Abstract

Biological nanoparticles, such as bacterial outer membrane vesicles (OMVs), are routinely characterized through transmission electron microscopy (TEM). In this study, we report a novel method to prepare OMVs for TEM imaging. To preserve vesicular shape and structure, we developed a dual fixation protocol involving osmium tetroxide incubation prior to negative staining with uranyl acetate. Combining osmium tetroxide with uranyl acetate resulted in preservation of sub-50 nm vesicles and improved morphological stability, enhancing characterization of lipid-based nanoparticles by TEM.

Keywords: bacteria, nanoparticles, outer membrane vesicles, uranyl acetate, osmium tetroxide, transmission electron microscopy

The rapid advancement of nanotechnology in recent decades has contributed to rising interest in the characterization and application of nanoparticles [1,2]. The study of biological nanoparticles has garnered interest due to their involvement in human physiology, homeostasis and pathology [3,4]. A subset of biological nanoparticles are extracellular vesicles (EVs) that are ubiquitous to both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells [5–9]. Gram-negative bacteria secrete EVs that have similar biomolecular components as their cell of origin [10–12]. Gram-negative bacteria, in particular, release outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) that can elicit potent immune responses in the host cells and are of significant interest in drug and vaccine development [12–15].

Accurate imaging of OMVs aids in the characterization of their physical properties (i.e. shape, lipid and protein profiles) and mechanisms of vesicle biogenesis and interactions [16–18]. These vesicles range widely in size from 20 to 200 nm in diameter and arise from the bacterial outer membrane [5]. The mechanisms of biogenesis are poorly understood with the current models including activation of stress-response pathways, reduced cross-linking of peptidoglycan to the outer membrane and accumulation of biomolecules in the periplasmic space [11,19,20]. While OMVs cannot be visualized in detail through conventional light microscopy techniques, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) enables high-resolution imaging of OMVs, most notably through negative staining [21,22].

Uranyl acetate (UA), a commonly utilized negative stain for TEM for >60 years [23,24], is an acetate salt of uranium oxide that binds to a wide range of biomolecules [25,26]. Although UA can stain lipids with sialic acid groups like glycoproteins and gangliosides [26], OMVs are composed primarily of lipopolysaccharides (LPSs), which lack the moieties necessary for interactions with the uranium oxide ions [27], leading to issues with imaging the OMVs post-UA staining such as poor contrast and image quality. Another problem that arises is that drying of the UA-stained vesicles can lead to modification of the vesicle form and structure, resulting in issues with downstream analysis of the OMVs [28,29]. Osmium tetroxide is another oft-used electron microscopy stain where the osmium ions integrate into the phospholipid membrane and rapidly oxidize to osmium dioxide, giving the cellular substructures greater electron density, allowing them to appear darker in the microscope’s electron beam [30]. This mechanism of action also allows the molecule to act as a fixative as it preserves the structure of cellular samples and membranes through its reaction with the unsaturated double bonds of adjacent lipids, enabling the formation of a stable polymerized ester structure in the sample that can resist physical and chemical adjustments [30–32]. Thus, we hypothesized that the reaction of osmium tetroxide with unsaturated lipids is a superior alternative for the negative staining of EVs.

To test this hypothesis, we examined the addition of osmium tetroxide treatment to OMVs in conjunction with UA staining to enhance the quality of TEM images. In this report, we compared the negative staining of OMVs from enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF) and non-toxic B. fragilis (NTBF) under two conditions: UA staining alone (Fig. 1) versus co-staining osmium tetroxide with UA (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

OMV staining with UA alone. TEM micrographs of ETBF (a and b) and NTBF OMVs (c and d) stained with UA. Arrows denote vesicles that appear collapsed or that experienced a loss of structure. Scale bars, 100 nm. ×50 000 magnification.

ETBF, enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis; NTBF, non-toxic Bacteroides fragilis; OMV, outer membrane vesicle; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; UA, uranyl acetate.

Fig. 2.

OMV staining with OsO4 and UA. TEM micrographs of ETBF (a and b) and NTBF (c and d) OMVs stained with osmium tetroxide and UA. Vesicles are expected to be spherical in shape. Scale bars, 100 nm. ×50 000 magnification.

ETBF, enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis; NTBF, non-toxic Bacteroides fragilis; OMV, outer membrane vesicle; TEM, transmission electron microscopy; UA, uranyl acetate.

Using only UA staining (Fig. 1), we observed collapsed vesicular forms (a and b) and the formation of irregularly shaped vesicles and lipid fragments (c and d), indicative of OMV degradation. Additionally, the low image contrast, combined with irregular vesicular morphologies, prevents accurate quantification of critical parameters. However, co-staining with UA and osmium tetroxide improves contrast and morphological characterization of vesicles (Fig. 2) as demonstrated by enumeration and by calculating the roundness of the vesicles observed (Fig. 3).

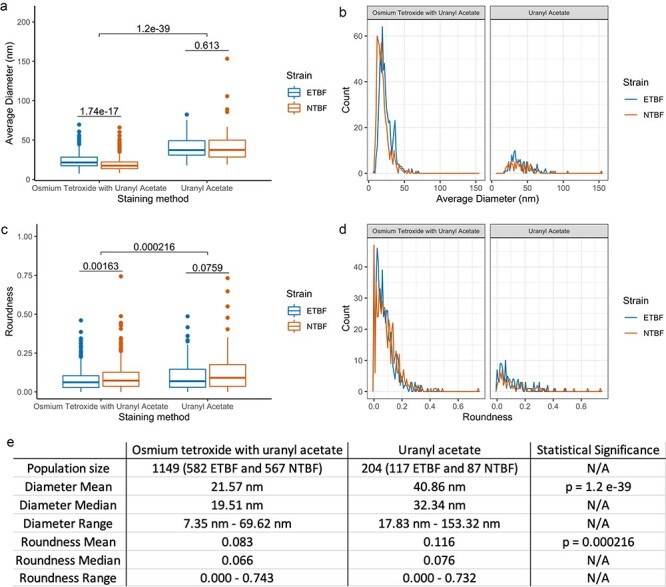

Fig. 3.

Quantitative analyses of OMV size (a and b) and roundness (c and d). Comparisons between different staining methods are shown as a box blot (a and c) and density plot (b and d). Osmium tetroxide and UA co-stain was able to visualize smaller vesicles and rounder vesicles in greater quantity. Statistics were calculated using Welch’s t-test.

OMV, outer membrane vesicle; UA, uranyl acetate.

Enumeration, size and morphology analyses of vesicles from obtained images show that the co-stain is able to reveal significantly smaller, more round vesicles compared to UA alone (Fig. 3e). With respect to the co-stain, the fixative properties of osmium on lipids allow it to stain vesicles to preserve the structure to a much greater degree than UA alone. We note that using cryo-EM would be advantageous in revealing accurate dimensions and shape and that using phosphotungstate, silicotungstate or ammonium molybdate could also improve negative staining.

In summary, the added contrast of UA in the co-stain facilitates visualization of smaller vesicles, enabling a greater enumeration of OMVs for representative quantification. The low contrast of UA alone, in combination with irregular vesicle structure, yields lower enumeration sample size and prevents accurate measurement of the OMVs. Our results demonstrate that the co-staining of OMVs with osmium tetroxide and UA can better preserve the structure of vesicles, resulting in higher-quality images.

OMVs from ETBF and NTBF were isolated from stationary bacterial cultures using the ExoBacteria OMV Isolation Kit (System Biosciences, EXOBAC100A-1) as per the manufacturer’s instructions and were concentrated using centrifugal concentration tubes (Thermo Scientific, 88532).

Concentrated vesicles were stained with UA or co-stained with osmium trioxide and UA. For UA, formvar-coated copper grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) were incubated on 10 µL drops of OMV-containing solution for 5 min, followed by two washes on deionized water drops for 2.5 min each and finally staining with 2% UA for 1 min. For the osmium tetroxide and UA co-stain, 10 µL of OMVs were mixed with an equivalent volume of 4% osmium tetroxide for 10 min on formvar-coated copper grids followed by staining with 2% UA for 1 min. All grids had excess liquid blotted off with filter paper and were allowed to dry overnight. The grids were then imaged using a TEM (JEM-1010, JEOL Inc., Tokyo, Japan) at 60 kV with a spot size of 2 and a magnification of ×50 000; a minimum of seven images per test condition were obtained.

The diameter and size of OMVs were measured using the Olympus CellSens Dimensions Software (Olympus America Inc., Version 2.2). Prior to analysis, a number generator was used to pick five random images per experiment to sample for counting. To determine the ‘roundness’ of the OMVs, we used Eq. 1 as previously described [33]. Briefly, the diameter of the OMVs in the x-direction was divided by the diameter from the y-direction and subtracted from 1, and the absolute value of the resulting number was then recorded. Values closer to 0 indicate a rounder shape, while values closer to 1 indicate a more linear form.

|

(1) |

Contributor Information

Aadil Sheikh, Department of Biology, Baylor University, One Bear Place #97046, Waco, TX 76798, USA.

Bernd Zechmann, Center for Microscopy and Imaging, Baylor University, One Bear Place #97046, Waco, TX 76798, USA.

Christie M Sayes, Department of Environmental Science, Baylor University, One Bear Place #97046, Waco, TX 76798, USA.

Joseph H Taube, Department of Biology, Baylor University, One Bear Place #97046, Waco, TX 76798, USA.

K. Leigh Greathouse, Department of Biology, Baylor University, One Bear Place #97046, Waco, TX 76798, USA; Nutrition Sciences, Baylor University, One Bear Place #97311, Waco, TX 76798, USA.

Funding

Funding for this project was provide by a grant to K.L.G. from the NIH (1R15AI156742). Funding support for A.S. was provided by Baylor University Biology Department.

References

- 1. Griffin S, Masood M I, Nasim M J, Sarfraz M, Ebokaiwe A P, Schäfer K H, Keck C M, and Jacob C (2018) Natural nanoparticles: a particular matter inspired by nature. Antioxidants 7: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stanley S (2014) Biological nanoparticles and their influence on organisms. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 28: 69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tsatsaronis J A, Franch-Arroyo S, Resch U, and Charpentier E (2018) Extracellular vesicle RNA: a universal mediator of microbial communication? Trends Microbiol. 26: 401–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Raposo G and Stoorvogel W (2013) Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 200: 373–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ahmadi Badi S, Bruno S P, Moshiri A, Tarashi S, Siadat S D, and Masotti A (2020) Small RNAs in outer membrane vesicles and their function in host-microbe interactions. Front. Microbiol. 11: 1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anand S, Samuel M, Kumar S, and Mathivanan S (2019) Ticket to a bubble ride: cargo sorting into exosomes and extracellular vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Proteins Proteom. 1867: 140203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Becker A, Thakur B K, Weiss J M, Kim H S, Peinado H, and Lyden D (2016) Extracellular vesicles in cancer: cell-to-cell mediators of metastasis. Cancer Cell 30: 836–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hinger S A, Cha D J, Franklin J L, Higginbotham J N, Dou Y, Ping J, Shu L, Prasad N, Levy S, Zhang B, and Liu Q (2018) Diverse long RNAs are differentially sorted into extracellular vesicles secreted by colorectal cancer cells. Cell Rep. 25: 715–725.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Latifkar A, Hur Y H, Sanchez J C, Cerione R A, and Antonyak M A (2019) New insights into extracellular vesicle biogenesis and function. J. Cell. Sci. 132: jcs222406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gao X-J, Li T, Wei B, Yan Z X, Hu N, Huang Y J, Han B L, Wai T S, Yang W, and Yan R (2018) Bacterial outer membrane vesicles from dextran sulfate sodium–induced colitis differentially regulate intestinal UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 partially through toll-like receptor 4/mitogen-activated protein kinase/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. Drug Metab. Dispos. 46: 292–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kulkarni H M and Jagannadham M V (2014) Biogenesis and multifaceted roles of outer membrane vesicles from Gram-negative bacteria. Microbiology 160: 2109–2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Malabirade A, Habier J, Heintz-Buschart A, May P, Godet J, Halder R, Etheridge A, Galas D, Wilmes P, and Fritz J V (2018) The RNA complement of outer membrane vesicles from Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium under distinct culture conditions. Front. Microbiol. 9: 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jun S H, Lee J H, Kim B R, Kim S I, Park T I, Lee J C, and Lee Y C (2013) Acinetobacter baumannii outer membrane vesicles elicit a potent innate immune response via membrane proteins. PLoS One 8: e71751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Behrouzi A, Vaziri F, Riazi Rad F, Amanzadeh A, Fateh A, Moshiri A, Khatami S, and Siadat S D (2018) Comparative study of pathogenic and non-pathogenic Escherichia coli outer membrane vesicles and prediction of host-interactions with TLR signaling pathways. BMC Res. Notes 11: 539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Durant L, Stentz R, Noble A, Brooks J, Gicheva N, Reddi D, O’Connor M J, Hoyles L, McCartney A L, Man R, and Pring E T (2020) Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron-derived outer membrane vesicles promote regulatory dendritic cell responses in health but not in inflammatory bowel disease. Microbiome 8: 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chuo S T-Y, Chien J C-Y, and Lai C P-K (2018) Imaging extracellular vesicles: current and emerging methods. J. Biomed. Sci. 25: 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reimer S L, Beniac D R, Hiebert S L, Booth T F, Chong P M, Westmacott G R, Zhanel G G, and Bay D C (2021) Comparative analysis of outer membrane vesicle isolation methods with an Escherichia coli tolA mutant reveals a hypervesiculating phenotype with outer-inner membrane vesicle content. Front. Microbiol. 12: 628801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Potter M, Hanson C, Anderson A J, Vargis E, and Britt D W (2020) Abiotic stressors impact outer membrane vesicle composition in a beneficial rhizobacterium: Raman spectroscopy characterization. Sci. Rep. 10: 21289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schwechheimer C and Kuehn M J (2015) Outer-membrane vesicles from Gram-negative bacteria: biogenesis and functions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13: 605–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roier S, Zingl F G, Cakar F, Durakovic S, Kohl P, Eichmann T O, Klug L, Gadermaier B, Weinzerl K, Prassl R, and Lass A (2016) A novel mechanism for the biogenesis of outer membrane vesicles in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Commun. 7: 10515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang J, Yao Y, Wu J, and Li G (2015) Identification and analysis of exosomes secreted from macrophages extracted by different methods. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 8: 6135–6142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Théry C, Amigorena S, Raposo G, and Clayton A (2006) Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 30: 3.22.1–3.22.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stempak J G and Ward R T (1964) An improved staining method for electron microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 22: 697–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Watson M L (1958) Staining of tissue sections for electron microscopy with heavy metals. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 4: 475–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Howatson J, Grev D M, and Morosin B (1975) Crystal and molecular structure of uranyl acetate dihydrate. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 37: 1933–1935. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pandithage R Brief Introduction to Contrasting for EM Sample Preparation. Oct 2013, Accessed: Dec 01, 2022. Available: https://www.leica-microsystems.com/science-lab/brief-introduction-to-contrasting-for-em-sample-preparation/.

- 27. Nevot M, Deroncelé V, Messner P, Guinea J, and Mercadé E (2006) Characterization of outer membrane vesicles released by the psychrotolerant bacterium Pseudoalteromonas antarctica NF3. Environ. Microbiol. 8: 1523–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Almgren M, Edwards K, and Karlsson G (2000) Cryo transmission electron microscopy of liposomes and related structures. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 174: 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thompson R F, Walker M, Siebert C A, Muench S P, and Ranson N A (2016) An introduction to sample preparation and imaging by cryo-electron microscopy for structural biology. Methods 100: 3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wigglesworth V B (1957) The use of osmium in the fixation and staining of tissues. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B: Biol. Sci. 147: 185–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Belazi D, Solé-Domènech S, Johansson B, Schalling M, and Sjövall P (2009) Chemical analysis of osmium tetroxide staining in adipose tissue using imaging ToF-SIMS. Histochem. Cell Biol. 132: 105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Griffith W P (1974) Osmium tetroxide and its applications. Johnson Matthey Technol. Rev. 18: 94–96. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lujan H, Mulenos M R, Carrasco D, Zechmann B, Hussain S M, and Sayes C M (2021) Engineered aluminum nanoparticle induces mitochondrial deformation and is predicated on cell phenotype. Nanotoxicology 15: 1215–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]