Abstract

Purpose

Tension band wiring is the standard treatment for olecranon fractures, but it is associated with high rate of implant-related complication. To reduce this high complication rate, we developed a modified technique, locked tension band wiring (LTBW). The aim of this study was to investigate whether LTBW reduces complication and reoperation rates compared to conventional methods (CTBW).

Methods

We identified 213 olecranon fractures treated with tension band wiring: 183 were treated with CTBW, and 30 were treated with LTBW, and patients in each group were selected using propensity score matching. We evaluated operation time, intraoperative bleeding, complication and reoperation rates, the amount of Kirschner’s wire (K-wire) back-out, and Mayo Elbow Performance Index (MEPI). Complications included nonunion, loss of fracture reduction, implant failure, infection, neurological impairment, heterotopic ossification, and implant irritation. Implant removal included at the patient's request with no symptoms.

Results

We finally investigated 29 patients in both groups. The mean operation time was significantly longer in the LTBW (106.7 ± 17.5 vs. 79.7 ± 21.1 min; p < 0.01). Complication rates were significantly lower in the LTBW than the CTBW group (10.3 vs. 37.9%; p = 0.03). The rate of implant irritation was more frequent in the CTBW, but there was no significant difference (3.4 vs. 20.7%; p = 0.10). Removal rate was significantly lower in the LTBW (41.4 vs. 72.4%; p = 0.03). The mean amount of K-wire backout at last follow-up was significantly less in the LTBW (3.79 ± 0.65 mm vs. 8.97 ± 3.54 mm; p < 0.01). There were no significant differences in mean MEPI at all follow-up periods (77.4 ± 9.0 vs. 71.5 ± 14.0; p = 0.07, 87.4 ± 7.2 vs. 85.2 ± 10.3; p = 0.40, 94.6 ± 5.8 vs. 90.4 ± 9.0; p = 0.06, respectively).

Conclusion

Our modified TBW significantly increased operation time compared to conventional method, but reduced the complication and removal rate and had equivalent functional outcomes in this retrospective study.

Keywords: Tension band wiring, Olecranon fracture, Mayo Elbow Performance Index, Modified surgical technique, Complication, Implant irritation

Introduction

Olecranon fractures are relatively common fractures that reportedly account for approximately 10% of all upper extremity fractures [1]. Tension band wiring (TBW) is widely used for displaced olecranon fractures that utilize Kirschner's wire (K-wire) and flexible wire. Previous studies showed that TBW achieved good clinical outcomes but a high complication and reoperation rate and the most frequent complication was reported the implant irritation [2–4]. The main cause of this high rate of complications is thought to be due to the K-wire migration pulled by the triceps. Mitsuya et al. first reported a simple modified method called locked tension band wiring (LTBW) which the proximal part of the TBW was locked by wrapping it with flexible wires and the method showed significantly less amount of K-wire backout compared with conventional TBW (CTBW) in their retrospective study [5]. Authors considered it effective to reduce the implant irritation and have reported that LTBW achieved postoperative complication rate equivalent to locked plate for simple olecranon fractures with the same database of this study in a previous report. [6]

The purpose of this study was to establish the efficacy of our modified TBW as a treatment method for olecranon fractures. To achieve our goal, we compared (1) the frequency of complications and reoperations, and (2) the functional outcomes between LTBW and CTBW. We hypothesized that LTBW would reduce postoperative implant-related complications and reoperation rates compared to CTBW.

Materials and Methods

Locked Tension Band Wiring

All patients who received LTBW were operated in the supine position. An "S" shaped posterior approach with a medial arc from the triceps to the ulna was used to prevent skin contracture. The ulnar nerve was routinely identified but not dissected or transposed. A 1.5-mm K-wire was inserted perpendicular to the ulna approximately 30 mm distal to the fracture site. Using the K-wire as a foothold, we reduced and held the fragments with one- or two-point reduction forceps.

Two 1.5-mm K-wires were placed in parallel and bi-cortically. A 1.0-mm flexible wire was placed and fastened in a figure-of-eight configuration using the double-knot method. At this point, the proximal ends of the K-wires were bent at a right angle, their bent portions overlapped on top of each other, and then cut to leave approximately 1 mm from the overlapping portions. The K-wires and figure-of-eight wire were lifted slightly off the triceps using an elevator, and the proximal bent portions of the K-wires and figure-of-eight wire were coiled and fixed with a 0.5-mm flexible wire. The proximal portions of the K-wires were not embedded in the triceps brachii tendon but only hammered into them. The figure-of-eight wire was re-tightened at the fastener, and the fracture was compressed, following which the excess metal wire was cut to reduce skin irritation. Finally, we confirmed that the fracture was correctly restored under fluoroscopy and that internal fixation was completed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Surgical procedure for locked tension band wiring: a The fracture was crimped using pointed reduction forceps and tension band wiring in a double knot according to the AO surgical reference. b The proximal end of the K-wires was bent at a right angle. c, d An elevator was used to create a gap between the bent portion of the K-wires and the figure-of-eight wire, and the triceps. The proximal bent portions of the K-wires and the figure-of-eight wire were coiled and fixed with a 0.5-mm flexible wire (white arrow). e, f Postoperative X-rays indicated that the proximal end of the K-wires and the figure-of-eight wire were fixed with the flexible wire. In this case, there were multiple bone fragments, so additional flexible wire was used for the circular wiring to improve stability (color figure online)

Subjects

Data from the hospitals of a trauma research group were extracted for this study. This registry collects data about all orthopedic trauma patients referred to participating hospitals, with data having been registered annually since 2014. Thirteen hospitals participating in the database were all associated with the Department of Orthopedic Surgery of our university, and 63 orthopedic surgeons perform the surgery at these hospitals.

All eligible patients were registered using an opt-out consent process. Patients were provided with a letter and a brochure informing them that they had been registered, the purpose of the registration, and the procedure to remove themselves from the registry. The registry received ethical approval from all participating institutions, and this study received institutional ethical approval (reference number 2020–564).

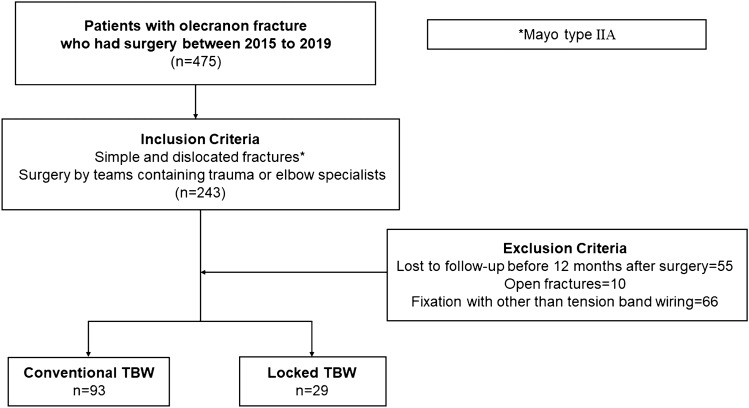

We extracted data from the database on 475 patients who were treated with surgery for olecranon fractures from 2014 to 2019. We only included patients with simple olecranon fractures (Mayo type IIA) treated by a team that included at least one trauma or elbow orthopedic surgeon with more than 10 years of experience. We excluded patients (a) treated with other than TBW, (b) with open fractures, and (c) followed up for less than 6 months (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Patient flow in this study. We only included patients with simple and displaced olecranon fractures (Mayo IIA) treated by a team that included at least one trauma or elbow orthopedic surgeon with more than 10 years of experience. Patients with open fractures and those treated with other than tension band wiring (TBW) were excluded. We identified 122 patients with olecranon fractures treated with TBW: 93 were treated with a conventional TBW method, and 29 were treated with locked TBW

Clinical Evaluation

The following demographic data were extracted for each patient: (a) background factors: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and Charlson’s comorbidity index (CCI) [7]; (b) injury factors: injury mechanism, injury side (dominant arm or not), and Mayo classification [8]; and (c) operation factors: operation time and intraoperative blood loss from medical records in each participating institution. High-energy trauma was defined as anything worse than a fall from a second floor or traffic accidents between pedestrians or motorcycles and automobiles, whereas low-energy trauma was defined as a fall from a standing position [9]. Operation time was measured from skin incision to wound closure, and blood loss was calculated from gauze and suction.

We evaluated postoperative complications, reoperation, and K-wire backout from patients' medical records and radiographic data. Postoperative complications included the loss of fracture reduction, irritation by the implants, superficial or deep infection, heterotopic ossification [10], and neurological damage. Superficial or deep infection was determined according to the criteria of Horan et al. [11] The occurrence of any sensory or motor disturbance, or numbness was defined as neurological impairment [12]. Implant removal due to patient request without any symptoms was included in this study. The amount of K-wire backout was measured by the distance between the proximal surface of the ulna and proximal K-wire prominence in lateral radiographs. [13]

The main surgeon assessed the Mayo Elbow Performance Index (MEPI) at 3-, 6-, and 12-month postoperative follow-ups. MEPI assesses pain, range of motion, stability, and ability of daily function (combing hair, eating by oneself, self-hygiene management, and putting on shirts and shoes). [14]

Statistical Analysis

Categorical data were compared between the two groups using Fisher's exact test. Welch's T-test was performed for the analysis of all continuous variables. Radiographic assessment was reviewed by two orthopedic trauma surgeons (YK, SM). We calculated intraclass correlation coefficients (continuous variable) and Kappa coefficient (categorical data) for inter-observer reliability, which were 0.76 and 0.81, respectively. We evaluated missing MEPI data by a multiple imputation method using the Expectation–Maximization with Bootstrapping algorithm [15]. The logistic regression model was used to calculate the odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for risks of symptomatic removal. The significance level was set at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Jichi Medical School, Tochigi, Japan). [16]

Results

We investigated 29 and 93 patients with LTBW and CTBW, respectively. The mean follow-up period was 13.1 ± 2.5 months (range, 6–24 months). The baseline characteristics of the patients and their fractures are presented in Table 1. The mean age in the LTBW group was slightly older than that in the CTBW group, but the difference was not significant (67.0 ± 11.9 vs. 60.8 ± 18.5; p = 0.090). The proportion of smokers was significantly higher in the LTBW group (mean 34.5% vs. 15.1%; p = 0.032).

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| CTBW | LTBW | p.value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number, n | 93 | 29 | |

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 60.8 ± 18.5 | 67.0 ± 11.8 | 0.090 |

| Sex, M/F, n | 29/64 | 14/15 | 0.120 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean, (range) | 21.7 ± 4.0 | 23.3 ± 3.2 | 0.043 |

| Charlson comorbidity score, n (%) | 0.586 | ||

| Low (0) | 64 (68.8) | 17 (58.6) | |

| Median (1–2) | 22 (23.7) | 10 (34.5) | |

| High (3–4) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Very high (≥ 5) | 6 (6.5) | 2 (6.9) | |

| Smoking, n (%) | 14 (15.1) | 10 (34.5) | 0.032 |

| Injury mechanism, n (%) | 0.331 | ||

| Low energy | 67 (72.0) | 24 (82.8) | |

| High energy | 26 (28.0) | 5 (17.2) | |

| Injury at dominant side, n (%) | 39 (41.9) | 14 (48.3) | 0.668 |

SD Standard deviation, BMI Body mass index, CTBW conventional tension band wiring, LTBW locked tension band wiring

Operative time was significantly longer for LTBW than CTBW (mean 107.7 ± 20.2 vs. 79.3 ± 30.2 min; p < 0.001). The rate of postoperative complications was significantly lower in the LTBW group than in the CTBW group (10.3% vs. 30.1%; p = 0.048). Two out of 29 patients in the LTBW group (6.9%) complained of implant irritation and 23 out of 93 patients (24.7%) in the CTBW group, and the difference was significant (p = 0.032). Three patients experienced implant failure and two out of them were performed re-implantation surgery. Two patients in the CTBW group developed postoperative infection. One was a superficial infection that was treated with antibiotics for a week, and the other was a deep infection that received implant removal. The reoperation rate in the LTBW group was lower than that in the CTBW group, but there was no significant difference (10.3% vs. 25.8%; p = 0.122). The most common reason for reoperation was implant irritation. Three patients experienced early postoperative superficial infection, two patients were cured with intravenous antibiotics only without reoperation, and one patient in the CTBW group required implant removal (Table 2). The mean back out of K-wires in the LTBW group at the last follow-up was significantly less than that in the CTBW group (3.7 ± 0.5 vs. 5.2 ± 1.9 mm, p < 0.001). The mean postoperative K-wire backout at the last follow-up was associated with a high risk of symptomatic implant removal in the logistic regression analysis (OR, 1.32; 95% CI 1.01–1.71; p = 0.039).

Table 2.

Intraoperative and postoperative outcomes

| CTBW | LTBW | p. value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number, n | 93 | 29 | |

| Operation time, min, mean ± SD | 79.3 ± 30.0 | 107.7 ± 20.2 | < 0.001 |

| Complication*, n (%) | 28 (30.1) | 3 (10.3) | 0.048 |

| Implant failure, n (%) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Infection, n (%) | 2 (2.2) | 1 (3.4) | 0.560 |

| Neurological symptoms, n (%) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Heterotopic ossification, n (%) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Irritation, n (%) | 23 (24.7) | 2 (6.9) | 0.038 |

| Reoperation, n (%) | 24 (25.8) | 3 (10.3) | 0.122 |

| Removal, n (%) | 66 (71.0) | 12 (41.4) | 0.007 |

| Patients’ request, n (%) | 42 (63.6) | 10 (83.3) | |

| Irritation, n (%) | 22 (33.3) | 2 (16.7) | |

| Infection, n (%) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Implant failure, n (%) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Postoperative K-wire displacement, mm, mean (SD) | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

|

K-wire displacement at last follow-up, mm, mean (SD) |

5.2 ± 1.9 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | < 0.001 |

SD standard deviation, CTBW conventional tension band wiring, LTBW locked tension band wiring

*There are some duplications in number of complications

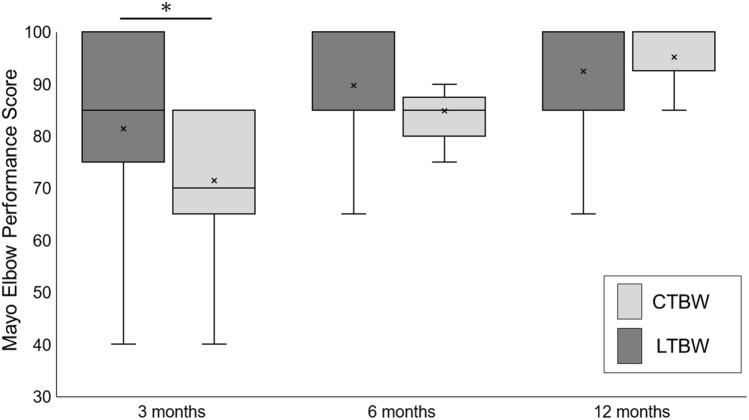

The mean MEPI at 3 months was 71.4 ± 14.1 (range 40–85) in the LTBW group versus 81.4 ± 18.1 (range 30–100) in the CTBW group, which was significantly different (p = 0.012). However, there were no significant differences in the mean MEPI at 6 and 12 months between the two groups (84.8 ± 8.7 vs. 89.8 ± 13.5; p = 0.087 and 95.2 ± 6.4 vs. 92.4 ± 9.9; p = 0.186, respectively) (Fig. 3). There was a significant difference in mean pain scores at 3 months (32.1 ± 10.1 vs. 24.0 ± 7.5 points; p < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Box plots for Mayo Elbow Performance Index (MEPI) at 3, 6, and 12 months by intervention group. Boxes show upper and lower interquartile ranges with the median indicated by the black horizontal line, and dots in boxes represented the mean. * indicates a significant difference between the two groups. MEPI in LTBW was significantly lower than that in CTBW at 3 months (71.4 ± 14.1 vs. 81.4 ± 18.1; p = 0.012). There was no significant difference in MEPI between the two groups at 6 and 12 months (84.8 ± 8.7 vs. 89.8 ± 13.5; p = 0.087 and 95.2 ± 6.4 vs. 92.4 ± 9.9; p = 0.186, respectively). CTBW, conventional tension band wiring, LTBW locked tension band wiring

Discussion

Our modified method, LTBW, decreased the complication and removal rates compared to CTBW in our retrospective cohort. Powell et al. reported that the complication rate of TBW was 33.3%, and the removal rate of TBW for hardware irritation was 27.1%. Rantalaiho et al. [17] showed 148 of 387 patients (48.8%) had early complications and 129 of 387 patients (33.3%) had removal surgery of implant. Tan et al. [18] showed the removal rate due to symptomatic hardware was 21.6%. The complication rate of CTBW in our study (30.1%) was comparable to that in these studies, and the implant removal rate related to symptomatic implants in this study was 24.7% in CTBW and 10.3% in LTBW, which was comparable to that in previous studies (20–50%). [2–4, 17–19]

The theory of the LTB is that the union of the K-wires and figure-of-eight wire at the proximal end is expected to reduce back-out because the compressive force of TBW is used to stabilize the K-wires. Previous studies using a cable system, which was thought to have the same effect as LTBW, showed significantly fewer implant-related complications than CTBW [3, 20]. However, the price of the initial implant for the cable pin system is much higher than that of the LTBW in our country (mean $744 vs. $47, respectively). Kinik et al. reported that their self-locking tension band wiring, in which the proximal K-wire ends were bent to form a loop and the figure-eight wire passed through them, resulted in no adverse event in their case-series study [21]. These results suggested that locking the K-wire proximal ends and the figure-eight wire reduced the implant-related complications compared with CTBW.

Early postoperative MEPI in LTBW was worse than that in CTBW. The difference in pain score was a major factor in the poor early postoperative MEPI in LTBW. The K-wire proximal ends were bent along the fibers of the triceps in CTBW so that the K-wires can be embedded in the triceps. However, this is impossible with LTBW because the proximal ends of the K-wires are bent perpendicular to the fibers of the triceps and are hammered into the triceps. The distance from olecranon to the proximal K-wires in LTBW was significantly more than that in CTBW (2.9 ± 0.4 vs. 2.0 ± 0.9; p < 0.001). Therefore, LTBW is considered to have greater irritation to the triceps muscle or posterior elbow by the proximal K-wire ends, which might have caused more pain. However, there was no significant difference in MEPI between LTBW and CTBW and the authors have never observed the triceps injuries at the time of implant removal. The implant can be removed by cutting a part of the distal flexible wire and pulling it out proximally; therefore, there is virtually no possibility of damaging the triceps muscle during removal.

This study has some limitations. This study was retrospective, therefore it could have an inherent risk of observer and selection bias, including the potential for missing data and the inability to control confounding variables. LTBW was performed only by two of the authors (YK and SM) and their colleagues. Although TBW was performed by skilled trauma or elbow orthopedic surgeons, the skill of the surgeon might have affected the outcome. To further reduce the α error, the authors did not collect the LTBW data directly. This study had a short follow-up period (6 months or more). Chalidis et al. [22] showed that 48.8% of patients with olecranon fractures had a degenerative articular change in their long-term study. Therefore, long-term prospective studies are required to demonstrate the efficacy of LTBW. The protocols for outpatient care, postoperative rehabilitation, and reoperation were not standardized and followed the policies of the attending physicians and institutions in the present study. This study included hospitals that did not have facilities for adequate postoperative rehabilitation by occupational therapists, which is also the case with the main institution of the LTBW group; if they were standardized, the results could be affected. The mean age in the LTBW group was higher than that in the CTBW group, which was not significantly different, and it might result in a higher tolerance for hardware irritation. However, the mean age of patients who underwent implant removal was 62.9 ± 17.8 and that of patients who did not was 59.6 ± 15.7, and the difference was not significant (p = 0.375). The total removal rate was higher than that reported in previous studies (LTBW: 41.4%, CTBW: 71.0%) [2–4]. These results might be due to the fact that implants were removed 1 year after surgery or after bone union, and some insurance coverage included removal of implants even if asymptomatic in our country. To ensure that all cases were considered, patients who underwent implant removal for potential irritation were not excluded from the study even if they did not exhibit specific symptoms noted by their surgeon. The present study showed that the implant removal rate, including patient preference, was significantly lower in LTBW than in CTBW.

Conclusion

We introduced a modified technique for olecranon fractures, and locked tension band wiring. This retrospective study showed that LTBW significantly reduced the complication rates, removal rates, and the amount of K-wire migration compared to CTBW, but significantly increased surgery time. We believe that prospective studies such as randomized controlled trials and comparative studies with locking plates are needed to further demonstrate the efficacy of our modified TBW.

Acknowledgements

We thank both participating hospitals of the trauma research group associated with the Department of Orthopedic Surgery of Nagoya University for their contribution of data to this study and the members of the trauma research group. Special thanks to Yotaro Yamada, Yuma Saito, Ryutaro Shibata, Yasushi Hiramatsu, Yutaro Ono, Kentaro Komaki, Yui Matsura, Koichiro Makihara, Saki Sakurai, Ken Mizuno, Yusuke Mori, and Reika Kaneko for data collection.

Author Contributions

YK: data collection and assessment, study design, and writing the paper. YT: manuscript preparation, study and conception design. SM: conception design. KT: manuscript preparation and study design. KY: data collection and assessment, and manuscript preparation. SI: conception design and guarantor.

Funding

This study has no funding support.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.van der Horst CM, Keeman JN. Treatment of olecranon fractures. The Netherlands Journal of Surgery. 1983;35:27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powell AJ, Farhan-Alanie OM, McGraw IWW. Tension band wiring versus locking plate fixation for simple, two-part Mayo 2A olecranon fractures: a comparison of post-operative outcomes, complications, reoperations and economics. Musculoskeletal Surgery. 2019;103:155–160. doi: 10.1007/s12306-018-0556-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu QH, Fu ZG, Zhou JL, Lu T, Liu T, Shan L, Liu Y, Bai L. Randomized prospective study of olecranon fracture fixation: cable pin system versus tension band wiring. Journal of International Medical Research. 2012;40:1055–1066. doi: 10.1177/147323001204000324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duckworth AD, Clement ND, White TO, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM. Plate versus tension-band wire fixation for olecranon fractures: a prospective randomized trial. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 2017;99:1261–1273. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitsuya M, Mitsuya S, Hasegawa J, Fukui J, Fujita M, Yamauchi K. Comparison between conventional tension band wiring and locking tension band wiring can prevent back out for olecranon fractures. Cent Jp J Orthop Traumat. 2018;61:467–468. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuwahara Y, Takegami Y, Mitsuya S, Tokutake K, Yamauchi K, Imagama S. Locked tension band wiring for mayo IIA olecranon fractures: modified surgical technique and retrospective comparative study of clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness with locking plate. J Hand Surg Asian Pac. 2023;28(2):205–213. doi: 10.1142/S2424835523500224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1994;47:1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrey BF. Current concepts in the treatment of fractures of the radial head, the olecranon and the coronoid. Instructional Course Lectures. 1995;44:175–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sasser SM, Hunt RC, Faul M, et al. Guidelines for field triage of injured patients: recommendations of the national expert panel on field triage, 2011. MMWR - Recommendations and Reports. 2012;61:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shehab D, Elgazzar AH, Collier BD. Heterotopic ossification. Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 2002;43:346–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, et al. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. American Journal of Infection Control. 1992;20:271–274. doi: 10.1016/S0196-6553(05)80201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carbonell-Escobar R, Vaquero-Picado A, Barco R, Antuña S. Neurologic complications after surgical management of complex elbow trauma requiring radial head replacement. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2020;29:1282–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.01.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saeed ZM, Trickett RW, Yewlett AD, Matthews TJ. Factors influencing K-wire migration in tension-band wiring of olecranon fractures. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2014;23:1181–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrey BF, An K, Chao E. Functional evaluation of the elbow. In: Morrey BF, editor. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 2. WB Saunders; 1993. pp. 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ni X, Yuan K, Liu C, Feng Q, Tian L, Ma Z, Xu S. MultiWaver 2.0: modeling discrete and continuous gene flow to reconstruct complex population admixtures. Eur J Hum Genet 2019; 27: 133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software "EZR" for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2013;48:452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rantalaiho IK, Laaksonen IE, Ryösä AJ, Perkonoja K, Isotalo KJ, Äärimaa VO. Complications and reoperations related to tension band wiring and plate osteosynthesis of olecranon fractures. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2021;30(10):2412–2417. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2021.03.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan BYJ, Pereira MJ, Ng J, Kwek EBK. The ideal implant for Mayo 2A olecranon fractures? An economic evaluation. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2020;29(11):2347–2352. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navarro RA, Hsu A, Wu J, Mellano C, Sievers D, Alfaro D, Foroohar A. Complications in olecranon fracture surgery: a comparison of tension band Vs. Plate Osteosynthesis. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2022;10(10):863–870. doi: 10.22038/ABJS.2021.59214.2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimura H, Nimura A, Fujita K, Kaburagi H. Comparison of the efficacy of the tension band wiring with eyelet wire versus anatomical locking plate fixation for the treatment of displaced olecranon fractures. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery (Hong Kong) 2021;29(3):23094990211059231. doi: 10.1177/23094990211059231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinik H, Us AK, Mergen E. Self-locking tension band technique. A new perspective in tension band wiring. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1999; 119(7–8): 432–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Chalidis BE, Sachinis NC, Samoladas EP, Dimitriou CG, Pournaras JD. Is tension band wiring technique the “gold standard” for the treatment of olecranon fractures? A long term functional outcome study. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 2008;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.