Abstract

Background

Deleterious germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are associated with a high risk of breast and ovarian cancer. In many developing countries, including Egypt, the prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations among women with breast cancer (BC) is unknown.

Aim

We aimed to determine the prevalence of deleterious germline BRCA mutations in Egyptian patients with breast cancer.

Methods

We report the results of a cohort study of 81 Egyptian patients with breast cancer who were tested for germline BRCA1/2 mutations during routine clinical practice, mostly for their young age of presentation, BC subtype, or presence of family history. In addition, we searched five databases to retrieve studies that reported the prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutation status in Egyptian women with BC. A systematic review of the literature was performed, including prospective and retrospective studies.

Results

In our patient cohort study, 12 patients (14.8%) were positive for either BRCA1/2 deleterious mutations. Moreover, 13 (16.1%) patients had a variant of unknown significance (VUS) of BRCA1/2 genes. Twelve studies were eligible for the systematic review, including 610 patients. A total of 19 deleterious germline mutations in BRCA1/2 were identified. The pooled prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations was 40% (95% confidence interval 1–80%).

Conclusion

The reported prevalence was highly variable among the small-sized published studies that adopted adequate techniques. In our patient cohort, there was a high incidence of VUS in BRCA1/2 genes. Accordingly, there is an actual demand to conduct a prospective well-designed national study to accurately estimate the prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations among patients with BC in Egypt.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40487-023-00240-9.

Keywords: Breast cancer, BRCA1, BRCA2, Mutations, Egypt

Key Summary Points

| Germline BRCA1/2 mutation landscape is not adequately studied in Egyptian patients with breast cancer. |

| Available studies are heterogeneous and showed variable degrees of reporting bias. |

| In our single center experience, prevalence of germline BRCA1/2 mutation was 14.8% in addition to 16.1% with a variant of unknown significance (VUS). |

Introduction

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are tumor suppressor genes involved in the maintenance of DNA homologous recombination repair. Hence, their loss leads to the accumulation of damaged DNA, which dramatically increases susceptibility to cancer development [1]. In Caucasian populations, women carrying deleterious germline mutations in BRCA1/2 (gBRCA) have a 60–75% cumulative risk of developing breast cancer (BC) by the age of 80 versus 12% in non-carriers [2].

During the last two decades, gBRCA mutation status has evolved as a relevant topic in managing patients with BC, especially those diagnosed at a young age. Patients with BC with gBRCA mutations would require genetic counseling and are candidates for several unique treatment decisions. For example, in the OLYMPIA trial, patients with high-risk early breast cancer carrying a gBRCA1/2 mutation, and who had completed neo/adjuvant chemotherapy, were randomized to either receive olaparib or placebo. In this setting, olaparib could improve invasive disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) compared with placebo [3]. In addition, two randomized trials, OLYMPIAD and EMBRACA recruited patients with metastatic breast cancers and gBRCA1/2 mutations to compare two PARP inhibitors, olaparib and talazoparib, versus the physician’s choice of chemotherapy [4, 5]. Both studies showed that PARP inhibitors could improve the progression-free survival compared with chemotherapy [4]. In the western literature, the prevalence of gBRCA mutations is estimated at 3–5% in the unselected patients with BC, which jumps to 10–15% among women diagnosed with BC at ≤ 40 years of age. The prevalence of pathogenic BRCA mutations does not only vary by age and family history, but it may differ according to geography, race, and ethnicity. For instance, the frequency of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers is reported to occur around ten times higher among the Ashkenazi Jewish population than the general Caucasian population [6, 7].

Egypt is the most populous nation in the Arab world and the third most populous nation in Africa, with a population of around 105 million. It is characterized by divergent ethnic origins with a relatively high BC incidence rate of 48.8/100,000, accounting for 32% of all women’s cancers in Egypt [8]. In line with other developing countries, the median age of BC in Egypt is 50 years, which is at least 10 years younger than in western nations [9]. This might theoretically suggest a higher prevalence of BRCA mutations among these women. This hypothesis was proposed by an early Egyptian study, where the prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations was reported to be as high as 86% [10]. Ever since then, several other studies have reported substantially diverse findings [11–13], underscoring the need to refine evidence regarding the true prevalence of gBRCA in the Egyptian population.

Here, we report the results of a retrospective cohort study of patients with breast cancer who have tested for germline BRCA 1 or 2 mutations (gBRCA1/2) during routine practice. In addition, we performed a systematic review of all studies that reported the prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutation among patients with BC in Egypt.

Methods

Retrospective Analysis

We searched the records of Cairo Oncology Center between January 2012 and December 2021 for all patients with breast cancer who underwent germline BRCA testing. Eligible patients should have had histologically proven breast cancer. The patients’ age, stage, histopathological subtype and grade, estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), HER2, KI67, and family history of breast cancer information were collected. The breast cancer biological subtype was determined using the St Gallen 2015 criteria as a surrogate for gene expression profiling. Tumors were considered luminal A-like if positive for ER and PR, negative for HER2 overexpression, and low proliferation (as determined by grade 1 or grade 2 with Ki-67 20% and/or low mitotic index), and tumors were considered luminal B-like if positive for ER and with one of the following: negative for PR, positive for HER2 overexpression, or high proliferation (as determined by grade 3, Ki-67 > 20%, or high mitotic index). Tumors were considered to be HER2-enriched subtype if negative for ER and PR and with HER2 overexpression. Finally, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) had to be negative for ER, PR, and HER2. Before genetic testing, written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Genetic Testing

The patients were offered gBRCA1/2 testing based on the clinicopathological features suggesting a probability of a pathogenic mutation of 10% or more [14]. Risk factors included: family history of one or more first-degree relatives with breast, ovarian, prostate, or pancreatic cancer, TNBC subtype, or an age of ≤ 40 years at breast cancer diagnosis. Sequencing was performed as previously published [15]. Briefly, a blood sample was obtained, and DNA was extracted from the sample using the Qiagen QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid kit. A targeted DNA library was generated using the Ion AmpliSeqTM BRCA1/2 Panel and sequenced by semiconductor-based next-generation sequencing technology on an Ion Torrent PGM [15]. Bioinformatics analyses (proprietary and Ion Torrent™ based) were conducted. The testing targeted the coding regions of the BRCA1 and the BRCA2 genes on a validated next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform.

Ethical Approval

All patients in the Cairo Oncology Center signed informed consent before germline testing. The Local COC Institutional Review Board (2019020501) have exempted retrospective analyses that does not involve personal patient data from further consents or approvals.

Systematic Review

We conducted a systematic literature review that utilized a comprehensive search of PubMed, Cochrane CENTRAL, SCOPUS, Google Scholar, and Web of Science from their inception till September 2021 using the following query: “(BRCA OR BRCA1 OR BRCA2) AND (Gene polymorphism OR Genetic mutation OR Genetic variation) AND (Breast cancer or Breast neoplasm or Breast neoplasia) AND (Egypt OR Egyptian). We also searched the bibliography of eligible studies to find relevant articles.

Both prospective and retrospective studies addressing the prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations among Egyptian female patients with BC were included. We excluded studies that focused on the BRCA gene, mainly without including patients with BC, and studies that reported the prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations in cancers other than BC (e.g., ovarian cancer). Also, reviews, case reports, and non-English articles were excluded. The review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Supplementary Materials) [16].

Data Extraction

Two authors extracted the following data from each included study: the number of patients, family history of BC, mean age at diagnosis of BC, regions covered, the prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutation, and the detection platform used. Any discrepancies were resolved by revision and discussion. The prevalence of discovered mutations found in each study was reported in number and percentage. Gene lollipops were generated using the ProteinPaint tool (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital—PeCan Data Portal).

Statistical Analysis

Numerical variables in the patient cohort were described in terms of the median (and range) or mean [± standard deviation (SD)] and compared using the student’s t test. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests. Pooling the proportions of patients carrying mutations in individual studies was performed using metaprop command in STATA 14.2 (StataCorp, LP, College Station, Texas, USA). The command performs meta-analyses of binomial data and allows the computation of 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the score statistic and the exact binomial method, and incorporates the Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformation of proportions [17].

Results

Patient Cohort Characteristics

A total of 81 patients were eligible for our analysis, with a median age of 41 years (range 21–85 years). A total of 45 patients (66.2%) had a positive family history of breast cancer. Twenty-five percent of the patients presented with metastatic disease. The majority had invasive duct carcinoma (NOS), and 15 patients (20.5%) had grade III tumors. A total of 58 patients had estrogen receptor (ER)-positive disease (71.6%), while HER2 was overexpressed in 9 patients (11.4%). Table 1 shows a summary of the patient’s characteristics.

Table 1.

Overall patient characteristics

| Characteristics | All patients |

|---|---|

| N | 81 |

| Age at diagnosis | |

| Median | 41 |

| Range | 21–85 |

| Family history of breast cancer | |

| Yes | 45 (66.2%) |

| No | 23 (33.8%) |

| Unknown | 13 |

| Histology | |

| IDC | 69 (85.2%) |

| ILC | 7 (8.6%) |

| Other | 5 (6.1%) |

| Histological grade | |

| I | 0 (0%) |

| II | 58 (79.5%) |

| III | 15 (20.5%) |

| Missing | 8 |

| Stage at diagnosis | |

| 0 | 1 (2.8%) |

| 1 | 12 (33.3%) |

| 2 | 10 (27.8%) |

| 3 | 4 (11.1%) |

| 4 | 9 (25%) |

| ER | |

| Positive | 58 (71.6%) |

| Negative | 23 (28.4%) |

| PR | |

| Positive | 51 (63%) |

| Negative | 30 (37%) |

| HER2 | |

| Positive | 9 (11.4%) |

| Negative | 70 (88.6%) |

| Unknown | 2 |

| Subtype | |

| Luminal A-like | 21 (25.9%) |

| Luminal B1-like | 32 (39.5%) |

| Luminal B2-like | 5 (6.2%) |

| HER2 enriched | 4 (4.9%) |

| Triple negative | 19 (23.5%) |

IDC infiltrating ductal carcinoma, ILC infiltrating lobular carcinoma, ER estrogen receptor, PR progesterone receptor, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor-2

Prevalence of Germline BRCA1/2 Mutations

Among the 81 patients, 12 patients (14.8%) were positive for either BRCA 1 or 2 deleterious mutations. Seven of them had deleterious mutations in BRCA1 (8.6%), while five patients (6.2%) had deleterious mutations in BRCA2. Moreover, 13 more patients had a VUS of BRCA1/2 genes (16.1%). Seven patients had a variant of unknown significance (VUS) in BRCA1 (8.6%), while six patients (7.4%) had a VUS in BRCA2.

Characteristics of the BRCA1/2 Mutant Population

The mean age at diagnosis in patients with BRCA 1/2 mutant was 33.5 years, while the mean age in patients with BRCA 1/2 non-mutant was 45.2 years (p < 0.001). Three of the patients with BRCA1 mutant (50%) and two of the patients with BRCA2 mutant (40%) had a family history of BC. All the patients with BRCA 1 and 2 mutant had infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC) histology. Four patients with BRCA 1 mutant (57.1%) were ER-positive, while all the patients with BRCA2 mutant were ER-positive. All the patients with BRCA 1/2 mutant were HER2 negative. The mean KI-67% score in patients with BRCA 1/2 mutant was 55.4, while the mean KI-67% score in patients with BRCA 1/2 non-mutant was 24.9 (p = 0.003). Table 2 shows the comparison between patients’ characteristics among BRCA mutant versus wild-type population.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients by BRCA mutation result

| Characteristic | All patients | BRCA 1 | BRCA 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutant | VUS | Mutant | VUS | ||

| N | 81 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 6 |

| Age at diagnosis | |||||

| Median | 41 | 33 | 40 | 34 | 46 |

| Range | 21–85 | 21–37 | 27–51 | 32–49 | 27–66 |

| Family history of breast cancer | |||||

| Yes | 45 (66.2%) | 3 (50%) | 6 (100%) | 2 (40%) | 4 (100%) |

| No | 23 (33.8%) | 3 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (60%) | 0 (0%) |

| Unknown | 13 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Histology | |||||

| IDC | 69 (85.2%) | 7 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 5 (100%) | 5 (83.3%) |

| ILC | 7 (8.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 5 (6.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| Histological grade | |||||

| I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| II | 58 (79.5%) | 1 (14.3%) | 4 (57.1%) | 3 (60%) | 6 (100%) |

| III | 15 (20.5%) | 6 (85.7%) | 3 (42.9%) | 2 (40%) | 0 (0%) |

| Stage | |||||

| 0 | 1 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 1 | 12 (33.3%) | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (40%) | 1 (50%) | 2 (40%) |

| 2 | 10 (27.8%) | 2 (66.7%) | 2 (40%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20%) |

| 3 | 4 (11.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (50%) | 0 (0%) |

| 4 | 9 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (40%) |

| ER | |||||

| Positive | 58 (71.6%) | 4 (57.1%) | 6 (85.7%) | 5 (100%) | 5 (83.3%) |

| Negative | 23 (28.4%) | 3 (42.9%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (16.7%) |

| PR | |||||

| Positive | 51 (63%) | 3 (42.9%) | 5 (71.4%) | 5 (100%) | 4 (66.7%) |

| Negative | 30 (37%) | 4 (57.1%) | 2 (28.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| HER2 | |||||

| Positive | 9 (11.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| Negative | 70 (88.6%) | 7 (100%) | 7 (100%) | 5 (100%) | 4 (66.7%) |

| Unknown | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtype | |||||

| Luminal A | 21 (25.9%) | 1 (14.3%) | 5 (71.4%) | 1 (20%) | 3 (50%) |

| Luminal B1 | 32 (39.5%) | 3 (42.9%) | 1 (14.3%) | 4 (80%) | 0 (0%) |

| Luminal B2 | 5 (6.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| HER2 enriched | 4 (4.9%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Triple negative | 19 (23.5%) | 3 (42.9%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (16.7%) |

IDC infiltrating ductal carcinoma, ILC infiltrating lobular carcinoma, ER estrogen receptor, PR progesterone receptor, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor-2, VUS variant of undetermined significance

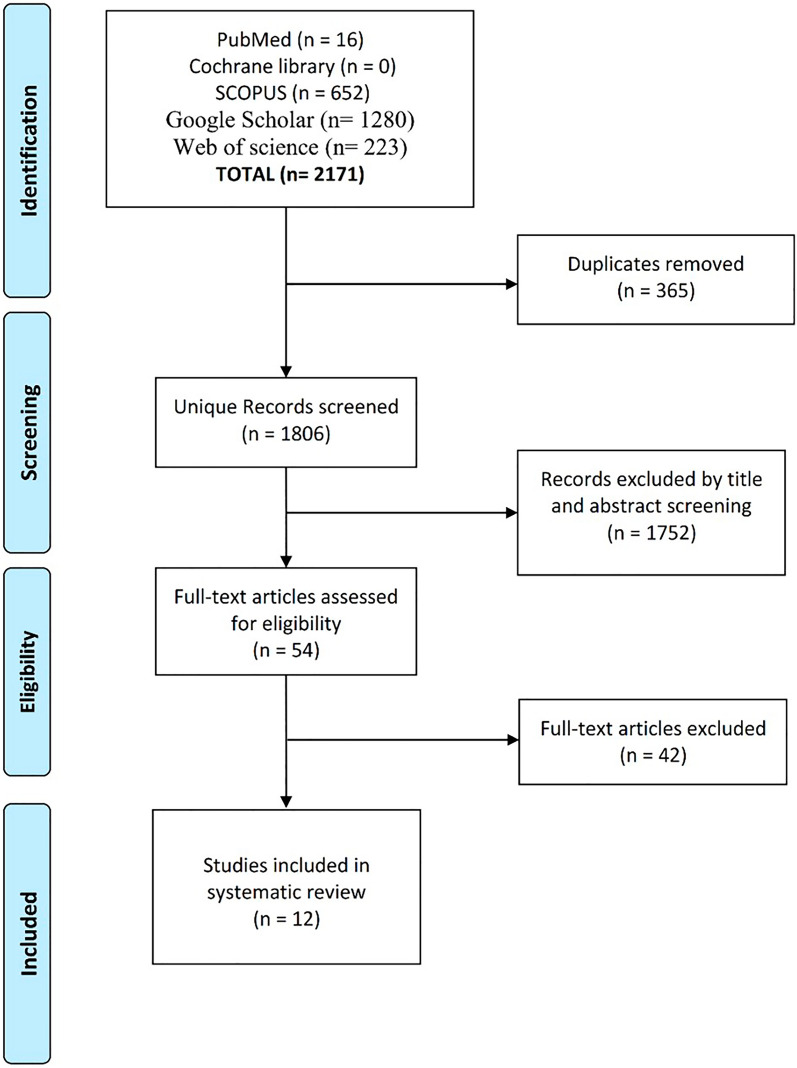

Summary of Characteristics of the Included Studies in the Systematic Review

A total of 1806 records were identified through the literature search. After the title and abstract screening, 54 articles underwent full-text screening. Finally, 12 published studies discussing BRCA1/2 mutational status among Egyptian women with BC were included in the current systematic review [10–13, 18–25], as shown in Fig. 1. The total number of women with BC included was 610 patients. Out of the 11 studies with documented age of diagnosis, the mean age ranged from 40 to 51 years, with eight studies reporting a median age below 45 years. Six studies tested for BRCA1 mutations only, one study tested for BRCA2 mutations only, and five studies tested for both BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Two of the studies which tested for BRCA1 only used Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) to detect large genomic rearrangements. Four studies applied DNA sequencing techniques in their detection methods (with only one of them confirming the identified mutations by using Sanger sequencing). The remaining studies used mutagenically separated PCR (MS-PCR), restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), or single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) methods. A summary of the included studies and used techniques is reported in Table 3.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart representing the process of screening and selection of eligible studies

Table 3.

Summary of included studies in the systematic review of literature

| Authors, year | Number of patients (number of controls if any) | Family history of BC | Mean age at diagnosis of BC (years) | Regions covered | Prevalence of mutation* | Detection platform | Ref. number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AbdelHamid et al., 2021 | 103 | 41/103 (39.8%) | 43 |

BRCA1 (exons 2, 20) BRCA2 (exons 9, 11) |

29/103 (28.2%) | HRM, sequencing | [17] |

| Abou-El-Naga et al., 2018 | 43 (154) | NA | 45.3 |

BRCA1 185delAG; 5382insC BRCA2 6174delT |

11/43 (25.6%) | MS-PCR | [18] |

| Eid et al., 2017 | 36 | NA | NA | BRCA1 LGR only | 0/36 (0%) | MLPA | [19] |

| Mogahed et al., 2020 | 80 (20) | 40/80 (50%) | 52 | BRCA1 185delAG; 5382insC | 5/80 (6.3%) | Pyrosequencing | [20] |

| Abdel-Mohsen et al., 2016 | 45 (30) | 19/45 (42.2%) | 51 | BRCA1 5382insC; 185delAG; c.181T>G | 44/45 (97.8%) | MS-PCR and PCR-RFLP | [12] |

| Abdel-Aziz et al., 2015 | 30 (20) | 15/30 (50%) | ≃ 45 | BRCA2 999del5; 6174delT | 7/30 (23.3%) | MS-PCR | [21] |

| Bensam et al., 2014 | 20 (40) | 13/20 (65%) | 46 |

BRCA1 185delAG; 624C>T (exon 8) BRCA2 999del5; 2256T>C (exon 11); 8934G>A (exon 21) |

8/20 (40%) | SSCP, heteroduplex analysis, Sequencing | [10] |

| Hagag et al., 2013 | 22 (4) | 22/22 (100%) | 45 | BRCA1 LGR only | 4/22 (18.2%) | MLPA | [22] |

| El-Debaky et al., 2011 | 30 (20) | 15 (50%) | ≃ 40 | BRCA1 185delAG; 5382insC; c.181T>G | 26/30 (86.7%) | MS-PCR | [23] |

| Hussein et al., 2011 | 100 (100) | 0/100 (0%) | 42 |

BRCA1 185delAG; 5382insC BRCA2 6174delT |

3/100 (3%) | MS-PCR | [11] |

| Ibrahim et al., 2010 | 60 (120) | 39/60 (65%) | 39.8 in BRCA mutant and 47.1 in non-mutant |

BRCA1 185delAG; 5454delC; 738C>A; 4446 C>T BRCA2 999del5 |

52/60 (86.7%) | SSCP, heteroduplex analysis, sequencing | [9] |

| Mahmoud et al., 2008 | 40 (90) | 15/40 (37.5%) | 25/40 (62.5%) younger than 40 years | BRCA1 185delAG | 4/40 (10%) | SSCP | [24] |

NA not available, MS-PCR mutagenically separated PCR, RFLP restriction fragment length polymorphism, SSCP single-strand conformation polymorphism, HRM high-resolution melting analysis

*This included only deleterious or protein-truncating mutations

The Pooled Prevalence of BRCA1/2 Mutations Among Egyptian Patients with Breast Cancer

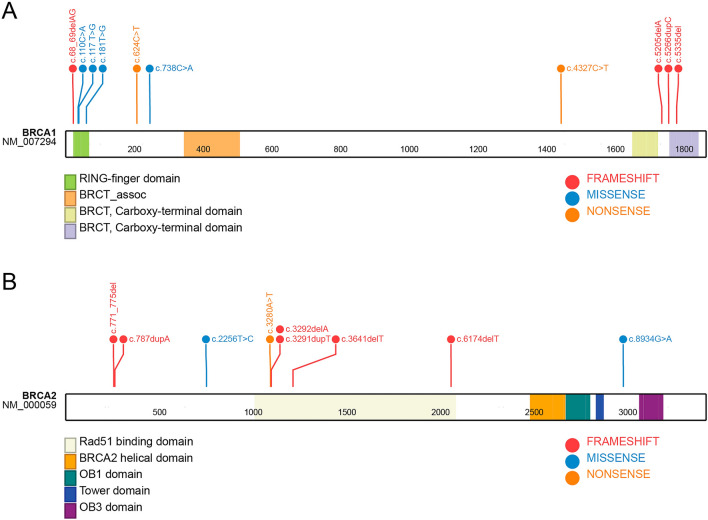

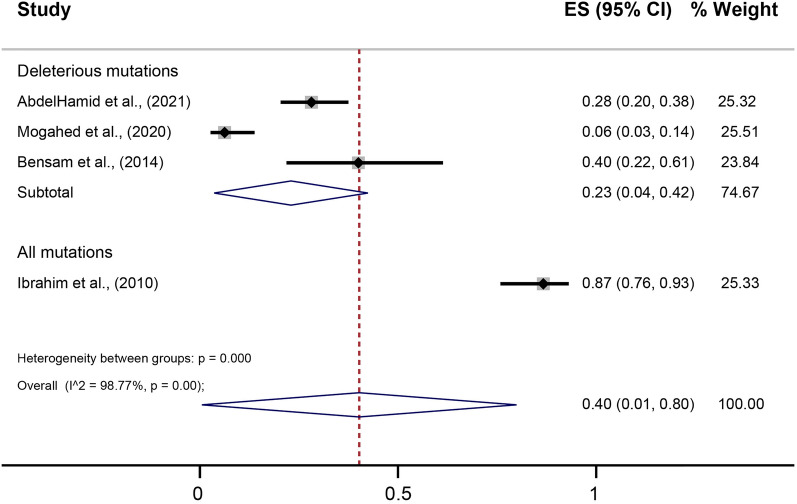

Among all the 12 studies, the reported prevalence widely ranged from 3% to 97.8% for BRCA1 mutations and from 0% to 26.7% for BRCA2 mutations (Table 3). A total of 19 deleterious mutations in BRCA1/2 were identified (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Materials). Among these, the most commonly studied mutations were the Ashkenazi Jews’ founder mutations 185delAG (in seven studies) and 5382insC (in four studies) for BRCA1, and the Icelanders’ founder mutations 999del5 (three studies) and 6174delT (in three studies) for BRCA2. In two-thirds of the included studies, more than 40% of the patients had a positive family history of BC. Different methodologies were used to evaluate gBRCA mutation. Out of the 12 evaluable studies, only four used gene sequencing with a pooled prevalence of 40% (95% CI 1–80%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Lollipops of BRCA1 (A) and BRCA2 (B) indicating the identified mutations and their type and position in women with breast cancer in the included studies from Egypt

Fig. 3.

Forest plot showing the pooled prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations using gene sequencing among Egyptian patients with breast cancer. CI confidence interval

Discussion

In our relatively high-risk patient cohort, we found the prevalence of BRCA1/2 deleterious mutations to be 14.8%, with an additional 16.1% having VUS in either gene. Patients with BRCA1/2 mutations were younger and more likely to be associated with higher Ki67 expression. Additionally, in our systematic review, we detected a relatively high prevalence of deleterious BRCA1/2 mutations in Egyptian patients with BC. To our knowledge, this is the largest and most comprehensive assessment of this topic.

The studies included in our systematic review suffered intrinsic limitations, including the small size of the individual studies and uncontrolled selection criteria for gBRCA testing. For instance, only five studies tested their patients for both BRCA1 and BRCA2, while the remaining studies tested for either BRCA1 or BRCA2. In addition, heterogeneity exists across them regarding family history, age, and how BRCA testing was evaluated. Gene sequencing was only performed in four studies. This explains the discrepancy in BRCA1/BRCA2 prevalence across studies. Another drawback is that only two studies reported the hormonal receptor status, yet gave no account of the intrinsic biological subtype [26].

Notably, most of the included studies did not undergo single analyses on every chromosomal region by real-time PCR or direct sequencing. Generally, mutation detection strategies dependent on PCR enrichment are associated with several limitations, such as potential overlapping primers [27, 28]. Moreover, all the studies were conducted in a research laboratory environment that lacked analytical and external validation regularly provided by clinical diagnostic labs. It is noteworthy that the current recommended platform for BRCA1 or BRCA2 germline testing in the clinical setting has to be through next-generation sequencing (NGS) [29]. This highlights the importance of our cohort study and other similarly needed studies in view of data scarcity.

Of major importance, two recent studies using NGS on peripheral blood have tried to look into the dilemma of breast cancer predisposition. In a study by Kim et al., using whole-exome sequencing of five Egyptian BC families showed a striking finding of no pathogenic variants neither in BRCA1, BRCA2, nor in other common BC predisposition genes [30]. However, damaging variants affecting other genes not involved in DNA repair were identified, although it is not clear if any of them could be considered as BC predisposition genes. This comprehensive analysis highlights the heterogeneity of the genomic structure of the Egyptian population [31]. On the other hand, another recent study by Nasssar et al., using targeted multi-gene DNA panel sequencing to detect mutations in several common genes associated with familial BC risk. The study that included 101 patients and 50 matched controls has found that 19.8% and 30.6% of them were BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers, respectively [32]. Such discrepancy in studies with good methodology highlights the need of larger prospective well-conducted studies.

Previous studies have explored the prevalence of BRCA1/2 mutations in Arab women with BC. Similar to our study, their main limitations were the small number of included patients and the uncontrolled selection criteria. Two studies could provide a glimpse of the whole picture [33, 34]. The first study is a cohort study from Lebanon that included 250 women with BC and considered at high risk of BRCA1/2 mutations based on age and family history [33]. The prevalence of pathogenic BRCA1/2 mutations was 5.6%. The majority of BRCA carriers were younger than 40 years with a positive family history. A second study was done on 100 Jordanian women with BC with a median age of 40 years. Twenty patients displayed deleterious mutations in BRCA1/2 genes. The highest mutation prevalence was observed among those with TNBC (56.3%) and even higher if they had a positive family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer (69.2%) [34]. Such high prevalence, which is close to some reports in our review, unlike the Lebanese study, could be due to the restriction of BRCA testing to high-risk cohorts in the Jordanian and some of the Egyptian studies. A meta-analysis of BRCA1/2 prevalence among the Arab population with hereditary breast/ovarian cancer suggested a 20% mutation rate, which decreased to 11% when limited to studies with a low risk of bias [35].

In the past decade, several therapeutic implications should be considered on the basis of germline genetic testing. So far, two PARP inhibitors (olaparib and talazoparib) are approved for treating patients with breast cancer based on the germline BRCA1/2 mutation status [3, 4]. In addition, patients with germline mutations who are diagnosed with breast cancer could be offered additional surgical options such as contralateral mastectomy or prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy that could improve the patient’s survival [36, 37]. This highlights the importance of the availability of genetic testing results on patients with BC outcomes.

In conclusion, available studies evaluating the prevalence of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in Egypt suffered major flaws. In our retrospective analysis in a rather selected population enriched with high-risk patients, we showed a prevalence of 40%. There is a need to further understand the true prevalence in the unselected population at a nationwide level and identify if other predisposition genes exist.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs Hussien Ahmed (MD) and Ahmed Salah Hussein (MD) from RAY-CRO, Egypt, for their valuable support throughout manuscript writing and editorial support for publication. Moreover, we would like to acknowledge insightful input from Dr. Elaria Yacoub (Department of Surgery, Cairo University).

Author Contributions

Hamdy A. Azim contributed to developing the study concept, study design, literature search, data collection, and revision of the manuscript. Samah Aly Loutfy contributed to developing the study concept, study design, literature search, data collection, and revision of the manuscript. Hatem A. Azim Jr contributed to the study design, data collection, and manuscript writing. Nermin S. Kamal contributed to the study design, data collection, and manuscript writing. Nasra Fathy Abdel Fattah contributed to the study design, data collection, and revision of the manuscript. Mostafa H. Elberry contributed to the literature search, data collection, and revision of the manuscript. Mohamed Refaat Abdelaziz contributed to the literature search and revision of the manuscript. Marwa Abdelsalam contributed to the literature search, data collection, and manuscript writing. Madonna Aziz contributed to the literature search, data collection, and manuscript writing. Kyrillus S. Shohdy contributed to the literature search, data collection, and manuscript wiring. Loay Kassem contributed to the study design, data collection, and manuscript writing. All authors have read and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no funds during the preparation and conduction of this research. The medical writing and editorial support, including verification of all the systematic review steps according to PRISMA guidelines, were provided by RAY-CRO, which received a limited grant from Pfizer—Egypt. They were not involved in any further steps of the study, including the retrospective study on patients’ data. No funding or sponsorship was received for the publication of this article.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

All patients in the Cairo Oncology Center signed informed consent before germline testing. The Local COC Institutional Review Board (2019020501) have exempted retrospective analyses that does not involve personal patient data from further consents or approvals.

Conflict of Interest

Hamdy A. Azim, Samah A. Loutfy, Hatem A. Azim Jr, Nermin S. Kamal, Nasra F. Abdel Fattah, Mostafa H. Elberry, Mohamed R. Abdelaziz, Marwa Abdelsalam, Madonna Aziz, Kyrillus S. Shohdy, and Loay Kassem have no related financial connections to declare.

Footnotes

Hamdy A. Azim and Samah A. Loutfy contributed equally.

References

- 1.Stratton M, Rahman N. The emerging landscape of breast cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2008;40(1):17–22. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tai YC, Domchek S, Parmigiani G, Chen S. Breast cancer risk among male BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(23):1811. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tutt ANJ, Garber JE, Kaufman B, Viale G, Fumagalli D, Rastogi P, et al. Adjuvant olaparib for patients with BRCA1- or BRCA2-mutated breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(25):2394–2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Litton JK, Rugo HS, Ettl J, Hurvitz SA, Gonçalves A, Lee KH, et al. Talazoparib in patients with advanced breast cancer and a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(8):753–763. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robson M, Im SA, Senkus E, Xu B, Domchek SM, Masuda N, et al. Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(6):523–533. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstrong N, Ryder S, Forbes C, Ross J, Quek R. A systematic review of the international prevalence of BRCA mutation in breast cancer. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:543–561. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S206949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferla R, Calò V, Cascio S, Rinaldi G, Badalamenti G, Carreca I, et al. Founder mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(Suppl 6):vi93–vi98. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azim HA, Ibrahim AS. Breast cancer in Egypt, China and Chinese: statistics and beyond. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(7):864. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.06.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Najjar H, Easson A. Age at diagnosis of breast cancer in Arab nations. Int J Surg. 2010;8(6):448–452. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibrahim SS, Hafez EE, Hashishe MM. Presymptomatic breast cancer in Egypt: role of BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumor suppressor genes mutations detection. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2010;29:82. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-29-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bensam M, Hafez E, Awad DMES, Balbaa M. Detection of new point mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in breast cancer patients. Biochem Genet. 2014;52(1–2):15–28. doi: 10.1007/s10528-013-9623-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussien YM, Gharib AF, Ibrahim HM, Abdel-Ghany ME, Elsawy WH. Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in eastern Egyptian breast cancer patients. Bull Egypt Soc Physiol Sci. 2011;31(1):107. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdel-Mohsen M, Ahmed O, El-Kerm Y. BRCA1 gene mutations and influence of chemotherapy on autophagy and apoptotic mechanisms in Egyptian breast cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(3):1285–1292. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.3.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kemp Z, Turnbull A, Yost S, Seal S, Mahamdallie S, Poyastro-Pearson E, et al. Evaluation of cancer-based criteria for use in mainstream BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing in patients with breast cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e194428. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trujillano D, Weiss MER, Schneider J, Köster J, Papachristos EB, Saviouk V, et al. Next-generation sequencing of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes for the genetic diagnostics of hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer. J Mol Diagn. 2015;17(2):162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. Br Med J. 2015;2(349):g7647–g7647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Heal. 2014;72(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Debaky F, Azab N, Alhusseini N, Eliwa S, Musalam H. Breast Cancer Gene 1 (Brca 1) mutation in female patients with or without family history in Qalubia Governorate. J Am Sci. 2011;7(2):82–93. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahmoud N, Moustafa A, Mahrous H, El-Gezeery A, Mahmoud H, Abd E-M. BRCA1 (185delAG) mutation among Egyptian breast cancer female patients. J High Inst Public Heal. 2008;38(2):409–424. doi: 10.21608/jhiph.2008.20895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.AbdelHamid S, Zekri A, AbdelAziz H, El-Mesallamy H. BRCA1 and BRCA2 truncating mutations and variants of unknown significance in Egyptian female breast cancer patients. Clin Chim Acta. 2021;512:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abou-El-Naga A, Shaban A, Ghazy H, Elsaid A, Elshazli R, Settin A. Frequency of BRCA1 (185delAG and 5382insC) and BRCA2 (6174delT) mutations in Egyptian women with breast cancer compared to healthy controls. Meta Gene. 2018;15:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.mgene.2017.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eid OM, El Ghoroury EA, Eid MM, Mahrous RM, Abdelhamid MI, Aboafya ZI, et al. Evaluation of BRCA1 large genomic rearrangements in group of Egyptian Female Breast cancer patients using MLPA. Gulf J Oncol. 2017;1:64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mogahed S, Hamed Y, Moursy Y, Saied M. Analysis of heterozygous BRCA1 5382ins founder mutation in a cohort of Egyptian breast cancer female patients using pyrosequencing technique. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020;21(2):431–438. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.2.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdel-Aziz T, Azab N, Emara NM, Odah MM, El-Deen I. Study of BRCA2 gene mutations in Egyptian females with breast cancer. Int J Innov Res Sci Eng Technol. 2007;3297(2):14. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hagag E, Shwaireb M, Coffa J, El WA. Screening for BRCA1 large genomic rearrangements in female Egyptian hereditary breast cancer patients. East Mediterr Heal J. 2013;19(3):256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perou CM, Sørlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406(6797):747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellison G, Wallace A, Kohlmann A, Patton S. A comparative study of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation screening methods in use in 20 European clinical diagnostic laboratories. Br J Cancer. 2017;117(5):710. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frayling IM. Methods of molecular analysis: mutation detection in solid tumours. Mol Pathol. 2002;55(2):73. doi: 10.1136/mp.55.2.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Deiry W, Goldberg R, Lenz H, Shields A, Gibney G, Tan A, et al. The current state of molecular testing in the treatment of patients with solid tumors, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(4):305–343. doi: 10.3322/caac.21560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim Y, Soliman A, Cui J, Ramadan M, Hablas A, Abouelhoda M, et al. Unique features of germline variation in five Egyptian familial breast cancer families revealed by exome sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0167581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pagani L, Schiffels S, Gurdasani D, Danecek P, Scally A, Chen Y, et al. Tracing the route of modern humans out of Africa by using 225 human genome sequences from Ethiopians and Egyptians. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(6):986. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nassar A, Zekri ARN, Kamel MM, Elberry MH, Lotfy MM, Seadawy MG, et al. Frequency of pathogenic germline mutations in early and late onset familial breast cancer patients using multi-gene panel sequencing: an Egyptian study. Genes (Basel) 2022;14(1):106. doi: 10.3390/genes14010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El SNS, Zgheib NK, Assi HA, Khoury KE, Bidet Y, Jaber SM, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in ethnic Lebanese Arab women with high hereditary risk breast cancer. Oncologist. 2015;20(4):357. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdel-Razeq H, Al-Omari A, Zahran F, Arun B. Germline BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations among high risk breast cancer patients in Jordan. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):1–1. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdulrashid K, AlHussaini N, Ahmed W, Thalib L. Prevalence of BRCA mutations among hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer patients in Arab countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5463-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boughey JC, Attai DJ, Chen SL, Cody HS, Dietz JR, Feldman SM, et al. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM) consensus statement from the American Society of Breast Surgeons: data on CPM outcomes and risks. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(10):3100–3105. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5443-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berek JS, Chalas E, Edelson M, Moore DH, Burke WM, Cliby WA, et al. Prophylactic and risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(3):733–743. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ec5fc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.