Abstract

Graphitic carbon nitride is widely studied in organic photoredox catalysis. Reductive quenching of carbon nitride excited state is postulated in many photocatalytic transformations. However, the reactivity of this species in the turn over step is less explored. In this work, we investigate electron and proton transfer from carbon nitride that is photocharged to a various extent, while the negative charge is compensated either by protons or ammonium cations. Strong stabilization of electrons by ammonium cations makes proton-coupled electron transfer uphill, and affords air-stable persistent carbon nitride radicals. In carbon nitrides, which are photocharged to a smaller extent, protons do not stabilize electrons, which results in spontaneous charge transfer to oxidants. Facile proton-coupled electron transfer is a key step in the photocatalytic oxidative-reductive cascade – tetramerization of benzylic amines. The feasibility of proton-coupled electron transfer is modulated by adjusting the extent of carbon nitride photocharging, type of counterion and temperature.

Subject terms: Photocatalysis, Photocatalysis, Physical chemistry

Savateev et al. investigate proton-coupled electron transfer from persistent graphitic carbon nitride radical to oxygen and imines. The results of their study find application in cascade photocatalysis – selective tetramerization of benzylic amines.

Introduction

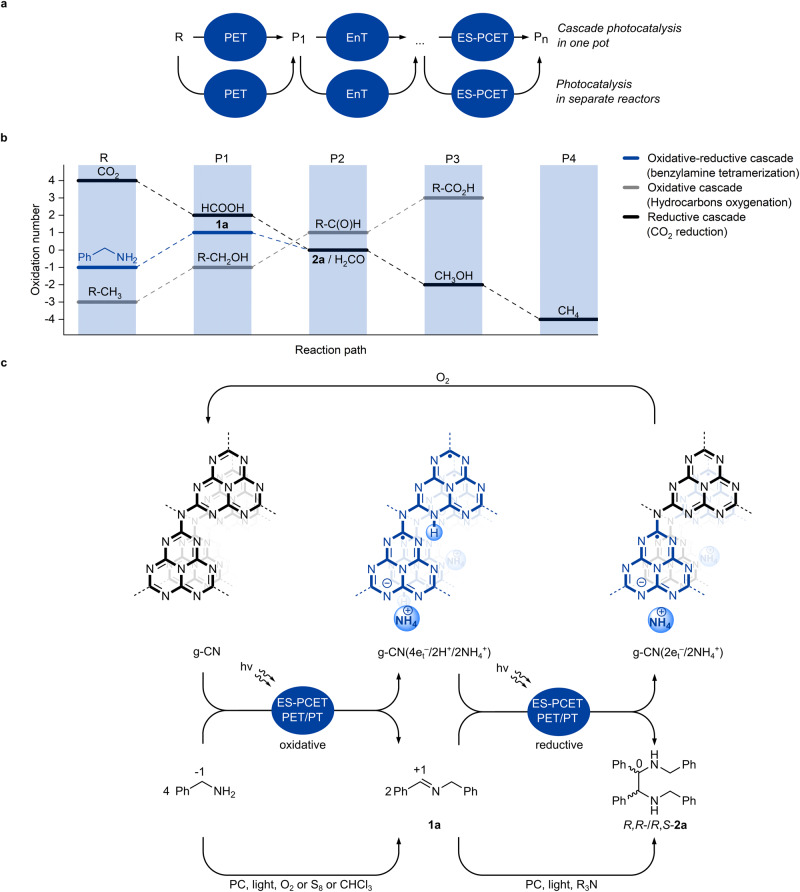

Photocatalysis utilizes electromagnetic radiation in the UV-vis range of the electromagnetic spectrum to overcome an activation energy barrier and to drive uphill reactions. Among many possibilities for classification, photocatalytic processes may be divided into (i) those that are enabled by a single photon—a mechanism includes a single photocatalytic event, and (ii) those that include at least two photocatalytic events, such as combination of photoinduced electron transfer (PET), excited state proton-coupled electron transfer (ES-PCET)1 or direct hydrogen atom transfer (dHAT)2 and/or energy transfer (EnT)3 (Fig. 1a). In cascade photocatalysis, it is not always possible to unambiguously confirm if a second photon is involved4. However, once a thermodynamically stable closed-shell and electrically-neutral compound in the ground state is formed, a subsequent photocatalytic event is required to activate such a compound. There are already plenty examples of cascade processes mediated by molecular photocatalysts, such as (−)-Riboflavin5, thioxanthen-9-one6, Ir-polypyridine complexes7,8, Eosin Y9, [Mes-Acr]+ClO4‒10, which involve either two sequential EnT events6–8, two PET events9,10, or a combination of EnT/PET events in the first and second steps5. In semiconductor photocatalysis, a rather well-studied oxidative photocatalytic cascade hydrocarbon-alcohol-aldehyde-carboxylic acid proceeds via combination of ES-PCET (dHAT) and/or PET events10. A process such as CO2‒HCOOH‒H2CO‒CH3OH‒CH4 proceeds via a formaldehyde pathway and a combination of PET and/or ES-PCET (dHAT) events11.

Fig. 1. Cascade photochemical processes.

a Schematic representation of a cascade photocatalysis in one pot and each photocatalytic reaction performed in separate reactors. PET—photoinduced electron transfer. EnT—energy transfer. ES-PCET—excited state proton-coupled electron transfer. b Change of the formal oxidation number of the reaction site in cascade processes. R—reagent. P1–4,Pn—product 1–4, n. c An oxidative-reductive cascade process that is based on the transfer of electrons and protons and illustrated by tetramerization of benzylamine. et‒—trapped electron, H+—proton, PC—photocatalyst, PT—proton transfer.

The chemical structure of reagents and reactions in the above examples are indeed very different (Figure S1). In order to analyze them collectively, in Fig. 1b the change of the formal oxidation number of the atom at the reaction site is plotted along the reaction coordinate. While in redox neutral cascades, in particular those that proceed exclusively via EnT, formal oxidation number does not change6–8, in oxidative cascades—increases9,10, and in reductive—decreases11. Such an observation stems from the fact that it is challenging to switch between, for instance, oxidative (typically in the presence O2) to reductive conditions (in the presence of tertiary amines) and vice versa in the same cascade. The principle used to create Fig. 1b outlines a type of cascade processes, which demonstrates a maximum or a minimum on the plot and is referred to as an oxidative-reductive cascade. Such cascades are based on the transfer of atoms, among which the most ubiquitous is hydrogen.

Tetramerization of benzylic amines is an example of a cascade process. Individual steps were reported separately (Fig. 1c). Photocatalytic coupling of benzylamine to imine requires oxidants, O212, S813, or CHCl314. On the other hand, aza-pinacol coupling of imines under reductive conditions is mediated by CdS15, IrIII-polypyridine complexes16, and transition metal free organic dyes, such as diphenyldibenzocarbazole17, N-phenylphenothiazine18 and perylene19.

One of the greatest advantages of cascade photocatalysis is that it merges several reactions into a single process, which overall is more resource-efficient. In order to implement a photochemical oxidative-reductive cascade process, such as tetramerization of benzylamine, a semiconductor, exemplified by heptazine-based graphitic carbon nitride (g-CN) in Fig. 1c, must first enable an oxidative event and at the same time temporarily store one equivalent of electron/proton couples, et‒/H+. The subscript stands for ‘trapped’ electrons to emphasize that the potential of such electrons is different from that of the photogenerated "hot" electrons. Secondly, the photocharged semiconductor must bind et‒/H+ only weakly in order to transfer them to the imine in the second step. By contrast strong binding of et‒/H+ would terminate the cascade process at imine 1a. Given that a semiconductor is required in a quasi-stoichiometric quantity versus benzylamine to store temporarily an equimolar amount of et‒/H+ pairs, we deliberately omit the term ‘catalysis’, but refer to benzylamine tetramerization as a ‘cascade process’. Nevertheless, a photocharged semiconductor may be recovered upon exposure to O2 or other oxidant.

In this work, benzylamine tetramerization that is enabled by g-CNs, such as mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride (mpg-CN), sodium poly(heptazine imide) (Na-PHI), and visible light, is chosen as a model oxidative-reductive cascade process. The objectives of the present study are: (1) identify preferential facets of g-CN materials at which charge-compensating cations are stored; (2) investigate the influence of the nature of charge-compensating cations, H+ vs. NH4+, on reactivity of et‒; (3) establish the role of micro- and meso-porosity in storage of electrons and charge-compensating cations.

Results

Tetramerization of benzylamine

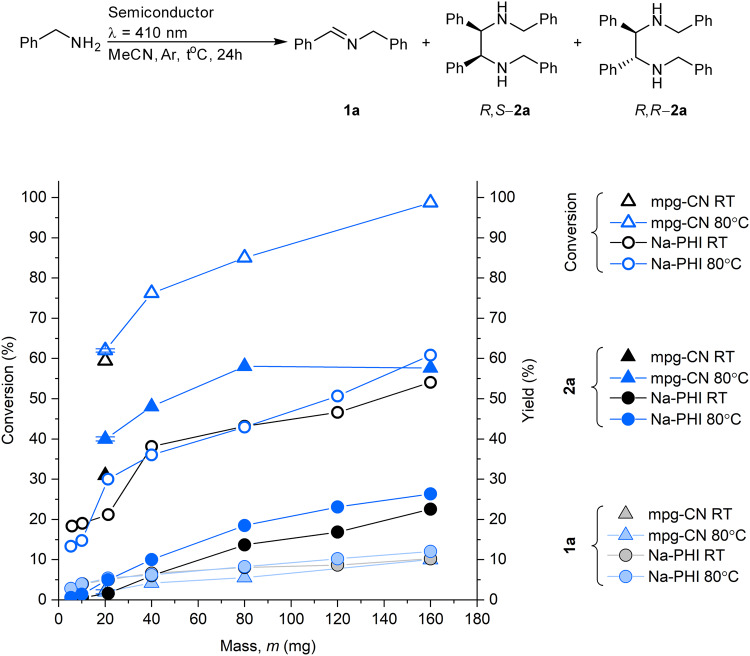

Illumination of a thoroughly degassed mixture of benzylamine and a semiconductor (g-CN, TiO2, CdS) in MeCN with photons of suitable wavelength to ensure electron excitation across the band gap gave imine 1a and a mixture of diastereomers R,S-2a and R,R-2a. The diastereometric ratio (d.r.) was determined from 1H NMR spectra of the reaction mixture20. While the full data set is given in Supplementary Table 1, we comment on general trends. Conversion of benzylamine, the yield of 1a and the combined yield of R,S- and R,R-2a diastereomers versus the mass of carbon nitride semiconductor, Na-PHI and mpg-CN, are plotted in Fig. 2. In most cases, after 24 h 2a was the major product, indicating the feasibility of temporary storage of hydrogen in semiconductors and transfer to the imine 1a. In the experiments with the same mass of semiconductor, mpg-CN-8nm-193 (average pore diameter 8 nm and SSA = 193 m2 g−1), gave higher conversion and yield when the reaction was conducted at 80 °C compared to room temperature and compared to Na-PHI (specific surface area, SSA, 1 m2 g−1). The extent of conversion depends on (i) the amount of Na-PHI and mpg-CN-8nm-193 and (ii) surface area of the semiconductor (Supplementary Discussion 1). For mpg-CN-8nm-193, complete conversion was achieved at 160 mg of the semiconductor, while for Na-PHI complete conversion was not achieved. In all experiments, the yield of R,S- and R,R-2a remained below 60%. H-PHI, obtained from Na-PHI upon Na+ exchange with protons21, gave R,S-2a and R,R-2a in significantly lower combined yield, 8% (entry 31, Supplementary Table 1). Control experiments confirmed that mpg-CN and anaerobic conditions were essential to obtain 2a (Supplementary Table 2). The presence of O2 terminated the cascade process at the first step—1a was obtained in 28 ± 2% yield and 2a did not form. Benzylamine was converted to neither 1a nor 2a in the absence of a semiconductor and in the dark. Overall, benzylic amines ring-substituted with fluorine atoms and CF3-groups also give ethanediamines. On the other hand, in the case of benzylic amines carrying electron-donating groups in the aromatic ring and sterically encumbered 1-phenylethanamine, the cascade process is terminated at the step of the corresponding imine synthesis.

Fig. 2. Dependence of benzylamine conversion and yield of imine 1a, R,S- and R,R-2a on mass of semiconductors and reaction temperature.

Filled symbols correspond to yield, empty—to conversion. Gray/black colors correspond to experiments conducted at room temperature (RT), blue—at 80 °C. Conditions: benzylamine (0.2 mmol), MeCN (2 mL), Ar, 24 h, light 410 nm (39 ± 8 mW cm-2). Error bars denote standard deviation (n = 3, experiments conducted in parallel). Source data are provided as a Source data file.

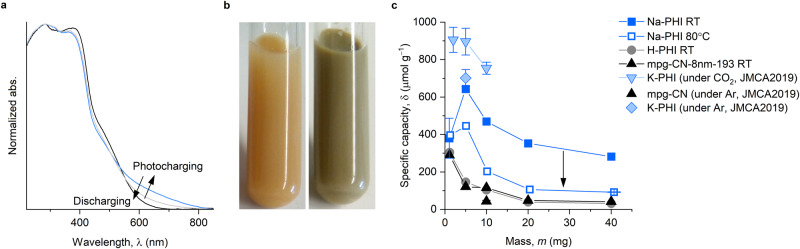

After illumination was stopped and before exposure of the reaction mixture to air all semiconductors underwent an obvious color change, which is attributed to the accumulation of electrons22. Among carbon nitrides, the most pronounced color change is observed for PHIs23. In the DRUV-vis spectra (Fig. 3a, b) mpg-CN shows an absorption band that stretches up to 800 nm in addition to widening of the band gap by ~10 nm (8 meV) attributed to the Moss-Burstein shift—blue-shift of the onset of absorption at ~450 nm. In a series of parallel experiments performed under the conditions identical to that in Fig. 2, the specific concentrations of electrons, δ, in Na-PHI (SSA = 1 m2 g−1) and mpg-CN was determined by quenching the reaction mixture with methyl viologen bis(hexachlorophosphate), MV2+ 2PF6‒ (reduction Ep1/2 = ‒0.45 V vs. SCE in MeCN, Fig. 3c, Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). While the concentration of benzylamine in the reaction mixture was kept the same, we observed in all cases a strong dependence of δ on the mass of the semiconductor taken for the experiment (Supplementary Discussion 2). The higher the excess of benzylamine per carbon nitride mass, the larger is δ. Ionic carbon nitride, Na-PHI, accumulates a 3‒7 times higher number of electrons per mass unit compared to mpg-CN. Although using a slightly different concentration of benzylamine, 0.1 M herein versus 0.05 M used earlier24, δ measured for Na-PHI is comparable to that of K-PHI (m = 5 mg). H-PHI shows values comparable to mpg-CN δ, obtained for the same mass of the material, which illustrates a transition from an ionic structure in Na-PHI to covalent as in mpg-CN upon substitution of Na+ with protons. Coupling of two benzylamine molecules is accompanied by the formation of NH4+. Substitution of H+ by alkali metal ion occurs in aqueous environment at pH > 721,25,26. Benzylamine tetramerization was conducted in less polar solvent, MeCN, without adjusting the pH. Therefore, we speculate that under such conditions spontaneous H+-to-NH4+ ion exchange in H-PHI does not occur. However, given that NH4+ serves as the counter ion to the stored electron (see below), such ion exchange might proceed via material photocharging. Na-PHI shows systematically lower δ values, when photocharging is conducted at 80 °C suggesting that it is an endergonic process (see the results of DFT calculations below and Supplementary Discussion 3). By correlating δ values (Fig. 3c) with Na content in Na-PHI that was recovered from benzylamine tetramerization reaction mixture (Fig. 2), we found that storage of one electron in the material is accompanied by extraction of 7 and 25 Na+ ions when the reaction is conducted at room temperature and 80 °C (Supplementary Discussion 4).

Fig. 3. Photocharging of g-CN semiconductors.

a UV-vis absorption spectra of mpg-CN dispersion in iPr2NEt (0.1 M) solution in MeCN prior to irradiation with light (black), after irradiation (blue) and after exposure of photocharged mpg-CN to air (gray). Source data are provided as a Source data file. b Photographs of the reaction mixture (mpg-CN-8nm-193 20 mg) before light irradiation and after irradiation at 465 nm for 24 h before exposure to air. c Dependence of δ (avg ± std, n = 3) on mass of the semiconductor photocharged at room temperature (RT) and 80 °C. Deviation of the data point (avg ± std, n = 5) obtained for Na-PHI (1 mg) from the trend is due to low optical density of the reaction mixture. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

Aza-pinacol coupling of imine 1a

In order to study only a second step of the cascade reaction, we used imine 1a as the substrate and extended the scope of carbon nitride semiconductors to mpg-CN-6nm-204 and mpg-CN-17nm-171 having the average pore diameters of 6 and 17 nm and SSA of 204 and 171 m2 g−1, respectively. NH4COOH and tertiary amines, Me3N, Et3N, iPr2NEt, nBu3N, and nOct3N, were used as the source of electrons and protons to generate the α-aminoalkyl radical from the imine 1a. While a full dataset is given in Supplementary Tables 5–12, below we highlight some of our results (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected conditions of aza-pinacol coupling screeninga

| Entry | SC | Mass (mg) | SED | Conversion of 1ab (%) | Combined yield of R,S-2a and R,R-2ac (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1d | mpg-CN-8nm-193 | 5 | iPr2NEt | 94 | 77 (1:0.54) |

| 2d | mpg-CN-8nm-193 | 20 | iPr2NEt | 100 | 68 (1:0.29) |

| 3d | mpg-CN-8nm-193 | 20 | Et3N | 98 | 65 (1:0.77) |

| 4d | mpg-CN-8nm-193 | 20 | NH4COOH | 26 | 16 (1:0.60) |

| 5d,e | mpg-CN-8nm-193 | 20 | NH4COOH | 44 | 4 (1:0.29) |

| 6f | Na-PHI | 20 | iPr2NEt | 46 | 46 (1:0.84) |

| 7f | Na-PHI | 20 | NH4COOH | 83 | 61 (1:0.83) |

| 8f,e | Na-PHI | 20 | NH4COOH | 61 | 33 (1:0.50) |

| 9f | H-PHI | 20 | iPr2NEt | 66 | 47 (1:0.48) |

| 10f | H-PHI | 20 | NH4COOH | 98 | 74 (1:0.61) |

| 11d,g | mpg-CN-8nm-193 | 20 | iPr2NEt | 99 | 67 (1:0.28) |

| 12d,h | mpg-CN-8nm-193 | 20 | iPr2NEt | 97 | 77 (1:0.46) |

| 13i | mpg-CN-8nm-193 | 20 | Et3N | 0 | 0 (‒) |

| 14i,j | mpg-CN-8nm-193 | 20 | Et3N | 0 | 0 (‒) |

| 15d | ‒ | ‒ | iPr2NEt | 0 | 0 (‒) |

| 16d | mpg-CN-8nm-193 | 20 | – | 0 | 0 (‒) |

aConditions: 1a (0.1 mmol), semiconductor, SED (0.2 mmol), MeCN (2 mL), light, 25 ± 5 °C, 24 h.

bYield and d.r. were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard.

cRatio between R,S-2a and R,R-2a isomers is given in parentheses.

d465 nm, 10 ± 2 mW cm−2.

eReaction in MeCN/water (3:1) mixture (2 mL).

f410 nm, 39 ± 8 mW cm−2.

gWithout reaction mixture degassing.

hWithout reaction mixture degassing, water (10 equiv.) was added.

iIn the dark.

jAt 50 °C.

Aza-pinacol coupling proceeds efficiently using only 5 mg of mpg-CN-8nm-193 (Table 1, entry 1), which enables us to call this second step of the cascade process as catalytic. It also confirms earlier findings using other classes of photoredox catalysts15–19. However, most of the screening experimental conditions were performed with 20 mg of semiconductors in order to correlate the results of the first and the second step of the cascade process. Combination of mpg-CN with either iPr2NEt (entry 2), Et3N (entry 3) or nBu3N (Supplementary Table 6, entry 4) gave R,S- and R,R-2a in a combined yield 65–68%. Using NH4COOH in anhydrous MeCN and MeCN/water (3:1 vol.) gave 2a with 16 and 4% yield, respectively, while conversion of 1a remained low (entries 4,5). With tertiary amines, Na-PHI gave 2a with lower yield, 46% (entry 6). However, when NH4COOH in anhydrous MeCN or MeCN/water (3:1 vol.) was employed, the yield of 2a increased to 61% and 33%, respectively (entries 7, 8). A similar trend was observed for H-PHI (entries 9, 10). Although ionic character was lost upon washing with HCl, in aza-pinacol coupling, due to the microporous structure, performance of H-PHI was similar to Na-PHI. Synthetic robustness of the method was supported by the fact that the reaction proceeded without thorough degassing of the reaction mixture because dissolved O2 was consumed at the beginning of the reaction (entries 11, 12). Aza-pinacol coupling did not proceed without a semiconductor, electron donor and/or light irradiation (entries 13–16).

By performing aza-pinacol coupling of 1a in CD3CN over various semiconductors, we found that Et3N or nBu3N were converted into diethylamine and dibutylamine along with the corresponding aldehydes fragmented from the tertiary amines (Supplementary Tables 13, 14). This observation supports the postulated earlier mechanism of tertiary amines, (RCH2)3N, oxidation that proceeds via formation of the intermediary iminium cation followed by hydrolysis to (RCH2)2NH and RC(O)H by trace amounts of water present in the solvent27–29.

Similar to benzylamine tetramerization, all semiconductors undergo photocharging. To check whether electrons stored in photocharged carbon nitrides are sufficiently reductive to enable aza-pinacol coupling of imine 1a in the dark, a suspension of mpg-CN or Na-PHI and Et3N in MeCN was irradiated with light for 24 h. After addition of imine 1a to the photocharged carbon nitride semiconductors the mixture was stirred either at room temperature or at 80 °C in the dark for 24 h (Supplementary Table 15). In these experiments, we did not obtain 2a, but detected a small amount of dibenzylamine, which suggests transfer of 2e‒ to the imine 1a in a single kinetic step.

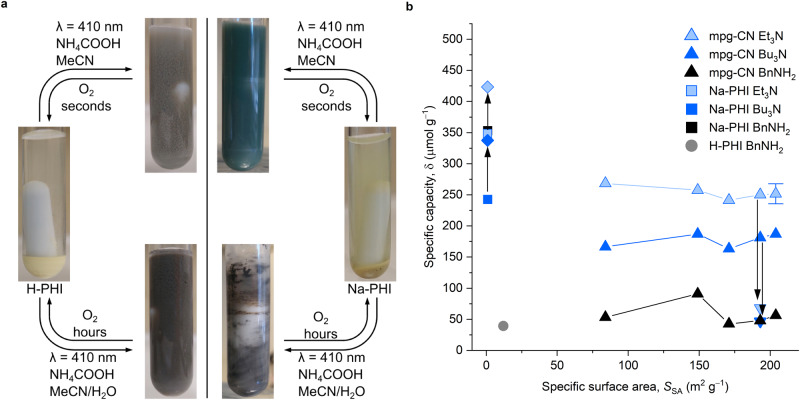

Upon exposure of photocharged semiconductors to air, coloration vanished within seconds in all cases except Na-PHI and H-PHI that were photocharged with NH4COOH in aqueous MeCN solution—it required hours to recover the pristine yellow color of the semiconductors (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Discussion 5). Although we have been using quite extensively PHIs in photocatalysis under reductive conditions, we have never observed such long-lived species in air.

Fig. 4. Photocharging of g-CN semiconductors.

a Images of H-PHI and Na-PHI photocharged in MeCN and MeCN/H2O (2:1 vol.) and their stability in air. b Dependence of δ (avg ± std, n = 3) on SSA of mpg-CN semiconductors determined by quenching with MV2+ 2PF6‒. Conditions: semiconductor (20 mg), amine (0.2 mmol), MeCN (2 mL), 25 ± 5°, 24 h, 465 nm (10 ± 2 mW cm−2, mpg-CN) or 410 nm (39 ± 8 mW cm−2, Na-PHI). Arrows indicate shift of data points when photocharging was conducted in the presence of NH4PF6. Source data are provided as a Source data file.

The exceptionally high stability of PHIs photocharged in aqueous NH4COOH must be due to a synergy of several factors. Firstly, the formate anion30 is a much stronger reductant compared to benzylamine24, tertiary amines, and benzylic alcohols23,31, due to its lower oxidation potential and the irreversible injection of an electron into the photoexcited PHI upon concomitant evolution of CO2. Secondly, an aqueous environment is likely to facilitate transport of formate anions through Na-PHI micropores into the bulk of the material. Therefore, a higher density of electrons in photocharged Na-PHI is achieved, which is reflected in a broader absorption—the material appears black (Supplementary Discussion 6), instead of blue or the ones having a green tint32. In a series, H+ <NH4+ solvated by MeCN <hydrated NH4+, the last must be the most thermodynamically stable species. Oxidation of photocharged Na-PHI implies extraction of not only electrons from the material, but also charge-compensating cations. Although higher δ values may be achieved by performing photocharging in the presence of ammonium salts in anhydrous MeCN (see below), in aqueous medium, the electrons stored in Na-PHI are less reactive toward O2. Stronger stabilization of electrons by hydrated NH4+ compared to H+ explains the lower yield of 2a when Na-PHI was employed in aqueous NH4COOH solution (entry 7 vs. 8 in Table 1)—PCET becomes more challenging.

To complement the results of carbon nitrides photocharging with benzylamine (Fig. 1c), we extended the scope of electron donors to tertiary amines (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table 4). Higher δ values were obtained for g-CNs featuring micropores, Na-PHI and H-PHI, compared to mpg-CN, which possesses mesopores. Surprisingly, δ does not depend on the SSA of mpg-CN. Assuming that mpg-CN has the structure of melon-type g-CN33 and stores e‒/H+ only on the surface, the obtained δ values are translated into one electron per 1…30 heptazine units (Supplementary Table 16, Supplementary Discussion 7). In other words, even in mpg-CN with a SSA as low as 84 m2 g−1 the storage of e‒/H+ only on the surface is feasible and the surface is not saturated with e‒/H+. Higher δ values were obtained for Et3N and nBu3N compared to benzylamine, which is a result of different pathways of electron donor oxidation. Coupling of two benzylamine molecules to 1a is accompanied by formation of NH4+, which serves as a counter ion in the photocharged carbon nitride. NH4+ stabilize electrons in mpg-CN more efficiently compared to H+, which results in significantly slower rate of MV2+ 2PF6‒ reduction. Indeed, when photocharging of mpg-CN was conducted in the presence of R3N and NH4PF6 (anhydrous conditions) we obtained δ values comparable to that of benzylamine. However, addition of NH4+ in Na-PHI photocharging experiment resulted in 21–39% higher δ values, which confirms that only in anhydrous NH4+-based electrolytes, Na-PHI accumulates a larger number of sufficiently reductive electrons.

However, it is still surprising that although tertiary amines have very similar oxidation potentials (Ep1/2 = +0.68 and +0.72 V vs SCE in MeCN, Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Discussion 8), δ values for mpg-CN and Na-PHI obtained in Et3N are 40% higher compared to the reaction in nBu3N. Such an observation suggests that in mpg-CN electrons and charge-compensating H+ remain localized at the sites where amine oxidation takes place, and they do not equilibrate on the timescale of semiconductor’s photocharging followed by quenching with MV2+ 2PF6‒, i.e., several hours. Due to the larger diameter of nBu3N compared to Et3N, the corresponding iminium cation can ‘shield’ larger areas of carbon nitride from the interaction with electron donor molecules. Given the graphitic-like structure of carbon nitrides with the spacing between the layers of ~0.33 nm, sorption of iminium cations must have the most pronounced effect when occurs at the edge plane (Supplementary Table 17). Taking into account the van der Waals cross-section of the iminium cations derived from Et3N and nBu3N of 0.30 and 0.44 nm2, respectively, each of them can cover between 0.4–0.9 heptazine units when sorption occurs at the basal plane, but 0.7–2.2 heptazine units—at the edge plane (see SI for calculation details and Supplementary Fig. 2). During mpg-CN synthesis covalent bonding of cyanamide and its polycondensation products, melem and melon, to a SiO2 surface via abundant NH2-groups (edge plane of the material) is more favorable compared to non-covalent interaction of the π-conjugated system (basal plane of the material) with the silica surface34. Therefore, we speculate that hard templating approach gives edge plane-terminated nanocrystalline material.

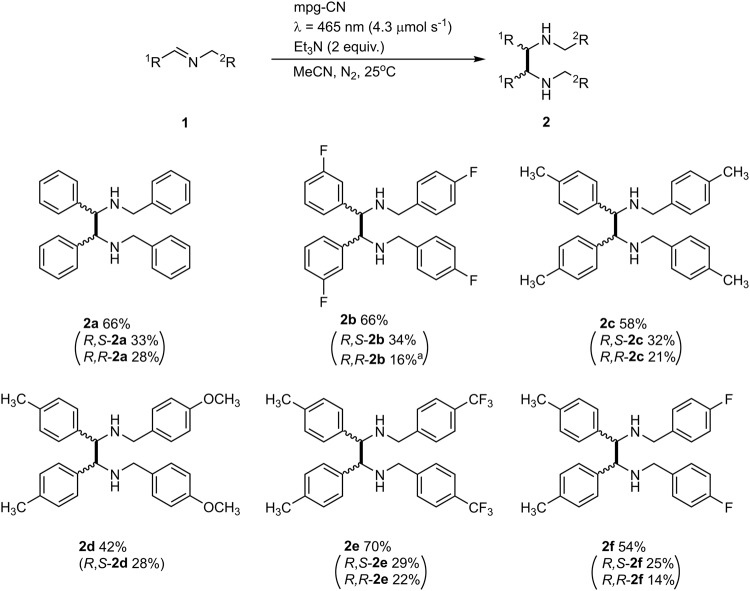

A scope of aza-pinacol coupling

A series of ethanediamines 2a-f was prepared by coupling imines 1a-f on 3.5 mmol scale in a batch reactor (Fig. 5). At room temperature, the R,S-isomers are solids, while the R,R-isomers are either liquids, R,R-2a, 2c-f or solids with low melting point, R,R-2b. Due to this feature the isomers were separated by fractional crystallization from methyl tert-butylether (MTBE) or pentane. In all cases, slight deviation of d.r. from 1:1 is likely due to a follow up process that selectively affects the R,R-isomer (Supplementary Table 18). Imidazolidine is a by-product detected in the reaction mixture (Supplementary Fig. 3). This compound is formed from 2c and acetaldehyde, which was generated in situ upon triethylamine oxidation35. The imine derived from vaniline and 4-trifluoromethylbenzyl amine did not give the corresponding coupling product, likely due to interaction of a phenolic proton with g-CN surface and the subsequent ES-PCET36,37 rather than tertiary amine. Coupling of 1a with Zn dust as a chemical reductant in the dark on a comparable scale gave a mixture of dibenzylamine, R,S-2a and R,R-2a in 5.25:1:1 ratio and the combined isolated yield of 2a of 36%38. These results point at the advantage of the photochemical approach compared to chemical reduction with Zn dust to reach higher selectivity toward 2a, 38% vs. 66%. Even if dibenzylamine is formed, mpg-CN converts it into 2a via a facile dehydrogenation/hydrogenation cascade15.

Fig. 5. A scope of aza-pinacol coupling.

Conditions: imine 1 (3.5 mmol), mpg-CN-8nm-193 (0.7 g), MeCN (70 mL), Et3N (0.98 mL, 7 mmol), N2, 25 ± 2 °C, 24 h. 1H NMR vs. 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard and isolated (in parentheses) yields of ethanediamines. aA mixture of R,R-2b:R,S−2b = 1.0:0.15.

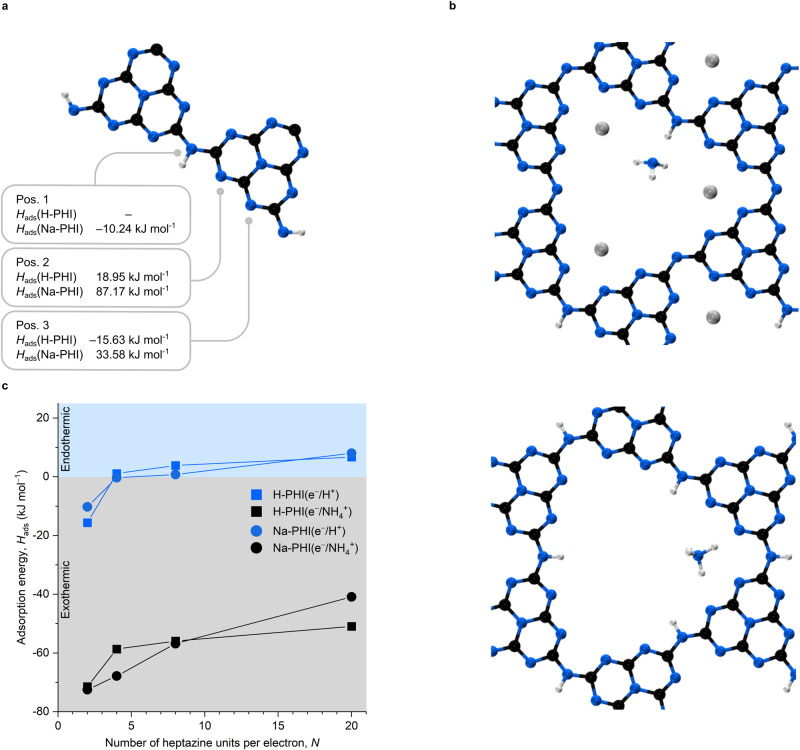

Results of DFT modeling

In order to explain our experimental results we modeled photocharged Na-PHI and H-PHI bearing H+ and NH4+ as counter ions (Supplementary Discussion 9). Given that the behavior of H-PHI in the experiment with benzylamine is similar to mpg-CN (Fig. 3c) and its crystal structure was reported39, we also modeled a photocharged state of this material. Simulations reveal a significant difference in energy for adsorption of H+ and NH4+ and a different adsorption behavior when comparing H-PHI and Na-PHI.

Structures for Na-PHI and H-PHI are derived from those published by Sahoo et al.40 by geometrical optimizing cell and structure properties without constraints regarding cell shape or atomic positions. We observe that the strict AA-stacking pattern breaks and the sodium counter ions move towards their energetical optimum in the pores within the g-CN layer (Supplementay Fig. 4).

To model excitation states of the two model structures with static DFT, hydrogen and ammonium radicals were introduced, and adsorption energies observed. To initially identify preferential facets for adsorption a case study for hydrogen has been conducted. Therefore, the interaction of a hydrogen radical at three different positions, labeled as 1, 2, and 3 in Fig. 6a, on periodic systems with 2 heptazine basis units was investigated. The adsorption energy Hads is calculated as described in Eq. (1).

| 1 |

Fig. 6. Results of DFT calculations.

a Three in-layer adsorption sites, shown for H-PHI with two heptazine units. b Adsorption of ammonium on Na-PHI with Hads = ‒72.48 kJ mol−1 (top) and H-PHI with Hads = ‒71.46 kJ mol−1 (blue spheres represent nitrogen, gray ones sodium, black ones carbon and white ones hydrogen atoms). Source data are provided as a Source data file. c Adsorption energies of hydrogen and ammonium in Na-PHI and H-PHI with respect to the number of heptazine units. Hads < 0 means that adsorption is a spontaneous process, while desorption in uphill. When Hads > 0—PHI does not bind hydrogen atom, while desorption is a spontaneous process.

Note that E is a potential energy and therefore has a negative sign, which yields negative adsorption energies for exothermic process, while positive adsorption energies—endothermic. Desorption energies could be obtained by multiplying the obtained values by –1.

As Fig. 6a shows, only position 3 in H-PHI and position 1 in Na-PHI show exothermic adsorption behavior. In the case of Na-PHI, hydrogens at position 2 and 3 are sterically competing with sodium ions, which are preferentially placed in the corners of the pore, leading to very unlikely, endothermic adsorption energies. For H-PHI, beneficial interactions with nitrogen of the neighboring heptazine, and the proximity of another hydrogen can explain the energy values for position 3 and 2. Preferential sorption of charge-compensating cations at the edge plane agrees well with the observed earlier migration of photogenerated electrons to the edge plane of PTI/Li+Cl‒ single crystals41. Temperature and solvent effects were not included in the model due to the high complexity and demanding computational costs.

Due to the limited pore size, steric effects become more important regarding the adsorption of ammonium, which reduces the amount of potential adsorption sites. These are displayed in the Fig. 6b for H-PHI and for Na-PHI. The first and foremost observation from the figures is that Na-PHI fissures NH4+ into NH3 and a covalently bonded hydrogen, while no bond breaking appears when NH4+ is adsorbed on H-PHI. This behavior is identical for all studied systems, irrespective of the e‒ per heptazine density (Fig. 6c, see discussion below). Since Hads, which is calculated for this case by adding a potential energy term for ammonia, ‒E(NH3), to (1), only differs slightly between H- and Na-PHI (Fig. 6b), this divergent adsorbing behavior can, among other explanations, possibly be accountable for the divergent catalytic behavior observed in Fig. 2.

As mentioned above, adsorption energies of H+ and NH4+ were calculated for a varying number of heptazine units to investigate the influence of e‒ charge density, which experimentally corresponds to the mass of added g-CNs in the reaction mixture. The results are plotted in Fig. 6c. A clear tendency of a decrease in adsorption energy with increasing system size is observable, hydrogen adsorption even turns endothermic for systems bearing more than four heptazine units. A possible explanation for this trend is the better delocalization of the electrons within structures with larger π-systems, which decreases the negative charge at the adsorption facet. As adsorption energies decrease, so do desorption energies increase, which lowers the amount of energy necessary to recover g-CN by desorbing e‒/H+ (or e‒/NH4+).

The results of the DFT modeling indicate that enthalpy of both H+ and NH4+ adsorption on H-PHI radical anion depends on the degree of material charging. Thus, in strongly reduced H-PHI and Na-PHI with up to 1e‒/1H+ (or 1e‒/1NH4+) per 2 heptazine units Hads < 0. In other words, desorption of e‒/H+ (or e‒/NH4+) from such photocharged PHIs is endothermic process. On the other hand, in mildly-reduced PHIs with only 1e‒/1H+ per 20 heptazine units Hads > 0—desorption of e‒/H+ is exothermic. Moreover, regardless of the degree of PHIs photocharging, desorption of e‒/NH4+ is always uphill. In the context of the benzylamine tetramerization cascade process, these results agree with the experiment in two aspects:

(1) Higher yield of 2a is obtained, when the reaction is conducted at 80 °C compared to room temperature. Heating is required to overcome the energy barrier of PCET from photocharged H-PHI(e‒/H+) to imine 1a (Fig. 2).

(2) Higher yield of 2a is obtained, when the reaction is conducted using a greater mass of g-CNs. Under such conditions materials are photocharged to lesser extent, which results in Hads > 0 and weak binding of e‒/H+ by g-CN (e‒/H+). Photocharged semiconductors can be divided into electronically doped and redox-shifted42. In the former, the quasi Fermi level of electrons moves to a more negative potential on the electrochemical scale. In the latter, the quasi Fermi level of electrons is equal to the potential of the conduction band. The dependence of Hads on the degree of g-CN photocharging and their reactivity toward oxidants suggest transition between these two classifications.

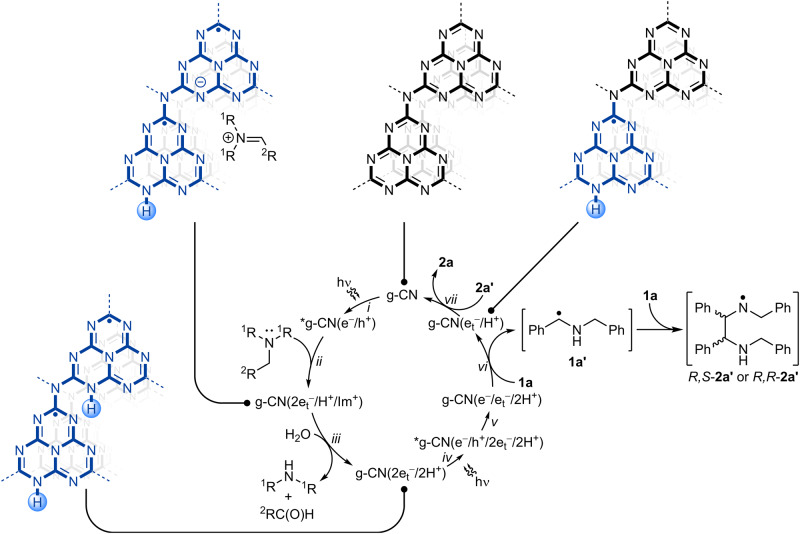

Discussion

Taking into account the acquired experimental data and the results of DFT modeling, the mechanism of aza-pinacol coupling and a chemical model of structural changes in g-CN that occur in this process is shown in Fig. 7. Absorption of a photon by a g-CN gives an excited state, *g-CN(e−/h+), where e− denotes a photogenerated "hot" electron and h+—a photogenerated hole (step i). According to the results of an EPR study, the distance between a hole and an electron in the charge separated state is ~2 nm, which corresponds to 4 heptazine units43. Quenching of the photogenerated hole by trialkylamine gives a photocharged state, in which negative charge is compensated by a proton and an iminium cation, g-CN(2et−/H+/Im+) (step ii). In this state, electrons are labeled as “et‒” to emphasize that they are trapped44. While the basicity of heptazine is low (pKa of the conjugated acid ~0 or negative), the heptazine radical anion is more basic. According to the results of DFT modeling, two heptazine units that form a “triangular pocket” at the edge plane of the graphitic structure pincer H+ and a charge-compensating iminium cation45. Due to these structural features the edge plane of g-CN is the site where oxidation of the substrate takes place. Hydrolysis of an iminium cation by trace amounts of water present in MeCN produces a molecule of dialkylamine, aldehyde and g-CN(2et−/2H+) (step iii). Taking into account the dependence of δ on the type of the tertiary amine, Et3N vs. nBu3N, the intermediary iminium cation remains bound to the surface of g-CN while its hydrolysis is slower compared to oxidation of the tertiary amine. In photocharged g-CN quenching experiments, however, electron transfer occurs from g-CN(2et−/2H+) to MV2+. Such assumption is also supported by the earlier observations that sorption of H+ at photocharged ZnO nanoparticles is more preferable compared to the bulky organic cations, such as nBu4N+46. Experiments using photocharged carbon nitride semiconductors in the dark suggest that a trapped et− does not reduce 1a to the benzylic radical 1a’. Therefore, absorption of a second photon is necessary for the reaction to proceed (step iv). The excited state of the semiconductor is denoted as *g-CN(e−/h+/2et−/2H+). Due to the potential of the valence band in Na-PHI and mpg-CN being +1.9 V and +1.2 V vs. SCE, respectively47,48, the photogenerated hole reacts with et− (step v). The remaining in the conduction band "hot" electron (e‒), which is not trapped, in combination with the proton stored at the edge plane of the graphitic structure participates in PCET to yield 1a’ and g-CN(et‒/H+) (step vi). As there is apparently no diastereoselective control, interaction between 1a’ and 1a gives either R,S-2a’ or R,R-2a’. Given that N-H BDFE in secondary amines is ~315–372 kJ mol−1 49, R,S-2a’ or R,R-2a’ extract e‒/H+ from g-CN(et‒/H+), which produces R,S-2a or R,R-2a, respectively, and closes the photocatalytic cycle. When imine 1a is no longer present in the reaction mixture, the reaction pathway shown in Fig. 7 is terminated at step iii, and leads to saturation of the g-CN structure with electrons, which is confirmed by kinetics studies (Supplementary Discussion 10). In a broader context, such behavior agrees well with the results of TiO2 nanoparticles photocharging in iso-propanol/styrene oxide mixture50 and ZnO in ethanol/acetaldehyde mixture51. Styrene oxide and acetaldehyde, similar to 1a, act as e–/H+ acceptors lowering the number of electrons stored in the semiconductors. Tetramerization of benzylamine proceeds via a mechanism similar to aza-pinacol coupling although more elementary steps are involved (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Fig. 7. A scheme of aza-pinacol coupling mechanism.

*g-CN—electronically-excited state of carbon nitride, e−—photogenerated "hot" electron, h+—photogenerated hole, et‒—trapped electron, H+—proton, Im+— iminium cation derived from trialkylamine.

We investigated the mechanism of the uptake of electrons and charge-compensating ions (H+, NH4+) from amines by g-CN semiconductor upon irradiation with light, the storage of these electrons and cations in g-CN and the transfer of e‒/H+ to the unsaturated substrate, such as an imine. The key findings of this study are:

1. Taking into account the dependence of the specific concentration of electrons (δ) on the type of tertiary amine, smaller Et3N vs. larger nBu3N, the results of DFT modeling and previous observations41, we conclude that H+ and NH4+ must be stored at the edge plane of g-CN nanocrystals in ‘triangular pockets’ created by two adjacent heptazine units.

2. δ is independent on the specific surface area (84–204 m2 g−1) of mpg-CN. This is explained by the fact that even for mpg-CN with relatively low surface area, 84 m2 g−1, in the photocharged state, ratio between the number of surface heptazine units to the number of e‒/H+ couples is >1.

3. DFT modeling revealed that the energy of cation adsorption (Hads) depends on the degree of g-CN photocharging. In strongly reduced g-CN, with up to 1e‒ per two heptazine units Hads < ‒10 kJ mol−1, i.e., the transfer of e‒/H+ from such a g-CN state to a substrate is endergonic. In tetramerization of benzylamine induced by light irradiation, heating is therefore beneficial to facilitate e‒/H+ transfer from reductively quenched g-CN to the intermediary imine. On the other hand, in mildly reduced g-CN with 1e‒ per ≥4 heptazine units, Hads > 0, i.e., g-CN does not bind e‒/H+, which makes e‒/H+ transfer spontaneous. Substitution of H+ by NH4+ in the micropore of PHI results in an even more substantial stabilizing influence onto the electron. H-PHI and Na-PHI photocharged in the presence of NH4+ are characterized by Hads < ‒70 kJ mol−1, which makes e‒/H+ transfer to a substrate highly endergonic.

4. Overall, endergonic e‒/H+ transfer from photocharged g-CN to a substrate could be enabled by (i) conducting the reaction in the presence of a larger amount of g-CN and (ii) increasing reaction temperature. In other words, materials carrying one extra electron per 1–3 heptazine units are weaker reductants due to Hads ≪ 0, while materials photocharged to the lowest degree, i.e., 1 e‒ per many heptazine units, are strong reductants due to Hads > 0.

5. Exceptionally strong stabilization of electrons in PHIs was observed when photocharging was conducted in an aqueous solution of NH4COOH. The photocharged PHI appears as a black solid and retains added electrons in air for hours. This property could be used to study such a state of g-CN under ambient conditions and to design air-stable hybrid composites.

Methods

Additional experimental details are given in the Supplementary Information.

Screening of reaction conditions of benzylamine tetramerization

A mixture of benzylamine (21 µL, 0.2 mmol), a semiconductor (20 mg), MeCN (2 mL) and a magnetic stirring bar were placed into a 5 mL screw-capped glass tube. The mixture was degassed three times using freeze-pump-thaw procedure and refilled with Ar. The mixture was stirred under irradiation with an LED for 24 h. After irradiation was stopped, a solution of 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (0.02 mmol, 0.1 mL, 0.2 M) in CH3CN was added to the reaction mixture. The reaction mixture was transferred into a 2 mL Eppendorf tube and centrifuged (13,300 rpm, 11,000 × g, 3 min). The supernatant layer was separated. The semiconductor was washed with CH2Cl2 (3 × 2 mL) followed by centrifugation. The organic phases were combined in a flask and solvent was evaporated in vacuum (50 °C, 150 mbar). The residue was dissolved in CDCl3 (0.9 mL) and analyzed by 1H NMR.

Synthesis of R,S-2a-f and R,R-2a-f using mpg-CN-8nm-193

A mixture of imine 1 (3.5 mmol), mpg-CN-8nm-193 (0.7 g), MeCN (70 mL) and Et3N (0.98 mL, 7 mmol) and a magnetic stirring bar were loaded into a three-neck glass tube equipped with a cold-finger, an inlet for N2 and a temperature sensor that was connected to a thermostat. The mixture was purged with N2 for 5 min and held under a positive pressure of N2 of ~0.1 bar to avoid possible air leakage into the reactor. The mixture was stirred under irradiation by blue LED (465 nm, 4.3 µmol s−1) for 24 h. The temperature was set to 25 °C and controlled by a thermostat. The reaction progress was monitored by 1H NMR. Upon complete conversion of the imine 1, the reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuum (+50 °C, 100 mbar). The resultant solid was washed with CH2Cl2 (4 × 8 mL) and separated by centrifugation (13,000 rpm, 11,000 × g, 3 min). Organic washings were combined and filtered through a 0.3 μm PTFE syringe filter. The solution was diluted with CH2Cl2 to a total volume of 30 mL. An aliquot (0.5 mL) was mixed with a solution of internal standard, 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (0.02 mmol, 0.1 mL, 0.2 M in MeCN), and concentrated in vacuum (+50 °C, 100 mbar). The yield of R,S-2 and R,R-2 isomers was calculated from the 1H NMR spectra. The whole amount of the R,S-2 and R,R-2 isomers solution in CH2Cl2 was concentrated in vacuum (+50 °C, 50 mbar). The residue was triturated with pentane, the solid was filtered and washed with a small amount of pentane. Recrystallization from MTBE afforded R,S-2. The pentane solution was concentrated in vacuum (+50 °C, 500 mbar). The oily residue was purified by column chromatography using a stationary phase of basic Al2O3 (65 g). The R,R-2 isomer was obtained by washing the column with equal volumes of eluent with gradually increasing polarity—(1) hexane 2 × 100 mL, (2) hexane:ethylacetate (19:1) 2 × 100 mL, (3) hexane:ethylacetate (9:1) 2 × 100 mL, (4) hexane:ethylacetate (4:1) 3 × 100 mL.

Computational details

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were conducted using the Gaussian and plane wave approach52 as implemented in the CP2K suite of programs53. If not specified otherwise, all simulations were conducted using periodic boundary conditions and a plane wave cutoff of 500 Ry to represent the electron density, whereas the Kohn-Sham orbitals are described by a molecularly optimized double-zeta Gaussian basis set46. The Becke-based B97-3c exchange and correlation functional was employed in conjunction with an empirical dispersion correction to account for long-range van der Waals interactions54. Net atomic charges are quantified by means of the density derived electrostatic and chemical DDEC6 method55.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

The Max Planck Society is acknowledged for financial support of this project and providing infrastructure for research. Dr. Artem Mishchenko, Dr. Dmitry I. Sharapa, Dr. Clemens Schmitt, Michael Born, Jessica Brandt, Dr. Jiajia Cheng and Prof. Xinchen Wang are acknowledged for their help with the project.

Author contributions

O.S. performed experimental studies, carried out the analysis and supervised the work. K.N. performed the computational studies. T.D.K. supervised the work. V.S. performed experimental studies. Y.M. performed experimental studies. M.A. supervised the work.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Filip Podjaski and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

O.S. and M.A. declare personal financial interests. A patent WO/2019/081036 has been filed by the Max Planck Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften E.V. in which O.S. and M.A. are listed as co-authors. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-43328-6.

References

- 1.Lennox JC, Kurtz DA, Huang T, Dempsey JL. Excited-state proton-coupled electron transfer: different avenues for promoting proton/electron movement with solar photons. ACS Energy Lett. 2017;2:1246–1256. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capaldo L, Ravelli D, Fagnoni M. Direct photocatalyzed hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) for aliphatic C–H bonds elaboration. Chem. Rev. 2022;122:1875–1924. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strieth-Kalthoff F, James MJ, Teders M, Pitzer L, Glorius F. Energy transfer catalysis mediated by visible light: principles, applications, directions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018;47:7190–7202. doi: 10.1039/C8CS00054A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu G-Q, Xu P-F. Visible light organic photoredox catalytic cascade reactions. Chem. Commun. 2021;57:12914–12935. doi: 10.1039/D1CC04883J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metternich JB, Gilmour R. One photocatalyst, n activation modes strategy for cascade catalysis: emulating coumarin biosynthesis with (−)-riboflavin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:1040–1045. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neveselý T, Daniliuc CG, Gilmour R. Sequential energy transfer catalysis: a cascade synthesis of angularly-fused dihydrocoumarins. Org. Lett. 2019;21:9724–9728. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.James MJ, Schwarz JL, Strieth-Kalthoff F, Wibbeling B, Glorius F. Dearomative cascade photocatalysis: divergent synthesis through catalyst selective energy transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:8624–8628. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b03302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma J, et al. Facile access to fused 2D/3D rings via intermolecular cascade dearomative [2 + 2] cycloaddition/rearrangement reactions of quinolines with alkenes. Nat. Catal. 2022;5:405–413. doi: 10.1038/s41929-022-00784-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan D-M, Zhao Q-Q, Rao L, Chen J-R, Xiao W-J. Eosin Y as a redox catalyst and photosensitizer for sequential benzylic C−H amination and oxidation. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018;24:16895–16901. doi: 10.1002/chem.201804229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang H, et al. Visible light-induced cyclization reactions for the synthesis of 1,2,4-triazolines and 1,2,4-triazoles. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:9644–9647. doi: 10.1039/C7CC04911K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Habisreutinger SN, Schmidt-Mende L, Stolarczyk JK. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 on TiO2 and other semiconductors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:7372–7408. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su F, et al. Aerobic oxidative coupling of amines by carbon nitride photocatalysis with visible light. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:657–660. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurpil B, Kumru B, Heil T, Antonietti M, Savateev A. Carbon nitride creates thioamides in high yields by the photocatalytic Kindler reaction. Green. Chem. 2018;20:838–842. doi: 10.1039/C7GC03734A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazzanti S, Kurpil B, Pieber B, Antonietti M, Savateev A. Dichloromethylation of enones by carbon nitride photocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1387. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15131-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitkina T, et al. Visible light mediated homo- and heterocoupling of benzyl alcohols and benzyl amines on polycrystalline cadmium sulfide. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:3556–3561. doi: 10.1039/c2ob07053g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakajima M, Fava E, Loescher S, Jiang Z, Rueping M. Photoredox-catalyzed reductive coupling of aldehydes, ketones, and imines with visible light. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:8828–8832. doi: 10.1002/anie.201501556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, Qu J-P, Kang Y-B. CBZ6 as a recyclable organic photoreductant for pinacol coupling. Org. Lett. 2021;23:2900–2903. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c00537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steiner A, et al. Implementing hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) catalysis for rapid and selective reductive photoredox transformations in continuous flow. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019;2019:5807–5811. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201900952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okamoto S, Kojiyama K, Tsujioka H, Sudo A. Metal-free reductive coupling of C=O and C=N bonds driven by visible light: use of perylene as a simple photoredox catalyst. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:11339–11342. doi: 10.1039/C6CC05867A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savateev, O. et al. Assignment of the crystal structure to the aza-pinacol coupling product by X-ray diffraction and density functional theory modeling. ACS Omega7, 41581–41585 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Savateev A, Pronkin S, Willinger MG, Antonietti M, Dontsova D. Towards organic zeolites and inclusion catalysts: heptazine imide salts can exchange metal cations in the solid state. Chem. - Asian J. 2017;12:1517–1522. doi: 10.1002/asia.201700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Savateev O. Photocharging of semiconductor materials: database, quantitative data analysis, and application in organic synthesis. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022;12:2200352. doi: 10.1002/aenm.202200352. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lau VW-H, et al. Dark photocatalysis: storage of solar energy in carbon nitride for time-delayed hydrogen generation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017;56:510–514. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markushyna Y, et al. Green radicals of potassium poly(heptazine imide) using light and benzylamine. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2019;7:24771–24775. doi: 10.1039/C9TA09500D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kröger J, et al. Conductivity mechanism in ionic 2D carbon nitrides: from hydrated ion motion to enhanced photocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 2022;34:2107061. doi: 10.1002/adma.202107061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Podjaski F, Kröger J, Lotsch BV. Toward an aqueous solar battery: direct electrochemical storage of solar energy in carbon nitrides. Adv. Mater. 2018;30:1705477. doi: 10.1002/adma.201705477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Savateev O, Zou Y. Identification of the structure of triethanolamine oxygenation products in carbon nitride photocatalysis. ChemistryOpen. 2022;11:e202200095. doi: 10.1002/open.202200095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghosh T, Das A, König B. Photocatalytic N-formylation of amines via a reductive quenching cycle in the presence of air. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017;15:2536–2540. doi: 10.1039/C7OB00250E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wada Y, Kitamura T, Yanagida S. CO2-fixation into organic carbonyl compounds in visible-light-induced photocatalysis of linear aromatic compounds. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2000;26:153–159. doi: 10.1163/156856700X00192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Markushyna Y, Völkel A, Savateev A, Antonietti M, Filonenko S. One-pot photocalalytic reductive formylation of nitroarenes via multielectron transfer by carbon nitride in functional eutectic medium. J. Catal. 2019;380:186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2019.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Savateev A, Kurpil B, Mishchenko A, Zhang G, Antonietti M. A “waiting” carbon nitride radical anion: a charge storage material and key intermediate in direct C–H thiolation of methylarenes using elemental sulfur as the “S”-source. Chem. Sci. 2018;9:3584–3591. doi: 10.1039/C8SC00745D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gouder A, Jiménez-Solano A, Vargas-Barbosa NM, Podjaski F, Lotsch BV. Photomemristive sensing via charge storage in 2D carbon nitrides. Mater. Horiz. 2022;9:1866–1877. doi: 10.1039/D2MH00069E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lotsch BV, et al. Unmasking melon by a complementary approach employing electron diffraction, solid-state NMR spectroscopy, and theoretical calculations—structural characterization of a carbon nitride polymer. Chem. - Eur. J. 2007;13:4969–4980. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Groenewolt M, Antonietti M. Synthesis of g-C3N4 nanoparticles in mesoporous silica host matrices. Adv. Mater. 2005;17:1789–1792. doi: 10.1002/adma.200401756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ando S, Xiao B, Ishizuka T. Synthesis of imidazolinium salts by Pd/C-catalyzed dehydrogenation of imidazolidines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021;2021:4551–4554. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.202100914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song T, et al. Aerobic oxidative coupling of resveratrol and its analogues by visible light using mesoporous graphitic carbon nitride (mpg-C3N4) as a bioinspired catalyst. Chem. - Eur. J. 2014;20:678–682. doi: 10.1002/chem.201303587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rabe EJ, et al. Barrierless heptazine-driven excited state proton-coupled electron transfer: implications for controlling photochemistry of carbon nitrides and aza-arenes. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2019;123:29580–29588. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b08842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsukinoki T, Nagashima S, Mitoma Y, Tashiro M. Organic reaction in water. Part 4. New synthesis of vicinal diamines using zinc powder-promoted carbon–carbon bond formation. Green. Chem. 2000;2:117–119. doi: 10.1039/b001533o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schlomberg H, et al. Structural insights into poly(heptazine imides): a light-storing carbon nitride material for dark photocatalysis. Chem. Mater. 2019;31:7478–7486. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b02199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sahoo SK, et al. Photocatalytic water splitting reaction catalyzed by ion-exchanged salts of potassium poly(heptazine imide) 2D materials. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2021;125:13749–13758. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c03947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin L, et al. Molecular-level insights on the reactive facet of carbon nitride single crystals photocatalysing overall water splitting. Nat. Catal. 2020;3:649–655. doi: 10.1038/s41929-020-0476-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schimpf AM, Knowles KE, Carroll GM, Gamelin DR. Electronic doping and redox-potential tuning in colloidal semiconductor nanocrystals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:1929–1937. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Actis A, et al. Morphology and light-dependent spatial distribution of spin defects in carbon nitride. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022;61:e202210640. doi: 10.1002/anie.202210640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Godin R, Wang Y, Zwijnenburg MA, Tang J, Durrant JR. Time-resolved spectroscopic investigation of charge trapping in carbon nitrides photocatalysts for hydrogen generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:5216–5224. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b01547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galushchinskiy, A. et al. Insights into the role of graphitic carbon nitride as a photobase in proton-coupled electron transfer in (sp3)C‒H oxygenation of oxazolidinones. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 62, e202301815 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Valdez CN, Delley MF, Mayer JM. Cation effects on the reduction of colloidal ZnO nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:8924–8933. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b05144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Z, et al. The easier the better” preparation of efficient photocatalysts—metastable poly(heptazine imide) salts. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1700555. doi: 10.1002/adma.201700555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghosh I, et al. Organic semiconductor photocatalyst can bifunctionalize arenes and heteroarenes. Science. 2019;365:360–366. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Warren JJ, Tronic TA, Mayer JM. Thermochemistry of proton-coupled electron transfer reagents and its implications. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:6961–7001. doi: 10.1021/cr100085k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Y, Ji H, Chen C, Ma W, Zhao J. Concerted two-electron transfer and high selectivity of TiO2 in photocatalyzed deoxygenation of epoxides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:12636–12640. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carroll GM, Schimpf AM, Tsui EY, Gamelin DR. Redox potentials of colloidal n-type ZnO nanocrystals: effects of confinement, electron density, and Fermi-level pinning by aldehyde hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:11163–11169. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lippert G, Hutter J, Parrinello M. A hybrid Gaussian and plane wave density functional scheme. Mol. Phys. 1997;92:477–488. doi: 10.1080/00268979709482119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kühne TD, et al. CP2K: an electronic structure and molecular dynamics software package - Quickstep: efficient and accurate electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2020;152:194103. doi: 10.1063/5.0007045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brandenburg JG, Bannwarth C, Hansen A, Grimme S. B97-3c: a revised low-cost variant of the B97-D density functional method. J. Chem. Phys. 2018;148:064104. doi: 10.1063/1.5012601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Manz, T. A. & Limas, N. G. Introducing DDEC6 atomic population analysis: part 1. Charge partitioning theory and methodology. RSC Adv.6, 47771–47801 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.