Abstract

The Streptomyces strains CHR3 and CHR28, isolated from the Baltimore Inner Harbor, contained two and one, respectively, giant linear plasmids which carry terminally bound proteins. The plasmids pRJ3L (322 kb), from CHR3, and pRJ28 (330 kb), from CHR28, carry genes homologous to the previously characterized chromosomal Streptomyces lividans 66 operon encoding resistance against mercuric compounds. Both plasmids are transmissible (without any detectable rearrangement) to the chloramphenicol-resistant S. lividans TK24 strain lacking plasmids and carrying a chromosomal deletion of the mer operon. S. lividans TK24 conjugants harboring pRJ3L or pRJ28 exhibited profiles of mercury resistance to mercuric compounds similar to those of Streptomyces strains CHR3 and CHR28.

Streptomycetes are gram-positive bacteria with a high G+C content (70 to 74%) (6) which grow as substrate hyphae and form, upon depletion of nutrients, aerial mycelia and spores. Members of the genus Streptomyces produce an extensive range of secondary metabolites of industrial importance, including enzymes and approximately 60% of all naturally occurring antibiotics (2). Streptomyces species are generally isolated from terrestrial habitats. In addition to other representatives of actinomycetales, their ubiquitous presence in marine and estuarine sediments is now well documented (16, 37), not only as dormant spores but also as metabolically active substrate mycelia (28).

Estuarine sediments are frequently severely polluted by heavy metals, including mercury compounds. From sediments next to a site of an abandoned ore-processing plant in the Baltimore Inner Harbor, two mercury-resistant Streptomyces strains, CHR3 and CHR28, were isolated. Chemotaxonomical studies and classification of 16S rRNA genes revealed that CHR3 and CHR28 are Streptomyces strains which form a cluster and are closely related to S. pseudogriseolus (32). Additional analyses showed that both strains were resistant to HgCl2 and the organomercuric compound phenylmercuric acetate. In S. lividans 66, this resistance is mediated by six open reading frames (ORFs) arranged in two divergently transcribed operons. The regulatory and transport genes form one operon, and the second one is composed of the genes for the mercuric reductase (merA) and for the organolyase (merB) (36). The combination of both merA and merB confers a broad-spectrum mercury resistance to the isolate, as opposed to a narrow-spectrum resistance conferred by merA alone (36).

The mechanism of mercury resistance of S. lividans 66 thus resembles those described for several other gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, including Escherichia coli (12), Bacillus subtilis (38), and Staphylococcus aureus (24). Hybridization studies indicated that both marine Streptomyces strains, CHR3 and CHR28, carry DNA stretches which are linked and appeared homologous to the two S. lividans operons required for broad-spectrum mercury resistance (32).

Mercury resistance genes have been encountered on transposons and/or circular plasmids within various bacteria. Among streptomycetes, in addition to a wide range of circular plasmids, the discovery of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (35) has facilitated the molecular examination of giant linear plasmids. The presence of linear plasmids in Streptomyces spp. was first described by Hayakawa et al. (13), and work by Kinashi et al. (20, 21) has demonstrated the presence of large linear plasmids (>100 kb) in several antibiotic-producing Streptomyces spp. Linear plasmids ranging in size from 12 kb to 1 Mb have now been reported in more than 10 Streptomyces spp. (7, 11, 14, 41, 45), and they have also been found in other actinomycete genera such as Nocardia, Rhodococcus, and Mycobacterium (8, 17, 18, 31). Large linear plasmids have been shown to carry genes encoding antibiotic biosynthesis, resistance to heavy metal, and ability to break down xenobiotics (for a review, see reference 26).

We report here that the mercury resistance genes of Streptomyces strains CHR3 and CHR28 are present on transmissible giant linear plasmids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

Streptomyces strains CHR3 and CHR28 were isolated from a heavily polluted site in the Baltimore Inner Harbor and have been described previously (32). S. lividans TK24 and S. lividans 66 were gifts from D. A. Hopwood, Norwich, United Kingdom. The strains are described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Phenotypea | Linear plasmids | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces sp. CHR3 | Hgr Clms | pRJ3H, pRJ3L | 32 |

| Streptomyces sp. CHR28 | Hgr Clms | pRJ28 | 32 |

| S. lividans CHR3T | Hgr Clmr | pRJ3L | This study |

| S. lividans CHR28T | Hgr Clmr | pRJ28 | This study |

| S. lividans TK24 | Hgs Clmr | 15 | |

| S. lividans 66 | Hgr Clms | SLP2 | 15 |

Hg, mercury; Clm, chloramphenicol.

PFGE.

DNA plugs for PFGE analysis were prepared by a modification of the procedure used by Kieser et al. (19). Mycelia were embedded in 0.75% InCert Agarose (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine) and treated with lysozyme for 2 h at 37°C, followed by 48 h at 55°C in a 1-mg/ml concentration of proteinase K in NDS solution (0.5 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9.0], 1% Sarkosyl). In cases where plugs were to be digested with restriction enzymes, proteinase K activity was inhibited by treating the plugs with 1.5 mM Pefabloc SC (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.), a nontoxic serine-proteinase inhibitor, for 90 min in TE buffer (pH 7.6) at 37°C (1). Plugs were rinsed with T20E50 (20 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM EDTA; pH 8.0) three times for 1 h at 4°C.

Plugs were subjected to PFGE by using a clamped homogenous electric field system (CHEF DR-III; Bio-Rad, Melville, N.Y.) in 0.5× TBE buffer (1× TBE is 98 mM Tris-HCl, 89 mM boric acid, and 62 mM EDTA) containing 100 μM of thiourea at 14°C (33). Ramping times are indicated in legends of Fig. 1, 2, and 4. Pulse times of 30 and 90 s were used to determine whether plasmids were linear or circular. Ladders of λ DNA concatamers and Saccharomyces cerevisiae YNN 295 chromosomes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) were used as molecular-weight standards.

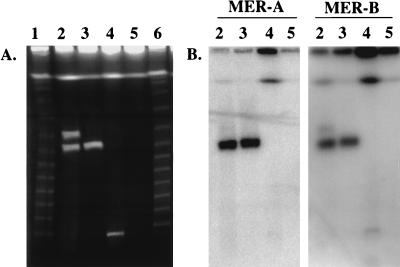

FIG. 1.

(A) PFGE and (B) Southern hybridization with probe MER-A and MER-B analysis of Streptomyces strains CHR3 and CHR28. Lanes 1 and 6, λ concatamer ladder; lane 2, strain CHR3; lane 2, strain CHR28; lane 3, S. lividans 66; lane 4, S. lividans TK24. Pulse time was 30 s for 24 h (6 V/cm at 14°C).

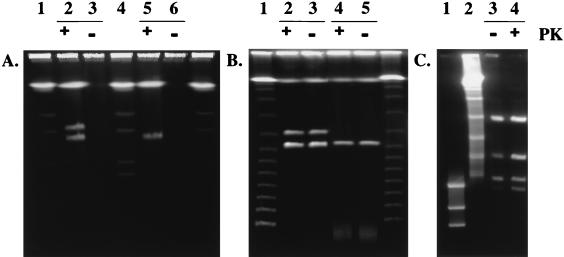

FIG. 2.

(A) PFGE of DNA plugs of strains CHR3 and CHR28. Lanes 1 and 4, S. cerevisiae chromosomes; lane 2, CHR3 with proteinase K treatment; lane 3, CHR3 without proteinase K treatment; lane 5, CHR28 with proteinase K treatment; lane 6, CHR3 without proteinase K treatment. Pulse time was 30 s. (B) SDS-PFGE of strains CHR3 and CHR28. Lane 1, λ concatamer ladder; lane 2, CHR3 with proteinase K treatment; lane 3, CHR3 without proteinase K treatment; lane 4, CHR28 with proteinase K treatment; lane 5, CHR28 without proteinase K treatment. Pulse time was 30 s for 24 h (6 V / cm at 14°C). (C) Retardation gel assay. Plasmid bands from samples treated (+) or untreated (−) with proteinase K were excised from an SDS-PFGE gel and digested with restriction enzyme XbaI. Lane 1, λ DNA digested with HindIII; lane 2, λ concatamer ladder; lane 3, pRJ28 from sample prepared without proteinase K treatment digested with XbaI; lane 4, pRJ28 from sample prepared with proteinase K treatment digested with XbaI. Ramping time was 12 to 15 s for 20 h (6 V/cm at 14°C).

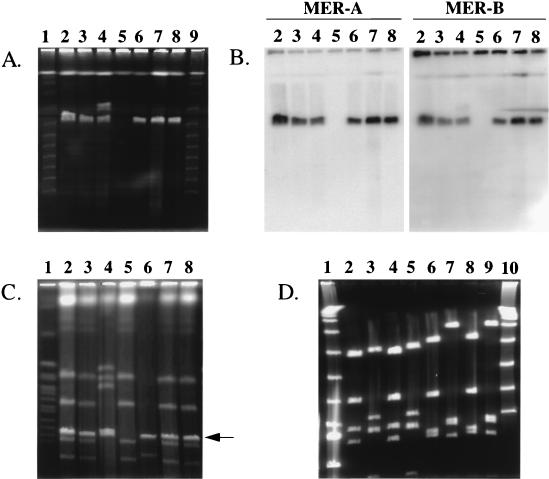

FIG. 4.

Analysis of conjugants. (A) PFGE and (B) Southern hybridization with probe MER-A and MER-B of parents and conjugants of strains CHR3 and CHR28. Lanes 1 and 9, λ concatamer ladder; lanes 2 and 3, conjugants of strain CHR3; lane 4, parent strain CHR3; lane 5, recipient strain S. lividans TK24; lane 6, parent strain CHR28; lanes 7 and 8, conjugants of strain CHR28. Pulse time was 30 s for 24 h (6 V / cm at 14°C). (C) PFGE analysis of total DNA digested with restriction enzyme DraI. Lane 1, Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosomes; lane 2 and 3: conjugants of strain CHR3; lane 4, parent strain CHR3; lane 5, recipient strain S. lividans TK24; lane 6, parent strain CHR28; lanes 7 and 8, conjugants of strain CHR28. The arrow indicates the linear uncut plasmid. Pulse time ramping was 60 to 180 s for 26 h (6 V / cm at 14°C). (D) Restriction digest of plasmids from parents and conjugants. Lanes 1 and 10, λ concatamer ladder; lane 2, pRJ28T digested with XbaI; lane 3, pRJ28T digested with HindIII; lane 4, pRJ28 digested with XbaI; lane 5, pRJ28 digested with HindIII; lane 6, pRJ3LT digested with XbaI; lane 7, pRJ3LT digested with HindIII; lane 8, pRJ3L digested with XbaI; lane 9, pRJ3L digested with HindIII. Ramping time was 8 to 14 s for 20 h (6 V/cm at 14°C).

DNA was stained with SYBR Green I (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, Oreg.) prior to photography with 302-nm UV light illumination by using an SYBR Green gel stain photographic filter (Molecular Probes). The gels were digitized with a FluorImager 573 (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.), and molecular weights were estimated with FragmentNT analysis software (Molecular Dynamics).

SDS-PFGE conditions.

Plugs were prepared without the proteinase K treatment and loaded onto a 1% (wt/vol) Seakem GTG (FMC) agarose gel with a 1× TBE buffer containing 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) as described by Kinashi and Shimaji-Murayama (22). The gel was run in 0.5× TBE buffer containing 0.2% SDS.

Plasmid restriction mapping.

Plasmid bands or restriction fragments were excised from the gel and incubated in T20E50 buffer for 12 h. Agarose plugs were rinsed in the appropriate restriction buffer for 6 to 12 h at 4°C, transferred to 300 μl of ice-cold buffer containing 50 U of restriction enzyme and 50 mg of acetylated bovine serum albumin (Promega Co., Madison, Wis.), and kept at 4°C for 2 h prior to incubation for 12 to 16 h at 37°C. Double restriction digests were performed under the same conditions, with 50 U of each restriction enzyme. Enzymes and buffers were purchased from Promega and used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

DNA labeling and Southern hybridization.

An 816-bp PvuII fragment (MER-A) of the S. lividans 66 mercuric reductase gene merA and a 716-bp SalI-EcoRV fragment (MER-B) of the organolyase gene merB were prepared from plasmid pJOE851.2 (36), generously provided by J. Altenbuchner, Stuttgart, Germany. Probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by using a random priming kit from Pharmacia Biotech, Inc. (Piscataway, N.J.). PFGE gels were UV irradiated for 90 s with a 254-nm light source and then transferred to a Magnagraph membrane filter (Micron Separations, Inc., Westborough, Mass.) by alkaline capillary transfer (4). Membranes were hybridized at 65°C and washed at high stringency (68°C) in 0.1× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Plasmid transfer.

Spores (2 × 106) of S. lividans TK24 were mixed with 107 spores of CHR3 or CHR28 and plated onto YME medium (ISP2) (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). Crosses were incubated at 26°C for 7 days until sporulation occurred. Spores were harvested according to the method of Hopwood et al. (15) and plated onto YME medium containing mercuric chloride (0.05 mM) and chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml). The transfer frequencies were expressed as transconjugants per donor genome. From each cross, five individual colonies were screened for the presence of linear plasmids by using PFGE as described above.

Determination of mercury resistance by agar diffusion assay.

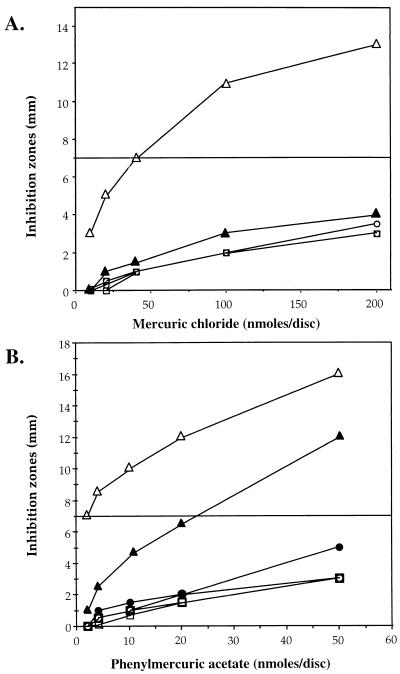

The sensitivity of the strains was tested by agar diffusion assay (40). Disks (6 mm in diameter) were saturated with HgCl2 or phenylmercuric acetate solutions as follows: 2, 10, 20, 40, 100, and 200 nmol or 0.5, 2, 4, 10, 20, and 50 nmol, respectively. Disks were placed on the surface of the agar plates previously inoculated with 108 spores of the strain to be tested. The zone of inhibition was measured after incubation at 26°C for 3 days. Sensitive strains had zones of inhibition of ≥10 mm and resistant strains had zones of inhibition of <7 mm with 100 nmol of HgCl2 or 20 nmol of PMA. The growth of all strains was compared to that of the control laboratory strains S. lividans TK24 (mercury sensitive) and S. lividans 66 (mercury resistant).

RESULTS

Identification and characterization of giant linear plasmids.

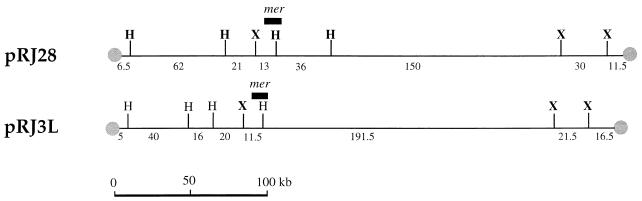

Two plasmids, designated pRJ3H (370 kb) and pRJ3L (322 kb) were detected in the Streptomyces strain CHR3 and a 330-kb plasmid, pRJ28, was found in the Streptomyces strain CHR28 (Fig. 1A). The relative migrations of plasmids pRJ3H, pRJ3L, and pRJ28, determined by using two different pulse times, were found to correspond to linear concatamers of lambda DNA under both running conditions, indicating that all three plasmids are linear and not circular. The linear plasmids migrated into the gel only when the DNA-containing plugs had been treated with proteinase K (Fig. 2A). It was therefore concluded that proteins were bound to the plasmids. When SDS (0.2%) was added to the running buffer, the chromosomal and plasmid DNAs migrated into the gel, independent of whether or not pretreatment with proteinase K had occurred (Fig. 2B). This finding is in agreement with previous data (22) showing that SDS leads to unfolding of the protein. To localize the protein binding site, each of the linear plasmids, derived from plugs treated or not treated with proteinase K and after separation on SDS-containing PFGE gels, was analyzed by restriction with the enzyme XbaI; the results are shown for pRJ28 (Fig. 2C). In the absence of protein, two fragments (89.5 and 11.5 kb) were partially retained in the gel well, shown by the reduced intensity (confirmed by densitometry) of the lowest and second highest bands in lane 3 compared to lane 4 (Fig. 2C). Similarly, fragments of 91 and 16.5 kb were retained for pRJ3L (results not shown). These data suggested that the corresponding fragments are bound to protein. Restriction maps were established by using enzymes XbaI and HindIII, both individually and in combination (Fig. 3). Restriction fragments were accurately sized by conventional agarose gel electrophoresis, since DNA fragment migration in PFGE is dependent on G+C content and cannot be used to size small (20- to 50-kb) fragments accurately.

FIG. 3.

Restriction map of pRJ3L and pRJ28. X, XbaI; H, HindIII. The relative locations of the mercuric resistance genes are indicated by the solid black bar. The terminal proteins are indicated by a gray circle.

Mercury resistance genes are encoded by linear plasmids.

The strains CHR3 and CHR28 had previously been found to be resistant to mercury compounds (32). Hybridizations had shown that both strains carry mercury resistance genes homologous to those in the wild-type strain S. lividans 66 (32). In the present study, hybridization with probe MER-A from the merA gene, MER-B from merB gene, and MER-RTP from genes merR, merT, and merP and from ORF IV demonstrated that the mer genes are located on the large linear plasmids pRJ3L and pRJ28 in strains CHR3 and CHR28, respectively (Fig. 1B) but not on the corresponding chromosomal DNAs. The mer genes were located on a 13-kb HindIII-XbaI and a 36-kb HindIII fragment of the plasmid pRJ28 and on HindIII-XbaI fragments of 11.5 and 191.5 kb of pRJ3L (Fig. 3).

Conjugation experiments.

To identify a suitable recipient, S. lividans strains were tested for their sensitivity to mercuric compounds. S. lividans TK24 was, contrary to its progenitor wild-type strain S. lividans 66 (36), found to be sensitive. Hybridizations confirmed that S. lividans 66 carries the six ORFs required for mercury resistance that are deleted in TK24 (15). Additionally, former findings that TK24 lacks circular and linear plasmids were substantiated. Comparative analyses of resistance patterns to antibiotics showed that TK24 is, like S. lividans 66, resistant to chloramphenicol (9). Thus, TK24 was selected to serve as a possible recipient during conjugation with the expected donors CHR3 and CHR28. After corresponding matings, the harvested spores were inspected for outgrowth into colonies resistant to mercuric chloride and chloramphenicol. The appearance of all chloramphenicol- and mercuric chloride-resistant colonies was similar to that of TK24 colonies; they had developed gray spores. In contrast, CHR3 and CHR28 had light-brown and green spores, respectively. Transfer frequencies of 1.5 × 10−2 and 1.9 × 10−3 transconjugants per donor genome were calculated for pRJ3L and pRJ28, respectively. For further characterization, the DNA of two of the randomly selected conjugants from the two crosses was analyzed in more detail. One group of conjugants contained the plasmid pRJ3L, the size and restriction pattern of which were identical to those of pRJ3L isolated from CHR3 (Fig. 4A and 4C). None of them contained the plasmid pRJ3H present in CHR3. Representatives of the second cross harbored the plasmid pRJ28, which corresponded in size and the distribution of restriction enzyme sites to the one initially identified in CHR28 (Fig. 4A and C). merA and merB genes were present on plasmids in conjugants (Fig. 4B). In order to assess whether the conjugants are TK24 strains, their unsheared total DNAs were cleaved with restriction enzyme AseI, and the PFGE-separated fragments were compared to those of TK24, CHR3, and CHR28 (Fig. 4D). The DNA of the inspected transconjugants displayed many breaks when thiourea had not been added to the buffer in the course of PFGE analysis. This is a typical characteristic of DNA from S. lividans 66 and its derivatives but not of DNA from CHR3 and CHR28. The data clearly showed that all the conjugants contain, in addition to the transferred linear plasmid, the TK24 genome. Plasmids from conjugants were designated pRJ3LT and pRJ28T.

Mercury profiles of transconjugants were found to be similar, by agar diffusion disc assay, to those of previously reported (32) parent strains CHR3 and CHR28 (Fig. 5). Taken together, the data clearly demonstrate that the transferred plasmids confer resistance to inorganic and organic mercuric compounds.

FIG. 5.

Mercury resistance profiles to mercuric chloride (A) and phenylmercuric acetate (B). Streptomyces strains CHR3 (•) and CHR28 (■) and conjugants CHR3T (○) and CHR28T (□) are as marked. The control strains were S. lividans 66 (▴) and S. lividans TK24 (▵). The horizontal line indicates the inhibition zone diameter used as a resistance criterion.

DISCUSSION

Previously, two Streptomyces strains, CHR3 and CHR28, were found to be resistant to HgCl2 and organic mercuric compounds (35). The strain CHR28 was found to harbor one large linear plasmid pRJ28 (330 kb). Streptomyces strain CHR3 carries two plasmids, pRJ3H and pRJ3L, of 390 and 322 kb, respectively. pRJ28 and pRJ3L appeared to be closely related as they showed homologous regions in cross-hybridization experiments. However, pRJ3L and pRJ3H shared no region of homology, indicating that they did not derive from each other. In the absence of mercury, plasmids were not lost. The plasmids were not found to integrate into the chromosomal DNAs as it has been reported for other Streptomyces plasmids, such as pSAM2 (29), pSLP1 (3), and pSCP1 (23).

The linear plasmids pRJ3L and pRJ28 were transferable to the chloramphenicol-resistant (9), mercury-sensitive S. lividans strain TK24 during conjugation. Physiological and hybridization studies clearly showed that the corresponding TK24 conjugants carry the mercuric resistance pattern of CHR3 and CHR28 and also contain the mercury resistance genes on their acquired plasmids.

Within various gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, mercury resistance genes have frequently been found on plasmids and/or transposable elements (42). Among actinomycetes, the synthesis of a mercuric reductase was associated with the presence of the giant linear plasmid pBD2 in Rhodococcus erythropolis (8). The plasmid pBD2 additionally encodes genes required for the catabolism of isopropylbenzene and trichloroethylene. Although giant linear plasmids are frequently encountered in Streptomyces strains, most of their functions are still not known. Several linear plasmids have been linked with specific phenotypes, including restriction and modification systems (44), antibiotic production, heavy-metal resistance, and the ability to break down xenobiotics (for a review, see reference 26).

All linear plasmids from streptomycetes identified to date contain terminal inverted repeats with proteins linked to their 5′ ends, like some fungi and yeast linear plasmids (26) or some bacteriophage and adenovirus genomes (10, 25, 34). The replication mechanism of linear genomes has been well studied for the linear Bacillus phage Φ29 (5, 39) and the adenovirus (30). For these linear DNAs, the linked proteins have been shown to be required for the initiation of replication. The newly described linear plasmids from CHR3 and CHR28 also contain terminally bound proteins. The role of terminal proteins in linear chromosomes or plasmids of streptomycetes is still unknown, but it is speculated to protect the extremities from exonuclease activities and/or be part of the replication machinery, as described above for bacteriophage and adenovirus genomes.

Like some other giant linear plasmids, pRJ3L and pRJ28 are transmissible in the course of conjugation. Both transferred plasmids were shown to be structurally identical to those in the parent strains (Fig. 4C), indicating that no rearrangement occurred during conjugation. In addition, the conjugants were shown to have the same level of resistance to mercuric chloride or phenylmercuric acetate as the donor strains, indicating that the complete set of the mercury resistance genes was transmissible (Fig. 5).

So far, the transfer functions of linear Streptomyces plasmids have scarcely been investigated. Transfer functions were found located on pBL1, a 43-kb linear plasmid derivative of giant linear plasmid pBS1 from Streptomyces bambergiensis (43). By insertion and deletion mutagenesis, five genes were identified that are required for efficient transfer and its regulation (43).

The finding that mercury resistance genes are encoded on transmissible linear plasmids in marine streptomycetes has important ecological implications. Horizontal gene transfer might occur in the sediment microbial population, at least among the Streptomyces assemblage. Although no intergeneric transfer of large plasmids has been demonstrated to date, it can be envisaged between Streptomyces, Rhodococcus, or other actinomycetes where large linear plasmids have already been found (8, 17, 27, 31). Thus, it is important to learn more about the genes involved in the mobilization of linear plasmids and to elucidate the implications of the spread of genes within natural habitats of actinomycetes. Little is known about the evolutionary origin or ecological function of giant linear plasmids in actinomycetes, but these plasmids may play an important role in the spread of genes in the natural environment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Schering-Plough Research Institute.

We thank Ann Horan for helpful discussions and Frank Robb for advice and encouragement.

Footnotes

Contribution no. 302 from the Center of Marine Biotechnology. Contribution no. 907 from the Australian Institute of Marine Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benjamin M M, Datta A R. Modified pulsed field gel electrophoresis technique using Pefabloc® SC for analyzing Listeria monocytogenes DNA. Biochemica. 1995;2:30–31. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berdy J. Recent advances in and prospects of antibiotic research. Process Biochem. 1988;15:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bibb M, Ward J M, Kieser T, Cohen S N, Hopwood D A. Excision of chromosomal DNA sequences from Streptomyces coelicolor forms a novel family of plasmids detectable in Streptomyces lividans. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;18:230–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00272910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birren B, Lai E. Pulsed field gel electrophoresis: a practical guide. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco L, Salas M. Replication of phage Φ29 DNA with purified terminal protein and DNA polymerase: synthesis of full-length Φ29 DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:6404–6408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.19.6404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chater K F, Hopwood D A. Streptomyces genetics. In: Goodfellow M, Mordanski M, Williams S T, editors. The biology of actinomycetes. London, England: Academic Press, Inc.; 1984. pp. 229–286. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C W, Yu T-W, Lin Y-S, Kieser H M, Hopwood D A. The conjugative plasmid SLP2 of Streptomyces lividans is a 50 kb linear molecule. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:925–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dabrock B, Kesseler M, Averhoff B, Gottschalk G. Identification and characterization of a transmissible linear plasmid from Rhodococcus erythropolis BD2 that encodes isopropylbenzene and trichloroethene catabolism. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:853–860. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.3.853-860.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dittrich W, Betzler M, Schrempf H. An amplifiable and deletable chloramphenicol-resistance determinant of Streptomyces lividans 1326 encodes a putative transmembrane protein. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2789–2797. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grahn A M, Bamford J K, O’Neill M C, Bamford D H. Functional organization of the bacteriophage PRD1 genome. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3062–3068. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.3062-3068.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gravius B, Glocker D, Pigac J, Pandza K, Hranueli D, Cullum J. The 387 kb linear plasmid pPZG101 of Streptomyces rimosus and its interactions with the chromosome. Microbiology. 1994;140:2271–2277. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-9-2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamlett N V, Landale E C, Davis B H, Summers A O. Roles of the Tn21 merT, merP, and merC gene products in mercury resistance and mercury binding. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6377–6385. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6377-6385.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayakawa T, Tanaka T, Sakaguchi K, Otake N, Yonehara H. A linear plasmid-like DNA in Streptomyces sp. producing lankacidin group antibiotics. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1979;25:255–260. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirochika H, Nakamura K, Sakaguchi K. A linear DNA plasmid from Streptomyces rochei with an inverted terminal repetition of 614 base pairs. EMBO J. 1984;3:761–766. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kieser T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C P, Ward J M, Schrempf H. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. Norwich, England: The John Innes Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen P R, Dwight R, Fenical W. Distribution of actinomycetes in near-shore tropical marine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1102–1108. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.4.1102-1108.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalkus J, Dörrie C, Fisher D, Reh M, Schegel H G. The giant plasmid pHG207 from Rhodococcus sp. encoding hydrogen autotrophy: characterization of the plasmid and its termini. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2055–2060. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-9-2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalkus J, Reh M, Schlegel H G. Hydrogen autotrophy of Nocardia opaca strains is encoded by linear megaplasmids. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:1145–1151. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-6-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kieser H M, Kieser T, Hopwood D A. A combined genetic and physical map of the Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5496–5507. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.17.5496-5507.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinashi H, Shimaji M. Detection of giant linear plasmids in antibiotic producing strains of Streptomyces by the OFAGE technique. J Antibiot. 1987;40:913–916. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinashi H, Shimaji M, Sakai A. Giant linear plasmids in Streptomyces which code for antibiotic biosynthesis genes. Nature. 1987;328:454–456. doi: 10.1038/328454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinashi H, Shimaji-Murayama M. Physical characterization of SCP1, a giant linear plasmid from Streptomyces coelicolor. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1523–1529. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.4.1523-1529.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinashi H, Shimaji-Murayama M, Hanafusa T. Integration of SCP1, a giant linear plasmid, into the Streptomyces coelicolor chromosome. Gene. 1992;115:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90537-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laddaga R A, Chu L, Misra T K, Silver S. Nucleotide sequence and expression of the mercurial-resistance operon from Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pI258. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5106–5110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin A C, Lopez R, Garcia P. Nucleotide sequence and transcription of the left early region of Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteriophage Cp-1 coding for the terminal protein and the DNA polymerase. Virology. 1995;211:21–32. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meinhardt F, Schaffrath R, Larsen M. Microbial linear plasmids. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;47:329–336. doi: 10.1007/s002530050936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meissner P S, Falkinham J O., III Plasmid-encoded mercuric reductase in Mycobacterium scrofulaceum. J Bacteriol. 1984;157:669–672. doi: 10.1128/jb.157.2.669-672.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moran M A, Rutherford L T, Hodson R E. Evidence for indigenous Streptomyces populations in a marine environment determined with a 16S rRNA probe. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3694–3700. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.10.3695-3700.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pernodet J L, Simonet J M, Guerineau M. Plasmids in different strains of Streptomyces ambofaciens: free and integrated form of plasmid pSAM2. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;198:35–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00328697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petterson U, Roberts R J. Adenovirus gene expression and replication: a historical review. Cancer Cells. 1991;4:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Picardeau M, Vincent V. Characterization of large linear plasmids in mycobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2753–2756. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2753-2756.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ravel J, Amoroso M J, Colwell R R, Hill R T. Mercury-resistant actinomycetes from the Chesapeake Bay. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;162:177–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ray T, Weaden J, Dyson P. Tris-dependent site-specific cleavage of Streptomyces lividans DNA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;96:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90412-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Savilahti H, Bamford D H. The complete nucleotide sequence of the left very early region of Escherichia coli bacteriophage PRD1 coding for the terminal protein and the DNA polymerase. Gene. 1987;57:121–130. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90183-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz D C, Cantor C R. Separation of yeast chromosome-sized DNAs by pulsed field gradient gel electrophoresis. Cell. 1984;37:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sedlmeier R, Altenbuchner J. Cloning and DNA sequence analysis of the mercury resistance genes of Streptomyces lividans. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;236:76–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00279645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takizawa M, Colwell R R, Hill R T. Isolation and diversity of actinomycetes in the Chesapeake Bay. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:997–1002. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.997-1002.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Moore M, Levinson H S, Silver S, Walsh C, Mahler I. Nucleotide sequence of a chromosomal mercury resistance determinant from a Bacillus sp. with broad-spectrum mercury resistance. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:83–92. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.83-92.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watabe K, Shin M, Ito J. Protein-primed initiation of phage phi 29 DNA replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:4248–4252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.14.4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiss A A, Murphy S D, Silver S. Mercury and organomercurial resistances determined by plasmids in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1977;132:197–208. doi: 10.1128/jb.132.1.197-208.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu X, Roy K L. Complete nucleotide sequence of a linear plasmid from Streptomyces clavuligerus and characterization of its RNA transcripts. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:37–52. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.37-52.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yureiva O, Kholodii G, Minakhin L, Gorlenko Z, Kalyaeva E, Mindlin S, Nikiforov V. Intercontinental spread of promiscuous mercury-resistance transposons in environmental bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:321–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3261688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zotchev S B, Schrempf H. The linear Streptomyces plasmid pBL1: analyses of transfer functions. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;242:374–382. doi: 10.1007/BF00281786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zotchev S B, Schrempf H, Hutchinson C R. Identification of a methyl-specific restriction system mediated by a conjugative element from Streptomyces bambergiensis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4809–4812. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4809-4812.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zotchev S B, Soldatova L I, Orekhov A V, Schrempf H. Characterization of a linear extrachromosomal DNA element pBL1 isolated after interspecific mating between Streptomyces bambergiensis and Streptomyces lividans. Res Microbiol. 1992;143:839–845. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90071-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]