Abstract

Mounting evidence suggests that endorsement of psychological continuity and the afterlife increases with age. This developmental change raises questions about the cognitive biases, social representations, and cultural input that may support afterlife beliefs. To what extent is there similarity versus diversity across cultures in how people reason about what happens after death? The objective of this study was to compare beliefs about the continuation of biological and psychological functions after death in Tanna, Vanuatu (a Melanesian archipelago), and the United States (Austin, Texas). Children, adolescents, and adults were primed with a story that contained either natural (non-theistic) or supernatural (theistic) cues. Participants were then asked whether or not different biological and psychological processes continue to function after death. We predicted that across cultures individuals would be more likely to endorse the continuation of psychological processes over biological processes (dualism) and that a theistic prime would increase continuation responses regarding both types of process. Results largely supported predictions; U.S. participants provided more continuation responses for psychological than biological processes following both the theistic and non-theistic primes. Participants in Vanuatu, however, provided more continuation responses for biological than psychological processes following the theistic prime. The data provide evidence for both cultural similarity and variability in afterlife beliefs and demonstrate that individuals use both natural and supernatural explanations to interpret the same events.

Keywords: Afterlife beliefs, Cognitive science of religion, Conceptual development, Cross-cultural comparison, Death concepts, Dualism, Explanation, Explanatory coexistence, Naïve biology, Naïve psychology, Religious cognition, Supernatural cognition, Supernatural reasoning, Vanuatu

1. Introduction

All individuals must eventually confront the inevitability and finality of death. When asked to explain what happens after a person dies, individuals often incorporate both natural and supernatural explanations, indicating that while the body may die, the mind, or spirit, continues (Legare, Evans, Rosengren, & Harris, 2012). This may be because the biological consequences of death are readily apparent, whereas the psychological consequences of death are more difficult to imagine (Astuti & Harris, 2008; Brent & Speece, 1993; Harris & Giménez, 2005). Recent research indicates an increasing endorsement of psychological continuity and the afterlife across development (Harris, 2011). This age change raises questions about the cognitive biases and the social representations that support afterlife beliefs.

This study was conducted in Austin, Texas, United States, and Tanna, Vanuatu. Tanna is an island in the Melanesian archipelago of Vanuatu. Our objective was to compare the development of beliefs about what happens to the body and the mind after death across two populations that vary in theoretically relevant ways. In contrast to the population we studied in the United States, Tanna has an emerging market economy and the majority of the population engages in subsistence agriculture. Tanna was also relatively recently converted to Christianity. Examining afterlife beliefs both developmentally and cross-culturally can provide novel insight into the way that variation in cultural input may affect the development of afterlife beliefs. For example, cultural groups vary dramatically in exposure to and endorsement of religious beliefs and in the amount of first-hand experience with death in the animal and human world. We used both closed- and open-ended interviews to examine whether intuitive, dualistic thinking (i.e., endorsing the continuation of psychological processes over biological processes after death) is common in both cultural contexts.

We also examined the extent to which individuals in each population use both natural and supernatural explanations for death. Natural explanations are defined as those that appeal to empirically verifiable phenomena, and supernatural explanations as those that appeal to phenomena that are not empirically verifiable and are distinct from natural phenomena (Legare et al., 2012). We first review the literature on intuitive dualism followed by a review of how context may affect the development of afterlife beliefs. We also discuss how people reason about death from both a natural and a supernatural perspective across development, often adopting both perspectives to explain the death of a given individual. Finally, we describe the populations we studied and our research questions and predictions for this study.

1.1. Intuitive dualism

Previous research has characterized humans as “intuitive dualists”—differentiating the physical body from the non-physical mind (sometimes conceptualized as a “soul”) and privileging the continuation of mind over body following death. As Bloom (2004) noted, “we do not feel as if we are bodies, we feel as if we occupy them” (p. 191). Individuals may endorse the continuation of psychological functions over biological functions following death because they use different cognitive systems for reasoning about physical bodies (naïve physics and naïve biology) as compared to psychological states (naïve psychology) (Bloom, 2004).

Empirical evidence shows that children, especially older children, believe that biological functions cease at death but that psychological functions may persist (Bering, 2006; Bering & Bjorklund, 2004). Bering (2006) argues that the core reason humans exhibit intuitive dualism is because we frequently observe the cessation of biological processes but find it hard to imagine the cessation of mental processes such as thinking. For example, when a loved one or a pet dies, we can readily observe that the body is no longer functioning. In contrast, the cessation of unobservable mental processes is not as easily inferred. Two predictions follow from this proposal: (a) a dualistic conception of death should emerge early, with little or no cultural learning; (b) as children get older and continue to consolidate their biological understanding of death and its pervasive consequences, their dualistic conception of death should wane and individuals should endorse the complete cessation of function more frequently (Bering, 2006; Bering & Bjorklund, 2004).

The dualism hypothesis has spurred much research on afterlife beliefs, but there are reasons to question its plausibility (Harris, 2011; Hodge, 2008, 2011). The implications of intuitive dualism are at odds with many funerary rites, mythology, iconography, and religious doctrine. In many religious doctrines, such as that of the Egyptians, classical Greeks, Christians, and Muslims, the body is an integral part of personhood. It is regarded as essential for experience in the afterlife and for resurrection (Hodge, 2008). Research on concepts of reincarnation has also found that the continuity of physical marks is a key component for accepting that someone is indeed the reincarnation of a deceased person (White, 2016). Contrary to Bering, Hodge (2011) argues that our “offline social reasoning” system, rather than any propensity toward dualism, accounts for beliefs in the afterlife across cultures and history. Because we can think about our social partners even when they are absent, we think of them as embodied persons who still exist somewhere in time and space even when they die.

1.2. The effects of context on afterlife beliefs

Priming a religious as opposed to a biological conception of death increases participants’ endorsement of the continuation of both psychological and biological processes. Thus, in Spain (Harris & Giménez, 2005) and Madagascar (Astuti & Harris, 2008), participants were presented with a narrative that highlighted either the religious or the biological aspects of a person’s death. An effect of narrative context emerged in both studies. When primed with a religious narrative about death, participants were more likely to endorse the continuation of bodily and mental processes following death than when primed with a biological narrative.

Overall, older children and adults tend to display two conceptions of death—death as a biological endpoint and death as the beginning of an afterlife. With age, these natural and supernatural beliefs about death increasingly coexist within the minds of individuals, and each type of belief is recruited to explain the sequelae of any given individual death (Evans, Legare, & Rosengren, 2010; Legare & Gelman, 2008; Legare et al., 2012). Thus, biological explanations are often provided to explain the cessation of life on Earth, whereas religious explanations are often provided to explain the continuation of life in the afterlife (Harris, 2011).

The results of Astuti and Harris (2008) and Harris and Gimenez (2005) do not support the predictions of the intuitive dualism hypothesis. First, young children were equally likely to endorse the continuation of biological processes and psychological processes. Second, Astuti and Harris (2008) found that children and adults were likely to incorporate both natural and supernatural explanations for death. Natural explanations did not supplant supernatural explanations with age. Third, the results indicate that enculturation plays a role in the development of afterlife beliefs. Even if concepts of an afterlife are ubiquitous across different cultures, the form that these concepts ultimately take is likely to be dependent on the cultural context (Astuti & Harris, 2008).

Previous cross-cultural research has examined the development of afterlife beliefs in the United States (Bering & Bjorklund, 2004) and in Spain (Harris & Giménez, 2005), where Christian beliefs predominate, and in Madagascar (Astuti & Harris, 2008), where beliefs about obligations to the ancestors regulate everyday life as well as ritual practices (Astuti, 2011). Afterlife beliefs have yet to be examined in a cultural context that maintains indigenous supernatural beliefs but also increasingly embraces Christian doctrine. This study was conducted in such a context.

1.3. Field sites

1.3.1. Tanna, Tafea Province, Vanuatu

Vanuatu, a Melanesian island nation in the South Pacific, is one of the most remote, culturally and linguistically diverse, and understudied countries in the world (Norton, 1993). It consists of 65 different islands, each with villages that speak their own languages and maintain distinct cultural traditions. The nation of Vanuatu was formed in 1980 after gaining independence from the Condominium of the New Hebrides (British and French joint government established in the early 1900s) (Gregory & Gregory, 2002). There are three national languages of Vanuatu: English, French, and Bislama, a mix of English and French. Our sample predominately spoke Bislama and English (as well as a variety of local languages).

Tanna is one of the larger islands located in the Tafea province of Vanuatu with approximately 30,000 inhabitants and was selected for this research for several reasons. Although most people on Tanna are not old enough to remember the early missionary efforts on the island, they are still navigating the tension between their traditional beliefs and the continued influx of Christianity and formal schooling initiated by the missionaries. Much of the population was converted to Presbyterianism between 1910 and 1930. However, during World War II, the John Frum Cargo Cult emerged. Part of the message of this cult was that people should leave the churches and return to their customary ways of life and, in return, they would receive cargo (Gregory & Gregory, 2002). Thus, despite the influence of Presbyterianism on the island, many villages have maintained kastom (custom), or “ancestrally enjoined rules for life” (Keesing, 1982, p. 360). In a recent survey of national identity in Vanuatu, maintaining kastom, as well as being Christian were considered two of the most important aspects of what it means to be from Vanuatu (Clarke, Leach, & Scambary, 2013). Based on interview data conducted in Tanna (Watson-Jones, Busch, & Legare, 2015), participants in Vanuatu often adopt a literal interpretation of Christian scripture, a stance that is common in other parts of Melanesia, such as Papua New Guinea (Robbins, Schieffelin, & Vicala, 2014). For example, when asked about the origins of humans, many participants indicated, “God created everything,” and “Because of Adam and Eve, God created first day, second day, and then animals” (Watson-Jones et al., 2015).

The concept of “rebirth” or “resurrection” is common to many Christian denominations, including Presbyterianism. Rebirth is the belief that bodies will be raised from the grave at the time of Final Judgment. In many Christian writings about heaven and hell, disembodied “souls” are often discussed as evincing states that typically require a body, such as being thirsty as well as seeing and hearing things. These ideas date back to the influential medieval writings of Thomas Aquinas, who viewed the body and soul as integrated and interdependent. Indeed, there is a tension in the writings of Aquinas between the idea of a soul separate from the body following death and the reconstitution of the body at resurrection (Van Dyke, 2014). The idea that the afterlife involves some form of embodied personhood is woven throughout much Christian ideology. The Apostles’ Creed, for example, an early Christian statement still used by many Christian denominations, speaks of Jesus seated at the right hand of God, the resurrection of the body, and the life everlasting. Thus, it is possible that given a literal interpretation of Christian doctrine, individuals may not display the pattern of intuitive dualism repeatedly found in previous research.

Consider the Urapmin of Papua New Guinea (also in Melanesia) as an example of how evangelical Christian conversion can shift pre-existing cultural scripts. For the Urapmin, the body was once regarded as a key component of the social connection between the self and others, whereas the heart and emotions were interior and private. Christian conversion inverted this relationship and required Urapmin to relate to others through “shared thoughts and feelings” (the heart), rather than through the body and kinship (Robbins et al., 2014, p. 584). Examining concepts of the afterlife in a culture that still adheres in many ways to indigenous beliefs while integrating and embracing Christian doctrine, such as found in Tanna, will provide insight into how shifting cultural scripts can influence beliefs about what happens to people when they die.

Formal, Western-style education is also a relatively recent institution on Tanna. Missionaries set up what they called schools in the early 1900s (Gregory & Gregory, 2002). There was, however, no standard curriculum until the last three decades when Britishand French-run schools began providing primary and secondary education (Peck & Gregory, 2005). In addition, parents in Tanna often have to pay to send their children to school, and children from kastom villages have only recently begun to attend. Most children spend time in similar-aged peer groups or helping their parents with the family gardens and/or tending domesticated animals. On Tanna, people live primarily from subsistence agriculture (Cox et al., 2007) and some hunting of fruit bats and fishing. Thus, children in Tanna live “close” to nature (Unsworth et al., 2012) and often have first-hand experience with the biological consequences of death. For example, they are likely to be observers of, or participants in, coastal fishing practices, pig husbandry, and the hunting of flying foxes. At particular ceremonies, such as circumcision, children witness the public slaughter of cows and pigs used in exchanges between the maternal and paternal families of the newly circumcised child. This gives children in a Tanna a firsthand experience of what happens to the body after death.

1.3.2. Austin, Texas, United States

Austin, Texas, is a culturally diverse university city in the American Southwest with a population of 842,592 inhabitants. Although the socioeconomic status of Austin residents is highly variable, the city is representative of the most economically robust and highly educated populations in the United States. Broadly speaking, the childrearing environments in Austin, Texas, are representative of a wide range of Western educated, middleclass caregiving practices. Whereas Austin is technically part of the “Bible Belt,” it is known for its political and social liberalism and the diversity of its population. In 2010, the U.S. Census Bureau reported that 48% of Austin citizens identified as White, 35% identified as Hispanic/Latino, 8% identified as African American, and 6% identified as Asian American. In 2011 the total population of Austin when combined with nearby Round Rock was 1,654,442. Of that number, 28% speak a language other than English in the home (79% Spanish, 10% other Indo-European languages; 10% Asian and Pacific Island languages; 1% Other). According to http://www.city-data.com/city/Austin-Texas.html, 46.2% of Austin residents report being affiliated with a religious congregation. Among such affiliated residents, 44% identify as Catholics, 20.6% as Baptist, 5.9% as Methodist, 3.6% as Jewish, 3.5% as Episcopalian, 3.1% as Evangelical, 2.8% as Presbyterian, 2.4% as Lutheran, 2.1% as Church of Christ, and 11.7% as other.

Living in a market economy, most participants in Austin have little direct interaction with the natural world as a vital source of food (Busch, Watson-Jones, & Legare, under review). Most residents of Austin procure their food from grocery stores and relatively few hunt for food (as compared to Vanuatu). Accordingly, children in Austin are less likely to have any first-hand encounter with death and its biological consequences.

1.4. Current study

Our research questions were as follows: (a) To what extent is there similarity versus diversity across two cultures in how people reason about what happens after death? (b) Do natural and supernatural concepts of death coexist in both cultures? To address these questions, we used a methodology adapted from Harris and colleagues (Astuti & Harris, 2008; Harris & Giménez, 2005). Participants heard about the death of a character in a narrative that included either a natural prime (which we will call “non-theistic”) or a supernatural prime (which we will call “theistic”). We chose these two types of primes based on previous research. The non-theistic prime presented participants with a familiar scenario of receiving treatment when sick. It served as a contrast to the theistic prime in which cues to the afterlife were present. The primes were designed to create a clear narrative context (either theistic or non-theistic) for presenting the subsequent questions about the continuation of biological and psychological processes. In this way, we aimed to assess the malleability of afterlife concepts. After listening to either narrative, participants were asked a series of 14 closed-ended questions about the continuation or non-continuation of specific biological and psychological processes, followed by three questions about the continuation or non-continuation of “whole entity” processes (the body, the mind, and the spirit).

We predicted that participants in both cultural groups would provide more “still works” responses when primed with a theistic rather than a non-theistic narrative. We also predicted that in both settings, participants would provide more “still works” responses for psychological processes than for biological processes. However, we anticipated an important cultural difference in such dualistic thinking. To the extent that Christian converts in Vanuatu believe in the resurrection of the body, we predicted that participants in Vanuatu would endorse the continuation of biological as well as psychological processes after death.

Finally, in both settings we examined the coexistence of natural and supernatural reasoning about afterlife beliefs. Recent cross-cultural research has documented that, across diverse cultures, children and adults invoke natural as well as supernatural explanations to interpret the same event. Thus, they do not opt for one form of explanation to the exclusion of the other (see Legare et al., 2012, for a review). To examine how far individuals invoke both supernatural and natural explanations in thinking about death, participants were asked to explain their answers concerning the continuation or non-continuation of function, using an open-ended format. We predicted that even if natural explanations were more prevalent following the non-theistic prime and supernatural explanations were more prevalent following the theistic prime, many participants would nevertheless produce a mix of natural and supernatural explanations.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants in the United States and Vanuatu were divided into three age groups, children (7- to 12-year-olds), adolescents (13- to 18-year-olds), and adults (19- to 70-year-olds). Across the two sites, a total of N = 228 individuals participated in the study (eighty-seven 7- to 12-year-olds, sixty-two 13- to 18-year-olds, and seventy-nine adults).

2.1.1. Austin, Texas, United States

One-hundred-fourteen individuals participated in the United States (forty-four 7- to 12-year-olds, twenty-nine 13- to 18-year-olds, and forty-one adults). Fifty-seven individuals received the non-theistic prime (twenty-two 7- to 12-year-olds, forty 13- to 18-year-olds, and twenty-one adults). Fifty-seven individuals received the theistic prime (twenty-two 7- to 12-year-olds, fifteen 13- to 18-year-olds, and twenty adults). American children were recruited for the study through the birth records at a research university as well as from a local children’s museum in Austin, Texas. Participants recruited through birth records completed the study on the university campus or in a quiet office within a children’s museum. Adolescents were recruited through the birth records and completed the study on the university campus. Adults completed the study in a room on the university campus. The ethnicity of the sample was 54% Caucasian/European American, 19% Latino, 5% Asian American, 4% African American, 4% multiracial, 3% other, and 2% South Asian. Of the 111 U.S. participants who indicated their religion, 80 identified as religious and 29 identified as not religious (15% Agnostic, 11% Atheist, 3% Buddhist, 34% Catholic, 1% Hindu, 4% Jewish, 2% Muslim, 25% Protestant, 5% other), and 2 declined to report their religion.

2.1.2. Tanna, Tafea Province, Vanuatu

One hundred and fourteen individuals participated in Vanuatu (forty-three 7- to 12-year-olds, thirty-three 13- to 18-year-olds, and thirty-eight adults). Fifty-seven individuals received the non-theistic prime (twenty 7- to 12-year-olds, sixteen 13- to 18-year-olds, and twenty-one adults). Fifty-seven individuals received the theistic prime (twenty-three 7- to 12-year-olds, seventeen 13- to 18-year-olds, and seventeen adults). Child participants in Vanuatu were recruited from two primary schools in the city of Lenakel on the island of Tanna. Ninety-eight percent of the sample in Tanna identified as Presbyterian and 2% identified as Baha’i. Participants completed the study in an unused classroom on the school grounds or in the school library, away from their classmates. The participants in Vanuatu did not receive any direct compensation for their participation due to local customs surrounding gift giving. However, the schools of the participants were provided with school supplies to express our gratitude. Adolescents from Vanuatu were recruited from a secondary school in the same city. Participants completed the study in a separate room on the grounds of the school, apart from other students. As with child participants, adolescent participants were not directly compensated for participation, but we provided school supplies to the school as reciprocation. Adults were recruited in the markets and neighborhoods in the city of Lenakel. Participants typically completed the study in a secluded area near where they were approached by the researchers.

2.2. Materials and procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two between-subjects conditions, one that primed naturalistic reasoning (non-theistic) and one that primed supernatural reasoning (theistic).

2.2.1. Priming

In both priming conditions, participants either read, or were read, a short vignette by the researcher about an elderly man named David who passes away. The non-theistic priming vignette focused on the biomedical aspects of the man’s death, namely that he went to the doctor for treatment yet still dies:

I know a person named David. He worked very hard all the time. And one day when it was very hot, he had a stroke. His children and wife took him to the hospital, where he was given four shots. Nonetheless, after 3 days from the time he arrived at the hospital he died. And the questions that I am going to ask you are about him, now that he is dead.

The theistic priming vignette focused on the man’s relationships with his family and God, notably that his family carried out his funeral and that he is now with God

I know a person called David. He had many children and grandchildren. On the day when he died, many of his grandchildren were with him in his house. David’s family carried out the funeral well and his children and grandchildren are happy that this is so. David is now with God. And the questions I am going to ask you are about David, now that he is with God.

2.2.2. Questions

After reading, or being read, the vignette, participants were presented with a total of 17 yes/no questions about the continuation of various biological and psychological processes after death. The two prime conditions differed in the way each question was framed. Following the non-theistic prime, each question was framed as “Now that David is dead …” whereas following the theistic prime, each question was framed as “Now that David is with God …” The questions were arranged into two different random orders to allow us to control for order effects (because the U.S. adults completed the study using an online survey system, the questions were randomized for this sample). Following Astuti and Harris (2008), of the seventeen questions, seven asked participants about the continuation of biological or bodily processes, seven asked about the continuation of psychological or mental processes, and three questions asked participants about the continuation of the functions of the body as a whole, the mind as a whole, and the spirit (see Table 1 for the seven biological process questions and the seven psychological process questions). Following each yes/no response, participants were asked to provide an explanation of why they thought that would be the case.

Table 1.

List of biological and psychological process questions

| Biological | Psychological |

|---|---|

| Do his eyes work or not? | Does he see things or not? |

| Do his ears work or not? | Does he hear when people talk or not? |

| Do his legs move or not? | Does he feel hungry or not? |

| Does his heart beat or not? | Does he feel cold or not? |

| Does his stomach need food or not? | Does he remember where his house is or not? |

| Does a cut on his hand heal or not? | Does he know his wife’s name or not? |

| Does he get old or not? | Does he miss his children or not? |

2.2.3. U.S. children and adolescents

Participants completed the study in a quiet room on the campus of a large research university one-on-one with a trained researcher. After obtaining informed parental consent, participants were taken to a study room. All participants were video and audio recorded. Once the participants felt comfortable interacting with the experimenter, they were told that they would be read a short story and then asked some questions about it. Participants were reassured that there were no right or wrong answers to the questions, and that we were simply interested in knowing their opinions. The researcher then proceeded to read the vignette to the participants and asked the 17 yes/no questions. After participants answered each question, the researcher prompted the participants to explain their yes/no reply by asking “Why?” The study concluded when participants had answered all 17 questions, at which point participants and their parents were debriefed, thanked, and provided compensation (a small toy or snack) for their participation.

2.2.4. U.S. adults

Participants completed the study in a quiet room on campus. After consenting to the study, the researcher explained that the study would be completed on the computer and the participants should read all the instructions carefully and notify the researcher if they had any questions. The researcher reassured the participants that there were no right or wrong answers, directed them to a laptop, and left the room. Participants then independently read the priming vignette and answered the questions online using Qualtrics online survey software. U.S. adults were not video recorded because all of their responses were immediately coded through the Qualtrics software. Upon completing the study, participants were debriefed, thanked, and provided with compensation (credit in the Introduction to Psychology course).

2.2.5. Vanuatu

All participants in Vanuatu completed the study one-on-one with a trained research assistant. Research assistants were native Bislama speakers and conducted the study in Bislama, one of the official languages of Vanuatu. All participants were video and audio recorded for later coding. Once participants felt comfortable interacting with the research assistant, they were told they were going to be read a short story and then asked some questions about it. Participants were reassured that there were no right or wrong answers to the questions, and we were just interested in their opinions. The research assistant then read the appropriate priming vignette to the participant and asked the 17 questions. After providing their yes/no response to each of the 17 questions, the experimenter prompted participants to explain their response by asking “Why?” After completing the study, the participants were debriefed and thanked. No direct compensation was given to participants in Vanuatu.

2.3. Coding

2.3.1. Entire set of process questions (seven biological, seven psychological)

Participants provided “yes,” “no,” and “maybe” responses to each of the process type questions. “Yes” was coded as still works = 1, “no” was coded as does not work = 0, and “maybe” was coded as 0.5. To compare responses to the biological and psychological questions, summary scores out of 7 were created for each process type across participants. We decided to only include analyses of the 14 process questions because analyses of the three whole-entity questions (body, mind, and spirit) added no new information to the overall pattern of results.

2.3.2. Open-ended responses to the “why” questions

We created two broad categories for coding responses to the open-ended “why” question asked after each of the 14 process questions: “natural” and/or “supernatural.” Explanations were placed into these categories based upon an initial detailed coding using the five coding categories developed by Harris and Gimenez (2005).

2.3.2.1. Natural categories:

NO MOVEMENT:

Explanations referring to a lack of movement or action. “Because he is dead and he can’t move” “Because he is still,” “Because if he is dead his legs can’t move.”

MEDICAL-BIOLOGICAL:

Explanations referring to specific internal organs and substances. “Because his heart doesn’t work, his muscles don’t work.” “Cells are shutting down.” “His brain and heart aren’t working and they control his legs.”

END OF LIFE:

Explanations asserting that death is the end of life or the end of functioning. “Because he is dead and so none of his body parts work.” “Because he’s not alive.”

DECAY:

Explanations referring to the decay of the body after death. “His human body is no longer available. It is decomposing in the ground.” “He’s decaying.”

DEAD/BURIED:

Explanations that only referred to death or burial with no further elaboration: “Because he is dead” “He is inside the ground.”

2.3.2.2. Supernatural categories:

GOD-HEAVEN:

Explanations asserting that being with God or in heaven enable the person, the body, or the mind to continue to function. “He is with God.” “He prayed and God is helping him to move.” “In heaven, he can walk.”

PARTS:

Explanations asserting that there is a part of the mind or the body—or some special entity such as a spirit, soul, lighter being, or consciousness—that continues functioning or lives on even if other parts cease to function: “He’s dead, his spirit goes up and works.” “He’s walking as a spirit.”

We also included an UNINFORMATIVE category: unclassifiable or “don’t know” answers.

Based upon this initial coding, explanations were categorized as “natural” if they fell into the “no movement,” “medical-biological,” “end of life,” “decay,” or “dead-buried” categories. Explanations were coded as “supernatural” if they fell into the “God-heaven” or “parts” categories. Note that any given explanation could be coded as both natural and supernatural if it included both kinds of information. Individuals were then classified as providing consistently natural explanations, consistently supernatural explanations, or mixing both natural and supernatural explanations across vignettes.

When there was a discrepancy or ambiguity between the closed-ended and open-ended responses, the closed-ended responses were interpreted in light of the open-ended responses. For example, in response to the question, “Does he miss his children or not?” many participants in both the United States and Vanuatu replied “no,” but when asked why he did not miss his children, they indicated that he would not be concerned with worldly matters when he was with God, or that “he would not miss them because he knows that he will see them soon.” In these cases, the closed-ended response was recoded as 0.5 to reflect this ambiguity.

Finally, to examine the extent of coexistence reasoning that individual participants employed within the interviews, participants were classified as providing consistently natural explanations (providing only natural explanations for their answers), consistently supernatural explanations (providing only supernatural explanations for their answers), or mixed responses (providing natural and supernatural explanations for different questions).

2.4. Inter-rater reliability

Three research assistants coded the open-ended explanations, and a fourth research assistant independently coded the entire dataset for inter-coder reliability. Their judgments were largely in agreement (Cohen’s kappas = 0.77–0.95) for each of the openended explanations for process type questions.

3. Results

3.1. Overview

We present the findings in two sections. First, we analyze “still works” responses to the two sets of process questions (i.e., “still works” responses to the seven biological and seven psychological process questions) across primes, cultures, and age groups. Next, to examine how far supernatural and natural concepts of death coexist, we analyze the pattern of explanations given in reply to the open-ended “why” questions (i.e., analyses of natural and supernatural explanations for the entire set of process questions (seven biological, seven psychological) across primes and cultures.

3.1.1. Responses to the two sets of process questions: Is there cross-cultural similarity or variation in how people reason about what happens after death?

Preliminary analyses revealed no effect of counterbalanced scripts (two randomized orders of presentation of the process-type questions) on responses, F(1, 184) = 2.36, p = .126.

A repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on “still works” replies to the process questions with age group (3: children, adolescents, adults), prime (2: non-theistic, theistic), and country (2: Vanuatu, United States) as between-subjects variables, and process type (2: biological, psychological) as the within-subjects variable. This analysis revealed no main effect of age or country. There was a large main effect of prime, F(1, 214) = 140.91, p = .0001, η2p = 0:397. Participants who received the theistic prime provided more “still works” responses (M = 3.31, SE = 0.137) than participants who received the non-theistic prime (M = 0.98, SE = 0.140). There was also a main effect of process type, F(1, 214) = 26.01, p = .0001, η2p = 0:108. Participants provided more “still works” responses for the psychological (M = 2.43, SE = 0.118) than for the biological process questions (M = 1.86, SE = 0.106). However, this main effect of process type should be interpreted in light of the significant interaction between age group and process type, F(2, 214) = 7.52, p = .0005, η2p = 0:049. Although adolescents and adults differentiated between biological and psychological processes, children did not. Thus, children provided just as many “still works” responses for psychological processes (M = 2.25, SE = 0.190) as for biological processes (M = 2.19, SE = 0.170), p = .709. In contrast, adolescents provided more “still works” responses for psychological (M = 2.80, SE = 0.226) than for biological processes (M = 1.89, SE = 0.202), p = .0001, and the same pattern was found for adults (psychological: M = 2.24, SE = 0.198; biological: M = 1.51, SE = 0.178), p = .0001.

There were three additional two-way interactions: a country by prime interaction, F(1, 214) = 5.89, p = .016, η2p = 0.027, a prime by process type interaction, F(1, 214) = 12.15, p = .001, η2p = 0.054, and a country by process type interaction, F(1, 214) = 34.62, p = .0001, η2p = 0.139. These three two-way interactions were qualified by the three-way interaction of country by prime by process type, F(1, 214) = 26.40, p = .0001, η2p = 0:110.

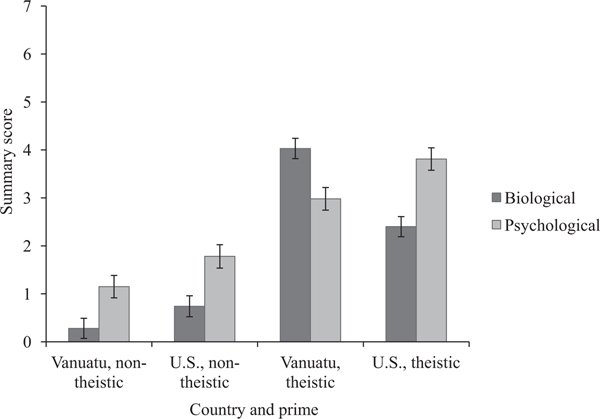

This three-way interaction is illustrated in Fig. 1. As noted earlier, participants typically provided more “still works” responses when discussing psychological rather than biological processes. However, inspection of Fig. 1 shows that this pattern did not emerge consistently. More specifically, it did not emerge when participants from Vanuatu received the theistic prime. To check these conclusions, we examined the simple effect of process type for each of the four combinations of country and prime. These tests confirmed that when given the non-theistic prime, participants in Vanuatu provided more “still works” responses for psychological (M = 1.15, SE = 0.234) than biological processes (M = 0.28, SE = 0.210), F(1, 214) = 15.74, p = .0001, η2p = 0:069, as did U.S. participants (M = 1.78, SE = 0.244; M = 0.74, SE = 0.219), F(1, 214) = 20.46, p = .0001, η2p = 0.087. However, when given the theistic prime, Vanuatu participants showed the opposite pattern. They provided more “still works” responses for biological (M = 4.03, SE = 0.211) than for psychological processes (M = 2.98, SE = 0.235), F(1, 214) = 22.51, p = .0001, η2p = 0:095, whereas U.S. participants again provided more “still works” responses for psychological (M = 3.81, SE = 0.234) than for biological processes (M = 2.40, SE = 0.210), F(1, 214) = 40.89, p = .0001, η2p = 0:160.

Fig. 1.

Summary scores of “still works” responses for the biological and psychological processes by country and prime. Error bars represent SE.

In summary, the analysis produced three clear findings. First, it revealed considerable stability in the pattern of responding across the two cultures. In both cultures, “still works” responses were more frequent following the theistic prime than the non-theistic prime. Second, in both cultures, and consistent with earlier evidence for the emergence of dualistic thinking with age, older participants—adolescents and adults, but not children—were more likely to claim that psychological processes would continue after death than biological processes. Finally, there was one notable impact of culture. When Vanuatu participants were given the theistic prime, they did not display the customary pattern of dualistic thinking. Indeed, they were more likely to claim that biological processes would continue after death than psychological processes.

3.1.2. Responses to the open-ended “why” questions for the biological and psychological process questions: Is there cross-cultural stability or variation in the production and coexistence of natural and supernatural concepts of death?

In this section, we examine whether participants consistently provided one type of explanation (supernatural or natural) to the exclusion of the other or mixed the two types after having received a given narrative prime—either non-theistic or theistic. Table 2 provides examples of the kinds of explanations participants provided.

Table 2.

Examples of explanations provided by participants in the non-theistic and theistic priming conditions in both the United States and Vanuatu

| Do his legs still work? | Does he miss his children? | Does he feel hungry? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-theistic, Vanuatu | “No more organs that can work. No more blood to give him power to work.” | “He cannot do anything. The children will miss the Dad but he won’t miss them.” | “Because he is inside his coffin and he won’t breathe or eat.” |

| Theistic, Vanuatu | “He’s with God, God gives his legs power.” | “His spirit goes to God, maybe he thinks about his children.” | “There’s plenty of food in Heaven.” |

| Non-theistic, United States | “Because his dead brain can’t signal the dead muscles in his dead legs to move.” | “Feelings like missing someone are induced by the brain, which is no longer functioning.” | “He’s dead and the dead do not feel.” |

| Theistic, United States | “If legs were still a thing in the afterlife, then maybe he’d use them to walk around since there is supposed to be a new Earth.” | “He misses his children, but he is able to look down at them.” | “If he was hungry, he just would go to Heaven and they have a snack bar in there…” |

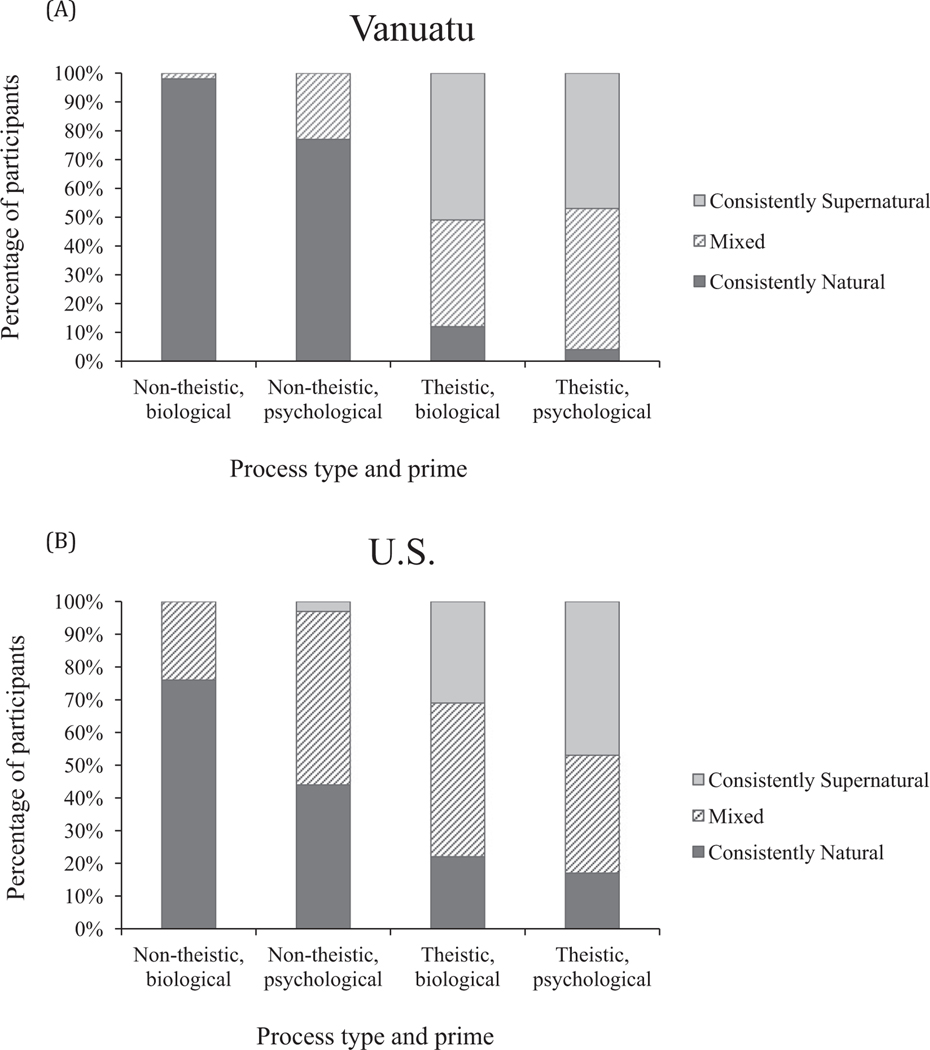

We classified individual participants as providing (a) consistently natural explanations; (b) consistently supernatural explanations; or (c), mixing natural and supernatural explanations across different questions. We classified participants’ patterns of responding for each of the two process types (biological and psychological) considered separately and also across the entire set of process questions. Fig. 2a shows the proportion of participants in Vanuatu who offered consistently natural, consistently supernatural, or a mix of both types of explanation for each of the four combinations of prime and process type. Fig. 2b shows the same data for U.S. participants.

Fig. 2.

(A) Percentage of Vanuatu participants classified as consistently natural, consistently supernatural, or mixed by process type and prime; (B) percentage of U.S. participants classified as consistently natural, consistently supernatural, or mixed by process type and prime.

Inspection of Fig. 2a and 2b reveals the potent effect of priming in both countries. Participants were more likely to produce consistently natural explanations following the nontheistic as compared to the theistic prime. Conversely, participants were more likely to produce consistently supernatural explanations following the theistic as compared to the non-theistic prime. Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests revealed that this priming effect emerged for biological processes in Vanuatu (p = .0001) and the United States (p = .0001). It also emerged for psychological processes in Vanuatu (p = .0001) and the United States (p = .039).

This pattern of justifications reinforces what was observed for participants’ judgments in reply to the “still works” questions. Thus, the non-theistic prime prompted participants to claim that biological and psychological processes would cease at death and to offer natural explanations for that cessation, whereas the theistic prime prompted participants to claim that biological and psychological processes would continue after death and to offer supernatural explanations for that continuation.

Figs. 2a and 2b also reveal differences in the way that participants thought about biological as compared to psychological processes. Following the non-theistic prime, McNemar tests revealed that participants in both locations were more likely to offer consistently natural explanations for biological processes than for psychological processes (United States, p = .0001; Vanuatu, p = .0001). Following the theistic prime, U.S. participants were marginally more likely to offer consistently supernatural explanations for psychological processes than for biological processes, p = .078. However, this difference did not emerge for participants in Vanuatu—who offered just as many supernatural explanations for biological processes as for psychological processes, p = .815. This latter pattern echoes what was observed for participants’ “still works” judgments. Recall that Vanuatu participants, unlike U.S. participants, did not claim that psychological processes would be more likely to continue after death than biological processes.

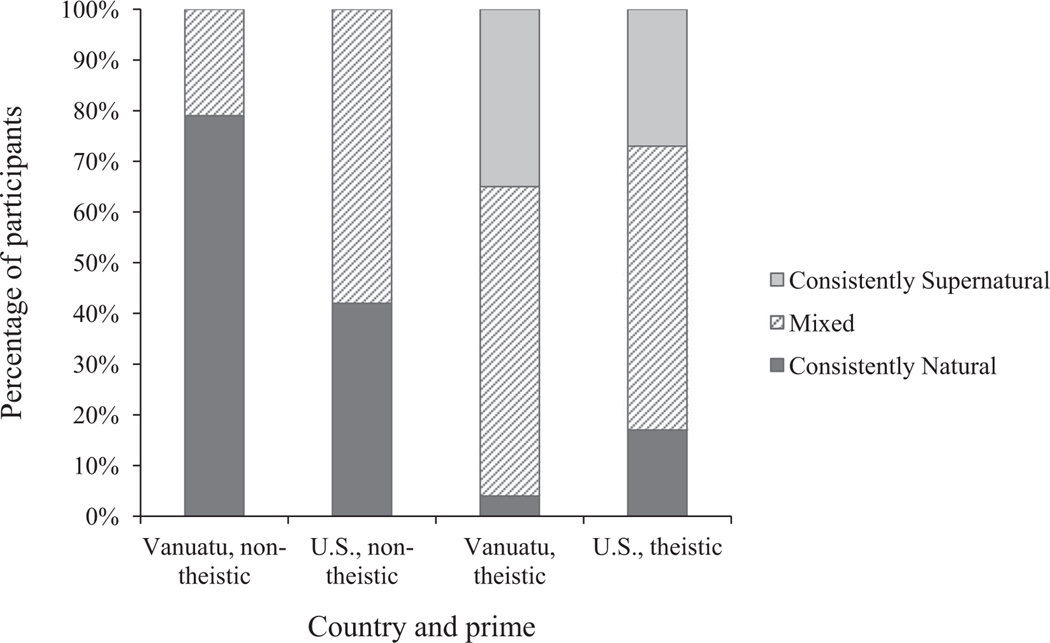

However, Figs. 2a and 2b also underline the limits of priming. More specifically, participants did not always produce an explanation that was consistent with the story prime. Following the non-theistic prime, some participants produced a mix of supernatural and natural explanations, especially with respect to psychological processes. Similarly, following the theistic prime a considerable proportion of participants produced a mix of supernatural and natural explanations. Indeed, a minority even produced consistently natural explanations. Collapsing across the entire sample, 35% of participants were classified as providing consistently natural, 16% as providing consistently supernatural, and 49% as mixing natural and supernatural explanations. Fig. 3 shows the distribution of these three patterns of explanation across the four combinations of country and prime.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of participants classified as consistently natural, consistently supernatural, or mixed by country and prime.

In sum, participants often produced a mixed pattern of explanation. Although they received a narrative prime with a potent impact—either a non-theistic prime that steered participants toward natural explanations or a theistic prime that steered them toward supernatural explanations—almost half of the participants invoked both forms of explanation in the course of the interview. By implication, both forms of explanation coexist in the minds of participants—one form of explanation is not invoked to the exclusion of the other.

4. Discussion

The findings of the current research offer a wide-ranging picture of afterlife beliefs across two cultures. Some of our results are consistent with previous work on afterlife beliefs. Overall, participants judged that biological processes cease in a more pervasive fashion at death than do psychological processes. However, some of our results were inconsistent with previous research. For example, we discovered that in Vanuatu, when primed with a supernatural narrative, participants provided more “still works” responses for biological processes than psychological processes. Thus, our results document both continuity and variation in reasoning across cultures.

We first review the main conclusions that have emerged, highlighting those that are consistent with earlier research as well as those that are discordant. We then consider their implications in more detail. To examine cross-cultural similarity and variation in the development of afterlife beliefs, participants in both countries were asked to judge whether a variety of biological and psychological processes cease or continue after death and to then explain their judgment. The pattern that emerged from these two different responses was quite consistent. Accordingly, in stating our conclusions, we emphasize both judgments and explanations.

Overall, participants judged that biological processes cease in a more pervasive fashion at death than do psychological processes. This dualistic pattern of thinking is consistent with earlier findings. Studies with participants in the United States (Bering, 2002; Bering & Bjorklund, 2004), in Spain (Bering, Hernandez-Blasi & Bjorklund, 2005; Harris & Gimenez, 2005) and in Madagascar (Astuti & Harris, 2008) have shown that participants are more likely to attribute an afterlife to mental as compared to bodily processes.

The current analyses also revealed a similar developmental pattern to that found in previous research (Astuti & Harris, 2008; Harris & Gimenez, 2005). Young children were just as likely to provide a “still works” response for a biological process as a psychological process. Adolescents and adults, however, tended to provide more “still works” responses for psychological processes than biological processes. This finding provides further support for the hypothesis that a dualistic conception of death emerges only after children have consolidated their understanding of the biological finality and inevitability of death, at which point, the possibility of an afterlife is likely to become more “cognitively salient” (Astuti & Harris, 2008, p. 735).

Participants in both cultures used two different conceptions of death—a biological conception in which death is seen as a terminus for living processes and a supernatural conception in which death is seen as a transition to the afterlife. Support for this conclusion emerged from the impact of the narrative prime. Participants listened to a narrative with either a non-theistic prime that included references to the medical and biological aspects of death or to a narrative with a theistic prime that included references to the afterlife. The effect of priming was pronounced in both the United States and Vanuatu and across a wide age range—from 7-year-olds to elderly adults. The non-theistic prime led participants to judge that most living processes would cease at death and to explain that cessation by invoking the biological aspects of death—immobility, organ dysfunction, bodily decay, and burial. In contrast, the theistic prime led participants to judge that various processes continue after death and to explain that continuity by invoking religious aspects of the afterlife—God, Heaven, and the soul.

Despite the strong effect of priming, participants did not, in the wake of a given prime, systematically adopt one conception of death to the exclusion of the other. Quite often, they invoked both conceptions. Thus, across countries and primes, nearly 50% of participants provided a mixed pattern of explanations, invoking both natural and supernatural explanations in the course of the interview. Despite the terminal impact of death from a biological perspective, they went on to explain the non-finality of death from a religious perspective—or vice versa. These findings replicate earlier results in Spain and Madagascar (Astuti & Harris, 2008; Harris & Gimenez, 2005). They extend those results by showing that participants provided a mixed pattern of explanations not just across biological and psychological processes but also within each type of process. Indeed, the findings reinforce the broader conclusion that explanations based on natural phenomena and explanations based on supernatural phenomena coexist in the minds of many participants (Legare & Gelman, 2008; Legare et al., 2012)—there is no evident tension or contention between the two modes of explanation.

As expected, there was an increase in “still works” responses for both psychological and biological processes following the theistic prime in both Vanuatu and the United States. The theistic prime, however, inverted the typical dualistic response pattern in Vanuatu. Participants judged that biological processes would be more likely to continue than psychological processes. This result was unexpected given previous findings, and it must be interpreted in light of current cultural identity in Vanuatu. Roughly 86% of a recent sample in Vanuatu indicated that “being Christian” was one of the most important aspects of being from Vanuatu (Clarke et al., 2013). Findings from semi-structured interviews indicated that the current sample from Tanna adopt a literal interpretation of scripture regarding what happens to a person following death, including being given “new life” in heaven and resurrection of the body (Watson-Jones et al., 2015). For example, following the theistic prime, some participants in Vanuatu offered responses such as “He went to Heaven, God has repaired his body,” and “He obeyed God and God makes his eyes work.”

Indeed, many adults from Tanna commented that mental processes such as remembering and negative emotions were not necessary in Heaven. At the same time, their reading of Christian scripture led them to expect some form of bodily resurrection. More specifically, the Presbyterian Church, including the Presbyterian Church of Vanuatu (PCV), affirms the Westminster Confession of Faith. In the Westminster Confession, it is stated that, “the bodies of men, after death, return to dust, and see corruption; but their souls (which neither die nor sleep), having an immortal subsistence, immediately return to God.” Nevertheless, while they are with God, souls wait for “the full redemption of their bodies.” Thus, Presbyterians believe that their body will be reunited with their soul when Jesus returns to Earth during the final judgment. This could, in part, account for the increase in “still works” responses for the bodily processes following the theistic prime in Tanna.

Just as it is challenging to imagine the cessation of thought, it is challenging to imagine disembodiment (Hodge, 2008, 2011). This cognitive challenge is revealed in Christian doctrine and in everyday thinking. The interviews in Vanuatu implied that the body is in some way reconstituted in Heaven and would work in much the same way that it did on Earth. Indeed, the findings in the United States also indicate that a theistic prime increases participants’ willingness to endorse the continuation of biological as well as psychological processes. By implication, to varying degrees, participants in both countries conceive of the afterlife in an embodied fashion.

Taken together, the findings of the current research provide a comprehensive and nuanced picture of what aspects of afterlife beliefs are stable across cultures and what aspects are more likely to vary. Thus, we find evidence of considerable cross-cultural stability in the impact of theistic as compared to non-theistic priming. Similarly, we find evidence for cross-cultural stability in the tendency to mix natural and supernatural explanations when thinking about what happens to both psychological and biological processes after death. The developmental trajectory of afterlife beliefs across cultures also seems to be fairly consistent—once a biological understanding of death has been reached, the possibility of continued functioning of various processes can be entertained. We also find evidence for an overall differentiation between bodily and mental processes. However, previous research emphasizing beliefs about the continuity of mental but not bodily processes in the afterlife has ignored the assumption of embodiment that is found in various Christian doctrines. The idea of an afterlife in which the functions of the body can continue, just like the functions of the mind, is far from “unthinkable.”

Cognitive scientists are increasingly recognizing the necessity of cross-cultural perspectives and the utility of anthropological approaches in examining questions about cognition (Beller & Bender, 2015; Legare & Harris, 2016). Our research provides an example of what can be gained by synthesizing anthropological and psychological methodologies to examine cognitive diversity. Whereas we found evidence of general cross-cultural stability in reasoning about the continuation of function following death, our findings indicate that afterlife concepts vary between populations. This suggests that the interaction of cognition and culture plays a significant part in the formation of concepts. Importantly, these findings cannot be interpreted without knowledge of the specific history and cultural setting of Tanna, Vanuatu. Future research in other cultural contexts will provide additional insight into the diversity of afterlife beliefs, as well as the developmental constraints associated with this universal belief system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chief Peter Marshall, Chief Kaimua, Chief Yappa, George, Jimmy Takaronga, Teana Tufunga, and Jean-Pascal, as well as the Tafea Cultural Center, for assistance conducting the interviews in Tanna. We would also like to thank Irene Jea, Courtney Crosby, Viviana Wan, Riley Little, Sarah Mohkamkar, Emily Shanks, Casey Brown, Alexa Perlick, Annabel Reeves, and Rithika Yogeshwarun for their assistance with data transcription. This research was supported by grants #37624 and #40102 from the John Templeton Foundation to the last author.

References

- Astuti R. (2011). Death, ancestors and the living dead: Learning without teaching in Madagascar. In Talwar V, Harris PL, & Schleifer M. (Eds.), Children’s understanding of death: From biological to religious conceptions (pp. 1–18). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Astuti R, & Harris PL (2008). Understanding mortality and the life of the ancestors in rural Madagascar. Cognitive Science, 32, 713–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beller S, & Bender A. (Eds.). (2015). Exploring cognitive diversity: Anthropological perspectives on cognition. [Special issue]. Topics in Cognitive Science, 7, 548–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bering JM (2002). Intuitive conceptions of dead agents’ minds: The natural foundations of afterlife beliefs as phenomenological boundary. Journal of Culture and Cognition, 2, 263–308. [Google Scholar]

- Bering JM (2006). The folk psychology of souls. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29, 453–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bering JM, & Bjorklund DF (2004). The natural emergence of reasoning about the afterlife as a developmental regularity. Developmental Psychology, 40, 217–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bering JM, Hernandez-Blasi C, & Bjorklund DF (2005). The development of “afterlife” beliefs in religiously and secularly schooled children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 23, 587–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom P. (2004). Descartes’ baby: How the science of child development explains what makes us human. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brent SB, & Speece MW (1993). “Adult” conceptualization of irreversibility: Implications for the development of the concept of death. Death Studies, 17, 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M, Leach M, & Scambary J. (2013). Reconciling, custom, citizenship, and colonial legacies: NiVanuatu tertiary student attitudes to national identity. Nations and Nationalism, 19, 715–738. [Google Scholar]

- Cox M, Alatoa H, Kenni L, Naupa A, Rawlings G, Soni N, Vatu C, Sokomanu G, & Bulekone V. (2007). The unfinished state: Drivers of change in Vanuatu. Canberra: AusAID. [Google Scholar]

- Evans EM., Legare CH., & Rosengren K. (2010). Engaging multiple epistemologies: Implications for science education. In Ferrari M. & Taylor R. (Eds.), Epistemology and science education: Understanding the evolution vs. intelligent design controversy (pp. 111–139). New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory JE, & Gregory RJ (2002). Breaking equilibrium: Three styles of education on Tanna, Vanuatu. Journal of Human Ecology, 13, 351–356. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PL (2011). Death in Spain, Madagascar, and beyond. In Talwar V, Harris PL, & Schleifer M. (Eds.), Children’s understanding of death: From biological to religious conceptions (pp. 19–40). New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PL, & Gimenez M. (2005). Children’s acceptance of conflicting testimony: The case of death. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 5, 143–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge KM (2008). Descartes’ mistake: How afterlife beliefs challenge the assumption that humans are intuitive Cartesian substance dualists. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 8, 387–415. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge KM (2011). On imagining the afterlife. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 11, 367–389. [Google Scholar]

- Keesing R. (1982). Kastom in Melansia: An overview. Mankind, 14, 297–391. [Google Scholar]

- Legare CH, Evans ME, Rosengren KS, & Harris PL (2012). The coexistence of natural and supernatural explanations across cultures and development. Child Development, 83, 779–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legare CH, & Gelman SA (2008). Bewitchment, biology, or both: The co-existence of natural and supernatural explanatory frameworks across development. Cognitive Science: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 32, 607–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legare CH, & Harris PL (2016). The ontogeny of cultural learning. Child Development, 87, 633–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton R. (1993). Culture and identity in the South Pacific: A comparative analysis. Man, 28, 741–759. [Google Scholar]

- Peck JG, & Gregory RJ (2005). A brief overview of the Old New Hebrides. Anthropologist, 7, 269–282. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins J, Schieffelin B, & Vicala A. (2014). Evangelical conversion and the transformation of the self in Amazonia and Melanesia: Christianity and the revival of anthropological comparison. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 56, 559–590. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth SJ, Levin W, Bang M, Washinawatok K, Waxman SR, & Medin DL (2012). Cultural differences in children’s ecological reasoning and psychological closeness to nature: Evidence from Menominee and European American children. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 12, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke C. (2014). I see dead people: Disembodied souls and Aquinas’s “Two-Person” problem. Oxford Studies in Medieval Philosophy, 2, 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Watson-Jones RE, Busch JTA, & Legare CH (2015). Interdisciplinary and cross-cultural perspectives on explanatory coexistence. Topics in Cognitive Science, 7, 611–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White CJ (2016). Cross-cultural similarities in reasoning about personal continuity in reincarnation: Evidence from South India. Religion, Brain and Behavior, 6, 130–153. [Google Scholar]