Abstract

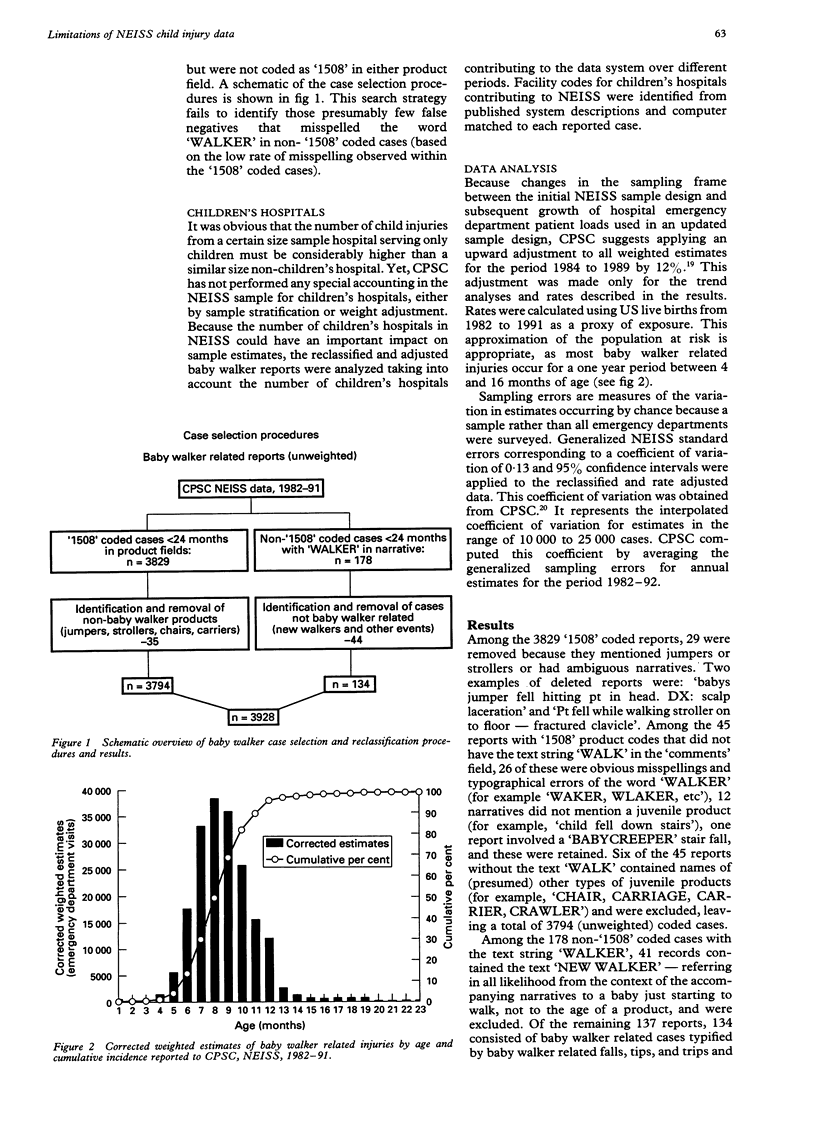

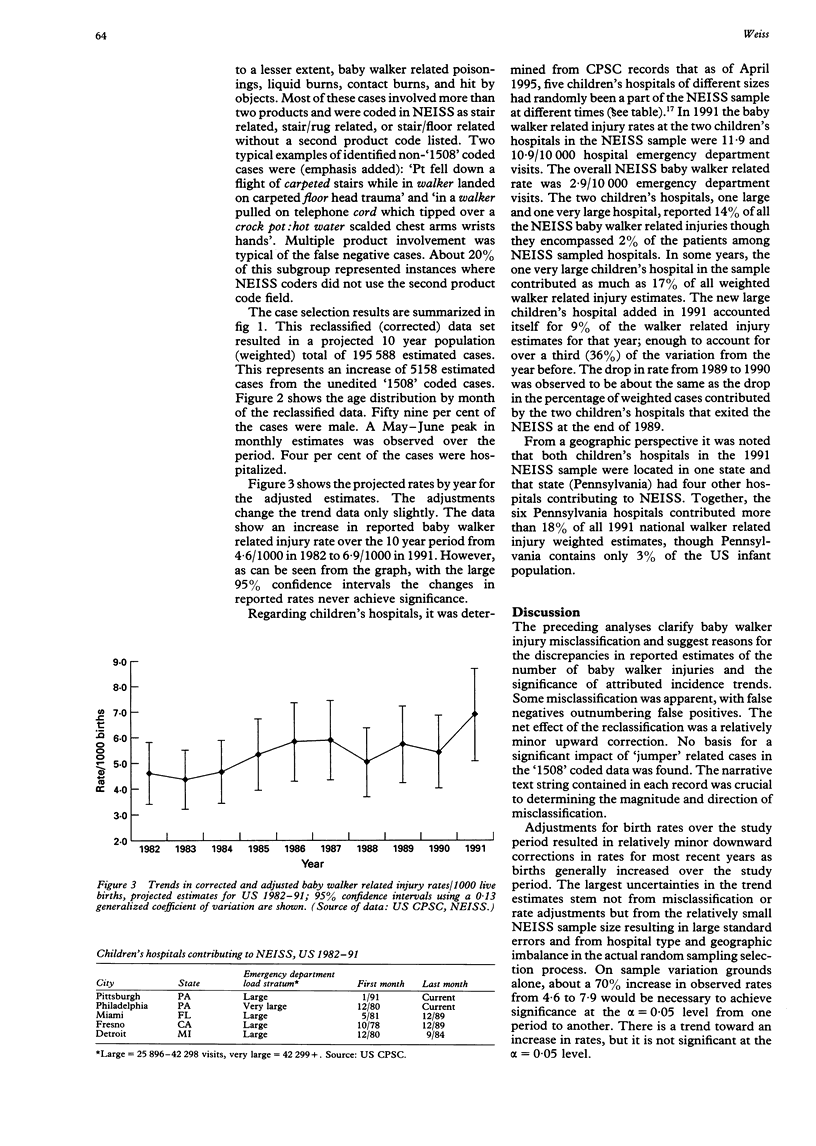

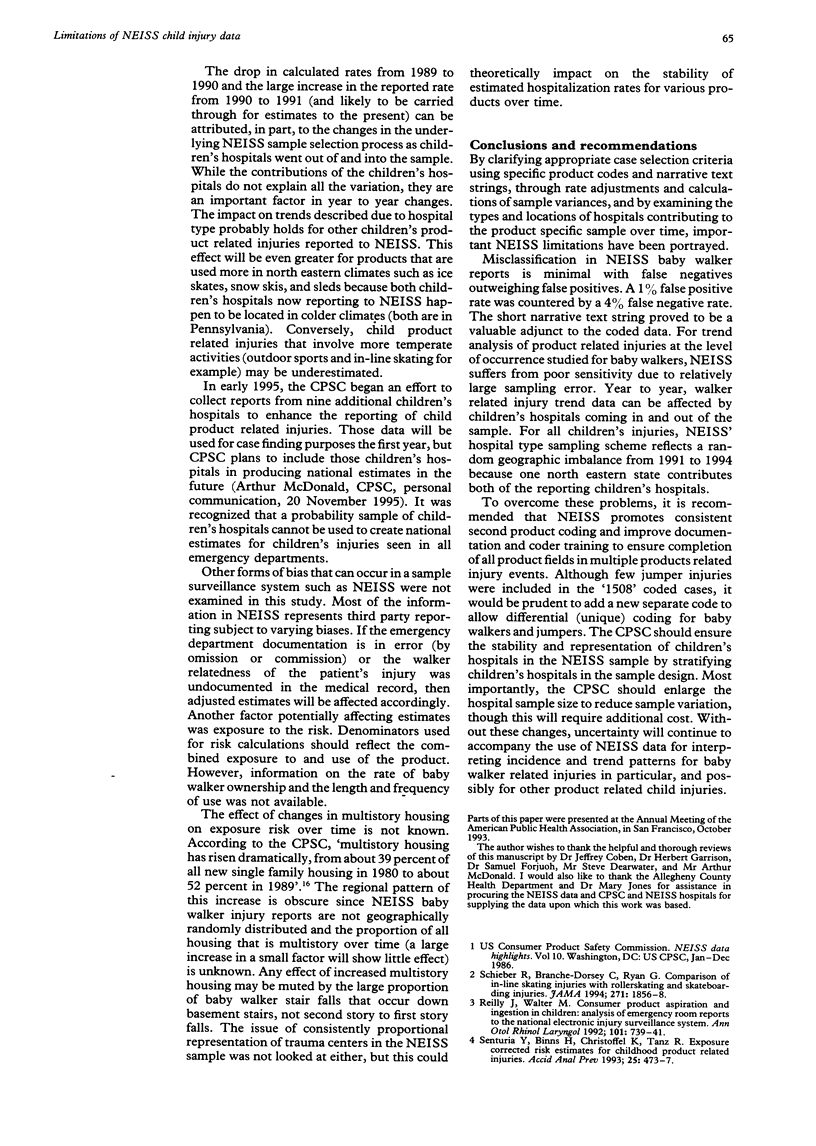

OBJECTIVES: The US Consumer Product Safety Commission's National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) is a primary source for children's consumer product injury surveillance data in the US. Differing interpretations of the emergency department based NEISS baby walker data by various parties prompted this detailed examination, reclassification, and analysis of the NEISS data to explain these discrepancies. METHODS: Case selection was performed by searching the NEISS 1982-91 database for the baby walker product code and various text strings for children less than 24 months old. False negative and false positive cases were identified and reclassified. Adjusted population rates were computed and the types and locations of hospitals contributing to the sample were examined. RESULTS: One per cent false positive and 4% false negative misclassification rates were observed. In 1991, two children's hospitals reported 14% of the baby walker related injuries, though these hospitals made up just 2% of the sample frame. Through random allocation, one state currently contains four acute care hospitals and the only two children's hospitals reporting to the NEISS system. These six hospitals contributed 18% of the walker cases whereas the state represents only 3% of the US infant population. CONCLUSIONS: Misclassification in NEISS baby walker reports is minimal, with false negatives outweighing false positives. For trend analysis of product related injuries at the frequency of occurrence observed for baby walkers, NEISS suffers from low sensitivity due to sampling error. For children's injuries, NEISS' estimates have been affected by children's hospitals coming in and out of the sample and currently reflects a random geographic imbalance because one state contributes both of the reporting children's hospitals. To overcome these problems improved multiple product coding, a unique baby walker code, and stratification of children's hospitals in an enlarged NEISS sample is recommended.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Gaudreault P., McCormick M. A., Lacouture P. G., Lovejoy F. H., Jr Poison exposures and use of ipecac in children less than 1 year old. Ann Emerg Med. 1986 Jul;15(7):808–810. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(86)80378-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcella S., McDonald B. The infant walker: an unappreciated household hazard. Conn Med. 1990 Mar;54(3):127–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly J. S., Walter M. A. Consumer product aspiration and ingestion in children: analysis of emergency room reports to the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1992 Sep;101(9):739–741. doi: 10.1177/000348949210100904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder M. J., Schwartz C., Newman J. Patterns of walker use and walker injury. Pediatrics. 1986 Sep;78(3):488–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieber R. A., Branche-Dorsey C. M., Ryan G. W. Comparison of in-line skating injuries with rollerskating and skateboarding injuries. JAMA. 1994 Jun 15;271(23):1856–1858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senturia Y. D., Binns H. J., Christoffel K. K., Tanz R. R. Exposure corrected risk estimates for childhood product related injuries. Accid Anal Prev. 1993 Aug;25(4):473–477. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(93)90077-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]