Abstract

Psychology must confront the bias in its broad literature toward the study of participants developing in environments unrepresentative of the vast majority of the world’s population. Here, we focus on the implications of addressing this challenge, highlight the need to address overreliance on a narrow participant pool, and emphasize the value and necessity of conducting research with diverse populations. We show that high-impact-factor developmental journals are heavily skewed toward publishing articles with data from WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) populations. Most critically, despite calls for change and supposed widespread awareness of this problem, there is a habitual dependence on convenience sampling and little evidence that the discipline is making any meaningful movement toward drawing from diverse samples. Failure to confront the possibility that culturally specific findings are being misattributed as universal traits has broad implications for the construction of scientifically defensible theories and for the reliable public dissemination of study findings.

Keywords: WEIRD data, Cross-cultural research, Generalizable data, Representative data, Developmental science, Diversity, Cultural psychology, Developmental psychology

Introduction

Growing attention has been drawn to the lack of diversity in psychological testing, in particular to the fact that the vast majority of psychological research has been conducted on populations that are unrepresentative of human culture more globally—those from WEIRD (Western, educated, industrial, rich, and democratic) backgrounds (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010; Legare & Harris, 2016; Nielsen & Haun, 2016). The dearth of systematic research outside of Western cultural contexts is a major impediment to theoretical progress in the psychological sciences (Legare & Nielsen, 2015; Rowley & Camacho, 2015). Where psychological researchers assume that data are not specific to the sample of participants under direct test (i.e., that findings are generalizable), lack of attention to cultural variation and its psychological consequences risks yielding incomplete, and potentially inaccurate, conclusions (e.g., Apicella & Barrett, 2016; Evans & Schamberg, 2009; Mani, Mullainathan, Shafir, & Zhao, 2013; Votruba-Drzal, Miller, & Coley, 2016).

A complete understanding of the ontogeny and phylogeny of the developing human mind depends on sampling diversity (Clegg & Legare, 2016; Herrmann, Call, Hernandez-Lloreda, Hare, & Tomasello, 2007; Machluf & Bjorklund, 2015; Nielsen, 2012; van Schaik & Burkart, 2011). Where research efforts are focused on identifying core mechanisms or universal aspects of psychology, failure to acknowledge the possible impact of environment on the behavior of participants must be considered at best neglectful and at worst bad science. Our aim here is to show, presenting new data, that the influence of culture—“a set of meanings or information that is non-genetically transmitted from one individual to another, which is more or less shared within a population (or a group) and endures for some generations” (Kashima & Gelfand, 2012, p. 640)—is not afforded sufficient attention in the developmental literature. Moreover, despite growing awareness of a need to change, we show that there is little shift in research practices that overly rely on data from a markedly narrow sample pool and little acknowledgment that this is potentially problematic for interpreting data and arising theoretical assumptions.

From the limited research that exists, there is clear evidence of substantial differences between Western educated industrialized communities and non-Western populations in fundamental aspects of child development (Bornstein, 1991; Corsaro, 1996; Gaskins & Paradise, 2010; Kruger & Tomasello, 1996; Lave & Wenger, 1991; LeVine, LeVine, Schnell-Anzola, Rowe, & Dexter, 2012; Miller & Goodnow, 1995; Rogoff, 2003). This includes evidence for cross-cultural variation in child socialization and how parents interact with their infants (Keller, 2007; Keller & Kärtner, 2013; Kärtner, 2015), the kinds of tasks parents engage their infants in (Cole, 1996; Lancy, Bock, & Gaskins, 2010), and the amount of time children spend with nonparental caregivers and peers (Gaskins, 2006; LeVine, 1980). For example, there is cultural variation in the degree to which mothers focus on face-to-face interaction and object play when engaging their infants that leads to culture-specific maternal reactions to infants’ communicative signals (Keller et al., 2004; Kärtner, 2015; Little, Carver, & Legare, 2016).

Cultural variation has also been documented in other fundamental aspects of human cognition (Wang, 2017). For example, Haun, Rapold, Call, Janzen, and Levinson (2006) found that Hai//om children tend to employ a geocentric search strategy (where the position of relevant items is maintained relative to the larger surrounding environment) to find something hidden among an array of overturned cups, in contrast to the egocentric approach (where the position of relevant items is maintained relative to the viewpoint of the children) adopted by Western children. Our aim here is not to dwell on culturally determined differences in children’s developmental environments but rather to draw attention to interpretation and the assumptions that would be made without consideration of potential cultural influences. If Haun and colleagues had tested only Western children, then it could have easily been assumed, as is typically written, that “children” employ egocentric search strategies. But “children” generally do not do so; only children from specific cultural backgrounds do.

Critically, there is no universal developmental context in which children grow up, nor is there a universal environment for the human mind. To understand psychological processes, thus, it is necessary to exercise caution when generalizing beyond the specific sociocultural context at hand (Clegg, Wen, & Legare, 2017). To reiterate, if an underlying goal of any research endeavor is to identify globally relevant patterns of development—and not patterns that are specific to one population in isolation—then failure to acknowledge the possible influence of cultural factors on participants’ responses is either neglectful or bad science (an error that each of us, as authors, has made). It is the equivalent of missing a confound and assuming that the data at hand are unaffected. For example, it would be illadvised to interpret children’s responses to questions relating to folk biological reasoning without acknowledging that such answers are population dependent and vary with culturally determined interactions with the natural world (Medin, Waxman, Woodring, & Washinawatok, 2010; Proffitt, Coley, & Medin, 2000; Ross, Medin, Coley, & Atran, 2003). It would be similarly ill-advised to make claims about human perceptual attention processes based on data collected with only Western or Asian participants (Nisbett & Miyamoto, 2005). For developmental science to be sure it is built on solid foundations, thus, it is critical that culturally variant and invariant patterns of development are identified and that it is acknowledged when reported data could be different if collected in a distinct sample. The alternative—that a sample lacking in cultural diversity is representative of all children—should no longer be treated as an acceptable default option.

Evidence for a persistent bias

Arguments that there is an inherent bias in what constitutes our participant pools are of course not new (Bornstein, 2002; Cole, 1996; Levine, Martinez, Brase, & Sorenson, 1994; Rogoff, 1990; Scribner & Cole, 1973; Serpell, 1976; Shweder, 1990; Super & Harkness, 1986; Whiting & Whiting, 1975). Building on these earlier endeavors, Henrich et al. (2010), in a prominent and highly cited article, drew attention to the disproportionate representation in psychology of what they coined “WEIRD” participants (i.e., those from Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic backgrounds). This extended previous work by Arnett (2008), who analyzed articles published from 2003 to 2007 in peak journals from six subdisciplines of psychology, revealing that 96% of the participants were from Western industrialized countries (68% from the United States alone) and that 99% of first authors were at universities in Western countries (73% from the United States alone). Putting this in the context of population size, 96% of psychological samples came from countries with only 12% of the world’s population, and this skew in sampling was apparent in Arnett’s analysis of the journal Developmental Psychology. Perhaps a wider assessment of developmental journals would have yielded a more representative picture.

To evaluate this possibility, we surveyed every article published between 2006 and 2010 in the journals Child Development, Developmental Psychology, and Developmental Science (consistently the highest ranked experimental developmental psychology journals by impact factor) and recorded the geographical region of the participants, whether they were human or non-human primates, and the affiliation of the first author. Participant information was gleaned from information on where data were collected provided in “method” sections, and it was noted when such information was not provided. Meta-analyses based on previously published data were excluded to avoid artificial inflation. Participant region and author affiliation were classified as (1) the United States (coded separately given Arnett’s prior identification that individuals from the United States are overrepresented in psychology research), (2) countries with English as their first language (i.e., effectively the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada), (3) European countries that do not have English as their first language, (4) Central and South America, (5) Africa, (6) Asia, and (7) the Middle East and Israel. Coding was not mutually exclusive in that an article featuring participants from different regions contributed data to all regions identified. The proportion of participant samples from each region from these journals across the 5 years assessed are presented in Table 1 (i.e., the percentage of the total number of articles surveyed featuring children from that region).

Table 1.

Percentages of participant representation in all articles published in Child Development, Developmental Psychology, and Developmental Science between 2006 and 2010.

| Category | WEIRD | Non-WEIRD | Other | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Origin | United States | 57.65 | African | 0.63 | Non-human primates | 1.45 |

| English speaking | 17.95 | South/Central American | 0.70 | Unspecified | 0.95 | |

| European | 14.92 | Asian | 4.36 | |||

| Israel/Middle East | 1.07 | |||||

| Total | 90.52 | 6.76 | 2.40 | |||

Note. WEIRD, Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic.

In terms of raw numbers, of the 1582 articles, 912 featured participants from the United States, 284 from English-speaking countries, and a further 236 from non-English-speaking Europe. Compare this with 112—the total number of articles featuring participants from all of Central and South America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East and Israel combined. Perhaps more sobering, only 11 articles featured participants from Central and South America, and only 10 featured participants from Africa—fewer than the 23 articles devoted to non-human primates and fewer than the 15 articles that did not specify where their participants were from. In terms of total participant numbers, 633,775 were from the United States—well over double the entire number from the rest of the world combined (286,321, with a further 1959 unspecified) after excluding data from one study involving all 654,707 births in Sweden from 1983 to 1991. Viewing this from another angle, less than 3% of the participants contributing to the expansion in our knowledge of children’s psychological development came from all of Central and South America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East and Israel combined (which notably contain ~85% of the world’s population; http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/).

Of 16911 articles assessed for author affiliation, 1029 (61%) were first-authored by faculty members of institutions in the United States, 341 (20%) by those in English-speaking countries, and another 251 (15%) by those in non-English-speaking European countries—with the remaining 4% being first-authored by faculty members of institutions in Asia and Israel. Only 2 articles had the first author located in Central or South America, and none had the first author located in the Middle East or Africa. The critical point about author origin is that it emphasizes how developmental psychology, as a discipline, is characterized as one in which individuals in WEIRD institutions study WEIRD participants.

A wider assessment of developmental journals than that reported by Arnett (2008) did not, therefore, yield a more representative picture. But perhaps this skew in sampling is historical. It has been more than 8 years since Arnett (2008) was published and more than 6 years since Henrich et al. (2010) was published. Given the citation count for the latter (>3000 times according to Google Scholar), change could reasonably be expected. Is there any evidence that our research has become less biased in its underrepresentation of the majority of the world’s humans over the last 8 years?

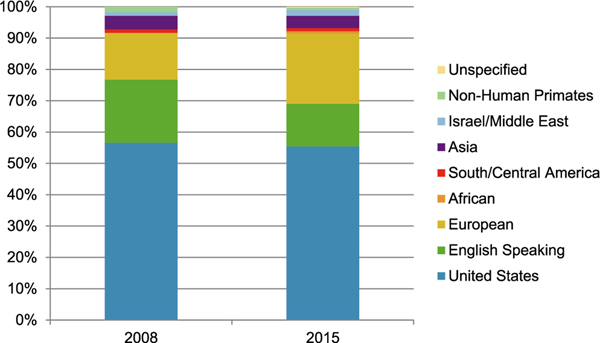

Following the same method outlined previously, we collated data on participant origin for all articles published in 2008 (361 articles)—the year Arnett’s review was published—and in 2015 (383 articles). As is evident in Fig. 1, little has changed in the sampling region. In 2008, 91.67% of all articles published featured participants from the United States, English-speaking countries, or non-Englishspeaking Europe, leaving 8.33% representing all of Central and South America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East and Israel combined. In 2015, the distribution between those two groups was remarkably similar to that in 2008 (92.37% and 7.63% respectively). This does not present a picture of a discipline thoughtfully contemplating its limitations and readily embracing change.

Fig. 1.

Percentages of participant representation in all articles published in Child Development, Developmental Psychology, and Developmental Science in 2008 and 2015.

Conclusion and a way forward

We have highlighted how the vast majority of the world’s population is underrepresented in high-impact developmental psychology research. There are many possible reasons for this. Opportunities for research with culturally heterogeneous samples are typically limited and depend on the commitment of unique, often substantive, temporal and fiscal resources and sometimes depend on years of investing in building trust among relevant communities with little immediate return. Authors from WEIRD backgrounds, hence, are not incentivized to pursue heterogeneous data collection practices. Furthermore, articles published in the journals sampled here are held to the highest standards of empirical rigor, and rejection rates are high. To meet standards for publication commonly requires extensive university training in scientific design, analysis, and writing. Research by staff at non-WEIRD institutions may be less consistent with Western-centric scientific practice or not done at all. Language is also a barrier. Whereas journals may encourage submission by authors from non-English-speaking backgrounds and offer to copyedit manuscripts, researchers without sufficient grasp of English to get to that level are forced to publish in local journals (or not at all). This runs another way as well. If reading in English is challenging, then identifying cutting-edge research may be elusive, leading to conducting research that is outside contemporary trends. Similarly, access to peak journals is expensive and might be beyond the budgets of many of the world’s universities. The obstacles may be many, but our preference is that these reasons be viewed as support for encouraging research featuring sampling diversity, not as excuses for perpetuating the status quo of failing to do so.

In certain situations, the exploration of possibly skewed findings as a result of restricted participant sampling might be redundant, but decisions about this need to be made through a lens of awareness and with appreciation of the potential impact of using homogeneous data. This latter point is key. Our suggestion is not that all developmental psychology studies must involve heterogeneous samples; this would be unreasonable and in many cases impractical. We are saying that where samples are from homogeneous groups, consideration should be given to the notion that whatever is being reported may be culturally specific, and hence possibly unrepresentative and not generalizable, and this should be openly acknowledged in print (e.g., in “discussion” sections).

There is a complementary need to acknowledge the implicit “othering” that can occur when issues of culture are referenced. Othering, a form of marginalization whereby individuals or groups are marked as distinct from oneself, is anchored in feminist theory and has been applied to the study of racism, identity, and difference (Ahmad, 1993; Fine, 1994; Hall, 1991; Tomaselli, 2003, 2005; Weis, 1995). Here, we use it to refer to situations where participants who are drawn from WEIRD cultures are considered to be the norm and those who are not are treated as exceptions to the norm. In this light, we borrow from the American Psychological Association (2003) publication of the guidelines on multicultural education, training, research, practice, and organizational change for psychologists and encourage researchers to recognize that, as cultural beings, they may hold attitudes and beliefs that can detrimentally influence their perceptions of research undertaken in populations that are economically, ethnically, and racially different from themselves.

If progress away from the sampling bias inherent in developmental psychology research identified here is to be made, then we need to shift away from this othering point of view. Positive steps forward include (a) encouraging publication of studies that feature non-WEIRD participants, (b) encouraging replication in a new population of a previously established finding, and (c) encouraging theoretically motivated cross-cultural comparisons that examine how children’s cultural environments might affect their development. Having members of editorial boards and grant-funding bodies with sufficient knowledge of the challenges encountered in collecting heterogeneous data will also help, especially when there is a need to distinguish reasonable from unreasonable reviewer critique.

We must be ever attentive to the possibility that where we think we are exploring human universals, we are rather exploring cultural specifics. A continued WEIRD-centric approach also has implications for the ways research is used. Where it forms the foundation for policy development, it is critical that the research match the target population. For example, in the United States there has been considerable political agitation and policy implementation aimed at bridging what has been termed the “word gap”—the disparity in the amount and quality of language that low-income children hear relative to their more affluent peers (Hart & Risley, 1995; Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015). Many interventions focus on supporting change in the way caregivers interact with their children. Such interventions may be relevant in the United States, but they might not be relevant in other countries where children and their caregivers engage with each other in ways that are not commensurate with dyadic interaction (Little et al., 2016; Rogoff, Mistry, Göncü, & Mosier, 1993).

Reflecting the above, developmental research commonly makes its way into the public domain, and hence it is important to make apparent when there is no foundation for broad generalization of reported findings. For example, the impact of divorce on children has been shown to differ across cultures and economic strata (Fischer, 2007); if a parent is seeking to gain insight into the issues that might confront his or her children after divorce, then consulting literature that does not apply to the parent’s circumstances may lead to unsubstantiated concerns or misguided intervention. Similarly, early childhood development programs are frequently based on sensitivity and mind-mindedness (Meins et al., 2002; Slade, 2005) as the core elements of optimal parenting that should be supported. However, these ideals are highly cultural and may deviate wildly from the models followed by caregivers from other cultures. This might lead practitioners to misinterpret caregivers’ behavior as “problematic” where in fact it is just an expression of another developmental pathway (Otto & Keller, 2014).

There will be criticisms of the concerns laid out here. Haeffel, Thiessen, Campbell, Kaschak, and McNeil (2009) suggested that “the problem of generalizability is often overstated. Studies using one sample of humans (e.g., Americans) often generalize to other samples of humans (e.g., Spaniards), particularly when basic processes are being studied (e.g., Anderson, Lindsay, & Bushman, 1999)” (p. 570). This assertion has several shortcomings. First, Haeffel and colleagues defined basic processes as “those psychological or biological processes that are shared by all humans at appropriate developmental levels (e.g., cognition, perception, learning, brain organization, genome)” (p. 570). This may be true, but the universality of such basic processes is commonly assumed rather than empirically documented. Second, the article they used to support their claim aimed to provide external validity to laboratory-based research, not to identify human universals. Haeffel and colleagues also argued, “It is not enough to show that American culture is different from other cultures. This fact is not disputed. The critical question is what these differences mean for human psychology” (p. 570). We agree, and this is the essence of our point. Theoretically driven, empirically falsifiable endeavors that involve participants across a range of environmental circumstances will enrich our understanding of psychology and help to clarify the validity of research findings.

A new path forward for developmental science is needed to meet this challenge to understand continuity and diversity in human cultural background. Although there may be widespread awareness of this challenge, what we highlight here is that this awareness is not translating into change in the approaches taken to publication strategy. Systematic comparisons across a wide variety of human environments are needed to enable examination of variation and stability in core domains of human psychology, and where convenience sampling is adhered to, the limitations of such an approach must be acknowledged. We need to accept the challenge posed by diversity, provide the explanations it requires, and harness this information to build an improved set of encompassing theories about the development of the human mind.

Acknowledgments

An Australian Research Council Discovery Project Grant (DP140101410) supported the writing of this manuscript. We also thank Karri Neldner and Kristyn Hensby for assistance in collecting the data reported here, and we thank Paul Harris, Bill von Hippel, and Yvette Miller for comments on an earlier draft.

Footnotes

The difference between this number and the number analyzed for participant number is due to our inclusion here of meta-analyses, theoretical articles, and review articles.

References

- Ahmad WIU (1993). Making black people sick: “Race”, ideology, and health research. In Ahmad WIU (Ed.), “Race” and health in contemporary Britain (pp. 12–33). Philadelphia: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association (2003). Guidelines on multicultural education, training, research, practice, and organizational change for psychologists. American Psychologist, 58, 377–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Lindsay JJ, & Bushman BJ (1999). Research in the psychological laboratory: Truth or triviality? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Apicella CL, & Barrett HC (2016). Cross-cultural evolutionary psychology. Current Opinions in Psychology, 7, 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2008). The neglected 95%: Why American psychology needs to become less American. American Psychologist, 63, 602–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH (1991). Cultural approaches to parenting. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH (2002). Toward a multiculture, multiage multimethod science. Human Development, 45, 257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Clegg JM, & Legare CH (2016). A cross-cultural comparison of children’s imitative flexibility. Developmental Psychology, 52, 1435–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg JM, Wen NJ, & Legare CH (2017). Is non-conformity WEIRD? Cultural variation in adult’s beliefs about children’s competency and conformity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146, 428–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M. (1996). Cultural psychology: A once and future discipline. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corsaro W. (1996). Transitions in early childhood: The promise of comparative, longitudinal ethnography. In Jessor R, Colby A, & Shweder R. (Eds.), Ethnography and human development: Context and meaning in social inquiry (pp. 419–458). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, & Schamberg MA (2009). Childhood poverty, chronic stress, and adult working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106, 6545–6549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine M. (1994). Working the hyphens: Reinventing self and other in qualitative research. In Denzin NK & Lincoln YS (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 70–82). London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer T. (2007). Parental divorce and children’s socio-economic success: Conditional effects of parental resources prior to divorce, and gender of the child. Sociology, 41, 475–495. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskins S. (2006). Cultural perspectives on infant–caregiver interaction. In Levenson S. & Enfield N. (Eds.), Roots of human sociality: Culture, cognition, and human interaction (pp. 279–298). Oxford, UK: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskins S, & Paradise R. (2010). Learning through observation in daily life. In Lancy DF, Bock JC, & Gaskins S. (Eds.), The anthropology of learning in childhood (pp. 85–118). Lanham, MD: AltaMira. [Google Scholar]

- Haeffel GJ, Thiessen ED, Campbell MW, Kaschak MP, & McNeil NM (2009). Theory, not cultural context, will advance American psychology. American Psychologist, 64, 570–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall S. (1991). Ethnicity, identity, and difference. Radical America, 9, 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, & Risley TR (1995). The early catastrophe: The 30 million word gap by age 3. American Educator, 27(1), 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Haun DBM, Rapold C, Call J, Janzen G, & Levinson SC (2006). Cognitive cladistics and cultural override in Hominid spatial cognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of American, 103, 17568–17573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J, Heine SJ, & Norenzayan A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 61–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann E, Call J, Hernandez-Lloreda MV, Hare B, & Tomasello M. (2007). Humans have evolved specialized skills of social cognition: The cultural intelligence hypothesis. Science, 317, 1360–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh-Pasek K, Adamson LB, Bakeman R, Owen MT, Golinkoff RM, Pace A, & Ellipsis Suma K. (2015). The contribution of early communication quality to low-income children’s language success. Psychological Science, 26, 1071–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärtner J. (2015). The autonomous developmental pathway: The primacy of subjective mental states for human behavior and experience. Child Development, 86, 1298–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashima Y, & Gelfand MJ (2012). A history of culture in psychology. In Kruglanski A. & Stroebe W. (Eds.), Handbook of the history of social psychology (pp. 640–667). New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keller H. (2007). Cultures of infancy. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Keller H, & Kärtner J. (2013). Development—The cultural solution of universal developmental tasks. Advances in Culture and Psychology, 3, 63–116. [Google Scholar]

- Keller H, Yovsi R, Borke J, Kärtner J, Henning J, & Papaligoura Z. (2004). Developmental consequences of early parenting experiences: Self-recognition and self-regulation in three cultural communities. Child Development, 75, 1745–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger AC, & Tomasello M. (1996). Cultural learning and learning culture. In Olson DR & Torrance N. (Eds.), The handbook of education and human development: New models of learning, teaching, and schooling (pp. 369–387). Malden, MA: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lancy DF, Bock J, & Gaskins S. (2010). The anthropology of learning in childhood. Lanham, MD: AltaMira. [Google Scholar]

- Lave J, & Wenger E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Legare CH, & Harris PL (2016). Introduction to the ontogeny of cultural learning. Child Development, 87, 633–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legare CH, & Nielsen M. (2015). Imitation and innovation: The dual engines of cultural learning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19, 688–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeVine R. (1980). A cross-cultural perspective on parenting. In Fantini MD & Cardenas R. (Eds.), Parenting in a multicultural society (pp. 17–26). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- LeVine R, LeVine S, Schnell-Anzola B, Rowe M, & Dexter E. (2012). Literacy and mothering. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levine R, Martinez T, Brase G, & Sorenson K. (1994). Helping in 36 U.S. cities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Little EE, Carver LJ, & Legare CH (2016). Cultural variation in triadic infant–caregiver object exploration. Child Development, 87, 1130–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machluf K, & Bjorklund DF (2015). Social cognitive development from an evolutionary perspective. In Zeigler-Hill V, Welling LLM, & Shackelford TK (Eds.), Evolutionary perspectives on social psychology (pp. 27–37). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Mani A, Mullainathan S, Shafir E, & Zhao J. (2013). Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science, 341, 976–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medin D, Waxman S, Woodring J, & Washinawatok K. (2010). Human-centeredness is not a universal feature of young children’s reasoning: Culture and experience matter when reasoning about biological entities. Cognitive Development, 25, 197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meins E, Fernyhough C, Wainwright R, Das Gupta M, Fradley E, & Tuckey M. (2002). Maternal mind-mindedness and attachment security as predictors of theory of mind understanding. Child Development, 73, 1715–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PJ, & Goodnow JJ (1995). Cultural practices: Toward an integration of culture and development. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 67, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M. (2012). Imitation, pretend play, and childhood: Essential elements in the evolution of human culture? Journal of Comparative Psychology, 126, 170–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M, & Haun DB (2016). Why developmental psychology is incomplete without comparative and cross-cultural perspectives. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 371. 10.1098/rstb.2015.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett RE, & Miyamoto Y. (2005). The influence of culture: Holistic versus analytic perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9, 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto H, & Keller H. (2014). Different faces of attachment: Cultural variation on a universal human need. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Proffitt JB, Coley JD, & Medin DL (2000). Expertise and category-based induction. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 26, 811–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff B, Mistry J, Göncü A, & Mosier C. (1993). Guided participation in cultural activity by toddlers and caregivers. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 58(4–8). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross N, Medin D, Coley JD, & Atran S. (2003). Cultural and experiential differences in the development of folkbiological induction. Cognitive Development, 18, 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley SJ, & Camacho TS (2015). Increasing diversity in cognitive developmental research: Issues and solutions. Journal of Cognition and Development, 16, 683–692. [Google Scholar]

- Scribner S, & Cole M. (1973). Cognitive consequences of formal and informal education. Science, 82, 553–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpell R. (1976). Culture’s influence on behaviour. London: Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Shweder RA (1990). Cultural psychology—What is it? In Stigler JW, Shweder RA, & Herdt G. (Eds.), Cultural psychology: Essays on comparative human development (pp. 1–43). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slade A. (2005). Parental reflective functioning: An introduction. Attachment & Human Development, 7, 269–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Super CM, & Harkness S. (1986). The developmental niche: A conceptualization at the interface of child and culture. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 9, 545–569. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli K. (2003). “Dit is die Here se Asem”: The wind, its messages, and issues of auto-ethnographic methodology in the Kalahari. Cultural Studies M Critical Methodologies, 3, 397–428. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli K. (2005). Where global contradictions are sharpest: Research stories from the Kalahari. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Rozenberg. [Google Scholar]

- van Schaik CP, & Burkart JM (2011). Social learning and evolution: The cultural intelligence hypothesis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 366, 1008–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Votruba-Drzal E, Miller P, & Coley RL (2016). Poverty, urbanicity, and children’s development of early academic skills. Child Development Perspectives, 10, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. (2017). Five myths about the role of culture in psychological research. Retrieved from: Observer. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/five-myths-about-the-role-of-culture-in-psychological-research#.WQu4GcJAT5o. [Google Scholar]

- Weis L. (1995). Identity formation and the process of “othering”: Unraveling sexual threads. Educational Foundations, 9, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting BB, & Whiting JWM (1975). Children of six cultures: A psycho-cultural analysis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]