friendship scale. Soc Indic Res. 2006;77:521–48. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon FB, Stierlin H, Wynne LC. Vocabulario de Terapia Familiar. Gedisa Editors, Buenos Aires. 1997:365. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haimi M, Lerner A. The impact of parental separation and divorce on the health status of children, and the ways to improve it. J Clin Med Genom. 2016;4:137. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brody GH. Siblings’ direct and indirect contributions to child development. Current Dir Psychol Sci. 2004;13:124–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ben-Itzchak E, Nachshon N, Zachor DA. Having siblings is associated with better social functioning in autism spectrum disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2018;47:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10802-018-0473-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rum Y, Zachor DA, Dromi E. Prosocial behaviors of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) during interactions with their typically developing siblings. Int J Behav Dev. 2021;45:293–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deckers A, Muris P, Roelofs J. Being on your own or feeling lonely.Loneliness and other social variables in youths with autism spectrum disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2017;48:828–39. doi: 10.1007/s10578-016-0707-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nangle DW, Erdley CA, Newman JE, Mason CA, Carpenter EM. Popularity, friendship quantity, and friendship quality: Interactive influences on children's loneliness and depression. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32:546–55. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Syu Y-C, Lin L-Y. Sensory overresponsivity, loneliness, and anxiety in Taiwanese adults with autism spectrum disorder. Occup Ther Int. 2018;2:9165978. doi: 10.1155/2018/9165978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]