Abstract

Introduction

Monkeypox (Mpox) is an infectious illness that can spread to humans through infected humans, animals, or contaminated objects. In 2022, the monkeypox virus spread to over 60 countries, raising significant public health concerns. Nurses play a vital role in patient care and have critical responsibilities in managing infected patients and being aware of the potential impact on the general population.

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the knowledge and attitudes (KAs) of Bangladeshi nurses regarding monkeypox infectious disease.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted between October 2022 and March 2023 to evaluate the KA of nurses. Semi-structured and self-administered questionnaires were used, distributed via Google Form, and a convenient sampling technique was implemented. The dataset was analyzed using the Chi-square test, multivariable logistic regression, and Pearson correlation coefficient.

Results

A total of 1047 datasets were included in the final analysis. Overall, 57.97% of the participants demonstrated good knowledge, and 93.12% of the respondents had a positive attitude towards monkeypox disease. Female nurses exhibited better knowledge (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 1.36; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.88–1.98) and a more positive attitude (AOR 1.64; 95% CI 1.12–3.00) than male nurses. Furthermore, a strong correlation was observed between good knowledge of monkeypox disease and a positive attitude (r = 0.76, p < 0.001), while poor knowledge moderately correlated with a negative attitude (r = 0.53, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Given the need for further improvement in KA, we recommend implementing additional training programs to enhance the abilities and motivation of nurses in effectively managing patients affected by monkeypox.

Keywords: knowledge, attitude, monkeypox, infection, nurses

Introduction

Human monkeypox (Mpox) is a rarely fatal and infectious disease caused by the monkeypox virus (Sklenovská & Van Ranst, 2018). Children infected with the monkeypox virus are much more likely to develop complications and, consequently, have a higher mortality rate than adults (Adler et al., 2022). Monkeypox and smallpox viruses belong to the same family called Poxviridae (Xiang & White, 2022). Monkeypox virus infection is unrelated to chickenpox, but symptoms are similar (CDC, 2022a). Symptoms of monkeypox disease include chills, fever, headache, swollen lymph nodes, muscle aches, exhaustion, rashes, etc. (Minhaj et al., 2022; Saputra et al., 2022). The monkeypox virus can spread from an infected animal to a human or from an infected human to another human through direct contact with body fluids, rashes, and scabs (Chowdhury et al., 2022; Hasan et al., 2023). Additionally, the virus can spread through kissing, cuddling, touching contaminated clothes, or linen items, and from a pregnant woman to her fetus through the placenta (CDC, 2022a; Isidro et al., 2022).

Monkeypox virus was first identified in central and western African countries in 1970 (Durski et al., 2018), and it has received growing global attention due to sporadic outbreaks and the potential for international spread (Ahmed et al., 2023; Berdida, 2023). Particularly, the widespread international travels and the movement of people across countries have contributed considerably to the global spread of this virus (Baker et al., 2022). So far, the number of reported monkeypox cases reached at least 85,000 in 2022, spanning over 60 countries (CDC, 2022b). While the virus remains prevalent in Africa, it has also been detected in regions such as the USA and EU/EEA countries (Our World in Data, 2023).

Review of Literature

Several studies have assessed the knowledge and attitudes (KAs) of healthcare workers (HCWs) about human monkeypox virus infection. A study by Das et al. (2023) revealed that HCWs who had studied monkeypox during their professional education had a considerably more favorable attitude towards its control and prevention and a greater desire to learn about new emerging diseases. Another study explored whether demographic variables were significantly associated with HCWs’ good knowledge (Sobaikhi et al., 2023). In addition, a study by Alshahrani et al. (2022) highlighted that many medical professionals knew little about monkeypox, its transmission, or the clinical differences between it and other common diseases.

Nurses, as an integral part of the healthcare workforce, are involved in counseling patients and their attendants to prevent the transmission of infectious diseases. Their knowledge, attitudes, and practices greatly impact patient outcomes and the overall control of infectious disease outbreaks. Nurses at the forefront of direct patient care require accurate and up-to-date knowledge about emerging infectious diseases to provide appropriate care and implement infection control measures (Ibrahim et al., 2022).

Given the highly contagious nature of monkeypox, it is imperative to assess the KAs of nurses on its transmission, symptoms, preventive measures, and appropriate protocols for isolation and treatment. This will ensure the safety of HCWs and enhance the effective management and containment of potential outbreaks, safeguarding both patients and the broader community. Research specifically focused on the KAs of nurses regarding monkeypox disease in endemic areas. In comparison, there is limited evidence on low- and middle-income countries, including Bangladesh. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the KAs of Bangladeshi nurses regarding the monkeypox infectious disease.

Understanding the KAs of nurses about monkeypox is crucial for several reasons. Firstly, it helps identify potential gaps in knowledge, allowing for targeted training and educational interventions to improve their preparedness in managing monkeypox cases (Ahmed et al., 2022). Secondly, assessing attitudes can provide insights into nurses’ perceptions, beliefs, and willingness to adopt preventive measures and implement best practices. This information can guide the development of strategies to enhance infection control measures and promote effective communication with patients and their families. Thirdly, by understanding the factors influencing nurses’ KAs, policymakers and healthcare institutions can design interventions and develop policies to support and empower nurses as frontline responders to infectious diseases.

Methods and Materials

Study Design and Setting

A cross-sectional online survey questionnaire was administered to Bangladeshi nurses between October 2022 and March 2023, to measure their KAs surrounding monkeypox virus disease. All registered nurses licensed by the Bangladesh Nursing Council were considered eligible. It took roughly 25–30 min to complete the survey.

Sample size: The sample size was determined using the following statistical formula:

Here,

n = desired sample size

Z = 1.96 (95% confidence interval)

p = Prevalence estimates 50% = 0.5 (unknown)

q = 1- p

d = proportion of sampling error = (0.05)

By assuming a 10% non-response rate, the sample size is 384 + 10% = 424 respondents were required for the minimum sample size.

Data Collection and Management

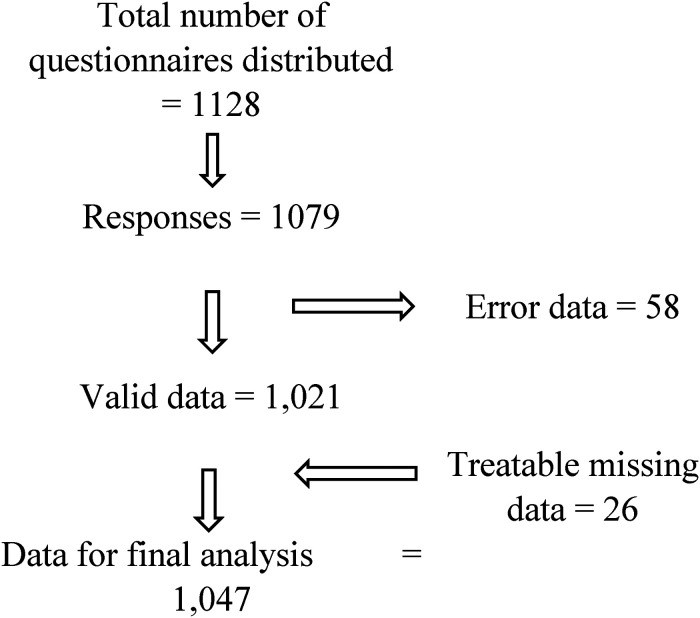

The surveys were kept in English because the nursing curriculum in Bangladesh is taught in English. Using convenient sampling techniques, semi-structured and self-administered questionnaires via Google Forms were used to collect data. Several WhatsApp and Facebook groups for nurses were sent with a link to the questionnaire, which took about 25 to 30 min to complete. In addition, over 976 email addresses were obtained from different healthcare organizations, and they were invited by email to participate. The dataset was exported into Excel to be imported into STATA version 16 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Data cleaning procedure.

Study Variables

Demographic variables include participants’ age, sex, marital status, highest education level, monthly salary, employer type, employer location (urban/rural), working environment (tertiary/general/community clinic/other healthcare settings), working experience, monkeypox virus known or unknown, attendance at national/international conferences, and education about the monkeypox virus.

Knowledge variables: Nurses’ knowledge was assessed using 29 (Yes/No) questions. The questions were adapted from existing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sources (CDC, 2022a). Questionnaires were graded from 0 to 29 points. Each question answered correctly is worth one point; 0 to 11 points indicate poor, 12 to 21 points indicate medium, and 22 to 29 points indicate good knowledge.

Attitude variables: Nine questions were developed to assess the positive or negative attitudes of nurses. The scores for the questions varied from 1 to −1. Agree = 1, Neutral = 0, and disagree = -1. A score of less than five indicates a negative attitude, whereas five or more indicates a positive attitude.

Validity and Reliability

Two nurse practitioners and two senior medical consultants in medicine reviewed the questionnaires. The content validity ratio (CVR) formula, CVR = (Ne-n/2) /(n/2), was used to determine whether the questionnaires were relevant or not or needed revision or elimination (Almanasreh et al., 2019). The CVR scored 0.81 for knowledge and 0.78 for attitude, respectively.

The questionnaires were distributed among 30 nurses for a pilot study to determine the internal consistency of the variables by calculating Cronbach alpha. The values of knowledge were 0.84, and attitudes were 0.79.

Statistical Analysis

The dataset was tabulated and examined for consistency and completeness using STATA 16. Data obtained from the pilot study were excluded from the final analysis. The acquired data were analyzed for descriptive and inferential statistics. Continuous variables were reported as means and standard deviations, while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. The descriptive analysis encompassed all demographic characteristics and responses to questions regarding nurses’ KAs. The inferential analysis included: (a) the chi-square test to compare expected and observed findings, (b) multivariable logistic regression to model the relationship between predictor and outcome variables, and (c) the Pearson correlation coefficient was used to assess the association between continuous variables.

Ethical Approval

The Mahbubur Rahman Memorial Hospital & Nursing Institutional Review Board approved this study (reference number: HRM/MRMH/302/10/04/2022). Prior to participating in the study, online informed consent was obtained from those who completed the online survey, and written informed consent was received from those who completed the hard copy survey. The identities of the participants were kept confidential.

Results

A total of 1047 respondents completed the questionnaire. Participants’ ages ranged from 23 to 47 years: 55.3% of participants age were between 23 to 28 years; 83% of participants were female, and 60.93% of participants were married. The highest percentage (44.22%) of the participants had a diploma in nursing. The highest number of 74.88% of respondents’ salary was less than 35 thousand takas per month. In addition, 58.45% of respondents were employed at private/international organizations. Among the participants, 55.68% were from urban areas. Moreover, 32.09% of the participants were working at tertiary hospitals; 51.77% of the participants had 4 to 7 years of working experience; 87.01% and 92.17% of respondents had not attended any national and international conference regarding monkeypox viral infection, respectively. However, 71.25% of the participants did not receive any information about the monkeypox virus during their nursing education (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants.

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean = 32.59 years; SD = 7.45) | ||

| 23–28 years | 579 | 55.3 |

| 29–34 years | 293 | 27.99 |

| 35–40 years | 96 | 9.17 |

| 41–46 years | 58 | 5.54 |

| ≥ 47 years | 21 | 2 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 178 | 17 |

| Female | 869 | 83 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 638 | 60.93 |

| Unmarried | 376 | 35.91 |

| Divorced/undisclosed | 33 | 3.16 |

| Highest education level | ||

| Diploma | 463 | 44.22 |

| Bachelor degree | 413 | 39.45 |

| Master degree | 164 | 15.66 |

| PhD | 7 | 0.67 |

| Monthly salary | ||

| < 35 thousand takas | 784 | 74.88 |

| 36–45 thousand takas | 178 | 17 |

| > 45 thousand takas | 85 | 8.12 |

| Employer type | ||

| Government | 341 | 32.57 |

| Private/international | 612 | 58.45 |

| Non-government institution | 94 | 8.98 |

| Employer location | ||

| Urban area | 583 | 55.68 |

| Rural area | 464 | 44.32 |

| Working environmental | ||

| Tertiary hospital | 336 | 32.09 |

| General hospital | 289 | 27.6 |

| Community clinic | 257 | 24.55 |

| Other healthcare settings | 165 | 15.76 |

| Working experience | ||

| Less than 3 years | 411 | 39.26 |

| 4 to 7 years | 542 | 51.77 |

| More than 7 years | 94 | 8.97 |

| Did you hear about the monkeypox virus? | ||

| Yes | 873 | 83.38 |

| Never | 174 | 16.62 |

| When did you first hear information about monkeypox? | ||

| Several weeks ago | 642 | 61.32 |

| 2 months ago | 137 | 13.08 |

| Within 1 year | 94 | 8.98 |

| Not applicable | 174 | 16.62 |

| Did you attend any national conferences regarding monkeypox viral infection? | ||

| Yes | 136 | 12.99 |

| No | 911 | 87.01 |

| Did you attend any international conferences regarding monkeypox viral infection? | ||

| Yes | 82 | 7.83 |

| No | 965 | 92.17 |

| Did you receive any information about the monkeypox virus during your nursing education? | ||

| Yes | 301 | 28.75 |

| No | 746 | 71.25 |

SD=standard deviation.

Knowledge

Out of the total participants (n = 607), 57.97% demonstrated good knowledge, while 15.57% showed medium knowledge, and 26.46% had poor knowledge about the monkeypox virus. Among the participants with good knowledge, a significant portion (66.89%) fell within the age range of 23 to 28 years. Most participants were female, accounting for 79.57%, and 59.97% were married. When considering the participants’ educational background, it was found that 49.26% of nurses holding a bachelor's degree exhibited good knowledge of the monkeypox virus. Additionally, the highest percentage of nurses with good knowledge (61.45%) were those working in private/international organizations. Furthermore, the study analyzed the knowledge of nurses based on their work settings. It was observed that 67.87% of nurses working in urban areas displayed good knowledge, while 42.34% of nurses in tertiary hospitals also demonstrated good knowledge (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of Knowledge and Attitude Regarding Human Monkeypox Viral Infection among Nurses.

| Question | Correct answer | No. (%) | Mean score (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 25.39 (1.95) | ||

| 1. Monkeypox is prevalent in Southeast Asian countries | Yes | 523 (49.95) | |

| 2. Monkeypox is prevalent in Central and West Africa. | Yes | 831 (79.37) | |

| 3. Are there any human monkeypox cases in your country? | No | 798 (76.22) | |

| 4. Are there any human monkeypox cases in USA/Canada/UK/Europe? | Yes | 845 (80.7) | |

| 5. Recently, monkeypox cases have spread in more than 21 countries? | Yes | 692 (66.09) | |

| 6. Monkeypox is a viral disease infection | Yes | 730 (69.72) | |

| 7. Monkeypox is a bacterial disease infection | No | 348 (33.24) | |

| 8. Monkeypox is easily transmitted from human to human. | Yes | 576 (55.01) | |

| 9. Monkeypox can be transmitted through the bite of an infected monkey. | Yes | 649 (61.99) | |

| 10. Monkeypox and smallpox have similar signs and symptoms. | Yes | 733 (70) | |

| 11. Monkeypox and smallpox have the same signs and symptoms. | No | 460 (44.13) | |

| 12. The incubation period (time from infection to symptoms) for monkeypox is usually 7–14 days but can range from 5 to 21 days. | Yes | 580 (55.4) | |

| 13. Monkeypox illness typically lasts for 2–4 weeks. | Yes | 537 (51.29) | |

| 14. Monkeypox virus can spread when a person comes into contact with the virus from an infected animal. | Yes | 782 (74.89) | |

| 15. Monkeypox virus can be spread when a person comes into contact with the virus from an infected person. | Yes | 819 (78.22) | |

| 16. Monkeypox virus can spread through materials contaminated with the virus. | Yes | 965 (92.17) | |

| 17. Monkeypox virus can cross the placenta from the mother to her fetus. | Yes | 643 (61.41) | |

| 18. Monkeypox virus may also be spread through direct contact with body fluids or sores on an infected person or with materials that have touched body fluids or sores, such as clothing or linens. | Yes | 827 (78.99) | |

| 19. Monkeypox can spread during intimate contact between people, including during sex and activities like kissing, cuddling, or touching parts of the body with monkeypox sores. | Yes | 863 (82.43) | |

| 20. A flu-like syndrome is one of the human monkeypox's early signs or symptoms. | Yes | 693 (66.19) | |

| 21. Rashes (an area of irritated or swollen skin) on the skin are one of the signs or symptoms of human monkeypox. | Yes | 837 (79.94) | |

| 22. Papules (which look like tiny, raised bumps on the skin) on the skin are one of the signs or symptoms of human monkeypox. | Yes | 753 (71.92) | |

| 23. Vesicles (a thin-walled sac filled with a fluid, usually clear and small) on the skin are one of the signs or symptoms of human monkeypox. | Yes | 887 (84.72) | |

| 24. Pustules (a bulging patch of skin full of a yellowish fluid called pus) on the skin are one of the signs or symptoms of human monkeypox. | Yes | 791 (75.55) | |

| 25. Lymphadenopathy (enlargement of one or more lymph nodes) is one clinical sign or symptom that could be used to differentiate between monkeypox and smallpox cases. | Yes | 529 (50.53) | |

| 26. One management option for symptomatic monkeypox patients is to use paracetamol. | Yes | 736 (70.30) | |

| 27. Antivirals are required in the management of human monkeypox patients. | Yes | 845 (80.71) | |

| 28. Antibiotics are required in the management of human monkeypox patients. | No | 861 (82.23) | |

| 29. Diarrhea is one of the signs or symptoms of human monkeypox. | Yes | 525 (50.14) |

SD=standard deviation.

Attitude

Among the total respondents (n = 975), an overwhelming majority (93.12%) demonstrated a positive attitude towards preventing monkeypox diseases. Within the group of respondents with a positive attitude, the age range of 23 to 28 constituted the largest percentage (56.92%). Furthermore, a significant proportion of female respondents (86.97%) displayed a positive attitude towards preventing monkeypox diseases. Regarding marital status, it was found that 61.33% of respondents with a positive attitude were married. Concerning educational background, respondents with nursing diplomas accounted for 45.03% of those who held a positive attitude towards monkeypox diseases. Additionally, a substantial percentage (57.85%) of respondents working in private/international organizations exhibited a positive attitude. Moreover, the study analyzed the attitudes of participants based on their geographical locations. It was observed that 58.77% of respondents from urban areas displayed a positive attitude towards preventing monkeypox infection (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of Good Knowledge, and Positive Attitude Based on the Demographics and Characteristics of the Nurses.

| Variables (n = 1047) | Good knowledge (n = 607) | Positive attitude (n = 975) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | p * | N (%) | p * | |

| Age | ||||

| 23–28 years | 406 (66.89) | <0.001 | 555 (56.92) | <0.001 |

| 29–34 years | 128 (21.09) | 0.761 | 274 (28.10) | 0.637 |

| 35–40 years | 41 (6.75) | 0.562 | 83 (8.51) | 1.63 |

| 41–46 years | 23 (3.79) | 0.453 | 45 (4.62) | 0.432 |

| ≥ 47 years | 9 (1.48) | 0.243 | 18 (1.85) | 0.098 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 124 (20.43) | <0.372 | 127 (13.03) | <0.183 |

| Female | 483 (79.57) | 0.087 | 848 (86.97) | 0.425 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 364 (59.97) | 0.571 | 598 (61.33) | 0.762 |

| Unmarried | 227 (37.40) | 0.424 | 357 (36.62) | 0.983 |

| Divorced/undisclosed | 14 (2.63) | 1.83 | 20 (2.05) | 0.132 |

| Highest education level | ||||

| Diploma | 172 (28.34) | 0.614 | 439 (45.03) | <0.263 |

| Bachelor degree | 299 (49.26) | 1.72 | 389 (39.90) | 0.564 |

| Master degree | 132 (21.75) | 0.763 | 144 (14.75) | 0.163 |

| PhD | 3 (0.49) | 0.674 | 3 (0.32) | 0.472 |

| Monthly salary | ||||

| < 35 thousand takas | 437 (71.99) | 0.093 | 731 (74.97) | <0.464 |

| 36–45 thousand takas | 117 (19.28) | 0.204 | 168 (17.23) | 0.654 |

| > 45 thousand takas | 53 (8.73) | 0.087 | 76 (7.79) | 0.678 |

| Employer type | ||||

| Government | 195 (32.13) | 0.213 | 328 (33.23) | 0.591 |

| Private/international | 373 (61.45) | 0.374 | 564 (57.85) | 0.901 |

| Non-government institution | 39 (6.43) | 0.674 | 83 (8.51) | 0.536 |

| Employer location | ||||

| Urban area | 412 (67.87) | <0.001 | 573 (58.77) | <0.001 |

| Rural area | 195 (32.13) | 0.463 | 402 (41.23) | 1.65 |

| Working environmental | ||||

| Tertiary hospital | 257 (42.34) | <0.001 | 321 (32.92) | <0.001 |

| General hospital | 110 (18.12) | 0.243 | 266 (27.28) | 0.435 |

| Community clinic | 124 (20.43) | 0.654 | 249 (25.53) | 0.183 |

| Other healthcare settings | 116 (19.11) | 0.837 | 139 (14.26) | 0.753 |

| Working experience | ||||

| Less than 3 years | 297 (48.93) | <0.001 | 382 (39.18) | <0.001 |

| 4 to 7 years | 264 (43.49) | 0.847 | 512 (52.51) | 3.84 |

| More than 7 years | 46 (7.58) | 0.637 | 81 (8.31) | 0.284 |

Values in bold represent significant results.

p-values were from Chi-square test.

KA Based on the Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

This study found that nurses with less experience (less than 3 years) (p-value <0.001), aged between 23 and 28 years (p-value <0.001), exhibited good knowledge and a positive attitude toward monkeypox disease compared to more experienced and older nurses. Additionally, urban area nurses demonstrated good knowledge (p-value <0.001) and a positive attitude (p-value <0.001) compared to nurses in rural areas. Furthermore, nurses in tertiary hospitals displayed good knowledge (p-value <0.001) and a positive attitude (p-value <0.001) compared to nurses in general hospitals, community clinics, and other healthcare settings (Table 3).

After adjusting for the interrelated effect of all variables on knowledge and attitude (KAP), the multivariable logistic regression revealed that female nurses had better knowledge (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 1.36; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.88–1.98) and a positive attitude (AOR 1.64; 95% CI 1.12–3.00) compared to male nurses. Unmarried nurses exhibited better knowledge (AOR 0.48; 95% CI 0.22–0.82) and attitudes compared to married or nurses with undisclosed marital status. Nurses with the highest level of education (Ph.D. holders) significantly demonstrated better knowledge (AOR 5.21; 95% CI 2.20–9.37) and a positive attitude (AOR 4.47; 95% CI 2.58–8.80) compared to those with a bachelor's or diploma degree. Bachelor's degree holders also exhibited better knowledge (AOR 0.73; 95% CI 0.17–1.68) and a more positive attitude (AOR 0.32; 95% CI 0.08–0.88) compared to diploma degree holders.

Likewise, nurses with higher salaries (> 45 thousand takas) displayed good knowledge (AOR 3.61; 95% CI 1.78–6.46) and a more positive attitude (AOR 2.21; 95% CI 1.63–4.37) compared to other income categories. Private/international healthcare nurses (good knowledge: AOR 0.82, 95% CI 0.44–1.56; positive attitude: AOR 0.66, 95% CI 0.23–1.39) and non-government healthcare nurses (good knowledge: AOR 1.38, 95% CI 0.66–2.94; positive attitude: AOR 1.75, 95% CI 0.98–3.20) exhibited considerable good knowledge and a more positive attitude compared to government-employed nurses. Participants who attended national and international monkeypox conferences demonstrated significantly better knowledge and a more positive attitude than those who did not participate in such conferences. Moreover, respondents who received information about the Monkeypox virus during their nursing education exhibited better knowledge (AOR 4.73; 95% CI 2.41–10.87) and a positive attitude (AOR 2.62; 95% CI 1.51–6.38) compared to those who did not (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariable Logistic Regression for the Good Knowledge, and Positive Attitude Based on the Demographics and Characteristics of the Nurses.

| Variables | Good knowledge | Positive attitude |

|---|---|---|

| AOR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | |

| Age | ||

| 23–28 years | Reference | Reference |

| 29–34 years | 0.96 (0.48–2.36) | 1.23 (0.62–2.97) |

| 35–40 years | 0.64 (0.38–1.12) | 0.54 (0.22–0.78) |

| 41–46 years | 0.80 (0.48–1.54) | 0.75 (0.49–1.32) |

| ≥ 47 years | 0.56 (0.28–0.89) | 0.82 (0.52–1.81) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 1.36 (0.88–1.98) | 1.64 (1.12–3.00) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | Reference | Reference |

| Unmarried | 0.48 (0.22–0.82) | 0.63 (0.35–1.27) |

| Divorced/undisclosed | 0.52 (0.30–0.98) | 0.65 (0.35–1.02) |

| Highest education level | ||

| Diploma | Reference | Reference |

| Bachelor degree | 0.73 (0.17–1.68) | 0.32 (0.08–0.88) |

| Master degree | 0.90 (0.12–1.83) | 0.42 (0.11–0.87) |

| PhD | 5.21 (2.20–9.37) | 4.47 (2.58–8.80) |

| Monthly salary | ||

| < 35 thousand takas | Reference | Reference |

| 36–45 thousand takas | 2.10 (1.30–4.23) | 1.78 (1.13–3.45) |

| > 45 thousand takas | 3.61 (1.78–6.46) | 2.21 (1.63- 4.37) |

| Employer type | ||

| Government | Reference | Reference |

| Private/international | 0.82 (0.44–1.56) | 0.66 (0.23–1.39) |

| Non-government institution | 1.38 (0.66–2.94) | 1.75 (0.98–3.20) |

| Employer location | ||

| Urban area | Reference | Reference |

| Rural area | 2.57 (1.42–5.18) | 1.76 (1.10–2.63) |

| Working environmental | ||

| Tertiary hospital | Reference | Reference |

| General hospital | 0.48 (0.28–0.84) | 0.78 (0.42–1.44) |

| Community clinic | 0.63 (0.26–1.49) | 0.33 (0.09–1.20) |

| Other healthcare settings | 0.83 (0.33–2.04) | 0.81 (0.43–1.51) |

| Working experience | ||

| Less than 3 years | Reference | Reference |

| 4 to 7 years | 1.32 (0.37–4.88) | 1.48 (0.09–3.51) |

| More than 7 years | 0.94 (0.18–4.94) | 0.76 (0.16–4.83 |

| Did you hear about the monkeypox virus? | ||

| Yes | Reference | Reference |

| Never | 0.61 (0.12–4.06) | 0.52 (0.10–2.07) |

| When did you first hear information about monkeypox? | ||

| Several weeks ago | Reference | Reference |

| 2 months ago | 1.34 (0.54–2.50) | 0.71 (0.45–1.55) |

| Within 1 year | 0.66 (0.32–1.52) | 0.87 (0.51–1.85) |

| Not applicable | 0.43 (0.14–1.48) | 0.63 (0.32–1.99) |

| Did you attend any national conferences regarding monkeypox viral infection? | ||

| No | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 3.14 (1.83–7.86) | 2.61 (1.17–6.59) |

| Did you attend any international conferences regarding monkeypox viral infection? | ||

| No | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 0.94 (0.18–2.76) | 0.60 (0.08–1.58) |

| Did you receive any information about the monkeypox virus during your nursing education? | ||

| No | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 4.73 (2.41–10.87) | 2.62 (1.51–6.38) |

AOR (Adjusted odds ratio), 95% CI, 95% confidence interval. Values in bold represent significant results.

Association and Correlation of KA on Monkeypox Disease

The findings of the correlation analysis show that good knowledge regarding monkeypox disease is highly correlated with a positive attitude (r = 0.76, p < 0.001), and poor knowledge is moderately correlated with a negative attitude (r = 0.53, p < 0.001). The results of the correlation are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Correlation Between Knowledge, and Attitude (Good Knowledge vs Positive Attitude, and Poor Knowledge vs Negative Attitude).

| Scales | Good knowledge | Poor knowledge | Positive attitude | Negative attitude | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good knowledge | r = 0.76, p < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Poor knowledge | r = 0.53, p < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Positive attitude | ||||||||||

| Negative attitude | ||||||||||

Discussion

To the author's knowledge, this study is the first in Bangladesh to report on the KAs of nurses regarding human monkeypox virus infection. This study found that only 57.97% of nurses who are young age (23 to 28 years), female, unmarried, receiving a higher salary (>45 thousand takas), have a higher degree (master's, Ph.D.), working in a private/international organization, or a tertiary hospital had a higher level of knowledge. These findings align with previous studies conducted in other countries. For example, the study by Miraglia Del Giudice et al. (2023) in Italy reported similar knowledge gaps among HCWs, emphasizing the need for targeted educational interventions. On the other hand, studies conducted in different geographical regions, such as Lebanon (Malaeb et al., 2023) and Indonesia (Harapan et al., 2020), also highlighted limited knowledge among medical professionals regarding monkeypox. Therefore, the current study's findings support that there is a global need for improved knowledge among nurses regarding monkeypox.

Regarding attitudes, most respondents (93.12%) displayed a positive attitude towards monkeypox diseases. This positive attitude was also higher among younger nurses, females, married women, and those working in private/international organizations. The high percentage of participants with a positive attitude is encouraging, as positive attitudes are essential for effective disease control and prevention measures. When examining the association between KA, this study found a strong positive correlation between good knowledge and a positive attitude toward monkeypox. Comparable findings were observed in another study conducted in China. For example, Peng et al. (2023) found that HCWs’ exemplary level of knowledge significantly influences a generally positive attitude toward diseases. In addition, Hasan et al. (2023) revealed that HCWs with better knowledge of monkeypox are more likely to adopt positive attitudes, which can contribute to improved disease prevention and control efforts. This emphasizes enhancing nurses’ knowledge through targeted educational programs and interventions to promote positive attitudes and improve overall preparedness.

While a high percentage of respondents had heard about the monkeypox virus before the study, many had not received information about it during their nursing education. However, understanding the clinical manifestations, transmission mechanisms, incubation period, treatment procedures, and effective preventive measures is crucial when dealing with viral diseases (Berdida, 2023; Wang et al., 2023). Although there have been no reported cases of monkeypox illness in Bangladesh, 23.78% of the respondents stated that monkeypox is prevalent in the country. In addition, 11.16% of the nurses gave an inaccurate answer, considering monkeypox a bacterial and viral disease. Besides, 13.20% of the participants incorrectly stated that treating monkeypox disease requires both antivirals and antibiotics. These responses indicate that many nurses have knowledge gaps in managing patients affected by bacterial and viral diseases. Regarding this, Qureshi et al. (2022) mentioned that continuous training on emerging and non-emerging diseases gives nurses the confidence to deal with new illnesses competently. However, the findings of this survey determined a close correlation between KA. These findings suggest that gender, marital status, educational attainment, income level, and participation in educational conferences shape nurses’ KAs toward monkeypox.

Implications of This Study

This study emphasized the importance of educational campaigns and regular updates on emerging infectious diseases to improve nurses’ preparedness and response capabilities. It adds to the growing literature on infectious disease management and highlights the importance of healthcare professionals’ role in disease prevention and control. However, from a practical standpoint, the study's results would help guide the development of targeted training programs and educational interventions to address the identified knowledge gaps among nurses. It can inform the design of educational materials and resources specific to monkeypox, enabling nurses to provide accurate information, implement appropriate preventive measures, and deliver quality care to affected patients.

In terms of policy implications, the study underscores the need for healthcare institutions and policymakers to prioritize infectious disease preparedness and response. This study emphasizes the importance of investing in the training and continuous professional development of nurses to enhance their knowledge and skills in managing infectious diseases like monkeypox. The findings can inform policy decisions related to workforce planning, resource allocation, and the implementation of standardized protocols and guidelines for disease control and prevention.

Study Limitations

Studying possesses several limitations. Firstly, convenient sampling may have introduced selection bias, as the respondents may not fully represent all Bangladeshi nurses. Consequently, the generalizability of the findings could be limited. Secondly, relying on self-reported data in online surveys might have introduced recall and social desirability biases, potentially affecting the accuracy of the participants’ reported KAs. Additionally, the study's cross-sectional design only provides a snapshot of the participant's KAs at a specific time. Moreover, the survey being conducted in English could have posed a language barrier for some participants, impacting their comprehension, and potentially influencing their responses.

Recommendations

Several recommendations can be proposed to address the limitations mentioned and guide future research. Firstly, future studies should adopt a more rigorous sampling strategy, such as random sampling, to ensure the selection of a representative sample of Bangladeshi nurses. This would bolster the external validity of the findings. Additionally, employing a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative surveys with qualitative interviews, would provide a more comprehensive understanding of nurses’ perceptions and experiences regarding monkeypox. This approach would shed light on the context and underlying reasons behind their KAs, enhancing the study's depth and richness of data. Finally, it is strongly recommended to strengthen the healthcare system and prevent the emergence of new epidemics by developing a skilled and competent health workforce through adequate planning and intervention.

Conclusion

The study shed light on the current level of KAs of nurses towards monkeypox disease, emphasizing the need for further research and training to bridge the knowledge gaps identified among healthcare professionals. It was observed that factors such as age, gender, education, marital status, salary, and workplace influenced nurses’ KAs. Therefore, continuous education and training programs are essential to keeping healthcare professionals updated on emerging infectious diseases and their management. Finally, by addressing the identified knowledge gaps and promoting a positive attitude towards disease prevention and control, healthcare systems might improve their preparedness and response to outbreaks, ultimately safeguarding public health.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all the participants of the study who patiently answered all the questions and shared their valuable responses.

Author's Note: Moustaq Karim Khan Rony is also affiliated with Institute of Social Welfare and Research, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh; Dilruba Akter is also also affiliated with Bachelor of Science in Nursing at Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, Bangladesh and Hasnat M. Alamgir is also affiliated with Professor of Pharmacy, Southeast University, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ Contribution: Conceptualization: Moustaq Karim Khan Rony, Mst. Rina Parvin

Data curation: Moustaq Karim Khan Rony, Dilruba Akter

Formal analysis: Moustaq Karim Khan Rony, Mst. Rina Parvin, Hasnat M. Alamgir

Investigation: Moustaq Karim Khan Rony, Priyanka Das Sharmi

Methodology: Moustaq Karim Khan Rony, Dilruba Akter

Project administration: Moustaq Karim Khan Rony, Mst. Rina Parvin

Resources: Moustaq Karim Khan Rony, Priyanka Das Sharmi

Software: Moustaq Karim Khan Rony, Mst. Rina Parvin

Supervision: Moustaq Karim Khan Rony, Hasnat M. Alamgir

Validation: Moustaq Karim Khan Rony, Priyanka Das Sharmi, Hasnat M. Alamgir

Visualization: Moustaq Karim Khan Rony, Dilruba Akter

Writing—original draft: Moustaq Karim Khan Rony, Priyanka Das Sharmi, Dilruba Akter

Writing—review & editing: Moustaq Karim Khan Rony, Mst. Rina Parvin, Hasnat M. Alamgir

ORCID iD: Moustaq Karim Khan Rony https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6905-0554

References

- Adler H., Gould S., Hine P., Snell L. B., Wong W., Houlihan C. F., Osborne J. C., Rampling T., Beadsworth M. B., Duncan C. J., Dunning J., Fletcher T. E., Hunter E. R., Jacobs M., Khoo S. H., Newsholme W., Porter D., Porter R. J., Ratcliffe L., … Hruby D. E. (2022). Clinical features and management of human monkeypox: A retrospective observational study in the UK. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 22(8), 1153–1162. 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00228-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S. K., Abdulqadir S. O., Omar R. M., Abdullah A. J., Rahman H. A., Hussein S. H., Mohammed Amin H. I., Chandran D., Sharma A. K., Dhama K., Sallam M., Harapan H., Salari N., Chakraborty C., Abdulla A. Q. (2023). Knowledge, attitude and worry in the kurdistan region of Iraq during the Mpox (monkeypox) outbreak in 2022: An online cross-sectional study. Vaccines, 11(3), 610. 10.3390/vaccines11030610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S. K., Ahmed Rashad E. A., Mohamed M. G., Ravi R. K., Essa R. A., Abdulqadir S. O., Khdir A. A. (2022). The global human monkeypox outbreak in 2022: An overview. International Journal of Surgery, 104, 106794. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2022.106794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almanasreh E., Moles R., Chen T. F. (2019). Evaluation of methods used for estimating content validity. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 15(2), 214–221. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.03.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshahrani N. Z., Algethami M. R., Alarifi A. M., Alzahrani F., Alshehri E. A., Alshehri A. M., Sheerah H. A., Abdelaal A., Sah R., Rodriguez-Morales A. J. (2022). Knowledge and attitude regarding monkeypox virus among physicians in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Vaccines, 10(12), 2099. 10.3390/vaccines10122099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker R. E., Mahmud A. S., Miller I. F., Rajeev M., Rasambainarivo F., Rice B. L., Takahashi S., Tatem A. J., Wagner C. E., Wang L.F., Wesolowski A., Metcalf C. J. E. (2022). Infectious disease in an era of global change. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 20(4), 193–205. 10.1038/s41579-021-00639-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdida D. J. E. (2023). Population-based survey of human monkeypox disease knowledge in the Philippines: An online cross-sectional study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 79(7), 2684–2694. 10.1111/jan.15635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2022a). About monkeypox. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/about.html

- CDC. (2022b). 2022 Mpox Outbreak Global Map. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/response/2022/world-map.html

- Chowdhury S. R., Datta P. K., Maitra S. (2022). Monkeypox and its pandemic potential: What the anaesthetist should know. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 129(3), e49–e52. 10.1016/j.bja.2022.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S. K., Bhattarai A., Kc S., Shah S., Paudel K., Timsina S., Tharu S., Rawal L., Leon-Figueroa D. A., Rodriguez-Morales A. J., Barboza J. J., Sah R. (2023). Socio-demographic determinants of the knowledge and attitude of Nepalese healthcare workers toward human monkeypox: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1161234. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1161234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durski K. N., McCollum A. M., Nakazawa Y., Petersen B. W., Reynolds M. G., Briand S., Djingarey M. H., Olson V., Damon I. K., Khalakdina A. (2018). Emergence of monkeypox—West and Central Africa, 1970–2017. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(10), 306–310. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6710a5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harapan H., Setiawan A. M., Yufika A., Anwar S., Wahyuni S., Asrizal F. W., Sufri M. R., Putra R. P., Wijayanti N. P., Salwiyadi S., Maulana R., Khusna A., Nusrina I., Shidiq M., Fitriani D., Muharrir M., Husna C. A., Yusri F., Maulana R., … Mudatsir M. (2020). Knowledge of human monkeypox viral infection among general practitioners: A cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Pathogens and Global Health, 114(2), 68–75. 10.1080/20477724.2020.1743037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan M., Hossain M. A., Chowdhury S., Das P., Jahan I., Rahman M. F., Haque M. M. A., Rashid M. U., Khan M. A. S., Hossian M., Nabi M. H., Hawlader M. D. H. (2023). Human monkeypox and preparedness of Bangladesh: A knowledge and attitude assessment study among medical doctors. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 16(1), 90–95. 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.11.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim P. K., Abdulrahman D. S., Ali H. M., Haji R. M., Ahmed S. K., Ahmed N. A., Abdulqadir S. O., Karim S. A., Mohammed Amin Kamali A. S. (2022). The 2022 monkeypox outbreak—Special attention to nurses’ protection should be a top priority. Annals of Medicine & Surgery, 82. 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.104615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isidro J., Borges V., Pinto M., Sobral D., Santos J. D., Nunes A., Mixão V., Ferreira R., Santos D., Duarte S., Vieira L., Borrego M. J., Núncio S., de Carvalho I. L., Pelerito A., Cordeiro R., Gomes J. P. (2022). Phylogenomic characterization and signs of microevolution in the 2022 multi-country outbreak of monkeypox virus. Nature Medicine, 28(8), 1569–1572. 10.1038/s41591-022-01907-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaeb D., Sallam M., Salim N. A., Dabbous M., Younes S., Nasrallah Y., Iskandar K., Matta M., Obeid S., Hallit S., Hallit R. (2023). Knowledge, attitude and conspiracy beliefs of healthcare workers in Lebanon towards monkeypox. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 8(2), 81. 10.3390/tropicalmed8020081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minhaj F. S., Ogale Y. P., Whitehill F., Schultz J., Foote M., Davidson W., Hughes C. M., Wilkins K., Bachmann L., Chatelain R., Donnelly M. A. P., Mendoza R., Downes B. L., Roskosky M., Barnes M., Gallagher G. R., Basgoz N., Ruiz V., Kyaw N. T. T., … Wong M. (2022). Monkeypox outbreak—nine states, May 2022. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(23), 764–769. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7123e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miraglia Del Giudice G., Della Polla G., Folcarelli L., Napoli A., Angelillo I. F., & The Collaborative Working Group. (2023). Knowledge and attitudes of health care workers about monkeypox virus infection in Southern Italy. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1091267. 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1091267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Our world in data. (2023). Mpox (monkeypox). Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/monkeypox

- Peng X., Wang B., Li Y., Chen Y., Wu X., Fu L., Sun Y., Liu Q., Lin Y.F., Liang B., Fan Y., Zou H. (2023). Perceptions and worries about monkeypox, and attitudes towards monkeypox vaccination among medical workers in China: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 16(3), 346–353. 10.1016/j.jiph.2023.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi M. O., Chughtai A. A., Seale H. (2022). Recommendations related to occupational infection prevention and control training to protect healthcare workers from infectious diseases: A scoping review of infection prevention and control guidelines. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 272. 10.1186/s12913-022-07673-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saputra H., Salma N., Anjari S. R. (2022). Monkeypox transmission risks in Indonesia. Public Health of Indonesia, 8(3), 68–74. 10.36685/phi.v8i3.634 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sklenovská N., Van Ranst M. (2018). Emergence of monkeypox as the most important orthopoxvirus infection in humans. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 241. 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobaikhi N. H., Alshahrani N. Z., Hazazi R. S., Al-Musawa H. I., Jarram R. E., Alabah A. E., Haqawi N. F., Munhish F. A., Shajeri M. A., Matari M. H., Salami R. M., Hobani A. H., Yahya N. A., Alhazmi A. H. (2023). Health workers’ knowledge and attitude towards monkeypox in southwestern Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Diseases (Basel, Switzerland), 11(2), 81. 10.3390/diseases11020081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Peng X., Li Y., Fu L., Tian T., Liang B., Sun Y., Chen Y., Wu X., Liu Q., Lin Y.F., Meng X., Zou H. (2023). Perceptions, precautions, and vaccine acceptance related to monkeypox in the public in China: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 16(2), 163–170. 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y., White A. (2022). Monkeypox virus emerges from the shadow of its more infamous cousin: Family biology matters. Emerging Microbes & Infections, 11(1), 1768–1777. 10.1080/22221751.2022.2095309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]